Abstract

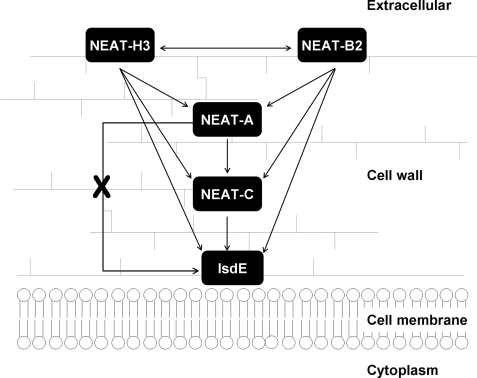

In this study, we report experimental results that provide the first complete challenge of a proposed model for heme acquisition by Staphylococcus aureus via the Isd pathway first put forth by Mazmanian, S. K., Skaar, E. P., Gaspar, A. H., Humayun, M., Gornicki, P., Jelenska, J., Joachmiak, A., Missiakas, D. M., and Schneewind, O. (2003) Science 299, 906–909. The heme-binding NEAT domains of Isd proteins IsdA, IsdB (domain 2), IsdC, and HarA/IsdH (domain 3), and the heme-binding IsdE protein, were overexpressed and purified in apo (heme-free) form. Absorption and magnetic circular dichroism spectral data, together with electrospray ionization mass spectrometry were used to unambiguously identify that heme transfers from NEAT-A through NEAT-C to IsdE. Heme transfer was demonstrated to occur in a unidirectional fashion in the sequence NEAT-B2 → NEAT-A → NEAT-C → IsdE or, alternatively, initiating from NEAT-H3 instead of NEAT-B2: NEAT-H3 → NEAT-A → NEAT-C → IsdE. Under the conditions of our experiments, only NEAT-H3 and NEAT-B2 could transfer bidirectionally, which is in the reverse direction as well, and only with each other. Whereas apo-IsdE readily accepted heme from holo-NEAT-C, it would not accept heme from holo-NEAT-A. Heme transfer to IsdE requires the presence of holo-NEAT-C, in agreement with the proposal that IsdC serves as the central conduit of the heme transfer pathway. These experimental findings corroborate the heme transfer model first proposed by the Schneewind group. Our data show that heme transport from the wall-anchored IsdH/IsdB proteins proceeds directly to IsdE at the membrane and, for this to occur, we propose that specific protein-protein interactions must take place.

Staphylococcus aureus is widely known as an important human pathogen that causes a range of infections and diseases from minor, such as impetigo and abscesses, to life-threatening, such as pneumonia, meningitis, endocarditis, and septicemia (1). The emergence of resistant bacteria has taken place over several decades and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA) are particularly clinically challenging, often accompanied by limited treatment options (2). Furthermore, MRSA, initially limited to hospitals, has since spread to the community (CA-MRSA). Adding to the complexity is our incomplete understanding of mechanisms of drug resistance.

Iron is an essential nutrient for the majority of living organisms. Although the human body contains abundant iron, its low solubility in the ferric state of aerobic systems and the fact that the majority is intracellular means that very little soluble iron (estimated as ∼10–9 m) is directly available to bacteria. As such, bacteria have developed multiple iron acquisition systems to facilitate their survival in such low iron environments. The most abundant potential iron source for bacteria is heme, or iron-protoporphyrin IX, which is typically bound in proteins such as hemoglobin and myoglobin. Pathogenic bacteria have evolved specialized mechanisms for acquiring heme-iron from the host (for recent reviews, see Refs. 3, 4–6).

The iron-regulated surface determinant (isd)3 gene cluster was first identified in 2002 (7–9), and then in 2003, Mazmanian et al. (10) were the first to propose that the Isd series of proteins formulate a heme transfer pathway across the cell wall and through the membrane. In recent years, there has been a significant amount of research into defining the Isd-mediated heme acquisition system, especially in S. aureus. Briefly, the Isd system in S. aureus consists of nine iron-regulated proteins: IsdA, IsdB, IsdC, and IsdH/HarA, which are cell wall-anchored surface proteins, and IsdDEF, which constitute a membrane-localized transporter, and, finally, IsdG and IsdI, which encode heme-degrading enzymes in the cytoplasm (12). IsdA is highly expressed on the cell wall of iron-limited S. aureus and, in addition to several other reported functions (13–15), is effective at scavenging heme (16, 17). Additional reported functions of Isd proteins include the binding by IsdB of hemoglobin (18), IsdH/HarA-dependent binding of haptoglobin and haptoglobin-hemoglobin (19), and heme binding by IsdC and IsdE (20–23). IsdE, a lipoprotein and a member of the bi-lobed, α-helical backbone family of substrate-binding proteins, binds heme into a shallow groove between the two lobes of the protein, using His and Met to coordinate to the heme-iron (22). Conversely, proteins IsdA, IsdB, IsdC, and IsdH/HarA each contain at least one so-called Near Transporter (NEAT) domain that adopt a β-sandwich structure to bind one heme into a groove with heme-iron coordination via Tyr (17, 21).

Together, the series of Isd proteins in S. aureus are believed to interact with heme proteins, extract the heme molecule, and transport it across the cell wall through to the membrane where it is then translocated into the cytoplasm (for a recent review, please refer to Ref. 11). As described above, substrate binding by individual components has been demonstrated, as has the heme-degrading ability of IsdG and IsdI (12). Most recently, Liu et al. (24) used UV-visible absorption spectroscopy to demonstrate that heme transfers from IsdA to IsdC.

In this report, we describe the use of detailed magnetic circular dichroism (MCD) spectral data together with electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) to unambiguously determine the products, or lack of products, when a heme donor (i.e. heme-bound protein) and heme accepter (i.e. apo-protein) are mixed. MCD spectroscopy has been shown in many reports, and by us in reports describing the heme binding environment of both the complete proteins IsdA, IsdB, IsdC, IsdE, and as well the isolated NEAT domains of IsdA, IsdB (domain 2), IsdH (domain 3), and IsdC to exhibit parameters sensitive to the heme-binding axial ligands, oxidation state, and spin state (16, 20, 23, 25–29).4 Previous reports of the mass spectral data have shown that the heme-free native apo-protein can be readily distinguished from the heme-free denatured apo-protein and the native, heme-bound holo-proteins (16, 27, 28). Extending the power of these two tools, we now demonstrate, for the first time, direct evidence for an ordered, multiprotein, heme transfer system between the Gram-positive bacterial surface Isd proteins. Key to these experiments is that the MCD signal intensity is a fingerprint of the oxidation state, spin state, and ligation state of the heme-iron and that the ESI-MS technique indicates possible changes in folding as a function of heme binding. For mixtures, the ESI-MS data show all components in their relative fractions, so in total in heme exchange reactions, heme binding between the very similar NEAT-containing Isd proteins and the IsdE protein can all be clearly identified, thus providing unambiguous information on the heme transfer.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Gene Cloning—DNA encoding residues 62–184 of IsdA, residues 337–462 of IsdB, residues 28–150 of IsdC, residues 539–658 of IsdH/HarA, and residues 32–292 of IsdE were PCR-amplified from S. aureus RN6390 chromosome and cloned into pET28(+) in such a way as to incorporate N-terminal His6 tags. DNA encoded His-tagged protein was digested out of pET28a(+) and cloned into pBAD30 (31) before being introduced into Escherichiacoli RP523, a hemB mutant (32). Over the course of the study, two different cloning methods were used to generate each of His-tagged IsdB-NEAT-domain 2 and IsdH-NEAT-domain 3, resulting in a slight difference in amino acid composition in the His tag region of recombinant protein (i.e. non-Isd protein sequence) even after thrombin cleavage. The sensitivity of MS illustrates these differences in mass. Construct 1 of each of the two proteins was used in Figs. 1 and 5, and construct 2 was used in Figs. 8 and 9. There was no change in heme binding properties between the two constructs.

