Abstract

The dimeric, extremely hydrophobic, 44-amino acid bovine papillomavirus (BPV) E5 protein is the smallest known oncoprotein, which orchestrates cell transformation by causing ligand-independent activation of a cellular receptor tyrosine kinase, the platelet-derived growth factor β receptor (PDGFβR). The E5 protein is essentially an isolated membrane-spanning segment that binds directly to the transmembrane domain of the PDGFβR, inducing receptor dimerization, autophosphorylation, and sustained mitogenic signaling. There are few sequence constraints for activity as long as the overall hydrophobicity of the E5 protein and its ability to dimerize are preserved. Nevertheless, the E5 protein is highly specific for the PDGFβR and does not activate other cellular proteins. Genetic screens of thousands of small, artificial hydrophobic proteins with randomized transmembrane domains inserted into an E5 scaffold identified proteins with diverse transmembrane sequences that activate the PDGFβR, including some activators as small as 32-amino acids. Analysis of these novel proteins has provided new insight into the requirements for PDGFβR activation and specific transmembrane recognition in general. These results suggest that small, transmembrane proteins can be constructed and selected that specifically bind to other cellular or viral transmembrane target proteins. By using this approach, we have isolated a 44-amino acid artificial transmembrane protein that appears to activate the human erythropoietin receptor. Studies of the tiny, hydrophobic BPV E5 protein have not only revealed a novel mechanism of viral oncogenesis, but have also suggested that it may be possible to develop artificial small proteins that specifically modulate much larger target proteins by acting within cellular or viral membranes.

Keywords: Oncogene, Transmembrane protein, Tyrosine kinase, BPV E5

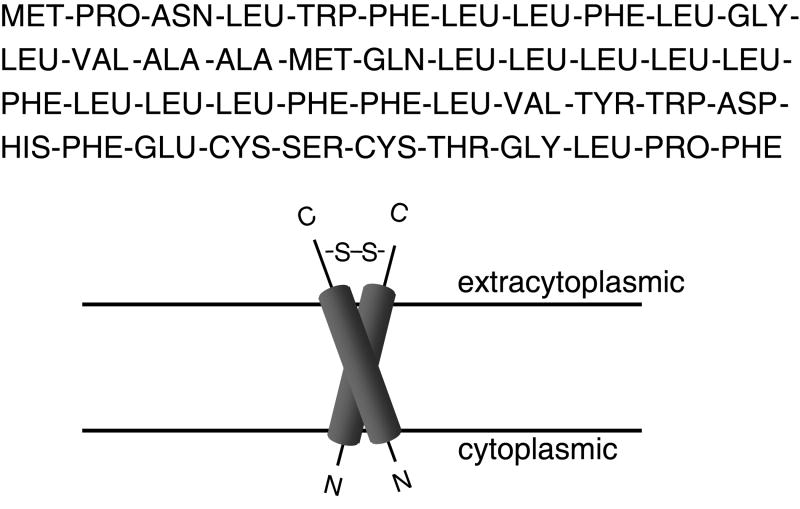

Small DNA viruses face intense evolutionary pressure to maximize their capacity for replication and spread while minimizing the size of their genomes. Individual viruses utilize a variety of means to accomplish this goal: by constructing capsids from repeating subunits; by encoding modular proteins with biologically active elements consisting, in some cases, of only a short stretch of amino acids; and by translating the same segment of RNA in different reading frames to synthesize proteins with totally different amino acid sequences. The bovine papillomavirus type 1 (BPV) and closely related fibropapillomaviruses have perfected another strategy, namely to encode a very small protein with potent biological activities, in order to harness the signaling pathways of the host cell at the cost of a miniscule fraction of the viral genome. The major oncogene product of these viruses, the transmembrane E5 protein, is only 44-amino acids long. SV40 large T antigen, by comparison, is 708-amino acids. The E5 protein is not only the smallest known oncoprotein, it is one of the shortest independently translated proteins known. The E5 sequence is also very hydrophobic, resembling the membrane-spanning segment of a transmembrane protein (Fig. 1). Despite its diminutive size and unusual composition, the E5 protein causes tumorigenic cell transformation by strongly and specifically activating its target, the platelet-derived growth factor β receptor (PDGFβR), in a ligand-independent manner. Detailed analysis of this unique transforming protein has broader implications, as its mechanism of engaging the cellular machinery has revealed new principles of transmembrane protein function and suggested novel approaches to manipulate cell phenotype. In this review, we recount the story of BPV E5 and the PDGF β receptor, highlighting the features that make it unique, what we have learned from it, and the potential scientific and clinical developments it foretells.

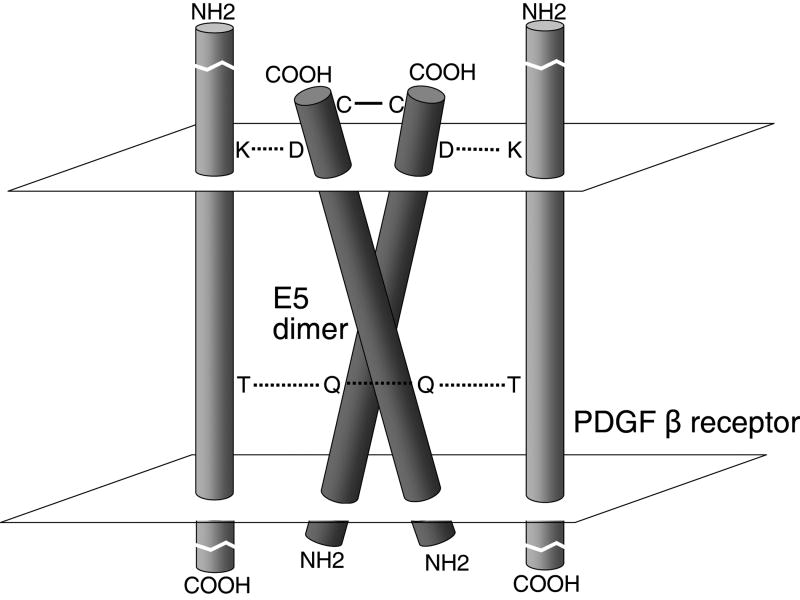

Figure 1. Predicted amino acid sequence of the BPV E5 protein (top) and proposed transmembrane orientation of the E5 dimer (bottom).

