Abstract

The relationship among gender identity, sex typing, and adjustment has attracted the attention of social and developmental psychologists for many years. However, they have explored this issue with different assumptions and different approaches. Generally the approaches differ regarding whether sex typing is considered adaptive versus maladaptive, measured as an individual or normative difference, and whether gender identity is regarded as a unidimensional or multidimensional construct. In this chapter, we consider both perspectives and suggest that the developmental timing and degree of sex typing, as well as the multidimensionality of gender identity, be considered when examining their relationship to adjustment.

Whether it is based on sex, skin color, or even determined arbitrarily, membership in a social group exerts a profound influence on human behavior, with both positive and negative implications. Specifically membership in a social group has been shown to promote a positive social identity from which individuals can derive self-esteem and a sense of belongingness or connectedness to others and serve as a buffer during times of stress. However, membership in a social group can also promote negative biases toward out-group members, derogation of in-group members who violate group norms, and disengagement from certain areas in which one’s group has been negatively stereotyped (for example, women and math).

Given its obvious implications for psychological well-being, it is not surprising that the study of social group membership has attracted the attention of psychologists. Both social and developmental psychologists have studied the effects of intergroup bias on individuals’ behaviors and self-evaluations, the extent to which identification with a stigmatized group affects well-being, and the influence of group membership on personal choices and behaviors (see Ruble et al., 2004, for a review). Although psychologists have studied a wide range of social group memberships, the documented consequences of belonging to a gender group are among the most studied and most controversial. Within the domain of gender, psychologists have devoted considerable attention to the relationship between gender and well-being, and one issue in particular—the relationship between adherence to gender norms and adjustment—has elicited different assumptions and different approaches among social and developmental psychologists. Broadly, the divergence in perspectives can be characterized in terms of whether sex typing is considered adaptive or maladaptive, described as an individual or normative difference, and whether gender identity is regarded as a unidimensional or multidimensional construct.

In this chapter, we address the three themes of this volume: interdisciplinarity in the study of identity development, developmental processes, and the intersection between personal and social identities. To address each theme, we review perspectives on the relationship between sex typing and adjustment. Specifically, we consider past conclusions that sex typing may be adaptive or maladaptive.

In terms of the development and interdisciplinary themes, we consider how differences in both the measurement of sex typing and the conceptualization of gender identity across different disciplinary fields may lead researchers to different conclusions regarding their implications for well-being. To this end, we examine how researchers have historically thought about the connection between gender identity, adherence to gender norms, and adjustment outcomes. We will also examine the ways in which researchers have measured adherence to gender norms and why it is important to conceive of sex typing as the product of both individual differences and normative developmental processes.

Typically sex typing has been studied from either an individual or normative difference point of view; these perspectives have rarely been considered together. Social psychologists have generally focused on documenting individual differences in sex typing in adulthood (Bem, 1974). In contrast, developmental psychologists have mostly concentrated on understanding normative changes in sex typing, particularly those occurring during early childhood (Kagan, 1964; Kohlberg, 1966). However, individual and normative differences in sex typing are relevant throughout the life span. A primary theme in the analysis here is that the impact of individual and normative differences on adjustment differs in accordance with developmental phases. In particular, we explore how individual and normative differences in sex typing affect adjustment differently during early and middle childhood.

To address the intersection-of-identities theme, we consider the implications of recognizing gender identity as multidimensional for the relationship between social identity and personal adjustment. Multidimensionality may be conceptualized in a variety of ways, but broadly it refers to the idea that social identity reflects knowledge of group membership along with a variety of beliefs about group membership (Ashmore, Deaux, & McLaughlin-Volpe, 2004). Thus, gender identity may be conceptualized as both categorical knowledge (“I’m a boy/girl”) and feelings regarding the importance (“Being a boy/girl is really important to me”) and evaluation (“I like being a boy/girl”) of that group membership. This perspective has been shown to be important for understanding the impact of both racial and gender identity on adjustment (Egan & Perry, 2001; Sellers, Smith, Shelton, Rowley, & Chavous, 1998; Brown & Tappan, Chapter Four). In the discussion, we aim to advance the idea that the meaning individuals ascribe to their gender identity is critically important for understanding the relationship between adherence to gender norms and well-being.

Historical Perspective on Gender Identity, Sex Typing, and Adjustment

Initially developmental psychologists defined gender identity as the extent to which an individual feels masculine or feminine. Feeling masculine or feminine was assumed to be important to children and to depend on adherence to cultural standards of masculinity or femininity. In essence, it was believed that the presence of sex typing was necessary for possessing a secure sense of self as male or female. Moreover, researchers thought that individuals whose behavior matched sex role prescriptions were more likely to be psychologically well adjusted because they would be fulfilling a psychological need to conform to internalized cultural standards of gender. Thus, sex typing was viewed as not only normal but optimal, whereas cross-sex typing was viewed as deviant and potentially harmful to well-being (Kagan, 1964). Bem (1974, 1981), however, challenged this perspective, arguing that the need to adhere to an internalized standard of gender would promote negative, not positive, adjustment.

