Abstract

To establish a direct method to monitor substrate binding in cytochrome P450eryF applicable at elevated hydrostatic pressures we introduce a laser dye Fluorol-7GA (F7GA) as a novel fluorescent ligand. The high intensity of fluorescence and reasonable resolution of the excitation band from the absorbance bands of P450 allowed us to establish highly sensitive binding assays compatible with pressure perturbation. The interactions of F7GA with P450eryF cause an ample spin shift revealing cooperative binding (S50 = 8.2 ± 1.3 µM, n = 2.3 ± 0.1). Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) experiments suggest the presence of at least two substrate binding sites with apparent KD values in the ranges of 0.1 – 0.3 and 6 – 9 µM. Similar to earlier observations with CYP3A4, increasing hydrostatic pressure does not cause either a complete dissociation of the substrate complexes or a displacement of the spin equilibrium towards the low-spin state. Rather, increased pressure enhances the cooperativity of the F7GA-induced spin shift, so that the Hill coefficient approaches 3 at 2 kbar. Lifetime FRET experiments revealed an important increase in the affinity of the enzyme for F7GA at elevated pressures, suggesting that the binding of the ligand induces a conformational transition associated with an important increase in protein hydration. This transition largely attenuates the solvent accessibility of the heme pocket and causes an unusual stability of the high-spin, substrate-bound enzyme at elevated pressures.

Homo- and heterotropic cooperativity have emerged as important properties of a number of cytochromes P450, including human 3A4, 2C9, 1A2, 2D6, and 2B6 (see (1) for review). The most prominent cooperative behavior is exemplified by P450 3A4, the predominant drug-metabolizing cytochrome P450 in human liver. Despite extensive studies, a through understanding of P450 cooperativity mechanisms remains elusive. The initial hypothesis was based on the presumption that cytochromes P450 exhibiting cooperativity accommodate multiple substrate molecules in one large binding pocket. A loose fit of a substrate molecule requires the binding of a second ligand for efficient catalysis (2, 3). Soon after these initial publications set the stage for rigorous studies of P450 cooperativity, the first X-ray structures showing two substrate molecules in a P450 binding pocket were reported by Cupp-Vickery and co-authors (4). This work was done on cytochrome P450eryF, an enzyme from the actinomycete bacterium Saccaropolyspora erthrea that is involved in biosynthesis of the macrolide antibiotic erythromycin. The fact that two molecules of androstenedione or 9-aminophenanthrene bind in the cavity normally occupied by the natural substrate 6-deoxyerythronolide B prompted the authors to postulate that cooperativity in P450 involves no “major conformational changes” (4).

This seminal publication encouraged us (5–8) and others (9) to use the water soluble and monomeric P450eryF as a model of P450 cooperativity. This approach avoids some of the complications inherent in studies of membranous cytochromes P450 from eukaryotes. However, our studies on the effect of ionic strength in P450eryF and its mutants (5, 6) showed that the cooperativity is associated with a conformational transition in the enzyme and therefore represents a case of classical allostery. In particular, binding of the first substrate molecule was found to induce a transition that apparently involves dissociation or rearrangement of a charge-pairing bundle among helices C, D, E and G. This conformational change was assumed to be essential for the substrate-induced spin shift and cooperativity in the P450eryF (5). The possibility that P450 cooperativity is associated with effector-induced conformational transition and may involve an effector binding site located remotely from the substrate binding pocket (10, 11) has been discussed extensively (1, 12–14). Important support for these more dynamic models of P450 cooperativity derives from the profound conformational mobility suggested by recent X-ray crystal structures of mammalian cytochromes P450 (11, 15–17). In particular, the structure of ketoconazole-bound CYP3A4 revealed two ligand molecules in the active site and demonstrated impressive conformational changes caused by ligand binding (16). Our studies on the effect of substrates on the pressure-induced P450→P420 transition (18) and spin shift (19), as well as the kinetics of dithionite-dependent reduction (5) in CYP3A4 also suggest a crucial role of allosteric transitions in P450 cooperativity. Moreover, site-directed incorporation of a fluorescent probe into a cysteine-depleted mutant of CYP3A4 revealed an additional α-naphthoflavone (ANF) binding site. ANF binding at this new site, which is distinct from the two involved in the ANF-induced spin shift, affects the conformation in the vicinity of α-helix A (13). The concept of P450 cooperativity has thus progressed from a static model with multiple binding sites to more dynamic schemes suggesting effector-induced conformational transitions.

Involvement of large scale conformational changes in the mechanisms of ligand binding in cytochromes P450 emphasizes the importance of the dynamics of protein-bound water. Changes in hydration of protein cavities, solvation of hydrophobic patches on the protein surface, and dynamics of hydrogen-bonding networks in the protein interior and around the protein molecule play a crucial role in the conformational dynamics. Initial interest in hydration of the active site focused on the role of water as the replaceable 6th ligand of the P450 heme iron (20, 21), the dissociation of which is promoted by substrate binding (22). The degree of hydration of the heme pocket is known to be pivotal in determining the degree of coupling and efficiency of P450 catalysis (23).

Due to such functional importance, dynamics of protein-bound water in P450 has attracted continuous attention (23–29). This interest triggered extensive use of elevated hydrostatic and osmotic pressures as tools to explore changes in protein hydration in ligand binding and protein-protein interactions (18, 19, 25, 27, 30–36). Elevated hydrostatic pressure induces a displacement of the spin equilibrium in cytochromes P450 towards the low spin state (25, 27, 30, 32–34). A second barotropic process, which usually takes place at higher pressuires (>2000 bar), was identified as the conversion of the P450 into the inactive P420 state (33, 37, 38).

Pressure-induced changes in the content of high spin P450 in the presence of substrates reflect both the dissociation of the enzyme-substrate complex and the changes in the spin equilibrium of either substrate-free or substrate-bound enzyme. Advanced methods of spectral analysis allowed us to resolve the standard volume changes associated with each of these processes in P450cam, P450 BM3, and CYP2B4 (25, 33). The substrate-free states of all three heme proteins exhibited a volume change in the low-to-high spin transition (ΔV°spin = +21 - +23 mL/mol) consistent with expulsion of one water molecule per molecule of enzyme. However, the ΔV°spin of the substrate-bound P450cam, P450 BM3, and CYP2B4 revealed important differences among these enzymes. While in P450 BM3 the value of ΔV°spin is unaltered by substrate binding, CYP2B4 and P450cam showed a considerable increase in ΔV°spin upon formation of the substrate complex. The enzymes also exhibited differences in the volume changes of the dissociation of the substrate complexes. Consistent with the initial assumptions (30, 32), increasing hydrostatic pressure caused a dissociation of the complexes of P450cam and P450 BM3. In contrast, formation of the complex of CYP2B4 with benzphetamine was slightly promoted by pressure (ΔV°diss = 8.1 mL/mol). This unexpected effect of pressure in the microsomal heme protein may reflect substrate-induced conformational changes associated with increase in the protein hydration. Our recent studies with CYP3A4 (19) also showed that increase in hydrostatic pressure does not cause dissociation of the substrate complexes. Moreover, these studies revealed a pressure-sensitive equilibrium between two states, designated R- and P-conformers for “relaxed” and “pressure promoted” states, respectively. In contrast to other P450 enzymes, the complexes with allosteric ligands reveal neither pressure-induced substrate dissociation nor a displacement of the spin equilibrium in the pressure-promoted state of the enzyme. We hypothesize therefore that the allosteric ligands of CYP3A4 displace a system of conformational equilibria towards the state(s) with decreased solvent accessibility of the active site. Due to this transition, the water flux into the heme pocket becomes impeded, and the high-spin state of the heme iron is stabilized. Importantly, displacement of the above conformational equilibrium with hydrostatic pressure was associated with an important increase in the cooperativity in CYP3A4 interactions with 1-pyrenebutanol (1-PB) and testosterone. These results suggest that allostery in CYP3A4 involves a major ligand-induced transition, which is associated with an important change in protein hydration.

To further unravel the mechanisms of substrate-induced changes in P450 hydration it is essential to implement a direct method to monitor substrate binding, which would be applicable at elevated hydrostatic pressures. To establish such an approach we screened a series of potential fluorescent substrates and identified a laser dye Fluorol-7GA (F7GA) as an allosteric ligand with a high affinity to both P450eryF and CYP3A4. The high intensity of fluorescence and reasonable resolution of the excitation band of F7GA from the absorbance bands of P450 allowed us to establish highly sensitive substrate binding assays applicable at elevated hydrostatic pressures. The approach used to study F7GA binding is based on monitoring of FRET from F7GA to the P450 heme. In addition, application of FRET detection by time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy (TRFS) allowed us to avoid complexity in the interpretation of pressure-induced changes in the intensity of fluorescence. These complications often arise from the changes in the interactions of the free dye with solvent and/or modulation of the formation of excimers, as in the case of pyrene derivatives. The combination of pressure perturbation with TRFS is widely used to study the conformational dynamics of proteins by monitoring the changes in fluorescence lifetime of tryptophan residues or covalently-attached fluorescent probes (see (39) for review). However, this study of F7GA binding to P450eryF represents the first example of application of TRFS to study the effect of pressure on a ligand binding equilibrium.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

Fluorol F7GA (also known as Fluorol-555) was the product of Exciton (Dayton, OH). Hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPCD) was obtained from Sigma Chemicals (St. Louis, MO). All other chemicals were of ACS grade and used without further purification.

Protein expression and purification

P450eryF was expressed in E. coli, and purified on a metal-affinity column as described (40). Protein was stored at −80 °C in 0.1 M Na-Hepes buffer, pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 1mM DTT containing 10% glycerol.

