Abstract

Fcγ receptors (FcγR) and the C5a receptor (C5aR) are key effectors of the acute inflammatory response to IgG immune complexes (IC). Their coordinated activation is critical in IC-induced diseases, although the significance of combined signaling by these two different receptor classes in tissue injury is unclear. Here we used the mouse model of the passive reverse lung Arthus reaction to define their requirements for distinct phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) activities in vivo. We show that genetic deletion of class IB PI3Kγ abrogates C5aR signaling that is crucial for FcγR-mediated activation of lung macrophages. Thus, in PI3Kγ-/- mice, IgG IC-induced FcγR regulation, cytokine release, and neutrophil recruitment were blunted. Notably, however, C5a production occurred normally in PI3Kγ-/- mice but was impaired in PI3Kδ-/- mice. Consequently, class IA PI3Kδ deficiency caused resistance to acute IC lung injury. These results demonstrate that PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ coordinate the inflammatory effects of C5aR and FcγR and define PI3Kδ as a novel and essential element of FcγR signaling in the generation of C5a in IC disease.

Activated complement component C5a is a pleiotropic molecule that regulates the activity of many cell types, with a broad range of biological functions in the immune system (1). C5a binds to at least two seven-transmembrane domain receptors, C5aR4 (CD88) and C5L2, expressed on a variety of immune cells, including circulating leukocytes, mast cells, basophils, macrophages, and many others. C5aR-dependent activation of these cells by C5a results in inflammatory mediator release and granule secretion, which in turn alters vascular permeability, induces smooth muscle contraction, and promotes cell migration (2). It is well established that this C5a-triggered cascade of events contributes to the pathogenesis of various diseases in humans, including myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury and respiratory distress syndrome (3–5). In addition, genetic deletion of C5aR is very effective in preventing inflammation in animal models of type III hypersensitivity (as modeled by the passive reverse Arthus reaction) and arthritis, as well as antibody-dependent type II autoimmunity (6–8).

Complement activation occurs through multiple pathways (classical, alternative, and lectin binding) in the circulation, each of which produces C5a. Interestingly, C5a is also formed within the extravascular tissue compartments through activation of resident innate immune effector cells, such as tissue macrophages, and requires the presence of receptors for the Fc portion of IgG, FcγR (reviewed in Ref. 9). FcγR exert their function through paired expression of activating (FcγRI, FcγRIII, and FcγRIV) and inhibitory (FcγRIIB) receptors (reviewed in Refs. 10 and 11). Compelling evidence suggests that the ratio of the opposing signaling FcγR is critical in setting the cellular thresholds for the pathogenic activity of autoantibodies (reviewed in Refs. 10–12) and that C5a regulates this ratio, thus amplifying the FcγR-mediated inflammatory response in autoimmunity (8, 13–15).

Although C5a/C5aR and FcγR likely cooperate in the context of immunological diseases, the precise molecular mechanisms of their combined signaling remain to be elucidated. C5a/C5aR has recently been shown to induce and suppress transcription of the two FcγRIII and FcγRII genes on macrophages in a PI3K-dependent manner (16). In addition, PI3K-mediated signal transduction is also known for FcγR-induced cell activation (17). Distinct members of the PI3K family of signaling molecules may thus participate in the regulatory cross-talk between individual FcγR and C5aR, which was previously proposed to be a key event in the initiation of the inflammatory cascade in vivo (8, 9, 13, 14).

The PI3K family can be divided into three subfamilies (I, II, and III) on the basis of their structural characteristics, activation mechanisms, and substrate specificity. Class IA PI3K members are heterodimers consisting of a regulatory subunit (seven distinct isoforms including splice variants are known, which are derived from five genes: p85α, p85β, p55α, p55β, and p55γ) and a catalytic subunit (which is one of three types: p110α, p110β, and p110δ) (reviewed in Refs. 18–21). Whereas class IA PI3Kα and PI3Kβ are widely expressed, PI3Kδ is found primarily in cells of the immune system, where it is activated by receptors involved in protein-tyrosine kinase signaling, such as cytokine receptors, antigen receptors present on T and B cells, and the mast cell IgE Fc receptor, FcεRI (reviewed in Refs. 22–24). The only class IB PI3K enzyme, PI3Kγ, also consists of a catalytic (i.e. p110γ) and a regulatory (i.e. p101 or p87) subunit and is also preferentially expressed in immune cells (reviewed in Ref. 25). In contrast to PI3Kδ, however, class IB PI3Kγ is predominantly activated by G-protein-coupled receptors, such as C5aR.

Recent studies in mice lacking PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ (26–29) have revealed a key role of class I PI3K members in many cellular immune responses at the interface of innate and adaptive immunity. For instance, PI3Kγ deficiency leads to defects in chemokine-induced migration of neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells to sites of infection and tissue injury (27–30). Moreover, G-protein-coupled receptor-induced activation of mast cells and platelets is also affected in PI3Kγ-/- mice (31, 32), whereas PI3Kδ-/- mice show a severely impaired B cell response of antibody production to T cell-dependent and -independent antigens (26, 33–36).

