Abstract

The relative reactivity of various functional groups towards alkyne electrophilic cyclization reactions has been studied. The required diarylalkynes have been prepared by consecutive Sonogashira reactions of appropriately substituted aryl halides and competitive cyclizations have been performed using I2, ICl, NBS and PhSeCl as electrophiles. The results indicate that the nucleophilicity of the competing functional groups, polarization of the alkyne triple bond, and the cationic nature of the intermediate are the most important factors in determining the outcome of these reactions.

Introduction

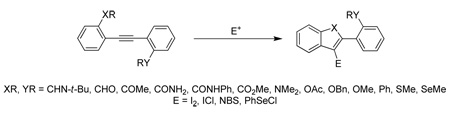

Alkynes are versatile building blocks in organic synthesis. A wide range of carbocycles and heterocycles have been prepared by the electrophilic cyclization of functionally-substituted alkynes1 and by transition metal-catalyzed annulations.2 Recently, we and others have reported that the electrophilic cyclization of alkynes using halogen, sulfur and selenium electrophiles can be a very powerful tool for the preparation of a wide variety of interesting carbocyclic and heterocyclic compounds (Scheme 1), including benzofurans,3 furans,4 benzothiophenes,5 thiophenes,6 benzopyrans,7 benzoselenophenes,8 selenophenes,9 naphthols,10 indoles,11 quinolines,12 isoquinolines,13 α-pyrones,14 isocoumarins,14 isochromenes,15 isoindolinones,16 naphthalenes17 and polycyclic aromatics,18 isoxazoles,19 chromones,20 bicyclic β-lactams,21 cyclic carbonates,22 pyrroles,23 furopyridines,24 spiro[4.5]trienones,25 coumestrol and coumestans,26 furanones,27 benzothiazine-1,1-dioxides,28 etc.29

Scheme 1.

Electrophilic Cyclization

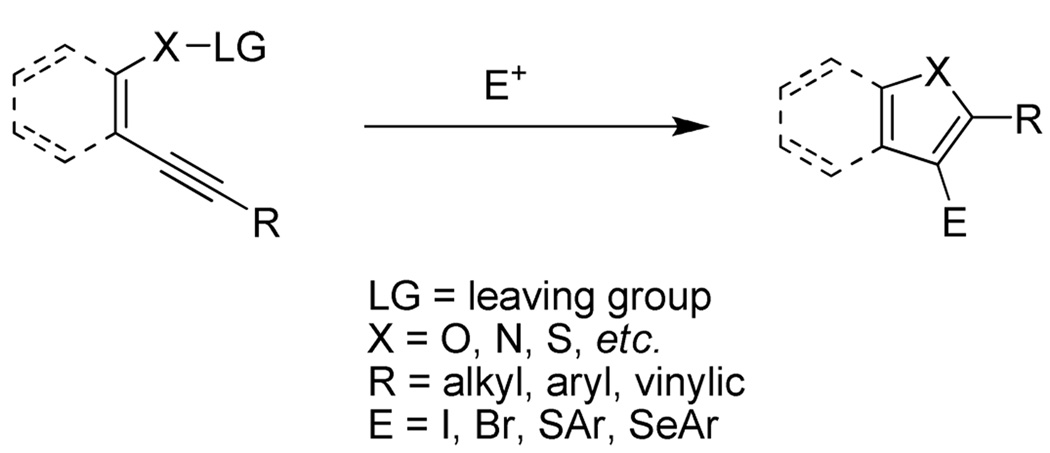

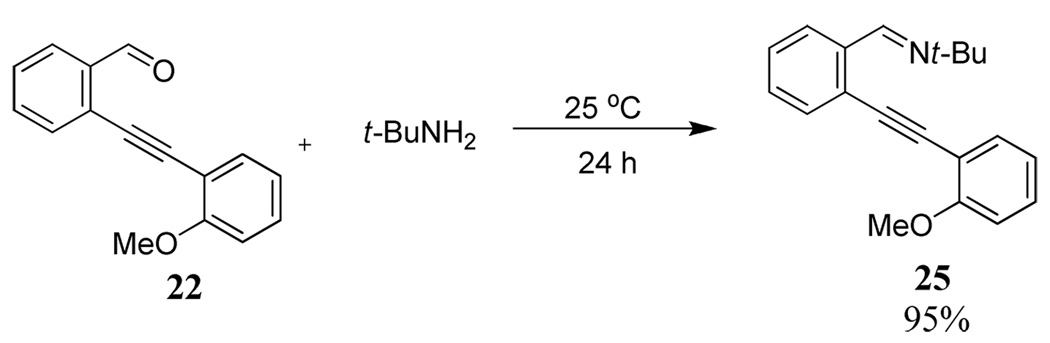

In general, these electrophilic cyclization reactions are very efficient, afford clean reactions, proceed under very mild reaction conditions in short reaction times, and tolerate almost all important functional groups. Furthermore, the iodine-containing products can be further elaborated to a wide range of functionally-substituted derivatives using subsequent palladium-catalyzed processes. These reactions are generally believed to proceed by a stepwise mechanism involving electrophilic activation of the alkyne carbon-carbon triple bond, intramolecular nucleophilic attack on the cationic intermediate, and subsequent dealkylation (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

General Mechanism

The success of this reaction prompted us to establish the relative reactivity of various functional groups towards cyclization. This has been accomplished by studying competitive cyclizations using halogen and selenium electrophiles.

Results and Discussion

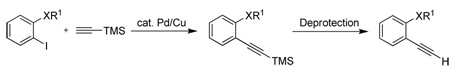

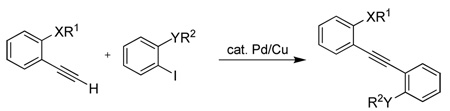

This electrophilic cyclization methodology has been applied to a variety of unsymmetrical functionally-substituted diarylalkynes and the resulting products characterized in order to determine the relative reactivities of various functional groups towards electrophilic cyclization. The required diarylalkynes are readily prepared by consecutive Sonogashira reactions30 of appropriately substituted aryl halides. Thus, Sonogashira substitution with trimethylsilyl acetylene, removal of the TMS group, followed by a second Sonogashira reaction, generally affords moderate to excellent yields of the desired diarylalkynes. The results for the preparation of the intermediate terminal alkynes and the subsequent diarylalkynes are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2 respectively.

