Abstract

The mechanism of pore formation of lytic peptides, such as melittin from bee venom, is thought to involve binding to the membrane surface, followed by insertion at threshold levels of bound peptide. We show that in membranes composed of zwitterionic lipids, i.e. phosphatidylcholine, melittin not only forms pores but also inhibits pore formation. We propose that these two modes of action are the result of two competing reactions: direct insertion into the membrane and binding parallel to the membrane surface. The direct insertion of melittin leads to pore formation, whereas the parallel conformation is inactive and prevents other melittin molecules from inserting, hence preventing pore formation.

Lytic or antimicrobial peptides are small proteins (12–50 amino acids) that affect cells by disrupting the barrier function of lipid membranes (1). There is much interest in these peptides because of their potential pharmaceutical applications, e.g. as cancer drugs and antibiotics (2). Because of their small size and high stability, they can be obtained in large quantities. Of all lytic peptides, the 26-residue melittin is the best studied to date (for review see Ref. 3). Melittin is the major constituent of the venom of the European honeybee Apis mellifera. Melittin has been reported to have anticancer effects and is already being used to treat pain and arthritis in Asia (4).

Melittin can bind within milliseconds to lipid membranes and adopts an amphipatic α-helical conformation, oriented either parallel or perpendicular to the plane of the membrane. The perpendicular conformation is embedded in the membrane and is needed for pore formation, whereas the parallel conformation is inactive (5–10). These observations led to the proposal of a two-step model for pore formation, where melittin at low concentrations binds parallel to the membrane (Fig. 1A, step 1) and at higher concentrations shifts toward the perpendicular orientation (step 2), causing pore formation (10–12). The transition from parallel to perpendicular is still poorly understood, especially because the cationic (5+ at neutral pH) melittin interacts strongly with the lipid headgroups (partitioning coefficient of 104–105 m–1 for phosphatidylcholine (PC)2 (12–17)), and the energy of the transition must be very high (3, 11). Based on the high affinity of melittin for PC headgroups, it has been widely accepted that the concentration of melittin needed for pore formation is not dependent on the absolute melittin concentration but rather on the ratio of melittin to lipid molecules. However, this important implication has never been directly tested by varying the lipid concentration and determining the fractions of bound and free melittin. In this study we analyzed the lipid concentration dependence of melittin action and studied the reversibility of melittin binding, thereby resolving pore formation from binding events.

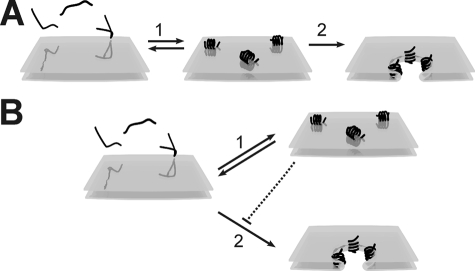

FIGURE 1.

Models of pore formation by melittin in membranes composed of zwitterionic PC lipids. A, existing model. Step 1: At low concentrations, melittin (∼) binds to the membrane and forms an amphipatic α-helix oriented parallel to the membrane. Step 2: If the melittin concentration reaches above a certain threshold, melittin inserts in the membrane and the orientation shifts to largely perpendicular, causing pore formation. B, new model. Melittin (∼) binds and forms an amphipatic α-helix and can be oriented either parallel (step 1) or perpendicular (step 2) to the plane of the membrane. The perpendicular orientation leads to membrane insertion and pore formation, whereas the parallel orientation is inactive and prevents other melittin molecules from forming pores, hence protecting the membrane (dotted line).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Melittin was purchased from Genscript (Piscataway, NJ), and lipids were from Avanti Polar Lipids (Albaster, AL). Liposomes (200 ± 50 nm in diameter) were prepared by rehydration of a dried lipid film, followed by flash freezing (liquid nitrogen) and thawing five times at 50 °C and subsequent extrusion through polycarbonate filters or sonication, as described (18, 19). For the calcein dequenching and the fluorescence-burst assays, the liposomes were separated from the free fluorophores by size exclusion chromatography (Sephadex G-50, Sigma-Aldrich) (19) and centrifugation (18), respectively.

