Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

The systemic and cognitive side effects of hepatitis C virus (HCV) therapy may be incapacitating, necessitating dose reductions or abandonment of therapy. Oral cannabinoid-containing medications (OCs) ameliorate chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, as well as AIDS wasting syndrome. The efficacy of OCs in managing HCV treatment-related side effects is unknown.

METHODS:

All patients who initiated interferon-ribavirin therapy at The Ottawa Hospital Viral Hepatitis Clinic (Ottawa, Ontario) between August 2003 and January 2007 were identified using a computerized clinical database. The baseline characteristics of OC recipients were compared with those of nonrecipients. The treatment-related side effect response to OC was assessed by χ2 analysis. The key therapeutic outcomes related to weight, interferon dose reduction and treatment outcomes were assessed by Student’s t test and χ2 analysis.

RESULTS:

Twenty-five of 191 patients (13%) initiated OC use. Recipients had similar characteristics to nonrecipients, aside from prior marijuana smoking history (24% versus 10%, respectively; P=0.04). The median time to OC initiation was seven weeks. The most common indications for initiation of OC were anorexia (72%) and nausea (32%). Sixty-four per cent of all patients who received OC experienced subjective improvement in symptoms. The median weight loss before OC initiation was 4.5 kg. A trend toward greater median weight loss was noted at week 4 in patients eventually initiating OC use (−1.4 kg), compared with those who did not (−1.0 kg). Weight loss stabilized one month after OC initiation (median 0.5 kg additional loss). Interferon dose reductions were rare and did not differ by OC use (8% of OC recipients versus 5% of nonrecipients). The proportions of patients completing a full course of HCV therapy and achieving a sustained virological response were greater in OC recipients.

CONCLUSIONS:

The present retrospective cohort analysis found that OC use is often effective in managing HCV treatment-related symptoms that contribute to weight loss, and may stabilize weight decline once initiated.

Keywords: Anorexia, HCV, Interferon, Oral cannabinoid, Weight loss

Abstract

OBJECTIFS :

Les effets secondaires systémiques et cognitifs du traitement de l’hépatite C (VHC) peuvent être invalidants et nécessiter des réductions de dose ou l’arrêt du traitement. Les médicaments oraux à base de cannabinoïdes (MOC) soulagent les nausées et les vomissements induits par la chimiothérapie et corrigent le syndrome d’émaciation lié au sida. L’efficacité des MOC dans la prise en charge des effets secondaires liés au traitement du VHC est inconnue.

MÉTHODES :

Tous les patients qui ont débuté un traitement par interféron-ribavirine à la clinique de traitement de l’hépatite virale de l’Hôpital d’Ottawa (Ottawa, Ontario) entre août 2003 et janvier 2007 ont été recensés à l’aide d’une base de données cliniques informatisée. Les caractéristiques de départ des receveurs de MOC ont été comparées à celles des non-receveurs. La réponse aux MOC sur le plan des effets secondaires liés au traitement contre l’hépatite a été évaluée au moyen du test du χ2. Les paramètres thérapeutiques clés avaient trait au poids, à la réduction de la dose d’interféron et à l’issue des traitements et ont été évalués au moyen des tests t de Student et du χ2.

RÉSULTATS :

Vingt-cinq patients sur 191 (13 %) ont commencé à prendre des MOC. Les receveurs présentaient les mêmes caractéristiques que les non-receveurs, outre des antécédents d’utilisation de marijuana (24 %, contre 10 %, respectivement, p = 0,04). La durée médiane avant le début des MOC était de sept semaines. Les indications les plus courantes pour l’instauration des MOC étaient l’anorexie (72 %) et les nausées (32 %). Soixante-quatre pour cent de tous les patients qui ont reçu des MOC ont connu une amélioration subjective de leurs symptômes. La perte de poids médiane avant l’instauration des MOC était de 4,5 kg. Une tendance à une perte de poids médiane plus accentuée a été notée à la semaine 4 chez les patients qui ont éventuellement commencé à prendre des MOC (− 1,4 kg), comparativement aux non-receveurs (− 1,0 kg). La perte de poids s’est stabilisée un mois après le début des MOC (perte de poids médiane additionnelle (0,5 kg). Les réductions des doses d’interféron ont été rares et n’ont pas différé selon l’utilisation ou non des MOC (8 % des receveurs, contre 5 % des non-receveurs). Les proportions de patients ayant complété leur cycle de traitement anti-VHC complet et ayant obtenu une réponse virologique soutenue ont été plus grandes chez les receveurs de MOC.

