Abstract

EDTA has become a major organic pollutant in the environment because of its extreme usage and resistance to biodegradation. Recently, two critical enzymes, EDTA monooxygenase (EmoA) and NADH:FMN oxidoreductase (EmoB), belonging to the newly established two-component flavin-diffusible monooxygenase family, were identified in the EDTA degradation pathway in Mesorhizobium sp. BNC1. EmoA is an FMNH2-dependent enzyme that requires EmoB to provide FMNH2 for the conversion of EDTA to ethylenediaminediacetate. To understand the molecular basis of this FMN-mediated reaction, the crystal structures of the apo-form, FMN·FMN complex, and FMN·NADH complex of EmoB were determined at 2.5Å resolution. The structure of EmoB is a homotetramer consisting of four α/β-single-domain monomers of five parallel β-strands flanked by five α-helices, which is quite different from those of other known two-component flavin-diffusible monooxygenase family members, such as PheA2 and HpaC, in terms of both tertiary and quaternary structures. For the first time, the crystal structures of both the FMN·FMN and FMN·NADH complexes of an NADH:FMN oxidoreductase were determined. Two stacked isoalloxazine rings and nicotinamide/isoalloxazine rings were at a proper distance for hydride transfer. The structures indicated a ping-pong reaction mechanism, which was confirmed by activity assays. Thus, the structural data offer detailed mechanistic information for hydride transfer between NADH to an enzyme-bound FMN and between the bound FMNH2 and a diffusible FMN.

EDTA has quietly become a major organic pollutant, currently present in the environment at higher concentrations than any other organic pollutant (1). A high level of EDTA in natural waters is due to its extensive usage, such as in industrial cleaning to remove calcium deposits, in detergent as a sequestering agent, in phytoremediation to mobilize heavy metals, and in scientific laboratories as a chelating agent (2, 3). EDTA is recalcitrant to biodegradation and exists mainly in metal·EDTA complexes, many of which are toxic (4, 5). In addition, the codisposal of EDTA with radionuclides has led to the enhanced mobilization of radionuclides in groundwater, rapidly spreading radioactive contamination (3, 6-8). Concerns over EDTA recalcitrance and the potential mobilization of heavy metals and radionuclides have led the European Union, Australia, and some parts of the United States to ban EDTA in detergent. It is now also being carefully controlled in many other products to reduce contamination of water resources.

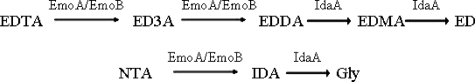

Several bacteria that can degrade EDTA and the related compound, nitrilotriacetate, and use them as a sole source of carbon and energy have been isolated (9-12). They are phylogenetically related to Mesorhizobium and Agrobacterium species (11), likely forming a new branch within the Phyllobacteriaceae, the “Mesorhizobia” family (13). In these bacteria, reduced flavin mononucleotide (FMNH2)-dependent EDTA monooxygenase (EmoA) and NADH:FMN oxidoreductase (EmoB) together oxidize EDTA to ethylenediaminediacetate (6). Then, ethylenediaminediacetate oxidase (IdaA) oxidizes ethylenedia-minediacetate to ethylenediamine (Fig. 1) (14).

FIGURE 1.

EDTA and nitrilotriacetate (a structural homolog of EDTA) degradation pathway. The enzymes are EDTA monooxygenase (encoded by emoA), NADH:FMN oxidoreductase (emoB), and ethylenediaminediacetate/iminodiacetate oxygenase (idaA). Each enzymatic step removes an acetate group as a glyoxylate. ED3A, ethylenediaminetriacetate; EDDA, ethylenediaminediacetate; EDMA, ethylenediaminemonoacetate; ED, ethylenediamine; NTA, nitrilotriacetate; IDA, iminodiacetate; Gly, glycine.

EmoA and EmoB are members of the recently discovered two-component flavin-diffusible monooxygenase (TC-FDM)3 family, consisting of a large monooxygenase component and a small NAD(P)H:flavin oxidoreductase component. A demonstrable physiological function of the small component of TC-FDM is to provide reduced flavins to the large component. Bacterial luciferase of Vibrio fischeri is the first reported FMNH2-dependent monooxygenase (15). Recently, more FMNH2-dependent monooxygenases have been discovered, including pristinamycin IIA synthase of Streptomyces pristinaespiralis (16), two monooxygenases involved in desulfurization of dibenzothiophene in Rhodococcus sp. strain IGTS8 (17), organosulfur monooxygenases (SsuD) in Pseudomonas putida S-313 (18), and EDTA monooxygenase in Mesorhizobium sp. bacterium BNC1 (6). Furthermore, reduced flavin adenine dinucleotide (FADH2)-dependent monooxygenases have been discovered, including 4-hydroxyphenylacetate monooxygenase of Escherichia coli strain W (19), 2,4,6-trichlorophenol 4-monooxygenase of Cupriavidus necator JMP134 (20), and 2,4,5-trichlorophenol 4-monooxygenase of Burkholderia cepacia AC1100 (21). All of these monooxygenases have a small-component NAD(P)H:flavin oxidoreductase as a partner, and the genes coding for the two components are normally physically linked and often organized in the same operon.

Some of the small-component NAD(P)H:flavin oxidoreductases, which have tightly bound FAD or FMN as a prosthetic group, follow a Ping Pong Bi Bi mechanism; however, the ones that do not have tightly bound flavins seem to follow an ordered sequential mechanism (22-24). For example, PheA2 is a small-component reductase that supplies FADH2 to PheA1, a large-component monooxygenase for phenol hydroxylation. PheA2 has a tightly bound FAD prosthetic group (Kd = 10 nm), and its reaction follows a Ping Pong Bi Bi mechanism. HpaCSt, the small-component reductase for 4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-monooxygenase from Sulfolobus tokodaii, has a tightly bound FMN, probably also following a Ping Pong Bi Bi mechanism. However, another HpaC from Thermus thermophilus HB8 and EmoB from Mesorhizobium sp. BCN1 have weakly bound FAD and FMN, respectively (6, 25), but their reaction mechanisms are unknown so far. Crystal structures for some of these small-component reductases have been reported, such as PheA2 (26), HpaCSt (27), and HpaCTt (25). In addition to their structural similarities, the crystal structures of HpaCSt and PheA2 reveal tightly bound FAD and FMN, respectively. The crystal structure of HpaCTt shows FAD at low occupancy, as expected.

Interest in the structures and catalytic mechanisms of EmoB, which supplies FMNH2 to EmoA for EDTA degradation, is due to its important physiological and future environmental roles (6). Purified recombinant EmoB does not contain a bound flavin, reflecting its loose binding of FMN. Here, we demonstrate that EmoB reduces FMN following a Ping Pong Bi Bi mechanism and have determined the corresponding crystal structures for two separate stages of catalysis. Therefore, we are able to provide complete structural features and explain the reaction mechanism. In addition, systematic investigations using light scattering and isothermal calorimetry offer critical information about EmoB in the EDTA degradation pathway.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Expression and Purification of EmoB—The EmoB open reading frame was cloned from the Gram-negative bacterium BNC1 into the pET30 vector for overexpression of the protein as described previously (6). For EmoB expression, 100 ml of LB medium supplemented with 30 μg/ml kanamycin was inoculated from a freezer stock of pET30EmoB in BL21(DE3) cells. After growing overnight at 37 °C, this culture was used to inoculate 1 liter of LB medium in a 4-liter flask. Cells were grown at 37 °C with constant shaking until the absorbance at 600 nm reached 0.6; the temperature of the shaker was then reduced to 20 °C, and 0.5 mm isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was added to induce EmoB expression. After incubation for an additional 10 h, the induced cells were harvested by centrifugation. The resulting cell pellet was resuspended in 40 ml of lysis buffer (50 mm sodium phosphate (pH 8.0), 300 mm NaCl, and 20 mm imidazole) and sonicated five times for 10 s each (Model 450 Sonifier®, Branson Ultrasonics Corp.), and the lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 38,000 × g for 45 min.

