Abstract

Purpose

In an initial study of prism-induced exodeviation, degraded stereoacuity was not associated with decreased binocular visual acuity, suggesting that accommodative convergence was not recruited. Distance stereoacuity degraded earlier when measured with the Frisby Davis Distance (FD2), than when measured with the Distance Randot (DR). We now describe a follow-up study in which we reversed the prism order and also addressed potential biases of testing order and different measurable levels of stereoacuity to clarify the relationship between exodeviation, distance stereoacuity, and binocular visual acuity.

Methods

Convergence stress was induced with base-out prism in 20 adults and increased stepwise. Stereoacuity and binocular visual acuity were measured at each step. Disparities tested were 200, 100, and 60 seconds of arc, and testing was repeated at each prism step.

Results

Most subjects showed degraded stereoacuity with the FD2 in contrast to the DR (80% vs 45%, P = 0.02). Reduction of stereoacuity occurred earlier on the FD2 than on the DR (median 18Δ vs. 40Δ, P = 0.001). Degradation of stereoacuity was associated with minimal change in binocular visual acuity from baseline to maximal convergence stress (median 20/15 to 20/20).

Conclusion

Convergence stress is associated with decreased distance stereoacuity that does not appear to be due to accommodative convergence. Performance on real world stereotests (FD2) is affected more than random dot tests (DR), in contrast to previous findings in intermittent exotropia. There appear to be different mechanisms for decreased stereoacuity in intermittent exotropia and under conditions of convergence stress in nonstrabismic subjects.

Introduction

Intermittent exotropia is the most common form of exotropia, occurring in approximately 1% of children,1 but indications for intervention are poorly defined. Some authors2,3 suggest early surgery to preserve stereoacuity, but this has not been rigorously studied. Reduced distance stereoacuity and reduced distance binocular visual acuity in intermittent exotropia have been suggested to result from excessive accommodative convergence required to control the deviation.4 Nevertheless, the role of distance stereoacuity testing in the evaluation of intermittent exotropia is controversial.5-7 It has been suggested that distance stereoacuity in intermittent exotropia deteriorates as control of the deviation deteriorates,5,6 which might be due to the use of accommodative convergence or to the fragility of motor convergence.4,6,8 Others report distance stereoacuity to be either normal or absent in intermittent exotropia.7

We previously performed an initial study8 modeling aspects of intermittent exotropia by inducing exodeviations in nonstrabismic volunteers using base-out prisms. We found that binocular visual acuity remained 20/20 while distance stereoacuity degraded, suggesting that accommodative convergence was not used to control prism-induced exodeviations. We also found that distance stereoacuity was degraded (defined as >60 seconds of arc) rather than either normal or absent in most subjects under convergence stress.8 In that initial study, the testing paradigm started with larger prisms and progressed to smaller prisms, resulting in transition from diplopic to fused rather than vice versa. The degree of stereoacuity degradation depended on the test used. The Frisby-Davis Distance (FD2)(Frisby Stereotest, Sheffield, UK) appeared to degrade more readily than the Distance Randot (DR)(StereoOptical Co, Inc, Chicago, IL).8 This difference between tests is in contrast to that of patients with intermittent exotropia who perform better on the FD2 than the DR.6 It is possible that this discrepancy reflects a difference between patients with intermittent exotropia and nonstrabismic subjects with prism-induced exodeviations, or the difference may be due to biases of the initial study protocol. In the initial study, the FD2 was tested first, which may have allowed for adaptation to occur prior to testing with the DR. Also, in the initial study the finest disparities tested were different between the FD2 and the DR (20, and 40 seconds of arc with the FD2, and 60 seconds of arc with the DR), so subjects could reach “fine stereo” (defined as ≤60 seconds of arc) at larger disparities with the DR, arguably giving the DR a performance advantage. The current study was designed to control for these potential biases and more directly compare performance on the FD2 verses the DR in nonstrabismic subjects with prism-induced exodeviations.

