Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a chronic inflammatory disease that is successfully treated with prednisone and/or azathioprine immunosuppressive therapy in 70% to 80% of patients. The remaining patients are intolerant or refractory to these standard medications. Budesonide, a synthetic glucocorticoid, undergoes a high degree of first-pass metabolism, reducing its systemic bioavailability, and has a 15-fold greater affinity for the glucocorticoid receptor than prednisolone. Budesonide may be a potentially useful systemic steroid-sparing immunosuppressive agent in the treatment of AIH.

OBJECTIVE:

To review the Canadian experience using budesonide to treat AIH.

METHODS:

Patients with AIH currently or previously treated with budesonide were identified through the Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver membership. Data were collected regarding their clinical and treatment history.

RESULTS:

A total of nine patients were identified. All patients were female, with an average age of 39 years (range 12 to 66 years). The indications for budesonide were adverse side effects of prednisone in two patients, noncompliance with prednisone and azathioprine in one patient and intolerance to azathioprine resulting in prednisone dependence in the remaining six patients. Patients were treated in doses ranging from 9 mg daily to 3 mg every other day for 24 weeks to eight years. Seven of nine patients had a complete response, defined as sustained normalization of the aminotransferase levels. The remaining two patients were classified as nonresponders (less than a 50% reduction in pretreatment aminotransferase levels).

CONCLUSIONS:

In Canada, budesonide has been successfully used in seven of nine patients with autoimmune hepatitis who were either intolerant to prednisone and azathioprine or prednisone-dependent. No adverse effects were reported with budesonide. Budesonide is potentially a valuable treatment option for AIH patients refractory or intolerant to standard therapy, and is deserving of further study.

Keywords: Autoimmune, Budesonide, Hepatitis

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

L’hépatite auto-immune (HAI) est une maladie inflammatoire chronique qui est traitée avec succès au moyen de prednisone et/ou d’azathioprine en traitement immunosuppresseur chez 70 % à 80 % des patients. Les autres ne tolèrent pas ces agents standard ou y sont réfractaires. Le budésonide, un glucocorticostéroïde synthétique, subit un important métabolisme de premier passage, ce qui réduit sa biodisponibilité systémique, et il a 15 fois plus d’affinité pour les récepteurs des glucocorticostéroïdes que la prednisone. Le budésonide peut être un immunosuppresseur d’épargne des corticostéroïdes systémiques potentiellement utile dans le traitement de l’HAI.

OBJECTIF :

Faire le point sur l’expérience canadienne en matière de traitement de l’HAI au moyen du budésonide.

MÉTHODES :

Les auteurs ont recensé les patients atteints d’HAI traités actuellement ou antérieurement au moyen de budésonide à partir de la liste des membres de l’Association canadienne pour l’étude du foie. Des données ont été recueillies au sujet de leurs antécédents cliniques et thérapeutiques.

RÉSULTATS :

En tout, neuf patients ont été identifiés. Il s’agissait de femmes dans tous les cas, et leur âge moyen était 39 ans (de 12 à 66 ans). Les indications du budésonide étaient : réactions indésirables à la prednisone chez deux patientes, piètre fidélité au traitement par prednisone et azathioprine chez une patiente et intolérance à l’azathioprine ayant entraîné une dépendance à la prednisone chez les six autres patientes. Les patientes ont reçu des doses allant de 9 mg par jour à 3 mg tous les deux jours pendant 24 semaines à huit ans. Sept patientes sur neuf ont manifesté une réponse complète, définie par une normalisation soutenue des taux d’aminotransférase. Les deux autres patientes ont été classées comme ne répondant pas au traitement (réduction de moins de 50 % des taux préthérapeutiques d’aminotransférase).

CONCLUSIONS :

Au Canada, le budésonide a été utilisé avec succès chez sept patientes sur neuf atteintes d’hépatite auto-immune qui ne toléraient ni la prednisone ni l’azathioprine ou qui étaient dépendantes de la prednisone. Aucun effet indésirable n’a été signalé avec le budésonide. Le budésonide est une option thérapeutique potentiellement utile chez les patients atteints d’HAI qui sont réfractaires au traitement standard ou ne le tolèrent pas. Le budésonide mérite d’être étudié plus en profondeur dans un tel contexte.

