Abstract

The pre-activation based chemoselective glycosylation is a powerful strategy for oligosaccharide synthesis with its successful application in assemblies of many complex oligosaccharides. However, difficulties were encountered in reactions where glycosyl donors bearing multiple electron withdrawing groups failed to glycosylate hindered unreactive acceptors. In order to overcome this problem, it was discovered that the introduction of electron donating protective groups onto the glycosyl donors can considerably enhance their glycosylating power, leading to productive glycosylations even with unreactive acceptors. This observation is quite general, which can be extended to a wide range of glycosylation reactions, including one-pot syntheses of chondroitin and heparin trisaccharides. The structures of the reactive intermediates formed upon pre-activation were determined through low temperature NMR studies. It was found that for a donor with multiple electron withdrawing groups, the glycosyl triflate was formed following pre-activation, while the dioxalenium ion was the major intermediate with a donor bearing electron donating protective groups. As donors were all cleanly pre-activated prior to the addition of the acceptors, the observed reactivity difference between these donors was not due to selective activation encountered in the traditional armed-disarmed strategy. Rather, it was rationalized by the inherent internal energy difference between the reactive intermediates and associated oxacarbenium ion like transition states during nucleophilic attack by the acceptor.

Introduction

With the increasing recognition of the important biological functions of carbohydrates, carbohydrate synthesis is a very active research area with many innovative methodologies developed during the past two decades.2–5 In most glycosylation reactions, a promoter is added to a mixture of the glycosyl donor and the acceptor. The glycosyl donor is activated by the promoter, which undergoes in situ nucleophilic addition or displacement reaction with the acceptor leading to the glycoside product. As an alternative, a glycosyl donor can be activated in the absence of an acceptor (pre-activation).6–18 Upon complete donor activation, the acceptor is then added to the reaction mixture initiating glycoside formation. Using the pre-activation strategy, unique stereochemical outcomes6,9,16,17 and chemoselectivities10–13,15 can be obtained. Boons and coworkers developed a novel α selective glycosylation strategy,9 where pre-activation of a trichloroacetimidate donor allowed for the 2-O protective group to participate and stabilize the oxacarbenium ion from the β face. Thus, SN2 like displacement by the acceptor gave α glycosides highly selectively. The Crich group discovered that pre-activation of a benzylidene protected thiomannoside or mannosyl sulfoxide generated an α-mannosyl triflate,17 which upon triflate displacement by an acceptor led to the β-mannoside stereoselectively overcoming this long–standing challenge. Gin and coworkers reported that the pre-activated hemiacetal donor could chemoselectively glycosylate a hemiacetal acceptor.15 The glycoside product could then be directly activated using the identical condition and glycosylation can be carried out iteratively.

Recently, we7,8,11,19–22 and others12,13,23 applied the pre-activation scheme to the chemoselective glycosylation of a thioglycoside acceptor by a thioglycosyl donor. In this approach, the glycosyl donor is pre-activated by a stoichiometric promoter. Upon complete donor activation, a thioglycosyl acceptor is added to the reaction mixture. Nucleophilic attack on the activated donor by the acceptor yields a disaccharide product containing a thioether aglycon, which can be directly activated for the next round of glycosylation without any aglycon adjustment as typically required by other selective activation strategies. With the pre-activation scheme, because donor activation and addition of the acceptor are performed in two distinct steps, the anomeric reactivity of the thioglycosyl donor is independent of that of the thioglycosyl acceptor. This confers much freedom in protective group selection, greatly simplifying the overall synthetic design. This is in contrast with the traditional reactivity based armed-disarmed chemoselective glycosylation method,24–26 where the glycosyl donor must possess much higher anomeric reactivity (typically at least ten times higher) than the glycosyl acceptor,24 as the donor is activated in the presence of the acceptor.

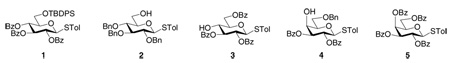

A wide range of thioglycosyl donor and acceptor pairs have been examined using the pre-activation protocol.7,8,11,12,19–23 In many cases, the chemoselective glycosylation reactions proceeded smoothly with good yields. It is particularly noteworthy that a disarmed donor (e.g. 1) can glycosylate an armed acceptor (e.g. 2).11,20 This reversal of anomeric reactivity is not possible using the reactivity based armed-disarmed method.24,25 The pre-activation based strategy has been successfully applied to total synthesis of a wide range of complex linear and branched oligosaccharides, including LewisX,21 dimeric LewisX,21 Globo-H,20 hyaluronic acid oligosaccharides,8 chito-oligosaccharides13,22 and complex type sialylated core fucosylated N-glycan dodecasaccharide.7 However, difficulties were encountered in reactions of very unreactive secondary carbohydrate acceptors such as 3 and 4 with electron poor donors 1 and 5.11 In this article, we will explore a strategy to overcome this problem. We will also study the intermediates generated upon pre-activation to provide insights to design even better glycosylation strategies.

Results and discussion

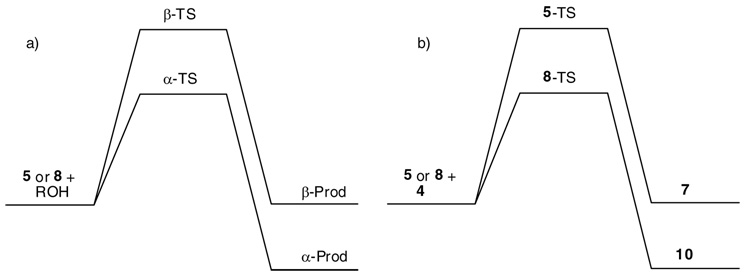

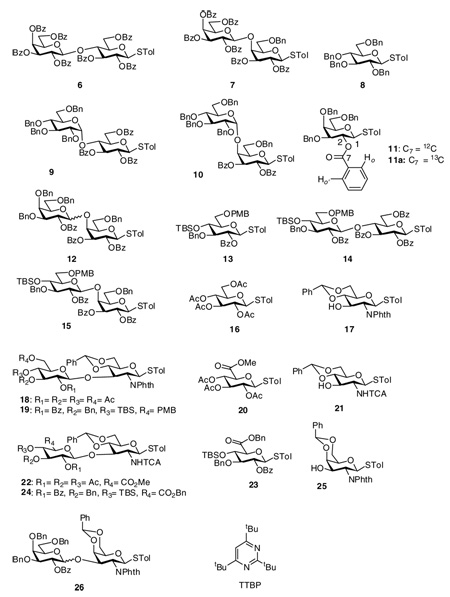

The reaction of donor 5 with acceptor 3 was performed by first pre-activating donor 5 with the promoter system p-TolSCl/AgOTf11 followed by addition of acceptor 3 and a sterically hindered base tri-t-butyl pyrimidine (TTBP)27 (Table 1, entry 1). Although no desired disaccharide was formed, complete disappearance of the donor was observed by TLC and NMR (vide infra). Analysis of the reaction mixture showed that donor 5 was converted to the expected breakdown products (the hemiacetal or the glycal) of the oxacarbenium ion corresponding to 5, with most of the acceptor 3 recovered. This demonstrated that despite the presence of multiple electron withdrawing benzoyl groups, the electron poor donor 5 was activated by the powerful promoter p-TolSCl/AgOTf. Similar phenomena were observed in the reaction of 4 with 5 (Table 1, entry 2) or donor 1.11 Interestingly, reaction of perbenzylated glucose donor 8 with acceptors 3 and 4 gave the corresponding disaccharides 9 and 10 smoothly in good yields following the identical reaction protocol (Table 1, entries 3,4).11 The contrasting outcome in these glycosylations using the same acceptor can be due to two possible factors: 1) with donor 8, α-glycoside product is pre-dominantly formed while donor 5 would favor the β-product due to neighboring group participation; and 2) electronic properties of the two glycosyl donors are quite different with donor 8 bearing multiple electron donating protective groups and donor 5 containing electron withdrawing protective groups only. These two factors correspond to an inherent α/β facial selectivity at the TS for 5 and 8 (Figure 1a) or an inherently lower transition state (TS) energy in reaction coordinates of 8 versus 5 (Figure 1b).

Table 1.

Glycosylation results of various donor/acceptor pairs

| Entry # | Donor | Acceptor | Product | Yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 3 | 6 | < 10% |

| 2 | 5 | 4 | 7 | < 10% |

| 3 | 8 | 3 | 9 | 67% |

| 4 | 8 | 4 | 10 | 65% |

| 5 | 11 | 4 | 12 | 56% (48% β + 8% α) |

| 6 | 13 | 3 | 14 | 74% |

| 7 | 13 | 4 | 15 | 70% |

| 8 | 16 | 17 | 18 | < 10% |

| 9 | 13 | 17 | 19 | 75% |

| 10 | 20 | 21 | 22 | < 10% |

| 11 | 23 | 21 | 24 | 73% |

| 12 | 11 | 25 | 26 | 65% (51% β + 14% α) |

Figure 1.

Schematic demonstrations of a) inherent α/β facial selectivity at the TS for 5 and 8 glycosylations with an acceptor; and b) TS energy difference in reaction coordinates of donor 8 versus 5.

To better differentiate the factors governing the glycosylation, donor 1120 was prepared, which bears multiple electron donating groups and a participating protective group at O-2. After pre-activation by p-TolSCl/AgOTf, donor 11 successfully glycosylated acceptor 4 producing disaccharide 12β in 48% yield (Table 1, entry 5), suggesting that facial selectivity is not the dominating factor for determining the donor’s ability to react with 4. The identity of the sugar is not crucial as the electron rich glucoside donor 138 also smoothly glycosylated acceptors 3 and 4 to give disaccharides 14 and 15 (Table 1, entries 6,7). Thus, the observed dichotomy in reaction outcome must be resulting from different electronic properties of the glycosyl donors. To glycosylate unreactive acceptors, donors containing more electron donating groups are preferred as they inherently possess higher glycosylating activity following the reaction scheme of Figure 1b.

This observation turns out to be quite general and can be extended to a wide range of reactions, which are synthetically useful. Per-acylated thioglucoside 16 failed to react with glucosamine 17. Replacement of its 3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl groups with electron donating silyl and ether protective groups (donor 13) renders it an effective donor to glycosylate 17 producing disaccharide 19 (Table 1, entry 9).8 Glucuronic acid residues exist in many naturally occurring oligosaccharides. However, due to the presence of the electron withdrawing carboxylic acid, glucuronic acid thioglycoside derivatives have been rarely used as glycosyl donors.28–31 Instead, thioglucosides are typically employed, which require oxidation state adjustment after the glycosylation.28,32 It will be desirable to be able to use protected glucuronic acid derivatives directly as glycosyl donors. However, the electron poor glucuronic acid donor 20 did not undergo glycosylation with acceptor 21 at all. This problem was solved by using its electron rich counterpart 23, which gave hyaluronic acid precursor disaccharide 24 in 73% yield (Table 1, entry 11). The electron rich thiogalactoside donor 11 also glycosylated the sterically hindered acceptor 25 in good yield (Table 1, entry 12).