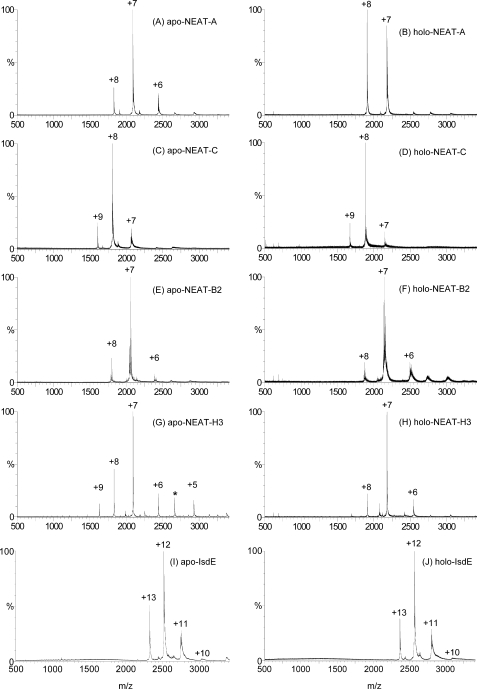

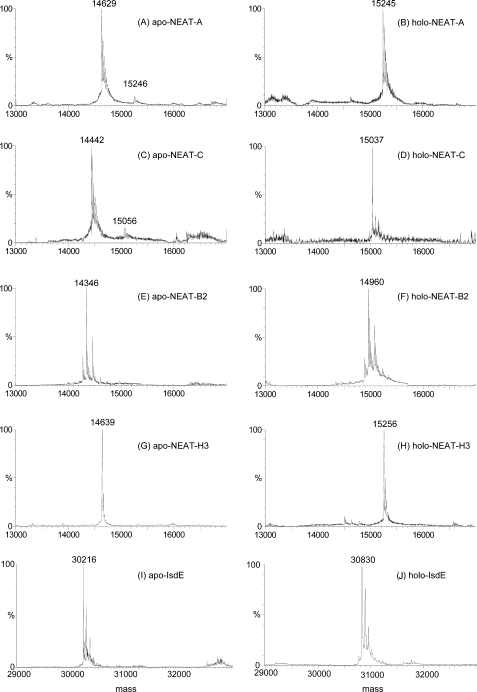

FIGURE 1.

ESI-MS charge state spectra for four Isd NEAT domains and IsdE studied as the heme-free, apo-NEAT-A, -NEAT-C, -NEAT-B2, -NEAT-H3, and -IsdE species (A, C, E, G, I) and the heme-bound, holo-NEAT-A, -NEAT-C, -NEAT-B2, -NEAT-H3, and -IsdE species (B, D, F, H, J). The charge states provide information about the change in conformation associated with heme binding. The close similarities in charge state distribution between the apo-and holo-pairs of data show that the proteins do not significantly change in folding following heme binding. Each charge state arises from the same protein mass, as shown in Fig. 2. The peak marked with * between +6 and +5 in G arises from an unknown identified species that is not seen in the holo-NEAT-H3 (H); the lack of corresponding mass in the deconvoluted spectra in Fig. 2G suggests a low molecular mass species.

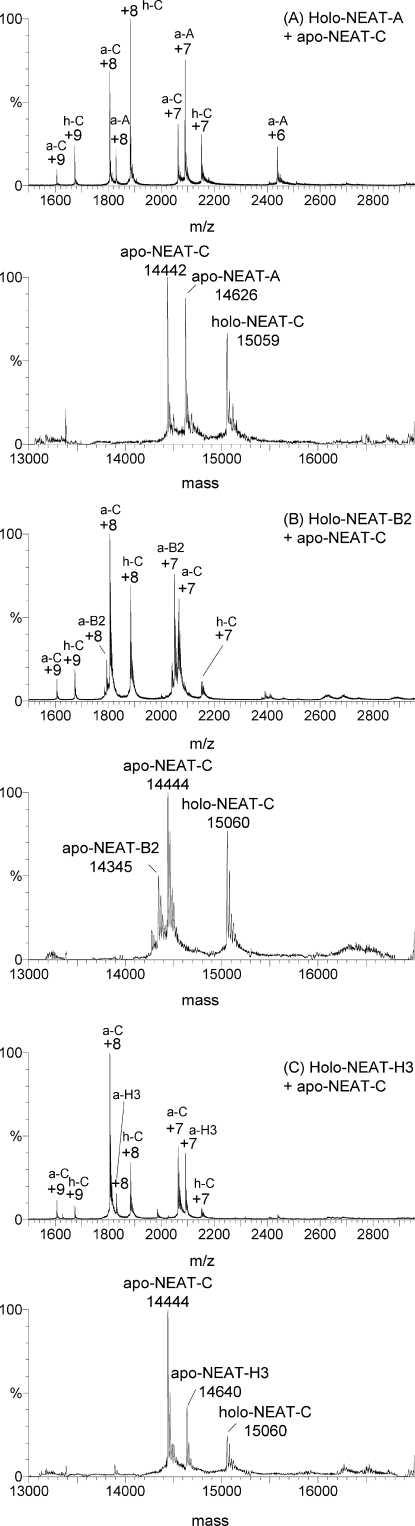

FIGURE 5.

Mass spectral data for solution of mixed proteins showing heme transfer from the Isd holo-NEAT domains (A, B2, and H3) to apo-NEAT-C. A, charge state and deconvoluted mass spectra measured for a mixture of heme-containing, Isd holo-NEAT-A, and apo-NEAT-C. Excess heme-free, apo-NEAT-C was added. Three species coexist in solution and are identified in the charge state spectra with the abbreviations for apo-NEAT-C (a-C; with a mass of 14,442), apo-NEAT-A (a-A; with a mass of 14,626), and holo-NEAT-C (h-C; with a mass of 15,059). B, charge state and deconvoluted mass spectra measured for a mixture of heme-containing, Isd holo-NEAT-B2, and apo-NEAT-C. Excess heme-free, apo-NEAT-C was added. Three species coexist in solution and are identified in the charge state spectra with the abbreviations for apo-NEAT-B2 (a-B2; with a mass of 14,345), apo-NEAT-C (a-C; with a mass of 14,444), and holo-NEAT-C (h-C; with a mass of 15,060). C, charge state and deconvoluted mass spectra measured for a mixture of heme-containing, Isd holo-NEAT-H3 and apo-NEAT-C. Excess heme-free, apo-NEAT-C was added. Three species coexist in solution and are identified in the charge state spectra with the abbreviations for apo-NEAT-H3 (a-H3; with a mass of 14,640), apo-NEAT-C (a-C; with a mass of 14,444), and holo-NEAT-C (h-C; with a mass of 15,060). In each case, heme transfer to Isd NEAT-C was observed, resulting in a mixture of the heme-free-Isd-NEAT domain of NEAT-A, NEAT-B2, NEAT-H3) and heme-free apo-NEAT-C and heme-bound-holo-NEAT-C. No heme-bound-holo-NEAT-A (at 15,245 Da), NEAT-B2 (at 14,960 Da), or NEAT-H3 (at 15,256 Da) was observed in their respective mass spectra following mixing with apo-NEAT-C. The difference in relative %-abundances of the proteins depends on the relative efficiencies of the charged proteins reaching the detector in competition with the other ions. Closely similar ratios of protein were used in each of the spectral data shown here. In each case, excess (∼1.5×) of the heme-acceptor protein was used, so that there was also apo-heme-free protein remaining.

