Abstract

First proposed by Mueller, the theory of the “rally effect” predicts that public support for government officials will increase when an event occurs that (1) is international; (2) involves the United States; and (3) is specific, dramatic, and sharply focused (Mueller 1973, p. 209). Using the natural experiment of a large (N=15,127) survey of young adults ages 18-27 that was in the field during the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, we confirm the existence of a rally effect on trust in government as well as its subsequent decay. We then use a predictive modeling approach to investigate individual-level dynamics of rallying around the flag and anti-rallying in the face of the national threat. By disaggregating predictors of rallying, we demonstrate remarkably different patterns of response to the attacks based on sex and, particularly, race. The results confirm expectations of national threat inciting a rally effect, but indicate that the dynamics of this rally effect are complex and race and gender-dependent. The article offers previously-unavailable insights into the dynamics of rallying and trust in government.

Keywords: trust, September 11, rally effect, race, gender

Extant theory and research suggest that, in the face of a broadly-experienced national threat, citizens' trust in the federal government tends to increase (Doty, Peterson, and Winter 1997; Feldman and Stenner 1991; Sales 1972, 1973)--a version of the so-called “rally effect” (Mueller 1973). This effect has been demonstrated empirically in the case of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks by repeated cross-sectional studies (Gaines 2002; Newport 2001; Chanley 2002; Schubert, Stewart, and Curran 2002). We examine the rally effect more closely using an unusual data source and methodological approach. We use predictive modeling to estimate individuals' probability of rallying around the federal government in the wake of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks using a large, nationally-representative survey of young adults that was in the field at the time of the attacks. This approach allows us to identify the kinds of people who tend to rally in response to perceived threats. Our data also allow us to focus on an often neglected population: young adults, whose attitudes toward government and citizenship may be in formation and for whom historical memory may be particularly acute (Schuman and Scott 1989). We find remarkable gender and race differences in pre-9/11 trust in government as well as in responses to the 9/11 attacks. We also document the presence and dynamics of an anti-rally effect, in which a sizeable proportion of the population (roughly 25%) reduced trust in government in the wake of the September 11 attacks.

The Theory of Rally Effects

First proposed by Mueller (1973), rally effects are theorized to occur when an event takes place that (1) is international in scope; (2) involves the United States;1 and (3) is specific, dramatic, and sharply focused (Mueller 1973, p. 209). Rally effects have been documented in numerous postwar cases (Brody and Shapiro 1991), including World War II (Kriner 2006), the assassination attempt on President Reagan (Ostrom and Simon 1989), the Persian Gulf War (Parker 1995), and more. Although some studies (e.g., Conover and Sapiro 1993; Gilens 1988) have suggested that women tend to rally less than men, Clarke et al. (2004, p. 46) found no such effect. Indeed, they found that women's presidential approval rose more than that of men in the wake of the 1991 Gulf War.

Edwards and Swenson (1997), analyzing panel data on the rally effect following president Clinton's 1993 attack on the Iraqi intelligence headquarters, found no significant gender effect on rallying, and did not test for the effects of race. They argue that the rally effect essentially pushes citizens already somewhat inclined to support the president into full support. Building upon that analysis, Tallman (2007) argues that an important source of the 2001 rally was the existence of a public relatively ready to be rallied: “the relatively high percentage of slight disapprovers available to Bush offered him a uniquely large pool of candidates to rally in the wake of an obvious rally point” (73).

Trust in Government

Trust in government follows similar patterns to support for government with regards to rally effects, including, importantly, the September 11, 2001, attacks (Hetherington and Nelson 2003; Schubert, Stewart, and Curran 2002). Controversy over the meaning and effects of trust in government occupies much of the recent research in the field (Levi and Stoker 2000). Importantly, many studies of voting behavior find no relationship between trust in government and the relatively routine (Perrin 2006, 26-27) activity of voting (Citrin 1974; Rosenstone and Hansen 1993). However, trust (or distrust) in government may promote various other kinds of participation, including protest, letters to representatives and editors, and other publicly-oriented methods (Rosenau 1974). Furthermore, trust and distrust in government may affect citizens' views on policy, thereby shaping government action (Hetherington 2005).

The overall trend in trust in the federal government shows relatively high levels until the Watergate scandal, beginning at 76% in 1965 and dropping to roughly 50% in the mid-1970s. Trust in the federal government continued its decline to a low of 25% in 1981, when it began a short recovery to a post-Watergate high of 44% in 1985. It dropped again to 21% in 1995, then recovered to the same 44% mark in 2001. Polling data from late September, 2001, show a clear rally effect: a 20-point jump in trust in the federal government after the 9/11 attacks (see, e.g., Chanley 2002, p. 472, Hibbing 2002, p. 318, and Gaines 2002, p. 535), a finding we replicate here using new data.

Levels of trust in government are generally found to be sensitive to the performance of the current administration; the economic cycle; media coverage (but see Gross et al. 2004); and other concerns, attitudes, and anxieties (Oskamp and Schultz 2005, p. 302; Marcus, Neuman, and MacKuen 2000).2 Individual-level predictors of trust in government include race (Banducci, Donovan, and Karp 2004; Parker 2003; Mangum 2003), sex (Lawless 2004), and individual social capital, conceptualized as civic engagement and interpersonal trust (Keele 2007). However, most research on trust in government concentrates on effects on the aggregate levels of trust at given time points, not on individual-level trust. Hetherington (2005, p. 17) asserts that demographic factors explain little of the variation in trust in government, but there remain significant differences, particularly based on race and gender, in our data as well as elsewhere in the literature. Parker (2003), for example, shows significant race differences in the meaning of patriotism, which may underly differences in rallying behavior. To be sure, demographics does not explain away differences in trust in government, but there is enough race and gender variation in trust in government to warrant further investigation into the dynamics of such trust. The research we report here is an exploratory project to document race, sex, and ideological effects on changes in trust in government in the wake of the September 11, 2001, attacks.

The September 11, 2001, Attacks

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, are well-known. A group of 19 hijackers took control of four transcontinental flights and crashed them into symbolically and materially important sites, killing over 2,800 people. The twin towers of New York's World Trade Center were destroyed, and the Pentagon was severely damaged. Media coverage--television, radio, print, and internet--of the attacks was immediate and ubiquitous, insuring that essentially the entire country was aware of the situation and its implications. This was the first foreign attack on U.S. soil in nearly 60 years. As portrayed in the media and perceived by most citizens, it was international in character, directly involved the United States, and was specific, dramatic, and sharply focused—the hallmarks of a rally event. These factors made the level of perceived threat in the U.S. population after September 11 significantly greater than it had been before (Huddy et al. 200b, 420).

