Abstract

Δ3(E)-Unsaturated fatty acids are characteristic components of glycosylceramides from some fungi, including also human- and plant-pathogenic species. The function and genetic basis for this unsaturation is unknown. For Fusarium graminearum, which is pathogenic to grasses and cereals, we could show that the level of Δ3-unsaturation of glucosylceramide (GlcCer) was highest at low temperatures and decreased when the fungus was grown above 28 °C. With a bioinformatics approach, we identified a new family of polypeptides carrying the histidine box motifs characteristic for membrane-bound desaturases. One of the corresponding genes was functionally characterized as a sphingolipid-Δ3(E)-desaturase. Deletion of the candidate gene in F. graminearum resulted in loss of the Δ3(E)-double bond in the fatty acyl moiety of GlcCer. Heterologous expression of the corresponding cDNA from F. graminearum in the yeast Pichia pastoris led to the formation of Δ3(E)-unsaturated GlcCer.

Glycosphingolipids represent a structurally and functionally diverse group of membrane lipids ubiquitously distributed among all eukaryotes. They are characteristic constituents of the endomembrane system and highly enriched in the plasma membrane (1-3).

Fungi and some marine invertebrates synthesize glucosylceramides (GlcCers)2 with distinctive structural modifications of the ceramide backbone not found in mammalian and plant glycosphingolipids (4, 5). Fungal GlcCer mainly consists of a diunsaturated, C9-methyl-branched sphingoid base, (4E, 8E)-9-methyl-sphinga-4,8-dienine, which is N-acylated with an α-hydroxylated fatty acid. The fatty acyl moiety can be further modified by the introduction of a Δ3(E)-double bond (Fig. 1), whose function is still unclear.

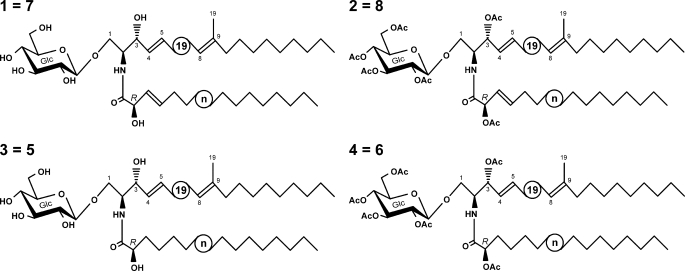

FIGURE 1.

Lipids containing acyl groups with a Δ3(E)-double bond. Top, glycosylceramides from euascomycete fungi show a characteristic consensus structure. The long-chain base is linked to an α-hydroxylated C16 or C18 fatty acid, which is Δ3(E)-unsaturated. The sugar head group can be either glucose (as shown) or galactose. Middle, PG in chloroplasts of higher plants usually carries (3E)-hexadec-3-enoic acid in the sn2-position. Bottom, caleic acid, (3E,9Z,12Z)-octadeca-3,9,12-trienoic acid, can be found, for example, in the plants C. urticaefolia and Stenachaenum macrocephalum, representing a major component of seed triacylglycerols (TAG).

The occurrence of the Δ3(E)-double bond is restricted to euascomycete fungi, including human- and plant-pathogenic species (reviewed in Ref. 5). Depending on the organism, the proportion of Δ3(E)-unsaturated sphingolipids varies. In the two dimorphic fungi Histoplasma capsulatum and Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, the GlcCer of the mycelial form shows a higher proportion of unsaturation than the GlcCer of the yeast form. In galactosylceramides (GalCer) of Aspergillus fumigatus (a fungus without a yeast form), the proportion of Δ3(E)-unsaturated fatty acids is higher than in GlcCer, and in Sporothrix schenckii, the double bond is restricted to GalCer of the yeast form (6-8). These data suggest that the Δ3(E)-desaturation might be important for the yeast-mycelium phase transition of dimorphic fungi, although it depends on the fungus whether the proportion of Δ3(E)-unsaturated fatty acids is higher in the yeast form or in the mycelium.

3(E)-Double bonds are also found in other lipid molecules. Phosphatidylglycerol in photosynthetically active plastids carries mostly Δ3(E)-hexadecenoic acid in the sn-2 position (Fig. 1). The gene locus for the putative desaturase was named fad4, but the actual sequence is still not known (reviewed in Ref. 9). The Δ3(E)-unsaturation can also be found in common polyunsaturated C18-fatty acids of seed triacylglycerols in some higher plants. One example is caleic acid, (3E,9Z,12Z)-octadeca-3,9,12-trienoic acid (Fig. 1), representing a major fatty acid in triacylglycerols from seeds of Stenachaenum macrocephalum and Calea urticaefolia (10-12).

Many enzymes necessary for modifications of the ceramide backbone (glycosyltransferases, desaturases, hydroxylases, C9-methyltransferase) have already been identified and functionally characterized in plants and fungi (13-21). However, a gene corresponding to a desaturase with Δ3(E)-regioselectivity has not yet been cloned.

All sphingolipid modifying desaturases and hydroxylases belong to a large superfamily of membrane-bound enzymes. Therefore, we expected that the Δ3-desaturase would also belong to this group. Members of this superfamily contain three characteristic sequence motifs, the histidine boxes HX3-4H, HX2-3HH, and (H/Q)X2-3HH (22). Some of these sequences are fused to a cytochrome b5 domain. We expected that the fatty acid α-hydroxylase Scs7p from Saccharomyces cerevisiae would show the highest sequence similarity to the Δ3(E)-desaturase because it represents the enzyme with the closest similarity regarding regioselectivity.

