Abstract

Gradual occlusion (O) of the swine left circumflex coronary artery (LCX) with an ameroid occluder results in complete O within 3 weeks, collateral vessel development, and compensatory hypertrophy. The purpose of this investigation was to determine the independent and combined effects of O and exercise training (E) on gene expression in the swine heart. Adult Yucatan miniature swine were assigned to one of the following groups (n = 6–9/group): sedentary control (S), exercise-trained (E), sedentary swine subjected to LCX occlusion (SO), and exercise-trained swine with LCX occlusion (EO). Exercise consisted of progressive treadmill running conducted 5 d/wk for 16 weeks. Gene expression was studied in myocardium isolated from the collateral-dependent left ventricle free wall (LV) and the collateral-independent septum (SEP) by RNA blotting. E and O each stimulated cardiac hypertrophy independently (p < 0.001) with no interaction. O but not E increased atrial natriuretic factor expression in the LV, but not in the SEP. E decreased the expression of β-myosin heavy chain in the LV, but not in the SEP. E retarded the expression of collagen III mRNA in SEP; but not in the LV. Exercise training and coronary artery occlusion each stimulate cardiac hypertrophy independently and induce different patterns of gene expression.

Keywords: exercise, treadmill training, cardiac hypertrophy, coronary artery occlusion

Introduction

Gradual occlusion of the swine left circumflex coronary artery (LCX) with an ameroid occluder results in complete occlusion of the LCX within 3 weeks, leading to collateral vessel development in the region served by the LCX and compensatory hypertrophy of the left ventricle (LV) (1–3). The function of the collateral-dependent region is relatively normal at baseline, but when the demand on the heart is increased by treadmill running, wall thickening is abnormal. The abnormal wall motion caused by LCX occlusion and unmasked by exercise is attenuated by moderate-to-high-intensity exercise training (3). While the regional blood flow, collateral development, and functional consequences of LCX occlusion have been studied in detail, the cardiac hypertrophy in this region has not been characterized in terms of gene expression or collagen deposition.

Depending on the nature of the stimulus (i.e. exercise vs. disease; periodic vs. constant), cardiac hypertrophy manifests phenotypic correlates that are associated with enhanced, unchanged, or diminished myocardial function. Phenotypic changes that are neutral or beneficial are considered physiological, while changes that presage heart failure or directly impair function are termed pathological. The factors that distinguish physiological from pathological cardiac hypertrophy are only partially understood, and information gleaned from research on rodent models has provided the most mechanistic insights (4–6). Given some of the physiological differences between rodents and larger mammals, however, the generalizability of commonly used phenotypic rodent markers of cardiac hypertrophy and their utility in interpreting the phenotype and evaluating underlying mechanisms in larger mammals remains unclear. In this regard, the swine model has proven useful because its cardiac biochemistry and collateral coronary circulation are remarkably similar to that of the human (1–3). In particular, the slower contracting β-myosin heavy chain is the predominant isoform in the swine heart as it is in the human heart; this contrasts the rodent heart in which the faster contracting α-myosin heavy chain predominates (7). Correspondingly, the kinetics of contraction and relaxation in the swine heart and human heart are much slower than those in the rodent heart.

The miniature swine model of treadmill running produces physiological cardiac hypertrophy with little or no alteration in major biochemical parameters associated with calcium handling, contractile function, or metabolism (8). Indices of swine heart function and blood flow are either maintained, or augmented by exercise training (9, 10). Furthermore, exercise training improves blood flow and endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation to collateral-dependent areas in which major coronary arteries are compromised (3, 11). Although exercise training does not cause detectable shifts in cardiac biochemical parameters such as myosin ATPase activity, sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase activity, and enzyme activities of the glycolytic and oxidative pathways (8) that are typically observed in rodents, exercise training does induce significant cardiac hypertrophy of 15–30% that enhances cardiac reserve, improves myocardial blood flow, and augments myocardial function (3, 8–11). Whether or not exercise training alters the expression of hypertrophy-associated genes that reflect the physiological phenotype in the porcine heart as it does in the rodent heart has not been reported.

Gradual occlusion of the left circumflex (LCX) coronary artery limits oxygen and nutrient delivery to the left ventricular free wall (LV) and stimulates angiogenesis (2, 12). The development of new collaterals in the affected region in response to gradual occlusion of the LCX is sufficient to prevent severe infarction and maintain blood flow at rest, but limits blood flow when the heart is challenged by acute exercise (2). While the consequences of gradual LCX occlusion for local myocardial function and endothelial cell function have been studied extensively (1–3, 11), the nature (i.e. physiologic vs. pathologic) and magnitude of the resultant cardiac hypertrophy have not been reported. Abrupt occlusion of a coronary artery in mammals leads to myocardial infarction and hypertrophy of the remaining viable tissue that is phenotypically pathological (13–15). It is not clear, however, whether gradual LCX occlusion stimulates changes in gene expression that are associated with the physiological or pathological phenotype.

Cardiac hypertrophy is typically associated with altered expression of a number of heart-specific genes. Pathological hypertrophy is characterized by reexpression of the so-called “fetal gene program”, while physiological hypertrophy is associated with gene expression changes that are both similar and distinct from those observed in pathological hypertrophy. Ventricular expression of the atrial natriuretic factor gene (ANF) is markedly increased in response to a wide range of pathological insults (16–18), while exercise training often, but not always, elicits a similar ANF response (19–21). Thus, the expression of ANF in the ventricles is a reliable marker of cardiac hypertrophy; the magnitude of the increase in ANF expression often correlates with the magnitude of cardiac hypertrophy (22). Changes in expression of the reciprocally-regulated myosin heavy chain genes are directionally different in physiological vs. pathological cardiac hypertrophy in rodents (14, 23–25) and humans (26–28). The α-isoform of cardiac myosin heavy chain is associated with a faster rate of ATP hydrolysis, faster cardiac muscle contraction, and physiological cardiac hypertrophy, while the β-isoform is associated with slower mechanical and enzymatic properties, greater energetic economy, and pathological cardiac hypertrophy (29–31). During physiological cardiac hypertrophy the extracellular matrix remodels in proportion to myocyte enlargement thereby maintaining a normal matrix-myocyte ratio. In contrast, pathological hypertrophy is associated with a disproportionate increase in the extracellular matrix, termed fibrosis. Because collagen Type III is a major component of the extracellular matrix in the heart, expression of the mRNA encoding it can be a marker of the potential for fibrosis (32, 33). Based on the considerations discussed above, it was predicted that exercise training of miniature swine would increase expression of ANF and either decrease or have a neutral effect on the expression of β-myosin heavy chain and collagen genes in the swine left ventricle and septum. In contrast, it was expected that gradual occlusion of the coronary artery in swine would increase the expression of the ANF, β-myosin heavy chain, and collagen genes in the affected (ischemic) portion of the left ventricle free wall.