In this study, we analyzed PI3Kγ-/- mice in the experimental model of the pulmonary Arthus reaction and found defective C5aR-mediated FcγR regulation and macrophage activation, leading to impaired induction of the inflammatory response. Notably, however, C5a production was not affected in PI3Kγ-/- mice, but was impaired in the genetic absence of PI3Kδ. Consequently, PI3Kδ-/- mice failed also to develop IC-induced inflammation, indicating that both PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ are critical linkers of coordinate C5aR-FcγR activation in IC disease.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice

The generation of B6 PI3Kγ- and PI3Kδ-deficient mice and their phenotypic characterization have been described previously in detail (26, 27). WT B6 mice were used for all comparisons. All mice were maintained under dry barrier conditions at the animal facilities of the Hanover Medical School and Heinrich-Heine University.

Passive Reverse Lung Arthus Reaction

Mice were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine; the trachea was cannulated; and 150 μg of protein G-purified anti-OVA IgG Ab (ICN) was applied. Immediately thereafter, 20 mg/kg OVA Ag was given intravenously. Ab control animals received phosphate-buffered saline instead of OVA Ag. In PI3K-blocking experiments, 2 μg of wortmannin (Calbiochem) was given intratracheally together with the application of anti-OVA IgG. Mice were killed at 2–4 h after initiation of lung inflammation. BAL was performed five times with 1 ml of 0.9% NaCl at 4 °C. The total cell count of BALF was assessed with a hemocytometer. The amount of red blood cells represented the degree of hemorrhage. For quantitation of PMN accumulation, differential cell counts were performed on Cytospins (10 min at 55 × g) stained with May-Grünwald/Giemsa using 300–500 μl of BALF. The concentrations of MIP-1α, MIP-2, KC, and TNFα in BALF were measured in duplicate in appropriately diluted samples with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

FcγR Expression Analysis in Vitro and in Vivo

Luciferase Reporter Gene Assays—The FcγR promoter-reporter plasmids FcγRII p(-729/+501)Luc and FcγRIII p(-808/+18)Luc (0.7 μg) were cotransfected with 0.3 μg of the reference plasmid pRL-CMV into 5 × 105 macrophage MH-S cells in 12-well plates using Lipofectamine™ as described (16). Cells were recovered after 24 h, cultured for 24 h in 1% fetal calf serum-containing RPMI 1640 medium, and further treated with 50 ng of recombinant human C5a for 4 h. In some experiments, cells were pretreated for 1 h with an anti-C5aR Ab to block C5aR activity. In PI3K inhibition experiments, wortmannin (20 μm) and a PI3Kγ-specific inhibitor (5-quinoxalin-6-ylmethylenethiazolidine-2,4-dione, 10 nm; Calbiochem) were used. The Src kinase inhibitor PP2, which does not inhibit C5aR signaling (16), served as a negative control. Cells were then lysed and measured for luciferase activities using the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay system (Promega). Firefly luciferase activity was normalized by Renilla luciferase activity to yield the relative promoter activity.

Real-time RT-PCR—Total RNA was prepared from BAL-AM cells of the indicated mice at 0 and 2 h after C5a treatment (intratracheal application of 200 ng of recombinant human C5a) using TRIzol reagent and analyzed for FcγRII, FcγRIII, and FcRγ transcript levels normalized to tubulin by real-time RT-PCR using published primers (8, 13).

Fluorescence-activated Cell Sorter Analysis—Surface FcγRIII expression on BAL-AM cells (2 × 104) obtained from 4-h IgG IC-treated mice was analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACScan flow cytometer and anti-FcγRIII mAb 275003 (R&D Systems) conjugated to Alexa 647. To analyze FcγRII protein expression, BAL-AM cells were first treated with saturating doses of unlabeled mAb 275003, followed by phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-FcγRII/III mAb 2.4G2 staining as described (14, 37).

C5/C5a Analysis

Real-time RT-PCR—Total RNA was prepared from BAL-AM cells of mice at 2 h after Ab and IC treatments and analyzed for C5 transcription by real-time RT-PCR as described (8).

Detection of C5a-dependent Chemotactic Activity in Vivo—Bone marrow cells (containing 64–68% PMN) from C5aR-deficient mice or B6 controls were suspended at 7.5 × 106 cells/ml of RPMI 1640 medium and 0.1% bovine serum albumin (fatty acid-free). 100 μl of the bone marrow cell suspension was placed into the insert of a Transwell chemotaxis chamber, and the bottom well was filled with 600 μl of RPMI 1640 medium and 0.1% bovine serum albumin (negative control) or BALF diluted 1:2 in RPMI 1640 medium and 0.1% bovine serum albumin. BALF was obtained from PI3Kγ-/- and PI3Kδ-/- mice, wortmannin-treated B6 mice, or WT controls at 2–4 h after OVA/anti-OVA IC inflammation. BALF from mice receiving Ab but not OVA Ag served as controls. Inserts were combined in the lower chambers and incubated at 37 °C and 6% CO2 for 2 h. After the incubation, 50 μl of 70 mm EDTA was added to the lower chambers to release adherent cells from the lower surface of the membrane and from the bottom of the well. Plates were further incubated for 30 min at 4 °C; inserts were removed; and the transmigrated neutrophils were vigorously suspended and counted with a FACSCalibur for 1 min at 12 μl/min with gating on forward and side scatter. Migration of PMN from the insert to the bottom well was quantitated as the percentage of total PMN loaded into the upper chamber.