Table 1.

Preparation of the Requisite Terminal Alkynes a

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | XR1 | Coupling conditionsb |

TMS-alkyne (% yield) |

Deprotection conditionsc |

Terminal alkyne (% overall yield) |

| 1 | SMe | A | 1 (97) | aq KOH/MeOH 0.5 h/25 °C | 5 (83) |

| 2 | CO2Me | A | 2 (100) | KF-2H2O/MeOH 36 h/25 °C | 6 (82) |

| 3 | Ph | A | -d | - | - |

| 4 | CONHPh | B | 3 (80) | KF-2H2O/MeOH 0.5 h/25 °C | 7 (71) |

| 5 | NMe2 | C | 4 (74) | Aq NaOH/MeOH/ether 0.16 h/25 °C | 8 (48) |

All reactions have been run with 5 mmol of o-iodoarene.

Reaction conditions: (A) 1.2 equiv of alkyne, 2 mol % PdCl2(PPh3)2, 1 mol % CuI, 20 mL of Et3N, 25 °C. (B) 1.3 equiv of alkyne, 3 mol % PdCl2(PPh3)2, 2 mol % CuI, 4 equiv of DIPA, DMF, 65 °C. (C) 1.2 equiv. of alkyne, 1 mol % PdCl2(PPh3)2, 3 mol % CuI, 0.9 equiv of Et3N, DMF, 25 °C.

See the Supporting Information for the experimental details.

A complex reaction mixture was obtained.

Table 2.

Preparation of the Diarylalkynes a

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | XR1 | YR2 | time (h) | temp (°C) | product | yield (%) |

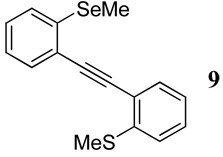

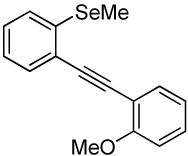

| 1 | SMe | SeMe | 24 | 25 | 9 | 80 |

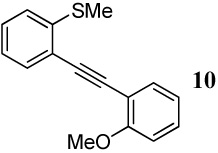

| 2 | SMe | OMe | 6 | 60 | 10 | 90 |

| 3 | SMe | CO2Me | 14 | 25 | 11 | 98 |

| 4 | SMe | CONHPh | 1 | 25 | - | -b |

| 5 | SMe | NMe2 | 24 | 25 | - | -c |

| 6 | CO2Me | SeMe | 10 | 60 | 12 | 87 |

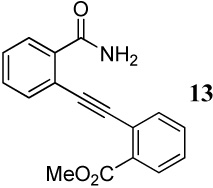

| 7 | CO2Me | CONH2 | 2 | 25 | 13 | 83 |

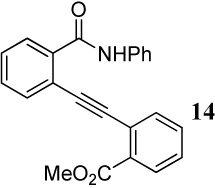

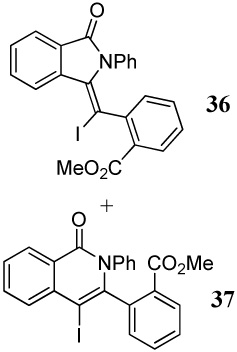

| 8 | CO2Me | CONHPh | 4 | 60 | 14 | 62d |

| 9 | CO2Me | NMe2 | 8 | 25 | 15 | 78 |

| 10 | CO2Me | OMe | 4 | 25 | 16 | 74 |

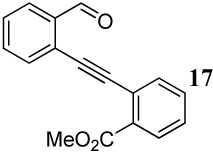

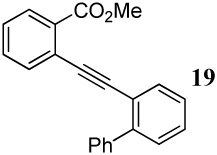

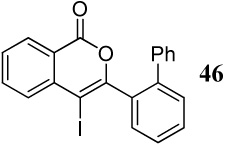

| 11 | CO2Me | CHO | 14 | 25 | 17 | 84 |

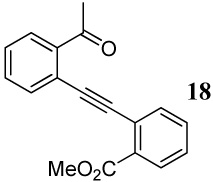

| 12 | CO2Me | COMe | 4 | 25 | 18 | 88 |

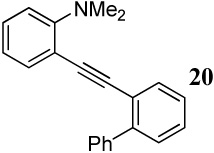

| 13 | CO2Me | Ph | 2 | 25 | 19 | 70 |

| 14 | CONHPh | SMe | 3 | 65 | - | -b,e |

| 15 | CONHPh | SeMe | 18 | 65 | - | -c,e |

| 16 | NMe2 | Ph | 3 | 75 | 20 | 35 |

| 17 | NMe2 | Ph | 2 | 110 | 20 | 74f |

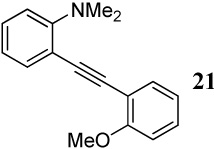

| 18 | OMe | NMe2 | 24 | 25 | 21 | 70 |

| 19 | OMe | CHO | 7 | 25 | 22 | 80 |

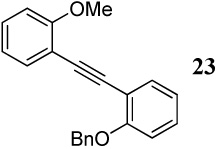

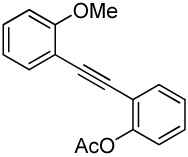

| 20 | OMe | OBn | 8 | 60 | 23 | 72 |

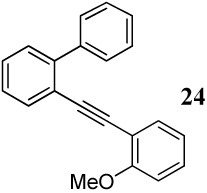

| 21 | OMe | Ph | 2 | 25 | 24 | 94 |

| 22 | CHO | NMe2 | 6 | 60 | - | -b |

All reactions were run using 1 mmol of iodoarene and 1.2 equiv of alkyne, 2 mol % PdCl2(PPh3)2, 1 mol % CuI, and 5 mL of Et3N.