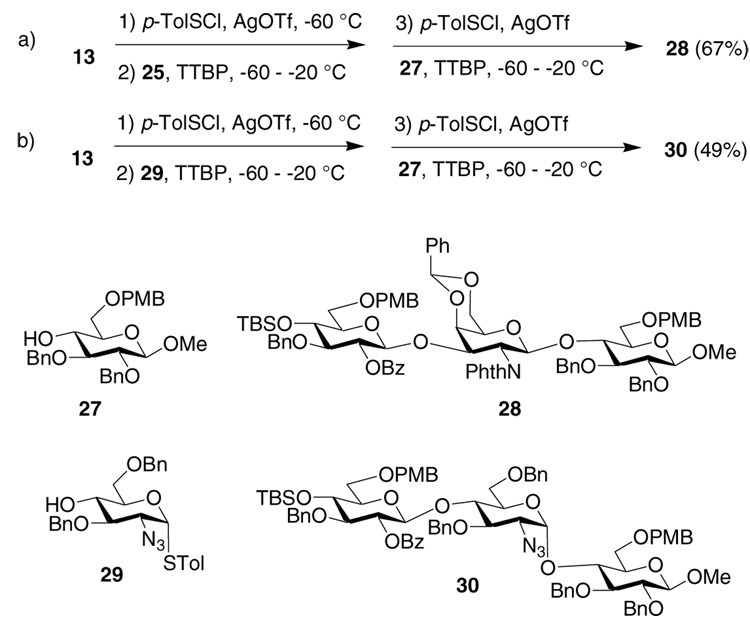

There are high interests in acquiring glycosaminoglycans, such as chondroitin and heparin due to their important biological functions.33–38 Heparin synthesis requires glycosylation of the 4-OH of a glucosamine acceptor, which is known to be notoriously unreactive.39 A similar challenge is also present for chondroitin preparation as the 3-hydroxyl group of most galactosamine acceptors is sterically hindered. We envision that the high glycosylating power of donor 13 bestowed by the electron donating protective groups can overcome the low reactivities of glucosamine and galactosamine acceptors. Moreover, we want to examine whether these syntheses can be performed in a one-pot fashion.

Pre-activation of donor 13 by p-TolSCl/AgOTf at −60 °C was followed by the addition of acceptor 25 (Scheme 1a). Upon complete consumption of the acceptor, a second acceptor 2740 and another equivalent of the promoter p-TolSCl/AgOTf were added to the same reaction flask. Chondroitin precursor trisaccharide 28 was successfully produced from this three-component one-pot synthesis in 67% overall yield within just five hours. A heparin precursor trisaccharide 30 was prepared in a similar manner through sequential reactions of 13, 2941 and 27 in one-pot in 49% yield (Scheme 1b).

Scheme 1.

Why do the more electron rich donors have higher glycosylating power? To answer this question, the reactive intermediates formed following pre-activation were examined. In general, it is a difficult task to thoroughly characterize the reactive intermediates due to their limited lifetime especially when donor activation is carried out in the presence of an acceptor. With the pre-activation scheme, because the activation and glycosylation are two distinct steps, it will be possible to observe the intermediates at low temperature following pre-activation.

Recently, low temperature NMR has been shown to be a powerful tool to monitor the glycosylation process.9,14,42–47 Crich and colleagues have carried out ground breaking work in studying the reactive intermediates of a glycosylation reaction.47 They demonstrated that in the absence of neighboring group participation, glycosyl triflates, which have characteristic 1H-, 13C-, and 19F- NMR profiles, were the dominant intermediates when several thiophenyl mannosylpyranosides and thiophenyl glucosylpyranosides were pre-activated by PhSOTf at low temperatures. The identification of glycosyl triflate was used to rationalize the high β-selectivity in glycosylation of benzylidene protected mannothiopyranosides. Lowary and coworkers showed that in activation of a furanosyl sulfoxide, although multiple intermediates existed at −60 °C, glycosyl triflate was the dominant one when the reaction was warmed up to −40 °C. This observation enabled them to modify the operations and enhance the yield and stereoselectivity of their synthesis.14

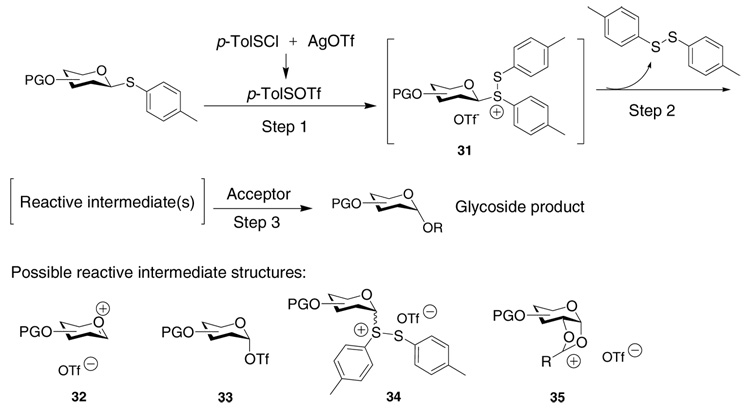

In our glycosylation reaction, upon addition of p-TolSCl to a mixture of p-tolylthioglycoside donor and AgOTf, p-TolSOTf is formed, which electrophilically attacks the anomeric sulfur atom of the donor to generate disulfonium ion 31 (step 1, Scheme 2). The disulfonium ion 31 can further evolve to several possible intermediates prior to the addition of the nucleophilic acceptor (step 2): 1) oxacarbenium ion pair 32; 2) glycosyl triflate 33 by addition of the triflate anion to the anomeric center; 3) disulfonium ion 34 formed by equilibrating with the p-tolyl disulfide side product; and 4) dioxalenium ion 35 in the cases where the donor contains an O-2 acyl participating protective group. Nucleophilic attack of the reactive intermediate(s) by the acceptor will then generate the glycoside product (step 3). Although drawn as free ion pairs, 32, 34 and 35 can also possibly exist as either solvent separated ion pairs or contact ion pairs.

Scheme 2.

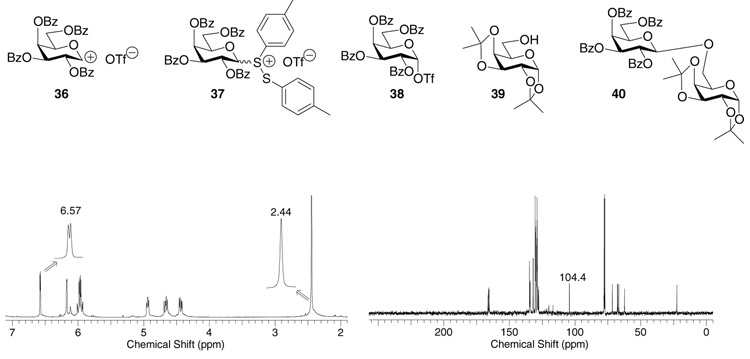

Because the intermediates upon activation of glycosyl donors without 2-O participating neighboring groups have been quite extensively studied,14,17,47–49 we focused on donors containing O-2 acyl groups in this study. The pre-activation of per-O-benzoylated galactose donor 5 was monitored first by NMR. No significant differences in product yields or NMR spectra were observed when the reactions were performed in CD2Cl2, CDCl3, CD2Cl2: Et2O-D10 (1:1) or CDCl3: Et2O-D10 (1:1). Therefore, all subsequent studies were performed in anhydrous CDCl3. Addition of p-TolSCl to a mixture of donor 5 and AgOTf at −60 °C led to rapid dissipation of the characteristic yellow color of p-TolSCl within seconds. Inspection of the 1H-NMR spectrum revealed that the donor was transformed within a few minutes to one major new carbohydrate species characterized by its anomeric proton signal, a doublet at δ 6.57 ppm with J1,2 = 3.2 Hz (Figure 2). No signals around δ 9.5 ppm due to the anomeric proton of the possible oxacarbenium ion 36 were observed.50

Figure 2.

1H-NMR and 13C-NMR spectra of the intermediate formed after pre-activation of donor 5 in CDCl3 at −60 °C.

The methyl group of the p-tolyl moiety after pre-activation appeared as a singlet in its 1H-NMR spectrum, which was the case for all p-tolyl thioglycosides examined. If the glycosyl disulfonium ion 37 were formed, the two p-TolS groups would have become non-equivalent leading to two separate methyl peaks in 1H-NMR. This was supported by the fact that the 1H-NMR of dimethyl(methylthio)sulfonium triflate (DMTST) exhibits two singlets at 3.27 ppm and 2.92 ppm with the integration ratio of 2:1.51 Furthermore, in glycosylation of 2 by 8, addition of exogenous p-tolyl disulfide to the reaction did not cause significant changes in either reaction yield or stereoselectivity (data not shown). Thus, the glycosyl disulfonium ion does not play a significant role in the thioglycoside glycosylation but rather a transient function on route to other species.

The 13C-NMR spectrum of the activated intermediate from donor 5 at −60 °C corroborated the clean formation of a new carbohydrate species with its anomeric carbon signal resonating at δ 104.4 ppm and four carbonyl carbon signals at δ 166.4, 165.9, 165.8, 165.5 ppm (Figure 2). The chemical shift of the anomeric carbon also excluded the possibility of oxacarbenium ion 36 as the positively charged anomeric carbon in the oxacarbenium ion was expected to appear above 210 ppm47 through analogy with other sp2 hybridized alkoxy carbenium ions.50,52,53 By electrochemical oxidation, Crich, Yoshida and coworkers generated a series of glycosyl triflates for glucosides, galactosides and mannosides without participating neighboring groups on O-2. The anomeric protons of these glycosyl triflates appeared around 6.2 ppm and anomeric carbons around 106 ppm.42 Our NMR data is consistent with the intermediate structure following pre-activation of 5 being the α-glycosyl triflate 38. Prior to the activation, the 19F-NMR spectrum showed a single peak at δ-4.2 ppm due to the triflate anion from AgOTf. The corresponding 19F-NMR after activation revealed two signals, δ-1.2 and δ-4.2 ppm assigned to glycosyl triflate 38 and excess AgOTf, respectively. The glycosyl triflate 38 was found to be quite stable because no significant changes were observed by NMR when the temperature was raised to −20 °C. The triflate 38 was a competent glycosyl donor with reactive acceptors as the addition of the primary galactoside acceptor 39 to the NMR tube led to the desired disaccharide 40 cleanly. Yet, adding the unreactive acceptor 3 to 38 did not produce any disaccharide 6. This is consistent with a model that some nucleophilic push is required in order to activate anomeric triflates.

