Abstract

Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) down-regulates the expression of follistatin mRNA in intestinal epithelial cells in vivo. The mechanism of PPARγ-mediated down-regulation of follistatin was investigated using non-transformed, rat intestinal epithelial cells (RIE-1). RIE cells expressed activin A, the activin receptors ActRI and ActRII, and the follistatin-315 mRNA. RIE-1 cells responded to endogenous activin A, and this response was antagonized by follistatin, as evidenced by changes in cell growth and regulation of an activin-responsive reporter. Using RIE-1 cells, we show that activation of PPARγ by rosiglitazone reduced follistatin mRNA levels in a dose- and concentration-dependent manner. Down-regulation of follistatin by rosiglitazone required the DNA binding domain of PPARγ and was dependent upon dimerization with the retinoid X receptor. Inhibition of follistatin expression by rosiglitazone was not associated with decreased follistatin mRNA stability, suggesting that regulation may be at the promoter level. Analysis of the follistatin promoter revealed consensus binding sites for AP-1, AP-2, and Sp1. Targeting the AP-1 pathway with SP600125, an inhibitor of JNK, and TAM67, a dominant negative c-Jun, had no effect on PPARγ-mediated down-regulation of follistatin. However, the follistatin promoter was dramatically regulated by Sp1, and this regulation was inhibited by PPARγ expression. Knockdown of Sp1 expression relieved repression of follistatin levels by rosiglitazone. Moreover, PPARγ was found to interact with Sp1 and repress its transcriptional activation function. Collectively, our data indicate that repression of Sp1 transcriptional activity by PPARγ is the underlying mechanism responsible for PPARγ-mediated regulation of follistatin expression.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ)2 is a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily of transcription factors, which includes glucocorticoid, estrogen, and thyroid receptors (1, 2). Two major forms of PPARγ, γ1 and γ2, arise from alternative promoter utilization (3, 4) and are expressed in a tissue-specific fashion (4–6). PPARγ2 is abundant in adipose tissue, where it controls glucose homeostasis and adipocyte differentiation (7, 8). PPARγ1 is expressed within diverse cell types and tissues, including liver, lung, kidney, and immune cells (5, 6, 9). The highest levels of PPARγ are found within the intestinal epithelium. Within the gut, PPARγ displays distinct expression and functional patterns along the intestinal tract. Levels of PPARγ are highest in the proximal colon, with decreasing abundance in the distal colon and small intestine (9). PPARγ expression activity in the colonic epithelium has been implicated in suppression of colon carcinogenesis and inflammation. Thiazolidinediones, a class of PPARγ agonists, inhibit aspects of differentiation in some colon cancer cell lines (10–16) and inhibit colon tumor formation in the azoxymethane mouse model of sporadic colon carcinogenesis (17–19). Knockout of PPARγ in the colonic epithelium and macrophages of mice results in increased susceptibility to experimental colitis (20, 21). Likewise, thiazolidinediones provide protection in experimental models of colitis when given preventatively, prior to disease initiation, but provide little or no value when administered therapeutically after onset of inflammation (22–29).

Our laboratory has performed genomic profiling of normal colonic intestinal epithelial cells and early stage colon cancer cells to identify changes in gene expression that will provide insight into the mechanism of suppression by PPARγ ligands (9, 30, 31). In normal intestinal epithelial cells and early stage cancer cells, the majority of PPARγ target genes were involved in metabolism and cellular adhesion/motility. However, in cancer cells, a major cohort of PPARγ-regulated genes also involved proliferation and DNA replication. Our laboratory previously characterized one of these genes, DSCR1, and showed its regulation by PPARγ plays a direct role in transformation of epithelial cells (31).

Among the target genes identified in this screen was follistatin (30), a monomeric glycoprotein expressed as two forms, FST-288 and FST-315, each with distinct properties (32). FST-288 is primarily bound to cell surface proteoglycans. FST-315 is secreted and represents the major form of follistatin. All biological effects of follistatins are due to their high affinity, irreversible binding to activins, which sequesters activins thereby preventing signaling (32–34). Activins are members of the transforming growth factor-β superfamily and are composed of two β subunits (βa and βB) arranged to form three isoforms: activin A (βA/βA), activin B (βB/βB), and activin (βA/β). Activin A is considered the most prevalent. Activins bind to a transmembrane serine/threonine kinase cell surface receptor termed ActRII. Thereafter, ActRII recruits and phosphorylates the type I receptor kinase (ActRI). The formation of the dimeric complex leads to the phosphorylation of Smad2 and -3, subsequent complex formation with Smad4, and regulation of activin responsive genes (35, 36). Activin-responsive genes have been implicated in the control of homeostasis, development, proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation, and inflammation in diverse cellular systems (37–42). The action of activins in these physiological processes is tightly controlled by a balance of expression of activins and its antagonists such as inhibin, betaglycan, follistatin, FLRP, BAMBI, and CRIPTO (43–45). Deregulation of this balance can lead to aberrant signaling and development of disease. Altered activin signaling has been implicated in a pathogenesis of diseases such as cancer (37, 41, 46–48), polycystic ovarian syndrome (49, 50), fibrosis (40, 51), and multiple inflammatory conditions (38, 52–54). Particularly, overexpression of follistatin has been observed in cancers such as of the skin (55), colon (56), prostrate (57–59), and liver (46, 60, 61). However, the role of activin-follistatin signaling in the physiology and disease of the intestinal epithelium is less clear. Activin A has been implicated in the inhibition of cell proliferation and promotion of cell migration (62, 63). Likewise, follistatin promotes cell proliferation and has been reported to ameliorate established experimental colitis (64).

In this study, we investigate regulation of follistatin expression in the intestinal epithelium by PPARγ activation in vivo and in vitro using a non-transformed, rat intestinal cell line (RIE-1) that expresses functional components of the activin-follistatin system. We demonstrate that activation of PPARγ by thiazolidinediones down-regulates FST-315 mRNA in a dose- and concentration-dependent manner at the level of mRNA synthesis. Specifically, we illustrate that PPARγ activation reduces follistatin levels by interacting with the Sp1 transcription factor required for activity of the follistatin promoter. Together, our data indicate PPARγ activation would have a beneficial effect on activin A signaling by suppressing the levels of its antagonist follistatin. Furthermore, our data suggest that growth inhibition observed with thiazolidinediones in intestinal cell lines, in part, may be due to an increase in activin signaling.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents—Recombinant follistatin and activin A were purchased from R&D Systems. Rosiglitazone maleate was purchased from ChemPacific. Troglitazone and 9-cis-retinoic acid were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. RS5444 was obtained from Sankyo Co., Ltd. SP600125 was purchased from Calbiochem. Hygromycin B and Geneticin (G418) were purchased from Invitrogen.

Plasmids—Mouse PPARγ1 expression vector pSG5-mPPARγ1 (65) and the PPARγ reporter PPRE3-TK-Luc (66) were provided by Dr. Steven A. Kliewer. The AP-1 reporter gene, (AP1)3 p54 IL8 Luc (67), was provided by Dr. Allan Brasier. The plasmid pLNCX-PPARγ was generated by amplifying PPARγ from pSG5-mPPARγ1 and subcloning the product into HpaI-ClaI sites of pLNCX (Stratagene). The PPARγ mutant plasmid pLNCX-PPARγC129S was generated with the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). pLNCX-TAM67 was generated by amplifying the full-length TAM67 sequence from pSG-TAM67 and cloning the digested a product into HpaI-ClaI sites of pLNCX (Stratagene). The follistatin promoter construct, p(–2864)rFS-Luc, was donated by Dr. Louise Bilezikjian (68). pGL3-FST(–944... +135) and pGL3-FST(–35... +135) were generated by amplifying the corresponding fragments by PCR from (–2864)rFST-Luc and cloning them into pGL3-basic (Promega, Madison, WI). Mutation of the +17... +12 Sp1 site in pGL3-FST(–35... +135) was accomplished with the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) using primers 5′-tga atc gcg cga tct gcg ggt ggc gag c-3′ and 5′-gct cgc cac cgg cag atc gcg cga ttc aat g-3′. The underlined sequence represents the mutated Sp1 site. The Gal4-Sp1 plasmid was constructed by amplifying nucleotides corresponding to amino acids 83–262 of human Sp1 from pBS-Sp1 (Addgene) and ligating into the Gal4 expression vector pSG424 (69).

