Abstract

It has been suggested that Oct-3/4 may regulate self-renewal in somatic stem cells, as it does in embryonic stem cells. However, recent reports raise the possibility that detection of human Oct-3/4 expression by RT-PCR is prone to artifacts generated by pseudogene transcripts and argue against a role for Oct-3/4 in somatic cells. In this study, we clarified Oct-3/4 expression in mouse somatic tissues using designed PCR primers, which can exclude amplification of its pseudogenes. We found that novel alternative transcripts are indeed expressed in somatic tissues, rather than the normal length transcripts in germline and ES cells. The alternative transcripts indicate the expression of two kinds of truncated proteins. Furthermore, we determined novel promoter regions that are sufficient for the expression of Oct-3/4 transcript variants in somatic cells. These findings provide new insights into the postnatal role of Oct-3/4 in somatic tissues.

Oct-3/4 is one of the earliest transcription factors expressed in the embryo, and its orthologs have been found in many different animal species. The nuclear protein is encoded by a homeobox-containing gene Pou5f1, which belongs to the family of POU (Pit Oct Unc) genes (1-3). It regulates gene transcription by binding DNA to octamer motifs ATGCA/TAAT. For many years, Oct-3/4 has been recognized as a gatekeeper for maintaining pluripotency in embryonic stem (ES)2 cells and pre-implantation embryos. Pluripotent state of ES cells is influenced by expression levels of Oct-3/4 gene (4, 5). More recently, it was demonstrated that mature adult cells could be “reprogrammed” to a very primitive embryonic state via forced expression of four genes (Oct-3/4, c-Myc, Klf-4, and Sox-2) (6); Oct-3/4 is an essential reprogramming factor in this case.

Another line of studies have shown Oct-3/4 expression in somatic stem cells and cancer cells (refer to supplement data in Ref. 7). In mouse epithelial tissues, ectopic expression of Oct-3/4 blocks progenitor cell differentiation and causes dysplasia (8). Another report suggests that Oct-3/4 plays a critical role in the genesis of germ cell tumors (9). In addition, Oct-3/4 expression is reported in adult normal tissues (e.g. hematopoietic and mesenchymal stem cells, pancreatic islets, kidney, brain, etc.). These results suggest that Oct-3/4 may not be only crucial for maintaining pluripotency in pre-implantation embryos and germline cells.

Although many investigators have reported Oct-3/4 expression in a number of somatic stem cells and cancer cells, this remains a controversial and unsolved issue because of the existence of Oct-3/4 pseudogenes. A number of Oct-3/4 pseudogenes have been identified in humans, and some Oct-3/4 pseudogenes have also been suggested in mouse (10-14). Many of the results obtained from previous studies for Oct-3/4 expression in somatic tissues using RT-PCR analysis were confusing because PCR primer sets used in the analysis were unable to clearly distinguish Oct-3/4 from its pseudogenes. In fact, Cantz et al. (14) have recently reported the absence of Oct-3/4 expression in somatic tumor cell lines, and they argue that previous reports of Oct-3/4 expression in various somatic cells could actually be attributed to Oct-3/4 pseudogene expression or misinterpretation of background signals.

In this study, we report isolation and characterization of novel mouse Oct-3/4 transcript variants from somatic tissues. All transcripts lack exon 1 and are transcribed from regions between intron 1 through exon 3 of the Oct-3/4 gene. Two predicted proteins encoded from alternative transcripts could be translated from Met-132 of exon 2 and Met-190 of exon 3, named Oct-3/4B and Oct-3/4C, respectively. Oct-3/4C transformed non-tumorigenic fibroblasts in vitro. Based on these findings, we strongly propose that Oct-3/4 expression and function in adult tissue, including somatic and cancer stem cells, be reconsidered.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals and RT-PCR Analysis—C57BL/6N mice were purchased from SLC (Japan SLC). All animal maintenance and manipulation were performed in accordance with local institutional guidelines. Total RNA were isolated from mouse tissues using TRIzol reagents (Invitrogen). 1 μg of total RNA was used for reverse transcript (RT) reactions. The following PCR primer sequences were used to amplify mouse Oct-3/4 mRNA. The primer set A amplifies exon 1 to exon 4. Forward primer: 5′-CCCCAATGCCGTGAAGTTGGAGAAGGT-3′; Reverse primer: 5′-TCTCTAGCCCAAGCTGATTGGCGATGTG-3′. Primer set B amplifies exon 2 to exon 4. Forward primer: 5′-ATGAAAGCCCTGCAGAAGGAGCTAGAACA-3′; Reverse primer: 5′-TCTCTAGCCCAAGCTGATTGGCGATGTG-3′. G3PDH control primer set is as follows. Forward primer: 5′-ACTACCTTCTTGATGTCATCATA-3′; Reverse primer 5′-CTCAAGATTCTCAGCAATGCTTC-3′. PCR amplification was performed for 35 cycles.

In Situ Hybridization—Postnatal day 1 (P1) mouse eyes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline and subsequently embedded in paraffin. 5-μm thick sections were cut and standard methods for section RNA in situ hybridization were used as described elsewhere. DIG-RNA probes were synthesized from mouse Oct-3/4 cDNA clones distributed from Functional Annotation of Mouse (FANTOM, RIKEN).

Preparation and Spherical Culture of Retinal Cells—Retinal tissues were excised from eyes at P2. To avoid contamination of the ciliary body, the incision was made 1 mm away from the ciliary body. RPE was also completely removed from the retinal tissues. Retinal cells were prepared from the isolated retinal tissues with digestion in a papain-based enzyme system (Sumitomo Bakelite). Dissociated cells were inoculated at 2 × 105 in 1.5 ml of TX-WES medium (ThromboGenics) and incubated in rotation culture. Spheres were cultured for 48 h and collected for RNA analysis.

