Abstract

Cholesterol is an essential component of eukaryotic cells; at the same time, however, hyperaccumulation of cholesterol is harmful. Therefore, the ABCA1 gene, the product of which mediates secretion of cholesterol, is highly regulated at both the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. The transcription of ABCA1 is regulated by intracellular oxysterol concentration via the nuclear liver X receptor (LXR)/retinoid X receptor (RXR); once synthesized, ABCA1 protein turns over rapidly with a half-life of 1–2 h. Here, we show that the LXRβ/RXR complex binds directly to ABCA1 on the plasma membrane of macrophages and modulates cholesterol secretion. When cholesterol does not accumulate, ABCA1-LXRβ/RXR localizes on the plasma membrane, but is inert. When cholesterol accumulates, oxysterols bind to LXRβ, and the LXRβ/RXR complex dissociates from ABCA1, restoring ABCA1 activity and allowing apoA-I-dependent cholesterol secretion. LXRβ can exert an immediate post-translational response, as well as a rather slow transcriptional response, to changes in cellular cholesterol accumulation. Thus, we provide the first demonstration that protein-protein interaction suppresses ABCA1 function. Furthermore, we show that LXRβ is involved in both the transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of the ABCA1 transporter.

Maintenance of cellular cholesterol homeostasis is important for normal human physiology. Disruption of cellular cholesterol homeostasis leads to a variety of pathological conditions, including cardiovascular disease (1). ABCA1 (ATP-binding cassette protein A1), one of the key proteins in cholesterol homeostasis, mediates secretion of cellular free cholesterol and phospholipids to an extracellular acceptor in the plasma, apoA-I, to form high density lipoprotein (HDL)3 (2, 3). HDL formation is the only known pathway that can eliminate excess cholesterol from peripheral cells. Defects in ABCA1 cause Tangier disease (4–6), in which patients have a near absence of circulating HDL, prominent cholesterol ester accumulation in tissue macrophages, and premature atherosclerotic vascular disease (1, 7).

ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux is highly regulated at both the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. When cholesterol accumulates in cells, intracellular concentrations of oxysterols increase; subsequently, the liver X receptor (LXR), activated via binding of oxysterols, stimulates the transcription of ABCA1 (8–10). ABCA1 protein eliminates excess cellular cholesterol and turns over rapidly with a half-life of 1–2 h (11–15). Several proteins, including apoA-I, α1-syntrophin, and β1-syntrophin, have been reported to interact with ABCA1 and reduce the rate of ABCA1 protein degradation (13–16). Syntrophins play critical roles in regulating the apoA-I-dependent cholesterol efflux (and thus in lipid homeostasis) by suppressing protein degradation in brain (14) and liver (15). Because cholesterol is an essential component of cells, however, excessive elimination of cholesterol could result in cell death. Consequently, the ability to rapidly degrade ABCA1, to prevent cholesterol efflux, is also important.

We performed a yeast two-hybrid screen to search for additional proteins associated with the C-terminal region of ABCA1. The screen identified a nuclear receptor, LXRβ, as a candidate that associates with the C-terminal 120 amino acids of human ABCA1. In WI-38 and THP-1 cells, endogenous LXRβ interacts with ABCA1 under conditions in which cholesterol does not accumulate, i.e. when cholesterol is not in excess. LXRβ suppresses ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux and thereby blocks HDL formation. This study is the first to show that protein-protein interaction suppresses the function of ABCA1 and that LXRβ is involved not only in the transcriptional regulation but also in the post-translational regulation of ABCA1.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids—cDNAs encoding human LXRα (NCBI Database accession number NM_005693) and human LXRβ (accession number NM_007121) were inserted into the p401 vector or pGEX-4T1 (Amersham Biosciences).

Antibodies—The linker region (amino acids 1134–1345) of human ABCA1 was fused with glutathione S-transferase, and the fusion protein was expressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21. The fusion protein was purified and used to raise rabbit polyclonal antibodies. Anti-LXRα (PP-K8607-00), anti-LXRβ (PP-K8917-00), and anti-retinoid X receptor (RXR; PP-K8508-00) monoclonal antibodies were purchased from Perseus Proteomics.