Cell Lines—The non-transformed intestinal cell line, RIE-1, was maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 5% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum. RIE-PPARγ were generated as previously described (30) and cultured in 5% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 100 μg/ml hygromycin. HEK293 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. RIE-PPARγ-TAM67 cells were generated by infecting RIE-PPARγ with the retrovirus pLNCX-TAM67. Cells were selected as a population and maintained in 1000 μg/ml G418.

Animal Studies—Six-week-old female C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor, ME) were fed an AIN-76A rodent diet containing 150 ppm rosiglitazone (Research Diets) for 3 days. Mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation and cervical dislocation. All mice were maintained as part of an American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care facility. Animal experimentation was conducted in accordance with accepted standards of humane animal care according to protocols approved by the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee Animal.

Intestinal crypt cells were isolated by the EDTA-chelation method as described previously (9). Briefly, the small and large intestines were dissected and flushed with phosphate-buffered saline (4 °C). The colon and/or small intestine were cut into equal length segments in a proximal to distal orientation. Each segment was opened longitudinally to expose the luminal surface and then washed three times for 5 min at room temperature with Hanks' balanced salt solution containing 25 mm HEPES, 1% fetal bovine serum, and 1 mm dithiothreitol. Each segment was then shaken vigorously in Hanks' balanced salt solution-20 mm EDTA for 15 m at 37 °C. Supernatants containing the individual crypts were centrifuged at 1000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. RNA was extracted from the pellets (pure crypt fraction) using RNAqueous™ (Ambion).

RT-PCR Analysis—Unless otherwise indicated, two-step quantitative reverse transcriptase-mediated real-time PCR (qPCR) was used to measure the abundance of individual mRNAs. RNA was extracted from cells with the RNAqueous™ kit as detailed by the manufacturer (Ambion). Equal aliquots of total RNA from samples were converted to cDNA with the High-Capacity cDNA Archive kit (Applied Biosystems), and qPCR reactions were performed in triplicate with 10 ng of cDNA and the TaqMan® Universal PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems). All primer/probe sets were purchased from Applied Biosystems. All amplification data were collected with an Applied Biosystems Prism 7900 sequence detector and analyzed with Sequence Detection System software (Applied Biosystems). Data were normalized to GAPDH, and mRNA abundance was calculated using the ΔΔCT method (70).

ActRI, ActRII, follistatin, and activin A (βA subunit) mRNA expression was detected in the RIE-1 cell line by two-step RT-PCR. 250 μg of cDNA from RIE-1 cells was analyzed by standard PCR using AmpliTaq Gold on a Gene Amp 2700 system. PCR primers used were as follows: ActRI (5′-ctatgagcaggggaagatgac-3′ and 5′-tcgtggtaatgtgtaatgagc-3′), ActRII (5′-tcacacagcccacatcaaatc-3′ and 5′-ccacaggtccacatcaacact-3′), follistatin (5′-cctactgtgtgacctgtaatc-3′ and 5′-ctcctcttcctccgtttcttc-3′), activin-βa(5′-agaggacgacattggcaggag-3′ and 5′-gagtggaaggagagtgaggac-3′), and GAPDH (5′-gccatcaacgaccccttcatt-3′ and 5′-cgcctgcttcaccaccttctt-3′).

RNA Interference—shRNA MISSION™ RNA interference lentiviral transduction plasmids for SP1 were obtained through the Mayo Clinic RNA Interference Technology Resource. Lentivirus stock was produced with Virapower™ lentivirus packaging mix and the 293FT cell line according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen). RIE-PPARγ cells grown to 70% confluence were infected with a 1:10 dilution of virus to target cell media and 6 μg/ml Polybrene. After a 24-h recovery, cells were washed and re-fed with complete media. At 48 h post-infection, cells were harvested, and knockdown efficiency was assessed by qPCR and/or Western blot.

Western Blot Analysis—Total cell lysates were prepared by briefly sonicating cell pellets in 1× lysis buffer (Roche Applied Science) supplemented with a protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma). Protein samples were resolved on 8% pre-cast Trisglycine gels (Invitrogen) and were electrophoretically transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Blots were stained with antibodies against PPARγ (1:300, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), Sp1 (0.5 μg/ml, Millipore), c-Jun (1:300, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), phospho-SAPK/JNK (1:100, Cell Signaling), or β-actin (1:1000, Sigma) in TTBS (50 mm Tris, 150 mm NaCl, 0.15% Tween, pH 7.5) supplemented with 5% dry milk for 1 h at 22 °C. Blots were washed with three changes of TTBS for a total of 45 min. Blots were then incubated in TTBS buffer with 5% dry milk containing GAR-HRP (1:5000, Jackson ImmunoResearch) or GAM-HRP (1:5000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1 h at room temperature. After three washes with TTBS, antigen-antibody complexes were detected with the ECL Plus chemiluminescent system (Amersham Biosciences) and visualized with film.

Immunoprecipitation—Nuclear extracts were prepared from RIE-1 and RIE-PPARγ cells using the NE-PER extraction kit (Pierce). 500 μg of nuclear extract was pre-cleared with 50 μl of magnetic Protein G-Dynabeads in immunoprecipitation buffer (150 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 1 mm EDTA, 0.5% Triton) for 15 m at 4 °C. The pre-cleared extract was rotated for 4 h at 4 °C with 50 μl of Protein G-Dynabeads covalently linked with 5 μg of Sp1 antibody according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Beads were collected by magnetic separation and washed five times × 2 min with 1 ml of immunoprecipitation buffer. Beads were resuspended in 50 μl of 2× Laemmli sample buffer, boiled for 5 min at 95 °C, and resolved by SDS-PAGE.

Reporter Gene Assays—Cells were plated onto 12-well plates at 1 × 105 cells/well and allowed to recover 16 h before transfection. Cells were transfected with 0.5–1 μg of DNA (depending on experiment) and a 1:50 dilution of pRL-SV40 with Fugene according to manufacturer's instructions (Roche Applied Science). After a 24-h recovery, the appropriate ligand was added to each well and incubated for the desired time (see figure legends). Cells were then scraped in 1× reporter gene assay buffer (Roche Applied Science), vortexed, and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. Luciferase activity was determined using a Promega Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay on a Veritas Microplate Luminometer (Turner Biosystems). Firefly luciferase activity was normalized by dividing by readings for Renilla. All samples were performed in triplicate and expressed as mean ± S.D.

RESULTS

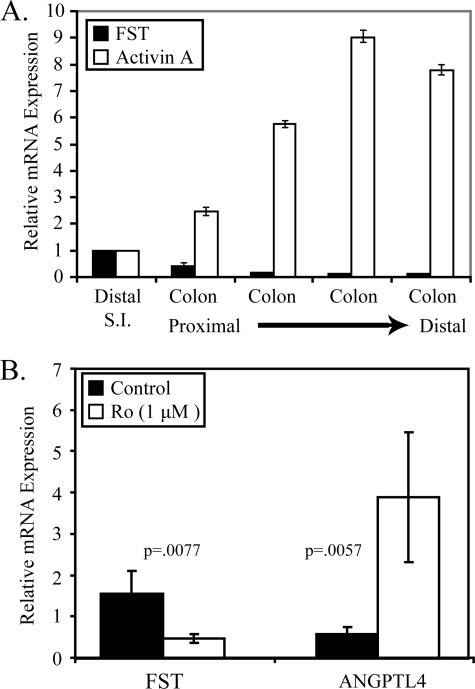

Follistatin Is Down-regulated by Rosiglitazone in Colonic Epithelial Cells in Vivo—Our genomic analyses suggested that follistatin is expressed in intestinal epithelial cells and is a potential target of the PPARγ agonists (30). To confirm these findings, we initially measured the expression of follistatin and activin A, the physiological target of follistatin, in purified intestinal epithelial cells from the distal small intestine and four segments of colon of equal length extending proximal to distal from the caecum to the rectum. RNA was isolated, and the expression of total follistatin (including both FST-315 and FST-288) and activin A (βA subunit) was measured by qPCR. We observed an inverse relationship between follistatin and activin A along the colonic tract (Fig. 1A), with the highest levels of follistatin detected in the distal small intestine and proximal colon. Conversely, activin A mRNA was most abundant in the distal colonic epithelium. These data are consistent with previous findings and support the hypothesis that the activin/follistatin signaling axis plays a significant role in controlling proliferation of intestinal epithelial cells in vivo.