Unlike Kagan (1964), who attributed the development of sex typing in part to identification with the same-sex parent, Bem (1981) believed that sex typing resulted from the salient and functional use of gender in society. Specifically Bem thought that societal gender distinctions led people to develop gender schemas, or associative mental networks linking certain behaviors to either men or women. The contents of these schemas were theorized to function as standards people would use to evaluate whether they were adequate representations of their gender group. Thus for Bem, the extent to which people were sex typed was indicative of the extent to which they were gender schematic or had internalized culturally prescribed gender norms. So although Bem agreed that people were motivated to adhere to internalized cultural standards of gender, in contrast to Kagan, she believed that this tendency would result in behavioral inflexibility and therefore maladjustment. (Subsequent support for Bem’s idea that androgyny is associated with better adjustment has been mixed. Thus, the extent to which androgyny is beneficial for adjustment remains unclear. See Ruble & Martin, 1998, for further discussion.)

Although subsequent research (Spence & Helmreich, 1980) critiqued Bem’s assessment of masculinity/femininity, Bem’s perspective (1974, 1981) has influenced developmental and social psychologists in a number of ways. Specifically, Bem, along with other researchers (Liben & Signorella, 1980; Martin & Halverson, 1981), popularized the notion of gender schemata as a key mechanism promoting the development of sex-typed behavior. To this day, the construct of gender schemata remains highly important to cognitive theories of gender development (Martin, Ruble, & Szkrybalo, 2002; Ruble, Martin, & Berenbaum, 2006). Moreover, Bem pioneered the practice of measuring masculinity and femininity separately, operationalizing the concept of androgyny and influencing later theorizing about the implications of sex typing. Bem’s assertion that sex typing is maladaptive and ultimately serves to restrict people’s behaviors inspired numerous studies and changed the way in which researchers framed the relationship between sex typing and adjustment, with sex role flexibility becoming the optimal standard (Ruble & Martin, 1998). Yet, the relationship of gender identity, sex typing, and adjustment may not be as straightforward as Bem theorized.

Sex Typing: Individual Versus Normative Differences

Bem’s (1981) perspective on the potentially negative consequences of being highly sex typed is primarily based on analyses relating individual differences in sex typing to adjustment. Specifically, Bem (1974) identified individuals as highly sex typed by measuring the extent to which they reported possessing more same-sex compared to opposite-sex traits. Although this method of quantifying differences in sex typing is legitimate, it treats sex typing as a relatively stable characteristic without regard to its developmental context. That is, across development, children may differ relative to each other (for example, child X is more sex typed than child Y) and to themselves in terms of sex typing (child X is more sex typed at age five than at age three). Indeed, for many decades, developmental psychologists have devoted considerable attention to documenting normative changes in sex typing.

In one of the most influential works on the mechanisms underlying the adoption of sex-typed behavior in children, Kohlberg (1966) theorized that knowledge of one’s gender category membership (“I am a boy/girl”) and the achievement of gender constancy (“Boys will grow up to be men; a boy is still a boy even if he wears a dress”) are critical components underlying the expression of sex-typed beliefs and behaviors. Although Kohlberg’s ideas remain controversial (see Bandura & Bussey, 2004; Bussey & Bandura, 1999), they continue to influence how developmental researchers think about the relationship between sex typing and gender identity (see Martin et al., 2002). It is important to note that while both Kohlberg and Bem’s (1981) theories presume that gender identity and sex typing are inherently linked, Kohlberg was mostly interested in the relationship between gender identity and sex typing in childhood, whereas Bem was primarily concerned with the implications of sex typing for adjustment among adults. Following in Kohlberg’s footsteps, cognitive developmental researchers have generally directed their efforts toward documenting a relationship between gender knowledge (“I’m a boy/girl”) and age-related increases in sex typing. Similarly, developmental researchers interested in gender schemata have generally been more concerned with understanding how children construct their schemata and whether this leads to increases in sex typing. Neither approach has given much consideration to how potentially rigid sex typing affects adjustment (Martin et al., 2002; Ruble et al., 2006). Perhaps this is because rigidity in children’s beliefs and behaviors in general has long been recognized as a hallmark of development and consequently has not generally been viewed as especially problematic for adjustment.

