Abstract

Extinction of fear requires learning that anticipated aversive events no longer occur. Animal models reveal that sustained phosphorylation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (Erk) in hippocampal CA1 neurons plays an important role in this process. However, the key signals triggering and regulating the activity of Erk are not known. By varying the degree of expected and delivered aversive reinforcement, we demonstrate that Erk specifically responds to prediction errors of contextual aversive events. An increase of somatonuclear phospho-Erk (pErk) within principal CA1 neurons was observed only when the expectation of contextual foot shock was violated, but not when the context was consistently nonreinforced or reinforced by foot shock. The rate of error detection, Erk signaling, and fear extinction markedly depended on shock expectancy and the aversive valence of the context, as revealed by comparison of groups trained with single, continuous, or partial reinforcement. On the basis of these findings, the hippocampal Erk response to prediction errors of aversive outcome is proposed as a unique mechanism of fear extinction. Improving the detection and processing of these errors has the potential to attenuate fear responses in patients with anxiety disorders.

The hippocampus plays an important role in processing surprising events, such as new stimuli or known stimuli gaining new behavioral significance (Ploghaus et al. 2000; Lisman and Grace 2005). Accordingly, fear conditioning formed after delivery of unexpected reinforcement, and fear extinction occurring after omission of expected aversive reinforcement, depend on hippocampal activity (Knight et al. 2004; Lattal et al. 2006). Whereas fear conditioning is rapidly and robustly acquired after a single exposure to a novel context paired with foot shock, extinction typically requires multiple nonreinforced contextual exposures (Vianna et al. 2001; Fischer et al. 2004; Chen et al. 2005). These differences may be caused by several factors. First, extinction learning may depend on distinctive molecular mechanisms optimally requiring repeated stimulus presentations. Second, extinction could be slower because it involves new learning as well as retrieval (Ouyang and Thomas 2005), transient destabilization (Lee et al. 2008), and depotentiation (Kim et al. 2007) of the conditioning memory. Third, the expectancy of the aversive event acquired during conditioning needs to be modified for extinction to occur (Lovibond 2004). Fourth, if the aversive valence of the unconditioned stimulus (UCS) is transferred to the conditioned stimulus (CS) during conditioning, so that the CS not only serves as a predictor of UCS (expectancy learning) but also gains its aversive motivational properties (evaluative learning), extinction of fear may be markedly delayed (Baeyens et al. 1990; Vansteenwegen et al. 2006; Blechert et al. 2008). Despite the multitude of learning processes involved in conditioning and subsequent extinction of fear, the specific mechanisms by which each process individually contributes to fear regulation are not known.

At a molecular level, the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (Erk) has recently been identified as an important mediator of fear extinction (Szapiro et al. 2003; Chen et al. 2005; Tronson et al. 2008). Erk shows rapid and sustained phosphorylation shortly preceding and during fear extinction, which subsides after fear has stably extinguished (Fischer et al. 2007; Ryu et al. 2008). This activation pattern suggests that Erk is most likely triggered by some of the stimuli uniquely involved in extinction. Here, we show that prediction error of aversive events, but not memory retrieval, lack of reinforcement, or fear response, is the most likely signal activating Erk in hippocampal neurons. The shock expectancy and contextual aversive valence encoded during conditioning significantly accelerated and delayed, respectively, the rate of error detection, Erk signaling, and fear extinction.

Results

Aversive reinforcement or lack thereof does not trigger sustained nuclear Erk activation in hippocampal CA1 neurons