In the months following the attacks, there was much discussion of how the events would affect American public opinion and political culture. Among the most visible considerations of the political-cultural fallout of September 11 was the work of Robert Putnam (Putnam 2002). Putnam claimed that September 11 provided the focus he had previously argued would be needed for a renewal of citizenship in the face of declining social capital (Putnam, 2000, 402-03). By contrast, theories of authoritarianism predict that, in the face of threat, authoritarian sentiment should grow (Adorno et al., 1950). Perrin (2005) showed that both pro- and anti-authoritarian sentiment in political discourse, measured through published letters to the editor, increased in the months following the attacks. Trust in government is conceptually related to both of these claims. To the extent that trust in government is related to generalized trust (Cook 2003), Putnam's suggestion that the attacks increased community trust would be expected to “spill over” into increased trust in government as well. More pessimistically, one of the dimensions of Adorno et al.'s “F scale” of authoritarian tendencies is “Authoritarian submission: a submissive, uncritical attitude toward idealized moral authorities of the ingroup” (Adorno et al. 1950: 248-250). Thus, citizens who increased their authoritarianism in the wake of the attacks would increase trust in government as a result of increased deference to authority.

Using the same data we analyze here, Ford et al. (2003) found evidence only of “transient” psychological symptoms and noted that the only durable effect of exposure to news of the attacks discernible in these data was significantly higher levels of trust in government at all levels (federal, state, and local). In a retrospective, longitudinal study, Silver et al. (2002) confirmed that psychological symptoms declined over a six-month time period, but they remained elevated, particularly among those who coped using “disengaging” strategies (giving up, denial, and self distraction). Noting the important theoretical difference between personal and national threat, Huddy et al. (2002a) show that different kinds of perceived threats in a sample of New York-area respondents evoked different protective beliefs and responses.

The September 11 attacks left American politics dramatically changed, too. Memories of the bitter, divisive fight over the Florida election less than a year earlier (Perrin et al. 2006) were all but erased as Americans united behind President George W. Bush. Bush's approval ratings jumped nearly overnight (Gaines 2002; Newport 2001), and he earned high marks from across the political spectrum for his leadership during and immediately after the crisis. At the same time, knowledge of a broad range of political facts jumped dramatically (Prior 2002), and trust in the federal government jumped as well (Gaines 2002; Chanley 2002). However, this “rally effect” was by no means monolithic. Rather, while overall levels of trust increased, significant numbers of citizens actually decreased their trust in government following the attacks.

The extant theory and research on rally effects suggest numerous reasons why different groups of citizens might respond differently to a major rally event like the September 11 attacks. Different groups may begin with different orientations toward government in general (Parker 2003). These groups may perceive a rally event differently (Tallman 2007; Edwards and Swenson 1997) and may take different principles, emotions, and experiences into account when updating their evaluations of leaders and governments. Citizens already relatively inclined to trust the government may increase that trust, whereas those more inclined to be suspicious may decrease trust (Perrin 2005). In short, personal and political identity along with life experiences probably influence whether, how much, and in what direction an individual adjusts trust in government in the wake of a rally event. In this paper we examine the dynamics of the September 11 rally and its anti-rally counterpart. We look, in particular, at the correlates of changing trust in government. Using a predictive modeling approach, we evaluate race, gender, and ideological effects on the likelihood of increasing or decreasing trust in government in the wake of the attacks.

The September 11 attacks constitute a particularly difficult case for our claim that the dynamics of public opinion—and, in particular, trust in government—are complex and multivalent. Because of the widespread knowledge of the attacks and the homogeneous character of the news and information about them, many commentators have noted that this event should be relatively homogenizing (Putnam 2002; Stein 2003; Kellner 2002). The fact that we find substantial variation in the direction, degree, and predictors of rallying in the wake of such an event suggests that the aggregate direction of public reaction to events conveying more internal social division (see, e.g., Wagner-Pacifici and Schwartz 1991) probably masks even more heterogeneity.

Data and Analysis

The data for this study come from Wave III of the National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent Health (AddHealth), a multi-wave, national in-person interview study of young adults who were in grades 7-12 in 1994-95 (Bearman, Jones, and Udry 2002; Resnick, Bearman, Blum, et al. 1997). Wave III, in which respondents were ages 18-27, was in progress when the September 11 attacks took place, so the data constitute a natural experiment: there is no reason to expect systematic differences between the pre- and post-attack interviewees. Indeed, our examination of the frequency of relevant variables between the pre- and post-attack interviewees found few significant differences (table 1).3 Although AddHealth is not primarily a public opinion survey, Wave III contained new questions about trust in local, state, and federal government, allowing us to use it for this analysis.

Table 1. Pre- and post-9/11 descriptive values and t-tests for difference of means.

| Pre-9/11 | Post-9/11 | Change | Pr(|T| > |t|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (%) | 42.00 | 48.60 | 6.60 | 0.000 *** |

| Education (mean years) | 13.23 | 13.17 | -0.06 | 0.126 |

| Military Background (%) | 4.23 | 5.13 | 0.90 | 0.032 * |

| Employed full-time (%) | 78.55 | 79.84 | 1.29 | 0.103 |

| Full-time student (%) | 32.65 | 26.95 | -5.70 | 0.000 *** |

| Race (%) | ||||

| White | 66.63 | 67.26 | 0.63 | 0.492 |

| Black | 24.06 | 22.71 | -1.35 | 0.101 |

| American Indian or Native American | 5.36 | 5.53 | 0.17 | 0.694 |

| Asian American or Pacific Islander | 8.24 | 8.42 | 0.18 | 0.741 |

| Religious Service Attendance (%) | ||||

| Never | 24.83 | 27.25 | 2.42 | 0.005 ** |

| A few times in past year | 25.16 | 26.31 | 1.15 | 0.183 |

| Several times in past year | 11.83 | 12.46 | 0.63 | 0.327 |

| Once a month | 6.95 | 6.79 | -0.16 | 0.745 |

| 2 or 3 times a month | 10.83 | 9.84 | -0.99 | 0.094 |

| Once a week | 13.33 | 12.08 | -1.25 | 0.054 |

| More than once a week | 7.07 | 5.27 | -1.80 | 0.000 *** |

| Political Orientation (%) | ||||

| Don't know | 6.60 | 7.60 | 1.00 | 0.051 |

| Very conservative | 3.00 | 2.80 | -0.20 | 0.630 |

| Conservative | 18.27 | 18.44 | 0.17 | 0.821 |

| Middle of the road | 53.22 | 52.64 | -0.58 | 0.561 |

| Liberal | 17.02 | 16.52 | -0.50 | 0.498 |

| Very liberal | 1.86 | 1.91 | 0.05 | 0.863 |

| Life Satisfaction (%) | ||||

| Very satisfied | 37.97 | 36.05 | -1.92 | 0.042 * |

| Satisfied | 46.32 | 46.96 | 0.64 | 0.513 |

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 11.40 | 12.90 | 1.50 | 0.021 * |

| Dissatisfied | 3.71 | 3.47 | -0.24 | 0.499 |

| Very dissatisfied | 0.60 | 0.62 | 0.02 | 0.888 |

Wave III of the AddHealth survey consisted of a pilot survey fielded between April 2 and April 30, 2001 (N=219) and the main survey, fielded between July 21, 2001, and April 22, 2002 (N=14,978). Respondents were young adults between the ages of 18 and 28 at the time of the interview; their average age was 22. The respondents took part in a wide-ranging in-person interview. After obtaining written consent, interviews lasting approximately 90 minutes were conducted in homes or other locations of the respondents' choice using Computer-Assisted Personal Interview and Computer-Assisted Self-Interview technologies. The response rate was 76%.

