Abstract

Objectives. We examined the relationship between psychosocial antecedents in earlier adolescence and problems related to substance use and related adverse health consequence (e.g., respiratory diseases, neurocognitive symptoms, and general malaise) in adulthood. We specifically focused on parent–child bonding in earlier adolescence and internalizing behaviors in later adolescence and their effects on problems related to substance use in the mid-20s and health problems in the mid-30s.

Methods. Our team interviewed a community-based sample of 502 participants over a 30-year period (1975, 1983, 1985–1986, 1997, 2002, and 2005).

Results. We found a strong relationship between internalizing behaviors in later adolescence and adverse health consequences in the mid-30s. Internalizing behaviors in later adolescence served as a mediator between low parent–child bonding in earlier adolescence and later adverse health consequences. Problems related to substance use in the late 20s and early 30s were related directly to later adverse health consequences and indirectly as mediators between earlier psychosocial difficulties (i.e., internalizing behaviors, externalizing behaviors, poor ego integration, and maladaptive coping) and later adverse health consequences.

Conclusions. Policies and programs that address parent–child bonding and internalizing behaviors should be created to reduce problems related to substance use and, ultimately, later health problems.

Use of tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drugs adversely affects the health of US adults. Smoking is the leading cause of death in the United States; alcohol abuse is the third leading cause of death.1–4 Marijuana is the most commonly used illicit drug.5,6 Smoking, alcohol use, and marijuana use are associated with overall adverse health consequences such as respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer.1–6 Alcohol and marijuana use also affect neurological health, resulting in impaired short-term memory and learning difficulties.4,5 In Healthy People 2010, the federal government clearly prioritized tobacco use, alcohol and drug abuse, physical health, and mental health as national public health concerns and established goals for disease prevention and health promotion to be reached by the year 2010.7

There is evidence that health status and outcomes are affected by the quality of early personal relationships, particularly parent–child bonding.8–10 The literature also suggests that internalizing behaviors and problems related to substance use are associated with an increased risk for later health problems.11

We examined the pathway from parent–child bonding during adolescence to health in the mid-30s, specifically neurocognitive health, respiratory health, and general malaise.

We identified 3 types of early psychosocial precursors related to later health outcomes: parent–child bonding (identification with parents, parent–child centeredness, and parental affection), internalizing behaviors (anxiety, depression, interpersonal difficulties, low ego-integration, and maladaptive coping with internal stressors), and problems related to substance use.

On the basis of the empirical literature and family interactional theory (FIT), we hypothesized that in earlier adolescence low parent–child bonding, characterized by lack of affection or support from parents, predicts internalizing behaviors.12–15 In addition, only a few studies have explored the long-term relationships between internalizing behaviors in earlier adolescence and health in the fourth decade of life. Recent research based on the Terman Life-Cycle Study supports the general relationship between aspects of personality in childhood and health in adulthood.8–10,16 Based on these studies, we further hypothesized that low parent–child bonding and internalizing behaviors are significantly associated with later adverse health consequences.

Besides the empirical literature, our hypotheses are derived from FIT.15 FIT emphasizes the importance of the early attachment between parent and child. Effective parent–child bonding is characterized by affection, child-centeredness, and minimal parent–child conflict. In addition, a strong attachment is characterized by the child identifying with parental values (e.g., conventional beliefs and values). Such a strong bond between the parent and child protects against the child's development of 2 behaviors that have been identified in the literature, namely, internalizing behaviors (e.g., depression and anxiety)11,17 and externalizing behaviors expressed in nonconventional forms of behavior (e.g., illicit drug use).18,19 Externalizing behaviors in the late 20s and early 30s are continuations of behaviors developed during adolescence. According to FIT, mutual parent–child bonding characterized by affection is associated with adaptive intrapersonal functioning, insulating the adolescent from smoking and abusing alcohol and drugs.17,20,21

In recent years, our research group has applied FIT concepts to predicting tobacco use in adulthood. We have used FIT in analyses designed to assess the developmental pathways with regard to predictors of cigarette use and smoking cessation.22,23 FIT has served as an organizing perspective for our measures of parental bonding, internalizing and externalizing behaviors, and the stability of these dimensions over time.

