Abstract

Ynt1 is the sole high affinity nitrate transporter of the yeast Hansenula polymorpha. It is highly regulated by the nitrogen source, by being down-regulated in response to glutamine by repression of the YNT1 gene and Ynt1 ubiquitinylation, endocytosis, and vacuolar degradation. On the contrary, we show that nitrogen limitation stabilizes Ynt1 levels at the plasma membrane, requiring phosphorylation of the transporter. We determined that Ser-246 in the central intracellular loop plays a key role in the phosphorylation of Ynt1 and that the nitrogen permease reactivator 1 kinase (Npr1) is necessary for Ynt1 phosphorylation. Abolition of phosphorylation led Ynt1 to the vacuole by a pep12-dependent end4-independent pathway, which is also dependent on ubiquitinylation, whereas Ynt1 protein lacking ubiquitinylation sites does not follow this pathway. We found that, under nitrogen limitation, Ynt1 phosphorylation is essential for rapid induction of nitrate assimilation genes. Our results suggest that, under nitrogen limitation, phosphorylation prevents Ynt1 delivery from the secretion route to the vacuole, which, aided by reduced ubiquitinylation, accumulates Ynt1 at the plasma membrane. This mechanism could be part of the response that allows nitrate-assimilatory organisms to cope with nitrogen depletion.

Nitrate can be used as single nitrogen source for plants, algae, fungi, and several yeast species (1-5). Nitrate assimilation consists of nitrate transport into the cells and its reduction by nitrate reductases to ammonium, which feeds a set of reactions for the synthesis of glutamate and glutamine (5). Because the use of nitrate requires a high energy investment and brings about toxicity due to nitrite accumulation, genes encoding the machinery for nitrate assimilation are generally affected by nitrogen catabolite repression, and hence nitrate is only assimilated in those environments where favorable nitrogen sources such as ammonium or glutamine are absent (6). Additionally, post-translational regulation of the enzymes and permeases involved in nitrate assimilation is important for the short term response of the pathway to a changing environment (6, 7).

Nitrate is the main inducer of genes encoding permeases and enzymes involved in its assimilation. In plant, algae, fungi, and yeast, nitrate acts as inducer once it enters the cell (8, 9). These facts entail that nitrate transporters play a key role in regulating the influx of nitrate, which is the substrate and the gene inducer of the nitrate assimilation pathway. The nitrate-assimilatory yeast Hansenula polymorpha possesses a sole nitrate transporter (Ynt1) responsible for the high affinity transport of nitrate and nitrite into the cell (10, 11). Post-translational regulation of nitrate transporters in eukaryotes remains somewhat unknown. This kind of regulation would allow fine adjustments of nitrate influx to the cell and, indirectly, the induction of genes involved in nitrate assimilation, at least in those organisms where nitrate is sensed intracellularly, such as H. polymorpha (8, 9). Current knowledge about post-transcriptional regulation of nitrate transport derives from Arabidopsis thaliana NRT1;1 (formerly designated CHL1) and the H. polymorpha Ynt1, which represent respectively, two different families of nitrate transporters and different modes of regulation. In the first case, it has been described that protein kinase A-dependent phosphorylation of AtNRT1;1 modifies the affinity of this dual-affinity transporter for nitrate. Phosphorylation of AtNRT1;1, which increases affinity for nitrate, is stimulated when plants are exposed to a low concentration of nitrate, whereas the transporter is dephosphorylated at high nitrate concentration (12). Furthermore, we have reported that the nitrogen source controls the amount of Ynt1; glutamine or ammonium triggers its ubiquitinylation, endocytosis, and vacuolar degradation (13). Ynt1 endocytosis requires ubiquitinylation in lysine residues of the central intracellular loop of Ynt1. Interestingly, nitrogen limitation renders the lowest levels of Ynt1 ubiquitinylation, and consequently it accumulates at the plasma membrane. More recently, it has been suggested that nitrate transporters NrtA and NRT2.1 from Aspergillus nidulans and Arabidopsis thaliana undergo post-translational regulation but the molecular mechanisms are so far unknown (7, 14, 15).

Nitrogen limitation induces a set of cellular responses aimed at assuring survival. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the early response consists in maintaining the intracellular content of nitrogen by increasing the activities of permeases responsible for the uptake of nitrogen sources. Likewise, the expression of the enzymes involved in the synthesis of glutamate and glutamine are also up-regulated (16). Yeast whole genome analysis response to nitrogen starvation shows another cluster of genes involved in more complex phenomena, including induction of pseudohyphal morphology, sexual reproduction, and autophagy (17). Apart from the effect of nitrogen deprivation on the expression of the genes encoding nitrogen permeases, the fate of newly synthesized permeases en route to the plasma membrane is also modified. S. cerevisiae Gap1 and Tat2 constitute two well studied examples of different types of amino acid permeases that respond differentially to the nitrogen limitation. Gap1 transports all naturally occurring amino acids, whereas Tat2 specifically transports tryptophan and other aromatic amino acids. In addition to being subjected to endocytosis, the nitrogen availability regulates the intracellular traffic of both permeases to the plasma membrane. Although nitrogen limitation produces high levels of Gap1 in the plasma membrane, the presence of all natural occurring amino acids and several amino acid analogues induces sorting to the vacuole of the newly synthesized Gap1 en route to the plasma membrane (18, 19). However, newly synthesized Tat2 is regulated inversely: the permease en route to the plasma membrane is diverted to the vacuole when cells face nutrient deprivation or are treated with rapamycin (20), whereas nitrogen availability re-establishes the traffic of Tat2 to the plasma membrane. The exact mechanism determining the different fates for both permeases under nitrogen limitation remains unclear. Vacuolar sorting is inversely regulated by the nitrogen permease reactivator 1 kinase (Npr1).5 Activation of Npr1, under control of the TOR kinase pathway (21, 22), is necessary for the traffic of Gap1 to the plasma membrane, which, in turn, diverts Tat2 to the vacuole (22, 23).

The role of the preferred nitrogen sources in regulating Ynt1 levels has been thoroughly documented by our group (10, 11, 13). However, the mechanism involved in preventing Ynt1 degradation when cells are exposed to nitrogen limitation is so far unknown. In this work we study the role of Ynt1 phosphorylation in maintaining Ynt1 levels under nitrogen deprivation. A brief incubation in nitrogen-free medium triggers the phosphorylation of Ynt1 in an Npr1 kinase-dependent way. We show that phosphorylation of Ynt1 is required to prevent the sorting to the vacuole of Ynt1 present in the biosynthetic pathway and thus ensures the delivery of the transporter to the plasma membrane. When phosphorylation of Ynt1 is impaired, the vacuolar sorting of the transporter requires ubiquitinylation of the same residues involved in the ubiquitin-dependent endocytosis of Ynt1.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Microorganisms and Growth Conditions—The H. polymorpha strains used in this work are listed in Table 1. All strains are derivatives of NCYC495 leu2 ura3 strain. Yeast cells were grown with shaking at 37 °C in YPD medium (1% (w/v) yeast extract, 2% (w/v) peptone, 2% (w/v) glucose) or synthetic medium containing 0.17% (w/v) yeast nitrogen base without amino acids and ammonium sulfate (Difco), 2% (w/v) glucose, and the nitrogen source indicated in each case. Nitrogen deprivation medium (nitrogen-free medium) contains 0.17% (w/v) yeast nitrogen base without amino acids and ammonium sulfate (Difco) and 2% (w/v) glucose. To obtain yeast cells with high levels of Ynt1, cells were grown in synthetic medium with 5 mm ammonium chloride, harvested by centrifugation, thoroughly washed with de-ionized water, and subjected to 1 h of nitrogen starvation in synthetic medium. Then cells were incubated at 10 mg/ml (wet weight) in synthetic media plus 10 mm sodium nitrate. Whenever necessary, media were supplemented with 30 μg/ml l-leucine, 20 μg/ml uracil, or 100 μg/ml Zeocin.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this work

