Abstract

The protein, dysferlin, mediates sarcolemmal repair in vitro, implicating defective membrane repair in dysferlinopathies. To study the role of dysferlin in vivo, we assessed contractile function, sarcolemmal integrity, and myogenesis before and after injury from large-strain lengthening contractions in dysferlin-null and control mice. We report that: dysferlin-null muscles produce higher contractile torque, are equally susceptible to initial injury but recover from injury more slowly. Two weeks after injury, control muscles retain fluorescein dextran and do not show myogenesis. Dysferlin-null muscles do not retain fluorescein dextran, and show necrosis followed by myogenesis. Our data indicate that recovery of control muscles from injury primarily involves sarcolemmal repair whereas recovery of dysferlin-null muscles primarily involves myogenesis without repair and long-term survival of myofibers.

Keywords: Dysferlin, Muscular dystrophy, Sarcolemmal repair, Muscle injury, Myogenesis, Necrosis, Inflammation

Introduction

Dysferlin is a ∼230 kDa protein of the sarcolemma and cytoplasmic vesicles of skeletal muscle [1,2]. Mutations in the dysferlin gene are linked to 3 muscular dystrophies (dysferlinopathies) that differ in their clinical presentation: limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 2B (LGMD2B) [3], Miyoshi myopathy (MM) [4], and distal anterior compartment myopathy [4]. Naturally occurring animal models of dysferlin deficiency, such as the A/J and SJL/J strains of mice, as well as dysferlin–null mice generated by homologous recombination, have been studied to elucidate the role of dysferlin in skeletal muscle [2,5,6]. Myofibers isolated from dysferlin-null mice and studied in vitro are defective in sarcolemmal repair, suggesting that this may underlie pathogenesis in dysferlinopathies [2], but a role for dysferlin in the repair of the sarcolemma in vivo has not been reported.

Physiological injuries to skeletal muscle frequently involve lengthening (“eccentric”) contractions that can damage the sarcolemma, compromising the survival of injured myofibers [7]. Lengthening contractions, such as those induced by downhill running, are often used to study sarcolemmal stability [2] and the mechanisms underlying the recovery of normal muscular function [8]. However, recovery from injury induced by large-strain lengthening contractions has seldom been used to study the survival of injured myofibers or the mechanisms underlying it. We recently showed that in vivo recovery of contractile function in the tibialis anterior (TA) muscle of the rat, following injury to the ankle dorsiflexors (DFs) from large-strain lengthening contractions, involves long-term repair of damaged sarcolemma and survival of injured fibers without significant levels of myogenesis, whereas recovery from 150 small-strain lengthening contractions requires myogenesis without long-term survival or sarcolemmal repair [7]. A similar large-strain injury (LSI) can be induced in the ankle DFs of the mouse by 15 large-strain lengthening contractions, which produce an immediate loss of contractile function followed by recovery over 3-7 days even when satellite cells are ablated by X-irradiation before injury (not shown). Here we show that recovery of control muscles in vivo is associated with membrane repair and long-term survival of injured myofibers without myogenesis, whereas recovery of dysferlin-null muscle occurs via myogenesis, without significant long-term survival of injured fibers. As a result, dysferlin-null muscle recovers more slowly from injury than control muscle.

Materials and Methods

We induced injury and studied recovery of function in the whole ankle DF group and then examined TA muscles, which account for most of the torque generated by this muscle group [9]. Induction of injury, measurement of contractile function, and collection of tissues were performed under general anesthesia obtained by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine and xylazine (40 and 10 mg/kg, respectively).

Animals

We studied 3 inbred strains of mice, A/J, A/WySnJ and C57Bl/6J (n = 40 per strain; male, 12-14 wks of age; Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME). A/J mice lack dysferlin and so model human dysferlinopathies [5]. As A/J mice first develop a pronounced dystrophic phenotype around 5 months of age, the mice we studied only showed a mild phenotype (see results). A/WySnJ mice, which express dysferlin but otherwise share a genetic background with A/J mice [5], served as controls. C57Bl/6J mice were used as additional controls because they express normal amounts of dysferlin [5], have no documented skeletal muscle abnormalities, and are widely used to study contraction-induced injury [10,11]. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

