Abstract

Objectives. We explored the emergence and effectiveness of Venezuela's Misión Barrio Adentro, “Inside the Neighborhood Mission,” a program designed to improve access to health care among underserved residents of the country, hoping to draw lessons to apply to future attempts to address acute health disparities.

Methods. We conducted our study in 3 capital-region neighborhoods, 2 small cities, and 2 rural areas, combining systematic observations with interviews of 221 residents, 41 health professionals, and 28 government officials. We surveyed 177 female and 91 male heads of household.

Results. Interviews suggested that Misión Barrio Adentro emerged from creative interactions between policymakers, clinicians, community workers, and residents, adopting flexible, problem-solving strategies. In addition, data indicated that egalitarian physician–patient relationships and the direct involvement of local health committees overcame distrust and generated popular support for the program. Media and opposition antagonism complicated physicians’ lives and clinical practices but heightened the program's visibility.

Conclusions. Top-down and bottom-up efforts are less effective than “horizontal” collaborations between professionals and residents in underserved communities. Direct, local involvement can generate creative and dynamic efforts to address acute health disparities in these areas.

Misión Barrio Adentro (MBA; “Inside the Neighborhood Mission”) in Venezuela is one of the most striking examples of Latin American social medicine (LASM). With its origins in 19th-century European social medicine, particularly the work of Rudolf Virchow, LASM took root in Chile in the early 20th century and had become well established there by the 1930s. LASM, which had also taken root in Argentina and Ecuador by that time, became prominent in other areas of Latin America in the 1960s and 1970s.1 LASM scholars and practitioners endorse collective rather than individual approaches to health care, stress the importance of political–economic and social determinants of health, and promote holistic approaches to health–disease–health care processes.2 A related perspective that scrutinizes epidemiological categories and measures—“critical epidemiology”3—stresses attention to the factors that produce health inequities rather than descriptions and analyses of observed disparities.4

For example, rather than observing that rates of infant mortality are higher in a particular minority group and analyzing individual risk factors, LASM and critical epidemiology scholars would document race- and class-based differences in access to health care, sanitary infrastructures, employment, and political representation and how they might produce higher levels of morbidity and mortality. These scholars promote practices and policies that treat health as a social and human right and extend universal and equal health care access, oppose the privatization of health and its transformation into a free-market commodity, and advocate strengthening the state's role in guaranteeing access to health services.5 A number of researchers and policymakers have reported on their efforts to convert LASM principles into practice in administering municipal and national public health systems.6,7

In Mexico, although substantial gains in health services were made during the 1970s and 1980s, national health policies of the 1990s decreased state investment in health care in favor of the private sector; growing social inequality negatively affected the ability of the poor to pay for services.8 In 2000, Asa Cristina Laurell,9 a leading critic of market-oriented health policies, became secretary of health for Mexico City mayor Andrés Manuel López Obrador's Party of the Democratic Revolution government. At the same time that market-oriented policies dominated nationally in Mexico, Obrador's party prioritized health in developing strong social welfare institutions and providing free health care for the city's 8.5 million inhabitants. The party defined health as a social right and increased the health budget by 67% in its first year in office.7

Similarly, in Uruguay, from the 1990s to 2005, metropolitan and national governments adopted health policies based on LASM and free-market principles, respectively. When Broad Front leader and oncologist Tabaré Vázquez, mayor of Montevideo from 1990 to 1995, became president in 2005, his government enacted LASM-oriented policies based on equity and justice in health—deemed to be a social right—and decentralized health institutions, integrating health services with local governments and fostering neighborhood participation.10 As an example of local-level policies, LASM has been the dominant model in the Argentinean city of Rosario since 1995. In that city, local teams have worked with residents “to guarantee that all decisions are made as closely as possible to the level of the people directly affected.”11(p233)

We studied how access to health care was extended to millions of formerly underserved Venezuelans through the various programs and policies instituted during the “Bolivarian revolution” (named for Simón Bolívar, who led Venezuela's war of independence), initiated by the left-leaning government of President Hugo Chávez Frías in 1999. In Venezuela, the public health gains achieved in previous decades had eroded during the 1980s and 1990s, as was evident in the falling percentage of the gross domestic product spent on health and the decaying health infrastructure. When the majority of health expenditures were transferred to the private sector, the poor, whose economic position had weakened, faced large fees for many health services and medications.12,13 By the late 1990s, class-based health disparities were enormous and much of the population effectively lacked access to health care.