| Strain | Main features | Origin |

|---|---|---|

| WT | NCYC495 leu2::p18B1(LEU2) ura3::pBSURA3(URA3) | Laboratory collection |

| FN0125 | YNT1-eGFP | Laboratory collection |

| ynr1 | Δynr1::URA3 | Laboratory collection |

| FN0002 | ynt1Δ232-286 | Laboratory collection |

| FN1203 | Δynr1::URA3 leu2::pGP1(PYNR1-lacZ HpLEU2) | Laboratory collection |

| FN3203 | Δynt1::Δura3 Δynr1::URA3 leu2:: pGP1 (PYNR1-lacZ HpLEU2) | Laboratory collection |

| FN0008 | ynt1S244A S246A | This work |

| FN0016 | ynt1S244E S246E | This work |

| FN0011 | ynt1S244A | This work |

| FN0012 | ynt1S246A | This work |

| FN0009 | ynt1S252A | This work |

| FN0010 | ynt1T258A | This work |

| FN0015 | ynt1K243R S244A S246A S252A K253R K270R | This work |

| FN1425 | ynt1S244A S246A-eGFP | This work |

| FN1625 | ynt1S244E S246E-eGFP | This work |

| FN1525 | ynt1K243R S244A S246A S252A K253R K270R-eGFP | This work |

| YM1200 | Δpep4::ble ynt1S244A S246A | This work |

| YM0100 | Δnpr1::LEU2 | This work |

| YM0116 | Δnpr1::URA3 Δpep4::ble | This work |

| YM0101 | Δnpr1::URA3 YNT1-eGFP | This work |

| YM0300 | nNPR1 | This work |

| YM0302 | ynt1S244A S246AnNPR1 | This work |

| YM0303 | ynt1S244AnNPR1 | This work |

| YM0304 | ynt1S246AnNPR1 | This work |

| YM0305 | ynt1S526AnNPR1 | This work |

| YM0400 | Δend4::URA3 | This work |

| YM0401 | Δend4::URA3 YNT1-eGFP | This work |

| YM0402 | Δend4::URA3 ynt1S244A S246A | This work |

| YM0403 | Δend4::URA3 ynt1S244A S246A-eGFP | This work |

| YM1500 | Δynr1::URA3 leu2::pGP1(PYNR1-lacZ HpLEU2) ynt1S244A S246A | This work |

| FN0064 | Δpep12::URA3 | This work |

| FN6414 | Δpep12::URA3 ynt1S244A S246A-eGFP | This work |

Mutagenesis and Construction of Mutant Strains—YNT1 gene single point mutations were created using the QuikChange kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). A pop-in/pop-out strategy, which assures single-copy integration, was used to integrate the mutated version of YNT1 in the genome (13).

nNPR1 Strain—Strains bearing several copies of the NPR1 gene (nNPR1) were obtained by transforming the wild-type strain with the plasmid pNPR1LEU2 linearized at the LEU2 gene with BstEII. Strains bearing multiple integrations of pNPR1LEU2 were determined by semi-quantitative PCR and increased capacity to phosphorylate Ynt1.

Disruption of H. polymorpha NPR1, END4, and PEP12 Genes—The H. polymorpha DL1 genome data base was screened for putative proteins with high similarity to S. cerevisiae Npr1, End4, and Pep12 proteins. The open reading frames encoding proteins with the highest similarity scores were disrupted with cassettes containing part of the target sequence flanking the H. polymorpha marker genes URA3 or LEU2. The genomic sequence used for the construction of the disruption cassettes and for later complementation of mutants was obtained by PCR using Pfu and cloned into the appropriate vectors. Further information on vectors and cassettes construction is available upon request to the authors. Recipient strains were electrotransformed with cassettes, and transformants were selected on the basis of growth in the absence of uracil or leucine. Transformants bearing the disrupted target gene were identified by PCR.

Yeast Cell Extract Preparation, SDS-PAGE, and Immunoblotting—Extracts for immunoblot were prepared from 50 mg of cells as described elsewhere (13). Briefly, cells were homogenized in a FastPrep homogenizer device (Thermosavant LifeSciences, Hampshire, UK) for 20 s at 6.0 m/s with 300 μl of Lysis Buffer I (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 15 mm EDTA, 15 mm EGTA, 10 mm NaN3, 10 mm Na2P2O7, 10 mm NaF plus Complete Mini protease inhibitor mixture, Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, and 2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and 0.5-mm diameter glass beads. The supernatant resulting from the low centrifugation of extracts (820 × g for 1 min) was centrifuged at 20,500 × g for 45 min at 4 °C. Pellets were resuspended in 70 μl of 0.25 mg/ml Triton X-100 and then mixed with 4× Sample Buffer (4×: 12% (w/v) SDS, 6% (v/v) 2-mercaptoethanol, 30% (w/v) glycerol, 0.05% (w/v) Serva blue G, 150 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7). Samples were heated at 40 °C for 30 min and then subjected to SDS-PAGE. For Ynt1-Ub conjugates visualization, cells were processed as described above, except they were harvested with 10 mm NaN3, and Lysis Buffer I was supplemented with freshly prepared 50 mm N-ethylmaleimide (Sigma-Aldrich) to prevent deubiquitinylation. SDS-PAGE and Ynt1 immunodetection were performed as in Ref. 10. Ynt1 immunodetection was carried out with 1:1500 rabbit anti-Ynt1 antiserum; Pma1, used as load control and plasma membrane marker, was immunodetected with rabbit anti-ScPma1 antiserum (gift of Dr. Ramon Serrano, Valencia, Spain). Cell extracts and immunoblots were carried out from a minimum of three independent experiments. Films were documented using a densitometer (GS-800, Bio-Rad).

λ-Protein Phosphatase Treatment—Protein extracts were obtained as described above using Lysis Buffer II (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, Complete Mini protease inhibitor mixture, and 2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). Pellets containing cellular membranes were resuspended in 70 μl of 0.25 mg/ml Triton X-100, 1× λ-protein phosphatase buffer (0.1 mm EDTA, 5 mm dithiothreitol, 0.01% (w/v) Brij35, 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5), 2 mm MnCl2.20 μg of protein was incubated with 150 units of λ-protein phosphatase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) for 25 min at 30 °C. The reaction was stopped by adding 4× Sample Buffer, and samples were heated at 40 °C for an additional 30 min. According to the manufacturer, addition of 50 mm EDTA to the dephosphorylation reaction produces a 95% inhibition of the activity of λ-protein phosphatase.

