Abstract

Background

The patient–doctor relationship is an important but poorly defined topic. In order to comprehensively assess its significance for patient care, a clearer understanding of the concept is required.

Aim

To derive a conceptual framework of the factors that define patient–doctor relationships from the perspective of patients.

Design of study

Systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies.

Method

Medline, EMBASE, PsychINFO and Web of Science databases were searched. Studies were screened for relevance and appraised for quality. The findings were synthesised using a thematic approach.

Results

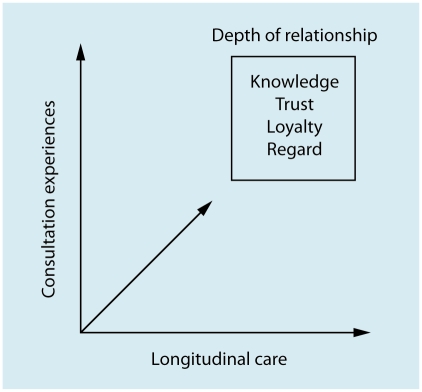

From 1985 abstracts, 11 studies from four countries were included in the final synthesis. They examined the patient–doctor relationship generally (n = 3), or in terms of loyalty (n = 3), personal care (n = 2), trust (n = 2), and continuity (n = 1). Longitudinal care (seeing the same doctor) and consultation experiences (patients' encounters with the doctor) were found to be the main processes by which patient–doctor relationships are promoted. The resulting depth of patient–doctor relationship comprises four main elements: knowledge, trust, loyalty, and regard. These elements have doctor and patient aspects to them, which may be reciprocally related.

Conclusion

A framework is proposed that distinguishes between dynamic factors that develop or maintain the relationship, and characteristics that constitute an ongoing depth of relationship. Having identified the different elements involved, future research should examine for associations between longitudinal care, consultation experiences, and depth of patient–doctor relationship, and, in turn, their significance for patient care.

Keywords: communication, continuity of patient care, physician–patient relations, qualitative research

INTRODUCTION

The patient–doctor relationship is an important concept in health care, especially primary care. However, it is also a complex topic that means different things to different people. As a consequence of this, research in the area has been somewhat fragmented.

Many studies have investigated it in terms of the communication and interpersonal skills of the doctor.1–4 Another major facet is continuity of patient care, where the relational aspect is referred to as interpersonal continuity.5–7 More recently there has been interest in examining the characteristics of the ongoing relationship itself, such as trust.8 The patient–doctor relationship can be seen as a specialised form of human relationship, and work in other disciplines has distinguished between the dynamic interactive aspects of relationships and the mental associations made by people ‘in’ relationships, which are ‘historically derived representations of experience’.9 All of these elements are thought to be important, but in the absence of a conceptual framework that can be applied to patient–doctor relationships, we are unlikely to establish the significance of the different parts and how they affect patient care.

Broadly speaking, the patient–doctor relationship can be viewed as either a process or an outcome, and opinion on which is most appropriate is divided.1 Although the purpose or function of the relationship is likely to vary according to the perspective of the observer,10 clinical imperatives emphasise its value as a component of the care process that might improve health outcomes. A better understanding of those aspects of patient–doctor relationships that affect patient care is required, because it has implications for how doctors are trained and health care is organised. If continuity, for example, makes a unique contribution to patient–doctor relationships, then it may be unwise to pay excessive attention to doctors' communication skills in isolated consultations; instead greater emphasis on organisational systems that promote continuity may be appropriate.

In the absence of good conceptual frameworks to guide research into patient–doctor relationships,11 the authors decided to undertake a synthesis of the published qualitative literature on patients' views of patient–doctor relationships. Qualitative studies are suited to investigating poorly understood or complex issues, and there is an extensive qualitative literature on patient–doctor relationships, yet the findings have not been drawn together using synthesis techniques. The aim of this study was to map out the key components of the patient–doctor relationship as viewed by patients, to ascertain what they are and how they might interrelate.

METHOD

Identification of relevant studies

The guiding definition for the search was: papers using qualitative methodology whose main focus is how patients experience and evaluate patient–doctor relationships. The Medline, EMBASE, PsychlNFO, and Web of Science (Science Citation Index Expanded, Social Sciences Citation Index and Arts & Humanities Citation Index) databases were searched from inception until early January 2008. The search strategy (Appendix 1) was informed by a prior scoping exercise.12

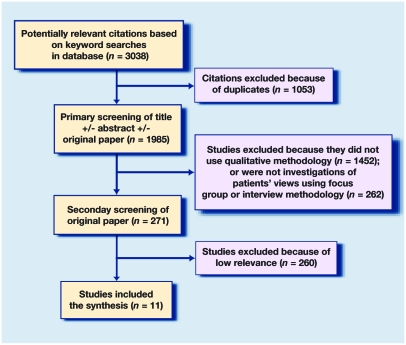

Duplicate citations were excluded and the primary and secondary screening of the remaining publications was undertaken (Figure 1). Most citations were screened on the basis of their title or abstract, but if more detail was required the original paper was obtained.

Figure 1.

Study inclusion/exclusion process.

In the primary screen qualitative research on patients' views of the patient–doctor relationship using focus groups or interviews were identified. In the secondary screen, the citations were examined for relevance.

The research aimed to obtain a generic understanding of ongoing patient–doctor relationships. Studies were included if they were general investigations of patient–doctor relationships in medical or surgical settings (primary/ambulatory or secondary care); they were excluded if they were restricted by the characteristics of the patient (sex, age, or ethnicity), and/or problem (for example, a specific diagnosis or issue), and/or visit (focus on a single consultation). As an example, a study of HIV prevention in black men who have sex with men, which flagged the importance of their relationship with primary care providers, was excluded. By contrast, a study that examined trust in 40 patients of different sex, age, and ethnicity was included.

How this fits in

The patient–doctor relationship is thought to be important, but research demonstrating its value has been hampered by a lack of clarity about what is meant by the term. Drawing on published qualitative studies with patients, two key aspects are identified: factors that develop or maintain the relationship (longitudinal care and patients' consultation experiences), and factors that characterise an ongoing depth of relationship (knowledge, trust, loyalty, and regard). Further work is required to substantiate the distinctiveness of these elements, how they influence one another, and their significance for patient care.

Full text copies of the remaining articles were independently assessed and, through discussion, agreed which should be included in the synthesis. Quality appraisal of qualitative research is a contentious issue,13 but the final 11 studies were assessed using a framework based on the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme quality-assessment tool for qualitative studies.14

Analysis

It was decided to perform a thematic synthesis,12 which allows clear identification of prominent themes, and provides an organised, structured, and yet flexible, way of dealing with the articles under these themes.15 Where studies interviewed patients and healthcare team members, only sections on patients' views were included. Two researchers independently read the selected papers, focusing on the findings and discussion sections, and identified themes. However, they were from different professional backgrounds and undertook the analysis in alternative ways.

The first researcher was a GP with prior experience of conducting research on continuity and interpersonal care. The researcher approached the studies with a particular interest in identifying how the patient–doctor relationship was described in terms of communication skills, continuity, and ongoing relationship characteristics such as trust. Atlas.ti (version 5.0, Scientific Software) was used to aid the analysis, using electronic copies of the articles as primary documents. After reading and re-reading each document codes were attached to sections of text relating to different aspects of patient–doctor relationships. A detailed indexing system was employed, which meant applying multiple codes to sections of text, even if it was suspected that any differences were minor. All codes were given a working definition to ensure that they were used consistently. It was an iterative process, so the codes evolved over repeated readings of the articles.

The second researcher was a social scientist who was broadly familiar with the patient–doctor relationship literature. This researcher did not approach the data with an explicit prior framework, seeking instead to identify emergent themes from the articles.15 The researcher worked from hard copies of the papers, manually coding the data for different aspects of the patient–doctor relationship, and grouping the findings into broader categories and themes. By comparing and discussing the codes and concepts identified, the two researchers agreed the final themes to include in the synthesis.