Experimental setup

Conditions of the titration and pressure-perturbation experiments

were as follows: 0.1 M Na-Hepes, pH 7.4, containing 1mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT and 0.6 mg/ml HPCD. Ambient pressure measurements were performed with continuous stirring. All experiments were done at 25 °C with a use of a refrigerated water circulating bath. We used an 8 – 15 mM stock solution of F7GA in acetone. The concentration of F7GA in acetone solutions was determined by the absorbance at 440 nm using the extinction coefficient of 14.1 mM−1cm−1 (41).

Absorbance spectra

were recorded with a MC2000-2 CCD rapid scanning spectrometer (Ocean Optics Inc., Dunedin, FL). In the experiments at ambient pressure this instrument was equipped with a custom-made thermostated cell chamber with a magnetic stirrer and a L7893 UV–Vis fiber optics light source (Hamamatsu Photonics K.K., Japan).

Pressure-perturbation studies

were performed using a custom-built high-pressure optical cell (31) connected to a manual pressure generator (High Pressure Equipment, Erie, PA) capable of generating a pressure of up to 6000 bar. In these studies we used a custom-made light source using an OSRAM 64614 UV-enhanced tungsten halogen lamp (OSRAM, Germany). Both the ambient pressure cell chamber and the high-pressure optical cell were connected to the spectrometer with a 100 nm-core optical fiber (Ocean Optics Inc.). The light source connection was made with a 3 mm-core liquid light guide (Newport Inc., Stratford, CT). The control of the spectrometer and data acquisition were performed with a custom-made software written in Borland Delphi 7 from Borland Corporation (Scotts Valley, CA) and Win32Forth Public Domain Forth interpreter (www.win32forth.org) using a High-Speed Driver Library (HDL) from Ocean Optics, Inc.

Time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy (TRFS)

studies were performed in a 100 El 10×2 mm ultra-micro fluorescence cell (Hellma GmbH & Co. KG, Müllheim, Germany, Product #105.250) with a FLS 920 time-resolved fluorescence spectrometer from Edinburgh Instruments (Edinburgh, UK). The spectrometer was equipped with a PDL 800-D pulsed diode laser driver and a LDH405 pulsed diode laser head from Picoquant GmbH (Berlin, Germany) as a light source. Fluorescence excitation was performed at 405 nm and fluorescence decay curves were monitored at 545 nm with a 100 ns time span. In the case of titration-by-dilution experiments the amplitude of the decay traces was corrected for the internal filter effect. For this purpose we normalized all the decay traces to the corresponding transmittance calculated for a 5-mm light path (assuming that the source of fluorescence is located in the center of a 10-mm fluorescence cell). The transmittance values were calculated using the concentrations and extinction coefficients of F7GA and P450eryF at 405 nm. Since this wavelength is very close to the isosbestic point between the spectra of high- and low-spin P450eryF (7), the transmittance at 405 nm is essentially unaffected by a substrate-induced spin shift. In our calculations we used an extinction coefficient of P450eryF of 74 mM−1cm−1, which is the mean of the coefficients of the high- and low-spin states of the enzyme (76 and 72 mM-1cm-1, respectively). According to our determination the extinction coefficient of F7GA at 405 nm is 4.95 mM−1cm−1. It should be noted that the correction for the internal filter effect affects only the measurements of the intensity of fluorescence in dilution experiments. No correction was necessary in the analysis of the changes in the fluorescence lifetime in either dilution or pressure-perturbation studies. In the dilution experiments the traces were normalized to the fluorophore concentration, so that the amplitude of the traces reflected the integral intensity of the specific fluorescence. In the high-pressure TRFS experiment we used the same highpressure cell as described above for the absorbance experiments. In these studies the laser light source was directly connected to the input window of the cell via a 3 mm-core liquid light guide (Newport Inc.). Another liquid light guide of the similar type was used to connect the fluorescence (orthogonal) window of the cell with the emission monochromator of FLS 920 through a light guide adapter (Edinburgh Instruments).

Data processing

Analysis of the series of spectra

obtained in our absorbance spectroscopy experiments was done using a principal component analysis (PCA) method, which is also known as singular value decomposition (SVD) technique, as described earlier (33, 42). To interpret the spectral transitions in terms of the changes in the concentration of P450 species, we used a least-squares fitting of the spectra of principal components by the set of the spectral standards of pure high-, low-spin and P420 species of P450eryF (7). All data treatment and fitting, as well as the data acquisition were performed using our custom designed software (33).

Analysis of the series of decay traces

obtained in dilution and pressure-perturbation experiment was performed using a principal component analysis procedure applied to series of decay traces re-sampled with a 0.5 ns time interval. In our analysis we used 50 ns-wide fractions of the decay traces. The initial 2.0 ns following the point of maximal intensity of the flash were excluded from the analysis to minimize the influence of the instrument response function. Our use of PCA decomposition complemented by the bi-exponential approximation of the principal vectors is described in detail in Supporting Information to this article. The results of this procedure were used to calculate the changes in the fraction of the fast phase of the decay, which was used as a measure of the changes in the averaged lifetime of the excited state.

Fitting of the titration curves

obtained in our absorbance titration and pressure-perturbation experiments was done with the use of Hill equation. To analyze the results of our dilution experiments we used the approximation by the equation for the isotherm of bimolecular association ((43), p 73, eq. II-53), which is also known as “tight binding” or “square root equation”.

Interpretation of the effect of pressure on spin equilibrium and substrate binding

was based on the canonical equation for pressure dependence of the constant of chemical equilibrium: Our interpretation of the pressure-induced changes is based on the equation for the pressure dependence of the equilibrium constant ((44), eq. 1):

| (1) |

or (in integral form, (45), p. 212, eq.9):

| (2) |

Here Keq is the equilibrium constants of the reaction at pressure P, P½ is the pressure at which Keq = 1 ("half pressure" of the conversion), ΔV° is the standard molar reaction volume, and K°eq is the equilibrium constant extrapolated to zero pressure, . For the analysis of the effect of pressure on the equilibrium of F7GA binding studied by FRET we used equation (2) combined with the equation for the isotherm of bimolecular association (see above).

All data processing procedures including principal component analysis and curve fitting with non-linear least squares optimization algorithms were performed using our custom-designed software (33).

RESULTS

Finding an appropriate fluorophore for the studies of the effect of pressure on ligand binding monitored by FRET

In our search for an appropriate fluorescent substrate-like ligand compatible with both absorbance UV-Vis and FRET-based binding studies using a pressure-perturbation approach we explored a variety of commercially available laser dyes (41). Our requirements for an appropriate fluorophore were: (1) high affinity binding to both P450eryF and CYP3A4; (2) high amplitude of the spin shift and prominent homotropic cooperativity with both enzymes; (3) minimal overlap of the absorbance/excitation band of the dye with the absorbance bands of P450; (4) high intensity of fluorescence emission with a reasonable spectral overlap with the α and β bands of P450 absorbance; (5) minimal effect of solvent on the lifetime, intensity of fluorescence, and the position of the emission band. Most of the laser dyes where the fluorescence band overlaps with the P450 α and β bands are derivatives of coumarin, rhodamine, fluorescein, or pyromethene (BODIPY). The last three classes of substances have virtually no affinity for P450eryF. Coumarins are known to be P450 substrates and showed modest affinity for P450eryF and CYP3A4 (typical S50 values are around 50 µM or higher). However, the combination of high extinction coefficients and low amplitude of the ligand-induced spin shift makes the coumarins poorly suitable for UV-Vis absorbance studies.

Among the other dyes, Fluorol 7GA (Fluorol-555), and Phenoxazone 9 (Nile Red) appear to be the most appropriate as potential P450 substrates. Nile Red has been already shown to be a high-affinity substrate of CYP3A4. Binding of Nile Red induces a high amplitude spin shift and reveals a prominent cooperativity in CYP3A4 (46). Our preliminary experiments showed that Nile Red is a good ligand for P450eryF (S50 = 3.2 ± 0.2 µM, n = 1.6 ± 0.2), where it induces a spin shift with the maximal amplitude (ΔFhmax) of 35%. However, the solvatochromic shift of the emission band, and strong dependence of the fluorescence intensity on the polarity of the environment complicate the use of Nile Red in FRET studies.