An inseparable mixture was obtained.

The desired compound was not observed.

Four mol % of CuI was used.

Two milliliters of DMF were used to dissolve the alkyne.

The reaction was carried out in toluene using a modified procedure; see the Supporting Information.

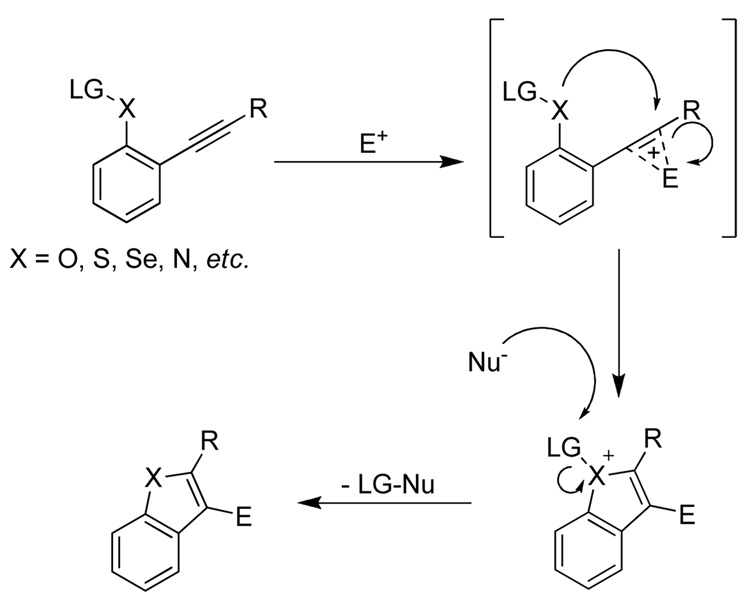

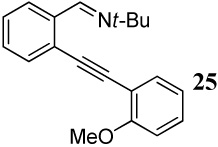

The diarylalkyne 25 containing t-butyl imine functionality was prepared by further derivatization of diarylalkyne 22 using a known procedure13 (Scheme 3). However, similar derivatization starting with the diarylalkyne 17 resulted in a complex reaction mixture.

Scheme 3.

Imine formation

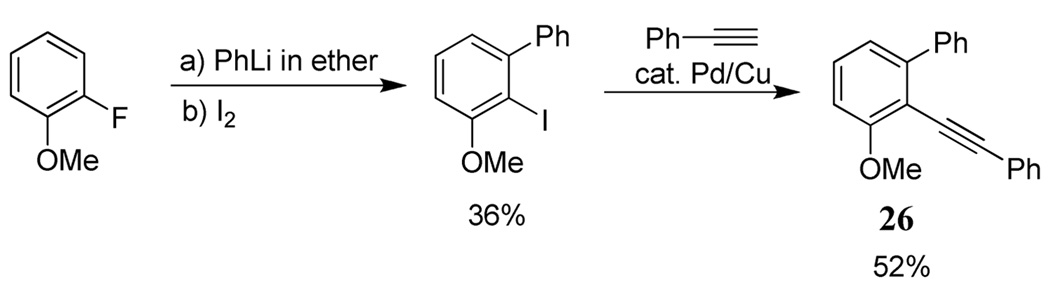

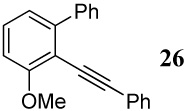

In addition to the above substrates, a different type of diarylalkyne 26 bearing both of the competing groups (OMe and Ph) on the same aromatic ring has been prepared as shown in Scheme 4. The requisite iodoarene was prepared using a previously reported procedure.31

Scheme 4.

Preparation of diarylalkyne 26 with both competing groups on the same ring

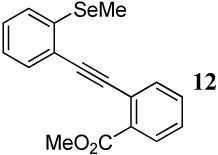

After preparing the desired diarylalkynes, we subjected these compounds to the previously established and already optimized electrophilic cyclization conditions for each class of heterocycle being prepared (Table 3). In most cases, reaction conditions that are appropriate for both of the competing functional groups present in the diarylalkyne in question have been used (entries 1–3). In those cases where common reaction conditions for both functional groups have not been previously reported, more than one set of reaction conditions has been tried in order to allow the functional groups to react under supposedly “optimal” conditions. For example, entries 4 and 5 in Table 3 involve the same diarylalkyne 12, yet each entry uses varying amounts of different electrophiles in compliance with the previously reported reaction conditions for methylseleno and carbomethoxy functional groups, respectively.8a,14

Table 3.

Results of the competitive cyclizations a

| Entry | Substrate | Electrophile | Time (h) | product(s) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