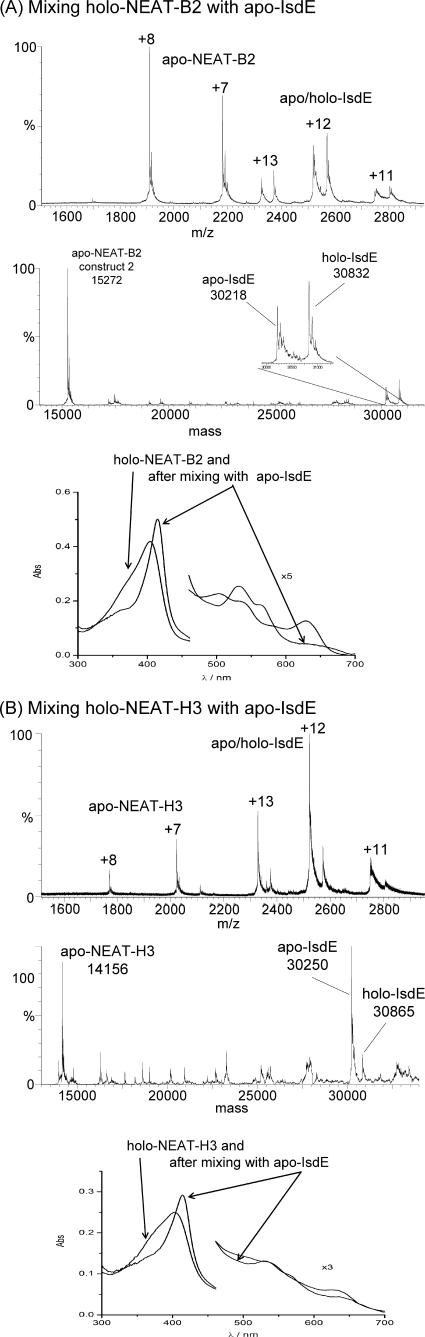

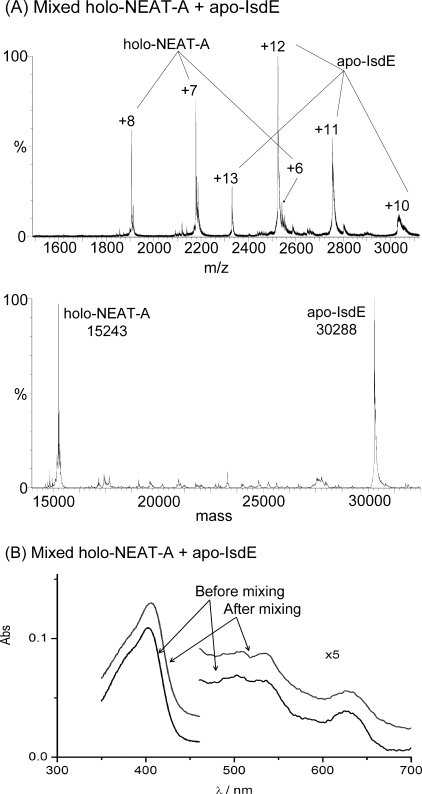

FIGURE 8.

Heme transfer from holo-NEAT-B2 and holo-NEAT-H3 to apo-IsdE. Charge state and deconvoluted mass spectra and absorption spectra measured for mixtures of A holo-NEAT-B2 with apo-IsdE as a heme acceptor and B holo-NEAT-H3 with apo-IsdE as a heme acceptor. In A, the data show that holo-NEAT-B2 transfers heme to apo-IsdE. In each mass spectrum are peaks that correspond to both the holo-and apo-proteins: peaks that correspond to apo-IsdE (+11 to +13) at 30,218 Da, peaks that correspond to holo-IsdE (+11 to +13) at 30,832 Da and peaks that correspond to apo-NEAT-B2 (+7 to +8) at 15,272 Da. The absorption spectra represent the holo-NEAT-B2 before the addition of IsdE (indicated by the arrow from the legend holo-NEAT-B2) and following mixing with IsdE for 25 min (indicated by the arrows from the legend after mixing with apo-IsdE). The holo-NEAT-B2 was formed by binding heme to heme-free, apo-NEAT-B2 (construct 2), which was made using a different cloning strategy than that used to make NEAT-B2 which was used for the data in Figs. 1, 2, and 5. Residues in the His tag region (non-Isd) differ between the two constructs (see “Experimental Procedures”). The experimental results were unchanged by the use of the second construct. In B, the data show that holo-NEAT-H3 transfers heme to apo-IsdE. In each mass spectrum are peaks that correspond to both the holo-and apo-proteins: peaks that correspond to apo-IsdE (+11 to +13) at 30,250 Da, peaks that correspond to holo-IsdE (+11 to +13) at 30,865 Da and peaks that correspond to apo-NEAT-H3 (+7 to +8) at 14,156 Da. The absorption spectra of the holo-NEAT-H3 before the addition of IsdE (indicated by arrows from the legend holo-NEAT-H3) and following mixing with apo-IsdE for 25 min (indicated by arrows from the legend after mixing with apo-IsdE). The final spectrum corresponds to that of heme-containing, holo-IsdE. The apo-NEAT-H3 (construct 2) was made using a different cloning procedure than that used for the NEAT-H3 which was used to generate the data shown in Figs. 1, 2, and 5. Residues in the His tag region (non-Isd) were altered between the two constructs (see “Experimental Procedures”). The experimental results were unchanged by the use of the second construct.

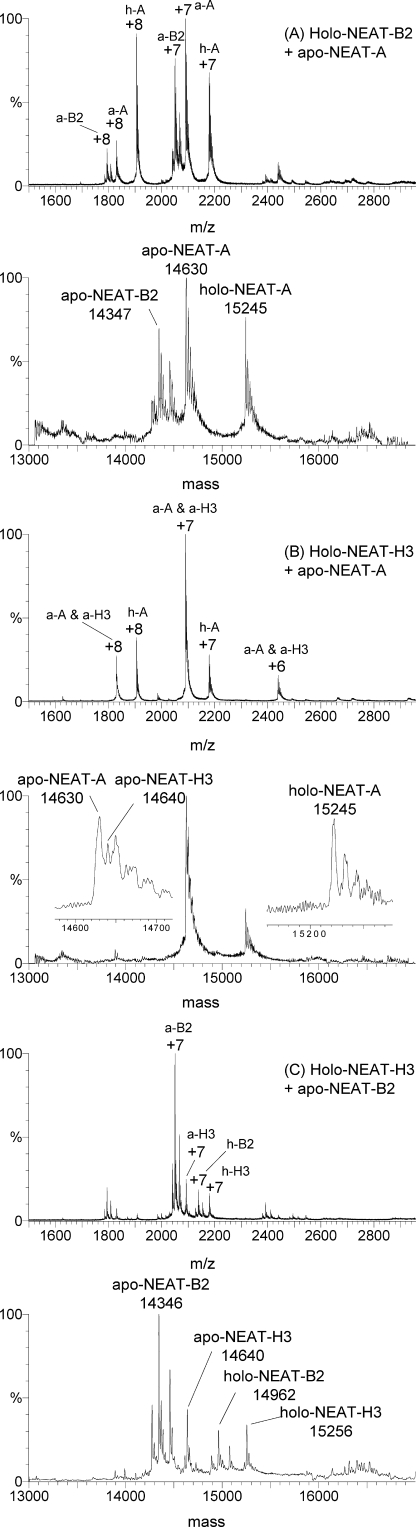

FIGURE 9.

