Abstract

The mammalian spliceosome has mainly been studied using proteomics. The isolation and comparison of different splicing intermediates has revealed the dynamic association of more than 200 splicing factors with the spliceosome, relatively few of which have been studied in detail. Here, we report the characterization of the Drosophila homologue of microfibril-associated protein 1 (dMFAP1), a previously uncharacterized protein found in some human spliceosomal fractions (Jurica, M. S., and Moore, M. J. (2003) Mol. Cell 12 , 5-14). We show that dMFAP1 binds directly to the Drosophila homologue of Prp38p (dPrp38), a tri-small nuclear ribonucleoprotein component (Xie, J., Beickman, K., Otte, E., and Rymond, B. C. (1998) EMBO J. 17,2938 -2946), and is required for pre-mRNA processing. dMFAP1, like dPrp38, is essential for viability, and our in vivo data show that cells with reduced levels of dMFAP1 or dPrp38 proliferate more slowly than normal cells and undergo apoptosis. Consistent with this, double-stranded RNA-mediated depletion of dPrp38 or dMFAP1 causes cells to arrest in G2/M, and this is paralleled by a reduction in mRNA levels of the mitotic phosphatase string/cdc25. Interestingly double-stranded RNA-mediated depletion of a wide range of core splicing factors elicits a similar phenotype, suggesting that the observed G2/M arrest might be a general consequence of interfering with spliceosome function.

Splicing of pre-mRNAs is a catalytic reaction that involves two successive trans-esterification steps. This process is carried out by a highly conserved ribonucleoprotein complex, called the spliceosome. The spliceosome consists of five snRNAs (U1, U2, U4, U5, and U6) and more than 200 proteins, making it one of the largest and most complex molecular machines studied (1). Spliceosome assembly is a sequential process that is initiated by the recruitment of the U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (snRNP)2 to the 5′-splice donor site to form a “commitment complex” (“E complex” in mammals) (3, 4). Subsequently, recruitment of the U2 snRNP to the branch site by the U2 auxiliary factor of 65 kDa (U2AF65) generates the “pre-spliceosome” (“A complex” in mammals) (5-8). A preformed U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNP unit then joins the U1-U2-pre-mRNA complex to form the “complete spliceosome” (“B complex” in mammals). To activate the complete spliceosome several conformational rearrangements must take place (reviewed in Ref. 9). These include unwinding of base pairings between U1 and the 5′-splice site and between U6 and U4, as well as the formation of a new base pair interaction between U5 and U6 snRNPs and the 5′-splice site and U6 and U2. As a result, U1 and U4 snRNPs are released and an active spliceosome is formed (10, 11). The yeast RNA helicases Prp28p and Brr2p are both implicated in the structural rearrangements that take place during the activation step of the spliceosome (11). Prp28p is thought to be important for the unwinding of base pairings between U1 and the 5′-splice site (12) and Brr2p is implicated in unwinding the U4/U6 duplex, which is essential for the release of U4 snRNP (13). Moreover, a pre-assembled Prp19p (pre-mRNA processing factor 19 protein)-associated protein complex named the 19 complex (NTc) in yeast and the Cdc5-Prp19 complex in humans is required for maturation of the spliceosome (14, 15).

Much of the mechanistic insight into the spliceosome has been derived from yeast genetics. The ease of generating temperature-sensitive mutant alleles has allowed a detailed functional characterization of individual splicing factors. In contrast, the function of the mammalian spliceosome has mostly been studied by proteomic analysis of spliceosome intermediates (15-21). The isolation and comparison of different spliceosome intermediates has given insights into the dynamics of the spliceosome and revealed that excision of an intron from a pre-mRNA occurs largely by the same sequential path in yeast and higher eukaryotes (15, 16, 19, 20). Importantly, purifications of mammalian spliceosomes have added a vast array of elements to the pre-existing list of conserved core splicing factors. Many of these have no previous connection to splicing and require functional validation (1).

Yeast Prp38p is a U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNP component that plays an important role in the maturation of the spliceosome. Prp38p activity is dispensable for the initial assembly of the spliceosome, but is required in a later step for the release of U4 snRNP and activation of the spliceosome (2). It has been speculated that Prp38p might recruit (or activate) an RNA unwinding activity necessary for the release of U4 snRNA and the integration of U6 snRNA into the active site of the spliceosome (2). The identity of this RNA unwinding activity remains unknown, but Brr2p is a possible candidate. The mammalian Prp38p homologue does not appear to be stably associated with the tri-snRNPs and has been recovered in surprisingly few spliceosomal purifications (1). This apparent discrepancy between yeast and higher eukaryotes prompted us to study the Drosophila Prp38 protein in more detail.

We initially used a proteomics approach to identify proteins associated with dPrp38. In agreement with its function in yeast, dPrp38 associates with several homologues of splicing factors that are required for activation of the spliceosome. In addition, we identified dMFAP1 (microfibrillar-associated protein 1), which binds directly to dPrp38. We show that dMFAP1, like dPrp38, associates with spliceosome components and is required for pre-mRNA processing. Finally, we find that dPrp38 and dMFAP1 are required for normal string/cdc25 mRNA levels and G2/M progression in cultured cells and for cell survival and growth in vivo.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Generation of dprp38 Mutant and Transgenic Flies—The G19491 P-element (Genexel Inc.) was inserted 798 bp into the open reading frame of dprp38 (dprp38G19491). The dprp38E1 mutant was generated by mobilization of the G19491 P-element using standard genetic techniques and identified by PCR using the following primers: dPrp38-5.03, CTTTGCTCTCACTGCGGAGCT; dPrp38-3.3: AGCGAGCAAGTAGGAACGGAACGGAACGGC. In dprp38E1, the region between bp 428 and 798 of the open reading frame has been deleted. The dmfap1 D2-1 RNAi line was generated by cloning two 400-bp inverted repeats of dmfap1 into the pMF3 vector using the unique EcoRI and XbaI restriction sites. The 400-bp repeats were amplified from genomic DNA using a forward primer containing a BglII site at the 5′ end and reverse primers containing an EcoRI or a XbaI site at the 3′ end: dMFAP1ForwBglII, GAGAGATCTCGACGAGGTGGAATACGAGG; dMFAP1RevEco, GGAATTCCGAACTTGGTGGTGTCCTGG; dMFAP1RevXba, GTCTAGACGAACTTGGTGGTGTCCTGG.

The two PCR products were digested with BglII and EcoRI or BglII and XbaI and cloned into the same pMF3 vector digested with EcoRI and XbaI. The final construct was introduced into the germline by injections in the presence of transposase as previously described (22, 23). The dMFAP1 (15610) and dPrp38 (21136) RNAi lines were obtained from the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center.

Genotypes—The following genotypes were used: wiso (Fig. 1, C and D). hs-FLP; FRT42D, dprp38G19491/FRT42D Ubi-GFP (Fig. 1, F and G). hs-FLP; FRT42D, Ubi-GFP, dprp38E1/FRT42D, M(2)531 (Fig. 1, H-K). hs-FLP; Act >cd2 > Gal4, UAS-GFP (Fig. 5, A-C). hs-FLP; UAS-RNAi-dmfap1/Act > cd2 > Gal4, UAS-GFP (Fig. 5, D-F). hs-FLP; UAS-RNAi-dprp38/Act > cd2 > Gal4, UAS-GFP (Fig. 5, G-I).

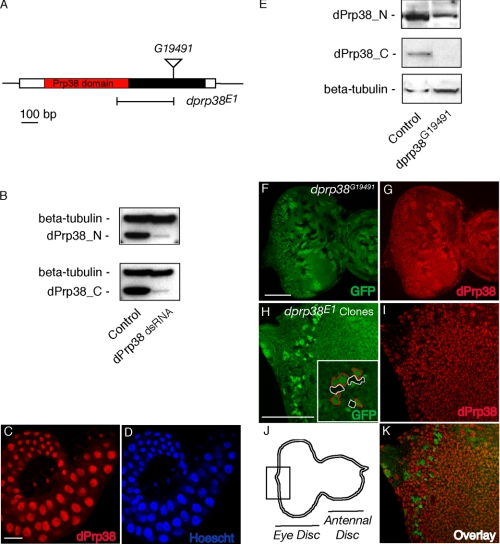

FIGURE 1.

dPrp38 is a nuclear protein required for developmental growth and proliferation. A, schematic of the dprp38 locus. dPrp38 is encoded by a single exon. The N-terminal part encodes a region with homology to Prp38 (red). The position of the P-element inserted in dprp38G19491 and the imprecise excision deletion mutant (dprp38E1) are indicated. B, immunoblots on cell extracts prepared from S2 cells treated with dsRNA corresponding to GFP (control) or dPrp38 probed with antibodies recognizing the C- (dPrp38_C) and N-terminal (dPrp38_N) part of dPrp38. C and D, dPrp38 is localized in the nucleus. Wild-type salivary gland tissues from third instar larvae stained with the anti-dPrp38_C antibody in red (C) or a nuclear dye (D). E, whole extracts from control adult flies or flies homozygous mutant for dprp38G19491 were used for immunoblotting with dPrp38_N (top panel), dPrp38_C (middle panel), and anti-β-tubulin (bottom panel) antibodies. F-K, eye imaginal discs from third instar larvae. Posterior is to the left. F and H, the scale bar is at 100 μm. Mitotic clones of dprp38G19491 (F and G) or dprp38E1 (H-K) mutant tissue marked by the absence of GFP (F) or two copies of GFP (H and K) and stained with the dPrp38_C antibody in red (G, I, and K). Inset in H is a blow-up of a region of the image, with dprp38 mutant areas circled in red and homozygous Minute clones in white. J, a schematic representation of the eye-antennal disc with the area in H, I, and K boxed.

