Abstract

The dynamic expression of voltage-gated potassium channels (Kvs) at the cell surface is a fundamental factor controlling membrane excitability. In exploring possible mechanisms controlling Kv surface expression, we identified a region in the extracellular linker between the first and second of the six (S1-S6) transmembrane-spanning domains of the Kv1.4 channel, which we hypothesized to be critical for its biogenesis. Using immunofluorescence microscopy, flow cytometry, patch clamp electrophysiology, and mutagenesis, we identified a single threonine residue at position 330 within the Kv1.4 S1-S2 linker that is absolutely required for cell surface expression. Mutation of Thr-330 to an alanine, aspartate, or lysine prevented surface expression. However, surface expression occurred upon co-expression of mutant and wild type Kv1.4 subunits or mutation of Thr-330 to a serine. Mutation of the corresponding residue (Thr-211) in Kv3.1 to alanine also caused intracellular retention, suggesting that the conserved threonine plays a generalized role in surface expression. In support of this idea, sequence comparisons showed conservation of the critical threonine in all Kv families and in organisms across the evolutionary spectrum. Based upon the Kv1.2 crystal structure, further mutagenesis, and the partial restoration of surface expression in an electrostatic T330K bridging mutant, we suggest that Thr-330 hydrogen bonds to equally conserved outer pore residues, which may include a glutamate at position 502 that is also critical for surface expression. We propose that Thr-330 serves to interlock the voltage-sensing and gating domains of adjacent monomers, thereby yielding a structure competent for the surface expression of functional tetramers.

Voltage-gated potassium (Kv) channels (1) play a pivotal role in determining the excitability of tissues ranging from heart and skeletal muscle to brain (1, 2). By defining the resting membrane potential and the size, shape, and frequency of action potentials, such channels ultimately control phenomena such as transmitter release and muscle contractility (1-3), whereas their malfunction plays a role in diverse disease states (3, 4). Not surprisingly, Kv channels have received much attention both as pharmacological targets and as vehicles with which to better understand ion channel biophysics (1-6). In mammals, Kv channels comprise 12 subfamilies (Kv1-12) (1), of which Kvs 1-4 form functional homo- or heterotetramers and Kvs 5-12 are assembled as heteromers (1, 5). Each Kv monomer has a structure composed of intracellular amino and carboxyl termini and six transmembrane-spanning domains (S1-S6), of which S1-S4 form a voltage-sensing domain, and S5-S6 and a reentrant pore loop region in between contain the channel-gating machinery (6-8) (Fig. 1).

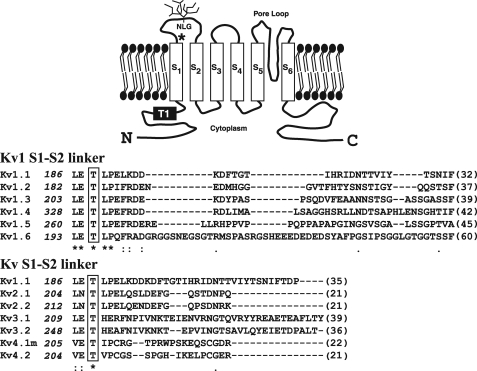

FIGURE 1.

Identification of conserved residues in the S1-S2 linker of the Kv family. Upper panel, schematic diagram of the predicted membrane topology for a Kv1 family subunit, including the N-linked glycosylation (NLG) site found in the Kv1.4 S1-S2 linker and the T1 domain required for tetramerization. The asterisk denotes conserved threonine (residue 330 in Kv1.4). Lower panel, ClustalW sequence alignment of the S1-S2 extracellular linker of the rat Kv1 family and further alignment of other Kv families (beginning from the proposed last residue (leucine (L) or equivalent, numbered at left) emerging from the S1 transmembrane domain. Conserved residues are shown by asterisks with the conserved threonine boxed. Numbers in parentheses indicate the lengths of each S1-S2 linker. All sequences are from rat except Kv4.1, which is from mouse. (Evolutionary conservation of the S1-S2 linker region is shown in Fig. 9).

Assembly of Kv channels occurs at the level of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)2 and proceeds via tetramerization of the T1 domains (9), located in the cytoplasmic amino terminus of each subunit (Fig. 1) (9, 10), and additional poorly defined intrasubunit contacts (11). Once assembled, Kv tetramers are trafficked to the cell surface via the classical secretory pathway (12). In transit, Kvs can associate with accessory proteins and experience maturation steps, notably glycosylation, which modulate their surface expression and kinetics (13, 14). In common with other membrane proteins, forward trafficking of Kvs is primarily regulated at the level of the ER using mechanisms that recognize specific trafficking determinants, the best characterized of which are an ER retention motif found in the ER luminal/extracellular pore mouth of Kv1.1, 1.2, and 1.6 channels (14) andaVXXSL motif in the carboxyl terminus (15).

Extensive structure-function studies, including solution of the crystal structure of much of the Kv1.2 channel (6, 8) in its open state, have ascribed biophysical, modulatory, assembly, and trafficking functions to the cytoplasmic (S2-S3, S4-S5 linker or amino and carboxyl termini) and extracellular (S3-S4 and S5-S6 linker pore mouth) domains (2, 6, 14-16). The function of the S1-S2 extracellular linker, however, is less clear. Mutational studies suggest the S1-S2 loop is not a major determinant of channel conductance or kinetics (6, 17). Although, in many cases, a consensus site (NX(S/T)) mediating N-linked glycosylation (Fig. 1, NLG) lies within its midsection (18, 19), >90% of the S1-S2 loop is poorly conserved between channel subtypes, a feature that has permitted its use as a site for insertion of epitope tags with retention of channel function (20). Nevertheless, inspection of the entire S1-S2 linker reveals a region that is juxtaposed to the S1 transmembrane domain, which is highly conserved between Kv channels (17) and which, based on the Kv1.2 crystal structure, may lie in close proximity to extracellular pore mouth residues emerging from the tip of S5 in an adjacent monomer (6-8, 21).

Based on the above information, we hypothesized that conserved residues proximal to S1, in the S1-S2 linker, serve a novel and undisclosed role in Kv function. Using site-directed mutagenesis, whole-cell patch clamp electrophysiology, flow cytometry, and detailed imaging of eYFP-tagged Kv1.4 expressed in cell lines, we now report the identification of a highly conserved threonine residue at the S1/S1-S2 linker interface that is absolutely required for cell surface expression of Kv channels.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials—Monoclonal antibodies GM130 and anti-calnexin were purchased from BD Biosciences and anti-HA.11 from Covance Research Products, Berkeley, CA. Polyclonal anti-GFP was obtained from Invitrogen. Oligonucleotides were synthesized by Sigma. All other chemicals were of reagent grade or higher purity.

Molecular Biology—A clone encoding Kv1.4, tagged with eYFP at the amino terminus (Swiss-Prot P15385 (22)) (wild type (WT) eYFP-Kv1.4) has been described previously (23). The rat Kv3.1 clone was a gift from Dr. R. Joho, Dallas, TX. A construct bearing mRFP attached to the amino terminus of Kv1.4 (mRFP-Kv1.4) was prepared in two stages. First, WT eYFP-Kv1.4 was digested with NheI/HindIII to remove the sequence encoding eYFP. A PCR fragment corresponding to mRFP (forward primer: 5′-CGT CAG ATC CGC TAG CGG CAC CAT GGC CTC CT-3′; Reverse primer: 5′-ACC TCC ATA GAA GCT TGA GAA TTC CAC CAC ACT GG-3′) was then inserted into NheI/HindIII-digested WT eYFP-Kv1.4 using the BD In-fusion™ Dry-Down PCR cloning kit (BD Biosciences) as per the manufacturer's instructions. The eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A, T330S, T330D, T330K, T330E, E502T, E502K, and Kv3.1:T211A mutations3 were performed using the QuikChange™ II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The hemagglutinin (HA) tag (YPYDVPDYA) was inserted into the S3-S4 linker using a PCR fusion protocol and cloned in-frame into HindIII/HindII-digested eYFP-Kv1.4. The first PCR fragment extended from the 5′-HindIII site to the Gly-432 codon in Kv1.4, plus a sequence encoding the 3′ YPYDVPD portion of the HA epitope (forward primer 1: 5′-CTC AGA TCT CGA GCT CAA GCT TC-3′; reverse primer 1: 5′-TCT GGA ACA TCA TAT GGA TAG CCA CCC CCC TGC TG-3′). The second PCR product extended 5′ from the Gly-432 codon to a 3′ HindII site and contained the coding sequence for PYDVPDYA (forward primer 2: 5′-CCA TAT GAT GTT CCA GAT TAT GCT AAC GGC CAG C-3′; reverse primer 2: 5′-GCT GCA ATA AAC AAG TT-3′) overlapping the first PCR fragment. Both PCR fragments were used as templates for a third round of PCR using forward primer 1 and reverse primer 2. The resulting fragment was then cloned into digested WT eYFP-Kv1.4 using the BD In-fusion™ Dry-Down PCR cloning kit (BD Biosciences) as per the manufacturer's instructions. A construct encoding eYFP fused to the amino terminus of Kv3.1 was prepared through PCR cloning as described above. The fidelity of all constructs was confirmed by in-house sequencing.