Heme transfer from holo-NEAT-B2 to apo-NEAT-A, and holo-NEAT-H3 to apo-NEAT-A and NEAT-B2. Charge state and deconvoluted mass spectra, and absorption spectra measured for mixtures of (A) holo-NEAT-B2 with apo-NEAT-A as a heme acceptor, (B) holo-NEAT-H3 with apo-NEAT-A as a heme acceptor, and (C) holo-NEAT-H3 with apo-NEAT-B2 as heme acceptor. In A, the data show that holo-NEAT-B2 transfers heme to apo-NEAT-A. In each mass spectrum are peaks that correspond to both the holo-and apo-proteins: peaks in the mass spectra that correspond to apo-NEAT-A (a-A: +7 and +8) at 14,630 Da, peaks that correspond to holo-NEAT-A (h-A: +7 and +8) at 15,245 Da and peaks that correspond to apo-NEAT-B2 (a-B2: +7 to +8) at 14,347 Da. In B, the data show that holo-NEAT-B2 transfers heme to apo-NEAT-A. In each mass spectrum are peaks that correspond to both the holo-and apo-proteins: peaks that correspond to apo-NEAT-A (a-A: +7 and +8) at 14,630 Da, peaks that correspond to holo-NEAT-A (h-A: +7 and +8) at 15,245 Da and peaks that correspond to apo-NEAT-H3 (a-H3: +7 to +8) at 14,640 Da. In C, the data show that holo-NEAT-H3 transfers heme to apo-NEAT-B2. In each mass spectrum are peaks that correspond to both the holo- and apo-proteins: peaks that correspond to apo-NEAT-B2 (a-B2: +7 and +8) at 14,346 Da, peaks that correspond to holo-NEAT-B2 (h-B2: +7 and +8) at 14,962 Da, and peaks that correspond to holo-NEAT-H3 (h-H3: +7) at 15,256 Da, and to apo-NEAT-H3 (a-H3: +7 to +8) at 14,640 Da.

Protein Expression and Purification—E. coli RP523 cells harboring recombinant plasmids were grown at 30 °C in Luria-Bertani broth (LB; Difco) containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and l-arabinose (0.2%). After overnight incubation, cells were harvested and resuspended in binding buffer (20 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.4, 500 mm NaCl, 10 mm imidazole). Cells were then ruptured in a French pressure cell, and cell lysates were subjected to ultracentrifugation at 150,000 × g for 1 h to remove insoluble material. Proteins were purified using a 1-ml HisTrap column (GE Healthcare) and anÄKTA FPLC system with an elution buffer containing 20 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.4, 500 mm NaCl, 500 mm imidazole. Proteins were then desalted using a 5-ml HiTrap Desalting column (GE Healthcare). The His6 tags were removed by incubation with thrombin (10 units/mg protein; GE Healthcare) at room temperature for 16 h and run through a HisTrap column for final purification.

Hemin (Sigma) was dissolved in DMSO for estimation of solution concentrations. Hemin concentrations in DMSO were calculated using the extinction coefficients 10.74 mm–1 cm–1 at 501 nm, and 6.23 mm–1 cm–1 at 624 nm. These values were determined using the pyridine hemochrome test as a reference, using ε526 = 16.99 mm–1 cm–1 and ε526 = 16.99 mm–1 cm–1 for pyridine hemochrome (33). Protein concentrations were estimated using the extinction coefficients at 280 nm of 15.48 mm–1 cm–1 for myoglobin, 15.93 mm–1 cm–1 for NEAT-A and for NEAT-C, and 14.65 mm–1 cm–1 NEAT-B2, 18.49 mm–1 cm–1 for NEAT-H3. Because of the lack of tryptophan residues in IsdE, mass spectrometry was used to estimate protein concentrations using a NEAT domain sample as reference point. Protein samples in 1× phosphate-buffered saline buffer were incubated with 1.5× molar excess hemin dissolved in DMSO. Samples were then concentrated to ∼100 μm and purified using G-25 size exclusion chromatography. Mass spectra of collected samples were run to ensure that free heme was effectively removed.

Magnetic Circular Dichroism Measurements—Protein solutions were prepared in a 1× phosphate-buffered saline buffer at pH 7.4. Measurements at room temperature were made in 1-cm cuvettes at 5.5 T in an Oxford Instruments SM2 superconducting magnet, aligned in a Jasco J810 CD instrument. Peak absorbance was always below 0.8 near 400 nm. Absorption measurements were made using the Cary 500 (Varian, Canada). All solutions were measured in the Cary 500 before and after being measured in the MCD spectrometer. No changes were observed.

ESI-MS Measurements—A Micromass LC-T instrument was used with sample infusion through a microliter pump. The mass spectrometer settings were: capillary +3,300 V, sample cone: 75–100 V, desolvation temperature: 20 °C, source temperature: 80 °C. Samples were infused at rates of ∼10 μl/min. Averaging was carried out for several minutes. Max Ent 1 (Micromass) software was used to calculate the deconvoluted parent spectrum.

ESI-MS Sample Preparation—Stock protein solutions in phosphate-buffered saline were concentrated using centrifuge concentration tubes (Millipore) to ∼100 μm. Buffer exchange to 20 mm ammonium formate (pH 7.3) was performed using G-25 size exclusion chromatography.

Heme Transfer Reactions—To monitor heme transfer between the two NEAT domains (NEAT-A and NEAT-C) and IsdE, the protein samples were mixed with an approximate 1.5× excess of the appropriate heme acceptor protein. The mixing times were varied from 10 min to 2 h. In all cases, the spectra remained the same.

RESULTS

ESI-MS as a Method to Discriminate Apo from Holo Isd Proteins—The heme-binding NEAT domains from IsdA (NEAT-A), IsdB (NEAT-B2), IsdC (NEAT-C), and HarA or IsdH (NEAT-H3), as well as IsdE were overexpressed in apo-form and purified. Holo-proteins were prepared by reconstitution of apo-proteins with hemin. The proteins were analyzed by mass spectrometry to confirm that each was heme-free (apo) or homogeneously heme-bound (holo), and to establish the number of heme molecules bound to each protein. The mass spectral data are shown as the charge states in Fig. 1 with the deconvoluted spectra in Fig. 2.

FIGURE 2.

Deconvoluted ESI-mass spectra of the heme-free Isd apo-NEAT-A, -NEAT-C, -NEAT-B2, -NEAT-H3, and -IsdE species (A, C, E, G, I) and Isd heme-bound-NEAT-A, -NEAT-C, -NEAT-B2, -NEAT-H3, and -IsdE species (B, D, F, H, J). The data show that only one heme binds to each of these species. The mass difference between the pairs of data for the apo- and holo-species is ∼616 Da, the mass of a single heme.

