Abstract

Purpose

Examine the event-level association between alcohol consumption and the likelihood of unprotected sex among college-age young adults considering contextual factors of partner type and amount of alcohol consumed.

Methods

A 30-day web-based structured daily diary was used to collect daily reports of sexual behaviors and alcohol use from sexually-active young adults (N = 116) yielding 2,764 diary records. Each day we assessed the prior evening’s behavior regarding, alcohol consumption, opportunities for sex, sexual intercourse, condom use, and contextual factors including type of sexual partner.

Results

Based on multilevel models, drinking proximal to events of sexual intercourse increased the likelihood of unprotected sex with casual but not steady partners. For women there was a positive association between number of drinks and a greater likelihood of unprotected sex with casual partners but a negative association with steady partners. Drinking during situations involving opportunities for sex with casual partners increased the likelihood of sex. For women especially, drinking more increased the likelihood of sex occurring regardless of partner type.

Conclusions

Failure to assess the contextual determinants of the alcohol—unprotected sex association may result in underestimates of the magnitude of this association. These data highlight an important area for intervention with young adults: reducing alcohol-involved sexual risk behavior with casual partners, especially among women.

Keywords: condoms, young adults, alcohol consumption, sexual behavior, sexual partners, prospective study

INTRODUCTION

Half of all new HIV infections occur among individuals aged 24 and younger [1]. Adolescents and young adults aged 15–25 have the highest rate of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) of any age group in the U.S.[2] Despite awareness of the risks, inconsistent condom use among adolescents and young adults is quite common [3, 4]. Research has implicated alcohol use as a contributing factor to unprotected sex in these populations [e.g., 5]; as will be discussed, this finding has come under scrutiny in recent years.

The preponderance of the evidence supporting an alcohol-unprotected sex association is cross-sectional. Although aware of the limitations of correlational data, researchers often assume findings from such data provide “a reasonably accurate picture of how strongly a factor influences behavior” [6]. However, the hypothesized alcohol use-unprotected sex association pertains to the acute and transient effects of alcohol use on a second transient, discrete outcome.

Cross-sectional data do not shed light on important probative questions. Among these is the question of whether, for a given person at a given point in time, does any alcohol use proximal to a sexual situation, as compared to no alcohol use, influence the likelihood that sex will occur and that condoms will be used? A second question is whether, when alcohol is consumed proximal to sexual situations, does the amount of alcohol consumed influence the likelihood of unprotected sex? Hence, a cross-sectional approach is of only limited utility in assessing the impairment hypothesis, i.e. that acute alcohol use adversely affects risk-related decision-making in sexual situations.

In cross-sectional designs, condom use is generally treated as a context-independent outcome. That is, the researcher may recognize that a variety of situational variables influence the likelihood of condom use on a given occasion, but assumes that the effects of these variables are non-systematic and are “washed out” in the process of aggregation. Yet, there are commonly occurring social contexts in which situational variables may systematically influence the likelihood of condom use; for example, social events at which alcohol is served and sex partners are sought. In such situations, alcohol use and partner type (i.e., “casual” vs. “primary”) are important contextual determinants of behavior [7].

Researchers can overcome many of these challenges by collecting event-level data which provide contextual information on discrete occasions of sexual activity. This permits the researcher to record alcohol use and sexual activity on a given day and obtain partner-specific information such as partner type. In a review of studies examining event-level associations between alcohol use and unprotected sex, Weinhardt and Carey found consistent evidence to suggest that the effects of alcohol on the likelihood of unprotected sex are negligible if one also considers contextual variables such as an individual’s level of sexual experience and partner type [7]. More recent studies using daily diary methods to collect repeated event-level data further substantiate the conclusion that the association between alcohol use and unsafe sex is sensitive to, or even dependent on, the presence of certain contextual variables [e.g., 8, 9–11].

One drawback to diary methods is the high density of measurement occasions required may produce instrument reactivity effects. These manifest as sensitization or habituation, referring, respectively, to the participant’s increased self-awareness as a result of recording the behavior and the participant’s decreasing susceptibility to socially desirable responding as the novelty of the diary-keeping task fades. Researchers have reported that reactivity effects are negligible [12]. In terms of accuracy, a diary approach holds demonstrable advantages over conventional recall techniques that require the participant to make estimates of his / her average consumption over a period of days or weeks. The perceived anonymity of interactions with electronic methods of diary data collection may increase the participant’s willingness to report socially undesirable behaviors [13].

