Recent reports indicate that close to half of adults aged 50 years and older in the United States have now been screened for colorectal cancer. This rate of screening is usually described as disappointing, and compares unfavorably to the higher rates obtained for other screening tests, such as mammography and Papanicolaou tests,1 with the implication that this state of affairs reflects a failure of the medical and public health systems. After all, only half of all eligible patients are getting a potentially life-saving screening test. Perhaps we are on the wrong track and we need to undertake major reforms in our approach, given the current woefully inadequate screening rates.

We prefer a second approach and attitude, which is a good deal more optimistic: a full 50% of eligible adults are being screened! This is extraordinary, given the fact that those undergoing screening are asymptomatic, and that the screening process, especially for colonoscopy, is fraught with potential obstacles: patients must agree in principle to an invasive examination, take and tolerate a disagreeable oral bowel preparation, miss a day of work for the examination, and, as sedation is used, have a chaperone assist in transportation home. The idea of screening colonoscopy was first introduced only 20 years ago2 and became a practical option for many eligible patients only in 2001, when the Centers for Medicare Services (and subsequently the majority of private insurance companies) began reimbursement for colonoscopy for average-risk patients. In contrast, Papanicolaou tests have been in use since the late 1940s and mammography has been a recommended screening test for at least 30 years; thus, to already be approaching the 50% range in acceptance is indeed a milestone worthy of remark.

The public health dividends of this increase in colorectal cancer screening are only beginning to materialize. There has been a consistent decline in colorectal cancer–related death rates for the past 30 years, likely owing to the onset and progressive use of screening modalities that started with digital rectal examinations and fecal occult blood testing, and, in recent years, colonoscopy.3 Still more hopeful is the concomitant decline in colorectal cancer incidence rates during these years, which can be understood as a consequence of the removal of precancerous adenomatous polyps during colonoscopy.

In this phenomenon, which was demonstrated in a landmark randomized clinical trial that evaluated fecal occult blood testing,4 lies the true power of colorectal cancer screening. Unlike mammography, which primarily detects cancer at an early and more remediable stage, colonoscopy, by virtue of polypectomy, will result in a lower incidence of colorectal cancer in our population. Given the decade-long progression from normal colonic mucosa to adenomatous polyp to carcinoma, we have reason to suspect that the recent decline in colorectal cancer incidence is just the tip of the iceberg, and that, in the decades to come, we will observe a more dramatic decline in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality among the “mere” 50% of the population that has undergone screening thus far. This represents enormous progress for a disease that remains the second leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States. Yet imagine the additional benefits our society would reap if we could extend colorectal cancer screening to the remaining 50% of the eligible population that has not yet been screened.

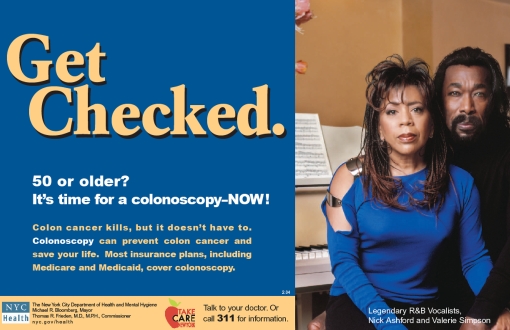

A public service announcement from the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene recommends colonoscopy as the preferred colorectal screening option. Courtesy of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

How do we reach this as-yet-unscreened group? One strategy is to increase the number of screening options in the hopes that, faced with more choices, patients will find a screening modality that they find agreeable. This is encapsulated in the maxim that “the best screening modality is the one that gets done.”

Indeed, our armamentarium continues to expand; the 2008 colorectal cancer screening guidelines published jointly by the American Cancer Society, the US Multisociety Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American Society of Radiology5 include three new tests deemed as acceptable screening options: stool DNA testing, fecal immunochemical testing, and computed tomography colonography. These three choices join the four previously recommended modalities (colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, double contrast barium enema, and guaiac-based fecal occult blood testing), yielding a total of seven choices for the patient and physician to consider. Perhaps future iterations of these guidelines will introduce further stratification of patients now considered at average risk for colorectal neoplasia, taking into consideration our emerging understanding of racial differences in adenoma rates.6

But this smorgasbord of screening choices may be prohibitively complex because deciding among them can be time consuming for the patient and physician. A patient who is informed of his or her cancer risk will more likely undergo a screening test.7 However, having more options is not necessarily a good thing. To make an informed choice among these tests, the patient must understand how each test is performed, appreciate the limitations of each examination, and, for any choice that is not colonoscopy, be willing to undergo a full colonoscopy if the initial examination yields a positive result. We suspect that the increasing quantity of colorectal cancer screening choices will offer diminishing marginal returns, as the potential benefit of each additional test is diluted by the increased complexity of the decision-making process.