Cell Culture and Transfection—THP-1 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma) containing 10% fetal bovine serum under a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air at 37 °C. Differentiation into macrophages was achieved by exposing cells to 50 ng/ml phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate for 72 h. Macrophages were incubated in the presence of 5 μm retinoic acid for 24 h to induce the expression of ABCA1. HEK293 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum. Cells in 100-mm culture dishes were transfected with 8 μg of DNA using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Membrane Preparation and Immunoprecipitation—HEK293 cells were cultured on 100-mm dishes and transiently transfected with 6 μg of ABCA1 and 2 μg of LXRα or LXRβ. Cells were lysed by nitrogen cavitation in isotonic buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 at 4 °C, 1 mm EDTA, and 250 mm sucrose) containing protease inhibitors (100 μg/ml p-amidinophenyl-methanesulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, and 2 μg/ml aprotinin). After the nucleus was removed by centrifugation (2800 × g), membranes were prepared by centrifugation (20,000 × g) and lysed with 1% Nonidet P-40. Proteins from the membrane lysate (300 μg) were incubated with 2.5 μg of anti-LXRα, anti-LXRβ, or rabbit anti-ABCA1 polyclonal antibody (described above) at 4 °C for 60 min. The protein complexes containing each antibody were precipitated with protein G-Sepharose 4B (Sigma). ABCA1 and vinculin were detected with anti-ABCA1 antibody KM3110 (14) and anti-human vinculin antibody (hVIN-1, Sigma), respectively. Western blots were analyzed using a Fujifilm LAS-3000 imaging system.

Biotinylation of Cell-surface Proteins—HEK293 cells were cotransfected with ABCA1 and LXRs. At 28 h after transfection, cells were biotinylated as reported previously (17, 18).

Cellular Lipid Release Assay—HEK293 cells were subcultured in 6-cm dishes at a density of 5 × 105 cells in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal bovine serum. After 18 h of incubation, cells were transfected with ABCA1 and FLAG-tagged LXRs using Lipofectamine. Cells were washed 28 h after transfection with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 0.02% bovine serum albumin and then incubated with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 0.02% bovine serum albumin and 10 μg/ml apoA-I with or without 100 nm TO901317 for 2 h at 37 °C. The lipid content of the medium was determined as described previously (19). THP-1 cells were subcultured in 10-cm dishes at a density of 1 × 107 cells in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and prepared as described above. Cells were then washed with RPMI 1640 medium containing 0.02% bovine serum albumin and incubated in RPMI 1640 medium containing 0.02% bovine serum albumin and 10 μg/ml apoA-I with or without 100 nm TO901317 for 2 h at 37 °C.

Immunostaining—Immunostaining was performed as described previously (19).

Preparation of Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Fractions—Cells were lysed with phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% Tween 20 and protease inhibitors at 4 °C for 15 min. The nucleus was precipitated by centrifugation (2800 × g), and the supernatant were collected as the cytosolic fraction. The pellet was disrupted in the presence of 1% SDS using a sonicator.

RNA Interference—Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) specific for LXRα (siNR1H3, GAGGCUGCAGCACACAUAUGUGGAA (sense)), LXRβ (siNR1H3, GCUACAACCACGAGACAGAGUGUAU (sense)), and a scrambled control were obtained from Invitrogen. WI-38 cells were transfected for 72 h with 120 nm siRNAs using RNAiMAX (Invitrogen).

RNA Extraction and Quantitative Reverse Transcription-PCR—RNA was extracted with an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and cDNA was generated using random primers (Applied Biosystems) and a high capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) in the presence of an RNase inhibitor. Each RNA sample was amplified in triplicate with primers for ABCA1 and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, as a housekeeping marker, on a StepOne real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) using TaqMan gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems). The probes used were as follows: human ABCA1, 5′-ACCCAATCCCAGACACGCCCTGCCA-3′; and human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, 5′-TTGGGCGCCTGGTCACCAGGGCTGC-3′.

Statistical Analysis—The statistical significance of differences between mean values was analyzed using the unpaired t test. Multiple comparisons were performed using Dunnett's test following analysis of variance. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. Unless indicated otherwise, results are given as means ± S.E. (n = 3).