FIGURE 1.

Activation of PPARγ by rosiglitazone down-regulates follistatin mRNA in colon epithelial cells in vivo. A, qPCR was used to measure total follistatin and activinβA mRNA in intestinal epithelial cells isolated from distal small intestine and 4 equal length colonic segments extending from proximal to distal. mRNA was normalized to GAPDH. For each probe, normalized mRNA of small intestine was set to 1. Abundance of mRNA from colonic segments is expressed as -fold change relative to the small intestine. Each bar represents mean ± S.D., n = 3. B, C57BL6/J mice were fed either a control diet or diet supplemented with 150 ppm rosiglitazone for 3 days. RNA was extracted from intestinal epithelial cells isolated from the entire colon, and qPCR was used to measure total follistatin and ANGPTL4 mRNA expression. Relative mRNA levels were normalized to GAPDH and expressed as -fold change relative to the control. Each bar represents mean ± S.D., n = 4. p values were calculated by unpaired t test.

Our genomic analysis of PPARγ targets in non-transformed intestinal epithelial cells suggested that follistatin expression was regulated by PPARγ in such cells. To determine if follistatin expression was regulated by PPARγ in vivo, C57BL/6J mice were fed a control diet or a diet containing 150 ppm rosiglitazone for 3 days. Epithelial cells crypts were isolated from colons of mice, and RNA was extracted. qPCR was used to measure the abundance of individual mRNAs. Rosiglitazone induced angiopoietin-like protein 4 (ANGPTL4), a known PPARγ target gene (Fig. 1B) in colonic epithelial cells. Follistatin mRNA expression was repressed in colonic epithelial cells in response to rosiglitazone, consistent with our genomic data. Collectively, our data indicate that follistatin is expressed throughout the gastrointestinal track, and its expression is negatively regulated by the PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone.

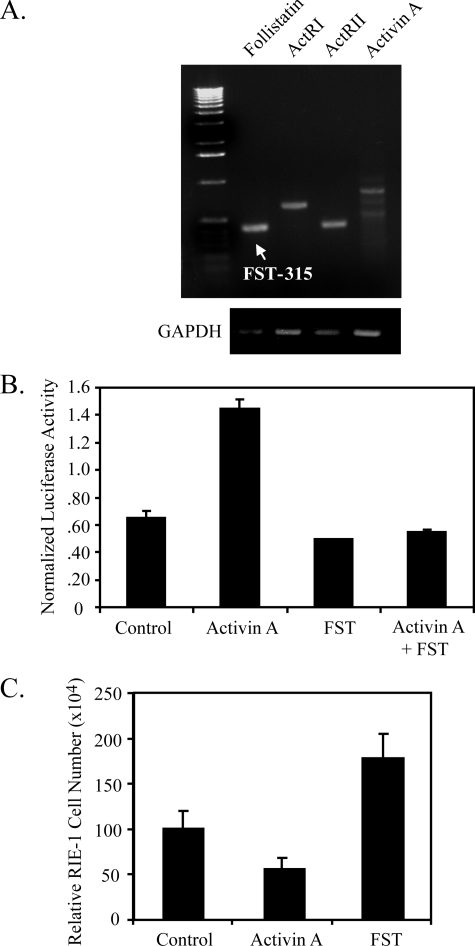

RIE-1 Cells as a Model System to Study Follistatin Regulation—To study the regulation of follistatin expression by rosiglitazone in intestinal cells, a model cell system was required that recapitulates the properties of non-transformed intestinal epithelial cells and expresses functional activin/follistatin and PPARγ signaling pathways. Normal, non-transformed colon cell lines do not exist, and primary cultures of colonic epithelium have not been successfully maintained for more than a few hours. However, RIE-1 cells are a well characterized non-transformed rat intestinal epithelial cell line that was derived from embryonic small intestine. RIE-1 cells were evaluated for expression and functional activity of the components of the activin-follistatin signaling pathway, as shown in Fig. 2A. Follistatin and activin A mRNA were detected by RT-PCR, as well as mRNA for the activin receptor subunits ActRI and ActRII. There are two major follistatin species of 315 and 288 amino acids. FST-315 was the major form expressed in RIE-1 cells, whereas FST-288 was undetectable by RT-PCR. Expression of activin A and follistatin mRNA in RIE-1 cells was confirmed by qPCR (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

Activin/follistatin signaling is intact in intestinal epithelial cells. A, RT-PCR was used to amplify expression of follistatin, ACTRI, ACTRII, activin A (βA), and GAPDH from 250 ng of cDNA prepared from RIE-1 cells. The arrow indicates that follistatin-315 is the major form of follistatin expressed in RIE-1 cells. B, activation of the activin responsive reporter gene, 3TP-luc, in RIE-1 cells exposed to recombinant activin A (50 ng/ml), follistatin (250 ng/ml), or both for 16 h. C, cell growth of RIE-1 cells exposed to recombinant activin or follistatin for 5 days. Data are expressed as the relative number of cells compared with control at day 5. Each bar represents mean ± S.D., n = 12.

To assess the functional activity of activin/follistatin signaling in RIE-1 cells, we initially determined the activity of a transiently transfected activin-responsive reporter gene, 3TP-Luc, in RIE-1 cells treated with recombinant activin A and/or follistatin. Activin A activated the 3TP-luc reporter in RIE-1 cells (Fig. 2B). Follistatin caused a slight but consistent inhibition of basal 3TP-luc activity, and activin-mediated transactivation of the 3TP-luc reporter was antagonized by recombinant follistatin. These data indicate that RIE-1 cells manifest a functional activin-follistatin signaling axis.

Activin is a potent inhibitor of cell proliferation, and recombinant activin A suppressed RIE-1 culture growth (Fig. 2C). Conversely, recombinant follistatin stimulated RIE-1 culture growth (Fig. 2C). These data are consistent with the known growth-modulating effects of activin and follistatin and indicate that RIE-1 cells express a functional activin-follistatin signaling pathway and that growth of RIE-1 cultures is restrained by endogenous activin under basal culture conditions.

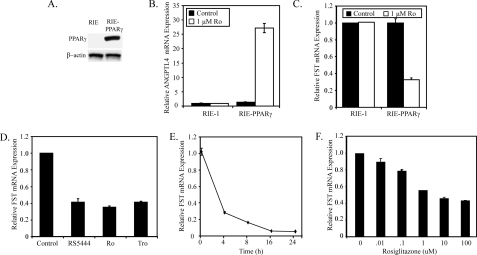

Characterization of PPARγ-mediated Down-regulation of Follistatin Expression in RIE-1 Cells—RIE-1 cells are non-transformed, rat intestinal epithelial cells derived from proliferative, transit crypt cells of embryonic rat intestine (71). Like the transit-amplifying cells from which they are derived (72), RIE cells express low levels of PPARγ (Fig. 3A). PPARγ is induced at the crypt/villus junction (30), where transit-amplifying cells differentiate into mature villus epithelial cells. To recapitulate this transition and model mature villus epithelial cells, we have engineered RIE-1 cells to express PPARγ (Fig. 3A). The RIE-PPARγ cell line has been previously studied in detail, mimics the physiological functions of PPARγ in intestinal epithelial cells in vivo (30, 73), and were used to study the effects of PPARγ activation on follistatin expression in culture.

FIGURE 3.