Numerous theoretical and empirical analyses suggest that differences in the flexibility versus rigidity of individuals’ sex-typed beliefs reflect not only individual differences in beliefs about gender norms but also normative developmental trajectories. For example, Ruble (1994) suggests that as children come to understand that gender is an important social category, their beliefs about gender progress through three phases. During the initial phase, construction, children are mostly concerned with seeking gender-relevant information and, due to their possession of a relatively incomplete amount of gender knowledge, will not react strongly to gender norm violations. In contrast, during the second phase, consolidation, children have a well-developed set of gender stereotypes and exhibit a peak in the rigidity of their gender beliefs. In the final phase, integration, children apply gender-related information more flexibly compared to the previous phase and may show individual differences in their gender cognitions and schemata.

The results from a recent longitudinal study support these assertions. In this study, children showed a peak in the rigidity of their application of gender stereotypes at five or six years, but by age seven began to show dramatic increases in flexibility. In addition, regardless of the level of rigidity between five and seven years, children previously high or low in rigidity showed no differences in flexibility by age eight, suggesting that this pattern of early rigidity followed by increasing flexibility represents a normative developmental process (Trautner et al., 2005).

Multidimensionality of Gender Identity

Although Kagan (1964) and Bem (1981) differed in terms of the mechanisms believed to promote sex typing and whether or not sex typing is adaptive or maladaptive, both perspectives posit that sex typing is indicative of gender identity. Although it is not an unreasonable idea, recent work examining the nature of identity suggests that it may be much more complex than the degree to which people adhere to gender norms. Contemporary perspectives on identity challenge the utility of relying on one construct or type of measurement as a means for assessing the nature of a particular identity (Ashmore et al., 2004; Egan & Perry, 2001; Sellers et al., 1998; Way, Santos, Niwa, Kim-Gervey, Chapter Five). Specifically, researchers have proposed that social identities are made up of various components, each with important implications for particular outcomes (Ruble et al., 2004). Although psychologists differ in the aspects of identity they emphasize, current research points to three dimensions worth careful consideration when thinking about gender identity, sex typing, and adjustment: centrality, evaluation, and felt pressure. (Centrality refers to the importance of gender to one’s identity; evaluation refers to how one views gender-related values, beliefs, roles, and behavioral practices in one’s culture; and felt pressure refers to one’s perceptions of the need to conform to these cultural values, beliefs, roles, and behavioral practices.)

Although gender may be among the most important social categories in American society, individuals may differ in the degree to which they consider it an important and positive aspect of their overall identity. Research has shown that children differ in predictable ways with respect to which aspects of their overall identity they consider most important. For example, ethnicity is more central to the self-concept of immigrant compared to non-immigrant American children. Moreover, research has shown that children may differ in the extent to which they are happy with their gender and feel pressure from themselves and others (parents and peers) to behave in a sex-typed manner. Thus, centrality, evaluation, and felt pressure have all been shown to be important factors in the relationship between group membership and self-esteem (Ruble et al., 2004).

Our Study

Recent work in our lab has been directed toward considering the impact of children’s rigid sex-typed beliefs from individual difference, developmental, and multidimensional perspectives. Specifically we examined whether the implications of rigid sex-typed beliefs for adjustment differed depending on whether we (1) conceptualized children’s rigid sex-typed beliefs as reflecting individual or normative differences and (2) considered the extent to which children regard gender as a central and positive aspect of their self-concept. Although a peak in rigidity is a hallmark of the consolidation phase, children may nevertheless vary in the degree to which they exhibit rigid sex-typed beliefs. Moreover, the impact of individual differences in rigidity may differ depending on whether children are highly rigid relative to their peers prior to or after reaching peak rigidity. The impact of rigid sex-typed beliefs on adjustment may also vary depending on whether children perceive their gender group membership as an important and positive aspect of themselves.

To explore these issues, we conducted interviews with children at two different time points. At time 1, children (n = 95) were between three and seven years of age (M = 5.14), and at wave 2 (n = 59), they were between seven and thirteen years of age (M = 10.27). The overwhelming majority of participants were white, precluding us from examining any differences by ethnicity. At both time points, we measured children’s sex role rigidity by assessing their reactions to other children’s gender norm violations (a girl [boy] who plays with trucks [dolls]), feelings of gender centrality (“Being a girl is a big part of who I am”), and evaluation (“I am proud to be a girl”) (see Ruble et al., 2007, for a full description of these measures), and global self-worth (Harter, 1985). We decided to measure rigidity in this way primarily because Bem’s (1974) measures have not been adapted for preschool children, and children’s reactions to gender norm violations are a plausible indicator of the extent to which they have internalized culturally prescribed gender norms.

