Abstract

Background

BAFF and APRIL share two receptors – TACI and BCMA – and BAFF binds to a third receptor, BAFF-R. Increased expression of BAFF and APRIL is noted in hematological malignancies. BAFF and APRIL are essential for the survival of normal and malignant B lymphocytes, and altered expression of BAFF or APRIL or of their receptors (BCMA, TACI, or BAFF-R) have been reported in various B-cell malignancies including B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Hodgkin's lymphoma, multiple myeloma, and Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia.

Methods

We compared the expression of BAFF, APRIL, TACI and BAFF-R gene expression in 40 human tumor types – brain, epithelial, lymphoid, germ cells – to that of their normal tissue counterparts using publicly available gene expression data, including the Oncomine Cancer Microarray database.

Results

We found significant overexpression of TACI in multiple myeloma and thyroid carcinoma and an association between TACI expression and prognosis in lymphoma. Furthermore, BAFF and APRIL are overexpressed in many cancers and we show that APRIL expression is associated with tumor progression. We also found overexpression of at least one proteoglycan with heparan sulfate chains (HS), which are coreceptors for APRIL and TACI, in tumors where APRIL is either overexpressed or is a prognostic factor. APRIL could induce survival or proliferation directly through HS proteoglycans.

Conclusion

Taken together, these data suggest that APRIL is a potential prognostic factor for a large array of malignancies.

Background

APRIL and BAFF are two members of the TNF family. BAFF is a type II transmembrane protein that can be secreted after proteolytical cleavage from the cell membrane[1,2]. APRIL is processed intracellularly within the Golgi apparatus by a furin pro-protein convertase prior to secretion of the biologically active form[3]. APRIL can also be expressed as a cell surface fusion protein with TWEAK called TWE-PRIL[4,5]. Both ligands bind to TACI (transmembrane activator and CAML interactor) and BCMA (B-cell maturation antigen), two members of the TNFR family. BAFF binds additionally to BAFF receptor (BAFF-R). BAFF is involved in the survival of normal and malignant B cells and normal plasmablasts [6-8]. APRIL is highly expressed in several tumor tissues, stimulates the growth of tumor cells[9] and promotes survival of normal plasmablasts and plasma cells[10,11].

Evidence has been presented that BAFF/APRIL contribute to malignancies of B cells and plasma cells: non-Hodgkin's lymphoma [12-16], Hodgkin lymphoma[17], chronic lymphocytic leukemia[18,19], multiple myeloma [20-24] and Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia[25].

Recombinant APRIL binds to several cell lines that do not express detectable mRNA for TACI and BCMA and proteoglycans were identified as APRIL-specific binding partners. This binding is mediated by heparan sulfate (HS) side chains and can be inhibited by heparin[26,27]. Binding of APRIL to proteoglycans or BCMA/TACI involves different regions in APRIL. APRIL binds HS proteoglycans via the lysine-rich region in the N-terminal part, leaving the TNF-like region available to interact with others receptors. Blockade of APRIL/BAFF using human BCMA-Ig in nude mice inhibited the growth of a subcutaneously injected human lung carcinoma cell line (A549) and a human colon carcinoma cell line (HT29)[28]. These cell lines express APRIL, but not BAFF, TACI, BCMA or BAFF-R suggesting that HS proteoglycans could mediate the growth response to APRIL. However, BCMA-Fc leaves the APRIL binding HSPG domain intact. This blockade may suggest that the TNF-receptor binding domain is also necessary for activity, and that an additional APRIL-specific receptor might exist. B-cell lymphoma cells can bind large amount of APRIL secreted by neutrophils via proteoglycan binding and the high expression of APRIL in tumor lesion correlates with B-cell lymphoma aggressiveness[16]. More recently, Bischof et al demonstrated that TACI binds also HS proteoglycans like syndecan-1, syndecan-2 and syndecan-4 [29].

These data demonstrate that BAFF/APRIL are potent growth factors in B cell malignancies. Furthermore, APRIL could be implicated in tumor emergence and/or progression due to its ability to bind HS proteoglycans [26-28]. Therefore, we looked for the expression of BAFF, APRIL and of their receptors – BAFF-R, BCMA, and TACI – in various cancers, compared to their normal tissue or cell counterparts and in association with disease staging.

Methods

Databases

We used Oncomine Cancer Microarray database http://www.oncomine.org[30] and Amazonia database http://amazonia.montp.inserm.fr/[31] to study gene expression of BAFF, APRIL, BCMA, TACI, BAFF-R and HS proteoglycans genes in 40 human tumor types and their normal tissue counterparts as indicated in Table 1 (Additional file 1). Only gene expression data obtained from a single study using the same methodology were compared. All data were log transformed, median centred per array, and the standard deviation was normalized to one per array[32].

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons were done with Mann-Whitney or Student t-tests.