CONCLUSION :

La présente analyse de cohorte rétrospective a révélé que l’utilisation des MOC est souvent efficace pour la prise en charge des symptômes liés au traitement du VHC qui contribuent à la perte de poids et pourrait stabiliser la perte pondérale lorsqu’elle est débutée.

Despite the efficacy of hepatitis C virus (HCV) antiviral therapy (1–5), the physical and cognitive side effects of interferon-ribavirin-based regimens are numerous. Most patients experience persistent side effects including fatigue, headache, nausea, anorexia, depressive symptoms and insomnia (6–9). These symptoms can be incapacitating and may necessitate dose reduction or abandonment of therapy. This is not ideal, because suboptimal dosing of interferon-ribavirin results in diminished sustained virological response (SVR) rates (3). Adjunctive therapy such as antiemetics, anxiolytics and sleeping agents are frequently employed to assist patients with these side effects. Unfortunately, these adjunctive agents are often insufficient (7–9).

Although formal studies are lacking, there is anecdotal evidence that cannabis may be beneficial by alleviating common side effects associated with interferon-ribavirin, including anorexia, nausea, weight loss and insomnia (10–15). Despite the potential benefits of cannabis, concerns related to the long-term medical complications of inhaled cannabis use and the inability to legally obtain this product limit the use of it as a therapeutic intervention.

Oral cannabinoid-containing medications (OCs) have multiple potential therapeutic uses due to their analgesic, antiemetic, anticonvulsant, bronchodilatory and anti-inflammatory effects (16). They have been shown in clinical trials to ameliorate chemotherapy-induced nausea (17,18), to benefit those with AIDS wasting syndrome (19) and to reduce spasticity in multiple sclerosis patients (20).

We conducted a retrospective study to describe the use of OCs in an HCV-infected population receiving interferon-ribavirin therapy to quantify the potential efficacy of these agents in relieving anorexia, nausea, vomiting and insomnia. We also examined the effect of OCs on weight loss. We further compared interferon-ribavirin dose reduction, HCV treatment duration and SVR rates between patients receiving OC versus nonrecipients.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

All patients who initiated interferon-ribavirin therapy at The Ottawa Hospital Viral Hepatitis Clinic (Ottawa, Ontario) between August 2003 and January 2007 were identified using a computerized clinical database (SPSS 13.0, SPSS Inc, USA). This time frame was selected, because OCs were not routinely used in the clinic before August 2003. The present study’s work was conducted with Ottawa Hospital Research Ethics Board approval. Data from the most recent HCV therapy were used in those receiving more than one round of treatment. Baseline characteristics of all patients were compared between recipients of OCs (ie, Cesamet [Valeant Canada, Limited, Canada] and Marinol [Solvay Pharma Inc, Canada]) and nonrecipients.

A descriptive analysis of the HCV-infected population receiving interferon-ribavirin therapy, stratified by OC use, was compiled. Data capture was censored as of January 15, 2007. The proportion of OC recipients who achieved relief of anorexia, nausea, vomiting and insomnia was calculated. Trends in weight loss, HCV antiviral dose reduction, duration of HCV therapy, discontinuation rates and SVR were compared between OC recipients and nonrecipients by Student’s t test and χ2 analysis. Significance was defined as P<0.05.

