Abstract

We hypothesize that neurons have protective mechanisms against adverse local conditions that improve the chances of cell survival. In the present study, we find that growth arrest and DNA damage protein 45b (Gadd45b), a previously unknown molecule in neurons of any type, is neuroprotective in retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) in the retina. Gadd45b is upregulated in RGCs in response to oxidative stress, aging and elevated intraocular pressure. Using Gadd45b siRNA, we show that Gadd45b protects RGCs from dying against different neuronal injuries including oxidative stress, TNFα cytotoxicity, and glutamate excitotoxicity in vitro. Using Gadd45b knockout mice, we find that Gadd45b protects RGCs from dying against oxidative stress in vivo. Our data suggest that Gadd45b is an important component of the intrinsic neuroprotective mechanisms of RGC neurons in the retina and, perhaps in the CNS as well.

Keywords: Gadd45b, neuroprotection, neurodegeneration, aging, TNFα, excitotoxicity, glaucoma, oxidative stress

Introduction

The intrinsic mechanisms that neurons use to protect themselves from stresses, injuries and age are largely unknown. To date, much of the research on neuroprotection has been aimed at developing extrinsic therapeutic strategies to limit injuries to neurons for the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders and neuronal aging. There have been few studies that are aimed at exploring intrinsic neuroprotective strategies that increase the resistance of neurons to injuries. Studies on the intrinsic neuroprotective mechanisms of neurons may provide effective therapies for neuroprotection in the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders and neuronal aging.

Long projecting neurons, such as hippocampal and cortical pyramidal ganglions in Alzheimer’s disease, are vulnerable to aging and neurodegenerations (Mattson and Magnus, 2006). Retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) are typical long projecting neurons and, like other long projecting neurons in the central nervous system, RGCs are selectively lost in aging (Neufeld and Gachie, 2003) and in neurodegenerative diseases. Glaucoma, the second leading cause of irreversible blindness in developed countries (Kerrigan et al., 1997; Quigley et al., 1995), is characterized by neurodegeneration of RGCs. We have used RGCs as a model to demonstrate a previously unknown neuronal, intrinsic, neuroprotective mechanism that may protect neurons in neurodegenerative diseases and aging.

Growth arrest and DNA damage inducible protein 45b (Gadd45b) is a member of the Gadd45 family of small (18kDa) evolutionarily conserved proteins. Several observations on non-neuronal cells consistently suggested Gadd45b as an anti-apoptosis gene. Gadd45b protein protects hematopoietic cells from ultraviolet radiation induced genotoxic stress, cytokines and anti-cancer drug induced apoptosis (Gupta et al., 2006a;Zazzeroni et al., 2003;Gupta et al., 2006b). The function of Gadd45b in neurons was not clear.

In the present study, we find that Gadd45b protects RGCs from different neuronal injuries, including oxidative stress, TNFα cytotoxicity, and glutamate excitotoxicity. The expression of Gadd45b appears to be upregulated in RGCs in vivo in response to aging, elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) and oxidative stress. Future studies on potentiating the neuroprotective function of Gadd45b in neurons may lead to therapeutic approaches for treatment of neurodegenerative diseases.

Materials and Methods

Animal models

Aging: C57BL/6 male mice, 25 months of age (old), compared to 5 months of age (young). Chronic glaucoma rat model: Chronic, moderately elevated IOP was produced unilaterally in 10 Wistar albino male rats, 3 months of age (200–250g), by cautery of three episcleral vessels as described previously (Liu et al., 2006). The contralateral eye served as the comparative control. The IOP was measured immediately and documented every week. Rats were sacrificed at one month after the surgery. Systemic oxidative stress model: Paraquat was intraperitoneally injected into C57BL/6 male mice, 5 months of age, at a dose of 10 mg/kg (nis-Oliveira et al., 2007). Mice were sacrificed at 3 days after treatment. Retina oxidative stress model: Three months old, age-matched, male wild type and Gadd45b knockout mice from four different litters were used. Pparaquat was diluted in normal saline (0.9% sodium chloride) to a concentration of 0.05 to 0.25 μg/μl. Paraquat solution was unilaterally injected into the vitreous by using a microinjection needle (33 gage, Hamilton). The contralateral eyes received intravitreal injection of normal saline as comparative controls. For intravitreal injection, the microinjection needle was penetrated through sclera at the limbal region into the vitreous without injuries to the lens or retina; an anterior chamber puncture in the cornea was performed to lower intraocular pressure; 10 μl of solution was slowly injected into the vitreous to replace intraocular fluid or vitreous. Mice were sacrificed 48 hours after injection. Gadd45b transgenic mice: Generation and genotyping of Gadd45b knockout and wild type mice were as described previously (Papa et al., 2007). Gadd45b knockout mice were maintained in a mixed (BL6/129VJ) genetic background and propagated using heterozygous breeding pairs.