Statistical Analysis

Data for comparison of mean values among samples were analyzed by a two-sided unpaired Student's t test.

RESULTS

In Vivo Effects of General PI3K Inhibition in IgG IC-induced Inflammation—To determine whether inhibition of PI3K signaling has a protective effect on IgG IC inflammation, we conducted lung Arthus experiments in mice receiving wortmannin, a general PI3K inhibitor. Assessment of lung inflammation at 4 h revealed that local intratracheal application of 2 μg of wortmannin suppressed alveolar PMN influx, hemorrhage, and chemotactic activity in IgG IC-challenged B6 mice (Fig. 1, A–C). In addition, PI3K inhibition resulted in strong reduction of IC-induced mediator production of CXC chemokines (MIP-2 and KC), MIP-1α, and TNFα (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1, D–F). These data indicate that PI3K activity is required for the generation of crucial inflammatory mediators in the initiation of acute IC inflammation, thus confirming previous observations on the key role of PI3K in other experimental models of immunological disease (reviewed in Refs. 38–41).

FIGURE 1.

Attenuation of IgG IC inflammation in mice receiving the general PI3K inhibitor wortmannin. Induction of the inflammatory response in the lung was performed by intratracheal application of 150 μg of purified anti-OVA IgG Ab, followed by systemic 20 mg/kg OVA Ag in WT B6 mice (IC) or WT mice treated with wortmannin (IC + wortm.). Mice receiving only anti-OVA Ab served as controls (Ab). After 4 h, lungs were lavaged. BALF was assayed for PMN infiltration (A); pulmonary hemorrhage (B); chemotactic activity (C); and production of CXC chemokines (MIP-2 and KC) (D), MIP-1α (E), and TNFα (F). Data are expressed as the means ± S.E. (n = five to eight mice for each group). Differences in IC compared with IC + wortmannin treatment groups are significant or highly significant for all parameters (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.001). RBC, red blood cells.

PI3Kγ-dependent Regulation of Macrophage FcγRII and FcγRIII in Vitro and in Vivo—C5a is a major regulator of FcγR with induction of activating FcγRIII and suppression of inhibitory FcγRII (13), thereby tuning FcγR-mediated release of PMN recruitment factors in lung IC inflammation (42). Previous studies also suggested abrogation of C5aR signaling and impaired FcγRIII-mediated functions in mice lacking Gαi2, a selective upstream regulator of PI3Kγ in macrophages (14), implicating a specific involvement of PI3Kγ in FcγR regulation by these cells. We have used three distinct experimental strategies to determine the potential role of the class IB PI3Kγ isoform in C5a- and IgG IC-induced FcγR regulation.

In the first approach, we performed in vitro reporter gene assays using the AM cell line MH-S and the recently characterized C5a-responsive FcγRII (-729 to +501) and FcγRIII (-808 to +18) gene promoters (16). Enhanced versus suppressed FcγRIII and FcγRII promoter activities in transfected MH-S cells were obtained by stimulating them with C5a for 4 h (Fig. 2A). The simultaneous positive and negative FcγRIII and FcγRII regulation was equally sensitive to inhibition with wortmannin or a PI3Kγ-selective inhibitor (5-quinoxalin-6-ylmethylenethiazolidine-2,4-dione) or an anti-C5aR mAb. As a negative control, the effect of PP2, an Src kinase inhibitor that does not interfere with C5aR signaling (16), was analyzed, and no inhibition was observed. In the second approach, we directly instilled 200 ng of C5a into the tracheas of WT B6 and PI3Kγ-/- mice and tested for in vivo changes of FcγR transcription in BAL-AM cells. As shown in Fig. 2B, both FcγRIIIα and FcγRIIIγ mRNA levels were up-regulated, whereas FcγRII transcription was suppressed within 2 h after application of C5a. This inverse regulation of FcγRII and FcγRIII was impaired in the absence of PI3Kγ (Fig. 2B). IC-induced FcγR mRNA (data not shown) and protein (Fig. 2C) regulation was also abrogated in PI3Kγ deficiency. In the third approach, AM cells were collected at 0 and 4 h after IgG IC challenge and analyzed by flow cytometry as described (13). Fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis revealed IC-induced changes in increased staining of FcγRIII (0-h versus 4-h groups, 297 ± 71 versus 912 ± 33 mean fluorescence intensity ± S.E.; p = 0.039) and reduced staining of FcγRII (0-h versus 4-h groups, 424 ± 37 versus 191 ± 23 mean fluorescence intensity ± S.E.; p = 0.049) in WT B6 mice, indicating that the observed changes in FcγR mRNA (13, 14) correlate with modulated FcγRII/III surface membrane expression. However, regulation of FcγR, which requires C5aR (13), was absent in PI3Kγ-/- mice (Fig. 2C). Collectively, these data indicate that PI3Kγ regulates FcγR expression in response to C5aR activation in vitro and in vivo.

