Abstract

Polyglutamine expansions of huntingtin protein are responsible for the Huntington neurological disorder. HIP14 protein has been shown to interact with huntingtin. HIP14 and a HIP14-like protein, HIP14L, with a 69% similarity reside in the Golgi and possess palmitoyl acyltransferase activity through innate cysteine-rich domains, DHHC. Here, we used microarray analysis to show that reduced extracellular magnesium concentration increases HIP14L mRNA suggesting a role in cellular magnesium metabolism. Because HIP14 was not on the microarray platform, we used real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR to show that HIP14 and HIP14L transcripts were up-regulated 3-fold with low magnesium. Western analysis with a specific HIP14 antibody also showed that endogenous HIP14 protein increased with diminished magnesium. Furthermore, we demonstrate that when expressed in Xenopus oocytes, HIP14 and HIP14L mediate Mg2+ uptake that is electrogenic, voltage-dependent, and saturable with Michaelis constants of 0.87 ± 0.02 and 0.74 ± 0.07 mm, respectively. Diminished magnesium leads to an apparent increase in HIP14-green fluorescent protein and HIP14L-green fluorescent fusion proteins in the Golgi complex and subplasma membrane post-Golgi vesicles of transfected epithelial cells. We also show that inhibition of palmitoylation with 2-bromopalmitate, or deletion of the DHHC motif HIP14ΔDHHC, diminishes HIP14-mediated Mg2+ transport by about 50%. Coexpression of an independent protein acyltransferase, GODZ, with the deleted HIP14ΔDHHC mutant restored Mg2+ transport to values observed with wild-type HIP14. Although we did not directly measure palmitoylation of HIP14 in these studies, the data are consistent with a regulatory role of autopalmitoylation in HIP14-mediated Mg2+ transport. We conclude that the huntingtin interacting protein genes, HIP14 and HIP14L, encode Mg2+ transport proteins that are regulated by their innate palmitoyl acyltransferases thus fulfilling the characteristics of “chanzymes.”

Huntington disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder caused by an expansion of the CAG repeat in the huntingtin gene that confers an expanded polyglutamine (poly(Q)) stretch in the huntingtin protein (1). The function of the huntingtin protein is unclear but it interacts with many cytoskeletal and synaptic vesicle proteins that are essential for exocytosis and endocytosis (2–5). One of the interacting proteins identified by the yeast two-hybrid system is huntingtin-interacting protein 14, HIP14 (1). A related protein, HIP14-like (HIP14L), which has 69% homology to HIP14, was identified with an in silico data base search (1). As with huntingtin protein, HIP14 and HIP14L are evolutionary conserved and widely distributed among tissues. Whereas huntingtin is normally located on plasma and intracellular membranes and is associated with cytoplasmic vesicles and different organelles such as the Golgi, HIP14 appears to be primarily located in the Golgi and post-Golgi vesicles (2).

The functions of HIP14 are beginning to be clarified. The HIP14 secondary structure contains five predicted transmembrane domains that is reminiscent of a membrane receptor or transporter and possesses a cytoplasmic DHHC cysteine-rich domain defined by the Asp-His-His-Cys sequence motif (6). The DHHC region confers palmitoyl acyltransferase activity giving it the ability to modify membranes by palmitoylation (6–8). The presence of palmitate within the membrane protein affects how it interacts with lipid rafts and other membrane proteins (7). Palmitoylation by protein acyltransferases and depalmitoylation by acylprotein thioesterases regulate trafficking between membrane compartments and leading finally to protein degradation (7). Recently, Yanai et al. (9) reported that palmitoylation of huntingtin protein by HIP14 is important for its trafficking and function. Mutant huntingtin results in lower interaction with HIP14 and reduced palmitoylation that contribute to the formation of protein aggregates and enhanced neural toxicity.

Magnesium is the second most abundant cation within the cell and plays an important role in many intracellular biochemical functions (10). Despite the abundance and importance of magnesium, little is known about how eucaryotic cells regulate their magnesium content. Intracellular free Mg2+ concentration is in the order of 0.5 mm that comprises 1–2% of the total cellular magnesium (11). Accordingly, intracellular Mg2+ is maintained below the concentration predicted from the transmembrane electrochemical potential. Intracellular Mg2+ concentration is finely regulated likely by precise controls of Mg2+ entry, Mg2+ efflux, and intracellular Mg2+ storage compartments (11). We have shown that Mg2+ entry is through specific and regulated magnesium pathways that are regulated by intrinsic mechanisms such that culture of cells in media containing low magnesium results in up-regulation of Mg2+ uptake into the cells. These data suggest that epithelial cells can sense the environmental magnesium and through transcription- and translation-dependent processes modulate Mg2+ transport and maintain magnesium balance.

In an attempt to identify genes underlying cellular changes resulting from adaptation to low extracellular magnesium, we used oligonucleotide microarray analysis to screen for magnesium-regulated transcripts in epithelial cells (12). One transcript, HIP14L, was significantly up-regulated by low extracellular magnesium suggesting that the synthesis was regulated by changes in cell magnesium. Real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR showed that both HIP14 and HIP14L transcripts and Western analysis showed that endogenous HIP14 protein was responsive to changes in magnesium concentration. As the predicted secondary structures of HIP14 and HIP14L amino acid sequences conformed to prototypic membrane transporters, the goal of the present study was to see if the encoded HIP14 and HIP14L proteins mediate Mg2+ transport. We used both electrophysiological and fluorescence studies to examine Mg2+ transport in HIP14- and HIP14L-expressing Xenopus laevis oocytes. Cellular distribution and subcellular localization of HIP14-GFP2 and HIP14L-GFP were determined by immunofluorescence microscopy in transfected MDCK and COS-7 cells. Furthermore, distribution of the fusion proteins were evaluated in response to changes in cellular magnesium. Our data indicates that HIP14 and HIP14L proteins mediate Mg2+ transport and the transcripts are regulated by magnesium, indicating that they might play a role in control of cellular magnesium homeostasis. Furthermore, HIP14-mediated Mg2+ transport is regulated by autopalmitoylation through its inherent palmitoyl acyltransferase activity making this an unique membrane transport system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Oligonucleotide Microarray Analysis—Microarray analysis was performed according to the protocol recommended by Affymetrix (www.affymetric.com) using MG U74 Bv2 and MG U74 Cv2 arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) as described previously (12). DNA fragments representing transcripts that were up-regulated with low magnesium were selected and prioritized according to properties characteristic of membrane transport proteins.

Construction of Expression Vectors Encoding HIP14 and HIP14L—Mouse Hip14L cDNA was purchased from RIKEN number 2410004E01Rik. Human HIP14-GFP, hHIP14L, hHIP14ΔDHHC-GFP, and GODZ-FLAG constructs were gifts from Dr. Alaa El-Husseini (2). HIP14 and HIP14L constructs were in the pCI-neo vector.

Sequence Analysis—The HIP14 and HIP14L cDNA sequences were determined by standard methods. The full-length amino acid sequences are in the GenBank™ data base (HIP14 accession human NP_056151, mouse NP_766142 and HIP14L, also termed HIP14-related or HIP14R, human BC056152, and mouse NM_028031). Protein motifs were identified using BLASTP and the SWISSPROT data base. Membrane topology was predicted by the SOSUI program based on Kyte-Doolittle hydrophobicity analysis.

