Abstract

The canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway plays a pivotal role in regulating embryogenesis and tumorigenesis by promoting cell proliferation. BAMBI (BMP and activin membrane-bound inhibitor) has previously been shown to negatively regulate the signaling activity of transforming growth factor-β, activin, and BMP and was identified as a target of β-catenin in colorectal and hepatocellular tumor cells. In this study, we provide evidence that BAMBI can promote the transcriptional activity of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Overexpression of BAMBI enhances the expression of Wnt-responsive reporters, whereas knockdown of endogenous BAMBI attenuates them. Accordingly, BAMBI also promotes the nuclear translocation of β-catenin. BAMBI interacts with Wnt receptor Frizzled5, coreceptor LRP6, and Dishevelled2 and increases the interaction between Frizzled5 and Dishevelled2. Finally we show that BAMBI promotes the expression of c-myc and cyclin D1 and increases Wnt-promoted cell cycle progression. Altogether, our data indicate that BAMBI can function as a positive regulator of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway to promote cell proliferation.

Wnt signaling is initiated by binding to its seven-transmembrane receptor, Frizzled (Fzd),2 and single-span transmembrane coreceptor low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 and 6 (LRP5/6) (1–4). Dishevelled (Dvl) and β-catenin play an essential role in the canonical Wnt signaling. In the absence of Wnt proteins, β-catenin is phosphorylated (5–11) and ubiquitinated and then targeted for proteasome-mediated degradation by a cytoplasmic destruction complex consisting of adenomatous polyposis coli, Axin, glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β), and casein kinase 1. The binding of Wnt ligands to the receptors results in the recruitment of Dvl to the plasma membrane and therefore the disassembly of the destructive complex, leading to the accumulation and nuclear translocation of β-catenin, which collaborates with the transcription factors of the lymphoid enhancer-binding factor (LEF)/T-cell factor (TCF) family and activates the transcription of Wnt target genes.

The Wnt signaling pathway plays key roles in embryogenesis and adult homeostasis and is aberrantly activated in various human cancers (3, 4). For instance, in most of colorectal cancers, β-catenin is stabilized and accumulated in the nucleus and constitutively activates its target genes (12, 13). A wide spectrum of β-catenin targets, such as the proteins involved in cell cycle, cell-matrix interactions, migration, and invasion, has been identified (14–16). One of such targets is BAMBI (BMP and activin membrane-bound inhibitor), which has been found to be directly up-regulated by the functional β-catenin-TCF4 complex in colorectal tumor cells (17).

The BAMBI gene encodes a 260-amino acid transmembrane protein that is evolutionally conserved in vertebrates, from fish to human (18–22). The BAMBI protein is closely related to type I receptors of the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) family in the extracellular domain but has a short intracellular domain, which lacks noticeable enzymatic activity. It has been documented that Xenopus BAMBI functions as a general antagonist for TGF-β family members (TGF-β, activin, and BMP) by acting as a pseudoreceptor to block the interaction of signaling type I and type II receptors (18). BAMBI is tightly coexpressed with BMP during development in Xenopus, mouse, and zebrafish (18, 20, 21, 23, 24), and its expression is induced by BMP4 (18, 24), TGF-β (25), β-catenin (17), lipopolysaccharide (26), and retinoic acid (23).

Several studies have suggested that BAMBI is involved in pathogenesis of various kinds of human diseases. The human BAMBI, initially named as nma, is down-regulated in metastatic melanoma cell lines (22), and has been implicated to promote cell growth and invasion in human gastric carcinoma cell lines (27). A recent study has also suggested that BAMBI is involved in Toll-like receptor 4- and lipopolysaccharide-mediated hepatic fibrosis (26). Because BAMBI expression can be directly induced by β-catenin (17), it is worthy to examine whether BAMBI regulates Wnt signaling. In this study, we provide evidence that BAMBI can enhance the canonical Wnt signaling while knockdown of BAMBI expression impairs Wnt-induced expression of the LEF-luciferase reporter. We showed that BAMBI interacts with Fzd and Dvl and promotes the interaction of Dvl with Fzd. We further found that BAMBI can enhance the Wnt-induced transcription of target genes, cyclin D1 and c-myc, and its overexpression facilitates the G1 to S phase transition. These findings strongly suggest that BAMBI is a positive regulator of the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials and Plasmids—Human BAMBI (nma) cDNA was generously provided by Dr. G. W. Swart (University of Nijmegen, The Netherlands) and tagged with myc or HA tags at the C terminus and subcloned into pCMV5. The constructs encoding the extracellular-transmembrane domain (aa 1–173) or the transmembrane-intracellular domain (aa 153–260) (with signal peptide, aa 1–20) of BAMBI were generated by PCR and sub-cloned into pCMV with the myc tag at the C terminus. siRNA construct to knock down human BAMBI expression was generated by subcloning into pSUPER vector of the double nucleotide sequences annealed from the following oligonucleotides: forward, 5′-GATCCCCATCTGAGCTCAGCGCCTGCTTCAAGAGAGCAGGCGCTGAGCTCAGATTTTTTGAAA-3′ and reverse, 5′-AGCTTTTCCAAAAAatctgagctcagcgcctgcTCTCTTGAAgcaggcgctgagctcagatGGG-3′; nonspecific siRNA sequence: 5′-AGCGGACTAAGTCCATTGC-3′. Three domains (DIX: aa 1–110; PDZ: aa 219–390; DEP: aa 420–520) of Dvl2 were cloned into pcs2 FLAG empty vector. Rabbit polyclonal antibody to human BAMBI was prepared by immunizing rabbits with a synthesized peptide (HWGMYSGHGKLEFV). Goat polyclonal antibody against Frizzled 5 and Dvl2 was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Cell Culture—Hep3B cells were maintained in minimum essential medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and HEK293T cells in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum.