Charge states in ESI-MS provide an indication of the volume of the protein or solvent access to the protein basic amino acid residues (28). In Fig. 1, the lack of changes in charge state distribution between the apo- and holo-species for NEAT-B2, and NEAT-C, in addition to the data previously published for IsdE (28), indicates that no significant structural changes take place with heme binding in any of these proteins. The ESI-MS data in Fig. 1B, see Fig. 1A, indicate that there is a very slight change in conformation of NEAT-A upon heme binding, because the charge state maximum increases to +8 from +7, suggesting solvent exposure of one additional basic residue when the heme binds. Similarly, we note the change in the relative magnitude of the +9 and +8 charge states in Fig. 1G (see Fig. 1H for apo- and holo-NEAT-H3), respectively; again, the implication is that there are conformational changes upon binding the heme in holo-NEAT-H3, which, in this case, cause a reduction of solvent exposure. Compared with changes that take place following acid-induced denaturation of, for example, IsdE (28), the changes in conformation of NEAT-A and NEAT-H3 with heme binding are small, but real, and for NEAT-A in agreement with the published crystal structures of the holo versus apo forms of the protein (17).

Following heme loading, mass spectrometry was used again to confirm that the holo-proteins were formed (Fig. 2, A–J). The mass spectral data provide important evidence that the holo-proteins were the only source of heme in the transfer reactions because of the lack of a mass near 616 Da (data not shown). This is an important test, as we have observed that absorption spectroscopy is not a reliable technique to ensure the complete uptake and hence removal of free heme from a solution. The Soret band of free heme can appear as a blue-shifted shoulder on the Soret band of bound-heme and may be confused with its vibronic band, yielding complications in assessing heme transfer reactions spectroscopically. Moreover, because each of the heme-binding Isd NEAT domains possess heme-binding characteristics that result in similar optical properties, quantifying heme transfer proves very difficult. Table 1 summarizes the UV-visible absorption band maxima for each of the heme-binding NEAT domains and IsdE. Given that the absorption spectroscopic properties of the hemes bound in IsdA, IsdB NEAT domain 2, IsdC, and IsdH NEAT domain 3 are all very similar, monitoring NEAT domain heme transfer reactions solely via absorption spectroscopy is, therefore, ambiguous and likely to be imprecise as the spectral envelopes of the reactants and products significantly overlap.

TABLE 1.

Absorption spectra properties for the heme-bound NEAT domains of IsdA, IsdB-domain2, IsdC, and IsdH-domain 3, and IsdE

Magnetic circular dichroism spectra do, however, exhibit additional assignment criteria that provide far more information from heme-containing proteins, and we have demonstrated this sensitivity with both the full-length proteins and the isolated NEAT domains (16, 27, 28). When the data from MCD measurements are combined with mass spectrometric data, heme transfer reactions can be studied in detail, and all protein species present can be identified together with their relative concentrations.

The key focus of this study was determining the ability of heme to transfer among Isd proteins to directly address the hypothesis that the proteins function in concert as a heme shuttle system in the Gram-positive bacterial cell wall. A key test is whether the transfer reactions are quite general and independent of the donor or, on the other hand, highly specific to the heme donor as would be the case if specific protein-protein interactions were involved. Because each NEAT domain contains a distinct amino acid composition and, therefore, a distinct mass (making mass spectral peak assignment straightforward; demonstrated in Fig. 2), heme transfer reactions could therefore readily be followed using the MS technique. However, it was important to verify any MS results with other techniques that have been previously used to study heme proteins, including absorption spectroscopy and magnetic circular dichroism spectroscopy.

Magnetic Circular Dichroism Spectral Data Indicate That Heme Transfer Takes Place from NEAT-A through NEAT-C to IsdE—Whereas the optical spectral properties of the heme-bound NEAT domains are very similar due to the similarity in axial ligation of the heme-iron, IsdE contains a novel heme-binding domain, which is quite distinct from the NEAT domains and, as a result, exhibits a very different absorption and MCD spectrum (see Table 1). Indeed, IsdE coordinates a single heme using both a histidine and a methionine residue, whereas the NEAT domains bind a single heme using a proximal tyrosine for heme-iron coordination (16, 17, 21, 22, 28). The Soret absorption band is red-shifted to 415 nm for IsdE, significantly separated from the ∼404-nm Soret band of the NEAT domains. Heme transfer reactions could, therefore, be monitored using UV-visible absorption spectroscopy for NEAT-X-IsdE transfer reactions.

Despite the close similarity in absorption spectral properties between NEAT-A and NEAT-C, the MCD spectral properties are slightly different because the heme-iron in NEAT-C is slightly lower spin than in NEAT-A, so the Soret region MCD bands distinctly change. Fig. 3A shows the sequence of spectra recorded for holo-NEAT-A in the presence of increasing concentrations of apo-NEAT-C. Clearly, there is a change in the spectra but based on these data alone, it was ambiguous as to whether heme transfer took place. However, unambiguous data showing heme transfer in this reaction was obtained from the ESI-MS data shown below, confirming that the heme in NEAT-A transferred stoichiometrically to apo-NEAT-C. In other words, while the absorption data recorded for this transfer are very poor discriminators, and even the MCD data provide imprecise data, the ESI-MS data provide definitive data to support the conclusion that heme transfer took place.

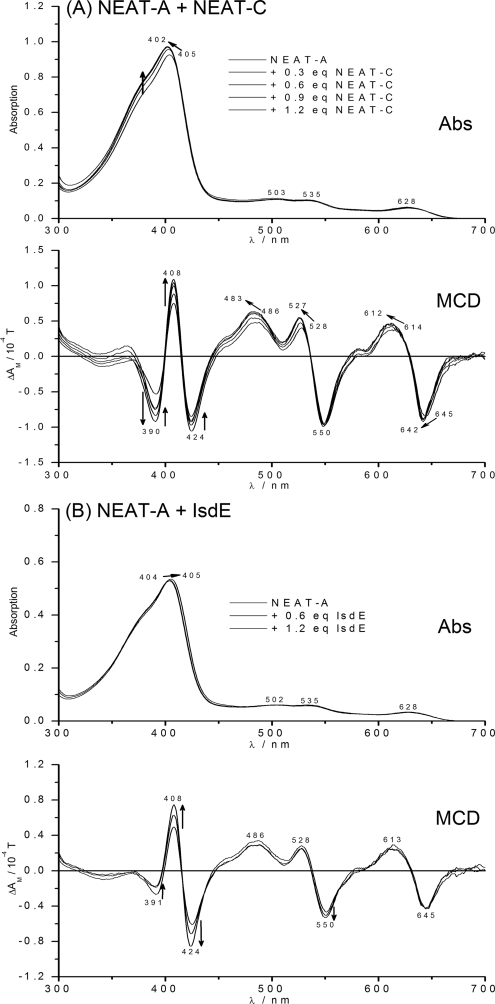

FIGURE 3.