Individual and Normative Differences

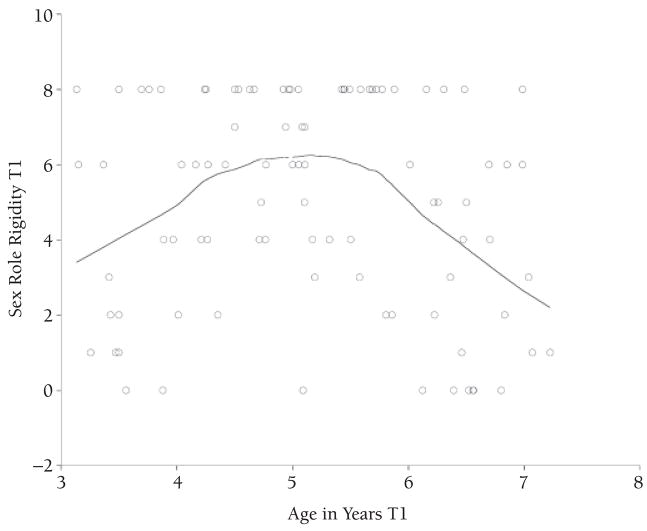

To identify periods before and after peak rigidity, we created smoothed Loess plots with age as the independent variable and sex role rigidity as the dependent variable. Inspection of the plots demonstrated the familiar curvilinear pattern of children showing a peak in sex role rigidity around five years followed by a decline shortly after (see Figure 3.1). To account for these different trends in the data, we divided participants at time 1 into younger (3.13–4.99) (n = 42) and older (5.00–7.30) (n = 53) cohorts as a way of designating times before and after peak rigidity, respectively.

Figure 3.1.

Loess Plot for Age and Sex Role Rigidity at Time 1

We approached the following time analysis with two questions in mind: (1) Does the relationship between rigidity and adjustment differ depending on whether children exhibit rigid sex-typed beliefs before or after reaching peak rigidity? and (2) Is the high rigidity exhibited in younger versus older children less stable? For each question, we predicted that heightened rigidity at time 1 (T1) would be related to adjustment and predict later rigidity, but only when it represented a departure from developmental norms (that is, it was exhibited after peak rigidity).

Although these predictions may appear to conflict with Bem’s (1981) stance that rigidity is associated with poorer adjustment, fluctuations in the rigidity of children’s beliefs reflect a normative developmental process. Thus, we might expect heightened rigidity to be problematic, but only when it represents a departure from developmental norms (that is, it is exhibited after peak rigidity). In addition, whereas heightened rigidity among younger children is consistent with normative increases in the rigidity of sex-typed beliefs, heightened rigidity among older children is out of sync with normative decreases in rigidity. Thus, the effects of heightened rigidity may be relatively short-lived when children are highly rigid before compared to after peak rigidity.

To answer our first question, we examined whether the relationship between rigidity and adjustment differed for younger and older children. Results from our first analysis confirmed that the effect of sex role rigidity on adjustment differed depending on whether children had reached peak rigidity. For participants in the younger cohort, who are unlikely to have reached peak rigidity, sex role rigidity appeared to have little impact on self-worth. However, consistent with Bem’s theory (1981), for participants in the older cohort, who should have already reached peak rigidity, sex role rigidity was negatively associated with self-worth. This basic pattern of results remained the same in a follow-up analysis in which we adjusted for age-related differences in rigidity.

To investigate our second question, we conducted separate analyses for each cohort to examine whether participants’ level of sex role rigidity at time 1 was associated with their level of sex role rigidity at time 2. Because participants were interviewed at time 2 anywhere from approximately 3.5 to 6.0 years after time 1, we adjusted for the length of time between interviews. For the younger cohort, there was no relationship between rigidity at time 1 and rigidity at time 2. However, for the older cohort, high rigidity at time 1 predicted high rigidity at time 2. These results make sense in the light of the previous analyses. Specifically, if individual differences in rigidity prior to peak rigidity are relatively fleeting, it seems reasonable that they may not relate to adjustment. Similarly, for the older cohort, if individual differences in rigidity after peak rigidity represent a more stable difference, we might expect this to have a significant impact on adjustment.