In recommending future refinements to diary methods, Weinhardt and Carey note that most studies they reviewed treated alcohol use prior to sex as a dichotomous variable, and urged future researchers to consider not only the question of whether alcohol was consumed, but how much [7]. To date, and despite its strong relevance to the impairment hypothesis, this recommendation has not been widely adopted. An exception is a recent diary study of a sample of persons living with HIV/AIDS, in which increasing number of drinks consumed prior to sex was found to decrease the estimated likelihood of unprotected sex among women, but increase the likelihood of unprotected sex among men [14]. Notably, in these data there was no association between a dichotomous measure of alcohol consumption (any vs. none) and likelihood of unprotected sex. This suggests that the effect of alcohol use on the risk of unprotected sex may be most evident at higher levels of consumption.

Event-level analyses also have shown that the association between alcohol use and unprotected sex among adolescents and young adults may be confined to sex acts involving casual partners [15, 16]; [c.f. 8, 11]. Whereas the use or non-use of condoms is routinized in established relationships, this is less likely to be the case with respect to sex acts involving casual partners [17]. The absence of a pre-established routine by definition increases the likelihood that the individual will face unexpected complications, such as the non-availability of condoms, heightened social evaluation anxiety or sexual arousal, or a partner’s refusal to use condoms. This may result in a heightened situation-specific vulnerability to unsafe sex that is exacerbated by concurrent alcohol use.

The association between partner type and condom use is affected by gender. Data suggest that women may exhibit compensatory increases in risk-aversion during alcohol-involved sexual situations [18, 19]. This is attributable to the situational cues which trigger increased awareness of the potential risks of unsafe sex – and these risks, including unintended pregnancy, are substantially greater for women than for men. These risks may also be especially salient in the context of sexual activity involving a casual partner.

From a methodological standpoint, it is notable that Brown et al. collected event-level data relating to participants’ most recent sexual experience [16]. As a result, they were unable to estimate, for each participant, an estimate of the overall likelihood of unprotected sex or sexual activity with either a casual or steady partner. Nor were they able to consider potential interactions between gender and partner type.

Researchers have noted gender differences in the effects of alcohol on sex-related outcomes. Alcohol use provides a means of reducing one’s culpability for engaging in a socially undesirable behavior [20], and women face stricter injunctive norms regarding appropriate sexual behavior than men [21]. Women reach higher peak blood alcohol levels than do men at equivalent doses of alcohol [22]. Hence, one might expect, at comparable dosages, more substantial alcohol-related changes in the sexual behavior of women as compared to men.

If alcohol consumption in fact functions to ease sexual inhibitions, its effects may more noticeable in the case of women and in the case of acts involving casual sex partners. Other gender differences exist, however, which have the potential to make these partner type-specific patterns less clear-cut. For men as compared to women, a greater preoccupation with sex has been observed, as assessed by the day to day frequency of self-reported sexual thoughts [23]; if this translates to a greater overall willingness to engage in sex, this may attenuate any effect on behavior that can be attributed to alcohol use. For women, as compared to men, the capacity to experience sexual arousal and responsiveness is more strongly influenced by daily stressors [26]; hence, alcohol use may function as a means of stress-reduction and be positively associated with the likelihood of sex.

The Current Study

We employed a daily diary methodology to examine the event-level association between episodes of alcohol use and episodes of sexual activity, relying on daily event-specific self-reports provided by participants over the course of 30 days. Alcohol use was considered both as a dichotomous “any” vs. “none” variable and as a continuous variable based on the number of standard drinks consumed (see below). We evaluated the following hypotheses: (1) drinking any alcohol and drinking more alcohol on a particular evening increases the likelihood that sexual intercourse will occur provided an individual has the desire and opportunity to have sex; and (2) drinking any alcohol and consuming greater quantities of alcohol proximal to sexual activity increase the likelihood that sex will be unprotected. Regarding moderating variables, we predicted that the hypothesized associations would be most evident when sex acts involved casual partners, and for women as compared to men.