We performed the present study to clarify the relationship between induced exodeviations, distance stereoacuity and binocular visual acuity, and to address the weaknesses of our previous study.8 We also aimed to confirm or refute our previous findings, which were under conditions of decreasing convergence stress, by using a model of increasing convergence stress in this present study. The current study also evaluated whether our previous findings of differences between stereotests was due to adaptation or fatigue or due to a difference in stereoacuity levels tested in the previous study.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

Twenty subjects aged 18 and older with normal stereoacuity (at least 40 seconds of arc assessed by Preschool Randot® [StereoOptical Co Inc Chicago, IL]; normal visual acuity (best-corrected acuity 20/20 Snellen or better in each eye; interocular difference of less than or equal to one line), no prior history of ambylopia, and no strabismus (no tropia by simultaneous prism and cover test and no more than 4 pd of exophoria at distance or 9 pd of exophoria at near) or strabismus surgery were enrolled in the study. Informed consent was obtained from each study participant. The study was approved by an institutional review board, and data were collected in an American Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant manner.

Induction of Convergence Stress

Convergence stress was induced for each subject with base-out trial lens prisms worn in trial frames or clipped over the patients’ glasses. We postulated that these exodeviations would stress the convergence system. Subjects were tested with habitual optical correction in glasses or contact lenses. The initial level of testing of 2 prism diopters (Δ ) of exodeviation was achieved by placing a 2Δ base out prism over the right eye. Subsequent levels of 4Δ, 6Δ, 8Δ, 10Δ, 12Δ, 14Δ, 16Δ, 18Δ, 20Δ, 25Δ, 30Δ, 35Δ, and 40Δ were tested by splitting the total prism power between the two eyes by placing 2 prisms of equal, or near equal, magnitudes in the trial frames, one prism over each eye. Care was taken to exchange prisms without touching the trial frames or the clip-on prism holders in order to keep the prisms perfectly horizontal. Testing was performed in this order (lowest to highest prism) to simulate a patient with single vision, using convergence (accommodative and/or motor) to maintain single vision.

Testing started immediately upon placement of the prisms and began with assessment of control of the exodeviation at distance (3 meters) using the Mayo Control Score,9 a 6-point scale quantifying control from 0 (phoric) to 5 (tropic). Binocular visual acuity was then assessed followed by stereoacuity. Subsequent prisms were placed immediately without any period of recovery between tests. Subjects closed their eyes between testing steps for the duration of time necessary to exchange prisms in the trial frames (approximately 5 seconds per prism). The entire testing protocol took 60-90 minutes.

Measurement of Stereoacuity

Distance stereoacuity (3 meters) was evaluated four times at each prism step in the following order: DR, FD2, DR, and FD2. This testing order was chosen because the FD2 was tested first in the initial study, which may have allowed for adaptation to the prism and improved performance on the DR. We reversed the order in the current study to control for the possibility of adaptation to the prism during the testing time to prevent giving a performance advantage to the DR. Both stereoacuity tests were repeated at each prism step to test for adaptation or fatigue. We defined stereoacuity at each prism step as the better of the two scores for both the DR and the FD2 in order to minimize bias when testing the hypothesis “does stereoacuity decrease with increasing convergence stress.” Test levels for the DR and the FD2 were identical and were 200, 100, and 60 seconds of arc. These levels were chosen because the DR is manufactured to test these levels, and the FD2 is adjustable and could be set to match the manufactured DR levels.

FD2 testing followed the procedure of Holmes and Fawcett,10 with the exception of the levels tested (described above) and the monocular phase, which was performed once prior to the induction of exodeviation and the results of which were applied to all subsequent FD2 tests. For example, if a subject scored nil when tested monocularly, it was assumed that he or she would not achieve factitious stereoacuity scores by utilizing monocular cues for the remainder of the study. If, however, the subject achieved 200 seconds of arc monocularly, only values better than 200 were recorded as true binocular stereoacuity, and 200 seconds of arc was recorded as nil. In this particular group of subjects, none passed the largest disparity of the FD2 (200 seconds of arc) when tested monocularly.

For DR testing, two out of two correct responses at each disparity level were required to pass the level.11 In an attempt to reduce the likelihood of guessing correct answers, only one image was made visible to subjects at a time by folding the booklets in half, and images were presented in various sequences. Testing was conducted at each consecutively higher prism magnitude and began by testing the last level passed at the previous magnitude.