A number of signal transduction pathways have been defined that link extracellular signals to the transcriptional and translational machinery that produces the hypertrophic accumulation of proteins and the phenotypic characteristics (34–36). The extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway, one of the earliest signal transduction pathways discovered and among the best understood, serves as a prototype for signaling cascades that influence transcription of specific genes and is also involved in growth of cardiac myocytes (35). Two distinct ERK proteins referred to as ERK1 and ERK2 represent 44- and 42-kDa isoforms of ERK, respectively, with identical phosphorylation/activation sites and indistinguishable functional properties (35). Chronic heart-specific activation of MEK1, the kinase immediately upstream of ERK1/2, leads to activation of ERK1/2 and is sufficient to induce cardiac hypertrophy (37). ERK1/2 is transiently activated in the rat heart by an acute bout of exercise, but the activation of ERK is not sustained in the exercise trained heart (38). In contrast, activation of ERK1/2 is sustained for at least 2 months in response to long-term constant pressure overload in guinea pigs (39). Based on these reports, it was predicted that gradual coronary artery occlusion, but not exercise training would lead to a sustained activation of ERK1/2 in the affected area of the left ventricle of swine.

The purpose of this study was to compare the independent and combined effects of gradual occlusion of the LCX coronary artery and exercise training on the phenotype of cardiac hypertrophy in porcine myocardium. It was hypothesized that gradual occlusion of the LCX coronary artery would induce the fetal gene program as indicated by increased expression of ANF and β-MHC mRNAs, and also increase the expression of the collagen type III extracellular matrix gene in the affected (ischemic) region of the LV. It was predicted that exercise training of the non-occluded group would decrease expression of β-MHC, augment expression of ANF, and have no effect on the extracellular matrix gene encoding collagen type III. Finally it was hypothesized that if LCX occlusion increased expression of β-MHC and collagen Type III in the affected (ischemic) region of the LV, then exercise training would attenuate the occlusion-induced changes.

The data presented here show that gradual LCX occlusion and exercise training each stimulated cardiac hypertrophy independently, and when the two stimuli were combined, the hypertrophic growth was twice that of either individual effect. Gradual LCX occlusion increased expression of ANF, but did not alter that of β-MHC or collagen Type III in the affected portion of the left ventricular free wall. Exercise training decreased experession of β-MHC in the left ventricular free wall and decreased collagen Type III expression in the septum.

Materials and methods

Animals

Adult Yucatan miniature swine of either sex were randomly assigned to one of the following groups (n = 6–9/group): sedentary control (S), exercise-trained (E), sedentary swine subjected to LCX occlusion (SO), and exercise-trained swine with LCX occlusion (EO). The LCX was encircled with an ameroid occluder that provided gradual obstruction of the artery. The exercise training consisted of a progressive treadmill running program conducted 5 d/wk for 16 weeks. Gene expression was studied in the LV and the interventricular septum by RNA blotting.

Animal Instrumentation for Coronary Artery Occlusion

Animals assigned to this group were sedated with ketamine (20 mg/kg im), midazolam (0.5 mg/kg im), and glycopyrrolate (0.004 mg/kg im). Pigs were intubated and maintained on isofluorane anesthesia. The animals were prepared for aseptic surgery, a left lateral thoracotomy was performed, and the pericardium was incised. The LCX was bluntly dissected free of surrounding connective tissue, and the artery was encircled with an ameroid occluder (2.5 to 3.4 mm ID) to provide gradual obstruction of the artery. The ameroid occluder is an internally concave semi-circular metal ring filled with ameroid material that expands as it absorbs moisture. When surgically placed it does not impose any constriction on the artery, but gradually expands until it completely occludes the artery. The occlusion is typically complete by 3 weeks post-surgery, but it typically results in little (usually less that 5%) infarction of the area served by the LCX because of the gradual nature of the ameroid expansion (1–3). Buprenorphine (0.01 mg/kg iv) was administered intraoperatively for pain control. A standard thoracotomy closure was performed in layers. In the immediate postoperative period, intrapleural bupivicaine was instilled for pain relief. Penicillin (30,000 U im) was administered perioperatively, and trimethoprim sulfa (480 mg/50 lb per 0 s) was given for 5 days after surgery. Surgical procedures described were in compliance with the Position of the American Heart Association on Research Animal Use and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Missouri.

Exercise Training

Eight weeks after surgery, pigs were divided into sedentary and exercise-trained groups. Exercise-trained pigs were acclimated to a low-speed motorized treadmill (Quinton) to initiate an exercise training protocol of progressive intensity adapted from a treadmill training program formulated by Tipton et al. (40). During the first week of training, pigs ran on the treadmill at 3 miles/h (mph) and 0% grade for 20–30 min followed by a 15-min sprint at 5 mph. Length of training and treadmill speed were increased over time in accordance with the tolerance of individual pigs. From the fourth week of training, the exercise protocol consisted of an 85-min workout with a 5-min warm-up at 2.5 mph, a 15-min sprint at 5–8 mph, a 60-min endurance run at 4–5 mph, and a 5-min cool-down run at 2 mph. Sedentary pigs remained in pens during the same time period.

Exercise-trained animals were killed 14–16 hours after the last bout of exercise. Sedentary animals were killed at a similar time of day. Samples from the LV free wall and septum were fast frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C. The LV free wall samples were taken from an area served by the LCX. The efficacy of training was assessed by comparing heart-to-body weight (HW/BW) ratios, and skeletal muscle oxidative capacity of sedentary and exercise-trained pigs. Skeletal muscle oxidative capacity was assessed by measuring citrate synthase activity using a spectrophotometer. Coronary and pulmonary arteries of the animals were used in other studies (41, 42).

Northern blotting

Northern blotting was performed as described previously with modifications (32). RNA was isolated from left and right ventricles by the method of Chomczynski and Sacchi (43). Ten or twenty micrograms of total RNA was size fractionated by electrophoresis through 1% agarose gels, transferred electrophoretically at 5 V·cm−1 to a nylon (Nytran-SPC) membrane and hybridized with 32P-radiolabelled probes overnight at 68°C for cDNA probes and 42°C for oligonucleotide probes using PerfectHyb Plus (Sigma). Hybridization intensity was quantified with a Personal Molecular Imager FX (Bio-Rad). Signals visualized on a computer screen were identified by position relative to 18S or 28S rRNA migration, delineated by rectangles and quantified after background subtraction. Each blot was subsequently stripped and reprobed. The signal from each sample was normalized to the signal obtained with a probe for either the 18S rRNA, the 28S rRNA, or glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH).