RESULTS

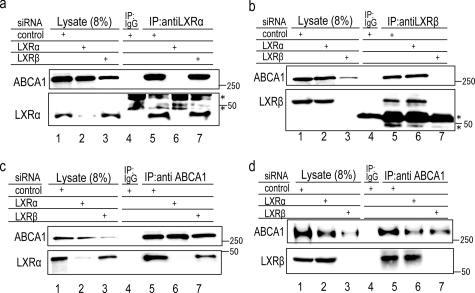

ABCA1 Interacts with Nuclear LXRα and LXRβ—Using yeast two-hybrid screening, we searched for proteins that are associated with the C-terminal 120 amino acids of human ABCA1. We identified a nuclear receptor, LXRβ, as a candidate and then examined the interaction between ABCA1 and LXRs by co-immunoprecipitation (Fig. 1). ABCA1 and LXRα or LXRβ were transiently expressed in HEK293 cells, and a membrane fraction was prepared as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Under these conditions, LXRα or LXRβ was detected in the lysate of the membrane fraction (Fig. 1, lanes 1 and 5). When either LXRα or LXRβ was precipitated with an appropriate antibody, ABCA1 was co-precipitated (lanes 3 and 7). Conversely, LXRs were also co-precipitated with ABCA1 when we used an antibody against ABCA1 (data not shown). The addition of an LXR agonist, TO901317, to the lysate impaired the co-precipitation of ABCA1 with LXRs by the anti-LXR antibodies, although the immunoprecipitation of LXRs themselves was not affected (lanes 4 and 8), suggesting that conformational changes caused by agonists impair the interaction. To confirm that this interaction is direct, the C-terminal 298 amino acids of ABCA1 fused with maltose-binding protein and LXRα or LXRβ fused with glutathione S-transferase were purified from E. coli. The maltose-binding protein-fused C-terminal 298 amino acids of ABCA1 were pulled down by glutathione S-transferase-fused LXRs (supplemental Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Interaction of LXRα and LXRβ with ABCA1. HEK293 cells were cotransfected with human ABCA1 and LXRα or LXRβ. At 24 h after transfection, a lysate of the membrane fraction was prepared. LXRα or LXRβ was immunoprecipitated (IP) with control mouse IgG (control) or anti-LXRα or anti-LXRβ monoclonal antibody in the absence (lanes 2, 3, 6, and 7) or presence (lanes 4 and 8) of 100 nm TO901317 (TO). Cell lysates (10%) (lanes 1 and 5) and immunocomplexes were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-ABCA1 monoclonal antibody KM3110 (14) or with anti-LXRα or anti-LXRβ monoclonal antibody. The asterisks indicate the IgG heavy chain.

Because the addition of TO901317 to the lysate impaired the co-precipitation, it was not likely that the co-precipitation was due merely to the aggregation of these proteins. However, it was still possible that the localization of LXR in the membrane fraction and the co-precipitation were due to the overexpression of these proteins in the heterologous expression system.

Interaction of Endogenous LXRs with ABCA1 in WI-38 Cells—Therefore, we next examined whether the endogenously expressed LXRs interact with ABCA1. WI-38 human lung fibroblasts were incubated with retinoic acid for 24 h to induce the expression of ABCA1 and LXRs. LXRα and LXRβ were detected in the lysate of the membrane fraction of WI-38 cells (Fig. 2, a and b, lane 1). When LXRα or LXRβ was precipitated with a suitable antibody, ABCA1 was co-precipitated (lane 5). Following knockdown of each LXR with siRNA, the corresponding band (LXRα or LXRβ) disappeared from the lysate (lanes 2 and 3), as did the band corresponding to co-precipitated ABCA1 (lanes 6 and 7). Both LXRα and LXRβ co-precipitated with ABCA1 by the antibody against ABCA1 (Fig. 2, c and d, lane 5). Neither LXRα nor LXRβ was co-precipitated when they were knocked down with siRNA (lanes 6 and 7). These results suggest that the antibodies used in this study against LXRα and LXRβ indeed react with endogenous LXRα and LXRβ, respectively, and that endogenous LXRα and LXRβ interact with ABCA1.

FIGURE 2.

Interaction of endogenous LXRs with ABCA1 in WI-38 cells. WI-38 cells were transfected with control siRNA or siRNA against LXRα or LXRβ and incubated with retinoic acid (5 μm) for 24 h, at which time a lysate of the membrane fraction was prepared. LXRα (a), LXRβ (b), or ABCA1 (c and d) was immunoprecipitated (IP) with control mouse IgG, anti-LXRα or anti-LXRβ monoclonal antibody, or anti-ABCA1 polyclonal antibody, respectively. Three siRNAs for LXRα or LXRβ were examined and found to show similar effects (data not shown). The asterisks indicate the IgG heavy chain.

The expression of ABCA1 was greatly reduced when LXRβ was knocked down with siRNA (Fig. 2, a–d, lane 3), but not when LXRα was knocked down (lane 2). These results suggest that LXRβ plays a major role in the expression of ABCA1 in WI-38 fibroblasts under these conditions. This is consistent with the report that the expression of LXRβ does not change during cholesterol accumulation and that LXRβ plays a role in resting macrophages, whereas LXRα plays a prominent role in macrophages in the context of cellular cholesterol loading (20, 21).