In Wave III, three trust in government questions were asked. The series began with the question: “How much do you agree or disagree with each of the following statements?” and continued with:

I trust the federal government.

I trust my state government.

I trust my local government.

For each, respondents chose among “strongly agree”, “agree”, “neither agree nor disagree”, “disagree”, and “strongly disagree.”4

As the extant literature on trust in government suggests, trust in the three levels of government is highly correlated. Trust in the federal government is correlated with trust in state government at 0.854, and with trust in local government at 0.754. Trust in state government is correlated with trust in local government at 0.836. These correlations remained virtually unchanged throughout the survey period, including pre- and post-9/11 interviews. We therefore concentrate our analysis on trust in the federal government.

Methods

We adapt a predictive modeling strategy to the problem of identifying increases in trust in government following the 9/11 attacks. We begin by using the pre-attack interviews (including the spring, 2001, pilot interviews and the regular study interviews carried out between July 21 and September 10, 2001) to develop a model predicting trust in government before exposure to the attacks. We then use that model to predict “naïve trust” in government for those subjects who were interviewed after the attacks: the level of trust in government we would expect them to report had they been interviewed before the attacks. We then compute a difference between naïve and reported trust in government for the post-attack sample. We consider a respondent's trust in government to have “changed” when her reported trust falls outside the 95% confidence interval for her naïve trust. Those whose reported trust in government is above the upper bound of that confidence interval are the “ralliers”; those who are below its lower bound are the “anti-ralliers”; and those within the confidence interval are the “non-ralliers.” Table 3 contains descriptive statistics on the frequency of rallying and anti-rallying.

Table 3. Rally and anti-rally percentages by sex/race group.

| Rally | Anti-rally | Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Combined | 44.83 | 25.61 | 1.75 |

| White male | 51.14 | 21.04 | 2.43 |

| Black male | 33.77 | 25.31 | 1.33 |

| White female | 51.01 | 26.13 | 1.95 |

| Black female | 38.80 | 24.26 | 1.6 |

This predictive modeling approach allows us more directly to model change in trust in government as a result of exposure to the September 11 attacks, rather than predicting overall propensity to trust as we did with the pre-9/11 sample. This is distinct from predicting trust itself in the overall sample, such as by estimating a regression equation including exposure to the attacks as an independent variable. By isolating the exposure group we are able to demonstrate the specific effect of exposure in each group.

Predicting pre-9/11 trust in government

We began by selecting the respondents who were interviewed between the beginning of Wave III and September 10 (N=3,345).5 To model “naïve,” pre-9/11 trust, we used linear regression. Although this involved treating the ordinal variable of trust in government as continuous (ranging from 1, “strongly disagree”, to 5, “strongly agree” that “I trust the federal government”), the technique was justified in allowing us to predict more fine-grained average levels of trust in government than a logistic regression would have allowed. As a check on this decision, we ran similar models using ordered logit; the results were substantively similar (not shown, but available upon request).

We included the following as possible predictors of trust in government:

Sex (male/female)

Race (white, black/African American, American Indian/Native American, or Asian American/Pacific Islander)

Years of education completed, since education is an important predictor of a variety of forms of political thought and behavior (see, e.g., Nie, Junn, and Stehlik-Barry 1996)

Community service work performed both voluntarily (“voluntary service”) and as a requirement of school or the legal system (“involuntary service”), as a measure of the civic engagement dimension of “social capital.” Our data contain no suitable measure of the interpersonal trust dimension (Keele 2007: 243-44).6

Military background (having ever served in the military reserves or the active-duty military), since we theorize that military experience may be either an indicator or a cause of trust in government: the federal government in particular, but also potentially government in general.

Full-time employment (35 hours a week or more), since trust in institutions in general may be related to economic integration

Status as full-time students, since individuals in an educational setting often experience major events differently

Attendance at religious services (never; a few times in the past year; several times in the past year; once a month; 2-3 times a month; once a week; or more than once a week), since religious attendance predicts a variety of moral, social, and political outcomes (Perrin 2006; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady 1996), and also increases general trust (Guiso, Sapienza, and Zingales 2002; Welch et al. 2004)

Liberal or Conservative affiliation since, as a general orientation toward government, liberals should be more trusting than conservatives, being philosophically inclined to believe government should intervene in the economy and society. On the other hand, the majority of incumbent officeholders at the federal level—and at the state and local level in New York—were Republican at the time of the survey, and the controversial Florida election of 2000 was very recent (Perrin et al. 2006; Price and Romantan 2004). If respondents interpret trust as support for officeholders, we would therefore expect conservatives to exhibit greater trust in government. We test political orientation (very conservative, conservative, middle of the road, liberal, very liberal, or “don't know”) as a predictor of trust.

Life Satisfaction, since individuals' overall level of satisfaction with life is a highly stable, reliable predictor of generalized trust (Caplow 1982; Diener et al. 1985). We theorize that life satisfaction may be an underlying factor in individuals' trust in government because it has been shown to be related to confidence in institutions (Lipset and Schneider 1987). While others have used economic satisfaction as a proxy for life satisfaction (Cook and Gronke 2005, 793), respondents in our data were asked to rate their overall satisfaction with life (very satisfied, satisfied, neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, dissatisfied, or very dissatisfied).

Because the dynamics underlying trust in government may be significantly different for citizens of different race/sex groups (see Parker 2003), we begin with a single, combined model, but continue by carrying out separate regressions for men and women in each major racial grouping in the data. The linear regressions were carried out using Stata SE 9.2 for Unix and the survey regression routines (svy: regress). Table 2 contains the results of those models predicting trust in the federal government among those interviewed before the September 11 attacks.