Probes

Complementary DNA probes were synthesized from a template by the random prime method as described previously (32). The probe for human pro-α1(III) collagen was a cDNA kindly provided by M-L. Chu (44). The probes for atrial natriuretic factor (ANF), β-myosin heavy chain (β-MHC), 28S ribosomal RNA, the 18S ribosomal RNA, and GAPDH, were end-labeled synthetic oligonucleotides with the sequences shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide probes used for Northern blotting.

| Target Gene | Sequence | Length | Region | Accession # or Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANF | 5′-GGGGGCTGAGAGGGGCCCCCACTTCCTCATTCTGCTCGC-3′ | 39-mer | Coding | X54669 |

| β-MHC | 5′-GCTCCAGGACTGGGAGCTTTGTTGCGCCCTCAGGATGGGG-3′ | 40-mer | 3′ UTR | X91846, AB053226 (reference 64) |

| 28S rRNA | 5′-TGGCAACAACACATCATCAGTAGGGT 3′ | 26-mer | Ribosomal | F14557 |

| 18S rRNA | 5′-ACGGTATCTGATCGTCTTCGAACC-3′ | 24-mer | Ribosomal | AF102857 |

| GAPDH | 5′-CCTCTCTCCTCCTCGCGTGCTCTTGCTGGGGTTGGTGGTCC-3′ | 41-mer | 3′ UTR | AF017079 |

ANF, atrial natriuretic factor; MHC, myosin heavy chain; rRNA, ribosomal RNA; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; UTR, untranslated region.

Sample preparation for immunoblotting

Tissue samples taken from both the left ventricle free wall and septum were homogenized in buffer (62.5 mmol/L Tris, pH 6.8, 1 mmol/L PMSF, 10 μg/μl Aprotinin, 10 μg/μl Leupeptin, 100 μmol/L sodium orthovanadate, 1% Triton X-100). Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA reagent and a Spectrogenesis spectrophotometer. Samples were adjusted to a final concentration of 2 mg/ml in sample buffer (125 mmol/L Tris, pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 20% glycerol, 10% 2-mercaptoethanol, and 0.001% bromphenol blue). A Western blot titration was performed in order to determine the optimal amount of protein to be loaded into each well. 20 μg of protein per lane provided optimal results for the study of ERK.

Immunoprecipitation of ERK2

After homogenization, a 400 μg portion of each sample was immunoprecipitated in RIPA buffer (10 mM Tris pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl, 1% deoxycholic acid, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS) with 10 μl of ERK2 rabbit polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz). 160 μl of Protein A was added to each sample followed by centrifugation and washing of the pellet with lysis buffer (20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 2 mM EDTA, 50 mM β–glycerol-phosphate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 1 mM PMSF, aprotinin, leupetin). 80 μl of 2X-sample buffer was added to each pellet and then boiled. 10 μl (20 μg) of each sample were loaded into each well for gel electrophoresis.

Immunoblotting of ERK2

All samples underwent SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis using 10% acrylamide gels. Proteins were then transferred to a PVDF membrane. The antibodies used to study the activity of ERK included the ERK2 rabbit polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz) followed by the peroxidase-labeled anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Amersham); and the phospho-p44/42 MAPK monoclonal antibody (New England Bio Labs) followed by the peroxidase labeled anti-mouse secondary antibody (Amersham). Antibody binding was detected using Enhanced Chemiluminescence (ECL). Signals were quantified with a laser densitometer.

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± SE. Comparisons between groups were made with two-factor ANOVA (SYSTAT). Outliers were excluded according to the studentized residual method. One outlier in the sedentary group was excluded from the HW/BW data. One outlier in the exercise-trained occlusion group was excluded from the LV ANF data. One outlier in the exercise-trained occlusion group was excluded from the LV β-MHC data. Alpha was set at (p < 0.05).

Results

To determine the effects of exercise training and gradual LCX occlusion on the magnitude of cardiac growth, HW/BW ratios were examined (Table 2). Exercise training (13%) and gradual LCX occlusion (13%) each increased the HW/BW ratio independently. There was no significant interaction between the effects of exercise training and LCX occlusion, indicating that the effects of exercise and LCX occlusion were neither synergistic nor interfering, but simply additive.

Table 2.

Heart weights and body weights of the four groups of swine.

| Group |

Probabilities (2-factor ANOVA) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Sedentary Non-Occluded (S) |

Exercise-Trained Non-Occluded (E) |

Sedentary Occluded (SO) |

Exercise-Trained Occluded (EO) |

Occlusion | Exercise | O*E Interaction |

| Sex (n) | M = 2, F = 6 | M = 7, F = 0 | M = 1, F = 6 | M = 7, F = 1 | |||

| Body Weight (kg) | 31.0 ± 1.7 | 32.6 ± 0.9 | 34.1 ± 1.2 | 34.6 ± 1.2 | NS | NS | NS |

| Heart Weight (g) | 150.5 ± 4.7 | 172.1 ± 7.9 | 185.5 ± 8.9 | 210.1 ± 5.2 | P < 0.01 | P < 0.001 | NS |

| HW/BW (g/kg) | 4.7 ± 0.4 | 5.3 ± 0.2 | 5.3 ± 0.1 | 6.1 ± 0.1 | P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | NS |

Values are mean ± SE. HW, heart weight; BW, body weight; M, male; F, female.

The efficacy of exercise training was also tested by measuring citrate synthase activity (Table 3). Citrate synthase activity was significantly elevated in the deltoid, the lateral head of the triceps, and the long head of the triceps by exercise training (p < 0.05). There were no main effects of LCX occlusion, nor were there any exercise-occlusion interactive effects on citrate synthase activity in any of the three skeletal muscles.

Table 3.

Citrate synthase activity in selected skeletal muscles of swine.

| Group |

Probabilities (2-factor ANOVA) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citrate synthase activity (μmol/min/g) |

Sedentary Non-Occluded (S) |

Exercise-Trained Non-Occluded (E) |

Sedentary Occluded (SO) |

Exercise-Trained Occluded (EO) |

Occlusion | Exercise | O*E Interaction |

| n | 6 | 7 | 7 | 8 | |||

| Deltoid | 15.3 ± 1.3 | 21.8 ± 1.9 | 13.5 ± 0.7 | 22.0 ± 1.8 | NS | P < 0.05 | NS |

| Triceps, lateral head | 11.2 ± 1.0 | 18.2 ± 1.6 | 11.0 ± 1.0 | 15.9 ± 1.6 | NS | P < 0.05 | NS |

| Triceps, long head | 10.2 ± 0.7 | 15.2 ± 1.7 | 10.4 ± 1.6 | 11.0 ± 0.7 | NS | P < 0.05 | NS |

Values are mean ± SE. See reference 65 for methodological details.