On the basis of FIT and the empirical literature cited above, we hypothesized the following: Difficulty in parent–child bonding during earlier adolescence is related to internalizing behaviors in later adolescence. In turn, both difficulty in parent–child bonding and internalizing behaviors are linked to problems related to substance use in the late 20s and early 30s. Finally, problems related to substance use in the late 20s and early 30s are related to adverse health consequences in the mid-30s. In addition, we hypothesized that internalizing behaviors have a direct adverse effect on health.

METHODS

Participants and Procedure

Participant data were obtained from a randomly selected cohort first studied in 1975 and then followed from 1983 to 2005. The families in this study were generally representative of the population of families in the northeast United States in 1975 when the initial wave of the data was collected. Our team initially collected data in Albany and Saratoga counties in New York; subsequent waves of data collection were done in participants’ homes wherever they lived at the time of the follow-up wave. Families in both locations in 1975 were similar to those surveyed nationally in the 1980s by the US Census Bureau with respect to gender, education, family income, and family structure. For example, 75% of the children lived with married parents, and 19% lived with a mother who was not currently married; the 1980 census figures were 79% and 17%, respectively. We collected follow-up data in the participants’ homes in 1983 (n = 756; earlier adolescence [ages 9–12 years; mean age = 14.05 ±2.80]), 1985 through 1986 (n = 739; later adolescence [ages 11–21 years, mean age = 16.26 ±2.81]), 1997 (n = 749; late 20s [ages 22–32 years, mean age = 26.99 ±2.80]), 2002 (n = 673; early 30s [ages 27–37 years, mean age = 32.00 ±2.84]), and 2005 (n = 502; mid-30s [ages 30–40 years, mean age = 35.08 ±2.99]).

Extensively trained and supervised lay interviewers administered the interviews in private. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants and their mothers in 1975, 1983, and 1985 through 1986, and from the participants only in 1997, 2002, and 2005. For more details about the sampling procedures and the original sample, see Cohen and Cohen,24 and Brook et al.15

The sample of 502 participants interviewed during their mid-30s represented a random sample of the 673 participants who participated in the study during their early 30s. There were no significant age differences on the psychosocial measures between those who participated during their early 30s and remained in the study during their mid-30s and those who were not included during their mid-30s (t = 0.78; P > .05). However, there were differences for gender and parental education (t = 2.57, P < .05 and t = –2.80, P < .05, respectively). We controlled for gender, age, and parental education in our analysis.

Our analysis included 500 participants (2 participants were excluded because of missing health variables during their mid-30s). Complete data was provided by 435 (87%) participants; less than 5% of the participants failed to provide values on 1 or more of the independent variables. To compensate for missing data, we used the full information maximum likelihood approach, which allows parameter estimation in the presence of missing data.25

Of the adults sampled in 2005, 95% were White, 56% were female, 62% were married, and 95% had at least a high school education. The sample had a broad range of socioeconomics statuses. The median annual income in 2005 before taxes ranged from $25 000 to $34 999.

Measures

We hypothesized a latent variable of parent–child bonding during earlier adolescence (mean age 14 years). The latent variable consisted of 3 manifest variables: identification with parents, parental affection, and parental child-centeredness. Identification with parents was created by combining measures of identification with mother and father (α = 0.92; 28 items, e.g., “I admire my mother in her role as a parent in every way.”26). Parental affection was a combined measure of maternal and paternal affection (α = 0.72; 10 items, e.g., “She frequently shows her love for me.”27). Parental child-centeredness was a combined measure of maternal and paternal child-centeredness (α = 0. 80; 10 items, e.g., “She likes to talk with me and be with me much of the time.”24). Higher scores on parent–child bonding represented closer bonding, whereas lower scores represented more distance in the parent–child bond.