The health policies of Chávez's government shaped the 1999 Bolivarian constitution, which declared that “health is a fundamental social right [and an] obligation of the State” and that the public health system must be “decentralized and participatory … guided by the principles of free-cost, universal availability, intersectoriality, equity, social integration, and solidarity.”14 Chávez initially appointed Gilberto Rodríguez Ochoa as health minister in 1999; María Lourdes Urbaneja, past president of the Latin American Social Medicine Association, took over the post in 2001.

Both Ochoa and Urbaneja attempted to translate LASM principles into policies and practices.15 Nevertheless, these policies and practices were largely ineffectual in transforming the Ministry of Health and providing adequate health care for the 50% of Venezuelans living in poverty.16 The Venezuelan Medical Federation was aligned with the traditional political parties that lost power in the 1990s, and many members who worked in the private health sector opposed Chávez's emphasis on reinvesting in public health. The federation's hostility toward Chávez and an opposition-led coup and oil strike were important factors leading to the failure to implement LASM principles. In spite of their pro-poor orientation, policies continued to be generated within the Ministry of Health in a top-down fashion rather than being worked out collaboratively with underserved sectors. Thus, at the same time that new policies failed to gain much support from middle-class physicians, they did not resonate deeply with the concerns and perspectives of the vast ranks of the poor.17

One local jurisdiction in Caracas, Libertador Municipality, faced pressing social problems in some of its poorest neighborhoods (or barrios); as a result of this situation, Libertador, which was aligned with Chávez, created the Institute for Endogenous Development (IED) in 2003. IED was established to foster social programs confronting living conditions in the municipality. In this effort, sociologist Rubén Alayón collaborated with community workers to survey barrio residents on their perceptions of problems in the areas of housing, health care, education, food security, and employment. Residents identified health care as their greatest concern and detailed institutional, transportation, and security barriers to obtaining medical treatment, especially during nighttime hours.18 Community leaders, residents, and IED workers were equal participants in these discussions, and they collaborated on a proposal to recruit physicians who would live in poor neighborhoods and provide free health care and to involve residents directly in any changes instituted.

IED presented the information gathered to Freddy Bernal, mayor of the Libertador Municipality, who issued a call for physicians to live and work in poor neighborhoods. Fifty Venezuelan physicians responded, but they declined to live in barrios (30 left immediately upon learning that they would be required to live in barrios; the remaining 20 participated but were assigned to provide secondary care and thus were not required to live in barrios).19 Recalling Cuban doctors who provided emergency care after the tragic mudslides of 1999 and remained as health care providers in some neighborhoods, Bernal initiated discussions with the Cuban Embassy that yielded an agreement to bring to Libertador a group of Cuban physicians who would provide the clinical services needed for the creation of what came to be known as Plan Barrio Adentro. The Cubans were trained in general integrated medicine—a specialty emphasizing familial, community, and environmental contexts and a critical approach to the intersection between biological, epidemiological, social, and humanitarian dimensions—as well as other specialties.20 Community workers assisted residents in forming neighborhood health committees.

When the first 58 physicians arrived in April 2003, they were placed in homes and used the same space as a living area and examining room. Two additional groups of physicians followed. Health committees accompanied physicians on afternoon house-to-house visits—meeting families, assessing health needs, treating patients, and conducting censuses—as well as on emergency house calls. Committees, whose members included many individuals without previous leadership experience, assumed active roles in fostering prevention, enhancing health infrastructures, and procuring resources.

By December 2003, Plan Barrio Adentro was so popular that Chávez transformed it into a national plan based on the same basic features, and the program was renamed Mission Barrio Adentro.19 MBA inaugurated a network of “missions,” broad social programs focusing on such issues as education, culture, homelessness, housing, and food security.21 As of December 2006, MBA included 23 789 Cuban doctors, dental specialists, optometrists, nurses, and other personnel22 and more than 6500 sites where patients were seen. By July 2007, 2804 primary care stations23 were being staffed by physicians, community health workers, and health promoters. Sports professionals created dance and exercise classes for the elderly, and physicians provided more than 100 types of free medications. According to our interviews and observations, mental health issues have not been prioritized.