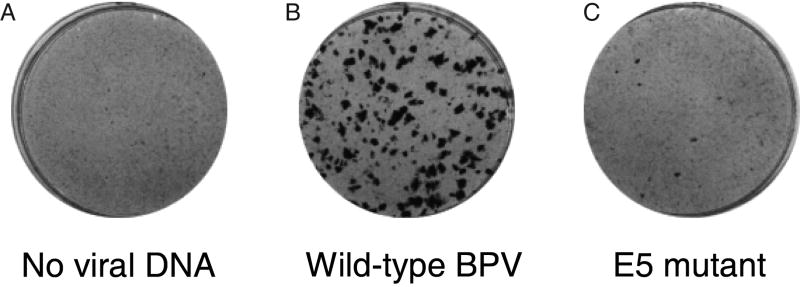

BPV induces skin fibropapillomas, or warts, in cattle. It also induces tumors in hamsters and transforms fibroblasts in tissue culture {for a review of the history of BPV research, see (Lowy, 2007)}. Genetic analysis of the BPV genome mapped this in vitro transformation activity to the BPV E5 gene (Fig. 2) (Groff and Lancaster, 1986; Rabson et al., 1986; Schiller et al., 1986; Yang et al., 1985), which encodes a 44-amino acid, 7 kilodalton membrane-associated protein that exists as a dimer in transformed mouse cells (Schlegel et al., 1986). Its very small size and unusual, very hydrophobic sequence suggested that the E5 protein is essentially an isolated transmembrane domain with transforming activity. Because of this unprecedented conclusion, a variety of in-frame and frameshift mutations were constructed in the E5 reading frame and analyzed for their effect. The results of these experiments revealed an absolute correlation between transforming activity of the mutants and the existence of an intact reading frame downstream of the putative E5 initiation codon (Burkhardt, DiMaio, and Schlegel, 1987; DiMaio, Guralski, and Schiller, 1986). These experiments delineated the E5 coding region and confirmed that this small open reading frame was actually translated into a protein with transforming activity. These conclusions were confirmed by the demonstration that expression of the E5 protein in the absence of other viral genes is sufficient to transform immortalized murine cells to tumorigenicity and to cause growth transformation of primary human cells (Bergman et al., 1988; Petti, Nilson, and DiMaio, 1991; Petti and Ray, 2000).

Figure 2. The E5 protein is the major BPV oncogene in mouse fibroblasts.

Mouse C127 cells were transfected with no viral DNA, wild-type BPV DNA, and a BPV mutant with a frameshift mutation that disrupts the E5 gene. Cells were stained after two weeks to demonstrate the appearance of transformed foci.

Consistent with its strongly hydrophobic amino acid composition, including a central stretch of 29 consecutive hydrophobic amino acids interrupted by only a glutamine at position 17, the E5 protein is found in membrane fractions of transformed cells (Schlegel et al., 1986). It has been localized via immunofluorescence microscopy primarily to Golgi and endoplasmic reticulum membranes, with little if any expression at the plasma membrane (Burkhardt et al., 1989). In bovine warts, the E5 protein is localized to basal epithelial cells and highly differentiated keratinocytes (Burnett, Jareborg, and DiMaio, 1992). The E5 protein appears to adopt a type II transmembrane orientation, i.e. with its hydrophilic C-terminus extending into the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum or Golgi apparatus (Burkhardt et al., 1989). Biophysical experiments and molecular modeling indicated that the E5 protein is in fact a transmembrane dimer that adopts a symmetric left-handed coiled-coil configuration (Oates et al., 2008; Surti et al., 1998).

The very small size of the E5 protein suggested that it would be unlikely to tolerate many mutations and still retain biological activity. However, early studies demonstrated that the entire amino-terminal one quarter of the protein could be substituted with an unrelated sequence of hydrophobic amino acids without loss of transforming activity (Horwitz et al., 1988). Subsequent analysis, first employing extensive mutagenesis of codons 15 through 25 and then complete exchange of the central hydrophobic region of the E5 protein with random hydrophobic sequences, further indicated that this small protein could tolerate a surprising number of substitutions (Horwitz, Weinstat, and DiMaio, 1989; Kulke et al., 1992; Meyer et al., 1994). The few required amino acids include two C-terminal cysteines important for dimerization, the glutamine at position 17, and an aspartic acid at position 33 (Horwitz et al., 1988). Indeed, in several cases, insertion of a glutamine into otherwise inactive E5-like proteins containing large blocks of random hydrophobic sequences conferred activity (Kulke et al., 1992). These data revealed that the extremely small, hydrophobic BPV E5 protein can exert its powerful effect on cell growth even if it harbored numerous sequence changes, as long as the overall hydrophobicity of the protein and certain key residues is maintained.

Multiple cellular targets of the E5 protein have been proposed. The epidermal growth factor receptor, colony stimulating factor-1 receptor, an α-adaptin-like protein, and the 16K subunit of vacuolar H+-ATPase have been shown to interact with the E5 protein, enhance its biological activity in certain settings, or both (Cohen et al., 1993; Cohen, Lowy, and Schiller, 1993; Goldstein et al., 1991; Goldstein and Schlegel, 1990; Martin et al., 1989). Nevertheless, extensive genetic and biochemical data indicate that cell transformation is mediated primarily through binding of the E5 protein to the β isoform of the endogenous PDGF receptor, a receptor tyrosine kinase (DiMaio and Mattoon, 2001; Petti and DiMaio, 1992; Petti, Nilson, and DiMaio, 1991), although alternative pathways of transformation may also exist (Andresson et al., 1995; Suprynowicz et al., 2002; Suprynowicz et al., 2005). The ∼1000-amino acid PDGFβR is a single-span, type I transmembrane protein with three domains: a large, amino-terminal extracellular domain that binds its ligand PDGF; a short (∼20-amino acid) membrane-spanning domain; and a large, intracellular kinase domain. Normally, PDGF binding induces dimerization of the receptor, activation of the tyrosine kinase activity, autophosphorylation of the intracellular domain of the receptor on tyrosine, and mitogenic signaling. Genetic studies demonstrated that the PDGFβR is essential for E5-mediated cell transformation in a variety of cell systems, and that this activity required the kinase activity but not the ligand binding activity of the receptor (Drummond-Barbosa et al., 1995; Goldstein et al., 1994; Nilson and DiMaio, 1993; Riese and DiMaio, 1995). In addition, studies with inhibitors of PDGFβR kinase activity and use of a repressible E5 gene demonstrated that maintenance of transformation required sustained PDGFβR activation (Klein et al., 1998; Lai, Edwards, and DiMaio, 2005).