Tissue Culture—HEK293 and COS-7 cells (ECACC) were subcultured every 3-4 days and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% FBS (v/v), 2 mml-glutamine (w/v), and 1% penicillin and streptomycin. All transfections were carried out using FuGENE 6 (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Prior to transfection, cells from a confluent T75 flask were resuspended, seeded at a ratio of 1:4 into a 6-well plate, and grown to 50% confluency overnight at 37 °C. Twenty-four hours post-transfection cells, were reseeded at a ratio of 1:4 onto collagen-coated coverslips for immunofluorescence and electrophysiology or into 25-cm3 flasks for FACS analysis.

Electrophysiology—Whole-cell currents were recorded in transfected HEK293 cells using the voltage clamp configuration of the patch clamp technique. Single, moderately green-fluorescing cells were selected for recording 48 h after transfection. The bathing solution contained (in mm): 145 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose, adjusted to pH 7.35 with NaOH (320-330 mosm). The pipette solution contained (in mm): 110 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 5 K4-BAPTA, 2 K2-ATP and 10 HEPES, adjusted with KOH to pH 7.2 (300-310 mosm). Pipettes were manufactured from borosilicate glass using a model P-97 puller (Sutter Instruments) and displayed a resistance of 2-3 megohms when filled with pipette solution. Currents were evoked from a holding potential of -80 mV in 20-mV voltage steps of 1500 ms, between -60 mV and + 60 mV, with an intersweep interval of 15 s. Command and acquisition was performed using an Axopatch 200B amplifier, Digidata 1322A analogue-digital converter, and Clampex 9.2 software (Axon Instruments). Capacitative transients were cancelled by analog compensation. Series resistance was typically <10 megohms and was not compensated. The +60mV voltage step was used to determine peak and steady-state (end of step) current densities. Current traces were fit as described (23).

Immunostaining of Transfected HEK293 and COS-7 Cells—Transiently transfected HEK293 and COS-7 cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 48 h post-transfection and mounted onto glass slides using ProLong Gold anti-fade (Molecular Probes). The surface expression of HA-tagged Kv1.4 proteins was determined by incubating live cells with anti-HA antibodies (1:1000) for 30 min at 37 °C prior to fixation and subsequent detection with Cy3-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch and Stratech Scientific, Cambridgeshire, UK). Intracellular staining of organelles and total (intracellular + surface) protein detection was performed by fixing cells in 4% paraformaldehyde (as described above), and permeabilizing with 0.5% saponin for 5 min followed by incubation with primary antibodies raised against the appropriate markers at a concentration of 10 μg/ml in 0.01% (v/v) saponin/PBS-. Detection of specific staining was performed with the appropriate Cy3-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:200). All imaging was done within 1 day of fixation.

Fluorescence-activated Cell Sorting (FACS)—For surface expression analysis (24), cells at 48-72 h post-transfection were resuspended and the concentration adjusted to 5 × 107 cells/ml with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 1% FBS (v/v). Aliquots (100 μl) of cells were then incubated with anti-HA primary antibody (10 μg/ml in Dulbecco's PBS with calcium and magnesium (PBS+)) for 30 min at 4 °C. After three washes with 300 μl of PBS+ containing 1% FBS (v/v), samples were incubated with Cy5-conjugated goat secondary anti-mouse IgG1 (1:200) diluted in 10% FBS and 90% PBS+ (v/v) for 45 min at 4 °C. The cells were then fixed with 100-μl aliquots of 2% (w/v) formaldehyde, 100 μl of PBS-, and 300 μl of PBS+. The dilutions of antibodies used were saturating as confirmed by titration. Cells (20,000/sample) were analyzed in a FACScaliber® flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), and mean fluorescence intensity values were taken.

DeltaVision Deconvolution Microscopy—Cells on mounted coverslips were visualized using a DeltaVision restoration microscope system (Applied Precision Instruments, Seattle, WA) comprising an Olympus IX-70 inverted microscope fitted with a ×100 UPLAN objective (NA 1.35) and Photometrics CH350L charge-coupled device camera interfaced to a Unix-based computer system equipped with SoftWoRx, version 3.5.0, acquisition software. Epifluorescence was recorded using filter sets for DAPI/FITC (fluorescein isothiocyanate)/Texas Red and Cy3/Cy5. Wide field optical sections of 0.2 μm were acquired throughout the z plane of the cells. The resulting z stacks were then deconvolved using a constrained iterative algorithm assigned by DeltaVision (24). Surface and intracellular fluorescence analyses were performed by comparing fluorescence intensity-distance (pixels) profiles (line scans) on color-split RGB images for red (surface), where applicable (HA-tagged Kvs), green (total Kv), and blue (nuclei) from a point of origin (Xo) on the nucleus to an end point (Xe) beyond the cell margin, noting the positions of the nuclear (Xn) and plasma (Xm) membrane (supplemental Fig. S1). Mean intracellular (Ic) intensities (fluorescence intensity/pixel) were then calculated as the total green fluorescence integrated over distance Xm - Xn divided by the distance (Xm - Xn) in pixels. Mean membrane intensities (Im) for green Kv fluorescence were derived similarly, averaging green Kv fluorescence between membrane boundaries defined by either the peak red (surface) fluorescence (anti-HA images) or (for non-anti-HA images) assuming an average membrane width of ±10 pixels about Xm (a conservative assumption, which overestimates Im particularly when surface expression is low).

Statistical Analysis—All data are expressed as the mean ± S.E. for n samples. Curve fits and regression analysis were done using SigmaPlot software (Systat, San Jose, CA). Statistical comparisons were made using one-way analysis of variance and Tukey's or Student-Newman-Keuls post-hoc analysis with SigmaStat and Microsoft Excel software.

RESULTS

Mutation of Threonine 330 to Alanine Localizes Kv1.4 to the ER and Reduces Its Surface Expression—Mammalian Kv channels contain an S1-S2 extracellular linker that is highly variable both in length and composition (1, 17-19). Nevertheless, sequence comparisons identify an extracellular region flanking, the S1 transmembrane-spanning domain (residues in Kv1.4, LETL) that is highly conserved between all members of the rat Kv1 family (Fig. 1) and, within this region, a threonine residue conserved across other voltage-gated Kv family members (17) (Fig. 1, boxed and asterisk). To define the role of the threonine residue, we tested its functional contribution in Kv1.4 modified with an amino-terminal eYFP tag (hereafter, WT eYFP-Kv1.4), a model Kv channel that shows efficient surface expression and assembly in diverse expression systems (23, 25, 26). Using site-directed mutagenesis, we first replaced the corresponding residue, Thr-330,3 with an alanine (construct eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A). For the bulk of our analysis, expression was conducted in HEK293 cells owing to their lack of endogenous Kvs (23, 26), ability to recapitulate phosphorylation-dependent Kv regulation (27), and neuronal origin (28). Transient transfection of HEK293 cells with WT eYFP-Kv1.4 and subsequent fluorescence imaging revealed strong fluorescence at the margins of all cells examined (n = 200), commensurate with cell surface localization. Detailed line scan analysis (supplemental Fig. S1, A and B) showed that the ratio of surface (Im) to intracellular (Ic) WT eYFP-Kv1.4 fluorescence was constant, regardless of expression level (supplemental Fig. S1, G and H). Identical to previous reports, we also saw some intracellular labeling consistent with the presence of WT eYFP-Kv1.4 in intracellular trafficking organelles (23, 26) (Fig. 2A, i). In contrast, HEK293 cells transfected with eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A showed a pattern of fluorescence resembling that for localization in the ER (29) (Fig. 2A, ii (n = 180)). Line scan analysis (supplemental Fig. S1, C and D) showed that the ratio of surface (Im) to intracellular (Ic) eYFP-Kv1.4: T330A fluorescence was significantly (p < 0.001, t test) lower (Im/Ic = 0.46 ± 0.03 (n = 15)) compared with WT-eYFP-Kv1.4 (Im/Ic = 1.5 ± 0.13 (n = 12)), and constant, regardless of expression level (supplemental Fig. S1, G and H). Following transfection of COS-7 cells, WT eYFP-Kv1.4 was localized to ruffles at the cell periphery and the planar surface (Fig. 2A, iii), and eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A was restricted to an intracellular compartment, most likely the ER (Fig. 2A, iv). Thus, WT- and eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A show very different distributions regardless of the host cell in which they are expressed and of the construct expression levels. In no case did we find evidence for aggregation within the ER or the cytoplasm such as that reported for expression of highly misfolded Kv channels (3) or cytotoxicity (not shown).