METHODS

Participants

A total of 223 young adults who were college undergraduates participated in a larger longitudinal cohort daily diary study on alcohol use. These participants were recruited from the psychology department participant pool at the University of Connecticut. At the conclusion of the study participants received research credit and a small cash incentive, the amount of which varied based upon the number of days completed each week. Eligible participants had consumed alcohol at least once in the 30 days preceding the study, as identified during a pre-screening assessment. For the present analysis, we selected only those who were sexually active during the 30 day study. The resulting sample consisted of 116 participants (49 male, 67 female), average age 19.15 (SD = 1.51), 65% of whom were in a dating relationship at the time of the study. A majority (89%) described themselves as White/European-American, 5% as African-American, and the remainder reported other racial/ethnic backgrounds. Excepting age (non-selected participants were slightly younger M = 18.8), demographics did not differ between those selected for the present analysis and the larger cohort. For the entire sample, age was not related to the likelihood of condom use or related factors.

Procedure

All study procedures were approved by the IRB at the University of Connecticut and written informed consent was obtained from participants in an orientation session prior to completion of the baseline questionnaire. After completing a baseline questionnaire, participants were asked to access a password-protected website each day between 2:30 and 7:00pm to complete diary entries. Of the possible 3,480 daily diary days during the 30 day study, participants completed 79.43% of the possible days or 2,764 days. The mean number of days completed was 23.80 (SD = 6.13). The number of diary days completed was not related to the outcome or any of the predictor variables.

Measures

Daily alcohol consumption

Questions included in the diary focused on the number of drinks consumed “last night.” Response options ranged from 0 to 15 in single increments, with an option to select “more than 15.” A standard drink was defined as 12-ounces of beer, 5-ounces of wine and 1.5 ounces of liquor straight or in a mixed drink.

Sexual behaviors and sexual situations

Global association studies of the alcohol use-unprotected sex association typically do not consider unprotected sex relative to the overall frequency of sexual activity per participant; nor do these studies only consider occasions of sexual activity in which alcohol use could plausibly contribute to unprotected sex. In this study, participants were asked to report if they had sex last night and if applicable whether condoms were used.

Logically, alcohol use will not affect the likelihood of unprotected sex in social contexts in which the opportunity to engage in sex does not exist. When participants did not report sexual activity, they were asked yes/no questions regarding whether each of the following accurately explained the absence of penetrative sexual activity: (1) no desire for sex, (2) no opportunity for sex, (3) unavailability of condoms, (4) concern about STDs, HIV, or pregnancy, and (5) sexual activities occurred that did not involve penetration (e.g., mutual masturbation). Participants were also asked to describe the partner (even if they did not have sex) as either “casual” or “steady.” In this study, the designation of “casual” partner describes either “someone that I do not know well, such as someone I just met at a party” or “someone that I know well” but who is not a “steady” (i.e. ongoing) sex partner.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

Evening alcohol consumption was reported on 694 of the 2,764 person days for a total of 4,311 standardized drinks consumed across the 116 participants during the 30-day study. Men reported drinking on an average of 6.43 evenings (SD = 4.98) and women reported drinking on an average of 5.59 evenings (SD = 4.10) during the 30-day study. Mean number of drinks on nights when alcohol was consumed was 6.29 (SD = 3.13) for men and 4.60 (SD= 2.19) for women. Participants reported a total of 337 opportunities to have sex in which sex did not occur. The minority (82) of those events co-occurred with alcohol consumption. A majority of the sample (76%) reported at least 1 occasion of sex co-occurring with alcohol consumption. Among a total of 747 sexual intercourse events, 189 involved alcohol consumption. A majority (58%) of the sample reported at least 1 event of unprotected sex. Participants reported a total of 433 unprotected sexual intercourse events (58% of total sex events), 103 of those involved alcohol consumption. Among the 75 participants who reported at least one sex event that occurred when they had been drinking and at least one sex event that occurred when they had not been drinking, 40% (46% for women, 37% for men) of sex events that involved alcohol were unprotected, whereas 35% (38% for women, 30% for men) of sex events that did not involve alcohol were unprotected. Regarding partner type, the majority of the sample (81%) reported sex with steady partners, 30% reported sex with casual partners, and 11% reported sex with both steady and casual partners.