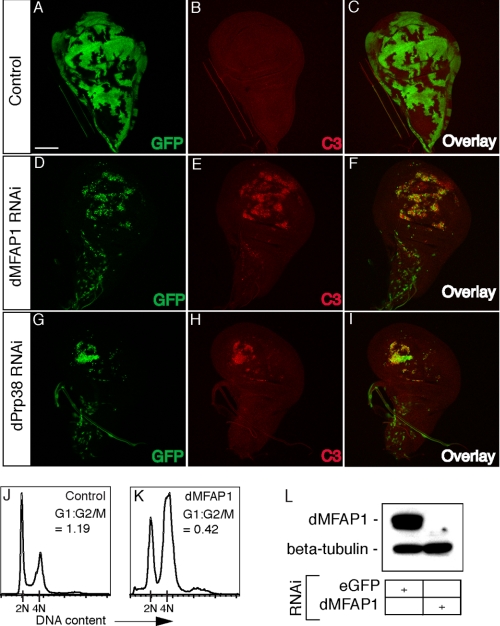

FIGURE 5.

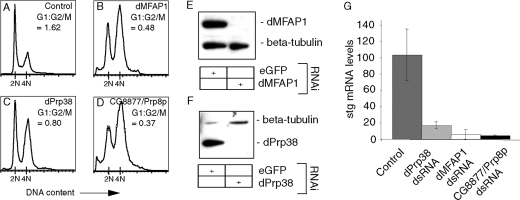

dPrp38 and dMFAP1 are required for G2/M progression and developmental growth and proliferation. A-I, wing imaginal dics from third instar larvae. Posterior is to the right. Wild-type clones (A-C) or clones expressing dprp38 and dmfap1 RNAi constructs (D-I) were generated using the FLP-out technique (marked with GFP in A, D, and G). Clones with reduced levels of dMFAP1 (D-F) or dPrp38 (G-I) are smaller than control clones (A-C) generated at the same time and undergo apoptosis as measured by increased levels of cleaved caspase 3 staining in the clones (red in E and H). J-K, cells depleted of dMFAP1 arrest in G2/M. S2 cells were treated with dsRNA targeting eGFP (control) or dmfap1 for 3 days. Cells were fixed, stained with propidium iodide, and analyzed by flow cytometry. The ratio of cells in the G2/M relative to G1 phase is indicated for each treatment (G1:G2/M). L, immunoblotting confirms that dMFAP1 protein levels are reduced in cells treated with dsRNA targeting dmfap1 compared with control cells. Anti-β-tubulin is used as a loading control.

Immunohistochemistry—Mosaic tissues were obtained using the hs-Flp/FRT system (24). Salivary glands and wing and eye imaginal discs were dissected from L3 larvae (120 h after egg laying) in 1× PBS. S2 cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 106/ml on chamber slides (Nunc, Fig. 6, J-M). Tissues and cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 20 min at room temperature, washed four times in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 (PBS-T), blocked for 2 h in PBS-T containing 10% goat serum (PBS-TG), and incubated with primary antibodies in PBS-TG overnight at 4 °C. Rabbit anti-cleaved caspase-3 (Asp175) (Cell Signaling), rabbit anti-dPrp38_C, mouse anti-α-tubulin (Sigma), and rabbit anti-phospho-histone H3 (PH3) (Upstate) were used at 1:500. The next day, cells and tissues were washed, blocked in PBS-TG, and incubated with secondary antibodies at 1:500 (rhodamine red X donkey anti-rabbit, anti-mouse, anti-guinea pig, and fluorescein (isothiocyanate) donkey anti-rabbit from Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 2 h at room temperature. Hoechst (Sigma) was added to the secondary antibody mixture during the last 30 min of the incubation to stain DNA (Fig. 1D). After washes, cells and tissues were mounted in Vectashield. Fluorescence images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM510 Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope (×25 and 40 objectives) and processed using Adobe photoshop CS2.

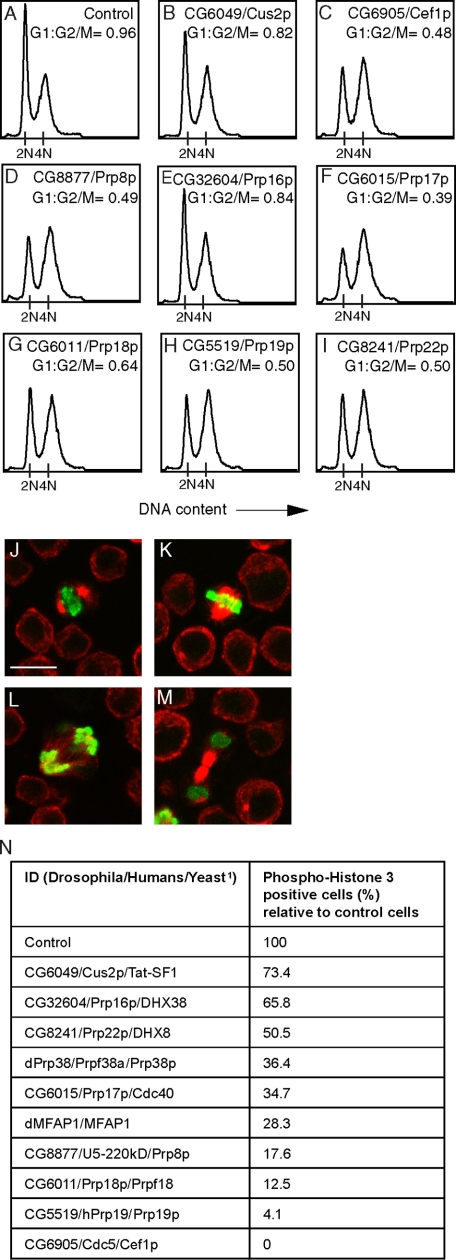

FIGURE 6.

Depletion of several core components of the spliceosome results in G2/M arrest. A-I, S2 cells were treated with dsRNAs targeting eGFP (control) or genes encoding the indicated splicing factor homologues for 3 days. After fixing and staining with propidium iodide, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. The ratio of cells in the G2/M relative to G1 phase is indicated for each treatment (G1:G2/M). J-M, S2 cells stain positive for PH3 from the onset of mitosis (J), through metaphase (K), anaphase (L) to cytokinesis (M). S2 cells were stained with anti-γ-tubulin (in red) and anti-PH3 (in green) antibodies. J, the scale bar is at 100 μm. N, depletion of various splicing factor homologues results in a decrease in numbers of PH3-positive cells. Cells were treated with dsRNA targeting the indicated proteins for 4 days and stained with anti-γ-tubulin and anti-PH3 antibodies. For each set-up, the percentage of PH3-positive cells relative to that of control cells was calculated by examining a minimum of 1200 cells. 1, when a protein does not have an obvious homologue in yeast, the fly and human IDs are indicated.

Cell Culture—Drosophila S2 cells were grown in Schneider's medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Sigma), 50 units/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen) at 25 °C. Transfections were done using Effectene (Qiagen).

Antibodies—The anti-dPrp38_N and anti-dPrp38_C rabbit antibodies and the anti-dMFAP1 guinea pig antibody were generated and affinity purified by Eurogentec SA (Seraing, Belgium) against peptides corresponding to amino acids 1-15 and 315-330 of dPrp38 and 43-57 of dMFAP1.

Plasmids—dPrp38Δ, dPrp38G19491, dMFAP1ΔN, and dMFAP1ΔC were PCR amplified and cloned into the pENTR™/D-TOPO vector using gene-specific primers: for dPrp38Δ, sense primer, CACCATGGCCAACCGCACGGTGAAGG, antisense primer, GATTTCGTTGTTTTCCTCGAG; for dPrp38G19491, sense primer, CACCATGGCCAACCGCACGGTGAAGG, antisense primer, TCCTCGTTGTGGGTGTCCCG; for dMFAP1ΔN, sense primer, CACCATGGACAACGAACCCCGCCTGAAG, antisense primer, TTACTCCATCTTTTTTCGCTTCG; and for dMFAP1ΔC, sense primer, CACCATGAGTGCAGCCACCGCCGCCG, antisense primer, CTCCTCGCTTTCGGTCTCCTC. To generate HA-dPrp38Δ, HA-dPrp38G19491, HA-dMFAP1ΔN, and HA-dMFAP1ΔC, dPrp38Δ, dPrp38G19491, dMFAP1ΔN, and dMFAP1ΔC were cloned into the Gateway pAHW vector (Drosophila Gateway Vector Collection). To generate GST-dMFAP1, dMFAP1 was PCR amplified using gene-specific sense and antisense primers containing EcoRI and NotI restriction sites, respectively, and subcloned into the pGEX4T-1 vector (Amersham Biosciences) using the EcoRI and NotI restriction sites. To generate His-dPrp38, dPrp38 was PCR amplified using gene-specific sense and antisense primers containing KpnI and HindIII restriction sites, respectively, and subcloned into the pRSET-A vector (Invitrogen) using KpnI and HindIII restriction sites.