We hypothesized a latent variable of internalizing behaviors during later adolescence (mean age = 16 years). We assessed this variable using the following 5 measures as manifest variables for the latent construct we referred to as internalizing behaviors: (1) depression (α = 0.75; 5 items, e.g., “Over the last few years, how much were you bothered by feeling low in energy or slowed down?”28); (2) anxiety (α = 0.65; 4 items, e.g., “Over the last few years, how much were you bothered by feeling fearful?”28); (3) interpersonal difficulties (α = 0.74; 6 items, e.g., “Over the last few years, how much were you bothered by feeling easily annoyed or irritated with other people?”28); (4) ego-integration (α = 0.62, 7 items, e.g., “I generally rely on careful reasoning in making up my mind.”15); and (5) coping (α = 0.52; 4 items, e.g., “What happens to me in the future mostly depends on me.”29).

We hypothesized a latent variable of problems related to substance use during the late 20s and early 30s consisting of 8 manifest variables (tobacco use and problems related to alcohol, marijuana, and other illegal drug use in the late 20s and in the early 30s). We assessed the participants’ frequency of smoking cigarettes during the previous 5 years. The tobacco measure at each point in time had a scale coded as none (1), less than daily (2), 1 to 5 cigarettes a day (3), about half a pack a day (4), about a pack a day (5), and about 1.5 packs a day or more (6). Three 9-item measures (27 items in total) were used to assess problems related to each of the following: (1) alcohol, (2) marijuana, and (3) illegal drug use (3 manifest variables with α = 0.80–0.98; e.g., “My use of marijuana caused me to behave in ways that I later regretted.”).26 Each item had a response option of no (0) or yes (1).

We measured a latent variable of health problems in the mid-30s by assessing physical symptoms in 3 areas of health (i.e., neurocognitive, respiratory, and general malaise). Participants were asked how long a particular health problem had been a problem during the past year. Each item had a response option of not in the past year (0), 1 to 4 weeks (1), 1 to 3 months (2), and more than 3 months (3). Participants were asked 14 questions to derive 3 groups of symptoms: (1) neurocognitive symptoms (α = .71; headaches, trouble remembering things, difficulty thinking and concentrating, and trouble learning new things);26 (2) respiratory symptoms (α = .75; asthma, bronchitis or pneumonia, coughing spells, chest colds, shortness of breath when not exercising, wheezing and gasping);26 and (3) general malaise (α = .64; appetite loss, trouble getting started in the morning, trouble sleeping, and staying home most or all of the day because of not feeling well).26

Data Analysis

We used a latent variable structural equation model to examine the empirical validity of the hypothesized pathways. The structural equation model is a multivariate statistical method that evaluates both the measurement quality of a set of variables used to assess a latent construct (the measurement model) and the relationships among the latent constructs (the structural model). We attempted to account for the influence of the adolescents’ gender, age, and parental educational levels on these models. To do this, we used partial covariance matrices as the input matrices, which were created by statistically partialing out (removing the effect of the baseline measure) the effects of these demographic factors on each of the original manifest variables. This strategy afforded us a more generalizable model and allowed us to statistically control for the effects of demographic variables without postulating exactly where they influence the model. We then employed maximum likelihood methods to estimate the models by using LISREL 8 software (Scientific Software International, Chicago, IL).

To account for the nonnormal distribution of the model variables, we used the Satorra–Bentler30 scaled χ2 as the test statistic for model evaluation as recommended by Hu et al.31 We chose 3 fit indices to assess the fit of the models: (1) the LISREL goodness-of-fit index,32 (2) the root mean square error of approximation, and (3) Bentler's comparative fit index.30 According to Kelloway,33 values between 0.90 and 1.0 on the goodness-of-fit and comparative fit indices indicate that a model provides a good fit to the data; accordingly, values for the root mean square error of approximation should be below 0.10.33 The standardized total effects equals the sum of the direct and the indirect effects of each earlier latent variable (estimated in the analysis) on adverse health consequences during the mid-30s. The standardized total effects were computed to help in the interpretation of the structural coefficients.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the duration of the participants’ neurocognitive health symptoms, respiratory symptoms, and general malaise. As noted in Table 1, the health symptoms (e.g., respiratory symptoms) were somewhat skewed (percentages for 1 to 3 months were far less than the percentages for 4 weeks or less). As a result, we used the Bentler procedure to make adjustments for nonnormal distributions.