Data Analytic Approach

Multilevel logistic regression models using HLM6 [24] were estimated to examine the event-level within-person relationships between alcohol consumption, partner type and sexual behavior. The outcome variables in the analyses were: (a) the probability of sexual intercourse on days when an individual had the opportunity and desire to have sex; and (b) the probability of unprotected sex on days when an individual had sexual intercourse. Separate models were estimated to examine the effect of alcohol consumption proximal to sex (regardless of quantity) and the effect of the quantity of alcohol consumed (number of standardized drinks ranging from 1 to 15) proximal to sex on sexual behavior. For the purpose of estimating moderating effects in the models the number of drinks consumed variable was centered around the sample mean. Partner type and the interaction between alcohol and partner type were included as within-person (event-level) predictors. The slopes of the event level predictors did not significantly (p > .10) randomly vary across persons, therefore the variances of these effects were fixed to zero. Non-significant moderating effects were also trimmed from the final models. We examined possible changes over time in alcohol and sexual behavior by including study day as a predictor of these two behaviors; it was not significant.

The Effect of Alcohol Consumption on the Likelihood of Sexual Behavior

The results of the trimmed model are presented in Table 1; we found a significant partner type × alcohol use interaction. Using the beta coefficients from the estimated model, we calculated the predicted probability that sex would occur in a situation in which the individual had the opportunity to have sex (logit beta coefficients not shown). For example, the model for the effect of alcohol consumption on the likelihood of sexual behavior took the following form:

Probability of Sexual Behavior = β00 (Intercept) + β10 (Partner Type) + β20 (Alcohol before sex) + β30 (Partner Type × Alcohol) + β11 (Partner Type × Gender)

Consuming alcohol proximal to sex with a casual partner increased the probability that sex would occur in a situation in which the individual had the opportunity to have sex (0.56 when no alcohol was consumed vs. 0.85 when alcohol was consumed), whereas with steady partners consuming alcohol did not affect the likelihood of sex (0.79 when no alcohol was consumed vs. 0.83 when alcohol was consumed).

Table 1.

Estimates for the models predicting the probability of sexual intercourse and unprotected sex, controlling for opportunity, from partner type and alcohol

| Sexual Intercourse | Unprotected Sex | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event-Level Effects | OR (CI) | t (df) | OR (CI) | t (df) |

| Intercept | 5.96 (2.10–17.00) | 3.38 (115)*** | 1.62 (.43–6.15) | .72 (115) |

| Partner Type | .61 (.31–1.19) | 1.45 (809) | .22 (.10–.49) | 3.77 (809)*** |

| Alcohol Before Sex (Y/N) | .64 (.33–1.25) | 1.31 (809) | .71 (.51–1.00) | 1.89 (809)† |

| Partner Type × Alcohol | 1.60 (1.01–2.57) | 1.96 (809)* | 2.27 (1.26–4.09) | 2.73 (809)** |

| Interactions between Event-Level and Between-Person Effects | ||||

| Partner Type × Gender | - | - | 2.30 (1.03–5.13) | 2.03 (809)* |

| Variance | τoo | χ2 (113) | τoo | χ2 (113) |

| Variance in the outcome | 1.80 | 372.63*** | 4.31 | 450.74*** |

OR, odds ratio, CI, 95% confidence interval.

p<.10

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Effects that were not statistically significant and were not involved in interaction terms were trimmed from the final models and therefore do not appear in the table.