RESULTS

From 1985 abstracts, 11 were included in the synthesis (Figure 1). As the search strategy had a low specificity for qualitative papers, the majority were rejected on the grounds that they were not qualitative. No studies were rejected because of serious concerns about methodological quality (Appendix Table 2).

The characteristics of the final 11 studies included in the synthesis16–26 are summarised in Table 1. The aims, participants and key findings are summarised in Table 2. The studies were conducted in four countries – the US (n = 5), UK (n = 3), Canada (n = 2), and Sweden (n = 1) – and some included participants who were doctors, nurses, or other practice staff, rather than patients. Patients varied from 18 to 84 years old. Three studies examined patient–doctor relationships in a general sense.16–18 The other eight explored the topic from one of four closely related perspectives: personal care,19,20 continuity of patient care,21 loyalty,22–24 and trust.25,26

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies in the literature synthesis.

| Methodology | Participants | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Country | Topic | Interviews | Focus group | Patients | Doctors | Other |

| Brown et al22 | Canada | Loyalty | • | • | |||

| Gabel et al23 | US | Loyalty | • | • | |||

| Goold and Klipp25 | US | Trust | • | • | |||

| Gore and Ogden16 | UK | General | • | • | |||

| Lings et al11 | US | General | • | • | • | •b | |

| Pandhi et al21 | US | Continuity | • | • | |||

| Roberge et al24 | Canada | Loyalty | •a | • | • | ||

| Tarrant et al19 | UK | Personal care | • | • | • | • | •b,c |

| Thom and Campbell26 | US | Trust | • | • | |||

| Von Bültzingslöwen et al20 | Sweden | Personal care | • | • | • | ||

| Wiles and Higgins18 | UK | General | • | • | |||

Conducted in French.

Nurses.

Practice administrative staff.

Table 2.

Summary of study aims, participants, and key findings.

| Study | Aims | Participantsa | Key findingsa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brown et al22 (Appendix 3) | ‘What factors contribute to patients' long-term attendance at a family practice teaching unit?’: to explore the ideas, opinions, feelings, and experiences of patients attending the centre and to examine their reasons for continued attendance | 42 patients (unknown sex, 31–84 years old, unknown ethnicity). Patients were purposefully selected to have received care primarily from a staff physician, a resident, or both. They had been affiliated with one of three practices for ≥15 years | Four key themes were identified as the primary factors contributing to long-term attendance: the relationship context (patient as a person; relationship-building processes; and relationships with specific team members), the team concept, professional responsibility, and attitudes, and comprehensive and convenient care |

| Gabel et al23 (Appendix 4) | ‘What characteristics of physicians and practices promote long-term care relationships with patients?’: to gain insight into the meaning patients attach to continuity of care | 60 patients (unknown sex, ≥35 years unknown ethnicity). Recruited 15 patients per physician, who had seen the same family physician for a minimum of 15 consecutive years and who were ≥35 years. | The main factors identified as contributing to long-term relationships were: patient familiarity with the physician (including knowing what to expect with them), physician knowledge of the patient (accumulated knowledge about the patient's medical history, work, lifestyle, habits and stresses, and the patient's family), and patient confidence in the physician (‘that resulted from satisfactory scare received over many years’) |

| Goold and Klipp25 (Appendix 5) | To explore consumer expectations and experiences in managed health plans. The report however ‘focuses on the role of trust in members' perceptions and experiences of managed care, a topic that participants spontaneously raised during the study’ | 26 male and 14 female, 25–71 years, 20 white, 12 African-American, 3 Hispanic, 2 Indian, 2 Arab,1 mixed. Selectively sampled through area employers (11), community-based in organisations (14), personal contacts (11), via other interviewees (3), and unknown | Goold and Klipp distinguish between experientially based trust in a specific doctor (trust in my physician) and trust physicians in general. Trust in my physician: the two major themes were history and communication. Other themes were: competence/positive outcomes, advocacy, vulnerability, caring/compassion, and respect. Trust in physicians in general: comments were based less on relationships and more on ethics (distrust expressed as the consequence of bad experience; and trust based on beliefs and assumptions about doctors) |

| Gore and Ogden16 (Appendix 6) | To examine patients' views of the process of creating a relationship with their GP | 9 men and 18 women, 30–79 years old, ‘mixed’ ethnicity. Recruited from four practices. Patients had to have been registered for 2 years and to have attended at least six times per year during this period | Describes the relationship in terms of development, validation, and consolidation stages. They conclude that each consultation is not an isolated event and that patients are active agents in their relationship with their doctors |

| Lings et al17 (Appendix 7) | To describe, conceptualise and explain patients' and doctors' experiences and behaviour with regard to the therapeutic relationship | 24 females and 10 males, unknown ages, 12 from ‘ethnic minorities’. ‘Randomly sampled’ from family medicine centre | They describe three key factors in patient–doctor relationships: ‘asymmetrical’ communication; the importance on both sides of ‘liking’; and the value set by both parties on development of trust. Continuity of relationships may promote the development of trust and liking, and make patients more tolerant of a doctor's mistakes |

| Pandhi et al21 (Appendix 8) | To examine how patients perceive a continuity of patient–doctor relationship in a family medicine setting, from its development through to its consequences | 8 females and 6 males, 25–62 years old, unknown ethnicity. Theoretically selected from random sample of 40 eligible patients of a family medicine residency. Poor–excellent health | Rather than describing ongoing patient–doctor relationships in terms of ‘continuity of care’ per se, Pandhi et al found that patients talked about the importance of establishing and maintaining a comfortable relationship |

| Roberge et al24 (Appendix 9) | ‘To define the notion of loyalty to the attending physician’: to document and compare the vision that patients and physicians in the Montreal region have of loyalty to the regular care provider | 16 females and 7 males, 27–72 years old, unknown ethnicity. Recruited through advertisement | Patient–doctor loyalty may be viewed as a contract, agreement, or commitment. It primarily depends upon patient trust, and it means that the patient sees the same doctor for the majority of their health needs. However, patient loyalty is neither exclusive nor permanent. Patient loyalty was firstly to the doctor, not the clinic |

| Tarrant et al19 (Appendix 10) | To explore patients' perceptions of the features of personal care and how far these are shared by healthcare providers; whether a continuing relationship between a health professional and a patient is essential for personal care; and the circumstances in which a continuing relationship is important | 25 females and 15 males, aged ≥18 years, 29 white, 9 Asian, 2 African-Caribbean; 25 had chronic or multiple health problems. Recruited from six general practices | Personal care was described in terms of: human communication, individualised treatment or management, and whole-person care (treatment in the context of the patient's life and family history). Whatever the context, human communication and individualised care are important in making care personal. A continuing provider-patient relationship promotes, but does not guarantee, personal care |

| Thom and Campbell26 (Appendix 11) | To gain an understanding of how patients perceive trust of a physician and how patients relate physicians' behaviours to their perceptions of trust | 20 female and 9 male, 23–72 years old. Recruited from a university-based family practice (6 long-time patients, 10 recruited from a list of 43 randomly sampled patients who had visited the office within the previous 6 months), a family practice residency clinic (4 recruited froma random sample of 54 English-speaking Hispanic patients who had visited within the last 56 months), and the remainder by flyersposted in a publicly supported medical clinic | Three global factors that influence patient trust were described: physician behaviours, predisposing factors, and structural/staffing factors. Patients seem to distinguish between physician behaviours that are primarily interpersonal and those that are technical. There may be a discernible difference in patient's minds between trust in, and satisfaction with, a physician |