5′-RACE Analysis—Total RNA was isolated from ES cells, F9 cells, and P1 mouse eyes. Poly(A) RNA was isolated from total RNA using oligo-dT latex beads (Takara). RNA ligase-mediated rapid amplification of 5′ cDNA ends (RLM-RACE) were performed according to protocols of the GeneRacer Kit (Invitrogen). The following reverse primer sequences were used to isolate 5′-cDNA ends of mouse Oct-3/4. Reverse primer 1: 5′-CCGGTTACAGAACCATACTCGAACCACA-3′; Reverse primer 2: 5′-TCTCTAGCCCAAGCTGATTGGCGATGTG-3′. Nested PCR was performed as follows: 1) PCR reactions using the GeneRacer 5′ primer: 5′-CGACTGGAGCACGAGGACACTGA-3′ and reverse primer 1 and 2) PCR reactions using GeneRacer 5′ Nested primer: 5′-GGACACTGACATGGACTGAAGGAGTA-3′ and reverse primer 2. PCR products were ligated into TA-vector (Invitrogen) and sequenced using ABI-3130 sequencer. Accession numbers of DNA sequences are as follows: Clone-1 AB375276, clone-2 AB375272, clone-3 AB375271, clone-4 AB375277, clone-5 AB375274, clone-6 AB375275, and Oct-3/4 derived from F9 cells AB375278.

Electric Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)—Probes for EMSAs were prepared from synthetic oligonucleotides: 5′-CTGACTCCTGCCTTCAGGGTATGCAAATTATTAAGTCTCGAG3-′, which were confirmed by Wei et al. (15) to bind typical octamer binding sites (underline indicates Oct binding sequences), conjugated with biotin at the 3′-end, and annealed with complementary oligonucleotides. Oct-3/4 proteins were prepared by Escherichia coli T7 S30 extract system (Promega). Protein syntheses were confirmed by Western blotting using anti-Oct-3/4 antibody (Becton Dickinson). EMSA was performed with the synthesized proteins for 20 min at room temperature in binding buffer. Following binding, reaction mixtures were run on 6% polyacrylamide gels. Gels were transferred to Biodyne-B membrane (Poll). Blots were then probed with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin (Roche Applied Science), detected by chemiluminescence following the manufacturer's protocol (Roche Applied Science), and visualized using an image analyzer (Fuji).

Reporter Assay—Mouse Oct-3/4 DNA fragments Int-1B (+2707 to +3075), Int-2 (+3071 to +3423), Exo-3 (+3349 to +3525), and Int-1C (+447 to +2798) were amplified by PCR from mouse genomic DNA. PCR primers are as follows: Int-1B forward primer: 5′-TAACTGCTGAGCCATGTGTTTCTTGAGTAA-3′, reverse primer: 5′-GGATCCGTCCTGGGACTGTAGTGAGAAAGGCAGA-3′. Int-2 forward primer: 5′-ATGAAAGCCCTGCAGAAGGAGCTAGAAC-3′, reverse primer: 5′-GGATCCTGAGCTGCAAGGCCTCGAAGCGAC-3′. Exo-3 forward primer: 5′-ACTCTGTTTGATCGGCCTTTCAGGA-3′, reverse primer: 5′-GGATCCTGCACACATCCTGCCACTCCTCACCTCCT-3′. Int-1C forward primer: 5′-GGATCCGTAAGTGAAGGGACTTGGCTGGGCTG-3′, reverse primer: 5′-GGATCCTATTCTGAAGAAGTTTTAAGGCTGCAG-3′. These PCR fragments were subcloned into the multiple cloning site of pGL-4.1-Basic vector (Promega). A series of deletion constructs from positions +448 to +2708 were prepared from Int-1C-pGL-4.1 constructs using the same reverse primer: 5′-AGAGAAATGTTCTGGCACCTGCACTTG-3′ and also the following primers: Int-1D (+1958 to +2798) forward primer: 5′-TGTGCATGCCTGCTACTGTA-3′, Int-1E (+2432 to +2798) forward primer: 5′-CTACTACAGAAGGTTGTGAGCCACCTT-3′, Int-1F (+2606 to +2798) forward primer: 5′-ATTCCCAACAATGGTTCAGTCGCAGCT-3′ Int-1G (+2708 to +2798) forward primer: 5′-TAACTGCTGAGCCATGTGTTTCTTGAGTAA-3′. Int-1A constructs were created from Int-1C-pGL-4.1 constructs using the following primers, sense primer: 5′-GGCAATCCGGTACTGTTGGTAAAGCCACCA-3′, and reverse primer: 5′-GCTCCTCAAAAGACCAAAACTTGTAATCG-3′. Transient transfections of various Oct-3/4 reporter constructs in pGL-4.1 or empty pGL-4.1 were cotransfected with phRG-TK plasmid, using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), into HEK293T cells according to the manufacturer's protocol. After an additional 24 h, lysates were prepared and luciferase activities assayed using the Dual Luciferase Kit (Promega) in an ARVO luminometer (ABI). Firefly luciferase activity was standardized with Renilla luciferase. Three or more experiments were performed for all of the transfections.

Transgenic Mouse—Oct-3/4 DNA fragments, ∼3 kb in length, ranging from intron 1 through exon 3 were amplified from genomic DNA by PCR using the following primers: forward primer: 5′-GGATCCGTAAGTGAAGGGACTTGGCTGGGCTG-3′ and reverse primer: 5′-GCCATGGTGGCCTCGAAGCGACAGATGGTGGTCTGGCTG-3′. PCR fragments were subcloned into BamHI/NcoI-digested pEGFP vector inframe with EGFP-coding sequences (Clontech). Transgenic animals were prepared by standard methods with the support of the Laboratory for Animal Resources and Genetic Engineering at RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology. P2 mouse eyes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and 10-μm frozen sections were prepared (16). Sections were reacted with anti-EGFP antibody conjugated with Alexa-488 and observed. 5 of 12 transgenic mice showed EGFP expression in P2 mouse eye.

