Abstract

Objectives

To implement the Partner for Promotion (PFP) program which was designed to enhance the skills and confidence of students and community pharmacy preceptors to deliver and expand advanced patient care services in community pharmacies and also to assess the program's impact.

Design

A 10-month longitudinal community advanced pharmacy practice experience was implemented that included faculty mentoring of students and preceptors via formal orientation; face-to-face training sessions; online monthly meetings; feedback on service development materials; and a web site offering resources and a discussion board. Pre- and post-APPE surveys of students and preceptors were used to evaluate perceptions of knowledge and skills.

Assessment

The skills survey results for the first 2 years of the PFP program suggest positive changes occurring from pre- to post-APPE survey in most areas for both students and preceptors. Four of the 7 pharmacies in 2005-2006 and 8 of the 14 pharmacies in 2006-2007 were able to develop an advanced patient care service and begin seeing patients prior to the conclusion of the APPE. As a result of the PFP program from 2005-2007, 14 new experiential sites entered into affiliation agreements with The Ohio State University College of Pharmacy.

Conclusion

The PFP program offers an innovative method for community pharmacy faculty members to work with students and preceptors in community pharmacies in developing patient care services.

Keywords: community pharmacy, pharmaceutical services, administration, advanced pharmacy practice experience

INTRODUCTION

The role of the community pharmacist is evolving from one that previously focused on product delivery to a more advanced role that encompasses the provision of pharmaceutical care with or without the product. Pharmaceutical care in community pharmacies, described as advanced patient care services (ie, medication therapy management, wellness screenings, medication and health education, and disease state management) is well-documented.1 However, many of the reported success stories are shared by pharmacy practice leaders and pharmacy faculty members.2-6 With the advent of Medicare Part D, as well as approved billing codes for pharmacy services, the current healthcare environment is primed for community pharmacists to get involved in providing and being compensated for pharmaceutical care. Unfortunately, many community pharmacists who are interested in offering pharmaceutical care through advanced patient care services in their pharmacy practice settings struggle with the knowledge, and more often the necessary skills, to develop these types of services. In a study in which owners and managers of independent community pharmacies were asked about their knowledge related to community pharmacy strategic planning, the group rated a mean 2.14 ± 1.5 on a scale from 0 = no knowledge to 5 = very knowledgeable.7 The importance of knowledge and skills training to prepare community pharmacists to develop and deliver pharmaceutical care through advanced patient care services has also been well documented.8-10

While pharmacy students are introduced in the classroom to the pharmaceutical care role of the pharmacist in the community setting, and exposed to the pharmacy and medical literature describing the success of pharmacists in patient care, student participation in the development, implementation, and provision of advanced patient care services within a community pharmacy may be somewhat limited.11,12 The 2006 accreditation standards specifically identify that pharmacy practice experiences for PharmD students should include “[provision of] medication therapy management and patient care services.”13 The percentage of community pharmacies in the United States offering advanced patient care services is between 9% and 59%.2 Therefore, student exposure to these activities during their pharmacy practice experiences is not guaranteed. Students who are provided opportunities to apply what they learn about pharmaceutical care in real-life pharmacies during advanced pharmacy practice experiences may be more likely to possess the skills and confidence to develop or deliver advanced patient care services in their own pharmacies following graduation.

The Partner for Promotion program was developed in response to the opportunities related to advanced pharmacy practice in the community and the need to enhance community experiential sites. The goals of the program are to (1) enhance the skills and confidence of students and community pharmacy preceptors to deliver and expand advanced patient care services in community pharmacies, (2) create sustainable advanced patient care services in community pharmacies, and (3) increase the number of quality advanced community pharmacy practice experiential sites for The Ohio State University College of Pharmacy (OSU COP). This paper describes the PFP program and how the goals of the program are being met, and highlights possible components that could be incorporated at other colleges of pharmacy to enhance experiential education and improve patient care.