| Von Bültzingslowen et al20 (Appendix 12) | To acquire a comprehensive understanding of the core values of having a personal doctor in a continuing patient–doctor relationship in primary care among patients with a long-term chronic illness | 9 female and 5 male, 33–79 years old, unknown ethnicity. Recruited from three primary healthcare centres. Patients had to have: visited the healthcare centre for at least 5 years; have any long-term chronic disease (such as diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, coronary heart disease, depression, or lower back pain); and have experienced personal and short-term locum doctors | Many patients described the impact of having a personal doctor in terms of a core sense of security. The basis of this security was: coherence, confidence in care, a trusting relationship, and accessibility. The authors suggest that personal care is promoted by, but not always dependent on, a continuing provider-patient relationship |

| Wiles and Higgins18 (Appendix 13) | To examine how private patients interpret and understand their relationships with their doctors. In particular, ‘whether patients understand the relationship with their consultants to be a consumerist one, in which they hold the power, one of mutuality, or the more traditional paternalistic one’ | 35 female and 25 male. Majority aged 25–50 years and in social classes I, II, or III. 30 paid for their stays through private health insurance provided or subsided by their employers. Recruited from 8 private hospitals and pay beds in 3 NHS hospitals | Some patients thought that the direct or indirect exchange of money influenced the nature of the relationship in some cases, for example ‘buying time’ with their consultants. Many patients characterised their relationships as one of friendship, which they attributed to the greater frequency with which they saw the same doctor, or the length of time over which contacts had occurred. Others thought the ‘congenial surroundings and positive atmosphere’ of the private hospitals enhanced communication |

Where informants other than patients were recruited, characteristics of patient participants and findings attributed to patients only are summarised.

The analysis of the included studies identified two overarching themes, each with several elements: the development and maintenance of patient–doctor relationships, and the ongoing depth of the patient–doctor relationship.

Development and maintenance of patient–doctor relationships

The processes by which patient–doctor relationships appear to be developed and maintained can be described in terms of longitudinal care and consultation experiences.

Longitudinal care

Seeing the same doctor, or longitudinal care, was identified as a key process in developing and maintaining patient–doctor relationships.16–21,23–25 Longitudinal care was central to many accounts of personal care experienced by patients in Tarrant et al's study.19 Roberge et al suggested that regularity, rather than frequency, of contact is of greater importance.24

It is important that patients are able to retain some choice regarding who they see, because longitudinal care on its own does not guarantee a depth of relationship.19,20,24,25 It is the quality of patient–doctor encounters that has a major bearing on how the patient–doctor relationship is both developed and maintained.

Consultation experiences

The focus of the majority of studies was patients' personal experience with doctors during consultations, for themselves or family members.16,17,19–21,23–26 Patients seem most likely to form a relationship with a doctor who meets their expectations or needs. Although some patients' initial expectations may be met by virtue of the doctor's sex or age,16,21,26 the key means by which this occurs are the doctor's consultation skills.

Patients want doctors who appear interested, listen well, explain clearly, are open to discussion, and involve the patient in decision making, if it is desired.16,17,19–26 Patients cited actions – for example, the way in which the doctor questioned or examined them – that suggested thoroughness and a caring attitude. ‘Human communication’ may include social talk or ‘chit chat’, and appropriate use of humour.18,19,21 Lings et al's idea of ‘asymmetry of perception’ seems to recognise that patients and doctors have different roles and responsibilities within a relationship.17,23 Some patients may choose to test these and other patient–professional boundaries.16 Although it may be important that the patient communicates as well as they are able,24 from the patient's perspective the emphasis is always on the doctor to facilitate this process.

A closely related element that contributes to the development and maintenance of patient–doctor relationships is time.17–21,23 The studies highlighted the importance patients placed on not feeling hurried, and their appreciation of doctors who ‘had time’.19 Lings et al reported that listening was characterised by the sense of being able to talk things over without feeling that time was a critical issue.17

Another aspect of patients' views on how their relationships with doctors develop or are maintained concerns indirect experience: the outcome of problems shared and the opinions of friends or family. A patient–doctor relationship may be deepened or destroyed by good or bad clinical outcomes respectively.16,21,23–26 Word of mouth, positive or negative, about a doctor's behaviour or practice may reinforce or challenge a patient's opinion of a doctor.16,23

Patient–doctor encounters may also be affected by factors at the practice level. For example, being met by friendly reception staff may mean the patient goes into the consultation in a more positive frame of mind.19,21,26 Wiles and Higgins noted how the congenial surroundings and ‘positive atmosphere’ of private hospitals may enhance a patient's communication with their doctor.18

Depth of patient–doctor relationship

In addition to the processes by which patient–doctor relationships are developed and maintained, the studies suggested that depth of relationship, as a product of longitudinal care and consultation experiences, was important. This encompassed four main elements: knowledge, trust, loyalty, and regard. These elements reflect patients' enduring views about their relationship with the doctor outside of consultations. They appear to be the ongoing product of the dynamic aspects of the relationship.

Knowledge

Knowledge emerged as a dominant aspect contributing to depth of relationship.16,17,19–23,25,26 Studies described both patients' knowledge of the doctor, and doctors' knowledge and understanding of the patient.

Many patients like ‘knowing’ the doctor.16,20,23,25 This might start with a simple familiarity with what they look like, but may develop into more personal knowledge, for example, concerning the doctor's personality. Of particular importance is the idea that the patient knows or anticipates how the doctor will behave or react.20,23

Similarly, with respect to the doctor's knowledge of the patient, the starting point is basic physical familiarity (putting a name to a face), but also knowledge of the patient's medical history.19–23,25 Patients value these aspects for two reasons – because the doctor is able to see changes in their appearance and hence possibly their health, and because there is a sense of shared history. Patients dislike having to repeat information: they may find it difficult, or feel they do not have enough time to put everything into words every time they see a new doctor.

At a deeper level, the doctor accumulates personal knowledge about the patient, such as their background (including family and social circumstances) and their expectations.17,19–23,25,26 This contributes to a patient feeling understood and treated as an individual in the context of their life and illness, rather than just the presenting problem. Patients perceive that the doctor has achieved a deeper understanding of them at an emotional or personal level. Some studies referred to patients within ‘good’ patient–doctor relationships as experiencing empathy and holistic care.19–22

Holistic care was more commonly described as occurring in longer-term relationships.20,22 However, von Bultzingslowen et al identified several patients who felt understood in single consultations or short-term relationships, and one patient who complained about a lack of empathy with their ‘personal doctor’ who had been known for some time.20

Trust

Patients' trust in the doctor was another prominent aspect of the depth of patient–doctor relationships.16,17,19–26 Unlike knowledge, however, trust may start at a generic level of ‘trust in doctors in general’, which may be refined (usually deepened), in terms of a personal ‘trust in my doctor’; that is, in the absence of bad experience, patients usually assume that doctors are trustworthy.20,25

Goold and Klipp reported how patients' comments about doctors in general were more abstract than their comments concerning a specific doctor.25 For some patients, trust in their doctor may remain ‘blind’,25 but for the majority, trust in a specific doctor was rooted in experience.16,19,20,21 Patients used words such as ‘confidence’, ‘faith’, ‘security’, and ‘competence’. Patients' trust was based at least partly on their views of doctors' openness and honesty, including doctors recognising the boundaries of their own abilities, and their readiness to refer on to others.22,23

Patients' perceptions of their doctor's trust in them were associated with feelings of being believed;20 they may feel mistrusted if their symptoms are minimised or not taken seriously.

Loyalty

Roberge et al's study of loyalty defined it in terms of a contract or agreement between the patient and the doctor.24 Loyalty is closely associated with, yet distinct from, longitudinal care.20,22,24 For a given doctor, longitudinal care describes a patient's pattern of visits over time, whereas the loyalty aspect of the depth of the patient–doctor relationship describes the patient's preference for seeing that particular doctor.