Absorption and MCD spectra recorded for heme transfer from Isd holo-NEAT-A to Isd apo-NEAT-C and for a mixed solution of Isd holo-NEAT-A and apo-IsdE. A, changes in the spectra when apo-NEAT-C is added to holo-NEAT-A in steps of 0.3 mol eq. Lines are shown for additions to: 0, 0.3, 0.6, 0.9, and 1.2 mol eq. apo-IsdE. The spectra have been corrected for dilution effects. In the absorption spectrum, the only significant change is the increase in absorbance at 390 nm and the slight blue shift from 405 to 402 nm; as marked by arrows. There is more change in the MCD spectrum because the MCD spectrum of the holo-NEAT-C product is slightly blue-shifted when compared with the holo-NEAT-A reactant, and also exhibits a more prominent negative signal at 390 nm, a more positive signal at 408, and a less negative signal at 424 nm than holo-NEAT-C resulting in a significant change in the intensities of the bands at these wavelengths as the reaction proceeds. B, absorption and MCD spectra recorded when heme-free, apo-IsdE was added to a solution of heme-containing, Isd holo-NEAT-A. Three sets of spectra are shown: with a total of 0, 0.6, and 1.2 mol. eq. IsdE added. Whereas there is little change in the absorption spectrum, addition of apo-IsdE results in intensification of the Soret MCD band envelope centered on 416 nm, a sign of increased low spin contribution in the ferric heme. There is no indication of the distinctly different absorption and MCD spectra of heme-containing, holo-IsdE. The changes are a result of interactions between the two proteins. Mass spectral data in Fig. 7 also clearly show that no heme transfer took place and that the solution after mixing contains only holo-NEAT-A and apo-IsdE.

Fig. 3B shows that the effect of adding apo-IsdE to holo-NEAT-A is essentially negligible in the absorption spectrum but is actually quite significant in the MCD spectrum. The MCD data clearly show that the heme does not transfer from NEAT-A to IsdE. However, an interesting finding was that the MCD data show that spectral changes do take place at the heme site in holo-NEAT-A (despite the fact that heme is not removed), which can be associated with a decrease in the high spin g factor of the ferric ground state, a situation encountered when a weak field ligand is replaced by a slightly stronger field ligand. The ESI-MS data described below confirm that no heme transfer took place between NEAT-A and IsdE, but, unlike the data obtained from MCD, do not discriminate the fact that an interaction between the two proteins does occur.

Fig. 4 is one of the key experiments in this study, because the MCD spectra shown follow the spectral changes arising from heme transfer as increasing concentrations of apo-IsdE are added to a solution of holo-NEAT-A and apo-NEAT-C (the same solution as that used to generate the spectral data shown in Fig. 3A, in fact, as shown conclusively above, that solution rapidly shifts to apo-NEAT-A and holo-NEAT-C). Because the spectral properties of the heme in holo-IsdE are completely different than when the heme is bound in either holo-NEAT-A or holo-NEAT-C, there are dramatic and systematic changes that are observed in both the absorption and MCD spectra. These data emphasize that transfers between NEAT domains are difficult to quantify by optical measurements alone, but that heme transfer to IsdE is readily measurable, and the MCD spectra provide clear assignment criteria with respect to the exact heme-containing protein at the end of the reaction.

FIGURE 4.

Changes in the absorption and magnetic circular dichroism spectra when heme-free, apo-IsdE is added to a solution of heme-containing, Isd holo-NEAT-A, and apo-NEAT-C (the solution used in Fig. 3A). Isosbestic change in spectral properties indicates the formation of heme-containing, holo-IsdE that was transferred from the holo-NEAT-A, to the apo-NEAT-C, then to the apo-IsdE. Spectra are shown for solutions with a total of: 0, 0.3, 0.6, 0.9, 1.2, and 2.1 mol eq apo-IsdE added. The lines show the direction of the spectral changes. The final absorption and MCD spectra closely resemble those of heme-loaded-IsdE (holo-IsdE).

In the following sections, we report the use of the ESI-MS technique to unambiguously demonstrate that specific heme transfer reactions occur between the NEAT domains of IsdH (domain 3), IsdB (domain 2), IsdA, and IsdC, and the IsdE protein.

Apo-NEAT-C Efficiently Removes Heme from Holo-NEAT-A, Holo-NEAT-B2, and Holo-NEAT-H3—In Fig. 5, we show using mass spectral data that heme is transferred directly, rapidly, and completely from each of holo-NEAT-A (A), holo-NEAT-B2 (B), and holo-NEAT-H3 (C) to apo-NEAT-C. The heme donor proteins were mixed with a ∼1.5× excess of the heme acceptor protein. Three major peaks are seen in each of the deconvoluted spectra (lower panels in A, B, and C in Fig. 5), which are associated with: (i) the heme-free form of the donor, (ii) the heme-free form of the acceptor, and (iii) the heme-bound form of the acceptor. No remaining heme-bound form of the donor is observed (see Fig. 2 for the masses of the holo species). We should point out that the relative magnitudes of the % abundances cannot be used to determine relative concentrations between different proteins because the uptake by the mass spectrometer is different for each protein. However, the relative concentrations of the heme-bound and heme-free species of the same protein can be related. In these data even though the apo- and holo-masses might be close, there is no direct overlap and within the precision of the experiment only three separate species can be identified.

If the reverse reaction occurred in the presence of holo-acceptor protein, then four species would be observed because none of the possible protein species would be completely removed from solution. This was observed for only one experiment: namely for the heme transfer between NEAT-B2 and NEAT-H3, described below.

Our conclusions from these data are that, unlike the ambiguous data obtained from absorption and MCD spectra, the ESI-MS data unambiguously show that heme was transferred to apo-NEAT-C in every case. We next tested the heme-transfer hypothesis and the MCD data described above, by adding IsdE to these solutions.

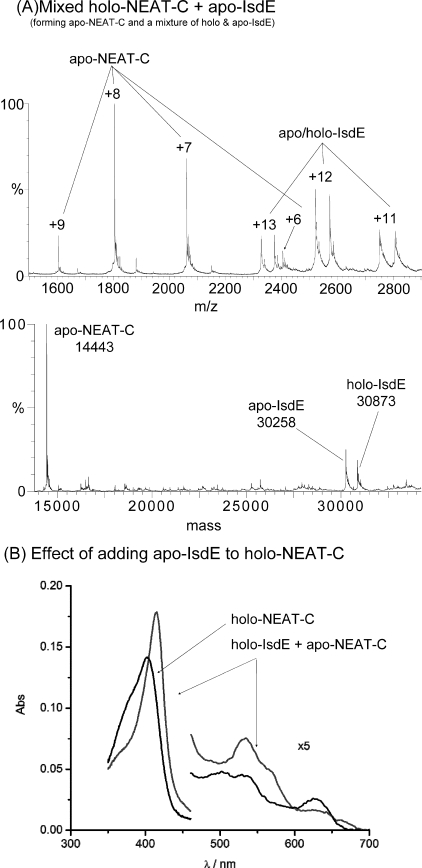

ESI-MS Data Show That Apo-IsdE Efficiently Removes Heme from Holo-NEAT-C, -B2, and H3—Fig. 6 consolidates two experiments; in part A, we show the mass spectral data recorded following mixing of holo-NEAT-C and apo-IsdE and, in part B, we show the separate absorption spectra for the two heme-bound proteins, holo-NEAT-C and holo-IsdE after heme transfer from the holo-NEAT-C. First, the mass spectral data (Fig. 6A) shows that NEAT-C-bound heme was transferred entirely to apo-IsdE. Only apo-NEAT-C at 14,443 Da, apo-IsdE at 30,258 Da, and holo-IsdE, 615 Da heavier at 30,873 Da, are identified. The 616 Da mass is quite small with respect to the apo-heme-free mass of IsdE, so the charge states overlap, and we observe a duplication from +11 to +13. There is only one set of charge states for the NEAT-C as there is no holo-NEAT-C remaining. The +6 charge state overlaps with the +13 of IsdE. Inspection of the charge states illustrate how heme binding does not change the overall conformation of either IsdE or NEAT-C significantly (Fig. 6A, see Fig. 1), because the +12 state for IsdE and +8 for NEAT-C remain predominant following heme binding. The absorption spectra in Fig. 6B show how the Soret band for holo-NEAT-C red shifts when apo-IsdE is added. For this combination, the absorption spectra are different because the maximum of IsdE lies ∼12 nm to the red near 415 nm, Table 1.

