Abstract

MMP13 is enriched in mature chondrocytes and considered a prime cause of ECM degradation in the osteoarthritic articular cartilage in temporomandibular joints. We asked whether surviving stress to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) would upregulate transcription of MMP13, and if so, whether a cross-talk would exist between surviving ER stress and p38 MAPK pathways. Using C28/I2 chondrocyte cell line, ER stress was induced by thapsigargin and tunicamycin and upregulation of phosphorylated eIF2α and ATF4 protein was observed. Both thapsigargin and tunicamycin elevated the mRNA level of MMP13 and phosphorylation of p38 MAPK. Thapsigargin-induced MMP13 mRNA upregulation was significantly suppressed by SB203580, while its upregulation by tunicamycin was completely attenuated by SB203580. Those results support that homeostasis of chondrocytes is affected by the surviving ER stress through p38 MAPK pathways, suggesting a potential role of ER stress in joint diseases such as osteoarthritis.

Keywords: chondrocytes, ER stress, MMP13, p38 MAPK

1. Introduction

The efficient functioning of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is essential to cellular homeostasis [1]. The ER is the entry site for protein delivery, and therefore stress to the ER is tightly regulated particularly in professional secretory cells such as antibody-secreting plasma cells and collagen-secreting osteoblasts. Chondrocytes are such secretory cells responsible for synthesis and turnover of extracellular matrix (ECM) molecules [2]. Although strong ER stress induces apoptosis [3], surviving ER stress is often linked to chronic disorders such as obesity and type II diabetes [4]. In rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis, two collagenases (MMP1 and MMP13) have a predominant role in destruction of the cartilage. Inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α are considered to be the prime inducers of collagenases through intracellular signaling pathways involving MAPKs, and NF-κB. Despite studies on MMPs at varying regulatory levels in chondrocytes [5, 6], little is known about effects of surviving ER stress that is unlinked to inflammatory cytokines.

In the present study we investigated the responses of the immortalized human chondrocyte cell, line C-28/I2 [7] to surviving ER stress, where the protein level of phosphorylated eukaryotic translation initiation factor-2α (eIF2α) [8] as well as ATF4 were elevated without inducing apoptosis. Primarily focusing on a group of matrix-remodeling genes that are known to be affected by IL-1 in articular cartilage, we addressed a pair of questions: Does surviving ER stress alter the mRNA level of collagenases such as MMP1 and MMP13 as well as the mRNA level of chondrocyte specific genes such as type II and X collagens, and aggrecan? And, does p38 MAPK, which are critical in the responses to inflammatory cytokines [9, 10], mediate the responses to survival after ER stress?

We employed thapsigargin and tunicamycin as two independent inducers of ER stress. Thapsigargin is an inhibitor of sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase [11], and tunicamycin is an inhibitor of N-linked glycosylation and the formation of N-glycosidic protein-carbohydrate linkages [12]. We used those two inducers, since previous studies report differential stress effects induced by thapsigargin and tunicamycin [13]. In order to examine a potential linkage between the responses by the surviving ER stress to ECM degradation by inflammatory cytokines in chronic joint diseases, we particularly evaluated regulation of MMP13 mRNA in the presence and the absence of a p38 MAPK inhibitor, SB203580 [14].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell culture and treatments with thapsigargin and tunicamycin

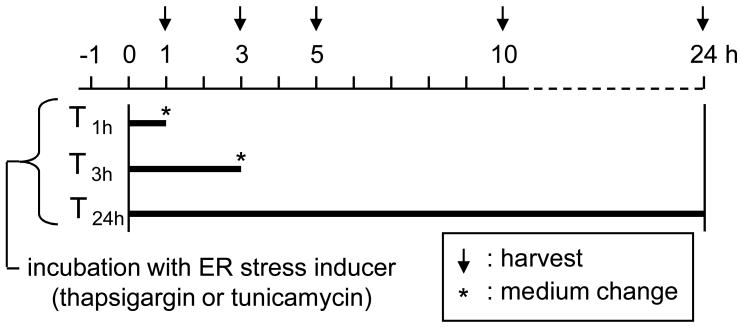

C-28/I2 human chondrocytes were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing10% FBS and antibiotics (50 units/ml penicillin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin; Invitrogen). Cells were incubated at 37°C in a humid chamber with 5 % CO2 and cultured for experiments at 70–80% confluency. Approximately 4 × 105 cells were treated in a 60-mm plastic dish (Falcon) with thapsigargin (Santa Cruz Biotech.) at 0.1 nM to 1 μM or tunicamycin (MP Biomedicals) at 0.01 to 3 μg/ml. The treatment duration was 1 h (T1h), 3 h (T3h), or 24 h (T24h). After the treatment, cells were rinsed three times and incubated in the medium without any inducer for various times (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Timeline for incubation with an ER stress inducer (thapsigargin or tunicamycin).