Ectopic Expression of Oct-3/4 Variants in Culture Cells—Mouse Oct-3/4-Tag constructs were created from full-length Oct-3/4 cDNA in pBS plasmids (Stratagene) using the following PCR primers: Oct-3/4-Tag forward primer: 5′-TCAGATCCTCTTCTGAGATGAGTTTTTGTTCGTTTGAATGCATGGGAGAGCCCAG-3′, Oct-3/4-Tag reverse primer: 5′-ATAGCGCCGTCGACCATCATCATCATCATCATTGAGAATTCCTGCAGCCCGGGGGAT-3′. Mouse Oct-3/4B-Tag and Oct-3/4C-Tag constructs were created from Oct-3/4-Tag constructs using the following PCR primers: Oct-3/4B Forward primer: 5′-ACCATGGCTATGAAAGCCCTGCAGAAGGAGCTAGAA-3′; Reverse primer: 5′-GAATTCGATATCAAGCTTATCGATA-3′. Oct-3/4C Forward primer: 5′-GCCACCATGGCTATGTGTAAGCTGCGGCCCCTGCTG-3′; Reverse primer: 5′-GAATTCGATATCAAGCTTATCGATA-3′. PCR products were then subcloned downstream of the CMV promoter to create CMV-Oct-3/4-Tag, CMV-Oct-3/4B-Tag, and CMV-Oct-3/4C-Tag. CMV-Oct-3/4-Tag, CMV-Oct-3/4B-Tag, and CMV-Oct-3/4C-Tag plasmids were transfected into HEK293T cells or NIH-3T3 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen).

To isolate stable cell lines, G418 was added to the culture medium after transfection. After 3 weeks, surviving cells were clonally isolated and more than 5 independent lines per DNA construct were obtained. Established cell lines were used for soft agar assays. To exclude the possibility of artificial recombination or deletion of constructs that will lead truncated fragments during the selection process, the full-length of each Oct-3/4 transcript was confirmed using the following PCR primers. Common reverse primer: 5′-CAGAAGAGGATCTGAATAGCGCCGTCGACC-3′; Oct-3/4 forward primer: 5′-ATCGGCCTTTCAGGAAAGGTGTTCAGC-3′; Oct-3/4B forward primer: 5′-ACCATGGCTATGAAAGCCCTGCAGAAGGAGCTAGAA-3′; Oct-3/4C forward primer: 5′-GCCACCATGTGTAAGCTGCGGCCCCTGCTGGA-3′.

Immunocytochemistry—To detect localization of Oct-3/4-Tag, Oct-3/4B-Tag, and Oct-3/4C-Tag proteins in established cell lines, we used anti-Myc antibody (Clontech) and Alexa-488-conjugated second antibody (Invitrogen), and fluorescence was detected using a microscope. Western blot analysis was performed by standard procedures using an anti-Oct-3/4 monoclonal antibody (Becton Dickinson).

Soft Agar Assay—A soft agar assay was carried out in 60-mm culture dishes. Each dish was coated with 4 ml of medium containing 0.55% soft agar. 0.5 × 103 cells were suspended in 3.6 ml of growth medium, mixed with 0.4 ml of 3.3% soft agar, and added to the dishes. Cells were fed weekly with 0.5 ml of medium. After 3 weeks, the colony numbers were counted.

RESULTS

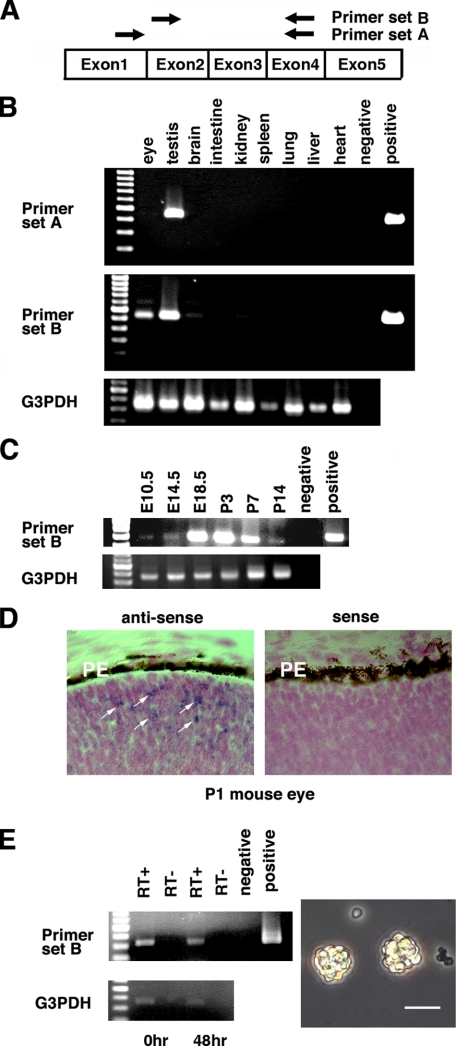

Mouse Oct-3/4 Transcripts Lack Exon 1 in Somatic Tissues—RT-PCR analysis was performed to identify whether or not Oct-3/4 is in fact expressed in somatic tissues. We have analyzed the sequences of mouse Oct-3/4 and its putative pseudogenes by Ensembl Genome browser BLAST search of the mouse genome. Based on this information, we designed PCR primers that can avoid false positive detection of Oct-3/4 expression (supplemental Figs. S1 and S2). PCR reactions were performed using two sense primers and one common antisense primer (Fig. 1A). Primer set A amplifies the region between exon 1 and exon 4 of Oct-3/4 cDNA. Primer set B amplifies regions between exon 2 and exon 4 of Oct-3/4 cDNA. Both PCR reactions gave rise to expected PCR product sizes (459 and 397 bp, respectively). These PCR products were confirmed by DNA sequencing. When PCR primer set A was used for analysis, PCR products were only obtained from testis at P3. In contrast, PCR primer set B produced PCR products in tissues of the eye, brain, and testis (Fig. 1B). We also observed very faint expression in the intestine, kidney, and lung. We did not detect any Oct-3/4 transcripts from Northern blot analysis in newborn mouse eye using total RNA and poly(A) (+) mRNA (data not shown). According to real-time PCR results, the eye expresses about 10% and the brain expresses only 0.3% of the Oct-3/4 transcript numbers seen in the testis of P1 mouse, while other somatic tissues contained no significant levels of Oct-3/4 expression (data not shown). We, therefore, decided to focus our attention on the eye as a representative example of a somatic tissue that expresses Oct-3/4 transcripts.

FIGURE 1.