The calcein dequenching assay was performed as described (19), with the liposomes loaded with 100 mm calcein in 10 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.0. The external medium was composed of 10 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.0, plus 150 mm NaCl. The 100% level of leakage was determined using 0.03% (w/v) of the detergent Triton X-100. The dual-color fluorescence-burst assay was performed as described (18, 20), with the only change that all experiments were performed in 10 mm potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7, supplemented with 150 mm NaCl to allow for direct comparison with the calcein dequenching experiments. The liposomes were labeled with the fluorescent lipid analog DiO (Invitrogen) and contained 5 μm glutathione labeled with Alexa fluor 633 (Invitrogen) as a leakage-marker (18, 20).

Far-UV CD was recorded on an Aviv 62A DS CD spectrometer (Aviv Biomedical, Lakewood, NJ). The temperature was kept at 25 °C, and the sample compartment was continuously flushed with nitrogen gas. A correction was made for the background signal using a reference solution without the protein.

RESULTS

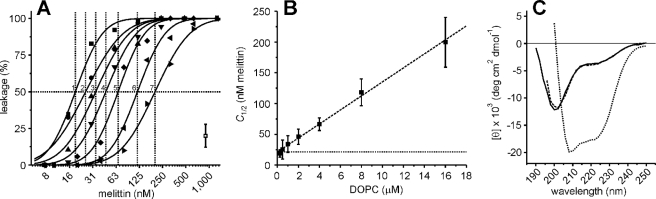

We measured the melittin-induced pore formation as a function of the lipid concentration using the calcein dequenching assay (19, 21), a fluorescence-burst assay (18, 20), and liposomes composed of pure DOPC (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine). The amount of melittin needed for calcein leakage was clearly dependent on the concentration of lipids (Fig. 2A). For each of the lipid concentrations, the concentration where half of the calcein leaked from the liposomes (C1/2) was obtained by fitting the melittin titration curves with a cumulative log normal distribution (18). These C1/2 values were linearly related to the lipid concentration, and from a fit with a linear regression, a slope of 11 nm melittin/μm lipid and an offset of 21 nm melittin were obtained (Fig. 2B). We thus concluded that leakage is not only dependent on the melittin/lipid molecule ratio but also on the absolute concentration of melittin. The offset of the linear regression analysis indicates that melittin binding to the membrane is reversible (Fig. 1A, step 1). From the slope of the regression analysis, about 1 melittin per 90 lipid molecules (45 per monolayer) was needed for leakage of the 623 Da calcein (λex = 485 nm, λem = 520 nm). This value is in agreement with literature values but strongly depends on the precise experimental conditions, such as pH and ionic strength of the buffer, and the lipid composition (3, 14, 16–18, 22). Under our experimental conditions (10 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7, 150 mm NaCl, 8 nm–44 μm melittin), the melittin in solution was predominantly present in an unstructured, most likely monomeric, form (Fig. 2C) (23–25). The results presented here can be interpreted in terms of the two-step model, where pore formation (Fig. 1A, step 2) leads to a decrease in the concentration of free melittin until below the critical threshold concentration needed for leakage. We performed experiments to establish whether melittin indeed interacted with the liposomes until no further leakage occurred.

FIGURE 2.

Calcein dequenching as a function of lipid (liposome) concentration. A, calcein dequenching from liposomes composed of pure DOPC was measured for various melittin concentrations. The final lipid concentrations were 0.25 μm (1, ▪), 0.5 μm (2, ○), 1 μm (3, ▴), 2 μm (4, ▾), 4 μm (5, ♦), 8 μm (6, ◂), and 16 μm (7, ▸). Leakage took place within 5 min and was stable for over 24 h. The typical error from at least two independent experiments is indicated. The solid lines present fits with a cumulative log normal distribution, and these allowed us to estimate the concentration of melittin where 50% of the calcein leaked out (C1/2, dotted lines) (18). B, the C1/2 values for the various lipid concentrations obtained from A are shown. The dashed line shows the result of the linear regression analysis, with a slope of 11 nm melittin/μm lipids and an offset of 21 nm (dotted line). C, CD spectra of melittin are shown. The mean residue ellipticity [θ] is plotted as a function of the wavelength for 44 μm melittin in 10 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7, plus various concentrations of NaCl. Melittin is in the unfolded conformation in the absence of NaCl (solid line); 2.5 m NaCl stabilizes the α-helical conformation of melittin (dotted line) (25). At the NaCl concentration used in this study (150 mm, dashed line), melittin is predominantly in the unfolded conformation.

