Abstract

A growing body of evidence has demonstrated that p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) has a crucial role in various physiological and pathological processes mediated by β2-adrenergic receptors (β2-ARs). However, the detailed mechanism of β2-ARs-induced p38 MAPK activation has not yet been fully defined. The present study demonstrates a novel kinetic model of p38 MAPK activation induced by β2-ARs in human embryonic kidney 293A cells. The β2-AR agonist isoproterenol induced a time-dependent biphasic phosphorylation of p38 MAPK: the early phase peaked at 10 min, and was followed by a delayed phase that appeared at 90 min and was sustained for 6 h. Interestingly, inhibition of the cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) pathway failed to affect the early phosphorylation but abolished the delayed activation. By contrast, silencing of β-arrestin-1 expression by small interfering RNA inhibited the early phase activation of p38 MAPK. Furthermore, the NADPH oxidase complex is a downstream target of β-arrestin-1, as evidenced by the fact that isoproterenol-induced Rac1 activation was also suppressed by β-arrestin-1 knockdown. In addition, early phase activation of p38 MAPK was prevented by inactivation of Rac1 and NADPH oxidase by pharmacological inhibitors, overexpression of a dominant negative mutant of Rac1, and p47phox knockdown by RNA interference. Of note, we demonstrated that only early activation of p38 MAPK is involved in isoproterenol-induced F-actin rearrangement. Collectively, these data suggest that the classic cAMP/PKA pathway is responsible for the delayed activation, whereas a β-arrestin-1/Rac1/NADPH oxidase-dependent signaling is a heretofore unrecognized mechanism for β2-AR-mediated early activation of p38 MAPK.

Numerous data indicate that p38, a member of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)2 family, is implicated in many biological responses mediated by β2-adrenergic receptors (β2-ARs), including modulation of immune, inflammatory, and cardiovascular pathologic processes (1–4). For example, in β2-ARs-overexpressing transgenic mice with cardiomyopathy, cardiac-specific expression of dominant-negative p38α MAPK improved cardiac function and reduces cardiac apoptosis and fibrosis (5).

Generally, β2-ARs are believed to exert their effects through a classic Gs/cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) pathway. Upon β2-ARs stimulation, cAMP/PKA-dependent p38 MAPK activation has been shown in various cells, including macrophages, PC12, MC3T3-E1 cells, Chinese hamster ovary cells, NIH 3T3 cells, adipocytes, and rat cardiac myocytes (6–8). In addition, β2-ARs, also via coupling to Gi, induce activation of p38 MAPK, and subsequently attenuate β-AR-stimulated apoptosis in adult rat cardiac myocytes (9). However, emerging evidence suggests that in some settings, the classical cAMP/PKA-dependent pathway does not fully account for β2-AR-mediated p38 MAPK activation. The cAMP/PKA-independent activation of p38 MAPK has been shown to regulate the expressions of the cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein-2 in colon cancer cells (10) and pituitary hormone prolactin in human T lymphocytes (11). In Raw264.7 cells, inductions of interleukin-1 and interleukin-6 by stimulation of β2-ARs occur mainly though the Exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (Epac), B-Raf/extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK1/2), and the p38 MAPK pathway (12). Furthermore, we also recently demonstrated that in mouse cardiac fibroblasts, both classic cAMP/PKA and Epac/Rap1 routes are not required for p38 MAPK-mediated secretion of interleukin-6 in response to β2-ARs stimulation (13). Although it is well established that β2-AR-activate p38 MAPK in numerous cells and tissues, a detailed understanding of the underlying mechanism remains unknown. This is necessary before the potential benefits of exploiting p38 MAPK as a target of β2-AR agonists can be extrapolated into the therapeutic arena.

The mammalian arrestin family consists of four members: arrestin-1 and -4, and β-arrestin-1 and -2. Of these, β-arrestin-1 and -2 are ubiquitously expressed (14). In addition to their well established role in terminating GPCR signal transduction, accumulating evidence indicates that they can modulate compartmentalization of intracellular cAMP signaling and initiate various cytoplasmic and nuclear signaling cascades (15, 16). For example, binding of β-arrestin-1/2 to components of the ERK1/2 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase 3 cascades allows them to function as scaffolding molecules, thus localizing these kinases activation (17). Importantly, β-arrestin-dependent ERK1/2 activation is implicated in the regulation of chemotaxis and cell survival by altering the profile of gene transcription, in a manner distinct from the classic G-protein-dependent pathway (14, 18).

In the present study we investigate whether β-arrestins are involved in β2-AR-mediated p38 MAPK activation. We show that β2-ARs stimulation induces a biphasic activation (early and delayed) of p38 MAPK, which is distinct from a previously described monophasic model in mast cells (1), fat cells, embryonic chick ventricular cells (4), and adult rat cardiac myocytes (8). Interestingly, early phase activation of p38 MAPK can be prevented by reducing the expression of β-arrestin-1 by siRNA and inhibiting NADPH oxidase activity. By contrast, the classic cAMP/PKA pathway is involved in the delayed activation of p38 MAPK following exposure to isoproterenol.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibodies, Reagents, and Plasmids—Antibodies used included phospho-p38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182), phospho-p42/44 MAPK (Thr202/Tyr204), phospho-HSP27 (Ser82), p47phox and p38β MAPK (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), p38 MAPK (C-20), GAPDH (6C5), β-arrestin-1 (K-16), β-arrestin-2 (H-9), β2-AR (H-73), G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2, C-15), GRK3 (H-43), GRK5 (H-64), and GRK6 (C-20) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibodies and chemiluminescence reagents were from Pierce. TRITC-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG were from Beijing Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology (Beijing, China). Isoproterenol, ICI 118551, propranolol, (Rp)-cAMP, 8-(4-chlorophenylthio)-2′-O-methyl cyclic AMP (8-pCPT-2Me-cAMP), H89, KT5720, SQ22536, isobutylmethylxanthine, and SB202190 were from Sigma. Clostridium difficile Toxin B (Toxin B), NSC23766, Y27632, diphenyleneiodonium chloride (DPI), apocynin, and rotenone were from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). 5-(and 6)-Chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (CM-H2DCFDA) and rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin were from Invitrogen. Plasmids encoding dominant-negative human β-arrestin-2 and dynamin-1 (K44A) were a gift from Dr. Ming Zhao (La Jolla Institute for Molecular Medicine, San Diego, CA) (19). A dominant-negative plasmid of human p38α MAPK was a gift from Dr. Haian Fu (Department of Pharmacology, Emory University School of Medicine). A plasmid encoding human β2-AR with a FLAG tag was a gift from Dr. Kenneth P. Minneman (Department of Pharmacology, Emory University School of Medicine). Several dominant negative expression plasmids cloned into pcDNA3.1, including Rac1 T17N 3×HA, RhoA T19N 3× HA, and Cdc42 T17N 3× HA were purchased from Missouri S&T cDNA Resource Center (Rolla, MO).