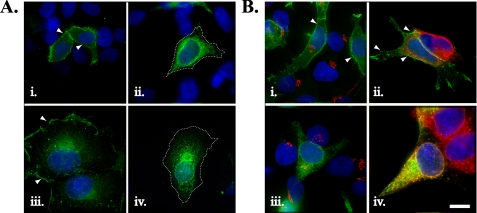

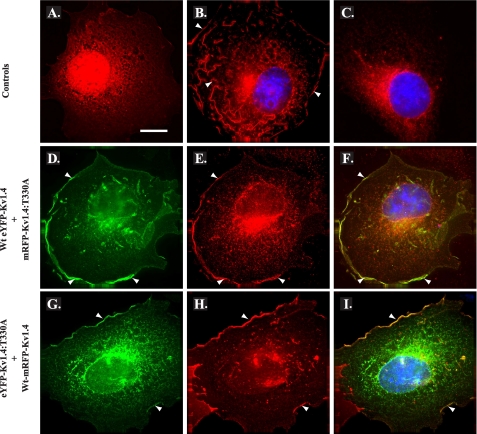

FIGURE 2.

Subcellular distribution of WT eYFP-Kv1.4 and eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A determined by fluorescence imaging. A, comparison of expression of WT eYFP-Kv1.4 (i and iii) and eYFP HA-Kv1.4:T330A (ii and iv) channels in HEK293 cells (i and ii) and COS-7 cells (iii and iv). Arrowheads denote surface expression, and dashes in ii and iv indicate cell margins (determined via image overenhancement). Cells were transiently transfected, fixed, and viewed under a ×100 objective using a DeltaVision work station. B, comparison of distribution of WT eYFP-Kv1.4 (i and ii) or eYFP HA-Kv1.4:T330A (iii and iv) channels in the Golgi apparatus (i and iii) and ER (ii and iv). HEK293 cells were transiently transfected and, after 48 h, were fixed, permeabilized, and treated with antibodies raised against marker proteins of the Golgi apparatus (anti-GM130) or the ER (anti-calnexin) with subsequent detection using appropriate Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody. Green, eYFP fluorescence; blue, DAPI (nuclei); red, Cy3 secondary antibody. Areas of red/green overlap are shown in yellow. Scale bar, 15 μm.

To confirm that eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A was localized to the ER, transfected HEK293 cells were subjected to immunocytochemistry using antibodies raised against calnexin (an ER-localized protein) and GM130, a protein localized to the Golgi apparatus (Fig. 2B) (24). Neither WT eYFP-Kv1.4 nor eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A labeling co-localized with the Golgi marker (Fig. 2B, i and iii, respectively), nor was there significant overlap between WT eYFP-Kv1.4 expression and calnexin staining (Fig. 2B, ii). However, eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A labeling completely overlapped that of calnexin (Fig. 2B, iv), indicating that the mutant channel was indeed localized to the ER and not expressed at the cell surface.

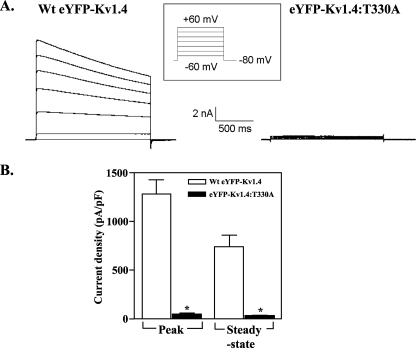

Further evidence for the lack of eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A channels at the cell surface was obtained through whole-cell patch clamping of transfected HEK293 cells (Fig. 3). Within 48 h of transfection, cells expressing WT eYFP-Kv1.4 displayed large outward K+ currents in response to depolarization (Fig. 3A, left). In contrast, cells expressing eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A showed negligible currents (Fig. 3A, right) similar to those obtained in mock transfected cells (not shown). To facilitate the comparison and compensate for differences in cell size, currents (in pA) were standardized to corresponding capacitances (in pF) to yield current densities (23). Cells transfected with WT eYFP-Kv1.4 showed peak and steady-state current densities of 1279 ± 144 pA/pF (n = 7) and 748 ± 104 pA/pF (n = 7), respectively, whereas those for cells transfected with eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A were 22-28 fold lower (peak, 45.2 ± 11.2 pA/pF (n = 5); steady state, 33.2 ± 9.0 pA/pF (n = 5)) (p < 0.01, Tukey) (Fig. 3B). The effects of the Thr-to-Ala mutation are also independent of the eYFP tag, because cells transfected with a Kv1.4:Thr → Ala construct lacking eYFP showed peak and steady-state currents of 18 ± 7 pA/pF (n = 5) and 12 ± 5 pA/pF (n = 11) (p < 0.01, Tukey (data not shown)), some 30-fold lower than reported for WT Kv1.4 (25, 26). Taken together, our data argue that the expression of functional Kv1.4 channels at the cell surface is compromised severely in the eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A mutant.

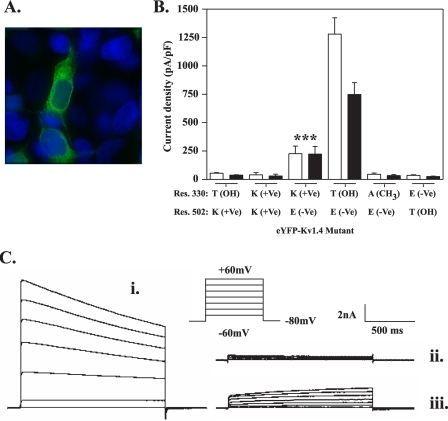

FIGURE 3.

Heterologous expression of functional WT eYFP-Kv1.4 and eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A channels. A, representative traces of whole-cell currents evoked in WT eYFP-Kv1.4 and eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A-transfected HEK293 cells. Whole-cell currents were recorded by patch clamp electrophysiology in response to 20-mV voltage steps between -60 and +60 mV from a holding potential of -80 mV as described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, Mean ± S.E. data of peak and steady-state currents (measured at the end of the voltage step) at +60 mV normalized to cell capacitance.

Epitope-tagged Kv1.4 Channels Confirm That Threonine 330 Is Required for Cell Surface Expression—Because electrophysiology can provide information only about the expression of functional channels, we sought independent quantitation of differences in WT eYFP-Kv1.4 and eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A total (functional + nonfunctional) cell surface expression using FACS analysis (24). First, we introduced an extracellular HA tag into the S3-S4 linker (see “Experimental Procedures”) of the WT eYFP-Kv1.4 and eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A constructs (WT HA34-eYFP-Kv1.4 and HA34-eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A, respectively).

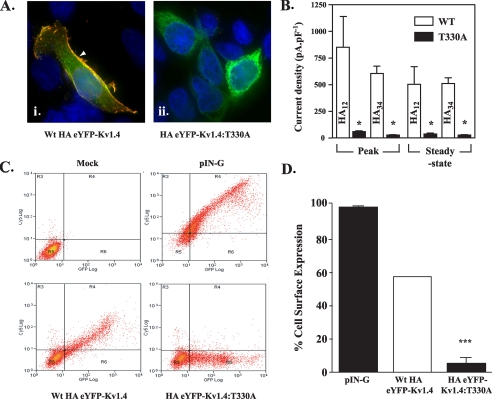

To confirm differences in surface expression visually, live HEK293 cells transfected with the WT or mutant HA-tagged channels were preincubated with anti-HA antibody, fixed, and labeled with a Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody. Transfection with WT HA34-eYFP-Kv1.4 gave a pattern of Cy3 (red) labeling around the cell margins that overlapped (yellow) the cell surface but not intracellular eYFP (green) fluorescence (Fig. 4A, i). In contrast, cells transfected with HA34-eYFP-Kv1.4: T330A showed no Cy3 fluorescence at the cell surface (Fig. 4A, ii) and showed eYFP fluorescence similar to eYFP-Kv1.4: T330A (Fig. 2A, ii). Thus, our data indicate that mutant T330A is localized to the ER, regardless of the presence of the HA tag in S3-S4, whereas the WT channel reaches the cell surface.