A second phase, initiated in 2004, included 319 integrated diagnostic centers, 430 integrated rehabilitation centers, and 15 high-technology centers as of 2007.23 Some facilities were located in higher income areas. A third phase is under way that involves upgrading hospitals. The fourth phase focuses on building 15 new public hospitals, of which the Dr Gilberto Rodríguez Ochoa Latin American Children's Cardiology Hospital is the most notable example.

From the start, MBA was a major focus of criticism from those opposing the Chávez government's pro-poor policies. The Venezuelan Medical Federation claimed that the Cubans were not physicians and that they “prescribe[d] dangerous, outdated medicines.”24(p1874) Opposition media suggested that “cases of malpractice by the [Cuban] doctors continue to create uncertainty among the population,”25(p14) and “they seem to be more herbalists than professionals—they mainly prescribe the sort of brews seen in this country in the 1930s.”26(p22)

Our study built on previous assessments of LASM and critical epidemiology and accounts of the transformation of LASM theories into policies and practices. We used a detailed case study to analyze the complexities that arose in efforts in Venezuela to translate LASM theories into policy and policy into practice. Previous research had documented the depth of health disparities in Venezuela, their roots in race and class inequalities,27 the effects of policies instituted in the 1980s and 1990s on health care services and sanitary infrastructures,12 and MBA's place in health and social policies.28 We viewed MBA in the context of obstacles facing previous attempts (during 1999–2003) by Chávez's government to transform the public health system and examined ethnographically how these impediments were overcome through involving poor communities and community workers in the planning and implementation of the Cuban physician program.

Interviews with professionals and residents who participated directly in the early stages of the project enabled us to pinpoint factors that generated extensive popular support in poor communities, in spite of widespread attacks by the anti-Chávez opposition and the media. Given the crucial role of some 24 000 Cuban health professionals, our ethnographic approach enabled us to complement our primary focus on the participation of low-income residents with information on how the involvement of Cuban doctors abroad29,30 translated into day-to-day interactions with communities.

METHODS

In August 2004, we returned to low-income areas in Venezuela where we had previously conducted ethnographic research for nearly 2 decades. We contacted MBA and Ministry of Health officials, as well as members of the opposition, and we visited MBA facilities. Preliminary interviews and observations in these sites informed the design of our study.

In June through August 2005, accompanied by 2 US-based students, we conducted research in a mixed working-class/middle-class community, Santa Teresa, and impoverished hillside communities and large housing projects in the 23 de Enero barrio, near the center of Caracas. Along with the students, we conducted observations and interviews in MBA and Ministry of Health clinics and interviewed residents in their homes and in public spaces. We also conducted interviews and ethnographic observations in ministry and local government offices that focused on MBA and other health programs and documented meetings, rallies, and other events.

In June through August 2006, we worked with 3 US-based graduate students and 3 Venezuelan assistants. During this period, the interview instrument was further refined on the basis of the previous year's results. Research continued in the 2 communities, MBA facilities, and government offices, providing greater ethnographic depth, filling gaps in the data, and allowing us to assess how perceptions and participation had changed from 2005 to 2006.

The research team also worked in La Guaira and Naiguatá (large and small communities, respectively, in coastal Vargas State) and in Morón and Alpargatón (a small city and a semirural area, respectively, in the central state of Carabobo). Adding these sites expanded data on MBA implementation and community responses in different areas of the country and in communities of different sizes. We also spent 1 week in a rainforest area of Delta Amacuro State. We surveyed 270 heads of household in Santa Teresa, 23 de Enero, La Guaira, Naiguatá, Morón, and Alpargatón in August 2006. During 2005 through 2007, we made a total of 4 additional visits of 1 to 2 weeks in duration.

Our study was independent of government institutions and both governing and opposition parties. One of the study's strengths was its mix of quantitative and qualitative methodology, with an emphasis on ethnographic observation and interviewing.

Interview Details

Team members interviewed 221 residents, 41 health professionals, and 28 government employees. In each community, we stratified residents according to their age, gender, degree and type of involvement in MBA, and political affiliation. We did not select only individuals suggested by MBA personnel but used ethnographic observations to identify potential interviewees. We thereby avoided a potential source of bias—exclusion of perspectives that contrasted with those of members of health committees and MBA personnel—and obtained a broad range of responses.