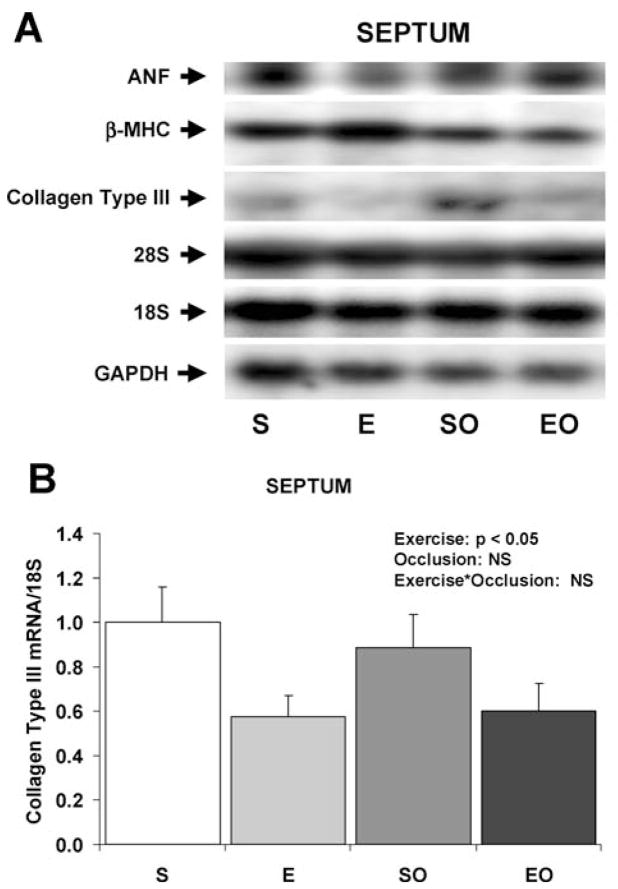

To determine the phenotypic pattern of altered gene expression induced by exercise training and gradual LCX occlusion, the levels of mRNA in the LV free wall and septum were measured by Northern blotting. The relative levels of ANF mRNA were increased by 15% and 47% in the LV of swine that underwent gradual LCX occlusion without and with exercise training, respectively (Figure 1). There was a significant main effect of gradual LCX occlusion on ANF expression in the LV (p < 0.05), but the main effect of exercise training was not significant. Although there was no significant interaction between exercise training and LCX occlusion (p = 0.15), the ANF mean value was numerically greatest in the EO group suggesting the tendency for a weak interaction. When ANF data from the LV were normalized to GAPDH instead of the 28S rRNA, the results were similar (data not shown). There were no main effects or interactive effects of exercise training and gradual LCX occlusion on ANF expression in the septum.

Fig. 1.

Expression of hypertrophy-associated genes in the swine LV in response to exercise training and/or LCX occlusion. A: Representative Northern blots of mRNA in the LV. B: Bar graph of mean data of ANF mRNA expression in the LV. C: Bar graph of β-MHC mRNA expression in the LV. Values are mean ± SE for n = 6–8 per group. Main effects and interactive effects of exercise training and gradual LCX occlusion are indicated (2-factor ANOVA). ANF, atrial natriuretic factor; β-MHC, β-myosin heavy chain; S, sedentary control non-occluded; E, exercise-trained non-occluded; SO, sedentary with gradual LCX occlusion; EO, exercise-trained with gradual LCX occlusion.

Exercise training decreased the expression of β-myosin heavy chain in the LV by 25% in non-occluded swine and by 56% in swine with gradual LCX occlusion (Figure 1). There were no significant effects of gradual LCX occlusion on the expression of β-myosin heavy chain in the LV. When β-myosin heavy chain data from the LV were normalized to GAPDH instead of the 28S rRNA, the results were similar (data not shown). There were no differences among any of the 4 groups in the expression of β-myosin heavy chain in the septum.

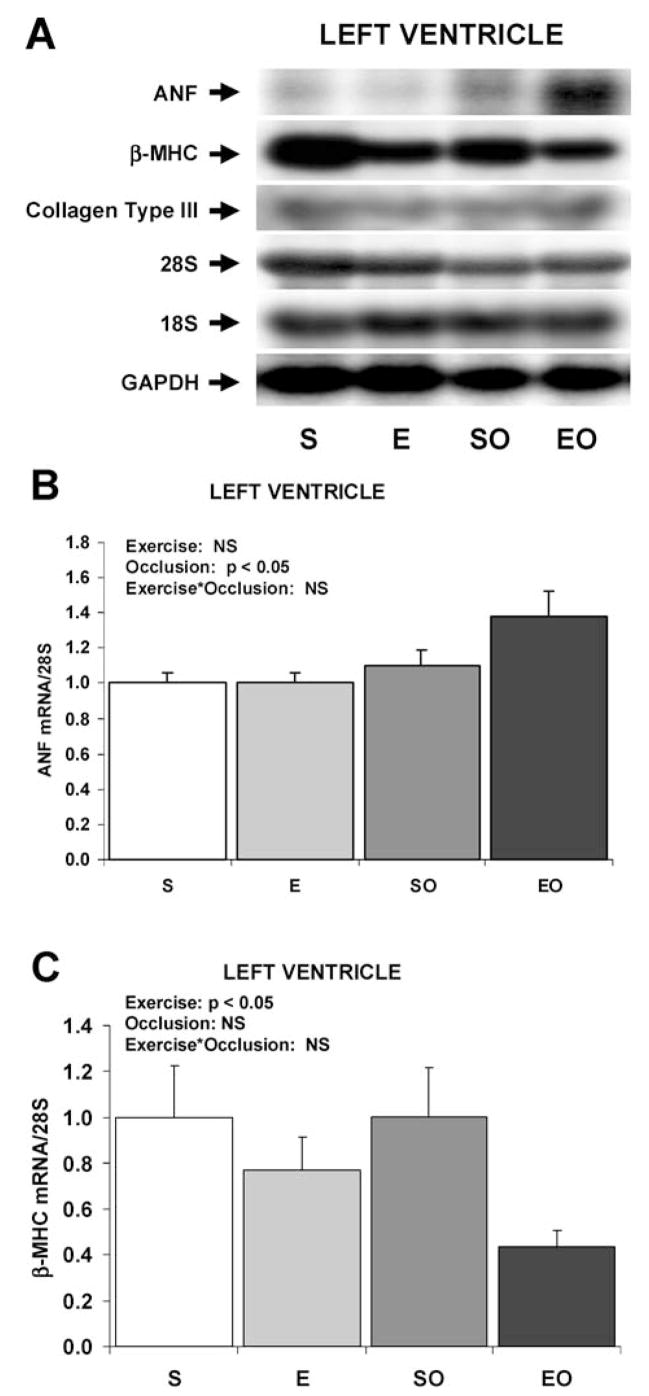

Expression of collagen III mRNA in the LV was not different among the four groups of swine, but there was a main effect of chronic exercise training to decrease the expression of collagen III mRNA in the septum by approximately 40% (Figure 2). When collagen III data from the LV were normalized to GAPDH instead of the 18S rRNA, the results were similar (data not shown). There were no significant main effects of gradual LCX occlusion on collagen type III expression in the septum, nor were there any interactive effects of occlusion and exercise.

