Abstract

To elucidate the heme acquisition system in pathogenic bacteria, we investigated the heme-binding properties of the third NEAT domain of IsdH (IsdH-NEAT3), a receptor for heme located on the surfaces of pathogenic bacterial cells, by using x-ray crystallography, isothermal titration calorimetry, examination of absorbance spectra, mutation analysis, size-exclusion chromatography, and analytical ultracentrifugation. We found the following: 1) IsdH-NEAT3 can bind with multiple heme molecules by two modes; 2) heme was bound at the surface of IsdH-NEAT3; 3) candidate residues proposed from the crystal structure were not essential for binding with heme; and 4) IsdH-NEAT3 was associated into a multimeric heme complex by the addition of excess heme. From these observations, we propose a heme-binding mechanism for IsdH-NEAT3 that involves multimerization and discuss the biological importance of this mechanism.

Iron is required for an enormous variety of metabolic processes in virtually all organisms. Pathogenic bacteria, including staphylococci, require iron to survive and establish their infections in host organisms, but despite its abundance worldwide, iron is limited in availability because of its insolubility under physiological conditions. Most bacterial pathogens have evolved strategies for acquiring iron from host proteins (1). The best-studied bacterial iron acquisition system is siderophore-based (2). Siderophores are low molecular weight iron-binding molecules that are secreted from bacterial cells for iron retrieval. However, Staphylococcus aureus, which is a major cause of hospital- and community-acquired infections, has evolved a different, sophisticated iron uptake mechanism, namely the iron-regulated surface determinant (Isd)3 system (1, 3, 4).

The Isd system uses heme as an iron source; heme contains more than 80% of the total iron in the human body (1, 3-5). Heme is supplied by the release of hemoglobin from erythrocytes into the blood by the action of bacterial cytotoxins α- and γ-hemolysin (6). The Isd system consists of nine proteins as follows: IsdA, IsdB, IsdC, IsdD, IsdE, IsdF, IsdG, IsdH, and IsdI. IsdA, IsdB, IsdC, and IsdH attach to the cell wall covalently by the action of sortase (1, 4, 7). Heme is captured by IsdB or IsdH and subsequently transferred to IsdA first and then to IsdC. IsdC transfers heme to the IsdD-IsdE-IsdF complex, a heme transporter located in the plasma membrane. Heme transported into the cytoplasm is degraded by the monooxygenases IsdG and IsdI (1, 4, 8).

All of the receptors of the Isd system (i.e. IsdA, IsdB, IsdC, and IsdH) contain one or more copies of the NEAr iron transporter (NEAT) domains (supplemental Fig. S1) (9). On the basis of their amino acid sequences, NEAT domains are categorized into four groups (10). Type I includes the first domain of IsdH (IsdH-NEAT1), IsdH-NEAT2, and IsdB-NEAT1. Type II domains are IsdH-NEAT3 and IsdB-NEAT2, and types III and IV include IsdC-NEAT and IsdA-NEAT, respectively. Thus far, the three-dimensional structures of the NEAT domains of type I, type III, and type IV have been reported, and those of type III and type IV have also been resolved in complex with heme (10-12). The type I NEAT domain (IsdH-NEAT1) does not bind heme, but it binds hemoglobin and the hemoglobin-haptoglobin complex (13, 14). Neither the three-dimensional structure nor the molecular properties of type II NEAT domains have yet been reported. Interestingly, proteins containing NEAT domains are potent candidates for Staphylococcus aureus vaccines (15, 16).

S. aureus has an extraordinary feature: it readily becomes resistant to antibiotics. Indeed, strains of this organism have acquired resistance to almost all known antibiotics, thus increasing the incidence of acute hospital-acquired infections (17). A novel drug or other strategy is needed to overcome the threat of S. aureus, and there is an urgent need to develop vaccines that utilize all the surface components of this bacterium. In addition, NEAT domains have also been identified in other pathogenic Gram-positive bacteria, including Clostridium perfringens and Listeria monocytogenes (9). Therefore, from a molecular pathogenetic viewpoint, studies focused on NEAT domains are expected to yield key benefits for human health.

Here we report the crystal structure and heme-binding properties of IsdH-NEAT3, a type II domain. Heme was bound at the surface of IsdH-NEAT3, as found in other NEAT domains for which the structures in complex with heme have been reported (11, 12). Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) and spectrometric analysis showed that IsdH-NEAT3 can bind to multiple heme molecules. Mutational analysis showed that residues located around the heme-binding pocket were not essential for binding heme in IsdH-NEAT3, even if they were directly coordinated with the heme. Spectroscopic analysis indicated two ways of heme binding in IsdH-NEAT3, and size-exclusion chromatography and analytical ultracentrifugation revealed that IsdH-NEAT3 associated to form multimeric heme complexes through specific interactions with heme molecules. Together, these observations and our knowledge of the stacked structure of heme in crystalline form enabled us to propose a mechanism for heme binding by IsdH-NEAT3. We also discuss the importance of these heme-binding properties in vivo.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Construction of Expression Vectors for IsdH-NEAT1, IsdH-NEAT2, and IsdH-NEAT3—The genes encoding the NEAT1 (corresponding to the region from Asn-101 to Ala-232), NEAT2 (Asp-341 to Asp-471), and NEAT3 (Pro-539 to Gln-664) domains of IsdH were amplified by PCR using KOD-Plus DNA polymerase (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) and S. aureus Mu50 genomic DNA as a template (supplemental Fig. S1). The PCR product was inserted into the NcoI and XhoI sites of a pET28b-based Escherichia coli expression vector. All expression vectors for site-specifically altered variant proteins were prepared by using a KOD-Plus mutagenesis kit (Toyobo) and synthesized primers. DNA sequences were confirmed with an ABI 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Expression and Purification of IsdH-NEAT1, IsdH-NEAT2, IsdH-NEAT3, and Variant Proteins—IsdH-NEAT1, -2, and -3, variant proteins of IsdH-NEAT3, and selenomethionine-substituted IsdH-NEAT3 were expressed by E. coli in M9 medium, as described elsewhere (18). Cells were disrupted with a sonicator (Tomy, Tokyo, Japan), and the soluble fraction was loaded onto a HisTrap column (GE Healthcare). The adsorbed protein was eluted with a 0-0.5 m gradient of imidazole. Fractions containing IsdH-NEAT3 were dialyzed against 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 200 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2 and then incubated for 24 h at 4 °C with thrombin, which was added at a concentration of 1 unit mg protein-1 to cleave the His tag attached at the N terminus. The cleaved His tag was removed by the His-trap column, and the sample was further purified on a HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 75-pg column (GE Healthcare). Fractions containing the desired protein were collected and used for further experiments.

For the heme-binding assay, proteins were purified by His-Bind resin (Merck) charged with Ni2SO4. Purified proteins were dialyzed against 50 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.3) and then used in assays.