1.1 I2 | 0.16 |  |

82b |

| 2 |  |

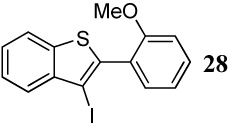

1.2 I2 | 1 |  |

96 |

| 3 |  |

1.1 I2 | 0.5 |  |

91c |

| 4 |  |

1.2 I2 | 1 |  |

98d |

| 5 | 12 | 1.2 ICl | 29 | 93d | |

| 6 |  |

1.2 I2 | 1 |  |

93 |

| 7 | |||||

| 7 | 11 | 1.2 ICl | 0.5 |

30 + |

93 |

| 31 | 7 | ||||

| 8 | 11 | 1.5 PhSeCl | 1 |  |

56e |

| 44e | |||||

| 9 |  |

1.2 I2 | 1 |  |

95 |

| 10 |  |

2 PhSeCl | 3 |  |

70 |

| 11 |  |

1.2 I2 | 1 | - | -f |

| 12 | 13 | 3 I2 | 1 | - | -f,g |

| 13 |  |

1.2 I2 | 1 |  |

45 |

| 18 | |||||

| 14 | 14 | 1.2 ICl | 1 |

36+ |

35 |

| 37 | 30 | ||||

| 15 |  |

1.2 I2 | 1.5 |  |

57h |

| 16 |  |

1.2 I2 | 1 |  |

98 |

| 17 | 16 | 2 ICl | 0.5 | 39 | 96 |

| 18 | 16 | 1.5 PhSeCl | 0.5 | E = SePh 40 |

95 |

| 19 |  |

1.2 I2 | 2 | - | -i |

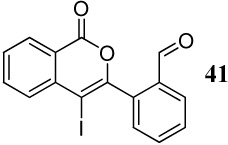

| 20 | 17 | 1.2 ICl | 0.5 |  |

25j |

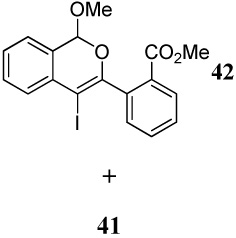

| 21 | 17 | 1.2 I2, 1.2 MeOH/1.0 K2CO3 |

10 |  |

82k |

| 12 | |||||

| 22 |  |

1.2 I2 | 1 | - | -f |

| 23 | 18 | 1.2 ICl | 0.5 | - | -f |

| 24 | 18 | 1.2 I2, 1.2 MeOH/1.0 K2CO3 |

2 | - | -f |

| 25 |  |

2 I2 | 3 |  |

4:1l |

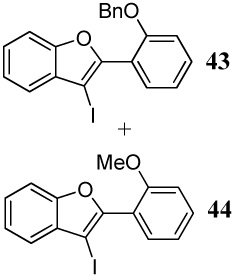

| 26 | 23 | 1.2 ICl | 3 | 43 + 44 | 6:1l |

| 27 |  |

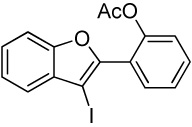

2 I2 | 3 |  |

95m |

| 28 |  |

2 I2 | 2 |  |

78 |

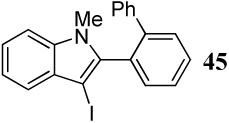

| 29 | 20 | 1.2 ICl | 0.5 | - | -f |

| 30 | 20 | 1.2 NBS | 1 | - | -f |

| 31 |  |

2 ICl | 3 |  |

90 |

| 32 |  |

2 I2 | 3 | - | -f |

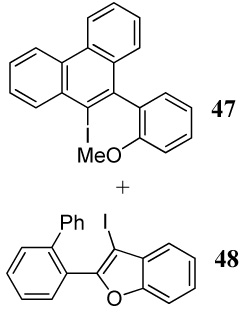

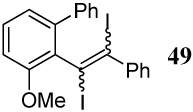

| 33 | 24 | 1.2 ICl | 0.5 |  |

49e |

| 33e | |||||

| 34 |  |

6 I2 | 2 |  |

89d |

| 35 | 26 | 1.2 ICl | 1 | - | -d,n |

Unless otherwise stated, all reactions have been carried out on a 0.25 mmol scale in 5 ml of methylene chloride at room temperature. All yields are isolated yields after column chromatography.

A small amount of the corresponding benzothiophene product (~7%) was observed by GC-MS analysis; however, it could not be isolated.

This result has previously been reported in the literature (see reference 8a).

This reaction hasf been carried out on a 0.10 mmol scale.

The reported yield is the average of two runs.

This reaction resulted in a complex mixture of unidentifiable products.

MeCN was used as the reaction solvent and 3 equiv of NaHCO3 were added as a base.

The corresponding indole (~8%) was also observed by GC-MS analysis. However, it could not be isolated.

No reaction occurred; the starting material was recovered. A complex mixture was obtained upon longer reaction.

This was the only isolated product. The rest of the product mixture was complex and inseparable.

This product decomposed quickly; see the Supporting Information for details.

An inseparable complex mixture was obtained. This ratio is based on GC-MS data.

This result has previously been reported in the literature (see reference 3b).

An alkyne ICl addition product whose structure is similar to compound 49 in entry 34 was obtained.

The results of the competition studies are summarized in Table 3. Before discussing individual results, it should be noted that a close examination of the results suggests that a number of factors affect the cyclization. These include electronic (relative nucleophilicity of the functional groups, polarization of the carbon-carbon triple bond, and the cationic nature of the intermediate) and steric factors (hindrance and geometrical alignment of the functional groups), as well as the nature of the electrophile. Three kinds of results have been observed for these competitive cyclizations. (1) Only one of the two possible products has been obtained. This is most common, indicating that there is a hierarchy of functional group reactivity toward the electrophilic cyclizations. Assuming that the various factors mentioned above may affect the cyclization, the dominance of one functional group over another can be attributed to any one or a combination of two or more factors operating in favor of the one functional group over the other. (2) A mixture of both possible products has been observed. This occurs less commonly, but even in these cases, one product is often obtained in a significantly higher yield than the other, indicating that one group is usually significantly more reactive towards cyclization. (3) A complex reaction mixture is obtained. Although this does not provide any substantial information about the relative reactivity, it points to the fact that either the more reactive functional group is not compatible with the particular reaction conditions or neither of the two functional groups involved has a dominant reactivity, thus resulting in a complex reaction mixture.

It also should be noted that since these reactions are very fast in general, and may involve multiple steps and intermediates, it is quite difficult to strictly assign the reactivity of any particular functional group to any one factor mentioned above. Indeed, we assume that in some cases one or more factors are operating in opposition to each other, resulting in a mixture of products. However, in the following discussion, we will attempt to ascribe the relative reactivity of various functional groups to what we believe to be the most important factors.