RT-PCR Analysis—Total cellular RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was prepared from 1 μg of total RNA by reverse transcription (RT) at 42 °C for 45 min. RT reaction products (2 μl) were amplified in a 20-μl PCR mixture in 20 mm Tris-HCl buffer containing 200 μm dNTPs, 0.5 unit of TaqDNA polymerase, and 0.2 μm specific upstream and downstream primers. The PCR reaction was performed in a Thermocycler (Bio-Rad). PCR was performed with the following primer sets: glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase: 5′-CATCACTGCCACCCAGAAGA-3′ and 5′-GCTGTAGCCAAATTCGTTGT-3′; c-Myc: 5′-CCTACCCTCTAACGACAGC-3′ and 5′-CTCTGACCTTTTGCCAGGAG-3′; cyclin D1: 5′-ATCGAAGCCCTGCTGGAGT-3′ and 5′-GGGAAAGAGCAAAGGAAAA-3′; BAMBI: 5′-ATGGATCGCCACTCCAGC-3′ and 5′-TCATACGAATTCCAGCTTCC-3′; Axin2: 5′-GCCTGCCCAAGGAGATGACCC-3′ and 5′-CTTCGTCGTCTGCTTGGTCAC-3′.

Luciferase Reporter Assays—Cells were plated in 24-well dishes at 18 h prior to transfection. Transfections were performed with Lipofectamine reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Luciferase activity was measured at 48 h after transfection by using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter assay system (Promega, Madison, WI) following the manufacturer's protocol. Student's t test was performed to assess the significance of treatments versus controls. Asterisks in the figures represent p values of <0.05 to indicate statistical significance.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting Analysis—Cells were plated in 100-mm dishes at 18 h prior to transfection. Transfections were performed with calcium phosphate, and cells were lysed at 4 °C for 10 min with lysis solution (100 mm KCl, 10 mm Hepes, pH 7.9, 10% glycerol, 5 mm MgCl2, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 10 mm NaF, 20 mm sodium β-glycerol phosphate, 1 mm dithiothreitol, and protease inhibitors). Aliquots of total cell lysates containing equivalent amounts of total protein were precleared for 4 h with protein A-Sepharose at 4 °C. Specific immunoprecipitations of the precleared lysates were carried out in the presence of the appropriate antibody. After overnight incubation at 4 °C, immunoprecipitates were isolated by centrifugation and washed four times with lysis buffer. Protein levels were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with the proper antibody and detected with the enhanced chemiluminescent substrate (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Subcellular Fractionation—HEK293T cells were harvested by scraping and resuspended in low salt buffer (20 mm Hepes, pH 7.9, 20 mm EDTA, 20 mm KCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 0.5 mm dithiothreitol, 0.5 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) on ice for 15 min and then centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 5 min. The low speed centrifugation was washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline three times and then resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS) and lysed by sonification. After centrifugation at 18,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, the supernatant (nuclear extracts) was collected for further analysis.

Flow Cytometry—Cells from 60-mm dishes were suspended in cold phosphate-buffered saline and fixed by 75% ethanol at –20 °C for >2 h. The fixed cells were then centrifuged and resuspended in 0.5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline. RNase A was added, and the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Then cells were stained by using propidium iodide, and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 5–10 min and subsequently analyzed with a BD Biosciences flow cytometer.

