Abstract

The physiologic importance of GABAergic neurotransmission in hypothalamic neurocircuits is unknown. To examine the importance of GABA release from agouti-related protein (AgRP) neurons (which also release AgRP and neuropeptide Y), we generated mice with an AgRP neuron–specific deletion of vesicular GABA transporter. These mice are lean, resistant to obesity and have an attenuated hyperphagic response to ghrelin. Thus, GABA release from AgRP neurons is important in regulating energy balance.

AgRP neurons release AgRP, neuropeptide Y (NPY) and GABA and are important in regulating body weight1-3. However, the deletion of AgRP and/or NPY has little effect on body weight4. This raises the possibility that the release of GABA may be important2,5. A direct GABAergic action from AgRP neurons to pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons has been suggested to mediate the ability of leptin to indirectly excite POMC neurons2,5-7. However, because of the lack of methodological approaches, the physiologic effect of GABAergic neurotransmission in the hypothalamus is unknown.

Vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT, encoded by Vgat, also known as Slc32a1) is required for presynaptic release of GABA8. To disrupt GABA release in a neuron-specific manner, we generated Vgatflox/flox mice (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Methods online). To ensure the specificity of cre expression in AgRP neurons, we generated Agrp-Ires-cre knockin mice (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Methods). We confirmed the specificity of Cre activity by immunostaining for green fluorescent protein (GFP) in Agrp-Ires-cre mice that were crossed with mice bearing a Cre-dependent GFP reporter transgene (Z/EG mice)9 (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Methods). We generated mice that lack GABA release from AgRP neurons by crossing Vgatflox/flox mice (129, C57BL/6 background) with Agrp-Ires-cre mice (129, C57BL/6 background). The study subjects were littermate offspring of Vgatflox/flox mice and Agrp-Ires-cre; Vgatflox/flox mice. Deletion of VGAT in AgRP neurons by Cre recombinase was confirmed in Agrp-Ires-cre; Vgatflox/flox;; Z/EG mice (Supplementary Fig. 1 online). To establish that GABA release from AgRP neurons was disrupted, we recorded inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs, measuring GABA-mediated current) in cultured AgRP neurons with autaptic synapses10. We detected IPSCs in 7 out of the 13 AgRP neurons recorded from control mice, but only detected IPSCs in 0 out of 12 AgRP neurons derived from Agrp-Ires-cre; Vgatflox/flox mice (Fig. 1d). Thus, deletion of Vgat prevents the synaptic release of GABA from AgRP neurons. We observed no difference in AgRP immunostaining patterns in Agrp-Ires-cre; Vgatflox/flox mice, suggesting that there was no alteration in AgRP neuron development resulting from the disruption of GABA release (Supplementary Fig. 2 online).

Figure 1.

Generation of mice lacking GABA release from AgRP neurons. All animal care and experimental procedures were approved by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. (a) Schematic diagram of the wild-type (WT) Vgat allele, the Vgatflox/flox allele and the allele inactivated by Cre-mediated recombination. (b) Schematic diagram of the Agrp-Ires-cre allele. (c) The expression of Cre activity in the arcuate nucleus of Agrp-Ires-cre mice crossed with Cre-dependent [Au: Please clarify, is Z/EG the name of the mouse strain or is it the name of the transgene? I was unable to find Z/EG listed as a gene in Mouse Genomic Informatics or in Entrez Gene. Z/EG is a abbreviation of LacZ/EGFP, which is a line of transgenic mice. In these mice, the expression of LacZ/EGFP will be turned on with the presence of Cre recombinase. ] GFP reporter Z/EG mice (immunostaining for GFP). (d) Summary of recordings for IPSCs and excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) from cultured AgRP neurons with autaptic synapses. To permit identification of AgRP neurons, we bred Z/EG GFP reporter mice to Vgatflox/flox and Agrp-Ires-cre; Vgatflox/flox mice. 3V, the third ventricle. Scale bar represents 10 μM.