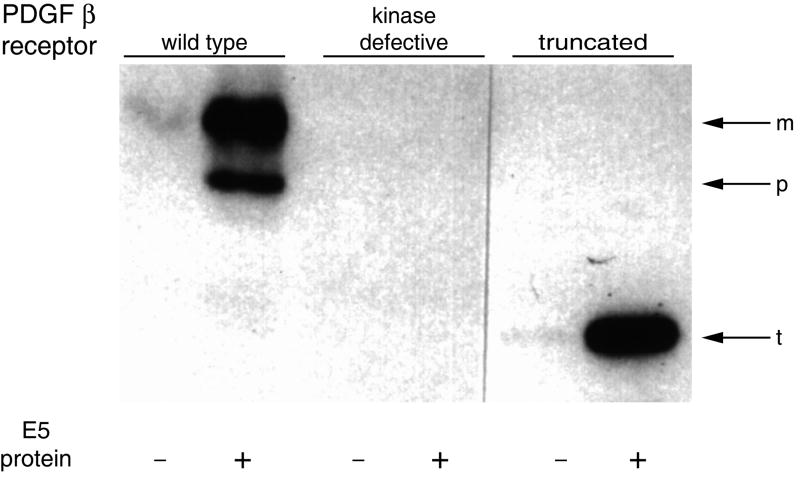

Like PDGF, the E5 protein forms a stable complex with the PDGFβR and induces receptor dimerization and autophosphorylation, which allows cellular signaling proteins containing SH2 domains to bind the receptor and initiate signaling (Figs. 3, 4) (Drummond-Barbosa et al., 1995; Goldstein et al., 1992; Lai, Henningson, and DiMaio, 1998; Lai, Henningson, and DiMaio, 2000; Petti and DiMaio, 1992; Petti, Nilson, and DiMaio, 1991; Petti et al., 2008). However, unlike PDGF, BPV E5 interacts with the receptor not through the ligand binding domain of the receptor, but through its transmembrane domain (Cohen et al., 1993; Drummond-Barbosa et al., 1995; Goldstein et al., 1992). Several features of this interaction are unique to BPV E5 and are worth emphasizing. First, activation of PDGFβR by BPV E5 occurs exclusively through transmembrane and juxtamembrane interactions. Analysis of receptor truncation mutants and point mutants, as well as chimeric receptor constructs, indicated that productive interaction with the E5 protein requires the transmembrane domain of PDGFβR (Cohen et al., 1993; Goldstein et al., 1992; Petti et al., 1997; Staebler et al., 1995). Furthermore, experiments with a truncated PDGFβR lacking the extracellular domain demonstrated that E5 binds and activates the receptor in a ligand-independent manner (Fig. 3) (Drummond-Barbosa et al., 1995), i.e., in the absence of PDGF binding. Finally, coimmunoprecipitation experiments showed that the E5 protein could associate stably with a segment of the PDGFβR consisting primarily of the transmembrane domain but lacking both the extracellular and intracellular domains (Nappi, Schaefer, and Petti, 2002).

Figure 3. Activation of the PDGFβR by the E5 protein.

BaF3 cells expressing the wild-type PDGFβR, a kinase-defective receptor mutant, and a receptor truncation mutant lacking most of the extracellular ligand binding domain were co-expressed in cells with the E5 protein (+) or an empty vector (-). Tyrosine phosphorylated PDGFβR was detected by immunoprecipitation followed by Western blotting for phosphotyrosine. M, p, and t indicate the position of the mature, precursor, and truncated forms of the PDGFβR, respectively. Adapted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Oncogene 20:7866-7873, 2001.

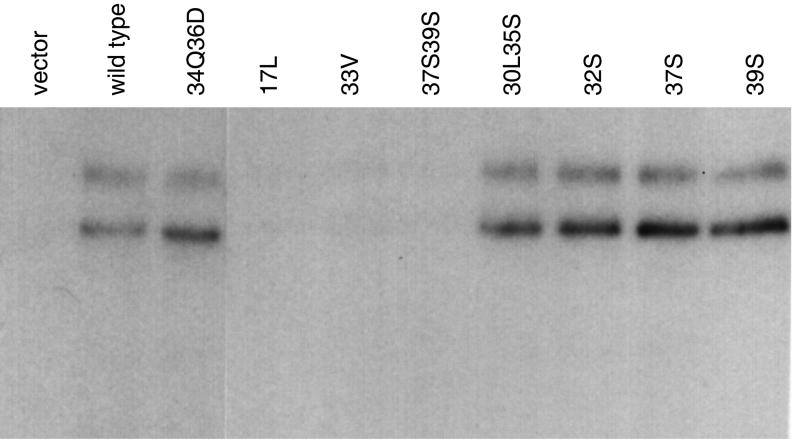

Figure 4. The E5 protein and the PDGFR form a stable complex in cells.

C127 cells expressing the wild-type E5 protein or the indicated E5 mutants were immunoprecipitated by an antibody that recognizes the E5 protein and immunoblotted with an antibody that recognizes the mature and precursor forms of the PDGFβR. Note that the wild-type PDGFβR and several receptor mutants associate with the E5 protein, but mutations at gln17, asp33, and the C-terminal cysteines prevent complex formation. (J. Virology (1995) 69:5869-5874, reproduced with permission from American Society for Microbiology.)

A second noteworthy feature of the E5-PDGFβR interaction is the requirement that the E5 protein must be a dimer to bind and activate the PDGFβR. Mutating the C-terminal cysteines prevents formation of the E5 dimer, inhibits association with PDGFβR, and abrogates transforming activity (Fig. 4) (Horwitz et al., 1988; Nilson et al., 1995). Furthermore, a heterologous dimerization domain can replace the C-terminal cysteines in mediating transformation, unless the domain contains a mutation that blocks dimerization (Mattoon et al., 2001). Additional genetic experiments utilized seven chimeric E5 constructs that forced dimerization of the E5 segments in specific orientations relative to one another, each representing one of the possible homodimer interfaces predicted by a symmetric left-handed coiled-coil configuration. Only one conformation was capable of inducing robust cell transformation and PDGFβR activation, corroborating the proposed structure of the E5 dimer (Mattoon et al., 2001; Surti et al., 1998). Taken together, these data confirm that dimerization of the E5 protein in the proper orientation is required for its ability to activate the PDGFβR.

Mutational analysis showed that only a few of the 44 wild-type amino acids of the E5 protein are critical for PDGFβR recognition and transforming activity. Mutations at glutamine 17 in the transmembrane domain and an aspartic acid residue at position 33 in the juxtamembrane region inhibited PDGFβR binding and activation and impaired cell transformation (Fig. 4) (Horwitz et al., 1988; Meyer et al., 1994; Nilson et al., 1995; Sparkowski, Anders, and Schlegel, 1994). In addition, as noted above, E5 mutants can tolerate multiple hydrophobic substitutions and retain their activity. Mutational analysis also identified a few key PDGFβR residues that are important for interaction with E5, including threonine 513 in the middle of the transmembrane domain (Nappi and Petti, 2002; Petti et al., 1997). A lysine at position 499 of the receptor, located in the putative juxtamembrane region but presumably not buried within the membrane, is also important for E5 binding and transformation (Nappi and Petti, 2002; Nappi, Schaefer, and Petti, 2002; Petti et al., 1997). The essential feature of this residue appears to be its positive charge, because substitution with the positively-charged arginine is tolerated.