Results and Discussion

BAFF is overexpressed in solid tumors

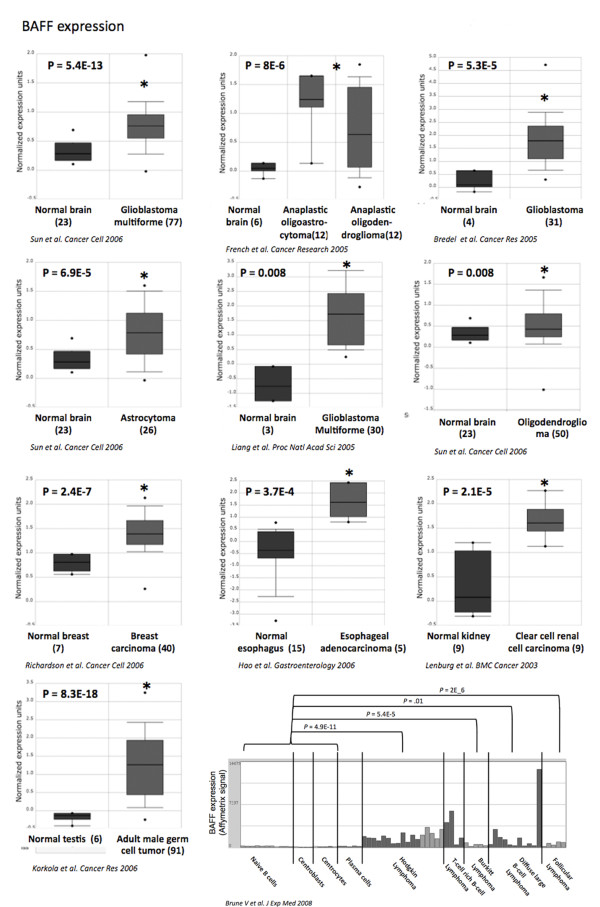

40 tumor types were investigated, including 36 solid tumors and 4 hematological tumors (Additional file 1: Table 1). BAFF gene is overexpressed in 1/4 hematological tumors and in 5/36 solid tumors. BAFF is overexpressed in Hodgkin lymhoma compared to normal B cells (P = 4.9E-11), in Burkitt lymphoma compared to normal B cells (P = 5.4E-5), in diffuse large B cell lymphoma compared to normal B cells (P = .01) and in follicular lymphoma compared to normal B cells (P = 2E-6)[33]. Four independent studies have shown BAFF overexpression in glioblastoma compared to normal brain (P = 5.4E-13, P = 8E-6, P = 5.3E-5 and P = 0.008) [34-37] (Figure 1). Following stimulation with inflammatory cytokines, astrocytes in vitro produce high amounts of BAFF. BAFF is expressed in astrocytes in the normal human central nervous system and is strongly upregulated in activated astrocytes in the demyelinated lesions of multiple sclerosis[38]. BAFF secretion could be relevant in sustaining intrathecal B cell responses in autoimmune and infectious diseases of the central nervous system. Accordingly, BAFF expression is readily induced in the central nervous system by neurotrophic viruses and correlates with the recruitment of antibody-secreting cells[39]. The overexpression of BAFF in brain tumors could be linked to the accumulation of tumor cells or to inflammatory signals. Regarding other cancers, BAFF was found significantly overexpressed in breast carcinoma compared to normal breast (Richardson et al[40]; P = 2.4E-7), in esophageal adenocarcinoma compared to normal esophagus (Hao et al[41]; P = 3.7E-4), in clear cell renal cell carcinoma compared to normal kidney (Lenburg et al[42]; P = 2.1E-5) and in adult male germ cell tumor compared to normal testis (Korkola et al[43]; P = 8.3E-18).

Figure 1.

BAFF expression in various cancers. BAFF gene expression in normal brain, glioblastoma multiforme [34-37], normal breast, breast carcinoma[40], normal esophagus, esophageal adenocarcinoma[41], normal kidney, renal carcinoma[42], normal testis, adult male germ cell tumor[43], Hodgkin lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma[33]. Data sets in a single panel were from the same study. GEP data are log transformed and normalized as previously described[32]. In brackets, are indicated the number of normal or tumor samples.

