Abstract

Most errors that arise during DNA replication can be corrected by DNA polymerase proofreading or by post-replication mismatch repair (MMR). Inactivation of both mutation-avoidance systems results in extremely high mutability that can lead to error catastrophe1,2. High mutability and the likelihood of cancer can be caused by mutations and epigenetic changes that reduce MMR3,4. Hypermutability can also be caused by external factors that directly inhibit MMR. Identifying such factors has important implications for understanding the role of the environment in genome stability. We found that chronic exposure of yeast to environmentally relevant concentrations of cadmium, a known human carcinogen5, can result in extreme hypermutability. The mutation specificity along with responses in proofreading-deficient and MMR-deficient mutants indicate that cadmium reduces the capacity for MMR of small misalignments and base-base mismatches. In extracts of human cells, cadmium inhibited at least one step leading to mismatch removal. Together, our data show that a high level of genetic instability can result from environmental impediment of a mutation-avoidance system.

To identify factors that might influence MMR, we used long homonucleotide runs in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae as reporters of altered MMR capacity. Long homonucleotide runs and other microsatellites are at-risk motifs in MMR-deficient cells6. These motifs are sensitive reporters for low levels of MMR7-10 and for MMR-deficient cancers3,4,11 because the correction of frequently occurring spontaneous frameshift errors in long homonucleotide runs and microsatellites is accomplished primarily by MMR. Frameshifts in shorter runs and base substitutions are corrected by proofreading as well as by MMR8,12.

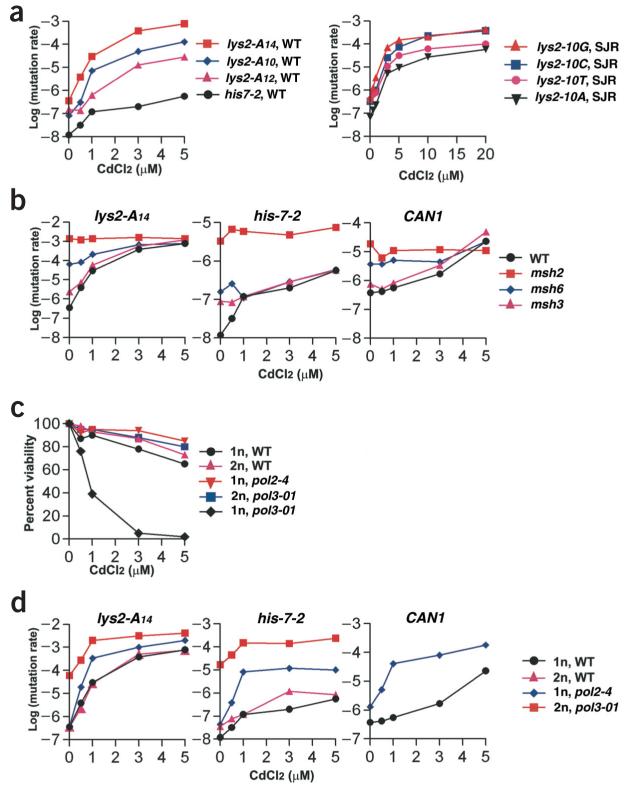

We chose to test divalent cations as potential inhibitors of MMR because they can affect many enzymatic reactions. Several divalent cations that are also carcinogens can decrease the fidelity of DNA synthesis in vitro13. Thus, it seemed possible that these cations could also target mutation-avoidance systems in vivo. We found that chronic exposure to low, non-lethal doses of cadmium (CdCl2) caused a substantial increase in mutability (as much as 2,000-fold) of long homonucleotide runs in the yeast gene LYS2 (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 1 online). The strong mutagenic effect was specific to cadmium in that mutagenesis was not detected with other divalent cations or with agents that cause oxidative damage at comparable survival levels (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Table 2 online). In contrast with its strong mutagenic effect, cadmium caused only a small increase in interchromosomal recombination (about 3-fold to 4-fold) and no increase in intrachromosomal recombination (Supplementary Table 3 online), which suggests that mutagenesis does not occur through DNA damage.