DESIGN

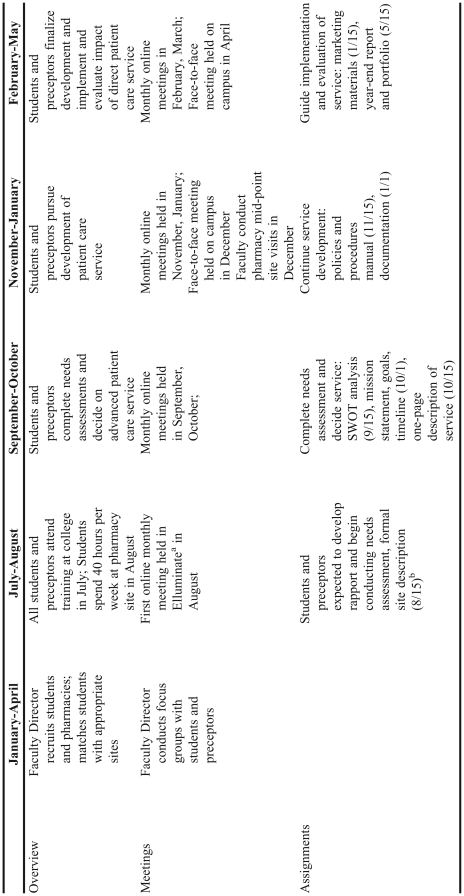

The PFP program is a 10-month longitudinal advanced community advanced pharmacy practice experience (APPE). The timeline for the PFP program is described in Table 1. Students and community pharmacy preceptors were recruited to participate in the program via e-mail announcements about the program to third-year students, brief presentations in therapeutics classes, and individual discussions with students by the Director of Experiential Education, the Faculty Director, and other involved faculty members. Once students expressed interest, the Faculty Director met with students individually or in small groups (ie, 2-3 students) to discuss the program and APPE, explain expectations, and answer any questions.

Table 1.

Timeline for Partner for Promotion Program

Web conferencing program available at www.elluminate.com

Dates in parentheses are assignment due dates.

Multiple strategies were used to recruit pharmacy partners, defined as a primary preceptor and an appropriate practice site participating in the PFP program: (1) the Director of Experiential Education discussed the Partner for Promotion APPE with potential and existing community pharmacy sites; (2) students enrolled in the APPE requested placement at a community pharmacy with which they had a preexisting relationship or at a pharmacy that reflected the setting they hoped to work in post-graduation; and (3) faculty members networked at professional meetings, discussing the APPE with colleagues locally, regionally, and nationally. As a result, pharmacy sites and preceptors interested in the program emerged and become involved as pharmacy partners. When potential sites were identified, the course director evaluated these sites for participation in the PFP program.

Each pharmacy partner interested in being involved in PFP was visited by the course director who conducted a standardized pharmacy partner evaluation based on criteria for the PFP program (Appendix 1) and the OSU COP experiential program, answered any preceptor questions, and discussed the expectations of the preceptor, pharmacy site, and students. Following the visit, the Faculty Director, with input from the experiential director and other involved faculty members, determined whether the site would participate in PFP for the experiential year.