Fluorescence Microscopy—To localize Ynt1 in the cell, the chromosomal copy of the YNT1 gene was substituted by a fusion of wild-type or mutant YNT1 to GFP (13). Images were obtained under an epifluorescence Nikon Eclipse 50i microscope equipped with a 1200F camera (Nikon). Vacuole membranes were stained with 10 μm FM4-64 (Molecular Probes Inc., Eugene, OR) for 15 min at 37 °C with shaking, at least 1.5 h before observation. Processing of images only consisted of cropping areas of interest and adjusting contrast, intensity, and brightness to adequate levels for reproduction.

Miscellaneous Methods—Electrotransformation of yeast cells

was performed as described previously

(24). Nitrate uptake activity

was measured according to a previous study

(10) as extracellular nitrate

depletion. Purified H. polymorpha nitrate reductase enzyme (NECi,

Lake Linden, MI) was used to determine nitrate concentration. Nitrate uptake

is expressed as nanomoles of  transported·min-1·(mg of cell)-1. Mean

values ± S.D. from at least three independent experiments are shown.

β-Galactosidase activity was determined as in Ref.

25.

transported·min-1·(mg of cell)-1. Mean

values ± S.D. from at least three independent experiments are shown.

β-Galactosidase activity was determined as in Ref.

25.

RESULTS

Nitrogen Limitation Leads to Phosphorylation of Ynt1—Ynt1 transports nitrate and nitrite with high affinity; this system is essential when nitrate concentration is in the micromolar range or lower (10, 26). The stability of Ynt1 levels was enhanced in cells starved of nitrogen when compared with cells incubated with glutamine, a preferred nitrogen source (Fig. 1A). When cells were deprived of nitrogen source, Ynt1 protein was degraded slowly and remains associated with the plasma membrane (Fig. 1B).

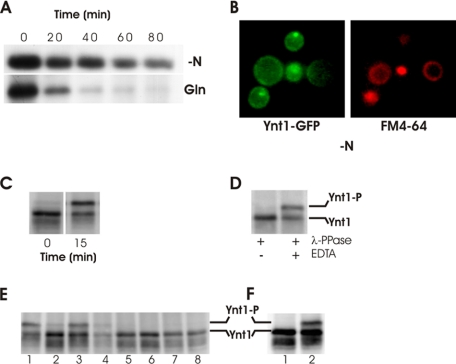

FIGURE 1.

Nitrogen limitation triggers phosphorylation of Ynt1. A, Ynt1 protein levels are much more stable under nitrogen-limited conditions than in nitrogen sufficiency. Immunoblots of Ynt1 from cells incubated for the indicated times in synthetic medium without nitrogen source (upper panel) or with glutamine 5 mm (lower panel). Cells were incubated previously with nitrate for 1.5 h. B, localization of Ynt1-GFP (left panel) and vacuolar membrane (right panel) after 270 min of nitrogen deprivation. C, immunoblot of Ynt1 from cells incubated with 1 mm nitrate (time 0) and deprived of nitrogen for 15 min. D, Ynt1 low mobility shift band is due to Ynt1 phosphorylation. Protein extracts from cells deprived of nitrogen after incubation in nitrate were treated with λ-protein phosphatase. 50 mm EDTA was added to inhibit λ-protein phosphatase. E, immunoblot of Ynt1 from cells previously incubated with nitrate 1 mm for 2 h and then deprived of nitrogen for 30 min (lane 1) or incubated 30 min in synthetic medium with nitrate 1 mm (lane 2), Pro 1 mm (lane 3), nitrite 1 mm (lane 4), ammonium 1 mm (lane 5), Glu 1 mm (lane 6), Gln 1 mm (lane 7), and Gln 1 mm plus nitrate 1 mm (lane 8). Load per lane was adjusted to obtain similar signal intensities. F, Ynt1 in wild-type (1) and Δynr1 cells (2) after incubation in 5 mm nitrate for 2 h. Because Ynt1 levels are affected by nitrogen sources, in E enriched plasma membrane protein-load per lane was adjusted to obtain similar Ynt1 signal intensity.

Exploring the response of Ynt1 protein to the nitrogen source, nitrogen limitation induced the appearance of a lower mobility band in the Ynt1 immunoblot, not present in cells incubated in nitrate (Fig. 1C). This band was absent in the Δynt1 mutant strain and was still detected in immunoblots of Ynt1 lacking the principal ubiquitinylation sites (results not shown), suggesting that this band was not caused by a ubiquitinylated form of the transporter. Treatment of protein extracts with λ-protein phosphatase eliminated the upper band and increased the intensity of the lower band (Fig. 1D), suggesting that the upper band represented a phosphorylated state of Ynt1. Interestingly, phosphorylation of Ynt1 was only observed after incubation of cells in media where no nitrogen was added or with a poor nitrogen source (e.g. proline). However, Ynt1 remained unphosphorylated if cells were incubated with preferred nitrogen sources such as ammonium, glutamate, and glutamine (Fig. 1E). Incubation with nitrate did not significantly increase phosphorylation of Ynt1, most likely because the nitrate assimilation pathway rapidly produces good nitrogen sources such as ammonium and glutamine. Phosphorylation of Ynt1 in nitrate-containing medium was enhanced in a mutant strain lacking nitrate reductase and therefore, unable to assimilate nitrate, supporting the conclusion that nitrogen deprivation is the principal stimulus for phosphorylation of Ynt1, although nitrate did not abolish Ynt1 phosphorylation (Fig. 1F).

To further analyze the role of the phosphorylation in Ynt1 regulation we proceeded to identify the phosphorylation sites. Phosphorylation clearly depended on the central intracellular loop, because a mutant transporter lacking a major part of this sequence failed to be phosphorylated in a nitrogen-free medium (Fig. 2A).

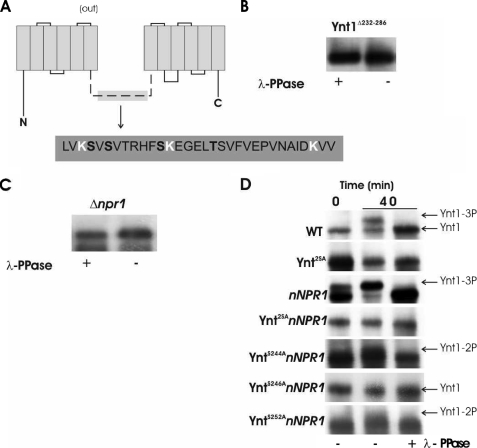

FIGURE 2.