RESULTS

BAMBI Promotes Wnt Signaling—As the β-catenin/TCF complex induces the expression of BAMBI in colorectal and hepatocellular tumor cells (17), we attempted to investigate whether BAMBI has an effect on Wnt signaling by using the Wnt-responsive LEF-luciferase reporter. As shown in Fig. 1A, in human embryonic kidney HEK293T cells, LEF-luciferase activity was elevated by co-expression of human BAMBI (left panel). Furthermore, the BAMBI activation of this reporter was further enhanced by Wnt-1 and the promotion of BAMBI on Wnt-1 signaling is dose-dependent (Fig. 1A, right panel). To explore whether BAMBI has a general effect on the transcriptional responses of Wnt-1, the expression of another Wnt-responsive reporter, Topflash-luciferase, was tested in HEK293T cells. The elevation of this reporter activity induced by Wnt-1 was dramatically promoted by co-transfection with BAMBI (Fig. 1B, left panel). This elevation is specific as BAMBI had no effect on Fopflash (Fig. 1B, right panel), which was used as a negative control (28). Therefore, we concluded from the above data that BAMBI can promote Wnt signaling in a dose-dependent manner.

FIGURE 1.

BAMBI enhances the expression of the Wnt-responsive reporters. In A: Left panel, BAMBI increases the expression of the Wnt-responsive LEF-luciferase. HEK293T cells were transfected with LEF-luciferase (0.5 μg) along with Wnt-1 (0.2 μg) or BAMBI (0.2 μg) and at 48 h post-transfection, cells were harvested for luciferase measurement. Right panel, BAMBI enhances the Wnt-1-activated expression of LEF-luciferase in a dose-dependent manner. Increasing amount of BAMBI plasmids (0.1, 0.2, to 0.4 μg) were transfected into HEK293T cells with LEF-luciferase (0.5 μg) and Wnt-1 (0.1 μg), and reporter assay was performed at 48 h post-transfection. B, BAMBI increases the Wnt-1-induced expression of Topflash. Topflash (left panel) or Fopflash (right panel) (0.5 μg each) was transfected into HEK293T cells along with Wnt-1 (0.2 μg) or BAMBI (0.2 μg), and reporter assay was performed at 48 h post-transfection. For transfection, the total amount of DNA was adjusted with empty plasmid. The pRL-tk Renilla reporter (20 ng) was co-transfected to normalize transfection efficiency. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, and the data represent the mean ± S.D. after normalized to Renilla activity. The asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference (**, p < 0.01).

Because ectopic expression of BAMBI increases Wnt signaling, we then asked whether endogenous BAMBI plays any role in Wnt/β-catenin signaling. To this purpose, we generated an siRNA construct against BAMBI (si-BAMBI) and examined its effectiveness on Wnt-1-induced expression of LEF-luciferase in HEK293T cells that express BAMBI protein (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 2A, ectopic expression of BAMBI could be effectively knocked down by BAMBI siRNA, but not by a nonspecific control siRNA. To examine whether knockdown of BAMBI expression can decrease Wnt signaling, HEK293T cells were transfected with LEF-luciferase reporter together with BAMBI siRNA or control siRNA, and the transcriptional response of Wnt was assessed by measuring luciferase activity. Consistent with the promoting role of BAMBI, BAMBI siRNA impaired the Wnt-induced expression of LEF-luciferase in HEK293T cells (Fig. 2B). Similar results were obtained in hepatoma Hep3B cells: ectopic expression of BAMBI enhanced the Wnt-1-induced expression of LEF-luciferase, whereas BAMBI siRNA attenuated it (Fig. 2C). These data further support the observation that BAMBI is a positive regulator of Wnt signaling.

FIGURE 2.

Knockdown of endogenous BAMBI expression impairs Wnt signaling. A, BAMBI siRNA effectively suppresses BAMBI expression. HEK293T cells were transfected with indicated constructs, and at 40 h post-transfection, the cells were harvested for immunoblotting. Tubulin was used as a loading control. B and C, knockdown of endogenous BAMBI expression impairs the Wnt-induced expression of LEF-luciferase. LEF-luciferase was cotransfected into HEK293T (B) or Hep3B (C) cells with indicated plasmids (0.3 μg) together with or without Wnt-1 (0.2 μg). Then luciferase activity was determined as in Fig. 1. The asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference (**, p < 0.01). D, BAMBI enhances the nuclear accumulation of β-catenin. HEK293T cells were transfected with the constructs as indicated. At 40 h post-transfection, the cells were harvested, and anti-β-catenin immunoblotting was performed with the nuclear lysates. Lamin was used as a nuclear marker. Si-NS, nonspecific siRNA; si-BAMBI, siRNA specific for BAMBI.