APRIL is overexpressed in solid and hematological malignancies

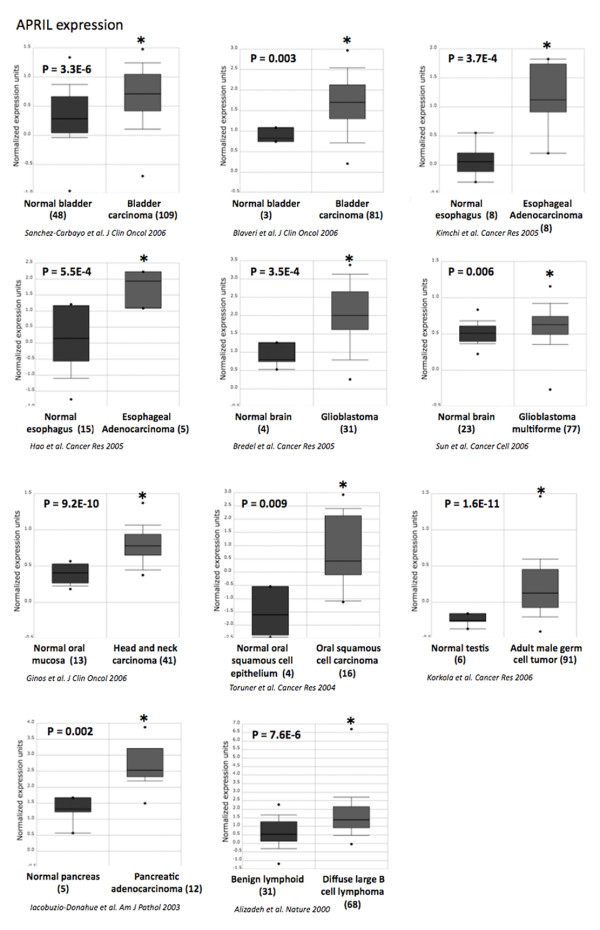

APRIL gene was overexpressed in 1/4 hematological and in 6/36 solid tumors in tumors (Additional file 1: Table 1). APRIL was overexpressed in invasive bladder carcinoma compared to superficial bladder carcinoma in two independent studies (P = 3.3E-6 and P = 0.003)[44,45], in esophageal adenocarcinoma compared to normal esophagus in two independent studies (P = 3.7E-4 and P = 5.5E-4)[41,46], in glioblastoma compared to normal brain in two independent studies (P = 3.5E-4 and P = 0.006)[34,36], in head and neck carcinoma compared to normal oral mucosa in two independent studies (P = 9.2E-10 and P = 0.009)[47,48], in diffuse large B cell lymphoma compared to normal lymph nodes (P = 7.6E-6)[49,50], in pancreatic adenocarcinoma compared to normal pancreas (Iocobuzio-Donahue et al[51]; P = 0.002) and in adult male germ cell tumor compared to normal testis (Korkola et al[43]; P = 1.6E-11) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

APRIL expression in various cancers. APRIL gene expression in normal bladder, bladder carcinoma[44,45], normal esophagus, esophageal adenocarcinoma[41,46], normal brain, glioblastoma multiform[34,36], normal oral mucosa, head and neck carcinoma[47,48], normal B cell, lymphoma[49,50], normal pancreas, pancreatic adenocarcinoma[51], normal testis and adult male germ cell tumor[43]. Data sets in a single panel were from the same study. GEP data are log transformed and normalized as previously described[32]. In brackets, are indicated the number of normal or tumor samples.

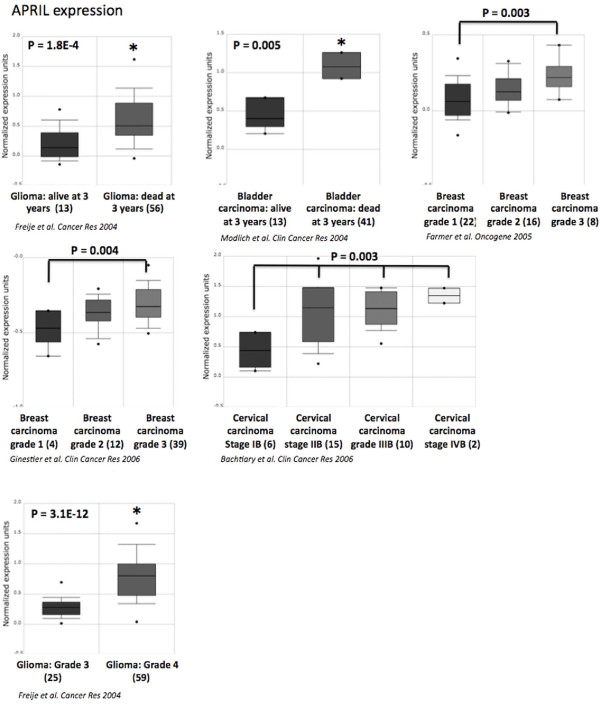

Recently, Schwaller et al[16] demonstrated that high APRIL expression in tumor lesions correlates with B-cell lymphoma aggressiveness. We found here that BAFF or APRIL expression could be also associated with tumor aggressiveness in other cancers (Figure 3). APRIL is significantly overexpressed in glioma grade 4 compared to glioma grade 3 (P = 3.1E-12) and in patients presenting glioma, dead at 3 years compared to patients alive at 3 years (P = 1.8E-4)[52] (Additional file 2). In bladder carcinoma, APRIL is overexpressed in patients dead at 3 years compared to patients alive at 3 years (P = .005)[53]. High tumor cell mass in breast cancer was also characterized by increased APRIL expression in two independent studies (P = .003 and P = .004)[54,55]. Stages II, III and IV cervical carcinoma showed an overexpression of APRIL compared to stage I (P = 0.003)[56] (Figure 3). On the contrary, BAFF overexpression was not associated with prognosis or tumor aggressiveness using online cancer gene expression analysis[32]. APRIL protein was detected in several human solid tumors[57] and normal epithelial cells[11]. Interestingly, APRIL protein expression was reported in larynx and oral cavity carcinoma, esophagus carcinoma, bladder carcinoma, breast cancer, pancreatic tumors, ovarian carcinoma, seminoma adenocarcinoma, glioblastoma multiforme and oligodendroglioma correlating with the results of our analysis[57,58]. In addition, neutrophils, present in the stroma of solid tumors, are major producers of APRIL [57] suggesting that APRIL overexpression may be due to infiltrating cells. Furthermore, APRIL that is produced in tumors is retained and accumulates in the tumor stroma though HSPG binding[57]. Nevertheless, an upregulation of APRIL protein (detected by in situ immunostaining) was shown to not alter disease-free and overall survivals of bladder, ovarian and head and neck carcinoma patients in retrospective studies[58]. We have identified here a significant overexpression of APRIL in patients with glioma or bladder carcinomas who were dead at 3 years compared to patients alive at 3 years. An explanation could be that a part of APRIL protein is quickly secreted and no more detectable by immunostaining. APRIL protein could also be used by tumor cells as a growth factor or released in the blood circulation.

Figure 3.

Association between APRIL expression and aggressiveness in various cancers. APRIL gene expression in glioma[52], bladder carcinoma[53], breast carcinoma[54,55] and cervical carcinoma[56]. Data sets in a single panel were from the same study. GEP data are log transformed and normalized as previously described[32]. In brackets, are indicated the number of normal or tumor samples.