Injury model and assessment of contractile function

We used 15 lengthening contractions to yield ∼40% loss of function of the DFs. For each lengthening contraction, DFs were tetanically stimulated for 300ms; 150ms after onset of stimulation, the ankle was plantarflexed from 90-170° at an angular velocity of 900°/s. A 3-min rest between successive lengthening contractions minimized the effect of fatigue. We measured maximal tetanic torque of the DFs before and 10 min after injury, and then 7 and 14 d later, to assess contractile function. The rig used for injury-induction and measurement of ankle DF torque has been described [7,12,13]. Isolated contractions of the ankle DFs were elicited by depolarizing the peroneal nerve transcutaneously with a bipolar electrode (BS4 50-6824, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) placed over the head of the fibula. Impulses of 0.1 ms duration were generated by an S48 square pulse stimulator (Grass Instruments, West Warwick, RI); a PSIU6 stimulation isolation unit (Grass Instruments) between the electrode and stimulator limited current amplitude to 15 mA. Pulse amplitude was adjusted to obtain maximal twitch torque, and 300 ms trains of varying pulse frequencies were used to plot a torque-frequency curve. Maximal fused tetany was obtained at ≥ 80 Hz for all 3 strains of mice studied.

Membrane repair

Fluorescein dextran (FDx; 10 kD, anionic, lysine fixable; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), injected intraperitoneally (5 mg/ml in PBS, 0.01 ml/g body weight) 1 hr before injury, was used to assess membrane damage and resealing. FDx enters the cytoplasm of myofibers with sarcolemmal damage and becomes trapped inside if the sarcolemma reseals [14,15]. Dye-injected animals were perfuse-fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS under general anesthesia. Isolated TAs were cryoprotected with 20% sucrose in PBS, frozen slowly at -30°C and cryosectioned to obtain 16 μm cross sections. Dye was visualized under confocal fluorescent optics (Zeiss LSM410, 25X objective, Pinhole size = 13; Carl Zeiss, Poughkeepsie, NY). Myofibers retaining FDx, 7 and 14 d after injury, were scored as having been damaged initially but surviving injury with resealed sarcolemmae.

Myogenesis

We assessed myogenesis by counting the number of centrally nucleated fibers (CNFs) [16,17] and the number of myofibers expressing the developmental isoforms of the heavy chain of myosin (dMHC) [18]. We counted CNFs on 8 μm frozen cross sections of unfixed, snap frozen TA muscles stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and counted myofibers expressing dMHC on 16 μm frozen cross sections from the same muscles (VP-M664, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Sections labeled for dMHC were colabeled with antibodies to dystrophin (NCL-Dys2, Novocastra Laboratories, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK). As both antibodies are monoclonals, we labeled them directly with alexa 488 and 594 dyes respectively (Zenon Tricolor, Z-25070, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Fluorescence images were obtained by laser scanning microscopy under confocal fluorescent optics (see above, for settings)

Necrosis

We assessed necrosis as described [19], in H & E stained sections, and sections labeled for dystrophin and mounted with Vectashield containing DAPI (H-1200, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) to label nuclei.

Fiber size heterogeneity

To assess heterogeneity in fiber size, we measured the minimal Feret’s diameters of >500 muscle fibers for each mouse strain at each time point and analyzed them as described [20].

Statistical Methods

Statistical significance was determined by two factor analyses of variance and Tukey’s post-hoc tests using SAS® (Cary, NC), with alpha set at 0.05. Fig. 1A summarizes data from 8 animals per strain at each time point. Figs. 1B-D and the graphs in Fig. 4 summarize data from > 500 fibers per muscle, from 3 animals per strain, at each time point. Figs. 2A-C and 4 are representative images.

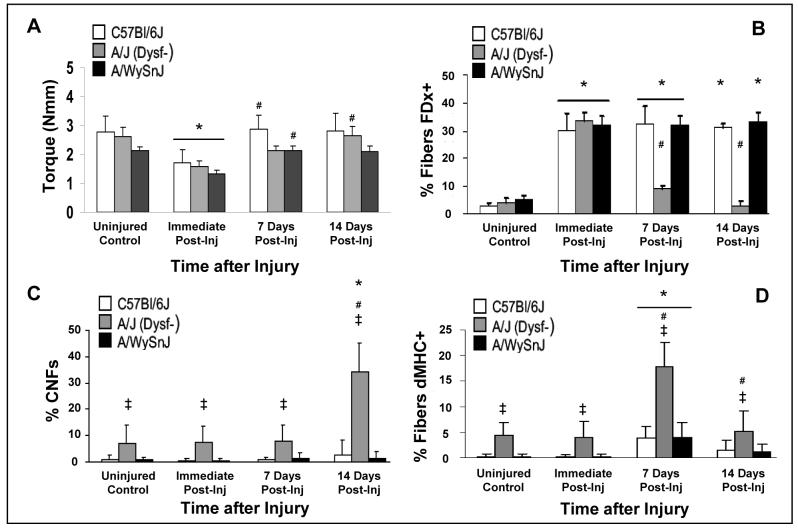

Figure 1. Recovery of contractile function, membrane repair, and myogenesis after large-strain injury.