Measurement of Binocular Visual Acuity

Visual acuity was measured at each prism step with both eyes open with habitual correction using linear Snellen type optotypes on a Baylor Visual Acuity Tester (Medtronic Xomed Solan Ophthalmics, Jacksonville, Florida). Since subjects were not diplopic, the measured visual acuity reflected true binocular visual acuity. Different sets of letters were used at each prism level to avoid memorization. The visual acuity was recorded as the finest level where at least half the letters were correctly identified.

We measured distance visual acuity at each of the 15 prism steps to determine whether accommodative convergence was recruited to maintain single vision. As we have described previously,8 accommodation would manifest itself as blur at distance regardless of potential latent hypermetropia; therefore, we did not perform a cycloplegic refraction. Latent hypermetropia would only be an issue if a subject was using his or her entire accommodative reserve to clear a distance target. Since no subjects had near blur either before or after the study, it is unlikely that they were using their entire accommodative reserve to clear the distance target.

Post-Protocol Diplopia

At the conclusion of the protocol, the time to recovery of binocular single vision was recorded for those subjects who were diplopic after the removal of the prisms. In the majority of cases, this was done on a self-report basis where subjects noted the time at which they recovered single vision.

Statistical Analysis

Degradation of stereoacuity was defined as a stereoacuity score greater than 60 seconds of arc, i.e. 100 or 200 seconds of arc or nil. The proportions of subjects with degraded stereoacuity on each test were compared using McNemar’s test.

For subjects whose stereoacuity degraded on either the DR or the FD2, we compared the level of first degradation on the FD2 with the level of first degradation on the DR. The prism magnitudes at which stereoacuity first degraded using the DR and the FD2 were compared by a Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

To assess possible fatigue or adaptation at each prism step, we compared the two stereoacuity values attained with the DR and the two values attained with the FD2. The proportions of stereoacuity values that were greater (worse) at the repeat test than at the initial test at a given step (possible fatigue effect) were compared to the proportions of stereoacuity values that were less (better) at the repeat test than at the initial test (possible adaptation effect).

Results

Twenty subjects aged 18 to 44 years were enrolled in the study (median age, 24). Thirteen (65%) were male and 17 (85%) were Caucasian. All twenty subjects maintained single vision at every prism level (2–40Δ), and therefore visual acuity measured with both eyes open was in fact binocular visual acuity.

Degradation of Stereoacuity with Increasing Convergence Stress

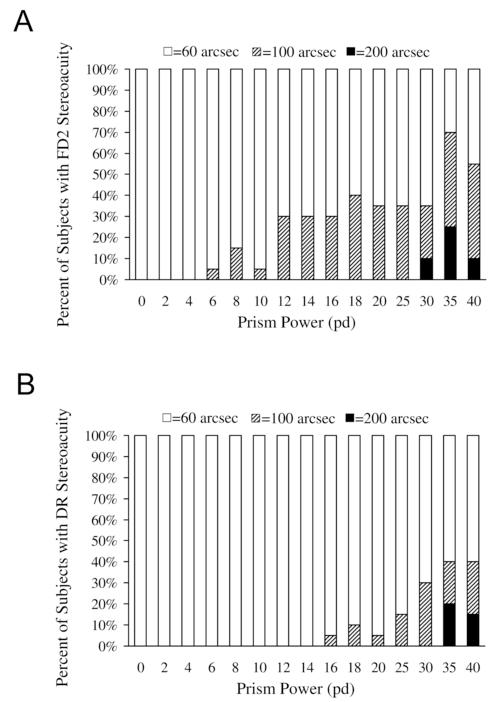

Of 20 subjects, 16 (80%) had degraded stereoacuity on the FD2 at some point during the stepwise sequence of increasing prism-induced convergence stress, whereas only 9 (45%) of 20 subjects had degraded stereoacuity on the DR (P = 0.02, McNemar’s test). At the point of maximal convergence stress (40Δ base-out), 11 (55%) of 20 had degraded stereoacuity on the FD2 (Figure 1A) and 8 (40%) of 20 on DR (Figure 1B). The proportion of subjects with moderate stereoacuity (100 or 200 seconds of arc) on the FD2 generally increased as the convergence stress increased, which occurred similarly but to a lesser extent on the DR.