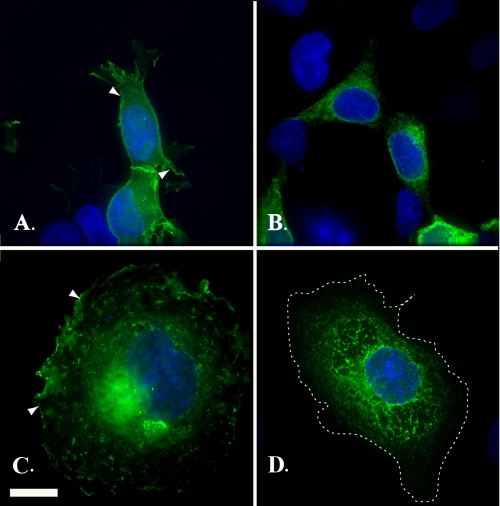

FIGURE 4.

Surface levels of HA-tagged eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A are reduced compared with HA-tagged WT eYFP-Kv1.4. A, imaging reveals surface localization (arrowheads) of WT HA12-eYFP-Kv1.4 (i) and ER localization of HA12-eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A (ii). Live, transiently transfected HEK293 cells were labeled, at 48 h post-transfection with anti-HA antibody to detect surface channels prior to fixation and detection with a Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody. Green, eYFP fluorescence; red, Cy3 secondary antibody; blue, DAPI (nuclei) stain. Scale bar corresponds to 15 μm. B, patch clamp recordings show reduction in surface expression of HA-eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A versus WT HA-eYFP-Kv1.4 channels, which is independent of the location of the HA tag. Whole-cell currents were evoked in cells transfected with WT HA-eYFP-Kv1.4 or eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A mutants bearing the HA epitope tag in either the S1-S2 (HA12-eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A) or S3-S4 (HA34-eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A) linkers. Cells were held at a potential of -80 mV and currents measured in response to 20-mV voltage steps between -60 and +60 mV. Mean ± S.E. data of peak and steady-state currents (measured at the end of the voltage step) at +60 mV normalized to cell capacitance. Asterisks, p < 0.05, Tukey. C, quantitation of surface expression through FACS. Following surface labeling with anti-HA (primary) and Cy5 (secondary) antibody, mock-transfected control HEK293 cells (upper left panel) show low background fluorescence (log scale) in red (Cy5, surface; ordinate) and green (eYFP; abscissa) channels (defined as background, quadrant R5). Transfection with an HA- and GFP-tagged membrane marker (pIN-G) (23) (positive control; upper right panel), WT HA34-eYFP-Kv1.4 (lower left panel), or HA34-eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A (lower right panel) revealed a cell population displaying fluorescence in red and green channels (quadrant R4). Note size of population in quadrant R6 (low red (surface) fluorescence) for cells transfected with HA-eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A. D, comparison of HA34-eYFP-Kv1.4: T330A and WT HA34-eYFP-Kv1.4 surface expression determined by FACS. Data were determined from the ratio of surface to total population fluorescence (i.e. R4/(R4 + R6)) and normalized to the WT HA34-tagged channel (100%). A significant difference (n > 3, p < 0.05; Student-Newman-Keuls test) was observed between the WT and T330A mutants.

As shown in Fig. 4B, cells expressing WT HA34-tagged eYFP-Kv1.4 showed current densities (peak, 612 ± 67 pA/pF (n = 6); steady state, 517 ± 50 pA/pF (n = 6)) somewhat lower (p < 0.05, Tukey) than those obtained from cells transfected with WT eYFP-Kv1.4 (Fig. 3) but typical for mutants bearing epitope tags at this position (30). In contrast to WT HA34-eYFP-Kv1.4 transfectants, cells expressing the HA34-eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A mutant showed a 16-19-fold reduction (p < 0.05, Tukey) in current densities (peak, 38 ± 8 pA/pF (n = 4); steady state, 27 ± 6 pA/pF (n = 4)) (Fig. 4B). Further confirmation of the specific effect of T330A was provided using a second set of WT and T330A mutant constructs where the HA tag was placed in the S1-S2 linker (WT HA12-eYFP-Kv1.4 and HA12-eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A, respectively). Cells transfected with HA12-eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A showed a 15-17-fold reduction in current density (peak, 52 ± 8.6 pA/pF (n = 8); steady state, 34.5 ± 4.8 pA/pF (n = 8)) compared with WT HA12-eYFP-Kv1.4 (peak, 862 ± 289 pA/pF (n = 10); steady state, 502 ± 184 pA/pF (n = 10)) (Fig. 4B). Together, these data support a significant (p < 0.05, Tukey) decrease in T330A mutant versus WT channels at the cell surface, regardless of the presence and location of the inserted epitope tag.

To quantify the proportion of mutant versus WT channels at the cell surface, live cells transfected with WT HA34-eYFP-Kv1.4 or HA34-eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A plasmids were again treated with anti-HA primary antibodies, fixed, treated with Cy3 secondary antibodies to reveal surface expression, and then subjected to flow cytometry (24) (Fig. 4, C and D). Mock-transfected cells showed low signals in both red (surface) and green (intracellular + surface) fluorescence channels (Fig. 4C upper left, quadrant R5). Following transfection with WT HA34-eYFP-Kv1.4, a cell population expressing surface channels could be identified (Fig. 4C, lower left, quadrant R4). In contrast, the fraction of cells expressing surface channels was much lower following transfection with the HA34-eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A mutant (Fig. 4C, lower right, quadrant R4). As a standard control between experiments, we also examined the surface expression of an HA- and eGFP-tagged plasma membrane reporter construct, pIN-G (24) (Fig. 4C, upper right). By comparing the fraction of cells showing surface to total channel expression (i.e. (R4/(R4 + R6)) following normalization to wild type expression, we determined the surface expression of the HA34-eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A mutant to be 9% of that of WT HA34-eYFP-Kv1.4, again indicating the requirement for threonine at position 330 (Fig. 4D). In each experiment, there was a linear relationship between Cy5 (surface) and eYFP (intracellular + surface eYFP-Kv1.4) fluorescence, indicating that surface expression was always a constant fraction of the total cellular expression level, independently of cell to cell variability, and was not exaggerated by high levels of total expression. Although lowering the cell incubation temperature to 27 °C can rescue the surface expression of some membrane proteins that have become trapped in the ER through misfolding (31), using FACS analysis we found no surface expression of HA34-eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A channels in cells grown at 27 °C (data not shown).

eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A Surface Expression Is Rescued When Co-expressed with WT eYFP-Kv1.4 Channels—Co-assembly of Kv monomers to form homo- or heterotetrameric channels is obligatory for the formation of functional Kv channels (1, 9, 10, 32). As the Kv1.4:T330A mutant localized to the ER (Fig. 2B, iv), we considered it possible that it might act in a dominant-negative fashion to preclude co-assembling channel subunits from reaching the cell surface. To examine this issue, we prepared additional constructs encoding red fluorescent WT and T330A mutant Kv1.4 by substituting the amino-terminal eYFP (green) for mRFP (WT mRFP-Kv1.4 and mRFP-Kv1.4:T330A, respectively). In control experiments, expression of WT mRFP-Kv1.4 in transfected COS-7 cells yielded patterns of fluorescence localized primarily to the planar cell surface and ruffles (Fig. 5B), similar to that seen with WT eYFP-Kv1.4 (Fig. 2A, iii). In contrast, after expression of the mRFP-Kv1.4:T330A mutant, fluorescence was localized intracellularly (Fig. 5C) as found for eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A (Fig. 2A, iv). Expression of the mRFP fluorophore alone yielded fluorescence throughout the cytoplasm but absent from organelles, as anticipated for this soluble protein (Fig. 5A). These data indicate that mRFP-Kv1.4:T330A reports the effect of the threonine mutation faithfully, and owing to the difference in mRFP and eYFP protein sequences, this effect is attributable to the mutation and independent of the amino-terminal fluorophore.

FIGURE 5.