RESULTS

Twenty-five of 191 patients (13%) initiated OC use (Cesamet, n=16; Marinol, n=9). This represented 866 person-weeks of interferon-ribavirin exposure in those who initiated OC use and 4323 person-weeks in those who did not. Baseline characteristics are described in Table 1. The characteristics of recipients were similar to those of nonrecipients, aside from prior marijuana smoking history (24% versus 10%, respectively; P=0.04). A higher proportion of patients with genotype 1 infection received OC. This was likely a consequence of receiving HCV therapy for 48 weeks, as opposed to 24 weeks for infection with genotypes 2 and 3.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment recipients, stratified by oral cannabinoid-containing medication (OC) use

| OC use

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=25) | No (n=166) | |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 44±7 | 43±10 |

| Weight, kg, mean ± SD | 78±19 | 79±17 |

| HCV RNA, copies/mL, mean ± SD | 1.1×106±1.7×106 | 1.2×106±1.9×106 |

| ALT level, U/L, mean ± SD | 73±52 | 101±78 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 18 (72) | 125 (75) |

| Female | 7 (28) | 41 (25) |

| HCV genotype, n (%) | ||

| 1 | 18 (73) | 102 (61) |

| 2 | 2 (8) | 20 (12) |

| 3 | 5 (20) | 39 (23) |

| 4 | 0 (0) | 5 (3) |

| Ethnic background, n (%) | ||

| White | 24 (96) | 148 (89) |

| Other | 1 (4) | 18 (11) |

| Country of birth, n (%) | ||

| Canadian-born | 22 (88) | 138 (83) |

| Immigrant | 3 (12) | 28 (17) |

| Liver biopsy stage (METAVIR), n (%)* | ||

| 0–2 | 10 (53) | 67 (68) |

| 3–4 | 9 (47) | 32 (32) |

| HIV coinfection, n (%) | 5 (20) | 14 (9) |

| Psychiatric illness history | 13 (52) | 86 (52) |

| Injection drug use history | 18 (72) | 98 (59) |

| Excess alcohol use history | 18 (72) | 100 (60) |

| Alcohol or drug abuse history | 22 (88) | 130 (78) |

| Marijuana smoking history | 6 (24) | 16 (10) |

Nineteen of 25 patients and 99 of 166 patients underwent pretreatment liver biopsy. ALT Alanine aminotransferase

Starting dates, initial doses and frequency of dosing of OCs were highly variable. The median time to OC initiation was week 7 (quartiles 2, 7, 18). Some patients used the medication routinely, while others used it on an as-needed basis. The most common indications for initiating OC use were anorexia (72%) and nausea (32%), with 67% and 75% of recipients, respectively, achieving subjective improvement in these symptoms. Insomnia was a rare indication for OC use (n=2) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Reasons for initiating oral cannabinoid-containing medication use and the corresponding outcomes

| Indication | n | Proportion of patients, % | Subjective improvement, as per patient report, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anorexia | 18 | 72 | 12 (67) |

| Nausea | 8 | 32 | 6 (75) |

| Vomiting | 3 | 12 | 2 (67) |

| Insomnia | 2 | 8 | 0 (0) |

| Composite indication* | 25 | – | 16 (64) |

Some patients had multiple indications for oral cannabinoid-containing medication use

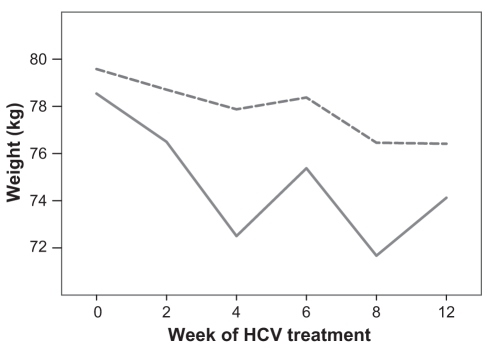

The median weight loss following the start of HCV therapy and before OC initiation was 4.5 kg. A trend toward greater median weight loss was noted at weeks 2 (−1.5 kg) and 4 (−1.4 kg) of HCV treatment in patients who initiated OC use, compared with those who did not use OC (−1.0 kg at each time point) (Note – this analysis excluded patients who began OC use in the initial four weeks of HCV therapy). Weight loss stabilized one month after the initiation of OC use (median 0.5 kg additional loss). Figure 1 illustrates trends in weight loss between those eventually starting OC use and nonrecipients.

Figure 1).