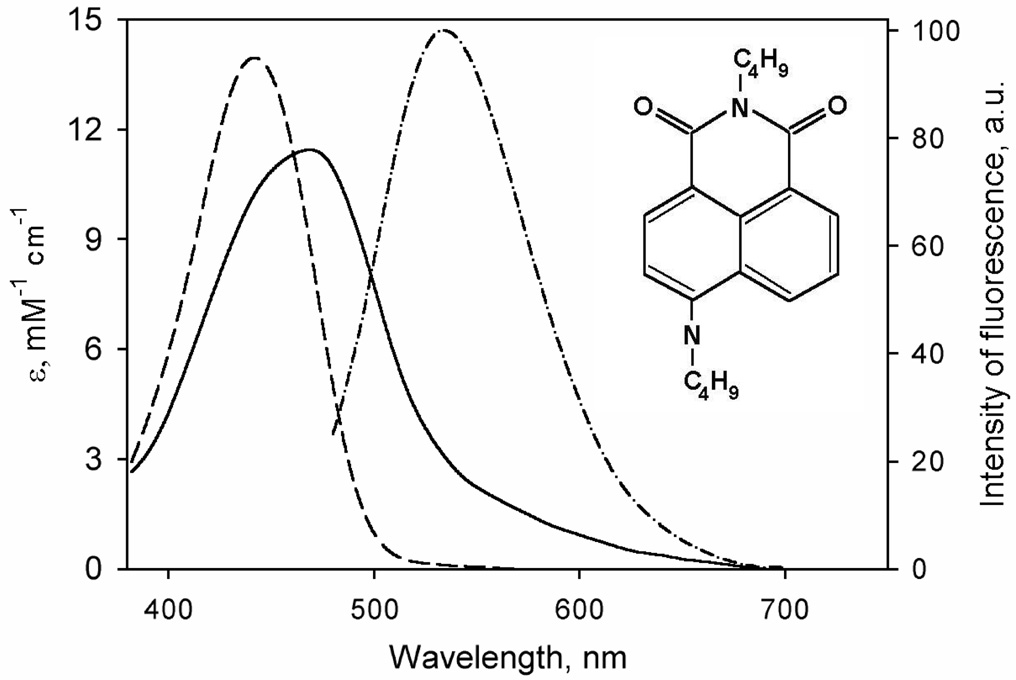

In contrast, the features of Fluorol 7GA, a quinoline derivative, are very favorable for our intended use. The chemical structure of this compound along with its spectra of absorbance and fluorescence are shown in Fig. 1. The main absorbance band, which is positioned at 440 nm in methanol and around 465 nm in aqueous solution, is characterized by an extinction coefficient of 14.1 mM−1cm−1 in methanol (41) and 11.4 mM−1cm−1 in water (own results). This is low enough to permit monitoring of P450 spectral changes in the Soret region. A broad emission band is centered around 550 nm (in aqueous solution) and exhibits a modest solvatochromic blue shift (≤20 µm) upon transition to a more hydrophobic environment, while the fluorescence intensity remains virtually unaffected. An increase in F7GA concentration in water to >25 µM results in a blue shift of the emission band, which may reflect aggregation. This effect can be prevented by addition of 0.6 mg/ml HPCD. In the presence of HPCD the position of the emission maximum is shifted to 540 nm, and the concentration-dependent blue shift is not observable (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Structure and spectral properties of Fluorol-7GA), 2-butyl-6-(butylamino)-1H-benzo[de]isoquinoline-1,3(2H)-dione, see the structure shown as an insert ). Spectra of molar absorbtivity in 0.1 M Na-Hepes buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.6 mg/ml HPCD and in methanol are shown by solid and dashed lines, respectively. Spectrum of emission (excitation at 405 nm by a diode laser) is shown in dashed-and-dotted line.

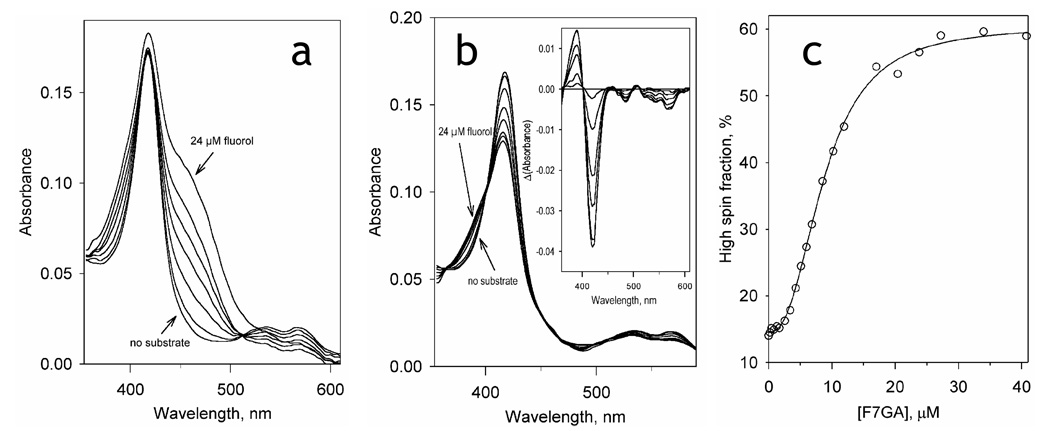

As illustrated in Fig. 2, the interactions of F7GA with P450eryF result in a high-amplitude spin shift, which reveals high affinity binding with distinct homotropic cooperativity. Averaging the parameters obtained from three independent titration experiments gives an S50 value of 8.2 ± 1.3 µM, a Hill coefficient of 2.3 ± 0.2, and a maximal amplitude of the spin shift of 55 ± 6%. It should be noted that our preliminary studies with CYP3A4 showed that F7GA interacts with this human enzyme with the parameters close to those cited above for P450eryF (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Titration of P450eryF (1.8 µM) with Fluorol-7GA. (a) A series of absorbance spectra recorded at increasing concentrations of Fluorol. (b) The same series of spectra with the Fluorol absorbance subtracted. The inset shows the difference spectra. (c) the changes in the P450 spin state. The solid line shows the data fitting by the Hill equation (S50 = 8.7µM, n = 2.3, ΔF(high spin)max= 46%).