Immunoprecipitation and GST Pull-down—Immunoprecipitations of dPrp38 and dMFAP1 were performed from 1 × 109 (Figs. 3B and 4B) or 1 × 107 (Fig. 3, D and G-J) S2 cells. Cells were lysed in 10 ml (Figs. 3B and 4B) or 200 μl (Fig. 3, D and G-J) of Buffer A (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 150 mm NaCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 1 mm EGTA, 0.5 m sodium fluoride, phosphatase inhibitor mixture 2 (Sigma), Complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche)), and cell extracts were cleared of membranous material by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 15 min. Extracts were incubated with protein A-Sepharose 4B beads (Amersham Biosciences) for 1 h to reduce nonspecific binding of proteins to the beads in the subsequent purifications. Next, the pre-cleared extracts were incubated with 800 (Figs. 3B and 4B) or 80 μl (Fig. 3, D and G-J) of protein A-Sepharose beads and 10 (Figs. 3B and 4B) or 1 μl (Fig. 3, D and G-J) of the relevant antibody for 2 h. A rabbit anti-GFP antibody was used in the control purifications. Subsequently, beads were washed 3 times in Buffer A, boiled in sample buffer (Invitrogen), and resolved by SDS-PAGE on 8-16% gradient gels (Bio-Rad, Fig. 4B) or 4-12% NuPage BisTris gels (Invitrogen, Fig. 3, B, D, and G-J). Individual protein bands were visualized by Brilliant Blue G-colloidal concentrate (Sigma) staining, cut out, and identified by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry at the Taplin Biological Mass Spectrometry Facility (Figs. 3B and 4B).

FIGURE 3.

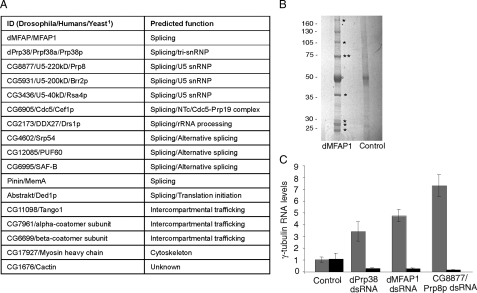

dPrp38 associates with several splicing factors and a previously uncharacterized protein dMFAP1. A, table summarizing proteins isolated in complex with endogenous dPrp38. 1, when a protein does not have an obvious homologue in yeast, the fly and human IDs are indicated. B, to identify dPrp38-associated proteins, purifications were performed from S2 cells using anti-dPrp38_N, anti-dPrp38_C, or anti-GFP (control) antibodies. The final eluates were resolved on a 4-12% NuPage BisTris gel, and stained with Brilliant Blue G-colloidal concentrate. Visible bands (asterisks) were excised and identified by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. The band corresponding to dPrp38 is indicated by two asterisks. C, the specificity of the anti-dMFAP1 antibody was confirmed by immunoblotting on cell extracts prepared from S2 cells treated with dsRNA corresponding to eGFP (control) or dmfap1 for 3 days. Anti-β-tubulin was used as a loading control. D, dMFAP1 co-immunoprecipitates with dPrp38. dPrp38, dMFAP1, and control (anti-GFP) immunoprecipitates from S2 cells were blotted for dMFAP1 (top panel) and dPrp38 (bottom panel). E and F, dMFAP1 interacts directly with dPrp38. E, bacterially expressed GST-dMFAP1 or GST alone was incubated with bacterially expressed His-dPrp38, and GST pull-downs were probed for the presence of His-dPrp38 using one of our dPrp38 antibodies (middle panel) or GST-dMFAP1 (top panel) and GST (bottom panel) using an anti-GST antibody. F, bacterially expressed His-dPrp38 or an unrelated His-tagged peptide (control) was incubated with cleaved GST-dMFAP1, and His pull-downs were probed for the presence of dMFAP1 using our anti-dMFAP1 antibody (top panel) or His-dPrp38 using one of our anti-dPrp38 antibodies (bottom panel). G and H, dPrp38 interacts with the C-terminal part of dMFAP1. dPrp38 (G and H), HA-dMFAP1ΔN(G), HA-dMFAP1ΔC(H), and control (G and H, anti-V5) immunoprecipitates from S2 cells were blotted for dMFAP1 (top panel) and dPrp38 (bottom panel). I and J, dMFAP1 interacts with the N-terminal part of dPrp38. dMFAP1 (I and J), HA-dPrp38P (I), HA-dPrp38Δ (J), and control (I and J, anti-V5) immunoprecipitates from S2 cells were blotted for dMFAP1 (top panel) and dPrp38 (bottom panel). HA, hemagglutinin.

FIGURE 4.

dMFAP1 forms a complex with several splicing factor homologues and is required for pre-mRNA processing. A, table summarizing proteins that were isolated in complex with endogenous dMFAP1. 1, when a protein does not have an obvious homologue in yeast, the fly and human IDs are indicated. B, to identify proteins that form a complex with dMFAP1, purifications were performed from S2 cells using anti-dMFAP1 or anti-GFP (control) antibodies. Eluates were resolved on a SDS-PAGE gel, and stained with Brilliant Blue G-colloidal concentrate. Visible bands (marked by asterisks) were excised and identified by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. The band corresponding to dMFAP1 is indicated by two asterisks. C, dMFAP1 is required for pre-mRNA processing. Total RNA was extracted from the S2 cells, and γ-tubulin mRNA (black) and pre-mRNA (gray) levels were measured after 1st strand cDNA synthesis by qPCR (see “Experimental Procedures”). mRNA and pre-mRNA levels were compared between the different samples by normalization to levels of the intronless his3 transcript.

GST pull-downs were performed using 1 μg of bacterially produced GST or GST-dMFAP1 protein with 50 ng of bacterially produced His-dPrp38 protein (Fig. 3E). His-dPrp38 pull-downs were performed using 500 ng of bacterial-produced His-dPrp38 or His-Peptide (control) and 800 ng of cleaved GST-dMFAP1 (Fig. 3F).

Western Blotting—Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE using 4-12% gradient gels (Invitrogen) and transferred electrophoretically to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Amersham Biosciences). The membranes were incubated for 1 h in Blocking Buffer (PBS (137 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 4.3 mm Na2HPO4, 1.47 mm KH2PO4, pH 8), 5% milk), and incubated overnight at 4 °C in the same buffer containing primary antibodies at the following dilutions: anti-dPrp38_N, anti-dPrp38_C, anti-dMFAP1, 1:1000; anti-β-tubulin (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), 1:2000; anti-GST (Cell Signaling Technology), 1:2000. Membranes were washed three times in PBS-T, blocked for 1 h, and probed with secondary antibodies diluted 1:5000 in Blocking Buffer for 1 h at room temperature. After three washes in PBS-T, chemiluminescence was observed using the ECL Plus Western blotting detection system (Amersham Biosciences).

dsRNA—dsRNAs were synthesized with a Megascript T7 kit (Ambion). DNA templates for dsRNA synthesis were PCR amplified from fly genomic DNA or plasmids using primers that contained 5′T7 RNA polymerase-binding sites followed by sense or antisense sequences. The primers were designed using the E-RNAi at the DKFZ, Heidelberg (www.dkfz-heidelberg.de/signaling/ernai.html). For eGFP, the following primers were used: sense primer, GGTGGTGCCCATCCTGGT, antisense primer TCGCGCTTCTCGTTGGGG; for CG6049/cus2, sense primer, CTCCTCCTTTCTCTTGGCCT, antisense primer, CAAAACGGACGAAACTCCAT; for CG6905/cef1, sense primer, TCTCTAGCTCTCGCTTTCGG, antisense primer, AGCAGGTAGTCAAGCTGGGA; for CG8877/prp8, sense primer, TTGCTCCTTGGTCTGCTTTT, antisense primer, CATTCACACCTCTGTGTGGG; for CG32604/prp16, sense primer, TGTTCAGCAAGAACACCTGC, antisense primer, GCCGGAATCGATAACGTAGA; for CG6015/prp17, sense primer, CATTGATGTGGGCCTTCTCT, antisense primer, CACGCACCATCCCTAGTTTT; for CG6011/prp18, sense primer, GATGTCTCGCAGACTGTCCA, antisense primer, CTGAACGCCAAGAACACAGA; for CG5519/prp19, sense primer, AGCCAGATAGGTTCCGCTTT, antisense primer, ACAAACACTGGGCATTCTCC; for CG8241/prp22, sense primer, GCAGTCGGCTTTGTCTAAGG, antisense primer, ATGGTGTAGCCAACCTCCTG; for CG30342/dprp38, sense primer, AGCGTGTCTGCGACATTATACTGCCCC, antisense primer, AGCCTCGCGAGTCCCGTTCCC; and for CG1017/dmfap1, sense primer, AGGGAGCACAGGGAGCGATTCAGCGG, antisense primer, AGCATTCGCTTGAGTTCACGCAGCTTC.

DNA Profiles—Cells were seeded in 35-mm wells at a density of 7 × 105 cells/ml in a total of 3 ml of complete medium/well and treated with dsRNA (20 μg/well) targeting genes encoding the indicated gene products for 3 days. Subsequently, cells were harvested, collected by centrifugation, washed two times in PBS, fixed in cold 70% ethanol, and stored at 4 °C. Subsequent steps were performed at room temperature. Fixed cells were washed twice in PBSA, treated with 50 μl of 100 μg/ml RNase A (Sigma) for 15 min and 250 μl of 40 μg/ml propidium iodide for a further 30 min, and then analyzed by flow cytometry.