For all animal models and each experiment, at least 4 mice per experimental group were studied. All animals were maintained in temperature-controlled rooms on a 12 hours light/12 hours dark cycle. Experiments were carried out in accordance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmology and Visual Research.

RGC retrograde labeling and counting in retinas

As described previously (Wang et al., 2007;Liu et al., 2006), RGCs were retrograde labeled by stereotaxic injection of the fluorescent tracer Fluoro-Gold into the superior colliculi of animals at 2 days before sacrifice. This method labeled more than 95% of RGCs in the retina. Sampling the retina at 2 days after fluorogold injection does not lead to a significant build up of fluorogold in surrounding glia. The retina tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, dissected for a retinal flat mount. RGC counting were performed in four quadrants (one field per quadrant) of central retina (approximately 0.5 mm from optic nerve head) and in four quadrants (two fields per quadrant) of peripheral retina (approximately 1.5 mm from the optic nerve head) per eye at ×200 magnification with fluorescence microscopy (Olympus AX70). This method counted at least 30% of the total number of RGCs in the retina. The percentage of the RGC count in the paraquat treated retina to that in the contralateral control retina was calculated.

Immunohistochemistry

Eyes were enucleated, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin and oriented for 6 μm sagittal sections. The retina paraffin tissue sections were deparaffined, rehydrated, washed completely with 0.1M glycine-Tris solution and nonspecifically blocked by 20% donkey serum at room temperature for 30 minutes. Immunohistochemistry was performed using specific primary antibodies against Gadd45b (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc, Santa Cruz, CA; goat polyclonal, working dilution 1:200) and the Vectastain Elite ABC kit (Vector Labs, Burlingame, California), using diaminobenzidine as substrate. Hematoxylin was the counterstain. For double immunofluorescent staining, tissues were sequentially incubated with the second primary antibody Thy-1 (A&D Serotec, Oxford, UK, mouse monoclonal, working dilution 1:50) and the second appropriate secondary antibody. Fluorescent-conjugated secondary antibodies, goat anti-mouse Oregon green-conjugated IgG (1:400), goat anti-rabbit Rhodamine red-X conjugated IgG (1:1000), were used. Negative controls were performed in parallel by pre-incubation of the primary antibody at 4 °C overnight with its specific blocking peptide.

RGC-5 cell culture

RGC-5, a rat retinal ganglion cell line transformed with adenovirus carrying E1A, was cultured in DMEM media as described previously (Frassetto et al., 2006). To induce the neuronal differentiation of RGC5, cells were treated with 5 μM staurosporine for 5 minutes as described previously (Frassetto et al., 2006). To arrest cell proliferation, RGC5 cells were plated at 30% confluence in MEM media without pyruvate and glutamine and without serum for further experiments. Pharmacological agents were added to cell media at the final concentrations according to each experiment as follows: paraquat, 50 to 800 μM; TNFα, 1 to 100 ng/ml, glutamate, 1.5 to 10 mM.