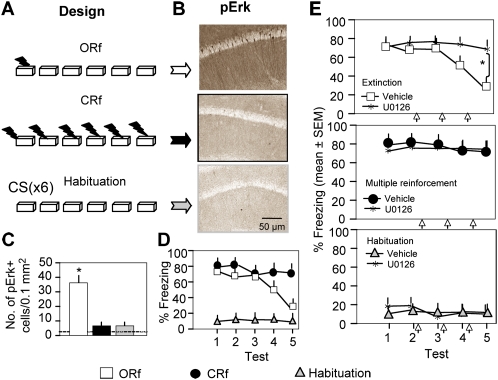

Retrieval of fear memory induced by context–shock reinforcement is manifested by freezing behavior. Retrieval of nonreinforced (context–no shock) presentations, on the other hand, is reflected by behavioral habituation of locomotor and exploratory activity (Leussis and Bolivar 2006). It is generally accepted that during extinction, retrieval of the conditioning (context–shock) memory is steadily replaced by retrieval of the extinction (context–no shock) memory, as revealed by corresponding changes of behavior (Bouton 2004). To determine whether nonreinforcement, aversive reinforcement, or memory retrieval contribute to the sustained nuclear increase of pErk, we employed three experimental groups (Fig. 1A). The extinction group consisted of mice exposed to one context–shock reinforcement (ORf) followed by nonreinforced contextual exposures for five consecutive days. The continuous reinforcement (CRf) group was exposed to context–shock trials once a day for six consecutive days, and the habituation group was exposed to six nonreinforced (context–no shock) exposures. The habituation group did not show freezing at any of the contextual exposures; however, the mean activity of this group significantly decreased between tests 1 and 6 (test 1: 12.2 ± 3 cm/sec; test 6: 3.8 ± 1.6 cm/sec; F (5,45) = 5.86, P < 0.01). 1 h after the last exposure, brains were collected for analyses of hippocampal pErk. The time point selected for the pErk analyses was based on prior time-course analyses (Fischer et al. 2007). Notably, increased pErk levels in the soma of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons were observed in the extinction (F (3,16) = 7.62, P < 0.01) but not in the CRf or habituation groups (Fig. 1B,C). Freezing behavior (Fig. 1D) was unlikely related to pErk levels, as revealed by an absence of the activated kinase in the hippocampi of mice displaying high (CRf group) or low (habituation group) freezing levels (F (8,120) = 6.12, P < 0.01). Because we determined the level of pErk at the time of maximal Erk phosphorylation after extinction, transient but behaviorally relevant activation of Erk might have been overlooked. We therefore performed additional pharmacological experiments with U0126, a blocker of the Erk upstream activator mitogen activated and extracellular signal regulated kinase (Mek). Intrahippocampal injection of U0126 immediately after every test completely abolished extinction (F (8,105) = 3.35, P < 0.01) without affecting freezing behavior in the reinforced group (F (8,105) = 0.41, P = 0.855) or habituation group (F (8,105) = 0.63, P = 0.792; Fig. 1E). These findings indicated that neither memory retrieval, which was expected to occur in all groups, nor consistently reinforced or nonreinforced context presentations contributed to pErk up-regulation in the hippocampus or the behavioral effects of Erk on extinction. Importantly, lack of reinforcement (CS–no UCS), as shown in the habituation group, was not a sufficient stimulus for Erk activation.

Figure 1.

Reinforcement or nonreinforcement does not activate Erk in CA1 hippocampal neurons. (A) Experimental design. Mice in the extinction group were exposed to a single context–shock pairing (ORf) followed by daily 3-min nonreinforced trials for five consecutive days. Mice of the continuous reinforcement (CRf) group were exposed once per day to context–shock pairings over six consecutive days. Mice of the habituation group were daily exposed to the context for 3 min without receiving shock. The number of mice per group was nine. One h after test 5, brains (n = 5/group selected randomly and an additional five brains of naive mice) were processed for pErk immunohistochemistry. (B) Strong pErk signals were observed within cells of the CA1 pyramidal layer during extinction, but such signals were lacking during CRf or habituation. (C) Quantification of pErk+ cells revealing significant up-regulation only in the extinction group. (*) P < 0.01 compared with reinforcement, habituation, and naive (dashed line). (D) Freezing behavior of different groups demonstrating reduction (extinction group), persistence (reinforcement group), or lack of fear (habituation group) as revealed by freezing behavior. (E) Effects of intrahippocampally injected U0126 fear extinction (top, extinction group), persistence of freezing (middle, reinforcement group), or habituation (bottom). Asterisk (*) indicates P < 0.01 compared with vehicle.

Context–no shock presentations trigger pErk only when shock is expected but not delivered

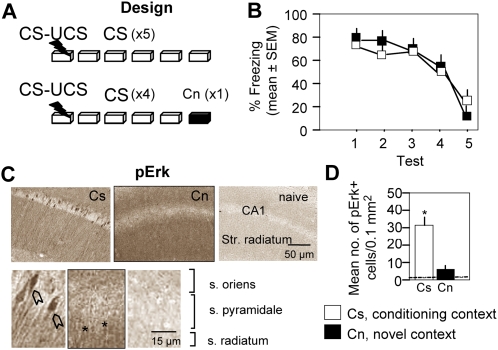

Unlike extinction, habituation does not involve any expectancy of foot shock based on prior conditioning. The pErk signals observed in the extinction group could thus be due to violation of shock expectations by lack of reinforcement, causing prediction error. To examine this possibility, we used two experimental groups differing in shock expectancy on the test preceding Erk analyses. Mice were trained by a single context–shock pairing and then exposed to daily extinction trials. On extinction test 5, half of the mice were re-exposed to the conditioning context and the other half were exposed to a new context (Fig. 2A). These groups shared the same history of conditioning, extinction, and fear (freezing behavior: Fig. 2B; F (4,80) = 1.103, P = 0.382). However, the extinction group still showed some fear-related behavior revealed by a low but detectable level of freezing (28%) and low locomotor activity (3.11 ± 0.43 cm/sec), whereas the group exposed to the novel context had no shock expectancy, as revealed by very low freezing (9%) and high locomotor activity (14 ± 1.12 cm/sec). 1 h after test 5, the mice were euthanized and their brains were examined for pErk immunoreactivity. Consistent with previous observations (Sananbenesi et al. 2003), pErk was strongly and diffusely up-regulated in apical dendrites, but not in the soma and nuclei of pyramidal cells, after exposure to a novel context (Fig. 2C). Sustained up-regulation of somatonuclear pErk was observed only after exposure to the conditioning/extinction but not conditioning/novel context (F (2,18) = 5.31, P < 0.01; Fig. 2D). These findings suggest that pErk specifically responded to a mismatch between expected and actual events. Thus, prediction error caused by lack of expected shock stands out as a key signal triggering pErk.