Characterization of PPARγ-mediated down-regulation of follistatin expression in intestinal epithelial cells. A, Western blot analysis of 20 μg of total cell lysate of RIE-1 and RIE-PPARγ cells stained for PPARγ and β-actin expression. B and C, the mRNA abundance of the PPARγ target gene ANGPTL4 and follistatin was measured by qPCR in RIE-1 and RIE/PPARγ cells treated with 1 μm rosiglitazone for 6 h. D, follistatin mRNA abundance was quantified by qPCR in RIE-PPARγ cells exposed to RS5444 (10 nm), rosiglitazone (1 μm), or troglitazone (10 μm) for 6 h. E, RIE-PPARγ cells were exposed to rosiglitazone for the indicated times. At each time point, RNA was harvested, and follistatin expression was determined by qPCR. F, RIE-PPARγ cells were treated with increasing concentrations of rosiglitazone for 6 h, and follistatin mRNA was measured by qPCR. In all experiments, the abundance of mRNA was normalized to GAPDH expression and presented as -fold change relative to the control. Each bar represents mean ± S.D., n = 3.

Treatment of RIE-PPARγ cells with rosiglitazone induced ANGPTL4 (Fig. 3B) and repressed follistatin mRNA expression (Fig. 3C), thereby demonstrating that RIE-PPARγ cells recapitulate the regulatory response that we observed in vivo. Thiazolidinedione drugs such as rosiglitazone are known to have effects that are independent of PPARγ activation (74–76). However, rosiglitazone had no effect on follistatin expression in RIE-1 cells (Fig. 3C), which lack PPARγ. This result indicates that inhibition of follistatin expression by rosiglitazone requires PPARγ. This conclusion is consistent with the observation that other thiazolidinedione PPARγ agonists such as troglitazone and RS5444 inhibited follistatin expression in RIE-PPARγ cells (Fig. 3D).

Our studies focused on the response to rosiglitazone, which is currently used clinically for management of type II diabetes. Rosiglitazone decreased follistatin expression in a time-dependent manner, with maximal repression observed 8–16 h after addition of the drug (Fig. 3E). Rosiglitazone inhibited follistatin expression in a concentration-dependent manner, and maximum inhibition was observed in the range of 1 μm agonist (Fig. 3F).

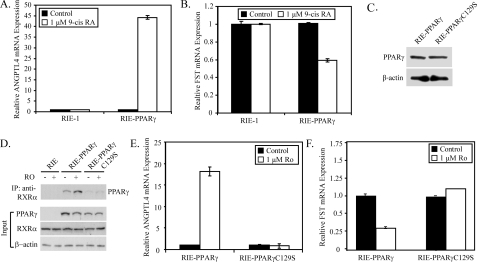

Requirements of PPARγ for Down-regulation of Follistatin Expression—The PPARγ/RXRα heterodimer is activated by ligands that bind to PPARγ, such as thiazolidinediones, as well as ligands that bind to RXRα, such as 9-cis-retinoic acid. To evaluate whether the effects of PPARγ required dimerization with RXRα, RIE-1 and RIE-PPARγ cells were treated with 9-cis-retinoic acid, which induced ANGPTL4 mRNA (Fig. 4A) and repressed follistatin mRNA (Fig. 4B) in RIE-PPARγ cells, but had no effect on ANGPTL4 or follistatin expression in RIE-1 cells, which express RXRα but lack PPARγ. These data suggest that dimerization of PPARγ with RXRα is required for repression of follistatin levels.

FIGURE 4.

PPARγ requires dimerization with RXRα for repression of follistatin expression. A and B, RIE-1 and RIE-PPARγ cells were treated with 1 μm 9-cis-retinoic acid 9 (9-cis RA) for 6 h. qPCR was used to measure follistatin (A) and ANGPTL4 (B) mRNA expression. C, Western blot of 20 μg of total cell lysate prepared from RIE-1 cells stably expressing WT PPARγ or PPARγC129S. D, nuclear extracts (500 μg) from RIE-1, RIE-PPARγ, and PPARγC129S cells treated with or without rosiglitazone for 6 h were immunoprecipitated with an anti-RXRα antibody and stained for expression of PPARγ by Western blot (lower panel). The Western blot in the lower panel represents 20 μg of the input nuclear extracts stained for PPARγ, RXRα, and β-actin. E and F, abundance of follistatin (E) and ANGPTL4 (F) was measured in cultures of RIE-PPARγ and RIE-PPARγC129S cells treated with vehicle or rosiglitazone (1 μm) for 6 h. Abundance of mRNA was normalized to GAPDH and expressed as -fold change relative to the control. Each bar represents mean ± S.D., n = 3.

To confirm that a PPARγ/RXRα heterodimer was required for repression of follistatin levels, an RIE-1 cell line was generated that stably expresses the PPARγ C129S mutant at levels comparable to those observed for wild-type PPARγ in RIE-PPARγ cells (Fig. 4C). PPARγC129S contains a cysteine to alanine mutation in residue 129 of the first zinc finger of the DNA binding domain. This mutation severely inhibits the dimerization, DNA binding, and transactivation potential of PPARγ. Fig. 4D illustrates that an RXRα antibody effectively co-precipitated wild-type PPARγ from RIE-PPARγ cells, whereas coprecipitation of PPARγC129S from RIE-PPARγC129S cells was significantly reduced. Likewise, the reduction in PPARγ/RXRα heterodimer formation led to a loss of rosiglitazone-mediated regulation of ANGPTL4 (Fig. 4E) and follistatin (Fig. 4F) in RIE-PPARγC129S cells. These data indicate that rosiglitazone-mediated repression of follistatin expression is mediated by the PPARγ/RXRα heterodimer.

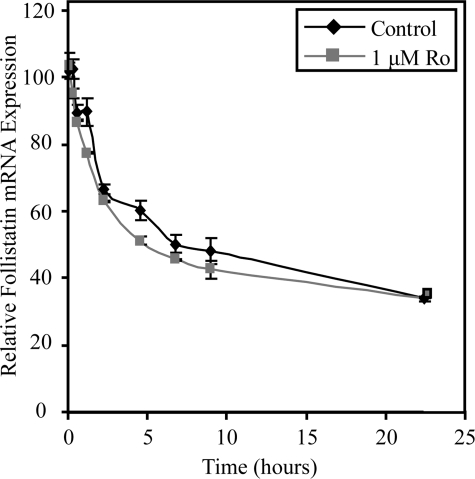

Mechanism of PPARγ Inhibition of Follistatin Expression—In principle, inhibition of follistatin expression could be due to PPARγ/RXRα-mediated inhibition of follistatin mRNA synthesis or to stimulation of follistatin mRNA degradation. To discriminate between these alternatives, control or rosiglitazone-treated RIE-PPARγ cells were treated with actinomycin D, and the abundance of follistatin mRNA was measured as a function of time thereafter. Rosiglitazone had no significant effect on follistatin mRNA stability in RIE-PPARγ cells (Fig. 5), indicating that the turnover rate of follistatin mRNA is not affected by activation of PPARγ.

FIGURE 5.

PPARγ-mediated down-regulation of follistatin occurs at the level of mRNA synthesis. RIE-PPARγ cells were pretreated with rosiglitazone (1 μm) for 3 h and then subsequently exposed to actinomycin D (5 μg/ml) for the indicated times. At each time point, RNA was harvested, and follistatin expression was determined by qPCR. The abundance of follistatin mRNA was normalized to GAPDH and expressed as -fold change relative to the control. Each bar represents mean ± S.D., n = 3.

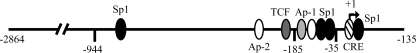

The observation that follistatin mRNA abundance decreases with no rosiglitazone-associated change in the rate of mRNA degradation indicates that PPARγ regulates the rate of synthesis of the follistatin transcript and suggests that PPARγ regulates follistatin promoter activity. The follistatin promoter contains binding sites for AP-1, AP-2, CREB, and Sp1 clustered in the proximal region (Fig. 6). A previous study of the rat follistatin promoter indicated that full promoter activity in granulosa cells required only 115 bp of 5′-flanking sequence. This region contains binding sites for AP-1 and Sp1, transcription factors known to be repressed by interactions with PPARγ (77–84). Inhibitors of JNK and AP-1 were used to determine whether the AP-1 pathway mediates the negative effects of PPARγ activation on follistatin levels (data shown in supplemental Fig. S1). The results of these experiments indicate that PPARγ inhibition of follistatin expression is not mediated by cross-talk with AP-1 signaling.

FIGURE 6.

