Abstract

High-throughput screening (HTS) has become an integral part of academic and industrial efforts aimed at developing new chemical probes and drugs. These screens typically generate several “hits”, or lead active compounds, that must be prioritized for follow-up medicinal chemistry studies. Among primary considerations for ranking lead compounds is selectivity for the intended target, especially among mechanistically related proteins. Here, we show how the chemical proteomic technology activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) can serve as a universal assay to rank HTS hits based on their selectivity across many members of an enzyme superfamily. As a case study, four metalloproteinase-13 (MMP13) inhibitors of similar potency originating from a publically supported HTS and reported in PubChem were tested by ABPP for selectivity against a panel of 27 diverse metalloproteases. The inhibitors could be readily separated into two groups: 1) those that were active against several metalloproteases, and 2) those that showed high selectivity for MMP13. The latter set of inhibitors was thereby designated as more suitable for future medicinal chemistry optimization. We anticipate that ABPP will find general utility as a platform to rank the selectivity of lead compounds emerging from HTS assays for a wide variety of enzymes.

1. Introduction

High-throughput screening (HTS) has emerged as a powerful means to discover chemical entities that perturb the function of proteins1,2. The “hits”, or lead compounds, that emerge from HTS efforts are typically subject to medicinal chemistry optimization to improve potency and selectivity, as well as suitable in vivo properties (stability, distribution, etc). These follow-up chemistry efforts require a significant investment of time and resources, and there is therefore much interest in developing methods to first rank HTS hits for desired properties. The HTS assay itself can be used to determine the relative potency of hits (e.g., IC50 values for inhibitors of an enzyme). However, these assays do not address the selectivity of lead compounds, which is a more challenging parameter to rapidly and systematically assess. Selectivity is particular important for proteins such as enzymes, which often belong to superfamilies that possess many members related by sequence and mechanism. Although preliminary estimates of selectivity can be generated by targeted counter-screening against nearest sequence-neighbor enzymes (assuming the availability of substrate assays), it is becoming increasingly clear that very distantly related members of enzyme classes can still share considerable overlap in their inhibitor sensitivity profiles3-6. Thus, the need for advanced methods to determine the class-wide selectivity of lead inhibitors is apparent.

An emerging platform to evaluate the selectivity of enzyme inhibitors is competitive activity-based protein profiling (ABPP)3-8. ABPP is a chemical proteomic method that uses active site-directed small-molecule probes to profile the functional state of enzymes directly in complex biological systems 9,10. In competitive ABPP, inhibitors are evaluated for their ability to compete with probes for binding to enzyme active sites, which results in a quantitative reduction in probe labeling intensity. Competitive ABPP offers several advantages over conventional inhibitor screening methods. First, enzymes can be tested in virtually any biological preparation, including as purified proteins or in crude cell/tissue proteomes3-8. Second, probe labeling serves as a uniform format for screening, thereby alleviating the need for individualized substrate assays and permitting the analysis of enzymes that lack known substrates11,12. Finally, because ABPP tests inhibitors against many enzymes in parallel, potency and selectivity factors can be simultaneously assigned to these compounds3-7,11,12.

To date, competitive ABPP has been applied to optimize the selectivity of inhibitors for well-studied enzymes3-7 as well as to discover inhibitors for uncharacterized enzymes11,12. In these cases, the inhibitors under examination originated from targeted medicinal chemistry efforts or modest-sized libraries of compounds. Here, we set out to test whether this method could be used to rank the selectivity of lead inhibitors emerging from publically supported HTS efforts. As a model study, we chose to analyze a set of lead compounds emerging from a screen for inhibitors of matrix metalloprotease 13 (MMP13). MMP13 is implicated in a number of diseases, including cancer, heart failure, and osteoarthritis13. While many MMP inhibitors have been developed, most have failed in clinical trials, likely due, at least in part, to a lack of selectivity among the more than 100+ metalloproteases (MPs) found in the human proteome14,15. The key role of MMP13 in disease, combined with the difficulty of developing selective inhibitors for the MMP family, designated this enzyme as an excellent candidate for tandem HTS-ABPP.