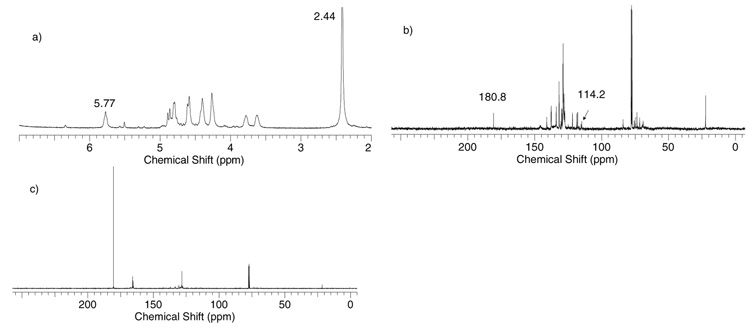

When the more electron rich donor 11 was pre-activated by p-TolSCl/AgOTf, one major intermediate was formed along with several minor ones. The 1H-NMR of activated donor 11 was considerably broader than that of activated donor 5, presumably due to residual silver cation complexation with aromatic residues54 possibly the benzyl protecting groups of 11 (Figure 3). A gCOSY correlation experiment showed that the anomeric proton of the major intermediate has undergone significant downfield shift from 4.98 ppm in donor 11 to 7.34 ppm, while H-2 shifted slightly to 5.77 ppm (Figure S1). To better probe this intermediate by 13C-NMR, a 13C-labeled benzoyl group was introduced onto O-2 of the galactoside (donor 11a), which showed a chemical shift of 165.5 ppm by 13C-NMR. An HMBC spectrum of the 13C labeled donor 11a displayed correlations between the 13C 165.5 ppm peak and protons at 8.02 ppm (Ho, Ho’ protons of the Bz phenyl ring) and 5.66 ppm (H-2) with no correlations with the anomeric proton at 4.98 ppm (Figure S2a). Upon activation, a strong new resonance at δ 180.8 ppm appeared in the 13C-NMR with the concomitant decrease of the resonance at δ 165.5 ppm (Figure 3c). For this new carbon signal, in addition to its HMBC correlations with 1H-NMR signals at 8.02 ppm (Ho, Ho’) and 5.77 ppm (H-2), a new correlation with the H-1 proton signal at 7.34 ppm was observed (Figure S2b). These correlations strongly suggest the bridging dioxalenium ion 41 formed through participation by the neighboring O-2 benzoyl group. The chemical shift of 180.8 ppm for the bridging carbon in 41 was similar to the value of 180.3 ppm observed for the dioxalenium ion 42 formed from xyloside 43.55 The HSQC spectrum of 41 indicated that the anomeric carbon was also downfield shifted to 114.2 ppm (Figure S3). The positive charge of the dioxalenium ion 41 could be distributed over O-5, C-1, O-1 and C-7, explaining the significant downfield shift of H-1, C-1 and C-7. By quantum mechanical calculation the LUMO of dioxalenium ions has been shown to be a vacant p-like orbital centered on C-7 in agreement with these observations.56 Compared with the glycosyl triflate 38, the dioxalenium ion 41 was less stable with decomposition setting in when the temperature was raised to above −30 °C.

Figure 3.

a) 1H-NMR and b) 13C-NMR spectra of the intermediates formed after pre-activation of donor 11 and c) 13C-NMR after pre-activation of donor 11a in CDCl3 at −60 °C.

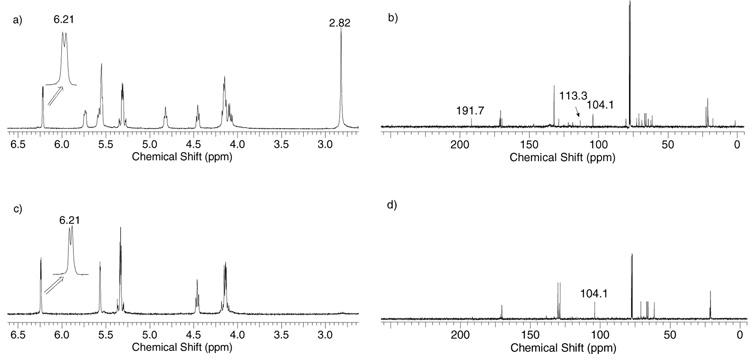

Interestingly, pre-activation of the tetra-O-acetyl glucose 16 converted it into two reactive intermediates in roughly 1:1 ratio at −60 °C (Figure 4a,b). Based on the resonances at δ 6.21 ppm (J1,2 = 2.4 Hz) and δ 104.1 ppm of the anomeric proton and carbon atoms, the first intermediate was assigned to be the α-glycosyl triflate 44. The second intermediate has 13C-NMR resonances at δ 191.7, 113.3 ppm for C-7 and C-1, and 1H-NMR resonances at δ 7.35 and 2.82 ppm for H-1 and H-8 of the dioxalenium ion 45. The glycosyl triflate 44 and dioxalenium ion 45 were shown to interconvert by warming the mixture to −20 °C, which led to the disappearance of 45 (Figure 4c,d) with it reappearing upon re-cooling to −60 °C. Addition of the primary galactoside acceptor 39 to the pre-activated donor 16 at −60 °C generated disaccharide 46 in 85% yield with both the glycosyl triflate 44 and the dioxalenium ion 45 consumed at comparable rates.

Figure 4.

a) 1H-NMR and b) 13C-NMR spectra of the intermediates formed after pre-activation of donor 16 in CDCl3 at −60 °C; c) 1H-NMR and d) 13C-NMR spectra after warming to −20 °C.

Why do donors 5, 11 and 16 form different intermediates following pre-activation? This can be explained by the fact that there are more electron withdrawing protecting groups (Bz is more deactivating than Ac) on the glycan ring of donors 5, which greatly disfavor the formation of positively charged dioxalenium ions. On the other hand, the presence of multiple electron donating benzyl groups on 41 stabilizes the positive charge sufficiently, rendering it unnecessary for the covalent attachment of the poor nucleophile triflate anion. The tetraacetyl glucoside 16 presents the intermediate case between donors 5 and 11, leading to a mixture of glycosyl triflate and dioxalenium ion upon pre-activation. Crich and coworkers reported the dioxalenium ion 42 as the major intermediate when they activated the per-benzoylated thioxyloside 43.55 As xylose is a pentose, it contains one fewer highly electron withdrawing group on the sugar ring,57,58 which is likely the reason why the dioxalenium ion 42 was formed as the major intermediate.

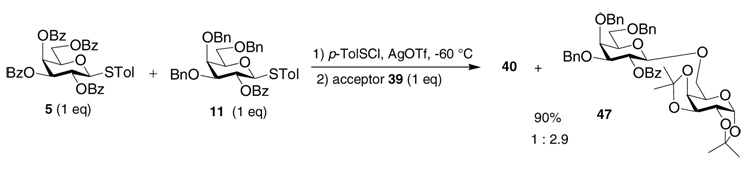

It is known that donor 11 is more reactive than donor 5 towards a thiophilic promoter.24 Wong and coworkers quantified relative reactivity values of a wide range of thiotolyl donors by having two different donors competing with a limiting amount of promoter in the presence of excess acceptor. Donor 11 was found to react with a promoter about 800 times faster than donor 5,24 which mostly reflected the internal free energy difference between the reactants and the activated intermediate (steps 1 and 2 for the glycosylation process). In contrast, pre-activation of a mixture of donors 11 and 5 completely converted both donors into reactive intermediates, thus removing the rate difference in reaction with the promoter. Upon addition of 1 eq of galactoside 39 to a pre-activated mixture of 1 eq of donor 5 and 1 eq of donor 11 at −60 °C, disaccharide 40 and 47 were isolated in a 1 : 2.9 ratio with a combined yield of 90% based on the amount of the acceptor added, suggesting the activated intermediates from donor 11 were 2.9 times more reactive than that from donor 5 (Scheme 3). When the reactivity of the acceptor decreased, the reaction became more selective as donor 5 failed to glycosylate acceptor 4 while donor 11 gave disaccharide 12 in 56% yield. Since the glycosyl triflate 38 is more stable than the dioxalenium ion 41, the different glycosylation outcome using donors 5 and 11 is not due to decomposition of the activated intermediate. The higher reactivity of dioxalenium ion 41 can be resulting from the lower free energy difference between 41 and the corresponding oxacarbenium ion like TS during nucleophilic attack of the acceptor (step 3) due to the higher electron density of the glycan ring and better stabilization of the TS. At the mean time, anomeric triflates may require some additional activation, which is dependent on the electron donating potential of the protecting groups of the donor. Possible mild activators include residual Ag+ ions or the protonated base. In the absence of such promoters the reaction temperature needs to be raised to activate the anomeric triflates towards unreactive acceptors.

Scheme 3.

Competitive glycosylation of acceptor 39 by a mixture of donors 5 and 11.

A TS connecting the dioxalenium ion derived from the reaction of methanol with 2-O-acetyl-3,4,6-tri-O-methyl-D-glucopyranosyl oxacarbenium ion has been found by quantum mechanical calculations.59 This TS is only 12.9 kJ mol−1 above the complex between methanol and the dioxalenium ion and is initiated by C-2—O-2 bond rotation. The ease of C-2—O-2 bond rotation is expected to depend on the protecting groups of the donor. This TS is also stabilized by intramolecular H-bonding from the hydroxylic proton to electronegative oxygens of the donor. Such H-bonding is reasonably expected to be sensitive to the steric accessibility of the hydroxyl and the electronegativity of the donor's H-bonding acceptor oxygen. It was further postulated that in the absence of intramolecular H-bonding, species like the counterions such as triflate or others such as added bases, molecular sieves etc. could act as the proton acceptor.

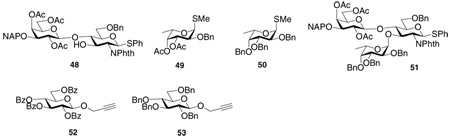

Although we primarily focused on the pre-activation strategy using thioglycosides, there have been reports that electron rich glycosyl donors possessing higher glycosylation power in other glycosylation protocols and other glycosyl building blocks.60–63 Matta and coworkers discovered that while fucosylation of the hindered disaccharide 48 failed with donor 49, mixing the more electron rich counterpart (donor 50) with 48 under the in situ anomerization protocol led to trisaccharide 51 in high yield.63 Similarly, substituting the electron withdrawing benzoyl groups on a per-O-benzoylated propargyl glycoside donor (donor 52) with benzyl groups (donor 53) transformed the failed glycosylation with donor 52 to one with 68% yield.62 Therefore, we propose that when a glycosylation reaction fails to yield the desired glycoside product, the installation of electron donating protective groups onto glycosyl donors can be explored in order to enhance the glycosylation yield. However, cautions need to be taken as the more electron rich donors turn to be less stable after activation, thus the usage of lower reaction temperature is preferred for this type of reactions.