Patients' preferences may be shaped by their past experiences and their presenting problem. Discontinuity of a physician may be less of an issue for patients who are used to it; this is suggested by Brown et al's study, whose participants differed from those in other studies because they regularly saw new doctors rotating through their health centre as part of their training programme.22 In addition, patients' preferences regarding who they see may depend on the problem with which they are presenting.19–21,24 Patients generally preferred to see the same doctor when dealing with long-term, complex, or emotional problems.19 However, they may be happy to see any doctor for minor problems, ‘any doctor but my usual doctor’ for embarrassing problems, and a specific doctor for a specific problem.16,19,25,27

Patient loyalty is also measured in terms of their tolerance of unsatisfactory aspects of care.16,17,21 Lings et al called this a satisfaction paradox, a ‘seemingly contradictory phenomenon, whereby patients express dissatisfaction with certain procedures or events but still maintain a positive relationship’.17 Examples of such dissatisfaction relate to characteristics of the practice (distant location, problems with the appointment system) and the doctor (running late, poor availability, unsatisfactory consultations, failing to return phone messages).16,21,23 Patients who have developed a relationship with a doctor ‘appear able to accept and tolerate less than optimum care if the usual care is good and satisfactory – that is, they seem to ‘forgive’ the doctor an occasional lapse’.17

In turn, a doctor's actions may be perceived by patients as a marker of their loyalty to them.16,17,22 Gore and Ogden gave an example of how a doctor remained committed to a patient despite their obviously deceitful behaviour.16

Regard

This final aspect of the depth of patient–doctor relationships is a primarily affective attribute. It comprises comfort17,21 and liking,16,17,23 which reflect perceived care from the doctor and respect in the relationship.20–22,24,25 As a consequence of doctors appearing interested and ‘on side’ with patients, patients feel that they matter to the doctor.

On the basis of their data, Lings et al defined liking as ‘having an easy and comfortable relationship with the doctor’.17 Some patients likened a good patient–doctor relationship to a friendship.18,23 Gabel, et al reported: ‘For some, friendship was a reciprocal relationship with both parties perceived to feel the same bond. The relationship was characterised as warm, caring, or comfortable. There was a feeling of closeness that was a result of knowing each other for a long period of time’.23

Relationships between longitudinal care, consultation experiences, and depth of relationship

The relationships between, and distinctiveness of, the different elements of longitudinal care, consultation experiences, and depth of relationship may vary. Some patients may decide in a single consultation (during or after a positive consultation experience), that they like (regard) that doctor, and cite this as a reason to seek longitudinal care with them in the future.19,21 However, because patients have different needs – they interact with the doctor within the context of their unique problem, expectations, and so on – depth of relationship may develop by different routes. For instance, the relationship may deepen more rapidly during a crisis in the patient's life, especially if the doctor demonstrates advocacy or makes an extra effort to help them through a problem.16,22,25

Some aspects of the depth of patient–doctor relationships may be more closely related to either longitudinal care or consultation experiences, yet it is likely that longitudinal care and consultation experiences have synergistic effects. For example, although longitudinal care may facilitate the doctor's accumulation of medical knowledge about a patient, without satisfactory patient–doctor communication, personal knowledge is unlikely to grow.

The distinctiveness of some of the elements identified in this study may be blurred at the margins. For instance, the literature highlights how longitudinal care is the product of a complex interaction between access to a given doctor and the patient's preferences for seeing him or her. Patient loyalty may, therefore, be both the product of, and the driver for, seeing the same doctor.21 Clearly, longitudinal care is affected by a doctor's availability, whatever its determinants,20,23,24,26 and some patients may struggle to maintain a good relationship with their doctor because of lack of availability and appointments.16 Perhaps paradoxically, when physicians acknowledge that patients have consulted other doctors, this may actually build trust.21

DISCUSSION

Summary of main findings

Through a thematic analysis of primary qualitative studies this study has drawn together the data from 11 studies of patients' perspectives to derive a conceptual framework that helps us to understand the complex topic of patient–doctor relationships (Figure 2). Two major elements have been identified (longitudinal care and consultation experiences) that contribute to the development and maintenance of patient–doctor relationships. As a consequence of these dynamic processes, an ongoing depth of relationship may be established. This is characterised by four main elements: knowledge, trust, loyalty, and regard. Each of these elements has two sides: the patient's opinion about the doctor, and the patient's perception of the doctor's opinion about them, which may be reciprocal.

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework of the patient–doctor relationship.

This framework implies that having positive consultations with the same doctor over time builds depth in the patient–doctor relationship which, in turn, may promote further longitudinal care. It also recognises that from the patient's perspective, continuity of doctor and consultation factors are linked, yet distinct, aspects. Longitudinal care alone does not guarantee the depth of a patient–doctor relationship and, given the choice, patients are unlikely to seek care from the same doctor if previous experiences have been negative. Finally, longitudinal care and consultation experiences are influenced by the context in which patients and doctors encounter one another.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The authors are not aware of any other syntheses of qualitative literature on the patient–doctor relationship. Qualitative synthesis is still an emergent field, peppered with controversies, and there is no single agreed way of doing it.15 Following the principle set out by Mays et al of establishing a clear purpose to the review at the outset, this study has sought to present a method marked by critical thought, transparency, and explicitness.12

To ensure robustness, the articles were independently read and coded by two researchers. Predictably, there were variations in the labelling of codes, but the themes and elements presented in this article reflect all of the concepts identified by both researchers. In any qualitative research, primary or secondary, the researcher plays a role as ‘research instrument’ and shapes the findings by interpreting them through either explicit or more implicit prior concepts.28 It must be acknowledged that this was inevitably the case in the present synthesis, but the authors believe that the findings are strengthened by their different professional backgrounds and contrasting analytical approaches.

Given the amount of research on patient–doctor relationships, it is perhaps surprising that from 1985 potential articles only 11 studies were finally included in the synthesis. This reduction reflects the strategy used for identifying articles. Searching for relevant studies was a challenge. The keyword ‘doctor–patient relationship’ and its synonyms are loosely defined and applied to a wide range of research. Furthermore, there are recognised problems with identifying published qualitative research.12 Interpretation was necessary at the secondary screening stage when subjective decisions as to which articles should be excluded were made. Broadening the inclusion criteria would have led to the addition of other studies and possibly greater detail within individual themes. However, the findings in the articles included were consistent and having an excessive number of articles can itself cause problems in qualitative synthesis; trading depth for breadth can result in the production of a superficial synthesis.29

Despite the desire to examine the views of patients from general medical settings, it must be acknowledged that the participants in the included studies still represent select groups of patients. The findings, for example, may not necessarily be representative of young, usually healthy, patients who consult with self-limiting problems.

Comparison with existing literature

The framework used encompasses all of the elements of previous quantitative investigations of patient–doctor relationships: longitudinal care,6 communication skills,1,30 knowledge,31 trust,32 empathy,33 and liking.34 The range of issues identified within the themes also fits well with the findings of these earlier studies. For example, similar to the present discussion of trust, the literature on patient–doctor trust has previously discriminated between personal trust (trust in a particular doctor), and social trust (generalised trust in the healthcare system, the medical profession, and/or the patient's practice as a whole).35

Distinguishing between the dynamic, interpersonal processes that occur during consultations and the ongoing quality or depth of relationship is not a new idea – Szasz and Hollender distinguished between function (what the physician does) and the ‘abstract’ relationship in 1956.36 However, to date, research on patient–doctor relationships has focused on the communication and interpersonal skills of the doctor – an isolated interaction between patient and physician that is quite different from a relationship.37

This study's framework addresses two conceptual issues that have dogged research in this area. It distinguishes between longitudinal care and interpersonal care. Relational aspects of continuity are often referred to as interpersonal continuity,5 which is potentially confusing because it combines notions of length and depth of relationship. Additionally, patient–doctor relationship research has sometimes confused knowledge between doctor and patient with the presence of a relationship.6 The present model identifies knowledge as one aspect of the depth of the patient–doctor relationship that has both factual and affective components.

