Abstract

Ethnic groups differ in rates of suicidal behaviors among youths, the context within which suicidal behavior occurs (e.g., different precipitants, vulnerability and protective factors, and reactions to suicidal behaviors), and patterns of help-seeking. In this article, the authors discuss the cultural context of suicidal behavior among African American, American Indian and Alaska Native, Asian American and Pacific Islander, and Latino adolescents, and the implications of these contexts for suicide prevention and treatment. Several cross-cutting issues are discussed, including acculturative stress and protective factors within cultures; the roles of religion and spirituality and the family in culturally sensitive interventions; different manifestations and interpretations of distress in different cultures; and the impact of stigma and cultural distrust on help-seeking. The needs for culturally sensitive and community-based interventions are discussed, along with future opportunities for research in intervention development and evaluation.

Keywords: culture, suicide prevention, treatment, help-seeking, adolescents

Suicide is the third leading cause of death among adolescents, accounting for a greater number of deaths than the next seven leading causes of death combined for 15- to 24-year-olds (aCenters for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2006a). Almost 1 in 12 adolescents in high school made a suicide attempt, and 17% of adolescents seriously considered making a suicide attempt, in the calendar year 2005 (CDC, 2006b). Nonetheless, there are differences among ethnic groups in the rates and contexts within which adolescent suicidal behaviors occur. The purpose of this article is to examine these ethnic differences and to explore the implications of culture for the development of suicide prevention and treatment interventions.

Definitions of Terms

Terms such as culture, ethnicity, and race, and terms describing suicidal behaviors have been used in different ways in the literature. For the purposes of this article, culture is defined as the shared learned behavior and “belief systems and value orientations that influence customs, norms, practices, and social institutions” of a group of people (American Psychological Association [APA], 2003, p. 380). Culture is reflected in the artifacts, roles, language, consciousness, and attitudes of a people (APA, 2003; Marsella & Yamada, 2000). Race describes the physical characteristics of a person: his or her skin color, facial features, hair texture, eye color, and shape. The biological bases of race have been debated (APA, 2003), and multiple difficulties have been noted with the use of race as a basis of classification (Helms, Jernigan, & Mascher, 2005; Smedley & Smedley, 2005). Nonetheless, race is a social construction wherein individuals labeled as being of different races on the basis of physical characteristics are often treated as though they belong to biologically defined groups (APA, 2003). The term ethnicity or ethnic group is used to refer to “clusters of people who have common culture traits that they distinguish from those of other people”; the traits may derive from factors such as use of a common language, place of origin, sense of history, values, and traditions (Smedley & Smedley, 2005, p. 17). For example, Latinos may share cultural expectations about gender and family roles that derive in part from country of origin and historical traditions. As defined here, ethnic group differences can be considered to be a subset of cultural differences. There is a great deal of heterogeneity within ethnic groups, and differences due to ethnicity and culture may not be static insofar as culture is learned and may change over time (Smedley & Smedley, 2005). In addition, in our multiethnic society, it is common for families to comprise individuals from multiple ethnic backgrounds or heritage (APA, 2003).

Suicidal behavior is a generic term in this article referring to thoughts of suicide, suicide attempts, and deaths by suicide. Suicide refers to a self-inflicted death associated with some (intrinsic or extrinsic) evidence of intent to kill oneself (O’Carroll et al., 1996). Suicide attempts likewise refer to potentially self-injurious but non-lethal behavior associated with any intent to kill oneself (O’Carroll et al., 1996). Suicide ideation refers to thoughts of killing oneself (regardless of intent).

Racial and Ethnic Differences in Rates of Suicidal Behaviors

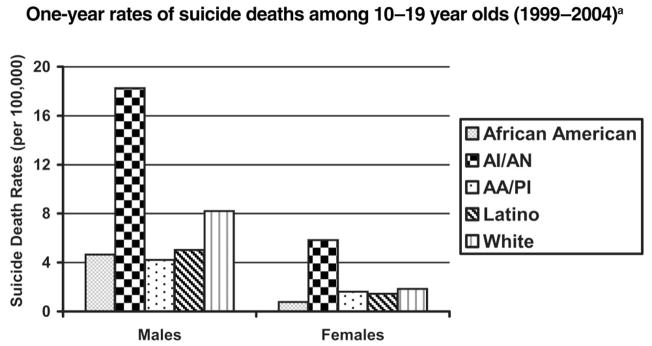

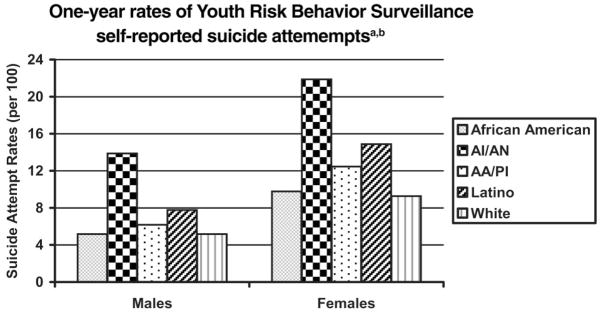

Evidence of racial and ethnic differences is readily apparent in the rates of lethal and nonlethal suicidal behaviors among different groups of adolescents. For example, as can be seen in Figure 1, the rate of suicide deaths among adolescents differs by a factor of 20 between the highest risk group (American Indian/Alaska Native males) and the lowest risk group (African American females). As can be seen in Figure 2, there is also a great deal of variability in rates of nonlethal suicide attempts. Specifically, suicide attempts are highest among American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) females, followed by Latinas, AI/AN males, and Asian American/Pacific Islander (AA/PI) females; suicide attempts are lowest among African American and White adolescent males. Hand in hand with these differences in rates are differences in the precipitants associated with suicidal behavior, differences in risk and protective factors, and differences among groups in how they react to suicidal behavior and in how this reaction translates into help-seeking behaviors.

Figure 1. Suicide Deaths Among Youths as a Function of Gender and Ethnicity.

Note. AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native; AA/PI = Asian American/ Pacific Islander. a Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2006a).

Figure 2. Suicide Attempts Among Youths as a Function of Gender and Ethnicity.

Note. AI/AN = American Indian/Alaska Native; AA/PI = Asian American/ Pacific Islander. a Sources: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2006b), Crosby (2004), Grunbaum, Lowry, Kann, and Bateman (2000). b The most recent data available for White, African American, and Latino adolescents are from the 2005 administration of the Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Data for AI/AN adolescents are available from youths attending Bureau of Indian Affairs schools in 2003. Data from AA/PI adolescents are reported for the years 1991 through 1997 (because of the relatively smaller number of youths in this category; Grunbaum, Lowry, Kann, & Bateman, 2000).

Historical Consideration of Culture and Suicidal Behaviors

Historically, rates of suicidal behaviors, and beliefs and attitudes toward suicidal behaviors, have varied widely across cultures (Alvarez, 1971; Minois, 1995/1999). Academic interest in the cultural and social influences on suicidal behavior dates back at least to Durkheim’s (1897/ 1951) investigations of the associations between suicide rates, religion, and social integration. Nonetheless, despite the long-standing interest in culture and suicidal behaviors, there are few reports of effective culturally tailored or culturally sensitive interventions for suicidal adolescents. A report by the Institute of Medicine referred to the need for an appreciation of the cultural context of suicidal behavior and for culturally appropriate interventions for suicidal behaviors (Goldsmith, Pellmar, Kleinman, & Bunney, 2002). Greater understanding of the cultural context of mental health problems such as suicidal behavior may help psychologists to improve access to and remove barriers to treatment, address needs for culturally competent therapists, and improve quality of care for vulnerable populations (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001).