Interactions of F7GA with P450eryF studied by lifetime FRET

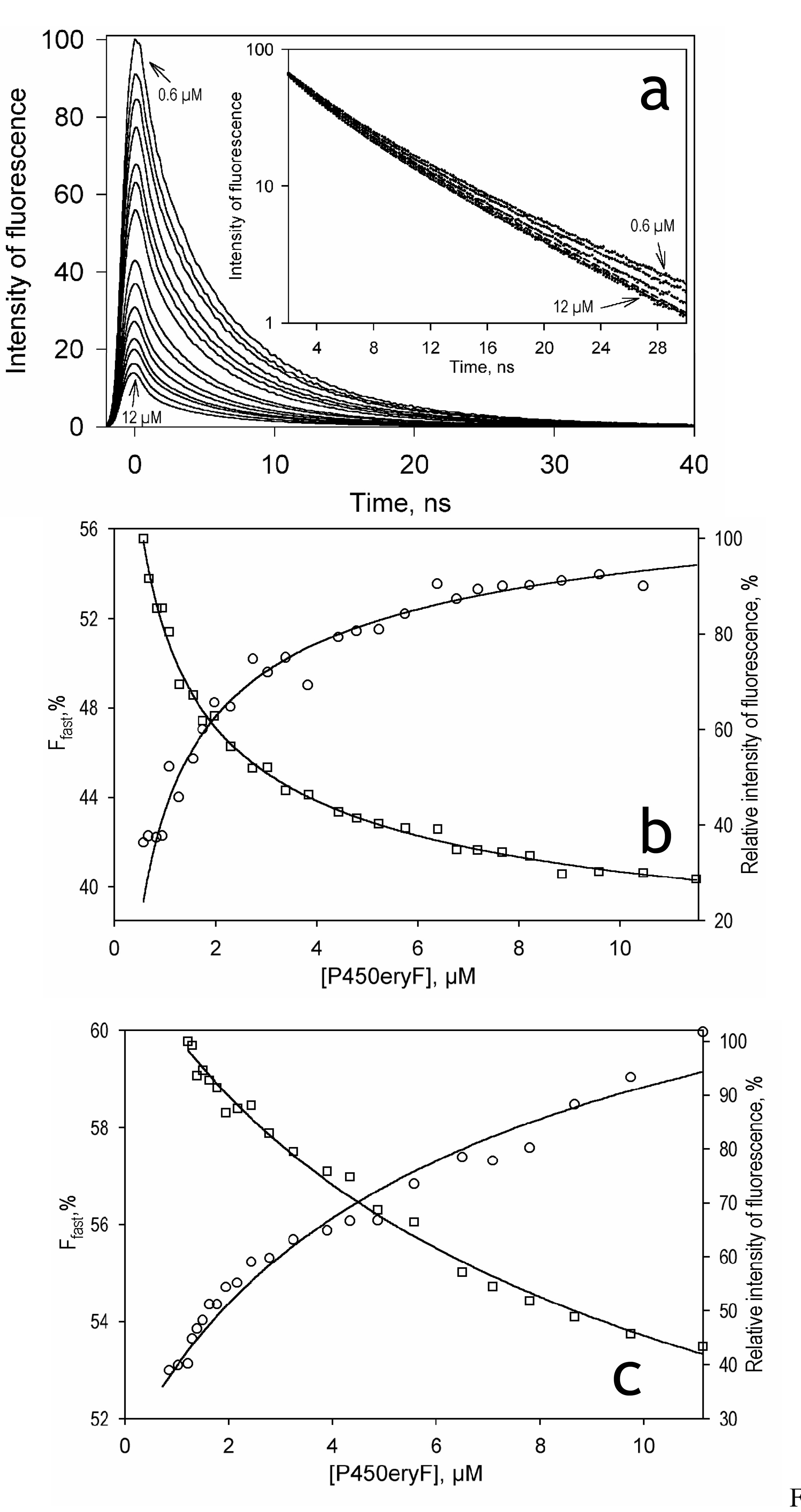

Due to an overlap of the fluorescence emission band of F7GA with the α and β absorbance bands of P450eryF, the binding of F7GA is expected to cause an efficient FRET from the dye to the P450 heme. This would allow us to detect the binding of F7GA by monitoring a decrease in the fluorescence intensity and/or decrease in the fluorescence lifetime due to FRET. To exploit this possibility we performed a series of titration-by-dilution experiments and monitored the fluorescence decay traces. In these experiments a solution of P450eryF and F7GA taken at either 1:1 or 1:3 molar ratios was gradually diluted from an enzyme concentration of 10–15 µM down to 0.1–1 µM. A series of decay traces obtained in a 1:1 P450eryF:F7GA dilution experiment is shown in Fig. 3a. The traces in the main panel are normalized to the fluorophore concentration, so that the amplitude of the traces ct the integral intensity of the specific fluorescence. The traces may be approximated by a combination of two exponential terms with the characteristic times of 1.2 and 6.25 ns respectively. The square correlation coefficient (p2) for such a fitting was greater than 0.999 in the whole range of the concentrations studied. As seen from Fig.3a, the specific amplitude of the traces decreases at increasing concentrations of reactants. This decrease in the amplitude is accompanied by an increase in the rate of the fluorescence decay (see Fig. 3a inset). This concomitant decrease in the intensity of fluorescence and the fluorescence lifetime are indicative of FRET from F7GA to the P450 heme. The fitting of the titration curves obtained from the analysis of the fluorescence intensity (Fig. 3b, squares) and the fluorescence lifetime (Fig. 3b, circles) to the equation of binary association gives nearly similar values of the KD of the complex. The estimates obtained by averaging the results of five individual experiments are equal to 0.14 ± 0.06 µM (lifetime) and 0.10 ± 0.06 (intensity). These values are lower than the S50 determined by spectrophotometric titration by more than an order of magnitude, suggesting a multi-site binding mechanism. We may conclude, therefore, that the binding of F7GA to the high-affinity binding site detected in these experiments does not result in the displacement of the spin equilibrium of the enzyme. This conclusion is in agreement with our earlier findings on the interactions of P450eryF with 1-PB (7, 13). As judged from the amplitude of the curves reflecting the decrease in the intensity of F7GA fluorescence, the efficiency of FRET from F7GA to the heme is close to 100%.

Fig. 3.

Interactions of Fluorol-7GA with P450eryF studied by the lifetime FRET assay: Panel a shows a series of fluorescence decay traces (excitation at 405 nm by a pulsed diode laser) registered in a titration-by-dilution experiment at 1:1 enzyme/substrate ratio. The amplitudes of the traces are normalized to the concentration of Fluorol and corrected for the internal filter effect, as described in Materials and Methods. The inset shows the same decay traces normalized to the amplitude in semi-logarithmic coordinates. All the curves of the set may be approximated by a sum of two exponents with the characteristic times of 1.2 and 6.25 ns (p2>0.999). Panel b shows the titration curves deduced from the above dataset by analyzing the fraction of the fast decay phase (Ffast, circles) and the specific amplitude of the decay trace (squares, ordinate on the right). Results of the fitting of these dependencies by the equation of bimolecular association (KD = 0.132 ± 0.008 and 0.135 ± 0.003 µM, respectively) are shown in solid lines. Panel c shows the titration curves obtained in a similar experiment at a 1:3 enzyme-to-substrate ratio. Here the fitting of the concentration dependencies of Ffast and the specific amplitude results in the KD values of 18.1 ± 0.3 and 25.6 ± 0.6 µM, respectively.

The behavior of the system observed in the dilution experiments at excess substrate (P450:F7GA molar ratio of 1:3) is qualitatively similar to that described above for the equimolar mixture of reactants. Here again, an increase in the concentrations of the reactants resulted in a decrease in the specific intensity of fluorescence (Fig. 3c, squares) concomitant with a decrease in the fluorescence lifetime (increase in the fraction of the fast decay phase, Fig. 3c, circles). However, the fitting of these titration curves gives values of the dissociation constant that are over an order of magnitude higher than those obtained with the equimolar mixture of reactants namely 13.6 ± 5.5 and 20.1 ± 16.5 µM for the analysis of the fluorescence lifetime and the intensity, respectively (from three independent experiments).

The difference in the KD values determined at two enzyme:substrate ratios suggests the presence of two distinct substrate binding sites in the enzyme. In the case of a sequential mechanism with two binding sites, the studies of enzyme-substrate interactions by dilution of a 1:1 enzyme-substrate mixture are specific for determination of the KD at the first (higher affinity) binding site, provided that the affinities of the two sites are considerably different (6, 47). On the other hand, dilution experiments at excess substrate can be used to resolve substrate binding at a lower affinity site when the higher affinity site is already saturated (5). Assuming the dissociation constant for the first binding site to be equal to 0.15 µM, as determined above, at a 3-fold molar excess of substrate the saturation of the higher affinity site will reach 90% at an enzyme concentration of 0.67 µM. At higher enzyme concentrations the high affinity binding site may be considered completely saturated, and the titration-by-dilution experiments will reflect the binding at the second (lower affinity) site only. Therefore, the above results are consistent with a sequential binding mechanism with (at least) two substrate binding sites, as suggested earlier for the interactions of P450eryF with 1-PB (6, 7) and testosterone (9).

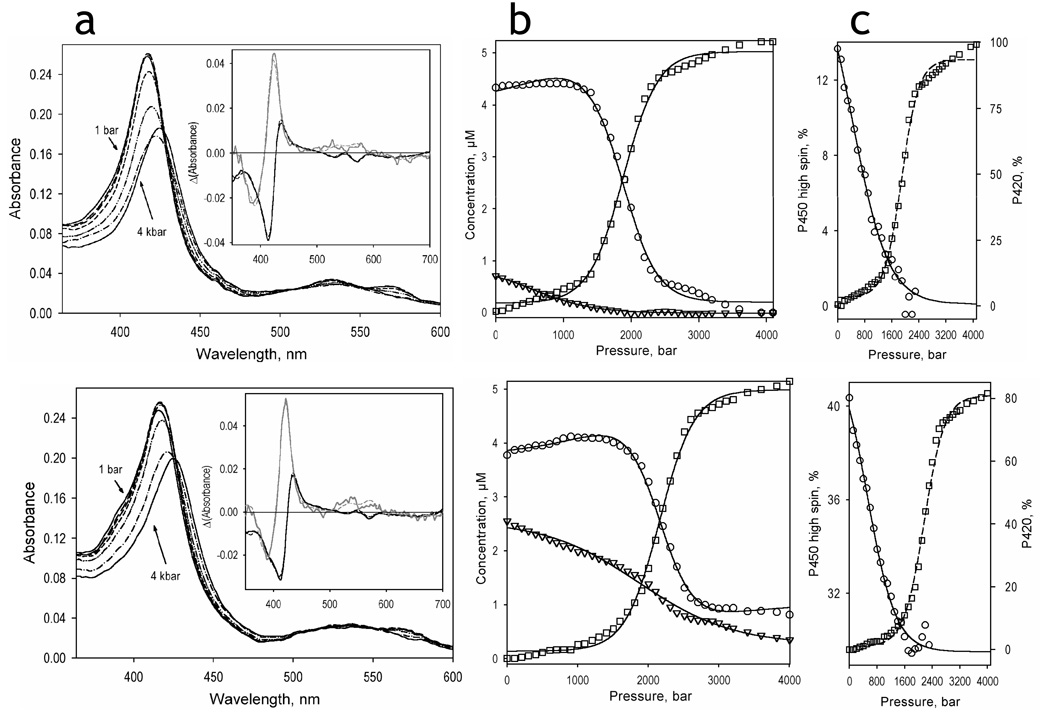

General characterization of pressure-induced transitions in P450eryF studied by absorbance spectroscopy

The effect of hydrostatic pressure on the absorbance spectra of P450eryF in the absence of F7GA and at a saturating concentration is illustrated in Fig. 4 along with the changes in the concentrations of the high-spin, low-spin, and P420 states of the enzyme. The transitions observed here are qualitatively similar to those reported in our studies with CYP3A4 (18, 19). As seen in the inset in Fig. 4a, the spectra of the first two principal components given by PCA may be adequately approximated by a combination of standards of pure high-spin, low spin and apparent P420(Fe3+) states of P450eryF (18). These two components account for over 99.9% of the total spectral changes observed at pressure increase. While the second principal vector corresponds to a pressure-induced displacement of the spin equilibrium towards the low-spin state, the first component reflects a displacement of the Soret band from 417 nm to ~426 nm. This transition, which has already been reported for P450cam (37, 48), P450lin (48), CYP2B4 (33, 38), P450BM3 (25) and CYP3A4 (18, 19), is commonly attributed to the pressure-induced conversion of the low-spin P450 into P420 (25, 30, 37, 38, 48). The plots of the concentrations of the three P450 states versus pressure (Fig. 4b) show that at pressures below 1000 bar the main transition of the protein is represented by a spin shift, whereas at higher pressures a considerable conversion into the apparent P420 state is observed.

Fig. 4.

Pressure-induced transitions in P450eryF in the absence of ligand (top) and in the presence of 50 µM Fluorol (bottom). Panels a shows the series of spectra obtained at 1 bar (solid lines), 800 bar (long dash), 1200 bar (medium dash), 1600 bar (short dash), 2000 bar (dash-double-dot), 2400 bar (dash-dot), and 4000 bar (solid lines). Insets show the spectra of the first (black) and second (gray) principal components obtained by the application of PCA to the corresponding difference spectra. The spectra are normalized to represent the transitions in 1 µM protein. Dashed lines represent the approximations of the principal component spectra by combinations of the spectral standards of the low-spin, high-spin and P420-states of P450eryF. Panels b show the corresponding changes in the concentration of the high-spin (triangles), low-spin (circles), and P420 (squares) states of P450eryF. The pressure-induced changes in the high-spin fraction of the P450 state of the enzyme (circles, solid line) and in the fraction of the P420 state of the enzyme (squares, dashed line) are illustrated in panels c.