Schematic representation of the follistatin promoter. The follistatin promoter contains consensus binding sites for AP-1, AP-2, CREB, and Sp1. Binding sites are relative to the transcriptional start site (+1).

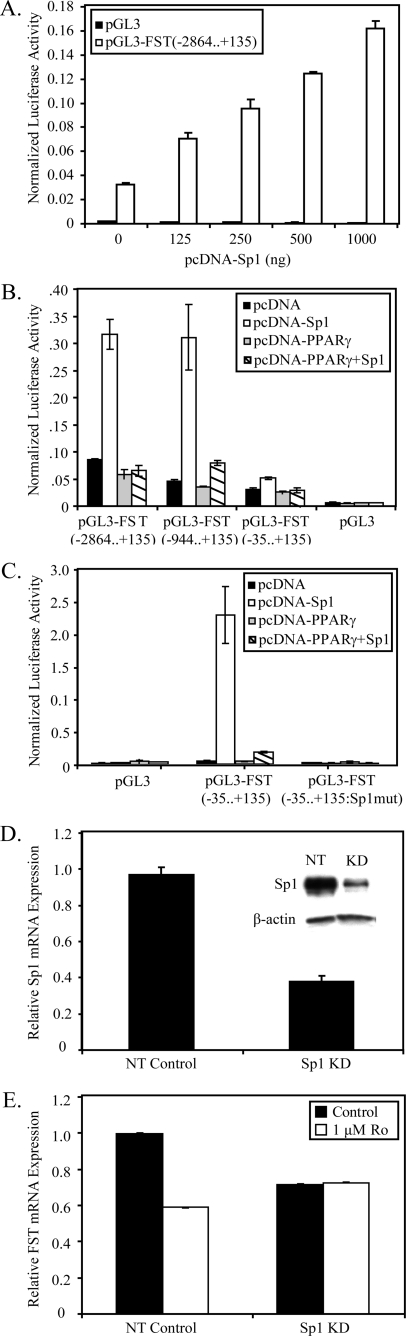

We next asked whether Sp1 has a role in rosiglitazone-mediated down-regulation of follistatin expression. Studies with the highly similar promoter of the follistatin-related gene (FLRG) have shown that a fragment between positions –130 and +6 contains multiple consensus Sp1-binding sites which control the basal expression of the FLRG gene (85). The proximal follistatin promoter also contains several Sp1 sites (Fig. 6), suggesting a potential role of Sp1 in regulating follistatin expression. To determine the importance of Sp1 in regulating basal follistatin promoter activity, Sp1 was co-transfected in increasing concentrations with a luciferase reporter gene containing a region encompassing –2864 to + 135 bases of the follistatin promoter (Fig. 6). These studies were carried out in HEK293 cells instead of RIE-PPARγ cells, because the latter has extremely poor transfection efficiencies. Fig. 7A illustrates that co-transfected Sp1 dramatically up-regulated the follistatin promoter in a concentration-dependent manner. Truncations of the follistatin promoter were generated to produce reporter constructs containing regions –944/+135 and –35/+135 (Fig. 6). Fig. 7B shows the basal transcriptional activity of the follistatin promoter constructs in HEK293 cells. At least 50% of the basal activity of full-length follistatin promoter (–2864/+135) could be attributed to a region of the promoter from –35/+135, which contains a single Sp1 site. Likewise, the –944/+135 region that contains three additional Sp1 sites, for a total of 4 Sp1 sites, exhibited ∼75% of the basal activity of the full-length promoter. Overexpression of Sp1 led to induction of each follistatin promoter construct, with the highest activation observed with the –2864/+135 and –944/+135 promoter constructs (Fig. 7B). To further delineate the importance of Sp1 in controlling promoter activity, we mutated the Sp1 site at +17/+12 within the pGL3-FST(–35/+135) reporter construct. Fig. 7C shows that mutation of the Sp1 site reduced promoter activity to the level of pGL3 and destroyed the ability of a high level expression of Sp1 expression to induce promoter activity. Collectively, these data indicate that Sp1 regulates follistatin promoter activity, and in a manner that is largely dependent on a proximal Sp1 site at +17 bp.

FIGURE 7.

PPARγ inhibits follistatin expression through Sp1. A, 100 ng of control (pGL3) or the follistatin promoter pGL3(–2864... +135) was transiently transfected with increasing concentrations of pcDNA-Sp1 or pcDNA3.1, and luciferase activity was determined 48 h later. B, basal transcriptional activity of truncated follistatin promoter constructs 48 h after transfection into 293 cells. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with 100 ng of pGL3(–2864... +135), pGL3(–944... +135), pGL3(–35... +135), and pGL3-luc with or without pcDNA-Sp1(500 ng) and with or without pcDNA-PPARγ (500 ng). Firefly luciferase activity was determined 48 h after transfection. C, HEK293 cells were transfected with 100 ng of pGL3, pGL3(–35... +135), and pGL3(–35... +135:Sp1mut) reporter construct containing a mutated Sp1 site at +17... +12 along with or without pcDNA-Sp1 (1000 ng) and with or without pcDNA-PPARγ (500 ng). The total amount of DNA in each transfection was kept constant with pcDNA3.1. 48 h later, luciferase activity was determined. For all luciferase assays, pRL-SV40 (1:50 total DNA) was included in the transfection reaction to monitor transfection efficiency. All data were normalized for transfection efficiency by dividing by Renilla pRL-SV40 activity. All data represent a representative experiment with a mean ± S.D., n = 6.D, RIE-PPARγ cells were infected with Sp1 shRNA knockdown or nontarget control lentivirus. Sp1 abundance was measured by qPCR and Western blot analysis (inset). E, control and Sp1 knockdown RIE-PPARγ cells were treated with rosiglitazone for 6 h. The relative abundance of follistatin mRNA abundance was determined by qPCR. All qPCR data were normalized to GAPDH and represent mean ± S.D., n = 3.

Because Sp1 appears to be a major regulator of follistatin expression, we asked whether rosiglitazone-mediated down-regulation of follistatin was due to inhibition of Sp1 signaling. Co-expression of PPARγ with Sp1 inhibited Sp1-mediated activation of each follistatin promoter truncation constructs but had no effect on the pGL3-control reporter gene (Fig. 7B). Significantly, PPARγ was capable of inhibiting Sp1-mediated induction of the –35/+135 promoter construct, which is dependent upon a single Sp1 site for activity. These findings suggested that PPARγ regulates follistatin expression through inhibition of Sp1 signaling. To further demonstrate this, lentivirus-mediated shRNA was used to transiently knock down Sp1 expression in RIE-PPARγ cells. Transient knockdown of Sp1 mRNA and protein with an efficiency of >60% was achieved in RIE-PPARγ cells 2 days after infection (Fig. 7D). Knockdown of Sp1 reduced basal expression of follistatin, consistent with findings that Sp1 is a major factor controlling follistatin expression (Fig. 7E). More importantly, Sp1 knockdown completely blocked rosiglitazone-mediated inhibition of follistatin mRNA expression (Fig. 7E). Together, our data provide compelling evidence that PPARγ reduces follistatin through inhibition of Sp1 signaling required for its expression.