Figure 1.

(A) Proportion of subjects with distance stereoacuity of 60, 100, and 200 seconds of arc as measured with the Frisby Davis Distance (FD2) stereotest at each prism step. Of 20 subjects, 16(80%) showed degraded stereoacuity at some point during testing. (B) Proportion of subjects with distance stereoacuity of 60, 100, and 200 seconds of arc as measured with the Distance Randot (DR) at each prism step. Nine (45%) of 20 subjects showed degraded stereoacuity at some point during testing.

Prism Magnitude at First Degradation

Of the subjects whose stereoacuity degraded on either distance stereoacuity test, the initial degradation occurred earlier on the FD2 than on the DR (medians: 18Δ [range: 6Δ to no degradationΔ] and 40Δ [range: 16Δ to no degradation] respectively; p = 0.001, Wilcoxon signed-rank).

Control of Convergence Stress

At baseline, all subjects had a control score of 0. For all tested prism levels, subjects had control scores of 0, 1, or 2. A control score of 2 (recovers in >5 seconds) did not occur until the 30Δ level. No subjects had a control score of 3, 4, or 5 (ie, manifestly exotropic) during testing.

Binocular Visual Acuity with Increasing Convergence Stress

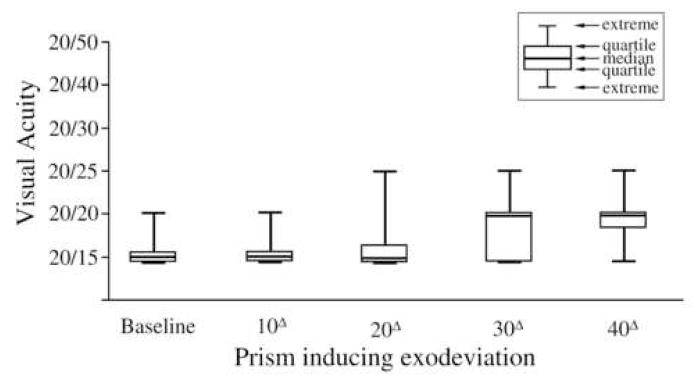

Median binocular visual acuity at baseline (no convergence stress) and at each subsequent level through the 25Δ level was 20/15 (range, 20/15 to 20/25). Median binocular visual acuity at the 30Δ, 35Δ, and 40Δ (maximal convergence stress) levels was 20/20 (range 20/15 to 20/25, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Binocular visual acuity at baseline (i.e. normal seeing conditions) and under conditions of convergence stress, illustrated at the 10Δ, 20Δ, 30Δ, and 40Δ base-out levels. Median binocular visual acuity was 20/15 at the 10Δ and 20Δ levels and 20/20 at the 30Δ and 40Δ levels.

Effect of Adaptation or Fatigue on Stereoacuity

No signs of adaptation or fatigue were observed during the time of testing. For the FD2, the second measure of stereoacuity was equal to the first test on 241 (80%) of 300 instances, greater than the first test (reflecting potential fatigue) on 28 (9%) of 300 instances, and less than the first test (reflecting potential adaptation) on 31 (10%) of 300 instances. For the DR, the repeat measure of stereoacuity was equal to the first test on 274 (91%) of 300 instances, greater than the first test (reflecting potential fatigue) on 18 (6%) of 300 instances, and less than the first test (reflecting potential adaptation) on 8 (3%) of 300 instances.

Post Protocol Diplopia

Immediately after removing the 40 pd base out prism at the conclusion of the protocol, 17 subjects (85%) were temporarily diplopic due to an induced esodeviation. The time to recovery of single vision ranged from 1 minute to 2 hours and 15 minutes.