Purpose of this Article

In the first part of this article, we present frameworks for considering the cultural context of suicidal behavior and help-seeking. Next, in separate sections for each racial and ethnic group (African American, AI/AN, AA/PI, and Latino adolescents),1 we review research regarding aspects of culture potentially related to adolescent suicidal behavior and help-seeking. In describing cultural factors, we have tried to avoid the common practice of referring to Whites as the normative reference group because this practice may automatically confer privilege and dominance to Whites and implicitly render communities of color as either deviant or invisible (Sue, 2006). In the separate sections, we also review what is known about culturally sensitive prevention and treatment interventions, referencing research in other areas when the literature for suicide intervention efforts is sparse. In the concluding discussion, we discuss cross-cutting issues such as the roles of family and religiosity, the need for culturally competent mental health resources, the implications of cultural context for future research and the development of interventions, and the role of psychologists in addressing these needs. The “Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct” (APA, 2002) and the “Guidelines on Multicultural Education, Training, Research, Practice, and Organizational Change for Psychologists” (Multicultural Guidelines; APA, 2003) emphasize the importance of understanding facets of culture that affect services and research.

The Cultural Context of Adolescent Suicidal Behavior and Help-Seeking

Several aspects of cultural influences on suicidal behavior and risk are considered in this article. First, there may be culture-specific patterns in the triggers or precipitants of suicidal behavior. For example, some individuals of Eastern Asian descent may engage in suicidal behavior after they experience the shame associated with loss of face because they failed to meet expectations of their families or others (Zane & Mak, 2003). Second, risk and protective factors for suicidal behavior may be influenced by cultural context. For example, acculturative stress among Latino adolescents is associated with higher levels of thoughts about suicide (Hovey & King, 1996). Third, the characteristics of suicidal and related behaviors may differ across cultures, although this possibility has been understudied. Finally, individuals in various cultural contexts may view and understand, and hence react to, suicidal behaviors in different ways. For example, suicidal thoughts or behavior may not be recognized as a problem as readily among African Americans because of a perception among Blacks that they are not at risk for suicidality (Morrison & Downey, 2000).

Culture additionally may affect each of the stages of help-seeking behaviors (Cauce et al., 2002) that lead to utilization of mental health services for prevention or treatment of suicidal behaviors. In the first stage of help-seeking, behaviors or difficulties need to be recognized as a problem. As mentioned above, behaviors such as suicide attempts may be perceived, labeled, or tolerated differently in different cultural groups (Cauce et al., 2002). Even if a behavior is recognized as problematic, cultural factors may affect decisions about whether to seek mental health assistance. For example, some cultural groups may not seek formal services because of stigma or concerns that mental health services will be contrary to cultural values. In this regard, Freedenthal and Stiffman (2007) found that among young American Indian adolescents, stigma and embarrassment were associated with not seeking help when suicidal. Finally, culture may influence the decision about the type of services or help to seek (Cauce et al., 2002). For example, recently immigrated Latino and Asian families may lack familiarity with the health care system or may believe that problems such as suicidal behaviors should be dealt with by the family or faith community rather than specialty mental health services.

In sum, suicidal behavior and help-seeking occur in a cultural context and are likely associated with different precipitating factors, different vulnerability and protective factors, differing reactions to and interpretations of the behavior, and different resources and options for help-seeking. Awareness of the interface of culture, adolescent suicidal behavior, and help-seeking is essential for culturally competent professionals and an important step en route to the development of effective culturally sensitive interventions to reduce suicidal behaviors.

Suicidality Among African American Youths

Although the overall suicide rate among African Americans aged 10 –19 years declined from 4.5 to 3.0 per 100,000 in the United States from 1995 to 2004, suicide remains the third leading cause of death for African American 15- to 19-year-olds (CDC, 2006a). From 1981 to 1995, the suicide rates increased 133% for 10- to 19-year-old African American youths; this increase was primarily evident among males (a 160% increase, as compared with a 46% increase among females; CDC, 2006a). The increased rate over time of suicide deaths among young African American males was largely accounted for by an increase in rates of suicide deaths via firearms (Joe & Kaplan, 2002). Across the life span, the median age of suicide is approximately a decade earlier for Black suicide victims than for other suicide victims (Garlow, Purselle, & Heninger, 2005). Moreover, the rate of suicide attempts for African American adolescent males more than doubled from 1991 to 2001 (Joe & Marcus, 2003).

There is much heterogeneity in the Black population that may affect risk for suicidal behaviors, including rural versus urban differences, regional differences, and differences between recent immigrants and individuals whose ancestors were brought to this country from Africa as slaves. Little has been written about cultural differences among Black youths and how they might be related to differential risk for suicidal behavior. However, in the National Survey of American Life, Joe, Baser, Breeden, Neighbors, and Jackson (2006) found that Black men of Caribbean descent in this country had higher rates of suicide attempts than African American men and that Black adults in the southern United States had lower rates of suicide attempts than Black adults in other regions.

Cultural Context of Suicidal Behaviors in African American Youths

Two widely prevalent stressors that have been linked to a number of physiological and psychological problems for African Americans are racism and discrimination (Clark, Anderson, Clark, & Williams, 1999). Clark and colleagues (1999) defined racism as “beliefs, attitudes, institutional arrangements, and acts that tend to denigrate individuals or groups because of phenotypic characteristics or ethnic group affiliation” (p. 805). Although not unique to African Americans, perceived racism and discrimination have been found to be associated with depression, increased substance use, and hopelessness among African American youths (Gibbons, Gerard, Cleveland, Wills, & Brody, 2004; Nyborg & Curry, 2003). These factors, in turn, are associated with adolescent suicidal behaviors (Goldston, 2004; Goldston et al., 1999, 2001).

Using city-level analyses, Kubrin, Wadsworth, and DiPietro (2006) demonstrated that deindustrialization in urban areas (inner cities) has been related to increased rates of suicide among 15- to 34-year-old African American males. Deindustrialization in the inner cities is related to a number of economic and social disadvantages, including greater concentrations of poverty; fewer opportunities for education, employment, and social mobility; a sense of hopelessness and alienation; greater violence; and fewer family and community social supports that might protect against suicidality (Kubrin et al., 2006). Greenberg and Schneider (1994) similarly argued that suicide and homicide rates are the highest for the urban poor because they live in impoverished areas with fewer resources and greater exposure to violence and toxic waste. Many African Americans attribute poor environmental conditions and limited opportunities to ethnic discrimination (Sigelman & Welch, 1991).

Greater awareness of social and economic inequities in the aftermath of the civil rights movement may have increased the vulnerabilities of young African Americans (Burr, Hartman, & Matteson, 1999). For example, Joe (2006) has speculated that many young African Americans subscribe to the ideal in America that opportunities should be limited only by a person’s skills and motivation. However, upon experiencing barriers to success such as discrimination and institutional racism, they become frustrated, distressed, and at greater risk for suicide. Moreover, some have suggested that middle-income African Americans may also be at risk for suicide because they experience anxiety, stress, or anger due to conflicts over pressures to adopt the values of White individuals while simultaneously trying to hold on to their cultural identity and cultural experiences (Willis, Coombs, Cockerham, & Frison, 2002).

Religiosity often has been assumed to mitigate risk for suicidality, and it has been found in surveys that African American youths tend to report more religious activities than other ethnic groups (Gallup & Bezilla, 1992). However, the orientation toward religion or the manner in which religion is used as a coping mechanism may influence its effects. For example, among African American students, self-directed religious coping (a belief that God gives individuals the freedom to resolve their own problems) has been noted to be related to more hopelessness, depression, and suicide attempts (Molock, Puri, Matlin, & Barksdale, 2006). In contrast, a collaborative religious coping style (a belief that the individual is in an active, cooperative relationship with God in solving problems) has been found to be associated with increased reasons for living (Molock et al., 2006).