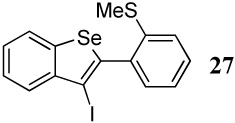

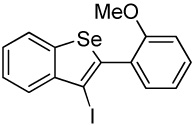

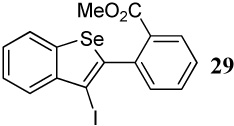

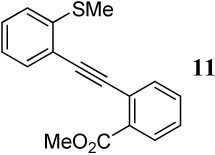

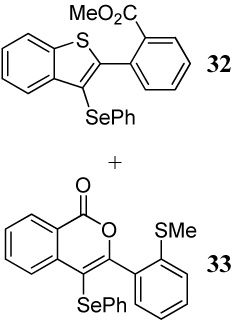

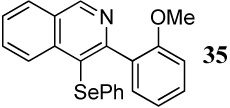

With regard to the results of individual experiments, entry 1 (Table 3) demonstrates the competitive cyclization of a methylsulfanyl group versus a methylseleno group. Benzoselenophene 27 was isolated as the major product of the reaction using I2 as the electrophile. In another experiment (not shown in Table 3 as the product could not be purified completely), when PhSeCl was used as the electrophile, the corresponding benzoselenophene was again formed as the major product in high yield. These results can be attributed to the higher nucleophilicity of selenium compared to sulfur, due to its lower electronegativity and higher polarizability. Similarly, in entry 2, when diarylalkyne 10 (containing methylsulfanyl and methoxy as competing functional groups) was subjected to electrophilic cyclization, benzothiophene 28 was formed exclusively in an excellent yield. It is a general observation that the nucleophilicity increases as one descends a column in the periodic table.32 This trend is also observed when examining the results of entries 3–14, where the nucleophilicity of the competing functional groups governs the resulting cyclization. Thus, methylseleno is more reactive than methoxy (entry 3) and carbomethoxy functional groups (entries 4 and 5).

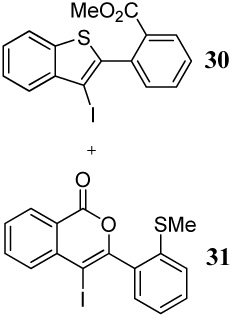

Entries 6–8 involve the competition between a methylsulfanyl group and a carbomethoxy group under different conditions. In all three cases, benzothiophene derivatives are the major but not exclusive products, again suggesting that the greater nucleophilicity of sulfur over oxygen controls the reaction. It is noteworthy, however, that changing the electrophile to PhSeCl in entry 8 significantly affects the product distribution, presumably because of the nature of the electrophile.

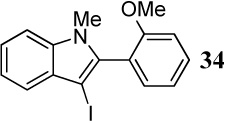

When competing nucleophilic atoms are in the same row in the periodic table, the results show that the nucleophilicity still governs the outcome of the cyclization. Thus, nitrogen nucleophiles are more reactive than oxygen nucleophiles. This is exemplified by the cyclization of diarylalkyne 21 bearing an NMe2 group and a methoxy group (entry 9), which leads to exclusive formation of the corresponding indole 34 in an excellent yield. Similarly, a t-butyl imine group was found to be more reactive than a methoxy functional group (entry 10). Cyclization reactions involving diarylalkyne 13 (entries 11 and 12) resulted in complex reaction mixtures. It has been observed previously by us that a primary amide does not afford the desired cyclized product and generally results in a complex reaction mixture.16 On the other hand, the related diarylalkyne 14 containing an N-phenyl amide undergoes cyclization cleanly with I2, affording two regioisomeric products, both resulting from cyclization by the CONHPh group (entry 13). Using ICl (entry 14) also resulted in the same set of products, although with reduced regioselectivity in accordance to our previously reported results.16

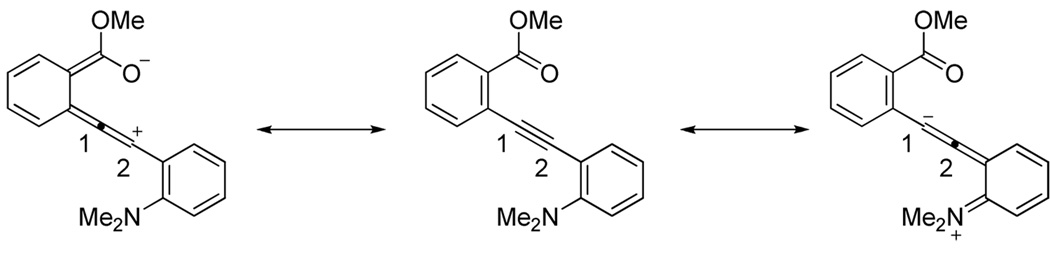

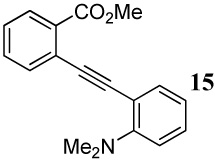

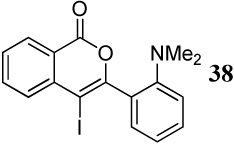

Entry 15 involving a competition between a carbomethoxy group and an N,N-dimethylamino group represents a special case where the corresponding isocoumarin 38 was isolated as the major product of the cyclization. Formation of the isocoumarin product is presumably the result of one (or a combination) of the two factors working in favor of the carbomethoxy group: (1) The electronics of the two substituents polarize33 the carbon-carbon triple bond in a way that leads to a more cationic C2 and anionic C1, thus facilitating nucleophilic attack at the more electrophilic C2 position (Figure 1), and/or (2) there seems to be a more favorable geometrical alignment of the ester functionality when compared to the N,N-dimethylamino group.

Figure 1.

Carbomethoxy versus an N,N-dimethylamino group

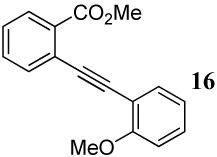

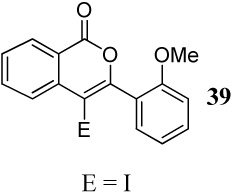

Entries 16–27 involve competitions among various oxygen nucleophiles. In a competition between a methoxy group and a carbomethoxy group (entries 16–18) using I2, ICl and PhSeCl as the electrophiles, the corresponding isocoumarin derivatives are formed exclusively in excellent yields. Analogous to the previous case (entry 15 and Figure 1), formation of the isocoumarin products is again presumably due to the electronic polarization of the triple bond, which increases the electrophilicity of the carbon being attacked by the carbomethoxy group, and also a more favorable geometrical alignment of the ester functionality when compared to the methoxy group.