2. Results

2.1. Competitive ABPP for the quantitation of MMP13 inhibition

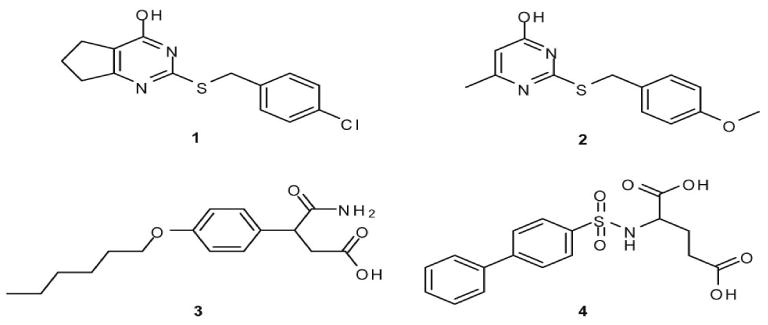

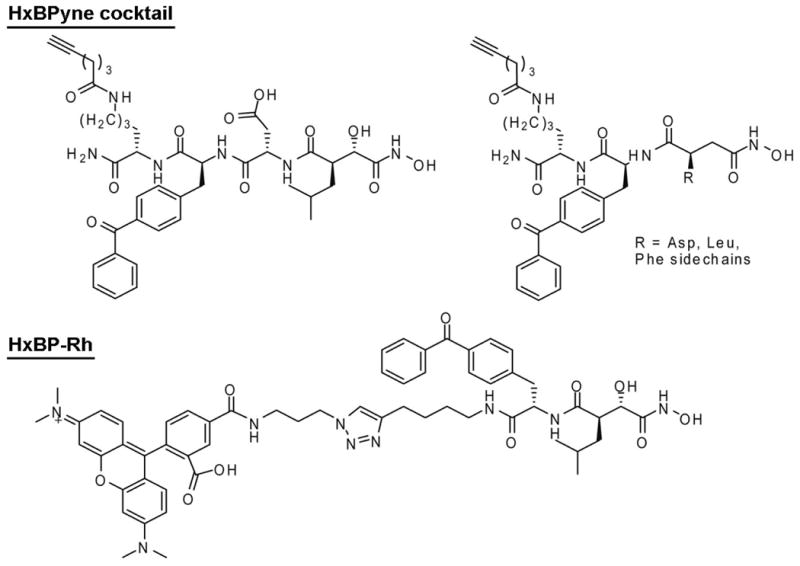

Approximately 60,000 compounds were previously assayed for MMP13 inhibition by the laboratory of Gregory Fields in collaboration with the Molecular Library Screening Center Network (MLSCN) at The Scripps Research Institute and the data deposited into PubChem [PubChem AID: 734 & 735; also see accompanying manuscript (ref. 16]). Four of the top hits (IC50 values 2-5 μM, compounds 1-4, Figure 1) were selected for competitive ABPP analysis. We first set out to determine IC50 values for blockade of MMP13 labeling by HxBPyne probes, a cocktail of previously reported ABPP probes that target a wide diversity of MPs17. HxBPyne probes contain: 1) a hydroxamic acid moiety that coordinates the zinc atom in MP active sites in a bidentate manner, 2) a diverse set of binding groups to bolster the affinity of probe-MP interactions, 3) a benzophenone to effect covalent labeling of MPs upon UV irradiation, and 4) an alkyne as a handle for subsequent click chemistry incorporation of a reporter tag18,19 (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Published PubChem structures of MMP13 inhibitors discovered by an HTS performed the Molecular Library Screening Center Network (MLSCN) at The Scripps Research Institute

Figure 2.

Structures of the MP-directed ABPP probes used in this study.

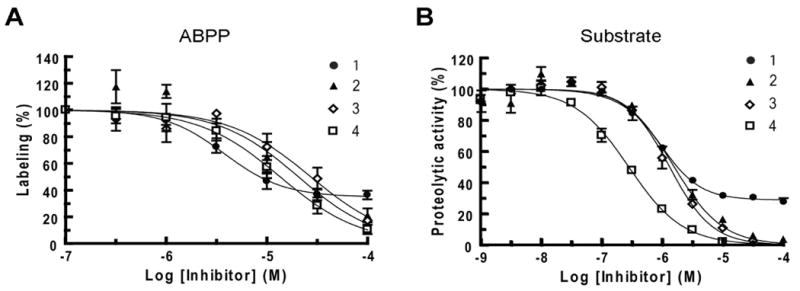

MMP13 was pre-treated with a range of concentrations of 1-4 (0.1-100 μM, 15 min), and then incubated with HxBPyne probes (100 nM total concentration) under UV light conditions for 1 h. The samples were then treated with a rhodamine-azide reporter tag under click chemistry conditions, separated by SDS-PAGE, and quantified by in-gel fluorescence scanning. Inhibitors 1-4 were found to block probe labeling of MMP13 with IC50 values ranging from 3.8-27 μM (Table 1 and Figure 3A). These values were slightly higher than those observed in substrate assays (0.28-1.6 μM, Table 1), a result that can be rationalized by the higher relative binding affinity displayed by MMP13 for HxBPyne probes compared to fluorescent substrates (see Discussion).