Gibbs (1997) described the importance of social support, cultural cohesion, and the role of extended family as factors that mitigate the risk of suicidal behaviors among African Americans. It has been hypothesized that African American females’ greater access to familial and community protective mechanisms accounts in part for their lower rates of death by suicide (Nisbet, 1996). This underscores the ethos of communalism among some African Americans that emphasizes the extended self, social bonds, and the fundamental interdependence of people (Jones, 1991). However, on the basis of survey findings with young adult college students, Harris and Molock (2000) found that collectivist values may not always be protective and in fact may be related to higher rates of suicidal thoughts and depressive symptoms. It was suggested that individuals who are higher in a collectivist orientation may be more sensitized to the presence of racial oppression and discrimination that occurs in the college community and the community at large.

There may also be a tendency for African American youths to evidence suicidal behaviors and risk differently than other youths. For example, African American students report lower rates of serious consideration of suicide and suicide plans than White and Latino students (CDC, 2006b). African American college students are also less likely to express hopelessness (Molock, Kimbrough, Lacy, McClure, & Williams, 1994), even though hopelessness has been found to be especially associated with suicide attempts among adolescent and young adult African Americans (Durant et al., 2006).

In this regard, several researchers have also noted the importance of being cool (exhibiting poise under pressure) for some African American male youths; appearing cool and aggressive may protect males from becoming victims of violence in the short run (Stevenson, Herrero-Taylor, Cameron, & Davis, 2002) but may make it difficult for them to get help for mental health concerns. Because of stigma and the importance of not appearing vulnerable, it may be that some youths who are depressed try to find more culturally acceptable ways of ending their lives. For example, Wolfgang (1959) described cases of victim-precipitated suicide, disproportionately represented among African American males, in which individuals apparently tried to provoke others into killing them as an indirect method of suicide. In studies of officer-involved shootings, there appears to be evidence of possible suicidal intent (e.g., statements about wanting to die) in between 10% and 46% of cases, depending on the study and methodologies used (Klinger, 2001). Such instances may occur when individuals wish to end their lives but cannot bring themselves to do so because of cultural or religious values.

Cultural Context of Help-Seeking Among African American Youths

African American youths are underrepresented in outpatient mental health services (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001). These lower rates of help-seeking may be due to a number of factors. For example, distrust of professional mental health care has been noted among African Americans because of historical and personal abuses dating back to the time of slavery and a lack of cultural sensitivity by care providers (Nickerson, Helms, & Terrell, 1994). In particular, the Tuskegee experiment has fostered distrust of the health system and reduced use of mental health services (Breland-Noble, 2004). Factors such as lack of adequate health insurance, culturally insensitive views of African Americans by mental health service providers, and the use of culturally inappropriate screening measures, diagnostic procedures, and treatment approaches may also serve as institutional barriers to care (e.g., U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001).

It has been hypothesized that John Henryism may also serve as a barrier to mental health service access (Breland-Noble, 2004). John Henryism is the ethic that personal difficulties and stresses should be overcome through hard work, determination to succeed, and perseverance (Bennett et al., 2004; Breland-Noble, 2004). As a coping style, however, it is associated with poor health outcomes (Bennett et al., 2004). John Henryism may be related to the fact that many African American adolescents view the expression of certain aspects of depressive affect (e.g., feelings of hopelessness) as culturally incongruent (Molock et al., 2007).

Informal sources of help are often preferred among African Americans, although they utilize and even report satisfaction with professional mental health services (Taylor, Neighbors, & Broman, 1989). African American adults are more likely to seek help from clergy for mental health concerns, report greater satisfaction with the services provided by clergy, and are less likely to seek help from mental health professionals once they have seen clergy (Neighbors, Musick, & Williams, 1998).

Suicide Prevention and Treatment for African American Youths

To date, there appear to be no published studies of effective suicide prevention programs or treatments specifically tailored for African American youths. Prevention programs developed for African American youths for reducing other public health problems (pregnancy, relational aggression, and violence; e.g., Belgrave et al., 2004; Dixon, Schoonmaker, & Philliber, 2000; Ngwe, Liu, Flay, Segawa, & Aban Aya Co-investigators, 2004) have included a focus on increasing ethnic identity through rites of passage programs while simultaneously teaching African American youths new problem-solving skills.

Molock (2005) has suggested that the Black Church should be considered when developing suicide interventions because of the importance of religion and spirituality in African American culture. Although there are many different faith traditions within the African American community, a common religious/cultural ethos underlies many African American Christian churches, collectively referred to as the Black Church (Lincoln & Mamiya, 1990). The Black Church refers to those independent, historic, and totally African American controlled denominations that constitute the core religious experience of the great majority of African American Christians. The Black Church, although sharing much in common with Christian churches in other racial/ethnic communities, also has a distinct culture that is influenced by its African heritage and by traditions that evolved from slavery, and it has consistent differences in the emphases and valences given to particular theological perspectives (e.g., an emphasis on freedom), styles of worship, and the centrality placed on the preached word in the worship experience (Lincoln & Mamiya, 1990). Although there has been some decline in its influence, the Black Church continues to have an influence on the African American community by providing social support and promoting self-reliance and political activism. In a series of qualitative studies, Molock and her colleagues found that African American church members and clergy were interested in developing mental health interventions in churches that would strengthen families and youths and were more likely to view suicide as aberrant to African American cultural values rather than as anathema to religious beliefs (Molock, 2005).

Nonetheless, potential barriers to consider within the Black Church include the fact that clergy are less likely to recognize suicidal lethality (Domino & Swain, 1985–1986) than other health professionals and make few referrals to mental health professionals (Blank, Mahmood, Fox, & Guterbock, 2002) and the fact that some Christian churches may have negative attitudes toward mental health treatment and suicide (Blank et al., 2002). It is possible that some of these barriers can be overcome through gatekeeper training programs for clergy and laypeople (i.e., training for individuals who have contact with youths so they are better able to recognize risk and make appropriate referrals). African American youths were open to programs that provided young adult gatekeepers (under the age of 35) who regularly worked with youths in ongoing ministries in the church (Molock et al., 2007). African American clergy were also interested in using gatekeeper models that would assist the churches in providing important linkages for its members to mental health providers who were both culturally and religiously sensitive to the needs of church members (Molock, 2005).

Suicidality Among American Indian and Alaska Native Youths

Suicide accounts for nearly one in five deaths among AI/AN 15- to 19-year-olds, a considerably higher proportion of deaths than for other ethnic groups (CDC, 2006a). Differences in suicide rates between AI/AN youths and other ethnic youths have been noted for over three decades (e.g., May & Dizmang, 1974). As a consequence, by the 1970s, there were cautions to researchers and practitioners to avoid stereotypes of the “suicidal Indian.” Gender differences in suicide deaths among AI/AN youths are somewhat attenuated relative to other ethnic groups because of the relatively higher rate of suicide among AI/AN females in recent years, a rate that is three times that of 15- to 19-year-old females in the general population (CDC, 2006a).

Cultural Context of Suicidal Behaviors in American Indian and Alaska Native Youths

AI/AN adolescents experience many of the same risk factors as other youths. Although two thirds of American Indian children live in urban areas (Snipp, 2005), research over the last three decades has focused almost entirely on those who live on reservations. Life on rural, sometimes isolated reservations appears to amplify risks (Freedenthal & Stiffman, 2004). For example, geographically isolated reservations may increase the likelihood of economic deprivation, lack of education, and limited employment opportunities, thereby contributing to a sense of hopelessness among young people.

Among the risk factors, American Indian populations have elevated rates of alcohol abuse and dependence disorder (Beals et al., 2005), and earlier and higher rates of alcohol and drug use among youths, relative to most other ethnic groups, although this varies by culture and within culture. For example, according to data collected as part of the Monitoring the Future national survey from 1976 to 2000, almost a quarter of American Indian eighth graders reported drinking five or more drinks at a single sitting within the past two weeks (Wallace et al., 2003). This rate of heavy drinking in eighth grade is higher than that reported for other ethnic groups, with the exception of Mexican American youths, who have a comparable rate. More severe or progressed alcohol and substance use, in turn, is more strongly associated with increased risk of suicidality (Goldston, 2004). High rates of adult alcohol use in some communities may also weaken support systems for at-risk youths.