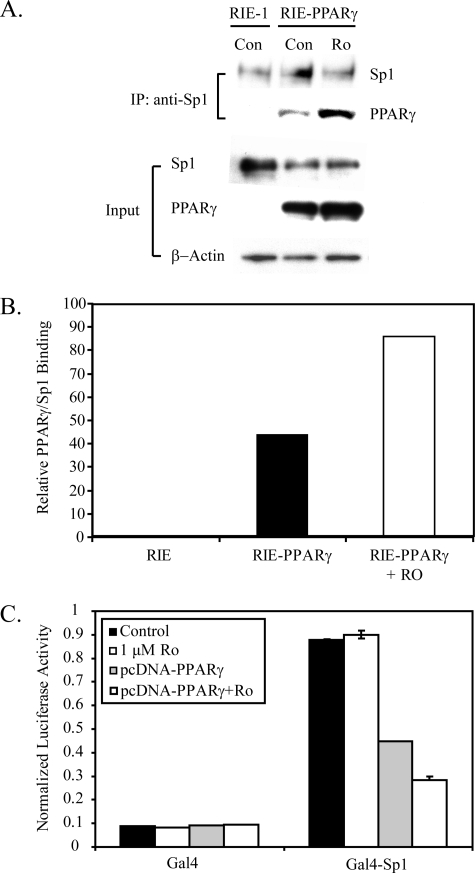

The mechanism of rosiglitazone-mediated inhibition of follistatin expression may occur by inhibiting Sp1 via complex formation with PPARγ or by regulating a factor upstream of Sp1 required for its activity. To assess whether PPARγ interacted with Sp1, immunoprecipitation studies were performed with nuclear extracts from RIE-PPARγ cells treated with or without rosiglitazone. Fig. 8 (A and B) shows that PPARγ co-precipitated with Sp1 and the interaction was enhanced in the presence of rosiglitazone. These data indicate that PPARγ interacts with Sp1, but raises the question of how this interaction results in inhibition of Sp1 activity. In principle, complex formation of PPARγ with Sp1 could result in loss of Sp1 DNA binding or interference of Sp1 transcriptional activity. However, no difference in Sp1 binding activity was observed in nuclear extracts from RIE-PPARγ cells treated with or without rosiglitazone (data not shown). To determine the importance of PPARγ in directly regulating the transactivation function of Sp1, a fusion construct (Gal4-Sp1) was generated that contains a transactivation domain of Sp1 (amino acids 83–263) fused to the Gal4 DNA binding domain (GAL4). HEK293 cells were co-transfected with GAL4 or GAL4-Sp1 with or without the PPARγ expression plasmid. Cells were treated with rosiglitazone for 24 h and analyzed for their transactivation potential by measurement of activation of pG5-Luc, a Gal4-responsive luciferase reporter gene. Consistent with the known transactivation function of amino acids 83–262 of Sp1, Gal4-Sp1 activated pG5-Luc 18-fold over Gal4 alone (Fig. 8C). Importantly, co-expression of PPARγ repressed the transcriptional activity of GAL4-Sp1, and this repression was further enhanced by treatment with rosiglitazone. Expression of PPARγ had no effect on the DNA binding activity of GAL4-Sp1 (data not shown), indicating PPARγ directly inhibits the transcriptional activation function of Sp1 dictated by amino acids 83–262. Collectively, these data indicate that PPARγ interacts with Sp1 and suppresses its transcriptional activation function, leading to loss of promoter control of follistatin and down-regulation of follistatin expression.

FIGURE 8.

PPARγ interacts with Sp1 and represses its transcriptional activity. A, nuclear extracts (500 μg) from RIE-1 cells and RIE-PPARγ cells treated with or without rosiglitazone (1 μm) for 6 h were immunoprecipitated with Sp1 antibody and stained by Western blot for PPARγ and Sp1 expression (upper panel). The Western blot in the lower panel represents 10 μg of the input nuclear extracts stained for PPARγ, Sp1, and β-actin. B, ImageJ software was used to calculate densitometry of immunoprecipitated Sp1 and PPARγ bands in panel A. The level of immunoprecipitated PPARγ was normalized to immunoprecipitated Sp1 for each sample and graphed as relative PPARγ/Sp1 binding. C, HEK293 cells were transfected with 1000 ng of Gal4-responsive luciferase vector, pG5-Luc, along with 250 ng of constructs expressing Gal4 (amino acids 1–147) or Gal4-Sp1 (amino acids 83–262) with or without pcDNA-PPARγ (500 ng). pRL-SV40 (1:50 total DNA) was included in the transfection reaction to monitor transfection efficiency. The total amount of DNA in each transfection was kept constant with pcDNA3.1. Cells were treated with rosiglitazone (1 μm) for 24 h, and luciferase activity was determined. All data were normalized for transfection efficiency by dividing by Renilla activity. All data represent a representative experiment with a mean ± S.D., n = 3.

DISCUSSION

Activins control many physiological processes that include cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, homeostasis, immune response, wound repair, and endocrine signaling (36, 37, 39, 40). The action of activins in these physiological processes is tightly controlled by a balance of expression of activins and its antagonists such as follistatin. Deregulation of this balance can lead to aberrant signaling and development of disease. However, little is known about the control of follistatin expression in diverse cell types and its importance in disease progression. Follistatin expression has been reported to be controlled at the promoter level by CREB in granulose cells (86), by SMADS in hepatoma (87) and pituitary cells (68), and by β-catenin in embryonic carcinoma cells (88). Transforming growth factor-β and β-catenin are well known players in carcinogenesis, and regulation by these factors may provide a possible link between and follistatin expression and carcinogenesis. However, their roles and the regulation of follistatin by other factors in specific cell types and disease remain largely unexplored. Specifically, the regulation of follistatin expression in the gastrointestinal tract remains unclear.

Herein, we report that follistatin is differentially expressed in epithelial crypts of the small and large intestine and through the use of a non-transformed, rat intestinal cell line (RIE-1) we illustrate that intestinal cells express a functional activin-follistatin system. Importantly, we show that expression of follistatin in vivo and in vitro is down-regulated by PPARγ activation with synthetic thiazolidinediones. Suppression of follistatin levels by PPARγ activation required RXRα and did not involve changes in follistatin mRNA stability but rather transcriptional suppression of the follistatin promoter. Our data indicate that PPARγ down-regulates follistatin expression by directly interacting with Sp1 and repressing its transcriptional activity, which is required for activity of the follistatin promoter in intestinal epithelial cells. In particular, while PPARγ can inhibit promoter constructs that contain all four Sp1 sites (–944), much of PPARγ's inhibitory action is mediated through a proximal Sp1 site +17... +12 that regulates >50 of the activity of the follistatin promoter. Mutation of this Sp1 site in a pGL3-FST(–35... +135) reporter construct abolished the transcriptional response to Sp1 and PPARγ and reduced promoter activity to the level of pGL3. The significance of the +17... +12 Sp1 site is supported by the finding that a region encompassing –35 to +139 also drives >50% of the rat follistatin promoter basal activity in granulose cells (86). Collectively, our data indicate that PPARγ activation reduces follistatin levels by interacting with the Sp1 transcription factor required for activity of the follistatin promoter.

Our observations are consistent with other studies. For example, activation of PPARγ by 15d-PGJ2 and troglitazone suppresses both thromboxane receptor and type angiotensin II receptor gene expression in vascular smooth muscle cells by direct interaction of PPARγ with Sp1 at a Sp1 DNA binding site (80, 81). Likewise, PPARγ represses resistin gene expression by modulating Sp1 activity at a proximal Sp1 promoter site and by reducing the O-glycosylation status of Sp1 (84). In human lung carcinoma cells, 15d-PGJ2, rosiglitazone, and troglitazone inhibit fibronectin (Fn) gene expression in part by reducing Sp1 expression and preventing Sp1 binding to its respective sites within the Fn promoter (83). Lastly, PPARα represses vascular endothelial growth factor-2 expression by directly interacting with Sp1 and decreasing its binding to the VEGFR2 promoter (82). Collectively, these studies illustrate a common theme that PPARγ can repress promoter-specific gene expression by direct interaction with Sp1 at DNA binding sites. Our data indicate repression of follistatin expression by rosiglitazone requires a direct interaction of PPARγ with Sp1 and Sp1 binding sites within the follistatin promoter.

A limited number of studies has addressed the physiological role of activin-follistatin signaling in intestinal epithelial cells. As with transforming growth factor-β, activin A has been reported to inhibit cell proliferation and promote differentiation and migration of the intestinal epithelial cell line IEC-6 (62, 63). In contrast, follistatin promoted division of colonic epithelial cells in vivo (64). We have shown that activin A and follistatin, respectively, suppress and promote proliferation of RIE-1 cells. These studies suggest a role for activin-follistatin signaling in the proliferation, differentiation, and migration of epithelial cells in the intestine. Moreover, these studies implicate activin-follistatin signaling in the control of epithelial renewal, wound repair, and inflammation as well as cancer progression, which is regulated by an interplay of proliferation, differentiation, and migration.