We conducted additional interviews in Caracas and in Maracay (Aragua State), Timote (Mérida State), and Los Robles (Nueva Esparta State). Potential interviewees were approached in person and occasionally via telephone; all interviews were conducted in person and tape recorded. Interviews were semistructured and were an average of 32 minutes in length.

We developed instruments based on our 2004 preliminary research in collaboration with community members, clinicians, and administrators. The instrument administered to residents focused on demographic information, experience in using health services before and after 2003, involvement with MBA, perspectives on Cuban doctors, use of other government services, and media consumption. We developed different instruments for Cuban and Venezuelan health professionals; in addition to questions regarding professional training, perceptions of health conditions and MBA, objectives, and experiences working with low-income communities, Cuban interviewees were asked about their motives for and experiences living and working in Venezuela.

Ethnographic Observations and Documentary Research

Members of the research team conducted systematic observations at neighborhood and clinic sites at which MBA physicians provided primary health care, focusing on qualitative descriptions of social interactions in waiting rooms and the role of health professionals and health committees in structuring intakes and clinical interactions. The researchers accompanied committee members on household visits, noting the types of information they exchanged with household residents.

Tape recordings, photographs, and notes assisted us in documenting public meetings and events, especially health committee meetings, meetings between committees members and other residents, and meetings between committees and health professionals or administrators; these interactions focused on planning, gathering of necessary resources, health promotion and education, and prevention. Political rallies were documented. Observations of daily interactions in homes and public spaces permitted assessments of broader patterns of social interaction, social relations, political organization, and the expression of priorities and social concerns. Principal sites were visited by multiple ethnographers to cross-check data. Documentary materials included media coverage, photographs, official documents, Web sites, and video documentaries.

Survey

We surveyed 270 heads of household (177 women and 91 men—in 2 cases the respondent's gender was not recorded) in the areas studied (with the exception of Delta Amacuro State) by sampling every 10th house in blocks selected at random. Surveys focused on health care use; assessments of MBA and Cuban physicians; participation in health committees; differences and similarities between private, MBA, and Ministry of Health services; definitions of health; media consumption; and political views. Given the emphasis on these issues rather than health conditions or outcomes, it proved necessary to develop our own survey instrument, drawing on ethnographic observations and interviews.

Data Analysis

After native speakers of Venezuelan Spanish transcribed recordings, team members analyzed transcripts of interviews and meetings, photographs, field notes, and documentary materials separately. We converted recurrent keywords and themes into codes and used NUD*IST version N7 software (QSR International, Cambridge, MA) and visual inspection to identify the sentence fragment types in which these key terms and themes appeared, such as definitions of health, accounts of the origin of MBA, and perceptions of its efficacy and effects.

From the transcripts of interviews, passages dealing with key terms and themes were stratified through an inductive procedure designed to reveal participants’ full range of perspectives on key issues and their relative frequency. The data obtained were not mediated by conceptual operations or definitions and were not measured via structural instruments.

We translated and backtranslated selected texts. The Survey Research Center of the University of California, Berkeley, double coded and cross checked survey data and calculated frequency distributions; data were treated as descriptive statistics rather than being used for tests of significance. The mix of qualitative and quantitative data gathered aided our understanding of MBA and perceptions of the program as opposed to predicting health outcomes.

RESULTS

Professionals involved in the discussions that resulted in Plan Barrio Adentro reported that, unlike previous efforts, the program emerged from planning undertaken in underserved communities. Interviews with the planners, officials, community workers, and residents involved suggested that the planning process, rather than being “top-down” or “bottom-up,” was “horizontal,” resulting from creative discussions between academics, officials, and residents. When the first 58 Cuban physicians arrived, many residents reported that they were astonished that these doctors would live in poor neighborhoods and share the daily lives of residents. Interviews indicated that positive, egalitarian doctor–patient relationships and 24-hour availability of free medical care engendered widespread acceptance and other neighborhoods’ petitions for Cuban doctors.