Determination of Protein Concentration—Protein concentrations were measured by absorption at a wavelength of 280 nm with a molar extinction coefficient of 13,900 m-1, as determined from the amino acid sequences. All the molar concentrations of IsdH-NEAT3 described in this study represent the concentrations as monomeric protein, and the molar ratios of heme against protein also represent those with respect to monomeric protein.

Absorption Spectra Measurements of IsdH-NEAT1, IsdH-NEAT2, and IsdH-NEAT3 Expressed in Medium Containing Biosynthetic Ingredients of Heme—To form heme complex in E. coli cells, IsdH-NEAT1, IsdH-NEAT2, and IsdH-NEAT3 were expressed in M9 medium containing 0.5 mm 5-aminolevulinic acid and 0.5 mm FeSO4, which are biosynthetic ingredients of heme. This method is widely used to prepare protein-heme complex in E. coli (19). Expressed proteins were purified by His-trap column, followed by dialysis against 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 200 mm NaCl. The absorption spectra of the purified proteins were measured on a spectrophotometer (U-2800, Hitachi, Hitachi, Japan) in a quartz cell with an optical path length of 10 mm.

Crystallization of IsdH-NEAT3 and IsdH-NEAT3 Complexed with Heme—Purified IsdH-NEAT3 was dialyzed against 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and then concentrated to 20 mg ml-1. Crystals of the apo-form of IsdH-NEAT3 were grown by the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method from 100 mm acetate (pH 4.2), 1.7 m ammonium sulfate. Crystals of the heme-bound form of IsdH-NEAT3 were prepared in 100 mm CAPS (pH 10.5), 20% polyethylene glycol 8000, 200 mm NaCl by using a mixed solution of purified IsdH-NEAT3 and heme at a molar ratio of 1:1.2.

X-ray Diffraction—X-ray diffraction of selenomethionine-substituted IsdH-NEAT3 was performed on the beamline BL5A at the Photon Factory (National Laboratory for High Energy Physics, Tsukuba, Japan). For multiple-wavelength anomalous diffraction (MAD) phasing, wavelengths of 0.97945, 0.97955, and 0.96432 Å were chosen on the basis of the fluorescence spectrum of the selenium K absorption edge. For refinement, diffraction of native IsdH-NEAT3 to a resolution of 2.2 Å was also collected on the beamline BL6A. Diffraction data on the IsdH-NEAT3-heme complex were collected on the beamline NW12 at the Photon Factory. All of the diffraction data were indexed, integrated, scaled, and merged by using the HKL2000 program package (20). The data collection and processing statistics are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

X-ray data collection and refinement statistics

|

Data collection

|

Selenomethionine-substituted structure (MAD)

|

Native

|

Heme complex

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak | Edge | Remote | |||

| Space group | R32 | R32 | P21212 | ||

| Cell dimensions | a = b = 123.94 c = 120.89 | a = b = 124.25 c = 119.66 | a = 49.22 b = 75.69 c = 39.27 | ||

| Beamline | Photon Factory BL5A | Photon Factory BL6A | Photon Factory NW12 | ||

| Resolution (Å)a | 50 to 2.54 (2.63 to 2.54) | 50 to 2.54 (2.63 to 2.54) | 50 to 2.20 (2.28 to 2.20) | 50 to 1.90 (1.97 to 1.90) | |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.97945 | 0.97955 | 0.96432 | 1.00000 | 1.00000 |

| Rsym (%)ab | 8.7 (35.9) | 7.8 (37.1) | 7.6 (36.5) | 4.2 (34.3) | 6.9 (28.5) |

| Completeness (%)a | 99.7 (97.4) | 99.7 (97.6) | 99.5 (96.2) | 99.9 (100) | 98.6 (90.5) |

| Observed reflections | 127,235 | 127,343 | 127,086 | 201,338 | 81,557 |

| Unique reflections | 11,904 | 11,921 | 11,917 | 18,212 | 11,976 |

| Multiplicitya | 10.7 (8.3) | 10.7 (8.3) | 10.7 (8.2) | 11.1 (10.6) | 6.8 (5.9) |

| Refinement and model quality | |||||

| Resolution range (Å) | 19.25 to 2.20 | 17.62 to 1.90 | |||

| No. of reflections | 18,159 | 10,756 | |||

| R-factorc | 0.240 | 0.193 | |||

| Rfree-factord | 0.265 | 0.242 | |||

| Total protein atoms | 1848 | 908 | |||

| Total ligand atoms | 19 | 43 | |||

| Total water atoms | 105 | 88 | |||

| Solvent content (%) | 58.9 | 50.7 | |||

| Average B-factor (Å2) | 41.5 | 20.5 | |||

| Root mean square deviation from ideality | |||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.006 | 0.016 | |||

| Bond angles (°) | 1.30 | 1.75 | |||

| Ramachandran plot | |||||

| Residues in most favored regions (%) | 87.4 | 90.1 | |||

| Residues in additional allowed regions (%) | 12.6 | 9.9 | |||

Values in parentheses refer to data in the highest resolution shell.

Rsym = ∑h ∑i|Ih,i - <Ih>|/∑h∑i |Ih,i|, where <Ih> is the mean intensity of a set of equivalent reflections.

R-factor = ∑|Fobs - Fcalc|/∑ Fobs, where Fobs and Fcalc are observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes, respectively.

Rfree-factor was calculated for R-factor, with a random 10% subset from all reflections.

Structure Solution and Refinement—Initial phasing was achieved by the MAD method with the program SOLVE (21). Subsequent phase improvement was performed with the programs SOLVE and RESOLVE (21-25). Additional model building, positional energy minimization, and individual B-factor refinements were carried out automatically on the native diffraction data by using the program LAFIRE (26). After automatic refinement and model fitting by LAFIRE, several cycles of refinement with the program CNS (27) and manual model fitting were performed, and then the water molecules were placed automatically. The crystallographic R and Rfree values for IsdH-NEAT3 converged to 26.5 and 24.0%, respectively.

The structure of the IsdH-NEAT3-heme complex was determined by the molecular replacement method with the program MOLREP (28), by using the structure of apoIsdH-NEAT3 as a search probe. After several cycles of refinement with the program REFMAC5 (29) and manual model fitting, an obvious electron density derived from heme was observed (supplemental Fig. S2), and the heme molecule could be placed. Finally, the water molecules were picked automatically. The crystallographic R and Rfree values for the IsdH-NEAT3-heme complex converged to 19.3 and 24.2%, respectively.