FIGURE 2.

PI3Kγ-dependent FcγR regulation in vitro and in vivo. A, shown are the relative promoter activities after 48 h of transfection of FcγRIII p(-808/+18)Luc (left panel) and FcγRIIB p(-729/+501)Luc (right panel) into MH-S cells stimulated for 4 h with C5a and treated with the indicated cell-permeable inhibitors (PP2, inhibitor of Src kinases; wortmannin, a general PI3K inhibitor; and PI3Kγ inhibitor 5-quinoxalin-6-ylmethylenethiazolidine-2,4-dione, a selective inhibitor of class IB PI3Kγ) or a neutralizing anti-C5aR mAb. Results represent the means ± S.E. of three independent transfections performed in duplicate. Differences between native (medium) and C5a-induced (C5a) levels of FcR promoter activities are significant (§, p < 0.05). Differences in C5a compared with C5a + wortmannin, C5a + PI3Kγ inhibitor, and C5a + anti-C5aR antibody treatment groups are significant (*, p < 0.05). B, BAL-AM cells were isolated from WT and PI3Kγ-/- mice at 0 h (gray bars) and 2 h (black bars) after intratracheal instillation of recombinant human C5a. Real-time RT-PCR analysis revealed increased FcγRIIIα (left panel) and FcγRIIIγ (middle panel) and reduced FcγRII (right panel) mRNAs in WT mice but not in BAL-AM cells of PI3Kγ-/- mice following recombinant human C5a treatment. Results are shown as the means ± S.E. (n = three to four mice for each group). Significant differences were determined by Student's t test (*, p < 0.05). AU, arbitrary units. C, flow cytometric analysis was performed with BAL-AM cells obtained from 0-h (gray bars) and 4-h (black bars) IC-challenged WT and PI3Kγ-/- mice. Both representative (left panels) and quantitative (right panels) results are shown. The quantitative results are expressed as the x-fold change in mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) ± S.E. Differences in 0-h IC compared with 4-h IC treatment groups are significant (*, p < 0.05).

Impaired IC Inflammation but Normal C5a in PI3Kγ-deficient Mice—Because PI3Kγ is an apparent critical mediator of both in vivo responses to C5a- and IC-induced FcγR modulation, we then asked whether PI3Kγ not only affects the expression level of FcγR but also regulates the subsequent FcγR-mediated production of factors that dictate PMN migration in lung disease. Whereas TNFα induces expression of adhesion molecules, thus promoting PMN migration more indirectly, MIP-2 and MIP-1α represent direct recruitment factors for PMN (42, 43). Both PMN influx and hemorrhage were blunted in PI3Kγ deficiency (Fig. 3, A and B), and IC-induced release of all mediators tested (MIP-2, MIP-1α, and TNFα) and KC (data not shown) was decreased to background levels (Fig. 3, D–F). Curiously, however, the chemotactic activity of BALF from IC-treated PI3Kγ-/- mice showed only partial reduction (Fig. 3C), indicating that most, but not all, acute changes associated with the lung Arthus reaction were dependent on PI3Kγ.

FIGURE 3.

Impaired IC inflammation in PI3Kγ-deficient B6 mice. WT B6 and PI3Kγ-/- mice received 150 μg of anti-OVA Ab intratracheally and 20 mg/kg OVA Ag intravenously, and the inflammatory response in the lung was allowed to proceed for 4 h (IC). Mice not receiving OVA Ag served as Ab controls (Ab). Lungs were lavaged. PMN influx in the alveolar space (A); hemorrhage (B); chemotactic activity (C); and production of MIP-2 (D), MIP-1α (E), and TNFα (F) were evaluated. The results are expressed as the means ± S.E. (n = four to nine mice for each group). Differences in IC treatment groups of WT mice compared with PI3Kγ-/- mice are significant or highly significant for all parameters (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.001). RBC, red blood cells.

We have previously shown that IC activation of lung macrophages by FcγR triggers C5a production both in vitro and in vivo (14). To test the possibility that cell-derived C5a might be responsible for the remaining chemotactic activity seen in PI3Kγ-/- mice, BALF from both PI3Kγ-/- and wortmannin-treated mice was analyzed for C5a activity by Transwell chemotaxis assays using bone marrow PMN cells from C5aR-/- mice. The difference in the percentage of C5aR-/- and C5aR+/+ PMN indicated the presence of bioactive C5a. In contrast to BALF from PI3Kγ-deficient animals (Fig. 4A), the C5a-dependent chemotactic activity detected in BALF of 4-h IC-treated WT mice was markedly suppressed upon PI3K inhibition (Fig. 4B), suggesting that generation of C5a critically involves a PI3K activity, which, however, is not related to PI3Kγ.