Cell Culture and Transfection—HEK293A cells were grown in high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Hyclone, Logan, UT) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Biochrom AG, Berlin, Germany), 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 100 units/ml penicillin at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Intracellular cAMP Assay—Intercellular cAMP levels were determined as previously described (20), using a commercial Parameter™ Cyclic AMP immunoassay kit (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). In brief, prior to stimulation with isoproterenol, cells were preincubated with 0.5 mm isobutylmethylxanthine for 20 min, and then lysed in 100 μl of the lysis buffer kit and freeze/thawed three times. The suspension was then centrifuged at 600 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the protein concentration of the supernatant measured using a BCA assay (Pierce). cAMP levels in the supernatant were immediately determined according to the manufacturer's protocol. The intra-assay and inter-assay coefficient of variance were 12.4 and 9.7%, respectively.

PKA Activities Assay—PKA activity was determined using a non-radioactive PKA kinase activity assay kit (Assay Designs, MI). The assay utilizes a specific synthetic peptide as a substrate for PKA, which is readily phosphorylated by PKA. Cells seeded onto 60-mm dishes were lysed in 200 μl of lysis buffer (20 mm MOPS, 50 mm β-glycerolphosphate, 50 mm sodium fluoride, 1 mm sodium vanadate, 5 mm EGTA, 2 mm EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 1 mm benzamidine, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 10 μg/ml leupeptin and aprotinin), and then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was stored at –70 °C until required. The assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the samples are added to the appropriate duplicated wells, followed by the addition of ATP to initiate the reaction. The kinase reaction is terminated and a specific phosphor-substrate antibody added to the wells. Following the addition of a peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, color development was initiated by the addition of a tetramethylbenzidine substrate. The color development was stopped with an acid stop solution and the intensity of the color measured in a microplate reader at 450 nm; color development being proportional to PKA phosphotransferase activity. The results are expressed as relative kinase activity (OD/mg·protein). The intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variance were 5.4 and 4.7%, respectively.

RNA Interference—Chemically synthesized, double-stranded siRNAs, with 19-nucleotide duplex RNA and 2-nucleotide 3′-deoxyterminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase overhangs were from Shanghai GeneChem (Shanghai, China). The siRNA sequences targeting human β-arrestin-1 and -2 were 5′-AGCCUUCUGCGCGGAGAAUtt-3′ and 5′-GGACCGCAAAGUGUUUGUGtt-3′, respectively. The previously validated siRNA sequences targeting GRKs included: GRK2 (5′-AAGAAGUACGAGAAGCUGGAG-3′), GRK3 (5′-AAGCAAGCUGUAGAACACGUA-3′), GKR5 (5′-AAGCCGUGCAAAGAACUCUUU-3′), and GRK6 (5′-AACAGUAGGUUUGUAGUGAGC-3′) (21). The previously confirmed siRNA sequences targeting p38α and p38β are 5′-AAGAAGCTCTCCAGACCATTT-3′ and 5′-AACTGGATGCATTACAACCAA-3′, respectively (22). siRNA for human GAPDH was used as a positive control (5′-GUGGAUAUUGUUGCCAUCAtt-3′). A non-silencing scramble RNA duplex was used as a negative control (5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUtt-3′). Additionally, to knock down the expression of human p47phox in a complementary experiment, p47phox siRNA duplex (sc-29422) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. For siRNA experiments, early passage HEK293A cells at 40–50% confluence on 35-mm plates were transfected with siRNA by use of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's protocol. After 48 to 72 h of transfection, cells were treated with isoproterenol for the appropriate times and harvested. The inhibitory efficiency of these siRNA probes was assessed by measuring knockdown of their respective proteins by Western blot analysis.

Western Blot Analysis—Protein expression was analyzed by Western blot as previously described (23). Briefly, samples were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking, blots were probed with the appropriate primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C or for 2 h at room temperature, then washed and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. Bands were visualized by use of a super-Western sensitivity chemiluminescence detection system (Pierce). Autoradiographs were quantitated by densitometry (Science Imaging System, Bio-Rad).

Analysis of in Vitro p38 MAPK Kinase Activity—p38 MAPK kinase activity was determined using a non-radioactive p38 kinase assay kit (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA). Briefly, cells were lysed in the kit lysis buffer containing 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Cell lysates (600 μg of protein) were immunoprecipitated with an immobilized phosphor-p38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182) monoclonal antibody, and then centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 30 s. The immunocomplexes were washed (2 times with lysis buffer and 3 times with the kit kinase buffer), centrifuged, and suspended in 50 μl of the kinase buffer. Following addition of ATP (200 μm) and the phosphor-p38 MAPK substrate (ATF-2 fusion protein, 1 μg), samples were incubated at 30 °C for 30 min, and the reaction terminated by addition of 25 μl of 3× SDS sample buffer. Samples were then boiled, centrifuged, and separated by 10% SDS-PAGE. Phosphorylated ATF-2 was detected by immunoblotting with a phospho-ATF-2 (Thr76) antibody.

Rap1 and Rac1 Activity Pulldown Assay—As previously reported (13), Rap1 activation was determined using a commercially available kit (Millipore-Upstate). Rac1 activation was measured using a Stressgen StressXpress® Rac1 activation kit (Assay Designs, MI), according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, following cell lysis, 600 μg of total protein was incubated with 20 μg of glutathione S-transferase-Pak-PBD in the spin cup containing an immobilized glutathione disc for 1 h at 4 °C with gentle rocking. Bound proteins were washed, mixed with 2× SDS sample buffer, boiled, and centrifuged at 7200 × g for 2 min. Pulled down active or GTP-Rac1 was separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with a Rac1 monoclonal antibody.

Flow Cytometric Analysis of ROS—Serum-starved cells were loaded with 10 μm CM-H2DCFDA in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium without phenol red in the dark for 30 min at 37 °C. Cells were then washed gently with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium and incubated in the presence of isoproterenol. CM-H2DCFDA is a cell permeant indicator for ROS, which is non-fluorescent until oxidization by intracellular oxidation. Treated cells were washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), then detached by trypsinization and pelleted by centrifugation (800 × g for 5 min) at 4 °C. Cell pellets were resuspended in 0.6 ml of ice-cold PBS and cellular fluorescence intensity immediately measured using a flow cytometer (BD FACS Calibur, CA) equipped with a laser lamp (emission 480 nm; band pass filter 530 nm). Data were normalized to values obtained from mock-treated controls. Approximately 10,000 cells were analyzed for each sample.

Fluorescence Microscopy—To assess F-actin rearrangement induced by isoproterenol, cells grown on glass coverslips were cultured without serum for 6 h. Following exposure to the appropriate inhibitors and isoproterenol, cells were washed, fixed, and permeabilized with 4% formaldehyde and 0.5% Triton X-100. Following washing with PBS, F-actin was stained with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin (1.0 μg/ml) for 45 min at room temperature, washed, mounted on slides with 90% glycerol in PBS, and visualized by fluorescence microscopy (×200). To provide a valid comparison, identical acquisition parameters were used for all observations. Images were randomly acquired from 10 different fields per dish or coverslip.

Confocal Imaging—To monitor intracellular distribution of phosphorylated p38 MAPK, cells were seeded on glass coverslips. The serum-starved treated cells were washed, fixed, and permeabilized as above. Following washing with PBS, cells were blocked with 10% normal goat serum, and then incubated with primary antibodies overnight, and a TRITC-conjugated secondary antibody (1:100) for 2 h at room temperature. Nuclei were stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (50 ng/ml) in PBS for 15 min. Coverslips were washed, mounted with 90% glycerol, and viewed on a confocal laser scanning microscope (TCS SP2; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) with a ×40 oil immersion objective lens.