Table 1.

Inhibition of MMP13 by compounds 1-4.

| Inhibitor | IC50 (μM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| PubChema | ABPPb | Substrate Assayb | |

| 1 | 3.36 | 3.8 (2.8-5.2)c | 0.92 (0.72 – 1.2)c |

| 2 | 4.32 | 20 (13-33) | 1.6 (1.2 – 2.0) |

| 3 | 4.82 | 27 (19-40) | 1.3 (1.2 – 1.5) |

| 4 | 2.08 | 13 (10-18) | 0.28 (0.25 – 0.32) |

Results reported in PubChem database.

Data represent the averages with 95% confidence intervals shown in parentheses of three independent experiments.

Inhibitor 1 shows partial inhibition (maximal inhibition ∼70%).

Figure 3.

Inhibition of MMP13 by compounds 1-4 as measured by competitive ABPP (a) and substrate (b) assays.

A more detailed analysis of the inhibition curves revealed that, while compounds 2-4 produced an essentially complete blockade of probe labeling at the highest concentrations tested, the inhibition of MMP13 by compound 1 peaked at ∼70% (Figure 3A). A similar finding was observed using substrate assays (Figure 3B), indicating that 1 may inhibit MMP13 by a distinct mechanism from compounds 2-4. Consistent with this premise, the Fields group found that compound 1 (designated compound Q in their accompanying manuscript16) was the only inhibitor that proved more effective against MMP13 triple-helical peptidase activity compared with MMP13 single-stranded peptidase activity16, possibly indicating an interaction with an exosite involved in MMP13 collagen-binding.

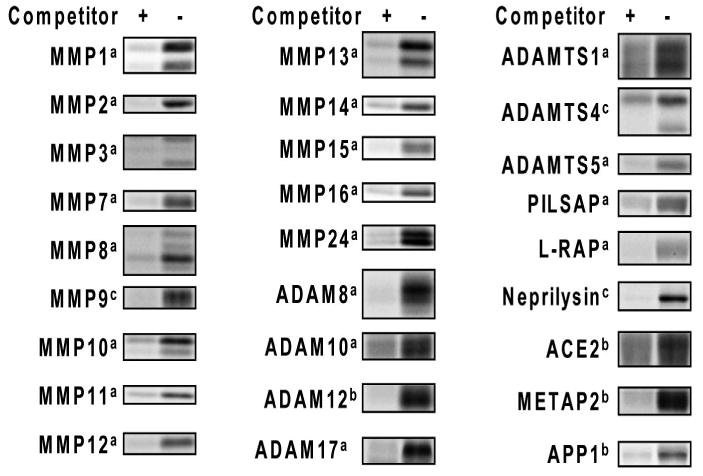

2.2 Optimization of competitive ABPP for a large panel of MPs

Having confirmed that the inhibitory activity of 1-4 for MMP13 can be measured by competitive ABPP, we next prepared a panel of diverse MPs for selectivity analysis. Thirty-one commercially available human recombinant metalloproteases were selected, including 15 MMPs, 8 ADAM (a disintegrin and metalloprotease) and ADAMTSs (ADAMs with thrombospondin motifs), and 8 more distantly related MPs [puromycin-insensitive leucyl-specific aminopeptidase (PILSAP), leukocyte-derived arginine aminopeptidase (L-RAP), neprilysin, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), methionyl aminopeptidase 2 (METAP2), aminopeptidase P1 (APP1), aminopeptidase A (APA), and aminopeptidase P2 (APP2)]. Twenty of the MPs showed clear evidence of active site labeling under a single set of conditions (0.5 μM MP, 0.5 μM HxBPyne probes in PBS, 30 min preincubation time; reactions performed in a background proteome of 1 mg/mL mouse liver cytosol to minimize MP self-cleavage). Active site labeling was confirmed by blockade of fluorescent signals with excess “non-clickable” probe (5 μM HxBPane probes17) (Figure 4 and Supplementary Figure 1). Four additional MPs showed active site labeling with higher concentrations of enzyme and probe (1.6 and 20 μM, respectively). Three enzymes (ADAMTS4, MMP9, and neprilysin) showed poor labeling with HxBPyne, but could be labeled by a related MP probe, HxBP-Rh5 (Figure 2). The four remaining enzymes (APA, MMP17, ADAM9, and APP2) were not efficiently labeled under any of the attempted conditions and were therefore excluded from competitive ABPP analysis. In summary, we determined that 27 distinct MPs could be profiled by competitive ABPP using three general sets of reaction conditions.