Fig. 2.

Expression of hypertrophy-associated genes in the swine septum in response to exercise training and/or LCX occlusion. A: Representative Northern blots of mRNA in the septum. B: Bar graph of mean data of Collagen Type III mRNA expression in the LV. Values are mean ± SE for n = 6–8 per group. Main effects and interactive effects of exercise training and gradual LCX occlusion are indicated (2-factor ANOVA). ANF, atrial natriuretic factor; β-MHC, β-myosin heavy chain; S, sedentary control non-occluded; E, exercise-trained non-occluded; SO, sedentary with gradual LCX occlusion; EO, exercise-trained with gradual LCX occlusion.

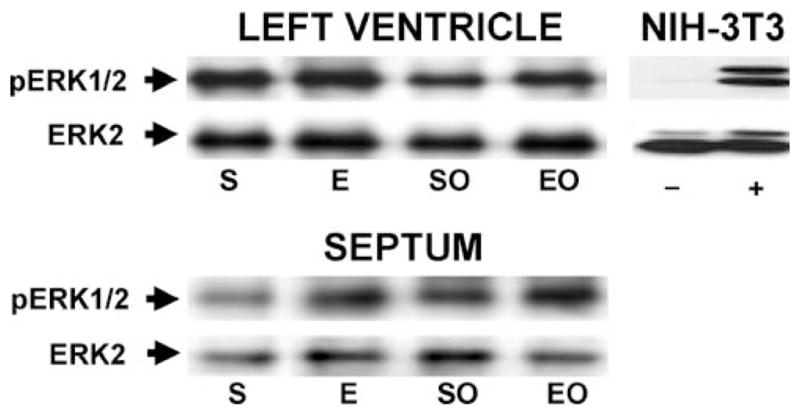

To determine the singular and combined effects of exercise training and LCX occlusion on molecular signaling in the left ventricle, the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 was studied. Tissue samples from the LV and septum were subjected to SDS-PAGE on a 10% gel. ERK1/2 abundance was determined by immunoblot analysis using an ERK2 antibody and a phospho-specific p42/p44 MAPK antibody was used to determine ERK1/2 activation. Then the signal from the phospho-specific pMAPK antibody was normalized to the signal for the polyclonal ERK2 antibody (Figure 3). The relative values for phosphorylation/activation of ERK1/2 expressed in arbitrary units were S, 1.7 ± 0.2 (mean ± SE); E, 1.6 ± 0.1; SO, 1.4 ± 0.1; EO, 1.5 ± 0.2 in the LV. In the septum, the values were: S, 4.1 ± 1.1; E, 3.1 ± 0.8; SO, 2.9±0.3; EO, 2.1±0.5. There were no statistically significant differences in either the abundance or the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in either the LV or the septum.

Fig. 3.

Phosphorylation state of ERK1/2 in the LV free wall and septum of swine in response to exercise training and/or LCX occlusion. Representative Western blot of protein samples immunoprecipitated with ERK2 from miniature swine LV free wall and septum. pERK1/2, phosphorylated ERK1/2 detected with an antibody specific for dually phosphorylated ERK1/2; ERK2, p42-ERK detected with an antibody that recognizes p42-ERK regardless of phosphorylation state. There were no significant main effects or interactive effects among the groups (2-factor ANOVA). Dishes of cultured NIH-3T3 fibroblasts were treated with vehicle (−) or fetal bovine serum (+) as negative and positive controls, respectively, for ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to compare the independent and combined effects of gradual occlusion of the LCX coronary artery and exercise training on the phenotype of cardiac hypertrophy in porcine myocardium. The major findings of this study are that 1) gradual LCX occlusion stimulates cardiac hypertrophy that is similar in magnitude to that induced independently by exercise training, 2) the combination of LCX occlusion and exercise training doubles the magnitude of LV hypertrophy, 3) gradual occlusion of the LCX coronary artery induces some features of the fetal gene program as indicated by increased expression of ANF, but not others; the levels of β-MHC, collagen type III were not altered by LCX occlusion, 4) exercise training decreases expression of β-MHC in the LV and decreases expression of collagen Type III in the septum, but does not significantly alter the expression of ANF in either region. The data demonstrate that exercise training and gradual LCX occlusion each stimulate cardiac hypertrophy independently, and that when combined, the effects of occlusion and exercise training are neither synergystic nor interfering, but simply additive.

ANF is a reliable and commonly used mRNA marker of ventricular cardiac hypertrophy. Moreover, its expression in the ventricles is increased in response to both physiological and pathological stimuli (16, 19, 20). Rapid pacing and pressure overload both increased ANF mRNA expression in the affected swine ventricle (17, 18). Thus it is not surprising that gradual occlusion of the LCX coronary artery increased the levels of ANF mRNA in the LV and that there was a weak tendency for the increase in ANF expression to be greatest when exercise training and gradual LCX occlusion were combined. It is noteworthy that the levels of ANF mRNA are elevated at the time of study, 24 weeks after placement of the Ameroid occluder and 16 weeks after the initiation of the exercise training. These findings demonstrate that elevated steady state levels of ANF mRNA are an adaptation to LCX occlusion that persists long after the stimulus is initiated. The data suggest that the hypertrophic response and the elevated expression of ANF are related to ischemia in the collateral-dependent area induced by the limited collateral development after LCX occlusion, ischemia that may be exacerbated by the daily bouts of exercise (2, 3).

The functional heterogeneity of myosin provides a mechanism by which the heart can mix isoforms to optimize the coordinated action of sarcomeres from different regions of the ventricular wall that may have different requirements for speed versus economy (45, 46). The functional consequences of myosin isoform switching are well understood in rodents and rabbits because the different protein isoforms are separable electrophoretically (47). In contrast, myosin heavy chain protein isoforms from higher mammals have not been successfully separated by electrophoretic methods. Therefore, our understanding of the role of myosin isoforms in higher mammals has been limited to inferences drawn from measurements of mRNA levels. Studies of mRNA levels indicate that both the α- and β-myosin heavy chain genes are expressed in human heart, that they are influenced by thyroid hormone, and that the β-myosin heavy chain isoform predominates (26–28, 48). Even though the expression of α-myosin heavy chain is thought to be relatively low in the human heart, decreases in the expression of α-myosin heavy chain mRNA are associated with aging and heart failure in humans (26–28). At the protein level, exercise training has either neutral effects on myosin isoform expression or tips the balance in favor of α-myosin heavy chain (24, 41). In some (but not all) cases, exercise training decreases the expression of β-myosin heavy chain mRNA in the rodent heart (50–52). Previous studies of exercise-trained swine have failed to detect any differences in myosin ATPase activity in LV homogenates, suggesting that there is no significant switching of myosin isoforms in the swine heart in response to exercise training (8). Thus it is surprising that in the present study, exercise training led to a decrease in the expression of β-myosin heavy chain mRNA. The functional significance of this finding is not clear, but it suggests that some of the same exercise training-induced mechanisms that are operative in rodent hearts may be at work in the hearts of higher mammals.