Conclusions

We have investigated the intermediate structures following pre-activation of several representative thioglycosyl donors bearing 2-O acyl groups by low temperature NMR. It was found that glycosyl triflates were the major intermediates formed for donors bearing multiple electron withdrawing groups, while with the electron rich donors the dioxalenium ions were produced. We demonstrated that the introduction of electron donating groups onto glycosyl donors can overcome the low reactivities of glycosyl acceptors using the pre-activation protocol. This can be applied to one-pot synthesis leading to chondroitin and heparin trisaccharide precursors in high yields. It should be emphasized that the high reactivity bestowed by electron donating groups in our study is observed in the glycosylating step, rather than in the selective donor activation step encountered in the armed-disarmed strategy. The installation of electron donating protective groups onto glycosyl donors may be a general strategy to enhance the glycosylation yield, especially for difficult glycosylation reactions with unreactive acceptors.

Experimental Section

General procedure for single step pre-activation based glycosylation

A solution of donor (0.060 mmol), AgOTf (0.18 mmol) and freshly activated molecular sieve MS 4 Å (200 mg) in diethyl ether/CH2Cl2 (V : V = 2 : 2 mL), CH2Cl2 (3 mL) or CDCl3 (3 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 30 minutes, and cooled to −60 °C. After 5 minutes, orange colored p-TolSCl (9.5 µL, 0.060 mmol) was added through a microsyringe. Since the reaction temperature was lower than the freezing point of p-TolSCl, p-TolSCl was added directly into the reaction mixture to prevent it from freezing on the flask wall. The characteristic yellow color of p-TolSCl in the reaction solution dissipated rapidly within a few seconds indicating depletion of p-TolSCl. After the donor was completely consumed according to TLC analysis (less than 5 minutes at −60 °C), a solution of acceptor (0.054 mmol) and TTBP (1 eq) in CH2Cl2 (0.2 mL) was slowly added dropwise via a syringe. The reaction mixture was warmed to −20 °C under stirring in 2 hours. Then the mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (20 mL) and filtered over Celite. The Celite was further washed with CH2Cl2 until no organic compounds were observed in the filtrate by TLC. All CH2Cl2 solutions were combined and washed twice with saturated aqueous solution of NaHCO3 (20 mL) and twice with water (10 mL). The organic layer was collected and dried over Na2SO4. After removal of the solvent, the desired disaccharide was purified from the reaction mixture via silica gel flash chromatography.

General procedure for monitoring pre-activation by NMR

Reactions were carried out in NMR tubes with anhydrous CDCl3 at −60 °C. The donor (1.0 eq) and AgOTf (3.0 eq) were added to an NMR tube and dried in vacuo for 3 hours. CDCl3 (0.75 mL) was added slowly at −60 °C. Then the donor was pre-activated by the addition of p-TolSCl (1.0 eq) at −60 °C and the 1H-, 13C-, 19F- and 2D NMR were acquired. Chemical shifts are downfield from tetramethylsilane for 1H- and 13C-NMR and from 1% trifluoroacetic acid in CDCl3 for 19F-NMR.

p-Tolyl 2-O-benzoyl-3,4,6-tri-O-benzyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (11)

Compound 11 was synthesized following the literature procedure.16 (c 1.0, CHCl3); 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.03-6.90 (m, 24 H, COPh, SPhMe, 3 CH2Ph), 5.66 (t, 1 H, J2,1 = J2,3 = 9.6 Hz, H-2), 4.98 (d, 1 H, J = 12.0 Hz, CHHPh), 4.70 (d, 1 H, J1,2 = 9.6 Hz, H-1), 4.64-4.44 (m, 4 H, CHHPh, 2 CH2Ph), 4.03 (d, 1 H, J4,5 = 3.0 Hz, H-4), 3.70-3.65 (m, 4 H, H-3, H-5, H-6a, H-6b), 2.27 (s, 3 H, SPhMe); 13C-NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δ 165.5 (1 C, 1 COPh), 138.7, 138.1, 137.9, 137.8, 133.2, 132.9, 130.4, 130.1, 130.0, 129.7, 128.7, 128.6, 128.5, 128.4, 128.3, 128.2, 128.1, 128.0, 127.7 (CH2Ph, COPh, SPhMe, some signals overlapped), 87.5 (1 C, JC-1,H-1 = 166.3 Hz, C-1), 81.4, 77.9, 74.6, 73.9, 72.9, 72.0, 70.7, 69.0, (C-2~6, 3 CH2Ph), 21.4 (1 C, SPhMe). ESI-MS [M+Na]+ calcd. for C41H40NaO6S: 683.2, found: 683.2.

p-Tolyl 2-O-benzoyl-3,4,6-tri-O-benzyl-α,β-d-galactopyranosyl-(1→4)-2,3-di-O-benzoyl-6-O-benzyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (12α and 12β)

Donor 11 (25 mg, 37.8 µmol, 1.0 eq) and AgOTf (29.9 mg, 113.5 µmol, 3.0 eq) were placed in an NMR tube and dried in vacuo for 3 hours. CDCl3 (0.75 mL) was added slowly at −60 °C. Then the donor was pre-activated by the addition of p-TolSCl (6.0 µL, 37.8 µmol, 1.0 eq) at −60 °C. After 1H-, 13C-, 19F- and 2D NMR were acquired at −60 °C, a solution of the acceptor 4 (20.0 mg, 34.2 µmol, 0.9 eq) and TTBP (9.0 mg, 37.8 µmol, 1.0 eq) in CDCl3 (0.25 mL) was added to the NMR tube. The reaction mixture was gradually warmed up to rt in 3 hours. The reaction mixture was quenched by Et3N, filtered through Celite. The filtrate was concentrated and purified by flash column chromatography (toluene: hexanes: ethyl acetate = 10 : 10 : 1) to give 12α (6.0 mg, 5.0 µmol, 8%) and 12β (37.0 mg, 33 µmol, 48%). For α-isomer 12α: (c 1.0, CHCl3); 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.23-7.00 (m, 34 H, 2 COPh, SPhMe, 4 CH2Ph), 5.77 (t, 1 H, J2,1 = J2,3 = 9.6 Hz, H-2), 5.70 (dd, 1 H, J2’,1’ = 3.2 Hz, J2’,3’ = 8.4 Hz, H-2’), 5.24 (dd, 1 H, J3,2 = 9.6 Hz, J3,4 = 2.4 Hz, H-3), 5.20 (d, 1 H, J1’,2’ = 3.2 Hz, H-1’), 4.84 (d, 1 H, J = 11.2 Hz, CHHPh), 4.83 (d, 1 H, J1,2 = 9.6 Hz, H-1), 4.70-4.44 (m, 4 H, CHHPh, CH2Ph), 4.30-3.77 (m, 8 H, H-4, H-5, H-6a,H-6b, 2 CH2Ph), 3.60-3.33 (m, 2 H, H-3’, H-6’a), 3.33 (dd, 1 H, J6’b,5’ = J6’b,6’a = 8.8 Hz, H-6’b), 2.80 (dd, 1 H, J5’,6’b = 5.2 Hz, J5’,6’a = 8.8 Hz, H-5’), 2.17 (s, 3 H, SPhMe); HRMS [M+Na]+ calcd. for C68H64NaO13S: 1143.3965; found: 1143.3972. For β-isomer 12β: (c 1.0, CHCl3); 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.10-6.90 (m, 34 H, 2 COPh, SPhMe, 4 CH2Ph), 5.64 (dd, 1 H, J2’,1’ = 7.8 Hz, J2’,3’ = 9.6 Hz, H-2’), 5.48 (t, 1 H, J2,1 = J2,3 = 9.6 Hz, H-2), 5.38 (dd, 1 H, J3,2 = 9.6 Hz, J3,4 = 2.4 Hz, H-3), 4.98 (d, 1 H, J = 11.8 Hz, CHHPh), 4.79 (d, 1 H, J1,2 = 9.6 Hz, H-1), 4.71 (d, 1 H, J1’,2’ = 7.8 Hz, H-1’), 4.60 (d, 1 H, J = 12.6 Hz, CHHPh), 4.57 (d, 1 H, J = 12.0 Hz, CHHPh), 4.55 (d, 1 H, J = 12.0 Hz, CHHPh), 4.50 (d, 1 H, J = 11.8 Hz, CHHPh), 4.45-4.41 (m, 2 H, H-4, CHHPh), 4.26 (s, 1 H, CH2Ph), 3.92-3.73 (m, 3 H, H-4’, H-5, H-6a, H-6b), 3.55 (dd, 1 H, J6’a,5’ = J6’a,6’b = 8.4 Hz, H-6’a), 3.43 (dd, 1 H, J3’,2’ = 9.6 Hz, J3’,4’ = 2.4 Hz, H-3’), 3.32 (dd, 1 H, J6’b,5’ = 5.4 Hz, J6’b,6’a = 8.4 Hz, H-6’b), 3.26 (dd, 1 H, J5’,6’b = 5.4 Hz, J5’,6’a = 8.4 Hz, H-5’), 2.21 (s, 3 H, SPhMe); 13C-NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δ 166.0, 165.8, 164.7 (3 C, 3 COPh), 138.8, 138.7, 137.9, 137.9, 133.6, 133.1, 132.8, 132.7, 130.8, 130.3, 130.0, 129.9, 129.7, 129.3, 129.2, 128.7, 128.6, 128.5, 128.4, 128.3, 128.2, 128.1, 128.0, 127.9, 127.8, 127.7, 127.6, (CH2Ph, COPh, SPhMe, some signals overlapped), 101.0 (1 C, JC-1,H-1 = 165.3 Hz, C-1), 87.0 (1 C, JC-1’,H-1’ = 162.4 Hz, C-1’), 80.5, 78.4, 75.7, 74.8, 73.8, 73.7, 72.8, 72.2, 72.1, 71.9, 70.0, 68.7, 68.3, (C-2~6, 4 CH2Ph, some signals overlapped), 21.3 (1 C, SPhMe). HRMS [M+H]+ calcd. for C68H65O13S: 1121.4146; found: 1121.4130.

p-Tolyl 2-O-benzoyl-3-O-benzyl-4-O-tert-butyldimethylsilyl-6-O-p-methoxylbenzyl-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→4)-2,3,6-tri-O-benzoyl-1-thio-β-d-glucopyranoside (14)