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a persistent inflammatory disorder of the liver of unknown etiology. It is characterized by antinuclear antibodies, anti-smooth muscle antibodies (type 1), liver-kidney microsomal antibodies (type 2) and soluble liver antigens (1,2). The annual incidence of type 1 AIH among Caucasian populations in Europe and North America ranges between 0.1 and 1.9 per 100,000 people (3). A study conducted in Norway in 1995 (4) revealed a point prevalence of 16.9 per 100,000. Diagnostic criteria for AIH, developed by the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group, include detection of autoantibodies, predominant serum aminotransferase abnormalities, hypergammaglobulinemia and interface hepatitis on histological evaluation, as well as the exclusion of other liver disease etiologies (5,6). Historically, as many as 40% of patients with untreated severe disease die within six months of diagnosis and at least 40% of those who survive eventually develop cirrhosis (7,8). AIH accounts for 5.9% of liver transplantations in the United States and 2.6% of those in Europe (9,10).

The current standard of care – corticosteroids with or without azathioprine – has proven to be effective in the induction of remission, with cirrhosis being potentially reversible in those achieving prolonged remission (7,11–13). Remission occurs when there is improvement in serum aminotransferase levels to less than twice the normal levels, normalization of serum bilirubin and gamma globulins, and improvement to normal or minimal inflammation without interface hepatitis (1). With conventional therapy, 65% of patients enter remission within 18 months and 80% achieve remission within three years. Relapse involves increased disease activity occurring after induction of remission and subsequent cessation of therapy. It develops in 20% of patients who revert to normal liver histology during initial treatment and 50% of those with portal hepatitis at termination of initial treatment, within six months (14,15). Treatment failure with clinical, laboratory and histological progression despite adherence to therapy occurs in up to 9% of patients (7,16).

Several studies investigating the withdrawal of therapy in patients who achieve remission have been conducted. Patients in whom azathioprine is withdrawn have a higher rate of relapse, even with continued corticosteroid therapy, than those maintained on combination therapy (17). It has been shown that azathioprine monotherapy is effective in maintaining remission once achieved using corticosteroids (18,19). One uncontrolled study (20) also demonstrated a direct correlation between duration of therapy before withdrawal and rates of sustained remission. In those treated for more than four years, 67% achieved sustained remission, compared with 17% of those treated for two to four years and 10% of those treated for one to two years. While standard treatments are effective in the induction and maintenance of remission, they are associated with significant and dangerous adverse effects. As a result, various other therapies have been investigated. The most extensively studied has been cyclosporine, which has shown promise, although widespread use of this agent is limited by its toxicity (21–26). Limited data also suggest that long-term use of ursodeoxycholic acid may have beneficial effects (27,28). Other investigators have studied the utility of mycophenolate mofetil (29–32), methotrexate (33,34), cyclophosphamide (35), 6-mercaptopurine (36), tacrolimus (37) and D-penicillamine (38), with some success. Budesonide is another immunosuppressive agent studied as a potential treatment for AIH. To date, budesonide as a treatment for AIH has been evaluated in only four studies, including one small clinical trial, with the number of patients reported in each study ranging from 10 to 18 (39–42). The reported experience with this drug is therefore limited. It was with this in mind that we report the Canadian experience of using budesonide to treat AIH.

METHODS

In 2006, the members of the Canadian Association for the Study of the Liver who were practising at the major Canadian university-based teaching hospitals were asked to review the charts of any of their patients who were treated with budesonide (Entocort, AstraZeneca Canada Inc, Canada) for AIH. Hepatologists at five centres who indicated that they had treated AIH patients with budesonide were sent a data collection form that was mailed or faxed back for compilation and analysis. Each hepatologist reviewed their own charts and provided a synopsis of their chart review, as well as a completed data collection form. Post-liver transplant recipients were excluded from the review. Data were collected retrospectively on patients from across Canada who were diagnosed and treated by different hepatologists, each of whom is respected within their own university centre. Each physician made their diagnosis based on the best clinical data available to them and began budesonide treatment on their own. Therefore, there was no standardization of the diagnosis or the treatment regimen. For the purposes of the present paper, a complete response (CR) was defined as a sustained normalization of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels for longer than three months. A partial response (PR) was defined as the reduction of AST and ALT levels by more than 50% and no response was defined as a reduction in AST and ALT levels by less than 50%. These definitions of CR and PR were similar to the transaminase criteria for remission and incomplete response published in the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease Practice Guidelines (1), but were more restrictive.