Phosphorylation of Ynt1 occurs in serine residues of the central intracellular loop and depends on H. polymorpha Npr1 kinase. A, topological model of Ynt1, the sequence removed in Ynt1Δ232-286 is depicted. Residues in white are ubiquitinylation sites previously characterized. B, Ynt1Δ232-286 is not phosphorylated. Ynt1 immunoblot of a mutant lacking a major part of the central hydrophilic domain (from residue 232 to 286) after 40 min of nitrogen deprivation conditions. Enriched plasma membrane protein was treated and untreated with λ protein phosphatase (λ-PPase). C, phosphorylation state of Ynt1 in Δnpr1 strain deprived of nitrogen. Membrane protein from Δnpr1 mutant was treated and untreated with λ-PPase. Protein load was adjusted to obtain similar signal intensity. D, Ser-246 plays a key role in Ynt1 phosphorylation. Ser-244, Ser-246, and Ser-248 (in bold in the sequence) were mutated to Ala, and phosphorylation of Ynt1 was tested in strains overexpressing NPR1 by SDS-PAGE mobility shift. Ynt1 was detected by immunoblotting.

S. cerevisiae Npr1 is a Ser/Thr kinase required for stabilization of Gap1 at the plasma membrane and probably for its phosphorylation. Npr1 also controls the trafficking of the intracellular pool of the permease (23). H. polymorpha Npr1 shares a high identity with S. cerevisiae Npr1, and the null mutant reproduced the phenotype observed in S. cerevisiae regarding reduced growth in ammonium medium (results not shown). Similarly, we observed that Ynt1 phosphorylation was diminished in a H. polymorpha Δnpr1 mutant (Fig. 2B). As in Ynt1Δ232-286, Δnpr1 mutation prevented Ynt1 phosphorylation in nitrogen-deprived cells. Therefore, Npr1 seems to be essential for accumulation of phosphorylated Ynt1 during nitrogen deprivation.

There are six phosphoacceptor residues within the sequence removed from the transporter Ynt1Δ232-286 that lie in close proximity to the ubiquitinylation sites identified previously (depicted in white in Fig. 2). We employed site-directed mutagenesis on the four residues with the highest scores after the prediction of phosphorylation sites obtained from NetPhos-Yeast (www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/) (27). Ynt1 phosphorylation was determined by SDS-PAGE mobility shift from extracts of strains bearing different Ynt1 mutated versions and overproducing Npr1, the protein kinase involved in Ynt1 phosphorylation. We observed that overexpression of the NPR1 gene copy number considerably augmented Ynt1 phosphorylation; it could be observed that the dephosphorylated band (highest mobility) almost disappeared when cells were transferred for 20 min to nitrogen-free medium (Fig. 2D). The overexpression of Npr1 also presents an additional advantage, in that Ynt1 is much more stable (Y. Martin, results not shown), and this facilitates observation of its electrophoretic mobility. The phosphorylation of the wild-type form of Ynt1, as well as in a set of mutants bearing the single mutations S244A, S246A, or S252A, was determined by analyzing Ynt1 mobility from enriched plasma membrane non-treated and treated with λ-protein phosphatase, in SDS-PAGE. It was observed that when Ser-246 was mutated to Ala the slow mobility Ynt1 band totally disappeared. However, when Ynt1 S244A or Ynt1 S252A was analyzed, an intermediate mobility band between those corresponding to the fully phosphorylated (WT) and non-phosphorylated Ynt1 was observed. The slow mobility band observed in the WT form of Ynt1 would correspond to the phosphorylation of the three serine residues (Ser-244, Ser-246, and Ser-252), the participation of Ser-246 being the highest. In summary, three Ynt1 SDS-PAGE discrete bands with slow, intermediate, and high mobility were detected; these correspond to the full phosphorylation (Ser-244, Ser-246, and Ser-252), phosphorylation of Ser-246 plus serines 248 or 252, and the absence of phosphorylation, respectively. No mobility changes at all were observed when Ser-246 was mutated to Ala; however, we cannot rule out Ynt1 S246A phosphorylation at a very low level, with inappreciable mobility changes, under nitrogen deprivation. Our results allow us to conclude that, under nitrogen deprivation conditions, the phosphorylation of Ser-246 plays a key role in the regulation of Ynt1 turnover.

Phosphorylation Is Crucial for Stability of Ynt1 Levels under Nitrogen Deprivation—To investigate the role of the phosphorylation in Ynt1, we further analyzed the mutant strains that exhibited reduced phosphorylation. S → A mutants: S244A, S246A, S252A, and 2SA (S244A+S246A) transported nitrate at similar rates to wild-type strain when cells were incubated in medium containing nitrate (results not shown) but differences appeared when the nitrogen source was removed (Fig. 3A). Nitrate uptake activity remained unmodified in the wild-type strain after 45 min of incubation in a nitrogen-free medium. In S244A and S252A mutant strains, nitrate uptake activity also remained quite high after the period of nitrogen deprivation, respectively, at 71 and 86% of the value determined in the nitrate medium. However, nitrate uptake activity of S246A mutant dropped abruptly after nitrogen deprivation to 30% of the initial value. A higher drop occurred in the 2SA double mutant, which was in agreement with the levels of Ynt1 protein (Fig. 3B). The amount of mutant Ynt12SA protein decreased significantly after deprivation of nitrogen, whereas wild-type Ynt1 protein did not. In conclusion, there was a strong correlation between Ynt1 phosphorylation and stability in response to nitrogen-free conditions, thus Ynt1 stability increases with its phosphorylation.

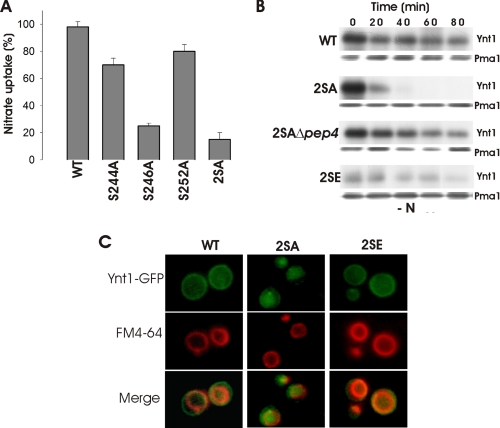

FIGURE 3.

Under nitrogen deprivation, non-phosphorylatable mutant transporter is degraded in the vacuole. A, nitrate uptake activity in wild-type and S → A mutants after 45 min of nitrogen deprivation. Cells incubated in 10 mm nitrate for 1.5 h were transferred to medium without nitrogen. Nitrate uptake is expressed as a percentage with respect to nitrate uptake activity before nitrogen limitation. B, Ynt1 levels in different strains subjected to nitrogen deprivation. After nitrate incubation, cells were deprived of nitrogen for 80 min. Pma1 was used as loading control. C, fluorescence of cells bearing wild-type and mutant 2SA and 2SE Ynt1-GFP fusions after 90-min nitrogen deprivation (upper panels). Vacuolar membrane was stained with FM4-64 (middle panels).

Degradation of Ynt12SA was partially prevented in a Δpep4 mutant background, which exhibits reduced vacuolar proteolytic activity (28, 29).6 This result suggested that the mutant protein was being degraded in the vacuole during nitrogen deprivation; accordingly, Ynt12SA-GFP was mostly associated with the vacuole after 90 min of nitrogen deprivation (Fig. 3C), whereas wild-type Ynt1 protein was localized principally at the cell surface.