Statistics—Values are expressed as mean ± S.E. One-way analysis of variance or Student's t test was used for statistical analysis as appropriate. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

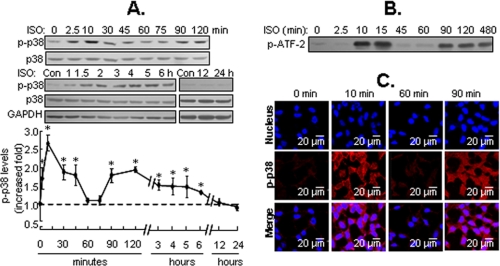

Biphasic Activation of p38 MAPK in Response to Isoproterenol Stimulation—To elucidate the mechanism of p38 MAPK activation by β2-ARs, HEK293A cells were incubated with 1 μm isoproterenol (β-adrenergic receptor agonist) for 2.5 min to 24 h. Phosphorylated p38 MAPK was determined by Western blot analysis with a specific antibody against p38 MAPK phosphorylated at residues Thr180/Tyr182. Isoproterenol caused a rapid increase in p38 MAPK phosphorylation, which was detected as early as 2.5 min and peaked at 10 min (i.e. early activation) before returning to basal level by 60 min. Surprisingly, isoproterenol also caused a secondary increase in phosphorylation of p38 MAPK after 90 min (i.e. delayed activation), which lasted for at least 6 h (Fig. 1A). Stripping and reprobing the blots with antibody against p38 MAPK demonstrated that equal amounts of p38 MAPK were detectable before and after isoproterenol treatment. In vitro kinase analysis indicated that the kinetics of p38 MAPK activity paralleled changes in its phosphorylation (Fig. 1B). In addition, intracellular immunofluorescence staining with specific phosphor-p38 MAPK antibodies and confocal imaging also illustrated the biphasic activation of p38 MAPK. Interestingly, during the early phase of the response, activated p38 MAPK was localized to the cytoplasm and plasma membrane, whereas during the delayed phase it was uniformly distributed within the cytoplasm and nucleus (Fig. 1C). The difference in distribution of activated p38 MAPK at distinct phases suggests the existence of different physiological end points.

FIGURE 1.

β2-ARs stimulation induces biphasic activation of p38 MAPK. A, HEK293A cells were stimulated with isoproterenol (ISO; 1 μm) for the indicated times. The phosphorylation of p38 MAPK (p-p38) was detected by Western blot analysis. GAPDH was also included as a loading control. Results are expressed as the increased -fold over the control (Con) or zero time point and are mean ± S.E. of 3 to 10 independent experiments, *, p < 0.05. B, ISO-induced p38 MAPK kinase activities at the indicated times were determined by in vitro kinase analysis, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A representative Western blot for each treatment from three independent experiments is shown. C, the cells were treated with ISO for the indicated times. The intracellular distribution of phosphorylated p38 MAPK (p-p38) was detected by immunofluorescence staining and confocal imaging. Representative fields from three independent experiments are shown.

Furthermore, isoproterenol dose dependently increased phosphorylation of p38 MAPK during both phases of the response, with EC50 of 1.094 and 4.405 nm for early and delayed activation, respectively (supplemental data Fig. S1, A and B). Previous studies indicate that β2- but not β1-ARs are endogenously expressed in HEK293 cells. As expected, cells pretreated for 30 min with either propranolol, a non-selective β-AR antagonist, or ICI 118551, a selective β2-AR antagonist, reduced both early and delayed p38 MAPK activation (supplemental data Fig. S2). Therefore, the stimulation of endogenous β2-ARs is sufficient to evoke biphasic activation of p38 MAPK in a time- and dose-dependent fashion. It is noted that the similar pattern of p38 MAPK phosphorylation was also obtained in cells with transient overexpression of β2-ARs (data not shown). Compared with those mock-transfected cells, isoproterenol stimulation readily evoked the biphasic phosphorylation of p38 MAPK, as evidenced by the overall p38 MAPK phosphorylation that was increased by 2.5-fold at 10 min and 3.2-fold at 90 min (supplemental data Fig. S3, A and B).

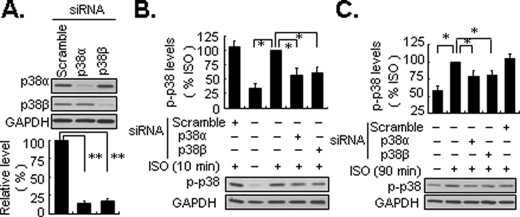

Both p38α and p38β Are Implicated in the Biphasic Activation of p38 MAPK by β2-ARs—The mammalian p38 MAPK subfamily includes four known isoforms: p38α, p38β, p38γ, and p38δ. p38α and p38β are ubiquitously expressed, whereas p38γ and p38δ appear to have more restricted tissue-specific expression (2, 3). To elucidate which p38 isoform(s) is involved in the biphasic activation of p38 MAPK in response to isoproterenol, we focused on p38α and p38β MAPK. In cells transfected with a dominant negative mutant of p38α MAPK, both the early and delayed activation of p38 MAPK by isoproterenol was partially attenuated (supplemental data Fig. S4). In addition, in cells transfected with siRNA directed toward p38α, p38β MAPK, or scramble control there was selective knockdown of their endogenously expressed target protein compared with scramble control (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, silencing either p38α or p38β MAPK inhibited the early and delayed activation of MAPK (Fig. 2, B and C). Collectively, these results suggest that p38α and p38β MAPK are both implicated in the biphasic activation of p38 MAPK following stimulation with isoproterenol in HEK293 cells.

FIGURE 2.

Both p38α andβ subtypes are implicated in biphasic activation of p38 MAPK by β2-ARs. Cells were transfected with 100 nm specific siRNA against p38α,β MAPK, and scramble control, respectively. Seventy-two hours later, the cells were treated with isoproterenol (ISO; 1 μm) for 10 or 90 min. The levels of endogenous expression of p38α and β MAPK (A) and p38 MAPK phosphorylation (p-p38)(B and C) were detected by Western blot analysis. GAPDH was also included as a loading control. Results are represented by mean ± S.E. (n = 3); *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

Effects of the cAMP/PKA Signaling Pathway in the Biphasic Activation of p38 MAPK—β2-ARs classically couple to Gs proteins to initiate signaling via a cAMP/PKA pathway. To determine the involvement of the cAMP/PKA pathway in the biphasic activation of p38 MAPK by β2-ARs, cells were pretreated with a potent adenyl cyclase inhibitor. To our surprise, even though 100 μm SQ22536 inhibited the isoproterenol-induced increase in cAMP as determined by a competitive nonradioactive enzyme-linked assay (supplemental data Fig. S5), it did not affect the early activation of p38 MAPK. However, it did inhibit phosphorylation of p38 MAPK during the delayed phase (Fig. 3A). PKA is the primary downstream target for cAMP. As in previous studies (12, 24), isoproterenol-induced PKA activation and ensuing ERK1/2 phosphorylation were inhibited by selective inhibitors, including (Rp)-cAMP (10 μm), H89 (10 μm), and KT5720 (0.3 μm) (supplemental data Fig. S6, A and B). Interestingly, in cells preincubated for 30 min with 10 μm (Rp)-cAMP, the early activation of p38 MAPK was unaffected. However, delayed activation of p38 MAPK was completely abolished (Fig. 3B). Similar results were also obtained from cells pretreated with H89 or KT5720 (Fig. 3, C and D). Together, these results indicate that the Gs/cAMP/PKA pathway is only responsible for the delayed activation of p38 MAPK by β2-ARs.