The Effect of Alcohol Consumption on the Likelihood of Unprotected Sex

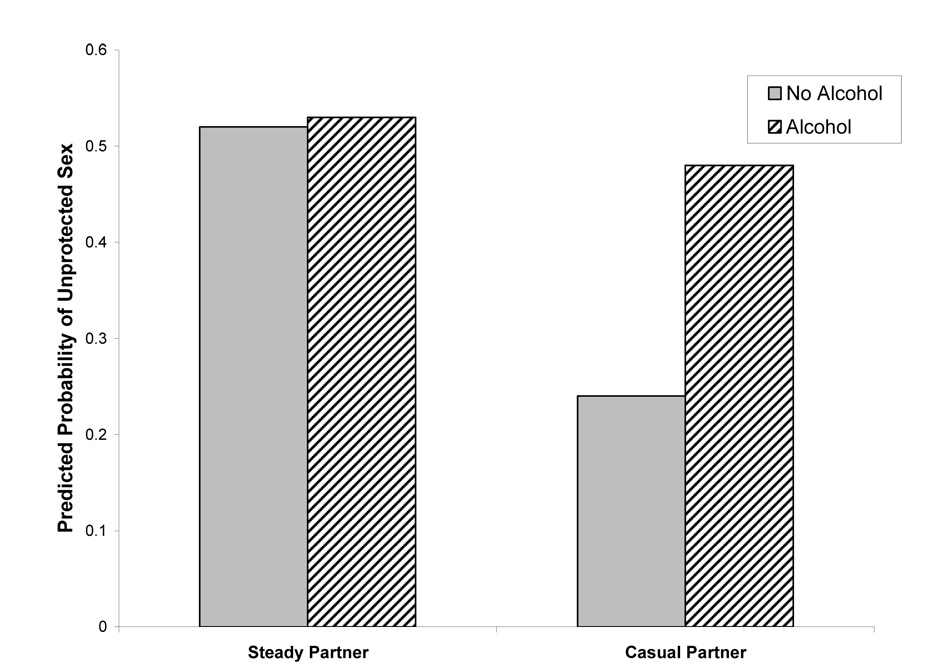

As shown in Table 1, the partner type × alcohol use interaction shows that consuming alcohol proximal to with sex with steady partners did not increase the likelihood of unprotected sex; however, when alcohol was consumed proximal to sex with casual partners the probability of unprotected sex increased from 0.24 to 0.48 (see Figure 1). Gender moderated the effect of partner type on the likelihood of unprotected sex. For men, unprotected sex was more likely to occur with steady than with casual partners (0.27 vs. 0.08) but this difference was smaller for women (0.46 vs. 0.29 with steady and casual partners respectively).

Figure 1.

Moderating effect of partner type on the event-level association between drinking proximal to sexual activity and the likelihood that sex would be unprotected

The Effect of Quantity of Alcohol Consumed on the Likelihood of Sexual Behavior

As shown in Table 2, we found that gender moderated the effect of alcohol quantity on the likelihood of sex; none of the other effects were significant. As illustrated in Figure 2, for women the likelihood of sexual intercourse increased as a function of the number of drinks consumed but for men the quantity of alcohol consumed had little effect on the likelihood of sexual intercourse.

Table 2.

Estimates for the models predicting the probability of sexual intercourse and unprotected sex, controlling for opportunity, from partner type and number of drinks

| Sexual Intercourse | Unprotected Sex | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event-Level Effects | OR (CI) | t (df) | OR (CI) | t (df) |

| Intercept | 2.28 (.75–6.78) | 1.46(115) | 4.07 (.51–32.46) | 1.34 (115) |

| Partner Type | .91 (.43–1.92) | .26 (267) | .09 (.01–.71) | 2.30 (265)* |

| Number of drinks | 1.03 (.94–1.13) | .60 (267) | 1.01 (.68–1.59) | .06 (265) |

| Partner type × Number of drinks | 1.14 (.95–1.36) | 1.38 (267) | 1.18 (1.01–1.40) | 2.00 (265) * |

| Interactions between Event-Level and Between-Person Effects | ||||

| Number of drinks × Gender | 1.15 (1.02–1.29) | 2.24 (267)* | - | - |

| Partner Type × Number of drinks × Gender | - | - | 1.86 (1.21–2.86) | 2.86 (265) ** |

| Variance | τoo | χ2(93) | τoo | χ2 (94) |

| Variance in the outcome | 1.45 | 153.39*** | 2.19 | 181.85*** |

OR, odds ratio, CI, 95% confidence interval.

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Effects that were not statistically significant and were not involved in interaction terms were trimmed from the final models and therefore do not appear in the table.

Figure 2.

Gender differences in the effect of the number of drinks consumed proximal to opportunities to have sex on the likelihood that sex would occur the same evening