Figure 4.

Labeling of human recombinant MPs with ABPP probes. Conditions employed were: a 0.5 μM MP, 0.5 μM HxBPyne, competitor: 5 μM HxBPane; b 1.6 μM MP, 20 μM HxBPyne, competitor: 200 μM HxBPane; c 0.5 μM MP, 0.5 μM HxBP-Rh, competitor: 200 μM HxBP-alkyne.

2.3. Selectivity profiles of MMP13 inhibitors

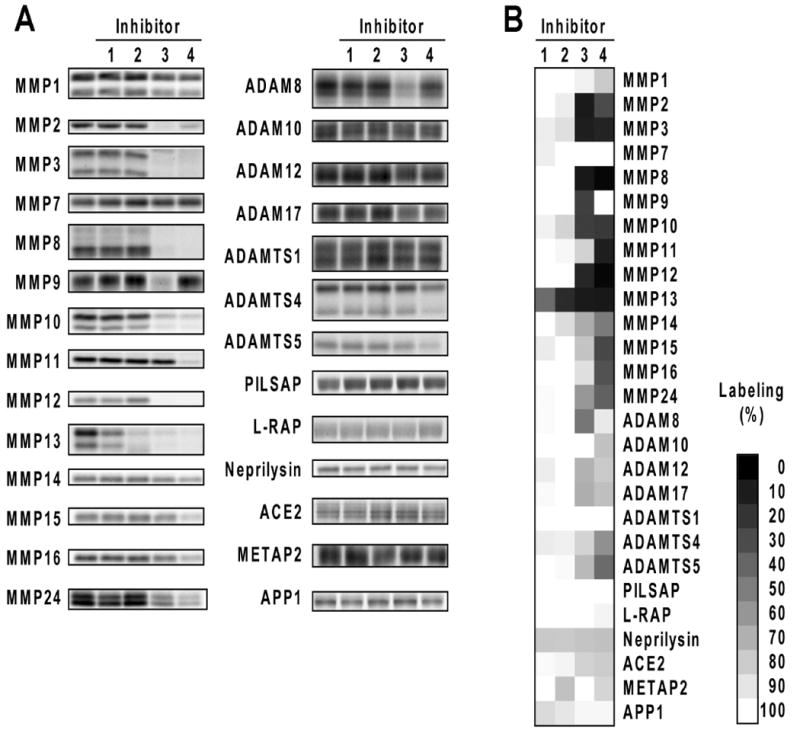

To evaluate the selectivity of 1-4 against the MP panel, these inhibitors were assayed by competitive ABPP at 200 μM, a concentration that was ∼10-fold higher than the IC50 values observed for MMP13 inhibition. The inhibitors showed markedly distinct activities against the MP panel. Inhibitors 3 and 4 targeted a large number of MPs. Both compounds inhibited MMPs 2, 3, 8, 10, and 12, whereas 3 also blocked probe labeling of MMP9 and ADAM8 and 4 inhibited MMPs 11, 14, 15, 16, 24, and ADAMTS5 (Figure 5 and Supplementary Figure 2). In contrast, the pyrimidine-based inhibitors 1 and 2 displayed remarkable selectivity for MMP13 and did not compete for probe labeling with any of the additional MP targets.

Figure 5.

Selectivity of MMP13 inhibitors against a panel of MPs evaluated by competitive ABPP. (a) Representative gel data. (b) Array format data representing the average of two to three independent experiments.