There has been considerable concern about suicide clustering among adolescents (Gould, Wallenstein, Kleinman, O’Carroll, & Mercy, 1990). Although more research needs to be done, there is grassroots anxiety about cluster suicides on U.S. reservations and Canadian reserves (e.g., Chekki, 2004) and growing evidence that AI/AN youths may be at particular risk for suicide contagion (Bechtold, 1988; Wissow, Walkup, Barlow, Reid, & Kane, 2001), perhaps because of small, intense social networks among adolescents on rural reservations. In one example of an identified cluster, seven cases of American Indians ages 13 to 28 on a single reservation killed themselves in a 40-day period via hanging (Wissow et al., 2001). Even beyond the possibility of suicide clusters, because of the high rates of suicide deaths on some reservations, it is likely that AI/AN youths have had greater exposure to suicide and suicidal behavior among family members than have many other youths, leading to trauma and disruption or loss of support systems (Bender, 2006).

The military campaigns against and the forced relocation of American Indians have been well documented. In addition, during the late 1800s and throughout the first half of this century, AI/AN children were removed from their families and raised in boarding schools where traditional language use and cultural ways were forbidden. For those living on the reservations, the practice of traditional religions was illegal, and often there were few or no means of supporting a family, which created dependence on inadequate food distribution by the government. The sense of intergenerational trauma associated with this ethnic cleansing persists today, with daily reminders including reservation living and losses of traditional ways (Whitbeck, Adams, Hoyt, & Chen, 2004). This intergenerational trauma is associated with demoralization and hopelessness (e.g., Brave Heart, 1998; Whitbeck et al., 2004) and may be associated with increased suicide risk.

The term enculturation refers to the process by which knowledge, behavioral expectations, attitudes, and values are acquired and shared by members of a cultural group (Zimmerman, Ramirez-Valles, Washienko, Walter, & Dyer, 1994). Enculturation represents the degree to which an individual is embedded in his or her cultural traditions, as evidenced by traditional practices, language, spirituality, and cultural identity (Whitbeck et al., 2004). Traditional cultural values and spirituality provide a strong foundation for adolescent prosocial behaviors through close ties to family (including extended family), concern by tribal elders for all of the families and children in the community, and affiliation with prosocial peers. Enculturation has been found to be related to protective factors such as academic success and prosocial behaviors among American Indian adolescents (Whitbeck, Hoyt, Stubben, & LaFromboise, 2001; Zimmerman et al., 1994). Cultural spiritual orientation similarly has been found to be related to a reduced history of suicide attempts among adolescents and adults even after levels of distress and substance abuse have been considered (Garroutte et al., 2003). Although enculturation serves as a protective factor, growing up in two cultures that often have conflicting behavioral demands (LaFromboise & Bigfoot, 1988) and persistent discrimination (Whitbeck et al., 2004) can create cumulative stresses that may enhance vulnerability.

In terms of phenomenology, it is notable that the suicidal behaviors of AI/AN youths occur in the context of high rates of other risk-taking and potentially life-endangering behaviors. For example, the death rates for all unintentional injuries combined among 10- to 19-year-old AI/AN youths are 50% higher than the overall United States rates (CDC, 2006a). It is not clear if this high rate of accidental deaths reflects a lack of regard for the lethal consequences of some behaviors or unrecognized suicidal intent.

Cultural Context of Help-Seeking in American Indian and Alaska Native Youths

American Indian people often have strong beliefs about the healing nature of traditional knowledge and practices even when they seek specialized professional health services. For example, in one epidemiologic study, it was found that between 35% and 40% of American Indian adolescents and adults with a lifetime history of depressive or anxiety disorders sought services from a mental health professional, but between 34% and 49% also sought help from a traditional healer (Beals et al., 2005). Use of traditional healing rituals and services is positively linked to strength of ethnic identity (Novins, Beals, Moore, Spicer, & Manson, 2004).

It is also possible that the stigma associated with psychiatric services is related to increased use of traditional healing for mental health issues (Novins et al., 2004). In one study of American Indian adolescents who reported suicidal thoughts and behavior, reasons for avoiding formal mental health care included embarrassment and stigma, not perceiving a reason for help, feeling hopeless and alone, and a desire to be self-reliant (Freedenthal & Stiffman, 2007). Related to the concerns about stigma is the fact that it may be difficult to confidentially seek or receive services in small isolated communities with limited availability of community mental health resources (De Couteau, Anderson, & Hope, 2006).

Suicide Prevention and Treatment for American Indian and Alaska Native Youths

Because they acknowledge tremendous diversity between the more than 562 federally recognized tribes of the United States and Canada (U.S. Department of the Interior, 2005), suicide prevention programs that are culturally appropriate and incorporate culturally specific knowledge and traditions have been shown to be well received by AI/AN communities and to have promising results. In one review, Middlebrook, LeMaster, Beals, Novins, and Manson (2001) identified nine prevention programs that met Institute of Medicine criteria for evaluating preventive interventions (Mrazek & Haggerty, 1994). Of these, five targeted AI/AN suicide among youths: the Zuni Life-Skills Development Curriculum (LaFromboise & Howard-Pitney, 1994), the Wind River Behavioral Program (Tower, 1989), the Tohono O’odham Psychology Service (Kahn, Lejero, Antone, Francisco, & Manuel, 1988), the Western Athabaskan Natural Helpers Program (May, Serna, Hurt, & DeBruyn, 2005), and the Indian Suicide Prevention Center (Shore, Bopp, Waller, & Dawes, 1972). Four other AI/AN programs included suicide prevention as part of more general adolescent behavioral health programs. These prevention programs incorporate positive messages regarding cultural heritage that increase the self-esteem and sense of mastery among AI/AN adolescents and focus on protective factors in a culturally appropriate context (LaFromboise, 1996). They also teach coping methods such as traditional ways of seeking social support (May et al., 2005).

The results of prevention efforts are promising. For example, the most recent follow-up report from the Western Athabaskan Natural Helpers Program indicated a decrease of 61% in suicide attempts during the 12 years the program has been implemented (May et al., 2005). May and colleagues attributed the success of this program to a comprehensive prevention strategy that addressed multiple levels of behavioral health problems, strong community investment in the program, and ongoing evaluation to maintain program focus.

Although the results from these prevention programs are encouraging, there are major cultural differences between different Native American groups. Among some, there are age-old enmities that work against common prevention programs. Many tribes are struggling to maintain their cultural integrity and resist programs that do not acknowledge unique cultural beliefs and practices. Different native groups also may differ in the degree of cohesion in the community, the degree to which individual achievement is emphasized, attitudes toward substance abuse and antisocial behavior, and even attitudes toward death (e.g., Novins, Beals, Roberts, & Manson, 1999). Because of these differences and efforts to maintain cultural integrity, intervention programs for one Native American group (e.g., the Ojibwe) may therefore not be generalizable to another (e.g., the Dakota/Lakota people). However, in recognition of this problem of lack of generalizability of prevention programs, Mohatt et al. (2004) and Allen et al. (2006) have described efforts with Alaska Native cultures to identify common elements that could be incorporated into generalizable prevention programs to be used in multiple communities. Perhaps this model could be used for American Indian cultures, particularly those with closely related traditions.

Little published research has focused on treatment approaches specifically tailored for suicidal AI/AN youths. However, given preferences for traditional healing practices for psychiatric difficulties among many AI/AN individuals, it is likely that such interventions will be effective to the extent that they recognize and integrate the cultural values of the AI/AN group, respect traditional practices, and reinforce cultural identity. In fact, the more an intervention derives from within the community and uses traditional knowledge, the greater the prospects for its preference and use (Walls, Johnson, Whitbeck, & Hoyt, 2006).

