Abstract

Cdr1p is the major ATP-binding cassette multidrug transporter conferring resistance to azoles and other antifungals in Candida albicans. In this study, the identification of new Cdr1p inhibitors by use of a newly developed high-throughput fluorescence-based assay is reported. The assay also allowed monitoring of the activity and inhibition of the related transporters Pdr5p and Snq2p of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which made it possible to compare its performance with those of previously established procedures. A high sensitivity, resulting from a wide dynamic range, was achieved upon high-level expression of the Cdr1p, Pdr5p, and Snq2p transporters in an S. cerevisiae strain in which the endogenous interfering activities were further reduced by genetic manipulation. An analysis of a set of therapeutically used and newly synthesized phenothiazine derivatives revealed different pharmacological profiles for Cdr1p, Pdr5p, and Snq2p. All transporters showed similar sensitivities to M961 inhibition. In contrast, Cdr1p was less sensitive to inhibition by fluphenazine, whereas phenothiazine selectively inhibited Snq2p. The inhibition potencies measured by the new assay reflected the ability of the compounds to potentiate the antifungal effect of ketoconazole (KTC), which was detoxified by the overproduced transporters. They also correlated with the 50% inhibitory concentration for inhibition of Pdr5p-mediated transport of rhodamine 6G in isolated plasma membranes. The most active derivative, M961, potentiated the activity of KTC against an azole-resistant CDR1-overexpressing C. albicans isolate.

Candida yeasts are the fourth most common pathogens responsible for systemic bloodstream infections. Candida albicans is the most frequently isolated species, contributing to >50% of cases (41). It generally shows little permeability to a large variety of toxic compounds, which is believed to result to a large degree from the existence of an active permeability barrier (42). Cdr1p and Cdr2p are two homologous ATP-binding cassette (ABC) multidrug resistance (MDR) transporters of broad specificity that confer resistance to the most widely used azole antifungals as well as to terbinafine, amorolfine, and many other metabolic inhibitors (43, 48). CDR1 is constitutively expressed in azole-sensitive isolates, where it modifies the intrinsic level of susceptibility to antifungals, as its inactivation by deletion increases sensitivity (47). The effectiveness of the small number of antifungals available for the treatment of life-threatening systemic mycoses is further reduced by overexpression of both CDR1 and CDR2 in many azole-resistant clinical isolates (46, 59).

Cdr1p and Cdr2p are structural and functional homologues of the Pdr5p and Snq2p MDR transporters of the model yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (25, 29, 50). A large-scale screening of Pdr5p substrate specificity identified it as the most important MDR ABC transporter, conferring resistance to most classes of currently available antifungals and other xenobiotics, with some overlap in specificity with Snq2p and Yor1p (25). Pdr5p, Snq2p, and Yor1p become highly overproduced in the plasma membrane as a result of gain-of-function point mutations in the homologous Zn2Cys6 transcriptional activators Pdr1p and Pdr3p, which can readily be selected on drug-containing media (1, 6, 7, 8, 22).

The development of efflux pump inhibitors for combination therapeutic approaches aimed at circumventing resistance is one strategy to increase the efficiency of currently available antifungals. Despite the identification of a few compounds reversing yeast azole resistance, including peptide derivatives and unnarmicins, by means of conventional, growth-based screening (39, 54), progress in the isolation and detailed quantitative characterization of new efflux pump inhibitors is limited by the lack of convenient and fast screening assays. In this study, taking advantage of high-level expression of Cdr1p and the closely related transporters Pdr5p and Snq2p in the model nonpathogenic yeast S. cerevisiae, we developed a new cell-based high-throughput assay for MDR transporter inhibition. The assay allowed the identification and characterization of new Cdr1p inhibitors and revealed differences in sensitivity of the three transporters that correlated with results obtained using previously established procedures based on cell growth and transport measurements in plasma membrane fractions (27). The effect of the most active inhibitor on the modulation of ketoconazole (KTC) resistance of a CDR1-overexpressing C. albicans isolate was also verified.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

The following reagents were purchased from the indicated suppliers: yeast extract, tryptone, peptone, and agar, Becton Dickinson; glucose and sodium chloride, Standard; rhodamine 6G, fluorescein diacetate (FDA), KTC, clotrimazole, cycloheximide, 4-nitroquinoline-N-oxide (4-NQO), and RPMI 1640, Sigma; and morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS), Amresco. The synthesis of the aminophenothiazine maleates M942, M959, M960, M961, M962, and M963 was carried out as described previously (35). Thioridazine and trifluoperazine were obtained from ICN. Amineptine, dextromepromazine, diethazine, levomepromazine, and thiethylperazine were kindly provided by J. Molnar. Other phenothiazine derivatives, including fluphenazine, were obtained from Sigma.

Plasmid construction.

The plasmid pKV2MK was constructed by homologous recombination of the SapI-XhoI fragment of pKV2 (22) with the PCR-amplified fragment of pRS316 (52), using the primers TCCATTATGTACTATTTAAAAAACACAAACTTTTGGATGTTCGGTTTATTGGTCCTTTTCATCACGTGCTATAA and AACGCGGCCTTTTTACGGTTCCTGGCCTTTTGCTGGCCTTTTGCTCACATGGGTAATAACTGATATAATTAAATTGAAGCTC.