FIGURE 4.

Different effects of general PI3K inhibition and PI3Kγ deficiency on IC-induced C5a production. Pulmonary 4-h IC inflammation was induced in the indicated mice (WT and PI3Kγ-/-; A) (WT treated or not with wortmannin (wortm.); B), and BALF was assayed for C5a bioactivity (IC and IC + wortm.). Controls received anti-OVA Ab without OVA Ag (Ab). Chemotactic activity was determined by Transwell migration assays of neutrophils (PMN isolated from bone marrow of C57BL/6 and C5aR-/- mice) elicited with 300 μl of BALF from the Ab, IC, and IC + wortmannin treatment groups. Results are expressed as the percentage of PMN number loaded into the upper chamber that had migrated to the bottom well (mean ± S.E., n = four to nine mice for each group). Differences in the BALF-induced migration of C57BL/6 and C5aR-/- PMN represent bioactive C5a. Significant differences were determined by Student's t test (**, p < 0.001).

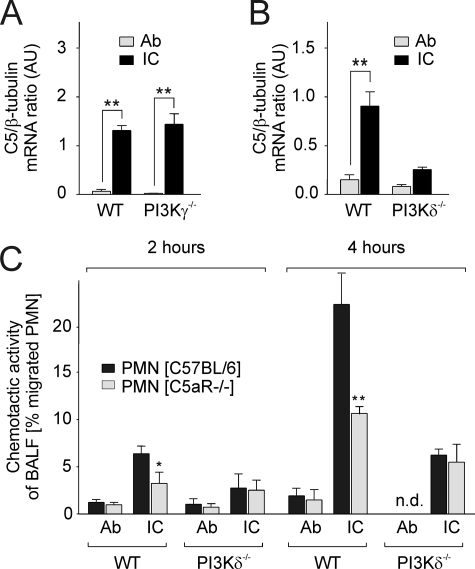

PI3Kδ-dependent C5/C5a in IC Inflammation—Because macrophages normally coexpress class IA PI3Kδ and class IB PI3Kγ (25) (data not shown), we analyzed PI3Kδ-/- mice to determine the possible contribution of PI3Kδ to the production of C5/C5a in IC inflammation. At 2 h after IgG IC challenge, BAL-AM cells displayed increased C5 mRNA synthesis in WT mice (p < 0.001 compared with Ab controls) (Fig. 5A). In contrast to both WT and PI3Kγ-/- mice (Fig. 5A), C5 mRNA levels remained largely unchanged in AM cells of IC-treated PI3Kδ-/- mice (Fig. 5B). To examine whether the changes in PI3Kδ-dependent C5 gene induction correlate with release of C5a in acute lung injury, BALF from WT and PI3Kδ-/- mice was assayed for the appearance of C5a. In contrast to BALF from WT littermates, C5a-dependent chemotactic activity detected in BALF from 2- and 4-h IC-treated PI3Kδ-/- mice was strongly decreased (Fig. 5C), indicating that PI3Kδ mediates generation of C5 and C5a by macrophages in lung IC inflammation.

FIGURE 5.

Impaired C5/C5a production in PI3Kδ-/- mice. At 2–4 h following OVA/anti-OVA (IC) and anti-OVA (Ab) challenge in PI3Kγ-/- or PI3Kδ-/- mice or their WT controls, lungs were lavaged and assayed for cellular C5 mRNA expression by real-time RT-PCR (A and B), and C5a-mediated C5aR-triggered chemotactic activity of BALF was determined by Transwell migration assays of neutrophils (PMN isolated from bone marrow of C57BL/6 and C5aR-/- B6 mice) (C). Results are shown as the means ± S.E. (n = four to seven mice for each group). Significant differences were determined by Student's t test (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.001). AU, arbitrary units; n.d., not determined.

Impaired IC Inflammation in PI3Kδ-/- Mice—In C5-defective Hc-/- mice, it has been shown that IC-mediated cytokine production depends on C5a (43), so we finally assessed the biological relevance of PI3Kδ-mediated C5a to the release of cytokines and chemokines as well as hemorrhage and neutrophil infiltration. The impaired production of C5a in PI3Kδ-/- mice (Fig. 5) seemed to correlate with reduced TNFα and MIP-2 mRNA levels in AM cells at 2 h of IC challenge compared with WT mice (data not shown), decreased appearance of these mediators in BALF (at 4 h) (Fig. 6, A and B), reduced synthesis of KC and MIP-1α (Fig. 6, C and D), and significantly lower levels of red blood cells (Fig. 6E) and PMN (Fig. 6F) in alveoli. Taken together, our results support a model of IC inflammation in which the cellular communication of FcγR and C5aR is coordinated by distinct class I PI3K members in the initiation of the inflammatory cascade (Fig. 7).