Table 2. Coefficients predicting trust in federal government among pre -9/11 interviewees (OLS regression).

| Predictor | Combined | WM | BM | WF | BF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 2.535 *** | 1.765 *** | 3.260 *** | 2.630 *** | 3.173 *** |

| Male | -0.140 * | ||||

| Education | 0.024 * | 0.073 ** | -0.025 | 0.013 | -0.074 |

| Voluntary Service | 0.038 | 0.052 | 0.307 | 0.020 | 0.122 |

| Involuntary Service | -0.042 | -0.186 | 0.277 | -0.041 | 0.001 |

| Military | 0.016 | 0.106 | 0.067 | -0.009 | -0.572 |

| Full-Time Work | -0.056 | -0.111 | -0.239 | -0.089 | 0.102 |

| Full-Time Student | -0.059 | -0.028 | -0.134 | -0.078 | -0.153 |

| White | --- | ||||

| Black | -0.139 * | ||||

| Native American | -0.050 | ||||

| Asian | 0.279 ** | ||||

| Church: Never | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Church: A Few times | 0.112 | 0.013 | -0.218 | 0.220 ** | 0.126 |

| Church: Several times | 0.159 * | 0.123 | 0.564 | 0.110 | 0.254 |

| Church: Once a month | 0.093 | -0.187 | -0.472 | 0.340 * | 0.234 |

| Church: 2-3×/month | 0.189 * | -0.008 | 0.286 | 0.268 * | 0.144 |

| Church: Once a week | 0.189 * | 0.005 | 0.045 | 0.331 ** | 0.350 |

| Church: > 1/week | 0.240 ** | 0.034 | 0.059 | 0.374 ** | 0.126 |

| Very conservative | 0.119 | 0.329 | -0.633 | 0.142 | 0.391 |

| Conservative | 0.140 * | 0.215 * | 0.260 | -0.032 | 0.395 ** |

| Moderate | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Liberal | -0.211 ** | -0.234 * | -0.681 * | -0.206 * | 0.227 |

| Very Liberal | -0.668 *** | -1.283 *** | -0.905 * | -0.757 *** | 0.394 |

| Politics: Don't know | -0.010 | -0.183 | 0.325 | -0.023 | 0.108 |

| Very Satisfied | 0.334 *** | 0.390 * | 0.094 | 0.462 *** | 0.487 ** |

| Satisfied | 0.207 * | 0.388 * | 0.086 | 0.221 * | 0.442 ** |

| Neither Sat nor Dissat | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Dissatisfied | -0.308 * | -0.519 | -0.037 | -0.237 | -0.002 |

| Very Dissatisfied | -0.698 ** | -0.317 | -0.763 | 0.167 | -0.617 |

The combined model shows that predictors of trust in government were generally consistent with the literature, suggesting that (1) the trust-in-government questions on the AddHealth survey we used measure a similar construct to questions on other commonly-used batteries; and (2) trust in government follows similar patterns in young adults to those among the general population. Men were significantly less likely to trust government than were women, and African Americans reported significantly lower levels of trust than did whites. 7 Education shows a small, but significant, positive effect on trust. Community service work, whether voluntary or involuntary, had no significant effect on trust in government; neither did military experience, work status, or student status.

Religious participation was, overall, a significant and positive predictor of trust in the federal government. More liberal respondents were less likely to trust government, and moderate conservatives were more likely to do so: an interesting finding in itself in the context of Hetherington's (2005) argument that conservative social policy results from low levels of trust in government. Liberals were likely reacting to the current officeholders and the bitter memory of the 2000 election more than to the institutions of government (Citrin 1974; Lipset and Schneider 1983; see also Brooks and Cheng 2001, Perrin et al. 2006).

Overall satisfaction with life was a significant predictor of trust in government. Those who were “very satisfied” or just “satisfied” with life were more trusting of government than those who were neither satisfied nor dissatisfied; similarly, those who were “very dissatisfied” or just “dissatisfied” were less likely to trust government. These findings are in line with previously reported findings that positive environments (Oskamp and Schultz 2005) and feelings toward public actors (Marcus, Miller, and MacKuen 2000) bolster trust in government.

Given the significant effects of race and sex on trust in government, we carried out separate regression models for men and women within the black and white racial groups in the data. These analyses allow us to identify differences in the predictors of trust in government among members of these different groups. The results are indeed remarkable. Besides the fact that the constants are widely varied—which represents the varying levels of trust in government explained by the groups themselves—the analyses show that religious effects are quite important for white women, but (with isolated exceptions) not particularly important for other groups. In fact, if white women are excluded from the analysis, religious service attendance is not a significant predictor of pre-9/11 trust in government (results not shown, but available from the authors). Though liberals were generally less likely to trust the government, and those more satisfied with their lives more so, these effects, too, differed based on race and sex groups, with black men's trust more sensitive to their political views but the trust of white men and both black and white women more sensitive to life satisfaction. These findings may reflect different underlying ideas about government; see Parker (2003).

Calculating expected (“naïve”) trust in government

For the 11,782 respondents who were interviewed between September 12, 2001, and April 22, 2002, we used the results of the race- and sex-differentiated pre-9/11 models to predict post-9/11 trust in government. We calculated linear predictions and standard errors for post-9/11 interviewees based on the appropriate pre-9/11 linear models. We refer to these calculated scores as “naive trust,” since we theorize that they are the levels of trust we would have expected had the post-9/11 respondents been interviewed prior to 9/11—that is, had they been naïve with respect to the September 11 attacks.

We interpret the difference between predicted and reported trust as the change in trust in government attributable to the attacks (Table 3). Post-9/11 respondents were assigned to three categories for each level of government: those whose trust increased (the ralliers); those whose trust decreased (the anti-ralliers); and those whose trust remained as predicted (the non-ralliers). To insure that the error resulting from the prediction models is accounted for in assigning respondents to categories, we used a 95% confidence interval around the naïve trust score to infer change. Finally, we developed ordered logit models (Powers and Xie 2000, 212-222) predicting increased and decreased trust in government as a result of exposure to the attacks.