FIGURE 3.

The effects of the cAMP/PKA pathway onβ2-AR-mediated biphasic activation of p38 MAPK. Cells were pretreated with the adenyl cyclase inhibitor SQ22536 (SQ, 100 μm) for 30 min, and then were exposed to isoproterenol (ISO; 1 μm) for 10 (left panel) or 90 (right panel) min (A). Cells were preincubated with specific PKA antagonist (Rp)-cAMP (10μm) for 30 min, and then treated with ISO for 5 to 120 min (B). Cells were preincubated with the specific PKA antagonist H89 (10 μm), or KT 5720 (KT, 0.3 μm) for 30 min, and then stimulated with ISO (1 μm) for 10 (C) or 90 min (D). The levels of p38 MAPK phosphorylation (p-p38) were determined by Western blot analysis. All results are represented by mean ± S.E. (n = 3), *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; n.s., no significance.

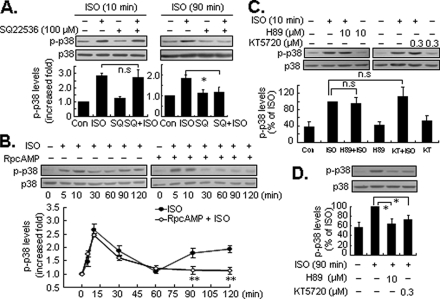

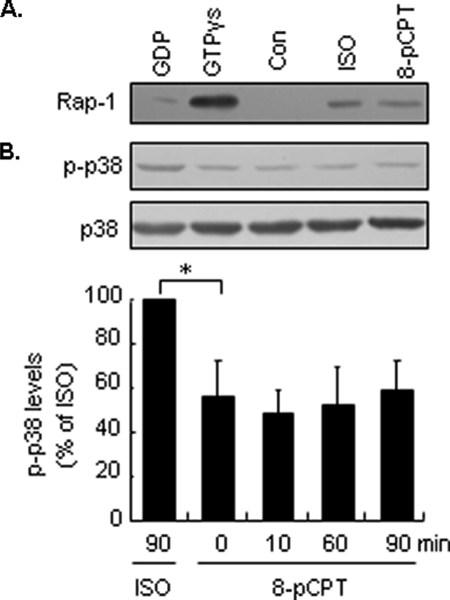

cAMP/Epac Signaling Is Not Involved in Isoproterenol-induced p38 MAPK Activation—In addition to PKA, cAMP can also active the Epac/Rap1 pathway and has been implicated in β2-AR-induced activation of several effectors including protein kinase Cε in dorsal root ganglion neurons (25) and ERK1/2 in HEK293 cells (26). Activation of Epac by specific cAMP analog 8-pCPT-2Me-cAMP (8-pCPT) can activate p38 MAPK in cultured cerebellar granule cells (27). In this study, 8-pCPT, as a direct activator of Epac, and ISO activated Rap1 as determined using pulldown assays (Fig. 4A), 8-pCPT did not elicit p38 MAPK phosphorylation during the first 90 min of exposure (Fig. 4B). Therefore, these results suggest that β2-AR-mediated biphasic activation of p38 MAPK involves different signaling mechanisms. The classical cAMP/PKA pathway, but not cAMP/Epac, is essential for the delayed rather than early activation of p38 MAPK.

FIGURE 4.

cAMP/Epac pathway is not responsible for isoproterenol (ISO)-induced p38 MAPK activation. A, cells were stimulated with ISO (1 μm) or Epac agonist 8-pCPT-2Me-cAMP (8-pCPT; 100 μm) for 10 min, and the activation of Rap1 was determined by pulldown assays. GTPγs or GDP in vitro loading acted as positive and negative controls, respectively. A representative Western blot for each treatment from three independent experiments is shown. B, cells were stimulated with ISO or 8-pCPT for the indicated times. The levels of p38 MAPK phosphorylation (p-p38) were determined by Western blot analysis. Results are represented by mean ± S.E. (n = 3), *, p < 0.05.