Implications for future research and clinical practice

It is hoped that the framework from this study is helpful to both clinicians and researchers. For doctors, it represents a fresh way of thinking about encounters with patients – both at the individual patient–doctor level and also at an organisational and team level. Doctors need to remember that how practices are run and how primary healthcare members work together can affect the patient–doctor relationship. For researchers, it defines the key factors that need to be considered for future research in this area, and should discourage a piecemeal approach to this complex topic.

Forthcoming studies should look to explore the different elements of longitudinal care, consultation experiences, and depth of relationship in terms of their distinctness, their inter-relationships, and their relative importance in healthcare delivery. Work to date has been mainly cross-sectional in nature and longitudinal studies are required to examine outstanding questions, including what benefits each aspect may bring, if any, and whether they are more important for certain groups of patients, such as those with complex problems be they health and/or socioeconomic.

Viewing the patient–doctor relationship in terms of longitudinal care, consultation experiences, and depth of relationship represents one unifying framework by which to investigate questions about its value for patient care. It is a framework grounded in empirically-derived data from several qualitative studies, which provides an explicit conceptual underpinning for future research in this complex field.

Appendix 1. Database search strategies

| Database and item | Term |

|---|---|

| Medline | |

| 1 | exp Qualitative Research |

| 2 | exp Focus Groups |

| 3 | exp nursing methodology research |

| 4 | exp Tape Recording |

| 5 | qualitative.tw |

| 6 | ethnograph$.tw |

| 7 | interview$.tw |

| 8 | audio-tape$.tw |

| 9 | audio tape$.tw |

| 10 | video-tape$.tw |

| 11 | video tape$.tw |

| 12 | view$1.tw |

| 13 | perception$.tw |

| 14 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 |

| 15 | exp Physician–Patient Relations |

| 16 | relationship.tw |

| 17 | 14 and 15 and 16 |

| 18 | Limit 17 to English |

| PsychINFO | |

| 1 | (qualitative research) or (ethnograph*) or (focus group?) or (interview?) or (audio tape?) or (video tape?) or (view?) or (perception?) |

| 2 | (doctor patient relationship) or (patient doctor relationship) or (physician patient relationship) or (patient physician relationship) |

| 3 | 1 and 2 |

| 4 | Limit 3 to English |

| EMBASE | |

| 1 | exp Qualitative Research |

| 2 | exp Ethnography |

| 3 | exp Interview |

| 4 | exp Tape recorder |

| 5 | exp Video recorder |

| 6 | qualitative.tw |

| 7 | ethnograph$.tw |

| 8 | focus group$1.tw |

| 9 | interview$1 .tw |

| 10 | audio-tape$1 .tw |

| 11 | audio tape$1 .tw |

| 12 | video-tape$1 .tw |

| 13 | video tape$1 .tw |

| 14 | view$1 .tw |

| 15 | perception$1 .tw |

| 16 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 |

| 17 | exp Doctor–Patient Relation |

| 18 | relationship.tw |

| 19 | 16 and 17 and 18 |

| 20 | Limit 19 to English |

| Web of Science | |

| 1 | TS=“qualitative research” |

| 2 | TS =ethnograph* |

| 3 | TS=“focus group$” |

| 4 | TS=interview$ |

| 5 | TS=“audio-tape$” |

| 6 | TS=“audio tape$” |

| 7 | TS=“video-tape$” |

| 8 | TS=“video tape$” |

| 9 | TS=view$ |

| 10 | TS=perception$ |

| 11 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 |

| 12 | TS=“doctor–patient relationship$” |

| 13 | TS=“patient–doctor relationship$” |

| 14 | TS=“physician–patient relationship$” |

| 15 | TS=“patient–physician relationship$” |

| 16 | TS=“doctor patient relationship$” |

| 17 | TS=“patient doctor relationship$” |

| 18 | TS=“physician patient relationship$” |

| 19 | TS=“patient physician relationship$” |

| 20 | 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 |

| 21 | 11 and 20 |

| 22 | 21 English only |

Appendix 2. Template used to aid the appraisal of the studies included in the synthesis.

| Title | Study title |

|---|---|

| Reference | Publication details |

| Authors and institution | Names of authors, status if given, and institution |

| Background | Context of project, if known/relevant |

| Setting | Country and any study specifics |

| Aims | Stated aims of study |

| Research design | Qualitative methodology used |

| Sampling | How participants were sampled and their characteristics |

| Data collection | How data collection was reported to have been done |

| Reflexivity | Any discussion relating to reflexivity |

| Ethical issues | Consideration of ethical issues |

| Data analysis | How data analysis was reported to have been done |

Appendix 3. Long-term attendance at a family practice teaching unit: qualitative study of patients' views.

| Reference | Canadian Family Physician 2007; 43: 901–906 |

|---|---|

| Authors and institution | Judith Belle Brown, assistant professor, Centre for Studies in Family Medicine and the Thames Valley Family Practice Research Unit at the University of Western Ontario, London; Irene Dickie, Lynn Brown, John Biehn, St Joseph's Family Medical and Dental Centre, a family practice affiliated to the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Western Ontario, and the St Joseph's Health Centre, London |

| Background | – |

| Setting | Three community-based family practices in a medical centre in London, Ontario, Canada. The centre is ‘mandated to educate family medicine residents’ and comprises five teams, each consisting of: a physician, nurse, receptionist, and two residents present for two 6-month blocks during their 2-year training. All patients are affiliated with a specific team |

| Aims | ‘What factors contribute to patients' long-term attendance at a family practice teaching unit?’: to explore the ideas, opinions, feelings, and experiences of patients attending the centre and to examine their reasons for continued attendance |

| Research design | Focus groups |

| Sampling | Patients who had been affiliated with one of the three practices for ≥15 years. 75 patients were invited by letter, 42 attended. They were ‘purposefully selected to reflect a range of health problems and had received care primarily from a staff physician, a: resident, or a combination of both’. Non-attenders were said to share similar characterstics to attenders. Participant characteristics: average age 51 years (range 31–84 years); 61.9% were married; average length of time that they had been residents at the centre 31 years (range 15–29 years). About half had seen a combination of staff physician and residents, the remainder had seen primarily a staff physician (30.9%) or residents (26.2%) |

| Data collection | Focus groups were balanced for men and women and were moderated by someone (not specified) ‘affiliated with the centre, but [who] had not had any of the participants as patients’. They lasted approximately 2 hours each and were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim |

| Reflexivity | Not discussed |

| Ethical issues | Ethical approval granted by the University of Western Ontario's Review Board for Health Sciences Involving Human Subjects |

| Data analysis | ‘Using basic content analysis, the transcripts were examined independently by three of the investigators to identify key words, phrases and concepts. Similarities and potential connections among key words, phrases, and concepts within and among each of the focus groups were determined by team analysis. The analysis revealed a strong consensus of opinion among all focus groups. The final step in the analysis included reduction of data, development of major themes, and identification of relevant quotes illustrating each theme. To enhance the credibility of the findings, they were reviewed by three family physicians and presented to centre staff during grand rounds.’ |

Appendix 4. Why do patients continue to see the same physician?

| Reference | Family Practice Research Journal 1993; 13: 133–147 |

|---|---|

| Authors and institution | Lawrence Gabel, associate professor; Judith Lucas, fellow; Robert Westbury, visiting professor, Department of Family Medicine, Ohio State University, US |

| Background | – |

| Setting | Columbus, Ohio, US |

| Aims | To gain insight into the meaning patients attach to continuity of care. Research question: ‘What characteristics of physicians and practices promote long-term relationships with patients?’ |

| Research design | Structured interview (‘ethnographic interview questionnaire’). A visual analogue scale was used to ‘quantify feelings’ |

| Sampling | Four family physicians, who had been in practice longer than 15 years; two practised at Ohio State University Family Practice Center, and two were in private practice. 60 patients (15 per physician) who had seen the same family physician for a minimum of 15 consecutive years and who were 35 years or older. ‘Consecutive patients’ [presumably attendees] recruited. None refused |

| Data collection | 14 open-ended questions divided into three groups: why the patient had stayed with one physician, how the relationship with the physician had changed over time, and how the relationship could be described. Interviews lasted 20–30 minutes, were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. |

| Reflexivity | Not discussed |

| Ethical issues | Study approved by The Ohio State University Human Subjects Review Committee |

| Data analysis | Data were analysed using Ethnograph software, guided by Spradley's (The ethnographic interview, 1979) four-step process: domain analysis, semantic relationships, taxonomic analysis and contrast questions. Not told who conducted the analysis |