The plots of the fraction of P420 of the total enzyme content in the absence of F7GA and at a saturating concentration are shown in Fig. 4c (squares, dashed lines). As seen from these plots, the P450→P420 transition in P450eryF comprises 90 ± 5% of the enzyme pool, regardless of the substrate concentration. In this regard P450eryF closely resembles monomeric CYP3A4 incorporated into Nanodiscs (CYP3A4ND) (19) and is distinct from CYP3A4 or CYP2B4 oligomers, where only about two-thirds of the total heme protein was susceptible to this process (18, 33, 38). Also similar to CYP3A4ND, we observed no slow, irreversible P450→P420 conversion in P450eryF of the kind noted with CYP3A4 oligomers (18). The partitioning between P450 and P420 states of P450eryF reaches its steady state in less than 30 sec after pressure increase and reverses almost completely within 10 minutes upon decompression (data not shown). The parameters of this pressure-induced inactivation reveal no dependence on the substrate concentration and are similar (ΔV°= −94.7 ± 5.7 ml/mol, P½ = 2052 ± 60 bar) to those observed with CYP3A4ND. The close resemblance of the properties of P450eryF to those of CYP3A4ND is consistent with our conclusion that the functional heterogeneity of P450 in solution (18, 47, 49) is due to the oligomerization of the enzyme.

Pressure-induced changes in the high-spin content of the substrate-free enzyme and P450eryF saturated with F7GA shown in Fig. 4c (circles, solid line) provide an additional indication of close similarity between the barotropic properties of P450eryF with those of CYP3A4. Thus, high pressure induces a complete displacement of the spin equilibrium in P450eryF towards the low-spin state only in the absence of substrate. In the presence of a saturating concentration of F7GA, an allosteric substrate, the maximal amplitude of the pressure-induced high-to-low spin conversion does not exceed one-third of the initial high-spin content.

Similar to earlier reports on CYP3A4 (19) and CYP2B4 (33) the pressure-induced changes in the position of spin equilibrium of P450eryF were completely reversible upon decompression. The apparent P450→P420 transition was also partially reversible upon decompression from pressures below 2500 bar. However the reverse transition was slow, taking about 15–20 min after decompression to reach 80% level of P450 recovery. Decompression from pressures higher than 2500 bar resulted in an important decrease in the heme protein concentration due to apparent heme loss (data not shown).

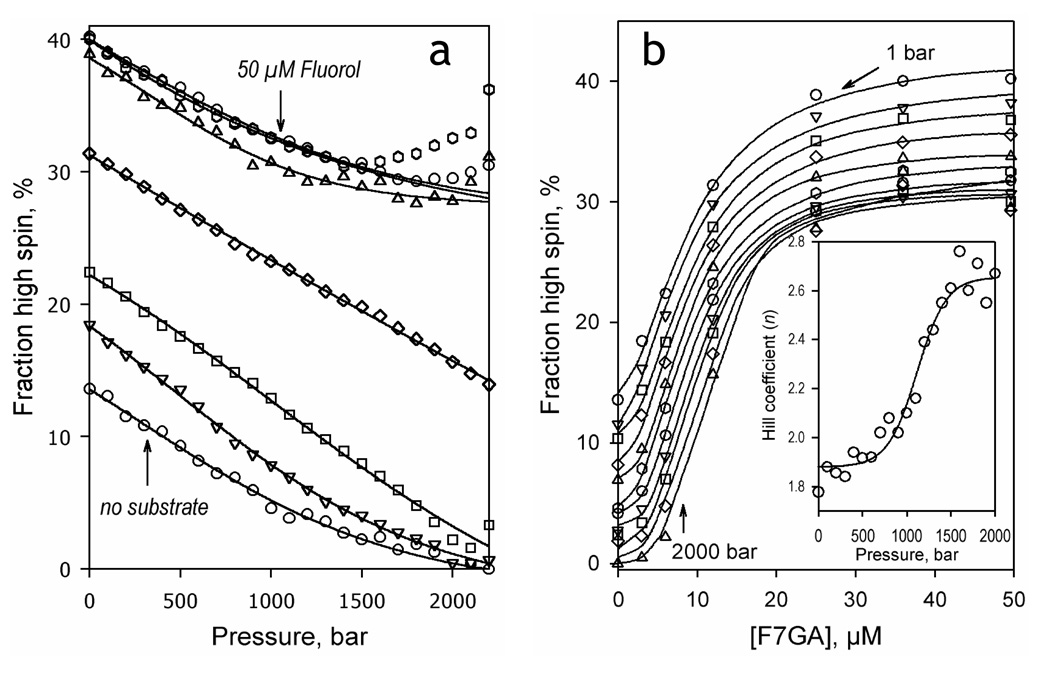

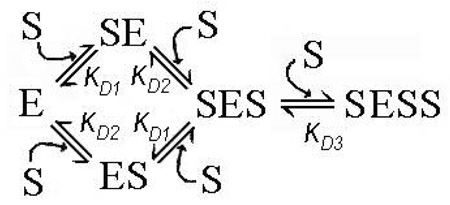

Analysis of the effect of hydrostatic pressure on the spin equilibrium of P450eryF in the presence of increasing concentrations of F7GA

For in-depth analysis it was necessary to resolve the barotropic parameters of the spin transitions of the substrate-free and F7GA-bound P450eryF from those of the dissociation of the F7GA complex with the enzyme. For this purpose we studied pressure-induced spin transitions of P450eryF at a series of F7GA concentrations ranging from 0 to 50 µM. As seen from Fig. 5a, although addition of F7GA increases the high spin content in the enzyme, the amplitude of the pressure-induced high-to-low spin shift tends to decrease at increasing substrate concentrations. This behavior, which is similar to that observed with CYP3A4 in the presence of 1-PB or testosterone (19), represents a sharp contrast with other bacterial enzymes, such as P450cam (37, 48), P450lin (37) and the heme domain of P450 BM3 (25).

Fig. 5.

Effect of hydrostatic pressure on the interactions of P450eryF with Fluorol-7GA. The left panel shows the effect of hydrostatic pressure on the spin state of P450 at 0, 3, 6 and 12, 25, 36 and 50 µM Fluorol-7GA. The right panel shows the same results as a series of titration curves obtained at hydrostatic pressure increasing from 1 bar to 2000 bar in 200 bar increments. The inset illustrates the effect of hydrostatic pressure on the Hill coefficient of the interactions.

The dependencies of the high spin content of P450eryF on the F7GA concentration (e.g., binding isotherms) at variable pressure are shown in Fig. 5b. These curves were analyzed by fitting them to the Hill equation (solid lines). As seen from the Fig. 5b inset, an increase in hydrostatic pressure results in increased homotropic cooperativity, similar to the effect of pressure on 1-PB or testosterone interactions with CYP3A4.

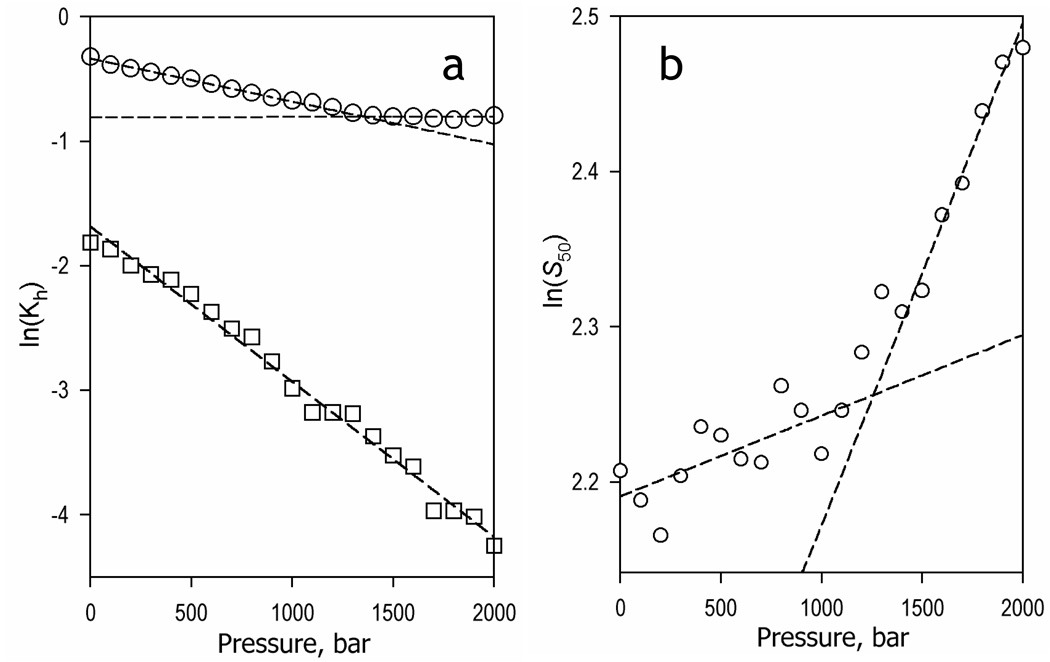

The effect of hydrostatic pressure on the values of the constant of spin equilibrium of substrate-free (Kh,free) and F7GA-bound enzyme (Kh,S) is illustrated in Fig. 6a. The logarithm of the constant of spin equilibrium in the substrate-free enzyme reveals a canonical linear dependence on pressure (1) expected for a simple reversible transition (see eq. 2) and exhibits the values of ΔV° and K°h,0 of 30.9 ± 0.7 ml/mol and 0.19 ± 0.01, respectively. However, the dependence of the ln(Kh,S) on pressure of the F7GA-bound enzyme reveals a break at ~1300 bar. This break signifies a change in the ΔV° from 8.2 ± 0.2 ml/mol to about zero (0.1 ± 0.16 ml/mol), while the value of K°h,s changes from 0.71 ± 0.01 to 0.45 ± 0.01. Therefore, similar to CYP3A4 with allosteric substrates (19) , an increase in hydrostatic pressure appear to displace a conformational equilibrium in P450eryF from a conformation predominating at ambient pressure (R-state) to a pressure-promoted conformation (P-state). The latter is characteristic of an extreme stabilization of the substrate-bound high-spin state.