SiRNA transient transfections

The siRNA oligonucleotides for Gadd45b were predesigned and synthesized by Qiagen. The following SiRNA for Gadd45b was designed to target rat Gadd45b transcript (NM 001008321). Sense: r(CGU UCU GCU GCG ACA AUG A)dTdT. Antisense: r(UCA UUG UCG CAG CAG AAC G)dAdT. RNA duplexes (20 nM) were transfected into cells using Lipofectamine™ RNAiMAX according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, RGC5 cells were plated in 24-well plates at a density of 10K to generate less than 30% confluence in MEM with 10% FBS, without antibody for 12h. The cell media was changed to 500 μl of MEM without serum and antibody per well before transfection. RNAi duplex was diluted in Opti-MEM I Reduced Serum Medium and mixed gently with Lipofectamine RNAiMAX mixture (Invitrogen) with a ratio 1:3, followed by incubation for 30 minutes at room temperature and then was added to cell culture wells. The cells were incubated in a standard cell culture incubator for 6 hours for further experiments. A red fluorescent labeled, nonspecific double-strand RNA (BLOCK-iT Alexa Fluor Red Fluorescent Oligo, Invitrogen), was transfected in parallel as a transfection and SiRNA negative control and to facilitate assessment of transfection. In parallel to each experiment, knockdown of Gadd45b mRNA was confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR. The transfection efficiency was more than 70% and the SiRNA silencing effect was more than 50%. Transfections were performed in triplicate, and all experiments were repeated three times.

RNA isolation and quantitative Real-time RT-PCR

Cells or retinal tissues in each sample were extracted for the total RNA using RNeasy Mini Kits (Qiagen Inc, Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocols (Liu etal, 2005). The DNA-free RNA was assessed for integrity by formaldehyde/agarose gel electrophoresis and quantitated by 260 nm UV light absorbance. One hundred ng of total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using a one step supertranscripte kit (Bio-Rad laboratories Inc.), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Primers are as follows: rat Gadd45b: 5′-GCTGGCCATAGACGAAGAAG-3′; 5′-AGCCTATGCATGCCTGATAC-3′; mice Gadd45b: 5′-CCTGGCCATAGACGAAGAAG-3′;5′-AGCCTCTGCATGCCTGATAC-3′. 18S: 5′-GTAACCCGTTGAACCCCATT-3′;5′-CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG-3′. The increase of fluorescence in PCR was detected in real time using the iCycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA). All quantitative RT-PCR reactions were performed in triplicate. Values were normalized to the internal control genes 18S using Bio-Rad analysis software and presented as normalized expression levels. Primers were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA).

Cell viability assay

Cell number was indicated by the cell viability detected by CellTiter AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay using tetrazolium compound, MTS (Promega, Madison, WI) following the manufacturer’s instructions. After treatments of cells, cell media was changed to MEM without phenol red. Assay was performed by adding a small amount of MTS reagent (1:5) directly to culture wells, incubating for 1 hour and then recording the absorbance of cell media at 490 nm with a 96-well plate reader (Multiskan Spectrum, ThermoFisher Scientific). In the MTS assay, the absorption is directly proportional to the number of viable cells. Data was presented as the radio of the control of each experiment at the start time point.

Results

Expression of Gadd45b in RGCs in vivo

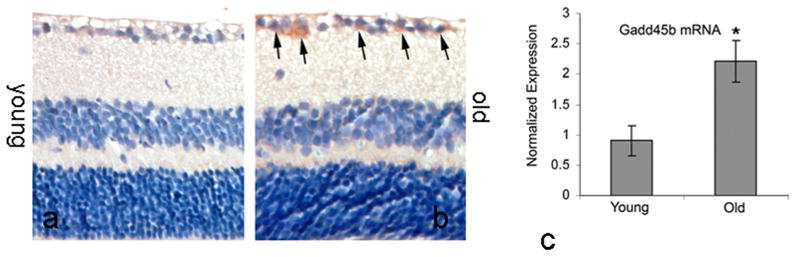

The expression of Gadd45b in neuronal tissues was not studied previously. We detected the expression of Gadd45b in retinas by using immunohistochemistry and quantitative RT-PCR. Gadd45b expression was detected in normal young and old retinas and retinas exposed to oxidative stress or elevated intraocular pressure. Immunohistochemical labeling for Gadd45b protein localized Gadd45b predominantly in the ganglion cell layer. Positive labeling for Gadd45b protein was weakly present in the ganglion cell layer in 5 months of age young mouse retinas (Figure 1a), but was markedly increased in intensity in 25 months of age old mouse retinas (Figure 1b). By using quantitative RT-PCR, the mRNA level of Gadd45b was detected in the retinas from 25 months of age old mice and 5 month of age young mice. The mRNA level of Gadd45b was significantly higher in retinas from old mice compared to young mice (Figure 1c). The immunohistochemistry observations were consistent with results from RT-PCR. These data showed that Gadd45b was expressed normally in RGCs and appeared to be upregulated in aged retinas.