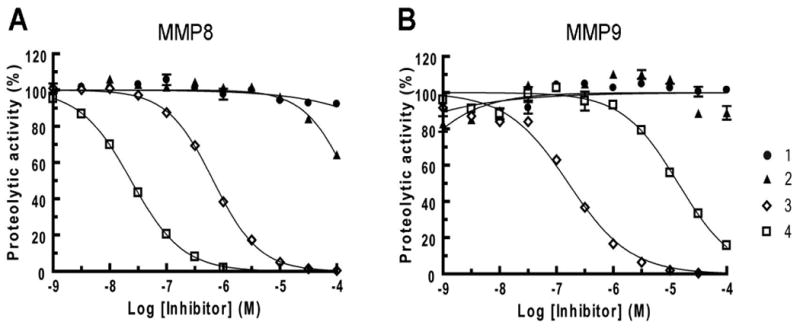

To confirm that the inhibitory profiles determined by competitive ABPP were consistent with those determined by conventional assays, we selected two “off-target” enzymes (MMP 8 and 9) with disparate profiles and characterized their sensitivity to 1-4 using a quenched fluorogenic peptide substrate assay (Figure 5 and Table 2). Consistent with the competitive ABPP data, MMP8 was inhibited by 3 and 4, while MMP9 was blocked by 3, but only weakly affected by 4 (Figure 6 and Table 2). Compounds 1 and 2 showed negligible activity against MMP8 and MMP9 at concentrations up to 100 μM (< 50% inhibition), which contrasted sharply with their low-μM IC50 values for MMP13. These data collectively designate 1 and 2 as highly selective inhibitors of MMP13 and attractive leads for further medicinal chemistry pursuits.

Table 2.

Inhibition of MMPs 8 and 9 by compounds 1-4 as measured by substrate assays.

| Inhibitor | IC50 (μM)a | |

|---|---|---|

| MMP8 | MMP9 | |

| 1 | >100 | >100 |

| 2 | >100 | >100 |

| 3 | 0.67 (0.63 – 0.70) | 0.16 (0.14 – 0.19) |

| 4 | 0.024 (0.023 – 0.025) | 14 (11 – 17) |

Data represent the averages with 95% confidence intervals shown in parentheses of three independent experiments

Figure 6.

Inhibition of MMP8 (a) and MMP9 (b) by compounds 1-4 as measured by substrate assays.

3. Discussion

High-throughput screening (HTS) provides a means to rapidly identify lead inhibitors of enzymes, but this method does not address the important issue of target selectivity. Traditionally, selectivity has been tested by counterscreening against a small panel of sequence-related enzymes using conventional substrate assays. However, this approach is inherently limited for multiple reasons. First, sequence relatedness is not necessarily a good predictor of active site homology. Indeed, many examples now exist of distantly related enzymes showing considerable overlap in their inhibitor sensitivity profiles3-6. Second, most enzyme superfamilies in the human proteome contain uncharacterized members for which substrate assays are not yet available. Even for relatively well-studied enzymes, convenient substrate assays are often lacking. In the case of the MPs examined herein, multiple enzymes (e.g., MMP11, ADAM12, ADAMTS1, ADAMTS4, and ADAMTS5), are typically assayed using macromolecular substrates, which must be run out on SDS-PAGE gels, Coomassie stained or western blotted, and quantitated by chemiluminescence20-22. We also found that screening the remainder of our MP panel required at least 8 different fluorogenic peptide substrates. Thus, to survey the total number of enzymes evaluated in this study by conventional methods would have required more than 10 distinct assay formats.

Due to the limitations imposed by conventional substrate assays, competitive ABPP has emerged as a powerful strategy to profile the selectivity of inhibitors across many members of enzyme superfamilies. Here, we have shown that a diverse panel of MPs can be analyzed by competitive ABPP. Only three conditions were required to obtain inhibition profiles for a panel of 27 enzymes spanning 6 subfamilies (M1, M2, M10, M12, M13, and M24) of MPs. We assayed this MP panel against four compounds (1-4) identified as inhibitors of MMP13 in a recent MLSCN-supported HTS. Competitive ABPP neatly segregated the tested compounds into two groups. The pyrimidine scaffold compounds 1 and 2 were highly selective for MMP13. On the other hand, compounds 3 and 4 showed broad activity against several MPs in the ABPP assays, an observation that was confirmed via substrate assays (Figure 6). These data match quite well those generated by the Fields group, who has analyzed lead MMP13 inhibitors against a panel of MMPs using substrate-based assays16. We speculate that the promiscuity of compounds 3 and 4 may be due to their shared carboxylic acid moiety, which is a potential site for coordination to the conserved zinc atom in MP active sites23. It is also notable that the off-target hits observed for 3 and 4 were not restricted to MMPs, but also included enzymes that display little or no sequence homology to MMP13 (e.g., ADAMTSs). In contrast, the remarkable selectivity displayed by 1 and 2 designates these agents as attractive leads for future medicinal chemistry pursuits aimed at developing pharmacologically useful MMP13 inhibitors. It is particularly noteworthy that competitive ABPP further designated compound 1 as an unusual inhibitor due to its inability at high concentrations to completely block probe labeling. This inhibitor was also found by the Fields group to display the atypical feature of being more effective against MMP13 triple-helical peptidase activity compared with MMP13 single-stranded peptidase activity, suggesting that it may bind to an MMP13 exosite16. These data thus underscore the versatility of competitive ABPP as a secondary screening assay to discern not only the selectivity of lead compounds, but also to gain insights into their mechanism of action.