Figure 2.

Prediction error of aversive reinforcement triggers sustained activation and nuclear accumulation of pErk in CA1 hippocampal neurons. (A) Experimental design. After a single context–shock pairing, mice were exposed daily to the condtioning context (CS) for 3 min. On the last test, half of the mice were re-exposed to Cs whereas the other half were exposed to a novel context (Cn). One h later, brains of all mice were processed for immunohistochemical analyses. (B) Freezing behavior recorded during consecutive nonreinforced trials revealing fear extinction. On the last test (5), both groups exhibited low freezing in the respective contexts. The number of mice per group was eight. (C) Mice of the extinction group (CS) exhibited strong pErk immunoreactivity in cells of the pyramidal layer of the CA1 hippocampal subfield. On the other hand, mice with similar extinction history but exposed to a new context (Cn) where shock is not expected to occur showed low somatonuclear pErk. Note a diffuse up-regulation of pErk restricted to apical dendrites in response to Cn. (Open arrows) Cell bodies, (stars) apical dendrites. (D) Quantification of immunoreactive signals demonstrating significant group differences in pErk. (*) P < 0.01 compared with Cn and naive (n = 5, dashed line). Error bars indicate standard error of the mean (SEM).

Increasing shock expectancy accelerates extinction and Erk signaling

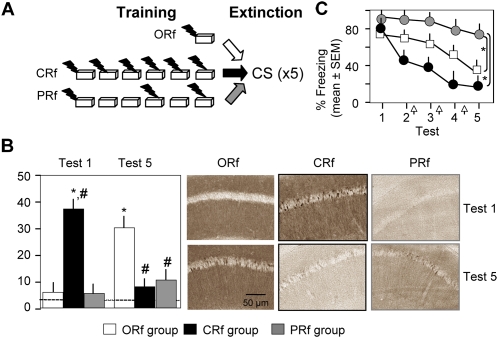

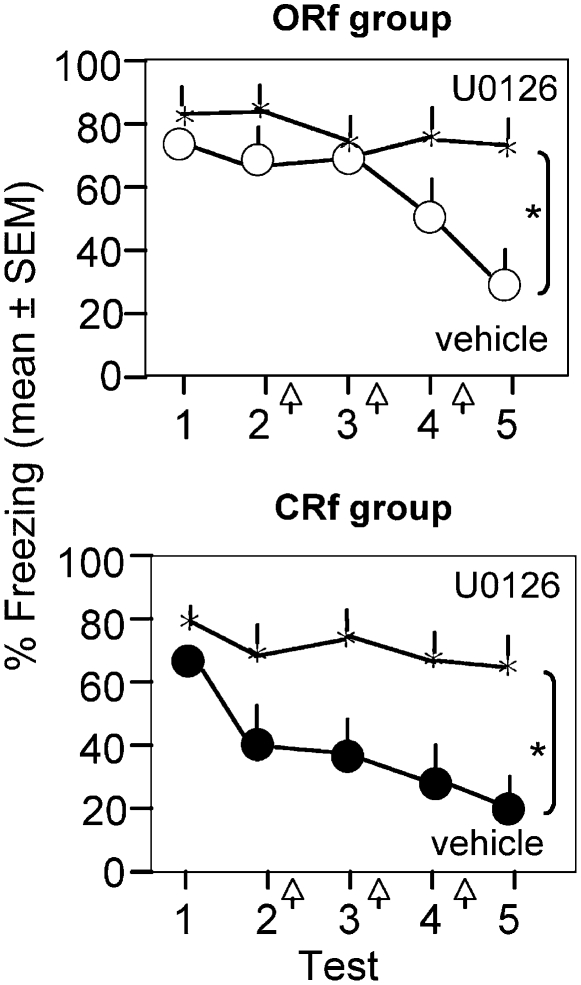

In order to further examine the role of prediction errors in Erk signaling, we next compared Erk activation and extinction in ORf, CRf, or partial reinforcement (PRf) groups of mice. The latter group was introduced to minimize the probability of forming accurate expectations of shock. Based on the results obtained above, it was predicted that the CRf group would have the highest shock expectancy and therefore generate stronger error signals along with accelerated Erk activation and extinction. The ORf group consisted of mice trained with a single context–shock pairing prior to five consecutive extinction trials; the CRf group consisted of mice trained with six context–shock pairings prior to five consecutive extinction trials; and the PRf group was presented with random shock reinforcement (Fig. 3A). In general, PRf and CRf paradigms can be matched either for CS or UCS exposures. Because Erk signaling did not depend on the number of UCS presentations (Fig. 1), we matched these groups for CS exposures that were either continuously (6/6, 100%) or partially (3/6, 50%) reinforced with shock. The CRf group showed a robust increase of pErk after only one extinction trial (F (4,16) = 9.78, P < 0.01), decaying after extinction persisted for five consecutive tests (Fig. 3B). Significant activation of pErk in the ORf group was observed after extinction test 5 (F (4,15) = 6.81, P < 0.01; Fig. 3B), as shown earlier. The PRf group, on the other hand, did not show a significant increase of Erk signaling after any of the investigated time points (F (4,15) = 0.73, P = 0.91 for test 1 and F (4,15) = 1.25, P = 0.62, when compared with the naive group [dashed line]). In line with these