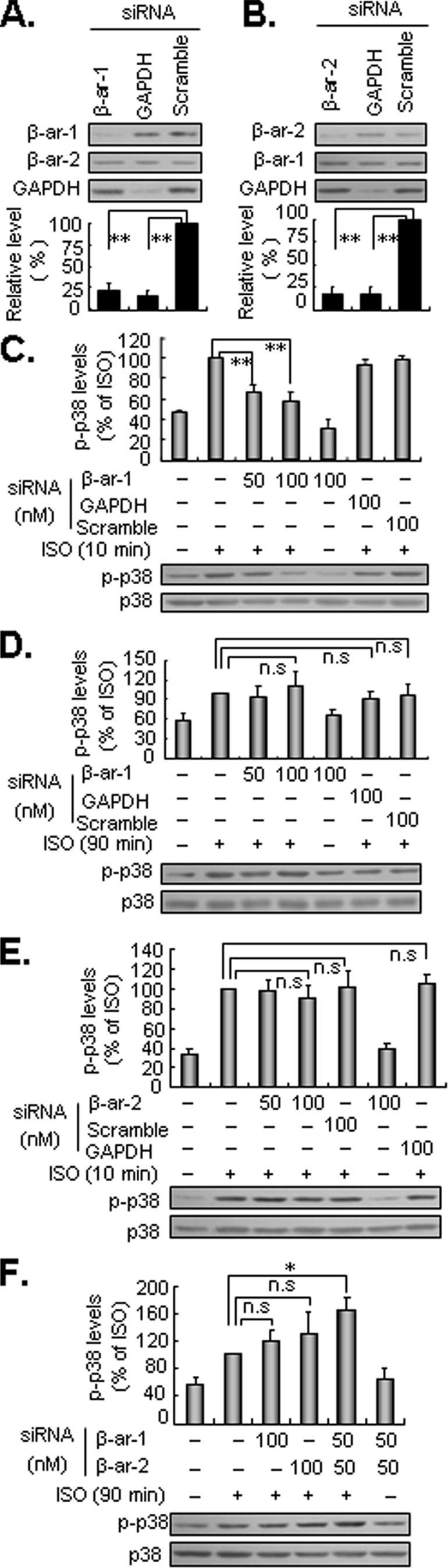

β-Arrestin-1 Mediates Isoproterenol-induced Early Activation of p38 MAPK—Recent studies demonstrate that β-arrestin-1/2 can function as scaffolding proteins that coordinate the interaction of various signaling molecules following activation of GPCRs and subsequently initiate signal transduction within cells (14, 15, 24, 28). To determine the potential role of β-arrestin-1/2 in β2-AR-mediated activation of p38 MAPK, HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with β-arrestin-1/2 siRNA, control scramble siRNA, or GAPDH siRNA (100 nm). Two days later, cells were treated with isoproterenol for either 10 or 90 min. Western blot analysis revealed that β-arrestin-1/2 and GAPDH siRNA but not control scramble siRNA effectively attenuated the endogenous protein expression of their targets (Fig. 5, A and B). Interestingly, silencing of β-arrestin-1 significantly inhibited the early activation of p38 MAPK, by 78% (Fig. 5C), without affecting the delayed activation phase (Fig. 5D). In contrast, inhibiting β-arrestin-2 expression did not affect early phase activation (Fig. 5E) but had a slight augmented effect on the delayed activation of p38 MAPK (Fig. 5F). Similar results were obtained in cells transiently expressing a dominant-negative mutant of β-arrestin-2 (data not shown). Interestingly, the combination of β-arrestin-1 and -2 knockdown moderately enhanced the delayed phosphorylation of p38 MAPK following isoproterenol challenge (Fig. 5F). Thus, β-arrestin-1 but not β-arrestin-2 may be responsible for β2-AR-mediated early activation of p38 MAPK.

FIGURE 5.

β-Arrestin-1 but not β-arrestin-2 mediates the early activation of p38 MAPK induced by β2-ARs. Cells were transfected with 100 nm siRNA of β-arrestin-1 (β-ar-1; A), β-arrestin-2 (β-ar-2; B), GAPDH (as a positive control), and scramble siRNA, respectively. Forty-eight hours later, the expression levels of β-arrestin-1/2 and GAPDH were determined by Western blot analysis. Cells transfected with siRNA of GAPDH, scramble, β-AR-1 (C and D), β-AR-2 (E), and a combination of β-AR-1 and -2 (F) for the indicated doses were stimulated with 1 μm isoproterenol (ISO; 1 μm) for 10 or 90 min. The levels of p38 MAPK phosphorylation (p-p38) were determined by Western blot analysis. Results are represented by mean ± S.E. (n = 3), *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; n.s., no significance.

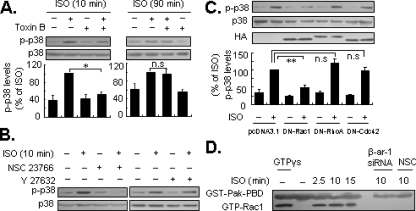

Activation of Rac1 Is Essential for β-Arrestin-1-mediated Early Activation of p38 MAPK by β2-ARs—Growing evidence indicates that β-arrestins can facilitate signaling events involving small GTPases such as Rho (14, 29, 30). Furthermore, several members of the Rho family including RhoA, Rac1, and Cdc42 have been reported to regulate the activity of p38 MAPK (31–33). Based upon these observations, we investigated whether members of the Rho family are involved in β-arrestin-1-dependent p38 MAPK activation. Cells were pretreated with a broad-spectrum Rho family inhibitor, C. difficile Toxin B (50 to 500 pg/ml) for 24 h. Application of 100 pg/ml Toxin B inhibited isoproterenol-induced early activation of p38 MAPK, with little effect on delayed phosphorylation (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, NSC23766 (100 μm) a potent Rac1 inhibitor, also completely inhibited early activation of p38 MAPK (Fig. 6B). The specificity of this inhibitor for Rac1 has been established previously (34). As a control, the Rho kinase inhibitor Y27632 had little effect p38 MAPK activation (Fig. 6B). To support this finding, cells were transfected with plasmids encoding the HA tag dominant negative mutants of RhoA (T19N), Rac1 (T17N), and Cdc42 (T17N). Overexpression of these dominant negative mutants were confirmed 72 h post-transfection by immunoblotting cell lysates with HA specific antibody (Fig. 6C). Consistent with the data from experiments with NSC23766, expression of the dominant negative mutant of Rac1, but not RhoA nor Cdc42, significantly decreased activation of p38 MAPK following exposure to isoproterenol stimulation for 10 min (Fig. 6C), indicating that Rac1 has a role in the early activation of p38 MAPK. In addition, we observed that isoproterenol increased levels of the GTP-bound form of Rac1 in pulldown assays (Fig. 6D). Of note, Rac1 activation was completely abrogated by the application of NSC23766 and β-arrestin-1 siRNA (Fig. 6D). Collectively, these data suggest that Rac1 acts as a downstream target of β-arrestin-1 in isoproterenol-induced early activation of p38 MAPK.

FIGURE 6.

Rac1 acts as a downstream target of β-arrestin-1. A, cells were preincubated with C. difficile Toxin B (Toxin B; 100 pg/ml), an inhibitor of Rho family, for 24 h, and then treated with isoproterenol (ISO; 1 μm) for 10 (left panel) or 90 (right panel) min. B, similarly, cells were preincubated with the specific Rac1 inhibitor NSC23766 (100 μm) for 24 h or Rho kinase inhibitor Y27632 (10 μm) for 30 min, then the cells were treated with ISO for 10 min. C, cells were transfected with dominant negative expression plasmids of Rac1 (DN-Rac1), RhoA (DN-RhoA), Cdc42 (DN-Cdc42), or empty vector (pcDNA3.1), respectively. After 72 h of transfection, the cells were treated with ISO for 10 min. The levels of p38 MAPK phosphorylation (p-p38) were determined by Western blot analysis. Results are represented by mean ± S.E. (n = 3), *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; n.s., no significance. D, cells were transfected with β-arrestin-1 siRNA (β-ar-1 siRNA) for 48 h or pretreated with 100 μm NSC23766 (NSC) alone for 24 h, and then treated with ISO for the indicated timeS. The Rac1 activation (i.e. GTP-bound Rac1, GTP-Rac1) was detected by pulldown assays. A representative Western blot for each treatment from three independent experiments is shown.

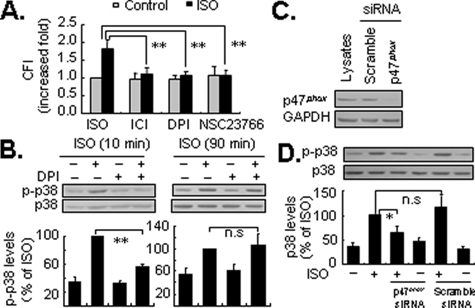

NADPH Oxidase and Rac1 Cooperatively Regulate Isoproterenol-induced Early Activation of p38 MAPK—NADPH oxidase consists of two membrane-associated catalytic subunits (NOX and p22phox) and three cytoplasmic regulatory subunits p47phox, p67phox, and p40phox (35, 36). Accumulating evidence demonstrates that activation of Rac1 facilitates the formation of the active NADPH oxidase complex, which plays a central role in the generation of ROS in some non-phagocytic cells such as cardiac myocytes and endothelial cells (35). As endogenous and exogenous ROS are potent stimuli for p38 MAPK activation (37, 38), we addressed whether NADPH oxidase was also involved in the β-arrestin-1-dependent early activation of p38 MAPK via ROS. As shown in Fig. 7A, application of either 10 μm DPI, a potent inhibitor of NADPH oxidase (39), or 100 μm NSC23766 effectively inhibited isoproterenol-induced ROS generation. As expected, DPI significantly attenuated isoproterenol-induced early activation of p38 MAPK by ∼80%. By contrast, there was no detectable alteration in delayed p38 MAPK activation (Fig. 7B). Comparable data were obtained using apocynin (40), at 1 μm, which is a specific inhibitor of NADPH oxidase (supplemental data Fig. S7). As p47phox is required for the assembly of a functional NADPH oxidase complex (36), we assessed the effect of p47phox knockdown by the application of siRNA (Fig. 7C), as previously reported (41). Consistent with data from pharmacological experiments, silencing p47phox also markedly decreased the early activation of p38 MAPK following isoproterenol stimulation (Fig. 7D). As a control rotenone, an inhibitor of mitochondrial electron transport complex I and mitochondrial ROS generation (42), had no effect on p38 MAPK activation (data not shown). Therefore, the NADPH oxidase complex may mediate β-arrestin-1-dependent activation of p38 MAPK.