While we have demonstrated the utility of competitive ABPP for assessing MP inhibitor selectivity, this approach is not limited to the MP enzyme class. ABPP probes have been developed for a diverse range of enzyme families10, and several of these probes have been used in a competitive fashion to identify enzyme inhibitors3-8,11,12. One important point to consider in using competitive ABPP to assess inhibitor selectivity is that the IC50 values generated with this approach may differ from true binding constants, especially in cases where the probe displays high binding affinity for enzyme targets. This issue is most relevant for photoreactive ABPP probes, such as the MP-directed probes described herein, which often must be included at concentrations at or above their binding affinity to achieve efficient levels of UV light-induced labeling of enzyme targets. Thus, the IC50 values for MMP13 inhibitors (3.8 – 27 μM) measured by competitive ABPP were ∼10-15-fold higher than those calculated from substrate assays (0.28 – 1.6 μM), a shift that could mostly be accounted for by the concentration of the HxBPyne probe cocktail used in the assays (100 nM), which was 5-fold higher than the IC50 value of the probes for MMP13 inhibition (20 nM) (in contrast, substrate assays were conducted with substrate concentrations ∼ equal to Km). These issues are less of a concern for electrophilic ABPP probes, such as the fluorophosphonates and acyl-phosphates, which label hydrolases24,25 and kinases26, respectively, as such “reactivity-driven” probes are typically used at concentrations far below their binding affinity for enzyme targets. Regardless, the shifts in IC50 values that may be observed in competitive ABPP assays can be readily accounted for, as described above for MMP13, and, therefore, do not hinder the utility of this method for evaluating inhibitor selectivity across enzyme superfamilies.

There are some limitations to the ABPP approach described herein that should be mentioned. First, only commercially available MPs were screened in the current study. Purified enzymes, rather than cell lysates were chosen because cells contain many inhibitors that regulate the activity of endogenous MPs. However, ABPP has been successfully performed in native proteomes for several MPs5,17, as well as many other enzyme classes10. Projecting forward, it would be of great value to assemble a set of proteomes that collectively contain the majority of mammalian MPs in active form. One way to do this would be to screen numerous tissue proteomes to identify sources that display complementary endogenous MP activity profiles. An alternate strategy would be to establish cell lines that doverexpress individual recombinant MPs and apply ABPP to the lysates of these cells. Recent success in profiling a large fraction of the serine hydrolase superfamily as recombinant proteins in transfected cellular proteomes supports the general viability of this approach27.

Our competitive ABPP analysis was also restricted to enzymes from the same mechanistic class as MMP13. It is formally possible that the identified inhibitors could target non-MPs. To address this concern, probes for additional classes of enzymes could be incorporated into competitive ABPP screens. For example, ABPP probes have been developed for histone deacetylases, another zinc-dependent metalloenzyme family28, as well as all major classes of proteases10.

4. Conclusion

This study showcases the utility of competitive ABPP to prioritize lead inhibitors of MMP13 based on selectivity across a large panel of MPs. While the MMP13 inhibitors analyzed herein originated from high throughput screening, competitive ABPP should be applicable to a wide range of medicinal chemistry efforts. Furthermore, considering that ABPP probes are now available for numerous enzyme classes, we anticipate that the methods described herein will emerge as a preferred strategy to accelerate the conversion of HTS hits into selective chemical probes for biological investigations.

5. Experimental

5.1. Chemicals

Compounds 1 (PubChem SID, 4257091) and 2 (PubChem SID, 7974872) were purchased from ChemBridge Corporation (San Diego, CA). Compounds 3 (PubChem SID, 849365) and 4 (PubChem SID, 842343) were purchased from Asinex (Winston-Salem, NC). Tris(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine (TCEP) was purchased from Fluka (St. Louis, MO). The click-chemistry ligand, tris[(1-benzyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)methyl]amine, was purchased from Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The syntheses of rhodamine-azide19, HxBP-Rh5, and HxBP-alkyne5 were previously reported. The optimized HxBPyne probe and HxBPane competitor cocktails (consisting of four individual probes: AspR1, AspR2, LeuR2, PheR2) were previously described17.