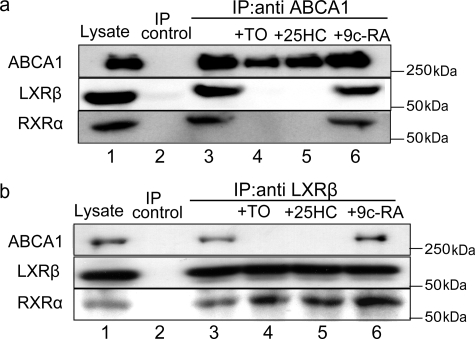

Interaction of LXRβ with ABCA1 in THP-1 Cells—To confirm further that endogenous LXRs interact with ABCA1, THP-1 human monocytic leukemia cells were induced to differentiate into macrophage-like cells by treatment with phorbol ester, and a membrane fraction was prepared. Because LXR agonists cause the dissociation of LXRs from ABCA1 (Fig. 1), THP-1 cells were not incubated with LXR agonists but with a minimum dose (10 nm) of retinoic acid. Under these conditions, LXRβ was detected in the lysate of the membrane fraction (Fig. 3, a and b, lane 1), but LXRα was not (data not shown). When ABCA1 was immunoprecipitated, LXRβ was co-precipitated (Fig. 3a, lane 3) and vice versa (Fig. 3b, lane 3). RXR was also co-precipitated with ABCA1 and LXRβ (Fig. 3, a and b, lane 3). The co-precipitation of LXRβ and RXR with ABCA1 was impaired when an LXR agonist, TO901317 (lane 4) or 25-hydroxycholesterol (lane 5), was added to the lysate; in contrast, the addition of an RXR agonist, retinoic acid, did not affect the co-precipitation (lane 6). These results suggest that LXRβ/RXR interacts with ABCA1 in THP-1 cells under conditions in which cholesterol does not accumulate in the cells and that the heterodimer dissociates from ABCA1 when LXR agonists accumulate.

FIGURE 3.

Interaction of LXRβ with ABCA1 in THP-1 cells. Differentiated THP-1 cells were incubated with retinoic acid (10 nm) for 24 h, and a membrane fraction was prepared. ABCA1 (a) or LXRβ (b) was immunoprecipitated (IP) with control mouse IgG (control), anti-ABCA1 polyclonal antibody, or anti-LXRβ monoclonal antibody in the absence or presence of 100 nm TO901317 (TO), 10 μm 25-hydroxycholesterol (25HC), or 5 μm 9-cis-retinoic acid (9c-RA). Cell lysate (10%) and immunocomplexes were subjected to immunoblotting.

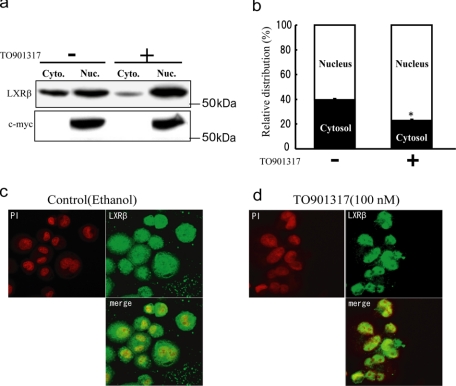

Subcellular Localization of LXRβ in THP-1 Cells—LXRs are thought to be located in the nucleus even in the absence of agonists. We analyzed the subcellular distribution of LXRβ in THP-1 cells in the absence of exogenously added agonists (Fig. 4, a and b). Cells were lysed with 1% Tween 20 and fractionated as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Under the experimental conditions, ∼40% of LXRβ was recovered in the cytosolic fraction, although no c-Myc protein was detected in this fraction. When TO901317 was added to the cells, only ∼20% of LXRβ was recovered from the cytosolic fraction (Fig. 4, a and b).

FIGURE 4.

Subcellular localization of LXRβ in THP-1 cells. Differentiated THP-1 cells were treated with or without 100 nm TO901317 for 2 h. Cells were lysed with 1% Tween 20, and nuclear (Nuc.) and cytoplasmic (Cyto.) fractions were prepared. a, LXRβ and c-Myc were detected by anti-LXRβ monoclonal antibody or anti-RXR antibody. b, the Western blot was analyzed using the LAS-3000 imaging system. Error bars represent the means ± S.E. of three measurements. *, p < 0.05 (significantly different from the control). c and d, differentiated THP-1 cells were treated with or without 100 nm TO901317 for 2 h. Cells were fixed and immunostained using anti-LXRβ monoclonal antibody. The nucleus was visualized with propidium iodide (PI).