Community workers noted that they came from poor backgrounds; most had obtained university degrees that, although not required, enabled them to provide cultural translations across class lines so that residents of low-income communities and government officials could develop common frames of reference and goals. Interviewees agreed that planning and implementation were ongoing and that residents were directly involved. A woman who hosted one of the first physicians illustrated this collaborative problem solving:

The doctor said to me, “I need a cot.” I said to him, “And where am I going to get a cot? I can find you a tabletop, and we'll use some beer crates, and that will make a cot.” And we put on a mattress and sheets, and he saw his patients there just fine.

Our data indicated that, from presidential statements and national policies to clinic visits and health committee interventions, patients received the same messages about health as “a fundamental social right,” about preventive medicine, and about community participation, thereby minimizing discrepant understandings.31 Crucially, residents reported that physician–patient interactions reflected an egalitarian attitude that fostered participation. According to one patient:

They treat you marvelously well—“Come over here, have a seat, what's wrong?” “Look, I have this.” “Ah ha, you need an x-ray, right away.” … Look, if they treat you the way that you should be treated, it makes you want to go to the clinic.

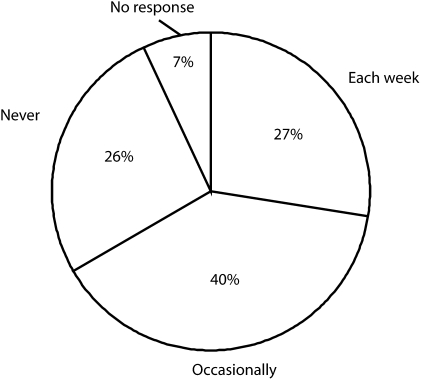

Our analysis of broadcasts of Chávez's weekly radio–television program (Aló, Presidente) indicated that the president often reiterated LASM principles and acted as a health promoter. “You've got to breastfeed her,” he exhorted a mother, “we're doing a breastfeeding campaign—this is World Breastfeeding Week.” As shown in Figure 1, 27% of those surveyed reported that they watched or listened to the Chávez broadcasts weekly, and 40% indicated that they did so “occasionally.”

FIGURE 1.

Frequency of respondents’ watching or listening to President Chávez's radio–television program, Aló, Presidente.

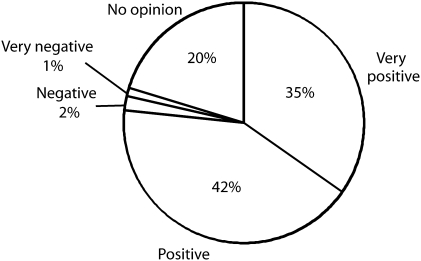

Health planners involved in Plan Barrio Adentro and the early stages of MBA stressed that pro-poor, rights-oriented principles also emerged in other missions—large-scale public projects that addressed the needs of low-income Venezuelans and focused on food security, literacy, education, housing, and employment—providing the “integrative” frame for health care advocated by LASM. Figure 2 shows that 35% of the individuals we surveyed believed that the MBA and other missions had produced “very positive changes,” and 42% believed that they had produced “positive” changes; only 3% believed that they had led to “negative” or “very negative” changes.

FIGURE 2.

Respondents’ assessments of changes produced by Mission Barrio Adentro.

Opposition physician Mariana Ortíz said of her Venezuelan colleagues, “MBA is viewed quite negatively; it's seen as competition for [Ministry of Health] hospitals and [private] clinics.” Interviews with laypersons and health professionals aligned with both the opposition and the government suggested that such criticisms resulted in MBA being a major test of Chávez's government. Interviews and media analyses indicated that the intense antagonism of the Chávez opposition had the unintended consequences of raising MBA's visibility and, once it gained extensive popular participation, enhancing Chávez's popularity. Health professionals who worked with MBA reported that opposition supporters sometimes blocked ambulances and banged pots and pans, scaring patients. Our interviews in working-class communities suggested that MBA crucially influenced Chavez's 59% to 41% victory in the 2004 presidential recall referendum. The officials we interviewed indicated that these electoral results led the government to make MBA a top priority and invest considerable resources.

Most residents of poor neighborhoods reported that they viewed MBA as “their” program; Ministry of Health efforts to exert limited control were sometimes resisted as meddling on the part of out-of-touch bureaucrats. Interviewees occasionally complained that health committees distributed resources unfairly and limited the participation of opposition supporters, although other residents disputed these claims. Ethnographic research and interviews conducted in Delta Amacuro State suggested that, in some areas, roadblocks placed by regional governments, the weakness of social movements, or, as in Delta Amacuro's rainforest, low population density limited MBA's popular reception and institutional growth.