FIGURE 6.

Impaired IC inflammation in PI3Kδ-deficient B6 mice. WT B6 and PI3Kδ-/- mice received 150 μg of anti-OVA Ab intratracheally and 20 mg/kg OVA Ag intravenously, and the inflammatory response in the lung was allowed to proceed for 4 h (IC). Mice not receiving OVA Ag served as Ab controls (Ab). Lungs were lavaged, and BALF was assayed for production of MIP-2 (A), TNFα (B), KC (C), and MIP-1α (D); PMN infiltration (E); and pulmonary hemorrhage (F). Data are expressed as the means ± S.E. (n = four to seven mice for each group). Differences for the IC treatment groups of WT mice compared with PI3Kδ-/- mice are highly significant for all parameters (**, p < 0.001). RBC, red blood cells.

FIGURE 7.

Summarized model of the alternative roles of the two class I PI3K members (PI3Kγ and PI3Kδ) in IC inflammation. As discussed under “Results,” the initial contact between IgG IC and AM cells causes induction of C5 and cleavage into C5a that is PI3Kδ-dependent. Engagement of C5aR by such PI3Kδ-mediated C5a triggers PI3Kγ activation, resulting in regulated FcγR expression, induced cytokine/chemokine production, and, in turn, neutrophil inflammation.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have analyzed the role of class IA and IB PI3K signaling molecules in the Arthus reaction, the classical animal model of IC disease. Genetic deletion of PI3Kγ completely abolishes the inflammatory cascade with respect to C5aR-mediated FcγR regulation and subsequent cytokine/chemokine production, hemorrhage, and alveolar PMN transmigration, indicating that PI3Kγ is the pivotal downstream mediator of C5aR through which the C5aR-FcγR axis (13, 14) controls early neutrophil accumulation in the bronchoalveolar compartment. These data significantly extend previous findings that provided evidence for a role of PI3Kγ in PMN movement in chemokine-induced lung neutrophilia in vivo (44). Moreover, they support the concept that, in the complex situation of an inflammatory disease, a major function of the G-protein-regulated PI3Kγ is to transmit early C5aR-triggered signals in macrophages, thereby promoting a shift in the receptor balance between activating FcγRIII and inhibiting FcγRII that is essentially required for the recruitment of neutrophils via FcγR-mediated synthesis of various secondary mediators (including MIP-2, KC, MIP-1α, and TNFα). In addition, our analysis of general PI3K inhibition versus selective PI3Kγ deficiency also implicates the participation of an additional PI3K in the generation of a full chemotactic gradient that requires C5a.

PI3Kδ is the most prevalent class IA PI3K isoform in leukocytes and controls a wide range of distinct immunological responses, such as antigen presentation, cytokine and chemokine secretion by natural killer/T cells, Th2-mediated inflammation, and many others (45–50). An important new mechanistic aspect of this study is the finding that PI3Kδ plays a non-redundant role in the initial phase of the lung Arthus reaction with a specific requirement of PI3Kδ for C5a production upstream of C5aR and PI3Kγ. As a consequence of impaired C5a, PI3Kδ-/- mice exhibit reduced cytokine production and PMN migration, suggesting that macrophage PI3Kδ is important for neutrophil recruitment in the initiation of the inflammatory response. A recent study in C5-defective Hc-/- mice has concluded that activation of C5 is central to the inflammatory reaction in IC-mediated disease (43). We found a similar protective phenotype in PI3Kδ deficiency, thus indicating that cellular activation of PI3Kδ is the relevant C5/C5a-generating mechanism in lung pathology. It is important to note, however, that it is at present not clear whether, in addition to macrophages, other cell types are involved in the PI3Kδ-mediated process of C5a production.

In summary, PI3Kγ-/- and PI3Kδ-/- mice allowed dissection of the signaling mechanisms of two major cooperating receptor systems, C5aR and FcγR, in immune inflammation. The results suggest that the different receptors have distinct PI3Kγ- and PI3Kδ-specific requirements. PI3Kγ is the central player in C5aR signaling that sets the threshold for FcγR activation. Conversely, both FcγR (8, 14) and PI3Kδ are critical for local C5 and C5a production. Our observations also indicate that the two class IA and IB PI3K molecules might be essential components of the immune response to pathogenic IC and, as recently discussed for rheumatoid arthritis (41, 51), may represent potential molecular targets for pharmacological intervention in inflammatory and rheumatic autoimmune diseases.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to J. Ihle for kindly providing PI3Kδ-/- mice.

This work was supported in part by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grants SFB 587 (to J. E. G.) and FOR 729 (to B. N.) and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: C5aR, C5a receptor(s); FcγR, Fcγ receptor(s); PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; IC, immune complex(es); WT, wild-type; OVA, ovalbumin; Ab, antibody; Ag, antigen; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; BALF, BAL fluid; PMN, polymorphonuclear leukocyte(s); MIP, macrophage inflammatory protein; KC, cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor-α; RT, reverse transcription; AM, alveolar macrophage; mAb, monoclonal Ab.