Co-expression with WT channels promotes surface expression of T330A mutant channel subunits. COS-7 cells transiently transfected with mRFP (red; control) (A), WT mRFP-Kv1.4 (red; WT control) (B), or mRFP-Kv1.4:T330A (red; T:A mutant, control) (C) demonstrate a distribution similar to their eYFP-tagged counterparts (see Fig. 2). D and E, co-expression of WT eYFP-Kv1.4 (D) (green) and mRFP-Kv1.4:T330A (E) (red) promotes relocation of T:A mutant channel subunits to the cell surface consistent with formation of WT:mutant heterotetramers and WT rescue. F, merged images D and E; areas of red/green overlap are shown in yellow. G and H, reciprocal co-expression of eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A (G) (green) and WT mRFP-Kv1.4 (H) (red), again commensurate with heterotetramerization and WT rescue of ER-localized channel subunits. I, merged images G and H; areas of red/green overlap are shown in yellow. Blue, DAPI (nuclei). Arrowheads denote surface expression. Cells were transiently transfected and, after 48 h, were fixed, permeabilized, and subjected to immunocytochemistry (“Experimental Procedures”). Scale bar, 15 μm. (See also supplemental Fig. S2.)

Having generated both red and green fluorescent WT and T330A mutants, we next asked whether the T330A mutants showed any competence for co-assembly and if so whether their cell surface expression could be rescued by complexation with WT subunits. First, we examined the distribution of fluorescence following co-expression of WT eYFP-Kv1.4 with mRFP-Kv1.4:T330A at a 1:1 ratio. As shown in Fig. 5, D-F, co-expression of mRFP-Kv1.4:T330A (red) with WT eYFP-Kv1.4 (green) did not interfere with the extensive surface distribution seen with WT mRFP-Kv1.4 alone (Fig. 5B). Rather, the fluorescence corresponding to mRFP-Kv1.4:T330A (Fig. 5E) could now be detected both intracellularly and, more significantly, at the cell surface, in a pattern that overlapped that of WT eYFP-Kv1.4 (Fig. 5F) and was converse to that seen with mRFP-Kv1.4:T330A when expressed alone (Fig. 5C). Reciprocal co-expression experiments using WT mRFP-Kv1.4 and eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A confirmed the surface expression of the mutant in the presence of the WT channel (Fig. 5, G and I) and, again, the inability of the T330A mutant to suppress surface localization of the WT channel (Fig. 5 panels H and I). Transfection of HEK293 cells with HA34-WT mRFP-Kv1.4 and HA34-eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A at a 1:1 ratio (supplemental Fig. S2B) afforded identical results and, through FACS analysis, revealed that surface expression of co-assembled subunits was 96 ± 3% of the level seen with HA-WT mRFP-Kv1.4 (supplemental Fig. S2E). Thus, we conclude that although Kv1.4:T330A shows strong intracellular retention, it is able to co-assemble with WT Kv1.4 channels whereupon it becomes trafficked to the cell surface. The rescue of the T330A mutant by WT subunits, therefore, argues that the mutant does not act in a dominant-negative fashion.

Requirement of a Hydroxyl Residue for Surface Expression—To gain some insight into the mechanism underlying the profound effect of Thr-330 on Kv localization, we examined the structural requirements at position 330 for cell surface expression. First, we examined the requirement for a free hydroxyl group using a mutant (eYFP-Kv1.4:T330S), where threonine 330 had been substituted for a serine residue (T330S). In both HEK293 (Fig. 6A) and COS-7 (Fig. 6C) cells, eYFP-Kv1.4:T330S showed strong cell surface expression. Moreover, line scan analysis of eYFP-Kv1.4:T330S (supplemental Fig. S1, E and F) showed that the ratio of surface versus intracellular expression, Im/Ic, was constant (1.24 ± 0.08 (n = 20)) regardless of the expression level and was not significantly different (p > 0.05, t test) from that of WT eYFP-Kv1.4 (supplemental Fig. S1, G and H). In contrast, substitution of Thr-330 with a similar sized, but more acidic, aspartate residue (eYFP-Kv1.4:T330D) gave a pattern of fluorescence in both HEK293 (Fig. 6B) and COS-7 (Fig. 6D) cells, localized to tubulovesicular structures rather than the cell surface. The requirement for a free hydroxyl group at position 330 was substantiated through patch clamp electrophysiology. Thus, HEK293 cells expressing eYFP-Kv1.4:T330S gave depolarization-activated currents with peak and steady-state current densities of 1418 ± 124 (n = 7) and 828 ± 79 (n = 7) pA/pF, respectively, similar (p > 0.05, Tukey) to WT eYFP-Kv1.4 (peak, 1279 ± 144; steady state, 748 ± 104 pA/pF, respectively (n = 7)) (traces not shown).

FIGURE 6.

Mutations of threonine to either a serine (eYFP-Kv1.4:T330S) or an aspartic acid (eYFP-Kv1.4:T330D) indicate a requirement for a hydroxyl group. HEK293 cells (A and B) and COS-7 cells (C and D) transiently expressing eYFP-Kv1.4:T330S (A and C) or eYFP-Kv1.4:T330D (B and D) were fixed at 48 h post-transfection and viewed under a ×100 objective using a DeltaVision work station. Green, eYFP fluorescence; blue, DAPI (nuclei). Scale bar, 15 μm.

Potential Mechanism of Surface Expression—Our observation that surface expression was contingent upon the hydroxylated amino acids, threonine or serine, suggested that Kv trafficking might require hydrogen bonding between conserved Thr-330 and neighboring protein residues. To test this hypothesis, we first sought to identify candidate interacting residues in Kvs that satisfied three criteria: their possible proximity to Thr-330, their hydrogen bonding potential, and a high degree of conservation across Kv channels equivalent to that of Thr-330. Because the structure of Kv1.4 was unavailable, the structure of the homologous Kv1.2 channel (6) was used as a template. Our modeling places Thr-330 close to outer pore residues in the proximal (amino-terminal) region of the extracellular S5-S6 linker of the adjacent subunit,- a site already proposed to be one of the few points of contact between the voltage-sensing and gating domains (6, 21). Of these proximal S5-S6 residues, one in particular, Glu-502, satisfied our test criteria and was thus chosen for further analysis.

As shown in Fig. 7A, expression of a mutant where Glu-502 was substituted with a valine residue (eYFP-Kv1.4:E502V) in HEK293 cells revealed a strong tubulovesicular pattern similar to that seen with eYFP-Kv1.4:T330A (Fig. 2A, ii). The poor surface expression of eYFP-Kv1.4:E502V was further confirmed by line scan analysis (supplemental Fig. S1H) and patch clamp electrophysiology. Thus, cells expressing eYFP-Kv1.4:E502V gave depolarization-activated currents with peak (28 ± 6 pA/pF (n = 4)) and steady-state (21 ± 5 pA/pF (n = 4)) current densities (traces not shown) that were only 2% (peak; p < 0.05, Tukey) and 3% (steady state; p < 0.05, Tukey) of those seen for WT eYFP-Kv1.4 (Fig. 3). Intracellular retention was also observed when Glu-502 was replaced with a positively charged lysine residue (eYFP-Kv1.4:E502K; Table 1 and supplemental Figs. S1 and S3). However, partial surface expression was evident in a conservative mutant where Glu-502 was replaced with an aspartate residue (eYFP-Kv1.4:E502D; Table 1 and supplemental Fig. S1H). Partial surface expression was also seen for eYFP-Kv1.4:E502T; however, this mutant showed very weak currents (Table 1 and supplemental Figs. S1 and S3). Thus, Kv1.4 surface expression generally requires conservation of the respective side chain properties when either the threonine or glutamate at positions 330 and 502, respectively, are mutated.

FIGURE 7.

A T330K mutant engineered as a potential electrostatic bridge to Glu-502 in the S5-S6 linker shows partial surface expression. A, replacement of Glu-502 with valine causes retention in the endoplasmic reticulum. HEK293 cells were transfected with mutant eYFP-Kv1.4:E502K (green) and after 48 h fixed and viewed under a ×100 objective using a DeltaVision work station as described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, comparison of the surface expression of eYFP-Kv1.4 channels mutated at positions 330 and/or 502 determined by patch clamp electrophysiology. Peak (open bars) and steady-state (filled bars) current densities were obtained from at least five cells transfected with the indicated constructs. Data are shown as mean ± S.E. data of peak and steady-state currents (measured at the end of the voltage step) at +60 mV normalized to cell capacitance. Asterisk, p < 0.005, analysis of variance, with Student-Newman-Keuls correction compared with both WT and all other indicated mutants. For each construct, residues are shown using standard amino acid nomenclature. Parentheses denote nature of side chain as follows: +Ve, cationic; -Ve, anionic; CH3, uncharged; OH, hydrogen bond donor. The WT channel is indicated in bars 7 and 8. Note the partial expression of the T330K mutant (bars 5 and 6). C, representative traces of whole-cell currents evoked in WT eYFP-Kv1.4- (i), eYFP-Kv1.4: T330A- (ii), and eYFP-Kv1.4:T330K-transfected HEK293 cells. Whole-cell currents were recorded by patch clamp electrophysiology in response to 20-mV voltage steps between -60 and +60 mV from a holding potential of -80 mV as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Note the absence of inactivation in the eYFP-Kv1.4: T330K mutant (iii) compared with WT (i). ***, p < 0.005.