Figure 1.

The impact of CdCl2 on mutation rates and viability in yeast. Yeast strains are described in Supplementary Methods online. Rates, frequencies and 95% confidence intervals are provided in Supplementary Table 1 online. Frameshift mutation reporters with homonucleotide runs in the CG379 background included lys2-A14 (A14 run that reverts by -1 frameshifts), lys2-A12 (A12 run that reverts by +1 frameshifts), lys2-A10 (A10 run that reverts by -1 frameshifts) and his7-2 (A7 run that reverts by +1 frameshifts). Homonucleotide run reporters containing 10 bases of A, T, G or C at the same position in LYS2 that revert by -1 frameshifts were also used in the SJR background28. The CAN1 forward mutations arise by frameshifts, base substitutions and gross rearrangements. Yeast strains and mutation reporters are indicated on the corresponding panels. (a) Mutagenesis in homonucleotide runs of wild-type strains. WT, wild-type strains of CG379 background; SJR, wild-type strains of SJR background. The SJR strains were more resistant to killing by cadmium and required higher doses to reach a mutagenesis plateau. The rates of his7-2 reversion were determined in the wild-type strain carrying lys2-A14. They were similar to rates of mutation in the his7-2 reporter determined in the isogenic wild-type strains carrying lys2-A12 and lys2-A10 (Supplementary Table 1 online). (b) Mutagenesis in MMR-deficient strains. Mutation rates for wild-type lys2-A14 are the same as in a. (c) Viability of wild-type and proofreading-deficient strains. All strains are in CG379 background. 1n, WT indicates a wild-type strain with lys2-A14 reporter, which was used to create all other strains shown on this panel. 1n, haploid; 2n, diploid. (d) Mutagenesis in proofreading-deficient haploid (1n) and diploid (2n) strains. Strains are the same as in c. Only pol3-01 diploids, but not haploids, were used to avoid the lethal effect of cadmium. Because can1 mutations are recessive, they cannot be assessed in pol3-01 diploids; therefore, can1 rates were determined only for the haploid Pol ε proofreading-deficient mutant pol2-4. The data for wild-type haploid strains are the same as in panels a and b.

In addition to causing nuclear mutations, chronic exposure to non-lethal concentrations of cadmium (3 μM and 5 μM) also induced petite mutants (mutants that are unable to grow on a non-fermentable carbon source owing to loss of mitochondrial function; see Supplementary Tables 1 and 3 online). Although alteration of mitochondrial function by metal ions could result in reactive oxygen species, mitochondrial loss and even nuclear damage in yeast (ref. 14 and refs. therein), we found comparable levels of cadmium mutagenesis in homonucleotide run reporters in both the wild-type and petite strains (generated by cadmium or by the DNA-intercalating agent ethidium bromide; data not shown). Non-specific changes in gene expression are also an unlikely source of the high mutation frequencies. Although cadmium can alter expression of many proteins in yeast (ref. 15 and refs. therein), deletion of genes associated with cadmium stress, such as MET4, YAP1 and YAP2, did not alter cadmium mutagenesis in any of the reporters in this study (data not shown).

Because the stability of long homonucleotide runs is extremely sensitive to reduction in MMR capacity, we proposed that MMR itself is a target of cadmium. Mutations that completely eliminate DNA-damage repair pathways have never been reported to cause such strong mutator effects as are caused by MMR defects in long homonucleotide runs and other microsatellites3. Our experiments with isogenic strains that lack base-excision repair (rad27-Δ16), nucleotide excision repair (rad1-Δ, data not shown) and double-strand break repair (rad52-Δ, data not shown) identified only moderate mutator effects as compared with those caused by defects in MMR. The hypothesis about MMR inhibition was supported by a comparison of the effects of cadmium on frameshift mutagenesis in homonucleotide runs of various sizes and nucleotide content. Cadmium was a strong mutagen for all runs, leading to mutation rates as much as 2,000 times higher (Fig. 1a). At the highest concentrations, cadmium-induced mutation rates were 20-50% of those observed in parallel experiments with msh2Δ strains, which completely lack MMR. There was a notable similarity between cadmium-induced mutation rates and mutation rates in MMR-null strains. In all cases, the cadmium-induced rates (within a group of isogenic strains) were higher for the homonucleotide runs that showed higher mutation rates in the MMR-null background (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of cadmium-induced mutation rates in MMR-proficient yeast versus spontaneous mutation rates in MMR-null mutants.