Here we describe the identification, cloning, and functional characterization of a sphingolipid-Δ3(E)-desaturase from the plant-pathogenic euascomycete Fusarium graminearum. This monomorphic fungus grows only in the mycelial form and contains GlcCer but no GalCer (23). We used phylogenetic profiling to identify a candidate gene, which was cloned and subjected to deletion and expression studies.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bioinformatics—The NCBI non-redundant protein sequence data base (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) was searched using PSI-BLAST (24) with the α-hydroxylase Scs7p from S. cerevisiae and the fatty acid Δ11-desaturase from Thalassiosira pseudonana (25) as queries. The resulting sequences were checked for the presence of histidine box motifs and analyzed as described in Refs. 20 and 4 using ClustalX (26). With this strategy, 10 desaturase-like sequences were found in the completely sequenced genome of F. graminearum. A putative function could clearly be assigned to 9 of the 10 desaturase sequences by phylogenetic classification within the superfamily of membrane-bound desaturases. The remaining desaturase-like sequence not clustering with desaturases of known regioselectivity was chosen as a query gene for the subsequent BLAST searches of other eukaryotic genomes. Further phylogenetic profiling resulted in promising orthologous candidates forming a single desaturase family restricted to euascomycetes such as F. graminearum (Fg05382, Acc-Nr. XP_383758), Magnaporthe grisea (XP_368852), A. fumigatus (XP_748510), Aspergillus nidulans (XP_662689 and XP_658567), and Neurospora crassa (XP_958382).

Growth of Pichia pastoris—A preculture was grown in YPD medium (2% bacto tryptone, 1% yeast extract, 1% d-glucose) for 24 h at 30 °C with shaking (180 rpm). 200 ml of fresh YPD medium were inoculated 1:100 from the preculture and incubated again for 24 h at 30 °C. Gene expression was induced by replacing YPD with minimal methanol medium (1.3% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 0.5% methanol) and further incubation for 24 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation.

Growth of F. graminearum—For induction of conidiation, mycelium of F. graminearum strain 8/1 (27) was grown on agar plates at 18 °C under near UV light and white light with a 12-h photoperiod for ∼10 days (28). For transformation and/or lipid analysis, F. graminearum was grown in complete minimal medium (CM (29)) for 2-3 days with shaking (150 rpm) and a standard temperature of 28 °C. To determine the temperature-dependent occurrence of the Δ3(E)-double bond in GlcCer, equal amounts of conidia were grown in 100 ml of CM at 18, 28, and 30 °C, respectively, for 3 and 7 days.

Construction of a Disruption Vector for F. graminearum—5′- and 3′-flanking regions of Fg05382 were amplified by a standard PCR program using Pwo-polymerase (peqlab) and the specific primers 5′-agagctcgagCCTAAAGCGACCTACACATATGA-3′ and 5′-atctagatctTGTTAATTTGATGTCGCACATGAGA-3′ (5′-flanking region, 722-bp fragment) and 5′-agagagatctCACGATATCGATTACTTCATGATC-3′ and 5′-agaggcggccgcTCACCATGGCAGTTCAAGCTTAT-3′ (3′-flanking region, 964-bp fragment). All primers provided recognition sites for the restriction enzymes BglII, NotI, or XhoI (underlined). The amplified sequences were cloned into the vector pGEM®-T (Promega). As a selection marker, a hygromycin-resistance cassette (hph, previously cloned into pGEM®-T, with BglII restriction sites at either end) was cloned into the BglII site between the 5′- and 3′-flanking regions, resulting in the construction of pΔ3FgKO. For transformation of F. graminearum, the construct was linearized with XhoI and NotI (all restriction enzymes were obtained from New England Biolabs).

Cloning of the Putative Δ3(E)-Desaturases—cDNA from F. graminearum strain 8/1 was used as template for amplification of the complete open reading frame using a proofreading Pwo-polymerase (peqlab) and a standard PCR program. The specific primer sequences with restriction sites for EcoRI (forward) or NotI (reverse) were: 5′-atctgaattcattATGGCCGAACACCTCGTCT-3′ and 5′-atctgcggccgcCTACTGCCTCTTAAACTTCTT-3′. The resulting PCR product was ligated into the vector pGEM®-T, and its identity was confirmed by sequencing. The isolated fragment was cloned into the EcoRI and NotI restriction sites of the Pichia expression vector pPIC3.5 (Invitrogen), resulting in the plasmid pd3Fg-PIC, which was linearized prior to transformation of P. pastoris with BglII.

Transformation of F. graminearum—Protoplasting and chemical transformation of F. graminearum were carried out as described in Ref. 30 with modifications. 50 ml of CM were inoculated with 30,000 conidia and incubated for 24 h at 28 °C with shaking (150 rpm). Mycelium was homogenized with an Ultra-Turrax blender, and the volume of CM was increased to 200 ml and incubated overnight at 28 °C. The collected mycelium was washed twice with sterile water and dried on sterile Whatman paper. 1 g of mycelium was suspended in 20 ml of an enzyme mix (3% Glucanex™, 5% driselase, both from Sigma-Aldrich, dissolved in 700 mm NaCl, pH 5.6) and digested for 3 h at 28 °C with shaking at 75 rpm. Protoplasts were separated from undigested hyphal material by filtration through gauze and nylon membrane (first filtration, 100-μm pore size; second filtration, 40-μm pore size). The protoplasts were sedimented (5 min, 850 × g), washed twice with ice-cold 700 mm NaCl-solution, and subsequently resuspended in 1 ml of STC (1.2 m sorbitol, 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 50 mm CaCl2) and stored on ice until transformation. For transformation, 1 × 107 protoplasts were diluted in STC to a final volume of 1 ml. 30 μg of the linearized knock-out-cassette were added, and the protoplasts were incubated on ice for 10 min. 1 ml of PTC (60% polyethylene glycol 3350, 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7, 50 mm CaCl2) was added followed by incubation for 20 min on ice. The protoplast suspension was mixed gently with 8 ml of STC and plated in aliquots of 750 μl on regeneration medium (0.1% yeast extract, 0.1% bacto tryptone, 1 m sucrose, 1.6% granulated agar; 10 ml poured in 94-mm Petri dishes). After incubation for 12-24 h at 28 °C, the plates were overlaid with 10 ml of selective agar (1.2% granulated agar in water, 200 μgml-1 hygromycin B) and further incubated. Transformants were obtained about 7 days after transformation. They were transferred to fresh CM plates containing 100 μgml-1 hygromycin B and incubated at 28 °C. Single transformants were isolated and checked for the correct integration of the knock-out cassette by PCR and southern-blotting.