Suicidality Among Asian American and Pacific Islander Youths

AA/PIs are proportionally the fastest-growing ethnic group in the country (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2002), with estimates indicating that the number of AA/PI youths will increase by 74% by 2015 (Snyder & Sickmund, 1999). As can be seen in Figure 1, the rate of suicide among AA/PI males is the lowest for males among the ethnic groups, and the gender differences in rates of suicide for AA/PI adolescents are not as large as those for other ethnic groups (CDC, 2006a). However, AA/PIs are an extremely heterogeneous group with significant intergroup differences in rates of suicide. For example, suicide has been ranked as the leading cause of death among South Asians ages 15–24 in the United States (Hoyert & Kung, 1997). Nonetheless, as described below, suicide and suicidal behavior likely are underrecognized among AA/PI youths owing to a variety of factors.

Cultural Context of Suicidal Behaviors in Asian American and Pacific Islander Youths

When an individual’s behavior upsets group harmony, loss of face (social shame) is experienced (Zane & Mak, 2003). Loss of face is more prominent in East Asians (i.e., Chinese and Japanese) and East Asian Americans, although it may also exist in other Asian groups (e.g., South Asians) to a lesser degree, and it persists despite acculturation. Loss of face can serve as a precipitant for suicidal behavior if the loss of face is perceived as intolerable or if the group views suicide as an honorable way of dealing with difficulties. Alternatively, if the group views suicide as dishonorable, the adolescent may be less likely to attempt suicide, even in the presence of loss of face.

There is a tendency among many AA/PIs to value interdependence, that is, a collectivist orientation, over independence (Oyserman, Coon, & Kemmelmeier, 2002). Whereas independence promotes individuality and competitiveness and places a high value on personal standards, among individuals of Asian descent, a collectivist orientation may be associated with conformity, clearly defined roles, and the importance of group harmony. This association may result in the use of indirect communication, suppression of conflict, and the withholding of free expression of feelings (Uba, 1994). Indeed, AA/PI adolescents report greater difficulty discussing problems with their family members and are often less emotionally expressive than their non-Asian peers (Rhee, Chang, & Rhee, 2003). Together with fear of loss of face, this emphasis on interdependence may contribute to the concealment of emotional disturbance in AA/PI adolescents and to a possible lack of awareness by others of suicide risk.

AA/PI adolescents may experience distress and conflict with family members and peers when there are conflicts between the demands of role fulfillment and interdependence and the demands for establishment of an independent identity, as valued in Western society. In a study by Lorenzo, Frost, and Reinherz (2000), for example, older Asian American adolescents reported more social problems than their peers, including peer rejection, teasing, and being too dependent on others. Such strains may increase vulnerability to depression and suicidality.

The problems of AA/PI adolescents sometimes are overlooked because of the stereotyping of Asian Americans as a population with high achievement orientation, academic and financial success, and low rates of risk behavior and psychopathology. This stereotype of being a model minority, however, has been called into question with the recognition of the diversity of the population (Sue, Sue, Sue, & Takeuchi, 1995) and the observation that high-achieving Asian American adolescents without externalizing difficulties exhibit higher rates of depressive symptoms than their peers (Lorenzo et al., 2000).

The level of acculturation and recency of immigration may influence suicidal behavior in AA/PI adolescents. The immigration process itself may present significant stresses for some AA/PI individuals, particularly refugees who have endured trauma, violence, and life-threatening conditions and journeys (Hinton & Otto, 2006). Most of the research documenting stresses among Asian refugees has focused on adults, but Hyman, Vu, and Beiser (2000) noted multiple acculturative stresses experienced by children of Southeast Asian refugees, including feelings of estrangement and academic frustrations related to lack of English fluency, unequal language fluency between parents and youths, cultural differences in academic environments, and high parental expectations.

In one study of AA/PI outpatients (Lau, Zane, & Myers, 2002), suicidal youths were more likely than non-suicidal youths to have been born outside of the United States. Those who had emigrated to the United States and were suicidal were older than the children in the nonsuicidal group at the time of migration. Lau and colleagues (2002) speculated that less acculturated youths may be more collectivist and experience greater distress when faced with family conflict and threats to group harmony and may have less nonfamilial support than more acculturated groups. In addition, the discrepancies between parents and children in cultural orientation may be important for mental health outcomes. Costigan and Dokis (2006), for example, found that adolescents who had a lower orientation toward Chinese culture but had parents with a strong Chinese cultural orientation tended to have more severe depression.

To our knowledge, there is no empirical research on protective factors against suicide among AA/PI youths. However, English language proficiency, a present rather than past time orientation, and social support from families and ethnic communities protect against depression among Southeast Asians (Hsu, Davies, & Hansen, 2004), and ethnic identity pride has been found to buffer somewhat against the effects of perceived discrimination on depression among Korean American college students (Lee, 2005). On the other hand, there has also been research suggesting that a stronger level of enculturation, or identification with a person’s culture of origin, is associated with increased suicidal thoughts, but not suicide attempts, among college students (Kennedy, Parhar, Samra, & Gorzalka, 2005).

Cultural Context of Help-Seeking in Asian American and Pacific Islander Youths

Underrecognition of suicidal risk in Asian Americans warrants further investigation, particularly because research has shown that Asian Americans underutilize outpatient mental health services (Bui & Takeuchi, 1992). In a 1998 study by Zhang, Snowden, and Sue, only 4% of Asian Americans reported that they would seek help from a psychiatrist or mental health specialist. Moreover, only 12% of Asian Americans reported that they would seek the support of friends or family for mental health problems. Findings from the Chinese American Psychiatric Epidemiologic Study (CAPES) revealed similarly low rates of use of mental health services and indicated that only 4% of Chinese Americans with mental health problems consulted with their physician, and only 8% consulted with a minister or priest (Young, 1998).

Even when Asian American adolescents seek mental health treatment, they may not disclose suicidal ideation as readily as their non-ethnic-minority peers (Morrison & Downey, 2000). Part of the reason why Asian Americans may be “hidden ideators” is their tendency to focus on their somatic rather than psychological symptoms of distress (Tseng et al., 1990). The combination of Asian cultures’ belief in the unity of the mind and body with the Asian tendency not to express feelings openly may lead to the presentation of somatic complaints and the underreporting of psychological symptoms (Lin & Cheung, 1999). Indeed, AA/PIs entering mental health treatment often exhibit severe psychopathology (Durvasula & Sue, 1996), a finding attributed to the long treatment delay in this population compared with that in other ethnic groups (Lin, Inui, Kleinman, & Womack, 1982).

Religion may influence help-seeking and suicidality among Asian Americans. A significant proportion of Buddhists (61%) and Muslims (34%) in the United States are of Asian descent, although the largest percentage (21%) of Asian Americans are Catholics (Kosmin, Mayer, & Keysar, 2001). Within the Asian American community, religious differences may account for different rates of help-seeking and suicidal behavior. South Asians, for example, are more likely to commit suicide if they identify with Hinduism as opposed to Islam (Ineichen, 1998). The Hindu religion takes a more accepting stance toward suicide than does Islam and may decrease help-seeking if suffering is seen as part of one’s karma, deserved, and unpreventable (Conrad & Pacquiao, 2005). Buddhism also subscribes to fatalism, the acceptance of one’s situation and suffering (Strober, 1994), and may be related to decreased help-seeking behavior.

Suicide Prevention and Treatment for Asian American and Pacific Islander Youths

The prevention literature for AA/PI youths is sparse (Harachi, Catalano, Kim, & Choi, 2001). In geographical areas with larger concentrations of AA/PIs, community-driven efforts focused on the prevention of problems such as violence have been described. Such prevention efforts often include programs such as case management, education, and crisis intervention, but the majority of these efforts have not been evaluated (Harachi et al., 2001). We found no programs for prevention of suicide among AI/PI youths.