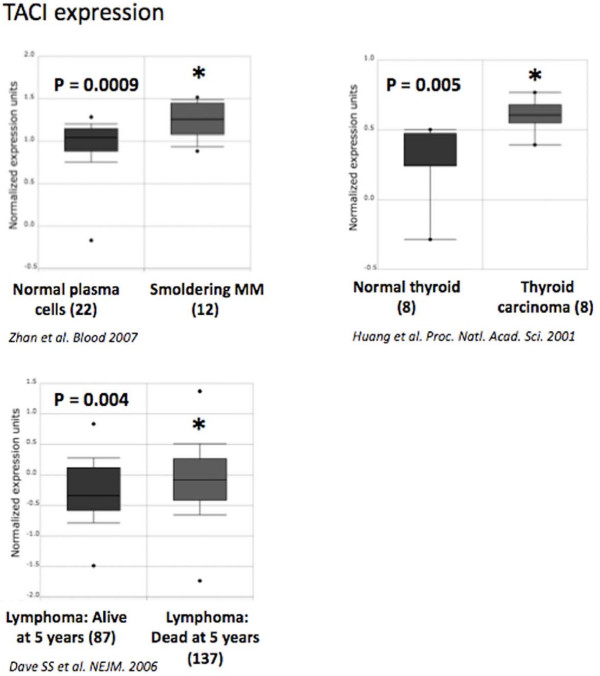

TACI is overexpressed in hematological cancers

We have previously reported the relevance of Affymetrix microarrays to quantify BCMA and TACI expressions in MM since microarray data were validated by real time RT-PCR and flow cytometry[20,21,59]. No differences in BCMA or BAFF-R expression between tumor cells and their normal counterparts could be found in the 40 cancer types available from Oncomine database. By contrast, a significant TACI overexpression was found in smoldering myeloma compared to normal plasma cells (Zhan et al[60]; P = 0.0009) and in thyroid carcinomas compared to normal thyroid (Huang et al[61]; P = 0.005) (Figure 4). Interestingly, we found that TACI expression is associated with a poor prognosis in Burkitt lymphoma. TACI is significantly overexpressed in patients presenting Burkitt lymphoma who were dead at five years compared to patients alive at five years (Dave et al[62]; P = 0.004) (Figure 4). Recently, it was described that APRIL-TACI interactions mediate non-Hodgkin lymphoma B-cell proliferation through Akt, regulating cyclin D1 and P21 expression[63]. These data suggest that TACI is the main receptor for BAFF/APRIL in lymphoma cells and is associated with a bad prognosis. TACI therefore represents a potential lymphoma therapeutic target.

Figure 4.

TACI expression in various cancers. TACI gene expression in normal plasma cells, smoldering myeloma[60], normal thyroid, thyroid carcinoma[61] and lymphoma[62]. Data sets in a single panel were from the same study. GEP data are log transformed and normalized as previously described[32]. In brackets, are indicated the number of normal or tumor samples.

Correlations between APRIL and heparan sulfate chain proteoglycans overexpression in tumor cells

Receptors for BAFF and APRIL are expressed exclusively by lymphoid cells. APRIL can bind and promote tumor-cell proliferation of several cell lines that do not express detectable mRNA for TACI and BCMA[9,64,65]. Ingold et al and Hendriks at al identified proteoglycans as the APRIL-non specific binding partners. This binding is mediated by HS side chains and can be inhibited by heparin[26,27]. Only APRIL expression was associated with a bad prognosis in several cancers. APRIL could sustain the survival of malignant cells directly through HS proteoglycans that can deliver signals through their intracellular tails upon binding to ligands[66,67].

Eleven HS proteoglycans has been identified so far – syndecan 1–4, glypican 1–6, CD44 isoforms containing the alternatively spliced exon v3 – and their gene expression can be evaluated by microarrays[68] (see Additional file 3). Interestingly, at least one HS proteoglycan gene was significantly overexpressed in cancers presenting an overexpression of APRIL compared to their normal counterparts (see Additional file 1). A similar observation was made for cancers showing an association between APRIL expression and the evolution of the disease (see Additional file 1).

HS proteoglycans regulate growth factor signaling, cytoskeleton organization, cell adhesion and migration[69]. HS proteoglycans are implicated in solid tumor development[70,71]. Syndecan-1 is absolutely required for the development of mammary tumors driven by the transgenic expression of the proto-oncogene Wnt-1 in mice[72]. The important role of HS proteoglycans is attributed in part to its highly negative electric potential, making it able to bind numerous proteins and to function as a coreceptor. However as APRIL activates cells that do not express TACI or BCMA, a direct signaling by the HS proteoglycans core protein is possible as already shown [66]. It may explain the overexpression of APRIL in association with disease aggressiveness in solid tumors which do not express BCMA or TACI. Nevertheless, additional studies are required to understand the exact role of APRIL in solid tumors, the existence of a signaling linked to the interaction of APRIL with HS proteoglycans and the possible existence of a receptor specific to APRIL not yet identified.