Activities of p38 MAPK were inhibited via 30 min pre-incubation with 10 μM SB203580 (Calbiochem). Cells were then incubated with 10 nM thapsigargin or 1 μg/ml tunicamycin for 1 h in the presence of SB203580. They were harvested 3 h and 5 h after the onset of incubation with thapsigargin and tunicamycin, respectively.

2.2. Reverse transcription and real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy Plus mini kit (Qiagen). Using approximately 50 ng of total RNA, reverse transcription was conducted with high capacity cDNA reverse transcription kits (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using ABI 7500 with Power SYBR green PCR master mix kits (Applied Biosystems). We evaluated the mRNA levels of ER stress responsive genes (ATF3, ATF4, CHOP, and GADD45β), collagenases (MMP1 and MMP13), chondrogenic genes (Sox9, Col2A1, and Aggrecan), hypertrophic genes (Runx2 and Col10A1) and GAPDH with the PCR primers listed in Table 1. GAPDH was used for internal control, and the results were interpreted using a delta CT method [11]. The relative mRNA abundance for the selected genes with respect to the level of GAPDH mRNA was expressed as a ratio of Streated/Scontrol, where Streated = mRNA level for the cells treated with thapsigargin or tunicamycin, and Scontrol = mRNA level for control cells.

Table 1.

Real-Time PCR primers

| Gene | forward primer | backward primer |

|---|---|---|

| ATF4 | 5′- TCAAACCTCATGGGTTCTCC -3′ | 5′- GTGTCATCCAACGTGGTCAG -3′ |

| ATF3 | 5′- TGATGCTTCAACACCCAGGCC -3′ | 5′- AGGGGACGATGGCAGAAGCA -3′ |

| CHOP | 5′- TGCCTTTCTCTTCGGACACT -3′ | 5′- TGTGACCTCTGCTGGTTCTG -3′ |

| GADD45β | 5′- CGGTGGAGGAGCTTTTGGTG -3′ | 5′- CACCCGCACGATGTTGATGT -3′ |

| Sox9 | 5′- CATGAGCGAGGTGCACTCC -3′ | 5′- TCGCTTCAGGTCAGCCTTG -3′ |

| Runx2 | 5′- AACCCACGAATGCACTATCCA -3′ | 5′- CGGACATACCGAGGGACATG -3′ |

| Col2A1 | 5′- TACCACTGCAAGAACAGC -3′ | 5′- GTGCAATGTCAATGATGG -3′ |

| Col10A1 | 5′- CAGGCAACAGCATTATGACC -3′ | 5′- CATTTGACTCGGCATTGG -3′ |

| Aggrecan | 5′- GACAGACTTGAGGGGGAGGT -3′ | 5′- GCAGTGGCATTGTGAGATTC -3′ |

| MMP1 | 5′- TACACGGATACCCCAAGGACAT -3′ | 5′- CCTCAGAAAGAGCAGCATCGA -3′ |

| MMP13 | 5′- AATATCTGAACTGGGTCTTCCAAAA -3′ | 5′- CAGACCTGGTTTCCTGAGAACAG -3′ |

| GAPDH | 5′- GCACCGTCAAGGCTGAGAAC -3′ | 5′- ATGGTGGTGAAGACGCCAGT -3′ |

2.3. Immunoblots

Cells were sonicated using a sonic dismembrator (Model 100; Fisher Scientific) and lysed in a RIPA lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors (Santa Cruz Biotech.) and phosphatase inhibitors (Calbiochem.). Isolated proteins were fractionated using 10 % SDS gels and electro-transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore). The membrane was incubated for 1 h with primary antibodies followed by 45 min incubation with goat anti-rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling Tech.) or goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Amersham) (1:2000 dilution). We used antibodies against ATF4 and MMP13 (Santa Cruz Biotech.), eIF2α-p (pS52; Biosource), eIF2α, active and inactive caspase 3, and p38 MAPK (Cell Signaling Tech.), and anti β-actin (Sigma). Protein levels were assayed using an ECL advance western blotting detection kit (Amersham Biosciences) and signal intensities were quantified with a luminescent image analyzer (LAS-3000, Fuji Film). The protein levels of eIF2α-p, ATF4, and MMP13 were normalized based on the level of total eIF2α (for eIF2α-p) and β-actin (for ATF4 and MMP13).

2.4. Assay for cellular proliferation and cell death

Cells were plated in the plastic dish and incubated 24 h. They were then treated with thapsigargin or tunicamycin. Cellular proliferation and death were observed 24 h after the treatment using an optical microscope (Eclipse TS100; Nikon). Cells were stained with trypan blue, and the number of live and dead cells was counted using a hemacytometer.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Regarding mRNA analyses, three independent experiments were conducted and for each experiment four separate PCR runs were carried out. For Western blots, two independent experiments were performed and signals were quantified by determining mean pixel intensities in a gray code (0 – 255 levels) using Adobe Photoshop (version 6.0; Adobe Systems). The data were expressed as mean ± s.d., and for comparison among multiple samples ANOVA followed by post ad hoc tests was conducted.