FIGURE 7.

Inhibition of NADPH oxidase attenuates the early activation of p38 MAPK by β2-ARs. Cells preincubated with the selective β2-AR antagonist ICI 118551 (ICI; 0.1 μm; 30 min), NADPH oxidase inhibitor DPI (10 μm, 30 min), or Rac1 inhibitor NSC 23766 (NSC; 100 μm; 24 h) were stained with CM-H2DCFDA (10 μm) for 30 min, then treated with isoproterenol (ISO; 1 μm) for 5 min. Intracellular ROS levels were measured by flow cytometric analysis, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Results were expressed as the increased -fold of cellular fluorescence intensity (CFI) over the basal value obtained in the absence of ISO, and are represented by mean ± S.E. (n = 3). **, p < 0.01 (A). Cells were pretreated with DPI (10 μm, 30 min), and then stimulated with ISO (1 μm) for 10 (left panel) or 90 (right panel) min. The levels of p38 MAPK phosphorylation (p-p38) were determined by Western blot analysis. Results are represented by mean ± S.E. (n = 3), **, p < 0.01; n.s., no significance (B). Cells were transfected with 40 nm p47phox siRNA or scramble siRNA. After 48 h of transfection, the level of endogenous GAPDH (as a loading control), p47phox expression (C), and ISO-induced p38 MAPK phosphorylation at 10 min (D) were determined by Western blot assays with appropriate antibodies. The results were represented by mean ± S.E. (n = 3), *, p < 0.05; n.s., no significance.

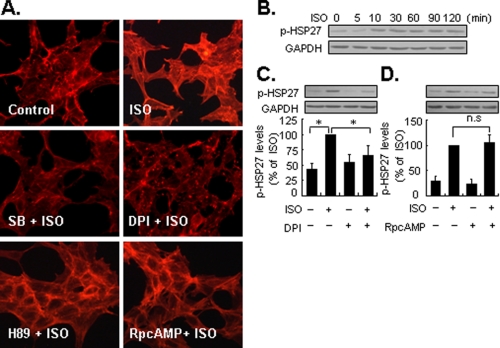

Isoproterenol-induced F-actin Rearrangement Is Dependent on Early Activation of p38 MAPK—In this study we preliminarily assessed the functional relevance of the biphasic activation of p38 MAPK by β2-ARs. Cytoskeleton plays a pivotal role in intracellular trafficking, cellular apoptosis, proliferation and differentiation, cell movement, and defines the cell phenotype. In response to extracellular stimuli, Rac1 and activated p38 MAPK are known to cause actin polymerization and formation of stress fibers through the phosphorylation of HSP27 (43–45). Therefore, we studied the effects of biphasic activation of p38 MAPK by isoproterenol on actin reorganization. Staining of F-actin with rhodamine-labeled phalloidin showed tangled, punctate structures in untreated cells (Fig. 8A). However, following exposure to isoproterenol, there was a marked increase in formation of F-actin clusters. This was accompanied by phosphorylation of HSP27 at Ser82, which lasted at least 2 h (Fig. 8B). The former was inhibited by SB202190, a specific p38α/β MAPK inhibitor (Fig. 8A). Intriguingly, whereas DPI inhibited the early activation of p38 MAPK, it also attenuated phosphorylation of HSP27 (Fig. 8C) and F-actin rearrangement. By contrast, (Rp)-cAMP and H89 did not influence isoproterenol-induced phosphorylation of HSP27 nor F-actin rearrangement (Fig. 8, A and D). Together, these data indicate that isoproterenol induced early activation of p38 MAPK is involved in F-actin rearrangement by eliciting HSP27 phosphorylation.

FIGURE 8.

The early activation of p38 MAPK by β2-ARs regulates F-actin rearrangement. A, top panel, untreated cells (control) and cells stimulated with ISO (1 μm) for 10 min. Middle panel, cells were pretreated with SB202190 (10 μm) or DPI (10 μm) for 30 min, then stimulated with ISO for 10 min. Bottom panel, cells were pretreated with H89 (10 μm) or (Rp)-cAMP (10 μm) for 30 min, then stimulated with ISO for 10 min. F-actin was viewed by rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin staining, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Representative fields from three independent experiments are shown. B, cells were treated with ISO (1 μm) for 0 to 120 min. C, cells were preincubated with DPI (10 μm) for 30 min, and then treated with ISO for 10 min. D, cells were preincubated with (Rp)-cAMP (10 μm) for 30 min, and then treated with ISO for 90 min. The levels of HSP27 phosphorylation (p-HSP27) were determined by Western blotting with an antibody against phosphorylated HSP27 at Ser82. GAPDH was also included as a loading control. Results are represented by mean ± S.E. (n = 3), *, p < 0.05; n.s., no significance. A representative Western blot for each treatment from three independent experiments is shown.