Transformation of P. pastoris—The expression construct pd3Fg-PIC was linearized with BglII. Electrocompetent cells of P. pastoris strain GS115 were generated, and transformation by electroporation was carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Single colonies were checked by PCR for the correct integration of the construct and used for lipid analyses.

Isolation of Glucosylceramide—Approximately 2-3 g of fresh weight of P. pastoris cells or mycelium of F. graminearum were suspended in 5 ml of H2O and boiled in a water bath for 15 min. The cells were sedimented by centrifugation, and the lipids were extracted by shaking in 10 ml of chloroform/methanol 1:1 overnight at 8 °C followed by 9 ml of chloroform/methanol 2:1 for at least 4 h at 8 °C. To increase the yield of F. graminearum lipids, the mycelium was homogenized with an Ultra-Turrax blender during the first extraction step.

The lipid extract was washed by phase partitioning with chloroform/methanol/0.45% NaCl (8:4:3), the organic phase was collected, and the solvents were subsequently evaporated. The lipids in the residue were redissolved in chloroform, and glucosylceramide was purified by preparative TLC on silica gel 60 plates (Merck), developed in chloroform/methanol 85:15. For NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry, the purified GlcCer was peracetylated (with acetic anhydride in pyridine 1:1) overnight at room temperature and repurified by TLC in diethyl ether.

Analysis of Fatty Acids—Fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) were obtained from GlcCer by incubation with sulfuric acid (2 n in methanol with 2% 2,2-dimethoxy propane) overnight at 80 °C and extracted with petrol ether. Because fungal GlcCers mostly contain α-hydroxylated fatty acids, the FAMEs were converted to their trimethylsilyl derivatives. For this purpose, purified FAMEs were dissolved in 100 μl of petrolether. After the addition of 100 μl of N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoro-acetamide (BSTFA, with 1% trimethyl-chlorosilane, Sigma-Aldrich), the samples were incubated at 70 °C for 60 min. Trimethylsilylated fatty acid methyl esters (TMS-FAMEs) were analyzed by GLC and GLC-MS.

Stereochemical Analysis of Hydroxy Fatty Acids—Identification of the (R)- and (S)-stereoisomers of 2-hydroxy-Δ3(E) fatty acids was performed as described previously (31, 32) with the following modifications. FAMEs (50-100 μg), isolated as described above, were first reduced with H2/PtO2 in chloroform/methanol (9:1, v/v) at room temperature (2-5 min).

GLC Analysis—GLC analysis was carried out in a CP3900 (Varian, Palo Alto, CA) with a flame ionization detector using a Select FAME® column (Varian; 50 m, 0.25 mm inner diameter, 0.25-μm film thickness) with a temperature gradient starting from 100 °C (hold for 1 min) to 200 °C at 3 °C/min and continuing with 10 °C/min to 275 °C (8-min hold). Helium was used as carrier gas. Chromatograms were recorded and processed using the Galaxie chromatography data system (Varian).

GLC-MS—GLC-MS analysis was done on an HP 5975 inert XL mass selective detector (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) using an HP-5 MS fused silica column (30 m, 0.25-mm inner diameter, 0.25-μm film thickness) with a temperature gradient starting from 150 °C (3 min) to 320 °C at 5 °C/min. Electron impact mass spectra were carried out at 70 eV.

Electrospray Ionization Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Mass Spectrometry (ESI FT-ICR MS)—ESI FT-ICR MS was performed in the positive ion mode using a high resolution APEX-QE instrument (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA) equipped with a 7-tesla actively shielded magnet and an Apollo ion source. Mass spectra were acquired using standard experimental sequences as provided by the manufacturer. Samples were dissolved at a concentration of ∼10 ng/μl in a 50:50:0.001 (v/v/v) mixture of 2-propanol, water, and 30 mm ammonium acetate adjusted with acetic acid to pH 5 and sprayed at a flow rate of 2 μl/min. Capillary entrance voltage was set to 3.8 kV, and dry gas temperature was set to 175 °C. The obtained mass spectra were charge deconvoluted, and the mass numbers given refer to the monoisotopic masses of the neutral molecules.

NMR Spectroscopy—One-dimensional 1H and two-dimensional homonuclear and H-detected heteronuclear and 1H,13C-correlation spectra were recorded on a 600-MHz spectrometer (Bruker Avance DRX-600) at 300 K. Spectra were taken from 0.1-0.5 mg of glucosylceramide, isolated from F. graminearum wild type and the Δ3(E)-desaturase expression mutant of P. pastoris, in 3-mm tubes (Ultra Precision, Norell, Landisville, NJ). The peracetylated samples were dissolved in 0.25 ml of deuterated chloroform (99.96%, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Andover, MA) using tetramethylsilane (δH = 0.000) and chloroform (δC = 77.0) as internal reference. The native glycolipids were dissolved in 0.25 ml of deuterated methanol (99.96%, Deutero, Kastellaun, Germany) using methanol (δH = 3.34, δC = 48.86) as internal reference. One-dimensional (1H-) and two-dimensional homonuclear (1H,1H-COSY (correlation spectroscopy), TOCSY (total correlation spectroscopy), ROESY (rotational frame Overhauser spectroscopy)) and H-detected heteronuclear (1H,13C-HMQC (heteronuclear multiple-quantum coherence experiment)) experiments were recorded and processed using standard Bruker software (XWINNMR, version 3.5).