The SacII-XbaI fragment of pDDB57 (60), containing the CaURA3 cassette, and the PmeI-BglII fragment of pFA6-3HA-His3MX6 (31), containing the HIS3MX6 cassette, were treated with the DNA polymerase I large (Klenow) fragment and inserted at several places into the PDR5 promoter fused with the β-galactosidase reporter in pKV2MK. The resulting constructs were verified for orientation and assayed for β-galactosidase activity after transformation into the hyperactivating PDR1-3 regulatory mutant strain, using ONPG (o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) as a substrate, as previously described (17). A construct with an insertion of CaURA3 that retained the full activity of the intact PDR5 promoter was selected for further modifications.

Next, an internal deletion was introduced by the ExSite procedure (Stratagene), using the primers GGACGGATCGCTTGCCTGTAAC and TGTGAGCAAAAGGCCAGCAAAAG, and the SmaI fragment was removed from the resulting clone to obtain pMK5.

The region encoding the C-terminal part of Pdr5p and the terminator region were PCR amplified in two steps, with concomitant insertion of a 10-histidine tag. In the first step, fragment 1 was generated with the primers ATTAAAGCTTGCTAGAATTCACACCACCAT and CCAAATTCAAAATTCTATTAGTGATGGTGATGGTGATGGTGATGGTGATGAGAACCTTTCTTGGAGAGTTTACCGTTCTTTTTAGGC. Fragment 2 was amplified with primers TAATAGAATTTTGAATTTGGTTAAGAAAAGAAAC and GTGATGAAAAGGACCTAACTATATCCATTGCGTC. After gel purification, fragments 1 and 2 were mixed and amplified in a second round with the flanking primers. The product was digested with HindIII and cloned into the HindIII and PmlI sites of pMK5 to generate pMK5h. The HindIII-PciI fragment of the pDR3.3 plasmid (29), encompassing the PDR5 open reading frame, was cloned into pMK5h, resulting in pMKPDR5h. pMKCDR1h and pMKSNQ2h (Fig. 1) were obtained by homologous recombination of PCR-amplified CDR1 and SNQ2 with linearized pMK5h. The resulting clones were verified by sequencing.

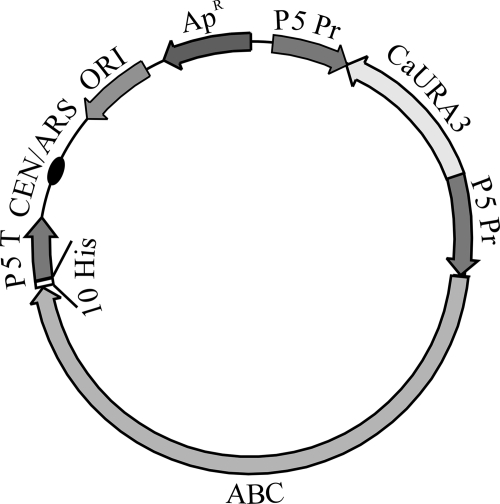

FIG. 1.

Scheme of final constructs pMKCDR1h, pMKPDR5h, and pMKSNQ2h, used for overexpression and integration of the polyhistidine-tagged ABC transporters CDR1, PDR5, and SNQ2 (ABC), respectively, under the control of the PDR5 promoter (P5 Pr). The positions of the origin of replication in Escherichia coli (ORI), the ampicillin resistance gene (ApR), the yeast centromere and autonomously replicating sequence (CEN/ARS), the C. albicans URA3 gene, the polyhistidine tag (10 His), and the PDR5 terminator (P5 T) are marked.

Strains and growth conditions.

The isogenic S. cerevisiae strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. To construct AK100, a deletion of PDR5 was generated with the URA3MX cassette, generated by the adaptamer-mediated PCR procedure (45). Briefly, fragments 1 and 2 were amplified by PCR on the PDR5 promoter and terminator regions, using the following primer pairs: for fragment 1, TTAACGTAAATATGTCTTCCTCTTTGATTCC and ACGACAACTTCAGCATCATGGCATGAGGAACGTTCATGTTCTTTTATTAG; and for fragment 2, GTGTTTAGGTCGATGCCATCTTTGTACTAGAATTTTGAATTTGGTTAAGAAAAG and TAACTATATCCATTGCGTCCTTTCTT. Fragments 3 and 4 were amplified from the pAG61 plasmid (16) by using the following primer pairs: for fragment 3, TGCCATGATGCTGAAGTTGTCGT and CCCTCTTGGCTCTTGGTTGGT; and for fragment 4, GCCTCACCAGTAGCACAACGATTATTT and GTACAAAGATGGCATCGACCTAAACAC. The PCR products were gel purified, and two additional PCRs were performed with the flanking primers, using combined fragments 1 and 3 as well as fragments 2 and 4 as templates. The two overlapping generated PCR products, 1+3 and 2+4, were cotransformed into the FYAK 26/8-4D2 strain by the lithium acetate procedure (15). The correct integration was verified by replica plating on medium containing cycloheximide and by colony PCR. The URA3 gene was removed by 5-fluoroorotic acid treatment of the appropriate transformants (2).