TABLE 1.

Past Year Duration of Neurocognitive, Respiratory, and General Malaise Symptoms Reported by Participants During Their Mid-30s (N = 500): 1983–2005

| Durationa |

||||

| Symptoms | Not in the Past Year, % | 1–4 Weeks, % | 1–3 Months, % | More Than 3 Months, % |

| Neurocognitive symptoms | ||||

| Headache | 43.2 | 39.7 | 9.0 | 8.1 |

| Difficulty thinking or concentrating | 75.7 | 16.8 | 4.1 | 3.4 |

| Difficulty remembering things | 80.6 | 11.3 | 3.0 | 5.1 |

| Difficulty learning new things | 93.7 | 2.8 | 1.1 | 2.4 |

| Respiratory symptoms | ||||

| Chest colds | 53.6 | 42.6 | 3.8 | 0.0 |

| Coughing spells | 75.3 | 21.3 | 2.8 | 0.6 |

| Shortness of breath when not exercising | 87.0 | 9.8 | 2.4 | 0.8 |

| Bronchitis or pneumonia | 90.2 | 8.6 | 0.2 | 1.0 |

| Asthma | 91.2 | 5.2 | 0.8 | 2.8 |

| General malaise | ||||

| Trouble sleeping | 56.0 | 26.6 | 8.8 | 8.6 |

| Staying home most or all of the day because of not feeling well | 56.1 | 39.9 | 2.2 | 2.2 |

| Trouble getting started in the morning | 63.7 | 23.9 | 6.0 | 6.4 |

| Appetite loss | 85.7 | 11.7 | 1.6 | 1.0 |

Participants were asked “How often during the past year did the following bother you?”

Using LISREL 8, we tested the measurement model as well as the structural model, partialing out the adolescents’ age, gender, and parental educational level. All factor loadings were significant (P < .001). These findings show that the indicator variables were satisfactory measures of the latent constructs. The partial covariance matrices and the information about the factor loadings from the measurement model are available from the authors upon request.

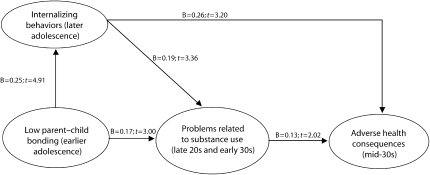

The Satorra–Bentler χ2 value was 336.23. The following fit indices were also obtained: goodness-of-fit = 0.93; root mean square error of approximation = 0.051; and Bentler's comparative fit index = 0.95. These results reflect a satisfactory model fit (as previously noted). The obtained path diagram along with the standardized regression weights are depicted in Figure 1. Low parent–child bonding during earlier adolescence was associated with internalizing behaviors in later adolescence (B = 0.25; t = 4.91) and problems related to substance use in the late 20s and early 30s (B = 0.17; t = 3.00). Internalizing behaviors in later adolescence were associated with problems related to substance use in the late 20s and early 30s (B = 0.19; t = 3.36), which in turn were directly associated with adverse health consequences in the mid-30s (B = 0.13; t = 2.02). In addition, there was a direct association between internalizing behaviors in later adolescence and adverse health consequences in the mid-30s (B = 0.26; t = 3.20).

FIGURE 1.

Obtained path diagram of adolescent and young adult (N = 500) psychosocial factors and problems related to substance use as related to adult adverse health consequences.

Note. Goodness-of-fit index = 0.93; root mean square error of approximation = 0.051; Bentler's comparative fit index = 0.95. We controlled for parental education, age, and gender. All parameter estimates were significant at P < .05 (2-tailed tests).