| Mutation rate in reporter × 10-4 (strain background) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strains compared |

CAN1 (CG379) |

his7-2 (CG379) |

lys2-A14 (CG379) |

lys2-A10 (CG379) |

lys2-A12 (CG379) |

lys2-10G (SJR) |

lys2-10C (SJR) |

lys2-10T (SJR) |

lys2-10A (SJR) |

| Wild-type on Cd (MMR-null) |

NA | 0.006 (0.03) |

7.8 (14) |

1.3 (3.1) |

0.3 (0.8) |

4.3 (6.6) |

3.8 (6.8) |

1.0 (1.9) |

0.6 (0.7) |

|

pol2-4 on Cd (pol2-4 MMR-null) |

1.8 (1.1) |

0.1 (0.1) |

20 (31) |

ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

|

pol3-01 on Cd (pol3-01 MMR-null) |

NA | 2.4 (2.8) |

42 (34) |

ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

Presented are the rates of mutation induced by 5 μM CdCl2 in strains from the CG379 background and by 20 μM CdCl2 in strains from the SJR background. pol3-01 strains were diploids; all others were haploids. pms1 is a MMR-null defect that was combined with pol2-4 for his7-2 mutation rates; MMR-null defects for all other spontaneous rates determined in single and double mutants were msh2. Spontaneous rates in MMR-null (msh2) single mutants for lys2-A14 and his7-2 are taken from Supplementary Table 1 online and were determined in parallel with measurements for other strains; spontaneous rates for lys2-A12, lys2-A10 in MMR-null (msh2) mutants are from ref. 8; spontaneous rates for lys2 alleles in SJR MMR-null (msh2) strains are from ref. 28. Spontaneous rates in pol3-01 MMR-null (msh2) are from ref. 9 and in pol3-01 pms1 are from ref. 18. NA, not applicable; ND, not determined.

If cadmium inhibits MMR such that 20-50% of spontaneous mismatches are left unrepaired, then the high mutation rates characteristic of the MMR-null mutants would not be increased by exposure to cadmium. Consistent with this, the mutation rates in the msh2Δ mutant for A14 (lys2-A14) and A7 (his7-2) homonucleotide runs and the rate of forward mutations in the gene CAN1 were not changed by exposure to cadmium (Fig. 1b). We also measured mutation rates in msh6Δ and msh3Δ mutants that are deficient in the MutSα and MutSβ mismatch recognition complexes, respectively. These complexes have partially overlapping function, so that either mutant has a modest mutator phenotype7. Exposure to 3 μM and 5 μM cadmium increased mutation rates in msh6Δ and msh3Δ mutants to the same levels found in treated wild-type cells (Fig. 1b). This suggests that cadmium inhibits both Msh2/Msh6- and Msh2/Msh3-dependent MMR. Using a semi-quantitative test, we also examined cadmium mutagenesis in strains pms1Δ and mlh1Δ, which are completely defective in the second step of mismatch recognition3. The results for mlh1Δ and pms1Δ were comparable to those observed for the msh2 deletion (data not shown).