TABLE 1.

Subcellular distributions of mutations at positions 330 and 502 in the eYFP-Kv1.4 channel

The data represent compilations of the relative surface versus endoplasmic reticulum distributions of the indicated Kv1.4 mutant constructs expressed in HEK293 cells as determined by electrophysiology and flow cytometry (normalize to HA-tagged WT). All data are shown as mean ± S.E. (n ≥ 5). (See also supplemental Fig. S3.) Note the correlation between channel surface expression and currents, with the exception of E502T, which shows 30% surface expression but low currents, and T330K, which shows partial surface expression and modest currents. ND denotes not determined.

|

Mutant

|

Potential

bridgea

|

Surface

%b

|

Current densities (PA/PE)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak | Steady state | |||

| Thr-330 (WT) | Thr ↔ Glu (WT) | 100 | 1279 ± 144 (7) | 748 ± 104 (7) |

| T330S | Ser ↔ Glu | 65 ± 11 | 1418 ± 124 (7) | 828 ± 79 (7) |

| T330K | Lys ↔ Glu | 21 ± 3 | 226 ± 67 (8) | 223 ± 67 (8) |

| T330A | Ala ↔ Glu | 9 ± 5 | 45 ± 11 (5) | 33 ± 9 (5) |

| E502V | Thr ↔ Val | 7 ± 7 | 28 ± 6 (4) | 21 ± 5 (4) |

| E502D | Thr ↔ Asp | 30 ± 4 | ND | ND |

| E502T | Thr ↔ Thr | 28 ± 10 | 27 ± 5 (4) | 20 ± 5 (4) |

| E502K | Thr ↔ Lys | 9 ± 5 | 54 ± 6 (5) | 37 ± 4 (5) |

| T330S,E502D | Ser ↔ Asp | 12 ± 3 | ND | ND |

| T330E,E502T | Glu ↔ Thr | 9 ± 5 | 35 ± 6 (6) | 25 ± 4 (6) |

| T330K,E502K | Lys ↔ Lys | 0 ± 0 | 40 ± 20 (5) | 30 ± 16 (5) |

Between positions 330 and 502.

FACS analysis (n > 5).

To test for direct interactions between Thr-330 and Glu-502, we next examined the surface expression of channels bearing double mutations. In contrast to the WT channel (i.e. Thr-330—Glu-502), a reciprocal swap mutant, eYFP-Kv1.4: T330E,E502T, showed no surface expression in imaging experiments (see also line scan analysis in supplemental Fig. S1H) and in electrophysiology gave current densities (peak, 35 ± 6 pA/pF (n = 6); steady state, 25 ± 4 pA/pF (n = 6)) that were only 3% (at peak and steady state; p < 0.05, Tukey) of those seen with WT eYFP-Kv1.4 (Fig. 7B and Table 1, supplemental Figs. S1 and S3). In addition, a mutant bearing both the T330S and E502D substitutions (which had individually effected some surface expression; Fig. 6 and Table 1) also showed strong retention in tubulovesicular structures (Table 1, supplemental Fig. S1H). Together, these data suggested either the possibility of bridging between positions 330 and 502, via a select configuration of hydrogen bonding residues, or the existence of independent, but additive, trafficking effects at positions 330 and 502. To examine this issue further, we expressed a construct, eYFP-Kv1.4:T330K, designed to reconstitute a bridge artificially through electrostatic interaction between a lysine introduced at position 330 and Glu-502 of the WT channel. Significantly, upon expression eYFP-Kv1.4:T330K gave peak (226 ± 67pA/pF (n = 8)) and steady-state (223 ± 67 pA/pF (n = 8)) current densities 5-fold greater (Fig. 7, B and C, iii) than did T330A (Figs. 3 and 7, B and C, ii) or other mutants (see above; Table 1 and supplemental Figs. S1 and S3) conferring intracellular retention (p < 0.05, Tukey) and 6-fold less than those seen for WT eYFP-Kv1.4 (Fig. 7, BC, i) (peak; p < 0.05, Tukey) and (steady state; p < 0.05, Tukey). In contrast, peak and steady-state currents were negligible in a charge-repulsion mutant eYFP-Kv1.4:T330K,E502K (and also eYFP-Kv1.4:T330E). (See also supplemental Fig. S3.)

Owing to its partial surface expression, the eYFP-Kv1.4: T330K mutant afforded a unique insight into the mechanism by which Thr-330 might act. Specifically, and in contrast to WT eYFP-Kv1.4, which shows slow inactivation (τinact 2908 ± 386 ms (n = 7)), the eYFP-Kv1.4:T330K mutant failed to inactivate (τinact absent (n = 8)) (Fig. 7C, iii). Thus, mutation of an S1-S2 linker residue (Thr-330) can transmit its effects to the pore domain responsible for C-type inactivation (see “Discussion”).

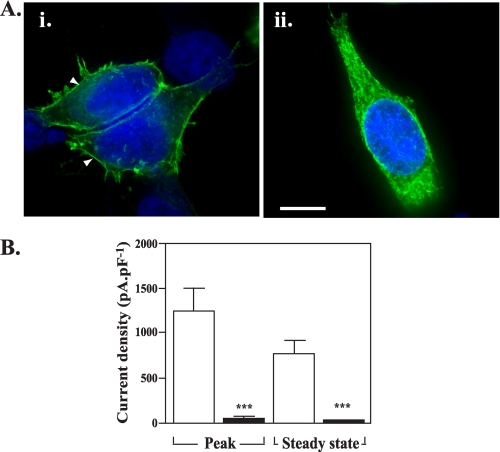

The Requirement for Threonine at Position 330 in Kv1.4 Extends to Other Kv Family Members—Inspection of the S1-S2 linker sequence between Kv family members highlights the high degree to which Thr-330 in Kv1.4 is conserved (Fig. 1). Nevertheless, such conservation may be fortuitous, and the requirement for Thr-330 in surface expression may be restricted to Kv1.4 or its close Kv1 series relatives. We therefore tested whether the conserved threonine might be a general requirement in Kv channels, using Kv3.1, which can form functional homotetramers but is more distantly related to, and unable to assemble with, Kv1.4 (5, 33, 34). Again, eYFP was fused to the amino terminus, and the resulting WT or mutant constructs (WT eYFP-Kv3.1 and eYFP-Kv3.1:T211A, respectively) were expressed in HEK293 cells. Cells expressing WT eYFP-Kv3.1 (Fig. 8A, i) showed labeling at the cell periphery consistent with surface expression. In contrast, cells expressing eYFP-Kv3.1:T211A (Fig. 8A, ii) showed extensive intracellular labeling similar to that found with the Kv1.4:T330A constructs (confirmed by line scan analysis, supplemental Fig. S1H), consistent with localization in the ER (29). Cells transfected with WT eYFP-Kv3.1 showed peak and steady-state current densities of 1236 ± 261 pA/pF (n = 4) and 769 ± 134 pA/pF (n = 4), respectively, whereas those for cells transfected with eYFP-Kv3.1:T211A were 28-33-fold lower (peak, 38 ± 8 pA/pF (n = 5); steady state, 27 ± 6 pA/pF (n = 5))(p < 0.05 t test)(Fig. 8B). Thus, we concluded that the highly conserved threonine residue plays a role in promoting surface expression in Kv family members in addition to Kv1.4.

FIGURE 8.

The requirement of Thr-330 for surface expression extends to other Kv families. A, HEK293 cells transiently expressing WT eYFP-Kv3.1 (i) or eYFP-Kv3.1:T211A (ii) were fixed at 48 h post-transfection and subjected to fluorescence imaging to determine their subcellular distribution (green, eYFP). Arrowheads denote surface expression. Scale bar, 15 μm. B, mean ± S.E. data of peak and steady-state currents (measured at the end of the voltage step) at +60 mV normalized to cell capacitance.