Fig. 6.

Effect of hydrostatic pressure on the parameters of spin equilibrium and Fluorol binding in P450eryF. Panel a illustrate the effect of hydrostatic pressure on the constant of spin equilibrium of the substrate-free (squares) and Fluorol-bound enzyme (circles). Panel b exemplifies the pressure dependence of the S50 value. Dashed lines show linear approximations of the entire dataset (panel a, squares) or the initial and final parts of the curves (panels a and b, circles).

Interestingly, changes in S50 represent nearly a mirror image of those observed with K°h,s. The dependence of ln(S50) on pressure exhibits a break at around 1200 bar. This behavior signifies a transition from a state with an apparent molar volume change in substrate complex dissociation around zero (ΔV°diss,app. = −1.3 ± 0.5 ml/mol, S°50 = 8.9 ± 0.2 µM) to a state characterized by ΔV°diss,app. = −8.0 ± 0.1 ml/mol (S50° = 6.4 ± 0.02 µM). It should be noted, however, that the complex nature of S50, the quantitative interpretation of which largely depends on the mechanistic interpretation of cooperativity, precludes any straightforward analysis of the apparent values of ΔV°diss discussed here. Such quantitative analysis was made possible through a combination of pressure-perturbation with direct monitoring of F7GA binding utilizing lifetime fluorescence of enzyme-substrate mixtures as described below.

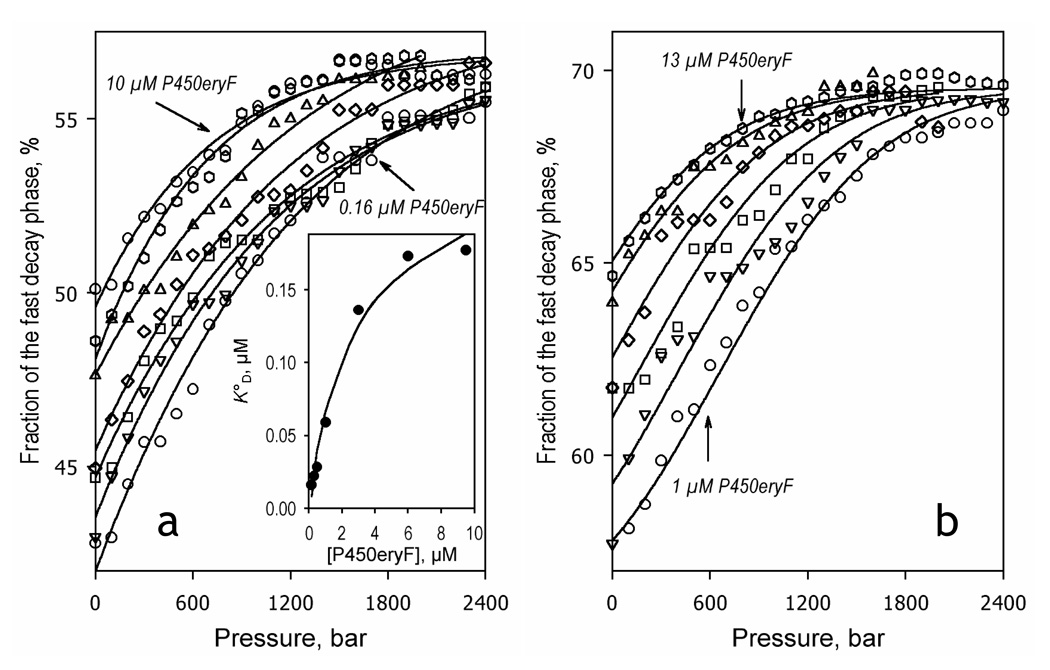

Effect of hydrostatic pressure on the interactions of F7GA with P450eryF studied with lifetime FRET detection

Our control experiment revealed no considerable pressure-induced changes in the fluorescence decay curves of Fluorol in solution in the presence of HPCD. Therefore, lifetime fluorescence detection study F7GA interactions with P450eryF at ambient pressure may also be applied to study the effect of hydrostatic pressure on ligand binding. In order to resolve the volume changes in two apparent consecutive substrate binding events, we performed these studies in mixtures of P450eryF with F7GA taken at either equimolar concentration or at excess substrate (1:3 molar ratio). As shown in Fig. 7 increasing hydrostatic pressure results in an increase in the fraction of the fast exponential phase (Ffast) of the decay at both molar ratios probed. All pressure-induced changes in the decay traces were completely and immediately reversible upon decompression provided the pressure did not exceed 2500 bar (see inset in Fig. S1 in the Supporting Information). The shortening of the average lifetime of the excited state of the probe is indicative of an increase in the efficiency of FRET, which signifies a displacement of the equilibrium of substrate binding towards the substrate-bound state. This interpretation of the changes is confirmed by the fact that, for both of the reactant ratios, the increase in the concentrations results in a decrease in the amplitude of pressure-induced changes in Ffast (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Effect of hydrostatic pressure on the interactions of P450eryF with Fluorol-7GA monitored by lifetime FRET at a 1:1 (left) and 1:3 (right) enzyme:substrate ratio. The dependencies of the relative amplitude of the fast decay phase on hydrostatic pressure are shown for 3, 0.5, 0.32 and 0.16 µM and for 9.6, 5.5, 3.3 and 1.8 µM enzyme concentrations for the left and right panels, respectively. Solid lines in panel a show the results of the fitting of the pressure dependencies (taken individually) to the equation for the equilibrium of binary association with pressure-dependent KD. The inset in this panel shows the concentration dependence of the resulting value of KD°. Lines in panel b represent the results of global fitting of the whole dataset to the same equation.

Approximation of the series of pressure dependence curves obtained at a 1:3 molar ratio (Fig. 7b) with an equation for pressure dependence of bimolecular association (see Materials and Methods) results in a satisfactory fit (p2 = 0.978) and gives the estimates of KD° and ΔV°diss of 7.7 ± 1.5 µM and 61.3 ± 1.0 ml/mol, respectively. The above value of KD° appears to be in a reasonable agreement with the values of 10 – 15 µM obtained from the fluorescence lifetime dilution experiments at excess substrate performed at ambient pressure (see above). Therefore, our results demonstrate that the F7GA binding to P450eryF detected in the dilution experiments at excess substrate is promoted by increased hydrostatic pressure. The decrease in volume of the system observed upon the binding of F7GA to P450eryF may indicate that the formation of the complex induces an important hydration of the enzyme.

In the case of the experiments performed at a 1:1 molar ratio (Fig. 7a) the situation appears to be more complex. The qualitative behavior of the system is also consistent with pressure-induced association of the enzyme-substrate complex. However, our attempts to fit the whole dataset to the equation for pressure dependence of bimolecular association results in considerable systematic deviations of the experimental results from the fitting curves (data not shown). Individual fitting of the curves results in an adequate fitting (p2 > 0.985), which shows no significant changes in the estimate of ΔVdiss with enzyme concentration. This value was found to remain equal to 56 ± 10 ml/ml in the whole range of concentrations probed. Averaging of the estimates of KD°s found by individual fitting gives the value of 0.09 ± 0.05 µM. This value is also in reasonable agreement with the value determined in our dilution titration at ambient pressure (0.15 – 0.17 µM). However, the estimate of KD° exhibits a well-defined dependence on concentration, as it changes from 0.016 at 0.16 µM P450eryF to 0.18 µM at 9 µM enzyme (Fig. 7a, inset). Therefore, although these results clearly indicate that the interactions of F7GA with P450 are promoted by pressure, they also suggest that the sequential scheme of P450eryF cooperativity with two consecutive binding events (6, 7, 9) is significantly oversimplified. As a result, the resolution of the first (highest affinity) binding event in the dilution experiments at 1:1 molar ratios is essentially incomplete. Moreover, in contrast to large positive values of ΔV°diss determined in our fluorescence lifetime experiments, the estimates of apparent ΔV°diss deduced from the effect of pressure on S50 values are negative and rather insignificant (see above). This contradiction may suggest the involvement of an additional (third) substrate binding event in the cooperativity mechanism.

DISCUSSION

In this study we used pressure perturbation in conjunction with TRFS to study the mechanism of substrate binding in P450eryF. This innovative combination provides a powerful approach for studying protein-ligand interactions and ligand-induced changes in the protein. To make this approach feasible we utilized a novel high-affinity fluorescent ligand, Fluorol 7GA. This laser dye was found to bind with high affinity to cytochromes P450eryF and CYP3A4, revealing prominent cooperativity and a high amplitude of the substrate-induced spin shift. F7GA exhibits a favorable combination of such properties as high intensity of fluorescence, appropriate position of the excitation and emission bands, low extinction coefficient, and a high affinity to P450eryF. These features allowed us to combine steady-state and time-resolved fluorescence detection of ligand binding with conventional monitoring of substrate interactions by changes in P450 absorbance (substrate-induced spin shift). The lack of any significant effect of hydrostatic pressure on the fluorescence lifetime of F7GA in solution makes this probe perfectly suitable for pressure-perturbation studies with TRFS detection.