Appendix 5. Managed care members talk about trust.

| Reference | Social Science and Medicine 2002; 54: 879–888 |

|---|---|

| Authors and institution | Susan Dorr Goold, Department of Internal Medicine; Glenn Klipp, General Medicine Division, University of Michigan Medical Center, US |

| Background | The study began as ‘an investigation into members' “consent” to health insurance decision making, focusing on what information they valued or used, what important features led them to choose a health plan, and whether their experiences fitted their expectations.’ |

| Setting | Enrollees in managed healthcare plans in south-east Michigan, US |

| Aims | To explore consumer expectations and experiences in managed health plans. The report however ‘focuses on the role of trust in members' perceptions and experiences of managed care, a topic that participants spontaneously raised during the study’ |

| Research design | Semi-structured, open-ended interviews (31 interviews with 40 participants) |

| Sampling | Interviewees were selectively sampled through area employers (11), community-based organisations (14), personal contacts (11), and upon referral by other interviewees (3). For four interviewees in two interviews they were unsure of the sampling source. They sought to include people of diverse ethnicity, educational labels, and health status. In order to focus on the lay perspective, health professionals were excluded. Participant characteristics: mean age 41 years (range 25–71 years); 65% were male; 50% white, 30% African-American, 7.5% Hispanic, the remainder being Indian, Arab or of mixed race; self-reported health status varied from excellent to poor; annual family income varied from <US$15 000 to >US$60 000. Illnesses reported during interviews included chronic medical, mental illness and acute conditions |

| Data collection | Participants were asked about health insurance choices, experiences, and expectations. If health experiences were limited, interviewees were asked to consider a hypothetical scenario. After ‘early analysis revealed the importance interviewees attached to relationships in health care’, later interviewees were asked ‘to comment generally about their relationships with their primary doctor(s) …’ Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim |

| Reflexivity | Not discussed |

| Ethical issues | Not discussed |

| Data analysis | Formatted transcripts were imported to QSR NUD*IST for analysis. Goold coded the first 11 transcripts to develop a typology of themes. This schema was then reviewed by Klipp and Goold who finalised themes and their definitions. Interpretive analysis of the transcripts resulted in 141 individual themes organised in a hierarchical or tree structure, including eight categories with varying numbers of subthemes. Analysis focused first on themes that emerged spontaneously in interviewee discourse, including that of trust. Patterns and relationships between codes were examined in order to learn about the context in which trust discourse occurred. Trustworthiness of data interpretation was assessed by: having both investigators code a random sample of 10% of interviews and measuring agreement; asking a third party, unfamiliar with the coding scheme, to read 486 randomly selected text units (1 %) of data and to independently describe these units; presentations to others knowledgeable in the area; and coherence with existing theories and studies about interpersonal and institutional trust. |

Appendix 6. Developing, validating, and consolidating the doctor–patient relationship: the patients' views of a dynamic process.

| Reference | British Journal of General Practice 1998; 48: 1391–1394 |

|---|---|

| Authors and institution | Jonathon Gore, GP; Jane Ogden, senior lecturer in Health Psychology, Department of General Practice, UMDS of Guy's and St. Thomas's Hospitals, UK |

| Background | Undertaken as part of MSc |

| Setting | Primary care, London, UK. Four general practices: one single-handed in area of deprivation, and three group practice (three doctors, four doctor plus registrar, two doctors plus part-time academic); three of the four with ‘high, predominant or some’ deprivation |

| Aims | To examine patients' views of the process of creating a relationship with their general GP |

| Research design | Semi-structured interviews |

| Sampling | ‘Purposeful sampling’ via four practices: patients had to be registered for 2 years and to have attended at least six times per year during this period. Patients with dementia, severe psychotic illness, or who were not fluent in English were excluded. GPs checked list and were allowed to exclude any they considered to be ‘emotionally fragile’ (which excluded one patient who was replaced). Contacted by letter or telephone. We are not told if anyone declined to participate. 27 patients: 9 men, 18 women, aged 30–79 years; 6–13 visits per year, with ‘most being at the lower range’ |

| Data collection | Researcher ‘emphasised’ during interviews that he was interested in positive and negative aspects. Conversation encouraged to focus on ‘cognitions, attributions, behaviours and feelings’. Examples of questions given: ‘Why do you prefer a particular doctor?’, ‘What do you go for?’, ‘What things do you find your doctor helpful for?’, ‘Some people say that they go to see their doctor to talk about their problems. Some people just go to their doctor when they are sick. What about you?’. Interviews audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. No information on length of interviews |

| Reflexivity | Interviewees were aware that the interviewer was a GP and had had no prior contact with him. ‘Role of interviewer’ discussed: ‘novice’ interviewer (sought feedback about his technique early in the study), adopted active style of interviewing, monitored tapes for any evidence for interviewer influence. ‘Consciously encouraged both negative and positive reporting’ |

| Ethical issues | No reported ethical review. ‘Confidential and anonymous nature of the study was emphasised’ |

| Data analysis | Interviews transcribed as performed, reviewed, and used to define interview questions. When interviews complete, transcripts independently were scrutinised for common themes according to Miles and Huberman (Qualitative data analysis: a source book of new methods, 1993). [Thematic analysis] |

Appendix 7. The doctor–patient relationship in US primary care.

| Reference | Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 2003; 96: 180–184 |

|---|---|

| Authors and institution | Pam Lings, Philip Evans, David Seamark, Clare Seamark, Kieran Sweeney, Michael Dixon, Denis Pereira Gray, Institute of General Practice, University of Exeter |

| Background | Study informed by previous unpublished study of 14 patients and seven GPs conducted in the south-west of England in 1999. In this UK study the sample was selected as a homogeneous group of patients and doctors who rated their relationship as good. Data were collected from video-recorded consultations and separate in-depth interviews. Themes identified included: being listened to; being understood; caring attitude of the doctor; liking the doctor; doctor showing respect for the patient; doctor knowing the patient's context; and trust in the doctor's medical competence |

| Setting | Family Medicine Centre (Highland Hospital, Rochester, NY), US. ‘A large, urban family-orientated practice serving mainly lower and middle socioeconomic categories’ |

| Aims | To describe, conceptualise and explain patients' and doctors' experiences and behaviour with regard to the therapeutic relationship |

| Research design | Focus groups |

| Sampling | Participants ‘randomly sampled’ from Family Medicine Centre. Five patients (24 women, 10 men; 12 members of ethnic groups) and two provider (14 practitioners including physicians, residents, nurses and nurse practitioners; 11 female, none from ethnic groups) focus groups |

| Data collection | Focus groups video-recorded and transcribed verbatim (paralinguistic features evident were included). A facilitator (not specified) ‘guided the conversations, prompting the patients and providers to air their views, experiences and expectations of their relationships as doctors and patients’. Discussions 60–90 minutes. |

| Reflexivity | Not discussed |

| Ethical issues | Institutional review board at Rochester approved the study. All patients and providers gave signed consent to participation. Confidentiality was assured and permission was gained to video-record the discussions |

| Data analysis | Transcripts examined and coded in terms of unpublished UK study. Codes developed and extended as suggested by the new data. As patterns were recognised, categories were grouped together. Experience and behaviour of participants conceptualised by ‘repeated viewing of videos and group researcher meetings’. The qualitative analysis package WinMAX 98 was used. |