3. Results

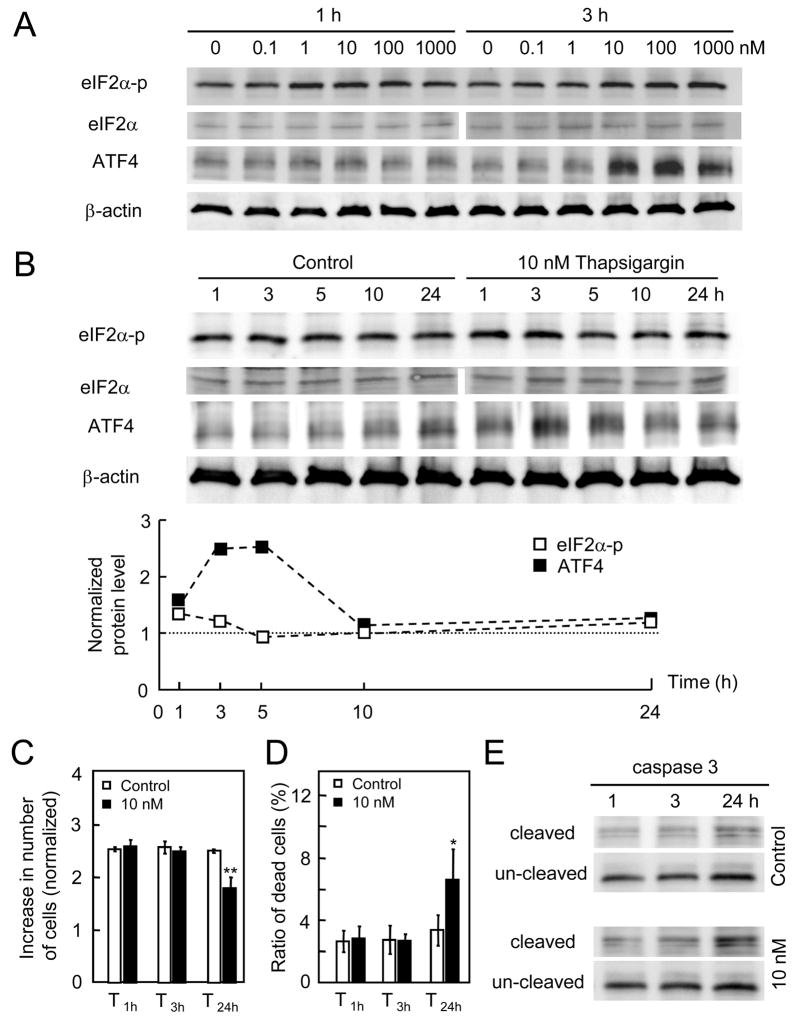

3.1. Elevated protein level of eIF2α-p and ATF4 in response to thapsigargin

In order to impose non-apoptotic ER stress, we searched for the proper treatment condition with thapsigargin that activated translational regulation through the elevated protein levels of eIF2α-p and ATF4 without causing cellular death. In response to administration of thapsigargin at 1 nM to 1 μM for 1 h and 3 h, the protein levels of both eIF2α-p and ATF4 were elevated (Fig. 2A). The increase of ATF4 was significantly higher at concentrations of 10 nM or greater. Using 10 nM thapsigargin, the temporal expression profile of eIF2α-p, eIF2α, and ATF4 was determined (Fig. 2B). Among the time points at 1, 3, 5, 10, and 24 h, the peak expression occurred at 1 h (eIF2α-p) and 3–5 h (ATF4). Those results indicated that the lowest thapsigargin concentration inducible of ER stress was 10 nM.

Figure 2.

Responses to thapsigargin. (A) Protein expression of eIF2α-p, eIF2α, and ATF4 in response to thapsigargin at 0.1, 1, 10, 100 nM and 1 μM for 1 and 3 h incubation. (B) Temporal expression profile of eIF2α-p, eIF2α, and ATF4 in response to 10 nM thapsigargin for 1 – 24 h. (C) Number of live cells in response to 10 nM thapsigargin for 3 and 24 h. (D) Number of dead cells induced by the treatment with 10 nM thapsigargin for 1, 3 and 24 h. (E) Protein expression of caspase 3 (inactive form of pro-caspase 3, and cleaved form of caspase 3) for 1, 3 and 24 h.

3.2. Cellular proliferation and mortality to thapsigargin

For the treatment with 10 nM thapsigargin, we next evaluated the effects of incubation time on cellular proliferation and mortality. A continuous exposure for 24 h reduced the number of live cells, but a shorter exposure for 1 and 3 h followed by incubation in the medium without thapsigargin did not alter the number of live cells or dead cells (Fig. 2C & 2D). Examination of pro-caspase 3 and its cleaved form revealed that exposure to 10 nM thapsigargin for 24 h stimulated expression of an active form of caspase 3 (Fig. 2E). Hereafter, we treated cells with thapsigargin at 10 nM for 1 and 3 h (T1h, and T3h) to induce surviving ER stress.