TABLE 1.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| FY1679-28C | MATaura3-52 trp1Δ63 leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 GAL2+ | C. Fairhead |

| FYMK-1/1 | MATaura3-52 trp1Δ63 leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 GAL2+ pdr5-Δ1::hisG | 25 |

| FYMK 23/2 | MATaura3-52 trp1Δ63 leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 GAL2+ snq2-Δ1::hisG | 25 |

| FYMK 26/8-10B | MATaura3-52 trp1Δ63 leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 GAL2+ pdr5-Δ1::hisG snq2-Δ1::hisG | 25 |

| FYMK 26/8-5C | MATaura3-52 trp1Δ63 leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 GAL2+ PDR1-3 | 25 |

| FYAK 26/8-4D2 | MATaura3-52 trp1Δ63 leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 GAL2+ PDR1-3 snq2-Δ1::hisG yor1-1::hisG | A. Kolaczkowska |

| FYAK 26/8-5A2 | MATaura3-52 trp1Δ63 leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 GAL2+ PDR1-3 pdr5-Δ1::hisG yor1-1::hisG | A. Kolaczkowska |

| AK100 | MATaura3-52 trp1Δ63 leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 GAL2+ PDR1-3 pdr5-Δ4::rep500 snq2-Δ1::hisG yor1-1::hisG | This study |

| MKCDR1h | MATaura3-52 trp1Δ63 leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 GAL2+ PDR1-3 pdr5-Δ4::CDR1h snq2-Δ1::hisG yor1-1::hisG | This study |

| MKPDR5h | MATaura3-52 trp1Δ63 leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 GAL2+ PDR1-3 pdr5-Δ4::PDR5h snq2-Δ1::hisG yor1-1::hisG | This study |

| MKSNQ2h | MATaura3-52 trp1Δ63 leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 GAL2+ PDR1-3 pdr5-Δ4::SNQ2h snq2-Δ1::hisG yor1-1::hisG | This study |

| MKSNQ2 | MATaura3-52 trp1Δ63 leu2Δ1 his3Δ200 GAL2+ PDR1-3 snq2::pdr5prom pdr5-Δ1::hisG yor1-1::hisG | This study |

MKCDR1h, MKPDR5h, and MKSNQ2h were obtained by integration of the gel-purified fragments of pMKCDR1h, pMKPDR5h, and pMKSNQ2h, respectively, into AK100 by homologous recombination and selection for uracil prototrophy. The resulting clones were verified by replica plating on medium containing cycloheximide, clotrimazole, and 4-NQO and by colony PCR.

To construct MKSNQ2, the PDR5 promoter region of pMKPDR5h was amplified with the primers ATTACATTCTCAGTGCATCCATCGTCTTCAACATTGATTACCACCTTTGATTGTAAATAGTAATAATTACCACCC and CATTATGAGAGCTATCTTGCGTGCTTTTGATATTGCTCATTTTTGTCTAAAGTCTTTCGAACGAGCGGATACG and integrated into the genome of FYAK 26/8-5A2, replacing the SNQ2 promoter. The resulting clones were selected for uracil prototrophy and verified by replica plating on medium containing 4-NQO and by colony PCR. Similar drug resistance phenotypes were observed for FYAK 26/8-4D2 and MKPDR5h and for MKSNQ2 and MKSNQ2h, indicating that the presence of the 10-His epitope at the C terminus did not affect the function of the tagged proteins. This is in agreement with other studies in which C-terminal fusion with the even larger protein green fluorescent protein did not compromise the function of the MDR transporters Pdr5p (53; our unpublished observations) and Cdr1p (51). C. albicans isolate 15 (59) was kindly provided by Theodore White.

The MICs for Candida were determined by a microdilution assay in MOPS-buffered RPMI 1640 medium as previously described, using the CLSI M27-A broth microdilution method (38). MICs for S. cerevisiae were determined by a microdilution assay essentially as previously described (26). Growth was monitored by measuring the optical density at 550 (OD550) and OD600 in a microplate reader as well as by visual inspection after 24 and 48 h. Compounds were added as dimethyl sulfoxide stock solutions, and an identical solvent amount was added to the control cultures, where it did not affect growth at the applied concentrations, not exceeding 1.2%. The MICs represent the values observed in three independent measurements in which the error did not exceed the window determined by the serial dilution factor. For the MIC breakpoint, the lowest concentration of compound that inhibited the growth yield by at least 80% compared to the drug-free control was used.

The effect of the combination of M961 or fluphenazine with KTC was determined by a microdilution checkerboard procedure (11). The FICindex was defined following the equation FICindex = FICA + FICB = (MICA comb/MICA alone) + (MICB comb/MICB alone), where MICA alone and MICB alone are the MICs of drugs acting alone and MICA comb and MICB comb are MICs of drugs A and B in combination. Drug interactions were defined as synergistic if the FICindex was ≤0.5, indifferent if the FICindex was >0.5 and ≤4.0, and antagonistic if the FICindex was >4 (40, 58).

Plasma membrane isolation.

Isolation of plasma membranes was performed according to the glass bead lysis procedure (10), with minor modifications as described previously (27). Membranes were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in a Laemmli system (28) and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 (Bio-Rad).

Immunological methods.

Protein extracts were prepared by glass bead lysis as previously described (21). Protein concentrations were determined by use of a Bio-Rad protein assay kit as recommended by the supplier. Equal amounts of protein were resuspended in SDS loading buffer prior to analysis by Western blotting (56). Blots were incubated with India HisProbe-HRP (Pierce) and anti-Vph1p antibody (Molecular Probes) and developed with SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce).

Fluorescence intensity measurements and calculations of results.