Many middle-class Venezuelans, even Chávez supporters, characterized MBA as a program “for the poor.” Some residents repeated opposition criticisms of Cuban professionals and heeded calls to boycott the MBA. Opposition supporters reported that they sometimes used MBA facilities in emergencies, e.g., to avoid a long trip, or when doctors in private clinics prescribed expensive tests or procedures. Some supported MBA whereas others remained distrustful. Interviews with opposition politicians and media analyses indicated that, beginning in 2005, anti-Chávez criticism focused more on the perceived failure of MBA to deliver services than on elimination of the program. In the 2006 presidential campaign, opposition politicians promised to improve rather than dismantle MBA.

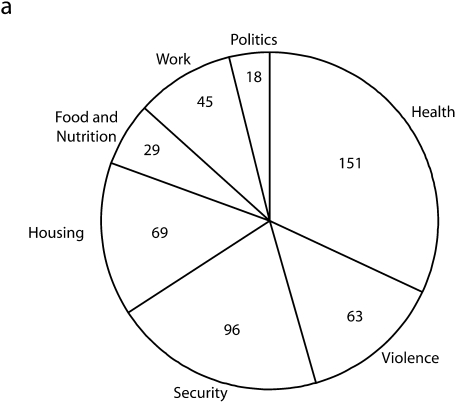

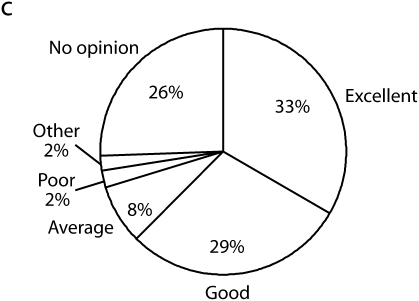

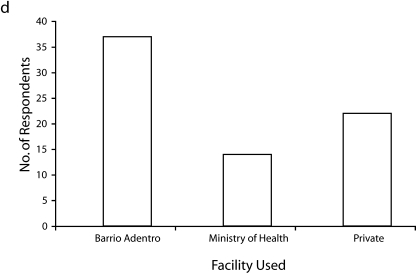

Descriptive survey data are reported in Figure 3. Half of the individuals surveyed were high school graduates; 17% had gone on to higher education. Respondents ranged in age from 17 to 86 years and were widely distributed within that range. Forty-eight percent backed Chávez, 10% supported opposition parties, and 36% listed no political alignment. As shown in Figure 3a, 151 of 270 respondents listed health as their greatest concern. (The overall focus of the survey on health probably influenced this result.)

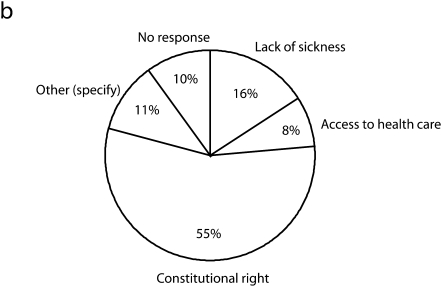

FIGURE 3.

Descriptive survey data showing (a) the number of respondents listing primary concerns in 1 or 2 of 7 areas (sample size is n > 270), (b) respondents’ definitions of health, (c) respondents’ assessments of the quality of Mission Barrio Adentro services, and (d) respondents’ use of Mission Barrio Adentro, Ministry of Health, and private facilities.

Figure 3b shows that 55% of the respondents defined health as a constitutional right, as opposed to the absence of sickness (16%) or access to health care (8%). Figure 3c shows that 62% rated MBA services as “excellent” or “good,” whereas 10% assessed them as “average” or “poor.” In addition, 51.3% reported that an MBA facility was located within a walking distance of 5 minutes. Finally, as shown in Figure 3d, 37% of the respondents reported that family members had used MBA services during the past year, as compared with 22% using private institutions and 14% using Ministry of Health facilities. Eleven percent of the respondents served on health committees.