BrdUrd Pulse-Chase—Cells were seeded in 35-mm wells at a density of 7 × 105 cells/ml in a total of 3 ml of complete medium/well and treated with dsRNA (20 μg/well) targeting eGFP or dprp38 for 4 days. 15 μm BrdUrd (Sigma) was added to the medium for 15 min, then cells were washed three times with PBS, and BrdUrd-free medium was added. Cells were harvested at the indicated time points, collected by centrifugation, washed two times in PBS, fixed in cold 70% ethanol, and stored at 4 °C. Fixed cells were washed twice in PBS and once in PBS-BT (PBS + 0.1% bovine serum albumin + 0.2% Tween 20). 2 μl of monoclonal mouse anti-BrdUrd (BD Biosciences) were added directly to the cell pellets, incubated for 20 min in the dark, then cells were washed twice in PBS-BT and incubated in 50 μl of fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated rabbit antimouse F(ab′)2 fragments (DAKO) diluted 1:10 in PBS-BT for 20 min. Cells were washed twice in PBSA, treated with 50 μl of 100 μg/ml RNase A (Sigma) for 15 min and 250 μl of 40 μg/ml propidium iodide for a further 30 min and then analyzed by flow cytometry.

Quantitative RT-PCRs—S2 were treated with dsRNA (20 μg/well) targeting genes encoding the indicated gene products for 3 days. Total RNA was isolated from the cells using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) and treated with RQ1 DNase (Promega). Total RNA (1.5 μg) was used for first-strand cDNA synthesis with avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase and oligo-p(dT)15 primer (mRNA) or oligo-p(dN)6 (total RNA) (Roche). To measure pre-mRNA levels, quantitative PCRs (qPCRs) were performed on reverse-transcribed total RNA using one intron- and one exon-specific primer. To measure mRNA levels, qPCRs were carried out on reverse-transcribed total mRNA using exon-specific primers. For stg mRNA, sense primer, GCAGTTCTCCTTCTCAACGG, antisense primer, GGAGGAGCTGTCGTTCTACG; for γ-tubulin(23C) pre-mRNA, sense primer, GCGCCAAACCTACTATTAACTC, antisense primer, CTACATCACTGATCTCGTCCTG; for γ-tubulin(23C) mRNA, sense primer, GGCGGACGACGACCACTAC, antisense primer, GGATAGCGGTCCGCCAGGCGC; for eIF3-S10 pre-mRNA, sense primer, GCGGTGTCTGAAGAGAAAC, antisense primer, CCGCGGATTACATTTTCCAG; for eIF3-S10 mRNA, sense primer, GGCCCGCTATACGCAACGTC, antisense primer, CGGCCATTTTCAGGTAGCCG; for grt pre-mRNA, sense primer, GGAGGCATCAAGAATAACCG, antisense primer, GTTTCGATGCAAAAGGAGCTG; for grt mRNA, sense primer, GCAGCTGCGAGCACACTAATC, antisense primer, CTGGATAATTCTGGGAGGTGG; for hpo pre-mRNA, sense primer, GGAAAACGGAATGCAACAAC, antisense primer, CAATAACAAATGGCCAGCCCTTTC; for hpo mRNA, sense primer, CGGTGAATACCAACAGAGCTC, antisense primer, CGCCACGGCCATCTCCCGC; and for his3, sense primer, GTGAAGTAGTGAACGTGAAC, antisense primer, CCGCCGAGCTCTGGAATCGC. Real-time qPCR was performed with Platinum® SYBR® Green qPCR SuperMix-UDG (Invitrogen). PCR was carried out in 96-well plates using the Chromo 4 Real-time qPCR Detection System (MJ Research). All reactions were performed in four replicates. The relative amount of specific mRNAs and pre-mRNAs under each condition was calculated after normalization to the intronless histone 3 (his3) transcript.

RESULTS

dPrp38 is a nuclear protein required for developmental growth and proliferation. Budding yeast Prp38p belongs to a family of proteins defined by the presence of a conserved 180-amino acid Prp38 homology domain of unknown function (25). Homology searches of the Drosophila proteome revealed a protein encoded by the CG30342 gene, which contains a Prp38 homology domain at its N terminus (Fig. 1A). Overall, the Drosophila protein shares 75% identity with the human Prp38 protein (Prpf38a) and 22% identity with yeast Prp38p (17) (supplemental Fig. S1). We will therefore refer to the CG30342-encoded protein as dPrp38.

To characterize dPrp38 in vitro and in vivo, two antibodies were raised against the N and C termini of dPrp38. The antibodies were tested by Western blotting on extracts from cultured Drosophila S2 cells treated with dsRNAs targeting eGFP (control) or dprp38. In control-treated cells, both antibodies recognized a band of the expected size (35 kDa), which was greatly reduced upon RNAi treatment (Fig. 1B). As expected for a splicing factor, staining of cells in the salivary glands of a wild-type animal revealed that dPrp38 is localized exclusively in the nucleus (Fig. 1, C and D).

To study dprp38 loss-of-function, we obtained a stock bearing a transposon (P-element) insertion in the open reading frame of dprp38 (dprp38G19491) (Fig. 1A). This insertion is predicted to give rise to a deletion of the last 65 amino acids of dPrp38, and a replacement of this region with two amino acids encoded by the P-element. Indeed, in Western blots of fly extracts from dprp38G19491 animals, we did not detect a product with our C-terminal antibody (Fig. 1E, middle panel), whereas the N-terminal antibody detected a product slightly above the wild-type band (Fig. 1E, top panel). The fact that the mutant band migrates higher than expected may be due to aberrant folding.

Next, we used the FLP/FRT system (24) to induce mitotic clones of dprp38G19491 mutant tissue in the eye-imaginal discs (the larval precursor of the adult eye) of heterozygous animals (Fig. 1, F and G). By inducing FLP/FRT-mediated recombination in early eye-imaginal discs, it is possible to generate homozygous mutant clones (no GFP), corresponding wild-type twin-spots (two copies of GFP), whereas heterozygous tissue has one copy of GFP (Fig. 1F). Gene dosage affects dPrp38 expression levels because the anti-dPrp38_C staining is brighter in homozygous wild-type than heterozygous tissue, whereas mutant tissue has little detectable staining (Fig. 1G). However, the dprp38G19491 insertion has no detectable effect on clone growth (compare the size of bright green and black areas in Fig. 1F).

Although the N-terminal half of dPrp38 contains the Prp38 homology domain, the C-terminal half of dPrp38 is much less conserved. Homozygous dprp38G19491 mutant flies are viable, indicating that either dprp38 is not an essential gene or the C-terminal region of dPrp38 is not essential for its function. To resolve this issue, we generated a new dprp38 mutant allele (dprp38E1) by imprecise excision of the P-element in dprp38G19491 (see “Experimental Procedures”). In dprp38E1, a region of 370 bp is deleted from the dprp38 locus (Fig. 1A). This deletion removes part of the Prp38 homology domain. Flies homozygous for dprp38E1 die as first instar larvae, but can be rescued to viability by GAL4/UAS-driven ubiquitous expression of dPrp38 (26). This demonstrates that dprp38 is indeed an essential gene. Due to the early stage of lethality, we were not able to determine whether dprp38E1 is a true protein null mutation, but the severity of the phenotype suggests that dprp38E1 is a functional null or a strong hypomorph.

Attempts to recover dprp38E1 mutant clones in heterozygous animals were unsuccessful, indicating that dPrp38 is required for normal growth and/or proliferation. In developing Drosophila imaginal discs, slow-growing cells are generally eliminated by a process known as cell competition, whereby fast-growing cells actively kill their slower neighbors (27). Minute mutations, which are dominantly acting mutations in ribosomal components, are widely used to alleviate the effects of cell competition (27). By creating mutant clones in a Minute background, the proliferation rate of the surrounding heterozygous tissue is slowed down, allowing unhealthy mutant cells to survive. Thus, GFP-labeled homozygous dprp38E1 mutant clones were generated in eye imaginal discs that are heterozygous for a mutation in a Minute gene (Fig. 1, H-K, and “Experimental Procedures”). Even in this context, only small homozygous dprp38E1 mutant clones could be recovered posterior to the mitotic furrow where cell proliferation has ceased (Fig. 1H, mutant cells are labeled by two copies of GFP, red circles). Notably, the mutant clones were similar in size to clones homozygous for the Minute mutation (marked by absence of GFP, white circles). Because homozygous Minute clones are severely growth defective due to lack of functional ribosomes, this demonstrates that dPrp38 function is indeed essential for cell growth and proliferation.

dPrp38 Is Required for Normal Rates of G2/M Progression—To further investigate the growth/proliferation defect observed in dprp38 mutant tissue (Fig. 1, H, I, and K), DNA profiles were recorded from Drosophila S2 cells treated with dsRNA targeting eGFP (control) or dprp38 for the indicated number of days (Fig. 2, A-D′). In parallel, aliquots were removed to calculate the total number of cells (Fig. 2E) and to analyze dPrp38 protein levels (Fig. 2F). The DNA profiles show that cells treated with dsRNA targeting dprp38 start to accumulate in G2/M after 3-4 days (Fig. 2, A and B′). After 5-6 days, an increase in the sub-G1 (SG1) population is evident, indicating that cells are becoming apoptotic (Fig. 2, C and D′). Consistent with this and our in vivo results (Fig. 1, H, I, and K), dsRNA-mediated depletion of dPrp38 slows down and eventually blocks proliferation after about 4 days (Fig. 2E). Immunoblotting confirms that this correlates with a gradual decrease in dPrp38 protein levels (Fig. 2F).