DISCUSSION

In this article we have identified a single threonine residue, Thr-330, lying at the interface of S1 and the extracellular S1-S2 linker, which appears to be critical for the cell surface expression of Kv channels. Precisely what role this residue plays is presently unclear, but it seems to affect the channel at many levels. The confinement of the T330A mutant to the ER suggests that Thr-330 plays an important early role in channel biogenesis. Although the motif in Kv1.4 lies within flanking residues that resemble the diacidic (EXD) ER export signals of non-voltage-gated channels such as Kir2.1 (35, 36), those motifs have a cytoplasmic rather than extracellular disposition. Thus, it seems that Thr-330 acts either at the level of topogenesis or subunit assembly. Using Kv1.3 as a model, Deutsch and colleagues (11, 37) have provided evidence that S1 does not initiate translocation or integration into the lipid bilayer and may require the prior incorporation of the biogenic units S2-S4 and S5-S6 preassembled within the translocon (37). Thus, Thr-330 could facilitate insertion or stabilize each nascent monomer. However, because co-expression of WT Kv1.4 with Kv1.4:T330A mutants can rescue cell surface expression, it seems more likely that Thr-330 acts at the level of co-assembly of Kv tetramers, presumably after co-association of the first tetramerization (T1) domains.

To gain insight into how the critical threonine might function, we examined the cellular localization of several mutants at position 330. As serine, a residue closely related to threonine, afforded surface expression, it seemed possible that phosphorylation by serine/threonine kinases might control surface expression. However, such kinases are not located within the ER lumen (38) and are thus unable to gain access to Thr-330 (or Ser-330) in its assembled topology. Even if any nascent S1 were to be exposed to the cytosol prior to incorporation into the lipid bilayer, the inability of T330A or the phosphomimetic T330D mutant to reach the cell surface makes a role for (de)phosphorylation highly unlikely.

A more simple and plausible explanation for our data is that Thr-330 mediates specific interactions that rely upon hydrogen bonding and steric factors. From structural studies placing the tip of S1 close to the lipid-protein interface (8, 21, 39), it is conceivable that Thr-330 interacts with phospholipid head groups (39-41). However, although threonine is a residue often found at the highly charged membrane-water interface (39), so is alanine and other residues whose presence fails to traffic kv1-4 to the cell surface. Such a model also fails to explain why surface expression is seen in the T330S but not the T330S, E502D mutant, not least as Glu-502 is not close to the lipid surface (6-8, 21).

Consequently, we suggest a model where Thr-330 mediates a protein-protein interaction, which, based on the structure of the closely related Kv1.2 channel (6-8, 21), is most likely to involve extensive hydrogen bonding with a region involving outer pore residues in the S5-S6 linker in an adjacent monomer (Fig. 9). Assuming that Thr-330 is part of an evolutionarily conserved mechanism, a primary candidate interacting residue with which Thr-330 might dock is an equally conserved glutamate in S5 (Glu-502 in Kv1.4) (Fig. 9), in which the nonconservative mutants, with the partial exception of E502T, fail to reach the cell surface and express currents. Although Glu-502 is important for gating (42, 43), it clearly plays an additional trafficking role. The possibility that these biophysical and trafficking roles may be separable would rationalize why E502T shows partial surface expression but low currents. In addition, the absent or weak currents seen in various Kv1.5 (42) and shaker BΔ (43) channel mutants at the position equivalent to Glu-502 can now be rationalized as a failure in trafficking rather than purely an effect on channel gating (43).

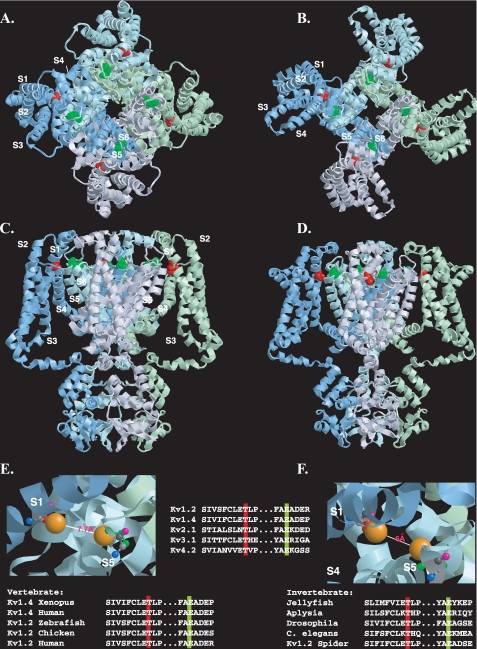

FIGURE 9.

Disposition of the conserved threonine residue within the resting and open state structural models of Kv1.2. A-D, view of the Kv1.2 tetramer in resting (A and C) and open (B and D) state models (7) shown from the extracellular side of the membrane (A and B) or from the side of the membrane (C and D). For clarity, each subunit monomer has been assigned a separate color and displayed schematically. Transmembrane-spanning regions are labeled S1-S6. The conserved threonine (Thr-184) and glutamate (Glu-350) residues (corresponding to Thr-330 and Glu-502 in Kv1.4), are colored red and green, respectively. E and F, close-up view of the putative interlocking region, showing Thr-184 and Glu-350 in ball-and-stick representation for resting (E) and open (F) state models, with side chains (Thr-184, red; Glu-350, green) extended but no α-chain rotation. Oxygen atoms involved in potential hydrogen bonding are shown in orange. Backbone nitrogen, carbonyl oxygen, andα andβ carbons are denoted in blue, pink, light gray, and dark gray, respectively. Top inset, disposition of transmembrane regions colored as follows: S1, yellow; S2, orange; S3, purple; S4, pink; S5, green; S6, blue. Lower insets, evolutionary conservation of the extracellular threonine and glutamate residues colored according to the scheme described in A-D. Modeling was done using RasTop, a Windows interface to RasMol 2.62 (originally written by Roger Sayle). Structural coordinates for the resting and open state were obtained from the supplementary data given in Ref. 7 and correspond to a refinement of the original Kv1.2 crystal structure (6, 21) using the Rosetta-Membrane method and molecular dynamics simulations.

Support for a functional Thr-330 -Glu-502 interaction comes from our ability to restore, at least partially, channel surface expression by mutating Thr-330 to a lysine, thereby engineering an electrostatic bridge to Glu-502. The failure of this eYFP-Kv1.4:T330K mutant to inactivate is, in itself, remarkable and significant. In WT Kv channels, inactivation is thought to proceed via two mechanisms: the first, N-type inactivation, conforms to the now classic “ball and chain” model (44) and involves the amino terminus (45), whereas the second, C-type inactivation, involves residues in the outer pore mouth (46). Although addition of an amino-terminal eYFP slows N-type inactivation, carboxyl-terminal inactivation is retained (23, 25, 26). Even though the relative contributions of N- and C-type inactivation have not been determined in eYFP-Kv1.4, the failure of eYFP-Kv1.4:T330K to inactivate at all indicates that effects induced by mutation at Thr-330 of the voltage-sensing domain can be transmitted to the gating domain.

Any direct, physical interaction between Thr-330 and Glu-502 would appear to be quite stringent structurally, as double mutants, where potential interacting residues are swapped (i.e. T330E,E502T) or where their side chains possess conserved properties but are smaller in size (i.e. T330S,E502D) than those in the WT, localize to the ER. Moreover, although Thr-330 and Glu-502 could simply form parts of larger docking modules, most of the residues flanking Thr-330 or Glu-502 are not well conserved, especially between species (Fig. 9), and their mutants can be expressed as functional channels at the cell surface (17). Consequently, regardless of whether Thr-330 and Glu-502 are physically as well as functionally coupled, their effects are likely to depend upon their overall electron distribution and topology.

Precisely what role the S1-S2 and S5-S6 linker interactions might play is unclear. The restriction of the conserved threonine residue to Kv channels, but not the first or last domains of the four-domain voltage-gated sodium and calcium channels, indicates a role specific to the tetrameric Kv channels. Based on the Kv1.2 crystal structure it has been suggested that the tip of S1 interacts with S5-p, the “turret” region linking S5 and the pore helix, representing one of the few points of contact between the voltage-sensing (S1-S4) and pore-gating (S5-S6) domains (21). More detailed insights into possible interactions between Thr-330 and Glu-502 (or other residues in S5-p) can be drawn from the powerful modeling and labeling techniques applied recently to resolve apparently conflicting data on the motions and interactions of the voltage-sensing and gating domains as the channel makes its transition from the closed to the open state (7). Based upon the data coordinates for the resulting models (7), we predict that the side chain oxygen atoms of residues Thr-184 and Glu-350 in Kv1.2 (equivalent to Thr-330 and Glu-502 in Kv1.4) are separated by 11 and 15 Å in the channel open and closed states, respectively (Fig. 9, A-D). Although greater than the 3.7 Å required for extended hydrogen bond formation, these values are reduced considerably upon flexion of the Thr-184 and Glu-350 side chains (6.0 and 7.0 Å, open and closed states, respectively) (see Fig. 9, E and F). Further rotations, of the type envisaged to occur during outward movement of positively charged S4, could bring Thr-184 and Glu-350 into contact distance (43, 47). Alternative or even additional conserved S5-p residues with which Thr-184 (Kv1.4:T330) might hydrogen bond are limited, but from the recent “paddle chimera” (8) and Pathak (7) models, could include Ser-360 (Kv1.4:S512). Regardless of the precise residues, any interaction of Thr-330 with the S5-p region would be a powerful mechanism for stabilizing the predicted large scale conformational motions of the voltage sensors of each monomer with the gating domains of their adjacent partners on channel opening.