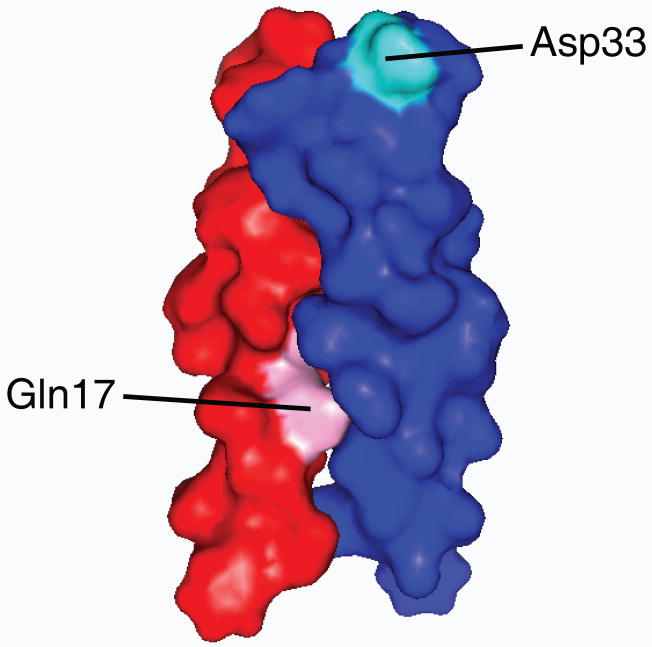

The results summarized above and molecular modeling strongly suggest that the E5 protein and the PDGFβR contact one another directly and that the transmembrane domains lie in an anti-parallel orientation relative to one another (Fig. 5). Saturation mutagenesis of E5 at position 33, an aspartic acid in the wild-type E5 protein, demonstrated that complex formation required a negative charge at this juxtamembrane position, corresponding to the position of a purported salt bridge with the required positively charged juxtamembrane lysine at position 499 of the PDGFβR (Klein et al., 1999; Meyer et al., 1994). In addition, only residues capable of forming hydrogen bonds were tolerated at position 17, a glutamine in wild-type E5 (Klein et al., 1998; Meyer et al., 1994; Sparkowski, Anders, and Schlegel, 1994). The required threonine at position 513 in the PDGFβR transmembrane domain is situated such that it could form a hydrogen bond with the side chain of the amino acid at position 17 of the E5 protein. The existence of these two pairs of essential amino acids (Asp33/Lys499 and Gln17/Thr513) supports the model that the interaction between the transmembrane domains of these proteins is direct and anti-parallel, given the overall opposite transmembrane orientation of the E5 protein (type II) and the PDGFβR (type I) (Petti et al., 1997) (Fig. 5). Furthermore, molecular modeling of the coiled-coil E5 dimer indicates that dimerization of the E5 protein generates two identical faces, each of which is able to bind a monomer of PDGFβR (Surti et al., 1998). On each face of the E5 dimer, one E5 monomer contributes the required glutamine to the PDGFβR binding site and the other monomer contributes the aspartic acid (Fig. 6) (Surti et al., 1998). Thus, dimerization of the two E5 monomers generates binding sites for two PDGFβR molecules, one on each face of the E5 dimer (Fig. 5). This arrangement provides a molecular explanation for the findings that dimerization of the E5 protein is required for receptor binding and that binding to the E5 protein induces dimerization of the receptor. Another model has also been proposed, in which alternative faces of the E5 dimer mediate oligomerization of the E5 protein, PDGFβR binding, and activation of the PDGFβR (Adduci and Schlegel, 1999).

Figure 5. Schematic diagram of the complex between the E5 dimer and two molecules of the PDGFβR.

The two white parallelograms represent the inner and outer leaflets of the membrane. The solid line represents the disulfide bonds that stabilize the E5 dimer, and the dotted lines represent salt bridges and hydrogen bonds mediating the association between the E5 protein and the PDGFβR, as well as a hydrogen bond between the glutamines that stabilizes the E5 dimer. C, cysteine; D, aspartic acid 33; K, lysine 499; Q, glutamine 17; T, threonine 513.

Figure 6. Surface representation of the E5 dimer as determined by molecular modeling.

One face of the E5 dimer is shown. One E5 monomer in the dimer is colored dark blue and the other red. The essential aspartic acid (pink) and glutamine (light blue) were contributed by different monomers on one face of the dimer are shown. Figure courtesy of Brad Stanley and Donald Engelman.

Another striking feature of the E5/PDGFβR interaction is its high specificity. For many years, the membrane-spanning domains of proteins were regarded as fairly non-specific sequences whose primary, if not exclusive, role was to anchor proteins in the lipid bilayer. Recently, however, it has become apparent that the transmembrane domains of many proteins undergo highly specific side-by-side interactions within the membrane. This is certainly true for the E5 protein. Some single point mutations in the transmembrane domain of the PDGFβR can prevent E5 recognition and binding (Nappi, Schaefer, and Petti, 2002; Petti et al., 1997). Furthermore, at normal levels of expression, the E5 protein associates with the PDGFβR but not with other receptor tyrosine kinases, although at high expression levels additional receptors can be recognized (Goldstein et al., 1994; Petti and DiMaio, 1994). The E5 protein is not able to bind or activate the closely-related PDGF α receptor (PDGFαR), even though both the PDGFαR and the PDGFβR are activated by PDGF (Goldstein et al., 1994; Petti and DiMaio, 1994). This specificity maps to the transmembrane domain of the receptors (Staebler et al., 1995).

Although the BPV E5 protein takes viral reductionism to the extreme, there are other examples of small, hydrophobic viral proteins. The human papillomaviruses (HPV) encode hydrophobic E5 proteins that are about twice the size of the BPV version. The HPV E5 proteins are involved in virus replication and transformation, apparently by influencing the activity of the EGF receptor and possibly the vacuolar H+-ATPase (Conrad, Bubb, and Schlegel, 1993; Genther-Williams et al., 2005). Other examples include the small hydrophobic protein (SH protein) of the paramyxoviruses and the influenza virus M2 protein, which oligomerizes to form an ion channel and is the target of the anti-viral drug, amantadine. It is intriguing to speculate that cells may also encode as-yet-unrecognized small transmembrane proteins for a variety of processes.

The studies summarized above demonstrate that the BPV E5 protein is essentially an isolated transmembrane domain capable of specifically modulating the activity of a much larger transmembrane protein in trans. Only a few residues in the wild-type E5 sequence have been identified that are required for activation of the PDGFβR, and many of these can be substituted with amino acids exhibiting similar properties without causing a loss of function. To explore these unique features of the E5 protein more fully, we constructed libraries expressing artificial, small transmembrane proteins by using the BPV E5 sequence as a scaffold and identified other proteins that modulate PDGFβR (Freeman-Cook and DiMaio, 2005).