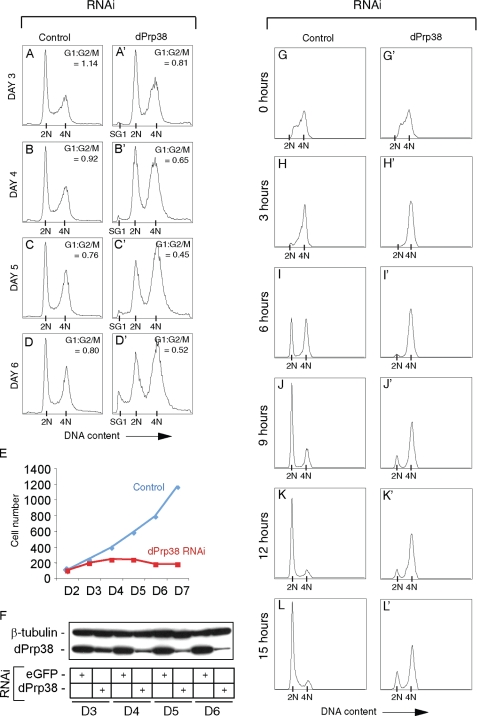

FIGURE 2.

dPrp38 is required for proliferation and G2/M progression. A-D′, cells depleted of dPrp38 gradually accumulate in G2/M and eventually become apoptotic. S2 cells were treated with dsRNA targeting eGFP (control) or dprp38 for the indicated number of days. Cells were fixed, stained with propidium iodide, and analyzed by flow cytometry. The ratio of cells in the G2/M relative to G1 phase is indicated for each treatment (G1:G2/M). The peaks corresponding to the sub-G1 (SG1), G1 (2N), and G2/M (4N) populations are indicated on the x axis. E and F, cells were counted and dPrp38 protein levels measured in parallel. E, control treated (blue) or dPrp38-depleted (red) cells were counted once a day on days 2-7 (D2-D7). F, immunoblotting confirms that dPrp38 protein levels are progressively reduced in cells depleted of dPrp38. Cell extracts were prepared from S2 cells treated with dsRNA corresponding to eGFP (control) or dprp38 on D3-D6 and immunoblotted for dPrp38. Anti-β-tubulin is used as a loading control. G-L′, dPrp38-depleted cells progress through G2/M with severe delays. G-L′, S2 cells were treated with dsRNA targeting eGFP (control) or dprp38 for 4 days and pulse-labeled with BrdUrd for 15 min. Cells were fixed, stained with an anti-BrdUrd antibody and propidium iodide, and analyzed by flow cytometry at the indicated time points after the BrdUrd pulse. Only a small proportion of dPrp38-depleted cells undergo mitosis and enter G1 compared with control cells (compare J′, K′, and L′ with J, K, and L).

A BrdUrd pulse can be used to specifically label S-phase cells within an asynchronously growing population of S2 cells. To study the kinetics with which dPrp38-depleted cells progress through the cell cycle, aliquots of cells treated with dsRNA targeting eGFP (control) or dPrp38 for 4 days (Fig. 2, B and B′) were BrdUrd pulse-labeled for 15 min. Cells were collected at the indicated time points after the BrdUrd pulse, and BrdUrd-positive cells were recorded by flow cytometry (Fig. 2, G-L′). After 3 h, all dPrp38-depleted cells and most of the control cells have left S phase (Fig. 2, H and H′), indicating that cells depleted of dPrp38 undergo DNA replication with normal kinetics. After 6 h, ∼50% of control cells have undergone mitosis and entered G1, whereas the majority of dPrp38-depleted cells are still in G2/M (Fig. 2, I and I′). At the 12-h time point, the majority of control cells are in G1 (Fig. 2K), and after 15 h some start to re-enter the S phase (Fig. 2L). In contrast, the majority of dPrp38-depleted cells remain in G2/M even at the 15-h time point (Fig. 2L′). A small proportion of dPrp38-depleted cells enter G1 after 9-12 h, but with severely delayed kinetics (Fig. 2, J′, K′, and L′). Our results therefore show that dPrp38 is required for normal rates of entry into and/or progression through mitosis.

dPrp38 Associates with Multiple Splicing Factor Homologues—Although yeast Prp38p is an integral component of the tri-snRNP, its mammalian homologue remains poorly characterized and has been isolated in comparatively few spliceosome preparations (1). We therefore wished to identify dPrp38 binding partners to shed light on its function in higher eukaryotes. We performed two large-scale affinity purifications of endogenous dPrp38 from Drosophila S2 cells using the N and C terminus antibodies described above (see “Experimental Procedures”). The samples from the purification procedures were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and individual protein bands were visualized by blue G-colloidal concentrate staining (Fig. 3B). Bands that were present in one or both of the dPrp38 samples, but absent in the control sample, were carefully excised and subjected to mass spectrometry to identify the proteins (bands marked with asterisks in Fig. 3B).

Consistent with a role of dPrp38 in splicing, more than half of the proteins identified by mass spectrometry represent homologues of yeast splicing factors (Fig. 3A). In agreement with the reported function of yeast Prp38p (2), several of the proteins identified as dPrp38-associated proteins are homologues of proteins required for late maturation of the spliceosome in yeast. These include the two U5 snRNP proteins CG8877/U5-220kD/Prp8p and CG10333/U5-100kD/Prp28p and the three NTc/Cdc5-Prp19 components CG6905/Cdc5/Cef1p, CG5519/hPrp19/Prp19p, and CG6197/XAB2/Syf1p (Drosophila/humans/yeast). Additional splicing factor homologues purified in complex with dPrp38 included CG9983, and CG12749. CG9983 and CG12749 are the two closest homologues of Hrp1p/heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 (yeast/humans) in the Drosophila genome. Proteins belonging to this family have been reported to function as negative regulators of pre-mRNA splicing (28).

In addition to splicing factors, we also identified a number of proteins involved in fatty acid synthesis. Interestingly, mouse Prp19p was recently found to be associated with lipid droplets and to have a putative role in lipid droplet biogenesis (29). It is possible that other splicing factors could have a similar additional function in lipid biogenesis. However, we did not further investigate a function of dPrp38 in lipid biogenesis and/or trafficking.

CG1017/dMFAP1 Encodes a dPrp38-binding Protein—As well as homologues of proteins with well characterized functions, our mass spectrometry analysis identified the product of the predicted gene CG1017, which has not previously been studied in any detail (Fig. 3A). This protein is 52% identical to the human MFAP1 (supplemental Fig. S2, alignment). MFAP1 and its homologues contain no recognizable domain; the name refers to the fact that chicken MFAP1 (also known as AMP for associated microfibril protein) was initially identified through a screen for proteins detected by an antiserum raised against a crude microfibril preparation (30). MFAP1 was recovered in a number of purifications of various spliceosomal complexes (15, 16, 18, 20, 21) although its supposed function as an extracellular matrix component initially led to its classification as a purification artifact (21, 31). However, our observation that dMFAP1 can be isolated in complex with dPrp38 prompted us to further characterize the function of dMFAP1.

To verify the interaction between dPrp38 and dMFAP1, we generated an antibody against dMFAP1. The antibody was tested on extracts from cells treated with dsRNA targeting eGFP (control) or dmfap1 (Fig. 3C). The antibody detects a band in control extracts that migrates at the expected size of 75 kDa. The intensity of this band is strongly reduced in extracts from cells depleted of dMFAP1, confirming the specificity of the antibody (Fig. 3C). This antibody and an anti-dPrp38 antibody were used to immunoprecipitate endogenous dMFAP1 and dPrp38. Western blotting revealed the presence of dPrp38 in the dMFAP1 immunoprecipitate and vice versa (Fig. 3D). These data confirm that dMFAP1 forms a complex with dPrp38.

To examine whether the interaction between dPrp38 and dMFAP1 is direct, we performed pull-down experiments using bacterially produced GST (control), GST-dMFAP1 and His-dPrp38 (Fig. 3, E and F). We found that His-dPrp38 can be recovered in the GST-dMFAP1, but not the GST precipitate (Fig. 3E). Similarly, cleaved GST-dMFAP1 co-purifies with His-dPrp38 (Fig. 3F). Thus, the interaction between dPrp38 and dMFAP1 is direct.