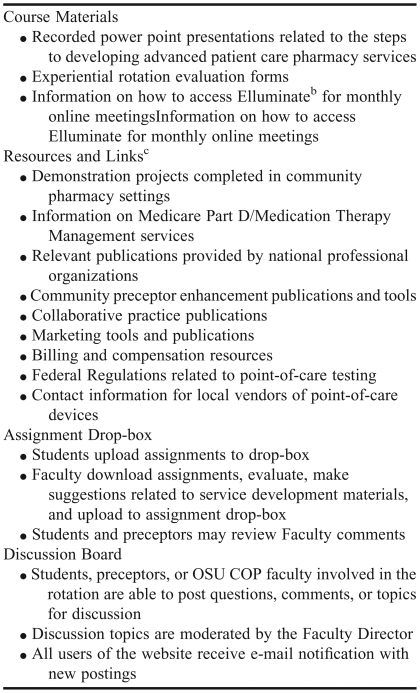

Prior to the beginning of the experiential year, a 1-day training session was held at the College of Pharmacy during the last week of July for all preceptors and students involved in the PFP program. Each student and preceptor received a PFP binder at the training session that contained presentation materials, contact information, and various resources to assist with the rotation activities. The training involved an interactive session for preceptors about how to effectively work with students throughout the longitudinal APPE, an orientation to the APPE for students and preceptors, and a focused, didactic and hands-on session addressing the steps for developing patient-centered pharmacy programs. The orientation session included a review of the syllabus, time for questions from students and preceptors, and a demonstration of the PFP web site (http://www.pharmacy.ohio-state.edu/partner/). The web site was developed specifically for the PFP program through collaboration between the Faculty Director and the OSU COP Information Technology Department, and included course materials, links to resources, an assignment drop box, and an interactive discussion board (Table 2).

Table 2.

Partner for Promotion Web Sitea

Web conferencing program available at www.elluminate.com

Most links to professional pharmacy association web sites, journal articles, continuing education materials, and textbook publications

The APPE commenced with the pharmacy partners each August, approximately 1 week after the orientation session. The PFP program fulfilled the students' required 2-month advanced practice community rotation. Students were assigned to their PFP community pharmacy site for a 1- month, full-time APPE (ie, 160 hours) in August of their advanced practice year. Then from September through May of the academic year, students completed the remainder of the PFP program's longitudinal APPE. During this longitudinal portion, students engaged in a part-time experience for an average of 4 hours per week with the PFP program. The total time of the longitudinal portion of the PFP program was equivalent to a 1-month, full-time APPE (ie, 160 hours). At the same time that they were completing this part-time PFP experience, students were also completing their other required, full-time APPEs (eg, institutional practice, internal medicine, ambulatory care).

Throughout the PFP program, students and preceptors developed an advanced patient care service, with examples being the implementation of medication therapy management services, wellness screenings, medication and health education, or disease state management, based on the needs and resources of the pharmacy partner. The program requirements included: monthly online meetings with students and faculty members; quarterly face-to-face meetings with students, faculty members, and preceptors; individual communication via e-mail, phone calls, and meetings as needed with students, preceptors, and faculty members; and completion of 8 assignments with assistance from preceptors with due dates distributed throughout the 10 months.

The meetings were conducted through Elluminate, Version 7 (Elluminate, Inc, Fort Lauderdale, FL), a real-time virtual classroom environment designed for distance education and collaboration in academic institutions. Via this mechanism, students and faculty members were able to engage in regular meetings from any location, including the comfort of their own home. At each meeting, students provided an update on the progress at their sites and shared ideas and issues supporting or challenging their progress, and faculty members shared suggestions, experiences, and encouragement, and provided any necessary updates. Students discussed new ideas about program development with their fellow students and faculty members. These meetings allowed faculty members to track the progress of each site. Individual sites with specific issues are often contacted by faculty members following the meeting to work with the site and focus on how to answer questions, overcome challenges, and resolve barriers.

Two face-to-face meetings were held during the PFP program. The first meeting was held on campus for all students and preceptors in December of each year, while the second meeting was held at each pharmacy site with each student/preceptor pair and a faculty member. For the on-campus meetings, faculty members provided expanded training on topics relevant to community pharmacy site development; gathered updates, concerns, and questions from each site; and revisited the timeline and goals for the APPE. In December, faculty members also conducted onsite meetings with student/preceptor pairs. These meetings provided a venue for faculty members to direct or encourage individual pharmacies to keep the site on track to enhance the experience for the student as well as insure consistent progress with patient care service development. During this face-to-face meeting at the site, students, preceptors, and faculty members were given the opportunity to share feedback about how to improve the Partner for Promotion APPE and suggest changes that could be made to assist the pair for the remainder of the academic year.

Beyond the formal online and face-to-face PFP meetings, informal communication via e-mail, phone calls, and meetings occurred among faculty members, students, and preceptors at least once monthly. Faculty members were contacted to assist students and preceptors with identifying the next step in service development. Faculty members discussed strategies for overcoming barriers in the individual pharmacy environments with students and preceptors throughout the program year.