Figure 1.

Expression of Gadd45b in RGCs in young (Young, 5 months old) and aged (Old, 25 months old) retinas. Immunohistochemical labeling for Gadd45b was weakly present in the retinal ganglion cell layer in normal adult young retina (a), but significantly increased in intensity in RGCs in aged retina (b). Arrows indicated the positive labeling for Gadd45b. c, quantitative RT-PCR for Gadd45b mRNA in retinas of aged mice and young adult mice. Values are mean ± SEM (n=6), *p<0.05.

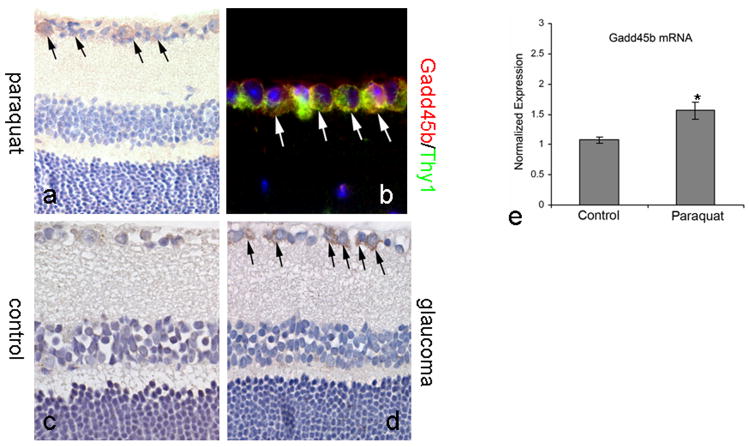

Following the exposure of the young mouse retinas to oxidative stress by systemic administration of paraquat for 3 days, the level of Gadd45b protein in the retinal ganglion cell layer appeared to be increased (Figure 2a, compare to Figure 1a). Double labeling for Gadd45b and a RGC marker (Thy-1.1) confirmed that Gadd45b was present in Thy-1.1 positive RGCs (Figure 2b). In retinas from a rat glaucoma model with chronic, moderately elevated intraocular pressure for 1 month (Figure 2c), positive labeling for Gadd45b was more intense compared to the weak labeling in retinas of contralateral control eyes (Figure 2d). In young mice, oxidative stress generated by systemic administration of paraquat caused increased level of Gadd45b mRNA in retinas (Figure 2e). Detection of the mRNA level of Gadd45b confirmed that there was significant upregulation of Gadd45b mRNA expression in retinas exposed to oxidative stress.

Figure 2.

Expression of Gadd45b in RGCs in retinas exposed to injuries. Immunohistochemical labeling for Gadd45b was intensively present in the retinal ganglion cell layer in retinas exposed to systemic injection of paraquat (a). Double immunofluorescent labeling for Gadd45b and RGC marker, Thy-1.1, showed that Gadd45b was co-localized with Thy1.1 (b) in RGCs in the retina. In the retina with elevated intraocular pressure (d), labeling for Gadd45b was more intense in RGCs than in the contralateral, control, normotensive eye (c). Arrows indicated the positive labeling for Gadd45b. e, quantitative RT-PCR for Gadd45b mRNA in retinas of adult control mice (Control, 5 months old) and age-matched mice with systemic oxidative stress by intraperitoneal injection of paraquat (Paraquat). Values are mean ± SEM (n=4), *p<0.05.

These data showed that Gadd45b was upregulated in aged retinas and in response to different neuronal injuries. The upregulation of Gadd45b in RGCs under different stress conditions suggests that Gadd45b is a stress-related intracellular molecule that appears to be commonly upregulated in RGCs in response to different neuronal injures.