Studies of the effect of pressure on the F7GA-induced spin shift in P450eryF were carried out in very similar fashion to our recent study with CYP3A4, where we employed bromocriptine, 1-PB, and testosterone as substrates. Our current results demonstrate that the unusual barotropic behavior of CYP3A4, which distinguishes this enzyme from other cytochromes P450 studied so far, is also characteristic of P450eryF. In particular, an increase in hydrostatic pressure fails to induce a complete high-to-low spin shift in the enzyme complex with allosteric substrates (such us F7GA in this study, or 1-PB or testosterone in our study with CYP3A4). Moreover, the pressure-dependent equilibrium between two P450 conformations (R and P conformations, according to the designation used in (19)) that was proposed to account for non-linearity of the plots of ln(Kh) and ln(KD) versus pressure (i.e. a pressure-induced change in ΔV° of substrate binding and spin transitions) observed with CYP3A4 (19) is also applicable to P450eryF. Interestingly, in CYP3A4 this apparent R→P transition was observed in both substrate-free and substrate-bound enzyme. In contrast, in P450eryF this transition is characteristic solely of the ligand-bound enzyme, where it decreases the value of ΔV°h from 8.2 ml/mol to zero and causes unusual stability of the high-spin state at high pressures. Importantly, together with the change in ΔV°h discussed above, the R→P transition also results in an increase in the Hill coefficient, which suggests that this apparent pressure-dependent conformational equilibrium is directly involved in the mechanism of cooperativity.

Concomitant with the increase in cooperativity, elevated pressures above 1300 bar also enhance the apparent molar volume change of F7GA binding, as determined from the pressure dependence of the S50 value. Whereas at low pressures this value remains almost insensitive to pressure increase, raising pressure above ~1300 bar results in an S50 increase (see Fig. 6b). Interestingly, the direction of this change is opposite to that observed with CYP3A4, where there is a pressure-induced decrease in S50 at pressures above 1500 bar (19). However, due to the complex nature of S50, which does not represent any particular equilibrium constant, it does not seem possible to draw any direct mechanistic conclusions from this difference.

Analysis of barotropic behavior of the individual substrate binding events is essential for any mechanistic interpretation of the effect of pressure on cooperativity in substrate binding. In order to approach this analysis we employed FRET from F7GA to the P450 heme monitored by TRFS to monitor the interactions of F7GA with P450eryF directly. Analysis of the interactions of F7GA at ambient pressure confirmed that binding results in an efficient FRET from F7GA to the heme. This effect may be detected by either a decrease in the intensity of fluorescence or decrease in the average lifetime of the excited state.

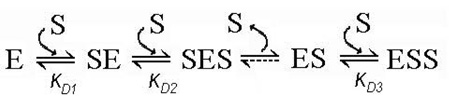

Dilution experiments at two different molar ratios of the reactants allowed us to resolve two apparent F7GA binding events with dissociation constants of 0.1-0.2 and 10 – 15 µM. At first glance these results are consistent with a simple sequential mechanism with two binding sites hypothesized earlier for the interactions of the enzyme with 1-PB and testosterone (6, 7, 9). However, our pressure-perturbation experiments with TR-LIFS showed that the mechanism of cooperativity may be considerably more complex. Both apparent association processes are promoted by hydrostatic pressure, so that their characteristic ΔVdiss are given by large positive values (60 – 100 ml/mol). On the other hand, the apparent value of ΔV°diss of F7GA binding determined from the pressure dependence of S50 and, therefore, characteristic of the overall sequence of binding events resulting in a spin shift, is close to zero (−1.3 ml/mol for R-state and −8.0 for P-state). To resolve this discrepancy we have to infer that the sequence of binding events that causes a spin shift includes one additional step beyond the two binding processes revealed in our 1:1 and 1:3 dilution experiments. In order to explain an overall apparent ΔV°diss value close to zero, as deduced from the effect of pressure on S50, this third binding process would have to exhibit a large negative ΔV°diss in order to compensate for the large positive values observed in our TRFS studies.

This conclusion is also consistent with the fact that the Hill coefficient for F7GA binding at ambient pressure is as high as 2.3 ± 0.2 and approaches the value of 3 at 2000 bar. The value of the Hill coefficient may be considered as an estimate of the minimal number of individual binding sites involved in the cooperativity mechanism (see, for example, (50)). Therefore, we may hypothesize involvement of at least three substrate binding events in the mechanism of F7GA cooperativity.

Furthermore, the set of pressure dependencies of the fluorescence lifetime of F7GA for a series of 1:1 enzyme-substrate mixtures (Fig. 7a) cannot be fitted globally to an equation of binary complex formation with a single pressure-dependent KD value. Fitted individually, these curves reveal the values of K°D increasing from 0.016 to 0.17 µM at the concentrations increasing from 0.16 to 9.5 µM. This irregularity suggests that the dilution experiments performed at 1:1 enzyme:substrate ratio reflect more than one substrate binding step. One of the simplest possible mechanisms of this kind may be a “three-site semi-ordered binding mechanism”, which involves two independent (parallel) substrate binding processes and a subsequent binding of the third substrate molecule:

Another equally possible, simple mechanism may involve two binary (1:1) enzyme substrate complexes SE and ES connected via an intermediate (unstable) ternary complex (SES):

In this scheme, which we may designate as a “three-site sequential ping-pong mechanism”, the binding of the first (“starter”) substrate molecule to the enzyme with the formation of complex SE is followed by the second binding event, which results in the formation of the intermediate complex SES. Dissociation of this hypothetically unstable complex releases the “starter” substrate molecule and results in the formation of the complex ES, which precedes the formation of the stable complex ESS.

In both cases the results of dilution experiments at a 1:1 enzyme:substrate ratio would represent a superposition of two 1:1 binding processes, even in the case where only one of the two binary complexes (either SE or ES) is detectable in TRFS measurements (i.e., exhibits FRET from F7GA to the heme). If the difference between the constants KD1 and KD2 is not significant, the presence of two different types of binary complex may be masked in simple dilution experiments. However, any difference in barotropic parameters of the two binding processes would cause an anomalous behavior of the system in pressure-perturbation experiments, as observed in our experiments.

Further elaboration of the mechanistic scheme is not possible at this stage due to uncertainty about the exact nature of the complexe(s) revealed in our TRFS experiments. Differentiation between the proposed mechanisms would require additional studies. In particular, important information may be obtained from continuous variation (Job’s titration) studies, which would determine the stoichiometry of ligand binding. These studies are now in progress and will be presented in a forthcoming report.

It should also be noted that the observation that at least one of the two initial F7GA binding events is characterized by a large positive ΔV°diss value (i.e., promoted by pressure increase) is quite unexpected. Increasing hydrostatic pressure is usually thought to cause dissociation of enzyme-substrate complexes (25, 29, 30, 44) due to displacement of substrate molecule from the binding site upon pressure-promoted protein hydration. The opposite effect of pressure may signify a substrate-induced conformational change in the enzyme, which is associated with an important protein hydration. The volumetric effect of this hydration appears to be, however, compensated in the overall reaction mechanism by a large volume change of the opposite sign in a subsequent (final) substrate binding event. This compensation results in an unusual stability of the eventual enzyme-substrate complex, which is presumably characterized by decreased water accessibility of the heme pocket of the pressure-promoted conformation of P450eryF and CYP3A4 compared with other P450 enzymes studied so far.

Supplementary Material

The application of principal component analysis to the analysis of the series of fluorescence decay curves used in this study is described and illustrated in Supporting Information, which is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to Dr. Urmila Rawat (University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston) for her participation in the experiments on the effect of hydrostatic pressure on the spin state of P450eryF in the presence of F7GA.

ABBREVIATIONS AND TEXTUAL FOOTNOTES

- P450eryF

cytochrome P450eryF

- F7GA

Fluorol-7GA (2-butyl-6-(butylamino)-1H-benzo[de]isoquinoline-1,3(2H)-dione)

- DTT

dithiothreitol; Hepes, N-[2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N'-[2-ethanesulfonic acid]