DNA polymerases Pol δ and Pol ε, which are involved in replicating chromosomal DNA, have intrinsic 3′-to-5′ proofreading exonuclease activity17. Since a defect in proofreading of either polymerase combined with a MMR defect results in an extremely high mutation rate2,9,18, we examined the effects of cadmium on proofreading-deficient Pol δ (pol3-01) and Pol ε (pol2-4) strains. Cadmium was lethal to pol3-01 haploids but not to pol2-4 (a much weaker mutator) or wild-type haploids (Fig. 1c). Isogenic pol3-01 diploids, however, were resistant to cadmium. The lethality caused by cadmium in the Pol δ proofreading-deficient mutant is similar to the lethal effects observed when MMR-null mutations pms1 or msh2 were introduced into pol3-01 haploids. Double-mutant haploids were inviable owing to the catastrophic accumulation of errors, whereas double-mutant diploids were viable because lethal mutations are generally recessive2,9.

Further support for cadmium inhibition of MMR came from examining mutation rates in proofreading-deficient strains (Fig. 1d). As expected for a factor that inhibits MMR, cadmium caused a strong increase of mutation rates in proofreading-deficient mutants. This is similar to the synergistic (that is, greater than additive) mutator effects caused by combination of mutated proofreading and MMR alleles. The spontaneous mutation rates in double mutants9,18 were comparable to the cadmium-induced mutation rates in single proofreading-deficient mutants (Table 1). As expected with synergy, cadmium-induced mutation rates in the pol3-01 and pol2-4 mutants were 2-50 times greater than the sum of mutation rates induced by cadmium in the wild-type strain plus the spontaneous mutation rate in the corresponding proofreading mutant.

The MMR system efficiently repairs not only misalignments that lead to frameshift mutations but also base-base mismatches, thus preventing base substitutions3. We determined the rates of spontaneous and cadmium-induced frameshifts and base substitutions at the yeast gene CAN1 in the wild type and in a strain deficient in Pol ε proofreading (pol2-4; Table 2). (Note that the pol2-4 strain has a proofreading-proficient Pol δ.) As expected for MMR inhibition, the rate of frameshift mutation in both strains increased more than the rate of base substitutions, as frameshifts in longer runs are inefficiently prevented by proofreading8,12. Notably, exposure to cadmium strongly increased not only the rate of frameshift mutation but also the rate of base substitutions, indicating that repair of all kinds of mismatches was inhibited.

Table 2. Induction of frameshift and base substitution mutations in CAN1 by cadmium.

| Rate × 10-7 (fraction) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | pol2-4 | |||

| Type of event | 0 μM | 5 μM | 0 μM | 5 μM |

| Base substitutions | 3.0 (16/20) | 48 (5/24) | 10 (14/18) | 840 (14/30) |

| Frameshifts | 0.4 (2/20) | 182 (19/24) | 2.2 (3/18) | 960 (16/30) |

| Total | 3.8 | 230 | 13 | 1,800 |

The nature of each mutation was determined by sequencing the entire CAN1 open reading frame. Most mutations were single-nucleotide frameshifts and base substitutions. There were also two larger deletions and one complex mutation not included into this table. Detailed mutation spectra are presented in Supplementary Table 4 online. The data for 0 μM CdCl2 are from ref. 29. Other total mutation rates are from Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1 online. Fractions of mutation events in the total spectrum were used to calculate mutation rates for each type of event as a fraction of total rate. All differences in mutation rates and mutation spectra mentioned in the text are statistically significant at P < 0.05, by comparing confidence intervals, by χ2 test or by Mann-Whitney test.

Based on the strong similarity between cadmium mutagenesis and the mutator effects of MMR-null alleles, we conclude that cadmium is a new kind of mutagen that acts by inhibiting the MMR system rather than through DNA damage.