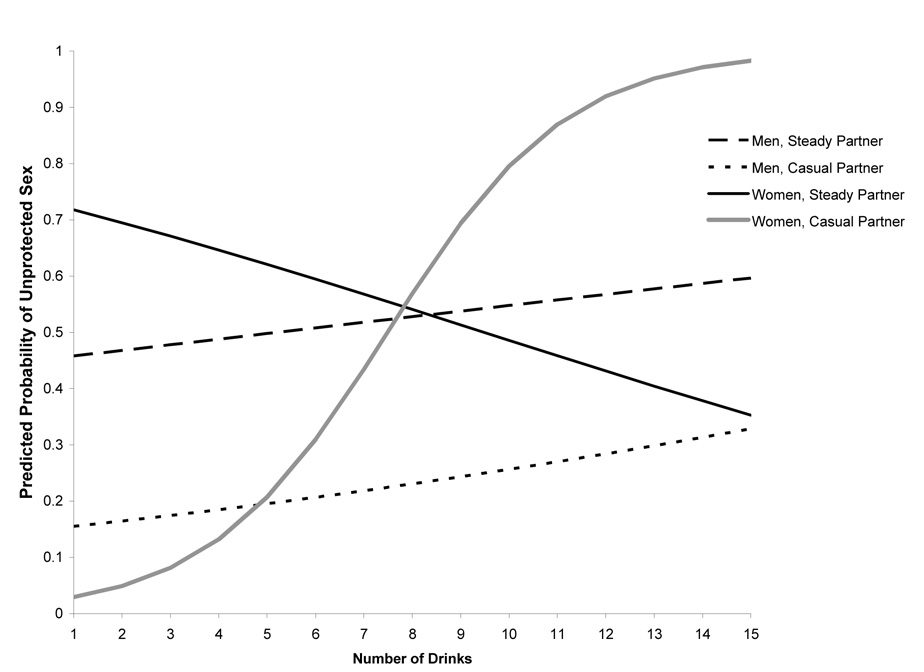

The Effect of Quantity of Alcohol Consumed on the Likelihood of Unprotected Sex

A statistically significant interaction between partner type × number of drinks consumed × gender revealed the specific circumstances under which consuming more alcohol increases the likelihood that sex will be unprotected (see Table 2 and Figure 3). As Figure 3 illustrates, among female participants, if a partner is described as “steady”, the likelihood of unprotected sex decreases as self-reported number of drinks increases; in contrast, if a partner is described as “casual,” the likelihood of unprotected sex increases in direct relation to increasing numbers of drinks. Among male participants, the likelihood of unprotected sex increased only slightly as a function of increasing amounts of alcohol consumption consumed proximal to sex regardless of partner type.

Figure 3.

Gender and partner type differences in the effect of the number of drinks consumed proximal to sexual activity and the likelihood that sex would be unprotected

DISCUSSION

We predicted that, given the opportunity and desire to have sex, drinking any amount alcohol and drinking increasing amounts of alcohol on a given evening each increases the likelihood that sexual activity will occur. Secondly, we predicted that any alcohol use and increasing amounts of alcohol consumption are each associated with a greater event-specific likelihood of unprotected sex. We also evaluated, as moderating variables, participant gender and “casual” vs. “steady” partner type.

We found support for our hypotheses, but only in certain situations and for certain individuals. When treating alcohol use as an “any” versus “none” dichotomous variable, the consumption of any alcohol on a given evening increased the likelihood that sex would be unprotected, but only in the case of casual partners which is consistent with some prior findings [e.g., 15, 16], but contrary to others [e.g., 11, 25].

When treating alcohol use as a continuous variable (i.e., number of drinks consumed), among women, consuming greater amounts of alcohol increased the likelihood that sex would occur that evening and, if the sex was with casual partners, increased the likelihood that sex would be unprotected. Differing findings relative to the type of sexual partner may be explicable if one posits that the use or non-use of condoms is routinized when engaging in sex with an established partner, but not when engaging in sex with a new or casual partner. In the absence of a partner-specific routine, variability in condom use behavior is by definition greater. Among men, consuming greater quantities of alcohol led to only a slight increase in the likelihood that sex would be unprotected regardless of partner type.

Future diary research should undertake the process of teasing apart alternative explanations for the observed gender differences by assessing individual differences in the degree to which sexual double-standards have been internalized, level of sexual experience, susceptibility to social influence, and event-specific estimated blood alcohol concentration. Future research should also attempt to reconcile the conflicting findings from event-level diary studies regarding the role of alcohol in precipitating unprotected sex by closely examining this association in different situations with different populations including younger and higher-risk young adults and adolescents. Since our sample was composed of primarily White college students caution should be exercised when generalizing the findings to other populations including young adults who are not in college and young adults from other races and ethnic groups. A final limitation of the study is that, despite our ability to locate both sexual activity and alcohol use in the same evening – with “evening” defined as the hours between making a diary entry and going to sleep – the data do not permit us to establish with certainty that drinking occurred prior to sexual activity.

Despite these limitations, the current research is among the few event-level studies of alcohol-involved sexual risk behavior to collect multiple event-level records of alcohol use and sexual activity from participants over a period of weeks. As such, we have been able to account for individual differences in the overall frequency of protected and unprotected sexual activity and alcohol consumption, and assess the influence of partner type and gender on the association between alcohol use and sexual behavior among young adults. The present data highlight an important area for intervention with young adults—reducing alcohol-involved sexual risk behavior with casual partners, especially among women.