There similarly are no published evaluations of treatment approaches specifically for AA/PI suicidal adolescents. Research on ethnic matching between provider and family within this population has been shown to predict greater length of treatment and reduced dropout rates (Yeh, Eastman, & Cheung, 1994). Ethnic-specific centers have also been found to yield more positive outcomes and longer duration of treatment compared with mainstream service centers (Yeh, Takeuchi, & Sue, 1994). However, the effects of ethnic matching are a disputed phenomenon, and more research is necessary to understand what factors contribute to better outcomes associated with ethnic matching (e.g., perceived similarities) and what factors contribute to better outcomes irrespective of ethnic matching (e.g., family involvement) within this population.

Inclusion of family members may facilitate assessment and treatment for suicidality. Because AA/PI cultures value interdependence, it is not surprising that Asian Americans receiving mental health treatment tend to have persistent and intensive family member involvement (Lin et al., 1982). Lin and Cheung (1999), for example, caution that clinicians unfamiliar with Asian culture may view family members’ insistence on being involved with treatment as inappropriate or pathological and may run the risk of humiliating clients and their family members through confrontation of this behavior.

As for other treatment considerations, concerns about loss of face may influence risk of suicidal behaviors and may also influence disclosure of such behaviors. Because of this concern, it may be useful for clinicians to assess whether the client perceives suicidal behavior to be related to loss of face and to address such perceptions. Moreover, because shame plays such a prominent role in Asian culture, efforts should be made to reduce the shame associated with mental health problems and help-seeking behavior.

Suicidality Among Latino Youths

Latino youths may be less likely than some other groups to die by suicide, but Latinas in particular report relatively high rates of hopelessness, suicide plans, and suicide attempts in the past year (CDC, 2006b). Most lifetime suicide attempts described by Latinos in the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS) occurred when they were younger than 18 years of age (Fortuna, Perez, Canino, Sribney, & Alegria, 2007). U.S.-born Latino adolescents are more likely to attempt suicide than are foreign-born Latino youths (Fortuna et al., 2007). Adolescent Latinas are consistently twice as likely as Latino males (15% to 8%) to report suicide attempts during the preceding 12 months (CDC, 2006b). Although Latinos in the United States are a heterogeneous Hispanic population (Umaña-Taylor & Fine, 2001), intergroup differences among adolescents have not been well studied. There are common cultural factors, however, that span Latino groups and that can help explain the higher rates of suicide attempts among Latino youths.

Cultural Context of Suicidal Behaviors in Latino Youths

Expectations of obligation to the family appear to play an important role in Latina suicidal behaviors (Zayas, Lester, Cabassa, & Fortuna, 2005) in spite of the fact that family closeness and good relations with parents have been found to be a resiliency factor for suicidality among Latino males and females (Locke & Newcomb, 2005). In Latino cultures, individuals typically are socialized to be oriented toward the centrality of family in their lives, to identify with the family, and to place obligation to family over obligation to the self or outsiders (Lugo Steidel & Contreras, 2003). This orientation, known as familism, influences the sense of individual identity, placing a premium on family unity and cooperation as well as reverence to parents and family elders. The emphasis on collective goals, rather than individualism, among some Latinos, is similar to the emphasis on interdependence in many Asian American cultures.

Adolescents may experience stress because of the conflicting messages that they receive at home and in the majority culture about independence, responsibility to the family, child-rearing practices, and parent–adolescent relations. For example, Latino families may emphasize the demure, controlled, nurturing behavior known as marianismo for their daughters (Castro & Alarcon, 2002) while fostering a behavioral style among their sons that emphasizes being assertive and a family protector, commonly known as machismo (Torres, Solberg, & Carlstrom, 2002). The more dependent, family-centered marianismo may place Latinas at odds with families as needs for peer involvement and approval and strivings for autonomy become prominent in adolescence. Familism is especially evident in recently immigrated Latinos and appears to endure in subsequent generations.

Other factors that influence suicidal behavior are the impact of the often traumatic immigration process and acculturation. For example, some youths endure life-threatening circumstances and are forced to leave some family members behind when they emigrate to this country. Nonetheless, immigrant youths are more likely than their parents to adopt the values, beliefs, and behaviors associated with the new culture (Phinney, Ong, & Madden, 2000), and differential rates of acculturation can create tension in Latino families. Such discrepancies may increase the level of conflicts between parents and adolescents, resulting in dysfunctional outcomes such as suicide attempts and psychological maladjustment (Zayas et al., 2005). Differential adoption of values of the majority culture may be especially evident for U.S.-born Latino youths living with immigrant parents. There also may be differences between Latinos in perceived difficulties experienced with acculturation depending on country of origin. Gil and Vega (1996) found in the Miami, Florida, area that middle-school-age youths from Cuba reported fewer acculturative conflicts, fewer language conflicts, and less perceived discrimination than their peers whose families emigrated from Nicaragua. These differences may be due to the well-established Cuban American community in the Miami area, which facilitates the transition and provides ready opportunities for new immigrants (Gil & Vega, 1996).

Last, in understanding suicidal behavior among Latino adolescents, it is important to consider cultural expressions of distress. The term nervios (nerves) refers to a culturally based somatic expression of anxiety or other emotional distress, which is differentiated from more severe pathology (e.g., schizophrenia, psychotic disorders), referred to as locura (craziness) or fallo mental (mental defect). Zayas and colleagues (2005) have postulated that the behaviors of young Latina suicide attempters bear similarities to the phenomenology of ataques de nervios (e.g., dissociative experiences with loss of control and, sometimes, suicidal behaviors). Ataques are often brought about by a stressful event perceived as a threat to family integrity. Clinical observations suggest that similar types of family relational disruptions that precipitate ataques de nervios may also be operative in the suicide attempts of adolescent Latinas.

Cultural Context of Help-Seeking Among Latino Youths

Both structural barriers and cultural factors affect help-seeking and service utilization among Latinos in general and Latino youths in particular for depression and suicidal behavior. Structural factors in the service-delivery system that inhibit help-seeking and service use among Latino suicide attempters include negative experiences with service procedures (e.g., not understanding and lack of explanation of emergency room procedures) and feeling blamed for the youth’s attempt (Rotheram-Borus et al., 1996). Kataoka, Stein, Lieberman, and Wong (2003) found that Latino youths were least likely to be identified as suicidal and to receive crisis intervention in a large community school district compared with other ethnic groups, despite the aforementioned high rates of suicide attempts. When adolescent Latinas seek help for such problems as depression, family, and relationship problems, they are more likely to turn to informal sources such as peers and family (Rew, Resnick, & Blum, 1997). Newly immigrated Latinos lack familiarity with the service system and are often apprehensive of it because of fear of being reported as being undocumented (Berk, Schur, Chavez, & Frankel, 2000). Moreover, language barriers reduce service utilization for Latinos, especially immigrant parents. Most suicidal Latino youths are U.S.-born English speakers, which makes language differences with providers less of a problem for them than for their parents. Nonetheless, because youths often want parental involvement in their treatments, Spanish-speaking parents may be at a disadvantage, necessitating bilingual clinicians or trained interpreters (in order to avoid the use of the adolescent or another family member as interpreter). Latino families are unlikely to seek mental health services as a first option in help-seeking behavior and may turn to family first (Cabassa, Lester, & Zayas, 2007). Many Latino families also prefer to seek treatments from family physicians rather than mental health specialists (Vega & Lopez, 2001).

Suicide Prevention and Treatment for Latino Youths

There are, to our knowledge, no published, empirically based suicide prevention or treatment interventions developed exclusively for Latinos. However, there have been adaptations of other therapies for other disorders (e.g., depression, substance abuse) that are informative. For example, in recognition of the cultural value of familism, Rosselló and Bernal (2005) adapted cognitive-behavioral and interpersonal therapies for depressed Puerto Rican adolescents so that the intervention involved parents in the treatment of their adolescent. This approach was consistent with the expectations of Latino adolescents regarding the inclusion of their parents and provided opportunities for parents to better understand their adolescent’s socioemotional needs within the perspective of their cultural expectations and the context in which their child was developing.