FIGURE 6.

Heme transfer from holo-NEAT-C to apo-IsdE. A, charge state and deconvoluted mass spectra of the solution made by mixing holo-NEAT-C and apo-IsdE. Excess apo-IsdE was added. B, absorption spectra of holo-NEAT-C before (indicated by arrows) and following the addition of apo-IsdE. The significant change in the Soret band maxima following heme transfer to the apo-IsdE (indicated by arrows from the legend'holo-IsdE + apo-NEAT-C') means that for this heme transfer experiment, absorption spectra can be used to monitor the progress of the reaction. The absorption spectrum of holo-IsdE is quite different from that of either apo-NEAT-C or holo-NEAT-C.

Apo-IsdE Does Not Accept Heme from Holo-NEAT-A—The ESI-MS data in Fig. 7A show that there is no heme transfer when apo-IsdE is mixed with holo-NEAT-A. This is the only scenario (other than with holo-myoglobin, data not shown), where we observed no transfer to the heme-free Isd acceptor protein at all. (We note slight changes in deconvoluted masses arise from both uncertainty in the experimental masses of the charge states and from the presence of adducts; however, there is no ambiguity in the identity of the protein species, and especially, the heme-free nature of the apo-IsdE.) This lack of transfer is emphasized in the absorption spectra (Fig. 7B) where the spectrum of holo-NEAT-A mixed with apo-IsdE is exactly the same as holo-NEAT-A, quite unlike the case in all the other spectra shown previously. However, recall that the MCD spectra in Fig. 4 suggest that there is interaction between these two proteins, but without transfer of the heme.

FIGURE 7.

Demonstration that no heme transfer takes place from holo-NEAT-A to apo-IsdE. A, ESI-MS spectra (charge states and deconvolution) for a mixture of holo-NEAT-A and apo-IsdE showing the presence of only holo-NEAT-A and apo-IsdE; there is no indication of the presence of either apo-NEAT-A or holo-IsdE showing that no heme transfer took place. B, the absorption spectra recorded before and after addition of the apo-IsdE are characteristic of holo-NEAT-A for both solutions. There is no indication of formation of holo-IsdE, which has a significantly different absorption spectrum.

Apo-IsdE Accepts Heme from Holo-NEAT-B2 and Holo-NEAT-H3—The ESI-MS data in Fig. 8 show unambiguously that heme, whether it was initially in NEAT-B2 (panel A) or NEAT-H3 (panel B), was transferred rapidly and completely to apo-IsdE. The absorption spectra in Fig. 8, A and B again illustrate that when IsdE is the heme acceptor, there are significant differences in the absorption spectra. The spectra measured following mixing of holo-NEAT-B2 and apo-IsdE and of holo-NEAT-H3 and apo-IsdE are virtually identical, representing solely holo-IsdE.

Apo-NEAT-A Accepts Heme from Holo-NEAT-B2 and Holo-NEAT-H3—The ESI-MS data in Fig. 9, A and B show that the heme in holo-NEAT-B2 and holo-NEAT-H3 transfers to apo-NEAT-A. The transfer from holo-NEAT-H3 to apo-NEAT-B2 is inefficient because the data in Fig. 9C show the presence of all four species.

DISCUSSION

The Isd series of proteins are proposed to represent a complete heme acquisition and transport system, together functioning to remove heme from proteins such as hemoglobin, then to shuttle heme across the Gram-positive bacterial cell wall right through to membrane ABC transporters, which translocate the heme molecule into the cytoplasm where it is eventually degraded by proteins IsdG and IsdI. While significant evidence now exists demonstrating substrate binding for the various proteins (10, 12, 16–18, 20–22, 24, 27, 28, 34), the first direct evidence for heme transfer between Isd proteins was only very recently obtained for the IsdA to IsdC transfer reaction (24). In the present study, a complete picture of heme transfer between all of the heme-binding Isd proteins that reside on the outside of the bacterial cell has been obtained for the first time.

All heme-binding Isd NEAT domains possess overlapping heme binding properties. Each has been shown to coordinate a single, 5-coordinate, high-spin ferric heme through a conserved tyrosine residue (16, 17, 21, 27) and, as such, the absorption spectroscopic properties of the hemes bound in IsdA, IsdB, IsdC, and IsdH are all very similar. The spectroscopic and structural data reported to date do not provide information on the process or mechanism that would be required if the Isd proteins are to capture and transfer heme molecules. Although the heme binding properties of the NEAT domains appear very similar, the data presented here show that the NEAT domains do, in fact, possess distinct qualities. The majority of heme transfer reactions occurred rapidly and in a unidirectional fashion (except for the transfer between NEAT-B2 and NEAT-H3) and, in the case of IsdA, very selectively via apo-NEAT-C toward heme-free IsdE.

It is important to note that none of the Isd proteins used in this study were capable of extracting heme from holo-myoglobin under these same conditions (data not shown). The oxidation state of the heme in myoglobin did not alter the results, as neither ferric nor ferrous hemes could not be removed (data not shown). Together, the results suggest that specific protein-protein interactions must occur to promote the removal of heme from Isd proteins, since concentrations of free heme were extremely low and if protein:protein reactions were not to occur, would result in very slow transfer rates. Experimentally, this is not what was observed. Also, in the absence of protein-protein interactions we would expect to observe in both optical data (especially the MCD spectra) and ESI-mass spectra, mixtures indicating the presence of equilibria. We see no evidence for significant concentrations of both donor and acceptor. It is likely, then, that one or more of the remaining, non-heme-binding NEAT domains, that is, NEAT-B1 and/or NEAT-H1 or NEAT-H2 play crucial roles in extracting heme from myoglobin or hemoglobin. In support of this, it is noteworthy that NEAT-B1 binds hemoglobin (18) whereas NEAT-H1 binds hemoglobin-haptoglobin (34). In the proposed Isd-mediated heme transport system, the surface-exposed Isd proteins interact with heme-containing proteins such as hemoglobin (IsdB) or hemoglobin-haptoglobin (IsdH), which are found in serum following erythrocyte lysis. Extraction of the heme then occurs, followed by heme transfer to other Isd proteins present in spatially arranged locations within the cell wall architecture.

Analysis of the optical data illustrates the difficulties in obtaining precise information for transfer between the NEAT domains. Even though the MCD spectra provide far more information, there is only a small change following transfer from holo-NEAT-A to apo-NEAT-C. The situation is far better when the transfer takes place to IsdE. The transfer to IsdE was further confirmed by absorption spectroscopy since a gradual shift of the Soret band from 404 to 415 nm was observed. On the other hand, the mass spectrometric data show that holo-NEAT-H3 transferred heme to all other NEAT domains as well as to IsdE. Holo-NEAT-B2 showed similar behavior, even supplying heme to apo-NEAT-H3 with heme. This was the only example of bidirectional heme transfer that was observed in this study and suggests that IsdB and IsdH are functionally closely related, in agreement with predictions based on bioinformatic analyses.