From the profound effect of the threonine mutants on surface expression, corroborated using three independent techniques, we suggest that the stabilization and registration of intersubunit interactions afforded by Thr-330 may be a requisite for the operation of those downstream nonconserved outer pore residues in S5-p, reported as necessary for glycosylation and/or ER-cell surface progression (14, 18, 19, 49, 50). Indeed, it is notable that the S5-p residues with which Thr-330 is predicted to interact (Glu-502 and possibly Ser-512), each flank the “a” region determinant identified by Zhu et al. (49) as necessary for trafficking. Any S1-S2 linker/S5-p interactions would represent an elegant fail-safe mechanism conferring surface expression upon just those channels containing the interlocked voltage-sensing and gating domains of a functional, tetrameric channel. Regardless of its precise role, the ability of a single extracellular residue to support surface expression is remarkable but is substantiated by the high degree to which this residue is conserved across, and restricted to, Kv subfamilies and also within organisms spanning the evolutionary spectrum (48) (Fig. 9, bottom row).

Supplementary Material

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1-S3.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: ER, endoplasmic reticulum; BAPTA, 1,2-bis(O-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid; eYFP, enhanced yellow fluorescent protein; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; FBS, fetal bovine serum; mRFP, monomeric red fluorescent protein; HEK, human embryonic kidney; HA, hemagglutinin; GFP, green fluorescent protein; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; pF, picofarad(s); WT, wild type.

Numbering refers to position in reported (non-tagged) Kv sequence.

References

- 1.Gutman, G. A., Chandy, K. G., Grissmer, S., Lazdunski, M., Mckinnon, D., Pardo, L. A., Robertson, G. A., Rudy, B., Sanguinetti, M. C., Stühmer, W., and Wang, X. (2005) Pharmacol. Rev. 57 473-508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lai, H. C., and Jan, L.Y. (2006) Nat. Neurosci. 7 548-562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delisle, B. P., Anson, B. D., Rajamani, S., and January, C. T. (2004) Circ. Res. 94 1418-1428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manganas, L. N., Akhtar, S., Antonucci, D. E., Campomanes, C. R., Dolly, J. O., and Trimmer, J. S. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 49427-49434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ottschytsch, N., Raes, A., Van Hoorick, D., and Snyders, D. J. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99 7986-7991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Long, S. B., Campbell, E. B., and MacKinnon, R. (2005) Science 309 897-903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pathak, M. M., Yarov-Yarovoy, V., Agarwal, G., Roux, B., Barth, P., Kohout, S., Tombola, F., and Isacoff, E. Y. (2007) Neuron 56 124-140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Long, S. B., Tao, X., Campbell, E. B., and MacKinnon, R. (2007) Nature 450 376-382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pfaffinger, P. J., and DeRubeis, D. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270 28595-28600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Misonou, H., and Trimmer, J. S. (2004) Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 39 125-145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tu, L. W., Wang, J., Helm, A., Skach, W. R., and Deutsch, C. (2000) Biochemistry 39 824-836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trimmer, J. S. (1998) Methods Enzymol. 293 32-49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watanabe, I., Zhu, J., Sutachan, J. J., Gottschalk, A., Recio-Pinto, E., and Thornhill, W. B. (2007) Brain Res. 1144 1-18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manganas, L. N., Wang, Q., Scannevin, R. H., Antonucci, D. E., Rhodes, K. J., and Trimmer, J. S. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98 14055-14059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li, D., Takimoto, K., and Levitan, E. S. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 11597-11602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tombola, F., Pathak, M. M., and Isacoff, E. Y. (2006) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 22 23-52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li-Smerin, Y., Hackos, D. H., and Swartz, K. J. (2000) J. Gen. Physiol. 115 33-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi, G., and Trimmer, J. S. (1999) J. Membr. Biol. 168 265-273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu, J., Watanabe, I., Poholek, A., Koss, M., Gomez, B., Yan, C., Recio-Pinto, E., and Thornhill, W. B. (2003) Biochem. J. 375 769-775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shih, T. M., and Goldin, A. L. (1997) J. Cell Biol. 136 1037-1045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Long, S. B., Campbell, E. B., and MacKinnon, R. (2005) Science 309 903-908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stuhmer, W., Ruppersberg, J. P., Schroter, K. H., Sakmann, B., Stocker, M., Giese, K. P., Perschke, A., Baumann, A., and Pongs, O. (1989) EMBO J. 8 3235-3244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jugloff, D. G., Khanna, R., Schlichter, L. C., and Jones, O. T. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 1357-1364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKeown, L., Robinson, P., Greenwood, S. M., Hu, W., and Jones, O. T. (2006) BMC Biotechnol. 2006, 6: 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kupper, J. (1998) Eur. J. Neurosci. 10 3908-3912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burke, N. A., Takimoto, K., Li, D., Han, W., Watkins, S. C., and Levitan, E. S. (1999) J. Gen. Physiol. 113 71-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohapatra, D. P., and Trimmer, J. S. (2006) J. Neurosci. 26 685-695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaw, G., Morse, S., Ararat, M., and Graham, F. L. (2002) FASEB J. 16 869-871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones, V. C., McKeown, L., Verkhratsky, A., and Jones, O. T. (2008) BMC Neurosci. 2008, 9: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mura1, C. V., Cosmelli, D., Munõz, F., and Delgado, R. (2004) J. Membr. Biol. 201 157-165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones, H. M., Hamilton, K. L., and Devor, D. C. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 37257-37265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kreusch, A., Pfaffinger, P. J., Stevens, C .F., and Choe, S. (1998) Nature 392 945-948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Critz, S. D., Wible, B. A., Lopez, H. S., and Brown, A. M. (1993) J. Neurochem. 60 1175-1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brooks, N. L., Corey, M. J., and Schwalbe, R. A. (2006) FEBS J. 273 3287-3300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma, D., Zerangue, N., Lin, Y. F., Collins, A., Yu, M., Jan, Y. N., and Jan, L. Y. (2001) Science 291 316-319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stockklausner, C., Ludwig, J., Ruppersberg, J. P., and Klöcker, N. (2001) FEBS Lett. 493 129-133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deutsch, C. (2003) Neuron 40 265-276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goder, V., Crottet, P., and Spiess, M. (2000) EMBO J. 19 6704-6712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Granseth, E., von Heijne, G., and Elofsson, A. (2005) J. Mol. Biol. 346 377-385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hong, K. H., and Miller, C. (2000) J. Gen. Physiol. 115 51-58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmidt, D., Jiang, Q. X., and Mackinnon, R. (2006) Nature 444 775-779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eduljee, C., Claydon, T. W., Viswanathan, V., Fedida, D., and Kehl, S. J. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. 292 C1041-C1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ortega-Sáenz, P., Pardal, R., Castellano, A., and López-Barneo, J. (2000) J. Gen. Physiol. 116 181-190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Armstrong, C. M., and Bezanilla, F. (1977) J. Gen. Physiol. 70 567-590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoshi, T., Zagotta, W. N., and Aldrich, R. W. (1990) Science 250 533-538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoshi, T., Zagotta, W. N., and Aldrich, R. W. (1991) Neuron 7 547-556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Larsson, H. P., and Elinder, F. (2000) Neuron 27 573-583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu, F. H., Yarov-Yarovoy, V., Gutman, G. A., and Catterall, W. A. (2005) Pharmacol. Rev. 57 387-395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu, J., Watanabe, I., Gomez, B., and Thornhill, W. B. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 25558-25567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Watanabe, I., Zhu, J., Recio-Pinto, E., and Thornhill, W. B. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 8879-8885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marks, M. S., Woodruff, L., Ohno, H., and Bonifacino, J. S. (1996) J. Cell Biol. 135 341-354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.