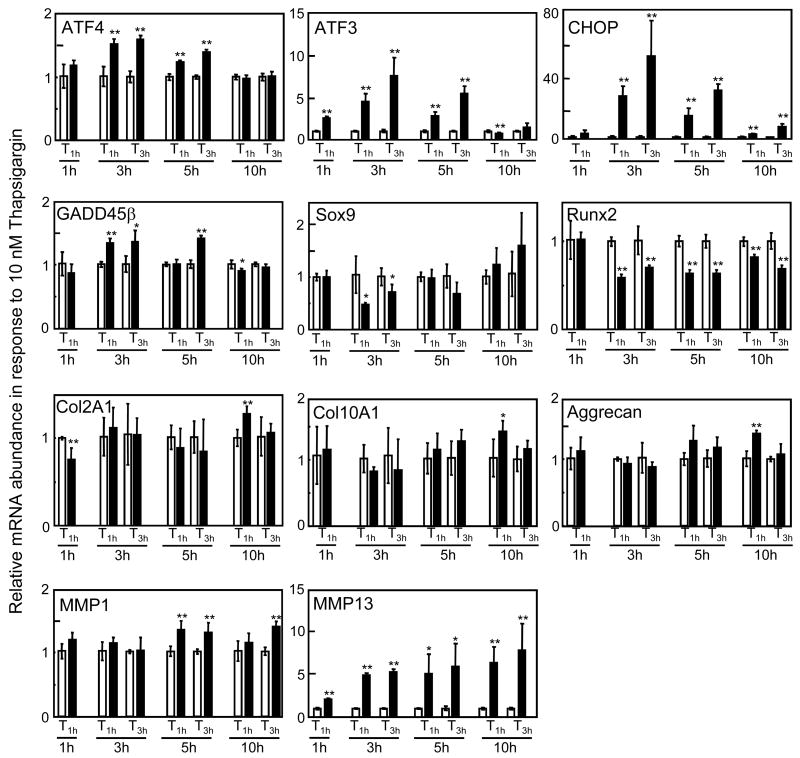

3.3. Expression of mRNA in response to thapsigargin-induced surviving ER stress

In response to surviving thapsigargin-induced ER stress that did not alter the number of live and dead cells, we examined mRNA expression levels of 11 genes (4 ER stress responsive genes, 2 collagenase genes, 3 chondrogenic genes, and 2 hypertrophic genes) at 4 time points (1, 3, 5, and 10 h) after initiation of the treatment (Fig. 3). A significant increase of > 2-fold was observed in expression of ATF3 (1 – 5 h), CHOP (3 – 10 h), and MMP13 (1 – 10 h), where T3h gave a higher mRNA level than T1h. The mRNA levels of ATF4 (3 and 5 h), GADD45β (3, and 5 h), and MMP1 (5, and 10 h) were significantly elevated, although the increases were ~ 50% or less. The mRNA levels of Col2A1, Col10A1, and aggrecan were mostly unchanged except for slight elevation for T1h at 10 h. Expression of Sox9 mRNA and Runx2 mRNA was unchanged or decreased by thapsigargin-induced surviving ER stress. Those results revealed that thapsigargin-induced surviving ER stress altered expression of ER stress responsive and collagenase genes but not chondrogenic or hypertrophic genes.

Figure 3.

Relative mRNA abundance in response to 10 nM thapsigargin for 1 h (T1h) and 3 h (T3h). The data includes the relative mRNA level, assayed 1, 3, 5, and 10 h after the onset of the treatment for ATF4, ATF3, CHOP, GADD45β, Sox9, Runx2, Col2A1, Col10A1, Aggrecan, MMP1, and MMP13. The asterisks indicate p < 0.05 (*) and p < 0.01 (**).