S244E and S246E mutations, used to mimic a phosphorylated Ynt1, rendered a transporter with different behavior to Ynt12SA but similar to the wild type. These mutations brought about partial reversion to wild-type behavior regarding Ynt1 levels stability and localization during nitrogen deprivation (Fig. 3, B and C). This supported the hypothesis that the vacuolar degradation of Ynt12SA during nitrogen deprivation is a consequence of the lack of Ynt1 phosphorylation, and therefore, phosphorylation is a necessary modification to maintain the high amount of Ynt1 during nitrogen deprivation. The fact that in Ynt12SE mutant some degradation and vacuolar localization was still preserved could reflect that Ser → Glu mutation did not fully perform the role of phosphorylation.

We also observed that the Δnpr1 mutation, which impairs phosphorylation of Ynt1 under nitrogen deprivation, brought about a similar phenotype to that produced by 2SA mutation (Fig. 4). The decrease in nitrate uptake when cells were deprived of nitrogen (results not shown) was correlated with the loss of Ynt1 protein (Fig. 4A). Degradation of the transporter was reduced when Δnpr1 mutation was combined with Δpep4 mutation (Fig. 4A), suggesting that the lack of Npr1 triggered the degradation of Ynt1 in the vacuole during nitrogen deprivation. As expected, Ynt1-GFP in a Δnpr1 mutant was visualized exclusively in the vacuole after 40-min deprivation (Fig. 4B). Therefore, the Δnpr1 mutation reproduced the same effects on Ynt1 protein as the mutation of the phosphorylation sites.

FIGURE 4.

Δnpr1 present low Ynt1 levels in nitrogen deprivation. A, immunoblot of Ynt1 in Δnpr1 and Δnpr1 Δpep4 strains before and after 40 min of nitrogen deprivation. Cells had been incubated for 1.5 h in medium containing nitrate 1.5 mm. B, Ynt1-GFP localization in Δnpr1 cells after 40 min of nitrogen deprivation. Vacuolar membranes are stained in red with FM4-64.

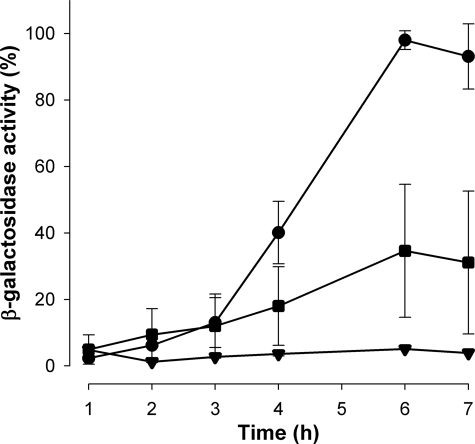

Abolition of Ynt1 Phosphorylation Reduces Nitrate-induced Gene Expression—Considering the effects that abolition of phosphorylation has on Ynt1 protein levels, we were interested in knowing if the 2SA mutation in the nitrate transporter could affect the cell response to nitrate. To test this, we analyzed the growth on nitrate in the mutant strain in which Ynt1 cannot be phosphorylated. The growth of this mutant was studied in liquid and on solid media at different nitrate concentrations. However, no differences with the wild-type strain were detected in any conditions, even when nitrate concentration was as low as 0.5 mm (results not shown). These findings led us to think that the Ynt1 regulatory mechanism could be involved in the response to nitrate under very limited nitrogen conditions. We have previously shown in H. polymorpha that nitrate must be transported into the cell to induce the nitrate assimilatory genes, which indicates that nitrate transport systems play an essential role in nitrate assimilation regulation (9). To monitor the induction of these genes when Ynt1 phosphorylation is altered, nitrate reductase gene (YNR1) promoter fused to lacZ was used as reporter. YNR1 is strongly induced by nitrate and repressed by good nitrogen sources. To detect the effect of nitrate traces on YNR1-lacZ induction, a strain lacking nitrate reductase (Δynr1) was used, because in this strain nitrate is transported into the cell but not metabolized. Therefore, the Δynr1 strain bearing the YNR1-lacZ fusion was used to evaluate the contribution of different versions of Ynt1 (wild-type, Ynt12SA, or no Ynt1 transporter) to nitrate-induced gene expression. Cells were incubated in a medium without nitrogen source in the presence of nitrate traces (0.01 μm). Under these conditions, nitrate can only be transported into the cell by Ynt1, the sole high affinity nitrate transporter, and accumulates in the cell. As depicted in Fig. 5, YNR1-lacZ induction depends exclusively on Ynt1, because when Ynt1 is eliminated lacZ is not induced. So, we compared the induction levels in cells bearing wild-type Ynt1 and mutant Ynt12SA. In cells expressing wild-type Ynt1, lacZ induction reached its maximum after 6 h, but in cells expressing Ynt12SA, lacZ induction reached only 40% of that of the wild-type Ynt1 strain. This result indicates that phosphorylation of Ynt1 is necessary for a more efficient induction of nitrate assimilatory genes with only nitrate traces. Thus, phosphorylation of Ynt1 could be considered part of the nitrate-sensing mechanism, at least in the way that phosphorylation permits the amount of nitrate transporter to increase at the plasma membrane, and as a result, the capacity of the cell to transport nitrate, the inducer of the genes involved in its assimilation, also increases.

FIGURE 5.

Abolition of Ynt1 phosphorylation reduces the expression levels of genes induced by nitrate. Strains Δynr1 YNR1-lacZ, containing different versions of Ynt1, were incubated in nitrogen-free medium: wild-type transporter (•), Ynt12SA (▪), or no transporter (▾). Induction of lacZ was determined as β-galactosidase activity.

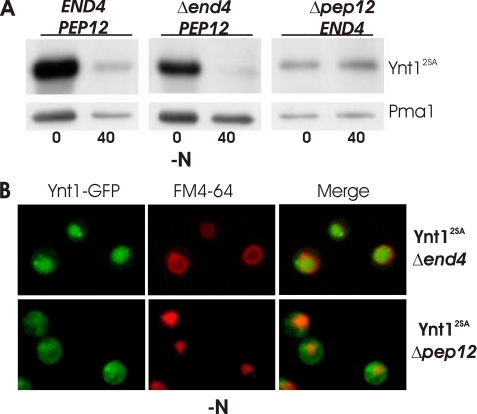

Under Nitrogen Limitation, Non-phosphorylatable Ynt1 Is Delivered to the Vacuole Without Passing via the Plasma Membrane—The vacuolar degradation of the non-phosphorylatable mutant Ynt1 during nitrogen deprivation could have two explanations, which entail different roles for phosphorylation in Ynt1 regulation: (i) Phosphorylation could prevent endocytosis of Ynt1 during nitrogen deprivation and so, impeding phosphorylation would result in higher endocytosis of Ynt1 and vacuolar degradation. Alternatively, (ii) phosphorylation could control the fate of the newly synthesized transporter en route to the plasma membrane and so, non-phosphorylated Ynt1 would be delivered from the secretion route to the vacuole without reaching the plasma membrane. To test this hypothesis, we studied the degradation of Ynt12SA in two mutant strains with altered intracellular traffic, end4 and pep12. END4 deletion blocks the earlier stages of endocytosis, impairing internalization but not later delivery to the vacuole or sorting of vacuolar hydrolases from the Golgi apparatus to the vacuole (30). On the other hand, pep12 mutation impairs the docking of transport vesicles in the late endosome/pre-vacuolar compartment and consequently missorts soluble vacuolar hydrolases en route to the vacuole and blocks diversion of plasma membrane proteins from post-Golgi to the vacuole (31-33). As the prevacuolar compartment also receives cargo vesicles from early endosomes and the vacuole, Δpep12 mutation also blocks late endocytosis and retrograde transport. H. polymorpha Δpep12 and Δend4 mutants produced Ynt1 when cells were incubated in a nitrate-containing medium, although the amount of Ynt1 protein in the mutant strains, especially in the Δpep12 mutant, was lower than in the wild type. Abnormal intracellular trafficking was confirmed when glutamine was added to the culture, because glutamine-triggered endocytosis of Ynt1 was not detected in either mutant strain (results not shown).