Gadd45b protected RGC5 in vitro

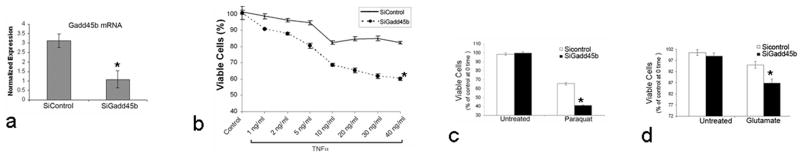

The functions of Gadd45b in neurons are unknown. In this study, we determined the function of Gadd45b in survival/death of RGCs in response to neuronal injuries. We used RGC5, a transformed rat RGC cell line that has been used broadly for studies of RGCs, to demonstrate the function of Gadd45b in survival of RGC5 in response to paraquat oxidative stress, TNFα cytotoxicity and glutamate excitotoxicity in vitro. RGC5 cells were mitotic arrested by being maintained in a serum free and low energy supply cell culture media. Gadd45b SiRNA was transfected into RGC5 to knock down Gadd45b mRNA expression to generate Gadd45b-knockdown RGC5 cells The transfection efficacy was 50–70% of cells. Transfection with Gadd45b SiRNA attenuated more than 50% of Gadd45b mRNA expression in RGC5 cells within 5 hours (Figure 3a). The neuroprotective function of Gadd45b was tested by comparing the number of viable cells between transfection control RGC5 and Gadd45b-knockdown RGC5 exposed to injuries.

Figure 3.

Gadd45b protects RGC5 from injuries. a, Gadd45b SiRNA transfection significantly decreased the Gadd45b expression in RGC5 cells detected by quantitative RT-PCR. Compared to transfection control RGC5 (SiControl), the number of viable cells was much lower in RGC5 cells transfected with Gadd45b SiRNA (SiGadd45b) after treatment with 1 to 40 ng/ml of TNFα (b). Exposed to 600 μM paraquat (c) or 2 mM glutamate (d), the number of viable cells was significantly less in SiGadd45b than Sicontrol cultures. Values are mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *p<0.05 (a, b, c, d)

TNFα induces apoptosis in neurons (Barker et al., 2001) and is believed to be neurotoxic to RGCs in the pathogenesis of glaucomatous optic neuropathy (Nakazawa et al., 2006;Yuan and Neufeld, 2000). TNFα caused loss of RGC5 cells in a dose-dependent manner. Comparing control and Gadd45b-knockdown cultures, knockdown of Gadd45b expression did not significantly change the cell survival in control conditions. Figure 3b demonstrates the sensitivity of RGC5 to TNFα. Knockdown of Gadd45b expression caused a much greater loss of RGC5 cells in response to the same doses of TNFα treatment. TNFα maximally caused about 20% loss of cells in control cultures but 40% loss in Gadd45b-knockdown cultures. These data showed that knockdown of Gadd45b expression potentiated the death of RGC5 cells in response to TNFα cytotoxicity, or conversely, the presence of Gadd45b protected RGC5 cells from death caused by TNFα cytotoxicity.

We also tested whether Gadd45b would protect RGC5 cells exposed to paraquat generated oxidative stress and glutamate excitoxicity. The dose-response of the cytotoxic effects of paraquat was determined and a dose that had mild cytotoxicity in the control RGC5 cells was chosen to challenge Gadd45b knockdown RGC5 cells. As shown in Figure 3c, 600 μM paraquat caused an approximately 30% decrease in cell viability in control RGC5 cells but a much greater decrease in cell viability (60%) in Gadd45b-knockdown RGC5. Similarly, in response to glutamate excitotoxicity, there was increased cell loss in RGC5 cells transfected with Gadd45b SiRNA, although RGC5 cells appeared to be less sensitive to glutamate excitotoxicity (Figure 3d). Taken together, these data suggest that Gadd45b protected RGC5 cells from different neuronal stresses and, therefore, may be a component of a common survival mechanism of RGC5 under different stressful conditions.