Expression of Oct-3/4 alternative transcripts in newborn mouse tissues. A, schematic illustration of PCR primer for Oct-3/4. B, RT-PCR analysis of mouse Oct-3/4 transcripts in P3 mouse tissues. Both RT-PCR reactions produced expected PCR product sizes (459 and 397 bp, respectively). C, Oct-3/4 expression during eye development. D, in situ hybridization of Oct-3/4 transcripts in P1 mouse eye. White arrows indicate positive signals observed in the neuroblastic layer. Abbreviations: PE, retinal pigment epithelium. E, left panel indicates expression of Oct-3/4 in dissociated retinal cells (0 h) and retinal spheres (48 h) by RT-PCR analysis. Right panel shows retinal spheres cultured for 48 h in vitro. Scale bar, 50 μm.

We analyzed Oct-3/4 expression during mouse eye development using RT-PCR (Fig. 1C). RT-PCR products were first observed at embryonic day 10.5 (E10.5). Expression levels of Oct-3/4 transcripts in the eye reached a peak level at E18.5 and were maintained until P3, after which expression of Oct-3/4 transcripts gradually declined. Oct-3/4 mRNA expression could not be detected in the adult eye under similar PCR conditions (data not shown). We next tried to identify which part of the postnatal eye expresses Oct-3/4 transcripts by in situ hybridization. Using P1 mouse eye sections, positive signals were observed in some cells of the neuroblastic layer adjacent to the pigment epithelium layer (Fig. 1D). These results indicate that a small number of cells significantly express Oct-3/4 in newborn mouse retina.

Next we tried to examine Oct-3/4 expression in retinal spheres obtained from P2 retina. In newborn rodents, it has been recognized that some retinal progenitor cells could form spheres (17). Sphere formation is recognized as a marker of stem cell behavior. When P2 retinal cells were isolated and cultured in vitro, there were not many viable single cells observed after 48 h. Next to the small number of single cells, retinal spheres could be observed (Fig. 1E). To examine Oct-3/4 expression in these retinal spheres, we collected retinal spheres and isolated total RNA for RT-PCR analysis. The PCR product was detected when primer set B was used (Fig. 1E). RLM-RACE results showed Oct-3/4 transcripts that lack exon 1 were obtained (data not shown). These results suggest that alternative transcripts of Oct-3/4 are expressed in postnatal retina and retina-derived spheres.

Alternative Variants of Mouse Oct-3/4 Transcripts—As RT-PCR analysis suggested that Oct-3/4 transcripts lack exon 1, we performed RLM-RACE to identify the transcriptional start site in the eye.

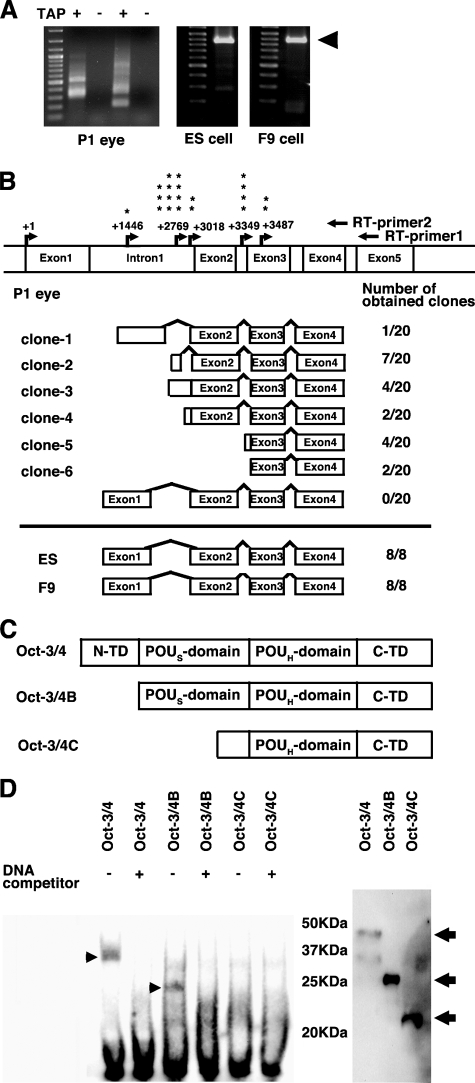

When the RLM-RACE method was performed on ES and F9 cells, major products that matched the region between exon 1 through exon 4 of Oct-3/4 transcripts were observed (Fig. 2A). The nucleotide sequences of these clones were identical to the previously reported mouse Oct-3/4 sequence. In the case of the P1 mouse eye, major Oct-3/4 products observed in ES and F9 cells were absent (Fig. 2A). Surprisingly, PCR products obtained from P1 eye varied from 169 to 992 bp, while canonical Oct-3/4 (including exon 1 through exon 4) produced 855 bp product sizes. Sequencing analysis of these PCR products revealed the existence of several alternative Oct-3/4 transcripts in the eye (Fig. 2B). It should be noted that we were unable to amplify the pseudogenes as all obtained clones were identical to the genomic sequences of intron 1 through exon 4 of mouse Oct-3/4 gene (supplemental Fig. S3). We categorized Oct-3/4 RLM-RACE products into six groups depending on their transcription initiation sites and splicing variants (Figs. 2B and supplemental S4). Four of six groups initiated transcription from the internal region of intron 1 (clones-1 to -4). The remaining two groups, clones-5 and -6, initiated transcription from internal regions of intron 2 and exon 3, respectively. From the number of RLM-RACE products, alternative Oct-3/4 transcripts appear to be dominantly expressed 277-298-bp upstream of the intron 1 and exon 2 boundaries.

FIGURE 2.

Novel Oct-3/4 transcripts in mouse eye. A, RLM-RACE products obtained from P1 mouse eye, ES, and embryonal carcinoma F9 cells. Left panel indicates RLM-RACE products of Oct-3/4 from the P1 mouse eye. Each lane shows independent PCR reactions. RNA is treated with or without tobacco acid pyrophosphatase (TAP). B, schematic illustration of Oct-3/4 clones obtained by RLM-RACE. Arrows indicate transcriptional initiation sites in mouse Oct-3/4 gene. Asterisks indicate the numbers of clones obtained from each transcription initiation site. C, two predicted mouse Oct-3/4 isoforms. Deduced mouse Oct-3/4B and Oct-3/4C consists of 221 and 163 amino acids, respectively. D, DNA binding ability of Oct-3/4 isoforms. Left panel, indicates EMSA results of Oct-3/4 isoforms. Arrowheads indicate specific Oct-3/4 proteins with Oct recognition sequences. Right panel indicates Western blots of in vitro translated mouse Oct-3/4 isoforms. Arrows indicate Oct-3/4 protein products.