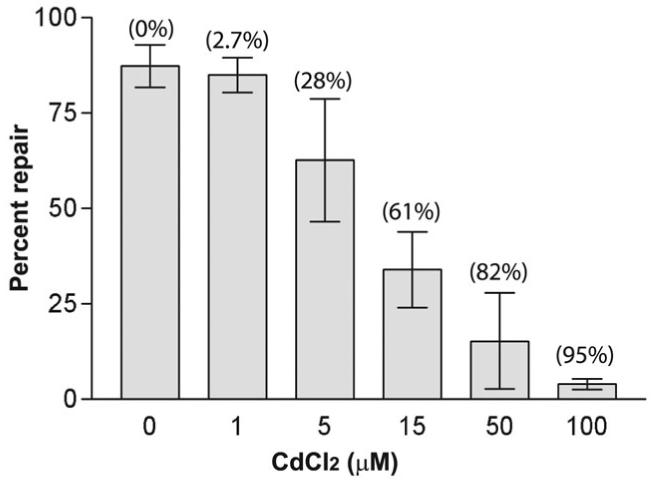

To directly assess the impact of cadmium on human MMR activity, we examined MMR in a human cell extract that can efficiently repair a heteroduplex containing a one-base loop (Fig. 2). Cadmium inhibited the MMR activity in a concentration-dependent manner, with a decrease detectable at 5 μM CdCl2 (P = 0.05 by Mann-Whitney test). The average decrease of 28% in the in vitro repair efficiency caused by exposure to 5 μM CdCl2 was similar to the 20-50% of mismatches that were not repaired at comparable concentrations in yeast. The small fraction of unrepaired mismatches (about 2%) that can be detected with the sensitive mutation reporter lys2-A14 in yeast at a concentration of 1 μM CdCl2 was undetectable by the in vitro assay, because even in the absence of cadmium, MMR in the extract was incomplete. The nature of the in vitro assay19 indicates that the loss of MMR activity must be due to inhibition of one or more steps preceding or including excision. The inhibition was specific to MMR, as cadmium did not interfere with SV40 origin-dependent DNA replication in extracts (data not shown). We did not detect inhibition of MMR with high (50 μM) concentrations of two other divalent cations, cobalt and manganese (data not shown). Further studies are needed to establish if ions other than cadmium can inhibit in vitro or in vivo MMR.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of in vitro human strand-specific DNA MMR in a repair-proficient cell extract by cadmium. Data are the average of three independent experiments. Error bars represent standard deviation. The average percent reduction in repair efficiency, taking the amount of repair in the absence of cadmium as 100%, is shown in parentheses above each bar.

We suggest that cadmium targets proteins that are directly or indirectly involved in MMR in yeast cells and in human cell extracts. Alteration of protein function has been suggested to explain the toxic, mutagenic and carcinogenic effects of cadmium20-22. For example, cadmium might bind to cysteine-containing motifs in proteins, such as zinc fingers. Cadmium is also known to bind to calcium channels and calcium-containing proteins. We are currently investigating the possible MMR targets.

The strong mutagenic action of cadmium was observed at concentrations comparable to those found in the environment and at levels that can accumulate in the human body5. For example, the prostate of healthy unexposed humans accumulates cadmium to concentrations of 12-28 μM and human lungs accumulate cadmium to concentrations of 0.9-6 μM (higher in tobacco smokers23). Cadmium has only been confirmed as a lung carcinogen but it may also cause prostate cancer5,20. The primary type of cancer caused by genetic defects in MMR is colorectal cancer4. There have been some reports identifying a low level of microsatellite instability associated with cancers of the lung11,24 and prostate25. Further studies are needed to identify conditions and cell types in which cadmium could inhibit human MMR in vivo (see Supplementary Note online). Because the level of MMR is an important risk factor in various cancers, even moderate inhibition of MMR has implications for human health. Variations in levels of MMR, possibly due to polymorphisms or differences in MMR levels between tissues or individual cells, could influence the impact of cadmium.

As reduction in MMR has been proposed to facilitate accumulation of adaptive mutations26, the presence of cadmium in the environment could alter the evolution rate of species with a cadmium-sensitive MMR system. Our findings with cadmium suggest that additional environmental factors could cause genome instability by modulating key DNA metabolic system(s) rather than by damaging DNA. Based on the approaches used in the current study, sensitized systems that include a combination of at-risk motifs and the ability to detect synergistic interactions will provide opportunities to identify other factors that affect the integrity of DNA metabolism.