The cleared lysate was applied to a nickel-nitrilotriacetate column, and the column was washed extensively with lysis buffer. Protein was eluted from the column with lysis buffer containing 300 mm imidazole. Fractions containing EmoB were pooled, concentrated, and exchanged into 20 mm Tris buffer (pH 7.5) and then applied to an ion exchange column (Toyopearl DEAE-650M). Protein was eluted with a linear NaCl gradient.

The selenomethionine derivative of EmoB was made by transforming pET30EmoBL142M into the methionine auxotroph E. coli strain B834(DE3) (Novagen) and was cultured in minimal medium containing 30 mg/liter selenomethionine. Purification of selenomethionyl-EmoB was performed following the protocol for native EmoB except for the addition of 1 mm dithiothreitol in every buffer to prevent oxidation of the selenomethionine.

All the purification steps for both native EmoB and the selenomethionine derivative were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 12% Tris/glycine/SDS-polyacrylamide gel stained with Coomassie Blue. Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford assay using bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Molecular Mass Determination—The weight average molecular mass of EmoB was measured by combined size exclusion chromatography and multiangle laser light scattering (MALLS) as described previously (28). In brief, 100 μg of EmoB was loaded onto a BioSep-SEC-S-2000 column (Phenomenex) and eluted with phosphate-buffered saline. The eluate was passed through a tandem UV detector (Gilson), an interferometric refractometer (Optilab DSP, Wyatt Technology Corp.), and a laser light-scattering detector (Dawn EOS, Wyatt Technology Corp.). The light scattering data were analyzed with Astra software (Wyatt Technology Corp.) using the Zimm fitting method.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)—The interactions between EmoB and FMN, riboflavin, and NAD+ were measured using a MicroCal VP-ITC instrument at 25 °C following standard procedures. The protein was dialyzed into 20 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 150 mm NaCl. The protein was added to the calorimetric reaction cell at a concentration of 0.01 mm and titrated with 0.1 mm FMN, NAD+, or riboflavin in the same buffer. Enzyme and ligand solutions were degassed prior to use. Each titration experiment was performed with 29 injections of 10 μl at 300-s equilibration intervals. Heats of dilution for an individual ligand were determined by titrating ligand into the same buffer without protein and were used to correct the protein titration. Data were fit to a single-site binding model by nonlinear least-squares regression with the Origin software package. The fit of data yields the binding affinity, enthalpy change, entropy change, and binding stoichiometry for the titration.

Kinetics of EmoB Reduction—Enzyme assays were conducted in 20 mm potassium phosphate (pH 7.0) at 25 °C. FMN and NADH concentrations were varied from 0.5 to 5 μm and 19 to 78 μm, respectively. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 6.3 nm EmoB. NADH:FMN oxidoreductase activity was monitored by following the decrease in NADH absorbance at 340 nm (ε340 = 6220 m-1 cm-1) using an Ultrospec 4000 spectrophotometer (GE Healthcare).

Crystallization and Data Collection—Apo-form crystals of recombinant EmoB were grown at 4 °C using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method. For apo-form crystallization, the solution of purified EmoB (10 mg/ml) in 20 mm sodium acetate (pH 5), 1 mm EDTA, and 1 mm dithiothreitol was mixed with an equal volume of the reservoir solution (0.1 m MES (pH 6.5), 1.6 m (NH4)2SO4, and 10% dioxane) and equilibrated against the reservoir. Diffraction quality crystals appeared after 10 days. Crystals of selenomethionyl-EmoB were prepared in the identical fashion except with 1 mm dithiothreitol.

The apo-form crystals of EmoB belong to the hexagonal crystal system with unit cell dimensions of a = b = 101.59 Å and c = 130.16 Å. The space group of these crystals was later determined to be P6422 after disproving P6222. There is one EmoB molecule in the asymmetric unit. Diffraction data up to 2.9 and 2.5 Å resolution were collected with a CCD detector/rotating anode x-ray generator (Saturn 92/MicroMax-007 x-ray generator, Rigaku/MSC) and at the Berkeley Advanced Light Source (beam line 8.2.1), respectively. For data collection at 100 K, crystals were transferred stepwise to a cryoprotection solution containing all components of the reservoir solution with 25% glycerol. The selenomethionyl-EmoB crystals were grown under the same conditions and found to be the same space group as the native crystals. To use the multiwavelength anomalous diffraction (MAD) method for phasing, data to 2.5 Å resolution were collected at 100 K at the Berkeley Advanced Light Source (beam line 8.2.1). The x-ray fluorescence spectrum was recorded and used to select wavelengths for subsequent MAD data collection. Data were collected at the selenium absorption peak λ = 0.97925 Å (12,660.73 eV), the absorption inflection λ = 0.97942 Å (12,658.53 eV), and the remote reference wave-length λ = 0.91162 Å (13,600 eV). For complex crystals with FMN, riboflavin, FMN·NADH, and riboflavin·NADH, the soaking method was used. For the FMN or riboflavin complex, the apo-form EmoB crystals were incubated for 2 h at 4 °C in a crystallization mother liquor solution containing either 1 mm FMN or riboflavin. For the FMN·NADH or riboflavin·NADH complex, the apo-form crystals were soaked for 2 h in the mother liquor solution containing either 1 mm FMN or riboflavin and then moved to the mother liquor solution containing 1 mm NADH. The corresponding complex data were collected at the Berkeley Advanced Light Source (beam line 8.2.1). The cell dimensions for the corresponding unit cells of FMN- and riboflavin-soaked crystals were a = 101.27 and c = 130.22 Å and a = 100.92 and c = 129.61 Å, respectively. The cell dimensions for FMN·NADH- and riboflavin·NADH-soaked crystals were a = 101.18 and c = 129.71 Å and a = 102.11 and c = 130.41 Å, respectively. Diffraction data were collected up to 2.5 Å for the complex crystals. All diffraction data were processed and scaled with the HKL2000 package (29) and CrystalClear 1.3.6 (Rigaku/MSC). The statistics for the diffraction data are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Crystallographic data for the apo-form and FMN·FMN and FMN·NADH complexes of EmoB

P, peak; I, inflection; R, remote; r.m.s.d., root mean square deviation.