Exponentially growing cultures were collected and washed with water. Serial dilutions of the compounds to be tested were prepared in 96-well microtiter plates in 50 mM glucose-containing MOPS, pH 7. Next, the cell suspension was added, and the plates were preincubated for 5 min at room temperature. The reaction was started by the addition of FDA. Fluorescence intensity was recorded with Molecular Devices Gemini EM and XS microplate spectrofluorometers at 485-nm excitation and 538-nm emission wavelengths. The reaction rates, corresponding to the slopes of the linear fluorescence intensity traces recorded in real time, were calculated by the SoftmaxPro program, using linear fitting. To quantify the effects of different inhibitors, the reaction rates were plotted against the concentrations of each compound to generate dose-response curves. To avoid the influence of nonspecific effects which might result from the toxicity of the compounds at high concentrations, a new parameter, the concentration of inhibitor resulting in a threefold increase in the reaction rate over the background in the presence of solvent alone (IC3b), was calculated, after fitting of the curves to a polynomial, and used as a measure of inhibitor potency.

Measurements of inhibition of Pdr5p-mediated rhodamine 6G transport in isolated plasma membranes were performed with a Molecular Devices Gemini XS microplate spectrofluorometer, essentially as previously described (27), after adaptation to the 96-well microplate format. Briefly, serial dilutions of inhibitors in assay buffer were prepared in a 96-well microplate. Isolated plasma membranes and rhodamine 6G were then added. The reaction was started by the addition of Mg-ATP after 5 min of preincubation, and the fluorescence intensity was recorded in real time. The rates of rhodamine 6G fluorescence intensity decrease, corresponding to the slopes of the recorded traces in the linear region, were calculated using the SoftMax Pro program. The 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) were calculated after fitting of the data with a four-parameter logistic equation.

RESULTS

Identification of a substrate suitable for high-throughput measurement of MDR transporter efflux activity in S. cerevisiae.

To identify substrates suitable for homogenous, real-time monitoring of the transport activity of MDR transporters in S. cerevisiae, we searched for compounds which change their fluorescence intensity upon accumulation in cells. We focused on a group of profluorochromes which become brightly fluorescent upon cleavage of the acetate or acetoxymethyl group by nonspecific intracellular esterases and produce a different signal in S. cerevisiae strains with disruptions in the major MDR transporter genes PDR5 and/or SNQ2 compared with the wild-type reference signal.

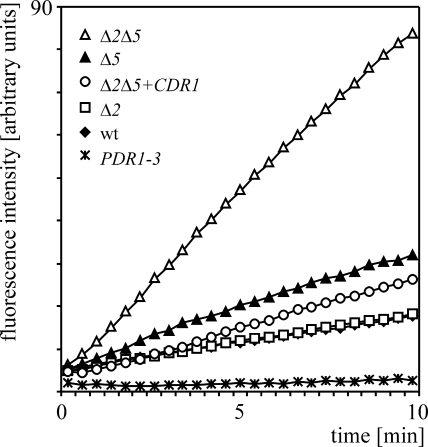

Figure 2 reveals that the addition of FDA to the cell suspension of the wild-type FY1679-28C strain produced a slow linear increase in fluorescence intensity, which increased in the case of the otherwise isogenic PDR5 disruptant (Table 1). A much higher rate of fluorescence intensity increase was observed with the double PDR5 SNQ2 knockout, which indicated that both transporters modify the accumulation of FDA in cells. This effect was complemented by transformation of the plasmid-borne PDR5 and/or SNQ2 gene (data not shown). Introduction of the plasmid carrying the CDR1 gene into the double PDR5 SNQ2 knockout also caused a significant decrease in FDA accumulation (Fig. 2). Since much higher rates of FDA hydrolysis and fluorescence signal generation, which were similar for all analyzed strains, were observed in glass bead-lysed cell suspensions (data not shown), this suggested that membrane penetration rather than intracellular FDA hydrolysis was the rate-limiting step. The deletion of SNQ2 in the PDR5 knockout, as expected, caused a larger increase in FDA accumulation than did deletion in the wild-type strain background. This was related to the much higher expression level of PDR5, which masks the SNQ2-related phenotypes (24, 32). The magnitude was further increased in the absence of PDR5 due to the elevated expression of SNQ2 by the compensatory transcriptional mechanism (24). The signal generated in the gain-of-function mutant of the transcriptional regulator gene PDR1-3, which contains elevated levels of Pdr5p and Snq2p in the plasma membrane due to hyperactivation of the corresponding PDR5 and SNQ2 promoters (6, 7), was, as expected, lower than that in the wild type and similar to that in the cell-free control (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Effects of Pdr5p, Snq2p, and Cdr1p on FDA accumulation in S. cerevisiae. Equal amounts of cells expressing different levels of the analyzed transporters were put into microplate wells, and the reaction, started by the addition of FDA, was monitored in a fluorescence reader in real time as described in Materials and Methods. The fluorescence intensity increase is proportional to the rate of intracellular accumulation. Disruptions in PDR5 and SNQ2 are indicated as Δ5 and Δ2, respectively. The presence of a plasmid-carried CDR1 gene is marked (+CDR1). The wild-type reference strain (wt) and the MDR regulatory PDR1-3 mutant are indicated. The traces for the wild type and the SNQ2 disruptant overlap.

Overproduction, normalization of transporter expression, and effect on FDA accumulation.