Compound 14 (60 mg, 74%) was prepared according to the general procedure for glycosylation using donor 13 (50 mg, 69.9 µmol, 1.0 eq) and acceptor 3 (37.7 mg, 63.0 µmol) and purified by flash column chromatography (hexanes : ethyl acetate = 4:1). (c 1.0, CHCl3); 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.10-6.70 (m, 33 H, 4 COPh, SPhMe, CH2 Ph, CH2PhOMe), 5.52 (t, 1 H, J2,1 = J2,3 = 9.6 Hz, H-2), 5.38 (dd, 1 H, J3,2 = 9.6 Hz, J3,4 = 3.0 Hz, H-3), 5.35 (dd, 1 H, J2’,1’ = J2’,3’ = 8.4 Hz, H-2’), 4.81 (d, 1 H, J1,2 = 9.6 Hz, H-1), 4.74 (d, 1 H, J1’,2’ = 7.8 Hz, H-1’), 4.72 (dd, 1 H, J6a,5 = 3.0 Hz, J6a,6b = 12.6 Hz, H-6a), 4.69 (d, 1 H, J = 11.4 Hz, CHHPh), 4.62 (dd, 1 H, J6b,5 = 8.4 hz, J6a,6b = 12.6 Hz, H-6b), 4.60 (d, 1 H, J = 11.4 Hz, CHHPh), 4.52 (d, 1 H, J4,3 = 3.0 Hz, H-4), 4.47 (d, 1 H, J = 11.4 Hz, CHHPhOMe), 4.35 (d, 1 H, J = 11.4 Hz, CHHPhOMe), 4.08 (dd, 1 H, J5,6a = 3.0 Hz, J5,6b = 8.4 Hz, H-5), 3.72-3.62 (m, 4 H, H-4’, CH2PhOMe), 3.61 (dd, 1 H, J6’a,5’ = 1.8 Hz, J6’a,6’b = 10.2 Hz, H-6’a), 3.53 (dd, 1 H, J3’,2’ = J3,4 = 8.4 Hz, H-3’), 3.50 (dd, 1 H, J6’b,5’ = 6.0 Hz, J6’a,6’b = 10.2 Hz, H-6’b), 3.33 (ddd, 1 H, J5’,4’ = 7.8 Hz, J5’,6’a = 1.8 Hz, J5’,6’b = 6.0 Hz, H-5’), 2.19 (s, 3 H, SPhMe), 0.76 (s, 9 H, tert-butyl), −0.05 (s, 3 H, Me), −0.10 (s, 3 H, Me); 13C-NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δ 166.5, 166.0, 165.6, 164.8 (4 C, COPh), 159.3, 138.1, 137.8, 133.6, 133.3, 133.2, 133.1, 132.4, 130.4, 130.2, 130.1, 130.0, 129.9, 129.8, 129.7, 129.6, 129.1, 128.7, 128.6, 128.5, 128.4, 128.3, 127.7, 127.5, 114.0, (CH2Ph-C, CH2PhOMe, SPhMe, some signals overlapped), 100.9 (1 C, JC-1’,H-1’ = 165.4 Hz, C-1’), 87.5 (1 C, JC-1,H-1 = 163.6 Hz, C-1), 76.6, 76.5, 75.2, 74.8, 74.3, 73.3, 73.2, 71.2, 69.2, 68.5, 65.4 (12 C, C-2~6, CH2Ph, CH2PhOMe, some signals overlapped), 55.4 (1 C, H2PhOMe), 26.1, 21.4, 18,2 (5 C, SPhMe, C(Me)3, C(Me)3, some signals overlapped), −3.64, −4.63 (2 C, SiMe). ESI-MS: [M + Na]+ calcd. for C68H72O15NaSSi: 1211.4; found 1211.4. HRMS [M+Na]+ calcd. for C68H72O15NaSSi: 1211.4259; found: 1211.4252.

p-Tolyl 2-O-benzoyl-3-O-benzyl-4-O-tert-butyldimethylsilyl-6-O-p-methoxylbenzyl-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→4)-2,3-di-O-benzoyl-6-O-benzyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (15)

Compound 15 (32 mg, 26.5 µmol, 70%) was prepared according to the general procedure for glycosylation using donor 13 (31 mg, 43.4 µmol, 1.0 eq) and acceptor 4 (20.0 mg, 34.2 µmol, 0.9 eq) and purified by flash column chromatography (hexanes: ethyl acetate = 4:1). (c 1.0, CHCl3); 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.00-6.80 (m, 33 H, 3 COPh, SPhMe, 2 CH2 Ph, CH2PhOMe), 5.47 (dd, 1 H, J2,1 = J2,3 = 9.6 Hz, H-2), 5.37 (dd, 1 H, J3,2 = 9.6 Hz, J3,4 = 3.0 Hz, H-3), 5.28 (dd, 1 H, J2’,1’ = 7.8 Hz, J2’,3’ = 8.4 Hz, H-2’), 4.80 (d, 1 H, J1,2 = 9.6 Hz, H-1), 4.79 (d, 1 H, J1’,2’ = 7.8 Hz, H-1’), 4.66 (d, 1 H, J = 10.8 Hz, CHHPh), 4.56 (d, 1 H, J = 10.8 Hz, CHHPh), 4.52 (d, 1 H, J = 11.4 Hz, CHHPh), 4.47-4.45 (m, 2 H, CHHPh, H-4), 4.41 (d, 1 H, J = 12.0 Hz, CHHPh), 4.29 (d, 1 H, J = 12.0 Hz, CHHPh), 3.90-3.83 (m, 3 H, H-5, H-6a,H-6b), 3.75-3.71 (m, 4 H, H-4’, CH2PhOMe), 3.54-3.21 (m, 4 H, H-3’, H-6’a, H-6’b, H-5’), 2.21 (s, 3 H, SPhMe), 0.77 (s, 9 H, tert-butyl), −0.07 (s, 3 H, Me), −0.12 (s, 3 H, Me); 13C-NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δ 165.9, 165.7, 164.8 (3 C, COPh), 159.4, 138.8, 138.1, 137.8, 133.3, 133.1, 132.8, 130.4, 130.2, 130.1, 129.9, 129.8, 129.3, 129.2, 128.6, 128.5, 128.4, 128.3, 127.8, 127.7, 127.6, 127.5, 114.0, (CH2Ph-C, CH2PhOMe, SPhMe, some signals overlapped), 103.8 (1 C, JC-1’,H-1’ = 166.0 Hz, C-1’), 87.2 (1 C, JC-1,H-1 = 159.0 Hz, C-1), 83.4, 78.7, 76.6, 75.6, 74.7, 74.3, 73.7, 73.2, 72.8, 71.0, 70.9, 69.1, 68.7, 68.2, 66.7 (13C, C-2~6, 2 CH2Ph, CH2PhOMe, some signals overlapped), 55.5 (1 C, CH2PhOMe), 26.1, 26.1, 21.3, 18,5 (5 C, SPhMe, C(Me)3, C(Me)3, some signals overlapped), −3.66, −4.67 (2 C, SiMe); HRMS: [M + Na]+ calcd. for C68H74O14NaSSi: 1197.4466; found 1197.4451.

p-Tolyl (benzyl 2-O-benzoyl-3-O-benzyl-4-O-tert-butyldimethylsilyl-β-d-glucopyranosyluronate)-(1→3)-4,6-O-benzylidene-2-(2,2,2-tri-chloroacetylamino)-2-deoxy-1-thio-β-d-glucopyranoside (24)

Compound 24 was synthesized from donor 23 and acceptor 21 in 73% yield following the general procedure of single step glycosylation and purified by flash column chromatography (hexanes : ethyl acetate = 3:1). (c = 1, CH2Cl2); 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.87-7.85 (m, 2H, aromatic), 7.52-7.49 (m, 1H, aromatic), 7.36-7.25 (m, 9H, aromatic), 7.16-7.08 (m, 6H, aromatic), 6.93-6.89 (m, 1H, aromatic), 5.30 (s, 1H, CHPh), 5.27 (d, 1H, J1,2 = 10.2 Hz, H-1), 5.17-5.10 (m, 3H, CH2Ph, H-2’), 4.99 (d, 1H, J1’,2’ = 7.2 Hz, H-1’), 4.64-4.56 (m, 2H, CH2Ph), 4.52 (t, 1H, J = 9.6 Hz, H-4’), 4.29-4.26 (m, 1H, H-6a), 4.15-4.12 (m, 1H, H-4’), 3.80 (d, 1H, J4’,5’ = 6.0 Hz, H-5’), 3.67-3.63 (m, 2H, H-4, H-6b), 3.52-3.47 (m, 2H, H-2, H-5), 3.27-3.25 (m, 1H, H-3’), 2.34 (s, 3H, SPhCH3); 13C-NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δ 168.3, 165.1, 161.5, 139.0, 137.6, 137.0, 135.0, 133.9, 133.2, 130.0, 129.8, 129.4, 129.1, 128.7, 128.6, 128.3 (×2), 128.1, 127.5, 127.4, 127.0, 126.2, 101.5, 98.8, 84.2, 81.0, 79.9, 77.3, 76.2, 74.0, 71.2, 70.5, 67.2, 57.2, 25.7, 21.2, 17.8, −4.5, −5.3; ESI-MS [M+Na]+ calcd. for C55H60Cl3NNaO12SSi 1114.3, found 1114.6; HRMS [M+Na]+ calcd. for C55H60Cl3NNaO12SSi 1114.2569, found 1114.2573; gHMQC (without 1H decoupling): 1JC1,H1 = 161.9 Hz, 1JC1’,H1’ = 164.6 Hz.

p-Tolyl 2-O-benzoyl-3,4,6-tri-O-benzyl-β-d-galactopyranosyl-(1→3)-4,6-O-benzylidene-2-deoxy-2-N-phthalimido-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (26)

Compound 26 was synthesized from donor 11 and acceptor 25 in 65% yield (51% β + 14% α) following the general procedure of single step glycosylation. (c = 1, CH2Cl2); 26β 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.70-7.68 (m, 2H), 7.56-7.55 (m, 1H), 7.50-7.42 (m, 4H, aromatic), 7.36-7.16 (m, 19H, aromatic), 7.12-7.10 (m, 1H, aromatic), 7.04-6.95 (m, 6H, aromatic), 5.53-5.50 (m, 1H), 5.52 (d, 1H, J1,2 = 7.8 Hz, H-1), 5.28 (s, 1H, CHPh), 4.93 (d, 1H, J = 12 Hz), 4.80-4.78 (m, 1H), 4.66 (d, 1H, J1’,2’ = 8.4 Hz, H-1’), 4.62-4.56 (m, 2H), 4.50 (d, 1H, J = 12 Hz), 4.43-4.42 (m, 1H), 4.33-4.23 (m, 4H), 3.90-3.88 (m, 2H), 3.54 (s, 1H), 3.46-3.42 (m, 3H), 3.05-3.03 (m, 1H), 2.26 (s, 3H, SPhCH3); 13C-NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δ 168.9, 166.9, 165.3, 138.8, 138.1, 138.0, 137.6, 134.1, 133.9, 133.6, 133.0, 131.9, 131.7, 129.9, 129.8, 129.6, 128.8, 128.7, 128.5 (×2), 128.4, 128.1 (×3), 127.9, 127.8, 127.7 (×2), 127.6, 126.8, 123.7, 122.9, 101.3, 100.4, 82.9, 80.3, 75.1, 74.4, 73.6 (×2), 73.2, 72.1, 71.7, 71.4, 70.4, 69.5, 68.2, 50.7, 21.4; ESI-MS [M+Na]+ calcd for C62H57NNaO12S 1063.3, found 1063.2; HRMS [M+NH4]+ calcd for C62H61N2O12S 1057.3945, found 1057.3933; gHMQC (without 1H decoupling): 1JC1,H1 = 161.1 Hz, 1JC1’,H1’ = 159.3 Hz.