RESULTS

The present national chart review produced nine patients from five university-based hepatologists across Canada. All nine patients were female, with a mean age of 39 years (range 12 to 66 years), and all had previously been treated with conventional therapy. The indications for the use of a second-line agent such as budesonide varied among this cohort. One patient failed treatment with azathioprine after developing cushingoid features, which necessitated the cessation of prednisone. A second patient began therapy with prednisone and azathioprine, and subsequently stopped the drugs and refused to use them. A third patient did not wish to use azathioprine after she developed steroid-induced mania. The six remaining patients were prednisone-dependent before the initiation of budesonide due to adverse reactions to azathioprine (three with intractable nausea, one with severe leukopenia, one with Guillain-Barré syndrome and one with Stevens Johnson syndrome). All nine patients had an International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group score of 10 or higher, consistent with probable AIH (6). The dose of budesonide varied between 3 mg every other day to 9 mg daily, as determined by each patient’s hepatologist. The mean duration of budesonide therapy was 25 months and varied between six and 96 months (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics before budesonide therapy and the response to its use

| Age, years | Autoantibodies | Pretreatment liver biopsy, grade/stage | Prebudesonide prednisone dose, mg/day | Postbudesonide prednisone dose, mg/day | Response | Duration of therapy, months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | ASMA 1:1280 | 1/3 | 0 | 0 | CR | 15 |

| 42 | ASMA 1:40 | 2/1 | 15 | 0 | CR | 28 |

| 12 | ANA 1:160 | – | 0 | 0 | CR | 9 |

| 17 | ASMA 1:80 | 1/0 | 10 | 0 | CR | 96 |

| 66 | ANA 1:512 | – | 15 | 15 | NR | 6 |

| 49 | ASMA 1:80 | 2/1 | 0 | 0 | CR | 6 |

| 61 | ANA 1:80 | – | 10 | 10 | NR | 15 |

| 43 | ASMA 1:160 | 1/2 | 15 | 0 | CR | 30 |

| 34 | ANA 1:320 | – | 15 | 0 | CR | 24 |

ANA Antinuclear antibody titre; ASMA Anti-smooth muscle antibody titre; CR Complete response (sustained normalization of aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels); NR No response (Reduction of aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels of less than 50%)

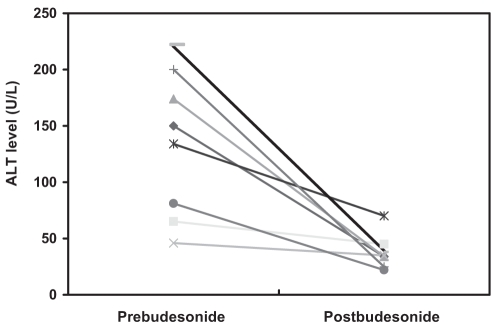

Using the definitions of CR, PR and no response described in the preceding section, it was found that seven of nine patients (78%) achieved a CR within six months of the introduction of budesonide and that this response was maintained throughout the duration of budesonide treatment. The remaining two patients did not respond to budesonide treatment. One nonresponder was maintained on prednisone 10 mg daily, and the second was maintained on prednisone 15 mg daily and cyclosporine 100 mg twice daily. The nonresponders were the two oldest patients in the cohort and perhaps suffered from more advanced disease. However, no histological or biochemical data are available to confirm this. Figure 1 displays the ALT levels before and after treatment with budesonide among eight of nine patients discussed in the present study. One patient could not be included, because they had been transferred to the care of a participating hepatologist after starting budesonide treatment. As a result, no prebudesonide clinical data were available for comparison.

Figure 1).

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) response in eight of nine patients with autoimmune hepatitis treated with budesonide. One patient could not be included, because they had been transferred to the care of a participating hepatologist after starting budesonide treatment