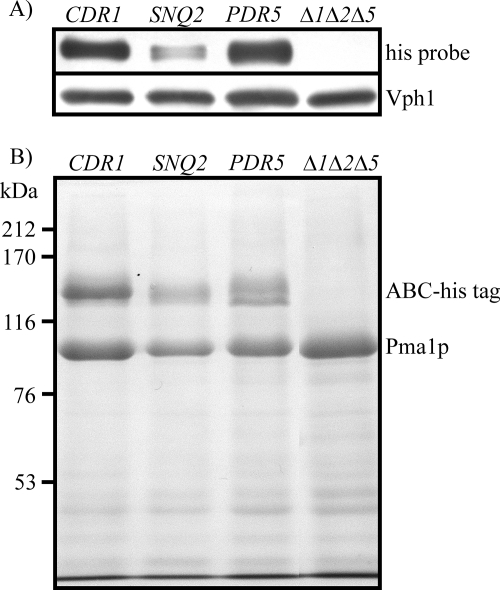

Cdr1p as well as Pdr5p and Snq2p was overproduced in order to reduce the possible contributions of other endogenous transporters and to achieve a high dynamic response of measurements required for inhibitor analysis. Since high-level overproduction of membrane proteins is often difficult to achieve due to toxicity and mislocalization issues, we used the PDR5 promoter and the regulatory PDR1-3 mutant, in which high levels of endogenous Pdr5p are properly targeted to the plasma membrane, leading to high-level MDR (7). Western blot analysis revealed that each of the C-terminally polyhistidine-tagged proteins was expressed in the host devoid of endogenous copies of PDR5, SNQ2, and YOR1 (Fig. 3A). SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis confirmed the high levels of overproduction of polyhistidine-tagged Pdr5p, Snq2p, and Cdr1p in the plasma membranes, comparable to that of the marker enzyme Pma1p (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Analysis of expression level and localization of overproduced polyhistidine-tagged transporters. (A) Western blot of cell extracts with the polyhistidine epitope-specific India HisProbe-HRP and with anti-Vph1p antibody as the loading control. (B) Coomassie-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel showing plasma membrane fractions isolated from strains overproducing Cdr1p, Snq2p, and Pdr5p. The expression host, in which endogenous copies of YOR1, SNQ2, and PDR5 were disrupted (Δ1Δ2Δ5), served as a negative control. The positions of molecular size markers, histidine-tagged ABC transporters (ABC-His tag), and the plasma membrane marker enzyme proton ATPase Pma1p are indicated.

The drastic reduction in the rate of intracellular FDA accumulation upon overproduction of the analyzed transporters reached 50-fold, depending on the protein. It decreased from 8,123 (average value from 30 independent measurements; standard deviation [SD] = 487) in the expression host to 128 (SD = 10), 176 (SD = 14), and 159 (SD = 11) in the Cdr1p-, Pdr5p-, and Snq2p-overproducing strains, respectively. Thus, the similar levels of the analyzed transporters found in the plasma membranes were reflected by similar levels of FDA extrusion activity. The calculation of the Z′ factor, which was equal to 0.8, indicated the high quality of the assay and its suitability for high-throughput screening (HTS) (62).

Evaluation of assay performance and identification of new Cdr1p inhibitors showing different effects on Pdr5p and Snq2p.