Completion of the 8 assignments (Table 1) was required for students to receive their certificate of completion for the PFP program. The due dates for the assignments were flexible to allow for the real-life barriers that arose when developing advanced patient care services in community pharmacies. Students were encouraged to complete these assignments following discussion with their preceptors. Students submitted assignments via an electronic drop box accessed on the PFP program web site. The Faculty Director provided feedback on the assignments, students made recommended changes as appropriate, and all assignments were resubmitted in the portfolio, which was due in the final month of the experiential year. The portfolio had to include all assignments, any other materials the students had developed throughout the APPE, and a completed year-end report. The year-end report required that students reflect and write about the impact they made on the development of advanced patient care services at their pharmacy site. Students were afforded an opportunity to present their developed patient care service at a dessert reception for students, pharmacy partners, and faculty members. As part of this annual event, students and pharmacy partners who had enrolled to participate in PFP for the upcoming academic year attended an informal meet-and-greet session prior to the dessert reception and were invited to stay and gain perspective from students and preceptors who had completed the PFP program the previous year.

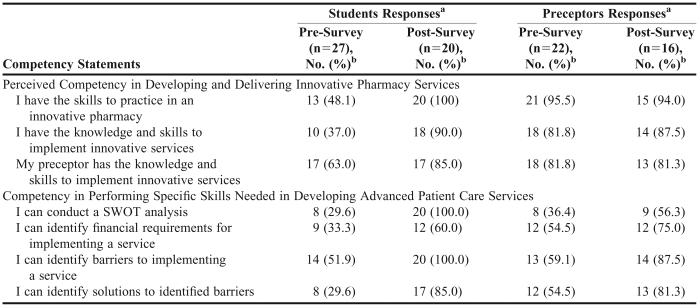

Impact of the PFP program was evaluated through pre- and post-APPE surveys of students and preceptors regarding their perceptions of knowledge and skills required for development of advanced patient care programs, documentation, and follow-up with participating pharmacies related to progress and sustainability of the advanced patient care programs, and documentation of the number of new advanced community pharmacy practice experiences available to PharmD students as a result of the PFP program.

Students and preceptors participating in the PFP program in academic years 2005-2006 and 2006-2007 were invited to complete written pre-APPE surveys at the PFP orientation training day. These same students and preceptors were invited to complete post-surveys upon completion of the PFP program. In 2005-2006, the post-surveys were distributed and completed during a focus group; in 2006-2007, the post-surveys were distributed and completed via Zoomerang (Market Tools, Inc, San Francisco, CA) an online survey site. Results were analyzed using SPSS (SPSS, Chicago, IL). The survey instruments assessed student and preceptor perceptions of their abilities related to the development and delivery of advanced patient care services, as well as their perceptions of their abilities to engage in specific skills needed in developing an advanced patient care service. The surveys utilized a Likert scale design (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) to garner student and preceptor views on skill development. Both the pre- and post-APPE survey instruments were approved by the Investigational Review Board of The Ohio State University.

The stage of service development and preliminary outcomes were gathered via the portfolio submitted by each pharmacy site at the conclusion of the PFP program. This portfolio provided copies of the materials created throughout the program, including but not limited to a needs assessment with SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) analysis, documentation forms, and marketing materials. The portfolio also included a year-end report which described the progress of the program related to number of patients seen as well as future plans. Progress and sustainability of each program was documented via follow-up phone calls to the participating pharmacies 6, 12, and 24 months post-program. One faculty member made the follow-up calls to assure consistency in documentation of patient care service sustainability.

ASSESSMENT

Twenty-seven students and 22 preceptors completed the pre-APPE surveys and 20 students and 16 preceptors completed the post-surveys. The low response rate in the post-survey is partially due to 3 pharmacies withdrawing from the program during the 2006-2007 year. The combined results of the skills surveys for the 2005-2006 and 2006-2007 academic years yielded an increase in students' perceived competency in implementing innovative pharmacy services from pre- to post-APPE survey, while these same indicators remained virtually unchanged for preceptors (Table 3). The improvement in perceived abilities to engage in specific service development skills is evident for both preceptors and students pre- to post-APPE survey.

Table 3.