In contrast to previous versions of these guidelines, which did not argue in favor of or against a particular screening choice, the present guidelines now denote a strong preference for tests that detect adenomatous polyps as well as cancer (colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, double contrast barium enema, and computed tomography colonography) over the stool tests for DNA or blood that primarily detect cancer. In reality, however, fecal occult blood testing is the only screening method that has been proven in randomized controlled trials to reduce the incidence and mortality caused by colorectal cancer.4,8 It is effective because it causes a subset of the population to undergo colonoscopy, regardless of the cause of the positive stool test. In this sense, therefore, fecal occult blood testing, like the other screening modalities, does lead to the detection of both adenomatous polyps and cancer, by virtue of the colonoscopy that follows a positive result. Thus, it also leads to a reduction in both incidence of and mortality from colorectal cancer.

Instead of presenting a palette of acceptable tests, we should simplify the choice facing the eligible screening candidate and his or her physician by offering a clear hierarchy of screening options, with colonoscopy at the top. This approach was adopted by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (see image). Since 2003, this health department has implemented an array of programs designed to increase awareness of and access to colonoscopy, which has resulted in an increase in colonoscopy rates from 40% of the eligible population in 2003 to greater than 60% in 2007.9 Especially encouraging are the data for African Americans, a group whose mortality rate from colon cancer remains higher than that of the general population, and whose access to preventive services has lagged behind that of Whites; colonoscopy rates among African Americans in New York City rose from 35% to 64% during this time period. Colonoscopy has now reached a “tipping point,” in that most eligible patients who have not yet been screened know one or more people who have had the procedure and, thus, are more likely to be agreeable to it. The Department of Health and Mental Hygiene's stated goal of an 80% colonoscopy rate for New Yorkers by 2011 is, thus, within reach.

Clearly, this remarkable public health achievement in New York City is not solely attributable to the city health department's simplified guidelines (available at http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/cancer/cancercolonscreen.shtml). A large investment of resources made it possible for the health department to target underserved populations, and a good deal of credit goes to its “patient navigators”—liaisons who encourage and assist patients who may otherwise not follow through with the multiple steps involved in undergoing colonoscopy. Implementation of the navigator program has resulted in high rates of colonoscopy completion and patient satisfaction.10 Regardless, the first step to take in reaching the as-yet unscreened is to strengthen our recommendations by simplifying them, identifying colonoscopy as the preferred screening test.

Acknowledgments

B. Lebwohl is supported by the National Cancer Institute (training grant T32-CA095929).

References

- 1.Shapiro JA, Seeff LC, Thompson TD, Nadel MR, Klabunde CN, Vernon SW. Colorectal cancer test use from the 2005 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2008;17:1623–1630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neugut AI, Forde KA. Screening colonoscopy: has the time come? Am J Gastroenterol 1988;83:295–297 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin 2008;58:71–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mandel JS, Church TR, Bond JH, et al. The effect of fecal occult-blood screening on the incidence of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2000;343:1603–1607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology 2008;134:1570–1595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lieberman DA, Holub JL, Moravec MD, Eisen GM, Peters D, Morris CD. Prevalence of colon polyps detected by colonoscopy screening in asymptomatic black and white patients. JAMA 2008;300:1417–1422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim SE, Perez-Stable EJ, Wong S, et al. Association between cancer risk perception and screening behavior among diverse women. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:728–734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hardcastle JD, Chamberlain JO, Robinson MH, et al. Randomised controlled trial of faecal-occult-blood screening for colorectal cancer. Lancet 1996;348:1472–1477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene An additional 350,000 New Yorkers have been screened for colon cancer since 2003 [press release]. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/pr2007/pr045-07.shtml. Accessed October 6, 2008

- 10.Chen LA, Santos S, Jandorf L, et al. A program to enhance completion of screening colonoscopy among urban minorities. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;6:443–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]