Quantitative Analysis of Hip14 and Hip14L Transcripts by Real-time Reverse Transcriptase-PCR—Total cell RNA was extracted by TRIzol (Invitrogen). Genomic DNA contamination was removed by the DNA-free™ kit (Ambion) prior to making first strand cDNA. Standard curves were constructed by serial dilution of a linear pGEM-T vector (Promega) containing the Hip14 and Hip14L genes. The primer set of mouse Hip14 was: forward, 5′-AGCATGCAGCGGGAGGAGG-3′ and reverse, 5′-CAATGGAGGAGGGTAACA-3′ and Hip14L was forward, 5′-CCGAAATGCTAAGGGAGAA-3′ and reverse, 5′-TCTCTGCTAGGGTGACGAT-3′. PCR products were quantified continuously with AB7000™ (Applied Biosystems) using SYBR Green™ fluorescence according to the manufacturer's instructions. The relative amounts of RNA were normalized to mouse β-actin transcripts.

Western Blot Analysis of Endogenous Hip14 Protein—Polyclonal rabbit HIP14 antibody was generated by Singaraja et al. (1), commercialized and subsequently purchased from Sigma. Cells were suspended in lysis buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS) containing protease inhibitors (1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, 2 μg/ml aprotinin). The homogenates were pelleted at 1,000 rpm (75 × g) for 10 min and the supernatant and pellet fractions sampled. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay reagent. SDS-PAGE was performed according to Laemmli (49). For immunoblotting, the proteins were electrophoretically transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Hybond®, Amersham Biosciences) by semidry electroblotting for 80 min. Western analysis was performed by incubating the blots with anti-HIP14 antibody overnight at 4 °C followed by three washes with PBS, 0.1% Tween 20, 10 min each. The blots were then incubated with 1/5,000 horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit secondary (Sigma) antibody for 1 h. After washing three times with PBS/Tween-20, 10 min each, the blots were visualized with ECL (Amersham Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Hip14 protein was normalized to GAPDH prepared from the respective cell preparations. Cell preparations were incubated with mouse “α-GAPDH antibody (Sigma) diluted 1/5,000 in PBS, 1% BSA for 2 h and subsequently with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat secondary antibody at 1/10,000 in PBS, 1% BSA for 1 h to quantitate the GAPDH.

Expression of Human HIP14 and HIP14L cRNAs in Xenopus Oocytes and Characterization of Mg2+ Transport—For Xenopus oocyte expression, cRNA was synthesized from hHIP14 and hHIP14L or mHip14L cDNA constructs, linearized and then transcribed with T7 polymerase in the presence of m7GpppG cap using the mMESSAGE MACHINE™ T7 Kit (Ambion) transcription system. Preparation of oocytes, injection with cRNA, and two-electrode voltage-clamp were as previously described (13). Oocytes were studied 3–5 days following injection. Permeability ratios were calculated using the Nernst relation and apparent Km and Vmax values with Eadie-Hofstee analysis using non-linear regression analysis (12).

Epifluorescence microscopy was used to measure Mg2+ flux into single oocytes using the Mg2+-responsive mag-fura-2 fluorescence dye (13). Oocytes were injected with 50 μm mag-fura-2 acid (Molecular Probes), 20 min prior to experimentation. The chamber (0.5 ml) was mounted on an inverted Nikon Diaphot-TMD microscope, with a Fluor ×10 objective, and a current (I)-voltage (V) plot determined. Subsequently, they were clamped at -70 mV for fluorescence measurements for the indicated times. Fluorescence was continuously recorded using a dual-excitation wavelength spectrofluorometer (Deltascan, Photon Technologies) with excitation for mag-fura-2 at 340 and 385 nm (chopper speed set at 100 Hz), and emission at 505 nm. Results are presented as the 340/385 ratio that reflects the intracellular Mg2+ concentration.

Cell Culture—MDCK and COS-7 epithelial cells were cultured in minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 110 mg/liter sodium pyruvate, 5 mm l-glutamine, 50 units/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin in a humidified environment of 5% CO2, 95% air at 37 °C. Where indicated, subconfluent cells were cultured in nominally Mg2+-free or normal 0.8 mm magnesium media (Stem Cell Technologies) for 12–16 h prior to harvest or processing for immunochemistry as previously described (13). Other constituents of the Mg2+-free culture media were similar to the complete media.

Immunofluorescence Confocal Microscopy—Subcellular localization of HIP14 and HIP14L were performed by immunofluorescence with transfection of tagged constructs. MDCK and COS-7 epithelial cells were transiently transfected with either pCI-HIP14-GFP or pCI-HIP14L-GFP using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Transfections were performed 8–9 h prior to culture in normal or low magnesium. Coverslips of cultured cells were fixed at room temperature for 10 min in 2% paraformaldehyde. Cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.3% Triton X-100 (PBST) before each antibody incubation. The following primary antibodies were used: GM130 (a cis-Golgi matrix protein) and Rab5 (GTP-binding protein) that were raised in mouse (BD Transduction Labs). Alexa 488- and Alexa 568-conjugated secondary antibodies were obtained from Molecular Probes. All antibody reactions were performed in blocking solution composed of 2% normal goat serum in PBST for 1.5 h at room temperature. Alexa 350-conjugated phalloidin (Molecular Probes) was used to stain for actin in the indicated experiments to aid in delimiting peripheral membrane ruffles. Following staining, coverslips were then mounted on slides with Fluoromount-G glycerol-based mounting media (Southern Biotechnology).

Oocytes were mounted in OCT cryostat medium and flash frozen in isopentane cooled in liquid nitrogen. Ten-μm thick sections were cut through frozen oocytes and mounted directly onto superfrost plus slides (Fisher Scientific). Sections were fixed in -20 °C methanol and processed for immunohistochemistry using the GFP primary antibody and anti-rabbit Alexa 568 secondary antibody.

All epithelial cell images were taken using a ×63 water lens affixed to a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta microscope and AxioVision (epifluorescent) or LSM 510 Meta (confocal) software. Cells were selected from 10–12 fields of view and used for assessment of co-localization of antibody staining. Oocytes images were taken using a ×20 dry objective affixed to a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta microscope and LSM Image software.

RESULTS

HIP14 and HIP14L Are Magnesium-responsive Genes—With the knowledge that differential gene expression is involved with selective control of epithelial cell magnesium conservation, our strategy was to use microarray analysis to identify cDNAs that were up-regulated with low magnesium (12). We used RNA from immortalized mouse distal convoluted tubule epithelial cells cultured in media containing normal magnesium concentration or nominally magnesium-free media for 5 h prior to RNA harvest. As our objective was to identify novel transport proteins, we prioritized the differentially expressed candidates according to the predicted structural properties reported for hypothetical transporters. One of the selected cDNA fragments identified by an increase in transcript was Hip14L. A BLAST search of the GenBank™ data base was performed and another member of this family, HIP14, was identified. As Hip14 was not on the mouse Affymetrix MG U74 Bv2 and MG U74 Cv2 arrays (Affymetrix) used at the time of our initial microarray analysis, we first showed that both Hip14 and Hip14L transcripts are regulated by magnesium using real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR. Hip14 and Hip14L mRNAs significantly (p < 0.001) increased 2.9 ± 0.3- and 3.0 ± 0.2-fold, respectively, in mouse distal convoluted tubule epithelial cells, n = 6 independent preparations, cultured in low magnesium compared with normal cells confirming that they are differentially regulated by magnesium (Fig. 1A). Consonant with the increase in transcript there was an increase in endogenous Hip14 protein as determined with Western blotting using a HIP14-specific antibody (1). It was evident from the Western blots that the Hip14 protein band density increased in MDCK cell cultures in low magnesium relative to normal cells. Mean density of the Hip14 protein increased 2.5 ± 0.5- and 4.5 ± 1.0-fold, respectively, in supernatant and membrane pellets (Fig. 1B). HIP14 increased 1.9 ± 0.3- and 5.4 ± 1.3-fold in COS-7 cells prepared under similar conditions (Fig. 1C).