RESULTS

Glucosylceramide from F. graminearum Contains Δ3(E)-Unsaturated Fatty Acids—GlcCer of F. graminearum strain PH-1 is known to contain Δ3(E)-unsaturated fatty acids (23). To check whether this is also true for the strain 8/1, which was used in this study, GlcCer was isolated, purified, and subjected to ESI FT-ICR MS analysis (data not shown). Scheme 1 shows the GlcCer structures as determined by NMR spectroscopy and ESI/MS. The native GlcCer, 1, had main peaks originating from [M+H]+ and [M+Na]+, yielding a molecular mass of 753.5785 Da, which is almost identical to the calculated mass for C43H79O9N (753.5755 Da). This mass is in agreement with fungal GlcCer containing the sphingoid base (4E,8E)-9-methylsphinga-4,8-dienine linked to a hydroxylated monounsaturated C18-fatty acid, 1. The same observations could be made with the peracetylated derivative of GlcCer, 2 (data not shown). The position and configuration of the double bond in the fatty acyl moiety was analyzed by NMR spectroscopy (for coupling constants, see supplemental Tables 1 and 2) and assigned as Δ3(E). Therefore, strain 8/1 was suitable for this study.

SCHEME 1.

GlcCer structures as determined by NMR and ESI/MS. The circled n refers to the heterogeneity of the fatty acid (C16 or C18).

The Extent of Δ3(E)-Unsaturation in Fusarium Varies with the Growth Temperature—Many fungi respond to decreasing temperatures with increasing unsaturation of membrane lipids (33). We thought it might be worthwhile to check whether the Δ3(E)-content of GlcCer in F. graminearum is also affected by variations in temperature. Therefore, F. graminearum strain 8/1 was grown in CM for 3 and 7 days at different temperatures, and the lipids were extracted. The composition of total fatty acids (supplemental Fig. 1) was analyzed by GLC and quantified. Linolenic acid (18:3) represented ∼30% of total fatty acids isolated from cells grown at 18 °C. With increasing growth temperature, the proportion of 18:3 decreased to 12% (28 °C) and 10% (30 °C), respectively. This is in line with the observations made by Suutari (33).

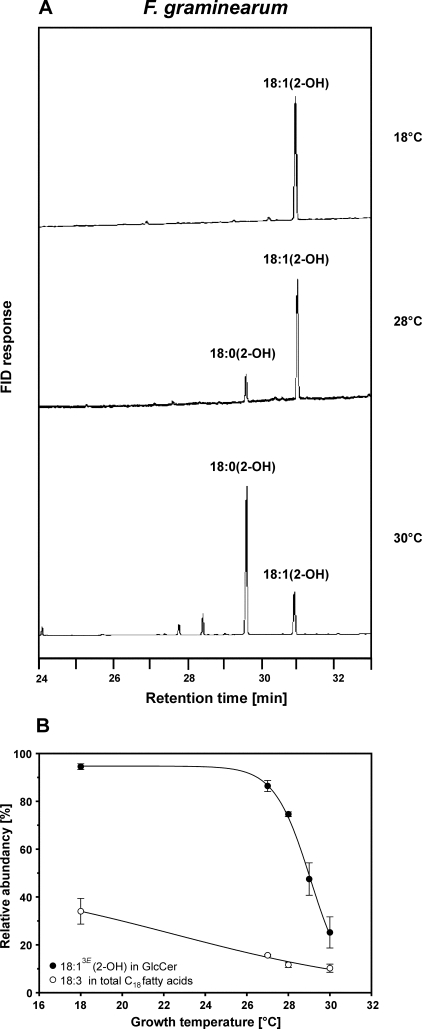

Because GlcCer represents only a small proportion of total lipids, the typical 2-hydroxy-unsaturated fatty acids could not be detected in the samples of total cellular fatty acids. Therefore, GlcCer was purified, and its fatty acids were analyzed using GLC (Fig. 2A), showing that the degree of unsaturation varied. GlcCer of cultures grown at 18 °C contained almost exclusively Δ3-unsaturated hydroxy fatty acids. At 28 °C, ∼75% of the hydroxy fatty acids were unsaturated, whereas the level of unsaturation decreased to 25% at a growth temperature of 30 °C. No differences in the extent of Δ3-unsaturated fatty acids in GlcCer were measured between cultures grown at the same temperature but for different incubation periods (3 or 7 days). The proportion of (3E)-double bonds in GlcCer of F. graminearum greatly changed within a very narrow temperature range (28-30 °C), which is in contrast to the continuously changing proportion of linolenic acid in phosphoglycerolipids (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

The extent of Δ3(E)-unsaturation in GlcCer of F. graminearum varies depending on the growth temperature. A, TMS-FAMEs were derived from GlcCer of F. graminearum grown at 18, 28, and 30 °C and analyzed by GLC. FID, flame ionization detector. B, relative amounts of 18:13E in fatty acids of GlcCer and of 18:3 in total C18 fatty acids. The level of Δ3(E)-unsaturation in GlcCer decreased significantly when F. graminearum was grown at temperatures above 28 °C. Data were obtained from at least two independent experiments.