Comparison of weight loss during hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment between those eventually initiating oral cannabinoid-containing medication use (solid line) and nonrecipients (dashed line). This analysis excluded patients who began oral cannabinoid-containing medication use in the initial four weeks of HCV therapy

Interferon dose reductions were rare and did not differ by OC use (two of 25 OC recipients versus eight of 166 nonrecipients). This reflects a strict practice policy at The Ottawa Hospital Viral Hepatitis Clinic to avoid any interferon or ribavirin dose reduction, except as a last resort. A similar proportion of patients completed at least 12 weeks of HCV therapy, irrespective of OC use (Table 3). The proportion of patients completing a full course of HCV therapy (ie, 48 weeks for genotypes 1 and 4, and 24 weeks for genotypes 2 and 3) was 78% in OC recipients and 49% in those who did not initiate this class of medication (P=0.02). The proportion of patients achieving a SVR was greater in OC recipients (79%) than in nonrecipients (52%, P=0.07). A sensitivity analysis was conducted, which was restricted to patients who initiated OC use before week 12 (ie, those who failed to achieve an early virological response (EVR) would have interrupted HCV therapy and never had the opportunity to subsequently initiate OC use, thereby biasing the SVR results in favour of OC users). Seventeen of the 25 patients who initiated OC use did so before week 12. The EVR rate was 92% in OC recipients versus 78% in nonrecipients (P=0.22). The SVR rate was 67% in OC recipients versus 52% in nonrecipients (P=0.29). All results were similar when a sensitivity analysis was conducted that excluded marijuana-smoking patients (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of dose reductions, discontinuations and hepatitis C virus treatment outcomes between controls and oral cannabinoid-containing medication (OC) recipients

| No OC prescribed, % (n/total) | OC recipients, % (n/total) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients requiring interferon dose reductions | 5 (8/166) | 8 (2/25) | NS |

| Patients requiring ribavirin dose reductions | 10 (17/166) | 8 (2/25) | NS |

| At least 12 weeks of therapy completed* | 89 (118/132) | 94 (17/18) | NS |

| Full duration of therapy completed*† | 49 (65/132) | 78 (14/18) | P=0.02 |

| Sustained virological response achieved†‡ | 52 (53/101) | 79 (11/14) | P=0.07 |

Significance was defined as P<0.05.

Patients still on therapy at the time of data censorship were not included in this analysis (n=34 in the non-OC group and n=7 in OC recipients);

The full duration of therapy was 48 weeks for genotypes 1 and 4, and 24 weeks for genotypes 2 and 3;

Patients who did not yet reach the six months after completion of therapy point at the time of analysis have been excluded. NS Not significant

In general, OCs were well tolerated. Five recipients reported a minor side effect that was attributed to OC use. Side effects included sedation (n=1), dizziness (n=1), headache (a single episode) (n=1) and nonspecific malaise attributed to OC use (n=2). In three cases, OC use was discontinued because of side effects attributed to these medications. None of these side effects would be classified as severe adverse events. No case of abuse or addiction was identified.

DISCUSSION

Cannabinoids work via two known receptors – cannabinoid receptor (CB) 1 and CB2. Neurological and behavioural effects are mediated via CB1, which is expressed in peripheral neurons and the basal ganglia, cerebellum and hippocampus (21). This distribution of cannabinoid receptors also contributes to the observed benefit of OC use for chemotherapy-induced nausea (17,18) and AIDS-related weight loss (19).

In our clinical experience, OC use is often effective in managing HCV treatment-related symptoms that contribute to weight loss. It is our practice to avoid any HCV antiviral dose reduction unless absolutely necessary. The use of OC as an effective alternative therapy serves to preserve full therapeutic doses of HCV treatment. In the present study, precipitous weight loss in the first four weeks of HCV therapy was a marker of eventual OC prescription. We found that anorexia and nausea were managed effectively in most recipients of OC. We suspect that this, in turn, led to diminished additional weight loss following OC initiation.