|

Apo

|

FMN·FMN complex

|

FMN·NADH complex

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native | Se-MAD | |||

| Data | ||||

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.0332 | 0.97925 (P), 0.97942 (I), 0.91162 (R) | 1.54 | 1.54 |

| Resolution (Å) | 20-2.5 | 47.4-2.66 (P), 47.4-2.66 (I), 47.4-2.62 (R) | 20-2.5 | 20-2.5 |

| Space group | P6422 | P6422 | P6422 | P6422 |

| Cell dimensions (Å) | a = 101.59, c = 130.16 | a = 101.78, c = 130.07 | a = 101.27, c = 130.22 | a = 101.18, c = 129.71 |

| Asymmetric unit | 1 molecule | 1 molecule | 1 molecule | 1 molecule |

| Total observations | 233,238 | 133,802 (P), 136,160 (I), 141,191 (R) | 233,187 | 233,200 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (99.7) | 100.0 (100.0) | 99.9 (99.3) | 99.9 (99.5) |

| Rsymab | 5.5 (13.6) | 8.3 (13.9) (P), 9.5 (14.4) (I), 9.8 (16.0) (R) | 5.7 (11.4) | 4.5 (9.5) |

| Refinement | ||||

| Resolution (Å) | 12-2.5 | 12-2.5 | 12-2.5 | |

| No. of reflections (>2σ) | 12,415 (89%) | 13,826 (99%) | 13,264 (96%) | |

| Rcrystc | 20.2 | 20.3 | 20.2 | |

| Rfreed | 23.6 | 23.2 | 23.8 | |

| r.m.s.d. bonds (Å) | 0.014 | 0.016 | 0.016 | |

| r.m.s.d. angles | 3.185° | 3.85° | 3.82° | |

| No. of atoms | ||||

| Protein and ligand | 1418 | 1480 | 1493 | |

| Water | 127 | 121 | 122 | |

Numbers in parentheses refer to the highest resolution shell.

Rsym = ∑|Ih - <Ih>|/∑Ih, where <Ih> is the average intensity over symmetry equivalent reflections.

Rcryst = ∑|Fo - Fc|/∑Fo, where summation is over the data used for refinement.

Rfree was calculated as for Rcryst using 5% of the data that were excluded from refinement.

Phasing and Refinement—Initial phases of the EmoB crystal structure were determined by the MAD phasing method (30) using the software SOLVE (31) after prior approaches with the molecular replacement method. Data collected at the remote wavelength were treated as the reference data set, and resolution limits of 40-2.7 Å were imposed. Experimental values of f′ and f″ estimated from fluorescence spectra were used. The selenium site was located, and the resulting phases had a figure of merit of 0.51. A density modification process using the maximum likelihood method was performed with the software RESOLVE (32), which eventually resulted in a clearly interpretable electron density map with many well defined secondary structural elements. The corresponding amino acids were assigned and manually fitted into this map using the software O (33). The resulting rough coordinates of the EmoB structure were refined using X-PLOR (34) with the simulated annealing protocol, resulting in a crystallographic R value of 28%. Several rounds of manual adjustment followed cycles of refinement, and picking solvent molecules led to an R factor of 20.2% (Rfree = 23.6% for the random 5% data). The structures of the complexes of EmoB were then solved using the refined coordinates of the apo-form EmoB. The final R factors for the FMN·FMN and FMN·NADH complexes of EmoB were 20.3% (Rfree = 23.2% for the random 5% data) and 20.2% (Rfree = 23.8%), respectively (see Table 1). The number of reflections above the 2σ level for the apo-form and FMN·FMN and FMN·NADH complexes was 12,415 (89% completeness), 13,826 (99%), and 13,264 (96%) between 12.0 and 2.5 Å resolution, respectively. The root mean square deviations from ideal geometry of the final coordinates corresponding to the apo-form and complexes were 0.014, 0.016, and 0.016 Å for bonds and 3.18, 3.85, and 3.82° for angles, respectively. All EmoB coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank: 2VZF (apo-form), 2VZH (FMN·FMN complex), and 2VZJ (FMN·NADH complex).

RESULTS

Recombinant EmoB from Mesorhizobium sp. BNC1 was purified, and its corresponding structures in the apo-form and FMN·FMN and FMN·NADH complexes were determined at 2.5 Å resolution. The apo-forms of both native and selenomethionine-substituted enzymes were crystallized in the same hexagonal space group, P6422, with one molecule/asymmetric unit (Table 1). The structure of the apo-form EmoB was determined by the selenomethionyl MAD method (30). Most of the backbone and side chain residues were fitted using the selenomethionyl MAD map, but the electron density for the C-terminal seven residues and most of the side chains of residues 145-156 was not visible due to disorder. The final R factor for the apo-form EmoB was 20.2% (Rfree = 23.6%) for 12,415 (12-2.5 Å) unique reflections. In turn, both complex structures were determined using the coordinates of the deduced apoform EmoB structure. Detailed crystallographic data are reported in Table 1.

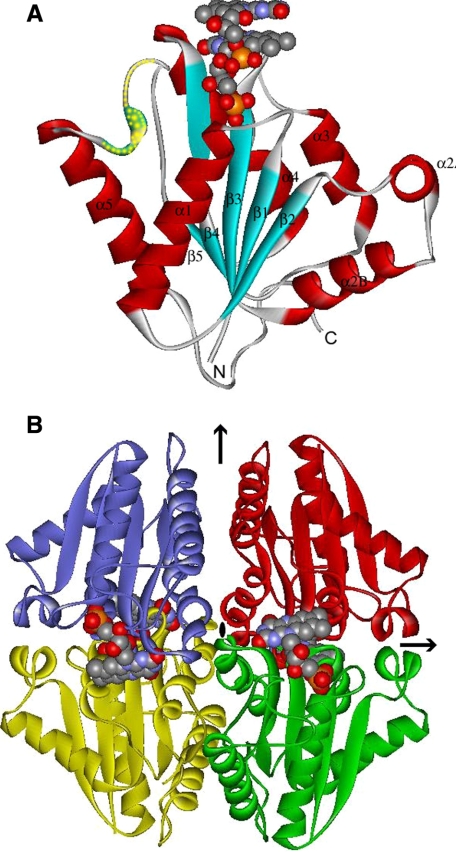

Global Structure—The structure of the EmoB molecule showed that it is a single-domain enzyme and belongs to a globular α/β-structure similar to that of flavodoxin. It consists of a central five-stranded parallel β-strand flanked by either two (α1 and α5) or four (α2A, α2B, α3, and α4) α-helices on both sides of the sheet (Fig. 2A). The twisted central β-sheet constituting the core of the enzyme is arranged in the order β2-β1-β3-β4-β5. Among the five β-strands, β5 uniquely has a two-residue bulge at Val137 and Gln138, which is observed in every compared NAD(P)H:flavin oxidoreductase mentioned below, even though the size of each bulge is somewhat different. In fact, based on the presence of this ∼20-residue loop inserted at this bulged site, flavodoxins are classified into two groups, long and short flavodoxins, even though the corresponding functions for most of them are not clearly known (35). Therefore, EmoB could belong to a short flavodoxin subfamily in terms of its core structure. Distinctively, most of the surface residues of the central β-sheet that constitutes the core of EmoB have a hydrophobic nature. Those hydrophobic residues interact with the hydrophobic side of the amphiphilic α-helices, the hydrophilic faces of which, together with hydrophilic loops, are exposed to solvent. Therefore, the surface residues of EmoB are very hydrophilic, explaining its high solubility reaching ∼0.5 mm in phosphate-buffered saline. The overall structures of the apoform and complex structures show no major differences in terms of their backbone structures. The C-α carbons among the apo-form and complexes are superimposable, with root mean square deviations values of 0.2-0.3 Å without including the flexible area (the residues between positions 144 and 156). However, the side chains of several residues show different conformations to accommodate FMN and NADH binding.