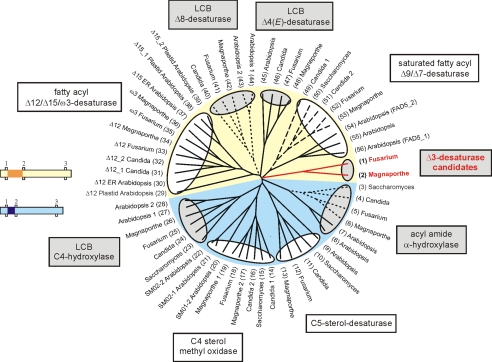

Identification of a Putative Sphingolipid Δ3(E)-Desaturase Family with Members from Euascomycete Fungi—A bioinformatics strategy developed by Ternes et al. (20) was adapted to identify candidate sequences for Δ3(E)-desaturases. Using PSI-BLAST with the S. cerevisiae sphingolipid α-hydroxylase Scs7p (14) and the Δ11-acyl group desaturase from T. pseudonana (25) as queries, a collection of sequences with the histidine box motifs was assembled. The final collection of desaturase-like sequences was grouped into families, and a putative biochemical function was assessed to each family based on published experimental results (Fig. 3). This led to the identification of one additional family matching the following criteria. 1) The family comprised only sequences with so far unknown function, 2) it was present in all completely sequenced genomes of euascomycetes, 3) it was missing in yeasts and in all other fungi, and 4) it was also missing in animals. Initially, the candidate family contained six sequences from A. fumigatus, A. nidulans, F. graminearum, M. grisea, and N. crassa, but with more sequenced genomes of euascomycetes being published, this number could be raised (supplemental Table 3).

FIGURE 3.

Dendrogram showing desaturase-like sequences from F. graminearum, M. grisea, Candida albicans, S. cerevisiae, and A. thaliana. Sphingolipid-modifying enzymes are shaded in gray, and the Δ3(E)-desaturase candidates are marked in red. Cytochrome b5-fusion proteins are indicated by dashed lines (C-terminal fusion) and dotted lines (N-terminal fusion), respectively. The yellow and light blue background indicates groups of desaturase and hydroxylase sequences distinguished by a different spacing between the first and the second histidine box. The small pictures illustrate the distance between these histidine boxes, which is 25-34 amino acids in the sequences with yellow background and 7-18 amino acids in the sequences with light blue background. The spacing is highlighted in dark yellow and dark blue, respectively. GenBank protein accession numbers are: 1) XP_383758, 2) XP_368852, 3) NP_013999, 4) XP_717303, 5) XP_385340, 6) XP_361446, 7) NM_129030, 8) NM_11820, 9) NP_192948, 10) NP_013157, 11) XP_713612, 12) XP_382678, 13) XP_363987, 14) XP_722703, 15) NP_011574, 16) XP_713456, 17) XP_360827, 18) XP_390006, 19) XP_369331, 20) NP_567670, 21) NP_850133, 22) NP_563789, 23) NP_010583, 24) XP_715359, 25) XP_382698, 26) XP_369735, 27) AAF43928, 28) AAG52550, 29) NP_194824, 30) NP_850139, 31) XP_722258, 32) XP_714324, 33) XP_385960, 34) XP_365283, 35) XP_388066, 36) XP_362963, 37) NP_180559, 38) NP_187727, 39) NP_196177, 40) XP_719958, 41) XP_390021, 42) XP_361026, 43) NP_182144, 44) AAD00895, 45) NP_192402, 46) XP_722116, 47) XP_390550, 48) XP_001404401, 49) XP_714854, 50) NP_011460, 51) XP_717653, 52) XP_386360, 53) XP_363864, 54) NP_565721, 55) BAC43716, and 56) NP_172098. ER, endoplasmic reticulum; LCB, long-chain base.

The polypeptide sequences of the candidate family vary in length between 400 and 500 amino acids. They neither possess a C-terminal nor an N-terminal cytochrome b5 domain, but they contain the three histidine boxes characteristic for membrane-bound desaturases. For all putative proteins, four transmembrane helices were predicted, using the program TMHMM (34). This is in line with topology predictions for other membrane-bound desaturases (Ref. 13, and reviewed in Ref. 35). Positions of the histidine boxes and putative transmembrane domains are shown in Fig. 4. Desaturases can generally be divided in two groups based on a different spacing between the first and the second histidine box. The Δ3(E)-desaturase candidate family belongs to the group with a long spacing like the sphingolipid-Δ4(E)- and the sphingolipid-Δ8-desaturases (Fig. 3). The α-hydroxylases, which were expected to be more closely related to Δ3-desaturases than other desaturases, however, belong to the group with short spacing. From the identified putative Δ3(E)-desaturase family, we selected the candidate protein from F. graminearum to elucidate its apparent enzymatic function.

FIGURE 4.

Sequence alignment of Δ3(E)-desaturase candidate polypeptide sequences from Δ3Fg, M. grisea (Δ3Mg), A. fumigatus (Δ3Af), and N. crassa (Δ3Nc). Histidine boxes and predicted transmembrane helices (TM-Helix) are indicated.

Cloning of the Candidate Sphingolipid-Δ3(E)-Desaturase Gene from F. graminearum—Genomic DNA isolated from F. graminearum strain 8/1 was used as a template for PCR. The complete open reading frame (including two predicted introns) coding for the candidate sequence was amplified and cloned into the vector pGEM®-T. Sequencing revealed seven alterations when compared with the published sequence Fg05382 (XP_383758) from the sequenced strain PH-1. These changes led to three amino acid differences in the predicted polypeptide, indicating variations between the isolates PH-1 and 8/1. Also, cDNA obtained from F. graminearum was amplified by PCR, cloned into pGEM®-T, and sequenced. Except for the introns, genomic and cDNA sequences were identical, both displaying the same differences to XP_383758 from strain PH-1. The genomic sequence and the cDNA sequence are deposited in GenBank™ under accession numbers FJ176922 (genomic DNA) and FJ176923 (cDNA).