FIGURE 1.

Increased endogenous Hip14 transcript and Hip14 protein expression with low magnesium. A, quantitative analysis of Hip14 transcript in MDCK cells by real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR. The expression levels of the Hip14 mRNA were normalized with those of the β-actin transcript that was measured on the same DNA. The indicated values are mean ± S.E. obtained from separate cell preparations. B, Western blotting of endogenous Hip14 protein in MDCK cells cultured in normal (Normal Mg2+) and low magnesium (Low Mg2+) media. Hip14 protein was determined in supernatant (S) and pellet (P) fractions. Shown is a representative blot, one of four performed on different cell preparations. C, summary of the mean band density increases with low magnesium relative to those cultured with normal concentrations of magnesium. The mean density increased 2.5- and 4.5-fold, respectively, in supernatant and membrane pellets with low magnesium. D, predicted secondary structure of mouse Hip14. HIP14 resembles a typical membrane transporter and possesses a palmitoyl acyltransferase motif (DHHC).

Hydrophobicity plot using the SOUSI program predicted a secondary amino acid structure for HIP14 with six predicted transmembrane domains (TMDs) (Fig. 1D). The structure was initially predicted to be a membrane receptor or transporter (1). The DHHC-cysteine-rich domain consensus sequence is located within the cytoplasmic region between TMD4 and TMD5. Human HIP14L has a 69% similarity to HIP14 and possesses seven predicted TMDs. The cysteine-rich domain is located between TMD5 and TMD6 (Fig. 3A). We speculate that the first transmembrane region is cleaved on formation of the mature protein so that the DQHC motif would be located in the same position as HIP14.

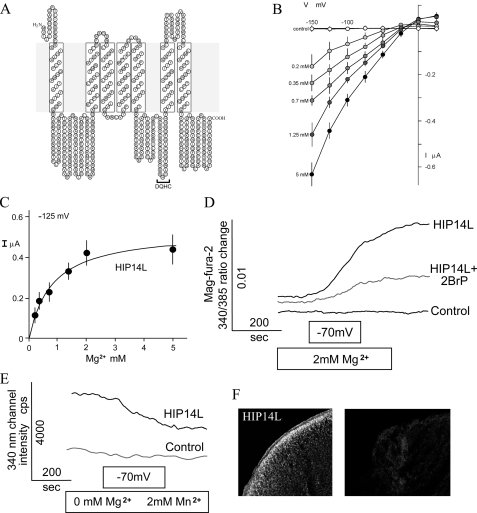

FIGURE 3.

Characterization of HIP14L. A, predicted secondary structure of mouse HIP14L. HIP14L possesses a palmitoyl acyltransferase motif (DQHC). B, current-voltage (I–V) relationships obtained from linear voltage steps in the presence of Mg2+-free solutions or those containing the indicated concentrations of MgCl2. Oocytes were clamped as described in the legend to Fig. 1B. Shown are average I–V curves obtained from control H2O-injected (n = 3) or HIP14L-expressing (n > 3) oocytes. C, summary of concentration-dependent Mg2+-evoked currents in HIP14L-expressing oocytes using a holding potential of -125 mV. Mean ± S.E. values are those given in Fig. 2B. The Michaelis constant determined with non-linear regression analysis was 0.87 mm. D, Mg2+ flux into HIP14L-expressing oocytes. Mag-fura-2 fluorescence ratios were measured in control and HIP14L-expressing oocytes, at resting potentials, in solutions consisting of nominally magnesium-free solutions and then with 2.0 mm MgCl2 with interruption and subsequently voltage-clamped at a holding potential of -70 mV, where indicated. Where indicated, 75 μm 2-bromopalmitate (2BrP) was added 3 h prior to experimentation. E, HIP14L mediates Mn2+ transport in expressing oocytes. Oocytes were initially voltage-clamped at -70 mV in the presence of Mn2+, a cation that quenches mag-fura-2 fluorescence at 340 nm. Note, the intensity determined at 340 nm diminished in HIP14L expressing cells but not water-injected control oocytes. Results are mean of tracings performed with 3 different oocyte preparations. F, surface expression of HIP14L-GFP protein in X. laevis oocytes determined with immunofluorescence. Left panel, HIP14L-GFP-injected oocyte treated with GFP antibody showing intense surface staining. Right panel, control water-injected oocytes tested with GFP antibody.

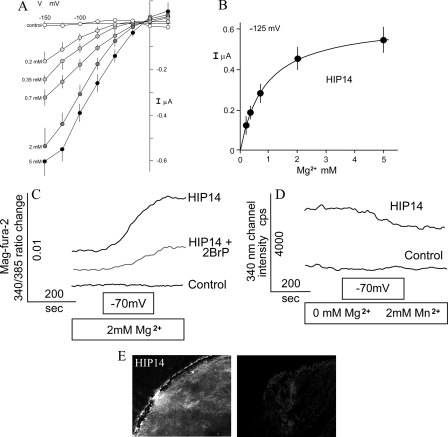

HIP14 and HIP14L Mediate Mg2+ Transport in Expressing Xenopus Oocytes—To determine whether HIP14 and HIP14L encode functional Mg2+ transporters, we prepared the respective human and mouse cRNAs, injected it into Xenopus oocytes, and measured Mg2+-evoked currents using two-microelectrode voltage clamp analysis and Mg2+ flux using mag-fura-2 fluorescence methodologies (13). The electrophysiological data gave evidence for a rheogenic process with inward currents in HIP14 cRNA-injected oocytes, whereas there were no appreciable currents in control H2O- or total poly(A)+ RNA-injected cells from the same batch of oocytes. Fig. 2A shows mean current-voltage (I–V) plots. There was a mean +28 mV shift in reversal potential with a decade increase in magnesium concentration that approximated the theoretical value predicted by the Nernst relationship. Similar findings were obtained with HIP14L-expressing oocytes (Fig. 3B). Expression of GODZ, a Golgi-specific DHHC zinc finger protein (14), did not elicit or stimulate Mg2+ transport in control oocytes arguing against the notion that palmitoylation stimulated an endogenous Mg2+ transporter (see data presented below). GODZ protein acyltransferase is implicated in palmitoylation and regulated trafficking of diverse intracellular receptors and transporters (15, 16). Among the inherent properties of all transporters is the property of substrate saturation. The Mg2+-evoked currents elicited by HIP14 and HIP14L were saturable (Figs. 2B and 3C) demonstrating Michaelis constants (Km) of 0.87 ± 0.02 and 0.74 ± 0.07 mm, respectively. The substrate affinities of both transporters were commensurate with the physiological concentration of intracellular ionized Mg2+ of about 0.5 mm (10). Mag-fura-2 fluorescence determinations confirmed that the observed currents were due to Mg2+ influx (Fig. 2C). External magnesium increased the emission ratio of 340/385 excitation following voltage-clamp at -70 mV in HIP14 cRNA-injected oocytes but not control water-injected cells. Similar findings were observed using HIP14L-expressing oocytes (Fig. 3D). The electrophysiological experiments demonstrated that Mn2+ elicited currents in HIP14- and HIP14L-expressing oocytes (supplemental Fig. S1A). This was also evident using fluorescence measurement (Figs. 2D and 3E). Mn2+-quenched mag-fura-2 fluorescence in expressing oocytes, as expected if HIP14 and HIP14L mediated Mn2+ transport. These studies clearly indicate that HIP14 and HIP14L mediate Mg2+ transport in expressing oocytes. Immunofluorescence using a HIP14-GFP and HIP14L-GFP constructs and anti-GFP antibody shows predominantly surface localization of HIP14 and HIP14L fusion proteins in expressing oocytes, whereas there was no staining in control, water-injected oocytes (Figs. 2E and 3F).