β-Catenin, the key molecule to mediate the canonical Wnt signaling, translocates to the nucleus in the presence of Wnt ligands. To support the above reporter assays, we examined whether BAMBI also enhances the nuclear translocation of β-catenin. HEK293T cells were transfected with various constructs as indicated in Fig. 2D and then the endogenous β-catenin protein in the nuclear fractions was revealed by immunoblotting. Ectopic expression of BAMBI enhanced the protein level of β-catenin in the nucleus in the presence or absence of Wnt, and knocking down of BAMBI expression decreased the nuclear β-catenin level (Fig. 2D). These data are consistent with the stimulating role of BAMBI in the canonical Wnt signaling.

BAMBI Interacts with Wnt Signaling Receptors Fzd5 and LRP6—The canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling requires two distinct transmembrane receptors Fzd and LRP5/6 (29). Because BAMBI is a transmembrane protein and it can increase Wnt signaling, we attempted to test whether BAMBI can associate with Wnt receptors. The interaction of BAMBI with Fzd5 at endogenous protein levels was examined by anti-BAMBI immunoprecipitation and anti-Fzd5 immunoblotting from HEK293T cells (Fig. 3A). This interaction was confirmed by ectopically expressed proteins (Fig. 3B) and by reverse immunoprecipitation-immunoblotting analysis with ectopically expressed HA-tagged Fzd5 and myc-tagged BAMBI (Fig. 3C). We further examined whether BAMBI can associate with LRP6 and found that BAMBI could be detected in LRP6 immunoprecipitants (Fig. 3D), indicating that BAMBI can also form a complex with LRP6. The interaction of BAMBI with Fzd5 or LRP6 seems constitutive, because co-expression of Wnt-1 had no effect on their complex formation (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

BAMBI interacts with Fzd5 and LRP6. A, BAMBI interacts with Fzd5 at the endogenous protein levels. HEK293T cell lysates were subject to immunoprecipitation with control rabbit IgG or anti-BAMBI antibody followed by anti-Fzd5 immunoblotting (upper panel). Protein expression was confirmed by immunoblotting (middle and lower panels). C, rabbit control IgG. B and C, BAMBI associates with Fzd5 when overexpressed. HEK293T cells were transfected with indicated HA-tagged Fzd5 and myc-tagged BAMBI. At 40 h post-transfection, the cell lysates were harvested for anti-myc (B) or anti-HA (C) immunoprecipitation and anti-HA (B) or anti-myc (C) immunoblotting (top panel). Protein expression was confirmed by immunoblotting of 10% of the total lysate (middle and lower panels). IgG-L, light chain IgG; IgG-H, heavy chain IgG. D, BAMBI interacts with LRP6. Protein interaction was examined as in B. E, Fzd5 binds to both the extracellular (BAMBI-N) and intracellular (BAMBI-C) domains of BAMBI, whereas LRP6 associates only with BAMBI-C. HEK293 cells were transfected with the constructs (5 μg each) as indicated. Protein interaction was examined as in B. F, BAMBI-C, but not BAMBI-N, has the ability to promote Wnt signaling. Reporter assay in HEK293T cells was performed as in Fig. 1. In all the experiments shown here, the total amount of plasmid DNA was adjusted with pCMV5 empty plasmid.

BAMBI consists of an extracellular domain and an intracellular domain spanned by a transmembrane region. Then, we wanted to define the domain of BAMBI responsible for interacting with the receptors. We generated two BAMBI deletion constructs, which correspond to the extracellular (BAMBI-N) and intracellular (BAMBI-C) domains of BAMBI, respectively (Fig. 3E). Both the extracellular and intracellular domains of BAMBI could bind to Frizzled 5, but only the intracellular domain interacted with LRP6 (Fig. 3E). These data together suggest that BAMBI may form a ternary coreceptor complex with Fzd5 and LRP6. We then tried to explore whether BAMBI is able to promote the complex formation between Fzd5 and LRP6, but could not detect the complex at all the tested conditions (data not shown).

Because the intracellular domain of BAMBI can interact with both Fzd5 and LRP6, we wanted to know whether this domain contributes to the promoting effect of BAMBI on Wnt signaling. As shown in Fig. 3F, BAMBI-C mildly enhanced the expression of LEF-luciferase while BAMBI-N showed no effect.