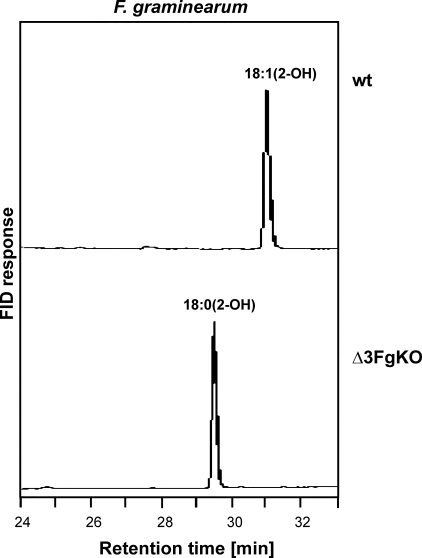

Deletion of the Δ3(E)-Desaturase Candidate Gene in F. graminearum Led to a Loss of Δ3-Unsaturated Fatty Acids in GlcCer—For a functional assignment of the newly cloned sequence of F. graminearum, a knock-out cassette was constructed. 5′- and 3′-flanking regions of the candidate gene were amplified by PCR and cloned into pGEM®-T. A selection marker cassette, providing resistance to hygromycin, was ligated into the BglII-restriction sites between the flanking regions. Protoplasts of F. graminearum were transformed with the linearized knock-out construct, and single colonies were checked for the correct integration of the knock-out cassette with PCR and Southern blotting. GlcCer of several deletion mutants were isolated, and their fatty acid compositions were analyzed by GLC (Fig. 5). The resulting fatty acid profiles were dominated by 2-hydroxyoctadecanoic acid, whereas Δ3(E)-unsaturated components were not detected. ESI FT-ICR MS analysis (data not shown) of the native GlcCer of the knock-out mutant, 3, resulted in main peaks originating from [M+H]+ and [M+Na]+, yielding a molecular mass of 755.5917 Da almost identical to the value calculated for C43H81O9N (755.5911 Da) and indicating GlcCer with a saturated fatty acyl moiety, 18:0(2-OH). The molecular mass corresponding to Δ3-unsaturated GlcCer was not detected. The obtained molecular mass for the peracetylated derivative, 4, was also almost identical to that calculated for GlcCer with a saturated C18 fatty acid (data not shown). These data show that the identified gene is essential for Δ3-unsaturation of GlcCer. To verify that it encodes the actual desaturase, the corresponding cDNA from F. graminearum was expressed in the yeast P. pastoris. The Heterologous Expression of the Candidate Gene from F. graminearum Resulted in the Formation of Δ3-Unsaturated Fatty Acids—Ceramide or GlcCer of P. pastoris was considered as a suitable substrate for the putative Δ3(E)-desaturase because the only difference to the corresponding sphingolipids from F. graminearum is the missing Δ3-double bond. The complete open reading frame of the candidate cDNA of F. graminearum was cloned into the P. pastoris expression vector pPIC3.5 under control of the inducible AOX1 promoter. The plasmid was linearized and used for transformation of P. pastoris strain GS115. GlcCer was isolated from several P. pastoris transformants and used for fatty acid analysis. As shown in Fig. 6, the expression of the heterologous desaturase from F. graminearum (Δ3Fg) led to the formation of unsaturated fatty acids. The amide-linked fatty acyl moiety of GlcCer consisted of 50-100% 2-hydroxyoctadecenoic acid, 18:1(2-OH). This level of unsaturation in P. pastoris cells expressing Δ3Fg is remarkably high when compared with the activity of other desaturases in heterologous expression systems (20).

FIGURE 5.

Deletion of the Δ3(E)-desaturase candidate gene in F. graminearum led to a loss of unsaturated fatty acids in GlcCer. TMS-FAMEs were derived from GlcCer of F. graminearum grown at 18 °C and analyzed by GLC. The knock-out mutant (Δ3FgKO) lacked the double bond in the hydroxyfatty acid. FID, flame ionization detector; wt, wild type.

FIGURE 6.

Heterologous expression of the candidate gene from F. graminearum in P. pastoris resulted in the formation of Δ3(E)-unsaturated fatty acids. Fatty acids from GlcCer isolated from P. pastoris transformants were analyzed by GLC as TMS-FAMEs. Δ3Fg converted 2-hydroxyoctadecanoic acid 18:0(2-OH), efficiently (50-100%) into 2-hydroxyoctadecenoic acid, 18:1(2-OH). FID, flame ionization detector; wt, wild type.

The identity of the fatty acids isolated from GlcCer of P. pastoris wild type and the expression mutant indicated in Fig. 6 was confirmed by ESI FT-ICR MS analysis, and the latter was also confirmed by NMR spectroscopy. Upon ESI FT-ICR MS analysis, P. pastoris wild type GlcCer, 5, was found to have the same peaks as detected for the GlcCer of the F. graminearum knockout mutant, 3, however with different intensities (data not shown). By contrast, in GlcCer of P. pastoris cells expressing Δ3Fg, 7, the same molecular mass as for GlcCer of F. graminearum wild type, 1, was identified, being in agreement with GlcCer containing 18:1(2-OH) (data not shown). These data were further corroborated by the ESI FT-ICR MS analysis of the peracetylated GlcCer derivatives of P. pastoris wild type and the mutant expressing Δ3Fg, 6 and 8, clearly revealing that the identified sequence encodes a desaturase.

To determine the position and configuration of the double bond introduced by the enzyme, NMR analysis was performed both with the native and with the peracetylated GlcCer isolated from P. pastoris expressing Δ3Fg, 7, 8 (supplemental Tables 1 and 2). In the 1H NMR spectrum, signals characteristic for the double bond between H-3′ and H-4′ assigned to the 2-hydroxy fatty acid showed diagnostic coupling constant for the (E)-configuration in the native (J3,4 = 15.3 Hz) and in the peracetylated (J3,4 = 14.3 Hz) GlcCer. These were further supported by downfield shifts of the protons (supplemental Table 1) as well as the corresponding 13C resonances in the HMQC spectrum for C-3′ and C-4′, respectively (supplemental Table 2). All other signals were in good agreement with published data for the native GlcCer (6, 23) and the peracetylated derivative (36-38).