FIGURE 2.

Functional characterization of HIP14. A, current-voltage (I–V) relationships obtained from linear voltage steps in the presence of Mg2+-free solutions or those containing the indicated concentrations of MgCl2. Oocytes were clamped at a holding potential of -15 mV and then stepped from -150 to +25 mV in 25-mV increments for 2 s at each of the concentrations indicated. Shown are average I–V curves obtained from control H2O-injected (n = 3) or Hip14-expressing (n = ≥3) oocytes. Note the positive shift in reversal potential from increments in Mg2+ concentration. Values are mean ± S.E. of observations measured at the end of each voltage sweep for the respective Mg2+ concentration. B, summary of concentration-dependent Mg2+-evoked currents in HIP14-expressing oocytes using a holding potential of -125 mV. Mean ± S.E. values are those given in B. The mean Michaelis constant was 0.87 mm. C, Mg2+ flux into HIP14-expressing oocytes. Mag-fura-2 fluorescence ratios were measured in control and HIP14-expressing oocytes, at resting potentials, in solutions consisting of nominally magnesium-free solutions and then with 2.0 mm MgCl2 and subsequently voltage-clamped at a holding potential of -70 mV, where indicated. Mg2+ fluxes were determined with fluorescence using the Mg2+-sensitive dye, mag-fura-2. Where indicated 75 μm 2-bromopalmitate (2BrP) was added 3 h prior to experimentation. D, HIP14 mediates Mn2+ transport in expressing oocytes. Oocytes were initially voltage-clamped at -70 mV in the presence of Mn2+, a cation that quenches mag-fura-2 fluorescence at both 340 and 385 nm. Results are mean of tracings performed with 3 different oocyte preparations. E, surface expression of HIP14-GFP protein in X. laevis oocytes determined with immunofluorescence. Left panel, HIP14-GFP-injected oocyte treated with GFP antibody showing intense surface staining. The measured current for this oocyte was 0.18 μA with 2.0 mm external MgCl2 concentration clamped at -70 mV. Right panel, control water-injected oocytes tested with GFP antibody.

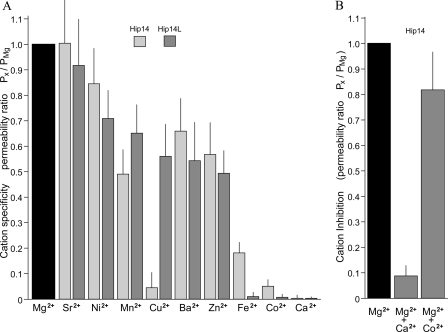

The second property of most transporters is substrate selectivity. Accordingly, a variety of extracellular divalent cations were used to determine the selectivity of the expressed HIP14 and HIP14L channels. HIP14 was relatively selective for Mg2+ at concentrations normally seen in the cytoplasm (Fig. 4A). As indicated by the reversal potential ratios, HIP14 transported Sr2+ and Ni2+ and to a lesser extent Mn2+, Ba2+, Zn2+, and Fe2+ (Fig. 4A). Co2+ and Ca2+ were not transported by HIP14. The only differences in cation selectivity between HIP14 and HIP14L was with Cu2+ and Fe2+; HIP14 did not mediate Cu2+ transport but transported Fe2+, whereas HIP14L was permeable to Cu2+ not Fe2+ (Fig. 4A). In the experiments shown, currents were corrected for changes in membrane resistance caused by the respective divalent cation using values from H2O-injected oocytes (Fig. 4A). On balance, HIP14- and HIP14L-mediated cation transport was relatively selective for Mg2+ in the physiological concentrations normally observed within the cell, the other divalent cations are not normally present at 0.2 mm concentrations.

FIGURE 4.

Cation selectivity and inhibition of HIP14- and HIP14L-mediated Mg2+ currents expressed in Xenopus oocytes. A, summary of substrate specificity of HIP14 and HIP14L following application of Ca2+, 2.0 mm, and other test cations, 0.2 mm, in the absence of external Mg2+. Oocytes were clamped at a holding potential of -15 mV and then stepped from -150 to +25 mV in 25-mV increments for 2 s for each of the cations. Values are mean ± S.E. for the permeability ratios measured at the end of each voltage sweep for the respective divalent cation. B, inhibition of Mg2+-evoked currents in HIP14-expressing oocytes with 5.0 mm Ca2+ or 0.2 mm Co2+ in the presence of external 2.0 mm Mg2+. Results are mean ± S.E. based on the changes in the Erev for the respective study. The inhibitor, either CaCl2 or CoCl2 was added with MgCl2 and the voltage clamp was performed about 5 min later.

Finally, a general property of transporters is the ability to be inhibited by related but not transported substrates. We tested if the non-transported cations, Co2+ and Ca2+, would inhibit HIP14-mediated Mg2+ currents. Relatively large concentrations of 0.2 mm Co2+ and 5.0 mm Ca2+ were tested in the presence of 2.0 mm MgCl2 (Fig. 4B). Ca2+ completely inhibited Mg2+ currents, whereas Co2+ did not inhibit transport as reflected by the change in reversal potential for Mg2+. On balance, these data indicate that HIP14-mediated transport demonstrates saturation, selectivity, and the ability to be differentially inhibited by other divalent cations.