Conclusion

The analysis reported here demonstrates that APRIL mRNA is overexpressed in at least 8 cancers compared to their normal counterparts, and within a given tumor category, is associated with a bad prognosis. These observations emphasize the interest using BAFF/APRIL inhibitors in the treatment of patients with cancers. We recently completed a phase I-II clinical trial of Atacicept TACI-Fc inhibitor showing the feasibility and safety of this targeting in multiple myeloma (submitted data). Heparin could be also useful in blocking APRIL binding to surface HS proteoglycan. Of note, we found here always one HS proteoglycan gene overexpressed in tumors that also highly expressed APRIL. A recent study reported that a brief course of subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin favorably influences the survival in patients with advanced malignancy and deserves additional clinical evaluation[73]. Thus, the targeting of APRIL or its interaction with HS proteoglycans may be promising in a large number of cancers.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

JM designed research, performed the analyses and wrote the paper. JLV and JDV have been involved in drafting and reviewing of the manuscript. BK is the senior investigator who designed research and wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Supplementary Material

Expression of BAFF, APRIL, TACI, BAFF-R and heparan sulfate proteoglycans in human tumor types to that of their normal tissue counterparts using publicly available gene expression data, including the Oncomine Cancer Microarray database.

Classification of cancers included in the analysis.

Gene expression profile of Syndecan 1–4 and glypican 1–6 was determined using Oncomine Cancer Microarray database in bladder carcinoma, esophagus adenocarcinoma, brain tumors, breast cancer, head and neck tumors, lymphoma, pancreatic adenocarcinoma and adult male germ cell tumors presenting an overexpression of APRIL or an association with a bad prognosis or tumor progression.

Contributor Information

Jérôme Moreaux, Email: jerome.moreaux@inserm.fr.

Jean-Luc Veyrune, Email: jean-luc.veyrune@inserm.fr.

John De Vos, Email: john.devos@inserm.fr.

Bernard Klein, Email: bernard.klein@inserm.fr.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer (équipe labellisée 2006), Paris, France, from INCA (n°R07001FN) and from MSCNET European strep (N°E06005FF).