A. Contractile torque decreased to ∼40% of pre-injury levels in all 3 strains of mice within 10 min of injury. Both control strains recovered to pre-injury levels within 7 d after injury, but the dysferlin-null A/J strain required 14 d to recover completely. B. Membrane disruption and subsequent repair and survival were assessed by uptake and retention of fluorescein dextran (FDx+) in the myoplasm of muscle fibers. There was no difference between the strains in the percentage of fibers that labeled with FDx before and immediately after injury. At 7 and 14 d after injury, control muscle fibers retained FDx, whereas dysferlin-null muscle fibers did not. C. Centrally nucleated fibers (CNFs) increased in dysferlin-null muscle 14 d after injury, but did not increase significantly from baseline in muscles from both control strains. D. Expression of developmental isoforms of the heavy chain of myosin (dMHC+) indicated greater myogenic activity in dysferlin-null muscle compared to control muscle 7 d after injury.

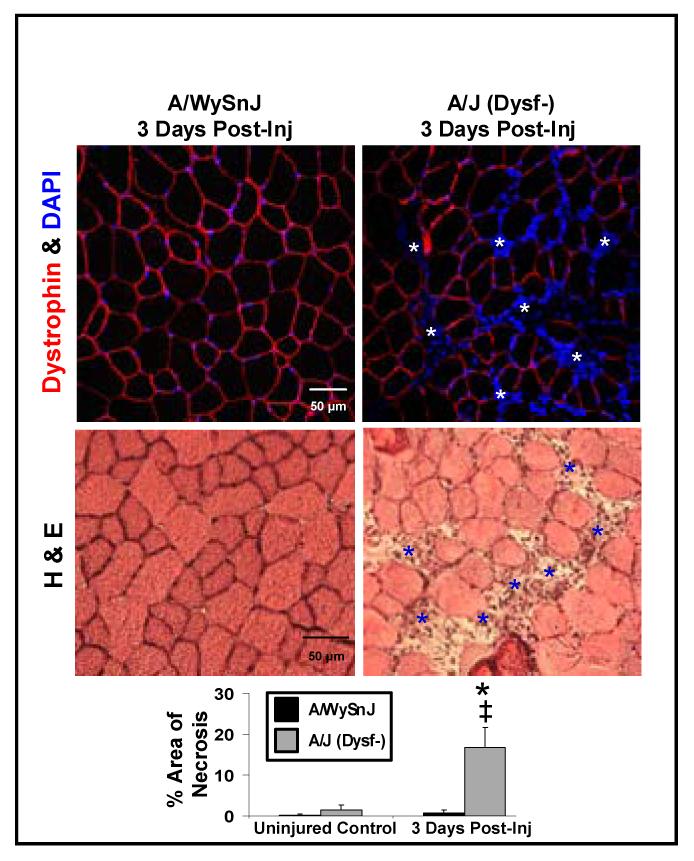

Figure 4. Necrosis after large-strain injury.

Significant necrosis was seen only in dysferlin-null muscle at 3d after LSI. (white asterisks above; blue asterisks below)

Symbol key for statistical comparisons. * - Significant difference compared to strain-matched uninjured control. ‡ - Significant difference compared to other strains at same time point. # - Significant difference from previous time point.

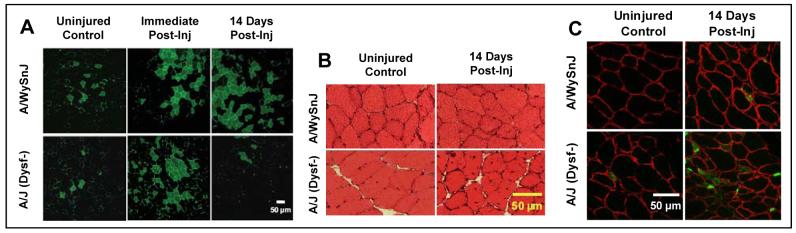

Figure 2. Membrane repair and myogenesis after large-strain injury.