Methyl 2-O-benzoyl-3-O-benzyl-4-O-tert-butyldimethylsilyl-6-O-p-methoxybenzyl-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→3)-4,6-O-benzylidene-2-deoxy-2-N-phthalimido-β-d-galactopyranosyl-(1→4)-2,3-di-O-benzyl-6-O-p-methoxybenzyl-β-d-glucopyranoside (28)

Compound 28 was synthesized by a three-component one-pot synthesis procedure. After the donor 13 (50 mg, 69.93 µmol) and activated molecular sieve MS-4 Å (500 mg) were stirred for 30 minutes at room temperature in CH2Cl2 (5 mL), the solution was cooled to −60 °C, followed by addition of AgOTf (54 mg, 209 µmol) in Et2O (1.5 mL). The mixture was stirred for 5 minutes at −60 °C and then p-TolSCl (11.1 µL, 69.9 µmol) was added to the solution. (See the general procedure for single step pre-activation based glycosylation for precautions) The mixture was vigorously stirred for 10 minutes, followed by addition of a solution of building block 25 (28.2 mg, 56.0 µmol) and TTBP (17.4 mg, 69.9 µmol) in CH2Cl2 (1 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred for 2 hours from −60 to −20 °C and then the mixture was cooled down to −60 °C, followed by sequential addition of AgOTf (18 mg, 69.9 µmol) in Et2O (1 mL), acceptor 27 (20.8 mg, 42.0 µmol) and TTBP (17.4 mg, 69.9 µmol) in CH2Cl2 (1 mL). The mixture was stirred for 5 minutes at −60 °C and then p-TolSCl (8.9 µL, 56.0 µmol) was added into the solution and the reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h from −60 to −20 °C. The reaction was quenched with Et3N (50 µL), concentrated under vacuum to dryness. The resulting residue was diluted with CH2Cl2 (20 mL), followed by filtration. The organic phase was washed with saturated aqueous NaHCO3, H2O and then dried over Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated. Silica gel column chromatography (3:1:1 hexanes - ethyl acetate - CH2Cl2) afforded 28 as a white solid (41.2 mg, 67 %). Mp 82 - 84 °C; (c = 1, CH2Cl2); 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.50-7.34 (m, 7H. aromatic), 7.31-7.16 (m, 16H, aromatic), 7.12-7.00 (m, 8H, aromatic), 6.92-6.90 (m, 2H, aromatic), 6.83-6.79 (m, 4H, aromatic), 5.40 (s, 1H, CHPh), 5.30 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 5.12 (t, 1H, J = 7.8 Hz), 5.02 (d, 1H, J = 11.4 Hz), 4.85 (d, 1H, J = 12 Hz), 4.76 (d, 1H, J = 11.4 Hz), 4.70 (d, 1H, J = 7.2 Hz), 4.66-4.64 (m, 1H), 4.60-4.57 (m, 2H), 4.46-4.32 (m, 5H), 4.10 (d, 1H, J = 7.8 Hz), 4.09-4.07 (m, 1H), 3.99-3.97 (m, 1H), 3.78-3.76 (m, 7H), 3.65-3.64 (m, 1H), 3.59-3.55 (m, 2H), 3.53-3.46 (m, 3H), 3.43-3.37 (m, 4H), 3.32-3.28 (m, 3H), 3.14-3.10 (m, 2H), 2.96 (s, 1H), 0.78 (s, 9H, (CH3)3CSi), −0.11(s, 3H, CH3Si), −0.15 (s, 3H, CH3Si); 13C-NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δ 169.4, 167.3, 164.4, 159.5, 159.1, 139.6, 138.7, 138.3, 137.8, 133.8, 133.6, 132.7, 131.4, 131.2, 130.7, 130.2, 129.6 (×2), 129.1, 128.7, 128.4 (×2), 128.3, 128.2 (×2), 128.1, 127.7, 127.5, 127.3 (×2), 127.1, 126.7, 123.4, 122.6, 114.0, 113.7, 104.5, 101.8, 100.7, 98.5, 83.6, 83.3, 82.3, 76.5, 76.3, 76.0, 75.1, 74.9, 74.8, 74.7, 74.3, 74.1, 73.3, 72.4, 71.3, 70.0, 69.0, 68.2, 67.0, 57.1, 55.5 (×2), 52.5, 26.1, 18.1, −3.7, −4.5; HRMS: [M+Na]+ calcd for C84H93NNaO20Si 1486.5958; found 1486.5946; gHMQC (without 1H decoupling): 1JC1,H1 = 159.3 Hz, 162.2 Hz, 162.2 Hz.

Methyl 2-O-benzoyl-3-O-benzyl-4-O-tert-butyldimethylsilyl-6-O-p-methoxybenzyl-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→4)-2-azido-3,6-di-O-benzyl-2-deoxy-α-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→-4)-2,3-di-O-benzyl-6-O-p-methoxybenzyl-β-d-glucopyranoside (30)

Compound 30 was synthesized by a three-component one-pot procedure. After the donor 13 (50 mg, 69.93 µmol) and activated molecular sieve MS-4 Å (500 mg) were stirred for 30 minutes at room temperature in CH2Cl2 (5 mL), the solution was cooled to −60 °C, followed by addition of AgOTf (54 mg, 209 µmol) in Et2O (1.5 mL). The mixture was stirred for 5 minutes at −60 °C and then p-TolSCl (11.1 µL, 69.9 µmol) was added into the solution. (See the general procedure for single step pre-activation based glycosylation for precautions) The mixture was vigorously stirred for 10 minutes, followed by addition of a solution of acceptor 29 (32.7 mg, 66.4 µmol) and TTBP (17.4 mg, 69.9 µmol) in CH2Cl2 (1 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred for 2 hours from −60 to −20 °C and then the mixture was cooled down to −60 °C, followed by sequential addition of AgOTf (18 mg, 69.9 µmol) in Et2O (1 mL), acceptor 27 (27.7 mg, 55.9 µmol) and TTBP (17.4 mg, 69.9 µmol) in CH2Cl2 (1 mL). The mixture was stirred for 5 minutes at −60 °C and then p-TolSCl (10.5 µL, 66.4 µmol) was added to the solution and the reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h from −60 to −20 °C. The reaction was quenched with Et3N (50 µL), concentrated under vacuum to dryness. The resulting residue was diluted with CH2Cl2 (20 mL), followed by filtration. The organic phase was washed with saturated aqueous NaHCO3, H2O and then dried over Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated. Silica gel column chromatography (5:1:1 hexanes - ethyl acetate - CH2Cl2) afforded 30 as a gel (39.7 mg, 49 %). (c = 1, CH2Cl2); 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.77-7.75 (m, 2H. aromatic), 7.44-7.20 (m, 21H, aromatic), 7.12-7.06 (m, 9H, aromatic), 6.98-6.97 (m, 2H, aromatic), 6.84-6.82 (m, 2H, aromatic), 6.77-6.76 (m, 2H, aromatic), 5.66 (d, 1H, J = 4.2 Hz), 5.19 (t, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 5.13 (d, 1H, J = 11.4 Hz), 5.00 (d, 1H, J = 10.2 Hz), 4.89 (d, 1H, J = 11.4 Hz), 4.75-4.59 (m, 6H), 4.47-4.42 (m, 3H), 4.24 (d, 1H, J = 7.8 Hz), 4.11 (d, 1H, J = 12 Hz), 4.02-3.95 (m, 3H), 3.87-3.84 (m, 1H), 3.79-3.61 (m, 9H), 3.60-3.58 (m, 1H), 3.51-3.50 (m, 4H), 3.41-3.25 (m, 8H), 3.12-3.06 (m, 2H), 3.43-3.37 (m, 4H), 3.32-3.28 (m, 3H), 3.14-3.10 (m, 2H), 2.96 (s, 1H), 0.87 (s, 9H, (CH3)3CSi), −0.02(s, 3H, CH3Si), −0.04 (s, 3H, CH3Si). 13C-NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δ 164.7, 158.9, 158.8, 138.7, 138.3 (×2), 137.8, 137.7, 133.2, 130.6, 130.2, 129.5 (×2), 129.0, 128.9 (×2), 128.7, 128.4 (×2), 128.3 (×3), 128.2, 128.0 (×2), 127.7, 127.6, 127.5 (×2), 127.4, 127.3, 113.6, 113.4, 104.5, 99.7, 97.3, 84.9, 83.1, 82.6, 77.5, 76.8, 75.6, 75.1 (×2), 75.0, 74.5 (×2), 74.0, 73.7, 73.0, 72.4, 72.3, 71.3, 70.8, 69.0, 68.3, 66.8, 62.4, 57.0, 55.2 (×2), 25.9 (×2), 17.9, −3.8, −4.7; HRMS: [M+Na]+ calcd for C83H97N3NaO18Si 1474.6434; obsd 1474.6414; gHMQC (without 1H decoupling): 1JC1’,H1’ = 172.6 Hz, other two 1JC1,H1 = 160.2 Hz, 162.8 Hz.

2,3,4,6-Tetra-O-benzoyl-α-d-galactopyranosyl triflate (38)

Compound 38 was obtained according to the general procedure. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, −60 °C): δ 8.12-7.20 (m, 28 H, 4 COPh, (SPhMe)2), 6.57 (d, 1 H, J1,2 = 3.2 Hz, H-1), 6.17 (d, 1 H, J1,2 = 2.0 Hz, H-4), 6.11-5.80 (m, 2 H, H-2, H-3), 4.94 (dd, 1 H, J5,6a = 8.0 Hz, J5,6b = 5.2 Hz, H-5), 4.66 (dd, 1 H, J6a,5 = 8.0 Hz, J6a,6b = 11.6 Hz, H-6a), 4.43 (dd, 1 H, J6b,5 = 5.2 Hz, J6b,6a = 11.6 Hz, H-6b), 2.44 (s, 6 H, (SPhMe)2); 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3, −60 °C): δ 166.4, 165.8, 165.8, 165.5 (4 C, COPh), 134.7, 134.3, 134.2, 131.9, 130.4, 130.3, 130.2, 130.0, 129.3, 129.2, 129.0, 128.9, 128.8, 128.3, 128.2, 127.7 (COPh-C, (SPhMe)2, some signals overlapped), 104.4 (1 C, C-1), 71.6, 67.7, 67.4, 66.7, 62.4 (5C, C-2~6), 22.4 (2 C, (SPhMe)2).