References

- Nardelli B, Belvedere O, Roschke V, Moore PA, Olsen HS, Migone TS, Sosnovtseva S, Carrell JA, Feng P, Giri JG. Synthesis and release of B-lymphocyte stimulator from myeloid cells. Blood. 2001;97(1):198–204. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider P, MacKay F, Steiner V, Hofmann K, Bodmer JL, Holler N, Ambrose C, Lawton P, Bixler S, Acha-Orbea H. BAFF, a novel ligand of the tumor necrosis factor family, stimulates B cell growth. J Exp Med. 1999;189(11):1747–1756. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.11.1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Fraga M, Fernandez R, Albar JP, Hahne M. Biologically active APRIL is secreted following intracellular processing in the Golgi apparatus by furin convertase. EMBO Rep. 2001;2(10):945–951. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolfschoten GM, Pradet-Balade B, Hahne M, Medema JP. TWE-PRIL; a fusion protein of TWEAK and APRIL. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66(8):1427–1432. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(03)00493-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradet-Balade B, Medema JP, Lopez-Fraga M, Lozano JC, Kolfschoten GM, Picard A, Martinez AC, Garcia-Sanz JA, Hahne M. An endogenous hybrid mRNA encodes TWE-PRIL, a functional cell surface TWEAK-APRIL fusion protein. Embo J. 2002;21(21):5711–5720. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery DT, Kalled SL, Ellyard JI, Ambrose C, Bixler SA, Thien M, Brink R, Mackay F, Hodgkin PD, Tangye SG. BAFF selectively enhances the survival of plasmablasts generated from human memory B cells. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(2):286–297. doi: 10.1172/JCI18025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossen C, Cachero TG, Tardivel A, Ingold K, Willen L, Dobles M, Scott ML, Maquelin A, Belnoue E, Siegrist CA. TACI, unlike BAFF-R, is solely activated by oligomeric BAFF and APRIL to support survival of activated B cells and plasmablasts. Blood. 2008;111(3):1004–1012. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-110874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay F, Schneider P, Rennert P, Browning J. BAFF AND APRIL: A Tutorial on B Cell Survival. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:231–264. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahne M, Kataoka T, Schroter M, Hofmann K, Irmler M, Bodmer JL, Schneider P, Bornand T, Holler N, French LE. APRIL, a new ligand of the tumor necrosis factor family, stimulates tumor cell growth. J Exp Med. 1998;188(6):1185–1190. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.6.1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belnoue E, Pihlgren M, McGaha TL, Tougne C, Rochat AF, Bossen C, Schneider P, Huard B, Lambert PH, Siegrist CA. APRIL is critical for plasmablast survival in the bone marrow and poorly expressed by early life bone marrow stromal cells. Blood. 2008;111(5):2755–2764. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-110858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huard B, McKee T, Bosshard C, Durual S, Matthes T, Myit S, Donze O, Frossard C, Chizzolini C, Favre C. APRIL secreted by neutrophils binds to heparan sulfate proteoglycans to create plasma cell niches in human mucosa. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(8):2887–2895. doi: 10.1172/JCI33760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briones J, Timmerman JM, Hilbert DM, Levy R. BLyS and BLyS receptor expression in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Exp Hematol. 2002;30(2):135–141. doi: 10.1016/S0301-472X(01)00774-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu L, Lin-Lee YC, Pham LV, Tamayo A, Yoshimura L, Ford RJ. Constitutive NF-kappaB and NFAT activation leads to stimulation of the BLyS survival pathway in aggressive B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2006;107(11):4540–4548. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He B, Chadburn A, Jou E, Schattner EJ, Knowles DM, Cerutti A. Lymphoma B cells evade apoptosis through the TNF family members BAFF/BLyS and APRIL. J Immunol. 2004;172(5):3268–3279. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.3268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak AJ, Grote DM, Stenson M, Ziesmer SC, Witzig TE, Habermann TM, Harder B, Ristow KM, Bram RJ, Jelinek DF. Expression of BLyS and Its Receptors in B-Cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: Correlation With Disease Activity and Patient Outcome. Blood. 2004;104(8):2247–2253. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwaller J, Schneider P, Mhawech-Fauceglia P, McKee T, Myit S, Matthes T, Tschopp J, Donze O, Le Gal FA, Huard B. Neutrophil-derived APRIL concentrated in tumor lesions by proteoglycans correlates with human B-cell lymphoma aggressiveness. Blood. 2007;109(1):331–338. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-001800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu A, Xu W, He B, Dillon SR, Gross JA, Sievers E, Qiao X, Santini P, Hyjek E, Lee JW. Hodgkin lymphoma cells express TACI and BCMA receptors and generate survival and proliferation signals in response to BAFF and APRIL. Blood. 2007;109(2):729–739. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-015958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern C, Cornuel JF, Billard C, Tang R, Rouillard D, Stenou V, Defrance T, Ajchenbaum-Cymbalista F, Simonin PY, Feldblum S. Involvement of BAFF and APRIL in the resistance to apoptosis of B-CLL through an autocrine pathway. Blood. 2004;103(2):679–688. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak AJ, Bram RJ, Kay NE, Jelinek DF. Aberrant expression of B-lymphocyte stimulator by B chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells: a mechanism for survival. Blood. 2002;100(8):2973–2979. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreaux J, Cremer FW, Reme T, Raab M, Mahtouk K, Kaukel P, Pantesco V, De Vos J, Jourdan E, Jauch A. The level of TACI gene expression in myeloma cells is associated with a signature of microenvironment dependence versus a plasmablastic signature. Blood. 2005;106(3):1021–1030. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreaux J, Hose D, Jourdan M, Reme T, Hundemer M, Moos M, Robert N, Moine P, De Vos J, Goldschmidt H. TACI expression is associated with a mature bone marrow plasma cell signature and C-MAF overexpression in human myeloma cell lines. Haematologica. 2007;92(6):803–811. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreaux J, Legouffe E, Jourdan E, Quittet P, Reme T, Lugagne C, Moine P, Rossi JF, Klein B, Tarte K. BAFF and APRIL protect myeloma cells from apoptosis induced by interleukin 6 deprivation and dexamethasone. Blood. 2004;103(8):3148–3157. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak AJ, Darce JR, Arendt BK, Harder B, Henderson K, Kindsvogel W, Gross JA, Greipp PR, Jelinek DF. Expression of BCMA, TACI, and BAFF-R in multiple myeloma: a mechanism for growth and survival. Blood. 2004;103(2):689–694. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaccoby S, Pennisi A, Li X, Dillon SR, Zhan F, Barlogie B, Shaughnessy JD Jr. Atacicept (TACI-Ig) inhibits growth of TACI(high) primary myeloma cells in SCID-hu mice and in coculture with osteoclasts. Leukemia. 2008;22(2):406–413. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsawa SF, Novak AJ, Grote DM, Ziesmer SC, Witzig TE, Kyle RA, Dillon SR, Harder B, Gross JA, Ansell SM. B-lymphocyte stimulator (BLyS) stimulates immunoglobulin production and malignant B-cell growth in Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Blood. 2006;107(7):2882–2888. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks J, Planelles L, de Jong-Odding J, Hardenberg G, Pals ST, Hahne M, Spaargaren M, Medema JP. Heparan sulfate proteoglycan binding promotes APRIL-induced tumor cell proliferation. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12(6):637–648. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingold K, Zumsteg A, Tardivel A, Huard B, Steiner QG, Cachero TG, Qiang F, Gorelik L, Kalled SL, Acha-Orbea H. Identification of proteoglycans as the APRIL-specific binding partners. J Exp Med. 2005;201(9):1375–1383. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennert P, Schneider P, Cachero TG, Thompson J, Trabach L, Hertig S, Holler N, Qian F, Mullen C, Strauch K. A soluble form of B cell maturation antigen, a receptor for the tumor necrosis factor family member APRIL, inhibits tumor cell growth. J Exp Med. 2000;192(11):1677–1684. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.11.1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischof D, Elsawa SF, Mantchev G, Yoon J, Michels GE, Nilson A, Sutor SL, Platt JL, Ansell SM, von Bulow G. Selective activation of TACI by syndecan-2. Blood. 2006;107(8):3235–3242. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes DR, Yu J, Shanker K, Deshpande N, Varambally R, Ghosh D, Barrette T, Pandey A, Chinnaiyan AM. Large-scale meta-analysis of cancer microarray data identifies common transcriptional profiles of neoplastic transformation and progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(25):9309–9314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401994101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assou S, Le Carrour T, Tondeur S, Strom S, Gabelle A, Marty S, Nadal L, Pantesco V, Reme T, Hugnot JP. A meta-analysis of human embryonic stem cells transcriptome integrated into a web-based expression atlas. Stem Cells. 2007;25(4):961–973. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes DR, Yu J, Shanker K, Deshpande N, Varambally R, Ghosh D, Barrette T, Pandey A, Chinnaiyan AM. ONCOMINE: a cancer microarray database and integrated data-mining platform. Neoplasia (New York, NY) 2004;6(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/s1476-5586(04)80047-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brune V, Tiacci E, Pfeil I, Doring C, Eckerle S, van Noesel CJ, Klapper W, Falini B, von Heydebreck A, Metzler D. Origin and pathogenesis of nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma as revealed by global gene expression analysis. J Exp Med. 2008;205(10):2251–2268. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredel M, Bredel C, Juric D, Harsh GR, Vogel H, Recht LD, Sikic BI. Functional network analysis reveals extended gliomagenesis pathway maps and three novel MYC-interacting genes in human gliomas. Cancer Res. 2005;65(19):8679–8689. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French PJ, Swagemakers SM, Nagel JH, Kouwenhoven MC, Brouwer E, Spek P van der, Luider TM, Kros JM, Bent MJ van den, Sillevis Smitt PA. Gene expression profiles associated with treatment response in oligodendrogliomas. Cancer Res. 2005;65(24):11335–11344. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Hui AM, Su Q, Vortmeyer A, Kotliarov Y, Pastorino S, Passaniti A, Menon J, Walling J, Bailey R. Neuronal and glioma-derived stem cell factor induces angiogenesis within the brain. Cancer Cell. 2006;9(4):287–300. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y, Diehn M, Watson N, Bollen AW, Aldape KD, Nicholas MK, Lamborn KR, Berger MS, Botstein D, Brown PO. Gene expression profiling reveals molecularly and clinically distinct subtypes of glioblastoma multiforme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(16):5814–5819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402870102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumbholz M, Theil D, Derfuss T, Rosenwald A, Schrader F, Monoranu CM, Kalled SL, Hess DM, Serafini B, Aloisi F. BAFF is produced by astrocytes and up-regulated in multiple sclerosis lesions and primary central nervous system lymphoma. J Exp Med. 2005;201(2):195–200. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschen SI, Stohlman SA, Ramakrishna C, Hinton DR, Atkinson RD, Bergmann CC. CNS viral infection diverts homing of antibody-secreting cells from lymphoid organs to the CNS. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36(3):603–612. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson AL, Wang ZC, De Nicolo A, Lu X, Brown M, Miron A, Liao X, Iglehart JD, Livingston DM, Ganesan S. X chromosomal abnormalities in basal-like human breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2006;9(2):121–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Y, Triadafilopoulos G, Sahbaie P, Young HS, Omary MB, Lowe AW. Gene expression profiling reveals stromal genes expressed in common between Barrett's esophagus and adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(3):925–933. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenburg ME, Liou LS, Gerry NP, Frampton GM, Cohen HT, Christman MF. Previously unidentified changes in renal cell carcinoma gene expression identified by parametric analysis of microarray data. BMC cancer. 2003;3:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-3-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korkola JE, Houldsworth J, Chadalavada RS, Olshen AB, Dobrzynski D, Reuter VE, Bosl GJ, Chaganti RS. Down-regulation of stem cell genes, including those in a 200-kb gene cluster at 12p13.31, is associated with in vivo differentiation of human male germ cell tumors. Cancer Res. 2006;66(2):820–827. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaveri E, Simko JP, Korkola JE, Brewer JL, Baehner F, Mehta K, Devries S, Koppie T, Pejavar S, Carroll P. Bladder cancer outcome and subtype classification by gene expression. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(11):4044–4055. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Carbayo M, Socci ND, Lozano J, Saint F, Cordon-Cardo C. Defining molecular profiles of poor outcome in patients with invasive bladder cancer using oligonucleotide microarrays. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(5):778–789. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimchi ET, Posner MC, Park JO, Darga TE, Kocherginsky M, Karrison T, Hart J, Smith KD, Mezhir JJ, Weichselbaum RR. Progression of Barrett's metaplasia to adenocarcinoma is associated with the suppression of the transcriptional programs of epidermal differentiation. Cancer Res. 2005;65(8):3146–3154. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginos MA, Page GP, Michalowicz BS, Patel KJ, Volker SE, Pambuccian SE, Ondrey FG, Adams GL, Gaffney PM. Identification of a gene expression signature associated with recurrent disease in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer Res. 2004;64(1):55–63. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toruner GA, Ulger C, Alkan M, Galante AT, Rinaggio J, Wilk R, Tian B, Soteropoulos P, Hameed MR, Schwalb MN. Association between gene expression profile and tumor invasion in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer genetics and cytogenetics. 2004;154(1):27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2004.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, Davis RE, Ma C, Lossos IS, Rosenwald A, Boldrick JC, Sabet H, Tran T, Yu X. Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene expression profiling. Nature. 2000;403(6769):503–511. doi: 10.1038/35000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenwald A, Wright G, Chan WC, Connors JM, Campo E, Fisher RI, Gascoyne RD, Muller-Hermelink HK, Smeland EB, Giltnane JM. The use of molecular profiling to predict survival after chemotherapy for diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(25):1937–1947. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Maitra A, Olsen M, Lowe AW, van Heek NT, Rosty C, Walter K, Sato N, Parker A, Ashfaq R. Exploration of global gene expression patterns in pancreatic adenocarcinoma using cDNA microarrays. Am J Pathol. 2003;162(4):1151–1162. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63911-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freije WA, Castro-Vargas FE, Fang Z, Horvath S, Cloughesy T, Liau LM, Mischel PS, Nelson SF. Gene expression profiling of gliomas strongly predicts survival. Cancer Res. 2004;64(18):6503–6510. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modlich O, Prisack HB, Pitschke G, Ramp U, Ackermann R, Bojar H, Vogeli TA, Grimm MO. Identifying superficial, muscle-invasive, and metastasizing transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: use of cDNA array analysis of gene expression profiles. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(10):3410–3421. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer P, Bonnefoi H, Becette V, Tubiana-Hulin M, Fumoleau P, Larsimont D, Macgrogan G, Bergh J, Cameron D, Goldstein D. Identification of molecular apocrine breast tumours by microarray analysis. Oncogene. 2005;24(29):4660–4671. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginestier C, Cervera N, Finetti P, Esteyries S, Esterni B, Adelaide J, Xerri L, Viens P, Jacquemier J, Charafe-Jauffret E. Prognosis and gene expression profiling of 20q13-amplified breast cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(15):4533–4544. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachtiary B, Boutros PC, Pintilie M, Shi W, Bastianutto C, Li JH, Schwock J, Zhang W, Penn LZ, Jurisica I. Gene expression profiling in cervical cancer: an exploration of intratumor heterogeneity. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(19):5632–5640. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Kaya G, Sauter G, McKee T, Donze O, Schwaller J, Huard B. The source of APRIL up-regulation in human solid tumor lesions. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80(4):697–704. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1105655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Allal A, Odunsi K, Andrews C, Herrmann FR, Huard B. Role of the tumour necrosis family ligand APRIL in solid tumour development: Retrospective studies in bladder, ovarian and head and neck carcinomas. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(15):2097–2100. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreaux J, Sprynski A-C, Mahtouk K, Moine P, Robert N, Rossi J-F, Klein B. Binding of TACI and APRIL to Syndecan-1 Confer on Them a Major Role in Multiple Myeloma. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2007;110(11):3522. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan F, Barlogie B, Arzoumanian V, Huang Y, Williams DR, Hollmig K, Pineda-Roman M, Tricot G, van Rhee F, Zangari M. Gene-expression signature of benign monoclonal gammopathy evident in multiple myeloma is linked to good prognosis. Blood. 2007;109(4):1692–1700. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-037077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Prasad M, Lemon WJ, Hampel H, Wright FA, Kornacker K, LiVolsi V, Frankel W, Kloos RT, Eng C. Gene expression in papillary thyroid carcinoma reveals highly consistent profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(26):15044–15049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251547398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dave SS, Fu K, Wright GW, Lam LT, Kluin P, Boerma EJ, Greiner TC, Weisenburger DD, Rosenwald A, Ott G. Molecular diagnosis of Burkitt's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(23):2431–2442. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta M, Ansell SM, Witzig TE, Ziesmer SC, Cerhan JR, Dillon SR, Novak AJ. APRIL-TACI Interactions Mediate Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma B Cell Proliferation through Akt Regulated Cyclin D1 and P21. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2007;110(11):3585. [Google Scholar]