A. Labeling of myoplasm by fluorescein dextran (FDx, green) before injury and immediately after injury, and its retention or lack of retention 14 d after injury. Two weeks after injury, fibers that were labeled initially by FDx were preserved in control but not in dysferlin-null muscle. B. Increase in CNFs 14 d after injury in dysferlin-null but not control muscles. C. Developmental isoforms of the heavy chain myosin (dMHC, green) were present in many more fibers of dysferlin-null than control muscle at 7 d post-injury. Antibodies to dystrophin label the sarcolemma (red).

Results

Functional Data

The maximal tetanic torques generated by the DFs of uninjured C57Bl/6J, A/J and A/WySnJ mice were 2.8 ± 0.6, 2.6 ± 0.3, and 2.1 ± 0.1 Nmm, respectively, but the ratios of torque to the weight of the TA muscle were 51 ± 8 Nmm/g, 61 ± 4 Nmm/g (p < 0.0001), and 51 ± 5 Nmm/g, respectively.

The loss of contractile torque immediately after LSI and the recovery of torque over a 14 d period are shown in Fig. 1A. Immediately after LSI, torque decreased to 62 ± 8%, 61 ± 5% and 62 ± 6% of respective pre-injury levels in C57Bl/6J, A/J and A/WySnJ mice. The torque lost after LSI recovered to pre-injury levels in both C57Bl/6J and A/WySnJ mice within 1 wk, but A/J mice required 2 wk to recover to pre-injury levels. Thus, dysferlin-null muscles are equally susceptible to initial injury from LSI as controls, but they require more time to recover.

In vivo membrane repair

Data on FDx entry and retention are presented in Fig. 1B, with representative images in Fig 2A. TA muscles of all three strains showed no significant difference in the number of fibers with cytoplasmic FDx before or immediately after injury. However, with time after injury the number of fibers with FDx decreased significantly in dysferlin-null muscles but not controls.

Myogenesis

We examined the possibility that myogenesis compensates for defective membrane repair in dysferlin-null muscles by counting CNFs ( Fig. 1C; 2B) and myofibers expressing dMHC (Fig 1D; 2C).

Uninjured TA muscles from the control strains had <1% CNFs, whereas uninjured A/J muscles had 7.1 ± 6% CNFs (p < 0.0001). Following LSI, we found no significant increase in CNFs in the TA muscles of either control strain, at any of the time points assayed. By contrast, CNFs in A/J muscles increased ∼5-fold 14 d after LSI (34 ± 10%, p < 0.0001 compared to uninjured).

Myofibers expressing dMHC did not exceed 5% in the TA muscles of either C57Bl/6J or A/WySnJ mice at any time post-injury. In TA muscles from A/J mice, however, myofibers expressing dMHC increased ∼4-fold, from 4 ± 2% before injury to 18 ± 5% of myofibers at 7 d after injury (p < 0.0001). The expression of dMHC in uninjured TA muscles from A/J mice was also significantly greater than expression in uninjured TA muscles from either control strain (p < 0.0001).

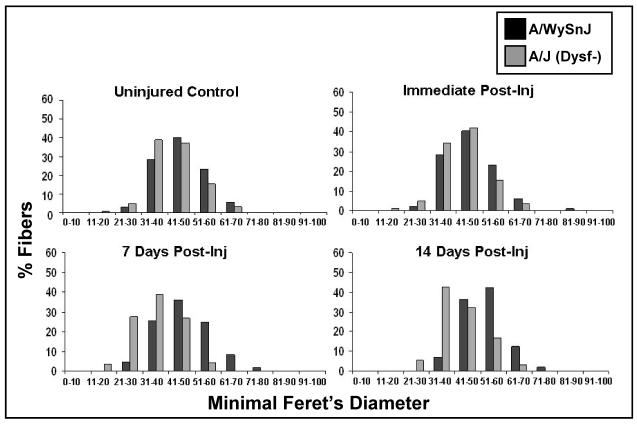

Our CNF and dMHC data are supported by measurements of the minimal Feret’s diameters of fibers from control and dysferlin-null mice before and after injury (Fig. 3). Compared to A/WySnJ muscles, uninjured muscles from A/J mice showed more fiber size heterogeneity with a shift from larger to smaller fibers, consistent with low levels of degeneration and regeneration even in uninjured muscle. By 7 d after LSI, the number of small fibers increased in A/J muscles, compared to uninjured A/J. This was accompanied by a concomitant decrease in the percentage of larger fibers. Such a shift in fiber size towards the smaller ranges after LSI was not seen in A/WySnJ muscles.

Figure 3. Fiber size heterogeneity before and after large-strain injury.