FIGURE 2.

Crystal structure of EmoB. A, structural element distribution of the monomeric form. Secondary structure elements have been numbered sequentially as α1-α5 and β1-β5 following the convention. N and C refer to N- and C-terminal regions, respectively. The disordered area (and the area of high temperature factors) is indicated by yellow dots. The FMN molecules are represented by the Corey-Pauling-Koltun model. B, arrangements of tetrameric EmoB in D2 symmetry. The black arrows and central oval indicate the location of the crystallographic 2-fold axis. The relative packing orientation observed in the pair of the yellow and green molecules (or blue and red) is typical among many dimeric NAD(P)H:flavin oxidoreductases. The figures were made using WebLab ViewerLite 3.20 (Accelrys Inc.).

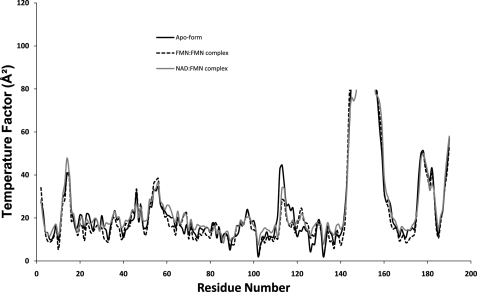

As shown clearly in Fig. 3, most of the loop regions have slightly elevated temperature factors, especially the loop connecting α5 and β5, which show very high values and contain disordered side chains in the middle. However, temperature factors of the residues corresponding to two loops, between β3 and α3 and between α3 and β4, are similar to those of the secondary structures of the β-sheet core due to the existence of many hydrogen bonds. As mentioned in detail below, one of these areas, a loop connecting β3 and α3 (residues 78-86), constitutes the bottom of the FMN-binding pocket. Notably, the corresponding temperature factors for residues 112-114 are reduced significantly upon complex formation.

FIGURE 3.

Backbone temperature factor plots of EmoB crystal structures: the apo-form and the FMN·FMN and NAD·FMN complexes. Residues 144-156 of the apo-form and complexes show the temperature factors of their corresponding C-α atoms above 40 Å2. Residues 112-114 have significantly lower temperature factors in the complex structures compared with the apo-form.

Oligomer State—A crystallographic symmetry operation assembled one EmoB molecule in the asymmetric unit into a tightly associated tetrameric unit in the crystal lattice (Fig. 2B). This oligomeric status of EmoB as a tetramer was verified in solution by an MALLS experiment. MALLS analyses of solutions of both apo-EmoB and the FMN complex were done, and both were shown to be a tetramer (supplemental figure). The observed tetramer interface has an extensive network of symmetrically oriented intersubunit hydrogen bonds. These intersubunit interactions are mainly between residues of α4 and its flanking loops, i.e. hydrogen bonds between the hydroxyl group of Tyr122 and the backbone amide nitrogen of Ala82, the hydroxyl groups of Ser83 and Tyr84, the side chain amide group of Lys81 and the backbone carbonyl oxygen of Leu95, the carboxyl side chain of Asp93 and the backbone amide nitrogen of Gly86, and the side chain amide group of Lys89 and the backbone carbonyl oxygens of Tyr80 and Tyr84. As mentioned below, the backbone of Ala82, which participates in the inter-subunit interaction, also coordinates the O-4 atom of the isoalloxazine ring; thus, the observed tetramer interaction is also associated with FMN binding.

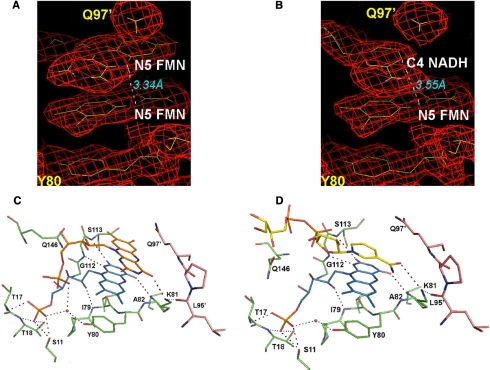

FMN- and NADH-binding Site—The Fo - Fc maps of the FMN-soaked crystal data clearly show the corresponding electron density for two bound FMN molecules at the carboxyl edge of the β-sheet (Fig. 4A). They are stacked through the si-faces of the isoalloxazine rings. However, the same area calculated from the riboflavin-soaked crystal data does not have any density. In the FMN complex structure, two FMN molecules have similar conformations, and the ribityl moieties of both FMN molecules adopt an extended conformation. For clarity, the deeply inserted FMN molecule is referred to as the first FMN through-out this study. The first FMN is in the crevice located at the topological switch point (or chain reversal point), as observed in many flavoproteins (36). The phosphoribityl group of this first FMN molecule is in the relatively shallow pocket formed by the two loops between β1 and α1 and between β5 and α5, and the edge of its isoalloxazine ring is surrounded by parts of the loop connecting β3 and α3 and the loop connecting β4 and α4. In detail, the phosphate group of the first FMN molecule is within hydrogen bond distance of the side chains of Ser11, Ser16, and Thr18 and the backbone nitrogen atoms of Thr17 and Thr18, which together constitute the hydrophilic bottom of the pocket (Fig. 4). The apo-form has a phosphate ion at the same position as the phosphate group of the first FMN. The ribityl O-2* and O-3* are hydrogen-bonded to the backbone nitrogen atom of Ile-79 and a solvent molecule that is connected to the phenolic side chain of Tyr80. The O-2 and O4 atoms in isoalloxazine form hydrogen bond with the backbone nitrogen atoms of Ala82, Gly112, and Ser113. Consequently, their observed temperature factors are reduced upon complex formation (Fig. 3). The phenol ring of Tyr80 is also in a stacked position with the isoalloxazine ring of the first FMN. In contrast to this strongly coordinated interaction for the first inserted FMN molecule, the other FMN molecule that is stacked with the FMN (referred to as the second FMN for clarity) is located at the surface of the enzyme exposed partially to solvent with fewer interactions with EmoB, i.e. only the O-4 atom of its isoalloxazine ring is hydrogen-bonded to the side chain of Lys81 in addition to its phosphate group being hydrogen-bonded to a solvent molecule, which is coordinated in turn by the phenol side chain of Tyr80 and the phosphate group of the first FMN.

FIGURE 4.

Observed potential interactions in the FMN·FMN and FMN·NADH complexes of EmoB. Shown are difference Fourier maps covering two stacked isoalloxazine rings of FMN molecules (A) and nicotinamide and isoalloxazine rings (B) at a contour level of 1.0 σ. The distance between two N-5 atoms is indicated. The participating residues in coordinating two FMN molecules (C) and FMN and NAD(H) molecules (D) are shown with their residue numbers. The residues are depicted in light green and pink to represent belonging to two different subunits.