Next, we wished to determine the domain in dMFAP1, which mediates its interaction with dPrp38 and vice versa. dMFAP1 does not contain any recognizable functional domains, although the C-terminal half of dMFAP1 is highly conserved in humans. Thus, we tested the ability of N-terminal (amino acids 1-229, HA-dMFAP1ΔC) and C-terminal (amino acid 229-478, HA-dMFAP1ΔN) domains of dMFAP1 to interact with endogenous dPrp38 (Fig. 3, G and H). HA-dMFAP1ΔN, but not HA-dMFAP1ΔC, co-immunoprecipitates with dPrp38, showing that the dMFAP1 interacts with dPrp38 via its conserved C-terminal part. As previously discussed, the dprp38G19491 mutation, which is predicted to cause a deletion of the last 65 amino acids of dPrp38, has no effect on growth and proliferation in vivo (Fig. 1, F and G). If the ability of dPrp38 to interact with dMFAP1 is linked with its essential function, deletion of the C-terminal part of dPrp38 would not be predicted to disrupt its interaction with dMFAP1. Indeed, we find that dPrp38 lacking the last 65 amino acids (amino acids 1-266, HA-dPrp38P) retains its ability to interact with dMFAP1 (Fig. 3I). We also tested whether the Prp38 homology domain of dPrp38 (amino acids 1-180, HA-dPrp38Δ) was sufficient to mediate its interaction with dMFAP1. Although small amounts of dMFAP1 are recovered in the HA-dPrp38Δ precipitate, no HA-dPrp38Δ protein can be detected in the dMFAP1 precipitate (Fig. 3J). Thus, whereas the Prp38 homology domain of dPrp38 might be sufficient for its interaction with dMFAP1, the presence of an additional 86 amino acids in HA-dPrp38P appears to be required for full binding ability. In conclusion, dMFAP1 binds to the N terminus of dPrp38 via its C terminus.

dMFAP1 Associates with Several Splice Factor Homologues—Given the direct interaction between dMFAP1 and dPrp38 and the fact that MFAP1 is present in several human spliceosomal fractions, we wanted to establish whether dMFAP1 associates with other components of the spliceosome. We performed a large-scale purification of endogenous dMFAP1 from Drosophila S2 cells using our anti-MFAP1 antibody. Proteins isolated in complex with dMFAP1 were subjected to SDS-PAGE, visualized by G-colloidal concentrate staining, and identified by mass spectrometry (Fig. 4B).

The majority of proteins isolated in complex with dMFAP1 are predicted or known to function in splicing (Fig. 4A). These include dPrp38/Prpf38a/Prp38p, three U5 snRNP proteins CG8877/U5-220kD/Prp8p, CG5931/U5-200kD/Brr2p, and CG3436/U5-40kD/Rsa4p, one component of the NTc/Cdc5-Prp19 complex, CG6905/Cdc5/Cef1p, and CG2173/DDX27/Drs1p (Drosophila/humans/yeast), which are conserved in yeast, and Hfp/Puf60, CG4602/Srp54, and CG6995/Safb2 (Drosophila/humans) that are conserved among higher eukaryotes. Interestingly, dPrp38 and dMFAP1 are both associated with multiple U5 snRNP proteins and one or several components of the NTc/Cdc5-Prp19 complex, suggesting that they might bridge an interaction between the two complexes.

dMFAP1 Is Required for Pre-mRNA Processing—The observations that dMFAP1 interacts directly with dPrp38 (Fig. 3, E and F) and can be isolated in complex with several splicing factor homologues (Fig. 4, A and B) suggest that dMFAP1 might function in pre-mRNA processing. To further investigate this, we used the γ-tubulin transcript as a read-out to study the requirement for dMFAP1 in pre-mRNA processing. Using quantitative RT-PCR to measure γ-tubulin pre-mRNA and mRNA levels, we observed a 70-84% decrease in γ-tubulin mRNA levels accompanied by a 3.4-7.3-fold increase in γ-tubulin pre-mRNA levels in cells depleted of dMFAP1, dPrp38, or the well characterized splicing factor CG8877/Prp8p (Drosophila/yeast) compared with control cells (Fig. 4C). In addition, we found that dMFAP1 is required for splicing of several other tested transcripts (Fig. S3). Thus, dMFAP1 is indeed a splicing factor.

In Vivo Characterization of dMFAP1—To investigate the requirement for dMFAP1 in vivo, we used a transgenic RNAi line from the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center to reduce dMFAP1 levels in various tissues. Ubiquitous expression of the dmfap1 RNAi construct causes lethality at the larval stage. The lethality is likely to be a consequence of the severe growth defect observed in larvae depleted of MFAP1 (data not shown). To confirm that the observed phenotype was not due to an off-target effect, we generated an independent RNAi line that targets a distinct region of the dmfap1 transcript (D2-1, see “Experimental Procedures”). Consistent with the phenotype we observed with the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center RNAi line, ubiquitous expression of the D2-1 dmfap1 RNAi construct results in larval lethality (data not shown). Thus, dmfap1, like dPrp38, is an essential gene.

To further characterize the growth defect observed in larvae with reduced levels of dMFAP1, we generated GFP-marked dmfap1 RNAi-expressing clones in wing imaginal discs using the Flipout/GAL4 technique (Fig. 5, D-F) (32). For comparison, wild-type clones and clones depleted of dPrp38 were generated in parallel (Fig. 5, A-C and G-I). Consistent with dMFAP1 and dPrp38 being required for normal growth and proliferation, clones with reduced levels of dMFAP1 or dPrp38 (marked by GFP in Fig. 5, D and I) are markedly smaller than control clones (marked by GFP in Fig. 5A) generated at the same time. Furthermore, depletion of dMFAP1 or dPrp38 in the highly proliferating region of the wing pouch results in apoptosis, as measured by increased levels of cleaved-caspase 3 staining in the clones (Fig. 5, E and H). In comparison, no apoptosis could be detected in wild-type clones (Fig. 5B). Thus, normal levels of dMFAP1 and dPrp38 are required for clonal growth and survival in proliferating tissue.

dMFAP1, Like dPrp38, Is Required for G2/M Progression—To further investigate the growth/proliferation defect observed dmfap1-mutant tissue, we analyzed the DNA profile from cultured Drosophila S2 cells depleted of dMFAP1. Consistent with our in vivo results, dsRNA-mediated depletion of dMFAP1 slows down proliferation (data not shown) and cells eventually arrest in G2/M (Fig. 5, J and K). Thus, in cells depleted of dMFAP1 the ratio of cells in G1 and G2/M is 0.42 (Fig. 5K) compared with 1.19 for control-treated cells (Fig. 5J). Using our antibody, we verified the depletion of dMFAP1 (Fig. 5L). Thus, dMFAP1 and dPrp38 are required for G2/M progression and for proliferation and growth during development.

A General Requirement for Splicing Factors in G2/M Progression—Studies carried out with temperature-sensitive mutants in yeast suggest that several splicing factors are important for cell cycle progression (33-40). The cell cycle arrest phenotypes observed with different splicing factor mutants seem to vary (41). This could reflect a difference in the severity of the splicing defects among those mutants or differential requirements for individual splicing factors. Our data (Figs. 2 and 5, J and K) and some evidence from mammalian cells suggest that, in higher eukaryotes, at least certain splicing factors are required for the G2/M transition (42-44). However, it is unclear whether this cell cycle arrest phenotype is general or whether inactivation of different core components of the metazoan spliceosome would give rise to the same variability in cell cycle arrest phenotypes reported in yeast. To address this, we analyzed the DNA profile from S2 cells treated with dsRNAs targeting a range of Drosophila splicing factor homologues (Fig. 6, B-I). These include Cus2p, which functions in the recruitment of U2 to the branch region (45), Cef1p and Prp19p, which are required for maturation of the spliceosome (46-48), Prp8p, Prp16p, Prp17p, and Prp18p, which act in the second step of the splicing reaction (49-52), and Prp22p, which is required for release of the spliced mRNA (53). Depletion of any of these putative splicing factors led to an accumulation of cells in G2/M (Fig. 6, B-I). The degree to which cells arrested in G2/M varied between the different treatments and might reflect the efficiency of the dsRNA-mediated depletion. These data suggest that, in higher eukaryotes, the G2/M arrest phenotype is a general outcome of interfering with the basic splicing machinery. However, it is not clear whether this phenotype is due to the depletion of a factor that is rate-limiting for G2/M progression or to the activation of a cell cycle checkpoint.

To explore the nature of the G2/M arrest in more details, cells depleted of dPrp38, dMFAP1, or the splicing factor homologues indicated in Fig. 6, B-I, were stained with anti-γ-tubulin and anti-phospho-histone 3 (PH3) antibodies. The anti-PH3 antibody labels the condensed chromatin from the onset of mitosis (Fig. 6J) through to cytokinesis (Fig. 6M). To examine whether cells depleted of dPrp38, dMFAP1, or other splicing factors arrest in G2 or during mitosis, a minimum of 1200 cells were examined for each treatment, and the percentage of PH3 positive cells was scored. Depletion of either of the tested splicing factors results in a 26-100% reduction in the number of PH3 positive cells relative to that of control cells (Fig. 6N). We did not note the accumulation of cells at any stage of mitosis. This suggests that these splicing factor-deficient cells are arrested in G2, prior to chromosome condensation, rather than at a later stage during mitosis.

Depletion of dPrp38 or dMFAP1 Causes a Reduction in stg/cdc25 mRNA Levels—In Drosophila, mitosis is triggered by a temporally controlled burst of string/Cdc25 (stg) transcription (54). Stg is a phosphatase, which activates the mitotic kinase Cdk1 and is essential for G2/M progression. In addition to the transcriptional regulation of stg mRNA levels, the presence of an intron in the stg transcript implies that stg mRNA levels are critically dependent on a functional spliceosome. Thus, the observation that depletion of dPrp38, dMFAP1, and a number of core splicing factor homologues cause cells to arrest in G2/M (Figs. 2, 5K, and 6, B-I) suggests that stg mRNA levels might be affected under those conditions. To investigate this, we measured stg mRNA levels in cells depleted of dMFAP1, dPrp38, or CG8877/Prp8p (flies/yeast). As expected, treating cells with dsRNA targeting dmfap1, dprp38, or CG8877/prp8 caused cells to arrest in G2/M (Fig. 7, A-F). Using quantitative RT-PCR to measure stg mRNA levels, we observed an 83-96% decrease in stg mRNA in cells depleted of dMFAP1, dPrp38, or CG8877/Prp8p compared with control cells (Fig. 7G). The observed decrease in mRNA levels could be due to a defect in processing of the stg pre-mRNA or could be an indirect effect caused by interference of a factor required for regulation of stg transcription. Attempts to measure stg pre-mRNA levels by quantitative RT-PCR were unsuccessful. This is most likely due to the low levels and instability of stg pre-mRNA. Consistent with this idea, it has previously been reported that many pre-mRNAs do not accumulate in response to a defective spliceosome, but are degraded by the exosome complex (55).