Table 2 shows the following standardized total effects based on a 2-tailed test: earlier adolescent low parent–child bonding (standardized total effects = 0.09; t = 3.47; P < .001), later adolescent internalizing behaviors (standardized total effects = 0.28; t = 3.44; P < .001), and problems related to substance use in the late 20s and early 30s (standardized total effects = 0.13; t = 2.02; P < .05). Thus, each earlier latent variable had a significant total effect on adverse health consequences in the mid-30s.

TABLE 2.

Standardized Total Effects of Adolescent and Young Adult (N = 500) Psychosocial Factors and Problems Related to Substance Use on Adverse Health Consequences During Mid-30s: 1983–2005

| Standardized Total Effect (t) | |

| Low parent–child bonding (earlier adolescence) | 0.09** (3.47) |

| Internalizing behaviors (later adolescence) | 0.28** (3.44) |

| Problems related to substance use (late 20s and early 30s) | 0.13* (2.02) |

P < .05;

P < .001 (2-tailed tests).

DISCUSSION

We believe our study is unique in that it examines adolescent psychosocial factors as predictors of later adverse health consequences in the mid-30s. To the best of our knowledge, our investigation is also the first longitudinal study to examine the interrelationship of adolescent psychosocial factors, problems related to substance use in the late 20s and early 30s, and adverse health consequences during the mid-30s. Our hypotheses regarding the pathways to adverse health consequences were supported.

First, there was a strong direct relationship between internalizing behaviors during adolescence and later adverse health consequences. Indeed, the relationship between internalizing behaviors and health consequences was as strong, or stronger than, the health effects of problems related to substance use (Table 2). Second, the results indicated that internalizing behaviors serve as partial mediators between low parent–child bonding and later adverse health consequences. Internalizing behaviors also mediated the relationship between low parent–child bonding and problems related to substance use. Third, earlier problems related to substance use were related to later adverse health consequences and also mediated between earlier psychosocial difficulties and later adverse health consequences. Fourth, low parent–child bonding has long-term consequences on health, given the fact that the participants’ relationships were assessed 22 years before the assessment of adverse health consequences.

FIT proposes that the effects of low parent–child bonding and adolescent maladaptive personality on adult adverse health outcomes are mediated in part by risk behaviors (problems related to substance use).34 In our study, the influence of adolescent psychosocial difficulties on later adverse health consequences was partially mediated by problems related to substance use. These results provide support for FIT and point to the possible mechanisms that operate between adolescent psychosocial attributes and adult health outcomes. Furthermore, we found both direct and indirect effects of internalizing behaviors in later adolescence on adult health. The indirect effect of internalizing behaviors on adverse health consequences emerged over the course of 2 decades, despite the opportunities for other biological and psychosocial factors to influence health outcomes.

Consistent with previous findings,16 our results showed a direct link between internalizing behaviors in adolescence and adverse health consequences in the mid-30s. It may be that these measures of internalizing behaviors were markers for more generalized stressful experiences predisposing participants to health problems.35–38

Using a community sample, our findings shed light on components of a developmental sequence over 22 years. In contrast to past research, our study combined several psychosocial influences into a single model spanning several developmental stages. In previous studies, researchers examined the separate associations between problems related to substance use and parent–child bonding,13,17,20 internalizing behaviors,17 or health, 11 respectively. Our study therefore is unique in that we examined precursors and consequences of problems related to substance use in a comprehensive structural equation model across several developmental stages. This study has the methodological advantage of having data collected from participants at different developmental periods (earlier and later adolescence, late 20s, and early and mid-30s).

Limitations

Although we can present temporal relationships among the sets of variables in our model, we cannot prove causality. For example, we examined the effects of parent–child bonding on internalizing behaviors; however, internalizing behaviors could just as likely affect parent–child bonding. Internalizing behaviors might be considered a temperamental characteristic of a child, which is at least partially if not substantially influenced by genetic factors. Some interplay between parent–child bonding and internalizing behaviors may have occurred before the child reached adolescence. Future research using in-depth studies should examine the interplay of internalizing behaviors and parent–child bonding over time.