The stereochemical qualities of the final refined models were analyzed with the program PROCHECK (30). The refinement statistics are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

ITC measurements for IsdH-NEAT3 and its variant proteins

|

Variant

|

Stoichiometry

|

Ka

|

ΔH

|

ΔS

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1/N | ||||

| ×106m−1 | kcal mol−1 | cal mol−1 K−1 | |||

| Wild type | 0.229 | 4.4 | 3.22 | −66.3 | −193 |

| M565A | 0.367 | 2.7 | 0.47 | −53.7 | −154 |

| Y593A | 0.389 | 2.6 | 2.31 | −33.0 | −81.7 |

| Y642A | 0.403 | 2.5 | 0.83 | −18.4 | −34.5 |

| Y646A | 0.275 | 3.6 | 1.47 | −30.5 | −74.1 |

| Y642A/Y646A | 0.387 | 2.6 | 0.59 | −16.9 | −30.3 |

Determination of Heme Binding to IsdH-NEAT3—Hemin (Sigma) was dissolved in 0.1 m NaOH, and its concentration was determined by pyridine hemochrome assay (31). A solution of 400 μm hemin was prepared by dilution with 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.3). Hemin solution was added to 1 ml of 0.25 mg/ml IsdH-NEAT3 (which corresponds 20 μm of monomeric IsdH-NEAT3) in 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.3) at various concentrations. After incubation of the mixture at room temperature for 5 min, NaCl was added to increase the concentration of NaCl to 1 m. The absorbance of the solution was measured in the wavelength range of 240-800 nm. Each reaction mixture was loaded onto a DEAE-Sepharose Superflow column (GE Healthcare) previously equilibrated with 50 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.3), 1 m NaCl. The fraction that passed through the column (pass-through fraction) was collected, and then the absorbance spectrum between 240 and 800 nm was obtained for the unbound fraction.

ITC—All ITC measurements were carried out with a VP-ITC System (MicroCal, Northampton, MA). Proteins were dialyzed against 50 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.3) containing 5% DMSO and then adjusted to 1.26 mg/ml (100 μm of monomer IsdH-NEAT3) by dilution with the same buffer. Working solutions of hemin were prepared by diluting a stock solution, which was prepared by dissolving hemin in 0.1 m NaOH with 50 mm phosphate (pH 7.3) containing 5% DMSO (to prevent aggregation of heme). The cell was filled with 50 μm hemin solution, and a syringe was filled with IsdH-NEAT3 or its variant protein. The protein solution was injected 25 times in portions of 10 μl over 20 s. The data obtained were analyzed with the program ORIGIN (MicroCal, Northampton, MA).

Size-exclusion Chromatography (SEC)—SEC using a HiLoad Superdex 75 column (16 × 600 mm; GE Healthcare) was carried out to analyze changes in the molecular mass of IsdH-NEAT3 after the addition of heme. The column was equilibrated with 50 mm sodium phosphate (pH 8.0) containing 1 m NaCl, and then 2 ml of prepared protein was applied to the column at a flow rate of 0.5 ml min-1.

Analytical Ultracentrifugation—The multimeric fraction from

the final step of SEC purification was used for analytical

ultracentrifugation. Sedimentation velocity experiments were performed in an

Optima XL-I analytical ultracentrifuge (Beckman-Coulter), using an eight-hole

An-50Ti rotor at a rotor speed of 40,000 rpm at 20 °C. Moving boundaries

were recorded at a wavelength of 390 nm without time intervals between

successive scans. The sedimentation coefficient distribution function

c(s) was obtained by using the SEDFIT program

(32-33).

The molecular mass distribution c(M) was obtained by

converting c(s) on the assumption that the frictional ratio

f/f0 was common to all the molecular species as

implemented in SEDFIT. The protein partial specific volume

( ) was calculated from the amino acid

sequence, and the buffer density (ρ) and viscosity (η) were calculated

according to the solvent composition using the program SEDNTERP

(34).

) was calculated from the amino acid

sequence, and the buffer density (ρ) and viscosity (η) were calculated

according to the solvent composition using the program SEDNTERP

(34).

CD Spectroscopy—Proteins were dialyzed against 10 mm sodium phosphate (pH 8.0), 200 mm NaCl with or without 5% DMSO, after which the CD spectra were measured on a spectropolarimeter (model J-725, Jasco, Tokyo, Japan) in a quartz cell with an optical path length of 10 mm. CD spectra were obtained by taking the average of four scans made from 350 to 190 nm.

RESULTS

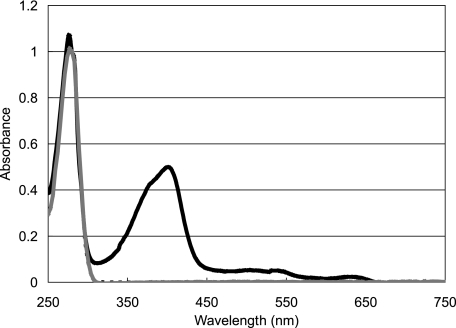

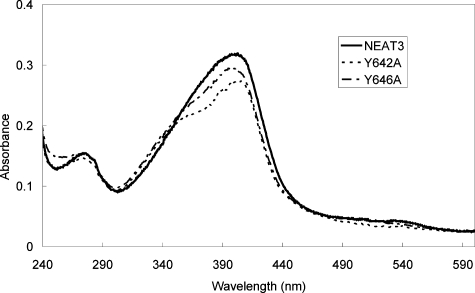

Heme-binding Properties of IsdH-NEAT3—IsdH from S. aureus has three NEAT domains: IsdH-NEAT1 (amino acids 101-232), IsdH-NEAT2 (amino acids 341-471), and IsdH-NEAT3 (amino acids 539-664). We examined the UV spectra of these NEAT domains in IsdH produced by E. coli culture in a medium containing 5-aminolevulinic acid and FeSO4 (Fig. 1); this medium is widely used for preparing protein-heme complex in E. coli (19). Among the three domains, only IsdH-NEAT3 exhibited absorption at ∼400 nm, suggesting that only IsdH-NEAT3 could bind a heme. No interaction between IsdH-NEAT3 and hemoglobin or haptoglobin was observed by surface plasmon resonance and ITC (data not shown). These results suggest that IsdH-NEAT3 has a function distinct from those of IsdH-NEAT1 and IsdH-NEAT2 in vivo.

FIGURE 1.

Absorbance spectra of IsdH-NEAT1 (dashed line), IsdH-NEAT2 (gray line), and IsdH-NEAT3 (solid line).