Next, the subcellular distribution of LXRβ in THP-1 cells was observed under an immunofluorescence microscope. In the absence of added agonists, a significant amount of LXRβ was observed outside of the nucleus (Fig. 4c). When TO901317 was added, most of the LXRβ translocated into the nucleus (Fig. 4d). When LXRβ was knocked down by siRNA, no signal for LXRβ was observed, confirming the specificity of the antibody (supplemental Fig. 2). These results strongly suggest that a significant amount of LXRβ exists outside of the nucleus under conditions in which cholesterol does not accumulate in the cell but that the protein translocates into the nucleus when LXR ligands accumulate. Because LXRα is abundantly expressed in tissues important for cholesterol homeostasis, such as liver, kidney, spleen, intestine, and macrophages, and because LXRα plays a major role in reverse cholesterol transport from cholesterol-loaded cells, the dynamics of LXRβ cytosolic localization might have been overlooked in previous studies.

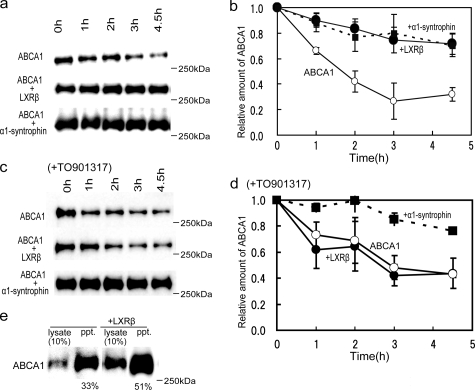

LXRβ Modulates Turnover of ABCA1 and Increases Surface Expression—While investigating the consequence of ABCA1-LXRβ interaction, we noticed that the amount of ABCA1 was significantly increased when it was coexpressed with LXRβ (data not shown). We expected the interaction with LXRβ to retard the degradation of ABCA1. We measured the half-life of ABCA1, obtaining a value 1.5–2 h (Fig. 5, a–d), consistent with previous reports (13, 14), when ABCA1 was expressed alone in HEK293 cells. When ABCA1 was coexpressed with LXRβ (Fig. 5, a and b), however, its degradation was retarded, and its half-life became longer than 5 h as α1-syntrophin was coexpressed. When TO901317, which causes dissociation of the ABCA1-LXRβ/RXR complex, was added, the coexpression of LXRβ did not retard the degradation of ABCA1, whereas the coexpression of α1-syntrophin still did (Fig. 5, c and d).

FIGURE 5.

Effects of LXRβ on turnover and surface expression of ABCA1. HEK293 cells were cotransfected with ABCA1 and vector (mock transfection; ○), LXRβ (•), or α1-syntrophin (▪). a and b, at 48 h after transfection, 100 μg/ml cycloheximide was added to block protein synthesis (14). After incubation in the absence (a and b) or presence (c and d) of TO901317, cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting with antibody KM3110. c and d, the relative amount of ABCA1 is shown. Values are expressed as the -fold increase relative to the amount of ABCA1 just before cycloheximide was added. Values represent the means ± S.E. of three measurements. e, the biotinylation of ABCA1 is shown. HEK293 cells transfected with ABCA1 or with ABCA1 and LXRβ were treated with sulfo-N-hydroxysuccinimidobiotin. Biotinylated surface proteins were precipitated from 100 μg of cell lysate with avidin-agarose. ABCA1 was detected with antibody KM3110.

Next, we examined the surface expression of ABCA1 by conducting biotinylation experiments (Fig. 5e). When ABCA1 was transiently coexpressed with LXRβ in HEK293 cells, the amount of ABCA1 in the lysate increased, and 51 ± 7.0% of ABCA1 was precipitated with avidin-agarose compared with 33 ± 3.4% when expressed alone. These results suggest that interaction with LXRβ not only retards the degradation of ABCA1 but also increases the surface expression of ABCA1.