Gadd45b protected RGCs in vivo

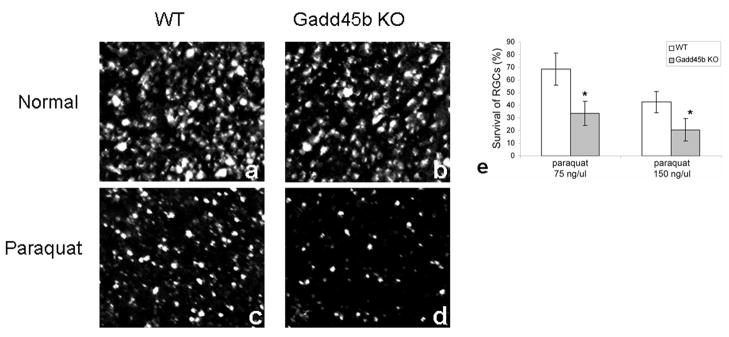

We further tested the neuroprotective activity of Gadd45b in RGCs in vivo by using Gadd45b transgenic knockout mice. The knockout of Gadd45b expression was confirmed in the retina of Gadd45b knockout mice (data not shown). There were no significant differences in morphology or RGC counts between retinas of 2 months old Gadd45b knockout mice and age-matched wild type mice (data not shown). Paraquat has been used to induce oxidative stress in a variety of tissues. Intravitreous injection of paraquat (50 to 250 ng/μl) caused damage of retinal cells in a dose dependent manner. We quantitated the damage to RGCs by retrograde labeling and RGC counting. Figure 4 represents the survival of RGCs two days after fluorogold loading and intravitreal paraquat induced oxidative stress. RGCs shown by fluorogold labeling appeared abundant in the retina of both wild type (Figure 4a) and Gadd45b knockout (Figure 4b) mice. Two days after intravitreous injection of paraquat (150 ng/μl), RGCs were lost in the wild type retina (Figure 4c); however, there was much more loss of RGCs in the Gadd45b transgenic knockout retina (Figure 4d) in response to paraquat induced oxidative stress. Statistical comparison of the number of RGCs counted throughout the retina showed that wild type retinas had significantly more surviving RGCs than Gadd45b transgenic knockout retina in response to paraquat oxidative stress (Figure 4e). These data showed that knockout of Gadd45b caused increased loss of RGCs in response to paraquat, or conversely, the presence of Gadd45b protected RGCs against paraquat induced oxidative stress in vivo.

Figure 4.

Gadd45b protected RGCs against paraquat oxidative stress in vivo. Fluoro-gold retrolabeling of RGCs showed loss of RGCs in retinas treated with intravitreous injection of paraquat 150 ng/μl (c, d) compared to control retinas treated with normal saline (a, b). However, many fewer RGCs survived in the Gadd45b knockout retina (d) than in the wild type retina (c) following paraquat injection. RGC counting showed that RGCs were lost in response to intravitreous injection of paraquat (75 ng/μl or150 ng/μl) in a dose dependent manner. However, the numbers of RGCs that survived in the Gadd45b knockout retinas were significantly less than the number of RGCs that survived in the wild type retinas in response to the same dose of paraquat (e). Values were the percentage of counted RGC number in paraquat treated retina to contralateral control retina and presented as mean ± SEM, *p<0.05, n=5.

Discussion

Our studies have revealed a previously unknown, intrinsic, neuroprotective molecule Gadd45b in RGCs. This neuroprotective protein appears to be a common mechanism by which RGCs protect themselves from different neuronal stresses and injuries, and perhaps aging. The Gadd45b neuroprotective mechanism may exist in other neurons in the central nervous system. Studies on enhancing the Gadd45b neuroprotective function may provide effective therapeutic strategies for preventing death of RGCs or other neurons during aging and in neurodegenerative diseases.

The Gadd45 family of genes, originally termed Gadd45, MyD118 and CR6 and now referred to as Gadd45a, Gadd45b and Gadd45g respectively, has been implicated as stress sensors to physiological or environmental conditions (Liebermann and Hoffman, 2007). Gadd45a, was demonstrated in NMDA mediated retinal cell death (Laabich et al., 2001) and neuronal injuries (Uberti et al., 2002;Befort et al., 2003) as a pro-apoptosis gene. Of the Gadd45 family members, Gadd45b has been implicated as an anti-apoptosis factor. Our data show that Gadd45b is upregulated in RGCs of eyes with chronic elevated intraocular pressure or oxidative stress. During normal aging, Gadd45b is upregulated in RGCs, perhaps due to oxidative stress associated with aging. Gadd45b appears to be a stress sensor in RGCs to different neuronal stress conditions.