The minimal Feret’s diameters of muscle fibers in control and dysferlin-null muscle before injury and at different time points thereafter. Fibers with smaller diameters were present at 7 and 14 d after injury in dysferlin-null but not control muscle.

Necrosis

The slower rate of recovery of contractile function, lack of FDx retention, and increased myogenesis after injury suggest that dysferlin-null muscle fibers do not survive LSI and are replaced by new muscle fibers within 2 wk. We therefore studied the extent of necrosis at different times after LSI. As we did not find appreciable differences in the extent of necrosis between A/J and A/WySnJ muscles before injury, immediately after injury and at 7 and 14 d later, we focused our attention on muscles at 3 d post-injury. We chose this time based on earlier work showing a peak in macrophage infiltration and necrosis 3 d after muscle injury, generated by other models [8]. We found extensive necrosis and inflammatory cell infiltration only in dysferlin-null muscles (Fig 4), suggesting that dysferlin-null fibers injured by LSI undergo necrosis, thus giving rise to the need for myogenic replacement.

Discussion

Our experiments address the role of dysferlin in the physiology of skeletal muscle, and specifically in the response of skeletal muscles to injuries induced by large-strain lengthening contractions. Our data demonstrate that torque normalized to muscle weight is higher in dysferlin-null muscles, a result that has not been previously reported. In agreement with an earlier study of dysferlin-null mice exercised by running downhill (2), we found that they are no more susceptible to initial injury from LSI than controls. They do, however, recover contractile function after LSI more slowly than controls, and they recover by a mechanism that, unlike two strains of control mice, involves the replacement of injured myofibers by myogenesis.

Muscles in control mice recover from LSI by resealing of damaged sarcolemmal membranes without showing significant levels of myogenesis. By contrast, injured myofibers in dysferlin-null mice do not survive after several days following injury, as indicated by extensive necrosis 3 d after injury as well as by the disappearance of FDx-labeled myofibers. Instead, dysferlin-null muscles recover by generating new muscle fibers, as indicated by the presence of CNFs, myofibers expressing dMHC, and fibers with small diameters. Myogenic recovery of muscles after injuries caused by lengthening contractions requires a longer period of time than recovery mediated by the repair of damaged sarcolemma and the replacement of proteins lost in injured myofibers [7]. We propose that the delayed recovery of dysferlin-null muscles from LSI is due to the additional time required for myogenesis to replace damaged myofibers that are unable to survive sarcolemmal damage caused by the injury. As dysferlin-null muscles recover completely from LSI, primarily by generating new myofibers, our results suggest that myogenic mechanisms can be activated to restore muscle function after injuries from large-strain lengthening contractions when other, perhaps more local, repair mechanisms are insufficient or impaired. Although it remains to be determined if the presence of dysferlin modulates myogenic mechanisms in healthy muscle, our results clearly indicate that the absence of dysferlin affects both the time course and the mechanism of recovery from physiological injury in vivo.

TA muscles from both control strains of mice retain FDx two weeks after LSI, suggesting that control myofibers reseal their sarcolemmal membranes, trapping FDx in their myoplasm, and that they survive for 7-14 d after injury, when functional recovery from LSI is complete. In contrast, myofibers from A/J mice that sustain sarcolemmal damage and take up the dye at the time of injury are lost within a week, suggesting that long-term survival is compromised in dysferlin-null myofibers. The delayed recovery of A/J muscles after injury may be caused by the failure of their sarcolemmal membranes to repair themselves, due to the absence of dysferlin [2]. Our results show that at least some fibers undergo necrotic cell death and are replaced by myogenesis. We cannot rule out the possibility that other fibers are repaired utilizing alternative pathways, including those mediated by annexins, other ferlin family members (e.g., myoferlin), or related proteins, such as synaptotagmins, which may allow them to survive, but with delayed recovery. The unusual involvement of such proteins may also trigger an exaggerated inflammatory response [21] that affects survival and recovery. We are currently testing these possibilities.

Conclusion

Recovery of control skeletal muscle from contraction-induced injury in vivo is associated with membrane repair and long-term survival of the injured myofibers without myogenesis. In contrast, the recovery of dysferlin-null muscle occurs via myogenesis, without significant long-term survival of injured fibers.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: The Jain Foundation (to RJB); National Institutes of Health (K01AR053235 to RML); Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA 4278 to RML; MDA 3771 to RJB).