Our findings are consistent with those of Sylvestre et al (22) in demonstrating that the amount of HCV drug exposure while on treatment and the duration of time that patients remain on therapy can be increased with the use of cannabinoids. These benefits likely contributed to the improved SVR rates observed in our population of patients. Our study does differ from that of Sylvestre et al in several key ways. While our patients used pharmaceutical grade OCs, the Sylvestre et al cohort smoked marijuana. Furthermore, the study by Sylvestre et al was confined to patients on methadone maintenance therapy.

The only pretreatment characteristic more frequently identified in those eventually receiving OC was a history of marijuana smoking. This is likely a marker of greater willingness to use cannabinoid-containing medication. We have found that patients are often hesitant to initiate these medications, given the stigmata attached to marijuana use and concerns related to addiction or criminal activity. An effort to educate patients about the potential benefits, low risks and negligible addiction risk of OCs may be an effective approach to mitigate these concerns. Additional concerns are that the provision of OCs may represent the exchange of one substance of abuse for another or that the prescription of OCs may enable substance abusing tendencies. In fact, there is little evidence to support abuse or diversion of OCs (23,24). Nonetheless, a personal observation in the clinic setting is that the occasional patient will seek OC prescriptions for the purpose of trafficking.

CB2 receptors are present on B lymphocytes and natural killer cells (25). Concerns related to potential immunosuppressive properties of cannabinoids have been raised (26–28). Because CB1 and CB2 receptors may be expressed on hepatic myofibroblasts, cannabinoids may also influence liver disease progression (27,29). In the present study, the use of OC was associated with minimal adverse events, which is consistent with other studies (30–32). Although our analysis raised no concerns related to the safety of OC use in combination with immunosuppressive HCV therapy or with regards to liver status, additional evaluations of the long-term immunological and hepatic effects of OCs are warranted.

There are limitations to consider when interpreting this work. Our study employed a retrospective cohort design and, as such, is subject to issues related to incomplete data for some parameters and to bias. Survival bias (ie, remaining on HCV treatment long enough to initiate OC use) must be considered when interpreting treatment outcomes. The proportion of patients completing a full course of HCV therapy and achieving a SVR was greater in OC recipients. However, patients without EVRs discontinued HCV therapy early, did not suffer further HCV treatment-related side effects and therefore did not start OC. We attempted to control for this by sensitivity testing, but recognize that further analyses are necessary before concluding that OC use improved SVR rates. Our sample size of OC recipients was relatively small. However, the effects between groups appear large and remain following sensitivity testing.

Despite these concerns, this evaluation of a well-described HCV treatment recipient cohort demonstrates the efficacy of OCs for the management of therapy-related anorexia, nausea and weight loss. As a consequence of better side effect management, patients may be better able to complete a full course of treatment and achieve higher SVR rates.