Although the effect of Gadd45b on cell cycle and cell survival/apoptosis has been studied in several different cell types (Gupta et al., 2006a;Yoo et al., 2003), the presence and the function of Gadd45b in neuron were not clear. Gadd45b is expressed in hippocampus tissues by the regulation of cAMP responsive element binding protein in response to cocaine stimulation (Lemberger et al., 2008). Our studies demonstrating that Gadd45b protects RGCs from death in response to different neuronal injuries, are consistent with the results from studies on hematocytes, which showed that Gadd45b protected these cells from ultraviolet radiation induced genotoxic stress, cytokines and anti-cancer drug induced apoptosis (Gupta et al., 2006a;Zazzeroni et al., 2003;Gupta et al., 2006b). In addition, Gadd45b promoted hepatocyte survival during liver regeneration (Papa et al., 2008). Our findings and those on non-neuronal cells identify Gadd45b as a molecule that promotes the survival of cells under stress conditions.

The intracellular mechanisms by which Gadd45b protects neurons such as RGCs need to be further studied. In non-neuronal cells, Gadd45b interacts with regulatory factors and signaling pathways to control the cell cycle, DNA repair and cell survival/apoptosis. Generally, activation of JNK is associated with induction of apoptosis (Papa et al., 2004). Gadd45b completes NFκB-mediated anti-apoptosis effects by inhibition of JNK activity in TNFα induced apoptosis in fibroblast cells (De et al., 2001). Gadd45b inhibits JNK through inactivating MKK7 directly by binding to crucial sites in the catalytic pocket, including the ATP binding site Lys149 (Papa et al., 2007). Gadd45b deficient cells have enhanced activation of caspase-3 and PARP cleavage and decreased expression of CIAP-1, Bcl-2, and Bcl-xL which are anti-apoptosis molecules (Liebermann and Hoffman, 2007). In addition, Gadd45 proteins interact with several important cellular regulators, such as p21 and PCNA (Vairapandi et al., 1996), to control cell cycle and to control DNA demethylase activity in DNA repair (Vairapandi, 2004). All of these intracellular mechanisms are consistent with a survival function for Gadd45b. The molecular mechanisms by which Gadd45b protects neurons in neurons should be further studied.