On the other hand, the Fo - Fc maps generated with the data collected from the crystal soaked with both FMN and NADH clearly show the corresponding electron density for both FMN and NADH molecules stacked through their isoalloxazine and nicotinamide rings (Fig. 4B). The position of the FMN molecule in this FMN·NADH complex is superimposable with the first FMN molecule in the FMN·FMN complex structure. The amine group of Lys81 is also within hydrogen bond distance of the amide group of NADH, the re-face (A-side) of which faces the isoalloxazine ring. The corresponding density for the adenosine part of NADH is not visible, indicating its disordered character. In addition to Lys81, the backbone carbonyl group of Gly112 and the ribityl oxygen of the first FMN are within hydrogen bond distance of the phosphate groups of the NAD(H) molecule. However, the Fo - Fc maps generated from the crystals soaked in the mother liquor solution containing both 1 mm riboflavin and 1 mm NADH for various times (2-48 h) show neither riboflavin nor NADH.

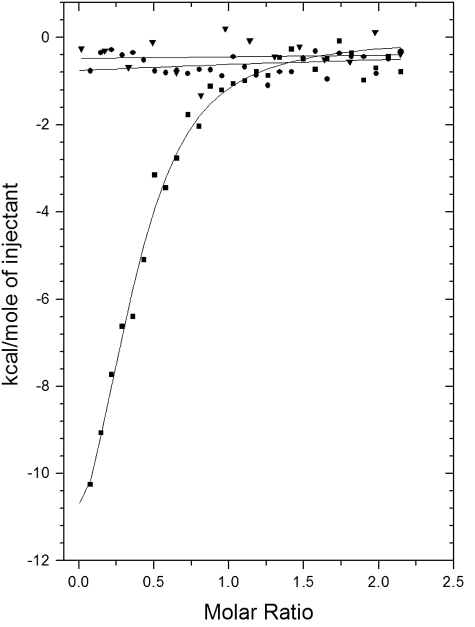

ITC—To confirm the differential binding affinities between FMN, riboflavin, and NAD(H) with the EmoB protein, thermodynamic characterizations were done with ITC. As shown in Fig. 5, a significant amount of heat was released when EmoB associated with FMN, indicating that the binding interactions had significant enthalpic contributions (ΔH = -15.3 kcal/mol). Analysis of the ITC data revealed a slightly unfavorable entropic contribution (ΔS = -24.7 cal/mol/degree), possibly indicating that the EmoB structure was slightly stabilized upon binding to FMN and that very few solvent molecules were freed from the pocket. These were consistent with structural data, as indicated by the significant reduction of the B values for two loops constituting the binding pocket upon formation of the FMN binary complex. There were few solvent molecules in the FMN-binding pocket. The calculated Kd for FMN from ITC data analysis was ∼0.42 μm. Neither riboflavin nor NADH independently showed any significant binding to EmoB (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 5.

Measurement of FMN, riboflavin, or NADH binding by ITC experiments. The trend of heat released by serial injections of FMN (▪), riboflavin (▾), or NADH (•) into EmoB was monitored. FMN showed the typical heat-releasing pattern. Neither riboflavin nor NADH had any detectable heat-releasing events upon injections. Solid lines represent the least-square fits of the data using a single-site binding model.

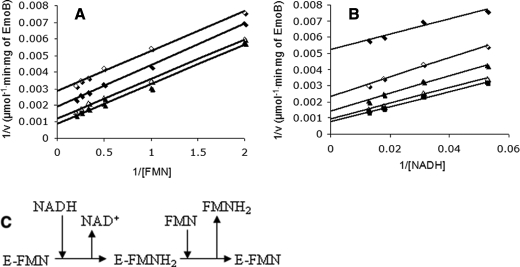

Enzyme Kinetics—To understand the enzyme reaction of EmoB, steady-state kinetics experiments were performed by holding the concentration of EmoB constant at 6.3 nm while FMN concentrations were varied from 0.5 to 5 μm. The corresponding NADH concentrations in four sets of experiments were 19, 32, 56, and 78 μm. The five sets of equivalent experiments were performed by varying the NADH concentration with FMN concentrations of 0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 4 μm. As shown in Fig. 6, the double-reciprocal plots of the rate against substrate concentration show parallel-line kinetics, indicating its ping-pong mechanism. The calculated Km values for FMN and NADH were 1.7 ± 0.6 and 23.9 ± 2.8 μm, respectively. The Vmax value was 1111 ± 117 μmol/min/mg.

FIGURE 6.

Double-reciprocal plots of initial velocities of EmoB versus substrate concentrations. A, enzyme activity was assayed with constant concentrations of NADH: 19 μm (⋄), 32 μm (♦), 56 μm Δ, and 78 μm (▴). B, enzyme activity was assayed with constant concentrations of FMN: 0.5 μm (♦), 1 μm (⋄), 2 μm ▴, 3 μm Δ, and 4 μm (▪). C, shown is the deduced ping-pong reaction mechanism of EmoB from kinetic analysis.

DISCUSSION

NAD(P)H:flavin oxidoreductases, to which EmoB belongs, catalyze a wide range of electron transfer reactions. The exact biological function and electron transfer mechanism of most of these enzymes are not known (37). We have investigated the structure of EmoB to shed light on its biological function, reaction mechanism, and structural relationship to other members in this functional class.

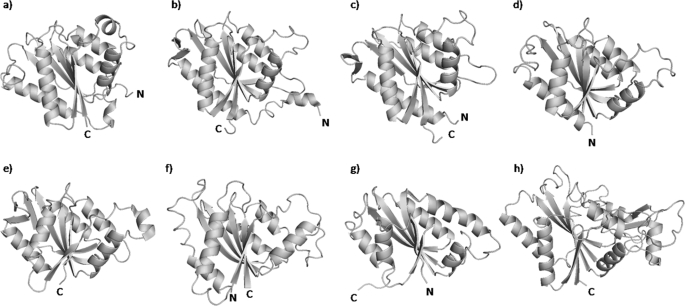

The structure of EmoB, a flavodoxin-like tetramer, is quite different from those of other TC-FDM family members, such as PheA2, HpaCSt, and HpaCTt. These family members all have a dimeric character and a β-barrel-like structure similar to the structures of ferric reductases or FAD-binding domains of ferredoxin reductases (25, 26). To establish the proper structural classification for EmoB and to identify its structural homologs, a detailed comparison with available structures in the Protein Data Base was carried out using a Dali search (38). The results showed that the most similar structure is a putative flavin-binding arsenic-resistance protein from Shigella flexneri (code 2FZV) with a high Z score of 20.1, followed by azobenzene reductase from Bacillus subtilis (code 1NNI) with a Z score of 18.2 and a putative NADH-dependent reductase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01 (code 1RTT) with a Z score of 17.7 (Fig. 7). Despite their unclear functionality, these proteins all belong to the flavodoxin-like flavoprotein family or have at least known flavin-binding ability.

FIGURE 7.

Ribbon diagrams representing the structures of EmoB (Protein Data Bank code 2VZF; a), flavin-binding protein from S. flexneri (code 2FZV; b), flavoprotein ArsH from S. meliloti (code 2Q62; c), azobenzene reductase from B. subtilis (code 1NNI; d), putative reductase from P. aeruginosa PA01 (code 1RTT; e), NAD(P)H:FMN oxidoreductase from S. cerevisiae (code 1T0I; f), Trp repressor-binding protein from B. subtilis (code 1RLI; g), and quinone reductase from rat (code 1QRD; h). The figures were made using PyMOL (DeLano Scientific LLC).