2,3,4,6-Tetra-O-benzoyl-β-d-galactopyranosyl-(1→6)-1,2:3,4-diisopropylidene-α-d-galactopyranoside (40)

Donor 5 (31 mg, 44.1 µmol, 1.0 eq) and AgOTf (33.9 mg, 132.3 µmol, 3.0 eq) were added to an NMR tube and dried in vacuo for 3 hours. CDCl3 (0.75 mL) was added slowly at −60 °C. Then the donor was pre-activated by the addition of p-TolSCl (7.1 µL, 44.1 µmol, 1.0 eq) at −60 °C and 1H-, 13C-, 19F- and 2D NMR were acquired at −60 °C. This was followed by the addition of acceptor 39 (10.3 mg, 39.7 µmol, 0.9 eq) and TTBP (11.0 mg, 44.1 µmol, 1.0 eq) as acid scavenger in CDCl3 (0.25 mL). The reaction mixture was quenched by Et3N, and purified by flash column chromatograph (hexanes : ethyl acetate = 4:1) to give 40 (29.9 mg, 35.7 µmol, 90%) as a colorless syrup. (c 1.0, CHCl3); 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.07-7.20 (m, 20 H, 4 COPh), 5.83 (d, 1 H, J4’,3’ = 3.6 Hz, H-4’), 5.80 (dd, 1 H, J2’,1’ = 7.8 Hz, J2’,3’ = 10.8 Hz, H-2’), 5.60 (dd, 1 H, J3’,2’ = 10.8 Hz, J3’,4’ = 3.6 Hz, H-3’), 5.40 (d, 1 H, J1,2 = 3.2 Hz, H-1), 5.01 (d, 1 H, J1’,2’ = 7.8 Hz, H-1’), 4.67 (dd, 1 H, J6a’,5’ = 5.4 Hz, J6a’,6b’ = 11.4 Hz, H-6’a), 4.42-3.38 (m, 2 H, H-5’, H-6’b), 4.33 (t, 1 H, J3,2 = J3,4 = 6.6 Hz, H-3), 4.20 (dd, 1 H, J2,1 = 3.2 Hz, J2,3 = 6.6 Hz, H-2), 4.06 (dd, 1 H, J6a,5 = 7.2 Hz, J6a,6b = 10.8 Hz, H-6a), 3.95-3.70 (m, 2 H, H-5, H-6b), 1.38 (s, 3 H, CH3), 1.23 (s, 3 H, CH3), 1.20 (s, 3 H, CH3), 1.18 (s, 3 H, CH3); 13C-NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δ 166.3, 165.8, 165.7, 165.5 (4 C, 4 COPh), 133.8, 133.5, 133.3, 130.3, 130.2, 130.0, 129.6, 129.2, 129.0, 128.8, 128.7, 128.5, (COPh-C, some signals overlapped), 109.4 (1 C, C(CH3)2), 108.7 (1 C, C(CH3)2), 101.9 (1 C, JC-1’,H-1’ = 165.4 Hz, C-1’), 96.4 (1 C, JC-1,H-1 = 176.1 Hz, C-1), 72.0, 71.5, 71.2, 70.7, 70.5, 69.9, 68.6, 68.4, 67.7, 62.3 (C-2~6, some signals overlapped), 26.1, 25.9, 25.1, 24.4 (4 C, 2 C(CH3)2); ESI-MS: [M + Na]+ calcd for C46H46NaO15 861.3; found 861.2; HRMS: [M + NH4]+ calcd for C46H50NO15 856.3180; found 856.3162.

3,4,6-Tri-O-benzyl-d-galactopyranosyl benzoxonium ion (41)

Compound 41 was obtained according to the general experimental procedure. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, −60 °C): δ 8.10-7.24 (m, 29 H, H-1, 3 CH2Ph, CPh, (SPhMe)2), 5.77 (bs, 1 H, H-2), 4.89-4.67 (m, 3 H, 2 CHHPh, CHHPh), 4.62-4.58 (m, 2 H, CHHPh, H-5), 4.42-4.34 (m, 2 H, CHHPh, H-3), 4.30-4.20 (m, 2 H, CHHPh, H-4), 3.79-3.76 (1 H, H-6a), 3.64-3.58 (1 H, H-6b), 2.44 (s, 6 H, (SPhMe)2); 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3, −60 °C): δ 180.8 (1 C, C-7), 140.9, 137.7, 137.5, 133.9, 131.8, 131.0, 130.3, 130.0, 129.4, 128.8, 128.7, 128.5, 128.3, 128.1, 127.5, 125.0, 121.8, 118.6, 118.0 (CPh-C, CH2Ph, (SPhMe)2, some signals overlapped), 114.2 (1 C, C-1), 83.9 (1 C, C-2), 75.6, 74.8, 73.6, 71.6, 69.0 (7 C, C-3~6, CH2Ph), 22.4 (1 C, (SPhMe)2).

2,3,4,6-Tetra-O-acetyl-α-d-glucopyranosyl triflate (44) and 3,4,6-tri-O-acetyl-D-glucopyranosyl acetoxonium ion (45)

The mixture of intermediates 44 and 45 was obtained following the general experimental procedure. For the mixture of 44 and 45 in 1 : 1 ratio: 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, −60 °C): δ 7.41-7.24 (m, 9 H, H-1, 2 (SPhMe)2), 6.21 (d, 1 H, J1,2 = 2.4 Hz, H-1 from 44), 5.73 (1 H, H-3 from 45), 5.57 (3 H, H-2 from 45, H-3 from 44, H-4 from 45), 5.31 (2 H, H-2 from 44, H-4 from 44), 4.82 (1 H, H-5 from 45), 4.44 (1 H, H-5 from 44), 4.14 (4 H, 2 H-6 from 44, 2 H-6 from 45), 2.82 (3 H, CCH3 from 45), 2.44 (s, 12 H, 2 (SPhMe)2), 2.19, 2.15, 2.14, 2.09, 2.07, 2.03 (21 H, 7 COC H3); 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3, −60 °C): δ 191.7 (1 C, C-7 from 45), 171.4, 171.3, 170.8, 170.8, 170.7, 170.5, 169.6 (7 C, 4 COCH3 from 44 and 3 COCH3 from 45), 132.2, 128.8, 121.9, 118.7 ((SPhMe)2, some signals overlapped), 113.3 (1 C, C-1 from 45), 104.1 (1 C, C-1 from 44), 80.3, 72.5, 70.9, 68.9, 66.7, 66.6, 65.8, 64.2, 62.5, 61.5 (12 C, C-2~6, some signals overlapped), 22.5, 21.4, 21,4, 21.3, 21.2, 21.0, 17.6 (9 C, 7 COCH3, CCH3, (SPhMe)2, some signals overlapped). For 44: 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, −20 °C): δ 7.34-7.09 (m, 8 H, H-1, (SPhMe)2), 6.21 (d, 1 H, J1,2 = 2.4 Hz, H-1), 5.57 (s, 1 H, H-3), 5.33-5.30 (m, 2 H, H-2, H-4), 4.46-4.41 (m, 1 H, H-5), 4.18-4.10 (m, 4 H, 2 H-6), 2.44 (s, 6 H, (SPhMe)2), 2.18, 2.15, 2.14, 2.07, 2.03 (s, 12 H, 4 COCH3); 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3, −20 °C): δ 171.3, 170.5, 170.5, 170.5 (4 C, 4 COCH3), 130.4, 129.4, 128.7, 118.7 ((SPhMe)2, some signals overlapped), 104.1 (1 C, C-1), 71.0, 66.8, 66.7, 65.9, 61.4 (5 C, C-2~6), 21.6, 21,3, 21.2, 21.1, 21.0 (5 C, (5 C, 5 COCH3, (SPhMe)2).

2,3,4,6-Tetra-O-acetyl-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(1→6)-1,2:3,4-diisopropylidene-α-d-galactopyranoside (46)

Donor 16 (20.0 mg, 44.0 µmol, 1.0 eq) and AgOTf (33.9 mg, 132.0 µmol, 3.0 eq) were added to an NMR tube and dried under in vacuo for 3 hours. CDCl3 (0.75 mL) was added slowly at −60 °C. Then the donor was pre-activated by addition of the p-TolSCl (7.0 µL, 44.0 µmol, 1.0 eq) at −60 °C and the 1H-, 13C-, 19F- and 2D NMR spectra were acquired. This was followed by addition of the acceptor 39 (10.3 mg, 39.7 µmol, 0.9 eq) and TTBP (10.9 mg, 44.0 µmol, 1.0 eq) as acid scavenger in CDCl3 (0.25 mL). After reaching −20 °C, the reaction mixture was quenched by Et3N and purified by flash column chromatograph (hexanes : ethyl acetate = 3:1) to give 46 (20.0 mg, 33.7 µmol, 85.0%) as a white foam. (c 1.0, CHCl3); 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 5.47 (d, 1 H, J1,2 = 4.8 Hz, H-1), 5.35 (d, 1 H, J4,3 = 3.0 Hz, H-4), 5.18 (dd, 1 H, J2’,1’ = 8.4 Hz, J2’,3’ = 10.2 Hz, H-2’), 4.98 (dd, 1 H, J3’,2’ = 10.8 Hz, J3’,4’ = 3.0 Hz, H-3’), 4.57-4.54 (m, 2 H, H-1’, H-4’), 4.26 (dd, 1 H, J2,1 = 4.8 Hz, J2,3 = 2.4 Hz, H-2), 4.15-4.07 (m, 3 H, H-5’, H-6’a, H-6’b), 4.01 (dd, 1 H, J6a,5 = 3.0 Hz, J6a,6b = 10.8 Hz, H-6a), 3.91-3.84 (m, 2 H, H-3, H-5), 3.65 (dd, 1 H, J6b,5 = 3.0 Hz, J6b,6a = 10.8 Hz, H-6b), 2.11 (s, 3 H, COCH3), 2.04 (s, 3 H, COCH3), 2.02 (s, 3 H, COCH3), 1.95 (s, 3 H, COCH3), 1.45(s, 3 H, C(CH3)2), 1.42(s, 3 H, C(CH3)2), 1.29(s, 3 H, C(CH3)2), 1.29 (s, 3 H, C(CH3)2); 13C-NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δ 170.7, 170.5, 170.4, 170.0 (4 C, 4 COCH3), 109.6, 108.9 (2 C, 2 C(CH3)2), 102.2 (1 C, JC-1’,H-1’ = 167.4 Hz, C-1’), 96.4 (1 C, JC-1,H-1 = 177.6 Hz, C-1), 71.5, 71.0, 70.8, 70.7, 70.6, 69.8, 68.8, 68.1, 67.2, 61.4 (C-2~6, some signals overlapped), 26.2, 26.1, 25.3, 24.5 (4 C, 2 C(CH3)2), 21.0, 20.9, 20.9, 20.8 (4 C, 4 COCH3). ESI-MS: [M + Na]+ calcd for C26H38NaO15: 613.2; found 613.3; HRMS: [M + Na]+ calcd for C26H38NaO15: 613.2108; found 613.2114.