REFERENCES

- 1.Poynard T, Marcellin P, Lee SS, et al. Randomised trial of interferon alpha2b plus ribavirin for 48 weeks or for 24 weeks versus interferon alpha2b plus placebo for 48 weeks for treatment of chronic infection with hepatitis C virus. International Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group (IHIT) Lancet. 1998;352:1426–32. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)07124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Schiff ER, et al. Interferon alpha-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatitis Interventional Therapy Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1485–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811193392101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: A randomized trial. Lancet. 2001;358:958–65. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)06102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fried MW, Schiffman ML, Reddy KR, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:975–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sherman M, Bain V, Villeneuve JP, et al. The management of chronic viral hepatitis: A Canadian consensus conference 2004. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2004;15:313–26. doi: 10.1155/2004/326964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shiffman ML. Side effects of medical therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Ann Hepatol. 2004;3:5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gish RG. Maximizing the benefits of antiviral therapy for HCV: The advantages of treating side effects. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2004;33(1 Suppl):xxiii–xxxiv. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sylvestre DL, Loftis JM, Hauser P, et al. Co-occuring hepatitis C, substance use, and psychiatric illness: Ttreatment issues and developing integrated models of care. J Urban Health. 2004;81:719–34. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lauer GM, Walker BD. Hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:41–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107053450107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baker D, Pryce G, Giovannoni G, Thompson AJ. The therapeutic potential of cannabis. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:291–8. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00381-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sallan SE, Zinberg NE, Frei E., III Antiemetic effect of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 1975;293:795–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197510162931603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abrams DI. Potential interventions for HIV/AIDS wasting: An overview. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;25(Suppl 1):S74–80. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200010001-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walsh D, Nelson KA, Mahmoud FA. Established and potential therapeutic applications of cannabinoids in oncology. Support Care Cancer. 2003;11:137–43. doi: 10.1007/s00520-002-0387-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fabre LF, McLendon D. The efficacy and safety of nabilone (a synthetic cannabinoid) in the treatment of anxiety. J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;21(8–9 Suppl):377S–382S. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1981.tb02617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grinspoon L, Bakalar JB. The use of cannabis as a mood stabilizer in bipolar disorder: Anecdotal evidence and the need for clinical research. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1998;30:171–7. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1998.10399687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mechoulam R, Hanu L. The cannabinoids: An Overview. Therapeutic implications in vomiting and nausea after cancer chemotherapy, in appetite promotion, in multiple sclerosis and in neuroprotection. Pain Res Manag. 2001;6:67–73. doi: 10.1155/2001/183057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang AE, Shiling DJ, Stillman RC, et al. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol as an antiemetic in cancer patients receving high-dose methotrexate. A prospective, randomized evaluation. Ann Intern Med. 1979;91:819–24. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-91-6-819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frytak S, Moertel CG, O’Fallon JR, et al. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol as an antiemetic for patients receiving cancer chemotherapy. A comparison with prochlorperazine and a placebo. Ann Intern Med. 1979;91:825–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-91-6-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abrams DI. Potential interventions for HIV/AIDS wasting: An overview. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;25(Suppl 1):S74–80. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200010001-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zajicek J, Fox P, Sanders H, et al. for the UK MS Research Group Cannabinoids for treatment of spasticity and other symptoms related to multiple sclerosis (CAMS study): Multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;362:1517–26. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14738-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iversen L. Cannabis and the brain. Brain. 2003;126:1252–70. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sylvestre DL, Clements BJ, Malibu Y. Cannabis use improves retention and virological outcomes in patients treated for hepatitis C. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:1057–63. doi: 10.1097/01.meg.0000216934.22114.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calhoun SR, Galloway GP, Smith DE. Abuse potential of dronabinol (Marinol) J Psychoactive Drugs. 1998;30:187–96. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1998.10399689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beal JE, Olson R, Laubenstein L, et al. Dronabinol as a treatment for anorexia associated with weight loss in patients with AIDS. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1995;10:89–97. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(94)00117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Munro S, Thomas KL, Abu-Shaar M. Molecular characterization of a peripheral receptor for cannbinoids. Nature. 1993;365:61–5. doi: 10.1038/365061a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nahas GG, Suciu-Foca N, Armand JP, Morishima A. Inhibition of cellular mediated immunity in marihuana smokers. Science. 1974;183:419–20. doi: 10.1126/science.183.4123.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klein TW, Newton CA, Widen R, Friedman H. The effect of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and 11-hydroxy-delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol on T-lymphocyte and B-lymphocyte mitogen responses. J Immunopharmacol. 1985;7:451–66. doi: 10.3109/08923978509026487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gross G, Roussaki A, Ikenberg H, Drees N. Genital warts do not respond to systemic recombinant interferon alfa-2a treatment during cannabis consumption. Dermatologica. 1991;183:203–7. doi: 10.1159/000247670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hezode C, Roudot-Thoraval F, Nguyen S, et al. Daily cannabis smoking as a risk factor for progression of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C Hepatology 20054263–71.(Erratum in 2005;42:506). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gorter R, Seefried M, Volberding P. Dronabinol effects on weight in patients with HIV infection. AIDS. 1992;6:127. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199201000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plasse TF, Gorter RW, Krasnow SH, Lane M, Shepard KV, Wadleigh RG. Recent clinical experience with dronabinol. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1991;40:695–700. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90385-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beal JE, Olson R, Laubenstein L, et al. Dronabinol as a treatment for anorexia associated with weight loss in patients with AIDS. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1995;10:89–97. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(94)00117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]