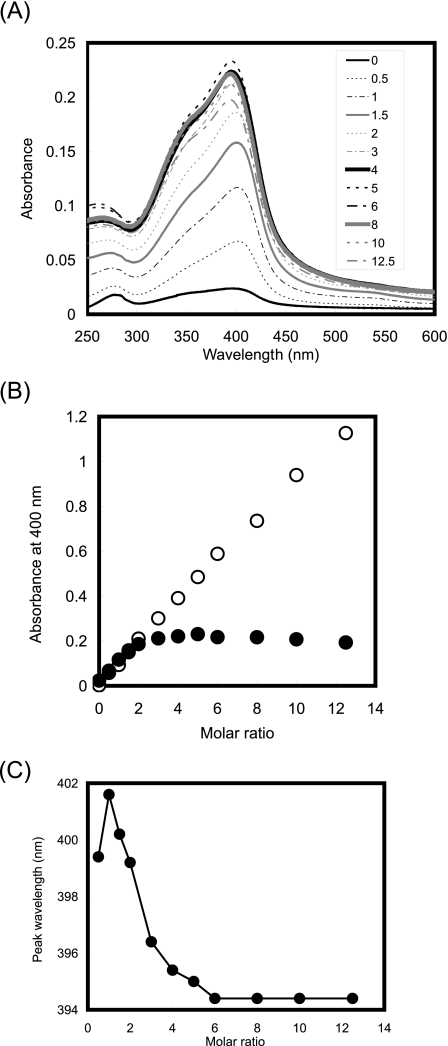

We then assessed the heme-binding properties of IsdH-NEAT3 on the basis of the absorbance spectrum in the visible region. Heme is strongly adsorbed to many kinds of column resins, and neither alkali nor acid can elute the heme molecules from our column once they have been captured (data not shown). However, we confirmed that heme molecules bound to IsdH-NEAT3 could be easily eluted from an anion-exchange column by the addition of NaCl at high concentrations. Under these conditions, the protein was not eluted. Therefore, we quantified the binding of heme molecules to IsdH-NEAT3 by examining the visible absorbance spectra of the fractions that were eluted from an anion-exchange column by 1 m NaCl (Fig. 2A). Absorbance increased with the molar ratio of heme to protein, and absorbance continued to increase even at molar ratios exceeding 1:1. We then plotted the absorbance at a wavelength of 400 nm against the molar ratio of heme to IsdH-NEAT3 in the mixture before application to the column and in the flow-through fraction (Fig. 2B). The absorbance of the mixture at 400 nm before application increased linearly to a stoichiometry of 12.5:1. In contrast, the absorbance of the flow-through fraction reached saturation at a stoichiometry of around 4:1. These results show that a single IsdH-NEAT3 domain can bind several heme molecules and that heme molecules that do not bind to IsdH-NEAT3 are trapped by the column (at ratios exceeding 4:1). In the negative controls, to which none of the proteins was added or lysozyme was added instead of IsdH-NEAT3, the absorbance at 400 nm of the unbound fraction did not increase, even if heme was present in a molar ratio of 20:1 (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

Heme-binding properties of IsdH-NEAT3. A, absorbance spectra of unbound fraction of DEAE column. The molar ratios of heme added to IsdH-NEAT3 were as follows: 0 (solid thin black line), 0.5 (dotted thin black line), 1 (dotted and dashed thin black line), 1.5 (solid thin gray line), 2 (dotted thin gray line), 3 (dotted and dashed thin gray line), 4 (solid thick black line), 6 (dotted thick black line), 8 (dotted and dashed thick black line), 10 (solid thick gray line), and 12.5 (dashed thick gray line). B, change in absorbance at 400 nm wavelength with increasing molar ratio of heme added to IsdH-NEAT3. Open circles, absorbance before addition to the column; solid circles, absorbance of flow-through fraction. C, change in peak wavelength with increasing molar ratio of heme added to IsdH-NEAT3.

Interestingly, a gradual increase in prominence of the peak at around 350 nm occurred at heme to IsdH-NEAT3 molar ratios above 1.5:1 (Fig. 2A), and the peak wavelength of the spectrum changed with the increase in the molar ratio of heme to IsdH-NEAT3 (Fig. 2C). When the molar ratio was lower than 2:1, the peak appeared at around 400 nm. However, further addition of heme caused a gradual blue shift of the peak, resulting in a peak at 394.4 nm in the spectrum when the molar ratio was 6:1 or greater. This change in the Soret band indicates a change in the environment around the bound hemes. Perhaps two modes of heme binding are present, one that yields the Soret band at around 400 nm and another that gives a shoulder on the spectrum at around 350 nm and the blue shift.

We used ITC to investigate the interaction kinetics between heme and IsdH-NEAT3 (Table 2 and supplemental Fig. S3). The result was a typical sigmoidal curve that fitted a theoretical curve with an association constant (Ka) of 3.22 × 106 m-1. Interestingly, the N value, which reflects the reaction stoichiometry, was calculated as 0.229, indicating that each molecule of IsdH-NEAT3 bound about four molecules of heme despite the addition of 5% DMSO to prevent aggregation. This observation agrees well with the heme-binding properties of IsdH-NEAT3 described earlier (i.e. the absorbance at 400 nm increased up to a heme to IsdH-NEAT3 molar ratio of 4:1; see Fig. 2B).

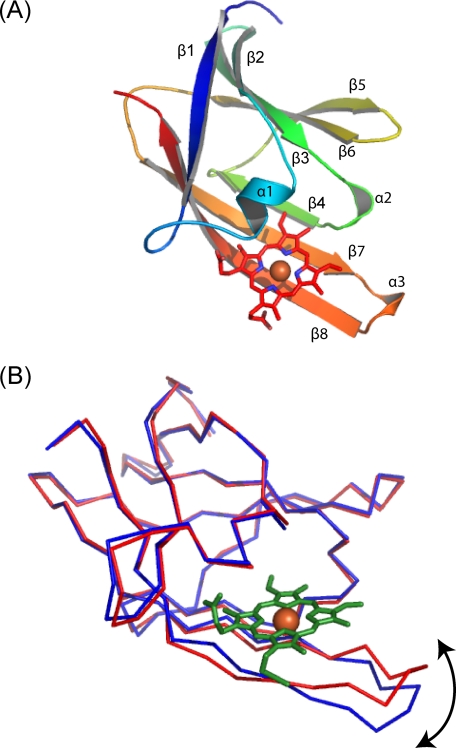

Crystal Structure of IsdH-NEAT3 and IsdH-NEAT3 in Complex with Heme—The crystal structure of IsdH-NEAT3 was determined at a resolution of 2.2 Å by use of the MAD method (Table 1). IsdH-NEAT3 was composed of three short helices (α1-α3) and eight β-strands (β1-β8), which formed a β-sandwich composed of two antiparallel β-sheets, as occurs in other NEAT domains for which the structures have been reported (Fig. 3A). Two molecules of IsdH-NEAT3 were arranged in an asymmetric unit. The root mean square difference between these two molecules was 0.48 Å. The three-dimensional structures of three other NEAT domains, i.e. IsdH-NEAT1 (sequence identity with IsdH-NEAT3, 13.5%), IsdA-NEAT (sequence identity, 19.0%), and IsdC-NEAT (sequence identity, 15.1%), have been reported (10-12). The structures of heme-complexed IsdA-NEAT and IsdC-NEAT have been elucidated (11, 12). The overall structure of IsdH-NEAT3 was superimposed well on those of the other NEAT domains; the root mean square difference for IsdH-NEAT1, IsdA-NEAT, and IsdC-NEAT was 2.01, 1.46, and 1.82 Å, respectively. Our determination of the structure of IsdH-NEAT3 completes the elucidation of the structures of all four types of NEAT domain, as categorized by sequence identity.

FIGURE 3.