molecular data, fear extinction was most rapid in the CRf group, delayed in the ORf group, and impaired in the PRf group (Fig. 3C, top panel; F (8,203) = 15.207, P < 0.001). Based on pilot experiments showing that three shocks given as a continuous reinforcement (3/3) resulted in similar acquisition and extinction of fear as the ORf group (data not shown), the observed impairment of extinction in PRf mice was attributed to the inability to form accurate shock expectations. In order to determine whether extinction in both the ORf and CRf groups depended on Erk activity, we next studied the effects of an Erk inhibitor in either paradigm. Inhibition of the Erk upstream kinase Mek by intrahippocampal injection of the inhibitor U0126 completely abolished extinction in the ORf (F (8,105) = 3.22, P < 0.01; Fig. 4, upper panel) and CRf groups (F (8,105) = 4.26, P < 0.01; Fig. 4, bottom panel). Thus, extinction after both single and multiple reinforcement required Erk-dependent signaling; however, this mechanism was activated much faster in the CRf group. Notably, accelerated activation of Erk caused a rapid decline of fear, suggesting that molecular mechanisms of extinction learning can be as fast as mechanisms underlying fear conditioning if adequately triggered by strong error signals.

Figure 3.

Continuous reinforcement accelerates pErk up-regulation and extinction whereas partial reinforcement produces an opposite effect. (A) Experimental design. Mice were exposed to daily 3-min extinction trials for 5 d either after a single (ORf), continuous (CRf), or partial (PRf) reinforcement. Different mice assigned to these groups were employed to study the effect of reinforcement contingency on freezing behavior (n = 8/group) and Erk phosphorylation (n = 5/group and five naive mice, dashed line). (B) Neuronal pErk in the CA1 subfield of mice of the multiple reinforcement group significantly increased early during extinction (after test 1) and decreased by test 5. On the other hand, pErk up-regulation was delayed to test 5 in the ORf and impaired in the PRf group. Note strong pErk signals in apical dendrites of this group after test 1 but lack of pErk signals in the soma. (Right panel) Representative micrographs. (*) P < 0.01 compared with naive, (#) P < 0.01 compared with ORf. (C) Freezing behavior declined significantly faster during extinction of mice of the CRf when compared with the ORf and PRf groups.

Figure 4.

Extinction after single or multiple reinforcement is dependent on Mek/Erk signaling. (Upper panel) Extinction after single reinforcement is reversed by the Mek inhibitor U0126 (black stars) when compared with vehicle controls (white circles). (Lower panel) Extinction after multiple reinforcement is also fully abolished by U0126 (black stars) when compared with vehicle-injected controls (black circles). Asterisk (*) indicates P < 0.01 vs. vehicle.

Increasing shock expectancy decreases the aversive valence of the context

Given that prediction errors and learning rates should be the strongest at the time of maximal mismatch (extinction test 1), it remained unclear why both molecular and behavioral changes required several trials in the ORf group.