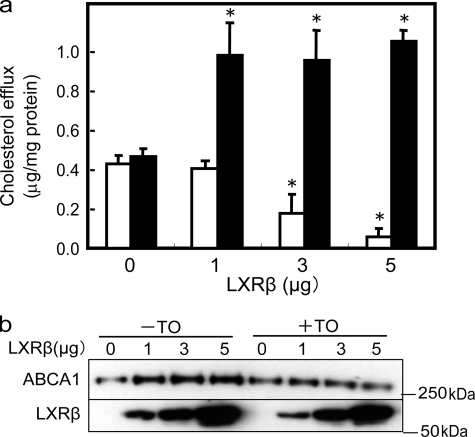

Interaction with LXRβ Suppresses ABCA1-mediated Cholesterol Efflux—To analyze the functional consequences of the formation of ABCA1-LXRβ/RXR, apoA-I-dependent cholesterol efflux was examined in HEK293 cells transiently cotransfected with ABCA1 and LXRβ (Fig. 6a, open bars). ApoA-I-dependent efflux was reduced with increasing amounts of transfected LXRβ DNA and with increased expression of LXRβ, even though the amount of ABCA1 was increased compared with that without cotransfection with LXRβ (Fig. 6, a and b). With the addition of TO901317, which impairs ABCA1-LXR interaction, apoA-I-dependent cholesterol efflux was greatly enhanced (>100%) when LXRβ was cotransfected (Fig. 6a, filled bars). TO901317 neither induced endogenous ABCA1 expression (data not shown) nor affected apoA-I-dependent cholesterol efflux when LXRβ was not cotransfected (Fig. 6a). Western blot analysis of ABCA1 after the efflux experiment showed that, when LXRβ (5 μg) was cotransfected, treatment with TO901317 for 2 h reduced the amount of ABCA1 to the level obtained without LXR expression (Fig. 6b).

FIGURE 6.

Effects of coexpression with LXRβ and TO901317 on apoA-I-dependent cholesterol efflux. The effects of coexpression with LXRβ in HEK293 cells are shown. a, HEK293 cells were cotransfected with 3 μg of ABCA1 and 0, 1, 3, or 5 μg of LXRβ. Fresh medium was added at 28 h after transfection, and apoA-I-dependent cholesterol efflux during a 2-h incubation in the presence (filled bars) or absence (open bars) of 100 nm TO901317 (TO) was measured (19). b, cell lysates were prepared just after the cholesterol efflux assay and subjected to immunoblotting with antibody KM3110 and anti-LXRβ monoclonal antibody.

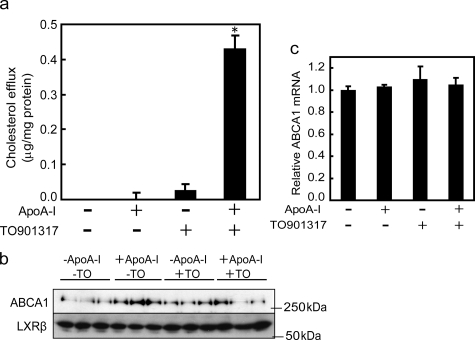

ABCA1-LXR Interaction Modulates ApoA-I-dependent Cholesterol Efflux from THP-1 Cells—The above results suggested that ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux might be suppressed by the interaction with the LXRβ/RXR heterodimer when cholesterol does not accumulate in cells. Therefore, we carefully analyzed the apoA-I-dependent efflux of cholesterol from THP-1 cells. When differentiated THP-1 cells were incubated with a minimum dose (10 nm) of retinoic acid, no apoA-I-dependent efflux was detected (Fig. 7a), although a significant amount of ABCA1 was expressed (Fig. 7b). However, when 100 nm TO901317 was added to the medium for 2 h, apoA-I-dependent cholesterol efflux was clearly observed. Under these conditions, no increase in ABCA1 mRNA (Fig. 7c) or ABCA1 protein (Fig. 7b) was observed. Even after a 4-h incubation with TO901317, only a slight increase in ABCA1 mRNA and protein (1.34 ± 0.13-fold and 1.05 ± 0.04-fold, respectively) was observed. After a 6-h incubation, mRNA and protein were markedly increased (2.33 ± 0.21-fold and 1.72 ± 0.04-fold, respectively) (data not shown).

FIGURE 7.

Effect of TO901317 on apoA-I-dependent cholesterol efflux from THP-1 cells. a, ABCA1 was induced by 10 nm retinoic acid in differentiated THP-1 cells. ApoA-I-dependent cholesterol efflux during 2 h of incubation in the presence or absence of 100 nm TO901317 (TO) was measured. b, cell lysates were prepared just after the cholesterol efflux assay and subjected to immunoblotting with antibody KM3110. c, the relative amount of ABCA1 mRNA just after the cholesterol efflux assay was measured by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR. *, p < 0.05 (significantly different from the control).

DISCUSSION

When cholesterol accumulates in cells, intracellular concentrations of oxysterols increase, and LXR, activated via the binding of oxysterols, stimulates the gene expression of ABCA1, ABCG1, and other proteins that remove cholesterol from cells. The synthesized ABCA1 protein is distributed on the plasma membrane as well as in intracellular compartments and turns over rapidly with a half-life of 1–2 h (11–13). Therefore, after excess cholesterol is eliminated, ABCA1 would be degraded rapidly, and cells would have little ABCA1 on the plasma membrane. Because the transcription, splicing, translation, and maturation of ABCA1, at >2000 amino acid residues, takes several hours after transcriptional activation, cells would not be able to cope with an acute accumulation of cholesterol for several hours before the vigorous transcriptional activation of ABCA1 via the LXRα autoregulatory loop.