FIGURE 7.

dMFAP1 and dPrp38 are required for normal stg/cdc25 mRNA levels. A-D, S2 cells were treated with dsRNAs targeting eGFP (control) or genes encoding the indicated protein products. Cells were fixed, stained with propidium iodide, and analyzed by flow cytometry. The ratio of cells in G1 and G2/M is indicated for each treatment. E and F, the effectiveness of the dPrp38 and dMFAP1 depletions was assayed by immunoblotting. G, in parallel, total RNA was extracted from the cells and stg mRNA levels were measured after 1st strand cDNA synthesis by qPCR (see “Experimental Procedures”). stg mRNA levels were compared between the different samples by normalization to levels of the intronless his3 transcript.

DISCUSSION

The essential budding yeast protein Prp38p was the first protein shown to function in maturation of the spliceosome. Prp38p is dispensable for the initial assembly of the spliceosome, but is required for the release of the U4 snRNP and activation of the spliceosome (2). Homologues of Prp38p have been identified in higher eukaryotes, but the primary sequence conservation is poor. Thus, Prp38p is only 24 and 22% identical to Prpf38a (humans) and dPrp38 (Drosophila), respectively. In contrast, dPrp38 is 75% identical to Prpf38a. Despite the low level of homology between Prp38p and its homologues in higher eukaryotes, the data presented here suggest that its function may be conserved in metazoans. Thus, mass spectrometry analysis of proteins isolated in complex with dPrp38 revealed a number of splicing factor homologues that have been implicated in maturation of the spliceosome (Fig. 3). These include two U5 snRNP proteins, dPrp8/U5-220kD/Prp8p and CG10333/U5-100kD/Prp28p, and three components of the NTc/Cdc5-Prp19 complex CG6905/Cdc5/Cef1p, CG9143/XAB2/Syf1p, and CG5519/hPrp19/Prp19p (Drosophila/humans/yeast).

The observation that dPrp38 associates with U5 snRNP proteins and components of the NTc/Cdc5-Prp19 complex (Fig. 3), suggests that it might join the spliceosome concomitantly with or after the tri-snRNP. Consistent with this, purifications of human spliceosome intermediates have revealed that Prpf38a is associated with the B complex (16, 18), but not the A complex (56, 57). Surprisingly, in humans Prpf38a does not appear to be a stable component of the tri-snRNP (20), and it was not recovered in purifications of the BΔU1 spliceosome intermediate (15) or the activated spliceosome (complex B*) (20). The BΔU1 complex represents an intermediate activation step after dissociation of the U1 snRNP, but before unwinding of the U4/U6 duplex (15). This could argue that, in contrast to its yeast counterpart, Prpf38a is not implicated in the activation step or is very loosely associated with the spliceosome and lost during the purification procedures. Consistent with the latter possibility, yeast Prp38p association with the spliceosome appears to be salt-sensitive (2). Our data also favors a role for dPrp38 during the activation step of the spliceosome. Thus, dPrp38 associates with several components of the Cdc5-Prp19 complex, which in humans appear to be stably associated with the BΔ1U and B* complexes (15, 20), but not the B complex (15). The data presented here suggests that, like yeast Prp38p, dPrp38 joins the spliceosome concomitantly with the tri-snRNP and stays associated with the spliceosome during at least part of the activation step.

In addition to homologues of known splicing factors, we identified a previously uncharacterized protein, dMFAP1, which interacts directly with dPrp38 (Fig. 3, E and F). Human MFAP1 has been recovered in a number of spliceosome purifications, but was initially discounted as a contaminant due to its proposed extracellular localization (21, 31). The chicken MFAP1 protein was originally identified as a putative component of the extracellular matrix in a screen for proteins detected by an antiserum raised against a crude microfibril preparation (30). Although we cannot rule out a function for MFAP1 in the extracellular matrix, our data argue that either it has dual functions or its identification as an extracellular protein was based on cross-reactivity of the antiserum with a different protein. Here we show that dMFAP1, like dPrp38, functions in pre-mRNA processing (Fig. 4C and supplemental Fig. S3). Consistent with this, dMFAP1 can be purified in complex with several conserved splicing factors including dPrp38, the U5 snRNP proteins CG8877/U5-220kD/Prp8p, CG3436/U5-40kD/Rsa4p, and CG5931/U5-200kD/Brr2p, and the NTc/Cdc5-Prp19 core component CG6905/Cdc5/Cef1p. The association of dMFAP1 with U5 snRNP proteins and a component of the NTC/Cdc5-Prp19 complex is in agreement with the reported recovery of human MFAP1 in purifications of B, BΔ1U, and B* complexes (15, 16, 18, 20), but not A complexes (56). Thus, dMFAP1/MFAP1 might join the spliceosome simultaneously with dPrp38/Prpf38a, but seems to be more tightly associated with the spliceosome during the activation step. Moreover, MFAP1 was not recovered in spliceosome complexes after the first catalytic step, suggesting that it functions during the activation step (16, 19).

In addition to highly conserved spliceosome components, dMFAP1 also co-purifies with a number of splicing factors that have evolved more recently in metazoans. Unsurprisingly, most of these function in the regulation of alternative splicing. Thus, CG4602/srp54, CG6995/saf-b, and hfp/puf60 were all recovered in an RNAi screen for regulators of alternative splicing, which included 70% of all genes encoding known Drosophila RNA-binding proteins (58). This is consistent with the idea that additional splicing factors have evolved in metazoans to accommodate more complex splice patterns. As expected, very few core splicing components were found to regulate alternative splicing. An interesting exception is CG5931/Brr2p, which we isolated in our dMFAP1 affinity purification (58). dMFAP1 is highly conserved among higher eukaryotes, but not in yeast, indicating that it has evolved more recently. Notably, dMFAP1 does not contain a conserved RNA-binding motif and was not included in the screen carried out by Park and co-workers (58). Whether, dMFAP1 might regulate alternative splicing in higher eukaryotes therefore remains to be determined.

Our in vivo studies of dPrp38 and dMFAP1 revealed that both are essential proteins required for normal growth during development. Consistent with this, clones of mutant tissue with reduced levels of dPrp38 or dMFAP1 exhibit proliferation and growth defects and undergo apoptosis (Fig. 5). A more detailed analysis of the proliferation defects in cell culture shows that cells depleted of dPrp38 or dMFAP1 arrest in G2/M (Figs. 2 and 5K). Moreover, this is paralleled by a substantial reduction in mRNA levels of the mitotic stg/cdc25 phosphatase (Fig. 7G). Thus, the observed G2/M arrest in cells depleted of dPrp38 or dMFAP1 might be the consequence of a defect in stg/cdc25 pre-mRNA processing.

In yeast, a subset of genes with known functions in splicing has also been implicated in cell cycle progression. These include prp3, prp17, prp8, cef1, prp22 (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) (33, 34, 36, 40, 59-61) and prp1, prp2, prp5, prp6, cdc28/prp8, cdc5, and prp12 (Schizosaccharomyces pombe) (35, 37, 39, 62-65). Whereas mutations in some genes encoding splicing factors cause cells to arrest heterogeneously throughout the cell cycle, cef1-13, prp17Δ, and prp22-1 mutants arrest homogenously in G2/M (41). A model has been put forward to explain the variability of the timing of cell cycle arrest, which suggests that some splicing factors are differentially required for efficient splicing of single transcripts or a subset of transcripts (41). Consistent with this idea, removal of a single intron from the α-tubulin encoding the TUB1 gene alleviates both the G2/M arrest and cell division defect observed in the cef1-13 mutant, but only partially rescues the cell division defect observed in prp17Δ and prp22-1 (41, 66). Instead, the G2/M arrest and growth defect in the prp17Δ mutant can be rescued by removal of an intron from the ANC1 gene (67). The molecular basis for this specificity remains unclear.