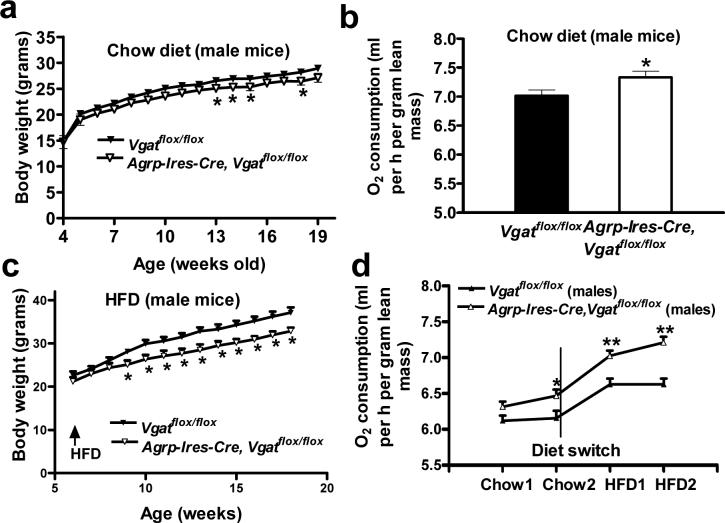

Agrp-Ires-cre; Vgatflox/flox mice showed reduced body weight on chow diet in both males (Fig. 2a) and females (Supplementary Fig. 3 online). We did not observe a change in food intake in 10−12-week-old male mice (Supplementary Fig. 3) or in 16−17-week-old male mice (data not shown); however, O2 consumption was significantly increased (P < 0.05; Fig. 2b). In addition, these mice showed increased locomotor activity and reduced respiration exchange ratios (Supplementary Fig. 3). When placed on a high fat diet (HFD), male Agrp-Ires-cre; Vgatflox/flox mice had reduced body weight gain compared with controls (Fig. 2c), indicating that they had a resistance to diet-induced obesity (DIO) (Fig. 3a,c). Body composition analysis revealed that reduced body weight gain was solely because of reduced fat accumulation (Supplementary Fig. 3). The resistance to DIO was not the result of reduced food intake (Supplementary Fig. 3), which suggests that it was caused primarily by increased energy expenditure. To test this directly, we measured O2 consumption in male mice during the transition from chow to HFD feeding. We observed a much greater increase in O2 consumption in Agrp-Ires-cre; Vgatflox/flox mice (Fig. 2d), indicating that these animals have increased HFD-induced thermogenesis.

Figure 2.

Energy homeostasis in Agrp-Ires-cre; Vgatflox/flox mice. (a) Body weight of Vgatflox/flox mice and Agrp-Ires-cre; Vgatflox/flox mice (males, n = 14−19 animals). (b) O2 consumption of Vgatflox/flox mice (7.02 ± 0.09 ml O2 per h per g of lean mass) and Agrp-Ires-cre; Vgatflox/flox mice (7.33 ± 0.10) (n = 8 each). O2 consumption was measured using the Columbus Instruments Comprehensive Lab Animal Monitoring System and was normalized to lean mass. Lean mass was measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. (c) Body weight of Vgatflox/flox mice and Agrp-Ires-cre; Vgatflox/flox mice during HFD feeding (n = 8 each). (d) O2 consumption of both Vgatflox/flox mice and Agrp-Ires-cre; Vgatflox/flox mice during the transition from chow to HFD feeding (n = 6−9). O2 consumption was normalized to lean mass. The O2 consumption rates of Vgatflox/flox mice on 2 consecutive days on chow diet were 6.12 ± 0.07 and 6.16 ± 0.10 ml O2 per h per g, respectively, and those on the following 2 consecutive days for HFD were 6.63 ± 0.08 and 6.63 ± 0.08 ml O2 per h per g, respectively. The O2 consumption rates of Agrp-Ires-cre; Vgatflox/flox mice on 2 consecutive days on chow were 6.31 ± 0.07 and 6.46 ± 0.09 ml O2 per h per g, respectively, and on 2 consecutive days on HFD were 7.02 ± 0.07 and 7.21 ± 0.08 ml O2 per h per g, respectively. The net average increment of O2 consumption in response to HFD was 0.45 ml O2 per h per g in Vgatflox/flox mice versus 0.70 ml O2 per h per g in Agrp-Ires-cre; Vgatflox/flox mice. Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. * P < 0.05.

Figure 3.

Ghrelin-induced food intake in Vgatflox/flox mice and Agrp-Ires-cre; Vgatflox/flox mice. (a) Food intake in 0.5-, 2- and 4-h time periods in male Vgatflox/flox mice and Agrp-Ires-cre; Vgatflox/flox mice after intraperitoneal administration of saline (S) or ghrelin (G, 500 μg per kg of body weight, n = 6−10). For the 2-h period, food intake increased from 0.22 ± 0.05 g to 0.46 ± 0.06 g by ghrelin in Vgatflox/flox mice versus 0.22 ± 0.05 g to 0.25 ± 0.05 g by ghrelin in Agrp-Ires-cre; Vgatflox/flox mice. (b) Food intake in females using the same conditions as in a. For the 2-h period, food intake increased from 0.14 ± 0.04 g to 0.61 ± 0.06 g by ghrelin in Vgatflox/flox mice versus 0.11 ± 0.05 g to 0.31 ± 0.05 g by ghrelin in Agrp-Ires-cre; Vgatflox/flox mice. (c) IPSCs in POMC neurons of Vgatflox/flox mice and Agrp-Ires-cre; Vgatflox/flox mice. To permit identification of POMC neurons, Pomc-gfp transgenic mice were bred to Vgatflox/flox and Agrp-Ires-cre; Vgatflox/flox mice. Postsynaptic currents were recoded from GFP neurons in brain slices and IPSCs were isolated by eliminating glutamate-mediated EPSCs using d-APV and CNQX. (d) Summary of IPSC recordings in c (n = 8 each). Firing rate was increased from 1.44 ± 0.33 Hz to 2.60 ± 0.26 Hz by ghrelin in Vgatflox/flox mice versus 1.04 ± 0.33 Hz to 1.23 ± 0.36 Hz in Agrp-Ires-cre; Vgatflox/flox mice. d-APV and CNQX are glutamate receptor antagonists. Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. * P < 0.05.