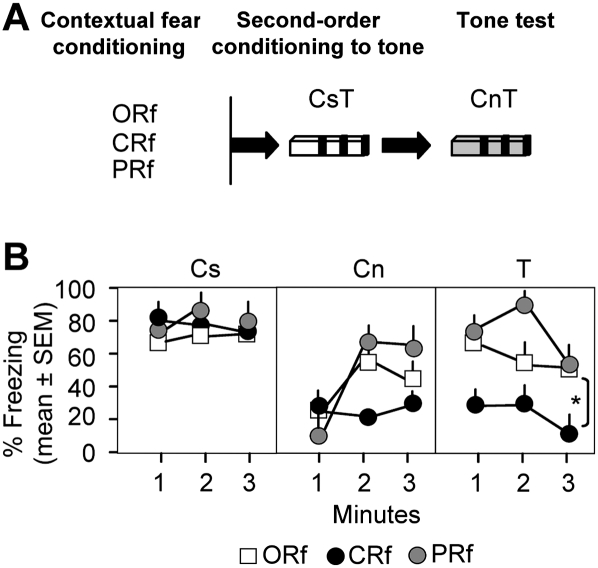

We therefore addressed the possibility that one-trial fear conditioning is not sufficient to induce the shock expectancy required for generation of error signals when shock is omitted. Alternatively, this paradigm may predominantly trigger evaluative learning known to be more resistant to extinction than expectancy learning. Because the intensity of fear generated by these types of learning is indistinguishable by somatic and behavioral measures, we addressed this question by employing second-order conditioning in the ORf, CRf, and PRf groups, using context as an aversive reinforcer and tone as a novel conditioned stimulus (Fig. 5A). This approach was based on the documented ability of aversive contexts to act as a second-order reinforcer in backward conditioning to discrete cues (Chang et al. 2004) and served to test the transfer of the shock valence to the context, a feature typical of evaluative learning. Contrary to the high freezing in the conditioning context (Fig. 5B, left panel), the second-order conditioning procedure (using pairing of the conditioning context and tone) did not induce freezing to a novel context (Fig. 5B, middle panel) prior to tone delivery (F (2,30) = 1.106, P = 0.72). However, the ORf and PRf groups showed significantly increased freezing to tone over the 3-min test period (F (2,30) = 20.609, P < 0.001), when compared with the CRf group (Fig. 5B, right panel). These results indicated that fear induced by one-trial conditioning or partial reinforcement was most likely based on the aversive valence of the context, whereas fear induced by multi-trial conditioning was probably founded on shock expectancy. High aversive valence of the context in combination with inadequate expectancy of shock occurrence could consequently trigger small prediction errors and retard or impair Erk signaling.

Figure 5.

Reinforcement affects the aversive contextual valence. (A) Experimental design. Mice of the different groups (n = 12–18/group) were exposed to the conditioning context and exposed to three 30-sec tones as described in Materials and Methods. Twenty-four hours later the mice were re-exposed to the tone (T) in a novel context (Cn). (B) Mice of all groups showed similar freezing levels to the conditioning context (left panel). Freezing to the novel context was low in all groups before tone presentation (1 min) but increased in the ORf and PRf groups thereafter (middle panel). Mice of the ORf and PRf groups acquired significantly more fear to the tone than mice of the CRf group (right panel). Asterisk (*) indicates P < 0.01 compared with CRf.

Discussion

By varying the degree of shock expectancy (DeVito and Fowler 1986) in novel or known aversive contexts, we demonstrated that prediction errors of aversive events resulted in sustained up-regulation of hippocampal pErk mediating extinction of contextual fear. Results from a number of experimental and control groups revealed that the activation and behavioral effects of Erk were unrelated to memory retrieval, aversive reinforcement, habituation, or freezing behavior. In line with these findings, human imaging data identify the hippocampus as one of the main brain areas responding to prediction errors caused by a mismatch between expected and delivered painful stimuli (Ploghaus et al. 2000). The mouse model employed here extends those observations by isolating a cellular and molecular mechanism causally linking the detection of prediction error to contextual fear extinction.

Impairment and enhancement of extinction that were observed in the PRf and CRf groups, respectively, when compared with the ORf group are consistent with partial reinforcement and overtraining extinction effects, two phenomena that have been explored extensively in experimental and theoretical work in psychology (Jenkins and Stanley Jr. 1950; McCain et al. 1962; Likely and Schnitzer 1968; Mackintosh 1974; Haselgrove et al. 2004). Although variable effects have been shown depending on the type of learning, reinforcer, and other parameters, the CRf and PRf effects appear consistent in tasks involving experimental contexts, as revealed by our data with fear conditioning and others' findings with conditioned emotional suppression (Wagner et al. 1967) and water maze learning (Prados et al. 2008). Accordingly, mice trained with multiple context–shock pairings showed robust and sustained pErk up-regulation and rapid Erk-dependent extinction when shock was subsequently omitted. These findings are in agreement with the principles of reinforcement learning (Rescorla and Wagner 1972; Pearce and Hall 1980; Dragoi 1997; Sutton and Barto 1998), positing that prediction errors and learning rates are maximal when the mismatch between expected and delivered reinforcement is the highest, which in our experiment would be the first nonreinforced trial.

One-trial conditioning, on the other hand, did not conform to these requirements, as revealed by a slower rate of fear extinction (Vianna et al. 2001; Chen et al. 2005; Fischer et al. 2007; Ryu et al. 2008) and delayed up-regulation of pErk. As aversive reinforcement was omitted during the first extinction trial of both ORf and CRf groups, these findings suggested that a single conditioning episode was not sufficient to produce high shock expectancy and prediction error despite inducing strong freezing behavior. The postponed increase of pErk and decrease of fear could thus be due to cumulative effects of several weaker prior errors, as has been reported in human studies (Wills et al. 2007), or, alternatively, to slower emergence of expectancy learning in this paradigm. Namely, similar to human aversive conditioning, freezing behavior in the absence of shock may be initially governed by evaluative learning (Hermans et al. 2002; Olatunji et al. 2007), with context serving as an aversive reinforcer until expectancy learning has been established. This latter possibility is supported by our data with second-order conditioning, showing high aversive valence of the context in the ORf and PRf groups that could delay the detection of prediction error, Erk activation, and fear extinction. Contrary to the contextual aversive valence, expectancy of shock (CRf group) was not sufficient to support one-trial second-order conditioning. Thus, second-order conditioning in our paradigm most likely involved an association between the tone and aversive motivational state triggered by the context (Ross 1986; Winterbauer and Balleine 2005).