Degradation and cellular redistribution of Ynt12SA in nitrogen-deprived medium was studied in Δend4 and Δpep12 mutants by immunoblot and GFP fusion (Fig. 6, A and B). Δend4 mutation did not prevent degradation of Ynt12SA after 40-min deprivation, and neither did vacuolar accumulation of Ynt12SA-GFP, which indicated that endocytosis is not required for the delivery of Ynt12SA to the vacuole. On the other hand, Δpep12 mutation blocked Ynt12SA degradation in response to deprivation and prevented vacuolar accumulation of the transporter, although the cellular distribution of Ynt12SA-GFP in Δpep12 was different to that observed in the PEP12 strain (wild type) (Fig. 6B). Fluorescence was mainly intracellular in this mutant, distributed in a dotted pattern surrounding the vacuole. The results obtained from Δend4 and Δpep12 mutant strains indicate that the vacuolar delivery and degradation of Ynt12SA was independent of endocytosis and therefore was a result of direct sorting of the unphosphorylated transporter from the secretory pathway to the vacuole, via the pre-vacuolar compartment. Therefore, phosphorylation is required to target Ynt1 to the plasma membrane when cells face nitrogen limitation. Otherwise, Ynt1 is directly sorted to the vacuole for degradation.

FIGURE 6.

Vacuolar degradation of Ynt12SA is independent of endocytosis. A, Ynt12SA levels in Δpep12 and Δend4 strains before and after 40 min of nitrogen deprivation. B, Ynt12SA-GFP localization in Δpep12 and Δend4 strains after 40 min of nitrogen deprivation.

Under Nitrogen Limitation, Ubiquitinylation Is Required to Deliver Ynt1 from the Secretion Route to Vacuole—Ubiquitinylation is required for the endocytosis of Ynt1 in response to the availability of a rich nitrogen source. We addressed the question if ubiquitinylation, in addition to dephosphorylation, was also involved in the sorting of Ynt1 from the Golgi apparatus to the vacuole under nitrogen deprivation. In fact, in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, vacuolar sorting directly from the Golgi apparatus of newly synthesized yeast permeases Gap1, Fur4, and Tat2 to the vacuole requires ubiquitinylation (20, 32, 34). Efficient endocytosis of Ynt1 requires the ubiquitinylation of lysine residues of the central intracellular loop, principally Lys-253 and Lys-270. Mutation of these residues, together with the nearby lysine residue Lys-243, produces a poor endocytosis of Ynt1 (13). To study if ubiquitinylation of these same residues was also involved in the sorting of Ynt1 from the Golgi apparatus to the vacuole of the non-phosphorylated transporter, we compared the degradation of mutant Ynt12SA (S244A and S246A) containing or lacking these lysine residues (S244K243R, K253R, and K270R) (Fig. 7). As observed in Fig. 7A, degradation of the non-phosphorylated Ynt1 was significantly delayed when the ubiquitinylation sites were eliminated. Additionally, we observed plasma-membrane accumulation of Ynt12SA 3KR-GFP after 40 min of nitrogen deprivation (Fig. 7B, upper panel), resembling the wild-type cellular distribution shown above (Fig. 3C). The poor degradation observed in a Ynt12SA 3KR mutant transporter cannot be explained by a higher stabilization of the mutant permease, which has reached the cell surface, because such behavior was not observed in Ynt12SA Δend4 strain (Figs. 6A, 6B, and 7B, lower panel). Therefore, we conclude that ubiquitinylation, at the same sites involved in Ynt1 endocytosis, is required for delivering Ynt1 from the secretion route to the vacuole in response to nitrogen limitation. It is noteworthy that the degradation of Ynt12SA 3KR was diminished but not completely abolished, which might suggest that ubiquitinylation of lysine residues other than Lys-243, Lys-253, and Lys-270 could be involved in Ynt1 vacuolar sorting.

FIGURE 7.

Direct sorting of non-phosphorylatable transporter from the secretion pathway to the vacuole is dependent on ubiquitinylation. A, immunoblot of Ynt12SA (244A and S246A) and Ynt12SA 3KR (244A, S246A+K243R, K253R, and K270R) before and after 40 and 80 min of nitrogen deprivation. Pma1 was used as loading control. B, cells bearing Ynt12SA 3KR-GFP and Ynt12SA-GFP Δend4 were deprived of nitrogen for 40 min. The vacuolar membrane is stained in red with FM4-64.

DISCUSSION

Organisms able to assimilate nitrate face different environmental situations ranging from easily assimilable nitrogen sources like glutamine or ammonium to those where only nitrogen traces are available. Under both conditions, cells respond in the long term by abolishing the expression of the genes involved in nitrate assimilation, whereas the short-term response involves post-translational regulation of the enzymatic machinery of the pathway.

Early studies in our laboratory showed that the levels of Ynt1 are very stable when cells were transferred to a very limited nitrogen medium, even though nitrate was not added. This finding contrasts with what occurs when cells are transferred to glutamine, where Ynt1 is ubiquitinylated, endocytosed, and degraded in the vacuole (13). In this framework we have focused our study on uncovering the role of Ynt1 phosphorylation in conferring high stability to the levels of Ynt1 under nitrogen deprivation conditions. It is remarkable that Ynt1 is phosphorylated when cells are deprived of nitrogen and that the presence of most nitrogen sources renders Ynt1 dephosphorylation (Fig. 1). The analysis by single mutations of the potential phosphorylation sites showed that mutations S244A and S252A reduce Ynt1 phosphorylation but S246A reproduced most of the phenotype of the triple mutant S244A,S246A,S252A (data not shown) or central hydrophilic deletion (Fig. 2). Thus, Ser-246 could constitute the preferred phosphorylation site among other nearby residues (Ser-246 is framed in a putative protein kinase C site) or, alternatively, the phosphorylation of Ser-246 could be necessary for the further phosphorylation of Ser-244 and Ser-252. These serine residues are inside a PEST-like sequence, which also contains the principal ubiquitinylation sites of Ynt1. Interestingly, a similar situation is also seen in Fur4 and Ste2, where phosphorylation sites lay in proximity to ubiquitinylation sites (35, 36). The different role of phosphorylation in post-translational regulation of the two best known nitrate transporters, Ynt1 in yeast and CHL1 (AtNRT1;1) in plants, is worth mentioning. Phosphorylation of CHL1 modulates the affinity of the transporter for nitrate (12), while we have shown in this work that the principal role of phosphorylation in Ynt1 is in the control of its cellular distribution. No difference in affinity for nitrate was detected between wild type and mutants at the phosphorylation sites studied (results not shown).