Appendix 8. A comfortable relationship: a patient-derived dimension of ongoing care.

| Reference | Family Medicine 2007; 39: 266–273 |

|---|---|

| Authors and institution | Nancy Pandhi, Department of Family Medicine; Barbara Bowers, School of Nursing, University of Wisconsin; Fang-pei Chen, School of Social Work, Columbia University |

| Background | – |

| Setting | Family medicine residency in Madison, Wisconsin, US |

| Aims | To examine how patients perceive a continuity of care doctor–patient relationship in a family medicine setting, from its development through its consequences |

| Research design | The grounded theory method was used ‘to guide the sampling, data collection, and analysis processes’. In-person interviews |

| Sampling | 40 eligible patients (had had an appointment 3 months prior to the study's commencement, were 18 years or older, lived in the 10 zip code areas most populated by clinic patients, and were not patients of the first author) were randomly selected and invited to take part by letter. ‘Individuals not opting out were telephoned and invited to participate in the study if their characteristics added variation to the existing sample. This subsequent participant selection was based on theoretical sampling decisions driven partly by the ongoing analysis and partly by the patient characteristics identified as important for continuity in prior research.’ Patients received US$25. Characteristics of the 14 participants: age range 25–62 years; six male; health status varied from excellent-poor; time with physician varied from 4 months to 19 years |

| Data collection | Early interviews were ‘open ended, eliciting participants' perceptions of care’. Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed ‘in entirety’. The authors say that by adopting a grounded-theory approach, they minimised the imposition of preconceptions: each interview was analysed before the next interviews, and questions were used in subsequent interviews that evolved throughout the analysis |

| Reflexivity | ‘… researchers were from nursing, social work, and family medicine backgrounds, thereby allowing for multidisciplinary perspectives and reflexivity through the discussion of assumptions or biases potentially affecting analysis’ |

| Ethical issues | ‘The study protocol was approved by the University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board, and all subjects gave informed consent’ |

| Data analysis | ‘… open, axial and selective coding schemes.’ ‘Each interview was analysed prior to conducting subsequent interviews. The subsequent interviews consisted of questions that evolved throughout the analysis. Interview questions verified the conceptual categories, generated new conceptual categories, filled in details about categories, or linked categories together. As the conceptual categories developed, early questions were replaced by other questions’ |

Appendix 9. Loyalty to the regular care provider: patients' and physicians' views.

| Reference | Family Practice 2001; 18: 53–59 |

|---|---|

| Authors and institution | Daniele Roberge, Centre de Recherche, Hopital Charles LeMoyne; Marie-Dominique Beaulieu, Slim Haddad, Ronald Lebeay, Raynald Pineault, Centre Hospital Universitaire de Montreal, Montreal, Canada |

| Background | – |

| Setting | Montreal, Canada (85% of care delivered in fee-for-service ‘private’ manner). 1997 |

| Aims | ‘To define the notion of loyalty to the attending physician’: to document and compare the vision that patients and physicians in the Montreal region have of loyalty to the regular care provider |

| Research design | Focus groups, conducted in French |

| Sampling | Three patient groups: 23 patients (27–72 years, 16 female) recruited through advertisement (received US$25). Three physician groups: 14 physicians (five women, nine men). Authors ‘strove for a certain level of heterogeneity in terms of age and sex of participants, and practice settings for physicians in each group’. First focus group: ‘physicians who serve in key positions in various medical organisations and are grappling with issues of continuity’. Generated a list of GPs ‘in various practice settings’ for recruitment purposes |

| Data collection | Pre-determined interview plan. Participants were questioned about ‘the different manners in which one could be loyal to a physician, whether or not this behaviour was unequivocal… and the temporal nature of this phenomenon’. Average duration of 1.5 hours |

| Reflexivity | Not discussed |

| Ethical issues | Not discussed |

| Data analysis | Verbatim transcripts read independently by two researchers to identify emerging themes. Themes pooled at meetings to reach consensus. ‘Validation of these thematic classifications was carried out independently by two of the team members on approximately one-third of all the verbatims.’ |

Appendix 10. Qualitative study of the meaning of personal care in general practice.

| Reference | British Medical Journal 2003; 326: 1310 |

|---|---|

| Authors and institutions | Carolyn Tarrant, research associate; Kate Windridge, research fellow; Richard Baker, professor of quality in health care, Department of General Practice and Primary Health Care, University of Leicester, UK. Mary Boulton, professor of sociology, School of Social Sciences and Law, Oxford Brookes University, UK. George Freeman, professor of general practice, Centre for Primary Care and Social Medicine, Imperial College London, UK |

| Background | – |

| Setting | Primary care, Leicestershire, UK. Six (out of 12 approached) general practices |

| Aims | To explore patients' perceptions of the features of personal care and how far these are shared by healthcare providers; whether a continuing relationship between a health professional and a patient is essential for personal care; and the circumstances in which a continuing relationship is important |

| Research design | Semi-structured interviews and focus groups to test the validity of initial interpretations |

| Sampling | Practice drew a quota sample of patients (excluding patients deemed ‘inappropriate’) and sent an invitation letter. Recruitment continued ‘until sampling frame requirements were met for diversity in age, sex, ethnicity, frequency of attendance, and health status’. Practices varied in size (1 single-handed, 2 with 2–4 partners, 3 with ≥5 partners) and location (two inner city, three suburban or urban, and one rural). Semi-structured interviews: 40 patients aged ≥18 years. Mixture of socioeconomic and ethnic group characteristics. 13 GPs, 10 practice and community nurses, and six practice administrative staff (1–4 GPs, nurses, and receptionists per practice). Focus groups: three focus groups of 28 patients and four of health professionals (18 GPs, eight practice or community nurses, and eight administrative staff) |

| Data collection | ‘Narrative based approach in interviews, with a topic guide specifying open ended exploration of the meaning, value, and priority given to personal care, and of factors that facilitated or inhibited it, in the context of each responder's experience.’ Interviews lasted 30–90 minutes; all but two interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. (One GP and one patient requested note taking only). The same investigators conducted interviews and did analysis |

| Reflexivity | Main researchers kept reflective diaries, ‘providing an audit trail relating the content and context of each interview to themes emerging during concurrent analysis’ |

| Ethical issues | Participants recruited via practices and gave consent. Ethical approval granted by local research ethics committee |

| Data analysis | ‘Framework’ analysis. Descriptive codes developed from independent repeated readings of transcripts, then identified emerging themes on the basis of initial indexing, hierarchical grouping of codes, and discussion of individual transcripts. Themes were validated by: discussion among all authors after independent reading of a sample of transcripts; focus groups (participants discussed statements relating to identified themes and were asked to give examples of any opposing beliefs); and inviting all the original interviewees to provide postal feedback on an interim report of the findings. Consequently, preliminary themes were revised and developed into thematic frameworks. Charts were drawn-up for each interviewee, summarising the meanings of personal care and the contexts within which it featured |

Appendix 11. Patient–physician trust: an exploratory study.