METHODS

Mutation frequencies, rates and viability measurements in yeast

We plated 1:1,000 dilutions of concentrated (2-4 × 107 cells ml-1) yeast suspensions on synthetic complete media containing different concentrations of CdCl2 by a 121-prong device27. We also plated concentrated suspension onto selective media to avoid using starting material with a high frequency of preexisting mutants. Each prong transferred approximately 1 μl so that about 2-4 × 103 cells from the concentrated suspension and about 2-3 cells from the diluted suspension were transferred. The transferred volume is very reproducible as determined from reproducible numbers of cells transferred by independent platings27. We incubated the plates at 30 °C for 4 d. The patches from the individual prongs of the concentrated suspension contained about 5 × 106 cells and thus could be considered a culture grown from the relatively small number of cells. Cells from individual prongs were carefully scraped and suspended in water. We plated appropriate dilutions onto selective medium and synthetic complete medium to determine mutant frequencies. After counting colonies on selective medium, we replica-plated them to yeast extract/peptone/dextrose and yeast extract/peptone/Glycerol media to determine the frequency of mutants that had lost mitochondrial function (petite mutants). Because the total number of cells plated from diluted medium was approximately 300-400 per plate, each dividing cell was forming a distinct single colony. We used the ratio of colony numbers grown from diluted suspension on plates with the drug to the number of colonies on unexposed plates as a measure of the effect of exposure on colony-forming ability (‘viability’ in Supplementary Tables 1, 2 and 3 online). We calculated median mutation rates and petite frequencies ands average viability from measurements in 6-16 individual cultures. We calculated rates and 95% confidence intervals for the median as described8,9. We chose to calculate mutation rates to compare results with published studies on the same or isogenic strains. It should be noted, however, that mutation rates are calculated with the assumption that the rate of mutation is constant at all stages and for all cells in the culture, which may not hold during chronic exposure of yeast on solid media. Therefore, we also present medians and 95% confidence intervals for the frequencies of mutants. The conclusions of this paper concerning mutagenic effects are valid regardless of whether frequencies or rates are used for comparison.