Exercise training attenuates the age-associated increase in crosslinking of collagen in the rodent heart, but increases the expression of collagen type III mRNA in the aged rodent heart (53–55). The effect of exercise training to reduce the steady state levels of collagen Type III mRNA in the septum suggests that collagen regulation may differ by age and species. Reduced activation of the collagen type III gene could be a positive effect of exercise training and could be a mechanism by which exercise stimulates cardiac hypertrophy without fibrosis, but these points are speculative at present. The lack of a similar exercise training effect on collagen gene expression in the LV of non-occluded swine is somewhat puzzling, because the exercise effects on the expression of other genes are most prominent in the LV.

Based on the differential response of ERK1/2 to chronic exercise training and LV pressure overload that was observed in rodents (38, 39), it had been predicted that activation of ERK1/2 would be greater in the affected area of the LV in swine with gradual LCX occlusion compared with that of sedentary and exercise-trained swine. Neither LCX occlusion nor chronic exercise increased the steady-state phosphorylation (activation) of ERK1/2 in the left ventricle of miniature swine. The lack of increased activation in the LCX occlusion groups (and the lack of unambiguous activation of any of the markers of pathological hypertrophy employed herein by LCX occlusion) may relate the relatively gradual and modest nature of the occlusion stimulus. Although the gradual LCX occlusion did produce significant cardiac hypertrophy (Table 2), and is typically associated with abnormal wall motion (3), it does not lead to overt heart failure as does the chronic pressure overload model in which ERK1/2 was observed to be chronically activated (39).

The present study has limitations. First, the number of samples studied was sufficient to provide excellent power for main effects, but somewhat less robust power for interactive effects. The power achieved allowed detection of significant interactive effects at an effect size of 1.1 standard deviations (power = 0.8; β = 0.2). Due to greater within-group variability than anticipated, this was less than the 0.5 effect size that was the original goal when sample sizes were planned. Examination of the data and the p values for interactive effects suggests that this had little or any effect on the interpretations. The only interaction that is hinted at by p value is the interactive effect on ANF expression (pointed out in the Results and Discussion sections above). Secondly, swine of both sexes were used and sex was not balanced evenly across groups. This may be an important consideration, because a number of reports detail important cardiac-specific sex differences in various animal species (56–58). The impact of this limitation on interpretations in the present study is likely to be minimal, however, for the following reasons. 1) Myosin isoform switching in the heart in response to physiological and pathological stimuli has been reported in animals and humans of both sexes (26–28, 48, 59). 2) LV ANF expression is increased several fold in response to hypertrophic stimuli in animals of either sex (13, 16–18, 21, 22, 32, 60, 61); the increase in ANF expression in response to a hypertrophic stimulus is typically greater in magnitude than the gender differences in ANF expression (62); differences among rat strains in ventricular ANF expression are greater than gender differences (57). 3) Increases in expression of extracellular matrix components are reported for animals of both sexes with no gender differences in the magnitude of response (62), but not in response to exercise in either sex (53–55, 63). 4) Examination of the present data with respect to sex differences did not reveal any within-group anomalies as a function of sex.

In summary, exercise training and gradual LCX occlusion each stimulated cardiac hypertrophy independently; the combined effects of occlusion and training on the magnitude of hypertrophy were additive. Gradual occlusion of the LCX coronary artery induced an increase in the expression of ANF in the affected area of the LV, but not in the levels of β-MHC or collagen type III mRNA. Exercise training decreased expression of β-MHC in the LV and decreased expression of collagen Type III in the septum, but did not significantly alter the expression of ANF. Whereas exercise training induced a pattern of gene expression that was consistent with physiological cardiac hypertrophy, gradual occlusion of the LCX coronary artery caused the expected changes in the expression of ANF in the affected LV, but not in the expression of β-MHC or collagen Type III.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the AHA Midwest Affiliate (M. O. Boluyt), by The University of Michigan Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program (A. M. Loyd), by NIH HL-52490 (M. H. Laughlin and J. L. Parker), and by NIH KO1 AG00875 (D. H. Korzick). The authors thank Pamela Thorne for excellent technical assistance with these studies and Claire Stuve for help in peparing the manuscript.