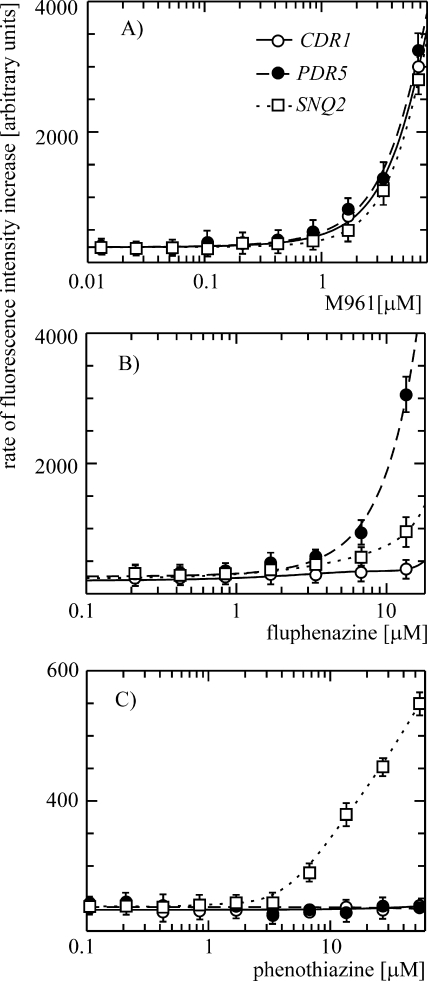

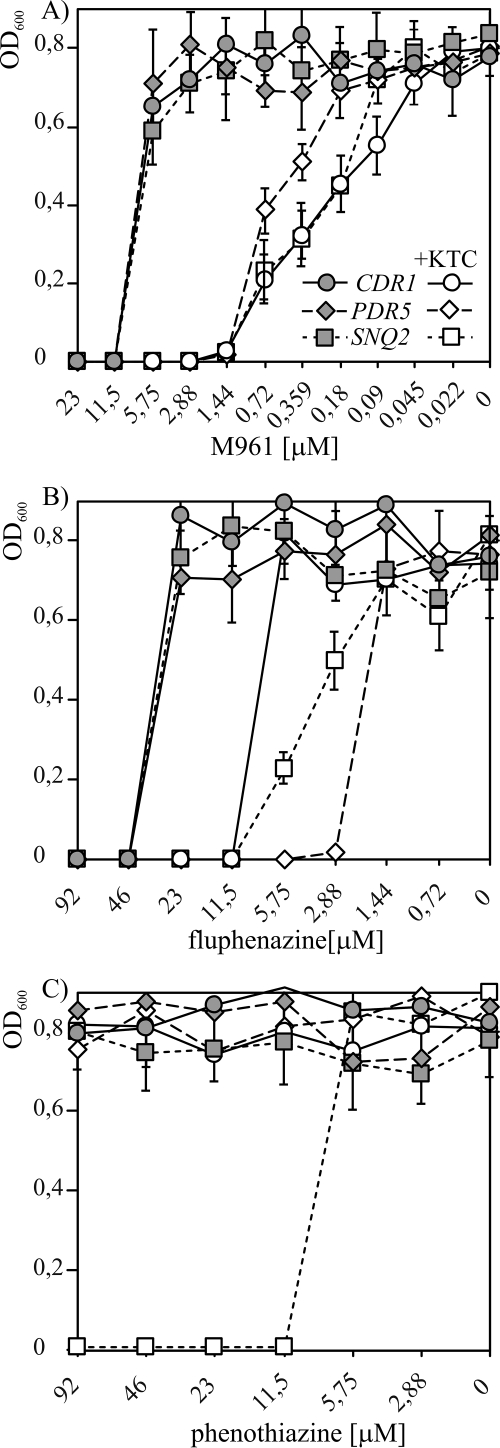

To evaluate the performance of the new assay further and to identify new Cdr1p inhibitors, a series of closely related, therapeutically used, and newly synthesized phenothiazine derivatives was analyzed. The assay was performed in the presence of serial dilutions of test compounds and with S. cerevisiae strains MKCDR1h, MKPDR5h, and MKSNQ2h, selectively overproducing Cdr1p, Pdr5p, and Snq2p, respectively. It revealed gradual increases in the rate of intracellular FDA accumulation and the generation of the fluorescence signal above a certain concentration threshold (Fig. 4), which were not observed upon addition of the solvent alone. In contrast to many enzymatic in vitro assays in which the saturation of the response is observed at higher inhibitor concentrations, a sudden drop in the rate of fluorescence intensity increase was often observed (data not shown). This phenomenon, which was related to the toxicity of the compounds at higher concentrations, did not allow for calculation of the IC50. As evident from Fig. 4, however, large differences in the potencies of the inhibitors were observed in the initial regions of the dose-response curves. A new inhibitor of Cdr1p, M961, was active in the low micromolar range (Fig. 4). Three types of response were generally observed. M961, which was the most potent compound, turned out to be equally active against Cdr1p, Pdr5p, and Snq2p (Fig. 4A). In contrast, the three transporters differed in their responses to fluphenazine, which was most effective against Pdr5p. Cdr1p was the least sensitive to fluphenazine inhibition, whereas Snq2p showed an intermediate sensitivity (Fig. 4B). Snq2p, however, was specifically inhibited by phenothiazine, which was inactive against Cdr1p and Pdr5p (Fig. 4C). Since the decrease in the rate of the reaction was negligible at M961 concentrations below 0.01 μM, as well as at fluphenazine and phenothiazine concentrations below 0.1 μM, the corresponding data points were omitted from Fig. 4 for clarity.

FIG. 4.

Differential responses of Cdr1p, Pdr5p, and Snq2p to inhibition by phenothiazines in the newly developed fluorescence-based assay. Suspensions of S. cerevisiae cells specifically overproducing each of the three ABC MDR transporters (M961 [A], fluphenazine [B], and phenothiazine [C]) were added to serial dilutions of the compounds. The reaction was started by the addition of FDA, and its conversion to the free fluorescent form upon intracellular accumulation was measured in real time in a fluorescence microplate spectrophotometer as described in Materials and Methods.

To enable quantitative comparison of the inhibitors, we searched for parameters related to the initial regions of the dose-response curves. IC3b, which is the concentration resulting in a threefold increase in the rate of fluorescence signal increase over the corresponding background in the absence of the inhibitor, was the most reproducible one. The standard deviation of IC3b for five independent measurements was typically less than 10% of the measured value. It also showed the highest correlation with the results of the inhibitor potency measurements of other established assays. The mean values of IC3b calculated for the tested series of compounds are summarized in Table 2, together with their structures.

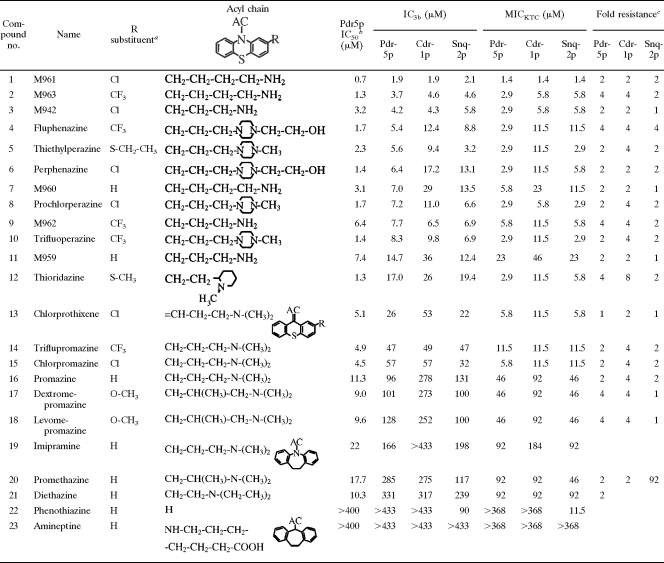

TABLE 2.

Parameters of in vitro and in vivo inhibition of the multidrug transporters Pdr5p, Cdr1p, and Snq2p by phenothiazines and related compounds

Substituent at position 2 of the ring backbone.

IC50 for rhodamine 6G transport in isolated plasma membranes.

Ratio of the MIC of the strain overproducing the indicated transporter to the MIC of the isogenic expression host.