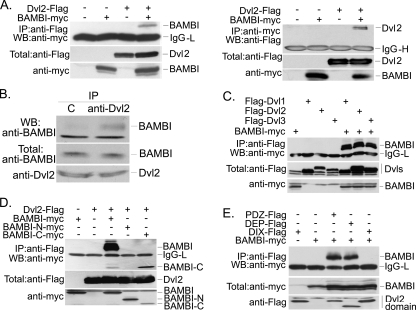

BAMBI Binds to Dishevelled—As BAMBI cannot strengthen the interaction between Fzd and LRP, we speculated that BAMBI may promote Wnt signaling by facilitating Dvl recruitment to the membrane receptors and then leading to the disruption of the cytoplasmic destruction complex consisting of adenomatous polyposis coli, Axin, and GSK3β and thus the stabilization of β-catenin. To test this hypothesis, we first examined whether BAMBI can interact with Dvl, one of the key components of the canonical and noncanonical Wnt pathways. HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with FLAG-tagged Dvl2 and myc-tagged BAMBI, the cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation immunoblotting. BAMBI was found to coimmunoprecipitate with Dvl (Fig. 4A, left panel). And this interaction was further confirmed by reverse immunoprecipitation-immunoblotting (Fig. 4A, right panel) and at the endogenous protein levels (Fig. 4B). To test whether the BAMBI-Dvl2 is specific, we examined the interaction of BAMBI with other Dvl proteins. Our result revealed that BAMBI was able to associate with Dvl1 and Dvl3 as well (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that BAMBI and Dvl associate with each other. Interestingly, BAMBI did not associate with Axin or GSK3β (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

BAMBI associates with Dishevelled. A, BAMBI interacts with Dvl2. HEK293T cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged Dvl2 and myc-tagged BAMBI. B, BAMBI associates with Dvl2 at endogenous levels. HEK293T cell lysates were subject to immunoprecipitation with control IgG or anti-Dvl2 antibody followed by anti-BAMBI immunoblotting. C, BAMBI binds to three isoforms of Dvl. HEK293T cells were transfected with indicated constructs. D, BAMBI interacts with Dvl2 via its intracellular domain. E, both the PDZ and DEP domains of Dvl2 can interact with BAMBI. In all of the immunoprecipitation assays (except B), 5 μg of DNA for each construct was transfected and the total amount of plasmid DNA was adjusted with pCMV5 empty vector. At 40 h post-transfection, the cells were harvested and subjected to immunoprecipitation and then immunoblotting analysis (upper panel). Protein expression was confirmed by immunoblotting of total cell lysates (middle and lower panels).

To map the regions mediating the BAMBI-Dvl interaction, we examined the ability of various regions of these two proteins to interact with their counterpart. As expected, Dvl2 interacted only with the intracellular domain but not with the extracellular domain of BAMBI (Fig. 4D). Interestingly, both the PDZ and DEP domains of Dvl2 could interact with BAMBI (Fig. 4E).

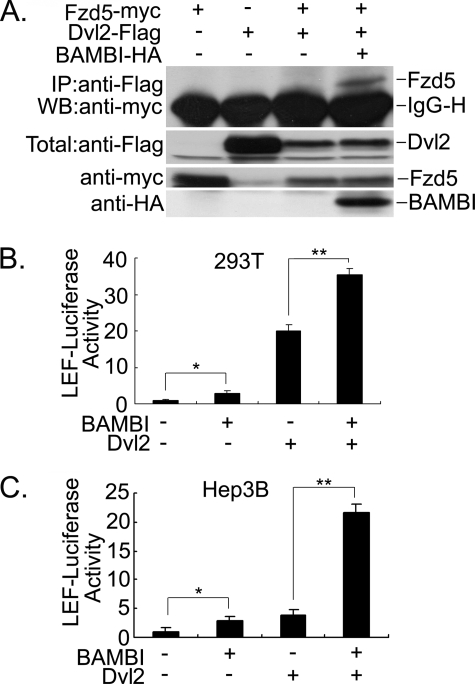

BAMBI Enhances the Interaction of Fzd5 and Dvl2—The Wnt signal is propagated following the binding of Wnt ligands to a hetero-oligomeric receptor complex consisting of Fzd and LRP5/6 (29–31), which results in the recruitment of Axin to LRP (32, 33) and Dvl to Fzd (29, 34). However, the interaction between Dvl and Frizzled is apparently weak, and it is unclear whether other proteins are involved in this process. Our above data indicated that BAMBI can associate with Fzd5 and Dvl, thus we studied whether BAMBI could augment the interaction between Fzd5 and Dvl2. The data in Fig. 5A demonstrated that BAMBI promoted the interaction of Fzd5 with Dvl2, which, otherwise, was observed in the absence of Wnt-1. In agreement with this observation, BAMBI could synergize with Dvl2 to enhance Wnt signaling as determined by the expression of LEF-luciferase in HEK293T (Fig. 5B) and in Hep3B (Fig. 5C) cells, respectively.