Because there are normative developmental changes in the older as well as the younger cohort, it may seem surprising that we found a relationship between rigidity and adjustment for the older cohort. One explanation is that although becoming highly rigid is a normal part of development, the briefer the time during which children are at their peak rigidity or the steeper the decline in peak rigidity, the better. One possible reason for this is that the longer or the later children show rigidity, the greater the overlap is between their rigid insistence on adherence to gender norms and the first years of elementary school, when peer relationships become more complex and require a wider range of social skills. Thus, consistent with Bem’s (1981) ideas regarding the detrimental effects of rigidity, children who remain rigid for longer may miss out on opportunities to develop certain skills associated with the opposite sex (for example, girls learning to be assertive, boys learning to be cooperative) that may be beneficial for adjustment. In addition, after reaching peak rigidity, the extent to which children are high in rigidity relative to each other may be related to other types of gender-related individual differences (say, the extent to which children feel pressured to adhere to gender norms) and more general social cognitive differences (such as understanding others’ mental states) that might be important for adjustment.

Heightened rigidity is also developmentally appropriate for younger children, whereas for older children, it represents a departure from developmental norms, and thus may have significant consequences for peer relationships and therefore adjustment. For example, because young children as a group are generally intolerant of gender norm violations, they likely share their maintenance of gender boundaries with other children, which may help to promote peer relationships. However, older children who are less tolerant of departures from gender norms are probably more of a minority among similar-age peers and therefore may be viewed as unfriendly or mean. Thus, we believe our results suggest that it is important to consider not only whether an individual holds rigid sex-typed beliefs relative to others but also the timing and stability of such differences.

Centrality/Evaluation and Felt Pressure

To explore whether the relationship between sex typing and adjustment depends on the extent to which participants consider gender an important and positive aspect of their identities, we conducted another series of analyses with data from time 1. Because the results from our previous analyses showed that the impact of individual differences in sex role rigidity depended on whether participants were showing greater differences before or after peak rigidity, analyses were conducted separately for each cohort. For analyses of both the younger and older cohorts, we examined the relationship of self-worth, sex, sex role rigidity, and centrality/evaluation.

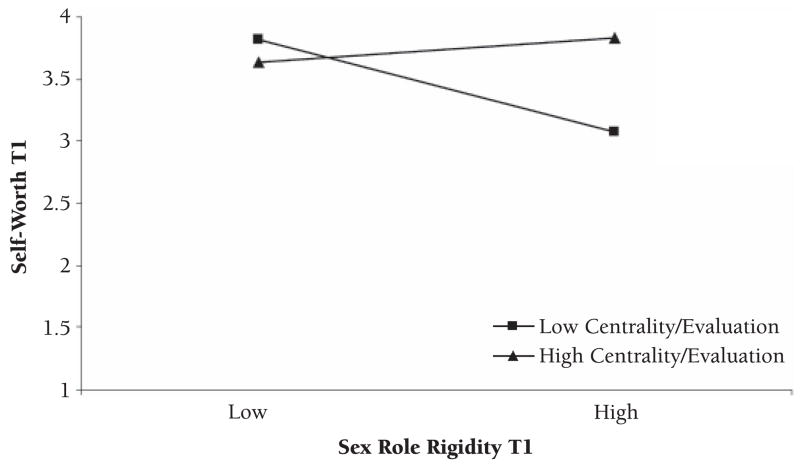

Consistent with our previous results, no significant effects emerged for the younger cohort. However, for the older cohort, results showed that high sex role rigidity was negatively associated with self-worth, but only when centrality/evaluation was also low (see Figure 3.2). In other words, children who had more rigid beliefs about how girls or boys should behave had lower levels of self-worth, but only if gender was not an important part of their identities. We speculate that these results make sense if we consider that centrality/evaluation may also reflect the extent to which individuals embrace the values and behaviors for their gender group. Thus, we would not necessarily expect high sex role rigidity to be bad for adjustment for those high in centrality/evaluation because adhering to gender norms may be congruent with personal standards of behavior. However, if individuals do not embrace gender norms yet have rigid beliefs about how they should conform to them, it seems plausible that such a combination would be associated with negative adjustment.

Figure 3.2.

Predicted Values for Self-Worth as a Function of Sex Role Rigidity and Centrality/Evaluation for Participants in the Older Cohort

Results from the second wave (time 2) of data collection are relevant to this point: although sex role rigidity was positively associated with felt pressure (“I think my parents would mind if I wanted to do things that only girls [boys] do”), centrality/evaluation was not. The lack of relationship between centrality/evaluation and felt pressure suggests that embracing and valuing the behaviors of one’s gender group is distinct from pressure to adhere to gender norms. These results are in line with distinctions made by other researchers (Egan & Perry, 2001) between felt compatibility with one’s gender group and felt pressure to adhere to gender norms. Moreover, our data are consistent with the spirit of Bem’s (1981) theory, which implies that the pressure felt as a consequence of needing to match behaviors to an internalized standard of gender may be problematic. Importantly, research shows that felt pressure is associated with lower levels of self-worth in both middle childhood (Egan & Perry, 2001) and early adolescence (Smith & Leaper,v).