Comparison of the new assay with other methods.

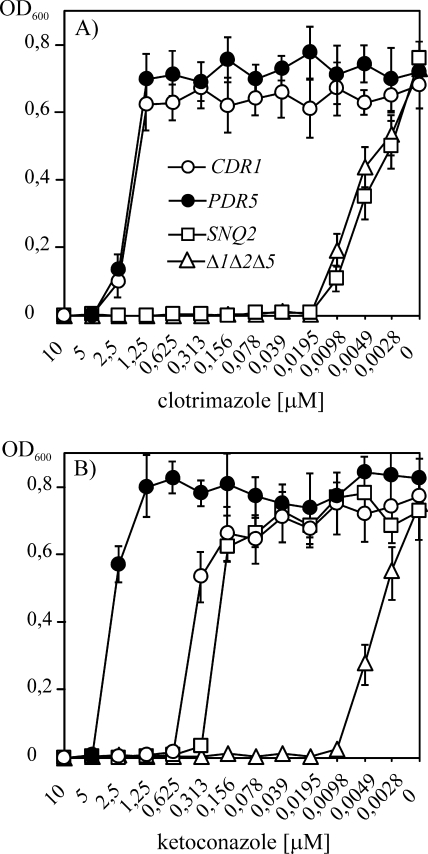

The most common procedure for the initial evaluation of potential efflux pump inhibitors is measuring the ability of test compounds to potentiate the growth inhibitory effect of a toxic drug substrate of an MDR transporter. To verify whether the results of the new fluorescence-based assay correlate with those of a traditional growth-based method, we searched for an antifungal drug substrate detoxified by the three analyzed transporters. There was a vast array of choices for both Pdr5p and Cdr1p, which decrease the intracellular concentrations of several azoles. Snq2p, however, has a more distinct specificity from those of Pdr5p and Cdr1p, with only some degree of overlap (25, 32). Figure 5A demonstrates that whereas the overproduction of Pdr5p and Cdr1p conferred similar levels of clotrimazole resistance, Snq2 did not detoxify this compound. This was also the case for several other azoles tested, indicating a much more limited specificity of this protein toward this class of drugs. In contrast, KTC was detoxified by all three proteins (Fig. 5B) (with MICs of 5 μM for Pdr5p, 0.6 μM for Cdr1p, and 0.3 μM for Snq2p overproducers, compared to the MIC of the expression host of 0.01 μM). We then measured MICs obtained in the presence of a subinhibitory concentration of KTC (MICKTC), which was adjusted individually for each transporter-overproducing strain proportionally to the estimated MIC of this antifungal alone (2.5-fold below the MIC). The three types of responses observed in the growth assay shown in Fig. 6 for M961, fluphenazine, and phenothiazine reflected the relationships identified by the new fluorescence-based test (Fig. 4; Table 2).

FIG. 5.

Similarities and differences in azole resistance profiles for Cdr1p, Pdr5p, and Snq2p. Equal amounts of S. cerevisiae cells specifically overproducing each of the three ABC MDR transporters (designated in the legend in panel A) were inoculated into microplate wells containing serial twofold dilutions of clotrimazole (A) or KTC (B). Growth was monitored by OD600 measurements on a microplate reader, as described in Materials and Methods.

FIG. 6.

Effects of identified inhibitors of FDA transport by Cdr1p, Pdr5p, and Snq2p on the reversal of KTC resistance mediated by these three transporters. Equal amounts of S. cerevisiae cells specifically overproducing each of the three ABC MDR transporters (designated in the legend in panel A) were inoculated into microplate wells containing serial twofold dilutions of the specified inhibitors (M961 [A], fluphenazine [B], and phenothiazine [C]) applied alone (shaded symbols) or combined with a subinhibitory KTC concentration (+KTC) (open symbols), adjusted for each strain to be 2.5-fold below the MIC. Growth was monitored by OD600 measurements on a microplate reader, as described in Materials and Methods.

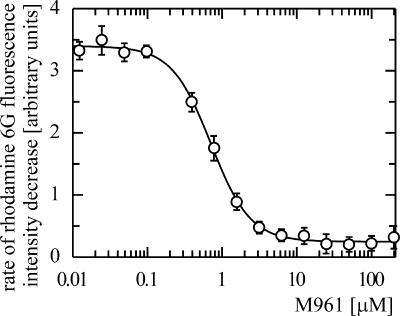

Since the results of cell-based procedures can be affected by modification of additional cellular metabolic pathways in addition to MDR transport inhibition, we used a previously developed in vitro assay (27) to determine the IC50s for phenothiazine inhibition of Pdr5p-mediated rhodamine 6G transport in isolated plasma membranes. Figure 7 shows a typical dose-response curve for the most potent inhibitor, M961, which was active in the nanomolar range. IC50s for other compounds are summarized in Table 2.

FIG. 7.

Dose-response curve for M961 inhibition of Pdr5p-mediated rhodamine 6G transport in isolated plasma membranes. Serial dilutions of M961 in assay buffer in a 96-well microplate were prepared. Isolated plasma membranes and rhodamine 6G were then added. The reaction was started by Mg-ATP addition, and the fluorescence intensity was recorded in real time as described in Materials and Methods. The rate of rhodamine 6G fluorescence intensity decrease was plotted versus M961 concentration. The IC50 of 0.7 μM was calculated after fitting of the data with a four-parameter logistic equation.