Results

The Aggregate Rally Effect: Patterns of Trust in Government Over Time

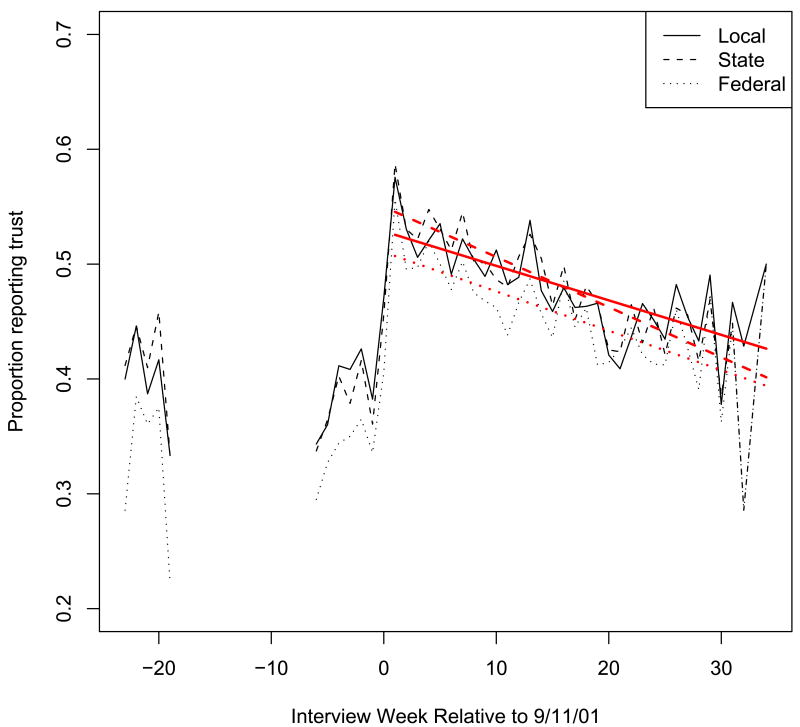

Figure 1 shows aggregate levels of reported trust in federal, state, and local government for the full course of Wave III of AddHealth. The section at the left of the graph represents data from the spring, 2001, preliminary field test, which contained all the questions we analyze.

Figure 1. Trust in Local, State, and Federal Government.

As we demonstrated above, trust in the federal government is highly correlated with trust in local and state governments. Trust in the federal government is somewhat lower than that in local and state governments, both before and after the attacks. All three levels of government, though, experienced a substantial increase in trust immediately after the attacks; the proportion of respondents reporting trust jumped from just under 40% to nearly 60% before declining over the remainder of the survey field period.

Who Rallied?

Table 3 contains the mean change in trust in government for the entire sample and for the race- and sex-differentiated subsamples. As expected, rallying is far more prevalent than anti-rallying. Just under 45% of the post-9/11 interviewees reported significantly higher trust in government than was predicted based on the pre-9/11 models, while only just over 25% reported significantly lower trust. For no race/sex group was anti-rallying more likely than rallying, although the ratio ranges from a low of 1.33 for black men to a high of 2.43 for white men.

Table 4 contains the results of ordered logistic regressions predicting significant differences between naïve and reported trust in government among post-9/11 interviewees. We present adjusted odds ratios for equations whose dependent variable is a three-level construct: -1 for anti-rallying, 0 for non-rallying, and 1 for rallying. Thus a significant odds ratio less than 1 implies both an increased likelihood of anti-rallying and a decreased likelihood of rallying. Similarly, a significant odds ratio greater than 1 implies an increased likelihood of rallying and a decreased likelihood of anti-rallying.

Table 4. Adjusted odds-ratios for increased/decreased trust in government post-9/11 (ordered logistic regression).

| Predictor | Combined | WM | BM | WF | BF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weeks since 9/11 | 0.988 *** | 0.989 * | 1.004 | 0.982 *** | 0.991 |

| Male | 1.118 * | ||||

| Education | 1.057 *** | 1.038 | 1.039 | 1.073 ** | 1.099 * |

| Voluntary Service | 0.905 | 0.974 | 0.630 | 0.971 | 0.614 ** |

| Involuntary Service | 0.980 | 0.950 | 0.486 ** | 1.216 | 0.576 * |

| Military | 1.309 * | 1.285 | 1.443 | 1.481 | 1.375 |

| Full-Time Work | 1.169 * | 1.120 | 2.327 *** | 1.158 | 1.056 |

| Full-Time Student | 1.221 ** | 1.200 | 1.259 | 1.430 *** | 1.177 |

| White | --- | ||||

| Black | 0.697 *** | ||||

| Native American | 0.518 *** | ||||

| Asian | 0.637 *** | ||||

| Church: Never | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Church: A Few times | 1.095 | 1.327 * | 1.181 | 0.716 ** | 1.273 |

| Church: Several times | 1.114 | 1.122 | 0.466 ** | 1.174 | 1.285 |

| Church: Once a month | 1.408 ** | 2.179 ** | 2.180 ** | 0.995 | 0.711 |

| Church: 2-3×/month | 1.075 | 1.451 * | 0.853 | 0.875 | 0.710 |

| Church: Once a week | 1.386 ** | 1.794 ** | 2.288 *** | 1.205 | 0.851 |

| Church: > 1/week | 0.858 | 1.175 | 0.503 * | 0.738 | 0.800 |

| Very conservative | 0.775 | 0.522 * | 1.466 | 0.667 * | 0.955 |

| Conservative | 1.251 ** | 1.244 | 1.100 | 1.316 * | 0.987 |

| Moderate | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Liberal | 1.061 | 0.990 | 2.282 *** | 1.042 | 0.617 * |

| Very Liberal | 1.233 | 1.304 | 1.113 | 1.162 | 0.664 |

| Politics: Don't know | 1.044 | 1.019 | 0.677 | 1.010 | 1.425 |

| Very Satisfied | 1.211 * | 1.219 | 2.648 ** | 0.989 | 0.803 |

| Satisfied | 1.122 | 1.066 | 1.643 | 1.074 | 0.635 * |

| Neither Sat nor Disat | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Dissatisfied | 1.157 | 1.466 | 0.658 | 1.247 | 0.692 |

| Very Dissatisfied | 1.015 | 0.658 | 2.485 * | 0.602 | 1.720 |

As Figure 1 suggests, the number of weeks since the attacks was a significant, negative predictor of changed trust in government. This finding confirms that, as time progressed beyond the attacks, their effect on trust in government lessened. However, this effect is not consistent across racial groups. The decline function is significant for white respondents, but not for black ones.8 African Americans' reactions to the attacks appear less oriented to trust in government than those of whites; they were less likely to alter trust in government in the wake of the attacks, and their reported trust changed less as the event receded into memory. We consider this evidence that black respondents were less susceptible to the rally effect in general: they increased trust less and returned to “normal” more slowly. This is one facet of the impact of race on how citizens make decisions about trust in government.

Overall, African Americans were significantly less likely to rally than were whites. Education is a strong predictor of rallying in the wake of the terror attacks in the combined model. Again, though, further inspection shows that the effect of education is significant for women (both black and white) but not for men. Having a military background significantly predicted rallying, as did being a full- time employee or student.