Based on the somatonuclear up-regulation of pErk, it is likely that some of the downstream effects of Erk involve changes of gene expression in CA1 neurons and thereby initiate long-term neuronal changes underlying extinction. Given that Erk can bidirectionally modulate gene expression (Yamamoto et al. 2006), dendritic signaling (Wu et al. 2001), and synaptic plasticity (Thiels et al. 2002), identification of the specific molecular and genetic targets will help to better understand the molecular processes translating detection of prediction errors into long-term fear extinction.

At least two types of processes underlying long-lasting extinction learning have been proposed. One view posits a formation of new associations, either inhibitory CS–UCS or excitatory CS–noUCS associations (for review, see Myers and Davis 2002). The role of Erk in these processes is unlikely, however, because neither stimulus triggered pErk. Alternatively, hippocampal Erk mechanisms may be involved in modification of shock expectancy by providing input to the broader extinction circuitry. This view, based on the specific pErk responses to expectation violation, is consistent with the proposed hippocampal role in anticipatory behavior and predictive coding (Mehta 2001; Ploghaus et al. 2001). The demonstrated pErk responses to prediction error by principal CA1 neurons may thus represent a neuronal basis for modifying expectancy, opening the possibility to study in animal models a foremost process implicated in human fear extinction (Lovibond 2004).

These observations have several important implications. Multiple aversive reinforcements are thought to positively correlate with the strength and persistence of memories, thus rendering them resistant to extinction (Eisenberg et al. 2003). While this may be the case with partial reinforcement, our data show that continuous reinforcement potently facilitates extinction when expectations of aversive events are later violated. The behavioral and molecular analyses also reveal that extinction per se is not necessarily slower than conditioning. The underlying mechanisms, however, need to be adequately activated by error signals or, potentially, specific molecular and pharmacological approaches to mediate rapid and robust extinction learning. Failure to develop and modify the expectancy of aversive events via Erk-dependent mechanisms may contribute to impairments of fear extinction underlying human anxiety disorders.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Nine-week-old C57BL/6 male mice were obtained at 9 wk of age from Harlan. The mice were individually housed in a satellite facility adjacent to the behavioral equipment. The facility was provided with a separate ventilation system (15 air exchanges/hr), a 12/12 dark light cycle (7 am–7 pm), 40%–50% humidity, and 20°C ± 2°C temperature. All studies were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Northwestern University in compliance with National Institutes of Health standards. The number of mice per group was 8–15.

Surgery and cannulation

Double cannulae were placed into the dorsal hippocampus (vs. bregma: anteroposterior 1.5 mm, mediolateral 1 mm, dorsoventral 2 mm) as described earlier (Radulovic et al. 1999). The gauges of the guide and injection cannulae were 26 and 28, respectively. U0126 (1 μg/mouse) was delivered bilaterally (0.25 μL/side) over 30 sec immediately after the indicated tests. The cannula position was determined for each mouse at the end of experiments during histological examination of brain tissue, and only data obtained from mice with correctly inserted cannula were analyzed.

Fear conditioning and extinction

Contextual fear conditioning was performed with an automated system (TSE Inc.) and consisted of exposure to context (3 min) followed by a foot shock (2 sec, 0.7 mA, constant current) as described previously (Radulovic et al. 1999). The extinction trials were performed at 24-h intervals and consisted of nonreinforced 3-min exposures to the context (Fischer et al. 2004, 2007). Training consisted of one-trial fear conditioning (ORf group), continuous reinforcement (CRf group; one context-shock pairing/day for six consecutive days), or partial reinforcement (PRf group; 50% random reinforcement with foot shock). Habituation was performed by a 3-min daily exposure to the context for six consecutive days. Context-dependent freezing was measured every 10 sec over 3 min by two observers unaware of the experimental conditions and expressed as a percentage of the total number of observations. Second-order fear conditioning was induced by placing the mice in the conditioned context for 3 min while delivering a 30-sec tone (10 kHz, 75 dB SPL) after every minute (for a total of three). The tone-dependent memory test was performed by exposing the mice 24 h later to a novel context for 3 min while delivering a 30-sec tone after every minute. Freezing behavior to context 2 and tone was scored every 10 and 5 sec, respectively, and expressed as percentage of total number of observations.

Immunohistochemistry

Brains were collected 1 h after the indicated extinction tests. The selected time points were previously shown to give maximal pErk signals after extinction (Radulovic et al. 1998; Fischer et al. 2007). Mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of 240 mg/kg Avertin 1 h after the training, first, or fifth extinction tests as indicated and transcardially perfused with ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4, 150 mL/mouse). Brains were post-fixed for 48 h in the same fixative and then immersed for 24 h each in 10%, 20%, and 30% sucrose in phosphate buffer. After the tissue was frozen by liquid nitrogen, 50-μm-thick coronal sections were used for performing free-floating immunohistochemistry with primary antibodies to pErk (di-phospho Erk; Sigma, 1:16,000). Biotinylated secondary antibody and ABC peroxidase complex (Vector) were used for signal amplification and DAB (Sigma), FITC (fluorescein isothiocyanate), or rhodamine (TSA, NEN Life Sciences) as visualizing substrates. Control procedures involved immunostaining without primary or secondary antibodies and isotype controls.