References

- 1.Volanakis, J. E., and Frank, M. M. (1998) The Human Complement System in Health and Disease, Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York

- 2.Monk, P. N., Scola, A.-M., Madala, P., and Fairlie, D. P. (2007) Br. J. Pharmacol. 152 429-448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vakeva, A. P., Agah, A., Rollins, S. A., Matis, L. A., and Stahl, G. L. (1998) Circulation 97 2259-2267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fitch, J. C., Rollins, S., Matis, L., Alford, B., Aranki, S., Collard, C. D., Dewar, M., Elefteriades, J., Hines, R., Kopf, G., Kraker, P., Li, L., O'Hara, R., Rinder, C., Rinder, H., Shaw, R., Smith, B., Stahl, G., and Shernan, S. K. (1999) Circulation 100 2499-2506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevens, J. H., O'Hanley, P., Shapiro, J. M., Mihm, F. G., Satoh, P. S., Collins, J. A., and Raffin, T. A. (1986) J. Clin. Investig. 77 1812-1816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Höpken, U. E., Lu, B., Gerard, N. P., and Gerard, C. (1997) J. Exp. Med. 186 749-756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ji, H., Ohmura, K., Mahmood, U., Lee, D. M., Hofhuis, F. M., Boackle, S. A., Takahashi, K., Holers, V. M., Walport, M., Gerard, C., Ezekowitz, A., Carroll, M. C., Brenner, M., Weissleder, R., Verbeek, J. S., Duchatelle, V., Degott, C., Benoist, C., and Mathis, D. (2002) Immunity 16 157-168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar, V., Ali, S. R., Konrad, S., Zwirner, J., Verbeek, J. S., Schmidt, R. E., and Gessner, J. E. (2006) J. Clin. Investig. 116 512-520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmidt, R. E., and Gessner, J. E. (2005) Immunol. Lett. 100 56-67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ravetch, J. V., and Bolland, S. (2001) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19 275-290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nimmerjahn, F., and Ravetch, J. V. (2006) Immunity 24 19-28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takai, T. (2002) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2 580-592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shushakova, N., Skokowa, J., Schulman, J., Baumann, U., Zwirner, J., Schmidt, R. E., and Gessner, J. E. (2002) J. Clin. Investig. 110 1823-1830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skokowa, J., Ali, S. R., Felda, O., Kumar, V., Konrad, S., Shushakova, N., Schmidt, R. E., Piekorz, R. P., Nürnberg, B., Spicher, K., Birnbaumer, L., Zwirner, J., Claassens, J. W. C., Verbeek, J. S., van Rooijen, N., Köhl, J., and Gessner, J. E. (2005) J. Immunol. 174 3041-3050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Radeke, H. H., Janssen-Graalfs, I., Sowa, E. N., Chouchakova, N., Skokowa, J., Loscher, F., Schmidt, R. E., Heeringa, P., and Gessner, J. E. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 27535-27544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Konrad, S., Engling, L., Schmidt, R. E., and Gessner, J. E. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 37906-37912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Canetti, C., Serezani, C. H., Atrasz, R. G., White, E. S., Aronoff, D. M., and Peters-Golden, M. (2007) J. Immunol. 179 8350-8356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wymann, M. P., and Pirola, S. (1998) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1436 127-150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fruman, D. A., Meyers, R. E., and Cantley, L. C. (1998) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67 481-507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piekorz, R. P., and Nürnberg, B. (2004) Phospholipid Kinases, Elsevier Science Publishing Co., Inc., New York