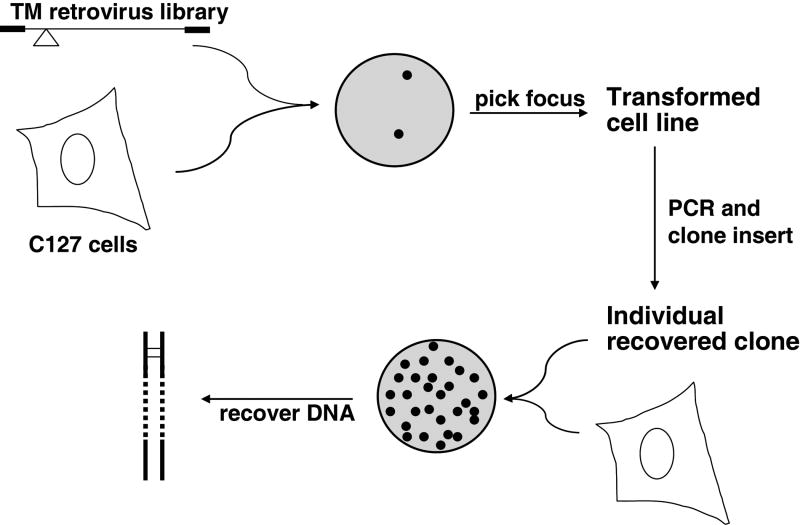

In these libraries, the amino- and carboxyl-terminal segments of the E5 protein were fixed (including the essential aspartic acid at position 33), but PCR with a degenerate oligonucleotide template was used to replace the central segment of the E5 protein with random sequences of primarily hydrophobic amino acids. These libraries were constructed in retrovirus vectors and encode in aggregate many thousands or millions of small proteins, each with a different putative transmembrane domain. These libraries were screened in murine fibroblasts for novel proteins able to induce cell transformation, as scored by the generation of transformed foci (Fig. 7). Genes encoding novel proteins able to induce transformation were cloned from the transformed cells and analyzed.

Figure 7. Scheme to isolate small, transmembrane proteins with transforming activity from complex libraries.

See text for details. Reprinted from J. Mol. Biol. 338, Freeman-Cook, et al., Selection and Characterization of Small Random Transmembrane Proteins that Bind and Activate the Platelet-derived Growth Factor β Receptor, pp. 907-920 (2004), with permission from Elsevier.

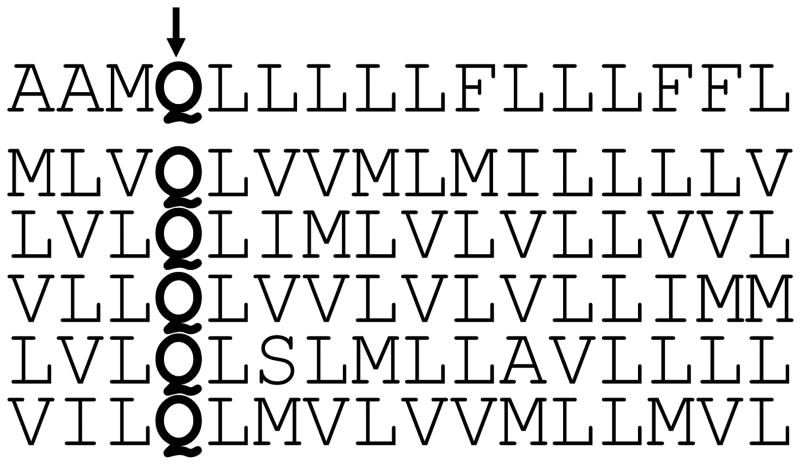

If the glutamine at position 17 was fixed in an otherwise randomized transmembrane domain, approximately 10% of the library members displayed transforming activity (Freeman-Cook et al., 2004). As predicted, the active proteins isolated from the libraries contained diverse transmembrane domain sequences (Fig. 8), and all of them transformed cells by activating the PDGFβR via its transmembrane domain, did not activate the PDGFαR, and existed as dimers. The remarkable ease with which active proteins with diverse transmembrane sequences were recovered, even though a third or more of the protein was randomized, highlights the existence of relatively few sequence constraints on the E5 protein for PDGFβR binding and activation if the interacting pairs of hydrophilic amino acids were retained. This conclusion was verified by the demonstration that insertion of a simple consensus motif derived from the active library clones was sufficient to confer activity on an inactive E5-like protein containing an otherwise monotonous poly-leucine transmembrane domain. In a second library, the entire transmembrane domain, including position 17, was randomized, and hydrophilic amino acids were allowed to be inserted at a low frequency at any transmembrane position. Only 1% of the members of this library transformed cells, but again the PDGFβR was the exclusive target (Freeman-Cook et al., 2005). Of note, many of the active clones contained an essential hydrophilic amino acid, primarily at position 17 or at other positions predicted to be in the E5 homodimer interface, where they are partially shielded from the hydrophobic lipid environment. Several activators isolated from randomized transmembrane protein libraries displayed specificity that differed slightly from that of wild-type E5. For example, in contrast to the wild-type E5 protein, some of these proteins were able to activate a PDGFβR mutant containing a threonine to leucine mutation at position 513 in the transmembrane domain. The altered specificity of these small transmembrane proteins provides additional evidence that they directly contact the transmembrane domain of the PDGFβR.

Figure 8. Diverse, artificial transmembrane proteins can activate the PDGFβR and transform cells.

The figure shows the sequences of the transmembrane domain of small, transmembrane proteins that transform cells. These proteins were recovered from libraries in which a 15-amino acid segment was randomized to primarily hydrophobic amino acids, but the glutamine at position 17 (bold Q) was not varied. The top line shows the transmembrane sequence of the wild-type E5 protein. Reprinted from J. Mol. Biol. 338, Freeman-Cook, et al., Selection and Characterization of Small Random Transmembrane Proteins that Bind and Activate the Platelet-derived Growth Factor β Receptor, pp. 907-920 (2004), with permission from Elsevier.

We also constructed and screened a library that lacked hydrophilic transmembrane amino acids and the aspartic acid at position 33. Clones able to transform murine fibroblasts were isolated from this library at a very low frequency, highlighting the importance of hydrophilic interactions in PDGFβR recognition (Ptacek et al., 2007). Like the E5 protein, the active proteins lacking hydrophilic amino acids induced transformation by specifically activating the PDGFβR. Indeed, several of these proteins were more specific than the wild-type E5 protein, in that they failed to activate some transmembrane mutants of PDGFβR that were activated by the wild-type viral protein. This increased specificity is presumably a consequence of the loss of the two strong hydrophilic interactions that are essential for interaction between the wild-type E5 protein and the PDGFβR, forcing the E5 protein and the transmembrane domain of the PDGFβR to rely on more specific packing interactions. Strikingly, some single amino acid changes within the small transmembrane proteins isolated from the library had dramatic effects on which particular PDGFβR transmembrane mutants were recognized, and insertion of two specific hydrophobic amino acids into a protein with a polyleucine transmembrane domain was sufficient to generate a protein that could discriminate between the PDGFβR and the PDGFαR transmembrane domains.

Transmembrane proteins even smaller than the E5 protein can also bind and activate the PDGFβR. A truncated, 34-amino acid E5 protein, consisting of near wild-type sequence through residue 33 and a cysteine at 34, which presumably forces dimerization, was still capable of transforming cells, but its mechanism of action was not investigated (Meyer et al., 1994). The champion so far is a 32-amino acid transforming protein with a novel transmembrane sequence that activated the PDGFβR, as demonstrated by conferral of growth factor-independent cell proliferation and receptor phosphorylation. Further experiments with chimeric receptors demonstrated that this very small protein, like its fellow PDGFβR activators, specifically recognized the transmembrane domain of the PDGFβR. Despite the absence of the carboxyl-terminal cysteines in the 32-amino acid activator, current evidence suggests that it still forms a homodimer, presumably through hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic packing interactions within the transmembrane segment, underscoring the importance of homodimerization of these small, transmembrane proteins.