Discussion

In this follow-up study of prism-induced convergence stress in nonstrabismic subjects, we reversed the order of prisms (increasing rather than decreasing magnitudes) and addressed potential biases of our previous study.8 We confirmed that distance stereoacuity is often degraded in prism-induced convergence stress, and that this degradation is not due to the recruitment of accommodative convergence (median binocular visual acuity at maximum convergence stress was 20/20). We also confirmed that measured thresholds using the FD2 test are degraded more frequently and earlier than those using the DR test. Testing identical disparities with DR and FD2 tests in the current study allowed for direct comparison of stereoacuity thresholds. Testing distance stereoacuity first with the DR, rather than the FD2, controlled for the possibility of better performance on the DR due to prism adaptation in our previous study.8

Subjects in both the current study and our previous study8 did not use accommodative convergence to control the tendency toward exodeviation; rather, they used disparity driven motor convergence. Since we observed no change in distance visual acuity through base-out prisms, we had no evidence of significant convergence accommodation in our study. Other authors have suggested that reduced distance binocular visual acuity in intermittent exotropia is due to accommodative convergence required to control the exodeviation.4 This raises the question of why nonstrabismic subjects use motor convergence to control exodeviations while patients with intermittent exotropia may use accommodative convergence. One possible explanation is that subjects in our study were required to control exodeviations for only 60-90 minutes, and if they were subjected to the exodeviations more persistently, as is the case in intermittent exotropia, accommodative convergence may have been recruited. It is also possible that deterioration in binocular visual acuity in patients with intermittent exotropia is not due to accommodative convergence in the majority of subjects.

We propose that decreased stereoacuity in our subjects under convergence stress is due to a temporary compromise of fine-motor adjustments necessary for fine stereopsis.6,8,12 The motor convergence necessary to maintain single vision with the larger base-out prisms reduces the ability to make precise adjustments of fine-motor fusion. As we have described previously,8 this mechanism has been proposed by Holmes et al6 for patients with intermittent exotropia and Mireskandari et al12 for patients with macular holes. In our nonstrabismic subjects, this transient compromise of fine-motor fusion could explain why subjects in our study had reduced stereoacuity as convergence stress increased.

The current study also confirmed the finding from our initial study8 that degraded distance stereoacuity in subjects with prism-induced exodeviations is more apparent when testing stereoacuity with the real world stereotest, the FD2, than with the random dot test, the DR. This finding is in apparent contrast to intermittent exotropia, where random dot performance is preferentially affected.6 Patients with intermittent exotropia may adapt over an extended period of time to using other cues to perceive depth in every day life, potentially explaining why they perform better on the FD2 than the DR. Also, for patients with intermittent exotropia, the FD2 may be a strong stimulus to fuse, allowing stereoacuity, while the DR may not stimulate fusion to the same extent. Although the reason for the difference in performance on the DR and the FD2 is unclear, it suggests that there are different mechanisms of decreased stereoacuity in the clinical condition of intermittent exotropia and under conditions of prism-induced convergence stress in nonstrabismic subjects..

The important difference between the initial and the current study was the reversal of prism order. In the initial study,8 testing began with the largest prism (40Δ base-out) and proceeded to the smallest prism: all subjects were diplopic at the first level of testing but as the amount of convergence stress was reduced, fusion was suddenly restored. In contrast, the current study tested progressively increasing convergence stress, which we speculate is more analogous to the clinical condition of deteriorating intermittent exotropia than a paradigm of decreasing prism. The observation that all subjects in the current study maintained fusion through the 40Δ level, whereas none could fuse that amount in the initial study,8 shows that there is a difference between maintaining fusion while already fused and regaining fusion while diplopic. In nonstrabismic subjects, this ability to maintain fusion, even when wearing 40Δ base-out prism, might be explained by the slow fusional vergence system adapting to changes in tonic eye position.13 Such adaptations may not occur in the clinical condition of intermittent exotropia. Analogous studies of convergence stress in patients with intermittent exotropia would be informative.

Other investigators have recently shown that nonstrabismic subjects have mild reduction of stereoacuity immediately upon introduction of a base-out prism, with improvement of stereoacuity as the subject adjusts over several minutes.14 Nevertheless, the magnitudes of these changes in stereoacuity are much smaller than the differences between testing levels in our clinical tests.