To complete the structural analysis, we further investigated the stereochemical position of the 2-hydroxy group in the fatty acid of GlcCer from P. pastoris and F. graminearum. GLC-MS analysis of the diastereomeric methoxy fatty acid-(S/R)-phenylethylamides clearly revealed that the 2-hydroxy fatty acids were all (R)-configurated (not shown), in contrast to 2-hydroxy fatty acids found in bacterial GlcCer, where the configuration is usually (S), as described for example in Ref. 39. Based on these results, we could identify the unsaturated GlcCer as N-(R)-2′-hydroxy-(3E)-octadec-3-enoyl-1-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(4E, 8E)-9-methyl-sphinga-4,8-dienine.

DISCUSSION

Δ3(E)-Double bonds are present in different classes of lipids (Fig. 1), such as fungal glycosylceramide, plant plastidial phosphatidyl-glycerol, and triacylglycerol from seeds of some higher plants. Therefore, we expected to find sequences both from fungi and from plants in the bioinformatics analysis. However, our strategy led to the identification of a desaturase subfamily, which contains exclusively sequences from euascomycetes, coding for acylamide-Δ3(E)-desaturases. No plant homologue has been found, which would have been expected at least for fully sequenced and annotated genomes like Arabidopsis thaliana. This indicates that the putative PG-Δ3(E)-desaturase (fad4) is of different origin.

In this study, we describe the identification and molecular characterization of the first desaturase with Δ3(E)-regioselectivity. The enzyme introduces the double bond into an α-hydroxy fatty acyl moiety of fungal sphingolipids. The vicinal 2-hydroxy group in the sphingolipid is most likely required for the Δ3-desaturase activity.

The biological functions of Δ3-double bonds in plastidial PG and fungal sphingolipids are not known. The fatty acid composition of plant plastidial PG is supposed to be important for chilling tolerance of plants (40, 41) and electron transport in photosystem II (reviewed in Ref. 42). However, the Δ3(E)-unsaturation in position sn2 is not crucial for these effects. A chemical mutant of A. thaliana lacking the Δ3(E)-double bond in PG does not show a conspicuous phenotype regarding both chilling sensitivity and photosynthesis (43). The physical properties of the plastidial membrane are only slightly influenced by the introduction of a Δ3(E)-double bond into PG (44).

We analyzed whether Δ3(E)-unsaturation in F. graminearum is temperature-dependent and found that a shift in growth temperature from 28 to 30 °C resulted in a dramatic decrease of Δ3(E)-unsaturated fatty acids in GlcCer, whereas the composition of total fatty acids remained almost unchanged. This substantial change in Δ3(E)-unsaturation probably does not reflect an adaptation of membrane fluidity to varying temperatures, which has been described for Z-unsaturation in phosphoglycerolipids (33). These data rather suggest that the regulation of the Δ3-desaturase differs from those of other fatty acid desaturases. The observed decrease in the level of unsaturation of GlcCer between 28 and 30 °C is not due to a temperature sensitivity of the enzyme because full activity could be achieved by heterologous expression in P. pastoris both at 28 °C and at 30 °C.

It seems likely that the Δ3(E)-desaturase is specifically regulated by an unknown mechanism and may play a role in signaling processes. However, the Δ3(E)-knock-out strain of F. graminearum does not show any obvious phenotype, and more detailed analyses of the mutant are required to ascertain the functions of the Δ3(E)-desaturase for the life cycle of the fungus.

Because GlcCer from yeasts and filamentous fungi is critical for the activity of antifungal peptides (AFPs) from plants and insects (23, 45), we determined the growth inhibitory effect of two AFPs from the plant Raphanus sativus and the fungus Aspergillus giganteus. Although the F. graminearum wild type was sensitive to both AFPs, the Δ3(E)-knock-out strain interestingly became resistant. In addition, the P. pastoris strain expressing the Δ3-desaturase from Fusarium became hypersensitive to both AFPs (in comparison with the wild type). These data indicate that the Δ3(E)-double bond in GlcCer is important for the interaction of the fungus with AFPs from R. sativus and A. giganteus. We will describe the experiments in a separate study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Wiebke Hellmeyer for skillful technical assistance, Hermann Moll for excellent GLC-MS analysis, and Ernst Heinz for fruitful discussions.

This paper is dedicated to the memory of our colleague Petra Sperling.

The nucleotide sequence(s) reported in this paper has been submitted to the GenBank™/EBI Data Bank with accession number(s) FJ176922 and FJ176923.

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grant SP 967/1-1 (to S.Z.), Grant Li 448/1-4 (to B. L. and U. Z.), and Grant SFB470. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains three supplemental tables and a supplemental figure.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: GlcCer, glucosylceramide; GalCer, galactosylceramide; ESI FT-ICR MS, electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry; GLC, gas liquid chromatography; GLC-MS, gas chromatography-mass spectrometry; FAME, fatty acid methyl ester; TMS-FAMEs, trimethylsilylated FAMEs; PG, phosphatidylglycerol; Δ3Fg, Δ3(E)-desaturase candidate from F. graminearum; CM, complete minimal medium; AFP, antifungal peptide; 18:0, stearic acid; 18:1, oleic acid; 18:3, α-linolenic acid; 18:0(2-OH), 2-hydroxyoctadecanoic acid; 18:1(2-OH), 2-hydroxyoctadecenoic acid.