DISCUSSION

Some elements of MBA reflect the specific circumstances of recent Venezuelan history, particularly the policies of and opposition to the Chávez government; Venezuela's abundant oil revenues, which provided the substantial resources needed to build the program; and the extensive cooperation between Cuba and Venezuela, with Venezuelan oil being sent to Cuba and Cuban doctors being sent to Venezuela. However, as discussed next, several key issues affecting the project's future remain unclear.

Some politicians have suggested subordinating health committees to community councils, which have broad administrative duties and manage resources distributed by the government to communities; if this occurs, their autonomy and effectiveness will probably diminish. As Cuban physicians become less available, will Venezuelan physicians trained through the MBA in general integrative medicine overcome middle-class perceptions of barrios as spaces of criminality and chaos, put aside their material aspirations, and choose to live there? If not, will the MBA maintain popular support and involvement? Training low-income Venezuelans as physicians may prove crucial in the long run if graduates are willing to stay in their communities. MBA was intended to transform the public health system as a whole,17 but Venezuela has not accomplished this goal as of yet. Nevertheless, our study affords a number of valuable insights.

First, the discussions that gave rise to Plan Barrio Adentro suggest that devising plans for ameliorating acute health disparities can benefit from in-depth discussions joining research and theory with underserved communities’ in-depth knowledge of their problems and possible solutions. Top-down and bottom-up perspectives are inadequate; effective interventions emerge through synthesizing academic, policy, and grassroots perspectives in a “horizontal” approach. The most significant components of the planning phase can best be undertaken in affected areas. Second, our findings regarding the crucial role of health committees in continuing to shape MBA at both the local and national levels indicate that direct local involvement and creative, flexible problem-solving approaches should continue throughout the life of the program, no matter how large its scale.

Third, medicine and public health generally seek to eschew overtly political orientations; nevertheless, the importance of political support for MBA gained after the 2004 presidential recall referendum in Venezuela suggests that when interventions become major sources of political support, leaders are more likely to make health a political and budgetary priority. The extensive media coverage, both positive and negative, focused on MBA greatly increased its visibility, but additional examples are needed to assess the effects of media coverage on funding and community support for efforts intended to address acute health inequities.

Fourth, although nonprofessional health promoters participated in day-to-day MBA clinical and preventive activities, community workers—who came from underserved communities but obtained university training—played a crucial role in the creation of Barrio Adentro. Thus, we recommend that efforts to train health workers for programs targeting acute health disparities include individuals whose class backgrounds and educational achievement enable them to negotiate underserved communities and spaces dominated by professionals. Such individuals can foster creativity and innovation, deeper knowledge bases, more effective communication, and strong interinstitutional linkages, particularly in the initial planning and implementation phases.

Finally, the observed role of positive, egalitarian clinical interactions between Cuban physicians and Venezuelan patients and other residents suggests that doctor–patient interactions model power relations between communities and institutions and affect local perceptions and participation. Decreasing the social distance between physicians and patients can lead to new forms of cooperation and problem solving. Creating more positive, egalitarian physician–patient and professional–community relationships may be one of the easiest, most effective ways clinicians can contribute to overcoming health disparities.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Salus Mundi Foundation of Tucson, AZ.

We deeply appreciate the participation of community members, health committees, and Venezuelan and Cuban health professionals in this study. Alexandra Anastasopulos, Renée Asturias Peñalosa, Amy Cooper, Amy Gardner, Silvia Gómez, Andreina Gúia, Xochitl Marsilli Vargas, Claire Mertz, Thomas Ordóñez, Ángela Pinto, Carmen Rojas, Megan Strom, Carina Vance, and Erick Valero participated as research assistants. Jaime Breilh, Lemyra DeBruyn, Carson Henderson, Asa Cristina Laurell, Mark Nichter, and Howard Waitzkin provided valuable comments on previous versions.

Human Participant Protection

This study was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of California, San Diego, and the University of California, Berkeley. Participants provided verbal informed consent.