In clone-2, splicing occurred between the intron 1 splice donor and the exon 2 splice accepter. An ATG sequence 10-bp downstream of the intron 1/exon 2 boundary may serve as an in-frame initiation site capable of translating the Oct-3/4 coding sequence. The initiation site in clone-2 (GACATGA) matches the minimal consensus Kozak sequence (minimal Kozak consensus sequences are (A/G)XXATGX or XXXATGG) (18), and the POU specific domain and POU homeodomain remain intact even though exon 1 is absent. We designated clone-2 mouse Oct-3/4B (Fig. 2C). In clone-3, the transcriptional initiation site is similar to that of clone-2, but transcripts are read through to exon 2 without splicing, as clone-3 has several ATG sequences upstream of exon 2 that would result out-of-frame of Oct-3/4 coding sequences. The longest isolated clone was 992-bp long (clone-1). This clone also had a splice donor site 586-bp downstream of the transcriptional initiation site, although starting translation from the first ATG would result in out-of-frame Oct-3/4 coding sequences. Clone-5 is translated from intron 2, and its first ATG (AACATGT) can be translated in-frame to the Oct-3/4 sequence and also resembles a minimal Kozak consensus sequence. Clone-5 consists of a truncated POU specific domain and a complete POU homeodomain. This clone-5 is designated as mouse Oct-3/4C (Fig. 2C). The shortest clones are 169-bp long that were transcribed from 36-bp downstream of intron 2 and exon 3 boundaries (clone-6). As these clones are initiated from inside exon 3, one may argue that these clones may be produced by incomplete dephosphorylation treatment of RLM-RACE method. However, we isolated two independent clones from different batches of PCR products, suggesting these products are not artifacts. The first ATG appearing in clone 6 results in out-of-frame Oct-3/4 coding sequences.

DNA Binding Properties of Mouse Oct-3/4B and Oct-3/4C—Mouse Oct-3/4B contains the complete POU specific domain and POU homeodomain, similar to canonical Oct-3/4. Oct-3/4C, on the other hand, has a truncated POU specific domain and a complete POU homeodomain. EMSA was performed to determine whether or not these Oct-3/4 isoforms can bind to the authentic Oct-3/4 DNA recognition sequence. Results showed that full-length mouse Oct-3/4 and Oct-3/4B could bind to the consensus Oct-3/4 DNA-recognition sequence while Oct-3/4C could not (Fig. 2D). The binding ability of Oct-3/4 and Oct-3/4B diminished when excess competitor was added to the samples.

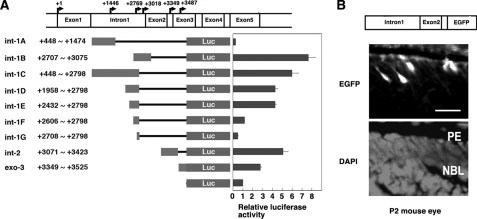

Basal Promoter Activity in the Regions of Intron 1 through Exon 3—To identify basal transcription regulatory regions in 5′-flanking regions of isolated clones, a series of mouse Oct-3/4 constructs containing different sized fragments of intron 1 to exon 3 regions were introduced upstream of the firefly luciferase reporter gene and tested in HEK293T cells (Fig. 3A). Maximal promoter activity was detected from the int-1B constructs. Promoter activity was also high in int-1C constructs. Deletion of int-1C constructs (int-1D, int-1E, int-1F, and int-1G) revealed that only a weak promoter activity existed in int-1F constructs; this suggests the presence of enhancer elements between +2432 and +2606. Int-1A and int-1G showed lower activity than the control pGL4.1-Basic construct, suggesting the presence of repressor elements. A 5-fold and 3-fold increase in luciferase activity was detected for Int-2 and exo-3 constructs, respectively, over the control construct.

FIGURE 3.

Novel transcriptional control regions of mouse Oct-3/4 gene. A, the structures of different fragments of intron 1 through exon 3 of mouse Oct-3/4 gene ligated into luciferase plasmid. Arrows indicate transcription initiation site. Reporter activities are presented as bar graphs. B, activity of Oct-3/4-EGFP in mouse eye. Schematic illustration of Oct-3/4-EGFP transgene construct. EGFP-positive signals are found in retina of transgenic P2 mouse (upper panel). Abbreviations: PE, retinal pigment layer; NBL, neuroblastic layer. Scale bar, 20 μm. Lower panel indicates DAPI nuclear staining.

As HEK293T cells do not internally express Oct-3/4 (data not shown), we next examined whether this region of the Oct-3/4 gene can also function in postnatal mouse eye by producing transgenic animals. Genomic DNA fragments containing mouse Oct-3/4 intron 1 through exon 3 regions were amplified by PCR and ligated into the upstream region of the EGFP reporter gene. EGFP-positive cells were found in the neuroblastic layer in the transgenic mouse retina (Fig. 3B), which was consistent with the results from in situ hybridization analysis. These results indicate that the region between intron 1 and exon 3 of mouse Oct-3/4 gene is sufficient for its expression in the P2 mouse eye.

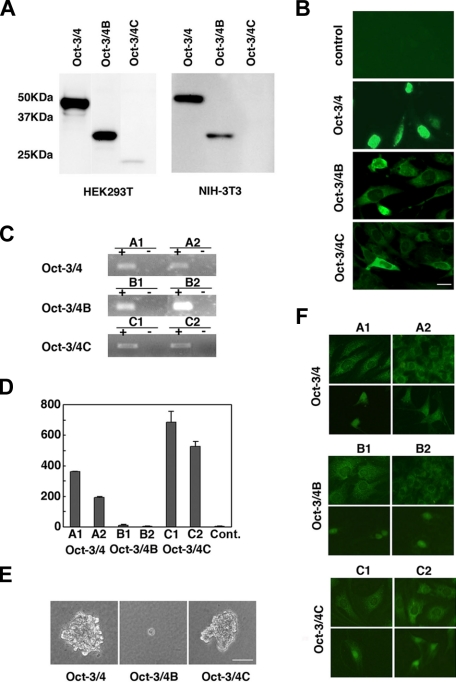

Ectopic Expression of Oct-3/4 Variants in Culture Cells—Cellular localization and protein synthesis of transiently expressed Oct-3/4 variants were examined in NIH-3T3 cells and HEK293T cells. In HEK293T cells, which express at higher level because of the stable expression of large T-antigen, predicted protein sizes were synthesized from all three Oct-3/4 constructs (Fig. 4A). Oct-3/4C signal intensity was very low in comparison to Oct-3/4 and Oct-3/4B. In the case of NIH-3T3 cells, Oct-3/4C protein could not be detected, while Oct-3/4 and Oct-3/4B were detected from Western blot analysis (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4.