Crystal structure of IsdH-NEAT3 in complex with heme. A, ribbon diagram of IsdH-NEAT3 in complex with heme. The ribbon model is colored according to the sequence from blue at the N terminus to red at the C terminus. Bound heme molecule is shown as a stick model. B, superposition of the C-α trace of IsdH-NEAT3 without heme (blue) and IsdH-NEAT3 complexed with heme (red). Heme (green sticks) and heme iron (orange ball) are also shown.

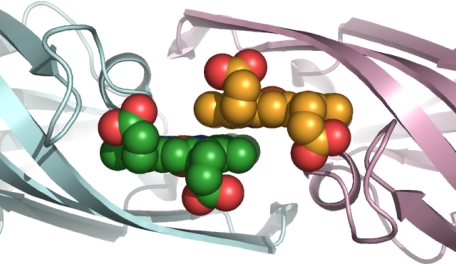

Next, we used the molecular replacement method to determine the crystal structure of IsdH-NEAT3 in complex with heme at a resolution of 1.9 Å, with apo-IsdH-NEAT3 as a search model. One molecule of IsdH-NEAT3 was located in an asymmetric unit and captured one heme molecule. As is the case for IsdA-NEAT-heme and IsdC-NEAT-heme, heme was bound at the surface of IsdH-NEAT3 in an area composed of α1, β4, β7, and β8 (Fig. 3A). Approximately 340 Å2 (44%) of the surface of the bound heme was exposed to solvent.

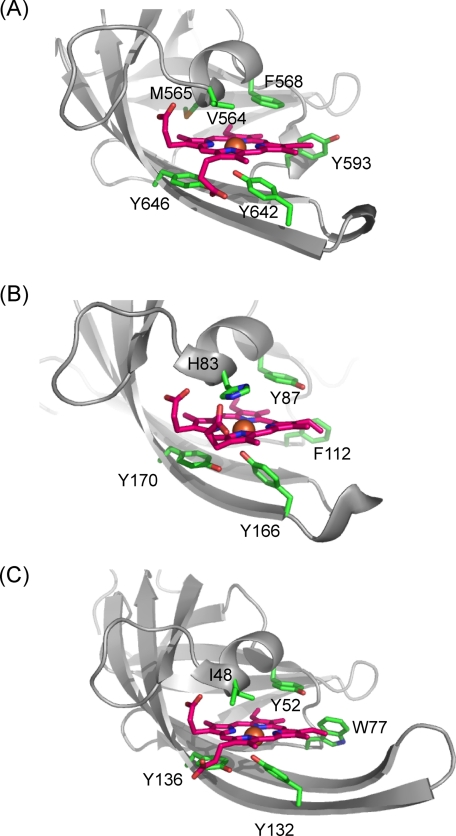

Structural rearrangement occurred around the heme-binding region (Fig. 3B), although similar structural change does not occur in IsdA-NEAT (11). A hairpin-like structure composed of β7-β8 migrated to the bound heme to close the heme-binding pocket, thus leading to tight binding of the heme to IsdH-NEAT3. Marked conformational changes in Tyr-593 and Met-565 also occurred, by which the side chains of these residues shifted to accommodate heme binding. The heme-binding site included the residues Ser-563, Val-564, Met-565, Phe-568, Tyr-593, Trp-594, Val-635, Val-637, Ile-640, Tyr-642, Tyr-646, and Val-648, indicating that the site was in a hydrophobic environment. A hydroxyl group of Tyr-642 coordinated iron at a distance of 2.21 Å, resulting in a five-coordinate conformation (Fig. 4A). Ser-563 and Tyr-646 formed hydrogen bonds with the oxygen atoms of propionates in heme. Structural comparison of the heme-binding site in IsdH-NEAT3 with those in other NEAT domain-heme complexes showed that they have similar coordination geometries for binding heme (Fig. 4), whereby the hydroxyl group of a Tyr residue (Tyr-642 in the case of IsdH-NEAT3) coordinates the iron in the heme. In addition, the Tyr that is four residues later than that coordinating iron (Tyr-646 in the case of IsdH-NEAT3) was located beside the heme and was coplanar with one of the pyrroles, forming a hydrogen bond with Tyr coordinating the iron by using a hydroxyl group on the side chain (Fig. 4). In contrast to this structural similarity, IsdH-NEAT3 showed no conserved residues around the bound heme, with the exception of the two tyrosines just described. In the case of the NEAT domain of IsdC, Trp-77 has been proposed as the residue responsible for heme binding; the corresponding residue in IsdH-NEAT3 is Tyr-593 (12).

FIGURE 4.

Comparison of residues around heme. A, IsdH-NEAT3. B, IsdA-NEAT (Protein Data Bank code 2ITF). C, IsdC-NEAT (Protein Data Bank code 2O6P). The bound heme molecules are shown as sticks, with pink carbons; the heme irons appear as orange balls. Residues coordinating heme iron and located around the heme are also shown as sticks; their carbons are shown as green.

Effects of Mutations on Affinity for Heme—Analysis of the crystal structure revealed the manner by which IsdH-NEAT3 bound to heme, i.e. by hydrophobic interaction with, and direct coordination of the heme iron by, Tyr-642. To gain insight into the residues responsible for the heme-binding mechanism, we used ITC to evaluate the heme-binding properties of five variant proteins, M565A, Y593A, Y642A, Y646A, and Y642A/Y646A. Tyr-593 corresponded to a residue proposed to be essential for heme binding in IsdC-NEAT (12). Met-565 was the only sulfur-containing residue located around the heme-binding pocket and is conserved in IsdA-NEAT. Examination of the CD spectra of these variant proteins indicated that no major conformational changes were induced as a result of the substitutions (data not shown). Table 2 shows the thermodynamic parameters of the interactions between these variant proteins and heme molecules. The affinity of each variant protein was reduced markedly. Interestingly, despite their reduced stoichiometric ratios, all variant proteins could bind a few molecules of heme, as was the case for the wild type. In addition, the thermodynamic parameters of heme binding changed dramatically with the Y642A and Y642A/Y646A mutations. In the Y642A variant, for instance, the negative enthalpy change was decreased by ∼40 kcal mol-1 and the negative entropy change was decreased by ∼160 cal mol-1 K-1, resulting in an ∼400% decreased affinity for heme compared with that of IsdH-NEAT3. Although substitution of Tyr-642 and Tyr-646 altered the heme-binding properties of IsdH-NEAT3, Y642A/Y646A still possessed some affinity for heme. These results were also confirmed by the increasing absorbance spectrum of the unbound fraction of all variant proteins in an anion-exchange chromatography column (data not shown).

Absorption Spectra of Heme Bound to Y642A and Y646A Variants—To elucidate the environment surrounding the bound heme molecule, the absorption spectra of the Y642A and Y646A variants in complex with heme were measured and compared with that of the wild type (Fig. 5). The absorption spectra of the variants were obviously distinct from that of the wild type; in the variants a shoulder appeared at around 350 nm. These results indicate that mutation at Tyr-642 or Tyr-646 markedly altered the environment around the bound heme and that Tyr-642 and Tyr-646 strongly influenced heme binding. The spectral change because of substitution of Tyr-646, which was directly coordinated to the iron of the heme, was more apparent than that from Y642A, suggesting that the spectral change was because of a change in the coordination structure by Tyr-646. These results confirmed that heme was bound at the binding site revealed in the crystal structure, even in solution.