We should also point out that although we did not find different patterns for boys and girls in terms of the impact of sex typing on adjustment in either set of analyses, such differences may emerge later in life. Specifically, in a study with high school students, results showed that in the public context of school, feminine girls experienced greater loss of voice, expressing their opinions less, compared to androgynous girls. Boys showed a different pattern in that masculine boys reported higher levels of voice with male classmates compared to androgynous boys, who in turn reported higher levels of voice with close friends compared to masculine boys. Importantly, loss of voice is associated with lower levels of self-worth. Thus, these differences between girls and boys regarding their level of voice suggest that the impact of sex typing on adjustment may differ by gender during different developmental periods and across different contexts (Harter, Waters, Whitesell, & Kastelic, 1998).

Conclusion

Throughout this chapter, we have suggested that the relationship of sex typing, gender identity, and adjustment may not be as straightforward as prior theories have suggested. Specifically, we have proposed that in order to clarify the relationship of these constructs, it is important to consider individual differences in sex typing within the context of normative developmental processes and the multidimensional nature of gender identity. We believe our results have important implications for the main themes of this volume: (1) processes of identity development, (2) the intersection of personal and social identities, and (3) interdisciplinarity in social identity research.

With respect to developmental processes, our longitudinal analyses indicate that the stability and consequences of social (gender) identity may differ dramatically for children who are pre- versus post-peak rigidity. For example, individual differences in sex role rigidity showed stability over time and related to self-esteem only for children past peak rigidity. These findings raise interesting questions and have important theoretical implications for how we understand the consequences of sex typing. Specifically, what is it about the developmental period after peak rigidity that contributes to the greater stability and impact of sex typing on adjustment? As we suggested, one possibility concerns changing values and standards for children’s peer relationships and interactions. However, many other possibilities exist, and it will be important for future research to examine more precisely those factors underlying the different patterns and implications of social identity across development. In addition, theories about the significance of individual differences in sex typing will need to ground their analyses more carefully in terms of normative developmental processes.

With respect to the intersection of personal and social identity, our results suggest that the nature of children’s thinking about their gender group membership is far richer than has traditionally been recognized, in ways that are important for connecting various outgrowths of their gender identity (sex typing) to their self-concept and self-esteem. Specifically, our data suggest that it is not only the degree to which children adhere to gender norms, but also the extent to which they consider gender an important or positive aspect of their self-concept that predicts well-being. How the multidimensional nature of gender identity affects children’s overall self-concept is an interesting issue. For example, will the self-concept of children for whom gender is a less central and less positive aspect of their identity be more resistant to gender stereotypes? More specifically, when encountering gender stereotypes such as, “girls are bad at math” or “boys play rough,” will girls and boys who consider gender neither important nor positive be less likely to infer that they will be bad at math or should play rough, respectively? In addition, the feelings of importance and evaluation children ascribe to their gender seem like plausible mechanisms for promoting the development of sex segregation—the child-driven phenomenon in which children prefer to exclusively play with same-sex peers—which in turn may influence the areas children identify as relevant bases for their self-concept (looking feminine versus being good at sports).

Consideration of how gender identity intersects with other identities like ethnicity or class is important for fully understanding the ramifications of sex typing for adjustment (see Chapter Four, this volume). Unfortunately, the makeup of our sample did not allow us to explore differences in gender identity across ethnicity and class. However, it is important that future research explore the ways in which children’s gender identities differ in concert with various combinations of ethnic and class identities. Variations by ethnicity and class in the ways in which people define gender could also have important implications for the relationship between sex typing and adjustment. For example, in their study of an ethnically diverse, low-income sample of adolescent boys, Santos, Way, and Hughes (2007) found that boys who adhered more to norms of masculinity had lower self-esteem. On the one hand, this finding makes sense because masculinity stresses a variety of antisocial behaviors such as physical aggression. However, many socially adaptive behaviors, such as assertiveness, define masculinity as well. The same can be said for femininity as it is defined by both potentially adaptive (nurturance) and maladaptive (submissiveness) behaviors. But what determines whether children use adaptive or maladaptive aspects of gender to define what it means to be a boy or a girl? One possibility is that children from different ethnic and socioeconomic groups define being a girl or a boy differently. For example, research shows that gender roles and concepts differ across ethnic and socioeconomic groups (Ruble et al., 2006). Thus, children from different ethnic and socioeconomic groups may have different ideas about what it means to be a boy or a girl and therefore vary in the extent to which they subscribe to adaptive or maladaptive aspects of masculinity or femininity. In short, it seems likely that the consequences of rigid adherence to gender norms differ in accordance with children’s gender, ethnic, and socioeconomic group memberships.