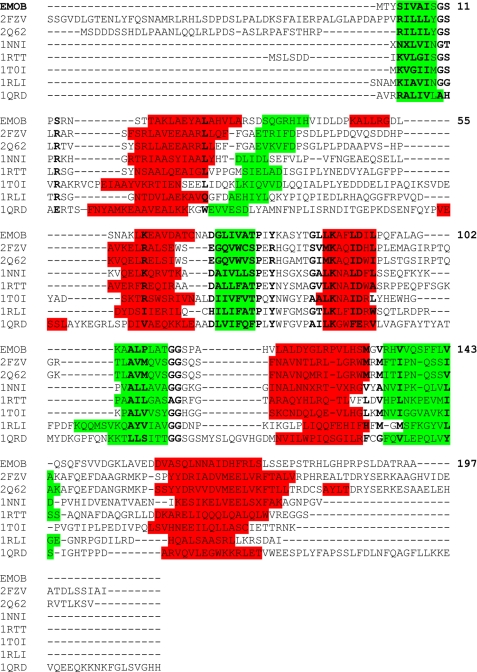

Comparison of sequence similarity to known structures suggested the structural classification of EmoB. A search for similar amino acid sequences in the Protein Data Bank using BLAST (39) revealed that FMN-dependent azoreductase from Enterococcus faecalis (code 2HPV) shows the highest score (31.6 bits) with 23% identity among matched amino acids to EmoB, followed by a putative NADH-dependent reductase from P. aeruginosa PA01 (code 1RTT; 31.2 bits, 26% identity), Trp repressor-binding protein from B. subtilis (code 1RLI; 30.8 bits, 32% identity), a probable short chain dehydrogenase from P. aeruginosa (code 2NWQ; 29.3 bits, 28% identity), and ArsH from Sinorhizobium meliloti (code 2Q62; 29.3 bits, 27% identity) (Fig. 7). Overall, however, the level of sequence identity is low, and most of the BLAST alignments are rather random. A meaningful sequence alignment was possible only by manual alignment with a structural guide (Fig. 8); however, even that approach was not possible for 2HPV and 2NWQ. The conserved residues are distributed sporadically mainly through the entire secondary structural elements (Fig. 8). In general, the enzymes with the highest similarity scores have a mixed β-sheet at the core of the enzyme with the same topological order as observed in EmoB (Fig. 7), but a detailed visual inspection revealed a great deal of structural heterogeneity in terms of the number and size of helices in the peripheral regions, which could correlate with the great functional diversity among them.

FIGURE 8.

Amino acid sequence alignment of EmoB with other flavin-dependent oxidoreductases. Secondary structural elements are highlighted in green for the β-strands and in red for the α-helices. Code 2FZV is the flavin-binding protein from S. flexneri; code 2Q62 is the flavoprotein ArsH from S. meliloti; code 1NNI is the azobenzene reductase from B. subtilis; code 1RTT is the putative reductase from P. aeruginosa PA01; code 1T0I is the NAD(P)H:FMN oxidoreductase from S. cerevisiae; code 1RLI is the Trp repressor-binding protein from B. subtilis; and code 1QRD is the quinone reductase from rat.

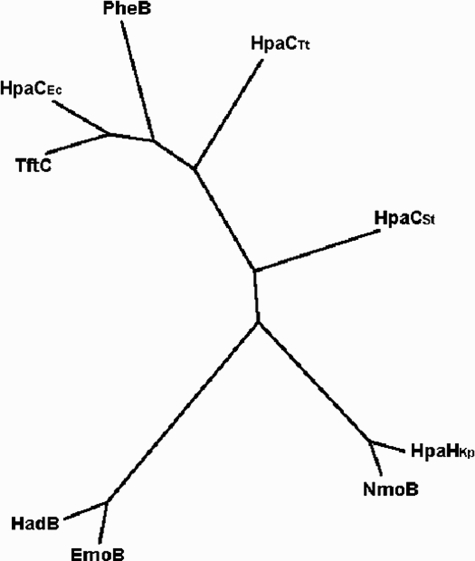

Significantly, none of the enzymes belonging to the TC-FDM family were found in our Dali and BLAST searches. As shown in Fig. 9, EmoB is somewhat distant from the other known small components of the TC-FDM family members in terms of their primary sequence. This is consistent with the differences found in the secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures of EmoB compared with PheA2 and HpaC. This is probably due to the fact that a small component of TC-FDM, the sole function of which is to provide reducing power (through FADH2 or FMNH2) to its partner monooxygenases, does not have to evolve in a parallel way.

FIGURE 9.

Phylogenetic tree of the small component B of the TC-FDM family. Sequence alignment was done using ClustalW, and the multiple alignment analysis was done using a PHYLIP program. The tree was obtained using TreeView. TftC is 2,4,5-trichlorophenol 4-monooxygenase component B from B. cepacia; HadB is 2,4,6-trichlorophenol 4-monooxygenase component B from Ralstonia pickettii; HpaCEc is 4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-monooxygenase component B from E. coli; HpaCSt is 4-hydroxyphenylacetate hydroxylase component B from S. tokodaii; HpaCTt is 4-hydroxy-phenylacetate hydroxylase component B from T. thermophilus; NmoB is nitrilotriacetate monooxygenase component B from Chelatobacter heintzii; EmoB is NADH:FMN oxidoreductase from bacterium BNC1; HpaHKp is 4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-monooxygenase component B from Klebsiella pneumoniae; and PheB is phenol 2-monooxygenase component B from Geobacillus thermoglucosidasius.

The primary and tertiary structural comparison of the above-listed oxidoreductases of high similarity revealed that EmoB does not have the well known canonical flavodoxin motif. The motif, (T/S)XTGXT, is strongly conserved among classical flavodoxins and is located in the loop area connecting α1 and β1, which is involved in coordinating the phosphate group of FMN. EmoB uses loop 11SPSRNSTT18 at this same location. As reported recently for other FMN reductases and flavoproteins (34, 40), this area is not well conserved among the structurally related proteins (Fig. 8). However, despite a lack of sequence similarity, the backbone and side chains of the corresponding loop regions are all engaged in phosphate coordination in all of the proteins with available complex structures. In addition, Tyr80 and Pro78 of EmoB also coordinate the phosphate moiety, and these two residues are more conserved than the above-mentioned canonical flavodoxin motif. In addition, Gly111, Gly112, and Ser113 in EmoB are highly conserved among flavodoxins and related proteins, and the backbones of Gly112 and Ser113 are hydrogen-bonded to the N-1 and O-2 atoms of the isoalloxazine ring. Therefore, the canonical motif, (T/S)XT-GXT, might be unique to the classical flavodoxins, and the general peptide motifs for flavin binding should be revisited and must include Tyr80, Pro78, Gly111, Gly112, and Ser113.