| Reference | Journal of Family Practice 1997; 44: 169–176 |

|---|---|

| Authors and institution | David Thom, Division of Family and Community Medicine, Department of Medicine; Bruce Campbell, Department of Health, Research and Policy Stanford University School of Medicine, California, US |

| Background | The authors thought that trust was important in patient–doctor relationships, but that this might be affected by healthcare plans: patients may be restricted in their choice of physician, or discontinuity of physician may occur |

| Setting | ‘San Francisco Bay Area’, US |

| Aims | To gain an understanding of how patients perceive trust of a physician and how patients relate physicians' behaviours to their perceptions of trust |

| Research design | Four focus groups. Working definition of trust: ‘the patient's confidence that the physician will do what is best for the patient’ |

| Sampling | Mixed recruitment strategy. Groups one and two: patients from a university-based family practice, recruited from a list of 12 long-time patients generated by the two senior physicians in the practice and 10 recruited from a list of 43 randomly sampled patients who had visited the office within the previous 6 months. Group three: recruited from a random sample of 54 English-speaking Hispanic patients who had recently (within 56 months) visited a family practice residency clinic in San Jose. Group four: recruited by flyers posted in a publicly supported medical clinic in a lower income area. Participants in groups three and four were paid US$20 |

| Data collection | Focus groups were conducted at each clinic site, lasted 1.5–2 hours, and were led by BC, a sociologist who was ‘experienced in focus group research using principles of qualitative research’. An observer was present at each session to take notes regarding the mood, non-verbal communication, and general impressions. Each group was audiorecorded and transcribed. Participants were asked to describe situations they had experienced that led them to trust a physician, and situations that had caused them to lose, or not to establish, trust |

| Reflexivity | Not discussed |

| Ethical issues | Not discussed |

| Data analysis | Transcripts were independently coded, ‘using techniques of grounded theory’: patient statements were labelled by four independent readers (a physician, a sociologist, and a research assistant, plus either a nurse researcher or a second physician) and attached to the text using Ethnograph. Labelled statements (‘open codes’) were grouped into conceptual categories (‘axial codes’) by consensus over several meetings. ‘The process was repeated for each subsequent focus group, and the categories (axial codes) were modified to incorporate new types of statements. Thus, the final categories included the reported experiences of all participants in all four groups.’ Analysis until ‘saturation’ was not done because of ‘limited resources’ |

Appendix 12. Patients' views on interpersonal continuity in primary care: a sense of security based on four core foundations.

| Reference | Family Practice 2005; 23: 210–219 |

|---|---|

| Authors and institutions | Inger von Bültzingslöwen, Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare, Goteborg, Sweden; Gosta Eliasson, Institute for Family Medicine, Stockholm, Sweden; Anneli Sarvimaki, Age Institute, Helsinki, Finland; Bengt Mattssond, Department of Primary Health Care, Goteborg University, Sweden; Per Hjortdahle, Department of General Practice and Community Medicine, University of Oslo, Norway |

| Background | Given apparent differences in the supposed value of having a personal doctor and continuity of care, and observed changes that might threaten these ideals, the team wanted to ‘… consider how patients perceive having a personal doctor in primary care and to form a theoretical model to clarify the concept and facilitate further research’ |

| Setting | Three primary healthcare centres (two in small towns, one in a bigger city) in Sweden |

| Aims | To acquire a comprehensive understanding of the core values of having a personal doctor in a continuing doctor–patient relationship in primary care among patients with long-term chronic illness |

| Research design | ‘Open individual interviews’. Working definition of personal doctor: a doctor at the primary health care centre that patients consulted and regarded as their own |

| Sampling | Primary healthcare centres had to have at least one permanent GP and at least one short-term locum; 14 patients with chronic illness (with conditions such as diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, coronary heart disease, depression, and lower back pain) and 16 healthcare professionals (three permanent GPs, one locum GP and 11 others: nurses, counsellors and receptionists). Patients were recruited by nurses at each centre who, on a randomly chosen day, asked consecutive patients seeing a doctor to take part. Patients had to: have visited the healthcare centre for at least 5 years; have any long-term chronic disease; and have experienced both periods of having a personal GP and periods of seeing short-term locum doctors. All but one patient agreed to participate. ‘Interviews were performed until saturation was reached.’ Twelve patients with experience, both from periods of having a personal GP and periods with visits to short-term doctors, were interviewed. Two patients with experience from only having a personal doctor were included to ‘add further experiences and deepen the understanding’ |

| Data collection | All interviews lasted 30–45 minutes. Patients were asked initially about their preference for having a personal doctor or not, and encouraged to elaborate freely about what they found important about seeing a personal doctor. Interviews were recorded on audiotape and transcribed verbatim after each interview |

| Reflexivity | Not discussed. We are told IvB ‘is a health care professional [without] in-depth knowledge of primary health care’, and that GE, PH, and BM are ‘experienced GPs’ |

| Ethical issues | Study approved by the Ethics Committee of the Swedish Board of Health and Welfare |

| Data analysis | Notes were ‘continuously made on preliminary ideas and reflections’, and interviews continued ‘until further data collection did not provide any additional information’. Content analysis was performed: responders' statements were concentrated into smaller meaningful units, which were then grouped into subcategories. From subcategories expressing related concepts, larger units emerged which were termed categories. This was done iteratively so that provisional coding was modified in the light of newly gathered data. Analysis was led by IvB and co-assessment was done by the other authors. ‘Triangulation was done by analysing the interviews with the doctors and other staff on what patients convey to them’ |

Appendix 13. Doctor–patient relationships in the private sector: patients' perceptions.

| Reference | Sociology of Health and Illness 1996; 18: 341–356 |

|---|---|

| Authors and institutions | Rose Wiles, Institute of Health Policy Studies, University of Southampton, UK; Joan Higgins, Health Services Management Unit, University of Manchester, UK |

| Background | – |

| Setting | Eight private hospitals and pay beds in three NHS hospitals in Wessex region (UK) |

| Aims | To examine how private patients interpret and understand their relationships with their doctors and, in particular, ‘whether patients understand the relationship with their consultants to be a consumerist one, in which they hold the power, one of mutuality, or the more traditional paternalistic one’ |

| Research design | Semi-structured interviews |

| Sampling | Sample of responders to questionnaire survey of private inpatients. Selected on basis of age and sex (reflecting questionnaire sample). All surgical patients. 35 women, 25 men. Majority aged 25–50 years and in social classes I, II, or III; 30 paid for their stays through private health insurance provided or subsided by their employers |

| Data collection | Interviews tape-recorded and transcribed in full. Not told who performed interviews |

| Reflexivity | Not discussed |

| Ethical issues | Not discussed |

| Data analysis | Transcripts analysed manually ‘by grouping the types of responses interviewees made in relation to the key topics of research’ |

Funding body

Matthew Ridd is funded by an MRC Clinical Research Training Fellowship and supported by a small grant from the RCGP Scientific Foundation Board (SFB/2004/09)

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study only draws on material that has already been published

Competing interests

The authors have stated that there are none

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.Ong LM, de Haes JC, Hoos AM, Lammes FB. Doctor–patient communication: a review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40(7):903–918. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00155-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stewart MA. Effective physician–patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ. 1995;152(9):1423–1433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams S, Weinman J, Dale J. Doctor–patient communication and patient satisfaction: a review. Fam Pract. 1998;15(5):480–492. doi: 10.1093/fampra/15.5.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beck RS, Daughtridge R, Sloane PD. Physician–patient communication in the primary care office: a systematic review. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15(1):25–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freeman G, Shepperd S, Robinson I, et al. Continuity of care: report of a scoping exercise for the SDO programme of NHS R&D. London: NHS Service Delivery and Organisation National Research and Development Programme; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saultz JW. Defining and measuring interpersonal continuity of care. Ann Fam Med. 2003;1(3):134–143. doi: 10.1370/afm.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haggerty JL, Reid RJ, Freeman GK, et al. Continuity of care: a multidisciplinary review. BMJ. 2003;327(7425):1219–1221. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7425.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall MA, Dugan E, Zheng B, Mishra AK. Trust in physicians and medical institutions: what is it, can it be measured, and does it matter? Milbank Q. 2001;79(4):613–639. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duck S. Human relationships. 3rd edn. London: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dowrick C. Rethinking the doctor–patient relationship in general practice. Health Social Care Comm. 1997;5:11–14. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Potter SJ, McKinlay JB. From a relationship to encounter: an examination of longitudinal and lateral dimensions in the doctor–patient relationship. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(2):465–479. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mays N, Pope C, Popay J. Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidenced to inform management and policy-making in the health field. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(Suppl 1):6–20. doi: 10.1258/1355819054308576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]