In addition, it is important to consider the context in which children derive meaning from their gender identity. For example, in a high school in which Puerto Rican students were at the top of the social pecking order, Puerto Rican students felt positive about their ethnic identity. In contrast, Chinese students, who ranked at the bottom of the social hierarchy, felt much less positive about their ethnic identity. Interestingly, Dominican students, who ranked second highest in the social hierarchy, negotiated their ethnic identities in reference to the stereotypes conferred on them by their more dominant Puerto Rican peers. Thus, context affected how adolescents felt about their ethnic identity as well as how they defined it (Chapter Five, this volume).

With respect to interdisciplinarity in research on identity, we have employed both social and developmental perspectives in our work. In this chapter, we have argued that consideration of both individual and normative differences in sex typing, along with the recognition of gender identity as a multidimensional construct, is essential for understanding the relationship between sex typing and adjustment. However, despite a plethora of theoretical models positing important changes throughout life, developmental psychologists, for a variety of reasons, have primarily concerned themselves with childhood and adolescence, and social psychologists have primarily focused on adulthood (Ruble & Goodnow, 1998). An integrative interdisciplinary perspective forces us to study people across the life span and recognize the social and developmental factors relevant to the study of identity at all ages.

An interdisciplinary life span perspective seems ripe for exploration as empirical work shows that when adopting a new identity, both children and adults display the same curvilinear pattern of increasing rigidity of beliefs followed by later flexibility (Ruble, 1994). However, the extent to which adults may show a pattern similar to what our data show for children is an open question. Some research demonstrates an increase in gender traditionality during middle and late adolescence, suggesting that the intensity of sex typing continues to fluctuate well beyond childhood (Crouter, Whiteman, McHale, & Osgood, 2007). Thus, examining whether the intensity of sex typing continues to wax and wane throughout adulthood may represent a potentially fruitful line of inquiry. For instance, the relationship between sex typing and adjustment may differ across the life span because rigid sex-typed beliefs and behaviors during elementary school may manifest themselves in ways that are less directly related to adjustment (for example, believing that only girls should play with dolls) compared to high school or college (for example, believing that only men should be assertive and that women are less skilled at math). Furthermore, developmental and contextual differences in centrality, evaluation, and felt pressure may work to influence the relationship between sex typing and adjustment. For example, as girls begin to recognize that femininity is devalued relative to masculinity in American culture, the extent to which they believe being a girl is an important or positive aspect of their identity may decline. In addition, felt pressure to adhere to gender norms may be particularly detrimental for girls who feel pressure to be feminine but recognize that American culture grants less power and status to femininity (see also Chapter Four, this volume).

A developmental perspective on social identity and adjustment will also be enriched by a greater incorporation of social psychologists’ emphasis on process. That is, what exactly is it about rigidity that may result in poor adjustment? Bem (1981) explicitly stated that rigid adherence to gender norms interferes with the ability to react adaptively across situations, especially when the required behavior violates gender norms. However, the data used to support this claim only suggest that sex-typed individuals are uncomfortable stepping outside their gender role (Bem & Lenney, 1976). Such an explanation for the consequences of rigidity seems incomplete. People may be rigidly sex typed but for different reasons, and these reasons might hold different implications for developmental outcomes. For example, some people may rigidly adhere to gender norms because they want to avoid negative outcomes related to violating gender norms (for example, wearing a feminine outfit to avoid being criticized for being unfeminine or looking unattractive), while others may want to maximize the positive benefits associated with being gendered (for example, wearing a feminine outfit because of a desire to be admired for being feminine and perceived as attractive). This distinction is consistent with the two primary motivational orientations described in regulatory focus theory, an influential social psychological theory. This theory posits that people can be described as being either prevention or promotion focused. While individuals with a prevention focus are particularly concerned with avoiding negative outcomes, individuals with a promotion focus are concerned with obtaining positive outcomes (Higgins, 2000). According to this theory, differences in regulatory focus may foster different motives for engaging in gender normative behavior. For example, we might expect prevention-focused women to insist on wearing a feminine outfit because they do not want to be socially rejected, whereas promotion-focused women may be primarily concerned with gaining social acceptance. People with different orientations may react quite differently when forced to step outside their gender role, which may be important for understanding the relationship between sex typing and adjustment.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that the relationship of sex typing, gender identity, and adjustment is not as straightforward as originally believed. Both the timing and degree of rigidity deserve consideration when examining the relationship between sex typing and adjustment. Furthermore, our data demonstrate that, consistent with contemporary theories of identity, the multidimensional nature of gender identity has important implications for the circumstances under which sex typing may be adaptive versus maladaptive. Rather than asking whether sex typing and gender identity are good or bad for adjustment, we encourage researchers to revisit previous conclusions about the nature of the relationship of sex typing, gender identity, and adjustment, keeping in mind the diverse ways in which they may be conceptualized and relate to each other.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (5RO1HD049994) awarded to Diane N. Ruble.