Entries 19–21 involve the competitive cyclization of an aldehyde and an ester group under different reaction conditions. When iodine is used as the electrophile (entry 19), the starting material was recovered after 2 h. If the reaction was allowed to stir for a longer time, a complex reaction mixture was obtained. Using ICl as the electrophile (entry 20), a complex mixture was obtained and only isocoumarin derivative 41 was isolable in a 25% yield. It should be noted that the aldehyde group after nucleophilic attack becomes cationic and needs an external nucleophile to neutralize the positive charge. Thus, the same reaction was performed with methanol as an external nucleophile (entry 21). This time, isochromene derivative 42 was isolated as the major product, indicating the impact of an external nucleophile on the cyclization. Similar reactions involving a methyl ketone and a carbomethoxy group as competing entities resulted in complex mixtures of unidentifiable products (entries 22–24).

The cyclizations reported in entries 25 and 26 involving methoxy and benzyloxy functional groups resulted in inseparable complex mixtures. However, the GC-MS analyses of the product mixtures indicated the presence of two benzofuran products 43 and 44 in varying ratios, the major product resulting from cyclization by the OMe group. These results are presumably a consequence of the greater steric hindrance of the benzyloxy group.

Entry 27 involves a competition between a methoxy group and a relatively electron-poor acetoxy group. As the reaction outcome, the methoxy cyclization product is formed exclusively in high yield. The result of this reaction again suggests that electronic factors play a crucial role in these cyclization reactions. We have taken advantage of this high selectivity and subsequent palladium-catalyzed carbonylation to prepare coumestrol and a variety of related coumestans.26

Entries 28–35 involve competition of an aryl ring versus nitrogen and different oxygen nucleophiles. In the cyclization of diarylalkyne 20 containing an NMe2 group and a phenyl ring (entries 28–30), the corresponding indole 45 is obtained when I2 is used as the electrophile, presumably due to the more nucleophilic NMe2 group. The reaction of diarylalkyne 20 with ICl or NBS resulted in complex reaction mixtures. However, mass spectral analysis of the mixture resulting from the NBS cyclization (entry 30) indicated the presence of the corresponding indole, an observation that is in accord with that of entry 28. In a competition between a carbomethoxy group and a phenyl group (entry 31), the exclusive formation of isocoumarin derivative 46 can be explained based on the greater nucleophilicity of the carbomethoxy group when compared to the electron-poor phenyl ring.

The cyclization of diarylalkyne 24 bearing a phenyl ring and an o-methoxy group has also been studied (entries 32 and 33). Using iodine as the electrophile resulted in a complex mixture of inseparable products, but analysis of the crude 1H NMR and mass spectral data suggested preferential cyclization on the phenyl ring. Aromatic rings have previously been observed by us to give complex reaction mixtures upon reaction with iodine.17 Using ICl as the electrophile (entry 33) resulted in a mixture of products resulting from participation by both the phenyl ring and the methoxy group, with the phenyl cyclized phenanthrene derivative 47 being the major product. Presumably, the cationic character of the intermediate and/or the higher nucleophilicity of the phenyl ring when compared to the methoxy group account for this observation. In competition studies employing diarylalkyne substrate 26 containing both of the competing functional groups (Ph and methoxy) on the same phenyl ring (entries 34 and 35), the only products observed using either I2 or ICl were products of addition of the iodine-containing reagent to the carbon-carbon triple bond. These results can again be rationalized by assuming the cationic nature and the electronics of the intermediates involved in these reactions.

Conclusions

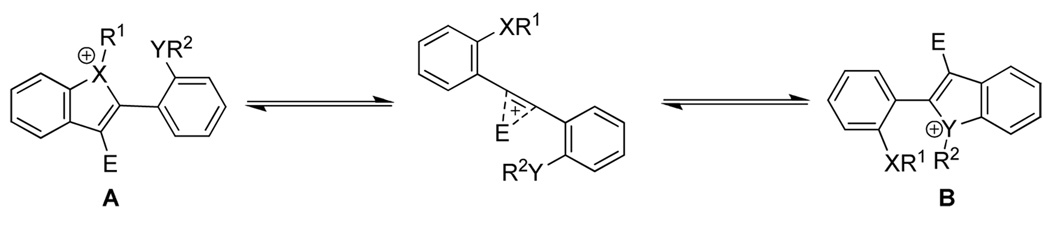

The results of competitive electrophilic cyclizations using halogen and selenium electrophiles on a wide variety of functionally-substituted diarylalkynes have been reported. The results suggest that a number of factors affect the cyclization. These include electronic (the relative nucleophilicity of the functional groups, and the cationic nature of the intermediate) and steric factors (hindrance and geometrical alignment of the functional groups), and the nature of the electrophile. It should be noted that although the nucleophilicity of the participating functional groups, the polarization of the carbon-carbon triple bond, and the cationic nature of the intermediate seem to be the crucial factors determining the outcome of these reactions, the possibility of some reactions being reversible (Figure 2) before the loss of R1 or R2 cannot be ruled out. Thus in such cases, the selectivity might also be controlled by the relative stability of the cyclized intermediate ions (A and B).

Figure 2.

Possible equilibrium among reaction intermediates

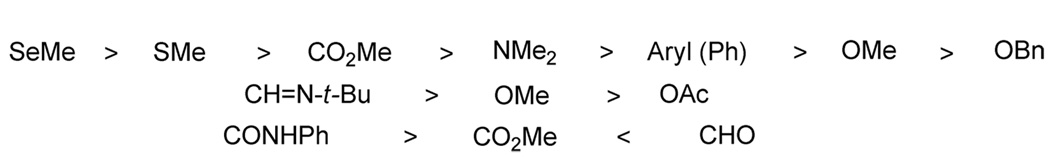

The following pattern has been observed for the relative reactivity of various functional groups (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Relative reactivity of the functional groups towards cyclization

Experimental Section

General procedure used for the preparation of the diarylalkynes

To a solution of iodoarene (1.0 mmol), PdCl2(PPh3)2 (0.014 g, 2 mol %), and CuI (0.002 g, 1 mol %) in TEA (4 mL) (stirring for 5 min beforehand), 1.2 mmol of trimethylsilylacetylene (1.2 equiv) in 1 mL of TEA was added dropwise over 10 min. The reaction flask was flushed with argon and the mixture was stirred at the indicated temperature for the indicated time (Table 2). After the reaction was over, the resulting solution was filtered, washed with brine, and extracted with EtOAc (2 × 10 mL). The combined extracts were dried over MgSO4 and concentrated under vacuum to yield the crude product. Purification was performed by flash chromatography.