Soft agar colony growth of NIH-3T3 cells ectopically expressing Oct-3/4 variants. A, Western blots of protein lysed from HEK293T or NIH-3T3 cells transfected with each Oct3/4 variant. B, immunofluorescence staining with anti-Myc tag antibody in transiently expressing Oct-3/4 variants or control vector. Scale bar, 25 μm. C, detection of Oct-3/4 transcripts in isolated independent lines that stably express Oct-3/4, Oct-3/4B, and Oct-3/4C. Transcripts were detected by RT-PCR using specific primers. D, colony formation in soft agar of NIH-3T3 cells stably transfected with CMV-Oct-3/4, CMV-Oct-3/4B, or CMV-Oct-3/4C expression vector. Colony numbers of each cell line were counted after culturing for 3 weeks and are presented in a bar graph. E, morphology of typical soft agar colony derived from stably transfected NIH-3T3 cell lines. Scale bar, 25 μm. F, immunofluorescence staining with anti-Myc tag antibody in stably transfected cell lines.

Cellular localization of Oct-3/4 variants in NIH-3T3 cells was examined using anti-Myc tag antibody. Myc-tagged Oct-3/4 was mainly localized in the nucleus, whereas most of Myc-tagged Oct-3/4B and Oct-3/4C were predominantly observed in the cytoplasm (Fig. 4B).

Mouse Oct-3/4C, but Not Oct-3/4B, Transforms NIH-3T3 Cells—Oct-3/4 has been previously shown to transform nontumorigenic fibroblasts in vitro (9). Here, we tested the oncogenic potential of Oct-3/4 isoforms. Non-tumorigenic NIH-3T3 fibroblast cells were transfected with the Oct-3/4 variants inserted in expression vectors or a control vector, and each stable cell line was isolated. RT-PCR analysis using specific primer sets confirmed the expression of full-length of the three constructs in each line (Fig. 4C).

Two independent lines from each group were assayed for their ability to grow in soft agar. NIH-3T3 wild-type cells, as well as those harboring only control vectors, did not form any colonies (Fig. 4D). Remarkably, expression of Oct-3/4 or Oct-3/4C stimulated the formation of robust colonies in soft agar, while Oct-3/4B produced only a small number of colonies (Fig. 4, D and E).

Intracellular Locations of Oct-3/4 Variants in Stable Lines—Localization of Oct-3/4, Oct-3/4B, and Oct-3/4C were examined in isolated stable cell lines. Interestingly, cellular localization of all three constructs was observed in the nucleus or cytoplasm under the same culture dishes (Fig. 4F). These similar staining patterns were obtained from more than 5 lines per each construct. We found each Oct-3/4 isoform had a tendency to localize in the cytoplasm at the higher density. Signal intensities in cell lines seemed to be very faint compared with the transiently expressed cells. Although cellular localization could be observed in all isolated stable lines, the levels of protein expression were undetectable on Western blot analysis (data not shown). These results suggest that protein levels of Oct-3/4 isoforms might be relatively low in stably transfected NIH-3T3 lines.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we clearly demonstrate the existence of Oct-3/4 alternative transcripts in mouse somatic tissues. These results were obtained using newly designed PCR primer sets that are capable of distinguishing between Oct-3/4 and Oct-3/4 pseudogenes. Sequencing analysis for PCR products confirmed that these PCR primer sets are useful only for amplifying mouse Oct-3/4 transcripts.

RLM-RACE results show there are several transcripts in which transcription is initiated from regions between intron 1 through exon 3 of the mouse Oct-3/4 gene. Alternatively spliced variants of human Oct-3/4 have been proposed, but only a few attempts have been made so far (12). Recently, human Oct-3/4 variants were also reported from Gonadoblastoma (19). Human Oct-3B from islets tissue lack exon 1 and the transcripts are thought to be derived from alternative splicing of the Oct-3/4 gene (20, 21). Presently, however, the predicted amino acids of human Oct-3B has been corrected to initiate from the ATG found in exon 3 (refer to GenBank™ accession number NM203289), similar to the Oct-3/4C we have designated here. In contrast, our mouse RLM-RACE products indicate the existence of capping sites in obtained clones. Mouse Oct-3/4 alternative variants are, therefore, transcribed from regions between intron 1 through exon 3, and are not formed by alternative splicing from long premature mRNA transcribed in the 5′-upstream region of exon 1. These findings offer us a good opportunity to study a previously unknown role of Oct-3/4 transcript variants.

We have demonstrated the expression of Oct-3/4 variants during postnatal development of the eye and retinal spheres derived P2 mouse retina. At this stage, retinal spheres can form when dissociated and cultured in vitro (17) but it remains unknown which types of retinal cells can indeed form spheres in vitro. Characterization of Oct-3/4 variant-expressing cells in neuroblastic layer indicates that those cells have different characteristics from retinal progenitors and possess both properties of stem cell-like and differentiated neurons.3

Until now, most functions of Oct-3/4 were obtained from studies of ES cells, and recent controversial issues of Oct-3/4 expression in somatic cells tend to reject the notion of Oct-3/4 expression in somatic cells. In this study we identified novel gene transcripts of Oct-3/4 expressed in mouse somatic tissues (eye and brain) and retina-derived spherical cultures, distinct from the Oct-3/4 transcripts in germline and ES cells. These observations suggest a novel role of Oct-3/4 variants in somatic tissue, which correlates Oct-3/4 expression and stem cell behavior. Even though Oct-3/4 functions in somatic stem cells are thought to be dubious at present, it is worth reinvestigating Oct-3/4 variant expression in these cells.