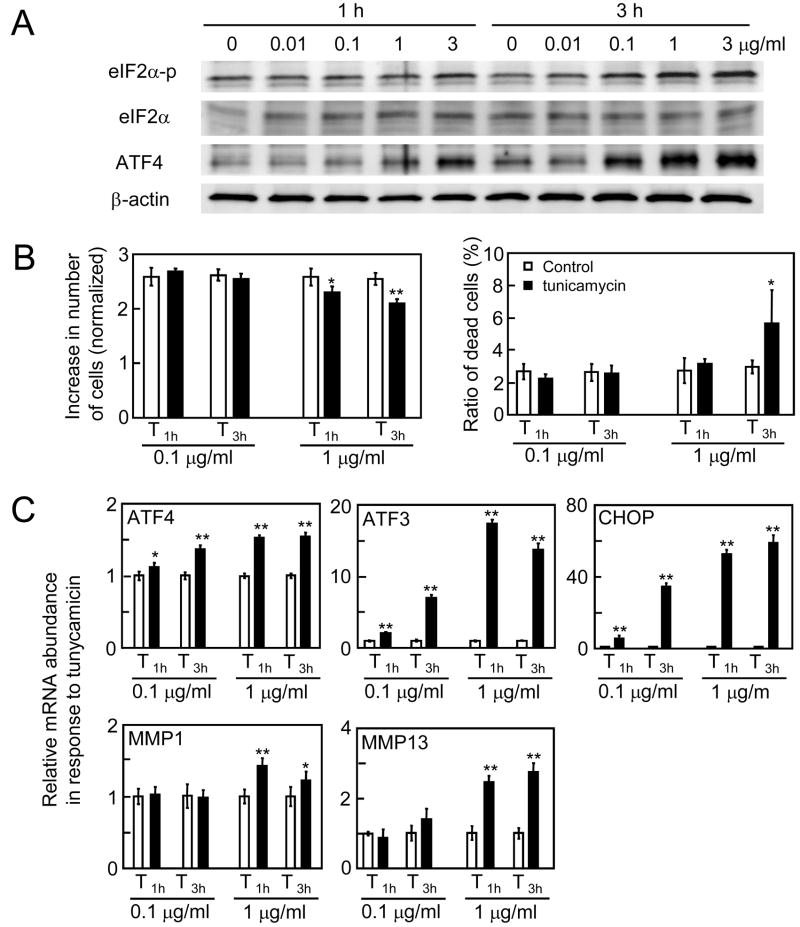

3.4. Responses to tunicamycin-induced ER stress

In response to tunicamycin that causes ER stress by blocking a particular process of glycosylation (usually keeps proteins that need to be glycosylated from being secreted), the level of eIF2α-p and ATF4 proteins were upregulated at 0.1 μg/ml and higher concentrations (Fig. 4A). The tunicamycin treatment at 0.1 μg/ml for 1 and 3 h did not alter the number of live or dead cells in 24 h, while exposure to 1 μg/ml tunicamycin reduced the number of live cells (Fig. 4B). The number of dead cells was increased by 3 h treatment at 1 μg/ml but not by 1 h administration. We hereafter used 1 μg/ml tunicamycin for 1 h (T1h) as a condition for surviving ER stress. The mRNA expression analysis revealed that the levels of ATF4, ATF3, CHOP, MMP1, and MMP13 mRNA were elevated in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Responses to tunicamycin. (A) Protein expression of eIF2α-p, eIF2α, and ATF4 in response to tunicamycin at 0.01, 0.1, 1, and 3 μg/ml for 1 and 3 h. (B) Number of live cells and dead cells induced by the treatment with 0.1 and 1 μg/ml tunicamycin for 1 and 3 h. (C) Relative mRNA abundance of ATF4, ATF3, CHOP, MMP1, and MMP13 by tunicamycin treatments at 0.1 and 1 μg/ml for 1 and 3 h. Cells were harvested 5 h after the onset of the treatment. The asterisks indicate p < 0.05 (*) and p < 0.01 (**).