- 1-PB

1-pyrenebutanol

- HPCD

hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin

- ANF

α-naphthoflavone

- TRFS

time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy

Footnotes

This research was supported by NIH grant GM54995 and research grant H-1458 from the Robert A. Welch Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atkins WM. Current views on the fundamental mechanisms of cytochrome P450 allosterism. Expert Opinion Drug Metab. Toxycol. 2006;2:573–579. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2.4.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harlow GR, Halpert JR. Analysis of human cytochrome P450 3A4 cooperativity: construction and characterization of a site-directed mutant that displays hyperbolic steroid hydroxylation kinetics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:6636–6641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Korzekwa KR, Krishnamachary N, Shou M, Ogai A, Parise RA, Rettie AE, Gonzalez FJ, Tracy TS. Evaluation of atypical cytochrome P450 kinetics with two-substrate models: evidence that multiple substrates can simultaneously bind to cytochrome P450 active sites. Biochemistry. 1998;37:4137–4147. doi: 10.1021/bi9715627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cupp-Vickery J, Anderson R, Hatziris Z. Crystal structures of ligand complexes of P450eryF exhibiting homotropic cooperativity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:3050–3055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050406897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davydov DR, Botchkareva AE, Davydova NE, Halpert JR. Resolution of two substrate-binding sites in an engineered cytochrome P450eryF bearing a fluorescent probe. Biophys. J. 2005;89:418–432. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.058479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davydov DR, Botchkareva AE, Kumar S, He YQ, Halpert JR. An electrostatically driven conformational transition is involved in the mechanisms of substrate binding and cooperativity in cytochrome P450eryF. Biochemistry. 2004;43:6475–6485. doi: 10.1021/bi036260l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davydov DR, Kumar S, Halpert JR. Allosteric mechanisms in P450eryF probed with 1-pyrenebutanol, a novel fluorescent substrate. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;294:806–812. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00565-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan KK, Liu H, Halpert JR. Homotropic versus heterotopic cooperativity of cytochrome P450eryF: A substrate oxidation and spectral titration study. Drug Metab. Disp. 2003;31:356–359. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.4.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts AG, Diaz MD, Lampe JN, Shireman LM, Grinstead JS, Dabrowski MJ, Pearson JT, Bowman MK, Atkins WM, Campbell AP. NMR studies of ligand binding to P450(ery)F provides insight into the mechanism of cooperativity. Biochemistry. 2006;45:1673–1684. doi: 10.1021/bi0518895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schoch GA, Yano JK, Wester MR, Griffin KJ, Stout CD, Johnson EF. Structure of human microsomal cytochrome P4502C8 - Evidence for a peripheral fatty acid binding site. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:9497–9503. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312516200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams PA, Cosme J, Vinkovic DM, Ward A, Angove HC, Day PJ, Vonrhein C, Tickle IJ, Jhoti H. Crystal structures of human cytochrome P450 3A4 bound to metyrapone and progesterone. Science. 2004;305:683–686. doi: 10.1126/science.1099736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schrag ML, Wienkers LC. Topological alteration of the CYP3A4 active site by the divalent cation Mg2+ Drug Metab. Disp. 2000;28:1198–1201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsalkova TN, Davydova NE, Halpert JR, Davydov DR. Mechanism of interactions of alpha-naphthoflavone with cytochrome P450 3A4 explored with an engineered enzyme bearing a fluorescent probe. Biochemistry. 2007;46:106–119. doi: 10.1021/bi061944p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atkins WM, Wang RW, Lu AYH. Allosteric behavior in cytochrome P450-dependent in vitro drug-drug interactions: A prospective based on conformational dynamics. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2001;14:338–347. doi: 10.1021/tx0002132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao YH, Halpert JR. Structure-function analysis of cytochrornes P4502B. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1770:402–412. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ekroos M, Sjögren T. Structural basis for ligand promiscuity in cytochrome P450 3A4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:13684–13687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603236103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott EE, White MA, He YA, Johnson EF, Stout CD, Halpert JR. Structure of mammalian cytochrome P450 2B4 complexed with 4-(4-chlorophenyl)imidazole at 1.9-A resolution: insight into the range of P450 conformations and the coordination of redox partner binding. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:27294–27301. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403349200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davydov DR, Halpert JR, Renaud JP, Hui Bon Hoa G. Conformational heterogeneity of cytochrome P450 3A4 revealed by high pressure spectroscopy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;312:121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.09.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davydov DR, Baas BJ, Sligar SG, Halpert JR. Allosteric mechanisms in cytochrome P450 3A4 studied by high-pressure spectroscopy: Pivotal role of substrate-induced changes in the accessibility and degree of hydration of the heme pocket. Biochemistry. 2007;46:7852–7864. doi: 10.1021/bi602400y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Griffin BW, Peterson JA. Pseudomonas putida cytochrome P-450. The effect of complexes of the ferric hemeprotein on the relaxation of solvent water protons. J. Biol. Chem. 1975;16:6445–6051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Philson SB, Debrunner PG, Schmidt PG, Gunsalus IC. The effect of cytochrome P-450cam on the NMR relaxation rate of water protons. J. Biol. Chem. 1979;20:173–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poulos TL, Howard AJ. Crystal structures of metyrapone- and phenylimidazole-inhibited complexes of cytochrome P-450cam. Biochemistry. 1987;26:8165–8174. doi: 10.1021/bi00399a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loida PJ, Sligar SG. Molecular recognition in cytochrome P-450: mechanism for the control of uncoupling reactions. Biochemistry. 1993;32:11530–11538. doi: 10.1021/bi00094a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haines DC, Tomchick DR, Machius M, Peterson JA. Pivotal role of water in the mechanism of P450BM-3. Biochemistry. 2001;40:13456–13465. doi: 10.1021/bi011197q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davydov DR, Hui Bon Hoa G, Peterson JA. Dynamics of protein-bound water in the heme domain of P450BM3 studied by high-pressure spectroscopy: Comparison with P450cam and P450 2B4. Biochemistry. 1999;38:751–761. doi: 10.1021/bi981397a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Helms V, Wade RC. Thermodynamics of water mediating protein-ligand interactions in cytochrome P450cam: a molecular dynamics study. Biophys J. 1995;69:810–824. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)79955-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bancel F, Bec N, Ebel C, Lange R. A central role for water in the control of the spin state of cytochrome P-450(scc) Eur. J. Biochem. 1997;250:276–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.0276a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wade RC. Solvation of the active site of cytochrome P450-cam. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 1990;4:199–204. doi: 10.1007/BF00125318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Helms V, Deprez E, Gill E, Barret C, Hui Bon Hoa G, Wade RC. Improved binding of cytochrome P450cam substrate analogues designed to fill extra space in the substrate binding pocket. Biochemistry. 1996;35:1485–1499. doi: 10.1021/bi951817l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fisher MT, Scarlata SF, Sligar SG. High-pressure investigations of cytochrome P-450 spin and substrate binding equilibria. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1985;240:456–463. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hui Bon Hoa G, Marden MC. The pressure dependence of the spin equilibrium in camphor-bound ferric cytochrome P-450. Eur. J. Biochem. 1982;124:311–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb06593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marden MC, Hoa GH. P-450 binding to substrates camphor and linalool versus pressure. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1987;253:100–107. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(87)90642-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davydov DR, Deprez E, Hui Bon Hoa G, Knyushko TV, Kuznetsova GP, Koen YM, Archakovz AI. High-pressure induced transitions in microsomal cytochrome P450 2B4 in solution - evidence for conformational Inhomogeneity in the oligomers. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1995;320:330–344. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(95)90017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Di Primo C, Deprez E, Hui Bon Hoa G, Douzou P. Antagonistic effects of hydrostatic pressure and osmotic pressure on cytochrome P-450(cam) spin transition. Biophys J. 1995;68:2056–2061. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80384-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anzenbacher P, Bec N, Hudecek J, Lange R, Anzenbacherova E. High conformational stability of cytochrome P-450 1A2. Evidence from UV absorption spectra. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 1998;63:441–448. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davydov DR, Petushkova NA, Archakov AI, Hui Bon Hoa G. Stabilization of P450 2B4 by its association with P450 1A2 revealed by high-pressure spectroscopy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;276:1005–1012. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Di Primo C, Hui Bon Hoa G, Douzou P, Sligar SG. Heme-pocket-hydration change during the inactivation of cytochrome P-450camphor by hydrostatic pressure. Eur. J. Biochem. 1992;209:583–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davydov DR, Knyushko TV, Hui Bon Hoa G. High pressure induced inactivation of ferrous cytochrome P-450 LM2 (2B4) CO complex: evidence for the presence of two conformers in the oligomer. Biochem.Biophys.Res.Commun. 1992;188:216–221. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)92372-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tauc P, Mateo CR, Brochon JC. Investigation of the effect of high hydrostatic pressure on proteins and lipidic membranes by dynamic fluorescence spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1595:103–115. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(01)00338-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khan KK, Halpert J. 7-benzyloxyquinoline oxidation by P450eryF A245T: Finding of a new fluorescent substrate probe. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2002;15:806–814. doi: 10.1021/tx0200010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brackman U. Lambdachrome Laser Dyes. 3-rd ed. Goettingen: Lambda Physik AG; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Renaud JP, Davydov DR, Heirwegh KPM, Mansuy D, Hui Bon Hoa G. Thermodynamic studies of substrate binding and spin transitions in human cytochrome P450 3A4 expressed in yeast microsomes. Biochem. J. 1996;319:675–681. doi: 10.1042/bj3190675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Segel IH. Enzyme Kinetics: Behavior and Analysis of Rapid Equilibrium and Steady-State Enzyme Systems. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hui Bon Hoa G, McLean MA, Sligar SG. High pressure, a tool for exploring heme protein active sites. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1595:297–308. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(01)00352-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weber G. Protein Interactions. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lampe JN, Fernandez C, Nath A, Atkins WM. Nile red is a fluorescent allosteric substrate of cytochrome P450 3A4. Biochemistry. 2008;47:509–516. doi: 10.1021/bi7013807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fernando H, Halpert JR, Davydov DR. Resolution of multiple substrate binding sites in cytochrome P450 3A4: the stoichiometry of the enzyme-substrate complexes probed by FRET and Job's titration. Biochemistry. 2006;45:4199–4209. doi: 10.1021/bi052491b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hui Bon Hoa G, Di Primo C, Dondaine I, Sligar SG, Gunsalus IC, Douzou P. Conformational changes of cytochromes P-450cam and P-450lin induced by high pressure. Biochemistry. 1989;28:651–656. doi: 10.1021/bi00428a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Davydov DR, Fernando H, Halpert JR. Variable path length and counter-flow continuous variation methods for the study of the formation of high-affinity complexes by absorbance spectroscopy. An application to the studies of substrate binding in cytochrome P450. Biophys. Chem. 2006;123:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kurganov BI. Allosteric Enzymes. Kinetic Behavior. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1982. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The application of principal component analysis to the analysis of the series of fluorescence decay curves used in this study is described and illustrated in Supporting Information, which is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.