List of Abbreviations

- CNFs

Centrally nucleated fibers

- DFs

Dorsiflexors

- dMHC

Developmental myosin heavy chain

- FDx

Fluorescein dextran

- H & E

Hematoxylin and Eosin

- LSI

Large strain injury

- TA

Tibialis anterior

References

- 1.Anderson LV, Davison K, Moss JA, et al. Dysferlin is a plasma membrane protein and is expressed early in human development. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8(5):855–861. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.5.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bansal D, Miyake K, Vogel SS, et al. Defective membrane repair in dysferlin-deficient muscular dystrophy. Nature. 2003;423(6936):168–172. doi: 10.1038/nature01573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bashir R, Britton S, Strachan T, et al. A gene related to Caenorhabditis elegans spermatogenesis factor fer-1 is mutated in limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 2B. Nat Genet. 1998;20(1):37–42. doi: 10.1038/1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu J, Aoki M, Illa I, et al. Dysferlin, a novel skeletal muscle gene, is mutated in Miyoshi myopathy and limb girdle muscular dystrophy. Nat Genet. 1998;20(1):31–36. doi: 10.1038/1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ho M, Post CM, Donahue LR, et al. Disruption of muscle membrane and phenotype divergence in two novel mouse models of dysferlin deficiency. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13(18):1999–2010. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vafiadaki E, Reis A, Keers S, et al. Cloning of the mouse dysferlin gene and genomic characterization of the SJL-Dysf mutation. Neuroreport. 2001;12(3):625–629. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200103050-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lovering RM, Roche JA, Bloch RJ, De Deyne PG. Recovery of function in skeletal muscle following 2 different contraction-induced injuries. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(5):617–625. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takekura H, Fujinami N, Nishizawa T, Ogasawara H, Kasuga N. Eccentric exercise-induced morphological changes in the membrane systems involved in excitation-contraction coupling in rat skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2001;533(Pt 2):571–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0571a.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ingalls CP, Warren GL, Zhang JZ, Hamilton SL, Armstrong RB. Dihydropyridine and ryanodine receptor binding after eccentric contractions in mouse skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96(5):1619–1625. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00084.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barton-Davis ER, Cordier L, Shoturma DI, Leland SE, Sweeney HL. Aminoglycoside antibiotics restore dystrophin function to skeletal muscles of mdx mice. J Clin Invest. 1999;104(4):375–381. doi: 10.1172/JCI7866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warren GL, Hulderman T, Jensen N, et al. Physiological role of tumor necrosis factor alpha in traumatic muscle injury. Faseb J. 2002;16(12):1630–1632. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0187fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lovering RM, De Deyne PG. Contractile function, sarcolemma integrity, and the loss of dystrophin after skeletal muscle eccentric contraction-induced injury. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286(2):C230–238. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00199.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stone MR, O’Neill A, Lovering RM, et al. Absence of keratin 19 in mice causes skeletal myopathy with mitochondrial and sarcolemmal reorganization. J Cell Sci. 2007;120(Pt 22):3999–4008. doi: 10.1242/jcs.009241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McNeil PL, Steinhardt RA. Plasma membrane disruption: repair, prevention, adaptation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003;19:697–731. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111301.140101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyake K, McNeil PL. Mechanical injury and repair of cells. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(8 Suppl):S496–501. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000081432.72812.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bigard AX, Merino D, Lienhard F, Serrurier B, Guezennec CY. Quantitative assessment of degenerative changes in soleus muscle after hindlimb suspension and recovery. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1997;75(5):380–387. doi: 10.1007/s004210050176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tidball JG, Wehling-Henricks M. Macrophages promote muscle membrane repair and muscle fibre growth and regeneration during modified muscle loading in mice in vivo. J Physiol. 2007;578(Pt 1):327–336. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.118265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pierre BA, Tidball JG. Differential response of macrophage subpopulations to soleus muscle reloading after rat hindlimb suspension. J Appl Physiol. 1994;77(1):290–297. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.1.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grounds MD, Torrisi J. Anti-TNFalpha (Remicade) therapy protects dystrophic skeletal muscle from necrosis. Faseb J. 2004;18(6):676–682. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1024com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Briguet A, Courdier-Fruh I, Foster M, Meier T, Magyar JP. Histological parameters for the quantitative assessment of muscular dystrophy in the mdx-mouse. Neuromuscul Disord. 2004;14(10):675–682. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagaraju K, Rawat R, Veszelovszky E, et al. Dysferlin deficiency enhances monocyte phagocytosis: a model for the inflammatory onset of limb-girdle muscular dystrophy 2B. Am J Pathol. 2008;172(3):774–785. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]