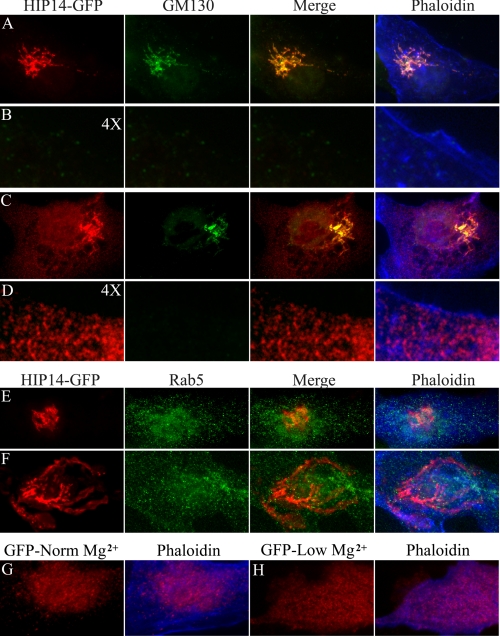

Changes in Extracellular Magnesium Lead to Subcellular Redistribution of HIP14-GFP and HIP14L-GFP Proteins—Normally HIP14 protein is localized to the Golgi and post-Golgi vesicles involved with protein sorting and recycling to the Golgi (9). Our studies confirm these earlier observations. The HIP14-GFP fusion protein colocalizes with the Golgi marker, GM130, in MDCK (Fig. 5A) and COS-7 (supplemental Fig. S1A) cells cultured in normal magnesium. There was little HIP14-GFP protein in the post-Golgi vesicles of normal MDCK cells (Fig. 5B)). However, it was evident in subplasma membrane vesicles of the COS-7 cells (supplemental Fig. S1). Cells cultured in low magnesium media demonstrated an apparent increase in HIP14-GFP in the Golgi complex commensurate with the increase in HIP14 transcript in Mg2+-restricted MDCK (Fig. 5C) and COS-7 (supplemental Fig. S1) cells. Moreover, there was also a significant increase in HIP14-GFP protein present in post-Golgi vesicles that was evident even with MDCK cells. The protein appears to be located just below the plasma membrane as outlined at higher magnification with phalloidin (Fig. 5D). It should be noted that these were transfected cells so the apparent increase in HIP14-GFP protein with low magnesium represents post-transcriptional changes. Post-transcriptional and post-translational modifications would be expected to result in prolongation of message, increased protein synthesis, and retention of mature protein. The post-Golgi vesicles did not colocalize with Rab5, a marker of early or recycling endosomes, in cells maintained in either normal or low magnesium media (Fig. 5, E and F). This supports the notion that HIP14 does not traffic to the plasma membrane. Note the appreciable increase in subplasma membrane HIP14-GFP protein in magnesium-restricted cells in this figure (Fig. 5F). There was no change in GFP protein in cells transfected with GFP alone (Fig. 5, G and H). In summary, these observations confirm that HIP14 protein normally resides in the Golgi and post-Golgi subplasma membrane vesicles and with low magnesium there occurs an increase in both Golgi and submembrane vesicle HIP14 protein.

FIGURE 5.

Subcellular redistribution of HIP14-GFP fusion protein in response to magnesium. Immunofluorescence staining of HIP14-GFP fusion protein of transiently expressing MDCK epithelial cells. A, Golgi localization of HIP14-GFP. Cells were cultured in media containing the normal magnesium concentration, fixed, and incubated with GFP antibody (HIP14-GFP) and the Golgi marker, GM130 (GM130). The merged image demonstrates HIP14-GFP and GM130 colocalization (Merge). A phaloidin overlay of the merged image shows the surface membrane (Phaloidin). B, there was very little submembrane HIP14 protein in MDCK cells cultured in normal magnesium media. The image is of A digitally enlarged 4 times with each of the respective stains. C, Golgi localization of HIP14-GFP in cells cultured in low magnesium media. Cells were fixed and incubated with GFP antibody (HIP14-GFP), GM130, (GM130), GFP and GM130 merged (Merge), and phaloidin (Phaloidin). Note, the increase in Golgi HIP14-GFP and the evident appearance of subplasma membrane HIP14-GFP protein. D, submembrane location of post-Golgi HIP14-GFP protein with low magnesium. The image is of C digitally enlarged 4 times with each of the respective stains. Note, the predominant submembrane localization of post-Golgi HIP14-GFP protein. E, absence of HIP14-GFP protein in early recycling endosomes supporting the notion that HIP14 protein does not traffic to the plasma membrane. MDCK cells were cultured in normal media with normal magnesium concentration. The images comprise HIP14-GFP staining (HIP14-GFP), Rab5 (Rab5), HIP14-GFP and Rab5 merged image (Merge), and the phaloidin overlay image (Phaloidin). F, absence of HIP14-GFP protein in early recycling endosomes. MDCK cells were cultured in media with low magnesium. HIP14-GFP staining (HIP14-GFP), Rab5 (Rab5), merged image (Merge), and the phaloidin overlay image (Phaloidin) are shown. G, control MDCK cells transfected with GFP alone. H, magnesium-restricted MDCK cells transfected with GFP alone. Changes in magnesium concentration do not alter GFP distribution. All images are representative in excess of 30 cells for each condition.

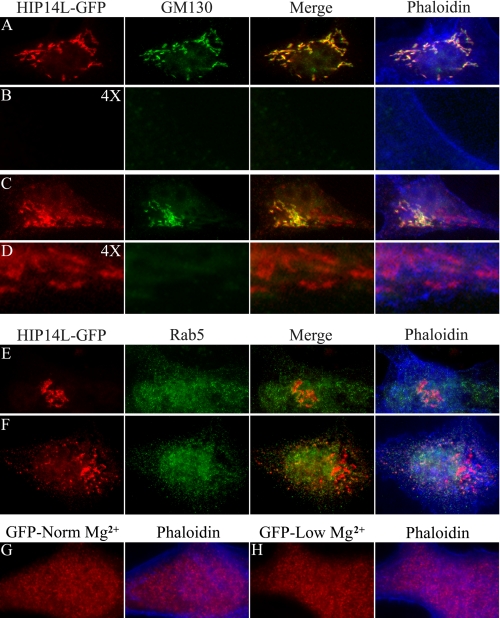

Similar results were observed with localization and redistribution of the HIP14L-GFP fusion protein expressed in MDCK cells (Fig. 6). HIP14L-GFP is predominately found in the Golgi complex. Magnesium restriction leads to an apparent increase in Golgi HIP14L-GFP protein and an increase or recruitment of protein to the subplasma membrane vesicles. These regions did not conform to early endosomes as would be expected of proteins that are cycling on and off the plasma membrane.

FIGURE 6.

Subcellular redistribution of HIP14L-GFP fusion protein in response to magnesium. Immunofluorescence staining of HIP14L-GFP fusion protein of transiently expressing MDCK epithelial cells. A, Golgi localization of HIP14L-GFP. Cells were cultured in media containing normal magnesium concentration, fixed, and incubated with GFP antibody (HIP14L-GFP) and the Golgi marker, GM130 (GM130). The merged image demonstrates HIP14L-GFP and GM130 colocalization (Merge). A phaloidin overlay of the merged image shows the surface membrane (Phaloidin). B, there was very little submembrane HIP14L protein in MDCK cells cultured in normal magnesium media. The image is of A digitally enlarged 4 times with each of the respective stains. C, Golgi localization of HIP14L-GFP in cells cultured in low magnesium media. Cells were fixed and incubated with GFP antibody (HIP14L-GFP), GM130 (GM130), GFP and GM130 merged (Merge), and phaloidin (Phaloidin). Note, the increase in Golgi HIP14L-GFP and the evident appearance of subplasma membrane HIP14L-GFP protein. D, submembrane location of post-Golgi HIP14L-GFP protein with low magnesium. The image is of C digitally enlarged 4 times with each of the respective stains. Note, the predominant submembrane localization of post-Golgi HIP14L-GFP protein. E, absence of HIP14L-GFP protein in early recycling endosomes supporting the notion that the HIP14L protein does not traffic to the plasma membrane. MDCK cells were cultured in normal media with normal magnesium concentration. The images comprise HIP14L-GFP staining (HIP14L-GFP), Rab5 (Rab5), HIP14L-GFP and Rab5 merged image (Merge), and the phaloidin overlay image (Phaloidin). F, absence of HIP14L-GFP protein in early recycling endosomes. MDCK cells were cultured in media with low magnesium. HIP14L-GFP staining (HIP14L-GFP), Rab5 (indicated as Rab5), merged image (Merge), and the phaloidin overlay image (Phaloidin) are shown. G, control MDCK cells transfected with GFP alone. H, magnesium-restricted MDCK cells transfected with GFP alone. Changes in magnesium concentration do not alter GFP distribution. All images are representative in excess of 30 cells for each condition.