Engagement of families of suicidal youths is important in any culture, but particularly so for many Latinos, given views about the centrality of family. In this regard, a cost-effective means of engaging parents of Latino adolescent suicide attempters has been reported that includes the use of videotapes to modify treatment expectations and training programs for staff to enhance their sensitivity to Latino parents’ reactions to the suicide attempts and to the service process (Rotheram-Borus et al., 1996). In addition, the efficacy of strategic structural systems engagement (SSSE), an approach for bringing hard-to-reach families into treatment, also has been shown with Latino families (Santisteban et al., 1996). For example, in a study conducted in Miami of youth at risk for drug abuse, SSSE improved overall engagement in therapy. Close analyses revealed that the results differed depending on the Latino group studied. Specifically, non-Cuban Latino families responded extremely well to the intervention, but families of Cuban origin did not. The authors speculated that the Cuban Latinos differed from other Latinos in several key respects, including their levels of acculturation, individualism, and orientation to the values of the mainstream culture. As these findings on SSSE show, differences among Latino groups exist and must be considered in prevention efforts and treatment of suicidal Latino youths and their families.

Discussion

In this article, we have discussed various facets of the cultural context that may influence adolescent suicidal behavior and help-seeking. There are several themes that cut across our discussion for different ethnic groups: acculturative stress and enculturation; the roles of collectivism, religion and spirituality, and the family in culturally sensitive interventions; different manifestations and interpretations of distress in different cultures; and the impact of stigma and cultural distrust on help-seeking and service utilization. We now discuss each of these cross-cutting themes before concluding with comments about the roles of psychologists in addressing the needs of these groups and about future research considerations and opportunities in this area.

Acculturation and Enculturation

Acculturation most obviously is a challenge for adolescents who are newly immigrant or whose parents immigrated to the United States from a different country. However, even for people indigenous to this country, or groups that have been in this country for centuries, there may be pressures and stresses associated with the balancing of assimilating to the majority culture while retaining one’s own cultural identity. Whereas not assimilating to a new culture can be stressful, holding on to some facets of one’s cultural heritage and, in turn, to the supports inherent in that culture may in some cases provide some protection against negative outcomes, including suicidality. In this regard, one explanation for the lower rates of suicide among African American females is that they have access to greater community supports, including extended family and the Black Church. Similarly, among American Indians, enculturation that includes links to traditional activities, Native spirituality, and extended family has been linked to positive outcomes. Particularly given the fact that less acculturated individuals may be less likely than others to use formal mental health services (Snowden & Yamada, 2005), it is important to develop community-based services that are sensitive to, and build on the strengths inherent in, cultural heritage and supports.

The Role of the Family

Regardless of cultural heritage, the involvement and engagement of families are important facets of interventions for suicidal adolescents. In treatment, parents or caretakers help to ensure a safe environment in the home, monitor the suicidal adolescent, and are needed to help resolve family conflicts or stresses that may be related to suicidal behavior. Parents also play an important role in suicide prevention by recognizing the signs of mental health difficulties among youths and seeking help when appropriate. For both African Americans and American Indians, ties to the extended family often are considered sources of support that may be protective against suicidal behavior. In addition, in many Asian American and Latino families, there is a clear expectation of involvement in the therapeutic process because of views of interdependence with the family. Although research needs to elucidate the most effective ways of involving the family in interventions for reducing suicidality, to the extent that the family is involved, mental health professionals will have a better appreciation of the context in which an adolescent has engaged in or considered suicidal behavior.

Collectivism and Individualism

Collectivism is a central value of many cultures, although there are within-group differences in the degree to which groups evidence a collectivist versus an individualistic orientation. Collectivism or interdependence among peoples may offer support or provide a sense of belonging for at-risk individuals that may mitigate risk for suicidal behaviors. However, a collectivist orientation may also increase acculturative stress as well as the awareness of racial oppression and discrimination affecting the larger communities. Psychologists need to be aware of the degree to which the process of acculturation as well as a history of racism and societal pressures have served to erode a sense of community and interdependence among some people, and how a collectivist orientation may serve as both a protective factor and a risk factor for suicidal behaviors in different contexts.

Religion and Spirituality

One notable theme that was evident across cultures was the importance of religion and spirituality. For example, depending on the orientation of the church, involvement with the Black Church has been viewed as protective among some African Americans. In both Asian American and American Indian cultures, views regarding spirituality may shape the type of coping behaviors one engages in, and in American Indian cultures, views regarding traditional healers and healing rituals and ceremonies are inextricably linked with views of spirituality. People of different cultural backgrounds understandably may not seek help or respect intervention efforts if they do not perceive that their faith or beliefs will be honored or respected. Many individuals or families, even when seeking formal mental health services, are also seeking assistance from traditional healers or from their faith communities. For interventions to be effective within different cultural contexts, they must be flexible enough to be respectful of a culture’s faith traditions and belief systems. Partnerships with faith communities may provide many opportunities for suicide prevention activities within a culturally acceptable context.

Different Manifestations and Interpretations of Distress

Different cultural groups may manifest distress and interpret signs of distress differently. For example, both African American and Asian American youths may not verbalize suicide thoughts or intent as readily as other groups, and among Latinas, the series of behaviors that may lead up to suicidal behavior may be interpreted as part of the cultural syndrome nervios. Physicians, teachers, and other “gatekeepers” who are in a position to help identify adolescents at risk for suicidality, but who are not from the same culture as adolescents and their families, need to be especially alert to the fact that distress is not always expressed in the same ways among individuals from different backgrounds. In addition, clinicians need to be aware that even when suicidal thoughts are not readily volunteered, they often can be elicited with careful and sensitive assessment.

Cultural Mistrust, Stigma, and Help-Seeking

In each of the groups reviewed, there appeared to be stigma associated with mental health difficulties, including suicidality, and often with help-seeking. Stigma unfortunately is often accompanied by apprehensions and distrust about service use because of historical abuses, lack of familiarity with systems, and experiences with mental health professionals who are not culturally competent or sensitive. Education provided in faith communities, in the schools, or in the wider communities may be helpful in reducing stigma and raising awareness of potential mental health problems among youths and the availability of culturally sensitive resources for youths at risk for suicidal behavior. Culturally sensitive screening or routine assessment of suicide risk in settings not associated with mental health treatment (e.g., schools, primary care settings) may also be useful in identifying youths at risk.

Future Research Directions and Challenges

There are several different areas in which additional research is needed to help us better understand the context of suicidal behaviors among youths of different cultural backgrounds. Additional research examining culture-specific triggers or processes leading to suicidal behavior as well as culture-specific risk and protective factors is greatly needed. There are many hypotheses about factors potentially related to suicidal behavior and help-seeking (e.g., the ethic of John Henryism among African Americans) that warrant closer examination. In addition, one area in particular that has been under-researched is the reactions from family and community regarding suicidal behavior that may serve to increase or decrease risk for a recurrence of suicidal behavior.

The number of culturally sensitive prevention and treatment interventions for suicidal youths appears to be extremely limited. In this regard, an understudied area is the degree to which interventions focused on reducing risk factors (e.g., hopelessness in the community) and enhancing culturally relevant protective factors or supports (e.g., ties to elders or cultural traditions) can reduce suicidality. In addition, an important area of inquiry is the degree to which informal or traditional sources of help within the community are effective in addressing suicide risk among youths, particularly given the fact that suicidal adolescents may be more comfortable speaking with lay helpers or native healers than talking about difficulties with strangers in unfamiliar settings.