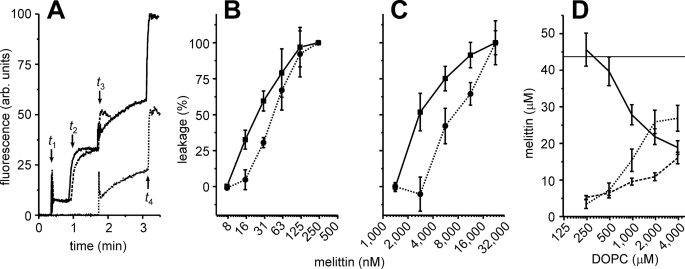

A two-step calcein dequenching experiment was devised where first melittin was added to liposomes and the calcein leakage was measured (Fig. 3A). A second batch of intact liposomes was then added to the solution, and the calcein leakage of this second batch was measured. If the melittin free in solution was depleted by the pore formation of the first batch of liposomes, one would expect no leakage from the second batch of liposomes. However, this was not the case, and the level of leakage of the second batch was significant, even at conditions where only partial (<100%) leakage of the first batch of liposomes was observed (Fig. 3B). This implies that melittin is capable of pore formation in freshly added liposomes, but not in liposomes already present in the solution. A dual-color fluorescence-burst experiment (18, 20) indicated that this finding was independent of the lipid concentration, as similar results were obtained for 250-fold higher concentrations of lipids (Fig. 3C). Next, the fraction of melittin bound to the membrane and the reversibility of the binding were assessed. Melittin was added to liposome suspensions, and the liposomes were washed and pelleted by centrifugation (270,000 × g, 20 min). Tryptophan fluorescence was used to determine the fraction of melittin bound to the liposomes (Fig. 3D). About 1 melittin bound per 100 lipid molecules. Most important, melittin was readily removed from the liposomes by washing, indicating that binding of melittin to the membrane is reversible.

FIGURE 3.

Two-step leakage experiments with melittin and DOPC liposomes. A, calcein dequenching experiments. At time t1, 1 μm total lipid concentration in the form of liposomes were added to the cuvette. The liposomes were loaded with either 100 mm calcein (solid, dashed curves) or did not contain calcein (dotted curve). At time t2, 35 nm melittin was added to the cuvette, and leakage was determined from the changes in fluorescence. For the solid and dotted curves, a second batch (1 μm) of liposomes loaded with calcein was added at time t3. At time t4 (solid, dotted) or time t3 (dashed), 0.03% (w/v) of Triton X-100 was added to determine the 100% level of leakage. B, two-step calcein dequenching experiments similar to A, with various concentrations of melittin. The leakage of the first (solid line, ▪) and second batch of liposomes (dotted line, •) is indicated. C, similar to B but using dual-color fluorescence-burst analysis (18, 20) instead of the calcein dequenching assay, and using 250 μm lipids. The experiments from A–C show that melittin is capable of pore formation in freshly added liposomes but not in liposomes already present in solution. D, reversible binding of melittin to the membranes. DOPC liposomes were equilibrated with 44 μm of melittin, and the fractions of liposome-bound and free melittin were determined (x-axis, lipid concentration). The liposomes were harvested and washed by centrifugation and then dissolved with 1% (w/v) n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside. The melittin concentrations of the supernatant (solid line), washing solution (dotted line), and pellet (dashed line) were determined by tryptophan fluorescence. Error bars are from at least 2 independent experiments.

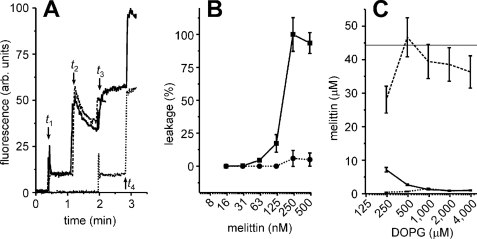

In addition to the zwitterionic DOPC, we also performed two-step calcein dequenching experiments with liposomes composed of the anionic phospholipid DOPG (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylglycerol). For liposomes composed of DOPG, melittin elicited calcein leakage from the first but not from the second batch of liposomes (Fig. 4, A and B). Thus, for DOPG, melittin did not cause leakage in freshly added liposomes, presumably because of the extremely high binding coefficient (e.g. ∼10-fold higher than for PC (14, 16)), which dropped the free concentration of melittin to below that needed for leakage. Indeed, binding experiments indicated that melittin bound much more strongly to DOPG than to DOPC liposomes because virtually all melittin was absorbed to the membrane for melittin/lipid molecule ratios up to 0.1. In addition, melittin could not be removed from the liposomes by washing, implying that binding of melittin to DOPG membranes is essentially irreversible (Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 4.