DISCUSSION

The majority of patients with AIH can be successfully managed with prednisone, azathioprine or a combination of both agents. However, patients who fail to respond or cannot tolerate conventional therapies are far more difficult to treat due to both the nature of the disease and to the limited therapeutic options available. Numerous agents have been studied as alternative treatments for AIH. Several case reports (21–26) have demonstrated that cyclosporine is effective in both treatment-naive and corticosteroid-refractory AIH. Sherman et al (22) reported a series of six patients with corticosteroid-resistant AIH in which 83% demonstrated normalization or near-normalization of ALT levels within 10 weeks of cyclosporine initiation. One open-label trial (24) of 19 patients demonstrated biochemical and histological improvement following 26 weeks of cyclosporine therapy in the 15 patients who completed the study. Widespread use of this agent is limited, however, by its potential for causing renal impairment, paresthesias, hypertension and hyperlipidemia, and predisposing patients to infections, particularly when long-term treatment is required. Two prospective clinical trials have studied the potential role of ursodeoxycholic acid in the management of AIH (27,28). One study (27) demonstrated biochemical and histological improvement after two years of treatment, while a subsequent trial (28) found no difference in improvement with the use of ursodeoxycholic acid or placebo in addition to corticosteroids. In several small studies (29–32), mycophenolate mofetil has been demonstrated to be useful in the treatment of AIH patients who are unable to tolerate standard therapies and in those whose disease is refractory to conventional treatment. Richardson et al (30) treated seven patients intolerant or resistant to azathioprine with mycophenolate (1 g twice per day) and demonstrated normalization of transaminases in 71% of patients after three months. Devlin et al (31) reported a series of five patients intolerant or resistant to conventional therapy who all demonstrated biochemical improvement after treatment with mycophenolate (0.5 g to 1 g twice per day). Chatur et al (32) described a series of 11 patients intolerant or resistant to conventional therapy, in which 64% demonstrated a complete biochemical response to mycophenolate monotherapy. Others have studied the use of methotrexate (33,34), cyclophosphamide (35), 6-mercaptopurine (36), tacrolimus (37) and D-penicillamine (38), with some success.

Budesonide is another corticosteroid immunosuppressive agent that may be useful in the treatment of AIH but, to date, it has not been very well studied. As with other corticosteroids, it binds to receptor elements in the promoter regions of several genes, thereby altering their transcription (43). This results in interference with cytokine production and inhibition of T lymphocyte activation. Budesonide is a second-generation corticosteroid with an affinity for the glucocorticoid receptor that is approximately 15 times greater than that of prednisolone. When taken orally, it has a 90% first-pass metabolism in the liver, allowing it to reach high intrahepatic concentrations before its elimination, significantly limiting its systemic effects. Budesonide has been evaluated in only four studies of AIH. In the first study (39), 12 previously untreated patients with AIH received budesonide 3 mg three times daily and after three months, 83% demonstrated a response, including complete remission in 58%. Csepregi et al (40) followed 18 patients (10 of whom were previously untreated) who received budesonide 3 mg three times daily for 24 weeks. In this group, 83% demonstrated complete clinical and biochemical remission. A third study (41) demonstrated a reduction in hepatic inflammation in 13 patients after six weeks of therapy with oral budesonide. Finally, a fourth study (42) of 10 treatment-dependent patients who received budesonide 3 mg three times daily found that only 30% entered clinical and biochemical remission. Intolerance to budesonide developed in 30% of patients, while 40% reportedly failed treatment. Cirrhosis was found at liver biopsy in 20% of patients before accession. In contrast, of five patients in our cohort who had a liver biopsy before budesonide therapy, only one had stage 3 fibrosis, while none had stage 4 fibrosis. Furthermore, the mean duration of therapy with budesonide in the present study was 25 months (range six to 96 months) compared with five months (range two to 12 months) in the study reported by Czaja et al (42). This last study, although of small patient numbers, concluded that budesonide had no clinical benefit. Our study, although limited by small patient numbers, like in the other four studies, is supportive of the first three ‘positive’ studies, because 78% achieved a complete treatment response to budesonide within six months in a clinical practice setting. Given the paucity of clinical studies using this drug for the treatment of AIH and given the unlikelihood of a definitive randomized clinical trial in the foreseeable future, our experience assumes importance despite the relatively small number of patients.

Despite the lack of clinical studies in the setting of AIH, clinical trials have demonstrated that budesonide is more effective than placebo and comparable to traditional corticosteroids in the treatment of Crohn’s disease (44,45). Budesonide has also demonstrated its use in the treatment of ulcerative colitis and collagenous colitis (46,47). As a result, it is being used more frequently in the treatment of these disorders as a means of sparing the use of conventional corticosteroids. There is, therefore, considerable clinical familiarity with this drug, which is commercially available. Off-label use for AIH, therefore, may be considered a feasible venture by clinicians and patients alike.