Multifaceted community-based efforts may be especially useful in culturally relevant suicide prevention. For example, the successful Western Athabaskan suicide prevention program had multiple components including a network of natural helpers, community education, suicide risk screening, postvention following suicidal behavior (e.g., support for individuals or families who have lost loved ones due to suicide), and adoption of guidelines for preventing suicide clusters. Nonetheless, for sustainability and increased effectiveness, such efforts at suicide prevention need to be developed in collaboration with the community, or to arise from the community itself, rather than be externally imposed. Efforts developed by and implemented by home communities have a greater likelihood of sustainability because of individual and community investment in the programs and because participants are able to experience first-hand the positive changes that occur as a result of interventions. Such community-based efforts have not often been the subject of research scrutiny and evaluation, but they have much promise in reducing adolescent suicidal behaviors and related problems. In this regard, it is of note that the Garrett Lee Smith Memorial Suicide Prevention Act recently provided funding for suicide prevention activities and their evaluation in 13 tribal communities.

One challenge in evaluating community-based efforts in suicide prevention is the fact that it is difficult to find appropriate comparisons against which to gauge the effects of the intervention. Without nontreated comparison sites or communities, it can be difficult to disentangle the effects of the intervention from changes occurring in the greater population over time. Selecting similar communities that are not initiating prevention efforts can also be problematic insofar as the different sets of communities may differ in their readiness to change. In this regard, innovative research approaches such as the dynamic wait list design may be useful and informative (Brown, Wyman, Guo, & Peña, 2006). Practically, it often is impossible to introduce a new intervention simultaneously at different sites (e.g., different tribal communities). Building upon this, the timing or sequence of introduction of intervention to communities can be randomized, with the communities with the latest introductions of the intervention providing important comparison data against which the effects of the intervention introduced in earlier sites can be compared. To ensure that well-intended suicide prevention efforts actually have desired effects, additional innovative approaches to evaluation are needed.

Caveats and Closing Comments

Although we have focused on the broad differences between cultural groups in factors that may affect adolescent suicidal behavior, there also is a great deal of diversity within these groups. This diversity is apparent both in differing rates of suicidal behavior and cultural differences among individuals within racial and ethnic groups. Future research should focus much more on understanding (a) within-ethnic-group differences and how they are associated with different patterns of suicidal behaviors and (b) cultural differences that may increase or decrease the likelihood of thinking about or attempting suicide and seeking help or support.

In addition, when differences are observed among people of color or of different countries of origin, there is a tendency to attribute these differences to their ethnicity. However, newly immigrated individuals and individuals from ethnic groups who have been historically oppressed or disadvantaged may disproportionately have limited educational backgrounds or financial means. The socioeconomic status and educational background of clients and families often contribute to the cultural context or milieu but should not be confused with differences attributable to ethnicity (Hall, 2001).

Many of the cultural groups described have been subject to trauma and political repression, either in their countries of origin, during the immigration process, or in this country. Interventions that reinforce the protective supports and the cultural strengths of these communities are needed to help address this trauma and its effect on mental health and to empower groups that have been the victims of oppression or that have been underserved (Comas-Díaz, 2000).

The Ethical Principles and Code of Conduct and the Multicultural Guidelines of the APA (2002, 2003) underscore the importance of understanding cultural context. Particularly given the history of racism in psychology (e.g., the eugenics movement), psychologists need to be aware of the political climate and societal forces that may affect how ethnic minorities and underserved groups are viewed and treated and how this may affect their mental health needs and access to services. Psychologists have a special responsibility to combat racism and promote social equity (Comas-Díaz, 2000). In this role, and through the development of new and effective culturally sensitive and appropriate interventions, they can hopefully affect those facets of cultural context that are associated with suicidal behaviors among young people.

Biographies

David B. Goldston

David B. Goldston

Sherry Davis Molock

Sherry Davis Molock

Leslie B. Whitbeck

Leslie B. Whitbeck

Jessica L. Murakami

Jessica L. Murakami

Luis H. Zayas

Luis H. Zayas

Gordon C. Nagayama Hall

Gordon C. Nagayama Hall

Support for preparation of this article was provided by the following sources: National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Grants K24-MH066252 and R34-MH067904, and Contract 280-03-1606 from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to Macro International (David B. Goldston); NIMH Grant K01-MH002003 (Sherry Davis Molock); National Institute of Drug Abuse Grant R01-DA013580 and NIMH Grant R01-MH067281 (Leslie B. Whitbeck); NIMH Grant R01-MH070689 (Luis H. Zayas); and NIMH Grants R01-MH058726 and R25-MH062575 (Gordon C. Nagayama Hall).

Throughout this article, the term White is used to refer to European Americans who are not of Hispanic descent. The term African American or Black is used to refer to individuals of African descent. The terms American Indian and Alaska Native are used to refer to the indigenous people of the American continents. The term Latino is used to refer to individuals of Hispanic descent, primarily from the Caribbean, Central American, or South American areas. The term Asian American/Pacific Islander is used to refer to individuals who emigrated (or whose families emigrated) from either Central, Southern, or Eastern Asia or from the Pacific Islands. These racial and ethnic categories are used because of their widespread use in the literature (including government reports regarding mortality and risk behaviors).

References

- Allen J, Mohatt G, Rasmus S, Hazel K, Thomas L the PA Team. The tools to understand: Community as co-researcher on culture-specific protective factors for Alaska natives. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community. 2006;32:41–59. doi: 10.1300/J005v32n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez A. The savage God: A study of suicide. New York: Random House; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. American Psychologist. 2002;57:1060 –1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Guidelines for multicultural education, training, research, practice, and organizational change for psychologists. American Psychologist. 2003;58:377–402. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.5.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals J, Novins D, Whitesell N, Spicer P, Mitchell C, Manson S. Prevalence of mental disorders and utilization of mental health services in two American Indian reservation populations: Mental health disparities in a national context. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1723–1732. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechtold D. Cluster suicide in American Indian adolescents. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 1988;1:26 –35. doi: 10.5820/aian.0103.1988.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belgrave F, Reed M, Plybon L, Butler D, Allison K, Davis T. An evaluation of sisters of Nia: A cultural program for African American girls. Journal of Black Psychology. 2004;30:329 –343. [Google Scholar]

- Bender E. APA, AACAP suggest ways to reduce high suicide rates in Native Americans. Psychiatric News. 2006 June 16;41(12):6. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett G, Marcellus M, Sollers J, Edwards C, Whitfield K, Brandon D, Tucker R. Stress, coping, and health outcomes among African-Americans: A review of the John Henryism hypothesis. Psychology and Health. 2004;19:369 –383. [Google Scholar]

- Berk M, Schur C, Chavez L, Frankel M. Health care use among undocumented Latino immigrants. Health Affairs. 2000;19:51–64. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.4.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blank M, Mahmood M, Fox J, Guterbock T. Alternative mental health services: The role of the Black church in the South. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:1668 –1672. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.10.1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brave Heart M. The return to the Sacred Path: Healing the historical trauma and historical unresolved grief response among the Lakota through a psychoeducational group intervention. Smith College Studies in Social Work. 1998;68:287–305. [Google Scholar]

- Breland-Noble A. Black adolescents. Psychiatric Annals. 2004;34:535–538. doi: 10.3928/0048-5713-20040701-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C, Wyman P, Guo J, Peña J. Dynamic wait-listed designs for randomized trials: New designs for prevention of youth suicide. Clinical Trials. 2006;3:259 –271. doi: 10.1191/1740774506cn152oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui K, Takeuchi D. Ethnic minority adolescents and the use of community mental health care services. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1992;20:403–417. doi: 10.1007/BF00937752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burr J, Hartman J, Matteson D. Black suicide in U.S. metropolitan areas: An examination of the racial inequality and social integration-regulation hypothesis. Social Forces. 1999;77:1049 –1081. [Google Scholar]

- Cabassa L, Lester R, Zayas L. “It’s like being in a labyrinth:” Hispanic immigrants’ perceptions of depression and attitudes toward treatments. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2007;9:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9010-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]