A key result of this study is that the IsdA NEAT domain (NEAT-A) behaved quite differently than either NEAT-B2 or NEAT-H3. NEAT-A accepted heme from NEAT-B2 and NEAT-H3 in a unidirectional fashion, and only transferred heme to NEAT-C not to apo-IsdE. All three techniques, mass spectrometry, MCD, and absorption spectroscopy, confirmed that IsdE was unable to accept heme from NEAT-A. Figs. 3B and 7 show the MCD and absorption spectra of holo-NEAT-A before and following the addition of excess apo-IsdE. No shift in the Soret band or any change in the visible region was observed. Mass spectrometry showed that even following 24 h of incubation of holo-NEAT-A with apo-IsdE, no sign of heme transfer was observed (data not shown). IsdC has been proposed to function as the central conduit in the cell wall for heme passage to the bacterial cell membrane. The ability of NEAT-C to accept heme from NEAT-A, NEAT-B2, and NEAT-H3 (Fig. 5) and to only transfer it to apo-IsdE (Figs. 4 and 6) offers strong support for this proposal; no increase in holo-IsdE was observed after incubation with holo-NEAT-A whereas a significant increase in holo-IsdE was obtained following incubation of apo-IsdE with holo-NEAT-C (Fig. 7, see Fig. 6).

In conclusion, the data presented here support a model for heme transport as illustrated in Fig. 10, in strong agreement with the proposal first offered by Mazmanian et al. (10). Of importance in these challenge experiments, is that the flow of heme is from the distally located IsdH (HarA) and IsdB through to the membrane-proximal IsdE protein. Key to the mechanistic analyses is that heme does not transfer from holo-Isd NEAT-A directly to apo-IsdE; apo-NEAT-C is the required facilitator. This fact, taken together with the demonstrated unidirectionality of the transfer reactions, suggests that specific protein-protein interactions must be a necessary part of the mechanism required to drive the heme transfer toward the membrane. During the review process of this report, a study relevant to this work became available on JBC Papers in Press (30).

FIGURE 10.

A heme transport model based on analysis of the magnetic circular dichroism and mass spectral data obtained from this study. Overall, heme transfer is from membrane distal IsdH/HarA (studied using NEAT domain H3) and IsdB (studied using the NEAT domain B2) proteins through to the membrane-proximal IsdE. There is unidirectional heme transfer from NEAT-A to NEAT-C to IsdE. There is no transfer from NEAT-A to IsdE. The mass spectral data to support the model are in agreement with the model first proposed by Schneewind and co-workers (10). The absorption and MCD data of the equilibrated solutions fully support the conclusions reached from analysis of the mass spectral data.

This work was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research operating grant (to D. E. H.), operating and equipment grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada (to M. J. S.), the NSERC Postgraduate Scholarship program (to M. P.), and the Ontario Graduate Scholarship program (to M. T. T.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: isd, iron-regulated surface determinant; MCD, magnetic CD; ESI-MS, electrospray ionization mass spectrometry; NEAT, NEAr iron Transporter; rIsdA, recombinant IsdA.

M. T. Tiedemann, N. Muryoi, D. E. Heinrichs, and M. J. Stillman (2008), submitted manuscript.

References

- 1.Gordon, R. J., and Lowy, F. D. (2008) Clin. Infect. Dis. 46 Suppl. 5, S350–S359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGowan, J. E., Jr., and Tenover, F. C. (2004) Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2 251–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Genco, C. A., and Dixon, D. W. (2001) Mol. Microbiol. 39 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wandersman, C., and Stojiljkovic, I. (2000) Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3 215–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skaar, E. P., and Schneewind, O. (2004) Microbes Infect 6 390–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wandersman, C., and Delepelaire, P. (2004) Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 58 611–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mazmanian, S. K., Ton-That, H., Su, K., and Schneewind, O. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99 2293–2298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrissey, J. A., Cockayne, A., Hammacott, J., Bishop, K., Denman-Johnson, A., Hill, P. J., and Williams, P. (2002) Infect. Immun. 70 2399–2407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor, J. M., and Heinrichs, D. E. (2002) Mol. Microbiol. 43 1603–1614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazmanian, S. K., Skaar, E. P., Gaspar, A. H., Humayun, M., Gornicki, P., Jelenska, J., Joachmiak, A., Missiakas, D. M., and Schneewind, O. (2003) Science 299 906–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reniere, M. L., Torres, V. J., and Skaar, E. P. (2007) Biometals 20 333–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skaar, E. P., Gaspar, A. H., and Schneewind, O. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 436–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarke, S. R., and Foster, S. J. (2008) Infect. Immun. 76 1518–1526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clarke, S. R., Mohamed, R., Bian, L., Routh, A. F., Kokai-Kun, J. F., Mond, J. J., Tarkowski, A., and Foster, S. J. (2007) Cell Host Microbe 1 199–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clarke, S. R., Wiltshire, M. D., and Foster, S. J. (2004) Mol. Microbiol. 51 1509–1519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vermeiren, C. L., Pluym, M., Mack, J., Heinrichs, D. E., and Stillman, M. J. (2006) Biochemistry 45 12867–12875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grigg, J. C., Vermeiren, C. L., Heinrichs, D. E., and Murphy, M. E. (2007) Mol. Microbiol. 63 139–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torres, V. J., Pishchany, G., Humayun, M., Schneewind, O., and Skaar, E. P. (2006) J. Bacteriol. 188 8421–8429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dryla, A., Gelbmann, D., von Gabain, A., and Nagy, E. (2003) Mol. Microbiol. 49 37–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mack, J., Vermeiren, C., Heinrichs, D. E., and Stillman, M. J. (2004) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 320 781–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharp, K. H., Schneider, S., Cockayne, A., and Paoli, M. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 10625–10631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grigg, J. C., Vermeiren, C. L., Heinrichs, D. E., and Murphy, M. E. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 28815–28822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pluym, M., Vermeiren, C. L., Mack, J., Heinrichs, D. E., and Stillman, M. J. (2007) J. Porph. Phthal. 11 165–171 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu, M., Tanaka, W. N., Zhu, H., Xie, G., Dooley, D. M., and Lei, B. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 6668–6676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheek, J., and Dawson, J. H. (2000) in Magnetic Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy of Heme Iron Systems, The Handbook of Porphyrins and Related Macrocycles, (Kadish, K. M., Smith, K. M., and Guilard, R., eds) Academic Press, New York

- 26.Eakanunkul, S., Lukat-Rodgers, G. S., Sumithran, S., Ghosh, A., Rodgers, K. R., Dawson, J. H., and Wilks, A. (2005) Biochemistry 44 13179–13191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pluym, M., Muryoi, N., Heinrichs, D. E., and Stillman, M. J. (2008) J. Inorg. Biochem. 102 480–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pluym, M., Vermeiren, C. L., Mack, J., Heinrichs, D. E., and Stillman, M. J. (2007) Biochemistry 46 12777–12787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Springall, J., Stillman, M. J., and Thomson, A. J. (1976) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 453 494–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu, H., Xie, G., Liu, M., Olson, J. S., Fabian, M., Dooley, D. M., and Lei, B. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 18450–18460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guzman, L.-M., Belin, D., Carson, M. J., and Beckwith, J. (1995) J. Bacteriol. 177 4121–4130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li, J. M., Umanoff, H., Proenca, R., Russell, C. S., and Cosloy, S. D. (1988) J. Bacteriol. 170 1021–1025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berry, E. A., and Trumpower, B. L. (1987) Anal. Biochem. 161 1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dryla, A., Hoffmann, B., Gelbmann, D., Giefing, C., Hanner, M., Meinke, A., Anderson, A. S., Koppensteiner, W., Konrat, R., von Gabain, A., and Nagy, E. (2007) J. Bacteriol. 189 254–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]