Contributor Information

Leah E. Lurye, doctoral student at New York University, New York

Kristina M. Zosuls, doctoral student at New York University, New York

Diane N. Ruble, professor of psychology at New York University, New York

References

- Ashmore RD, Deaux K, McLaughlin-Volpe T. An organizing framework for collective identity: Articulation and significance of multidimensionality. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:80–114. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, Bussey K. On broadening the cognitive, motivational, and socio-cultural scope of theorizing about gender development and functioning: Comment on Martin, Ruble, and Szkrybalo (2002) Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:691–701. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.5.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bem SL. The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1974;42:155–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bem SL. Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex typing. Psychological Review. 1981;88:354–364. [Google Scholar]

- Bem SL, Lenney E. Sex typing and the avoidance of cross-sex behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1976;33:48–54. doi: 10.1037/h0078640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussey K, Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of gender development and differentiation. Psychological Review. 1999;106:676–713. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.106.4.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouter AC, Whiteman SD, McHale SM, Osgood WD. Development of gender attitude traditionality across middle childhood and adolescence. Child Development. 2007;78:911–926. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan SK, Perry DG. Gender identity: A multidimensional analysis with implications for psychosocial adjustment. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:451–463. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.4.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The Self-Perception Profile for Children: Revision of the perceived competence scale for children (Manual) Denver, CO: University of Denver; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S, Waters PL, Whitesell NR, Kastelic D. Level of voice among female and male high school students: Relational context, support, and gender orientation. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:892–901. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.5.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET. Making a good decision: Value from fit. American Psychologist. 2000;55:1217–1230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J. A cognitive-developmental analysis of children’s sex-role concepts and attitudes. In: Hoffman ML, Hoffman LW, editors. Review of child development research. Vol. 1. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1964. pp. 137–167. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlberg LA. A cognitive-developmental analysis of children’s sex role concepts and attitudes. In: Maccoby EE, editor. The development of sex differences. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1966. pp. 82–173. [Google Scholar]

- Liben LS, Signorella ML. Gender-related schemata and constructive memory in children. Child Development. 1980;51:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Martin CL, Halverson C. A schematic processing model of sex typing and stereotyping in children. Child Development. 1981;52:1119–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Martin CL, Ruble DN, Szkrybalo J. Cognitive theories of early gender development. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:903–933. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.6.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruble DN. A phase model of transitions: Cognitive and motivational consequences. In: Zanna M, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 26. 1994. pp. 163–214. [Google Scholar]

- Ruble DN, Alvarez JM, Bachman M, Cameron JA, Fuligni AJ, Garcia Coll C, et al. The development of a sense of “we”: The emergence and implications of children’s collective identity. In: Bennett M, Sani F, editors. The development of the social self. East Sussex, England: Psychology Press; 2004. pp. 29–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ruble DN, Goodnow J. Social development from a lifespan perspective. In: Gilbert D, Fiske S, Lindzey G, editors. Handbook of social psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ruble DN, Martin C. Gender development. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3, Social, emotional, and personality development. 5. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 1998. pp. 933–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Ruble DN, Martin CL, Berenbaum SA. Gender development. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3, Social, emotional, and personality development. 6. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2006. pp. 858–932. [Google Scholar]

- Ruble DN, Taylor L, Cyphers L, Greulich FK, Lurye LE, Shrout PE. The role of gender constancy in early gender development. Child Development. 2007;78:1121–1136. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos C, Way N, Hughes D. Patterns of adherence to norms of masculinity in the peer relationships of multi-ethnic adolescent boys. Poster session presented at the Society for Research in Child Development 2007 Biennial Meeting; Boston. 2007. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Smith M, Shelton JN, Rowley SAJ, Chavous TM. Multidimensional model of racial identity: A reconceptualization of African American racial identity. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 1998;2:18–39. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0201_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TE, Leaper C. Self-perceived gender typicality and the peer context during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2005;16:91–103. [Google Scholar]

- Spence JT, Helmreich RL. Masculine instrumentality and feminine expressiveness: Their relationships with sex role attitudes and behaviors. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1980;5:147–163. [Google Scholar]

- Trautner HM, Ruble DN, Cyphers L, Kirsten B, Behrendt R, Hartmann P. Rigidity and flexibility of gender stereotypes in children: Developmental or differential? Infant and Child Development. 2005;14:365–380. [Google Scholar]