Our data suggests that PPARγ activation would have a beneficial effect on activin A signaling by suppressing the levels of its antagonist follistatin. We propose that this action may, at least in part, mediate the effects of thiazolidinediones on growth and migration in intestinal epithelial cells. Similar to the effects of activin A, activation of PPARγ promotes the migration and inhibits cell proliferation of intestinal cells (9–11, 13, 15, 16, 30). The simplest interpretation of these data is that PPARγ-mediated down-regulation of follistatin levels leads to an increase in available activin A, thereby suppressing cell proliferation and/or promoting migration. However, the impact that follistatin down-regulation will have on activin signaling may be more complex and depend on the relative levels of activin A to follistatin and its other antagonists (FLRP, inhibin, and others). In intestinal epithelial cells in vitro (IEC-6 and RIE-1), the balance of activin to its antagonists can be shifted by addition of recombinant activin A or follistatin. However, the ratio of activin to antagonist expression in vivo remains undefined. It therefore remains unclear what size of change in follistatin or antagonist expression would shift activin signaling in a negative direction. Our data indicate that activin A and follistatin show distinct patterns of expression along the gastrointestinal tract, indicating the balance of these proteins is tightly regulated. Further research is needed to understand how the balance of activin and its antagonists controls physiological processes in the gastrointestinal tract. With such information, it will be possible to define regions within the gut in which PPARγ-mediated down-regulation of follistatin is expected to have the biggest impact on activin signaling and the physiological processes of intestinal epithelial cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jennifer Havens for valuable technical assistance in RNA interference procedures.

This work was supported by the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation and the Mayo Foundation. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. S1.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ; RT, reverse transcription; qPCR, quantitative reverse transcriptase-mediated real-time PCR; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; JNK, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase; SAPK, stress-activated protein kinase; HRP, horseradish peroxidase; ANGPTL4, angiopoietin-like protein 4; RXR, retinoid X receptor; shRNA, short hairpin RNA; CREB, cAMP-response element-binding protein.