Community service also had different effects by race. Having participated in involuntary community service work did not predict changed trust for white respondents, but was a significant predictor of reduced trust for black respondents, while having participated in voluntary community service predicted reduced trust only among black females

The effect of religious service attendance differed in interesting ways across race/sex groups. Compared to those who reported “never” attending religious services, attendance at several levels was a significant predictor of rallying for men—the opposite of the effect on naïve trust in government, in which it was women for whom religious service attendance was more significant. For white women, periodic attendance was a significant predictor of anti-rallying. 9

Overall, the data show a difference in the effect of political ideology on rallying from that on naïve trust in government—another effect contingent on combinations of demographic and political characteristics of individual citizens. Before the attacks, it was liberals who were less likely to trust government. Following the attacks, by contrast, white liberals were generally no more or less likely than moderates to rally, and there were contrasting effects between liberal African American men and liberal African American women in comparison with their moderate counterparts. Liberal African American women were more likely to anti-rally in the wake of the attacks than were their moderate counterparts, while liberal African American men were more than twice as likely as moderate African American men to rally. Within the “very conservative” category, male and female white respondents show significant odds ratios below 1, which indicates a tendency to anti-rally, while those white females self-reporting as merely “conservative” were generally significantly likelier to increase trust. Gender, race, and political identification thus interact in complex ways: we see different impacts of the attacks between liberal black men and liberal black women, but also between “conservative” and “very conservative” white women.

Exposure to the 9/11 attacks may have an opposite effect as well: convincing some citizens to reduce trust in government even when the overall trend is to increase it (see Perrin 2005). Consistent with the picture of a broad-based rally effect, though, relatively few characteristics significantly predicted anti-rallying. The strongest of these effects is race itself: African Americans were significantly more likely to anti-rally than whites. “Very conservative” whites were also more likely to do so.

Moderate conservatives were more likely to rally around the federal government. By contrast, whites who are “very conservative” were more likely to decrease trust. Those who said they don't know their political orientation were indistinguishable from middle-of-the-road respondents.

Life satisfaction was not a strong predictor of rallying in general; those who were “very satisfied” with life were more likely to rally than those neither satisfied nor dissatisfied. This effect is more pronounced among black men. Just reporting “satisfied” predicted anti-rallying among black women, but not among other groups.

Limitations

There are some important limitations to our analysis. Most importantly, AddHealth is targeted toward adolescent health; respondents, therefore, were all young adults between the ages of 18 and 28. It is reasonable to think that young adults' political cognition might differ from that of older adults. However, within our sample, respondent's age is not a significant predictor of trust in any of the three levels of government. Neither is respondent's age when dichotomized at age 21 or 25. The fact that respondents do not report different levels of trust in government as they approach adulthood suggests that young adults' reactions were similar to those of older adults. Also, the fact that our measures of trust in government followed the patterns reported in other studies of the post-9/11 rally (e.g., Chanley 2002) suggests that our sample is not significantly different from the broader adult population. Still, our analysis must be considered an in-depth look at a younger adult population that is often under-studied. This population may be particularly important to consider, as the years of transition from adolescence into adulthood are an important time in which durable attitudes and opinions are formed (Schuman 1989).

Our assignment of respondents to the rally and anti-rally categories relies upon the validity of the initial models we used to predict naïve trust in government. In general, our initial model reflects the available literature on individual citizens' trust in government. Finally, exposure to the September 11 attacks could affect features we treat as independent variables: particularly political orientation, life satisfaction, and religious service attendance. For example, a person might become more conservative in the wake of the attacks, or might begin attending religious services more frequently. We cannot rule out these effects because of the cross-sectional nature of our data; however, we would expect such effects to decrease the significance of any relationships we found, so we do not consider this a threat to the validity of the study. Furthermore, table 1 shows remarkable similarity on all of these dimensions between the pre- and post-attack samples. We conducted separate analyses including only those independent variables not vulnerable to changing in the wake of the attacks and found no significant differences in the results (not presented here but available on request from the authors).

Because AddHealth is a longitudinal study, it would be possible to incorporate data from waves I and II to predict trust in government at wave III. Wave I data were gathered in 1994 and 1995, Wave II in 1996, and Wave III data were gathered in 2001 and 2002 (Harris et al. 2003). We elected not to take this path because in the five years since the prior wave, many respondents' life circumstances may have changed dramatically, particularly since the respondents are young adults often involved in major life changes. For example, church attendance may have changed between Waves II and III if individuals moved from living in their parents' homes to living in college dormitories or living independently. In fact, some scholars argue that the developmental period known as “adolescence” ends at age 18, at which point a distinct developmental period known as “emerging adulthood” begins, lasting into the mid-20s. This stage of life often includes shifts in worldview and a great deal of important identity exploration and development (see Arnett 2000). Because of the gap in time between Waves II and III during a period when such changes in life circumstances are occurring, we opted to exclude data from prior waves.

Conclusion

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, were an important watershed for many reasons, one of which was their impact on American citizens' levels of trust in their government. Trust in all levels of government increased immediately following the attacks, and took roughly six months of turbulent national and world events to return to levels similar to those prior to the attacks.

African-Americans, women, and those with lower levels of education were less likely to rally than were whites, men, and those with higher education. However, neither education nor race significantly predicted the likelihood of anti-rallying, with some isolated exceptions. This suggests that these groups' trust in government was less sensitive to exposure to the attacks than was the trust in government of white, male, and more highly educated groups. Our data allow us to examine these population-specific shifts in trust in government, thereby telling us more about differences in groups' perceptions of, and relationships to, the government.

To our knowledge, our analysis is the only one to use data from a large-scale, nationally-representative survey to capture respondents' views of government and society both immediately before and after the September 11 attacks. Our analysis provides a unique view of the dynamics of trust in government among young adults in response to a major event of national scope. Most importantly, our findings demonstrate that the dynamics of change in trust in government are complicated and often strongly affected by the demographic, political, and social psychological characteristics of citizens reacting to their environments. Referring to the “rally effect” is justified as an aggregate concept, but different kinds of citizens participate differently (or not at all) in the rally.

These conclusions suggest that the idea of aggregate trust in government—as well as aggregate measures such as presidential and congressional approval—should be understood as aggregations of potentially multivalent views espoused by varying individuals and groups of respondents. Our research provides a first step toward understanding the dynamics of public opinion by demonstrating that citizens react even to a large-scale, potentially homogenizing event (Stein 2003; Kellner 2002) in complex and differentiated ways. It is likely that the dynamics of other public opinion mainstays are similarly multivalent and deserve to be disaggregated in order better to understand the cognitive and psychological patterns that underlie them.

Acknowledgments

We especially acknowledge Carol Ford, who hatched the idea for this study and helped ensure its completion. In addition, we are grateful to Larry Griffin, Guang Guo, Heather Krull, Eliana Perrin, and Catherine R. Zimmer for assistance in the project. This research uses data from Add Health, a program project designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris, and funded by a grant P01-HD31921 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 17 other agencies. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design of Add Health. Persons interested in obtaining data files from Add Health should contact Add Health, Carolina Population Center, 123 W. Franklin Street, Chapel Hill, NC 27516-2524 (addhealth@unc.edu). Any errors are the authors' responsibility.