FIGURE 5.

BAMBI enhances the interaction between Fzd5 and Dvl2. A, BAMBI increases the interaction between Fzd5 and Dvl2. Extracts from HEK293T cells ectopically expressing the constructs (5 μg for each) as indicated were subjected to anti-FLAG immunoprecipitation and anti-myc immunoblotting (top panel). Protein expression was confirmed by immunoblotting of 10% of the total lysate (middle and lower panels). IgG-H, heavy chain IgG. B and C, BAMBI synergizes with Dvl2 to increase the expression of LEF-luciferase in HEK293T (B) and Hep3B (C) cells. Cells were transfected with LEF-luciferase together with Dvl2 (0.2 μg) and BAMBI (0.3 μg). Reporter assay was performed as in Fig. 1. The asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01).

BAMBI Promotes Wnt-induced Cell Growth—Wnt signaling promotes cell proliferation by up-regulating the key mediators of cell cycle, including cyclin D1 and c-myc (35–37). Then, we examined whether BAMBI could promote cyclin D1 expression by using a luciferase reporter driven by cyclin D1 promoter (36) in HEK293T cells. As shown in Fig. 6A, BAMBI increased the reporter activity in the presence or absence of Wnt-1, indicating that BAMBI can promote cyclin D1 expression. BAMBI also promoted the luciferase expression driven by the c-myc promoter (Fig. 6B). To investigate whether BAMBI is required for the expression of Wnt target genes, we examined the expression of three well known Wnt targets: cyclin D1, c-myc, and Axin2 after knocking down endogenous BAMBI. The RT-PCR analysis revealed that blocking BAMBI expression by siRNA dramatically decreased the expression of these genes (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 6.

BAMBI enhances the cell proliferation-promoting effect of Wnt1. A, BAMBI increases the expression of a cyclin D1 promoter-driven reporter. HEK293T cells were co-transfected with a cyclin D1 luciferase reporter as well as indicated constructs, and the luciferase activity was measured at 48 h post-transfection. B, BAMBI increases the expression of a c-myc promoter-driven reporter. The asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference (**, p < 0.01). C, knockdown of endogenous BAMBI reduces the expression of Wnt target genes in HEK293T cells. HEK293T cells were transfected with indicated plasmids (3 μg for each), and the total amount of DNA plasmid was adjusted with corresponding empty vector. At 48 h post-transfection, the cells were harvested for RT-PCR analysis. Glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a control. D, BAMBI promotes cell growth. HEK293T cells were transfected with control vector or BAMBI together with or without Wnt-1 plasmid (3 μg for each). At 48 h post-transfection, the cells were harvested for fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis.

To study the effect of BAMBI on Wnt signaling in a physiological context, HEK293T cells were transfected with BAMBI plasmid together with or without Wnt-1 plasmid. After 48 h cells were harvested and subjected to cell cycle analysis with fluorescence-activated cell sorting. As shown in Fig. 6D, Wnt treatment promoted cell cycle progression from G1 to S phase, and BAMBI overexpression has a similar promoting effect. Importantly, BAMBI enhanced the effect of Wnt-1.

DISCUSSION

BAMBI has been suggested to act as a general antagonist to block signal transduction of the TGF-β family members. Here, we provide evidence that BAMBI can promote Wnt/β-catenin signaling. We demonstrated that BAMBI enhances the expression of the Wnt-responsive reporters LEF-luciferase and Topflash-luciferase, but not the control Fopflash-luciferase, in the presence or absence of Wnt-1. Consistent with the reporter assay, BAMBI also stimulated the nuclear accumulation of β-catenin. We further showed that BAMBI can interact with receptors Fzd5 and LRP6 as well as the intracellular signaling mediator Dvl. The promoting effect of BAMBI on Wnt signaling could result from these interactions, because the association between Fzd and Dvl was increased by BAMBI. Finally, we found that BAMBI also cooperates with Wnt-1 to stimulate the expression of cyclin D1 and c-myc and to promote cell cycle progression.