FIGURE 5.

Absorbance spectra of wild-type IsdH-NEAT3, Y642A variant, and Y646A in complex with heme.

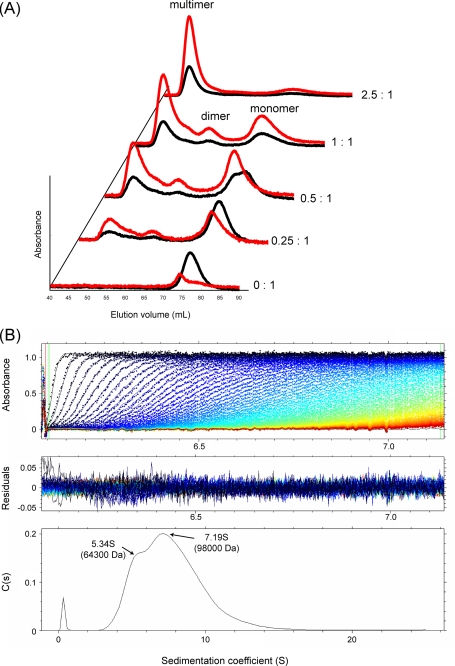

Multimerization of IsdH-NEAT3 by Addition of Heme—The ITC and spectrometric results described showed that each molecule of IsdH-NEAT3 could bind several heme molecules. To check whether there was any association of the protein upon addition of the heme, we used SEC to examine the association states of IsdH-NEAT3 in the presence of heme at a number of heme to protein ratios (Fig. 6A). In the absence of heme, IsdH-NEAT3 existed, as expected, as a monomer, with a molecular mass of 16 kDa, as estimated by the elution volume relative to those of molecular markers. In the presence of heme at a heme to protein molar ratio of 0.25:1, two additional peaks were observed in the chromatogram, associated with the expected increase in absorbance at the monomer peak at 400 nm. The monomer peaks measured at 280 and 400 nm did not coincide, and the latter was eluted earlier than the latter. We calculated the molecular masses of the three peaks as 15, 44, and >75 kDa, indicating dimerization and multimerization of the protein by the addition of heme molecules. With the addition of heme at 0.5:1, the monomer peak was split into two peaks showing absorbance at 280 nm, and only the earlier eluting peak had absorbance at 400 nm (Fig. 6A).

FIGURE 6.

Multimerization of IsdH-NEAT3 by addition of heme. A, size-exclusion chromatography of IsdH-NEAT3 to which increasing amounts of heme were added. Absorbances at wavelengths of 280 nm (black) and 400 nm (red) are shown for IsdH-NEAT3 and heme. Molar ratios of heme to IsdH-NEAT3 are shown at the right side of the chart. B, sedimentation velocity experiments were carried out on the multimeric fraction from size-exclusion chromatography, and the data were analyzed by SEDFIT. Upper, time development of the moving boundaries is superimposed with the calculated moving boundaries based on the obtained c(s). Middle, residuals of the raw data and the calculated theoretical curves. Lower, distribution of sedimentation coefficient, c(s). The molecular weights of the two peaks (arrows) with the sedimentation coefficients 5.34 S and 7.19 S, 64,300 and 98,000 Da, were obtained by converting c(s) to c(M). Note that the two peaks, especially the larger peak, may not precisely correspond to particular molecular species present in solution, where dynamic equilibrium is most likely present.

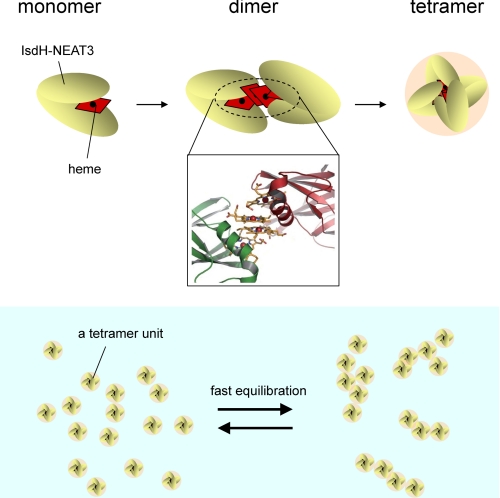

Further addition of heme brought about some increase in the multimer fraction and resulted in complete multimerization when a 2.5 times molar excess of heme was added. To characterize the multimerization that occurred upon addition of heme at a molar ratio of 2.5:1, sedimentation velocity experiments were performed, and the data were analyzed by SEDFIT (Fig. 6B). The obtained sedimentation coefficient distribution function, c(s), showed a broad distribution with two peaks at 5.34 S and 7.19 S, indicating that a number of multimeric states were in dynamic equilibrium. When c(s) was converted into c(M), the 5.34 S peak corresponded to 64.3 kDa. It is likely that the IsdH-NEAT3-heme complex associates into a tetramer and the tetramer complex further associates as a unit multimer. This is in agreement with electron microscopic observation that the aggregates of IsdH-NEAT3-heme complex are composed of 3-10 spherical particles with diameters of about 10 nm (data not shown). These results indicate that IsdH-NEAT3 binds heme as a monomer or dimer at low heme to protein ratios, but at higher molar ratios the protein undergoes multimerization to various degrees, which are in dynamic equilibrium.

DISCUSSION

Structural Implications of Multiple Heme Binding and Multimerization—Spectrometric analysis, ITC measurement, size-exclusion chromatography, and analytical ultracentrifugation showed that each IsdH-NEAT3 domain could bind several heme molecules and that the multiple binding of heme led to multimerization of the IsdH-NEAT3 complex. In the crystal, two crystallographically related hemes were located in parallel at a distance of 8.7 Å between the two heme irons, which appeared to interact with each other (Fig. 7). A number of similar observations have been reported. de Villiers et al. reported that hemes stack to form a dimer in aqueous solution (35). The malaria-causing pathogen Plasmodium detoxifies oxidative hemes by forming hemozoin, which is an insoluble material made of stacked heme molecules (36). In chlorosomes, which are the main antenna complexes of green photosynthetic bacteria, several tens of thousands of molecules of bacteriochlorophyll, one of the porphyrin derivatives similar to heme, are stacked and assembled into rod-like aggregates (37). Similarly to these multimerized porphyrin-derivative compounds, hemes might become stacked when they are captured by IsdH-NEAT3. The crystal structure of the streptococcal cell surface protein Shp, a distant member of the NEAT family, was reported recently (38). Shp-heme complex was able to be superposed on IsdH-NEAT3 in complex with heme with a root mean square difference of 2.38 Å for 92 C-α atoms, and heme was captured at the same position. Interestingly, in the Shp-heme complex, two additional stacked heme molecules were sandwiched between hemes captured by two Shp molecules facing each other (supplemental Fig. S4). IsdH-NEAT3 might also bind to exogenous heme molecules by stacking bound heme, thereby capturing four heme molecules by one IsdH-NEAT3 monomer. The environment around the heme that is directly bound to IsdH-NEAT3 and of the heme subsequently sandwiched should be distinctive. The spectral change in the Soret band with additional heme (i.e. the appearance of a shoulder at 350 nm and a blue shift in the peak) very likely corresponds to the change in the surrounding environment. Furthermore, the absorption at 370 nm increases as Shp acquires additional heme (38).