Footnotes

The assumption, of course, is that this is support for, or trust in, the U.S. government by U.S. citizens, though there is evidence of similar effects elsewhere (Lai and Reiter 2005).

Trust in local and state government, in general, has been consistently higher than that in the federal government since the late 1970s (Blendon et al., 1997), but they are also highly correlated: those who exhibit trust in local and state government are also likely to trust federal government (Rahn and Rudolph 2002; Jennings 1998; Macedo et al. 2005, ch. 3; Jennings 1998; Brooks and Cheng 2001; Smith 1995).

The exceptions are that men and those with military backgrounds were more likely to be interviewed after the attacks and students were more likely to be interviewed before them. There was a slight increase in those reporting never attending religious services, and an accompanying decrease in those reporting attending more than once a week, after the attacks. Finally those interviewed after the attacks were less likely to be “very satisfied” with life and similarly likely to be “neither satisfied nor dissatisfied.”

While these questions are not exactly the same as the standard NES trust-in-government measure, the wording is quite similar and can be expected to measure similar constructs. The fact that aggregate trust levels parallel those measured by the NES lend support to this claim. The questions we use are closer to the NES questions than to the other major measures of trust in government: the GSS measures of confidence in leaders and institutions and Cook and Gronke's measures on trust and cynicism (Cook and Gronke 2005).

Any interviews carried out on September 11, 2001 were dropped from the data.

This construct is quite different from what sociologists typically understand as social capital (see Portes 1998; Lin 2001): resources available through social networks. These may result from civic engagement, but are not identical to it. Furthermore, it is unclear why interpersonal trust should be understood as a dimension, instead of an outcome, of social capital. However, since the literature on trust in government has conceptualized social capital as civic engagement plus interpersonal trust, we follow that lead to avoid confusion.

Asians were also significantly more likely to rally, as shown in Table 2. However, subsample sizes for Asians and Native Americans are too small to make further analysis reliable. We therefore do not present them here, but limited results are available upon request from the authors.

Further analysis of the data suggests that this effect is relatively robust, i.e., that black respondents were less likely to change their trust in government as a response to the attacks.

Effects of religious service attendance are notoriously difficult to pin down (see, e.g., Hadaway and Marler 2005). We carried out similar models using a three-level measure of attendance (“never,” “sometimes,” “weekly or more often”) and found similar effects to those reported here.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adorno T, Frenkel-Brunswik E, Levinson DJ, Sanford RN. The Authoritarian Personality. Harper & Bros.; New York: 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging Adulthood: A Theory of Development from the Late Teens Through the Early Twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55(5):469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banducci SA, Donovan T, Karp JA. Minority Representation, Empowerment, and Participation. Journal of Politics. 2004 May;66(2):534–556. [Google Scholar]

- Bearman PS, Jones J, Udry JR. The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Research Design. Available at: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.html.

- Blendon RJ, Benson JM, Morin R, Altman DE, Brodie M, Brossard M, James M. Changing Attitudes in America. In: Nye Joseph S, Zelikow Philip D, King David C., editors. Why People Don't Trust Government. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1997. pp. 205–216. [Google Scholar]

- Brody Richard A, Shapiro Catherine R. The Rally Phenomenon in Public Opinion. In: Brody Richard A., editor. Assessing the President: The Media, Elite Opinion, and Public Support. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 1991. pp. 45–78. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks C, Cheng S. Declining Government Confidence and Policy Preferences in the U.S.: Devolution, Regime Effects, or Symbolic Change? Social Forces. 2001;79(4):1343–1375. [Google Scholar]

- Caplow T. Decades of Public Opinion: Comparing NORC and Middletown data. Public Opinion. 1982;5(5):30–31. [Google Scholar]

- Chanley VA. Trust in Government in the Aftermath of 9/11: Determinants and Consequences. Political Psychology. 2002;23(3):469–483. [Google Scholar]

- Citrin J. Comment: The Political Relevance of Trust in Government. American Political Science Review. 1974;68:973–988. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke HD, Stewart MC, Ault M, Elliott E. Men, Women and the Dynamics of Presidential Approval. British Journal of Political Science. 2004;35:31–51. [Google Scholar]

- Conover PJ, Sapiro V. Gender, Feminist Consciousness, and War. American Journal of Political Science. 1993;37:1079–1099. [Google Scholar]

- Cook KS. Trust in Society. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cook TE, Gronke P. The Skeptical American: Revisiting the Meanings of Trust in Government and Confidence in Institutions. Journal of Politics. 2005;67(3):784. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985;49(1):71. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty RM, Peterson BE, Winter DG. Threat and Authoritarianism in the United States, 1978-1987. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61(4):629–640. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.4.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards G, Swenson T. Who Rallies? The Anatomy of a Rally Event. Journal of Politics. 1997 February;59(1):200–212. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman S, Stenner K. Perceived Threat and Authoritarianism. Political Psychology. 1997;18(4):741–770. [Google Scholar]

- Ford CA, Udry JR, Gleiter K, Chantala K. Reactions of young adults to September 11, 2001. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2003;157:572–578. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.6.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaines BJ. Where's the Rally? Approval and Trust of the President, Cabinet, Congress, and Government Since September 11. PS: Political Science & Politics. 2002;35(3):531–536. [Google Scholar]

- Gilens M. Gender and Support for Reagan: A Comprehensive Model of Presidential Approval. American Journal of Political Science. 1988;32:19–49. [Google Scholar]

- Gross K, Aday S, Brewer PR. A Panel Study of Media Effects on Political and Social Trust After September 11, 2001. Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics. 2004;9(4):49–73. [Google Scholar]

- Guiso L, Sapienza P, Zingales L. NBER Working Paper 9237. Cambridge, Mass: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2002. People's Opium? Religion and Economic Attitudes. Available http://www.nber.org/papers/w9237. [Google Scholar]

- Hadaway CK, Marler PL. How Many Americans Attend Worship Each Week? An Alternative Approach to Measurement. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2005;44(3):307–322. [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Florey F, Tabor J, Bearman PS, Jones J, Udry JR. The National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent Health: Research Design. 2003 [WWW document]. URL: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.