Acknowledgements

Support for this study was provided by NIAAA grant P50-AA03510. Support for preparation of this manuscript was provided in part by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (NRSA), Individual Pre-doctoral Fellowship from NIMH, F31MH072547 (Kiene). We thank Jennifer Scanlon, Amy Setkowski, and Nick Maltby for their invaluable involvement in the data collection for the larger study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Futterman DC. HIV in adolescents and young adults: half of all new infections in the United States. Top HIV Med. 2005;13:101–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisher WA, Fisher JD, Harman J. The Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills Model: A general social psychological approach to understanding and promoting health behavior. In: Suls J, Wallston KA, editors. Social Psychological foundations of health and illness. Malden, MA: Blackwell; 2003. pp. 82–106. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kiene SM, Barta WD. A brief individualized computer-delivered sexual risk reduction intervention increases HIV/AIDS preventive behavior. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:404–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dingle GA, Oei TP. Is alcohol a cofactor of HIV and AIDS? Evidence from immunological and behavioral studies. Psychol Bull. 1997;122:56–71. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.122.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinstein ND. Misleading tests of health behavior theories. Ann Behav Med. 2007;33:1–10. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3301_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinhardt LS, Carey MP. Does alcohol lead to sexual risk behavior? Findings from event-level research. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2000;11:125–157. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bailey SL, Gao W, Clark DB. Diary study of substance use and unsafe sex among adolescents with substance use disorders. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38(297):e13–e20. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gillmore MR, Morrison DM, Leigh BC, et al. Does 'high=high risk'? An event-based analysis of the relationship between substance use and unprotected anal sex among gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav. 2002;6:361–370. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrison DM, Gillmore MR, Hoppe MJ, et al. Adolescent drinking and sex: findings from a daily diary study. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2003;35:162–168. doi: 10.1363/psrh.35.162.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leigh BC, Vanslyke JG, Hoppe MJ, et al. Drinking and Condom use: Results from an Event-Based Diary. AIDS Behav in press. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9216-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hufford MR, Shields AL, Shiffman S, et al. Reactivity to ecological momentary assessment: an example using undergraduate problem drinkers. 2002;16:205–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McAuliffe TL, DiFranceisco W, Reed BR. Effects of question format and collection mode on the accuracy of retrospective surveys of health risk behavior: a comparison with daily sexual activity diaries. 2007;26:60–67. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barta WD, Portnoy DB, Kiene SM, et al. A Daily Process Investigation of Alcohol-Involved Sexual Risk Behavior Among Economically Disadvantaged Problem Drinkers Living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav in press. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9342-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fortenberry JD, Orr DP, Katz BP, et al. Sex under the influence. A diary self-report study of substance use and sexual behavior among adolescent women. Sexually transmitted diseases. 1997;24:313–319. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199707000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown JL, Vanable PA. Alcohol use, partner type, and risky sexual behavior among college students: Findings from an event-level study. Addict Behav. 2007;32:2940–2952. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vanable PA, McKirnan DJ, Buchbinder SP, et al. Alcohol use and high-risk sexual behavior among men who have sex with men: the effects of consumption level and partner type. Health Psychol. 2004;23:525–532. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacDonald TK, Fong GT, Zanna MP, et al. Alcohol myopia and condom use: Can alcohol intoxication be associated with more prudent behavior? 2000;78:605–619. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.4.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nolen-Hoeksema S. Gender differences in risk factors and consequences for alcohol use and problems. Clinical psychology review. 2004;24:981–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crowe LC, George WH. Alcohol and human sexuality: review and integration. Psychol Bull. 1989;105:374–386. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.105.3.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marston C, King E. Factors that shape young people's sexual behaviour: a systematic review. Lancet. 2006;368:1581–1586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69662-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilsnack RW, Vogeltanz ND, Wilsnack SC, et al. Gender differences in alcohol consumption and adverse drinking consequences: cross-cultural patterns. Addiction. 2000;95:251–265. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95225112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fischtein DS, Herold ES, Desmarais S. How much does gender explain in sexual attitudes and behaviors? A survey of Canadian adults. Archives of sexual behavior. 2007;36:451–461. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9157-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW, Congdon R. Chicago, IL: Scientific Software; 2005. HLM 6.0. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leigh BC. Alcohol consumption and sexual activity as reported with a diary technique. J Abnorm Psychol. 1993;102:490–493. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.3.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]