References

- 1.Evans, R. M. (1988) Science 240 889–895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sonoda, J., Pei, L., and Evans, R. M. (2008) FEBS Lett. 582 2–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu, Y., Qi, C., Korenberg, J. R., Chen, X. N., Noya, D., Rao, M. S., and Reddy, J. K. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92 7921–7925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mukherjee, R., Jow, L., Croston, G. E., and Paterniti, J. R., Jr. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 8071–8076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fajas, L., Auboeuf, D., Raspe, E., Schoonjans, K., Lefebvre, A. M., Saladin, R., Najib, J., Laville, M., Fruchart, J. C., Deeb, S., Vidal-Puig, A., Flier, J., Briggs, M. R., Staels, B., Vidal, H., and Auwerx, J. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 18779–18789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Escher, P., Braissant, O., Basu-Modak, S., Michalik, L., Wahli, W., and Desvergne, B. (2001) Endocrinology 142 4195–4202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tontonoz, P., Hu, E., and Spiegelman, B. M. (1994) Cell 79 1147–1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu, E., Tontonoz, P., and Spiegelman, B. M. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92 9856–9860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Su, W., Bush, C. R., Necela, B. M., Calcagno, S. R., Murray, N. R., Fields, A. P., and Thompson, E. A. (2007) Physiol. Genomics 30 342–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarraf, P., Mueller, E., Jones, D., King, F. J., DeAngelo, D. J., Partridge, J. B., Holden, S. A., Chen, L. B., Singer, S., Fletcher, C., and Spiegelman, B. M. (1998) Nat. Med. 4 1046–1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitamura, S., Miyazaki, Y., Shinomura, Y., Kondo, S., Kanayama, S., and Matsuzawa, Y. (1999) Jpn J. Cancer Res. 90 75–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang, T. H., and Szabo, E. (2000) Cancer Res. 60 1129–1138 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta, R. A., Sarraf, P., Brockman, J. A., Shappell, S. B., Raftery, L. A., Willson, T. M., and DuBois, R. N. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 7431–7438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kato, M., Kusumi, T., Tsuchida, S., Tanaka, M., Sasaki, M., and Kudo, H. (2004) J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 130 73–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshizumi, T., Ohta, T., Ninomiya, I., Terada, I., Fushida, S., Fujimura, T., Nishimura, G., Shimizu, K., Yi, S., and Miwa, K. (2004) Int. J. Oncol. 25 631–639 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brockman, J. A., Gupta, R. A., and Dubois, R. N. (1998) Gastroenterology 115 1049–1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marin, H. E., Peraza, M. A., Billin, A. N., Willson, T. M., Ward, J. M., Kennett, M. J., Gonzalez, F. J., and Peters, J. M. (2006) Cancer Res. 66 4394–4401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osawa, E., Nakajima, A., Wada, K., Ishimine, S., Fujisawa, N., Kawamori, T., Matsuhashi, N., Kadowaki, T., Ochiai, M., Sekihara, H., and Nakagama, H. (2003) Gastroenterology 124 361–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka, T., Kohno, H., Yoshitani, S., Takashima, S., Okumura, A., Murakami, A., and Hosokawa, M. (2001) Cancer Res. 61 2424–2428 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adachi, M., Kurotani, R., Morimura, K., Shah, Y., Sanford, M., Madison, B. B., Gumucio, D. L., Marin, H. E., Peters, J. M., Young, H. A., and Gonzalez, F. J. (2006) Gut 55 1104–1113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah, Y. M., Morimura, K., and Gonzalez, F. J. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 292 G657–G666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Su, C. G., Wen, X., Bailey, S. T., Jiang, W., Rangwala, S. M., Keilbaugh, S. A., Flanigan, A., Murthy, S., Lazar, M. A., and Wu, G. D. (1999) J. Clin. Invest. 104 383–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Desreumaux, P., Dubuquoy, L., Nutten, S., Peuchmaur, M., Englaro, W., Schoonjans, K., Derijard, B., Desvergne, B., Wahli, W., Chambon, P., Leibowitz, M. D., Colombel, J. F., and Auwerx, J. (2001) J. Exp. Med. 193 827–838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saubermann, L. J., Nakajima, A., Wada, K., Zhao, S., Terauchi, Y., Kadowaki, T., Aburatani, H., Matsuhashi, N., Nagai, R., and Blumberg, R. S. (2002) Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 8 330–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katayama, K., Wada, K., Nakajima, A., Mizuguchi, H., Hayakawa, T., Nakagawa, S., Kadowaki, T., Nagai, R., Kamisaki, Y., Blumberg, R. S., and Mayumi, T. (2003) Gastroenterology 124 1315–1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lytle, C., Tod, T. J., Vo, K. T., Lee, J. W., Atkinson, R. D., and Straus, D. S. (2005) Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 11 231–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schaefer, K. L., Denevich, S., Ma, C., Cooley, S. R., Nakajima, A., Wada, K., Schlezinger, J., Sherr, D., and Saubermann, L. J. (2005) Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 11 244–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewis, J. D., Lichtenstein, G. R., Deren, J. J., Sands, B. E., Hanauer, S. B., Katz, J. A., Lashner, B., Present, D. H., Chuai, S., Ellenberg, J. H., Nessel, L., and Wu, G. D. (2008) Gastroenterology 134 688–695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis, J. D., Lichtenstein, G. R., Stein, R. B., Deren, J. J., Judge, T. A., Fogt, F., Furth, E. E., Demissie, E. J., Hurd, L. B., Su, C. G., Keilbaugh, S. A., Lazar, M. A., and Wu, G. D. (2001) Am. J. Gastroenterol. 96 3323–3328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen, L., Bush, C. R., Necela, B. M., Su, W., Yanagisawa, M., Anastasiadis, P. Z., Fields, A. P., and Thompson, E. A. (2006) Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 251 17–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bush, C. R., Havens, J. M., Necela, B. M., Su, W., Chen, L., Yanagisawa, M., Anastasiadis, P. Z., Guerra, R., Luxon, B. A., and Thompson, E. A. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 23387–23401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phillips, D. J., and de Kretser, D. M. (1998) Front. Neuroendocrinol. 19 287–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Welt, C., Sidis, Y., Keutmann, H., and Schneyer, A. (2002) Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 227 724–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DePaolo, L. V., Bicsak, T. A., Erickson, G. F., Shimasaki, S., and Ling, N. (1991) Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 198 500–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pangas, S. A., and Woodruff, T. K. (2000) Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 11 309–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vale, W., Wiater, E., Gray, P., Harrison, C., Bilezikjian, L., and Choe, S. (2004) Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1038 142–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen, Y. G., Wang, Q., Lin, S. L., Chang, C. D., Chuang, J., and Ying, S. Y. (2006) Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 231 534–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones, K. L., Mansell, A., Patella, S., Scott, B. J., Hedger, M. P., de Kretser, D. M., and Phillips, D. J. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104 16239–16244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jones, K. L., de Kretser, D. M., Patella, S., and Phillips, D. J. (2004) Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 225 119–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Werner, S., and Alzheimer, C. (2006) Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 17 157–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Risbridger, G. P., Schmitt, J. F., and Robertson, D. M. (2001) Endocr. Rev. 22 836–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luisi, S., Florio, P., Reis, F. M., and Petraglia, F. (2001) Eur. J. Endocrinol. 145 225–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Phillips, D. J. (2000) BioEssays 22 689–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Phillips, D. J., and Woodruff, T. K. (2004) Growth Factors 22 13–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harrison, C. A., Gray, P. C., Vale, W. W., and Robertson, D. M. (2005) Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 16 73–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grusch, M., Drucker, C., Peter-Vorosmarty, B., Erlach, N., Lackner, A., Losert, A., Macheiner, D., Schneider, W. J., Hermann, M., Groome, N. P., Parzefall, W., Berger, W., Grasl-Kraupp, B., and Schulte-Hermann, R. (2006) J. Hepatol. 45 673–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsuchida, K., Nakatani, M., Uezumi, A., Murakami, T., and Cui, X. (2008) Endocr. J. 55 11–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jung, B. H., Beck, S. E., Cabral, J., Chau, E., Cabrera, B. L., Fiorino, A., Smith, E. J., Bocanegra, M., and Carethers, J. M. (2007) Gastroenterology 132 633–644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shen, Z. J., Chen, X. P., and Chen, Y. G. (2005) Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 88 336–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones, M. R., Wilson, S. G., Mullin, B. H., Mead, R., Watts, G. F., and Stuckey, B. G. (2007) Mol. Hum. Reprod. 13 237–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maeshima, A., Miya, M., Mishima, K., Yamashita, S., Kojima, I., and Nojima, Y. (2008) Endocr. J. 55 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hubner, G., Brauchle, M., Gregor, M., and Werner, S. (1997) Lab. Invest. 77 311–318 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hardy, C. L., O'Connor, A. E., Yao, J., Sebire, K., de Kretser, D. M., Rolland, J. M., Anderson, G. P., Phillips, D. J., and O'Hehir, R. E. (2006) Clin. Exp. Allergy 36 941–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ebert, S., Phillips, D. J., Jenzewski, P., Nau, R., O'Connor, A. E., and Michel, U. (2006) J. Neurol. Sci. 250 50–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stove, C., Vanrobaeys, F., Devreese, B., Van Beeumen, J., Mareel, M., and Bracke, M. (2004) Oncogene 23 5330–5339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paoni, N. F., Feldman, M. W., Gutierrez, L. S., Ploplis, V. A., and Castellino, F. J. (2003) Physiol. Genomics 15 228–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McPherson, S. J., Mellor, S. L., Wang, H., Evans, L. W., Groome, N. P., and Risbridger, G. P. (1999) Endocrinology 140 5303–5309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang, Q., Tabatabaei, S., Planz, B., Lin, C. W., and Sluss, P. M. (1999) J. Urol. 161 1378–1384 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thomas, T. Z., Wang, H., Niclasen, P., O'Bryan, M. K., Evans, L. W., Groome, N. P., Pedersen, J., and Risbridger, G. P. (1997) J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 82 3851–3858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rossmanith, W., Chabicovsky, M., Grasl-Kraupp, B., Peter, B., Schausberger, E., and Schulte-Hermann, R. (2002) Mol. Carcinog. 35 1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Harkonen, P., Torn, S., Kurkela, R., Porvari, K., Pulkka, A., Lindfors, A., Isomaa, V., and Vihko, P. (2003) J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 88 705–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dignass, A. U., Jung, S., Harder-d'Heureuse, J., and Wiedenmann, B. (2002) Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 37 936–943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sonoyama, K., Rutatip, S., and Kasai, T. (2000) Am. J. Physiol. 278 G89–G97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dohi, T., Ejima, C., Kato, R., Kawamura, Y. I., Kawashima, R., Mizutani, N., Tabuchi, Y., and Kojima, I. (2005) Gastroenterology 128 411–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lehmann, J. M., Moore, L. B., Smith-Oliver, T. A., Wilkison, W. O., Willson, T. M., and Kliewer, S. A. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270 12953–12956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kliewer, S. A., Umesono, K., Noonan, D. J., Heyman, R. A., and Evans, R. M. (1992) Nature 358 771–774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brasier, A. R., Jamaluddin, M., Casola, A., Duan, W., Shen, Q., and Garofalo, R. P. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 3551–3561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bilezikjian, L. M., Corrigan, A. Z., Blount, A. L., Chen, Y., and Vale, W. W. (2001) Endocrinology 142 1065–1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sadowski, I., and Ptashne, M. (1989) Nucleic Acids Res. 17 7539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Livak, K. J., and Schmittgen, T. D. (2001) Methods 25 402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Blay, J., and Brown, K. D. (1984) Cell Biol. Int. Rep. 8 551–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Drori, S., Girnun, G. D., Tou, L., Szwaya, J. D., Mueller, E., Xia, K., Shivdasani, R. A., and Spiegelman, B. M. (2005) Genes Dev. 19 362–375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen, L., Necela, B. M., Su, W., Yanagisawa, M., Anastasiadis, P. Z., Fields, A. P., and Thompson, E. A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 24575–24587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chawla, A., Barak, Y., Nagy, L., Liao, D., Tontonoz, P., and Evans, R. M. (2001) Nat. Med. 7 48–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moore, K. J., Fitzgerald, M. L., and Freeman, M. W. (2001) Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 12 519–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Crosby, M. B., Svenson, J. L., Zhang, J., Nicol, C. J., Gonzalez, F. J., and Gilkeson, G. S. (2005) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 312 69–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Subbaramaiah, K., Lin, D. T., Hart, J. C., and Dannenberg, A. J. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 12440–12448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hazra, S., Xiong, S., Wang, J., Rippe, R. A., Krishna, V., Chatterjee, K., and Tsukamoto, H. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 11392–11401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Coyle, A. T., and Kinsella, B. T. (2006) Biochem. Pharmacol. 71 1308–1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sugawara, A., Takeuchi, K., Uruno, A., Ikeda, Y., Arima, S., Kudo, M., Sato, K., Taniyama, Y., and Ito, S. (2001) Endocrinology 142 3125–3134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sugawara, A., Uruno, A., Kudo, M., Ikeda, Y., Sato, K., Taniyama, Y., Ito, S., and Takeuchi, K. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 9676–9683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Meissner, M., Stein, M., Urbich, C., Reisinger, K., Suske, G., Staels, B., Kaufmann, R., and Gille, J. (2004) Circ. Res. 94 324–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Han, S., Ritzenthaler, J. D., Rivera, H. N., and Roman, J. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. 289 L419–L428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chung, S. S., Choi, H. H., Cho, Y. M., Lee, H. K., and Park, K. S. (2006) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 348 253–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bartholin, L., Maguer-Satta, V., Hayette, S., Martel, S., Gadoux, M., Bertrand, S., Corbo, L., Lamadon, C., Morera, A. M., Magaud, J. P., and Rimokh, R. (2001) Oncogene 20 5409–5419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Miyanaga, K., and Shimasaki, S. (1993) Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 92 99–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bartholin, L., Maguer-Satta, V., Hayette, S., Martel, S., Gadoux, M., Corbo, L., Magaud, J. P., and Rimokh, R. (2002) Oncogene 21 2227–2235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Willert, J., Epping, M., Pollack, J. R., Brown, P. O., and Nusse, R. (2002) BMC Dev. Biol. 2 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.