2-[(2-(Methylselenyl)phenyl)ethynyl]thioanisole (9)

The product was obtained as a white solid: mp 105–107 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 2.37 (s, 3H), 2.52 (s, 3H), 7.10–7.19 (m, 3H), 7.24–7.33 (m, 3H), 7.54 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.5, 15.5, 92.6, 94.2, 121.4, 123.7, 124.3, 124.4, 125.3, 127.5, 129.10, 129.11, 132.77, 132.81, 136.5, 141.8; IR (in CH2Cl2, cm−1) 3053, 2986, 2305, 1266; HRMS Calcd for C16H14SSe: 317.99814. Found: 317.99874.

General procedure for iodocyclization

To a solution of 0.25 mmol of the diarylalkyne in 3 mL of CH2Cl2 was added gradually the I2/ICl solution (amounts as indicated in Table 3) in 2 mL of CH2Cl2. The reaction mixture was flushed with argon and allowed to stir at 25 °C for the indicated time (the reaction was monitored by TLC for completion). The excess I2 or ICl was removed by washing with satd aq Na2S2O3. The mixture was then extracted by EtOAc or diethyl ether (2 ×10 mL). The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous MgSO4 and concentrated under vacuum to yield the crude product, which was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel with ethyl acetate/hexanes as the eluent.

[2-(3-Iodobenzo[b]selenophen-2-yl]thioanisole (27)

The product was obtained as a white solid: mp 116–118 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 2.43 (s, 3H), 7.24–7.38 (m, 4H), 7.42–7.50 (m, 2H), 7.85–7.90 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 16.0, 87.2, 124.7, 125.2, 125.6, 125.9, 126.1, 128.8, 129.8, 131.0, 135.6, 139.3, 141.4, 142.9, 143.1; IR (in CH2Cl2, cm−1) 3054, 2986, 2925, 1264; HRMS Calcd for C15H11ISSe: 429.87914. Found: 429.88004.

General procedure for the PhSeCl cyclizations

To a solution of 0.25 mmol of the diarylalkyne in CH2Cl2 (3 mL) was added the PhSeCl (amount as indicated in Table 3) dissolved in 2 mL of CH2Cl2. The mixture was flushed with argon and allowed to stir at 25 °C for the indicated time. The reaction mixture was washed with 20 mL of water and extracted with EtOAc or diethyl ether. The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous MgSO4 and concentrated under vacuum to yield the crude product, which was further purified by flash chromatography on silica gel with ethyl acetate/hexanes as the eluent.

Methyl 2-[3-(phenylselenyl)benzo[b]thiophen-2-yl]benzoate (32)

The product was obtained as a yellow gel: 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.59 (s, 3H), 7.07–7.12 (m, 5H), 7.36–7.39 (m, 3H), 7.48–7.53 (m, 2H), 7.80–7.87 (m, 2H), 7.97–8.00 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 52.3, 118.0, 122.3, 125.0, 125.16, 125.19, 126.2, 129.07, 129.11, 130.0, 130.05, 131.5, 131.8, 132.2, 132.8, 135.2, 139.7, 141.1, 147.9, 167.2; IR (in CH2Cl2, cm−1) 3055, 2987, 1727, 1263; HRMS Calcd for C22H16O2SSe: 424.00362. Found: 424.00442.

Supplementary Material

General experimental procedures and spectral data for all previously unreported starting materials and products. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (GM070620 and GM079593) and the National Institutes of Health Kansas University Center of Excellence for Chemical Methodologies and Library Development (P50 GM069663) for support of this research. Thanks are also extended to Johnson Matthey, Inc. and Kawaken Fine Chemicals Co. for donating the palladium catalysts, Dr. Feng Shi and Dr. Yu Chen for useful discussions, and Dr. Tanay Kesharwani for providing the diarylalkyne 9.

References

- 1.For a review, see: Larock RC. Chapter 2 Acetylene Chemistry. In: Diederich F, Stang PJ, Tykwinski RR, editors. Chemistry, Biology, and Material Science. New York: Wiley-VCH; 2005. pp. 51–99.

- 2.For a review, see: Larock RC. Top. Organomet. Chem. 2005;14:147. Korivi RP, Cheng C-H. Org. Lett. 2005;7:5179. doi: 10.1021/ol0519994. Skouta R, Li C-J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:1117. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603495. Heller ST, Natarajan SR. Org. Lett. 2007;7:4947. doi: 10.1021/ol701784w.