References

- 1.Waitzkin H, Iriart C, Estrada A, et al. Social medicine then and now: lessons from Latin America. Am J Public Health 2001;91:1592–1601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Menéndez EL, Di Pardo RB. De Algunos Alcoholismos y Algunos Saberes: Atención Primaria y Proceso de Alcoholización Mexico City, Mexico: CIESAS; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Almeida Filho N. Epidemiologia sem números: Uma introdução à ciência epidemiológica Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Campus; 1981 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breilh J. Epidemiología Crítica: Ciencia Emancipadora e Interculturalidad. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Lugar Editorial; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamada S. Latin American social medicine and global social medicine. Am J Public Health 2003;93:1994–1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breilh J, ed. Informe Alternativo sobre la Salud en América Latina Quito, Ecuador: Centro de Estudios y Asesoría en Salud; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laurell AC. What does Latin American social medicine do when it governs? The case of the Mexico City government. Am J Public Health 2003;93:2028–2031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laurell AC. Health reform in Mexico: the promotion of inequality. Int J Health Serv 2001;31:291–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laurell AC. La Reforma contra la Salud y la Seguridad Social: Una Mirada Crítica y Una Propuesta Alternativa. Mexico City, Mexico: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, Ediciones Era; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernández M, Curto S. Uruguay: Participación social en salud y el papel de la epidemiología. In: Breilh J, ed. Informe Alternativo sobre la Salud en América Latina Quito, Ecuador: Centro de Estudios y Asesoría en Salud; 2005:214–219 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fein M, Ferrandini D. Equidad real en la oferta pública en la salud: el norte de un gobierno municipal democrático. In: Breilh J, ed. Informe Alternativo sobre la Salud en América Latina Quito, Ecuador: Centro de Estudios y Asesoría en Salud; 2005:223 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaén MH. El Sistema de Salud en Venezuela: Desafíos Caracas, Venezuela: IESA; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Urbaneja ML. Privatización en el Sector Salud en Venezuela Caracas, Venezuela: CENDES; 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Constitution of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela. Gaceta Oficial 36,860, December 30, 1999, Articles 83 and 84 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plan Estratégico Social. Caracas, Venezuela: Ministerio de Salud y Desarrollo Social; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Instituto Nacional de Estadística Summary of social indicators 1997–2008 [translation]. Available at: http://www.ine.gob.ve. Accessed June 9, 2008

- 17.Alvarado CH, Martínez ME, Vivas-Martínez S, Gutiérrez NJ, Metzger W. Cambio social y política de salud en Venezuela. Medicina Social 2008;3:113–129 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alayón Monserat R. Barrio Adentro: combatir la exclusión profundizando la democracia. Rev Venez Econ Ciencias Soc 2005;11:241 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Defensoria del Pueblo Síntesis del Plan Barrio Adentro, 2003. Available at: http://www.defensoria.gob.ve/lista.asp?sec=190702&txt=barrio%20adentro. Accessed July 3, 2007

- 20.Barrio Adentro: Derecho a la Salud e Inserción Social en Venezuela. Caracas, Venezuela: Pan American Health Organization; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 21.D'Elia Y, ed. Las Misiones Sociales en Venezuela: Una Aproximación a Su Comprensión y Análisis. Quito, Ecuador: Instituto Latinoamericano de Investigaciones Sociales; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gobierno Bolivariano de Venezuela Programas sociales: Misión Barrio Adentro I. Available at: http://minci.gob.ve/sociales/20/10398/mision_barrio_adentro.html. Accessed March 27, 2007

- 23.Informe General Misiones Barrio Adentro. Caracas, Venezuela: Gobierno Bolivariano de Venezuela; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ceaser M. Cuban doctors provide care in Venezuela's barrios. Lancet 2004;363:1874–1875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matheus R. Murió una niña tratada por un médico cubano. Diario 2001. July 11, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salazar Leídenz M. Los médicos brujos. Diario 2001. July 20, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Briggs CL, Mantini-Briggs C. Stories in the Time of Cholera: Racial Profiling During a Medical Nightmare. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muntaner C, Guerra Salazar RM, Benach J, Armada F. Venezuela's Barrio Adentro: an alternative to neoliberalism in health care. Int J Health Serv 2006;36:803–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grundy PH, Budetti PP. The distribution and supply of Cuban medical personnel in Third World countries. Am J Public Health 1980;70:717–719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carrillo de Albornoz S. On a mission: how Cuba uses its doctors abroad. BMJ 2006;333:464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Getrich C, Heying S, Willging C, Waitzkin H. An ethnography of clinic “noise” in a community-based, promotora-centered mental health intervention. Soc Sci Med 2007;65:319–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]