AgRP neurons are a major target of ghrelin with respect to its effect on food intake11. Ghrelin increased food intake in Vgatflox/flox control mice, as previously reported11. This effect, however, was greatly attenuated in Agrp-Ires-cre; Vgatflox/flox mice in both males (Fig. 3a) and females (Fig. 3b), indicating that GABA release from AgRP neurons is an important mediator of ghrelin's stimulatory effect on food intake. To examine the possible effects on POMC neurons, we recorded inhibitory postsynaptic potentials in POMC neurons (Supplementary Methods). We visualized POMC neurons using a Pomc-gfp bacterial artificial chromosome transgene12. Ghrelin significantly increased (p<0.05) the frequency of inhibitory postsynaptic potentials recorded in POMC neurons of Vgatflox/flox control mice, as previously reported13. This increase, however, was absent in Agrp-Ires-cre; Vgatflox/flox mice (Fig. 3c,d), indicating that ghrelin-stimulated GABAergic input to POMC neurons is mediated by AgRP neurons.

Agrp-Ires-cre; Vgatflox/flox mice are lean and resistant to DIO because of increased energy expenditure, suggesting that the normal function of GABA release from AgRP neurons is to restrain energy expenditure. This effect could be the result of GABAergic-mediated inhibition of POMC neurons, which are known to have a stimulatory effect on thermogenesis14. Notably, it appears that release of GABA from AgRP neurons, as opposed to AgRP and NPY4, is required for the regulation of energy expenditure. The alteration in body weight resulting from the disruption of GABA release from AgRP neurons is consistent with the 11% reduction in body weight and the lack of changes in feeding behavior of mice with neonatal ablation of AgRP neurons3. The marked attenuation of ghrelin-stimulated food intake in Agrp-Ires-cre; Vgatflox/flox mice underscores the importance of GABA release from AgRP neurons in the orexigenic action of ghrelin, which is consistent with results from mice with AgRP neuron ablation15. The attenuation of ghrelin-stimulated food intake in Agrp-Ires-cre; Vgatflox/flox mice is similar to that in mice with deleted AgRP or NPY4, suggesting that multiple signaling pathways downstream of AgRP neurons mediate ghrelin's orexigenic action. The absence of ghrelin-stimulated increases in IPSCs in POMC neurons of Agrp-Ires-cre; Vgatflox/flox mice is consistent with POMC neurons mediating, indirectly via AgRP neurons, this orexigenic effect. In summary, our study demonstrates that GABA release from AgRP neurons is required for the regulation of energy expenditure and for ghrelin-stimulated food intake. We demonstrate the usefulness of neuron-specific deletion of VGAT for studying the physiologic functions of GABAergic neurotransmission.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by US National Institutes of Health grants (RO1 DK071051 and PO1 DK56116 to B.B.L.; RO1 DK071320, RO1 DK53301 and PO1 DK56116 to J.K.E.) and the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Transgenic Facility, which is supported by the Boston Obesity Nutrition Research Center (P30 DK046200) and the Boston Area Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center (P30 DK057521). Q.T. is the recipient of a Pilot and Feasibility Award from the US National Institutes of Health–funded Boston Obesity Nutrition Research Center (P30 DK046200) and a Young Investigator Award from the North American Association for the Study of Obesity.

References

- 1.Bewick GA, et al. FASEB J. 2005;19:1680–1682. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3434fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gropp E, et al. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:1289–1291. doi: 10.1038/nn1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luquet S, Perez FA, Hnasko TS, Palmiter RD. Science. 2005;310:683–685. doi: 10.1126/science.1115524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qian S, et al. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:5027–5035. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.14.5027-5035.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flier JS. Cell Metab. 2006;3:83–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balthasar N, et al. Neuron. 2004;42:983–991. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cowley MA, et al. Nature. 2001;411:480–484. doi: 10.1038/35078085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wojcik SM, et al. Neuron. 2006;50:575–587. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Novak A, Guo C, Yang W, Nagy A, Lobe CG. Genesis. 2000;28:147–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tong Q, et al. Cell Metab. 2007;5:383–393. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen HY, et al. Endocrinology. 2004;145:2607–2612. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parton LE, et al. Nature. 2007;449:228–232. doi: 10.1038/nature06098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cowley MA, et al. Neuron. 2003;37:649–661. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00063-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cone RD. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:571–578. doi: 10.1038/nn1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luquet S, Phillips CT, Palmiter RD. Peptides. 2007;28:214–225. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.