5.2. Enzymes and substrates

Human recombinant MMP1, MMP3, MMP8, MMP10, MMP11, MMP12, MMP13, ADAM12, ACE2, and fluorescence-quenched peptide substrate Mca-Pro-Leu-Gly-Leu-Dpa-Ala-Arg-NH2 were purchased from Biomol International LP (Plymouth Meeting, PA). Human recombinant MMP2, MMP7, MMP9, MMP14, MMP15, MMP16, MMP17, MMP24, ADAM17, and ADAMTS4 were purchased from EMD Biosciences (San Diego, CA). Human recombinant ADAM8, ADAM9, ADAM10, ADAMTS1, ADAMTS5, PILSAP, L-RAP, neprilysin, METAP2, APA, APP1, and APP2 were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). ADAM8 was activated by incubating the enzyme at 37 °C for 5 to 7 days (per manufacturer's protocol) all other enzymes were used as received.

5.3. Competitive ABPP with HxBPyne probes

Two sets of conditions were employed for competitive ABPP experiments with HxBPyne probes. For MMP1, MMP2, MMP3, MMP7, MMP8, MMP10, MMP11, MMP12, MMP13, MMP14, MMP15, MMP16, MMP24, ADAM8, ADAM10, ADAM17, ADAMTS1, ADAMTS5, PILSAP, and L-RAP, the enzyme was diluted to a final concentration of 0.5 μM in a background proteome of mouse liver soluble proteome (1 mg protein/mL in PBS). HxBPyne probe cocktail was added to the sample (final total probe concentration: 0.5 μM) in the presence of 5 μM HxBPane competitor, 200 μM inhibitor 1-4, or DMSO alone. For ADAM12, ACE2, METAP2, and APP1, the metalloprotease was diluted to a final concentration of 1.6 μM in PBS. The mouse liver proteome was omitted from these samples because the MPs co-migrated with endogenous mouse liver protein bands on SDS-PAGE gels. The HxBPyne probe cocktail was added to the sample (final concentration: 20 μM) in the presence of 200 μM HxBPane competitor, 200 μM inhibitor, or DMSO alone. The samples were arrayed in a 96-well plate, preincubated on ice for 30 min, and irradiated on ice at 365 nm for 1 h using a Spectroline ENF 260C UV lamp. After UV crosslinking, rhodamine-azide (final concentration: 12.5 μM), TCEP (final concentration: 500 μM), and ligand (final concentration: 100 μM) were added. The samples were mixed and the azide-alkyne cycloaddition reaction initiated by the addition of Cu2SO4 (final concentration: 1 mM). The reactions were incubated at room temperature in the dark for 1 h, after which 2X SDS-PAGE loading buffer was added. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE on 10 or 14% gels, and visualized by in-gel fluorescence scanning using a Hitachi FMBio IIe flatbed scanner (MiraiBio, Alameda, CA). Labeled proteins were quantified by measuring the integrated band intensities (normalized for volume). Control samples (DMSO alone) were considered 100% activity and inhibitor-treated samples were expressed as a percentage of the remaining activity.

IC50 values for the inhibitors against MMP13 were determined using 0.1 μM probe, 0.93 μM enzyme, and 0.1 μM – 100 μM inhibitor concentration. The activity observed using 0.1 μM inhibitor was set as 100% activity. IC50 values were determined by fitting the data from replicate trials (n = 3) to a sigmoidal dose–response curve with variable slope using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). For inhibitor 1, for which partial inhibition was observed, the bottom of the curve was not constrained to zero and the EC50 value was reported.

5.4. Competitive ABPP with HxBP-Rh probe

MP enzymes were diluted to a final concentration of 0.5 μM in PBS (for ADAMTS4 and neprilysin) or in a background proteome of mouse liver soluble proteome (1 mg protein/ml in PBS) (for MMP9). HxBP-Rh probe was added to the sample (final concentration: 0.5 μM) in the presence of 200 μM HxBP-alkyne, 200 μM inhibitor, or DMSO alone. The samples were placed in the wells of a 96 well plate, preincubated on ice for 30 min, and irradiated for 1 h on ice at 365 nm using a Spectroline ENF 260C UV lamp. After UV crosslinking, the samples were deglycosylated with peptide N-glycosidase F (PNGaseF) (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) using previously described procedures25. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized using the methods described above.