The studies summarized above suggested a new approach to modulate the activity of cellular transmembrane proteins. We hypothesized that it might be possible to identify other small, artificial transmembrane proteins that bind specifically to essentially any naturally occurring transmembrane domain. To test whether libraries based on the E5 protein encode small transmembrane proteins that can bind to the transmembrane domain of cellular targets that are entirely different from the PDGFβR, we searched for novel, transmembrane activators of the erythropoietin receptor (EPOR). Upon binding erythropoietin, the EPOR is phosphorylated and initiates a signaling cascade that ultimately results in the proliferation and differentiation of red blood cell precursors. A precedent exists for transmembrane modulation of the EPOR, namely gp55, a variant envelope protein encoded by the Friend Erythroleukemia Virus. gp55 binds and activates the murine EPOR, resulting in unchecked red blood cell proliferation characteristic of erythroleukemia (Li et al., 1989). Unlike BPV E5, gp55 is a 55 kDa protein with a relatively large extracellular domain, but transmembrane interactions between gp55 and the EPOR appear important for receptor activation (Constantinescu et al., 2003; Constantinescu et al., 1999; Zon et al., 1992). By screening a small transmembrane protein library encoding a randomized, 19-amino acid transmembrane segment, we identified a 44-amino acid protein with a novel transmembrane domain that appears to induce activation of the human EPOR in a ligand-independent manner. Other than its overall hydrophobicity, the sequence of the transmembrane domain of this protein does not resemble the transmembrane domain of gp55 or the E5 protein. Strikingly, this protein does not activate the closely related murine EPOR, nor does it induce transformation in cells expressing the PDGFβR. We are in the process of determining whether this small protein, like the wild-type E5 protein and the other proteins previously recovered from randomized libraries, activates its target by directly interacting with its transmembrane domain.

These results provide optimism that small, transmembrane proteins based on the E5 protein can be selected that specifically recognize a variety of transmembrane proteins. If the appropriate selections can be devised, it may also be possible to isolate small transmembrane proteins that inhibit their targets. Indeed, an initial isolate that activates or simply binds its target may serve as the substrate for further mutagenesis or directed evolution to convert it into an inhibitor. Other laboratories have modulated the activity of cellular transmembrane proteins by expressing small proteins containing transmembrane domains derived from naturally occurring proteins (Bennasroune et al., 2004; Lofts et al., 1993). In contrast, the approach we describe involves the construction and selection of active transmembrane segments with no naturally-occurring counterpart. These artificial proteins have the potential to display favorable properties such as higher affinity, greater stability, or increased specificity than naturally occurring proteins, as we have observed with the small transmembrane proteins that activate PDGFβR with greater specificity than the wild-type E5 protein. The power of genetic selection would allow the isolation of potent transmembrane modulators that do not occur in nature, rather than relying on an intrinsically more restricted approach, which utilizes naturally-occurring transmembrane segments to guide the design of active proteins.

In most studies, the E5 protein and related proteins were expressed within cells, where they can associate with their cellular membrane targets during intracellular trafficking or at the cell surface. It is also possible to add biologically active hydrophobic peptides exogenously to cells. A variety of small, hydrophobic peptides based on naturally occurring transmembrane domains have been synthesized and shown to insert into cellular membranes, where they can bind and alter the activity of their native transmembrane protein targets {e.g., (Herbert et al., 1999; Manolios, Bonifacino, and Klausner, 1990; Manolios et al., 1997; Tarasova, Rice, and Michejda, 1999)}. Artificial hydrophobic peptides that can insert into cell membranes and exert biological activity have also been designed based on biophysical principles or computational modeling (DeGrado, Gratkowski, and Lear, 2003; Reshetnyak et al., 2006).

One can envision a strategy that combines the approaches described above to develop clinically important compounds that target transmembrane proteins. First, genetic selection from randomized libraries of small transmembrane proteins could be used to identify an initial, biologically active hit containing a transmembrane sequence not found in nature. This transmembrane modulator could be mutagenized or optimized computationally, and then subjected to additional selection or testing. In this manner, it may be possible to identify minimal motifs and define essential structural features, to convert an activator into an inhibitor (if desired), and to optimize valuable parameters such as affinity, specificity, stability, solubility, and ease of synthesis. The optimized protein could then serve as a template for the design of synthetic peptides or small, peptidomimetic molecules that incorporate these essential structural features and retain biological activity in a form that is more suitable for delivery to patients.

Targets for this sort of approach include many cellular and viral transmembrane proteins, such as cellular receptors for a wide variety of viruses, viral fusion proteins such as influenza virus hemagglutinin, and a vast array of cellular proteins implicated in cancer and other diseases. Thus, studies of a bizarre oncogene from a virus that causes warts in cattle have revealed new insights into cell transformation, receptor function, and transmembrane domain recognition, activity, and specificity. The E5 protein still has lessons to teach us, and if we are diligent students, we may learn how to harness its unique properties to devise new approaches to understand cells and to prevent and treat disease.