It is generally regarded that, upon Wnt binding, the membrane receptor Fzd recruits the cytosolic protein Dvl onto the plasma membrane and the co-receptor LRP5/6 associates with the scaffold protein Axin (3, 4, 38, 39). These interactions lead to the disruption of the destruction complex consisting of adenomatous polyposis coli, Axin, GSK3β, casein kinase 1, and others and the accumulation in the nucleus of cytosolic β-catenin, which in turn associates with the TCF/LEF family of transcription factors and activates transcription of their target genes. We showed here that BAMBI can activate the Wnt-responsive reporters LEF-luciferase and Topflash. Our protein-protein interaction analyses revealed that BAMBI interacts with Fzd5, LRP6, and Dvl, but not with other components in the canonical Wnt pathway we have examined. The intracellular domain of BAMBI is important for the interaction with all three proteins while the extracellular domain can associate only with Fzd, which is consistent with the topological structure of BAMBI as a single-spanned transmembrane protein. It has been demonstrated that Wnt treatment results in the plasma membrane recruitment of Dvl (34), but the binding of Dvl to Fzd could be relatively weak (40). Our data uncovered that BAMBI can increase the interaction between Fzd and Dvl as this interaction became detectable only in the presence of BAMBI in our experimental condition (Fig. 5A). Therefore, our results together suggest that BAMBI promotes Wnt/β-catenin signaling by facilitating the Fzd-Dvl interaction. Thus, the functional significance of the BAMBI-LRP6 is unclear and needs further investigation.

The Wnt signaling pathway is activated in most human cancers. Loss-of-function mutations of adenomatous polyposis coli and stabilization mutations of β-catenin lead to the accumulation of β-catenin (12, 13). It is well documented that β-catenin can promote cell cycle progress and lead to the progression of tumorigenesis through increasing the expression of oncogenes like c-myc and cyclin D1 (35–37). Our reporter assays and RT-PCR analyses suggested that BAMBI can induce the expression of cyclin D1 and c-myc (Fig. 6, A–C). Consistent with its promoting effect on target gene expression, BAMBI could also enhance Wnt-induced cell growth (Fig. 6D). Because BAMBI can act both as an antagonist for TGF-β signaling and as a promoter for Wnt signaling, it is reasonable to postulate that BAMBI can function as a promoter of tumorigenesis. Indeed, this idea is in agreement with the observed up-regulation of BAMBI in colorectal and hepatocellular carcinomas (17).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. G. W. Swart for human BAMBI cDNA.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 30430360, 30671033, and 90713045), the 973 Program (Grants 2004CB720002, 2006CB943401, and 2006CB910102), and the 863 Program (Grant 2006AA02Z172). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: Fzd, Frizzled; BAMBI, BMP and activin membrane-bound inhibitor; Dvl, Dishevelled; GSK3β, glycogen synthase kinase 3β; LEF, lymphoid enhancer-binding factor; LRP5/6, low density lipoprotein receptor-related proteins 5 and 6; TCF, T-cell factor; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; CMV, cytomegalovirus; aa, amino acid(s); siRNA, small interference RNA; RT, reverse transcription; HA, hemagglutinin.