- Hetherington MJ. Why Trust Matters: Declining Political Trust and the Demise of American Liberalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington MJ, Nelson M. Anatomy of a Rally Effect: George W. Bush and the War on Terrorism. PS: Political Science and Politics. 2003;36(1):37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbing JR. The People's Craving for Unselfish Government. In: Norrander Barbara, Wilcox Clyde., editors. Understanding Public Opinion. Washington: CQ Press; 2002. pp. 301–318. [Google Scholar]

- Huddy L, Feldman S, Capelos T, Provost C. The consequences of terrorism: Disentangling the effects of personal and national threat. Political Psychology. 2002a;23(3):485–509. [Google Scholar]

- Huddy L, Khatib N, Capelos T. The polls-trends: Reactions to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2002b;66:418–450. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings MK. Political Trust and the Roots of Devolution. In: Braithwaite Valerie, Levi Margaret., editors. Trust and Governance. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1988. pp. 218–243. [Google Scholar]

- Keele L. The Authorities Really Do Matter: Party Control and Trust in Government. Journal of Politics. 2005;67(3):873–886. [Google Scholar]

- Keele L. Social Capital and the Dynamics of Trust in Government. American Journal of Political Science. 2007;51(2):241–254. [Google Scholar]

- Kellner D. September 11, Social Theory and Democratic Politics. Theory, Culture & Society. 2002;19(4):147–159. [Google Scholar]

- Kriner DL. Examining Variance in Presidential Approval: The Case of FDR in World War II. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2006;70(1):23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lai B, Reiter D. Rally 'Round the Union Jack? Public Opinion and the Use of Force in the United Kingdom, 1948-2001. International Studies Quarterly. 2005;49(2):255–272. [Google Scholar]

- Lawless JL. Politics of Presence? Congresswomen and Symbolic Representation. Political Research Quarterly. 2004 March;51(1):81–99. [Google Scholar]

- Levi M, Stoker L. Political Trust and Trustworthiness. Annual Review of Political Science. 2000;3:475–507. [Google Scholar]

- Lin N. Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lipset SM, Schneider W. The confidence gap : business, labor, and government in the public mind. New York: Free Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Macedo S, editor. Democracy at Risk: How Political Choices Undermine Citizen Participation, and What We Can Do About It. Washington: Brookings Institution Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mangum M. Psychological Involvement and Black Voter Turnout. Political Research Quarterly. 2003 March;56(1):41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus GE, Neuman WR, MacKuen M. Affective Intelligence and Political Judgment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Miller AH. Political Issues and Trust in Government: 1964-1970. American Political Science Review. 1974;68:951–972. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller JE. War, Presidents, & Public Opinion. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Newport F. Trust in Government Increases Sharply in Wake of Terrorist Attacks. Gallup Poll Monthly. 2001 October [Google Scholar]

- Oskamp S, Schutz PW. Attitudes and Opinions. Third. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom CW, Jr, Simon DM. The Man in the Teflon Suit? The Environmental Connection, Political Drama, and Popular Support in the Reagan Presidency. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1989;53(3):353–387. [Google Scholar]

- Parker CS. Group-based assessments on the meaning of patriotism. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association; Philadelphia. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Parker SL. Toward an Understanding of ‘Rally’ Effects: Public Opinion in the Persian Gulf War. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1995;59(4):526–546. [Google Scholar]

- Perrin AJ. National Threat and Political Culture: Authoritarianism, Anti-Authoritarianism, and the September 11 Attacks. Political Psychology. 2005;26(2):167–194. [Google Scholar]

- Perrin AJ. Citizen Speak: The Democratic Imagination in American Life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Perrin AJ, Wagner-Pacifici R, Hirschfeld L, Wilker S. Contest Time: Time, Territory, and Representation in the Postmodern Electoral Crisis. Theory and Society. 2006;35:351–391. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A. Social Capital: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology. Annual Review of Sociology. 1998;24:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Powers DA, Xie Y. Statistical Methods for Categorical Data Analysis. San Diego: Academic Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Price V, Romantan A. Confidence in Institutions Before, During, and After ‘Indecision 2000’. Journal of Politics. 2004;66(3):939–956. [Google Scholar]

- Prior M. Political Knowledge after September 11. PS: Political Science & Politics 35. 2002;3:523–530. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam RD. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. Simon & Schuster; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam RD. Bowling together. The American Prospect. 2002 February 11; [Google Scholar]

- Rahn WM, Rudolph TJ. Trust in Local Governments. In: Norrander Barbara, Wilcox Clyde., editors. Understanding Public Opinion. Washington: CQ Press; 2002. pp. 281–300. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Peter S, Bearman PS, Robert W, Blum RW, et al. Protecting Adolescents from Harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. JAMA. 1997;278:823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenau JN. Citizenship between elections; an inquiry into the mobilizable American. New York: Free Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstone SJ, Hansen JM. Mobilization, Participation, and Democracy in America. New York: MacMillan; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sales SM. Economic Threat as a Determinant of Conversion Rates in Authoritarian and Nonauthoritarian Churches. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1972;23(3):420–428. doi: 10.1037/h0033157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sales SM. Threat as a Factor in Authoritarianism: An Analysis of Archival Data. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1973;28(1):44–57. doi: 10.1037/h0035588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert JN, Stewart PA, Curran MA. A Defining Presidential Moment: 9/11 and the Rally Effect. Political Psychology. 2002;23(3):559–583. [Google Scholar]

- Schuman H, Scott J. Generations and Collective Memories. American Sociological Review. 1989 June;54(3):359–381. [Google Scholar]

- Silver RC, Holman EA, McIntosh DN, Poulin P, Gil-Rivas V. Nationwide longitudinal study of psychological responses to September 11. JAMA. 2002;288(10):1235–1244. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.10.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TW. How Much Government? Public Support for Public Spending, 1973-1994. The Public Perspective. 1995:1–3. https://www.journalmanager.org/polpsych/reviews/5528-2-321-47054a54a7f75.docApril-May.

- Stein HF. Days of Awe: September 11, 2001 and its Cultural Psychodynamics. JPCS: Journal for the Psychoanalysis of Culture & Society. 2003 Fall;8(2):187–199. [Google Scholar]

- Szerszynski BB. Risk and Trust: The Performative Dimension. Environmental Values. 1999;8:239–252. [Google Scholar]

- Sztompka P. Trust: A Sociological Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tallman M. Patriotism, or Bread and Circuses? A Brief Discussion of the September-October 2001 Rally 'Round the Flag Effect. Critique: A Worldwide Journal of Politics. 2007 Spring [Google Scholar]

- Tourangeau R, Rips LJ, Rasinski K. The Psychology of Survey Response. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Verba S, Schlozman KL, Brady H. Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner-Pacifici RE, Schwartz B. The Vietnam Veterans Memorial: Commemorating a Difficult Past. American Journal of Sociology. 1991 September;97(2):376. [Google Scholar]

- Welch Michael R, Sikkink David, Sartain Eric, Carolyn Bond. Trust in God and Trust in Man: The Ambivalent Role of Religion in Shaping Dimensions of Social Trust. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2004;43(3):317–343. [Google Scholar]

- Wynne B. May the Sheep Safely Graze? A Reflexive View of the Expert-Lay Knowledge Divide. In: Lash, Szerszynski, Wynne, editors. Risk, Environment, and Modernity: Towards a New Ecology. London: Sage; 1996. pp. 44–83. [Google Scholar]