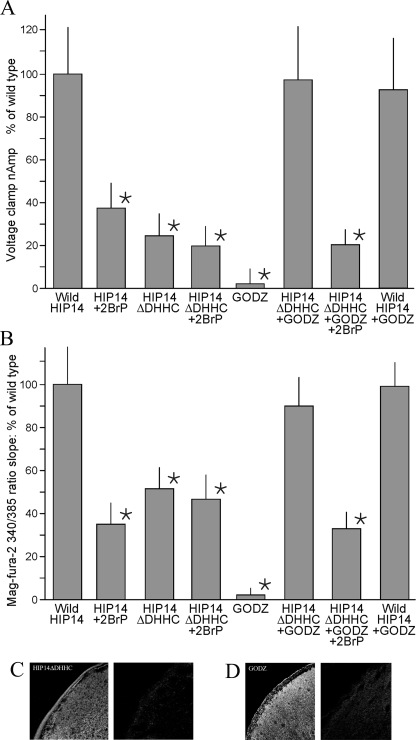

Palmitoyl Acyltransferase Modulates HIP14-mediated Mg2+ Transport—It was of interest that HIP14 demonstrates protein acyltransferase activity, and metabolic labeling studies showed that HIP14 itself is palmitoylated through its innate DHHC domain (8). HIP14 and HIP14L contain 11 cysteine residues in the predicted cytoplasmic loop region that are highly conserved and might function as palmitoylation sites. Accordingly, palmitoylation might influence HIP14-mediated Mg2+ transport. To determine whether protein acyltransferase is necessary for transport function, we performed two types of experiments. First, we used the specific inhibitor, 2-bromopalmitate, to block palmitoylation and determined its effects on HIP14-mediated Mg2+ transport (2). Treatment of HIP14-expressing oocytes with 75 μm 2-bromopalmitate for 3 h diminished Mg2+ transport by about 60% as measured with two independent methodologies, voltage-clamp experiments (Fig. 7A) and fluorescence studies (Fig. 7B). The inhibitor, 2-bromopalmitate, did not have any effect on control H2O-injected oocytes nor did it have any influence on the function of other expressed Mg2+ transporters such as MagT1 (12) and NIPA1 (13) (data not shown). Maximal concentrations of 2-bromopalmitate also inhibited HIP14L-mediated Mg2+ transport by about 50% (Fig. 3D). Second, we created a truncated form of HIP14 that is lacking the DHHC domain (HIP14ΔDHHC) and fails to catalyze palmitoylation of its metabolic substrates (2). Mg2+ transport was decreased in the order of 50% in mutant HIP14ΔDHHC-expressing cells relative to wild-type HIP14-expressing oocytes, again using both voltage-clamp experiments (Fig. 7A) and fluorescence studies (Fig. 7B). The HIP14ΔDHHC-tagged construct localized to the surface membrane of the oocyte (Fig. 7C). The residual Mg2+ transport observed with DHHC deletion was similar to that observed with maximal inhibition with 2-bromopalmitate. Furthermore, the residual Mg2+ transport observed with HIP14ΔDHHC was not significantly inhibited by 2-bromopalmitate indicating that both approaches, inhibition and deletion, have the same effect (Fig. 7, A and B). Taken together these data suggest that palmitoylation activates HIP14-mediated Mg2+ transport. In support of this conclusion, coexpression of GODZ, an independent acyltransferase, with the mutated HIP14ΔDHHC stimulated Mg2+ uptake to levels not unlike those observed for the wild-type HIP14 alone (Fig. 7, A and B). GODZ was present on the surface of GODZ-expressing oocytes (Fig. 7C). GODZ alone did not stimulate Mg2+ transport in oocytes indicating that palmitoylation did not have a general effect but required the HIP14 protein (Fig. 7, A and B). It further supports that native oocytes do not possess endogenous protein acyltransferase that is able to palmitate HIP14 protein. Additionally, 2-bromopalmitate inhibited the stimulation of transport by GODZ in HIP14ΔDHHC-expressing oocytes, again to transport rates similar to that observed with wild-type HIP14 plus 2-bromopalmitate (Fig. 7, A and B). These studies strongly argue for a role of the HIP14 palmitoyl acyltransferase in modulating HIP14-mediated Mg2+ transport function through a process of autoacylation. Finally, coexpression of wild-type HIP14 with GODZ in the oocytes did not stimulate Mg2+ transport above rates observed for HIP14 alone (Fig. 7, A and B). This suggests that heterologous expressed HIP14 and HIP14L were normally fully activated (autoacylated) so that regulation of transport function involves deacylation.

FIGURE 7.

Protein acyltransferase modulates HIP14-mediated Mg2+ transport. Where indicated, oocytes were injected with wild-type HIP14 cRNA (HIP14), HIP14 with DHHC deletion cRNA (HIP14ΔDHHC), or/and GODZ cRNA (GODZ). Where indicated, expressing oocytes were treated with and without 75 μm 2-bromopalmitate for 3 h prior to experimentation. A, summary of Mg2+-evoked currents determined with voltage-clamp experiments. Currents were measured with 2.0 mm MgCl2 at a holding potential of 125 mV according to the parameters given in Fig. 1B. Results are normalized to wild-type HIP14 and represented as mean ± S.E. for n = 50, 9, 19, 3, 21, 5, 4, and 5 oocytes, respectively. *, indicates significance, p < 0.05, compared with wild-type HIP14. B, Mg2+ flux, determined by the slope of the mag-fura-2 fluorescence 340/385 ratio change at -70 mV voltage clamp. Results were normalized to wild-type HIP14 observations. Intracellular Mg2+ concentration changes were measured with 2.0 mm external MgCl2 according to the methods given in the legend to Fig. 1D. Results are means of 8 oocytes. * indicates significance, p < 0.05, compared with wild-type HIP14. C, surface expression of HIP14DDHHC-GFP (HIP14ΔDHHC) protein in X. laevis oocytes determined with immunofluorescence. D, surface expression of GODZ-FLAG (GODZ) protein in oocytes.