The primary weakness of the current study is that our experimental design only modelled one aspect of intermittent exotropia, that of vergence stress or deficit. Also, the convergence stress induced in our study was of limited duration, whereas any convergence stress experienced in intermittent exotropia is likely to be sustained over long periods of time. Another difference between our nonstrabismic subjects and the patients with the clinical condition of intermittent exotropia is that nonstrabismic subjects would be expected to experience diplopia when tropic, providing an additional stimulus to fuse, in contrast to patients with intermittent exotropia who often suppress. It is possible that prism-induced changes in interpupillary distance may have resulted in small changes in stereoacuity, but based on a previous report (Frisby J P, Davis H, Edgar R. Does interpupillary distance predict stereoacuity for normal observers? Presented at the European Conference on Visual Perception, Paris, France, 2003), such changes are not likely to be clinically significant. A potential weakness is that we did not repeat testing in individual subjects using the same protocol, but this is offset by studying 20 individuals.

Increasing convergence stress is associated with decreased distance stereoacuity. This degradation does not appear to be due to excessive accommodative convergence. Convergence stress induced by base-out prisms on nonstrabismic volunteers affects performance on real world stereotests, such as the FD2, more than on random dot tests, such as the DR. This finding in normal volunteers under conditions of induced convergence stress is in contrast to intermittent exotropia, where random dot performance appears preferentially degraded.6 There appear to be different mechanisms for reduced distance stereoacuity in intermittent exotropia and under conditions of convergence stress in nonstrabismic subjects.

Acknowledgments

Supported by: National Institutes of Health Grants EY015799 (JMH), Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc., New York, NY (JMH as Olga Keith Weiss Scholar with an unrestricted grant to the Department of Ophthalmology, Mayo Clinic), and Mayo Foundation, Rochester, MN.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented in part at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, May 6-10, 2007.

References

- 1.Govindan M, Mohney BG, Diehl NN, Burke JP. Incidence and types of childhood exotropia. A population-based study. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:104–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pratt-Johnson JA, Barlow JM, Tillson G. Early surgery in intermittent exotropia. Am J Ophthalmol. 1977;84:689–94. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(77)90385-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abroms AD, Mohney BG, Rush DP, Parks MM, Tong PY. Timely surgery in intermittent and constant exotropia for superior sensory outcome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131:111–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00623-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walsh LA, LaRoche GR, Tremblay F. The use of binocular visual acuity in the assessment of intermittent exotropia. J AAPOS. 2000;4:154–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stathacopoulos RA, Rosenbaum AL, Zanoni D, Stager DR, McCall LC, Ziffer AJ, et al. Distance stereoacuity. Assessing control in intermittent exotropia. Ophthalmology. 1993;100:495–500. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(93)31616-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmes JM, Birch EE, Leske DA, Fu VL, Mohney BG. New tests of distance stereoacuity and their role in evaluating intermittent exotropia. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1215–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.06.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hatt SR, Haggerty H, Buck D, Adams WE, Strong NP, Clarke MP. Distance Stereoacuity in Intermittent Exotropia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:219–21. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.099465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laird PW, Hatt SR, Leske DA, Holmes JM. Stereoacuity and binocular visual acuity in prism-induced exodeviation. J AAPOS. 2007;11:362–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2007.01.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohney BG, Holmes JM. An office-based scale for assessing control in intermittent exotropia. Strabismus. 2006;14:147–50. doi: 10.1080/09273970600894716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmes JM, Fawcett SL. Testing distance stereoacuity with the Frisby-Davis 2 (FD2) test. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:193–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu VL, Birch EE, Holmes JM. Assessment of a new distance Randot stereoacuity test. J AAPOS. 2006;10:419–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mireskandari K, Garnham L, Sheard R, Ezra E, Gregor ZJ, Sloper JJ. A prospective study of the effect of a unilateral macular hole on sensory and motor binocular function and recovery following successful surgery. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:1320–4. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.042093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper J. Clinical implications of vergence adaptation. Optom Vis Sci. 1992;69:300–7. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199204000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spencer S, Firth AY. Stereoacuity is affected by induced phoria but returns toward baseline during vergence adaptation. Journal of AAPOS. 2007;11:465–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]