Regions of intron 1 through exon 3 of the mouse Oct-3/4 gene shows that promoter activity is sufficient to drive the EGFP reporter gene in postnatal mouse eye. We cannot exclude the possible existence of enhancer regions that may cooperate with the novel promoter region in somatic cells. As Oct-3/4 is also expressed in the brain and other tissues, it is necessary to study whether the same promoter region is utilized for Oct-3/4 expression in these tissues. This finding is also significant because the transcription regulatory region for somatic Oct-3/4 expression is different from previously recognized regulatory regions (22-24). To date, only the upstream region of exon 1 has been extensively studied for Oct-3/4 gene enhancer and promoter activities. Epigenetic control of the Oct-3/4 gene has also been examined in the upstream region of exon 1 enhancer and promoter regions using different cell lines and somatic tissues (14, 25-27). These results indicate a correlation between Oct-3/4 expression and methylation states of enhancer and promoter regions of the Oct-3/4 gene. Our present data, however, indicate that these previous studies are not sufficient to test novel Oct-3/4 transcript expression in somatic cells, and further epigenetic studies are necessary in the newly identified transcription regulatory regions of mouse Oct-3/4 gene.

The existence of several transcript variants raises the possibility that two predicted Oct-3/4 isoforms exist in somatic cells (Fig. 2C). EMSA demonstrated that mouse Oct-3/4B, but not Oct-3/4C, can bind to typical Oct binding sequences. This is logical as Oct-3/4C has a truncated POU specific domain necessary for DNA interaction (3). Nevertheless, Oct-3/4C induces significant transformation activity in NIH-3T3 cells. This unexpected result suggests Oct-3/4C could play a yet undetermined role in the cells. Although Oct-3/4C only has the POU homeodomain to interact with DNA, this POU homeodomain is known to interact directly with other transcription factors like Sox-2 (28-30). One theory to explain Oct-3/4C function in NIH-3T3 cells is that Oct-3/4C is recruited to bind target DNA sequences through interaction with other factors found in NIH-3T3 cells. It is reasonable to assume that deregulated Oct-3/4 expression in somatic cells can cause a transformed phenotype similar to cancer cells. Thus it will be very interesting to test whether or not Oct-3/4 isoforms are actually expressed in cancer cells.

In contrast, mouse Oct-3/4B showed no transformation activity in NIH-3T3 cells. Niwa et al. (31) demonstrated that the deleted N-terminal transactivation domain (N-TD) constructs of mouse Oct-3/4, which resembles mouse Oct-3/4B, have sufficient activity to maintain self-renewal of ZHBTc4 ES cells. These differences may be caused by the phosphorylation states of the C-terminal transactivation domains (C-TD) and that this C-TD is subject to cell type-specific regulation mediated by the Oct-3/4 POU domain (32). Thus, our results strongly suggest that the two novel isoforms of Oct-3/4 possess distinct activities in somatic cells.

In stable transformant lines, full-length exogenous Oct-3/4 target transcript was confirmed by RT-PCR and localization of Oct-3/4 variants was detected by immunocytochemistry using anti-Myc tag antibody. Nevertheless, we cannot detect the predicted proteins by Western blot analysis using both anti-Oct-3/4 and anti-Myc tag antibodies. In transient transfection experiments, we were able to detect Oct-3/4 and Oct-3/4B in both HEK293T and NIH-3T3 cells, but Oct-3/4C was only faintly detected in HEK293T cells even though the same construct was utilized in each experiment. From undetectable levels of Oct-3/4C in NIH-3T3 cells and very little amounts of Oct-3/4C in HEK293T cells, we speculate that either degradation of Oct-3/4C may be faster than other Oct-3/4 or translation of Oct-3/4C may be down-regulated in these cells. In a previous report, exogenous full-length Oct-3/4 proteins were detected in similar experiments using Swiss-3T3 cells (9). These differences may be due to different promoter activity used in each experiment. Our results indicate that protein levels of each Oct-3/4 isoform are not very high, but may be enough to function in NIH-3T3 cells.

In fact, we did not detect any Oct-3/4 protein from Western blot and immunohistochemical analysis. These results suggest that functional levels of Oct-3/4 in somatic cells may be much lower than those in pluripotent states, such as ES or germ line cells (4-5).

In addition, there is a marked difference in Oct-3/4 localization between transfected and ES cells. It is well known that Oct-3/4 has nuclear localization signals (33). Nevertheless every Oct-3/4 isoform was observed in both nucleus and cytoplasm in established NIH-3T3 lines stably expressing Oct-3/4. Interestingly, the localization patterns differed among the cells from the same culture (Fig. 4F). It is possible that some transport factors such as the Importin-α families regulate Oct-3/4 to transport into the nucleus, in response to cell proliferation state (34). In contrast, transient expression of Oct-3/4 localizes primarily in the nucleus as observed in ES cells. Transient expression of Oct-3/4B and Oct-3/4C, however, localizes mainly in the cytoplasm. Transient expression of human Oct-3B also localizes in the cytoplasm (21). Combining the transient expression results obtained from both human and mouse Oct-3/4B suggests that N-TD may contain a nuclear export signal. Additional experiments are needed to reveal the difference in localization of Oct-3/4 between stable cell lines and transiently expressed cells. Our findings indicate that careful consideration is necessary to exclude Oct-3/4 expression in somatic cells even if the protein levels and the localization pattern were quite different from those in ES or germline cells.

Although we found novel transcript variants of the Oct-3/4 gene expressed in postnatal eye tissue, it remains unclear whether the isoforms play a physiological role in somatic tissue or cancer cells. Recently Oct-3/4 conditional knock-out mice have been used to study Oct-3/4 functions in somatic stem cells (7). That group surveyed a number of organisms and cells believed to contain Oct-3/4 transcripts, but did not detect any difference between normal and knock-out mouse, and concluded that Oct-3/4 is not required for mouse somatic stem cell self-renewal. Their knock-out construct was created by the deletion of only exon 1 by floxed loxP sites (35). The results from this study seem very compatible with our finding that full-length Oct-3/4 was not detected in somatic tissue. Based on our present study, the complete abolition of Oct-3/4 expression requires deletion downstream of exon 1. To this end, we are now generating a conditional knock-out mouse in which Oct-3/4 exon 2 through exon 5 is floxed by loxP sites, to gain a better understanding of the physiological roles of Oct-3/4 in somatic cells. We believe that this approach will reveal whether Oct-3/4 can function in somatic stem cells in the near future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Yuka Nakatani for helpful assistance and Hazuki S. Hiraga for helpful reading of manuscripts. We also thank Drs. Hans R. Schöler, Yoshiki Sasai, and Hiroshi Sasaki for the kind gifts of GOF-18 plasmid, mouse ES, and HEK293T cell lines, respectively. We acknowledge the Laboratory for Animal Resources and Genetic Engineering (LARGE) of Center for Developmental Biology (CDB) for producing the transgenic embryos.