Pharmacy Students and Preceptors Perceived Competency Ratings Before and After Participating in the Partner for Promotion Program

Participants were asked to respond on a 5-point Likert scale (1=Strongly Disagree, 5=Strongly Agree)

Participants indicating Agree or Strongly Agree

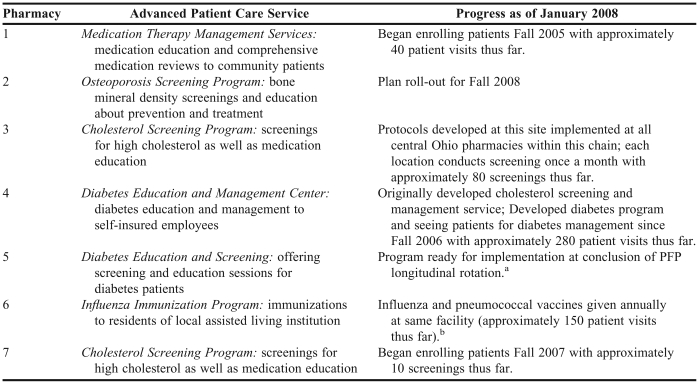

Table 4 describes the progress of patient care service development and delivery 12 months post-program for the pharmacies involved in the Partner for Promotion program during the 2005-2006 academic year. Four of the 7 pharmacies (Pharmacies 1, 3, 6, and 7 as listed in Table 4) were still seeing patients as part of the advanced patient care service developed during the PFP program as of January 2008. Pharmacy 4 identified an opportunity to be involved with a local self-insured employer to offer diabetes management shortly after completing the PFP program. The pharmacy preceptor altered the cholesterol screening and management program developed through the PFP program and utilized these materials to offer a billable diabetes service. Pharmacy 2 originally developed a wellness screening program in collaboration with a local College of Osteopathy, which ceased due to loss of the partnering college; however, the pharmacist who had been involved in the PFP program is in the process of developing an osteoporosis screening service. A follow-up survey of these pharmacies will be completed 24 months post-program to further assess sustainability of the services.

Table 4.

Pharmacy Service Development and Sustainability for Partner for Promotion Pharmacies 2005-2006

Due to low community interest in the program, pharmacy partner has decided not to implement the program

This chain pharmacy now has an immunization program available at all Central Ohio locations. The ideas and experiences from this Partner for Promotion immunization outreach program were shared with the corporation to help improve the corporate immunization outreach program for future years

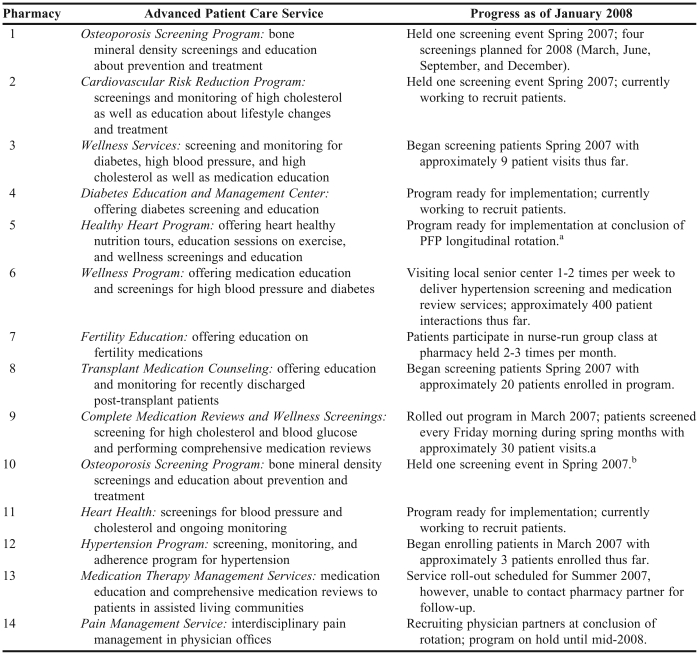

The progress of the 2006-2007 PFP pharmacy students and preceptors is summarized in Table 5. Eight of the 14 pharmacies were able to develop an advanced patient care service and begin seeing patients prior to the conclusion of the APPE (Table 5) and 8 of the 14 pharmacies were able to sustain the patient care service at the time of the 6-month follow up. These pharmacies will be surveyed again 12 months and 24 months post-program to determine sustainability of the services.