Our results suggest a role of Npr1 kinase in the phosphorylation of Ynt1. First, in the mutant strain Δnpr1, nitrogen-deprivation triggered phosphorylation of Ynt1 was not detected (Fig. 2C), second, overproduction of Npr1 produced a concomitant increase in Ynt1 phosphorylation, and third, NPR1 deletion reduced the levels of Ynt1 phosphorylation under nitrogen deprivation, as did the elimination of the phosphorylation sites (Fig. 2D). This indicates that the effects of the mutation Δnpr1 are a direct consequence of the absence of Ynt1 phosphorylation. However, there was no evidence that Npr1 kinase directly phosphorylates Ynt1 or is integrated into a cascade that governs the kinase(s) responsible for the phosphorylation of the transporter. This last possibility seems to be the case for S. cerevisiae Gap1 permease, because even though Npr1 site-point mutation reduces the phosphorylation levels of Gap1, it does not completely abolish the phosphorylation of the permease, and yet, in the Δ npr1 npi1 double mutant, phosphorylation of Gap1 is as in the wild type (23). The role of Npr1 in phosphorylation and cellular localization of Ynt1 raises the question of whether TOR kinases are involved in its post-translational regulation. However, the TOR kinases-inhibitor rapamycin, which mimics the nitrogen deprivation conditions, did not alter either the phosphorylation or Ynt1 stability (results not shown), although the same dose of rapamycin allows the expression of the nitrate reductase gene under repression conditions, such as in glutamine (9). The absence of any effect of rapamycin on Ynt1 regulation is somewhat surprising, considering that in S. cerevisiae Npr1 regulation is under the control of TOR (22) and its role in the phosphorylation of Ynt1, as shown in this work. Likewise, the effect of rapamycin on S. cerevisiae Gap1 is controversial. Early experiments showed that Gap1 is affected by rapamycin, which is consistent with the effect of this macrolide on Npr1. However, Chen and Kaiser (18) found no effect of rapamycin on Gap1 trafficking and even that sublethal concentrations of rapamycin reduced the levels of Gap1 due to an increasing intracellular amino acids pool (37). We cannot exclude differences between S. cerevisiae and H. polymorpha, regarding the involvement of the TOR kinases pathway in regulating nitrogen permeases, so further studies are necessary to clarify this point.

Consistent with our hypothesis on the role of phosphorylation in Ynt1 stability under nitrogen deprivation conditions, S → A mutation revealed a rapid degradation of Ynt1 in nitrogen deprivation medium (Fig. 3). In this respect we have also shown that the mutation of the phosphoacceptor serine residues to glutamic acid (S → E) partially re-establishes Ynt1 stability under nitrogen limitation conditions. However, it is important to remark that the S → E mutation did not affect the response of Ynt1 to glutamine (results not shown), that is, Ynt1SE was degraded in response to glutamine as in wild-type and neither was it more stable than wild-type Ynt1 under nitrogen restriction conditions. This behavior makes us consider that phosphorylation does not prevent ubiquitinylation and endocytosis of Ynt1 once the transporter has reached the plasma membrane. Additionally, it is unclear if Ynt1 remains phosphorylated once it is within the plasma membrane. The coexistence of phosphorylated and unphosphorylated forms of Ynt1 in immunoblots could suggest that, once Ynt1 reaches the plasma membrane, it gets dephosphorylated. It is also important to remark that no Ynt1 phosphorylation was observed in abundant nitrate (5 mm), and even the S → A mutants accumulated in the plasma membrane as did wild-type Ynt1 (Fig. 3B, lanes 0). Although it cannot be ruled out that Ynt1S→A could reach the plasma membrane through phosphorylation of other residues at lower levels, it is also possible that the high expression of YNT1 gene in nitrate could compensate for diversion of Ynt1S→A from the secretory pathway to the vacuole. Alternatively, it is also plausible that nitrate abolishes this alternative route of Ynt1 to the vacuole. We also show that the diversion of Ynt1 to the vacuole requires ubiquitinylation. The combination of S → A mutations with those affecting the ubiquitinylation sites Lys-243, Lys-253, and Lys-270, to render the mutant Ynt13KR 2SA, resulted in a hindered vacuolar degradation in response to limited nitrogen (Fig. 7). Interestingly, these same residues have previously been shown to be necessary for endocytosis of Ynt1. It could thus be speculated that phosphorylation prevents the ubiquitinylation of Ynt1 at the early stages of the secretory pathway.

The use of pep4, end4, and pep12 mutants along with Ynt1-GFP localization clearly revealed that the lack of phosphorylation led Ynt1 to vacuolar degradation, Ynt1 being delivered directly from the biosynthetic pathway to the vacuole, without passing through the plasma membrane. Delivery to the vacuole from the secretion pathways has been reported for several S. cerevisiae permeases. The quality of the nitrogen source triggers the sorting of Gap1 and Tat2 to the vacuole without passing via the plasma membrane. Thus, the addition of ammonium or glutamate results in direct sorting of Gap1p to the vacuole. Ubiquitinylation of lysines 6 and 13, the Rsp5 ubiquitin ligase, and Bul1/2 proteins are required for this alternative route for intracellular traffic (34, 38). Tat2 is sorted to the vacuole when the cells are shifted to nitrogen deprivation, in the presence of rapamycin or in high tryptophan concentration, and ubiquitinylation is also involved (20, 39). The uracil permease, Fur4, in the presence of its substrate is able to leave the Golgi apparatus and is sorted to the endosomal system for its degradation. Ubiquitinylation is then required for delivering Fur4 into the vacuolar lumen but is not a dominant signal for Golgi-to-endosome trafficking (32). Some of these permeases are phosphorylated; however, the role of this post-translational modification in direct sorting to the vacuole remains unclear. For example, Fur4 phosphorylation is required for ubiquitinylating the permease present at the cell surface but is not implicated in vacuolar sorting from the Golgi apparatus (32).

What is the physiological relevance of the cellular distribution control of Ynt1 by phosphorylation? The analysis of this phosphorylation did not reveal differences in growth with the wild-type strain at different nitrate concentrations. However, because Ynt1 is a high affinity transporter for nitrate (Km ∼2 μm) (10, 11), Ynt1 phosphorylation could have a physiological role under very restrictive nitrogen availability. To this end we evaluated the role of different versions of Ynt1 in nitrate assimilatory genes induction, using YNR1-lacZ as read-out. Induction was dependent on Ynt1, and in a Ynt1S→A version was remarkably lower with respect to wild-type Ynt1 (Fig. 5). We explained this delay as a result of a lower accumulation of Ynt1 at the plasma membrane when phosphorylation was impaired, thus reducing the uptake of nitrate at trace level.