Two-step leakage experiments with melittin and DOPG liposomes. A, calcein dequenching experiments similar to Fig. 3A, but using 1 μm DOPG lipids in the form of liposomes and 250 nm melittin. The decrease in fluorescence at time t2 is not caused by photobleaching but probably by fusion of the liposomes (18). B, two-step calcein dequenching experiments similar to A, with various concentrations of melittin. The leakage of the first (solid line, ▪) and second batch of liposomes (dotted line, •) is indicated. C, same as Fig. 3D, but for liposomes composed of pure DOPG instead of DOPC. The experiments from A–C indicate that melittin did not cause leakage of the second batch and that all melittin irreversibly bound to the first batch of DOPG liposomes. Error bars are from at least two independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Our data clearly show that melittin is able to induce leakage in freshly added liposomes composed of DOPC (not of DOPG), but not in liposomes already present in solution and saturated with melittin. Melittin is thus able both to cause and to prevent pore formation. This cannot be understood in terms of the two-step model presented in the Introduction (Fig. 1A). Therefore, we propose an alternative mechanism for pore formation (Fig. 1B) in which the parallel binding to the membrane by melittin actually competes with the peptide insertion and thus pore formation. Here, and similar to the two-step model (11), α-helical melittin associates with the membrane either in an inactive conformation, oriented parallel to the membrane, or in a pore-forming conformation, inserted perpendicular in the membrane. However, contrary to the two-step model, the reorientation from parallel to perpendicular does not take place, but instead both the parallel binding and direct insertion are competing events. In addition, the membrane has only a limited capacity to absorb melittin, and hence melittin bound to the surface prevents other molecules from forming pores. This explains why melittin is both capable of pore formation and able to prevent leakage. The inhibition of pore formation by surface-bound melittin can be explained by the elasticity theory, where a repulsive force extending to a distance of about 2.5 nm was calculated for surface-adsorbed peptides (26). This is in agreement with fluorescence resonance energy transfer experiments, where it was shown that magainin 2, a cationic α-helical pore-forming peptide similar to melittin, was not randomly localized on PC membranes. Rather, a minimum distance of about 2 nm was observed between the molecules (27).

Contrary to DOPC, essentially all melittin bound to liposomes composed of DOPG and did not cause pore formation in freshly added liposomes. This indicates that the disruption of membranes composed of anionic lipids probably proceeds via a mechanism different from that for DOPC. This is also apparent from our recent findings, that for DOPC the pore size is dependent on the melittin concentration (18), as was also observed by others (28–30), whereas for DOPG leakage is completely a-specific for compounds with diameters up to at least 5 nm, and leakage was accompanied by membrane fusion (18). The interaction of melittin with PG headgroups is much stronger than for PC, and it has been proposed that melittin does not insert into the membrane but only accumulates at the surface. This asymmetric accumulation would lead to membrane thinning and nonselective membrane damage (14, 30–33). At very high concentrations of melittin, the peptide might disrupt PC membranes in a similar fashion as PG membranes (18, 34). However, these concentrations are much higher than needed for pore formation (e.g. melittin/lipid molecule ratios of 0.5 (18)). Pore formation in membranes composed of PC headgroups might be physiologically more relevant than for anionic headgroups, because the erythrocyte membrane, the natural target of melittin, is mainly zwitterionic (35). Moreover, anionic lipids are preferentially located in the inner leaflet of the membrane.

In conclusion, we show that melittin exerts two effects on liposomes composed of zwitterionic DOPC lipids. First, the peptide forms pores leading to content leakage from the vesicles. Second, melittin binds to the membrane surface in an inactive conformation, thereby preventing other melittin molecules from inserting into the bilayer and hence protecting the membrane from leakage. This level of understanding of the mechanism of action of lytic peptides is essential for their development as pharmaceutical agents, e.g. as antibiotics or hemolytic therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Koçer, G. K. Schuurman-Wolters, and V. Krasnikov (University of Groningen, The Netherlands) for helpful advice.