References

- 1.O’Konski MS, White FC, Longhurst J, Roth D, Bloor CM. Ameroid constriction of the proximal left circumflex coronary artery in swine. A model of limited coronary collateral circulation. Am J Cardiovasc Pathol. 1987;1:69–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roth DM, Maruoka Y, Rogers J, White FC, Longhurst JC, Bloor CM. Development of coronary collateral circulation in left circumflex Ameroid-occluded swine myocardium. Am J Physiol. 1987;253:H1279–1288. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.253.5.H1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roth DM, White FC, Nichols ML, Dobbs SL, Longhurst JC, Bloor CM. Effect of long-term exercise on regional myocardial function and coronary collateral development after gradual coronary artery occlusion in pigs. Circulation. 1990;82:1778–1789. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.5.1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frey N, Olson EN. Cardiac hypertrophy: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003;65:45–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dorn GW, Robbins J, Sugden PH. Phenotyping hypertrophy: eschew obfuscation. Circ Res. 2003;92:1171–1175. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000077012.11088.BC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wikman-Coffelt J, Parmley WW, Mason DT. The cardiac hypertrophy process. Analyses of factors determining pathological vs physiological development. Circ Res. 1979;45:697–707. doi: 10.1161/01.res.45.6.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamilton N, Ianuzzo CD. Contractile and calcium regulating capacities of myocardia of different sized mammals scale with resting heart rate. Mol Cell Biochem. 1991;106:133–141. doi: 10.1007/BF00230179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laughlin MH, Hale CC, Novela L, Gute D, Hamilton N, Ianuzzo CD. Biochemical characterization of exercise-trained porcine myocardium. J Appl Physiol. 1991;71:229–235. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.71.1.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breisch EA, White FC, Nimmo LE, McKirnan MD, Bloor CM. Exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy: a correlation of blood flow and microvasculature. J Appl Physiol. 1986;60:1259–1267. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.60.4.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White FC, McKirnan MD, Breisch EA, Guth BD, Liu YM, Bloor CM. Adaptation of the left ventricle to exercise-induced hypertrophy. J Appl Physiol. 1987;62:1097–1110. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.62.3.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffin KL, Laughlin MH, Parker JL. Exercise training improves endothelium-mediated vasorelaxation after chronic coronary occlusion. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:1948–1956. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.5.1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.White FC, Bloor CM. Coronary vascular remodeling and coronary resistance during chronic ischemia. Am J Cardiovasc Pathol. 1992;4:193–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gidh-Jain M, Huang B, Jain P, Gick G, El-Sherif N. Alterations in cardiac gene expression during ventricular remodeling following experimental myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1998;30:627–637. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mercadier JJ, Lompre AM, Wisnewsky C, Samuel JL, Bercovici J, Swynghedauw B, Schwartz K. Myosin isoenzyme changes in several models of rat cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 1981;49:525–532. doi: 10.1161/01.res.49.2.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ning XH, Zhang J, Liu J, Ye Y, Chen SH, From AH, Bache RJ, Portman MA. Ejection- and isovolumic contraction-phase wall thickening in nonischemic myocardium during coronary occlusion. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:H490–499. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.258.2.H490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mercadier JJ, Samuel JL, Michel JB, Zongazo MA, de la Bastie D, Lompre AM, Wisnewsky C, Rappaport L, Levy B, Schwartz K. Atrial natriuretic factor gene expression in rat ventricle during experimental hypertension. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:H979–987. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.3.H979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carroll SM, Nimmo LE, Knoepfler PS, White FC, Bloor CM. Gene expression in a swine model of right ventricular hypertrophy: intercellular adhesion molecule, vascular endothelial growth factor and plasminogen activators are upregulated during pressure overload. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1995;27:1427–1441. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1995.0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hystad ME, Klinge R, Spurkland A, Attramadal H, Hall C. Contrasting cardiac regional responses of A-type and B-type natriuretic peptide to experimental chronic heart failure. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2000;60:299–309. doi: 10.1080/003655100750046468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edwards JG. Swim training increases ventricular atrial natriuretic factor (ANF) gene expression as an early adaptation to chronic exercise. Life Sci. 2002;70:2753–2768. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)01518-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mantymaa P, Arokoski J, Porsti I, Perhonen M, Arvola P, Helminen HJ, Takala TE, Leppaluoto J, Ruskoaho H. Effect of endurance training on atrial natriuretic peptide gene expression in normal and hypertrophied hearts. J Appl Physiol. 1994;76:1184–1194. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.3.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calderone A, Murphy RJ, Lavoie J, Colombo F, Beliveau L. TGF-beta(1) and prepro-ANP mRNAs are differentially regulated in exercise-induced cardiac hypertrophy. J Appl Physiol. 2002;91:771–776. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.2.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Younes A, Boluyt MO, O’Neill L, Meredith AL, Crow MT, *Lakatta EG. Age-associated increase in rat ventricular ANP gene expression correlates with cardiac hypertrophy. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:H1003–H1008. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.3.H1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kinugawa K, Yonekura K, Ribeiro RC, Eto Y, Aoyagi T, Baxter JD, Camacho SA, Bristow MR, Long CS, Simpson PC. Regulation of thyroid hormone receptor isoforms in physiological and pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2001;89:591–598. doi: 10.1161/hh1901.096706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schaible TF, Malhotra A, Ciambrone G, Scheuer J. Chronic swimming reverses cardiac dysfunction and myosin abnormalities in hypertensive rats. J Appl Physiol. 1986;60:1435–1441. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.60.4.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scheuer J, Malhotra A, Hirsch C, Capasso J, Schaible TF. Physiologic cardiac hypertrophy corrects contractile protein abnormalities associated with pathologic hypertrophy in rats. J Clin Invest. 1982;70:1300–1305. doi: 10.1172/JCI110729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowes BD, Minobe W, Abraham WT, Rizeq MN, Bohlmeyer TJ, Quaife RA, Roden RL, Dutcher DL, Robertson AD, Voelkel NF, Badesch DB, Groves BM, Gilbert EM, Bristow MR. Changes in gene expression in the intact human heart. Downregulation of alpha-myosin heavy chain in hypertrophied, failing ventricular myocardium. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2315–2324. doi: 10.1172/JCI119770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyata S, Minobe W, Bristow MR, Leinwand LA. Myosin heavy chain isoform expression in the failing and nonfailing human heart. Circ Res. 2000;86:386–390. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.4.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakao K, Minobe W, Roden R, Bristow MR, Leinwand LA. Myosin heavy chain gene expression in human heart failure. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2362–2370. doi: 10.1172/JCI119776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alpert NR, Mulieri LA. The functional significance of altered tension dependent heat in thyrotoxic myocardial hypertrophy. Basic Res Cardiol. 1980;75:179–184. doi: 10.1007/BF02001411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pagani ED, Julian FJ. Rabbit papillary muscle myosin isozymes and the velocity of muscle shortening. Circ Res. 1984;54:586–594. doi: 10.1161/01.res.54.5.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwartz KY, Lecarpentier JL, Lompre AM, Mercadier JJ, Swynghedauw B. Myosin isoenzymic distribution correlates with speed of myocardial contraction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1981;13:1071–1075. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(81)90297-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boluyt MO, O’Neill L, Meredith AL, Bing OHL, Brooks WW, Conrad CH, Crow MT, Lakatta EG. Alterations in cardiac gene expression during the transition from stable hypertrophy to heart failure: Marked upregulation of genes encoding extracellular matrix proteins. Circ Res. 1994;75:23–32. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Villareal FJ, Dillman WH. Cardiac hypertrophy-induced changes in mRNA levels for TGF-β1, fibronectin, and collagen. Am J Physiol. 1992;31:H1861–H1866. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.6.H1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hefti M, Harder B, Eppenberger H, Schaub M. Signaling pathways in cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:2873–2892. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sugden PH, Clerk A. Regulation of the ERK subgroup of MAP kinase cascades through G protein-coupled receptors. Cell Signal. 1997;9:337–351. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(96)00191-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sugden PH. Signaling in myocardial hypertrophy: Life after Calcineurin? Circ Res. 1999;84:633–646. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.6.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bueno OF, De Windt J, Tymitz KM, Witt SA, Kimball TR, Klevitsky R, Hewitt TE, Jones SP, Lefer DJ, Peng C-F, Kitsis RN, Molkentin JD. The MEK1-ERK1/2 signaling pathway promotes compensated cardiac hypertrophy in transgenic mice. EMBO J. 2000;19:6341–6350. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.23.6341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iemitsu M, Maeda S, Jesmin S, Otsuki T, Kasuya Y, Miyauchi T. Activation pattern of MAPK signaling in the hearts of trained and untrained rats following a single bout of exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2006 doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00392.2005. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takeishi Y, Huang Q, Abe J, Glassman M, Che W, Lee JD, Kawakatsu H, Lawrence EG, Hoit BD, Berk BC, Walsh RA. Src and multiple MAP kinase activation in cardiac hypertrophy and congestive heart failure under chronic pressure-overload: comparison with acute mechanical stretch. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:1637–48. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tipton CM, Carey RA, Eastin WC, Erickson HH. A submaximal test for dogs: evaluation of the effects of exercise training, detraining, and cage confinement. J Appl Physiol. 1974;37:271–275. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1974.37.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Griffin KL, Woodman CR, Price EM, Laughlin MH, Parker JL. Endothelium-mediated relaxation of porcine collateral-dependent arterioles is improved by exercise training. Circulation. 2001;104:1393–1398. doi: 10.1161/hc3601.094274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson LR, Parker JL, Laughlin MH. Chronic exercise training improves Ach-induced vasorelaxation in pulmonary arteries of pigs. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88:443–451. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.2.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chu ML, Weil D, de Wet W, Berard M, Sippola M, Ramirez F. Isolation of cDNA and genomic clones encoding human pro-α1(III) collagen. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:4357–4363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eisenberg BR, Edwards JA, Zak R. Transmural distribution of isomyosin in rabbit ventricle during maturation examined by immunofluorescence and staining for calcium-activated adenosine triphosphatase. Circ Res. 1985;56:548–555. doi: 10.1161/01.res.56.4.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bugaisky LB, Anderson PG, Hall RS, Bishop SP. Differences in myosin isoform expression in the subepicardial and subendocardial myocardium during cardiac hypertrophy in the rat. Circ Res. 1990;66:1127–1132. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.4.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoh JFY, McGrath PA, Hale PT. Electrophoretic analysis of multiple forms of rat cardiac myosin: Effects of hypophysectomy and thyroxine replacement. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1977;10:1053–1076. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(78)90401-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kinugawa K, Minobe WA, Wood WM, Ridgway EC, Baxter JD, Ribeiro RC, Tawadrous MF, Lowes BA, Long CS, Bristow MR. Signaling pathways responsible for fetal gene induction in the failing human heart: evidence for altered thyroid hormone receptor gene expression. Circulation. 2001;103:1089–1094. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.8.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moore R, Korzick D. Cellular adaptations of the myocardium to chronic exercise. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1995;37:371–396. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(05)80019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Orenstein TL, Parker TG, Butany JW, Goodman JM, Dawood F, Wen WH, Wee L, Martino T, McLaughlin PR, Liu PP. Favorable left ventricular remodeling following large myocardial infarction by exercise training. Effect on ventricular morphology and gene expression. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:858–866. doi: 10.1172/JCI118132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scheinowitz M, Kessler-Icekson G, Freimann S, Zimmermann R, Schaper W, Golomb E, Savion N, Eldar M. Short- and long-term swimming exercise training increases myocardial insulin-like growth factor-I gene expression. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2003;13:19–25. doi: 10.1016/s1096-6374(02)00137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jin H, Yang R, Li W, Lu H, Ryan AM, Ogasawara AK, Van Peborgh J, Paoni NF. Effects of exercise training on cardiac function, gene expression, and apoptosis in rats. Am J Physiol. 2000;279:H2994–3002. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.6.H2994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thomas DP, McCormick RJ, Zimmerman SD, Vadlamudi RK, Gosselin LE. Aging- and training-induced alterations in collagen characteristics of rat left ventricle and papillary muscle. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:H778–H783. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.3.H778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thomas DP, Zimmerman SD, Hansen TR, Martin DT, McCormick RJ. Collagen gene expression in rat left ventricle: interactive effect of age and exercise training. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89:1462–1468. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.4.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thomas DP, Cotter TA, Li X, McCormick RJ, Gosselin LE. Exercise training attenuates aging-associated increases in collagen and collagen crosslinking of the left but not the right ventricle in the rat. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2001;85:164–169. doi: 10.1007/s004210100447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hunter JC, Korzick DH. Age- and sex-dependent alterations in protein kinase C (PKC) and extracellular regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) in rat myocardium. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;126:535–550. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kuroski de Bold ML. Atrial natriuretic factor and brain natriuretic peptide gene expression in the spontaneous hypertensive rat during postnatal development. Am J Hypertens. 1998;11:1006–1018. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(98)00116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maris ME, Melchert RB, Joseph J, Kennedy RH. Gender differences in blood pressure and heart rate in spontaneously hypertensive and Wistar-Kyoto rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2005;32:35–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2005.04156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Palmer BM. Thick filament proteins and performance in human heart failure. Heart Failure Rev. 2005;10:187–197. doi: 10.1007/s10741-005-5249-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Boluyt MO, Li ZB, Loyd AM, Scalia AF, Cirrincione GM, Jackson RR. The mTOR/p70S6K signal transduction pathway plays a role in cardiac hypertrophy and influences expression of myosin heavy chain genes in vivo. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2004;18:257–267. doi: 10.1023/B:CARD.0000041245.61136.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cirrincione GM, Boluyt MO, Hwang HS, Bleske BE. 3-Hydroxy–3-Methyl-Glutaryl Coenzyme A Reductase Inhibition and Extracellular Matrix Gene Expression in the Pressure-Overloaded Rat Heart. J Cardiovasc Pharm. doi: 10.1097/01.fjc.0000211745.70831.75. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bridgman P, Aronovitz MA, Kakkar R, Oliverio MI, Coffman TM, Rand WM, Konstam MA, Mendelsohn ME, Patten RD. Gender-specific patterns of left ventricular and myocyte remodeling following myocardial infarction in mice deficient in the angiotensin II type 1a receptor. Am J Physiol. 2005;289:H586–592. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00474.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jin H, Yang R, Li W, Lu H, Ryan AM, Ogasawara AK, Van Peborgh J, Paoni NF. Effects of exercise training on cardiac function, gene expression, and apoptosis in rats. Am J Physiol. 2000;279:H2994–3002. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.6.H2994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lefaucheur L, Hoffman R, Okamura C, Gerrard D, Leger JJ, Rubinstein N, Kelly A. Transitory expression of alpha cardiac myosin heavy chain in a subpopulation of secondary generation muscle fibers in the pig. Dev Dyn. 1997;210:106–116. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199710)210:2<106::AID-AJA4>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Srere PA. Citrate synthase. Methods Enzymol. 1969;13:3–5. [Google Scholar]