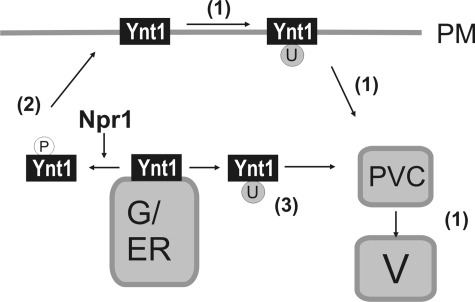

In conclusion, our data strongly suggest that at an early step of the secretion route Ynt1 phosphorylation controls two alternative cellular destinations for Ynt1: the vacuole or the plasma membrane. This regulation is illustrated in Fig. 8. We speculate that the role of phosphorylation at the early stages of Ynt1 trafficking is to assure the delivery of the transporter to the plasma membrane under nitrogen starvation, a physiological condition that could divert proteins transiting along the secretory pathway toward bulk degradation. The presence of nitrate transporter at the plasma membrane would allow yeast to efficiently utilize nitrate traces.

FIGURE 8.

Comprehensive model of Ynt1 post-translational regulation. Plasma membrane Ynt1 down-regulation is triggered by reduced nitrogen sources added to the medium or produced from nitrate assimilation, and it requires ubiquitin-dependent endocytosis and vacuolar degradation (1). Phosphorylation, dependent on Npr1 kinase, is essential to Ynt1 delivery to cell surface under nitrogen limitation (2). The vacuolar sorting of the dephosphorylated Ynt1 requires ubiquitinylation (3). Under nitrogen deprivation, the phosphorylation of Ser residues, along with a reduced endocytosis, allows the accumulation of Ynt1 at the plasma membrane. U, ubiquitinylation of Ynt1; P, phosphorylation of Ynt1; ER/G, endoplasmic reticulum/Golgi; PVC, pre-vacuolar compartment; and V, vacuole.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rhein Biotech (Germany) for providing us NPR1, END4, and PEP12 DNA sequence. We are grateful to R. Serrano (Valencia) for Pma1 antiserum, Guido Jones for the English revision of the manuscript, and A. Lancha for suggestions.

This article is dedicated to Carlos Gancedo (IIB, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Madrid) for his long-standing support.

This work was supported in part by the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia (MEC, Spain) (Grant BFU2007-60172/BMC to J. M. S.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: Npr1, nitrogen permease reactivator 1 kinase; GFP, green fluorescent protein; TOR, target of rapamycin.

J. A. K. W. Kiel, personal communication.

References

- 1.Crawford, N. M. (1995) Plant Cell 7 859-868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernandez, E., and Galvan, A. (2007) J. Exp. Bot. 58 2279-2287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galvan, A., and Fernandez, E. (2001) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 58 225-233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marzluf, G. A. (1993) Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 47 31-55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siverio, J. M. (2002) FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 749 277-284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crawford, N. M., and Arst, H. N. (1993) Annu. Rev. Genet. 27 115-146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller, A. J., Fan, X., Orsel, M., Smith, S. J., and Wells, D. M. (2007) J. Exp. Bot. 58 2297-2306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Llamas, A., Igeno, M. I., Galvan, A., and Fernandez, E. (2002) Plant J. 30 261-271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Navarro, F. J., Perdomo, G., Tejera, P., Medina, B., Machin, F., Guillen, R. M., Lancha, A., and Siverio, J. M. (2003) FEMS Yeast Res. 4 149-155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Machin, F., Medina, B., Navarro, F. J., Perez, M. D., Veenhuis, M., Tejera, P., Lorenzo, H., Lancha, A., and Siverio, J. M. (2004) Yeast 21 265-276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perez, M. D., Gonzalez, C., Avila, J., Brito, N., and Siverio, J. M. (1997) Biochem. J. 321 397-403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu, K. H., and Tsay, Y. F. (2003) EMBO J. 22 1005-1013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Navarro, F. J., Machin, F., Martin, Y., and Siverio, J. M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 13268-13274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang, Y., Li, W., Siddiqi, M. Y., Kinghorn, J. R., Unkles, S. E., and Glass, A. D. M. (2007) New Phytol. 175 699-706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wirth, J., Chopin, F., Santoni, V., Viennois, G., Tillard, P., Krapp, A., Lejay, L., Daniel-Vedele, F., and Gojon, A. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 23541-23552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magasanik, B., and Kaiser, C. A. (2002) Gene (Amst.) 290 1-18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abeliovich, H., and Klionsky, D. J. (2001) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65 463-479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen, E. J., and Kaiser, C. A. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99 14837-14842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberg, K. J., Rowley, N., and Kaiser, C. A. (1997) J. Cell Biol. 137 1469-1482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck, T., Schmidt, A., and Hall, M. N. (1999) J. Cell Biol. 146 1227-1237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crespo, J. L., and Hall, M. N. (2002) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66 579-591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmidt, A., Beck, T., Koller, A., Kunz, J., and Hall, M. N. (1998) EMBO J. 17 6924-6931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Craene, J. O., Soetens, O., and Andre, B. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 43939-43948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faber, K. N., Haima, P., Harder, W., Veenhuis, M., and AB, G. (1994) Curr. Genet. 25 305-310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brito, N., Perez, M. D., Perdomo, G., Gonzalez, C., Garcia-Lugo, P., and Siverio, J. M. (1999) Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 53 23-29 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montanini, B., Viscomi, A. R., Bolchi, A., Martin, Y., Siverio, J. M., Balestrini, R., Bonfante, P., and Ottonello, S. (2006) Biochem. J. 394 125-134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ingrell, C. R., Miller, M. L., Jensen, O. N., and Blom, N. (2007) Bioinformatics 23 895-897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ammerer, G., Hunter, C. P., Rothman, J. H., Saari, G. C., Valls, L. A., and Stevens, T. H. (1986) Mol. Cell. Biol. 6 2490-2499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woolford, C. A., Daniels, L. B., Park, F. J., Jones, E. W., Van Arsdell, J. N., and Innis, M. A. (1986) Mol. Cell. Biol. 6 2500-2510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raths, S., Rohrer, J., Crausaz, F., and Riezman, H. (1993) J. Cell Biol. 120 55-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Becherer, K. A., Rieder, S. E., Emr, S. D., and Jones, E. W. (1996) Mol. Biol. Cell 7 579-594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blondel, M. O., Morvan, J., Dupre, S., Urban-Grimal, D., Haguenauer-Tsapis, R., and Volland, C. (2004) Mol. Biol. Cell 15 883-895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gerrard, S. R., Levi, B. P., and Stevens, T. H. (2000) Traffic 1 259-269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soetens, O., De Craene, J. O., and Andre, B. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 43949-43957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hicke, L., Zanolari, B., and Riezman, H. (1998) J. Cell Biol. 141 349-358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marchal, C., Haguenauer-Tsapis, R., and Urban-Grimal, D. (1998) Mol. Cell. Biol. 18 314-321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen, E. J., and Kaiser, C. A. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 161 333-347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Helliwell, S. B., Losko, S., and Kaiser, C. A. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 153 649-662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Umebayashi, K., and Nakano, A. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 161 1117-1131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]