In addition, future research should study earlier manifestations of externalizing behaviors, such as aggression. Future studies should also include more in-depth examinations of possible gender differences in the pathways to adult health that might better illuminate the relationships between internalizing behaviors (e.g., depression), externalizing behaviors (e.g., drug-using behaviors), and later health outcomes.

Conclusions

The results of this investigation provide new evidence regarding the important role that problems related to substance use play in mediating the relationship between earlier adolescent psychosocial factors and later adverse health consequences. Interventions during adolescence should focus on parent–child bonding and internalizing behaviors. Interventions during the late 20s and early 30s should focus on problems related to substance use. From both public health and clinical perspectives, creating policies and programs directed at improving parent–child bonding and reducing internalizing behaviors may be instrumental in reducing problems related to substance use and, therefore, may prevent or reduce later adverse health consequences.

There is a long and rich history of family-focused interventions that have demonstrated the importance of bonding and establishing a close positive parent–child attachment relationship. Our study provides support for the continuation of existing family-based preventive interventions that emphasize parent–child bonding.

In addition, our research gives credence to focusing on internalizing behaviors in prevention programs such as those developed by Liddle39 and Szapocznik.39 School and community prevention programs might benefit by expanding their curricula to incorporate components of parent–child bonding and attachment (e.g., family or parenting workshops) to prevent later problems related to substance use, as well as later adverse health effects. The Coping Power Program and Project STAR (Student Taught Awareness and Resistance) are examples of school and community prevention programs that include a focus on parent–child bonding and attachment components to prevent substance use.39

There is a critical need for programs directed toward preventing problems related to substance use. There is also a specific need to focus on enhancing parent–child bonding, thereby minimizing internalizing behaviors, subsequent problems related to substance use, and later adverse health consequences.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (grants K05 DA00244, and R01 DA003188-26, and CA 094845-06).

Human Participant Protection

The study was approved by the institutional review board of the New York University School of Medicine, protocol numbers 11462 (K05 DA00244), 11430 (R01 DA003188-26), and 11456 (CA 094845-06).

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking & Tobacco Use: Fact Sheet: Health Effects of Cigarette Smoking. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/Factsheets/health_effects.htm. Accessed June 28, 2007

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking & Tobacco Use: Fast Facts. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/FastFacts.htm. Accessed June 28, 2007

- 3.Centers for Disease Control. Quick Stats: General Information on Alcohol Use and Health. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/print.do?url=http://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/quickstats/general_info.htm. Accessed June 28, 2007

- 4.Mokdad A, Marks J, Stroup D, Gerberding J. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA 2004;291:1238–1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Office of National Drug Control Policy. Drug Facts: Marijuana. Available at: http://www.whitehousedrugpolicy.gov/drugfact/marijuana/index.html. Accessed June 28, 2007

- 6.Jones RT. Cardiovascular system effects of marijuana. J Clin Pharmacol 2002;42:58S–63S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: What Are the Leading Health Indicators? Available at: http://www.healthypeople.gov/LHI/lhiwhat.htm. Accessed June 28, 2007