References

- 1.Nusse, R. (2005) Cell Res. 15 28–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reya, T., and Clevers, H. (2005) Nature 434 843–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moon, R. T., Kohn, A. D., De Ferrari, G. V., and Kaykas, A. (2004) Nat. Rev. Genet. 5 691–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clevers, H. (2006) Cell 127 469–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He, X., Saint-Jeannet, J. P., Woodgett, J. R., Varmus, H. E., and Dawid, I. B. (1995) Nature 374 617–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behrens, J., Jerchow, B. A., Wurtele, M., Grimm, J., Asbrand, C., Wirtz, R., Kuhl, M., Wedlich, D., and Birchmeier, W. (1998) Science 280 596–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ikeda, S., Kishida, S., Yamamoto, H., Murai, H., Koyama, S., and Kikuchi, A. (1998) EMBO J. 17 1371–1384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kishida, S., Yamamoto, H., Ikeda, S., Kishida, M., Sakamoto, I., Koyama, S., and Kikuchi, A. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 10823–10826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li, L., Yuan, H., Weaver, C. D., Mao, J., Farr, G. H., 3rd, Sussman, D. J., Jonkers, J., Kimelman, D., and Wu, D. (1999) EMBO J. 18 4233–4240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farr, G. H., 3rd, Ferkey, D. M., Yost, C., Pierce, S. B., Weaver, C., and Kimelman, D. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 148 691–702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xing, Y., Clements, W. K., Kimelman, D., and Xu, W. (2003) Genes Dev. 17 2753–2764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morin, P. J., Sparks, A. B., Korinek, V., Barker, N., Clevers, H., Vogelstein, B., and Kinzler, K. W. (1997) Science 275 1787–1790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Segditsas, S., and Tomlinson, I. (2006) Oncogene 25 7531–7537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stadeli, R., Hoffmans, R., and Basler, K. (2006) Curr. Biol. 16 R378–R385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hatzis, P., van der Flier, L. G., van Driel, M. A., Guryev, V., Nielsen, F., Denissov, S., Nijman, I. J., Koster, J., Santo, E. E., Welboren, W., Versteeg, R., Cuppen, E., van de Wetering, M., Clevers, H., and Stunnenberg, H. G. (2008) Mol. Cell. Biol. 28 2732–2744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Willert, K., and Jones, K. A. (2006) Genes Dev. 20 1394–1404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sekiya, T., Adachi, S., Kohu, K., Yamada, T., Higuchi, O., Furukawa, Y., Nakamura, Y., Nakamura, T., Tashiro, K., Kuhara, S., Ohwada, S., and Akiyama, T. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 6840–6846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Onichtchouk, D., Chen, Y. G., Dosch, R., Gawantka, V., Delius, H., Massague, J., and Niehrs, C. (1999) Nature 401 480–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loveland, K. L., Bakker, M., Meehan, T., Christy, E., von Schonfeldt, V., Drummond, A., and de Kretser, D. (2003) Endocrinology 144 4180–4186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsang, M., Kim, R., de Caestecker, M. P., Kudoh, T., Roberts, A. B., and Dawid, I. B. (2000) Genesis 28 47–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grotewold, L., Plum, M., Dildrop, R., Peters, T., and Ruther, U. (2001) Mech. Dev. 100 327–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Degen, W. G., Weterman, M. A., van Groningen, J. J., Cornelissen, I. M., Lemmers, J. P., Agterbos, M. A., Geurts van Kessel, A., Swart, G. W., and Bloemers, H. P. (1996) Int. J. Cancer 65 460–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higashihori, N., Song, Y., and Richman, J. M. (2008) Dev. Dyn. 237 1500–1508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karaulanov, E., Knochel, W., and Niehrs, C. (2004) EMBO J. 23 844–856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sekiya, T., Oda, T., Matsuura, K., and Akiyama, T. (2004) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 320 680–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seki, E., De Minicis, S., Osterreicher, C. H., Kluwe, J., Osawa, Y., Brenner, D. A., and Schwabe, R. F. (2007) Nat. Med. 13 1324–1332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sasaki, T., Sasahira, T., Shimura, H., Ikeda, S., and Kuniyasu, H. (2004) Oncol. Rep. 11 1219–1223 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Korinek, V., Barker, N., Morin, P. J., van Wichen, D., de Weger, R., Kinzler, K. W., Vogelstein, B., and Clevers, H. (1997) Science 275 1784–1787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cong, F., and Varmus, H. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101 2882–2887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tamai, K., Semenov, M., Kato, Y., Spokony, R., Liu, C., Katsuyama, Y., Hess, F., Saint-Jeannet, J. P., and He, X. (2000) Nature 407 530–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wehrli, M., Dougan, S. T., Caldwell, K., O'Keefe, L., Schwartz, S., Vaizel-Ohayon, D., Schejter, E., Tomlinson, A., and DiNardo, S. (2000) Nature 407 527–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mao, J., Wang, J., Liu, B., Pan, W., Farr, G. H., 3rd, Flynn, C., Yuan, H., Takada, S., Kimelman, D., Li, L., and Wu, D. (2001) Mol. Cell 7 801–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tolwinski, N. S., Wehrli, M., Rives, A., Erdeniz, N., DiNardo, S., and Wieschaus, E. (2003) Dev. Cell 4 407–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Medina, A., and Steinbeisser, H. (2000) Dev. Dyn. 218 671–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He, T. C., Sparks, A. B., Rago, C., Hermeking, H., Zawel, L., da Costa, L. T., Morin, P. J., Vogelstein, B., and Kinzler, K. W. (1998) Science 281 1509–1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tetsu, O., and McCormick, F. (1999) Nature 398 422–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shtutman, M., Zhurinsky, J., Simcha, I., Albanese, C., D'Amico, M., Pestell, R., and Ben-Ze'ev, A. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96 5522–5527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Logan, C. Y., and Nusse, R. (2004) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 20 781–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.He, X., Semenov, M., Tamai, K., and Zeng, X. (2004) Development 131 1663–1677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wong, H. C., Bourdelas, A., Krauss, A., Lee, H. J., Shao, Y., Wu, D., Mlodzik, M., Shi, D. L., and Zheng, J. (2003) Mol. Cell 12 1251–1260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]