DISCUSSION

Upon agonist binding, β-arrestins1/2 is recruited to the plasma membrane and mediates desensitization and internalization of GPCRs (14). Recently, β-arrestin-1/2 has emerged as novel non-G protein-dependent signaling molecules, raising considerable interest in their role as biological response modulators of GPCRs (including β-ARs) (24, 46, 47). For example, β-arrestin-2-dependent activation of ERK1/2 following angiotensin II stimulation mainly occurs in cytoplasmic vesicular structures that contain the internalized receptor (15). More recently, β-arrestin-dependent transactivation of epidermal growth factor receptor has been found to promote activation of the cardioprotective pathway that counteracts the effects of catecholamine toxicity (48). In the present study we used RNA interference against β-arrestin-1/2 to test its role in p38 MAPK signal transduction. The specificity and efficiency of siRNA against β-arrestin-1/2 was demonstrated by Western blot analysis (Fig. 5, A and B). Previous studies indicate that for several GPCRs, such as κ-opioid receptor and human cytomegalovirus US28 (47, 49), β-arrestin-2 is involved in p38 MAPK activation. Our study indicates that depletion of cellular β-arrestin-1, but not β-arrestin-2, greatly attenuated early activation but not delayed activation of p38 MAPK, suggesting that β-arrestin-1 is required for the early activation of p38 MAPK. Similarly, in human polymorphonuclear neutrophils, β-arrestin-1, MKK3, and p38 MAPK are involved in the formation of a multicomponent signalosome, which plays a role in actin bundle formation following exposure to platelet aggregating factor (50). Interestingly, concomitant β-arrestin-1 and -2 siRNA enhance delayed activation of p38 MAPK. Based on the known role of β-arrestin-1 and -2 in desensitization of β2-ARs, we considered that attenuation of internalization and desensitization due to the down-regulation of β-arrestin-1 and -2 expressions by siRNA enhances the delayed phase activation of p38 MAPK. A great deal of evidence shows that dynamin is involved in clathrin-coated vesicle-mediated internalization and trafficking of β2-ARs (51). In cells transfected with a dominant negative mutant of dynamin 1 (K44A), although early activation of p38 MAPK was unaffected, there was a modest increase in the delayed phosphorylation of p38 MAPK (supplemental data Fig. S8). Taken together, these data suggest that β-arrestin-1 but not β-arrestin-2 plays a determinant role in the early activation of p38 MAPK by β2-ARs. However, it remains unclear how β-arrestin-1 modulates p38 MAPK activation in response to β2-ARs stimulation. Recent data show that activation of GRKs following agonist binding is critical for receptor phosphorylation and recruitment of β-arrestins (28). Of the seven GRKs family members, GRK1, -4, and -7 undergo tissue-specific expression, whereas GRK2, -3, -5, and -6 are ubiquitously expressed (14, 21). In our complementary experiments, we observed that endogenous expression of GRKs could be specifically knocked down using validated siRNA probes (21). Interestingly, silencing GRK2, -3, -5, or -6 modestly inhibit the early activation of p38 MAPK (supplemental data Fig. S9, A and B), suggesting a role of GRKs in the regulation of β2-AR-mediated p38 MAPK activation.

Rho GTPases belong to the large superfamily of Ras proteins, which are monomeric GTP-binding proteins that exist in either an inactive GDP-bound state or an active GTP-bound form. Rho, Rac, and Cdc42 are the most thoroughly studied Rho GTPases. It is established that the activated Rho GTPases act as upstream regulators of the p38 MAPK pathway in response to various stimuli such as interleukin-1, arsenic trioxide, and ligands of prototypical Gi-coupled receptors (i.e. M2 muscarinic, A1 adenosine) in COS, HeLa, and H10 cells (31, 32, 52). In the present study, we provide evidence based upon knockdown experiments that Rac1 is a downstream target of β-arrestin-1 involved in isoproterenol-induced p38 MAPK early activation. Furthermore, inhibition of Rac1 by either pharmacologic inhibitors or overexpression of its dominant negative mutant also block the early activation of p38 MAPK by β2-ARs.

Apart from the essential role in actin cytoskeleton rearrangement, activated Rac1 is also important in the formation of the NADPH oxidase complex through association with membrane-bound NADPH oxidase (53). Activated NADPH oxidase has been shown to be a primary resource of intracellular ROS generation in non-phagocytic cells (35, 54). Because ROS activate p38 MAPK in response to various stimuli through inactivation of protein phosphatases or enhancement of upstream kinase activity such as signaling regulating kinase 1 (55, 56), we postulated that NADPH oxidase complex-mediated intracellular ROS generation might contribute to β-arrestin-1-dependent p38 MAPK activation by β2-ARs. In a recent report (57), isoproterenol induces intracellular ROS generation within several minutes through activation of the NADPH oxidase complex, an effect that could be blocked by pharmacological inhibition of Rac1 and NADPH oxidase. As expected, inhibition of NADPH oxidase by chemical inhibitors, or through silencing of its subunit p47phox with siRNA, resulted in significant attenuation of the early but not delayed activation of p38 MAPK. In support of this others have shown that in Chinese hamster ovary cells stably expressing human thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and forskolin-induce p38 MAPK activation also depended fully on the activation of PKA and Rac1, as well as ensuing ROS generation (37).

It is generally accepted that MAPK kinase 3/6 (MKK3/6) and MKK4 are upstream kinases involved in p38 MAPK activation. However, the adaptor molecule, transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase 1-binding protein 1 (TAB1)-induced autophosphorylation of p38 MAPK can act as an alternative, kinase-independent mechanism leading to p38 MAPK activation (58). Therefore, the role of kinase-dependent and kinase-independent mechanisms in controlling p38 MAPK activation by β2-ARs should be addressed in future studies.

In conclusion, we provide evidence that β2-ARs stimulation can evoke a biphasic activation of p38 MAPK through 2 distinct signaling pathways. The β-arrestin-1/Rac1/NADPH oxidase pathway is responsible for early activation, whereas a cAMP/PKA cascade is involved in the delayed activation. These findings have implications not only with regard to our understanding of the versatility of p38 MAPK in mediating β2-AR-associated biologic effects, but also for the development of therapeutic agents targeting these pathways.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We greatly thank Dr. James Paul Spiers for excellent revision on the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Key Basic Research Program of the People's Republic of China Grant G2006CB503806 and Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 30672466 and 30570716. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S9.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; β2-AR, β2-adrenergic receptor; PKA, protein kinase A; GPCR, G protein-coupled receptor; ROS, reactive oxygen species; Epac, exchange protein directly activated by cAMP; ERK1/2, extracellular signal-regulated kinases; GRKs, G-protein-coupled receptor kinases; siRNA, small interfering RNA; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase; 8-pCPT-2Me-cAMP, 8-(4-chlorophenylthio)-2′-O-methyl cyclic AMP; DPI, diphenyleneiodonium chloride; CM-H2DCFDA, 5-(and 6)-chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate; HA, hemagglutinin; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; HEK, human embryonic kidney; TRITC, tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate; MOPS, 4-morpholinepropanesulfonic acid; GTPγS, guanosine 5′-3-O-(thio)triphosphate.