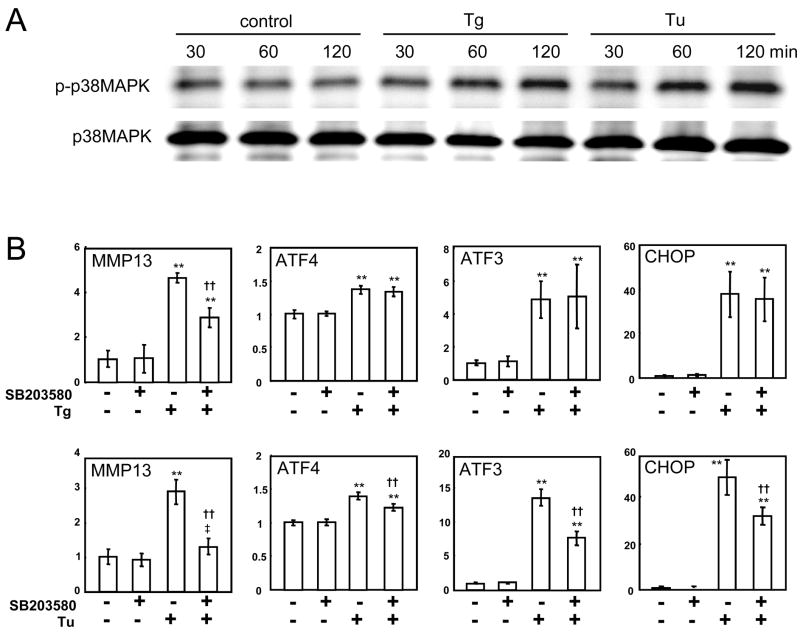

3.5. Phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and Effects of SB203580

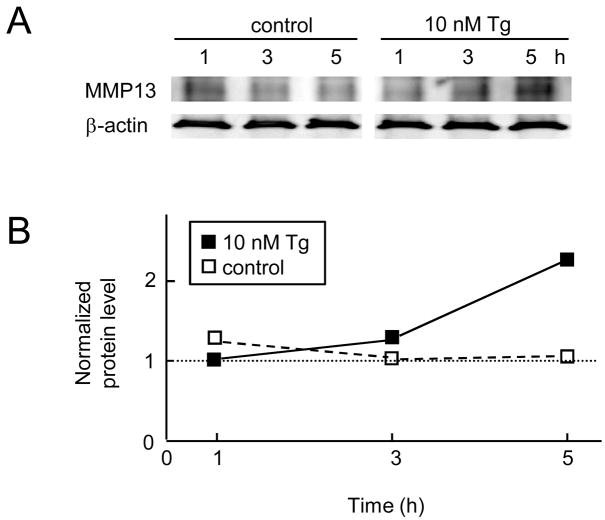

In order to examine involvement of p38 MAPK pathways in the observed mRNA upregulation, we evaluated the level of its phosphorylated form (Fig. 5A). The results showed that phosphorylation of p38 MAPK was elevated by both thapsigargin and tunicamycin 1 h after the treatment and its level was maintained high after 2 h. To further investigate the role of p38 MAPK in regulation of MMP13 mRNA, we pretreated the C-28/I2 cells with SB203580 for 30 min before 1 h treatment with thapsigargin or tunicamycin (T1h). The results revealed that SB203580 suppressed the upregulation of MMP13 mRNA induced by thapsigargin and tunicamycin by 49% and 84%, respectively (Fig. 5B). The thapsigargin-induced elevation of ATF4, ATF3 and CHOP mRNA was not affected, while their upregulation by tunicamycin was significantly suppressed (Fig. 5B). In consistent with the observed upregulation of MMP13 mRNA, the level of MMP13 protein was elevated 2.3-fold at 5 h in response to the treatment with 10 nM thapsigargin (Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

Elevation of p38 MAPK phosphorylation and effects of SB203580. (A) Upregulation of phosphorylated p38 MAPK by 1 h administration of 10 nM thapsigargin or 1 μg/ml tunicamycin. (B) Effects of SB203580. The symbols are: ** (p < 0.01 to no ER stress conditions with and without p38 MAPK inhibitor), †† (p < 0.01 to surviving ER stress without p38 MAPK inhibitor), and ‡ (p < 0.05 to no ER stress conditions with p38 MAPK inhibitor). Tg = thapsigargin, and Tu = tunicamycin. Cells were harvested 3 h and 5 h after the onset of the treatment with thapsigargin and tunicamycin, respectively.

Figure 6.

Upregulation of MMP13 protein by 1 h administration of 10 nM thapsigargin. (A) MMP13 expression assayed 1, 3, and 5 h after the onset of the treatment. (B) MMP13 expression level normalized by its level at 1 h in the presence of 10 nM thapsigargin.

4. Discussion

The present study shows that 1 h of incubation with 10 nM thapsigargin or 1 μg/ml tunicamycin activates phosphorylation of eIF2α without inducing apoptosis in chondrocytes. Under these conditions, which promote survival after ER stress, the levels of MMP13 mRNA are significantly upregulated together with the levels of ATF3, ATF4, and CHOP mRNA. The level of MMP13 protein was also elevated by the treatment with thapsigargin. Upregulation of tunicamycin-induced MMP13 mRNA is substantially suppressed by SB203580, while its upregulation by thapsigargin is reduced to nearly one half by SB203580. Those results reveal a novel route of regulation of MMP13, which is mediated through signaling cascade common to those induced by IL-1 and TNFα together with mechanical loading [15–17].

Two collagenases, MMP1 and MMP13 investigated in this study, are major contributors to destruction of the cartilage, tendon, and bone in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis [5]. Those collagenases can be induced not only by inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 but also by environmental stress including mechanical stimuli [9]. In response to surviving ER stress, the levels of both MMP1 and MMP13 mRNA were significantly induced but the increase of MMP13 mRNA was several-fold higher than that of MMP1. MMP1 is secreted by synovial cells in the lining of the joints, while MMP13 is primarily synthesized in chondrocytes [18]. MMP13 provides not only a rate limiting step in collagen degradation but also degrades non-collagen matrix proteins such as proteoglycan and aggrecan. The current study supports that surviving ER stress contributes to the stimulation of two collagenases in chondrocytes.