5.5. Fluorogenic substrate assay

Fluorogenic substrate assays were performed in triplicate at room temperature in black 96-well plates. The enzyme (final concentration: 6 nM for MMP8, 2 nM for MMP9, 1.5 nM for MMP13) and inhibitor solutions were preincubated in assay buffer (50 mM HEPES buffer at pH 7.5 containing 10 mM CaCl2, 0.05% Brij-35) for 30 min. After the addition of the fluorescence-quenched peptide substrate Mca-Pro-Leu-Gly-Leu-Dpa-Ala-Arg-NH2 (final concentration 5 μM), the hydrolysis was monitored by following increase in fluorescence at 393 nm (λex = 328 nm) at 1 min time intervals for 10 min using a SpectraMax Gemini microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The initial rates of reaction were determined with a linear least-square method. IC50 values were determined by fitting data to a sigmoidal dose–response curve with variable slope using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). For inhibitor 1, for which partial inhibition was observed, the bottom of the curve was not constrained to zero and the EC50 value was reported.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Cravatt lab for their helpful discussions and suggestions and the uHTS group at Scripps Florida led by Peter Hodder for the primary screens. This work was supported by the American Cancer Society (PF-06-009-01-CDD, to C.M.S.), the National Institutes of Health (CA087660, CA118696, and MH074404), and the Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Ryuichiro Nakai, Department of Chemical Physiology, The Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology, 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, CA 92037, USA.

Cleo M. Salisbury, Department of Chemical Physiology, The Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology, 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, CA 92037, USA

Hugh Rosen, The Scripps Research Institute Molecular Screening Center, The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, CA 92037, USA.

Benjamin F. Cravatt, Department of Chemical Physiology, The Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology, 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, CA 92037, USA.

References and notes

- 1.Inglese J, Johnson RL, Simeonov A, Xia M, Zheng W, Austin CP, Auld DS. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:466. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jo E, Sanna MG, Gonzalez-Cabrera PJ, Thangadad S, Tigyi G, Osborne DA, Hla T, Parrill AL, Rosen H. Chem Biol. 2005;12:703. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leung D, Hardouin C, Boger DL, Cravatt BF. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:687. doi: 10.1038/nbt826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lichtman AH, Leung D, Shelton CC, Saghatelian A, Hardouin C, Boger DL, Cravatt BF. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;311:441. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.069401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saghatelian A, Jessani N, Joseph A, Humphrey M, Cravatt BF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402784101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenbaum DC, Arnold WD, Lu F, Hayrapetian L, Baruch A, Krumrine J, Toba S, Chehade K, Bromme D, Kuntz ID, Bogyo M. Chem Biol. 2002;9:1085. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00238-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenbaum D, Baruch A, Hayrapetian L, Darula Z, Burlingame A, Medzihradszky KF, Bogyo M. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1:60. doi: 10.1074/mcp.t100003-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knuckley B, Luo Y, Thompson PR. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.10.021. epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Speers AE, Cravatt BF. Chembiochem. 2004;5:41. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans MJ, Cravatt BF. Chem Rev. 2006;106:3279. doi: 10.1021/cr050288g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiang KP, Niessen S, Saghatelian A, Cravatt BF. Chem Biol. 2006;13:1041. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li W, Blankman JL, Cravatt BF. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:9594. doi: 10.1021/ja073650c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leeman MF, Curran S, Murray GI. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;37:149. doi: 10.1080/10409230290771483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coussens LM, Fingleton B, Matrisian LM. Science. 2002;295:2387. doi: 10.1126/science.1067100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Overall CM, Kleifeld O. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:941. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lauer-Fields JL, Minond D, Chase PS, Baillargeon PE, Hodder P, Fields GB. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.03.004. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sieber SA, Niessen S, Hoover HS, Cravatt BF. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:274. doi: 10.1038/nchembio781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Speers AE, Adam GC, Cravatt BF. J Amer Chem Soc. 2003;125:4686. doi: 10.1021/ja034490h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Speers AE, Cravatt BF. Chem Biol. 2004;11:535. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao G, Westling J, Thompson VP, Howell TD, Gottschall PE, Sandy JD. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:11034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107443200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi Z, Xu W, Loechel F, Wewer UM, Murphy LJ. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:18574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002172200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pan W, Arnone M, Kendall M, Grafstrom RH, Seitz SP, Wasserman ZR, Albright CF. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304436200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cross JB, Duca JS, Kaminski JJ, Madison VS. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:11004. doi: 10.1021/ja0201810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Y, Patricelli MP, Cravatt BF. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jessani N, Liu Y, Humphrey M, Cravatt BF. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:10335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162187599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patricelli MP, Szardenings AK, Liyanage M, Nomanbhoy TK, Wu M, Weissig H, Aban A, Chun D, Tanner S, Kozarich JW. Biochemistry. 2007;46:350. doi: 10.1021/bi062142x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blankman JL, Simon GS, Cravatt BF. Chem Biol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.11.006. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salisbury CM, Cravatt BF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608659104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]