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid to the Leading Project and 19592048 (to M. K.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1-S4.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: ES, embryonic stem; RT, reverse transcription; RLM-RACE, RNA ligase-mediated rapid amplification of 5′ cDNA ends; EMSA, electric mobility shift assay; EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

M. Kosaka et al., unpublished data.

References

- 1.Schöler, H. R., Hatzopoulos, A. K., Balling, R., Suzuki, N., and Gruss, P. (1989) EMBO J. 8 2543-2550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schöler, H. R., Ruppert, S., Suzuki, N., Chowdhury, K., and Gruss, P. (1990) Nature 344 435-439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okamoto, K., Okazawa, H., Okuda, A., Sakai, M., Muramatsu, M., and Hamada, H. (1990) Cell 60 461-472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nichols, J., Zevnik, B., Anastassiadis, K., Niwa, H., Klewe-Nebenius, D., Chambers, I., Schöler, H., and Smith, A. (1998) Cell 95 379-391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niwa, H., Miyazaki, J., and Smith, A. G. (2000) Nat. Genet. 24 372-376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takahashi, K., and Yamanaka, S. (2006) Cell 126 663-676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lengner, C. J., Camargo, F. D., Hochedlinger, K., Welstead, G. G., Zaidi, S., Gokhale, S., Schöler, H. R., Tomilin, A., and Jaenisch, R. (2007) Cell Stem Cell 1 403-415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hochedlinger, K., Yamada, Y., Beard, C., and Jaenisch, R. (2005) Cell 121 465-477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gidekel, S., Pizov, G., Bergman, Y., and Pikarsky, E. (2005) Cancer Cell 4 361-370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pain, D., Chirn, G. W., Strassel, C., and Kemp, D. M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 6265-6268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suo, G., Han, J., Wang, X., Zhang, J., Zhao, Y., and Dai, J. (2005) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 337 1047-1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liedtke, S., Enczmann, J., Waclawczyk, S., Wernet, P., and Kögler, G. (2007) Cell Stem Cell 1 364-366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin, H., Shabbir, A., Molnar, M., and Lee, T. (2007) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 355 111-116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cantz, T., Key, G., Bleidissel, M., Gentile, L., Han, D. W., Brenne, A., and Schöler, H. R. (2008) Stem Cells 26 692-697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wei, F., Schöler, H. R., and Atchison, M. L. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 21551-21560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asami, M., Sun, G., Yamaguchi, M., and Kosaka, M. (2007) Dev. Biol. 304 433-446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engelhardt, M., Wachs, F. P., Couillard-Despres, S., and Aigner, L. (2004) Exp. Eye Res. 78 1025-1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kozak, M. (1983) Cell 34 971-978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palma, I., Pena, R. Y., Contreras, A., Ceballos-Reyes, G., Coyote, N., Erana, L., Kofman-Alfaro, S., and Queipo, G. (2008) Cancer Lett. 263 204-211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takeda, J., Seino, S., and Bell, G. I. (1992) Nucleic Acids Res. 20 4613-4620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee, J., Kim, H. K., Rho, J. Y., Han, Y. M., and Kim, J. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 33554-33565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okazawa, H., Okamoto, K., Ishino, F., Ishino-Kaneko, T., Takeda, S., Toyoda, Y., Muramatsu, M., and Hamada, H. (1991) EMBO J. 10 2997-3005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minucci, S., Botquin, V., Yeom, Y. I., Dey, A., Sylvester, I., Zand, D. J., Ohbo, K., Ozato, K., and Schöler, H. R. (1996) EMBO J. 15 888-899 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yeom, Y. I., Fuhrmann, G., Ovitt, C. E., Brehm, A., Ohbo, K., Gross, M., Hübner, K., and Schöler, H. R. (1996) Development 122 881-894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hattori, N., Nishino, K., Ko, Y. G., Hattori, N., Ohgane, J., Tanaka, S., and Shiota, K. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 17063-17069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deb-Rinker, P., Ly, D., Jezierski, A., Sikorska, M., and Walker, P. R. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 6257-6260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feldman, N., Gerson, A., Fang, J., Li, E., Zhang, Y., Shinkai, Y., Cedar, H., and Bergman, Y. (2006) Nat. Cell Biol. 8 188-194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Botquin, V., Hess, H., Fuhrmann, G., Anastassiadis, C., Gross, M. K., Vriend, G., and Schöler, H. R. (1998) Genes Dev. 12 2073-2090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ambrosetti, D. C., Schöler, H. R., Dailey, L., and Basilico, C. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 23387-23397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okumura-Nakanishi, S., Saito, M., Niwa, H., and Ishikawa, F. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 5307-5317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niwa, H., Masui, S., Chambers, I., Smith, A. G., and Miyazaki, J. (2002) Mol. Cell Biol. 22 1526-1536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brehm, A., Ohbo, K., and Schöler, H. (1997) Mol. Cell Biol. 17 154-162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pan, G., Qin, B., Liu, N., Schöler, H. R., and Pei, D. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 37013-37020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yasuhara, N., Shibazaki, N., Tanaka, S., Nagai, M., Kamikawa, Y., Oe, S., Asally, M., Kamachi, Y., Kondoh, H., and Yoneda, Y. (2007) Nat. Cell Biol. 9 72-79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kehler, J., Tolkunova, E., Koschorz, B., Pesce, M., Gentile, L., Boiani, M., Lomeli, H., Nagy, A., McLaughlin, K. J., Schöler, H. R., and Tomilin, A. (2004) EMBO Rep. 5 1078-1083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.