The oligomeric structure of EmoB is also suggestive of its structural classification. Most of the NAD(P)H:FMN oxidoreductases and flavodoxin-related proteins with known structures exist in ether dimeric or monomeric forms. Especially all of the reported NAD(P)H:flavin oxidoreductases in the TC-FDM family (HpaCSt, HpaCTt, and PheA2) exist as dimers. However, both our crystal structure and MALLS data indicate that EmoB is a tetramer in solution, as is the case for some of the structurally related proteins, such as the flavin-binding protein from S. flexneri (Protein Data Bank code 2FZV), the flavoprotein from S. meliloti (code 2Q62), and the Trp repressor-binding protein from B. subtilis (code 1RLI). Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that these tetrameric flavoenzymes could constitute a unique branch in NAD(P)H:flavin oxidoreductases with EmoB. However, our MALLS analysis indicated that the apo-form of EmoB still maintains its tetrameric character, which is different from the FMN-dependent dimer-tetramer transition observed in other bacterial flavodoxin-like proteins, such as the Trp repressor-binding protein and azoreductase (41, 42). In all of these tetrameric enzymes, a typical dimer configuration among many FMN reductases is still maintained in their tetramer interface (e.g. the yellow/green or blue/red pair in Fig. 2B).

Active Site and Catalytic Mechanism—Our results provide detailed information about the mechanism by which EmoB performs its function. In EmoB, four equivalent redox sites are located near the tetramer interface. At each of these sites in the complex form of EmoB, either pairs of stacked FMN molecules or stacked FMN and NADH are observed. Like other tetrameric FMN reductases, such as the above-mentioned flavin-binding protein from S. flexneri (Protein Data Bank code 2FZV), the flavoprotein from S. meliloti (code 2Q62), and the Trp repressor-binding protein from B. subtilis (code 1RLI), the EmoB tetramer has a somewhat exposed entry site for the FMN(H2) and NAD(H) molecules. This is consistent with the fact that the apo-form and the complex form of EmoB do not show any significant structural differences. For example, the FMN-binding pocket of NAD(P)H:FMN oxidoreductase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (code 1T0I) has a very limited accessibility due to blockage by the extra residues between β2 and α2 (Fig. 8) contributed from the other subunit (43); thus, it is very unlikely to bind an FMN molecule in this dimeric enzyme without a substantial conformational change. Among NAD(P)H:flavin oxidoreductases and flavodoxin-like proteins (Figs. 7 and 8), the entry sites for the flavin molecule have differently sized and positioned secondary structural elements, probably dictating the substrate preference and activities for an individual class of enzymes.

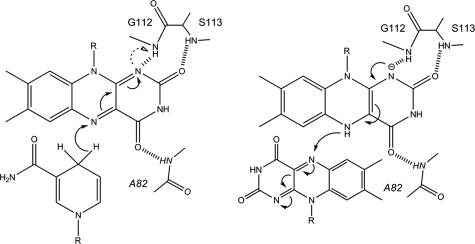

Our results provide essential information for determining the catalytic mechanism of EmoB. Especially the complex structure for two FMN molecules in their redox position has been established for the first time. In the FMN complex form of EmoB (oxidation state form), the two stacked FMN molecules are oriented in opposite directions (e.g. stacked through the si-faces of their isoalloxazine rings), making the distance between the N-5 atoms of the isoalloxazine rings 3.4 Å, which is a proper distance for hydride transfer (Fig. 4A). Compared with the one significant interaction (with Lys81) of the loosely bound second FMN molecule, the first FMN molecule has a tight interaction with the enzyme. The experimental results that (i) a riboflavin molecule is not visible in the riboflavin-soaked crystals, (ii) there is a very weak heat of binding for riboflavin in the ITC data, and (iii) the apo-form structure has a phosphate ion at the same location for the phosphate group of the first FMN reflect the importance of the phosphate group of FMN in its affinity. This is consistent with the crystal structure showing that the phosphate group of the first FMN forms a network of interactions with Ser11, Thr17, Thr18, and Tyr80 (Fig. 4C). In addition, the corresponding structure for the other half-redox reaction has been established. In our FMN·NADH complex form of EmoB (reduction state form), it is likely that the FMN molecules are in their reduced state, as judged by the pale yellow color of the soaked crystal in contrast to the intense yellow color of the FMN·FMN complex crystal. The stacked isoalloxazine and nicotinamide rings are also properly oriented at a distance of 3.5 Å between C-4 of NAD(H) and N-5 of FMN(H2).

Compared with the loosely bound second FMN molecule of the FMN·FMN complex, the NAD(H) molecule has more interactions with the enzyme (with Lys81 and Gly112) and the first FMN, indicating its higher affinity. This matched well with the observation that the crystal soaked with both FMN and NADH has FMN(H2)·NAD(H) molecules instead of two FMN molecules in the binding sites. However, the NAD(H) molecule by itself has very weak affinity, as indicated by the ITC results and the lack of NADH density in the soaked crystal with riboflavin and NADH. Therefore, an affinity of NADH for EmoB exists only after the first FMN occupies its site.

The complex structures of EmoB also suggest its potential catalytic mechanism. Significantly, the N-1 atom of the isoalloxazine ring of the first FMN is within hydrogen bond distance of the backbone amide nitrogen of Gly112, which could serve as a general acid/base catalyst for protonation/deprotonation of the N-1 atom or as an electrostatic catalyst stabilizing the semiquinone form of FMN (Fig. 10). In addition, in the crystal structures for both the reduction and oxidation states, the second isoalloxazine ring and nicotinamide ring are well covered by Gln97 of the neighboring subunits (Fig. 4), probably shielding the N-5 atom of isoalloxazine and the C-4 atom of nicotinamide from bulk solvent. This shielding role of Gln97 is comparable with that of the adenine ring of the compactly folded NAD(P)+, which is observed in a stacked position on top of the nicotinamide ring in both the HpaC and PheA2 structures (27). The NAD(H) molecule in the FMN·NADH complex form of EmoB does not show such a defined conformation; instead, the corresponding adenosine is disordered. In addition, a stacked conformation of the adenosine is not possible in the EmoB tetramer due to a potential collision with the above-mentioned Gln97 side chain.

FIGURE 10.

Proposed hydride transfer reaction in the active site of EmoB. Left, reduction process of the first FMN by the stacked NADH; right, oxidation process of the bound reduced FMN by the second FMN. The backbone amide nitrogen atom of Gly112 is within hydrogen bond distance (2.8 Å), which can either stabilize the negative charge of the semiquinone form or provide a proton to it. The arrows indicate the movement of an electron. The figures were made using ChemBioDraw Ultra 11.0 (Cambridge Corp.).