Acknowledgments

The work carried out in the authors' laboratory on the BPV E5 protein and related topics was supported by grants to DD from the NIH (CA37157), the Yale Skin Cancer SPORE (CA121974), the Northeast Biodefense Center (RCE 15-0183-05), and a generous gift from Laurel Schwartz. KTS was supported in part by an Anna Fuller Fund Predoctoral fellowship. We thank J. Zulkeski for assistance in preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adduci AJ, Schlegel R. The transmembrane domain of the E5 oncoprotein contains functionally discrete helical faces. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10249–10258. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.10249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresson T, Sparkowski J, Goldstein DJ, Schlegel R. Vacuolar H+-ATPase mutants transform cells and define a binding site for the papillomavirus E5 oncoprotein. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:6830–6837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.12.6830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennasroune A, Fickova M, Gardin A, Dirrig-Grosch S, Aunis D, Cremel G, Hubert P. Transmembrane peptides as inhibitors of ErbB receptor signaling. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:3464–3474. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-10-0753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman P, Ustav M, Sedman J, Moreno-Lopez J, Vennstrom B, Pettersson U. The E5 gene of bovine papillomavirus type 1 is sufficient for complete oncogenic transformation of mouse fibroblasts. Oncogene. 1988;2:453–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt A, DiMaio D, Schlegel R. Genetic and biochemical definition of the bovine papillomavirus E5 transforming protein. Embo J. 1987;6(8):2381–5. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02515.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt A, Willingham M, Gay C, Jeang KT, Schlegel R. The E5 oncoprotein of bovine papillomavirus is oriented asymmetrically in Golgi and plasma membranes. Virology. 1989;170:334–339. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90391-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett S, Jareborg N, DiMaio D. Localization of bovine papillomavirus type 1 E5 protein to transformed basal keratinocytes and permissive differentiated cells in fibropapilloma tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(12):5665–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen BD, Goldstein DJ, Rutledge L, Vass WC, Lowy DR, Schlegel R, Schiller JT. Transformation-specific interaction of the bovine papillomavirus E5 oncoprotein with the platelet-derived growth factor receptor transmembrane domain and the epidermal growth factor receptor cytoplasmic domain. J Virol. 1993;67:5303–5311. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5303-5311.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen BD, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. The conserved C-terminal domain of the bovine papillomavirus E5 oncoprotein can associate with an alpha-adaptin-like molecule: a possible link between growth factor receptors and viral transformation. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:6462–6468. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.6462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad M, Bubb VJ, Schlegel R. The human papillomavirus type 6 and 16 E5 proteins are membrane-associated proteins which associate with the 16-kilodalton pore-forming protein. J Virol. 1993;67:6170–6178. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.6170-6178.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinescu SN, Keren T, Russ WP, Ubarretxena-Belandia I, Malka Y, Kubatzky KF, Engelman DM, Lodish HF, Henis YI. The erythropoietin receptor transmembrane domain mediates complex formation with viral anemic and polycythemic gp55 proteins. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:43755–43763. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302974200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinescu SN, Liu X, Beyer W, Fallon A, Shekar S, Henis YI, Smith SO, Lodish HF. Activation of the erythropoietin receptor by the gp55-P viral envelope protein is determined by a single amino acid in its transmembrane domain. EMBO J. 1999;18:3334–3347. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.12.3334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGrado WF, Gratkowski H, Lear JD. How do helix-helix interactions help determine the fols of membrane proteins? Perspectives from the study of homo-oligomeric helical bundles. Protein Sci. 2003;12:647–665. doi: 10.1110/ps.0236503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMaio D, Guralski D, Schiller JT. Translation of open reading frame E5 of bovine papillomavirus is required for its transforming activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83(6):1797–801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.6.1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMaio D, Mattoon D. Mechanisms of cell transformation by papillomavirus E5 proteins. Oncogene. 2001;20:7866–7873. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond-Barbosa DA, Vaillancourt RR, Kazlauskas A, DiMaio D. Ligand-independent activation of the platelet-derived growth factor beta receptor: requirements for bovine papillomavirus E5-induced mitogenic signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15(5):2570–2581. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman-Cook L, Dixon AM, Frank JB, Xia Y, Ely L, Gerstein M, Engelman DM, DiMaio D. Selection and characterization of small random transmembrane proteins that bind and activate the platelet-derived growth factor β receptor. J Mol Biol. 2004;338:907–920. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman-Cook LL, DiMaio D. Modulation of cell function by small transmembrane proteins modeled on the bovine papillomavirus E5 protein. Oncogene. 2005;24:7756–7762. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman-Cook LL, Edwards APB, Dixon AM, Yates KE, Ely L, Engelman DM, DiMaio D. Specific locations of hydrophilic amino acids in constructed transmembrane ligands of the platelet-derived growth factor β receptor. J Mol Biol. 2005;345:907–921. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genther-Williams SM, Disbrow GL, Schlegel R, Lee D, Threadgill DW, Lambert PF. Requirement of epidermal growth factor receptor for hyperplasia induced by E5, a high-risk human papillomavirus oncogene. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6534–6542. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein DJ, Andresson T, Sparkowski JJ, Schlegel R. The BPV-1 E5 protein, the 16 kDa membrane pore-forming protein and the PDGF receptor exist in a complex that is dependent on hydrophobic transmembrane interactions. EMBO J. 1992;11:4851–4859. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05591.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein DJ, Finbow ME, Andresson T, McLean P, Smith K, Bubb V, Schlegel R. Bovine papillomavirus E5 oncoprotein binds to the 16K component of vacuolar H(+)-ATPases. Nature. 1991;352:347–349. doi: 10.1038/352347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein DJ, Li W, Wang LM, Heidaran MA, Aaronson SA, Shinn R, Schlegel R, Pierce JH. The bovine papillomavirus type 1 E5 transforming protein specifically binds and activates the beta-type receptor for platelet-derived growth factor but not other tyrosine kinase-containing receptors to induce cellular transformation. J Virol. 1994;68:4432–4441. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.7.4432-4441.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein DJ, Schlegel R. The E5 oncoprotein of bovine papillomavirus binds to a 16 kd cellular protein. EMBO J. 1990;9:137–145. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groff DE, Lancaster WD. Genetic analysis of the 3′ early region transformation and replication functions of bovine papillomavirus type 1. Virology. 1986;150:221–230. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90281-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert BS, Pitts AE, Baker SI, Hamilton SE, Wright WE, Shay JW, Corey DR. Inhibition of human telomerase in immortal human cells leads to progressive telomere shortening and cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14276–14281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz BH, Burkhardt AL, Schlegel R, DiMaio D. 44-amino-acid E5 transforming protein of bovine papillomavirus requires a hydrophobic core and specific carboxyl-terminal amino acids. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8(10):4071–8. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.10.4071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz BH, Weinstat DL, DiMaio D. Transforming activity of a 16-amino-acid segment of the bovine papillomavirus E5 protein linked to random sequences of hydrophobic amino acids. J Virol. 1989;63(11):4515–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.11.4515-4519.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein O, Kegler-Ebo D, Su J, Smith S, DiMaio D. The bovine papillomavirus E5 protein requires a juxtamembrane negative charge for activation of the platelet-derived growth factor beta receptor and transformation of C127 cells. J Virol. 1999;73(4):3264–3272. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.3264-3272.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein O, Polack GW, Surti T, Kegler-Ebo D, Smith SO, DiMaio D. Role of glutamine 17 of the bovine papillomavirus E5 protein in platelet-derived growth factor beta receptor activation and cell transformation. J Virol. 1998;72(11):8921–8932. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.8921-8932.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulke R, Horwitz BH, Zibello T, DiMaio D. The central hydrophobic domain of the bovine papillomavirus E5 transforming protein can be functionally replaced by many hydrophobic amino acid sequences containing a glutamine. J Virol. 1992;66(1):505–11. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.1.505-511.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai CC, Edwards APB, DiMaio D. Productive interaction between transmembrane mutants of the bovine papillomavirus E5 protein and the platelet-derived growth factor β receptor. J Virol. 2005;79:1924–1929. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1924-1929.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai CC, Henningson C, DiMaio D. Bovine papillomavirus E5 protein induces oligomerization and trans- phosphorylation of the platelet-derived growth factor β receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15241–15246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai CC, Henningson C, DiMaio D. Bovine papillomavirus E5 protein induces the formation of signal transductcion complexes containing dimeric activated platelet-derived growth factor β receptor and associated signaling proteins. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9832–9840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Knight J, Bream G, Stenlund A, Botchan M. Specific recognition nucleotides and their DNA context determine the affinity of E2 protein for 17 binding sites in the BPV-1 genome. Genes Dev. 1989;3:510–526. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.4.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lofts FJ, Hurst HC, Sternberg MJE, Gullick WJ. Specific short transmembrane sequences can inhibit transformation by the mutant neu growth factor receptor in vitro and in vivo. Oncogene. 1993;8:2813–2820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowy DR. History of Papillomavirus Research. In: Garcea R, DiMaio D, editors. Papillomaviruses. Springer; New York: 2007. pp. 32–47. [Google Scholar]