References

- 1.Borner, G. H., Sherrier, D. J., Weimar, T., Michaelson, L. V., Hawkins, N. D., Macaskill, A., Napier, J. A., Beale, M. H., Lilley, K. S., and Dupree, P. (2005) Plant Physiol. 137 104-116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laloi, M., Perret, A. M., Chatre, L., Melser, S., Cantrel, C., Vaultier, M. N., Zachowski, A., Bathany, K., Schmitter, J. M., Vallet, M., Lessire, R., Hartmann, M. A., and Moreau, P. (2007) Plant Physiol. 143 461-472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sperling, P., Franke, S., Lüthje, S., and Heinz, E. (2005) Plant Physiol. Biochem. 43 1031-1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sperling, P., and Heinz, E. (2003) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1632 1-15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warnecke, D., and Heinz, E. (2003) CMLS Cell Mol. Life Sci. 60 919-941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toledo, M. S., Levery, S. B., Straus, A. H., Suzuki, E., Momany, M., Glushka, J., Moulton, J. M., and Takahashi, H. K. (1999) Biochemistry 38 7294-7306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toledo, M. S., Levery, S. B., Straus, A. H., and Takahashi, H. K. (2000) J. Lipid Res. 41 797-806 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toledo, M. S., Levery, S. B., Suzuki, E., Straus, A. H., and Takahashi, H. K. (2001) Glycobiology 11 113-124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohlrogge, J., and Browse, J. (1995) Plant Cell 7 957-970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bagby, M. O., Siegel, W. O., and Wolff, I. A. (1965) J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 42 50-53 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kleiman, R., Earle, F. R., and Wolff, I. A. (1966) Lipids 1 301-304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kleiman, R., Spencer, G. F., Tjarks, L. W., and Earle, F. R. (1971) Lipids 6 617-622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunn, T. M., Haak, D., Monaghan, E., and Beeler, T. J. (1998) Yeast 14 311-321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haak, D., Gable, K., Beeler, T., and Dunn, T. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 29704-29710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leipelt, M., Warnecke, D., Zähringer, U., Ott, C., Müller, F., Hube, B., and Heinz, E. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 33621-33629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell, A. G., and Martin, C. E. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 28281-28288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sperling, P., Libisch, B., Zähringer, U., Napier, J. A., and Heinz, E. (2001) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 388 293-298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sperling, P., Ternes, P., Moll, H., Franke, S., Zähringer, U., and Heinz, E. (2001) FEBS Lett. 494 90-94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sperling, P., Zähringer, U., and Heinz, E. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 28590-28596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ternes, P., Franke, S., Zähringer, U., Sperling, P., and Heinz, E. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 25512-25518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ternes, P., Sperling, P., Albrecht, S., Franke, S., Cregg, J. M., Warnecke, D., and Heinz, E. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 5582-5592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shanklin, J., Whittle, E., and Fox, B. G. (1994) Biochemistry 33 12787-12794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramamoorthy, V., Cahoon, E. B., Li, J., Thokala, M., Minto, R. E., and Shah, D. M. (2007) Mol. Microbiol. 66 771-786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Altschul, S. F., Madden, T. L., Schaffer, A. A., Zhang, J., Zhang, Z., Miller, W., and Lipman, D. J. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res. 25 3389-3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tonon, T., Harvey, D., Qing, R., Li, Y., Larson, T. R., and Graham, I. A. (2004) FEBS Lett. 563 28-34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson, J. D., Gibson, T. J., Plewniak, F., Jeanmougin, F., and Higgins, D. G. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res. 25 4876-4882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miedaner, T., Reinbrecht, C., and Schilling, A. G. (2000) J. Plant Dis. Prot. 107 124-134 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nirenberg, H. I. (1981) Can. J. Bot. 59 1599-1609 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leach, J., Lang, B. R., and Yoder, O. C. (1982) J. Gen. Microbiol. 128 1719-1729 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maier, F. J., Malz, S., Lösch, A. P., Lacour, T., and Schäfer, W. (2005) FEMS Yeast Res. 5 653-662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rietschel, E. T. (1976) Eur. J. Biochem. 64 423-428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wollenweber, H. W., Schramek, S., Moll, H., and Rietschel, E. T. (1985) Arch. Microbiol. 142 6-11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suutari, M. (1995) Arch. Microbiol. 164 212-216 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krogh, A., Larsson, B., von Heijne, G., and Sonnhammer, E. L. (2001) J. Mol. Biol. 305 567-580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sperling, P., Ternes, P., Zank, T. K., and Heinz, E. (2003) Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 68 73-95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duarte, R. S., Polycarpo, C. R., Wait, R., Hartmann, R., and Bergter, E. B. (1998) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1390 186-196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakaki, T., Zähringer, U., Warnecke, D. C., Fahl, A., Knogge, W., and Heinz, E. (2001) Yeast 18 679-695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Villas Boas, M. H. S., Egge, H., Pohlentz, G., Hartmann, R., and Bergter, E. B. (1994) Chem. Phys. Lipids 70 11-19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kawahara, K., Moll, H., Knirel, Y. A., Seydel, U., and Zähringer, U. (2000) Eur. J. Biochem. 267 1837-1846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murata, N. (1983) Plant Cell Physiol. 24 81-86 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kenrick, J. R., and Bishop, D. G. (1986) Plant Physiol. 81 946-949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wada, H., and Murata, N. (2007) Photosynth. Res. 92 205-215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Browse, J., McCourt, P., and Somerville, C. R. (1985) Science 227 763-765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barton, P. G., and Gunstone, F. D. (1975) J. Biol. Chem. 250 4470-4476 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thevissen, K., Warnecke, D. C., Francois, I. E., Leipelt, M., Heinz, E., Ott, C., Zähringer, U., Thomma, B. P., Ferket, K. K., and Cammue, B. P. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 3900-3905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.