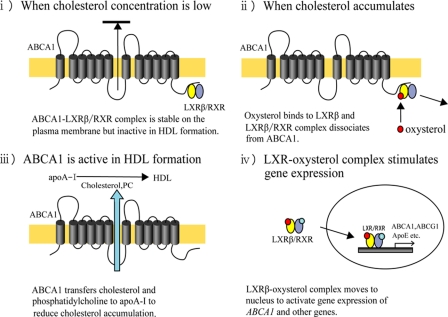

We propose a novel regulatory mechanism of ABCA1 based on the results presented in this study as follows (Fig. 8). (i) When the intracellular concentration of oxysterols is low, the LXRβ/RXR complex binds to ABCA1, and the ABCA1-LXRβ/RXR complex distributes on the plasma membrane but is inert in terms of cholesterol efflux, which prevents the excessive elimination of cholesterol from cells. (ii) When cholesterol accumulates and the intracellular concentration of oxysterols increases, oxysterols bind to LXRβ, and the LXRβ/RXR complex dissociates from ABCA1. (iii) Once free from LXRβ/RXR, ABCA1 is now active in the formation of HDL and decreases the local cholesterol concentration immediately. (iv) Upon binding oxysterols in the cytosol, LXRβ/RXR is translocated to the nucleus and activates the transcription of ABCA1 and other genes. Consequently, LXRβ can exert an immediate post-translational response, as well as a rather slow transcriptional response, to changes in cellular cholesterol accumulation to maintain cholesterol homeostasis. This novel mechanism would be important for macrophages because macrophages must cope with rapid increases in intracellular cholesterol when they phagocytose apoptotic cells.

FIGURE 8.

Novel regulatory mechanism for ABCA1 by LXRβ. (i) When cholesterol concentration is low, the ABCA1-LXRβ/RXR complex is stable on the plasma membrane but inactive in HDL formation. (ii) When cholesterol accumulates, oxysterol binds to LXRβ, and the LXRβ/RXR complex dissociates from ABCA1. (iii) ABCA1 transfers cholesterol and phosphatidylcholine (PC) to apoA-I to reduce cholesterol accumulation. (iv) The LXRβ-oxysterol complex moves to the nucleus to activate the expression of ABCA1 and other genes.

α1-Syntrophin (14) and β1-syntrophin (15) are involved in the post-translational regulation of ABCA1. Both proteins interact directly with ABCA1 via the C-terminal three amino acids SYV (a PDZ (PSD95-Discs large-ZO1) protein-binding motif). These interactions retard the degradation of ABCA1, increase the surface expression of ABCA1, and consequently increase the apoA-I-mediated release of cholesterol (14). The mechanisms of ABCA1 degradation and of its retardation by syntrophins have not yet been clarified. Interaction with LXRβ also retards the degradation of ABCA1 and increases the surface expression of ABCA1. In contrast to the interaction with syntrophins, this interaction suppresses the formation of HDL; hence, the mechanism of the LXRβ interaction is likely different from that of the syntrophin interaction. We found that the site of interaction of ABCA1 with LXRβ is different from that with syntrophins. The replacement of Leu2247 of ABCA1 with alanine abolished the co-precipitation with LXRβ (supplemental Fig. 3a). The coexpression of LXRβ did not retard the degradation of ABCA1(L2247A), whereas the coexpression of α1-syntrophin retarded the degradation of ABCA1(L2247A) (supplemental Fig. 3, b and c). These results suggest that the amino acid substitution L2247A does not alter total protein conformation but rather specifically affects the interaction with LXRβ. ABCA1(L2247A) showed significant apoA-I-dependent cholesterol efflux, and the addition of TO901317 did not affect it even when LXRβ was coexpressed (supplemental Fig. 3d). Leu2247 is in a sequence (2247LTSFL2251) that resembles the sequences (φXXφφ) (22) of co-activators and co-repressors interacting with nuclear receptors. Therefore, we speculate that the co-activator/co-repressor interaction site of LXRβ could be involved in the interaction with ABCA1.

These results suggest that LXRβ regulates the efflux of cholesterol not only by modulating ABCA1 gene expression as nuclear receptors but also by directly modulating the efflux activity of ABCA1. This study is the first to show that protein-protein interaction suppresses ABCA1 function. This is also the first example of mutual regulation between a nuclear receptor and a membrane protein that is also an end product of transcriptional regulation by the same nuclear receptor. This unusual situation possibly came about through the co-evolution of these proteins, resulting in a sophisticated network devoted to the maintenance of homeostasis.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by a grant-in-aid for scientific research (S) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan, by the Program for Promotion of Fundamental Studies in Health Sciences of the National Institute of Biomedical Innovation, and by the World Premier International Research Center Initiative, Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–3.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: HDL, high density lipoprotein; LXR, liver X receptor; RXR, retinoid X receptor; siRNA, small interfering RNA.