Potential inducers of ER stress in chondrocytes include stresses that perturb cellular energy levels, the redox state and Ca2+ concentrations. Those stresses reduce the protein folding capacity of the ER, which results in the accumulation and aggregation of unfolded proteins [1]. Involvement of p38 MAPK in ER-stress induced apoptosis has been reported in previous studies using cardiomyocytes [19] and insulin-secreting beta cells [20]. The current study shows that in non-apoptotic chondrocyte cells p38 MAPK also mediate surviving gene regulation. Some stress responses require p38 MAPK but not ERK1/2 [20] and others both p38 MAPK and ERK1/2 [21]. Although we have focused on p38 MAPK in the present study, the observed differential degree of suppression by the p38 MAPK inhibitor in the treatments with thapsigargin and tunicamycin may indicate involvement of other MAPKs such as ERK1/2 and JNK, particularly in thapsigargin-induced upregulation of MMP13 mRNA. Since MMP13 transcription is known to be activated by transcription factors such as AP-1 binding proteins and NF-κB through MAPK pathways [22], it is conceivable that those transcription factors are also involved in the observed upregulation of MMP13 in response to the surviving ER stress.

Transgenic studies using type IX and type XI collagen-deficient mice show overexpression of MMP13 in osteoarthritic temporomandibular joint cartilages [23, 24]. Pathogenesis of osteoarthritis-like changes is reported in mice deficient in type IX collagen with upregulation of MMP13 [25], and mice with the mutations in type X collagen present a phenotype of chondrodysplasia with surviving ER stress [26]. Furthermore, hypoxia and catabolic stress, which are known to induce ER stress, are reported to present osteoarthritic chondrocytes [27, 28]. ER stress in general activates phosphorylation of PKR-like ER kinase (PERK), but PERK mutants are shown to exhibit disordered proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes [29, 30]. Further studies are needed to identify any acute or chronic in vivo ER stress inducers in chondrocytes and evaluate the role of MAPKs in MMP13 regulation.

In summary, we have shown that surviving ER stress to chondrocytes upregulates transcription of MMP13, and p38 MAPK is involved in its regulation. Expression of MMP13 through p38 MAPK is critical in the responses to inflammatory cytokines in osteoarthritis including temporomandibular joint disorders, and the current study indicates ER stress induced activation of p38 MAPK independent from inflammatory cytokines.