FIGURE 7.

Crystallographically related hemes. Heme molecules are represented as CPK space filling model. Protein molecules are shown as ribbon diagrams, which are colored blue or pink according to subunit.

In light of the spectrophotometric properties described and the multimerization by excess amounts of heme, we propose the following putative heme-binding model (Fig. 8). In our putative mechanism, heme is specifically captured in the heme-binding pocket of monomeric or dimeric IsdH-NEAT3 primarily by the arrangement observed in the crystal structure; this process yields a peak at around 400 nm. IsdH-NEAT3 captures additional heme molecules by stacking with bound heme, in a manner similar to that for Shp, by which a multimolecular complex of IsdH-NEAT3 is formed. This process yields a shoulder at 350 nm and a blue shift in the peak wavelength (Fig. 2A). Two peaks in the distribution of sedimentation coefficients, c(s), are not well separated, and the larger peak, 7.19S, has some trailing edge to higher s values, indicating a dynamic association-dissociation equilibrium between multimers. It is known that when multimeric states are in fast equilibrium as compared with the time of experiment, the peaks in c(s) may not represent the true s values of the existing molecular species. However, the combined information from c(s), c(M), and SEC (Fig. 6, A and B) is compatible with a model where the tetramer, a unit multimer, is in equilibrium with higher oligomers as well as low concentrations of dimer and monomer. This is consistent with our electron microscopic observation, which revealed some multimeric oligomers (data not shown). SEC analyses showed that the molecular mass of the Isd-NEAT3 monomer was 13.5 kDa, as estimated by the elution volume relative to those of molecular markers. On the other hand, the heme-complexed Isd-NEAT3 monomer was eluted slightly earlier (Fig. 6A) and had a molecular mass of 16.3 kDa. These results suggested that four heme molecules bound to one IsdH-NEAT3 monomer, because the molecular mass of heme is 617 Da, and four hemes correspond to the difference in molecular mass between the unliganded Isd-NEAT3 monomer and the liganded one. The fact that Isd-NEAT3 can bind several heme molecules may well reflect its function in vivo. Also note that a dissection of the interaction between IsdH-NEAT3 and free-base porphyrin or metalloporphyrin might provide some novel insight into protein-porphyrin interactions.

FIGURE 8.

Schematic representation of proposed mechanism of heme binding by IsdH-NEAT3. IsdH-NEAT3 and heme are shown as CPK space filling model and red stick model, respectively. The primary and secondary modes of heme binding described in the text are indicated.

Heme Binding Mechanism in IsdH-NEAT3—Although the affinity of all IsdH-NEAT3 variant proteins for heme was less than that in the wild type, the variants still retained a high affinity for heme (Ka ≥ 105 m-1) and the ability to bind multiple heme molecules, suggesting that the substituted residues were not essential for heme binding. The smallest Ka was 0.47 × 106 m-1, for the M565A variant (Table 2); nevertheless, Met-565 did not directly interact with heme. However, the thermodynamic parameters for the M565A variant were not markedly different from those of the wild type, suggesting that Met-565 does not contribute to heme binding directly but to the stability of the structure of the protein-heme complex.

In contrast, the thermodynamic parameters of the tyrosine-substituted variants changed markedly. Presumably, van der Waals interactions by these tyrosine residues surrounding the heme-binding pocket would strongly contribute to heme binding. Among them, substitution of Tyr-642 (i.e. in the Y642A and Y642/Y646A variants) markedly decreased the binding affinity and changed the thermodynamic parameters (i.e. there were considerable decreases in the absolute values of enthalpy and entropy). In the crystal structure, the hydroxyl group of Tyr-642 was coordinated to the iron of the heme. Furthermore, the spectrophotometric analysis of Y642A showed that, in solution, the heme bound to the proposed binding site, as in the crystal (Fig. 5). These results indicate that the proposed candidate residues that bound to the heme were not essential, although the contribution of Tyr-642 was the most important among them. Considering that Tyr-642 and Tyr-646 are uniquely conserved among the three NEAT domains and that their contributions are not absolutely necessary, the summation of the contributions by most of the residues within the pocket is likely to govern the heme binding and thus make it possible for the protein to compensate for deletion of the residue that directly coordinates the heme iron. The hydrophobic environment surrounding the heme-binding pocket might also contribute to the affinity of IsdH-NEAT3 for heme.

Biological Implications—Because iron is an important nutrient for both host cells and bacteria, we can expect that pathogenic bacteria take up iron efficiently in vivo. Indeed, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, a uropathogenic Staphylococcus that lives in an environment in which ion composition fluctuates readily, has an additional natural resistance-associated macrophage protein-1 (NRAMP) iron acquisition system for efficient harvesting of iron from host cells, even though staphylococci already typically have two NRAMPs (39). Because S. aureus lives in hostile environments of high salt concentration and low pH, efficient transport of heme by the Isd system likely is important.

In the Isd system, IsdH is thought to be the first acceptor of heme; the heme is transported to IsdA and then transferred to IsdC. Therefore, IsdH needs to effectively capture heme molecules from the exterior of the bacterial cell. Sharp et al. (12) reported that the capture of heme at the surface of the NEAT domain is suitable for the release of heme when the NEAT domain should transport heme to the acceptor proteins. The binding of a single IsdH-NEAT3 domain to multiple heme molecules, as demonstrated here, would contribute to the efficiency of heme transport, enabling the protein to transport several molecules of heme in one cycle. IsdH contains another two NEAT domains and is covalently anchored to the cell wall with the LPXTG motif in vivo, suggesting that the NEAT3 domain, as part of the whole IsdH, is unable to behave as an isolated domain in solution. To capture multimolecular heme with multimerization by the mechanism described above, IsdH needs to be expressed locally and abundantly to an extent that enables the functional domains to interact with each other. Considering the whole Isd system, all proteins involved need to be localized within an area in which the functional domains can interact to transfer the captured heme. This localization would enable the capture of multiple heme molecules by multimerization, even though the reduced flexibility of the system that results from attachment to other domains and anchoring to the cell surface would reduce the number of molecules multimerized. The localization of Isd proteins has not yet been elucidated, although the exact molecular properties of each NEAT domain are now being revealed. The molecular mechanisms operating at the staphylococcal cell surface, including the relationships among domains and proteins, need to be explored further. Such research would probably provide critical insights into the heme-acquiring mechanism of S. aureus and facilitate the development of means to overcome hospital-acquired S. aureus infection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Takano and R. Kuwahara (Hokkaido University) for their technical assistance, and the staff of Photon Factory for help during the x-ray diffraction experiments. We also thank Drs. M. Unno of Tohoku University and Y. Kuroiwa of the University of Tokyo for their helpful suggestions.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 2E7D and 2Z6F) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

This work was supported in part by the National Project on Protein Structural and Functional Analyses, Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan, and by grants-in-aid for younger scientists (to Y. T.) and general research (to K. T.) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1-S4.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: Isd, iron-regulated surface determinant; IsdX-NEATy, the yth domain of IsdX; ITC, isothermal titration calorimetry; SEC, size-exclusion chromatography; MAD, multiple-wavelength anomalous diffraction; NEAT, NEAr iron transporter; CAPS, N-cyclohexyl-3-aminopropanesulfonic acid.