- 8.De Benedittis G, Lorenzetti A, Pieri A. The role of stressful life events on the onset of chronic primary headache. Pain 1990;40:65–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman HS, Booth-Kewley S. The “disease-prone personality.” A meta-analytic view of the construct. Am Psychol 1987;42(6):539–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman HS, Tucker JS, Tomlinson-Keasey C, Schwartz JE, Wingard DL, Criqui MH. Does childhood personality predict longevity? J Pers Soc Psychol 1993;65:176–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conwell LS, O'Callaghan MJ, Andersen MJ, Bor W, Najman JM, Williams GM. Early adolescent smoking and a web of personal and social disadvantage. J Paediatr Child Health 2003;39:580–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allen JP, Moore C, Kuperminc G, Bell K. Attachment and adolescent psychosocial functioning. Child Dev 1998;69:1406–1419 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buist KL, Dekovic M, Meeus W, van Aken MAG. The reciprocal relationship between early adolescent attachment and internalizing and externalizing problem behavior. J Adolesc 2004;27:251–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dekovic M. Risk and protective factors in the development of problem behavior during adolescence. J Youth Adolesc 1999;28:667–685 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brook JS, Brook DW, Gordon AS, Whiteman M, Cohen P. The psychological etiology of adolescent drug use: a family interactional approach. Genet Soc Gen Psychol Monogr 1990;116:111–267 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman HS, Tucker JS, Schwartz JE, et al. Childhood conscientiousness and longevity: health behaviors and cause of death. J Pers Soc Psychol 1995;68:696–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleming CB, Kim H, Harachi TW, Catalano RF. Family processes for children in early elementary school as predictors of smoking initiation. J Adolesc Health 2002;30:184–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brook JS, Brook DW, De La Rosa M, Whiteman M, Johnson E, Montoya I. Adolescent illegal drug use: the impact of personality, family, and environmental factors. J Behav Med 2000;24:183–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brook JS, Pahl K. Predictors of drug use among South African adolescents. J Adolesc Health 2006;38:26–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Abbott RD, Guo J. Family influences on the risk of daily smoking initiation. J Adolesc Health 2005;37:202–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tucker JS, Ellickson PL, Klein DJ. Predictors of the transition to regular smoking during adolescence and young adulthood. J Adolesc Health 2003;32:314–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marcus SE, Pahl K, Ning Y, Brook JS. Pathways to smoking cessation among African American and Puerto Rican young adults. Am J Public Health 2007;97:1444–1448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brook JS, Morojele NK, Brook DW, Rosen Z. Predictors of cigarette use among South African adolescents. Int J Behav Med 2005;12:207–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen P, Cohen J. Life Values and Adolescent Mental Health. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schaefer J, Graham J. Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychol Methods 2002;7:147–177 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2006. Volume I: Secondary School Students. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2007. NIH publication 07-6205 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schaefer E. Children's reports of parental behavior: an inventory. Child Dev 1965;36:413–424 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist 90-R (HSCL): a self-report symptom inventory. Behav Sci 1974;19:1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pearlin LI, Menaghan EG, Lieberman MA, Mullan JT. The stress process. J Health Soc Behav 1981;22:337–356 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Satorra A, Bentler PM. Scaling corrections for chi-square statistics in covariance structure analysis. In: Proceedings of the Business and Economic Sections. Alexandria, VA: American Statistical Association; 1988;308–313 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu L, Bentler PM, Kano Y. Can test statistics in covariance structure analysis be trusted? Psychol Bull 1992;112:351–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jöreskog KG, Sörbon D. LISREL 8: User's Reference Guide. Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International; 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelloway EK. Using LISREL for Structural Equation Modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brook JS, Balka EB, Fei K, Whiteman M. The effects of parental tobacco and marijuana use and personality attributes on child rearing in African-American and Puerto Rican young adults. J Child Fam Stud 2006;15:153–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burrows GD. It is now the time to further help the professionals and the public understand the nature, role and implications of stress for ill-health [editorial]. Stress Health 2006;22:139–141 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Preacher KJ, MacCallum RC, Atkinson C, Malarkey WB, Glaser R. Chronic stress and age-related increases in the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003;100:9090–9095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tian J, Wang X. An epidemiological survey of job stress and health in four occupational populations in Fuzhou city of China. Stress Health 2005;21:107–112 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weekes NY, MacLean J, Berger DE. Sex, stress, and health: does stress predict health symptoms differently in the two sexes? Stress Health 2005;21:147–156 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sloboda Z, Bukowski WJ. Handbook of Drug Abuse Prevention: Theory, Science, and Practice. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2003 [Google Scholar]