Acknowledgments

This study was in part supported by NIH grant R01-AR50008 (HY). Dr. Goldring’s research is supported by NIH grant R01-AG-020221.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Szegezdi E, Logue SE, Gorman AM, Samali A. Mediators of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. EMBO reports. 2006;7:880–885. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldring MB, Tsuchimochi K, Ijiri K. The control of chondrogenesis. J Cell Biochem. 2006;97:33–44. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang L, Carlson SG, McBurney D, Horton WE., Jr Multiple signals induced endoplasmic reticulum stress in both primary and immortalized chondrocytes resulting in loss of differentiation, impaired cell growth, and apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31156–31165. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501069200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ozcan U, Yilmaz E, Ozcan L, Furuhashi M, Vaillancourt E, Smith RO, Gorgun CZ, Hotamisligil GS. Chemical chaperones reduce ER stress and restore glucose homeostasis in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Science. 2006;313:1137–1140. doi: 10.1126/science.1128294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burrage PS, Mix KS, Brinckerhoff CE. Matrix metalloproteinases: role in arthritis. Front Biosci. 2006;11:529–543. doi: 10.2741/1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ijiri K, Zerbini LF, Peng H, Correa RG, Lu B, Walsh N, Zhao Y, Taniguchi N, Huang XL, Otu H, Wang H, Wang JF, Komiya S, Ducy P, Rahman MU, Flavell RA, Gravallese EM, Oettgen P, Libermann TA, Goldring MB. A novel role for GADD45β as a mediator of MMP-13 gene expression during chondrocyte terminal differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:38544–38555. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504202200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finger F, Schorle C, Zien A, Gobhard P, Goldring MB. T Aigner, Molecular phenotyping of human chondrocyte cell lines T/C-28a2, T/C-28a4, and C-28/I2. Arthritis Rheumatism. 2003;48:3395–3403. doi: 10.1002/art.11341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wek RC, Jiagn H-Y, Anthony TG. Coping with stress:eIF2 kinases and translational control. Biochem Soc Transactions. 2006;34:7–11. doi: 10.1042/BST20060007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yokota H, Goldring MB, Sun HB. CITED2-mediated regulation of MMP-1 and MMP-13 in human chondrocytes under flow shear. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:47275–47280. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304652200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radons J, Bosserhoff AK, Grassel S, Falk W, Schubert TE. p38MAPK mediates IL-1-induced down-regulation of aggrecan gene expression in human chondrocytes. Int J Mol Med. 2006;17:661–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamamura K, Yokota H. Stress to endoplasmic reticulum of mouse osteoblasts induces apoptosis and transcriptional activation for bone remodeling. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:1769–1774. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oliver BL, Cronin CG, Zhang-Benoit Y, Goldring MB, Tanzer ML. Divergent stress responses to IL-1β, nitoric oxide, and tunicamycin by chondrocytes. J Cell Physiol. 2005;204:45–50. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang SH, Zhang W, McGrath BC, Zhang P, Cavener DR. PERK (eIF2α kinase) is required to activate the stress-activated MAPKs and induce the expression of immediate-early genes upon disruption of ER calcium homeostasis. Biochem J. 2006;393:201–209. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aixinjueluo W, Furukawa K, Zhang Q, Hamamura K, Tokuda N, Yoshida S, Ueda R, Furukawa K. Mechanisms for the apoptosis of small cell lung cancer cells induced by anti-GD2 monoclonal antibodies. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:29828–29836. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414041200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mengshol JA, Vincenti MP, Coon CI, Barchowsky A, Brinckerhoff CE. Interleukin-1 induction of collagenase 3 (matrix metalloproteinase 13) gene expression in chondrocytes requires p38, c-Jun N-terminal kinase, and nuclear factor kB. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2000;43:801–811. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200004)43:4<801::AID-ANR10>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shlopov BV, Gumanovskaya ML, Hasty KA. Autocrine regulation of collagenase 3 (matix metalloproteinase 13) during osteoarthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2000;43:195–205. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200001)43:1<195::AID-ANR24>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tetlow LC, Adlam DJ, Woolley DE. Matrix metalloproteinase and proinflammatory cytokine production by chondrocytes of human osteoarthritic cartilage. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2001;44:585–594. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200103)44:3<585::AID-ANR107>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reboul P, Pelletier JP, Tardif G, Cloutier JM, Martel-Pelletier J. The new collagenase, collagenase-3, is expressed and synthesized by human chondrocytes but not by synoviocytes. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2011–2019. doi: 10.1172/JCI118636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eiras S, Pernandez P, Pineiro R, Iglesias MJ, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR, Lago F. Doxazosin induces activataion of GADD153 and cleavage of focal adhesion kinases in cardiomyocytes en route to apoptosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;71:118–128. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang G, Yang W, Wu L, Wang R. H2S, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and apoptosis of insulin-secreting beta cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:16567–16576. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700605200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen DT, Kebache S, Fazel A, Wong HN, Jenna S, Emadali A, Lee E, Bergeron JJM, Kaufman RJ, Larose L, Chevet E. Nck-dependent activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase-1 and regulation of cell survival during endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:4248–4260. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-11-0851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liacini A, Sylvester J, Li WQ, Huang W, Dehnade F, Ahmad M, Zafarullah M. Induction of matrix metalloproteinase-13 gene expression by TNF-α is mediated MAP kinases, AP-1, and NF-κB transcription factors in articular chondrocytes. Exp Cell Res. 2003;288:208–217. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu L, Flahiff CM, Waldman BA, Wu D, Olsen BR, Setton LA, Li Y. Osteoarthritis-like changes and decreased mechanical function of articular cartilage in the joints of mice with the chondrodysplasia gene (cho) Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2003;48:2509–2518. doi: 10.1002/art.11233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lam NP, Li Y, Waldman AB, Brussiau J, Lee PL, Olsen BR, Xu L. Age-dependent increase of discoidin domain receptor 2 and matrix metalloproteinase 13 expression in temporomandibular joint cartilage of type IX and type XI collagen-deficient mice. Arch Oral Biol. 2007;52:579–584. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu K, Xu L, Cao L, Flahiff CM, Brussiau J, Ho K, Setton LA, Youn I, Guilak F, Olsen BR, Li Y. Pathogenesis of osteoarthritis-like changes in the joints of mice deficient in type IX collagen. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2891–2900. doi: 10.1002/art.22040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsang KY, Chan D, Cheslett D, Chan WCW, So CL, Melhado IG, Chan TWY, Kwan KM, Hunziker EB, Yamada Y, Bateman JF, Cheung KMC, Cheah KSE. Surviving endoplasmic reticulum stress is coupled to altered chondrocyte differentiation and function. PLOS Biol. 2007;5:e44. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coimbra IB, Jimenez SA, Hawkins DF, Piera-Velazquez S, Stokes DG. Hypoxia inducible factor-1 alpha expression in human normal and osteoarthritic chondrocytes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12:336–345. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yudoh K, Nakamura H, Masuko-Hongo K, Kato T, Nishioka K. Catabolic stress induces expression of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1 alpha in articular chondrocytes: involvement of HIF-1 alpha in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R904–914. doi: 10.1186/ar1765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y, Iida K, O’Neil J, Zhang P, Li S, Frank A, Gabai A, Zambito F, Liang S, Rosen CJ, Cavener DR. PERK eIF2α kinase regulates neonatal growth by controllingthe expression of circulating insulin-like growth factor-I derived from the liver. Endocrinology. 2003;144:3505–3513. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jager M, Thorey F, Westhoff B, Wild A, Krauspe R. In vitro osteogenic differentiation is affected in Wiedemann-Rautenstrauch-Syndrome (WRS) In Vivo. 2005;19:831–836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]