MMR activity in human cell extract

We assayed strand-specific DNA MMR activity in a repair-proficient cell extract as described (ref. 19 and refs. therein). The substrate contained one extra A in the (+) strand at position 91-94 and a 5′ nick in the (-) strand at the Bsu36I site (position +276). We added CdCl2 to the extract at the indicated concentrations and pre-incubated the mixture at 0 °C for 10 min before adding reaction buffer with the DNA substrate. We assessed repair activity at 37 °C.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. Jinks-Robertson for yeast strains; J. Sterling, J. Choi and G. Horner for help in conducting experiments; and J. Drake, B. Van Houten, M. Waalkes, T. Petes and J. Wachsman for critically reading the manuscript and for advice.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Schaaper RM. Base selection, proofreading, and mismatch repair during DNA replication in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:23762–23765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morrison A, Johnston AL, Johnston LH, Sugino A. Pathway correcting DNA replication errors in S. cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1993;12:1467–1473. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05790.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harfe BD, Jinks-Robertson S. DNA mismatch repair and genetic instability. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2000;34:359–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peltomaki P. Deficient DNA mismatch repair: a common etiologic factor for colon cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:735–740. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.7.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. IARC; Lyon, France: 1993. Cadmium; pp. 119–237. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gordenin DA, Resnick MA. Yeast ARMs (DNA at-risk motifs) can reveal sources of genome instability. Mutat. Res. 1998;400:45–58. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(98)00047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marsischky GT, Filosi N, Kane MF, Kolodner R. Redundancy of Saccharomyces cerevisiae MSH3 and MSH6 in MSH2-dependent mismatch repair. Genes Dev. 1996;10:407–420. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tran HT, Keen JD, Kricker M, Resnick MA, Gordenin DA. Hypermutability of homonucleotide runs in mismatch repair and DNA polymerase proofreading yeast mutants. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;17:2859–2865. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tran HT, Gordenin DA, Resnick MA. The 3′→5′ exonucleases of DNA polymerase δ and ε and the 5′→3′ exonuclease Exo1 have major roles in postreplication mutation avoidance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:2000–2007. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drotschmann K, Clark AB, Kunkel TA. Mutator phenotypes of common polymorphisms and missense mutations in MSH2. Curr. Biol. 1999;9:907–910. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80396-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coleman WB, Tsongalis GJ. The role of genomic instability in human carcinogenesis. Anticancer Res. 1999;19:4645–4664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kroutil LC, Register K, Bebenek K, Kunkel TA. Exonucleolytic proofreading during replication of repetitive DNA. Biochemistry. 1996;35:1046–1053. doi: 10.1021/bi952178h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sirover MA, Loeb LA. Infidelity of DNA synthesis in vitro: screening for potential metal mutagens or carcinogens. Science. 1976;194:1434–1436. doi: 10.1126/science.1006310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karthikeyan G, Lewis LK, Resnick MA. The mitochondrial protein frataxin prevents nuclear damage. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002;11:1351–1362. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.11.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fauchon M, et al. Sulfur sparing in the yeast proteome in response to sulfur demand. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:713–723. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00500-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gary R, et al. A novel role in DNA metabolism for the binding of Fen1/Rad27 to PCNA and implications for genetic risk. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:5373–5382. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hubscher U, Maga G, Spadari S. Eukaryotic DNA polymerases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2002;71:133–163. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.090501.150041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morrison A, Sugino A. The 3′→5′ exonucleases of both DNA polymerase δ and ε participate in correcting errors of DNA replication in S. cerevisiae. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1994;242:289–296. doi: 10.1007/BF00280418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Umar A, et al. Requirement for PCNA in DNA mismatch repair at a step preceding DNA resynthesis. Cell. 1996;87:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81323-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waalkes MP, Misra RR. Cadmium carcinogenicity and genotoxicity. In: Chang LW, editor. Toxicology of Metals. CRC; Boca Raton: 1996. pp. 231–243. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beyersmann D, Hechtenberg S. Cadmium, gene regulation, and cellular signalling in mammalian cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1997;144:247–261. doi: 10.1006/taap.1997.8125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartwig A. Zinc finger proteins as potential targets for toxic metal ions: differential effects on structure and function. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2001;3:625–634. doi: 10.1089/15230860152542970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elinder CG. Normal values for cadmium in human tissues, blood, and urine in different countries. In: Friberg L, Elinder CG, Kjellstrom T, Nordberg GF, editors. Cadmium and Health: A Toxicological and Epidemiological Appraisal. CRC; Boca Raton: 1985. pp. 81–102. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mao L, et al. Microsatellite alterations as clonal markers for the detection of human cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:9871–9875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leach FS. Microsatellite instability and prostate cancer: clinical and pathological implications. Curr. Opin. Urol. 2002;12:407–411. doi: 10.1097/00042307-200209000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giraud A, et al. Costs and benefits of high mutation rates: adaptive evolution of bacteria in the mouse gut. Science. 2001;291:2606–2608. doi: 10.1126/science.1056421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khromov-Borisov NN, Saffi J, Henriques JAP. Perfect order plating: principle and applications. Technical Tips Online. 2002;1:t02638. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harfe BD, Jinks-Robertson S. Sequence composition and context effects on the generation and repair of frameshift intermediates in mononucleotide runs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2000;156:571–578. doi: 10.1093/genetics/156.2.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jin YH, et al. The 3→5′ exonuclease of DNA polymerase δ can substitute for the 5′ flap endonuclease Rad27/Fen1 in processing Okazaki fragments and preventing genome instability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:5122–5127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091095198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.