- Deshayes F, Lapree G, Portier A, Richard Y, Pencalet P, Mahieu-Caputo D, Horellou P, Tsapis A. Abnormal production of the TNF-homologue APRIL increases the proliferation of human malignant glioblastoma cell lines via a specific receptor. Oncogene. 2004;23(17):3005–3012. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okano H, Shiraki K, Yamanaka Y, Inoue H, Kawakita T, Saitou Y, Yamaguchi Y, Enokimura N, Ito K, Yamamoto N. Functional expression of a proliferation-related ligand in hepatocellular carcinoma and its implications for neovascularization. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(30):4650–4654. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i30.4650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couchman JR. Syndecans: proteoglycan regulators of cell-surface microdomains? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4(12):926–937. doi: 10.1038/nrm1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filmus J. Glypicans in growth control and cancer. Glycobiology. 2001;11(3):19R–23R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/11.3.19R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahtouk K, Cremer FW, Reme T, Jourdan M, Baudard M, Moreaux J, Requirand G, Fiol G, De Vos J, Moos M. Heparan sulphate proteoglycans are essential for the myeloma cell growth activity of EGF-family ligands in multiple myeloma. Oncogene. 2006;25(54):7180–7191. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernfield M, Gotte M, Park PW, Reizes O, Fitzgerald ML, Lincecum J, Zako M. Functions of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:729–777. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasisekharan R, Shriver Z, Venkataraman G, Narayanasami U. Roles of heparan-sulphate glycosaminoglycans in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(7):521–528. doi: 10.1038/nrc842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timar J, Lapis K, Dudas J, Sebestyen A, Kopper L, Kovalszky I. Proteoglycans and tumor progression: Janus-faced molecules with contradictory functions in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2002;12(3):173–186. doi: 10.1016/S1044-579X(02)00021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander CM, Reichsman F, Hinkes MT, Lincecum J, Becker KA, Cumberledge S, Bernfield M. Syndecan-1 is required for Wnt-1-induced mammary tumorigenesis in mice. Nat Genet. 2000;25(3):329–332. doi: 10.1038/77108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klerk CP, Smorenburg SM, Otten HM, Lensing AW, Prins MH, Piovella F, Prandoni P, Bos MM, Richel DJ, van Tienhoven G. The effect of low molecular weight heparin on survival in patients with advanced malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(10):2130–2135. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Expression of BAFF, APRIL, TACI, BAFF-R and heparan sulfate proteoglycans in human tumor types to that of their normal tissue counterparts using publicly available gene expression data, including the Oncomine Cancer Microarray database.

Classification of cancers included in the analysis.

Gene expression profile of Syndecan 1–4 and glypican 1–6 was determined using Oncomine Cancer Microarray database in bladder carcinoma, esophagus adenocarcinoma, brain tumors, breast cancer, head and neck tumors, lymphoma, pancreatic adenocarcinoma and adult male germ cell tumors presenting an overexpression of APRIL or an association with a bad prognosis or tumor progression.