Further studies on enhancing the intrinsic neuroprotective function of Gadd45b may provide effective therapeutic approaches for preventing RGC death in the aging retina and in neurodegenerative diseases, such as glaucoma. For example, there may be extrinsic signaling factors that induce the upregulation of Gadd45b in times of stress. Strategies to upregulate Gadd45b may also be applicable to other types of vulnerable neurons in aging and other neurodegenerative disorders in the CNS.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH grant EY12017, a generous gift from the Forsythe Foundation, an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, NIH grants CA084040 and CA098583.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- Barker V, Middleton G, Davey F, Davies AM. TNFalpha contributes to the death of NGF-dependent neurons during development. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1194–1198. doi: 10.1038/nn755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Befort K, Karchewski L, Lanoue C, Woolf CJ. Selective up-regulation of the growth arrest DNA damage-inducible gene Gadd45 alpha in sensory and motor neurons after peripheral nerve injury. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:911–922. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De SE, Zazzeroni F, Papa S, Nguyen DU, Jin R, Jones J, Cong R, Franzoso G. Induction of gadd45beta by NF-kappaB downregulates pro-apoptotic JNK signalling. Nature. 2001;414:308–313. doi: 10.1038/35104560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frassetto LJ, Schlieve CR, Lieven CJ, Utter AA, Jones MV, Agarwal N, Levin LA. Kinase-dependent differentiation of a retinal ganglion cell precursor. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:427–438. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta M, Gupta SK, Hoffman B, Liebermann DA. Gadd45a and Gadd45b protect hematopoietic cells from UV-induced apoptosis via distinct signaling pathways, including p38 activation and JNK inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2006a;281:17552–17558. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600950200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta SK, Gupta M, Hoffman B, Liebermann DA. Hematopoietic cells from gadd45a-deficient and gadd45b-deficient mice exhibit impaired stress responses to acute stimulation with cytokines, myeloablation and inflammation. Oncogene. 2006b;25:5537–5546. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrigan LA, Zack DJ, Quigley HA, Smith SD, Pease ME. TUNEL-positive ganglion cells in human primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115:1031–1035. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100160201010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laabich A, Li G, Cooper NG. Characterization of apoptosis-genes associated with NMDA mediated cell death in the adult rat retina. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2001;91:34–42. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00116-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemberger T, Parkitna JR, Chai M, Schutz G, Engblom D. CREB has a context-dependent role in activity-regulated transcription and maintains neuronal cholesterol homeostasis. FASEB J. 2008;22:2872–2879. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-107888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebermann DA, Hoffman B. Gadd45 in the response of hematopoietic cells to genotoxic stress. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2007;39:344–347. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Chen H, Johns TG, Neufeld AH. Epidermal growth factor receptor activation: an upstream signal for transition of quiescent astrocytes into reactive astrocytes after neural injury. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7532–7540. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1004-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP, Magnus T. Ageing and neuronal vulnerability. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:278–294. doi: 10.1038/nrn1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa T, Nakazawa C, Matsubara A, Noda K, Hisatomi T, She H, Michaud N, Hafezi-Moghadam A, Miller JW, Benowitz LI. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha mediates oligodendrocyte death and delayed retinal ganglion cell loss in a mouse model of glaucoma. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12633–12641. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2801-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld AH, Gachie EN. The inherent, age-dependent loss of retinal ganglion cells is related to the lifespan of the species. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:167–172. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- nis-Oliveira RJ, Sousa C, Remiao F, Duarte JA, Ferreira R, Sanchez NA, Bastos ML, Carvalho F. Sodium salicylate prevents paraquat-induced apoptosis in the rat lung. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:48–61. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa S, Monti SM, Vitale RM, Bubici C, Jayawardena S, Alvarez K, De SE, Dathan N, Pedone C, Ruvo M, Franzoso G. Insights into the structural basis of the GADD45beta-mediated inactivation of the JNK kinase, MKK7/JNKK2. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:19029–19041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703112200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa S, Zazzeroni F, Fu YX, Bubici C, Alvarez K, Dean K, Christiansen PA, Anders RA, Franzoso G. Gadd45beta promotes hepatocyte survival during liver regeneration in mice by modulating JNK signaling. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1911–1923. doi: 10.1172/JCI33913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa S, Zazzeroni F, Pham CG, Bubici C, Franzoso G. Linking JNK signaling to NF-kappaB: a key to survival. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5197–5208. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley HA, Nickells RW, Kerrigan LA, Pease ME, Thibault DJ, Zack DJ. Retinal ganglion cell death in experimental glaucoma and after axotomy occurs by apoptosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:774–786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uberti D, Meli E, Memo M. Expression of cell-cycle-related proteins and excitoxicity. Amino Acids. 2002;23:27–30. doi: 10.1007/s00726-001-0105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vairapandi M. Characterization of DNA demethylation in normal and cancerous cell lines and the regulatory role of cell cycle proteins in human DNA demethylase activity. J Cell Biochem. 2004;91:572–583. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vairapandi M, Balliet AG, Fornace AJ, Jr, Hoffman B, Liebermann DA. The differentiation primary response gene MyD118, related to GADD45, encodes for a nuclear protein which interacts with PCNA and p21WAF1/CIP1. Oncogene. 1996;12:2579–2594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang AL, Yuan M, Neufeld AH. Age-related changes in neuronal susceptibility to damage: comparison of the retinal ganglion cells of young and old mice before and after optic nerve crush. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1097:64–66. doi: 10.1196/annals.1379.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo J, Ghiassi M, Jirmanova L, Balliet AG, Hoffman B, Fornace AJ, Jr, Liebermann DA, Bottinger EP, Roberts AB. Transforming growth factor-beta-induced apoptosis is mediated by Smad-dependent expression of GADD45b through p38 activation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:43001–43007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307869200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan L, Neufeld AH. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha: a potentially neurodestructive cytokine produced by glia in the human glaucomatous optic nerve head. Glia. 2000;32:42–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zazzeroni F, Papa S, geciras-Schimnich A, Alvarez K, Melis T, Bubici C, Majewski N, Hay N, De SE, Peter ME, Franzoso G. Gadd45 beta mediates the protective effects of CD40 costimulation against Fas-induced apoptosis. Blood. 2003;102:3270–3279. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]