References

- 1.Chi, D., Fitzgerald, S. M., Pitts, S., Cantor, K., King, E., Lee, S., Huang, S. K., and Krishnaswamy, G. (2004) BMC Immunol. 5 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashwell, J. D. (2006) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6 532–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang, Y. (2007) Circulation 116 1413–1423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Magne, S., Couchie, D., Pecker, F., and Pavoine, C. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 39539–39548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peter, P. S., Brady, J. E., Yan, L., Chen, W., Engelhardt, S., Wang, Y., Sadoshima, J., Vatner, S. F., and Vatner, D. E. (2007) J. Clin. Investig. 117 1335–1343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamauchi, J., Nagao, M., Kaziro, Y., and Itoh, H. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 27771–27777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delghandi, M. P., Johannessen, M., and Moens, U. (2005) Cell Signal. 17 1343–1351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng, M., Zhang, S. J., Zhu, W. Z., Ziman, B., Kobilka, B. K., and Xiao, R. P. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 40635–40640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng, M., Zhu, W., Han, Q., and Xiao, R. P. (2005) Pharmacol. Ther. 108 257–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishihara, H., Hwang, M., Kizaka-Kondoh, S., Eckmann, L., and Insel, P. A. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 26176–26183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerlo, S., Verdood, P., Hooghe-Peters, E., and Kooijman, R. (2006) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 63 92–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan, K. S., Nackley, A. G., Satterfield, K., Maixner, W., Diatchenko, L., and Flood, P. M. (2007) Cell Signal. 19 251–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yin, F., Wang, Y. Y., Du, J. H., Li, C., Lu, Z. Z., Han, C., and Zhang, Y. Y. (2006) J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 40 384–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lefkowitz, R. J., Rajagopal, K., and Whalen, E. J. (2006) Mol. Cell 24 643–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahn, S., Shenoy, S. K., Wei, H., and Lefkowitz, R. J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 35518–35525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma, L., and Pei, G. (2007) J. Cell Sci. 120 213–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tohgo, A., Choy, E. W., Gesty-Palmer, D., Pierce, K. L., Laporte, S., Oakley, R. H., Caron, M. G., Lefkowitz, R. J., and Luttrell, L. M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 6258–6267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wisler, J. W., DeWire, S. M., Whalen, E. J., Violin, J. D., Drake, M. T., Ahn, S., Shenoy, S. K., and Lefkowitz, R. J. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104 16657–16662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao, M., Wimmer, A., Trieu, K., DiScipio, R. G., and Schraufstatter, I. U. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 49259–49267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malki, S., Nef, S., Notarnicola, C., Thevenet, L., Gasca, S., Méjean, C., Berta, P., Poulat, F., and Boizet-Bonhoure, B. (2005) EMBO J. 24 1798–1809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Violin, J. D., Ren, X. R., and Lefkowitz, R. J. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 20577–20588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shiromizu, T., Goto, H., Tomono, Y., Bartek, J., Totsukawa, G., Inoko, A., Nakanishi, M., Matsumura, F., and Inagaki, M. (2006) Genes Cells 11 477–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yin, F., Li, P., Zheng, M., Chen, L., Xu, Q., Chen, K., Wang, Y., Zhang, Y., and Han, C. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 21070–21075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shenoy, S. K., Drake, M. T., Nelson, C. D., Houtz, D. A., Xiao, K., Madabushi, S., Reiter, E., Premont, R. T., Lichtarge, O., and Lefkowitz, R. J. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 1261–1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hucho, T. B., Dina, O. A., and Levine, J. D. (2005) J. Neurosci. 25 6119–6126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keiper, M., Stope, M. B., Szatkowski, D., Bohm, A., Tysack, K., vom Dorp, F., Saur, O., Oude, W. P., Evellin, S., Jakobs, K. H., and Schmidt, M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 46497–46508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ster, J., De, Bock, F., Guérineau, N. C., Janossy, A., Barrère-Lemaire, S., Bos, J. L., Bockaert, J., and Fagni, L. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104 2519–2524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reiter, E., and Lefkowitz, R. J. (2006) Trends Endocrinol. Metabol. 17 159–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhattacharya, M., Anborgh, P. H., Babwah, A. V., Dale, L. B., Dobransky, T., Benovic, J. L., Feldman, R. D., Verdi, J. M., Rylett, R. J., and Ferguson, S. S. (2002) Nat. Cell Biol. 4 547–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barnes, W. G., Reiter, E., Violin, J. D., Ren, X. R., Milligan, G., and Lefkowitz, R. J. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 8041–8050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bagrodia, S., Derijard, B., Davis, R. J., and Cerione, R. A. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270 27995–27998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verma, A., Mohindru, M., Deb, D. K., Sassano, A., Kambhampati, S., Ravandi, F., Minucci, S., Kalvakolanu, D. V., and Platanias, L. C. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 44988–44995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Semenova, M. M., Maki-Hokkonen, A. M., Cao, J., Komarovski, V., Forsberg, K. M., Koistinaho, M., Coffey, E. T., and Courtney, M. J. (2007) Nat. Neurosci. 10 436–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao, Y., Dickerson, J. B., Guo, F., Zheng, J., and Zheng, Y. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101 7618–7623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bedard, K., and Krause, K. H. (2007) Physiol. Rev. 87 245–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Babior, B. M. (1999) Blood 93 1464–1476 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pomerance, M., Abdullah, H. B., Kamerji, S., Correze, C., and Blondeau, J. P. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 40539–40546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sano, M., Fukuda, K., Sato, T., Kawaguchi, H., Suematsu, M., Matsuda, S., Koyasu, S., Matsui, H., Yamauchi-Takihara, K., Harada, M., Saito, Y., and Ogawa, S. (2001) Circ. Res. 89 661–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ellis, J. A., Mayer, S. J., and Jones, O. T. (1988) Biochem. J. 251 887–891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ximenes, V. F., Kanegae, M. P., Rissato, S. R., and Galhiane, M. S. (2007) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 457 134–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siow, Y. L., Au-Yeung, K. K., Woo, C. W., and Karmin, O. (2006) Biochem. J. 398 73–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim, J. K., Pedram, A., Razandi, M., and Levin, E. R. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 6760–6767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huot, J., Houle, F., Rousseau, S., Deschesnes, R. G., Shah, G. M., and Landry, J. (1998) J. Cell Biol. 143 1361–1373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pichon, S., Bryckaert, M., and Berrou, E. (2004) J. Cell Sci. 117 2569–2577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okada, T., Otani, H., Wu, Y., Kyoi, S., Enoki, C., Fujiwara, H., Sumida, T., Hattori, R., and Imamura, H. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. 289 H2310–H2318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hall, R. A., Premont, R. T., and Lefkowitz, R. J. (1999) J. Cell Biol. 145 927–932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bruchas, M. R., Macey, T. A., Lowe, J. D., and Chavkin, C. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 18081–18089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Noma, T., Lemaire, A., Prasad, S. V., Barki-Harrington, L., Tilley, D. G., Chen, J., Corvoisier, P. L., Violin, J. D., Wei, H., Lefkowitz, R. J., and Rockman, H. A. (2007) J. Clin. Investig. 117 2245–2258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller, W. E., Houtz, D. A., Nelson, C. D., Kolattukudy, P. E., and Lefkowitz, R. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 21663–21671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McLaughlin, N. J., Banerjee, A., Kelher, M. R., Gamboni-Robertson, F., Hamiel, C., Sheppard, F. R., Moore, E. E., and Silliman, C. C. (2006) J. Immunol. 176 7039–7050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vaughan, D. J., Millman, E. E., Godines, V., Friedman, J., Tran, T. M., Dai, W., Knoll, B. J., Clark, R. B., and Moore, R. H. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 7684–7692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vogt, A., Lutz, S., Rumenapp, U., Han, L., Jakobs, K. H., Schmidt, M., and Wieland, T. (2007) Cell Signal. 19 1229–1237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cheng, G., Diebold, B. A., Hughes, Y., and Lambeth, J. D. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 17718–17726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Droge, W. (2002) Physiol. Rev. 82 47–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cave, A. C., Brewer, A. C., Narayanapanicker, A., Ray, R., Grieve, D. J., Walker, S., and Shah, A. M. (2006) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 8 691–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ushio-Fukai, M. (2006) Sci. STKE 2006 re8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moniri, N. H., and Daaka, Y. (2007) Biochem. Pharmacol. 74 64–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ge, B., Gram, H., Di, P. F., Huang, B., New, L., Ulevitch, R. J., Luo, Y., and Han, J. (2002) Science 295 1291–1294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.