Quantification of immunostaining signals was performed as described previously (Fischer et al. 2007). Digital images were captured with a cooled color CCD camera (RTKE Diagnostic Instruments) and SPOT software for Macintosh. Image J was used for image processing. Cell counts from the dorsohippocampal CA1 subfield was performed using three sections per mouse. For each capture, cell counts were performed within a 100-μm2 grid three times for each CA1. The measures for each capture were averaged to give the number of pErk+ and FDG+ nuclei per 100-μm2 area.

Data analysis

Statistically significant differences were determined by one- (molecular analyses, factor Group) or two-way ANOVA (behavioral analyses, Group × Test interactions) followed by Scheffe's test for post-hoc comparisons. The results are presented as mean ± S.E.M.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Eva Redei and Dr. Susan Mineka for reading and discussing the manuscript and Dan Sylvester for assistance with the preparation of the manuscript. This study was supported by the NIMH grants MH073669, MH078064, and Dunbar Funds to J.R.

Footnotes

Article is online at http://www.learnmem.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/lm.1240109.

References

- Baeyens F., Eelen P., Van den Bergh O. Contingency awareness in evaluative conditioning: A case for unaware affective-evaluative learning. Cogn. Emotion. 1990;4:3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Blechert J., Michael T., Williams S.L., Purkis H.M., Wilhelm F.H. When two paradigms meet: Does evaluative learning extinguish in differential fear conditioning? Learn. Motiv. 2008;39:58–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bouton M.E. Context and behavioral processes in extinction. Learn. Mem. 2004;11:485–494. doi: 10.1101/lm.78804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang R.C., Stout S., Miller R.R. Comparing excitatory backward and forward conditioning. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. B. 2004;57:1–23. doi: 10.1080/02724990344000015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Garelick M.G., Wang H., Lil V., Athos J., Storm D.R. PI3 kinase signaling is required for retrieval and extinction of contextual memory. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:925–931. doi: 10.1038/nn1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVito P.L., Fowler H. Effects of contingency violations on the extinction of a conditioned fear inhibitor and a conditioned fear excitor. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. Behav. Process. 1986;12:99–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragoi V. A dynamic theory of acquisition and extinction in operant learning. Neural Netw. 1997;10:201–229. doi: 10.1016/s0893-6080(96)00067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg M., Kobilo T., Berman D.E., Dudai Y. Stability of retrieved memory: Inverse correlation with trace dominance. Science. 2003;301:1102–1104. doi: 10.1126/science.1086881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer A., Sananbenesi F., Schrick C., Spiess J., Radulovic J. Distinct roles of hippocampal de novo protein synthesis and actin rearrangement in extinction of contextual fear. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:1962–1966. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5112-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer A., Radulovic M., Schrick C., Sananbenesi F., Godovac-Zimmermann J., Radulovic J. Hippocampal Mek/Erk signaling mediates extinction of contextual freezing behavior. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2007;87:149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haselgrove M., Aydin A., Pearce J.M. A partial reinforcement extinction effect despite equal rates of reinforcement during Pavlovian conditioning. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. Behav. Process. 2004;30:240–250. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.30.3.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermans D., Vansteenwegen D., Crombez G., Baeyens F., Eelen P. Expectancy-learning and evaluative learning in human classical conditioning: Affective priming as an indirect and unobtrusive measure of conditioned stimulus valence. Behav. Res. Ther. 2002;40:217–234. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins W.O., Stanley J.C., Jr Partial reinforcement: A review and critique. Psychol. Bull. 1950;47:193–234. doi: 10.1037/h0060772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Lee S., Park K., Hong I., Song B., Son G., Park H., Kim W.R., Park E., Choe H.K., et al. Amygdala depotentiation and fear extinction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007;104:20955–20960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710548105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight D.C., Smith C.N., Cheng D.T., Stein E.A., Helmstetter F.J. Amygdala and hippocampal activity during acquisition and extinction of human fear conditioning. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2004;4:317–325. doi: 10.3758/cabn.4.3.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattal K.M., Radulovic J., Lukowiak K. Extinction: [corrected] Does it or doesn't it? The requirement of altered gene activity and new protein synthesis. Biol. Psychiatry. 2006;60:344–351. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.H., Choi J.H., Lee N., Lee H.R., Kim J.I., Yu N.K., Choi S.L., Lee S.H., Kim H., Kaang B.K. Synaptic protein degradation underlies destabilization of retrieved fear memory. Science. 2008;319:1253–1256. doi: 10.1126/science.1150541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leussis M.P., Bolivar V.J. Habituation in rodents: A review of behavior, neurobiology, and genetics. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2006;30:1045–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Likely D., Schnitzer S.B. Dependence of the overtraining extinction effect on attention to runway cues. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 1968;20:193–196. doi: 10.1080/14640746808400148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman J.E., Grace A.A. The hippocampal-VTA loop: Controlling the entry of information into long-term memory. Neuron. 2005;46:703–713. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond P.F. Cognitive processes in extinction. Learn. Mem. 2004;11:495–500. doi: 10.1101/lm.79604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackintosh N. The psychology of animal learning. Academic Press; London, U.K: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- McCain G., Lee P., Powell N. Extinction as a function of partial reinforcement and overtraining. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 1962;55:1004–1006. doi: 10.1037/h0045490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta M.R. Neuronal dynamics of predictive coding. Neuroscientist. 2001;7:490–495. doi: 10.1177/107385840100700605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers K.M., Davis M. Behavioral and neural analysis of extinction. Neuron. 2002;36:567–584. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01064-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji B.O., Forsyth J.P., Cherian A. Evaluative differential conditioning of disgust: A sticky form of relational learning that is resistant to extinction. J. Anxiety Disord. 2007;21:820–834. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang M., Thomas S.A. A requirement for memory retrieval during and after long-term extinction learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005;102:9347–9352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502315102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce J.M., Hall G. A model for Pavlovian learning: Variations in the effectiveness of conditioned but not of unconditioned stimuli. Psychol. Rev. 1980;87:532–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploghaus A., Tracey I., Clare S., Gati J.S., Rawlins J.N., Matthews P.M. Learning about pain: The neural substrate of the prediction error for aversive events. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2000;97:9281–9286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160266497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploghaus A., Narain C., Beckmann C.F., Clare S., Bantick S., Wise R., Matthews P.M., Rawlins J.N., Tracey I. Exacerbation of pain by anxiety is associated with activity in a hippocampal network. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:9896–9903. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-24-09896.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prados J., Sansa J., Artigas A.A. Partial reinforcement effects on learning and extinction of place preferences in the water maze. Learn. Behav. 2008;36:311–318. doi: 10.3758/LB.36.4.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radulovic J., Kammermeier J., Spiess J. Relationship between fos production and classical fear conditioning: Effects of novelty, latent inhibition, and unconditioned stimulus preexposure. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:7452–7461. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-18-07452.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radulovic J., Ruhmann A., Liepold T., Spiess J. Modulation of learning and anxiety by corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) and stress: Differential roles of CRF receptors 1 and 2. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:5016–5025. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-12-05016.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla R., Wagner A. A theory of Pavlovian conditioning: Variations in the effectiveness of reinforcement and nonreinforcement. In: Black A., Prokasy W., editors. Classical conditioning II: Current research and theory. Appleton–Century Crofts; New York: 1972. pp. 64–99. [Google Scholar]