2-O-Benzoyl-3,4,6-tri-O-benzyl-β-d-galactopyranosyl-(1→6)-1,2:3,4-diisopropylidene-α-d-galactopyranoside (47)

(c 1.0, CHCl3); 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.05-7.11 (m 20 H, COPh, 3 CH2Ph), 5.64 (dd, 1 H, J2’,1’ = 7.8 Hz, J2’,3’ = 10.2 Hz, H-2’), 5.37 (d, 1 H, J1,2 = 4.8 Hz, H-1), 4.98 (d, 1 H, J = 12.0 Hz, CHHPh), 4.66-4.60 (3 H, H-1’, CHHPh, CHHPh), 4.50-4.42 (3 H, 2 CHHPh, CHHPh), 4.40 (dd, 1 H, J6a’,5’ = 1.8 Hz, J6a’,6b’ = 8.4 Hz, H-6a’), 4.16 (dd, 1 H, J2,1 = 4.8 Hz, J2,3 = 4.8 Hz, H-2), 4.10 (dd, 1 H, J6b’,5’ = 1.8 Hz, J6b’,6a’ = 8.4 Hz, H-6b’), 4.01 (d, 1 H, J3’,4’ = 2.4 Hz, H-4’), 3.96 (dd, 1 H, J6a,5 = 4.8 Hz, J6a,6b = 10.8 Hz, H-6a), 3.80-3.50 (m, 6 H, H-3, H-3’, H-4, H-5, H-5’, H-6b), 1.37(s, 3 H, C(CH3)2), 1.21(s, 3 H, C(CH3)2), 1.15(s, 3 H, C(CH3)2), 1.09 (s, 3 H, C(CH3)2); 13C-NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1165.6 (C, COPh), 138.7, 138.1, 137.9, 133.0, 130.5, 130.3, 128.7, 128.6, 128.5, 128.4, 128.2, 128.1, 127.9 (CH2Ph-C, COPh-C, some signals overlapped), 109.2, 108.5 (2 C, 2 C(CH3)2), 102.0 (1 C, JC-1’,H-1’ = 164.3 Hz, C-1’), 96.3 (1 C, JC-1,H-1 = 175.3 Hz, C-1), 80.9, 74.7, 73.8, 72.6, 72.0, 71.9, 71.0, 70.7, 70.6, 68.7, 68.0, 67.9, 67.6 (C-2~6, some signals overlapped), 26.1, 25.8, 25.1, 24.3 (4 C, 2 C(CH3)2); ESI-MS: [M + Na]+ calcd for C46H52NaO16: 819.3; found 819.4; HRMS: [M + NH4]+ calcd for C46H56NO16: 814.3803; found 814.3806.

Supplementary Material

General experimental procedures and selected 1H-, 13C-, 19F- and 2D NMR spectra. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful for financial support from the National Institutes of Health (R01-GM-72667). We would like to thank Dr. Yong Wah Kim (Univ. of Toledo) and Dr. Eugenio Alvarado (Univ. of Michigan) for their expert help on NMR.

References

- 1.Part of this work was carried out at Department of Chemistry, the University of Toledo.

- 2.Wang Z, Huang X. In: Comprehensive Glycoscience from Chemistry to Systems Biology. Kamerling JP, editor. Vol. 1. Elsevier; 2007. pp. 379–413. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang H, Ye X-S, Zhang L-H. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007;5:2189–2200. doi: 10.1039/b704586g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Codée JDC, Litjens REJN, van den Bos LJ, Overkleeft HS, van der Marel GA. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2005;34:769–782. doi: 10.1039/b417138c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ernst B, Hart GW, Sinaÿ P, editors. Carbohydrates in Chemistry and Biology. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu Y-S, Li Q, Zhang L-H, Ye X-S. Org. Lett. 2008;10:3445–3448. doi: 10.1021/ol801190c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun B, Srinivasan B, Huang X. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:7072–7081. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang L, Huang X. Chem. Eur. J. 2007;13:529–540. doi: 10.1002/chem.200601090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim J-H, Yang H, Park J, Boons G-J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:12090–12097. doi: 10.1021/ja052548h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamago S, Yamada T, Ito H, Hara O, Mino Y, Maruyama T, Yoshida J-I. Chem. Eur. J. 2005;11:6159–6194. doi: 10.1002/chem.200500126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang X, Huang L, Wang H, Ye X-S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:5221–5224. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Codée JDC, van den Bos LJ, Litjens REJN, Overkleeft HS, van Boeckel CAA, van Boom JH, van der Marel GA. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:1057–1064. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamago S, Yamada T, Maruyama T, Yoshida J-I. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:2145–2148. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Callam CS, Gadikota RR, Krein DM, Lowary TL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:13112–13119. doi: 10.1021/ja0349610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen HM, Poole JL, Gin DY. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001;40:414–417. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010119)40:2<414::AID-ANIE414>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim KS, Kim JH, Lee YJ, Lee YJ, Park J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:8477–8481. doi: 10.1021/ja015842s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crich D, Sun S. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:8321–8348. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahne D, Walker S, Cheng Y, Van Engen D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:6881–6882. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teumelsan N, Huang X. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:8976–8979. doi: 10.1021/jo7013824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Z, Zhou L, El-boubbou K, Ye X-S, Huang X. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:6409–6420. doi: 10.1021/jo070585g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miermont A, Zeng Y, Jing Y, Ye X-S, Huang X. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:8958–8961. doi: 10.1021/jo701694k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang L, Wang Z, Li X, Ye X-S, Huang X. Carbohydr. Res. 2006;341:1669–1679. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crich D, Li W, Li H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:15081–15086. doi: 10.1021/ja0471931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koeller KM, Wong C-H. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:4465–4493. doi: 10.1021/cr990297n. and references cited therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fraser-Reid B, Wu Z, Udodong UE, Ottosson H. J. Org. Chem. 1990;55:6068–6070. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paulsen H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1982;21:155–173. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crich D, Smith M, Yao Q, Picione J. Synthesis. 2001:323–326. [Google Scholar]

- 28.van den Bos LJ, Codee JDC, Litjens REJN, Dinkelaar J, Overkleeft HS, van der Marel GA. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007:3963–3976. doi: 10.1021/jo070704s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Codée JDC, Stubba B, Schiattarella M, Overkleeft HS, van Boeckel CAA, van Boom JH, van der Marel GA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:3767–3773. doi: 10.1021/ja045613g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van den Bos LJ, Codee JDC, van der Toorn JC, Boltje TJ, van Boom JH, Overkleeft HS, van der Marel GA. Org. Lett. 2004;6:2165–2168. doi: 10.1021/ol049380+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Magaud D, Dolmazon R, Anker D, Doutheau A, Dory YL, Deslongchamps P. Org. Lett. 2000;2:2275–2277. doi: 10.1021/ol006039q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang L, Teumelsan N, Huang X. Chem. Eur. J. 2006;12:5246–5252. doi: 10.1002/chem.200600290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gama CI, Hsieh-Wilson LC. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2005;9:609–619. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raman R, Sasisekharan V, Sasisekharan R. Chem. Biol. 2005;12:267–277. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petitou M, van Boeckel CAA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:3118–3133. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Linhardt RJ, Toida T. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004;37:431–438. doi: 10.1021/ar030138x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yeung BKS, Chong PYC, Petillo PA. In: Glycochemistry. Principles, Synthesis, and Applications. Wang PG, Bertozzi CR, editors. New York City: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 2001. pp. 425–492. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koeller KM, Wong C-H. Nature Biotech. 2000;18:835–841. doi: 10.1038/78435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crich D, Dudkin V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:6819–6825. doi: 10.1021/ja010086b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carter MB, Petillo PA, Anderson L, Lerner LE. Carbohydr. Res. 1994;258:299–306. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(94)84097-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fan Q-H, Li Q, Zhang L-H, Ye X-S. Synlett. 2006:1217–1220. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nokami T, Shibuya A, Tsuyama H, Suga S, Bowers AA, Crich D, Yoshida J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:10922–10928. doi: 10.1021/ja072440x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Honda E, Gin DY. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:7343–7352. doi: 10.1021/ja025639c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu J, Gin DY. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:9789–9797. doi: 10.1021/ja026281n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garcia B, Gin DY. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:4269–4279. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gildersleeve J, Pascal RA, Jr, Kahne D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:5961–5969. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crich D, Sun S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:11217–11223. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crich D, Vinogradova O. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:8473–8480. doi: 10.1021/jo061417b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crich D, Cai W. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:4926–4930. doi: 10.1021/jo990243d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suga S, Suzuki S, Yamamoto A, Yoshida J-I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:10244–10245. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ravenscrof M, Robert RMG, Tillet JG. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 2. 1982:1569–1572. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Forsyth DA, Osterman VM, DeMember JR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985;107:818–822. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Olah GA, Parker DG, Yoneda N. J. Org. Chem. 1977;42:32–37. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lindeman SV, Rathore R, Kochi JK. Inorg. Chem. 2000;39:5707–5716. doi: 10.1021/ic000770b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Crich D, Dai Z, Gastaldi S. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:5224–5229. doi: 10.1021/jo990424f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nukada T, Berces A, Zgierski MZ, Whitfield DM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:13291–13295. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bülow A, Meyer T, Olszewski TK, Bols M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2004:323–329. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang Z, Ollman IR, Ye X-S, Wischnat R, Baasov T, Wong C-H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:734–753. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Whitfield DM, Nukada T. Carbohydr. Res. 2007;342:1291–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2007.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mydock LK, Demchenko AV. Org. Lett. 2008;10:2107–2110. doi: 10.1021/ol800648d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mydock LK, Demchenko AV. Org. Lett. 2008;10:2103–2106. doi: 10.1021/ol800345j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hotha S, Kashyap S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:9620–9621. doi: 10.1021/ja062425c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xia J, Alderfer JL, Locke RD, Piskorz CF, Matta KL. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:2752–2759. doi: 10.1021/jo020698u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

General experimental procedures and selected 1H-, 13C-, 19F- and 2D NMR spectra. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.