References

- 1.Oram, J. F., and Vaughan, A. M. (2006) Circ. Res. 99 1031-1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanaka, A. R., Abe-Dohmae, S., Ohnishi, T., Aoki, R., Morinaga, G., Okuhira, K. I., Ikeda, Y., Kano, F., Matsuo, M., Kioka, N., Amachi, T., Murata, M., Yokoyama, S., and Ueda, K. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 8815-8819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yokoyama, S. (2000) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1529 231-244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooks-Wilson, A., Marcil, M., Clee, S., Zhang, L., Roomp, K., van Dam, M., Yu, L., Brewer, C., Collins, J., Molhuizen, H., Loubser, O., Ouelette, B., Fichter, K., Ashbourne-Excoffon, K., Sensen, C., Scherer, S., Mott, S., Denis, M., Martindale, D., Frohlich, J., Morgan, K., Koop, B., Pimstone, S., Kastelein, J., and Hayden, M. (1999) Nat. Genet. 22 336-345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodzioch, M., Orso, E., Klucken, J., Langmann, T., Bottcher, A., Diederich, W., Drobnik, W., Barlage, S., Buchler, C., Porsch-Ozcurumez, M., Kaminski, W., Hahmann, H., Oette, K., Rothe, G., Aslanidis, C., Lackner, K., and Schmitz, G. (1999) Nat. Genet. 22 347-351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rust, S., Rosier, M., Funke, H., Real, J., Amoura, Z., Piette, J., Deleuze, J., Brewer, H., Duverger, N., Denefle, P., and Assmann, G. (1999) Nat. Genet. 22 352-355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singaraja, R. R., Brunham, L. R., Visscher, H., Kastelein, J. J., and Hayden, M. R. (2003) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 23 1322-1332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Venkateswaran, A., Laffitte, B. A., Joseph, S. B., Mak, P. A., Wilpitz, D. C., Edwards, P. A., and Tontonoz, P. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97 12097-12102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Repa, J. J., Turley, S. D., Lobaccaro, J.-M. A., Medina, J., Li, L., Lustig, K., Shan, B., Heyman, R. A., Dietschy, J. M., and Mangelsdorf, D. J. (2000) Science 289 1524-1529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costet, P., Luo, Y., Wang, N., and Tall, A. R. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 28240-28245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang, Y., and Oram, J. F. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 5692-5697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arakawa, R., and Yokoyama, S. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 22426-22429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang, N., Chen, W., Linsel-Nitschke, P., Martinez, L. O., Agerholm-Larsen, B., Silver, D. L., and Tall, A. R. (2003) J. Clin. Investig. 111 99-107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Munehira, Y., Ohnishi, T., Kawamoto, S., Furuya, A., Shitara, K., Imamura, M., Yokota, T., Takeda, S., Amachi, T., Matsuo, M., Kioka, N., and Ueda, K. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 15091-15095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okuhira, K., Fitzgerald, M. L., Sarracino, D. A., Manning, J. J., Bell, S. A., Goss, J. L., and Freeman, M. W. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 39653-39664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arakawa, R., Hayashi, M., Remaley, A. T., Brewer, B. H., Yamauchi, Y., and Yokoyama, S. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 6217-6220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaneko, E., Matsuda, M., Yamada, Y., Tachibana, Y., Shimomura, I., and Makishima, M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 36091-36098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Makishima, M., Lu, T. T., Xie, W., Whitfield, G. K., Domoto, H., Evans, R. M., Haussler, M. R., and Mangelsdorf, D. J. (2002) Science 296 1313-1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abe-Dohmae, S., Suzuki, S., Wada, Y., Aburatani, H., Vance, D. E., and Yokoyama, S. (2000) Biochemistry 39 11092-11099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whitney, K. D., Watson, M. A., Goodwin, B., Galardi, C. M., Maglich, J. M., Wilson, J. G., Willson, T. M., Collins, J. L., and Kliewer, S. A. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 43509-43515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laffitte, B. A., Joseph, S. B., Walczak, R., Pei, L., Wilpitz, D. C., Collins, J. L., and Tontonoz, P. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21 7558-7568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metivier, R., Stark, A., Flouriot, G., Hubner, M. R., Brand, H., Penot, G., Manu, D., Denger, S., Reid, G., Kos, M., Russell, R. B., Kah, O., Pakdel, F., and Gannon, F. (2002) Mol. Cell 10 1019-1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.