DISCUSSION

The evidence given here indicates that HIP14 and HIP14L mediate Mg2+ transport and the data of Huang and Ducker and their respective colleagues (2, 6) indicates that these proteins mediate acylpalmitoylation of a number of proteins including themselves through a process of autopalmitoylation. The evidence that HIP14 and HIP14L are magnesium transporters is persuasive. First, expression of HIP14 and HIP14L in Xenopus oocytes produces Mg2+-evoked currents with channel-like properties as measured with voltage-clamp conditions. The reversal potential shifts to the right with a magnitude of 28 mV as predicted by the Nernst relationship with decade increases in magnesium concentration. Mg2+ currents are concentration-dependent, saturable, reversible, and inhibitable as would be expected of a channel-like transporter. Second, HIP14 and HIP14L mediate Mg2+ flux as determined by fluorescence with the Mg2+-sensitive mag-fura-2 dye. Accordingly, the currents measured with two-electrode voltage-clamp are formed by the movement of Mg2+ ions. Third, Hip14 and Hip14L transcripts and Hip14 protein are quantitatively altered with changes in Mg2+ concentration, consonant with our initial paradigm that Mg2+ transport is regulated by transcriptional processes responsive to Mg2+ concentration (12). Fourth, we demonstrate that post-translational Golgi HIP14 and HIP14L protein trafficking to the subplasma membrane region is increased with diminished extracellular Mg2+ as would be expected of a magnesium-regulated transporter. It has been convincingly demonstrated, using an in vivo [3H]palmitoyl-CoA incorporation assay, that HIP14 palmitoylates a number of substrates such as SNAP-25, PSD-95, GAD65, synaptotagmin 1, and huntingtin (2). In confirmation, Varner et al. (17) applied high-performance liquid chromatography to measure in vivo palmitoylation using peptides that mimic distinct palmitoylation motifs. They showed that HIP14 is a palmitoyl acyltransferase with a preference for the farnesyl-dependent palmitoylation motif found in H- and N-RAS (6). More recently, Yanai et al. (9) reported that HIP14 palmitoylates huntingtin, which is essential for huntingtin trafficking and function. Moreover, HIP14, itself is palmitoylated by hetero- and homo-palmitoylation (8). Thus it is clear that the DHHC sequence of HIP14 has enzymatic functions in addition to mediating Mg2+ transport. Accordingly, HIP14 and HIP14L are “chanzymes,” proteins that demonstrate fused channel and enzyme activities (18).

Until the present studies, chanzymes were represented only in the transient receptor potential melastatin (TRPM) family of transporters. TRPM2 principally mediates Ca2+ transport and TRPM6 and TRPM7 transport Ca2+ and Mg2+ and other divalent cations (19, 20). The TRPM2 channel has C-terminal ADP-ribose pyrophosphatase and TRPM6 and TRPM7 have an atypical protein a-kinase fused to the TRPM channel regions (21–25). With the observation that HIP14 and HIP14L mediate Mg2+ transport and demonstrate protein acyltransferase activity, the present study extends this list of known chanzymes. Proteins with dual functions may be more common than otherwise appreciated.

Palmitoylation (or thioacylation) of cysteine residues has emerged recently as a reversible post-translational modification involved in regulated trafficking and functional modulation of membrane proteins. Palmitoylation is a relatively common phenomenon within the cell and plays a prominent role for subcellular localization and regulation of acyltransferases and thioesterases and their cognate substrates that cycle on and off membranes (7, 26). As reviewed by Linder and Dechenes (7), palmitate exerts its effects primarily through interactions with lipid bilayers. In this context, HIP14 palmitoylates huntingtin and protects it from forming aggregates thus performing an essential function in protein trafficking (2).

The DHHC domain of HIP14 palmitoylates a number of substrates including HIP14 itself through a process of autoacylation (8). Our findings show that inhibition of palmitoyl acyltransferase or deletion of the DHHC motif diminishes HIP14-mediated Mg2+ transport. The mechanism is unclear but palmitoylation may directly facilitate transport activity or palmitoylation may be required for appropriate HIP14 protein insertion into the plasma membrane. Many cation transporters such as Na+, K+, and Ca2+ channels are known to be activated by palmitoylation (26–32). Alternatively, palmitoylation has been implicated in sorting and trafficking of other transport and receptor proteins (9, 33–35). Although we did not directly measure palmitoylation of HIP14 in these studies, we used two approaches to implicate protein palmitoylation; inhibition with the specific analogue, 2-bromopalmitate, and deletion of the zinc finger DHHC cysteine-rich motif (2, 9, 15). Our studies show that DHHC activity and palmitoylation are required for maximal Mg2+ transport mediated by HIP14 and our evidence supports the notion that palmitoylation directly enhances Mg2+ transport. This conclusion is supported by the observation that 2-bromopalmitate, an inhibitor of palmitoyl transferase, diminishes Mg2+ transport by about 50% in the presence of normal amounts of wild-type HIP14 protein. Second, HIP14 DHHC deletion decreases transport without changes in surface HIP14 protein. Of note is the observation that palmitoylation is not necessary for basal transport. 2-Bromopalmitate and DHHC deletion decrease Mg2+ transport by similar amounts; the two together were not additive, leaving residual Mg2+ transport that presumably is the basal transport in the absence of palmitoylation. Second, GODZ does not stimulate wild-type HIP14-mediated transport suggesting that the heterologously expressed HIP14 is normally fully acylated by its innate palmitoyl acyltransferase in oocytes. Accordingly, regulation of HIP14-mediated transport occurs at the depalmitoylation step rather than the palmitoylation step. This is in keeping with the notion that acylation of cysteinyl-containing proteins is spontaneous and driven by local acyl-CoA concentrations (7). Palmitate cycling is regulated at the depalmitoylation step by acylprotein thioesterases. Further studies are required to determine whether this model is also applicable to mammalian cells.

The potential implications of HIP14-mediated cation transport are numerous. HIP14 was first identified by its association with huntingtin protein in a yeast two-hybrid assay (1). Huntingtin is a large protein that has widespread tissue distribution where it is found in many subcellular organelles including nuclear and perinuclear regions, Golgi complex, mitochondria, microtubules, endosomes, clathrin-coated and non-coated vesicles, and plasma membrane (3, 5, 35–40). Huntingtin has been implicated in numerous cellular processes such as transcriptional regulation, mitochondria energetics, structural scaffolding, vesicle trafficking, endocytosis, and dentrite formation (38, 40–43). A mutation in the huntingtin gene results in an expanded polyglutamine tract in the encoded protein underlying the neuropathology of Huntington disease. Huntington disease is a dominant, progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by cognitive deficits, choreic involuntary movements, and mood disturbances. The underlying mechanism by which expanded mutant huntingtin triggers these effects is unknown. Relevant to the present findings is the observation that huntingtin has been implicated in cellular iron acquisition and utilization (36, 44–47). Huntington patients often demonstrate abnormalities of iron homeostasis including decreased serum ferritin, increased brain ferritin, increased transferritin receptor, and decreased iron-requiring enzymes (46–48). Given the pleiotropic nature of huntingtin functions it is unlikely that altered cation transport is the sole cause of the Huntington disorder but a clearer picture of HIP14 and HIP14L physiology should increase our understanding of the disease progression.

In summary, we have shown that HIP14 and HIP14L expressed in oocytes mediate Mg2+ transport, which is regulated by its own palmitoyl acyltransferase. Accordingly, HIP14 and HIP14L are characteristic of chanzymes, proteins combining transport and enzymatic functions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank Dr. Alaa El-Husseini and Dr. Michael Hayden for the HIP14-GFP, HIP14R-GFP, HIP14ΔDHHC, and GODZ-GFP constructs. We acknowledge the BioImaging Facility at the University of British Columbia for the oocyte images.