- 3.(a) Arcadi A, Cacchi S, Fabrizi G, Marinelli F, Moro L. Synlett. 1999:1432. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yue D, Yao T, Larock RC. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:10292. doi: 10.1021/jo051299c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yue D, Yao T, Larock RC. J.Comb. Chem. 2005;7:809. doi: 10.1021/cc050062r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Sniady A, Wheeler KA, Dembinski R. Org. Lett. 2005;7:1769. doi: 10.1021/ol050372i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yao T, Zhang X, Larock RC. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:7679. doi: 10.1021/jo0510585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Liu Y, Zhou S. Org. Lett. 2005;7:4609. doi: 10.1021/ol051659i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Yao T, Zhang X, Larock RC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:11164. doi: 10.1021/ja0466964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Bew SP, El-Taeb GMM, Jones S, Knight DW, Tan W. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007:5759. [Google Scholar]; (f) Arimitsu S, Jacobsen JM, Hammond GB. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:2886. doi: 10.1021/jo800088y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Huang X, Fu W, Miao M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:2359. [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Larock RC, Yue D. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:6011. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yue D, Larock RC. J. Org.Chem. 2002;67:1905. doi: 10.1021/jo011016q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hessian KO, Flynn BL. Org. Lett. 2003;5:4377. doi: 10.1021/ol035663a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flynn BL, Flynn GP, Hamel E, Jung MK. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001;11:2341. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00436-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Worlikar SA, Kesharwani T, Yao T, Larock RC. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:1347. doi: 10.1021/jo062234s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Kesharwani T, Worlikar SA, Larock RC. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:2307. doi: 10.1021/jo0524268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bui CT, Flynn BL. J. Comb. Chem. 2006;8:163. doi: 10.1021/cc050066w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alves D, Luchese C, Nogueira CW, Zeni G. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:6726. doi: 10.1021/jo070835t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang X, Sarkar S, Larock RC. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:236. doi: 10.1021/jo051948k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Yue D, Larock RC. Org. Lett. 2004;6:1037. doi: 10.1021/ol0498996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Amjad M, Knight DW. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:539. [Google Scholar]; (c) Barluenga J, Trincado M, Rubio E, GonzáLez JM. Angew. Chem.,Int. Ed. 2003;42:2406. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Yue D, Yao T, Larock RC. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:62. doi: 10.1021/jo051549p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang X, Campo MA, Yao T, Larock RC. Org. Lett. 2005;7:763. doi: 10.1021/ol0476218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Huang Q, Hunter JA, Larock RC. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:3437. doi: 10.1021/jo020020e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fischer D, Tomeba H, Pahadi NK, Patil NT, Yamamoto Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:4764. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yao T, Larock RC. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:5936. doi: 10.1021/jo034308v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Barluenga J, Vázquez-Villa H, Ballesteros A, González JM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:9028. doi: 10.1021/ja0355372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yue D, Della Cá N, Larock RC. Org. Lett. 2004;6:1581. doi: 10.1021/ol049690s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yue D, Della Cá N, Larock RC. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:3381. doi: 10.1021/jo0524573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yao T, Larock RC. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:1432. doi: 10.1021/jo048007c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barluenga J, Vázquez-Villa H, Ballesteros A, González JM. Org. Lett. 2003;5:4121. doi: 10.1021/ol035691t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Yao T, Campo MA, Larock RC. Org. Lett. 2004;6:2677. doi: 10.1021/ol049161o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yao T, Campo MA, Larock RC. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:3511. doi: 10.1021/jo050104y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Waldo JP, Larock RC. Org. Lett. 2005;7:5203. doi: 10.1021/ol052027z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Waldo JP, Larock RC. J. Org.Chem. 2007;72:9643. doi: 10.1021/jo701942e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Zhou C, Dubrovskiy AV, Larock RC. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:1626. doi: 10.1021/jo0523722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Likhar PR, Subhas MS, Roy M, Roy S, Lakshmi Kantam M. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2008;91:259. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ren X-F, Konaklieva MI, Shi H, Dickey S, Lim DV, Gonzalez J, Turos E. J. Org.Chem. 1998;63:8898. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marshall JA, Yanik MM. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:3798. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knight DW, Redfern AL, Gilmore J. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1998:2207. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arcadi A, Cacchi S, Di Giuseppe S, Fabrizi G, Marinelli F. Org Lett. 2002;4:2409. doi: 10.1021/ol0261581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.(a) Zhang X, Larock RC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:12230. doi: 10.1021/ja053079m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tang B-X, Tang D-J, Yu Q-F, Zhang Y-H, Liang Y, Zhong P, Li J-H. Org. Lett. 2008;10:1063. doi: 10.1021/ol703050z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yao T, Yue D, Larock RC. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:9985. doi: 10.1021/jo0517038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.(a) Crone B, Kirsch SF. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:5435. doi: 10.1021/jo070695n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Just ZW, Larock RC. J. Org.Chem. 2008;73:2662. doi: 10.1021/jo702666j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barange DK, Batchu VR, Gorja D, Pattabiraman VR, Tatini LK, Babu JM, Pal M. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:1775. [Google Scholar]

- 29.For other miscellaneous examples, see Hessian KO, Flynn BL. Org. Lett. 2006;8:243. doi: 10.1021/ol052518j. Barluenga J, Vázquez-Villa H, Merino I, Ballesteros A, González JM. Chem. Eur. J. 2006;12:5790. doi: 10.1002/chem.200501505. Bi H-P, Guo L-N, Duan X-H, Gou F-R, Huang S-H, Liu X-Y, Liang Y-M. Org. Lett. 2007;9:397. doi: 10.1021/ol062683e. Barluenga J, Palomas D, Rubio E, GonzáLez JM. Org. Lett. 2007;9:2823. doi: 10.1021/ol0710459. Tellitu I, Serna S, Herrero T, Moreno I, Domínguez E, SanMartin R. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:1526. doi: 10.1021/jo062320s. Appel TR, Yehia NAM, Baumeister U, Hartung H, Kluge R, Ströhl D, Fanghänel E. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2003:47.

- 30.(a) Sonogashira K. Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions. In: Diederich F, Stang P, editors. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH; 1998. pp. 203–229. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sonogashira K, Tohda Y, Hagihara N. Tetrahedron Lett. 1975;16:4467. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campo MA, Larock RC. Org. Lett. 2000;2:3675. doi: 10.1021/ol006585j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith MB, March J, editors. Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure. New York: Wiley-VCH; 2001. Chapter 10 March’s Advanced Organic Chemistry; pp. 438–445. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Theoretical analysis (e.g. MO calculations) can be used to further understand/quantitate the "polarization" effects of the substituents affecting the nature of the cationic intermediate. However, in this manuscript the polarization effects are discussed purely qualitatively in terms of resonance contributions

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

General experimental procedures and spectral data for all previously unreported starting materials and products. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.