This work was supported by the Dutch Science Foundation (NWO, Grant ALW-814.02.002) and the Zernike Institute for Advanced Materials. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: PC, phosphatidylcholine; CD, circular dichroism; DOPC, 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine; DOPG, 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylglycerol.

References

- 1.Brogden, K. A. (2005) Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3 238–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finlay, B. B., and Hancock, R. E. (2004) Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2 497–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raghuraman, H., and Chattopadhyay, A. (2007) Biosci. Rep. 27 189–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Son, D. J., Lee, J. W., Lee, Y. H., Song, H. S., Lee, C. K., and Hong, J. T. (2007) Pharmacol. Ther. 115 246–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee, M. T., Hung, W. C., Chen, F. Y., and Huang, H. W. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105 5087–5092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hristova, K., Dempsey, C. E., and White, S. H. (2001) Biophys. J. 80 801–811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He, K., Ludtke, S. J., Heller, W. T., and Huang, H. W. (1996) Biophys. J. 71 2669–2679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steiner, H., Andreu, D., and Merrifield, R. B. (1988) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 939 260–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ludtke, S. J., He, K., Heller, W. T., Harroun, T. A., Yang, L., and Huang, H. W. (1996) Biochemistry 35 13723–13728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang, L., Harroun, T. A., Weiss, T. M., Ding, L., and Huang, H. W. (2001) Biophys. J. 81 1475–1485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang, H. W. (2000) Biochemistry 39 8347–8352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, L. Y., Cheng, C. W., Lin, J. J., and Chen, W. Y. (2007) Anal. Biochem. 367 49–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benachir, T., and Lafleur, M. (1995) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1235 452–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strömstedt, A. A., Wessman, P., Ringstad, L., Edwards, K., and Malmsten, M. (2007) J. Colloid Interface Sci. 311 59–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beschiaschvili, G., and Baeuerle, H.-D. (1991) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1068 195–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dufourcq, J., and Faucon, J. F. (1977) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 467 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwarz, G., and Beschiaschvili, G. (1989) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 979 82–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van den Bogaart, G., Mika, J. T., Krasnikov, V., and Poolman, B. (2007) Biophys. J. 93 154–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koçer, A., Walko, M., Meijberg, W., and Feringa, B. L. (2005) Science 309 755–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van den Bogaart, G., Krasnikov, V., and Poolman, B. (2007) Biophys. J. 92 1233–1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen, T. M., and Cleland, L. G. (1980) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 597 418–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kleinschmidt, J. H., Mahaney, J. E., Thomas, D. D., and Marsh, D. (1997) Biophys. J. 72 767–778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kubota, S., and Yang, J. T. (1986) Biopolymers 25 1493–1504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown, L. R., Lauterwein, J., and Wüthrich, K. (1980) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 622 231–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goto, Y., and Hagihara, Y. (1992) Biochemistry 31 732–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang, H. W. (1995) J. Phys. II France 5 1427–1431 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schümann, M., Dathe, M., Wieprecht, T., Beyermann, M., and Bienert, M. (1997) Biochemistry 36 4345–4351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ladokhin, A. S., Selsted, M. E., and White, S. H. (1997) Biophys. J. 72 1762–1766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park, S. C., Kim, J. Y., Shin, S. O., Jeong, C. Y., Kim, M. H., Shin, S. Y., Cheong, G. W., Park, Y., and Hahm, K. S. (2006) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 343 222–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsuzaki, K., Yoneyama, S., and Miyajima, K. (1997) Biophys. J. 73 831–838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ladokhin, A. S., and White, S. H. (2001) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1514 253–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghosh, A. K., Rukmini, R., and Chattopadhyay, A. (1997) Biochemistry 36 14291–14305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee, T. H., Mozsolits, H., and Aguilar, M. I. (2001) J. Pept. Res. 58 464–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Popplewell, J. F., Swann, M. J., Freeman, N. J., McDonnell, C., and Ford, R. C. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1768 13–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verkleij, A. J., Zwaal, R. F., Roelofsen, B., Comfurius, P., Kastelijn, D., and Van Deenen, L. L. (1973) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 323 178–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]