This work was supported in part by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Grant MOP-53288 (to G. A. Q.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. S1.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: GFP, green fluorescent protein; MDCK, Madin-Darby canine kidney; TRPM, transient receptor potential melastatin; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; TMD, transmembrane domain; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

References

- 1.Singaraja, R. R., Hadano, S., Metzler, M., Givan, S., Wellington, C. L., Warby, S., Yanai, A., Gutekunst, C. A., Leavitt, B. R., Yi, H., Fichter, K., Gan, L., McCutcheon, K., Chopra, V., Michel, J., Hersch, S. M., Ikeda, J. E., and Hayden, M. R. (2002) Hum. Mol. Genet. 11 2815-2828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang, K., Yanai, A., Kang, R., Arstikaitis, P., Singaraja, R. R., Metzler, M., Mullard, A., Haigh, B., Gauthier-Campbell, C., Gutekunst, C. A., Hayden, M. R., and El-Husseini, A. (2004) Neuron 44 977-986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiFiglia, M., Sapp, E., Chase, K., Schwarz, C., Meloni, A., Young, C., Martin, E., Vonsattel, J. P., Carraway, R., Reeves, S. A., Boycea, F. M., and Aronin, N. (1995) Neuron 14 1075-1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Velier, J., Kim, M., Schwarz, C., Kim, T. W., Sapp, E., Chase, K., Aronin, N., and DiFiglia, M. (1998) Exp. Neurol. 152 34-40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kegel, K. B., Sapp, E., Yoder, J., Cuiffo, B., Sobin, L., Kim, Y. J., Qin, Z. H., Hayden, M. R., Aronin, N., Scott, D. L., Isenberg, G., Goldmann, W. H., and DiFiglia, M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 36464-36473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ducker, C. E., Stettler, E. M., French, K. J., Upson, J. J., and Smith C. D. (2004) Oncogene 23 9230-9237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linder, M. E., and Deschenes, R. J. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8 74-84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Husseini, A. E., Craven, S. E., Chetkovich, D. M., Firestein, B. L., Schnell, E., Aoki, C., and Bredt, D. S. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 148 159-172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yanai, A., Huang, K., Kang, R., Singaraja, R. R., Arstikaitis, P., Gan, L., Orban, P. C., Mullard, A., Cowan, C. M., Raymond, L. A., Drisdel, R. C., Green, W. N., Ravikumar, B., Rubinsztein, D. C., El-Husseini, A., and Hayden, M. R. (2006) Nat. Neurosci. 9 824-831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quamme, G. A. (1997) Kidney Int. 52 1180-1195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dai, L.-j., Ritchie, G., Kerstan, D., Kang, H. S., Cole, D. E. C., and Quamme, G. A. (2001) Physiol. Rev. 81 51-84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goytain, A., and Quamme, G. A. (2005) BMC Genomics 6 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goytain, A., Hines, R., El-Husseini, A., and Quamme, G. A. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 8060-8068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uemura, T., Mori, H., and Mishina, M. (2002) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 296 492-496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fang, C., Deng, L., Keller, C. A., Fukata, M., Fukata, Y., Chen, G., and Luscher, B. (2006) J. Neurosci. 26 12758-12768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greaves, J., and Chamberlain, L. H. (2007) J. Cell Biol. 176 249-254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Varner, A. S., Ducker, C. E., Xia, Z., Zhuang, Y., De Vos M. L., and Smith, C. D. (2003) Biochem. J. 373 91-99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montell, C. (2003) Curr. Biol. 13 799-801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sano, Y., Inamura, K., Miyake, A., Mochizuki, S., Yokoi, H., Matsushime, H., and Furuichi, K. (2001) Science 293 1327-13230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perraud, A. L., Fleig, A., Dunn, C. A., Bagley, L. A., Launay, P., Schmitz, C., Stokes, A. J., Zhu, Q., Bessman, M. J., Penner, R., Kinet, J. P., and Scharenberg, A. M. (2001) Nature 411 595-599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perraud, A. L., Schmitz, C., and Scharenberg, A. M. (2003) Cell Calcium 33 519-531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nadler, M. J., Hermosura, M. C., Inabe, K., Perraud, A. L., Zhu, Q., Stokes, A. J., Kurosaki, T., Kinet, J. P., Penner, R., Scharenberg, A. M., and Fleig, A. (2001) Nature 411 590-595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Runnels, L. W., Yue, L., and Clapham, D. E. (2001) Science 291 1043-1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Demeuse, P., Penner, R., and Fleig, A. (2006) J. Gen. Physiol. 127 421-434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schlingmann, K. P., Waldegger, S., Konrad, M., Chubanov, V., and Gudermann, T. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1772 813-821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Draper, J. M., Xia, Z., and Smith, C. D. (2007) J. Lipid Res. 48 1873-1884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayashi, T., Rumbaugh, G., and Huganir, R. L. (2005) Neuron 47 709-723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmidt, J. W., and Catterall, W. A. (1987) J. Biol. Chem. 262 13713-13723 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qin, N., Platano, D., Olcese, R., Costantin, J. L., Stefani, E., and Birnbaumer, L. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95 4690-4695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chien, A. J., Carr, K. M., Shirokov, R. E., Rios, E., and Hosey, M. M. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271 26465-26468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gubitosi-Klug, R. A., Mancuso, D. J., and Gross, R. W. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102 5964-5968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mies, F., Spriet, C., Heliot, L., and Sariban-Sohraby, S. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 18339-18347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keller, C. A., Yuan, X., Panzanelli, P., Martin, M. L., Alldred, M., Sassoe-Pognetto, M., and Luscher, B. (2004) J. Neurosci. 24 5881-5891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rathenberg, J., Kittler, J. T., and Moss, S. J. (2004) Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 26 251-257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trottier, Y., Devys, D., Imbert, G., Saudou, F., An, I., Lutz, Y., Weber, C., Agid, Y., Hirsch, E. C., and Mandel, J. L. (1995) Nat. Genet. 10 104-110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hilditch-Maguire, P., Trettel, F., Passani, L. A., Auerbach, A., Persichetti, F., and MacDonald, M. E. (2000) Hum. Mol. Genet. 9 2789-2797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strehlow, A. N., Li, J. Z., and Myers, R. M. (2007) Hum. Mol. Genet. 16 391-409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoffner, G., Kahlem, P., and Djian, P. (2002) J. Cell Sci. 115 941-948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oliveira, J. M., Jekabsons, M. B., Chen, S., Lin, A., Rego, A. C., Gonçalves, J., Ellerby, L. M., and Nicholls, D. G. (2007) J. Neurochem. 101 241-249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schilling, G., Klevytska, A., Tebbenkamp, A. T., Juenemann, K., Cooper, J., Gonzales, V., Slunt, H., Poirer, M., Ross, C. A., and Borchelt, D. R. (2007) J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 66 313-320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pal, A., Severin, F., Lommer, B., Shevchenko, A., and Zerial, M. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 172 605-618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caviston, J. P., Ross, J. L., Antony, S. M., Tokito, M., and Holzbaur, E. L. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104 10045-10050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Truant, R., Atwal, R., and Burtnik, A. (2006) Biochem. Cell Biol. 84 912-917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bartzokis, G., and Tishler, T. A. (2000) Cell. Mol. Biol. (Noisy-Le-Grand) 46 821-833 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bonilla, E., Estévez, J., Suárez, H., Morales, L. M., Chacin de Bonilla, L., Villalobos, R., and Dávila, J. O. (1991) Neurosci. Lett. 129 22-24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Metzler, M., Helgason, C. D., Dragatsis, I., Zhang, T., Gan, L., Pineault, N., Zeitlin, S. O., Humphries, R. K., and Hayden, M. R. (2000) Hum. Mol. Genet. 9 387-394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lumsden, A. L., Henshall, T. L., Dayan, S., Lardelli, M. T., and Richards, R. I. (2007) Hum. Mol. Genet. 16 1905-1920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen, J. C., Hardy, P. A., Kucharczyk, W., Clauberg, M., Joshi, J. G., Vourlas, A., Dhar, M., and Henkelman, R. M. (1993) Am. J. Neuroradiol. 14 275-281 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Laemmli, U. K. (1970) Nature 227 680-685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.