Summary—The structure of EmoB is similar to that of flavodoxin, which is an electron transfer protein containing FMN as a cofactor and which requires a partner protein, flavodoxin reductase, for its reducing power. However, EmoB is an NAD-(P)H:flavin oxidoreductase, which does not require any other protein for its reduction. Our structural data provide a complete picture of both the oxidation and reduction reactions for this NAD(P)H:flavin oxidoreductase. The first FMN molecule is relatively tightly bound to EmoB with a Kd of 0.42 μm. This affinity should allow the first FMN to remain bound to EmoB under our kinetic assay conditions with FMN concentrations higher than the Km (1.7 μm). Therefore, the first FMN is acting as a cofactor. The crystal structure of the FMN·FMN complex of EmoB provides the first direct observation for two FMN molecules stacked in opposite directions, making a proper distance for hydride transfer. The first FMN molecule is tightly bound through several hydrogen bonds in a shallow pocket, and its N-1 atom of the isoalloxazine ring is hydrogen-bonded to Gly112, which potentially catalyzes the hydride transfer reaction. The second FMN is loosely bound, and its N-5 atom is somewhat protected from the solvent due to the oligomeric nature of EmoB. The NAD(H) molecule has a slightly stronger affinity for the enzyme than the second FMN molecule, but is much weaker than the first FMN molecule. Our data suggest that the NADH:FMN oxidoreductase activity of EmoB is through the reduction of a loosely associated (i.e. diffusible) FMN molecule by a tightly bound FMN molecule, which is reduced in turn by an NADH molecule. On the basis of the clear results from the double-reciprocal plot, we unequivocally propose a Ping Pong Bi Bi mechanism for the production of FMNH2 by EmoB (Fig. 6). In the first step of the catalytic cycle, a reductive half-reaction, NADH reduces the tightly associated FMN, and NAD+ leaves EmoB. The next oxidative half-reaction step is the association and concomitant reduction of a second, diffusible FMN molecule. The diffusible FMNH2 is then used by EmoA for EDTA metabolism. In this two-step process, the NADH molecule delivers its hydride through transiently stacked interactions of its nicotine amide ring with the isoalloxazine ring of FMN, as similarly observed in the binary complex structures of PheA2 and HpaC (26). However, the tertiary and quaternary structures and the shielding mechanism for the redox sites of EmoB are quite different from those of PheA2 and HpaC, possibly indicating the existence of another subgroup of NADH:FMN oxidoreductases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Ralston (Berkeley Advanced Light Source, beam line 8.2.1) and K. S. Lam (Washington State University).

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 2VZF, 2VZH, and 2VZJ) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

The work was supported in part by National Research Initiative Grant 2006-35318-17452 from the United States Department of Agriculture Cooperative State Research, Education, and Extension Service, Grant DE-FG02-05ER63974 from the Environmental Remediation Sciences Division Program of the Office of Biological and Environmental Research of the Department of Energy, and American Heart Association Grant 0850084Z. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains a supplemental figure.

This article was selected as a Paper of the Week.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: TC-FDM, two-component flavin-diffusible monooxygenase; MALLS, multiangle laser light scattering; ITC, isothermal titration calorimetry; MES, 4-morpholineethanesulfonic acid; MAD, multi-wavelength anomalous diffraction.

References

- 1.Barber, L. B., II, Leenheer, J. A., Pereira, W. E., Noyes, T. I., Brown, G. K., Tabor, C. F., and Writer, J. H. (1995) in Organic Contamination of the Mississippi River from Municipal and Industrial Wastewater (Meade, R. H., ed) U. S. Geological Survey Circular 1133, pp. 115-135, Reston, VA

- 2.Bucheli-Witschel, M., and Egli, T. (2001) FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 25 69-106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toste, A., Osborn, B., Polach, K., and Lechner-Fish, T. (1995) J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 194 25-34 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dirilgen, N. (1998) Chemosphere 37 771-783 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sillanpaa, M., and Oikari, A. (1996) Chemosphere 32 1485-1497 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bohuslavek, J., Payne, J., Liu, Y., Bolton, H. J., and Xun, L. (2001) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67 688-695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Means, J., and Crerar, D. (1978) Science 200 1477-1486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cleveland, J., and Rees, T. (1981) Science 212 1506-1509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang, H. Y., Chen, S. C., and Chen, S. L. (2003) Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 111 81-92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lauff, J., Steele, D., Coogan, L., and Breitfeller, J. (1990) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56 3346-3353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nortemann, B. (1999) Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 51 751-759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Witschel, M., Nagel, S., and Egli, T. (1997) J. Bacteriol. 179 6937-6943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weilenmann, H. U., Engeli, B., Bucheli-Witschel, M., and Egli, T. (2004) Biodegradation 15 289-301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu, Y., Louie, T., Payne, J., Bohuslavek, J., Bolton, H. J., and Xun, L. (2001) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67 696-701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hastings, J., and Balny, C. (1975) J. Biol. Chem. 250 7288-7293 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thibaut, D., Ratet, N., Bisch, D., Faucher, D., Debussche, L., and Blanche, F. (1995) J. Bacteriol. 177 5199-5205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gray, K., Pogrebinski, O., Mrachko, G., Xi, L., Monticello, D., and Squires, C. (1996) Nat. Biotechnol. 14 1705-1709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahnert, A., Vermeij, P., Wietek, C., James, P., Leisinger, T., and Kertesz, M. (2000) J. Bacteriol. 182 2869-2878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xun, L., and Sandvik, E. (2000) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66 481-486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Louie, T., Xie, X., and Xun, L. (2003) Biochemistry 42 7509-7517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gisi, M., and Xun, L. (2003) J. Bacteriol. 185 2786-2792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Otto, K., Hofstertter, K., Röthlisberger, M., Witholt, B., and Schmid, A. (2004) J. Bacteriol. 186 5292-5302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Filisetti, L., Fontecave, M., and Nivière, V. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 296-303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao, B., and Ellis, H. (2005) Biochim. Biophys. Res. Commun. 331 1137-1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim, S., Hisano, T., Iwasaki, W., Ebihara, A., and Miki, K. (2008) Proteins 70 718-730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van den Heuvel, R., Westphal, A., Heck, A., Walsh, M., Rovida, S., van Berkel, W., and Mattevi, A. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 12860-12867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okai, M., Kudo, N., Lee, W., Kamo, M., Nagata, K., and Tanokura, M. (2006) Biochemistry 45 5103-5110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Youn, B., Moinuddin, S., Davin, L., Lewis, N., and Kang, C. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 12917-12926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Otwinowski, Z., and Minor, W. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 276 307-326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hendrickson, W. (1991) Science 254 51-58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Terwilliger, T., and Berendzen, J. (1999) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 55 849-861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Terwilliger, T. (2001) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 57 1755-1762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones, T., Zou, J., Cowan, S., and Kjeldgaard, M. (1991) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 47 110-119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brunger, A., Adams, P., Clore, G., DeLano, W., Gros, P., Grosse-Kunstleve, R., Jiang, J., Kuszewski, J., Nilges, M., Pannu, N., Read, R., Rice, L., Simonson, T., and Warren, G. (1998) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54 905-921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lopez-Llano, J., Maldonado, S., Jain, S., Lostao, A., Godoy-Ruiz, R., Sanchez-Ruiz, J., Cortijo, M., Fernandez-Recio, J., and Sancho, J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 47184-47191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lesk, A., Brändén, C., and Chothia, C. (1989) Proteins 5 139-148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roldán, M., Pérez-Reinado, E., Castillo, F., and Moreno-Vivián, C. (2008) FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32 474-500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holm, L., and Sander, C. (1993) J. Mol. Biol. 233 123-138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Altschul, S., Madden, T., Schaffer, A., Zhang, J., Zhang, Z., Miller, W., and Lipman, D. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res. 25 3389-3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Agarwal, R., Bonanno, J., Burley, S., and Swaminathan, S. (2006) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62 383-391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen, H., Hopper, S., and Cerniglia, C. (2005) Microbiology (Read.) 151 1433-1441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Natalello, A., Doglia, S., Carey, J., and Grandori, R. (2007) Biochemistry 46 543-553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liger, D., Graille, M., Zhou, C., Leulliot, N., Quevillon-Cheruel, S., Blondeau, K., Janin, J., and van Tilbeurgh, H. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 34890-34897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.