Future randomized controlled trials prospectively comparing budesonide with conventional therapy and/or novel immunosuppressive agents in the treatment of patients with AIH would help clarify its relative use as a first and second line treatment. The end points for such a study should include the proportion of patients who demonstrate a clinical, biochemical and histological remission after a predefined period of therapy. The proportion of patients who develop severe adverse reactions requiring cessation of therapy should also be assessed.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE: This work was presented at the 2007 Canadian Digestive Diseases Week in Banff, Alberta in February 2007 as a podium presentation. This work was unfunded and there were no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Czaja AJ, Freese DK, for the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease Diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2002;36:479–97. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.34944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strassburg CP, Manns MP. Autoantibodies and autoantigens in autoimmune hepatitis. Semin Liver Dis. 2002;22:339–52. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-35704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boberg KM. Prevalence and epidemiology of autoimmune hepatitis. Clin Liver Dis. 2002;6:635–47. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(02)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boberg KM, Aadland E, Jahnsen J, Raknerud N, Stiris M, Bell H. Incidence and prevalence of primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, and autoimmune hepatitis in a Norwegian population. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:99–103. doi: 10.1080/00365529850166284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson PJ, McFarlane IG, Alvarez F, et al. Meeting report: International autoimmune hepatitis group. Hepatology. 1993;18:998–1005. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840180435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alvarez F, Berg PA, Bianchi FB, et al. International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group report: Review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1999;31:929–38. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80297-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soloway RD, Summerskill WH, Baggenstoss AH, et al. Clinical, biochemical, and histological remission of severe chronic active liver disease: A controlled study of treatments and early prognosis. Gastroenterology. 1972;63:820–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mistilis SP, Skyring AP, Blackburn CR. Natural history of active chronic hepatitis. I. Clinical features, course, diagnostic criteria, morbidity, mortality, and survival. Australas Ann Med. 1968;17:214–23. doi: 10.1111/imj.1968.17.3.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiesner RH, Demetris AJ, Belle SH, et al. Acute hepatic allograft rejection: Incidence, risk factors, and impact on outcome. Hepatology. 1998;28:638–45. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milkiewicz P, Hubscher SG, Skiba G, Hathaway M, Elias E. Recurrence of autoimmune hepatitis after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1999;68:253–6. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199907270-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cook GC, Mulligan R, Sherlock S. Controlled prospective trial of corticosteroid therapy in active chronic hepatitis. Q J Med. 1971;40:159–85. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.qjmed.a067264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray-Lyon IM, Stern RB, Williams R. Controlled trial of prednisone and azathioprine in active chronic hepatitis. Lancet. 1973;1:735–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)92125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cotler SJ, Jakate S, Jensen DM. Resolution of cirrhosis in autoimmune hepatitis with corticosteroid therapy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;32:428–30. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200105000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Czaja AJ, Davis GL, Ludwig J, Taswell HF. Complete resolution of inflammatory activity following corticosteroid treatment of HBsAg-negative chronic active hepatitis. Hepatology. 1984;4:622–7. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840040409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Czaja AJ, Ludwig J, Baggenstoss AH, Wolf A. Corticosteroid-treated chronic active hepatitis in remission:. Uncertain prognosis of chronic persistent hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 1981;304:5–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198101013040102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schalm SW, Ammon HV, Summerskill WH. Failure of customary treatment in chronic active liver disease: Causes and management. Ann Clin Res. 1976;8:221–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stellon AJ, Hegarty JE, Portmann B, Williams R. Randomised controlled trial of azathioprine withdrawal in autoimmune chronic active hepatitis. Lancet. 1985;1:668–70. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)91329-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stellon AJ, Keating JJ, Johnson PJ, McFarlane IG, Williams R. Maintenance of remission in autoimmune chronic active hepatitis with azathioprine after corticosteroid withdrawal. Hepatology. 1988;8:781–4. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840080414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson PJ, McFarlane IG, Williams R. Azathioprine for long-term maintenance of remission in autoimmune hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:958–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199510123331502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanzler S, Gerken G, Lohr H, Galle PR, Meyer zum Buschenfelde KH, Lohse AW. Duration of immunosuppressive therapy in autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2001;34:354–5. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)00095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson LD, Song E. Cyclosporin in the treatment of corticosteroid resistant autoimmune chronic active hepatitis. Gut. 1995;36:459–61. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.3.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sherman KE, Narkewicz M, Pinto PC. Cyclosporine in the management of corticosteroid-resistant type 1 autoimmune chronic active hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1994;21:1040–7. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(05)80615-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernandes NF, Redeker AG, Vierling JM, Villamil FG, Fong TL. Cyclosporine therapy in patients with steroid resistant autoimmune hepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:241–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malekzadeh R, Nasseri-Moghaddam S, Kaviani MJ, Taheri H, Kamalian N, Sotoudeh M. Cyclosporin A is a promising alternative to corticosteroids in autoimmune hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:1321–7. doi: 10.1023/a:1010683817344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alvarez F, Ciocca M, Canero-Velasco C, et al. Short-term cyclosprorine induces a remission of autoimmune hepatitis in children. J Hepatol. 1999;30:222–7. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cuarterolo M, Ciocca M, Velasco CC, et al. Follow-up of children with autoimmune hepatitis treated with cyclosporine. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43:635–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000235975.75120.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakamura K, Yoneda M, Yokohama S, et al. Efficacy of ursodeoxycholic acid in Japanese patients with type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:490–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1998.tb00674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Czaja AJ, Carpenter HA, Lindor KD. Ursodeoxycholic acid as adjunctive therapy for problematic type 1 autoimmune hepatitis: A randomized placebo-controlled treatment trial. Hepatology. 1999;30:1381–6. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schuppan D, Herold C, Strobel D, Schneider HT, Hahn ET.Successful treatment of therapy-refractory autoimmune hepatitis with mycophenolate mofetil Hepatology 199828A1960(Abst) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richardson PD, James PD, Ryder SD. Mycophenolate mofetil for maintenance of remission in autoimmune hepatitis in patients resistant to or intolerant of azathioprine. J Hepatol. 2000;33:371–5. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80271-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Devlin SM, Swain MG, Urbanski SJ, Burak KW. Mycophenolate mofetil for the treatment of autoimmune hepatitis in patients refractory to standard therapy. Can J Gastroenterol. 2004;18:321–6. doi: 10.1155/2004/504591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chatur N, Ramji A, Bain VG, et al. Transplant immunosuppressive agents in non-transplant chronic autoimmune hepatitis: The Canadian Association for the Study of Liver (CASL) experience with mycophenolate mofetil and tacrolimus. Liver Int. 2005;25:723–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2005.01107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Venkataramani A, Jones MB, Sorrell MF. Methotrexate therapy for refractory chronic active autoimmune hepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3432–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.05346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burak KW, Urbanski SJ, Swain MG. Successful treatment of refractory type 1 autoimmune hepatitis with methotrexate. J Hepatol. 1998;29:990–3. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80128-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kanzler S, Gerken G, Dienes HP, Meyer zum Buschenfelde KH, Lohse AW. Cyclophosphamide as alternative immunosuppressive therapy for autoimmune hepatitis – report of three cases. Z Gastroenterol. 1997;35:571–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pratt DS, Flavin DP, Kaplan MM. The successful treatment of autoimmune hepatitis with 6-mercaptopurine after failure with azathioprine. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:271–4. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8536867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Thiel DH, Wright H, Carroll P, et al. Tacrolimus: A potential new treatment for autoimmune chronic active hepatitis: Results of an open-label preliminary trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:771–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McClements BM, Callender ME. D-penicillamine therapy in patients with HBsAg-negative chronic active hepatitis and major prednisilone-induced adverse effects. J Hepatol. 1990;11:322–5. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(90)90215-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wiegand J, Schuler A, Kanzler S, et al. Budesonide in previously untreated autoimmune hepatitis. Liver Int. 2005;25:927–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2005.01122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Csepregi A, Rocken C, Treiber G, Malfertheiner P. Budesonide induces complete remission in autoimmune hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1362–6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i9.1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Danielsson A, Prytz H. Oral budesonide for treatment of autoimmune chronic active hepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1994;8:585–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1994.tb00334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Czaja AJ, Lindor KD. Failure of budesonide in a pilot study of treatment-dependent autoimmune hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1312–6. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.0010000001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heneghan MA, McFarlane IG. Current and novel immunosuppressive therapy for autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2002;35:7–13. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.30991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greenberg GR, Feagan BG, Martin F, et al. Oral budesonide for active Crohn’s disease. Canadian Inflammatory Bowel Disease Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:836–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409293311303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rutgeerts P, Löfberg R, Malchow H, et al. A comparison of budesonide with prednisolone for active Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:842–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409293311304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keller R, Stoll R, Foerster EC, Gutsche N, Domschke W. Oral budesonide therapy for steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis: A pilot trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:1047–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miehlke S, Heymer P, Bethke B, et al. Budesonide treatment for collagenous colitis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:978–84. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.36042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]