- 21.Katso, R., Okkenhaug, K., Ahmadi, K., White, S., Timms, J., and Waterfield, M. D. (2001) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 17 615-675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okkenhaug, K., and Vanhaesebroeck, B. (2003) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31 270-274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kinet, J.-P. (1999) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17 931-972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fruman, D. A., and Cantley, L. C. (2002) Semin. Immunol. 14 7-18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koyasu, S. (2003) Nat. Immunol. 4 313-319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jou, S. T., Carpino, N., Takahashi, Y., Piekorz, R., Chao, J. R., Carpino, N., Wang, D., and Ihle, J. N. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22 8580-8591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sasaki, T., Irie-Sasaki, J., Jones, R. G., Oliveira-dos-Santos, A. J., Stanford, W. L., Bolon, B., Wakeham, A., Itie, A., Bouchard, D., Kozieradzki, I., Joza, N., Mak, T. W., Ohashi, P. S., Suzuki, A., and Penninger, J. M. (2000) Science 287 1040-1046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li, Z., Jiang, H., Xie, W., Zhang, Z., Smrcka, A. V., and Wu, D. (2000) Science 287 1046-1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirsch, E., Katanaev, V. L., Garlanda, C., Azzolino, O., Pirola, L., Silengo, L., Sozzoni, S., Mantovani, A., Altruda, F., and Wymann, M. P. (2000) Science 287 1049-1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Del Prete, A., Vermi, W., Dander, E., Otero, K., Barberis, L., Luini, W., Bernasconi, S., Sironi, M., Santoro, A., Garlanda, C., Facchetti, F., Wymann, M. P., Vecchi, A., Hirsch, E., Mantovani, A., and Sozzoni, S. (2004) EMBO J. 23 3505-3515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laffargue, M., Calvez, R., Finan, P., Trifilieff, A., Barbier, M., Altruda, F., Hirsch, E., and Wymann, M. P. (2002) Immunity 16 441-451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lian, L., Wang, Y., Draznin, J., Eslin, D., Bennett, J. S., Poncz, M., Wu, D., and Abrams, C. S. (2005) Blood 106 110-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okkenhaug, K., Bilancio, A., Farjot, G., Priddle, H., Sancho, S., Peskett, E., Pearce, W., Meek, S. E., Salpekar, A., Waterfield, M. D., Smith, A. J., and Vanhaesebroeck, B. (2002) Science 297 1031-1034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clayton, G., Bardi, G., Bell, S. E., Chantry, D., Downes, C. P., Gray, A., Humphries, L. A., Rawlings, D., Reynolds, H., Vigorito, E., and Turner, M. (2002) J. Exp. Med. 196 753-763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fruman, D. A., Snapper, S. B., Yballe, C. M., Davidson, L., Yu, J. Y., Alt, F. W., and Cantley, L. C. (1999) Science 283 393-397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suzuki, H., Terauchi, Y., Fujiwara, M., Aizawa, S., Yazaki, Y., Kadowaki, T., and Koyasu, S. (1999) Science 283 390-392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schiller, C., Janssen-Graalfs, I., Baumann, U., Schwerter-Strumpf, K., Izui, S., Takai, T., Schmidt, R. E., and Gessner, J. E. (2000) Eur. J. Immunol. 30 481-490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marone, R., Cmiljanovic, V., Giese, B., and Wymann, M. P. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1784 159-185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barberis, L., and Hirsch, E. (2008) Thromb. Haemostasis 99 279-285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Medina-Tato, D. A., Ward, S. G., and Watson, M. L. (2007) Immunology 121 448-461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rommel, C., Camps, M., and Ji, H. (2007) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7 191-2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chouchakova, N., Skokowa, J., Baumann, U., Tschernig, T., Philippens, K. M. H., Nieswandt, B., Schmidt, R. E., and Gessner, J. E. (2001) J. Immunol. 166 5193-5200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huber-Lang, M., Sarma, J. V., Zetoune, F. S., Rittirsch, D., Neff, T. A., McGuire, S. R., Lambris, J. D., Warner, R. L., Flierl, M. A., Hoesel, L. M., Gebhard, F., Younger, J. G., Drouin, S. M., Wetsel, R. A., and Ward, P. A. (2006) Nat. Med. 12 682-687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thomas, M. J., Smith, A., Head, D. H., Milne, L., Nicholls, A., Pearce, W., and Vanhaesebroeck, B. (2005) Eur. J. Immunol. 35 1283-1291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Al-Alwan, M. M., Okkenhaug, K., Vanhaesebroeck, B., Hayflick, J. S., and Marshall, A. J. (2007) J. Immunol. 178 2328-2333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim, N., Saudemont, A., Webb, L., Camps, M., Ruckle, T., Hirsch, E., Turner, M., and Colucci, F. (2007) Blood 110 3202-3208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ji, H., Rintelen, F., Waltzinger, C., Bertschy Meier, D., Bilancio, A., Pearce, W., Hirsch, E., Wymann, M. P., Rückle, T., Camps, M., Vanhaesebroeck, B., Okkenhaug, K., and Rommel, C. (2007) Blood 110 2940-2947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nashed, B. F., Zhang, T., Al-Alwan, M., Srinivasan, G., Halayko, A. J., Okkenhaug, K., Vanhaesebroeck, B., Hayglass, K. T., and Marshall, A. J. (2007) Eur. J. Immunol. 37 416-424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ali, K., Bilancio, A., Thomas, M., Pearce, W., Gilfillan, A. M., Tkaczyk, C., Kuehn, N., Gray, A., Giddings, J., Peskett, E., Fox, R., Bruce, I., Walker, C., Sawyer, C., Okkenhaug, K., Finan, P., and Vanhaesebroeck, B. (2004) Nature 431 1007-1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Puri, K. D., Doggett, T. A., Douangpanya, J., Hou, Y., Tino, W. T., Wilson, T., Graf, T., Clayton, E., Turner, M., Hayflick, J. S., and Diacovo, T. G. (2004) Blood 103 3448-3456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Randis, T. M., Puri, K. D., Zhou, H., and Diacovo, T. G. (2008) Eur. J. Immunol. 38 1215-1224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]