- Manolios N, Bonifacino JS, Klausner RD. Transmembrane helical interactions and the assembly of the T cell receptor complex. Science. 1990;249:274–277. doi: 10.1126/science.2142801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manolios N, Collier S, Taylor J, Pollard J, Harrison LC, Bender V. T-cell antigen receptor transmembrane peptides modulate T-cell function and T cell-mediated disease. Nature Med. 1997;3:84–88. doi: 10.1038/nm0197-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P, Vass WC, Schiller JT, Lowy DR, Velu TJ. The bovine papillomavirus E5 transforming protein can stimulate the transforming activity of EGF and CSF-1 receptors. Cell. 1989;59:21–32. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90866-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattoon D, Gupta K, Doyon J, Loll PJ, DiMaio D. Identification of the transmembrane dimer interface of the bovine papillomavirus E5 protein. Oncogene. 2001;20:3824–3834. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer AN, Xu YF, Webster MK, Smith AS, Donoghue DJ. Cellular transformation by a transmembrane peptide: structural requirements for the bovine papillomavirus E5 oncoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4634–4638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nappi VM, Petti LM. Multiple transmembrane amino acid requirements suggest a highly specific interaction between the bovine papillomavirus E5 oncoprotein and the platelet-derived growth factor beta receptor. J Virol. 2002;76:7976–7986. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.16.7976-7986.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nappi VM, Schaefer JA, Petti LM. Molecular examination of the transmembrane requirements of the platelet-derived growth factor beta receptor for a productive interaction with the bovine papillomavirus E5 oncoprotein. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:47149–47159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209582200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilson LA, DiMaio D. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor can mediate tumorigenic transformation by the bovine papillomavirus E5 protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13(7):4137–45. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.4137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilson LA, Gottlieb RL, Polack GW, DiMaio D. Mutational analysis of the interaction between the bovine papillomavirus E5 transforming protein and the endogenous beta receptor for platelet-derived growth factor in mouse C127 cells. J Virol. 1995;69(9):5869–5874. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5869-5874.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oates J, Hicks M, Dafforn T, DiMaio D, Dixon AM. Role of the transmembrane domain in stable dimerization of the bovine papillomavirus E5 protein. Biochemistry. 2008 doi: 10.1021/bi8006252. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petti L, DiMaio D. Stable association between the bovine papillomavirus E5 transforming protein and activated platelet-derived growth factor receptor in transformed mouse cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89(15):6736–6740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.6736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petti L, DiMaio D. Specific interaction between the bovine papillomavirus E5 transforming protein and the beta receptor for platelet-derived growth factor in stably transformed and acutely transfected cells. J Virol. 1994;68(6):3582–3592. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.3582-3592.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petti L, Nilson LA, DiMaio D. Activation of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor by the bovine papillomavirus E5 transforming protein. EMBO J. 1991;10(4):845–855. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb08017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petti LM, Ray FA. Transformation of mortal human fibroblasts and activation of a growth inhibitory pathway by the bovine papillomavirus E5 oncoprotein. Cell Growth Differ. 2000;11:395–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petti LM, Reddy V, Smith SO, DiMaio D. Identification of amino acids in the transmembrane and juxtamembrane domains of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor required for productive interaction with the bovine papillomavirus E5 protein. J Virol. 1997;71(10):7318–7327. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7318-7327.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petti LM, Ricciardi EC, Page HJ, Porter KA. Transforming signals resulting from sustained activation of the PDGFβ receptor in mortal human fibroblasts. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:1172–1182. doi: 10.1242/jcs.018713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptacek JB, Edwards APB, Freeman-Cook LL, DiMaio D. Packing contacts can mediate highly specific interactions between artificial transmembrane proteins and the PDGF beta receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:11945–11950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704348104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabson MS, Yee C, Yang YC, Howley PM. Bovine papillomavirus type 1 3′ early region transformation and plasmid maintenance functions. J Virol. 1986;60:626–634. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.2.626-634.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reshetnyak YK, Andreev OA, Lehnert U, Engelman DM. Translocation of molecules into cells by pH-dependent insertion of a transmembrane helix. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:6460–6465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601463103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riese DJ, II, DiMaio D. An intact PDGF signaling pathway is required for efficient growth transformation of mouse C127 cells by the bovine papillomavirus E5 protein. Oncogene. 1995;10(7):1431–1439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller JT, Vass WC, Vousden KH, Lowy DR. E5 open reading frame of bovine papillomavirus type 1 encodes a transforming gene. J Virol. 1986;57:1–6. doi: 10.1128/jvi.57.1.1-6.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel R, Wade-Glass M, Rabson MS, Yang YC. The E5 transforming gene of bovine papillomavirus encodes a small hydrophobic protein. Science. 1986;233:464–467. doi: 10.1126/science.3014660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparkowski J, Anders J, Schlegel R. Mutation of the bovine papillomavirus E5 oncoprotein at amino acid 17 generates both high- and low-transforming variants. J Virol. 1994;68:6120–6123. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.6120-6123.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staebler A, Pierce JH, Brazinski S, Heidaran MA, Li W, Schlegel R, Goldstein DJ. Mutational analysis of the beta-type platelet-derived growth factor receptor defines the site of interaction with the bovine papillomavirus type 1 E5 transforming protein. J Virol. 1995;69:6507–6517. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6507-6517.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suprynowicz FA, Baege A, Sunitha I, Schlegel R. c-Src activation by the E5 oncoprotein enables transformation independently of PDGF receptor activation. Oncogene. 2002;21:1695–1706. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suprynowicz FA, Disbrow GL, Simic V, Schlegel R. Are transforming properties of the bovine papillomavirus E5 protein shared by E5 from high-risk human papillomavirus type 16? Virology. 2005;332:102–113. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surti T, Klein O, Aschheim K, DiMaio D, Smith SO. Structural models of the bovine papillomavirus E5 protein. Proteins. 1998;33(4):601–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarasova NI, Rice WG, Michejda CJ. Inhibition of G-protein-coupled receptor function by disruption of transmembrane domain interactions. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34911–34915. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YC, Spalholz BA, Rabson MS, Howley PM. Dissociation of transforming and trans-activation functions for bovine papillomavirus type 1. Nature. 1985;318:575–577. doi: 10.1038/318575a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zon LI, Moreau JF, Koo JW, Mathey-Prevot B, D'Andrea AD. The erythropoietin receptor transmembrane region is necessary for activation by the Friend spleen focus-forming virus gp55 glycoprotein. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2949–2957. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.7.2949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]