Table 5.

Pharmacy Service Development for Partner for Promotion Pharmacies 2006-2007

Due to staffing issues, pharmacy partner is not able to continue the program at this time

Due to low community interest in the program, pharmacy partner has decided not to implement the program, however, is working on development of another advanced patient care program.

As a result of the PFP program from 2005-2007, 14 new experiential sites entered into affiliation agreements with the OSU COP. Seven new experiential sites were created in 2005-2006 and 7 in 2006-2007. In the 2 years following the initial 2005-2006 Partner for Promotion year (academic years 2006-2007 and 2007-2008), 43 additional non-PFP students have participated or are scheduled to participate in APPEs in these 14 new experiential sites developed through PFP.

DISCUSSION

The results of the PFP program 2005-2007 demonstrate the impact a focused effort on community pharmacy practice development by faculty members can have on student and preceptor perceived skill development, development of advanced patient care services in community pharmacies, and enhancement of a college's experiential program related to community pharmacy sites.

The skills survey results for the first 2 years of the PFP program suggest positive changes occurring from pre- to post-APPE survey in most areas for both students and preceptors. A notable finding was that preceptors' perceived competency in implementing and providing innovative pharmacy services did not significantly change pre- to post-APPE survey, remaining greater than 80%. One explanation for this finding is that preceptors may have overestimated their perceived competency prior to their involvement in the PFP program and, through the program, identified areas for growth in advanced patient care service development.

The development and continuation of advanced patient care services in PFP community pharmacy sites is documented for the first 2 years of this program, with enhancement in site and service development occurring through subsequent years. Literature supports the role community faculty members can have on the development of advanced patient care services in community pharmacies,14-16 and suggests that faculty members have a responsibility to reach out to the community to enhance the development of advanced patient care programs.3,17,18 Common models of community faculty practice development involve a faculty member and/or a community pharmacy practice resident creating a new service, and then training pharmacists and/or students to see patients as part of the service.14,16 The PFP program is distinct in the provision of support, training, and mentoring of pharmacy preceptors and students to create their own patient care services. Equipping community pharmacy preceptors with these developmental skills will impact the sustainability of the patient care services as these pharmacists may be more prepared to deal with obstacles in service continuation and more willing to work through the challenges due to perceived ownership of the service. Additionally, these pharmacy sites may function as model learning environments for subsequent advanced pharmacy practice experiential students, as the students will have the opportunity not only to see patients as part of an established service in a community pharmacy, but to learn from the preceptor(s) at the site about the origin and steps that were involved in developing the service.

There are limitations to the data presented. The generalizability of these findings may be influenced by additional funding that was available to partially support the PFP program in 2006-2007 by an Ohio State University Excellence in Engagement grant. Funds from this grant supported 20% of an auxiliary faculty member's time to work with the project, the purchase of 3 lipid point-of-care testing devices which could be leased by pharmacy partners, and the opportunity for pharmacy partners to apply for and receive up to $500 to fund the start-up of their patient care service. However, beyond the availability of the start-up monies, pharmacy partners were not compensated for their participation in the PFP program. Another confounding factor in the assessment of this program is that many preceptors and students participated in professional development opportunities through the OSU COP. For example, in both years, the OSU COP offered the APhA Diabetes Certificate Program for preceptors and local pharmacists and many PFP students and preceptors participated. These additional training programs may have had an impact on the pharmacy partners' and students' knowledge and skills related to the development of advanced patient care services. Finally, 3 pharmacies withdrew from the program in 2006-2007. Reasons for the withdrawals included: preceptor transfer to a different store within a pharmacy chain, preceptor transfer to a new job at a local hospital, and a personal issue that arose with a student during the year.