The range of cell cycle phenotypes observed with different splicing factor mutants in yeast prompted us to study the requirement for various Drosophila splicing factors in cell cycle progression. We analyzed the effect of individual depletions of splicing factors that are predicted to function at various stages of the spliceosome cycle. Depletion of any of those splicing factors caused cells to arrest in G2/M, suggesting that it is a general consequence of interfering with spliceosome activity (Fig. 6). Consistent with this, a genome-wide RNA interference screen in HeLa cells for factors required for mitosis identified a number of genes encoding splicing factors (68). However, we cannot conclude whether the observed G2/M arrest results from of a failure to splice a pre-mRNA encoding a factor that is rate-limiting for entry into mitosis (e.g. stg/cdc25), or whether a defect in splicing activates a mitotic checkpoint that causes cells to arrest in G2. Future research might resolve this issue.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center and the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center for fly stocks, and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for antibodies. We thank Terrence Gilbank, Steve Murray, and Frances Earl for transgenic injections, the LRI FACS lab for help with FACS analysis, Ruth Brain for advice on hairpin cloning, and the Taplin Biological Mass Spectrometry Facility for protein identification. We are grateful to Julien Colombani, Sally Leevers, and Filipe Josué for comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by Cancer Research UK. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1-S3.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: snRNP, small nuclear ribonucleoprotein; qPCR, quantitative PCRs; MFAP1, microfibrillar-associated protein 1; NTc, 19 complex; RNAi, RNA interference; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; GST, glutathione S-transferase; BisTris, 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol; MALDI-TOF, matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight; dsRNA, double-stranded RNA; BrdUrd, bromodeoxyuridine; RT, reverse transcriptase; GFP, green fluorescent protein; PH3, anti-phospho-histone 3.

References

- 1.Jurica, M. S., and Moore, M. J. (2003) Mol. Cell 125 -14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xie, J., Beickman, K., Otte, E., and Rymond, B. C. (1998) EMBO J. 172938 -2946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosbash, M., and Seraphin, B. (1991) Trends Biochem. Sci. 16187 -190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruby, S. W., and Abelson, J. (1988) Science 2421028 -1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zorio, D. A., and Blumenthal, T. (1999) Nature 402835 -838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu, S., Romfo, C. M., Nilsen, T. W., and Green, M. R. (1999) Nature 402832 -835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merendino, L., Guth, S., Bilbao, D., Martinez, C., and Valcarcel, J. (1999) Nature 402838 -841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh, R., Banerjee, H., and Green, M. R. (2000) RNA (Cold Spring Harbor) 6 901-911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brow, D. A. (2002) Annu. Rev. Genet. 36333 -360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madhani, H. D., and Guthrie, C. (1994) Annu. Rev. Genet. 281 -26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Staley, J. P., and Guthrie, C. (1998) Cell 92315 -326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, J. Y., Stands, L., Staley, J. P., Jackups, R. R., Jr., Latus, L. J., and Chang, T. H. (2001) Mol. Cell 7 227-232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raghunathan, P. L., and Guthrie, C. (1998) Curr. Biol. 8847 -855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen, C. H., Tsai, W. Y., Chen, H. R., Wang, C. H., and Cheng, S. C. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276488 -494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Makarova, O. V., Makarov, E. M., Urlaub, H., Will, C. L., Gentzel, M., Wilm, M., and Luhrmann, R. (2004) EMBO J. 232381 -2391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bessonov, S., Anokhina, M., Will, C. L., Urlaub, H., and Luhrmann, R. (2008) Nature 452846 -850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen, Y. I., Maika, S. D., and Stevens, S. W. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 361412 -419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deckert, J., Hartmuth, K., Boehringer, D., Behzadnia, N., Will, C. L., Kastner, B., Stark, H., Urlaub, H., and Luhrmann, R. (2006) Mol. Cell. Biol. 265528 -5543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jurica, M. S., Licklider, L. J., Gygi, S. R., Grigorieff, N., and Moore, M. J. (2002) RNA (Cold Spring Harbor) 8426 -439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Makarov, E. M., Makarova, O. V., Urlaub, H., Gentzel, M., Will, C. L., Wilm, M., and Luhrmann, R. (2002) Science 2982205 -2208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neubauer, G., King, A., Rappsilber, J., Calvio, C., Watson, M., Ajuh, P., Sleeman, J., Lamond, A., and Mann, M. (1998) Nat. Genet. 2046 -50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubin, G. M., and Spradling, A. C. (1982) Science 218348 -353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brand, A. H., and Perrimon, N. (1993) Development 118401 -415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu, T., and Rubin, G. M. (1993) Development 1171223 -1237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blanton, S., Srinivasan, A., and Rymond, B. (1992) Mol. Cell. Biol. 123939 -3947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brand, A. H., Manoukian, A. S., and Perrimon, N. (1994) Methods Cell Biol. 44 635-654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diaz, B., and Moreno, E. (2005) Exp. Cell Res. 306317 -322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu, J., Mayeda, A., and Krainer, A. R. (2001) Mol. Cell 81351 -1361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cho, S. Y., Shin, E. S., Park, P. J., Shin, D. W., Chang, H. K., Kim, D., Lee, H. H., Lee, J. H., Kim, S. H., Song, M. J., Chang, I. S., Lee, O. S., and Lee, T. R. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 2822456 -2465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horrigan, S. K., Rich, C. B., Streeten, B. W., Li, Z. Y., and Foster, J. A. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 26710087 -10095 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neubauer, G. (2005) Methods Enzymol. 405236 -263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pignoni, F., Hu, B., and Zipursky, S. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 949220 -9225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boger-Nadjar, E., Vaisman, N., Ben-Yehuda, S., Kassir, Y., and Kupiec, M. (1998) Mol. Gen. Genet. 260232 -241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hwang, L. H., and Murray, A. W. (1997) Mol. Biol. Cell 81877 -1887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lundgren, K., Allan, S., Urushiyama, S., Tani, T., Ohshima, Y., Frendewey, D., and Beach, D. (1996) Mol. Biol. Cell 71083 -1094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohi, R., Feoktistova, A., McCann, S., Valentine, V., Look, A. T., Lipsick, J. S., and Gould, K. L. (1998) Mol. Cell. Biol. 184097 -4108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Potashkin, J., Kim, D., Fons, M., Humphrey, T., and Frendewey, D. (1998) Curr. Genet. 34 153-163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stevens, S. W., and Abelson, J. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 967226 -7231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Urushiyama, S., Tani, T., and Ohshima, Y. (1997) Genetics 147101 -115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vaisman, N., Tsouladze, A., Robzyk, K., Ben-Yehuda, S., Kupiec, M., and Kassir, Y. (1995) Mol. Gen. Genet. 247123 -136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burns, C., Ohi, R., Mehta, S., O'Toole, E., Winey, M., Clark, T., Sugnet, C., Ares, M., and Gould, K. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22801 -815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bernstein, H. S., and Coughlin, S. R. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 2734666 -4671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li, X., Wang, J., and Manley, J. L. (2005) Genes Dev. 192705 -2714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pacheco, T. R., Moita, L. F., Gomes, A. Q., Hacohen, N., and Carmo-Fonseca, M. (2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 174187 -4199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perriman, R., and Ares, M. (2000) Genes Dev. 1497 -107 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chan, S. P., and Cheng, S. C. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 28031190 -31199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chan, S. P., Kao, D. I., Tsai, W. Y., and Cheng, S. C. (2003) Science 302279 -282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsai, W., Chow, Y., Chen, H., Huang, K., Hong, R., Jan, S., Kuo, N., Tsao, T., Chen, C., and Cheng, S. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 2749455 -9462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.James, S., Turner, W., and Schwer, B. (2002) RNA (Cold Spring Harbor) 81068 -1077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schneider, S., Hotz, H., and Schwer, B. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 27715452 -15458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Umen, J., and Guthrie, C. (1995) RNA (Cold Spring Harbor) 1584 -597 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang, Y., and Guthrie, C. (1998) RNA (Cold Spring Harbor) 41216 -1229 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schneider, S., Campodonico, E., and Schwer, B. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 2798617 -8626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Edgar, B. A., and O'Farrell, P. H. (1989) Cell 57177 -187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bousquet-Antonelli, C., Presutti, C., and Tollervey, D. (2000) Cell 102765 -775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hartmuth, K., Urlaub, H., Vornlocher, H. P., Will, C. L., Gentzel, M., Wilm, M., and Luhrmann, R. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 9916719 -16724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Urlaub, H., Hartmuth, K., and Luhrmann, R. (2002) Methods 26170 -181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Park, J. W., Parisky, K., Celotto, A. M., Reenan, R. A., and Graveley, B. R. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 10115974 -15979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hartwell, L. H., Mortimer, R. K., Culotti, J., and Culotti, M. (1973) Genetics 74 267-286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Johnston, L. H., and Thomas, A. P. (1982) Mol. Gen. Genet. 186439 -444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shea, J. E., Toyn, J. H., and Johnston, L. H. (1994) Nucleic Acids Res. 225555 -5564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Habara, Y., Urushiyama, S., Shibuya, T., Ohshima, Y., and Tani, T. (2001) RNA (Cold Spring Harbor) 7 671-681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nurse, P., Thuriaux, P., and Nasmyth, K. (1976) Mol. Gen. Genet. 146167 -178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ohi, R., McCollum, D., Hirani, B., Den Haese, G. J., Zhang, X., Burke, J. D., Turner, K., and Gould, K. L. (1994) EMBO J. 13471 -483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Takahashi, K., Yamada, H., and Yanagida, M. (1994) Mol. Biol. Cell 51145 -1158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chawla, G., Sapra, A., Surana, U., and Vijayraghavan, U. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 312333 -2343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dahan, O., and Kupiec, M. (2004) Nucleic Acids Res. 322529 -2540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kittler, R., Putz, G., Pelletier, L., Poser, I., Heninger, A. K., Drechsel, D., Fischer, S., Konstantinova, I., Habermann, B., Grabner, H., Yaspo, M. L., Himmelbauer, H., Korn, B., Neugebauer, K., Pisabarro, M. T., and Buchholz, F. (2004) Nature 4321036 -1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.