- Ross R.T. Pavlovian second-order conditioned analgesia. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. Behav. Process. 1986;12:32–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu J., Futai K., Feliu M., Weinberg R., Sheng M. Constitutively active Rap2 transgenic mice display fewer dendritic spines, reduced extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling, enhanced long-term depression, and impaired spatial learning and fear extinction. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:8178–8188. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1944-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sananbenesi F., Fischer A., Schrick C., Spiess J., Radulovic J. Mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in the hippocampus and its modulation by corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 2: A possible link between stress and fear memory. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:11436–11443. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-36-11436.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton R.S., Barto A.G. Reinforcement learning: An introduction. The MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Szapiro G., Vianna M.R., McGaugh J.L., Medina J.H., Izquierdo I. The role of NMDA glutamate receptors, PKA, MAPK, and CAMKII in the hippocampus in extinction of conditioned fear. Hippocampus. 2003;13:53–58. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiels E., Kanterewicz B.I., Norman E.D., Trzaskos J.M., Klann E. Long-term depression in the adult hippocampus in vivo involves activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and phosphorylation of Elk-1. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:2054–2062. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-02054.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronson N.C., Schrick C., Fischer A., Sananbenesi F., Pages G., Pouyssegur J., Radulovic J. Regulatory mechanisms of fear extinction and depression-like behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1570–1583. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vansteenwegen D., Francken G., Vervliet B., De Clercq A., Eelen P. Resistance to extinction in evaluative conditioning. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. Behav. Process. 2006;32:71–79. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.32.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vianna M.R., Szapiro G., McGaugh J.L., Medina J.H., Izquierdo I. Retrieval of memory for fear-motivated training initiates extinction requiring protein synthesis in the rat hippocampus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2001;98:12251–12254. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211433298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner A.R., Siegel L.S., Fein G.G. Extinction of conditioned fear as a function of percentage of reinforcement. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 1967;63:160–164. doi: 10.1037/h0024172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills A.J., Lavric A., Croft G.S., Hodgson T.L. Predictive learning, prediction errors, and attention: Evidence from event-related potentials and eye tracking. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2007;19:843–854. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.5.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winterbauer N.E., Balleine B.W. Motivational control of second-order conditioning. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. Behav. Process. 2005;31:334–340. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.31.3.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G.Y., Deisseroth K., Tsien R.W. Spaced stimuli stabilize MAPK pathway activation and its effects on dendritic morphology. Nat. Neurosci. 2001;4:151–158. doi: 10.1038/83976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T., Ebisuya M., Ashida F., Okamoto K., Yonehara S., Nishida E. Continuous ERK activation downregulates antiproliferative genes throughout G1 phase to allow cell-cycle progression. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:1171–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]