Future directions for the PFP program include the addition of a PFP-Continuation (PFP-C) program which will provide resources and support to past PFP preceptors to assist them with the continuation of advanced patient care services in their pharmacy sites. This PFP-C program was piloted in the 2007-2008 academic year. Follow-up with past PFP pharmacy sites and students will continue to be conducted at 6, 12, and 24 months post-program to document the continued existence of the advanced patient care services, as well as the impact of involvement in this program on the professional development of students and preceptors.

SUMMARY

The PFP program offers an innovative approach for community pharmacy faculty members to work with community pharmacy sites to enhance their patient care service provision through the training and mentoring of pharmacy preceptors and students, who then create their own services. This program provides the opportunity for community pharmacy faculty members to reach out to the community to enhance the development of pharmacist-run advanced patient care services, while at the same time improving the experiential education of current and future students.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge Gerald (Jerry) Cable, Director of Experiential Education at the OSU COP, for his support throughout the development and implementation of this program and Katherine Kelley, Assistant Dean for Assessment and Accreditation, for her statistical analysis and survey construct consultation. This program was partially funded in 2006-2007 by an Ohio State University Excellence in Engagement Grant. Funds from the grant were utilized to support faculty members, materials, and equipment.

Appendix 1. Criteria for Partner for Promotion Pharmacy Sites

REFERENCES

- 1.McGivney MS, Meyer SM, Duncan-Hewitt W, Hall DL, Goode JV, Smith RB. Medication therapy management: its relationship to patient counseling, disease management, and pharmaceutical care. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2007;47:620–8. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2007.06129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christensen DB, Farris KB. Pharmaceutical care in community pharmacies: Practice and research in the US. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:1400–6. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fincham JE. The need to invest in community pharmacy practice. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71((2)) doi: 10.5688/aj710226. Article 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Gier JJ. Clinical pharmacy in primary care and community pharmacy. Pharmacotherapy. 2000;20:278S–81S. doi: 10.1592/phco.20.16.278s.35005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McLean WM, MacKeigan LD. When does pharmaceutical care impact health outcomes? A comparison of community pharmacy-based studies of pharmaceutical care for patients with asthma. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:625–31. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Wijk BL, Klungel OH, Heerdink ER, de Boer A. Effectiveness of interventions by community pharmacists to improve patient adherence to chronic medication: a systematic review. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:319–28. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrison DL. Effect of attitudes and perceptions of independent community pharmacy owners/managers on the comprehensiveness of strategic planning. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2006;46:459–64. doi: 10.1331/154434506778073718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Mil JW, Schulz M, Tromp TF. Pharmaceutical care, european developments in concepts, implementation, teaching, and research: a review. Pharm World Sci. 2004;26:303–11. doi: 10.1007/s11096-004-2849-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kassam R, Farris KB, Cox CE, et al. Tools used to help community pharmacists implement comprehensive pharmaceutical care. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1999;39:843–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Loughlin J, Masson P, Dery V, Fagnan D. The role of community pharmacists in health education and disease prevention: A survey of their interests and needs in relation to cardiovascular disease. Prev Med. 1999;28:324–31. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zarembski DG, Boyer JG, Vlasses PH. A survey of advanced community pharmacy practice experiences in the final year of the PharmD curriculum at US colleges and schools of pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69((1)) Article 2. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kassam R. Evaluation of pharmaceutical care opportunities within an advanced pharmacy practice experience. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70((3)) doi: 10.5688/aj700349. Article 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. Available at: http://www.acpe-accredit.org/standards/default.asp. Accessed November 15, 2008.

- 14.Kennedy DT, Small RE. Development and implementation of a smoking cessation clinic in community pharmacy practice. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2002;42:83–92. doi: 10.1331/108658002763538116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Narducci WA. Collaboration between academics and practitioners: A view from both sides. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2002;42:5–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dugan BD. Enhancing community pharmacy through advanced pharmacy practice experiences. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70((1)) doi: 10.5688/aj700121. Article 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cerulli J. 2003 prescott lecture. reaching beyond the pharmacy bench: Impressions of academic community pharmacy practice. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;43:S10–4. doi: 10.1331/154434503322612294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennedy DT, Ruffin DM, Goode JV, Small RE. The role of academia in community-based pharmaceutical care. Pharmacotherapy. 1997;17:1352–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]