References

- 1.Reniere, M. L., Torres, V. J., and Skaar, E. P. (2007) Biometals 20 333-345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ratledge, C., and Dover, L. G. (2000) Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54 881-941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazmanian, S. K., Skaar, E. P., Gaspar, A. H., Humayun, M., Gornicki, P., Jelenska, J., Joachmiak, A., Missiakas, D. M., and Schneewind, O. (2003) Science 299 906-909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maresso, A. W., and Schneewind, O. (2006) Biometals 19 193-203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stojiljkovic, I., and Perkins-Balding, D. (2002) DNA Cell Biol. 21 281-295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dinges, M. M., Orwin, P. M., and Schlievert, P. M. (2000) Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13 16-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneewind, O., Model, P., and Fischetti, V. A. (1992) Cell 70 267-281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skaar, E. P., Gaspar, A. H., and Schneewind, O. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 436-443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrade, M. A., Ciccarelli, F. D., Perez-Iratxeta, C., and Bork, P. (2002) Genome Biol. 3 RESEARCH0047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Pilpa, R. M., Fadeev, E. A., Villareal, V. A., Wong, M. L., Phillips, M., and Clubb, R. T. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 360 435-447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grigg, J. C., Vermeiren, C. L., Heinrichs, D. E., and Murphy, M. E. (2007) Mol. Microbiol. 63 139-149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharp, K. H., Schneider, S., Cockayne, A., and Paoli, M. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 10625-10631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dryla, A., Hoffmann, B., Gelbmann, D., Giefing, C., Hanner, M., Meinke, A., Anderson, A. S., Koppensteiner, W., Konrat, R., von Gabain, A., and Nagy, E. (2007) J. Bacteriol. 189 254-264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torres, V. J., Pishchany, G., Humayun, M., Schneewind, O., and Skaar, E. P. (2006) J. Bacteriol. 188 8421-8429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuklin, N. A., Clark, D. J., Secore, S., Cook, J., Cope, L. D., McNeely, T., Noble, L., Brown, M. J., Zorman, J. K., Wang, X. M., Pancari, G., Fan, H., Isett, K., Burgess, B., Bryan, J., Brownlow, M., George, H., Meinz, M., Liddell, M. E., Kelly, R., Schultz, L., Montgomery, D., Onishi, J., Losada, M., Martin, M., Ebert, T., Tan, C. Y., Schofield, T. L., Nagy, E., Meineke, A., Joyce, J. G., Kurtz, M. B., Caulfield, M. J., Jansen, K. U., McClements, W., and Anderson, A. S. (2006) Infect. Immun. 74 2215-2223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stranger-Jones, Y. K., Bae, T., and Schneewind, O. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103 16942-16947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hiramatsu, K., Aritaka, N., Hanaki, H., Kawasaki, S., Hosoda, Y., Hori, S., Fukuchi, Y., and Kobayashi, I. (1997) Lancet 350 1670-1673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanaka, Y., Morikawa, K., Ohki, Y., Yao, M., Tsumoto, K., Watanabe, N., Ohta, T., and Tanaka, I. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 5770-5780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gillam, E. M., Guo, Z., Martin, M. V., Jenkins, C. M., and Guengerich, F. P. (1995) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 319 540-550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Otwinowski, Z., and Minor, W. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 276 307-326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Terwilliger, T. C., and Berendzen, J. (1999) Acta Crystallogr. Sect D Biol. Crystallogr. 55 849-861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Terwilliger, T. C. (2000) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 56 965-972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Terwilliger, T. C., and Berendzen, J. (1999) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 55 1872-1877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Terwilliger, T. C. (2003) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 59 38-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terwilliger, T. C. (2003) Acta. Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 59 45-49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yao, M., Zhou, Y., and Tanaka, I. (2006) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62 189-196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brunger, A. T., Adams, P. D., Clore, G. M., DeLano, W. L., Gros, P., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Jiang, J. S., Kuszewski, J., Nilges, M., Pannu, N. S., Read, R. J., Rice, L. M., Simonson, T., and Warren, G. L. (1998) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54 905-921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vagin, A., and Teplyako, A. (1997) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 30 1022-1025 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murshudov, G. N., Vagin, A. A., and Dodson, E. J. (1997) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53 240-255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laskowski, R. A., MacArthur, M. W., Moss, D. S., and Thornton, J. M. (1993) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26 283-291 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riggs, A. (1981) in Methods in Enzymology (Antonini, E., Rossi-Bernardi, L, and Chiancone, E., eds) Vol. 76, pp. 5-28, Academic Press, New York7329272 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schuck, P. (2000) Biophys. J. 78 1606-1619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schuck, P., Perugini, M., Gonzales, N., Howlett, G., and Schubert, D, (2002) Biophys. J. 82 1096-1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laue, T. M., Shah, B. D., Ridgeway, T. M., and Pelletier, S. L. (1992) in Analytical Ultracentrifugation in Biochemistry and Polymer Science (Harding, S. E., Rowe, A. J., and Horton, J. C., eds) pp. 90-125, Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, UK

- 35.de Villiers, K. A., Kaschula, C. H., Egan, T. J., and Marques, H. M. (2007) J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 12 101-117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pagola, S., Stephens, P. W., Bohle, D. S., Kosar, A. D., and Madsen, S. K. (2000) Nature 404 307-310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Montano, G. A., Bowen, B. P., LaBelle, J. T., Woodbury, N. W., Pizziconi, V. B., and Blankenship, R. E. (2003) Biophys. J. 85 2560-2565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aranda, R. T., Worley, C. E., Liu, M., Bitto, E., Cates, M. S., Olson, J. S., Lei, B., and Phillips, G. N., Jr. (2007) J. Mol. Biol. 374 374-383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuroda, M., Yamashita, A., Hirakawa, H., Kumano, M., Morikawa, K., Higashide, M., Maruyama, A., Inose, Y., Matoba, K., Toh, H., Kuhara, S., Hattori, M., and Ohta, T. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102 13272-13277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.