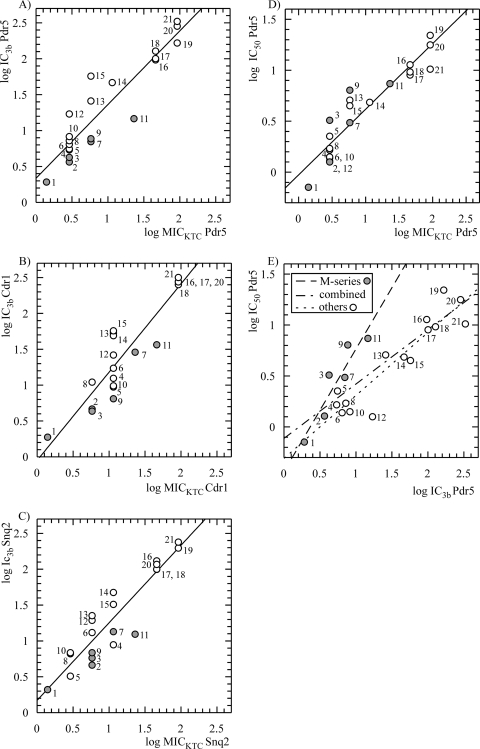

The high levels of correlation of the IC3b with MICKTC (Fig. 8A to C) and IC50 (Fig. 8E) values and also of IC50 with MICKTC (Fig. 8D) were revealed by scatter plot analysis and linear regression fitting of the data points after logarithmic conversion. The scatter plot of the log IC50 and log IC3b values for Pdr5p revealed a distinct trend for the subpopulation of M series aminophenothiazine inhibitors (Fig. 8E; Table 2). When this subset of the most closely structurally related compounds was treated separately in the regression analysis, there was an increase in Pearson's correlation coefficient, from 0.86 (P < 0.0001; r2 = 0.73) for all compounds to 0.92 (P < 0.007; r2 = 0.86) for the M series and 0.93 (P < 0.0001; r2 = 0.86) for the rest of the population. The log IC3b and log MICKTC parameters for Cdr1p and Snq2p also showed high degrees of correlation (r = 0.91, P < 0.0001, and r2 = 0.83 for Cdr1p and r = 0.92, P < 0.0001, and r2 = 0.85 for Snq2p) (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Correlation of parameters of inhibition of MDR transporters Pdr5p, Cdr1p, and Snq2p by a series of phenothiazines and related molecules obtained in the new HTS assay with those measured by previously established procedures. (A to C) Scatter plots of logarithms of MICKTC values (MICs obtained in the presence of a subinhibitory KTC concentration) versus logarithms of IC3b (inhibitor concentration resulting in a threefold increase in the fluorescence signal over the background) (Table 2). A linear fit with Pearson's correlation coefficient of 0.92, a P value of <0.0001, and a coefficient of determination of 0.85 is presented for Pdr5p. The correlations for Cdr1p (r = 0.91, P < 0.0001, and r2 = 0.83) and Snq2p (r = 0.92, P < 0.0001, and r2 = 0.85) are also shown. (D) Scatter plot of logarithms of MICKTC values versus logarithms of IC50s for inhibition of Pdr5p-mediated rhodamine 6G transport in isolated plasma membranes. A linear fit with a correlation coefficient of 0.92, a P value of <0.0001, and an r2 value of 0.85 is shown. (E) Scatter plot of logarithms of IC3b values versus logarithms of IC50s. Linear fits with the combined set of data (r = 0.86, P < 0.0001, and r2 = 0.73) and with two subsets of compounds showing close structural similarity within the subgroup, i.e., the M series (gray dots) (r = 0.93, P < 0.007, and r2 = 0.86) and others (white dots) (r = 0.93, P < 0.0001, and r2 = 0.86), are shown. Number designations correspond to those in Table 2, summarizing the structures of the compounds.

Similarities and differences in phenothiazine derivative inhibitory potencies against Cdr1p, Pdr5p, and Snq2p.

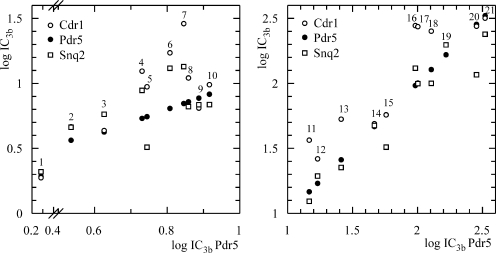

The analysis of the IC3b values for strains overproducing Cdr1p, Pdr5p, and Snq2p revealed the major influence of the acyl chain substituent at position 10 of the phenothiazine ring (the nitrogen atom) on their inhibitory activity. The most active compounds (M961 [compound 1] and M963 [compound 2]) (Fig. 9; Table 2) contained the primary amine group at the end of the butylene chains. Shortening them by one carbon atom decreased the potency, as seen with M942 (compound 3) and M962 (compound 9). The compounds containing a piperazinyl group (e.g., fluphenazine [compound 4] and trifluoperazine [compound 10]) or piperidine (thioridazine [compound 12]) in their acyl chain followed. The phenothiazine derivatives containing a tertiary amine, including promazine, promethazine, and diethazine, were the least potent. The influence of the functional group at position 2 on inhibition (Fig. 9; Table 2) was highest in the most active aminophenothiazines. These contained a Cl atom, whereas substitution with CF3 and H strongly decreased the inhibition potency in both series containing butylene or propylene acyl chains. The substituents at position 2 also had a strong influence on the sensitivity of particular transporters to inhibition. Whereas the derivatives containing Cl and CF3 (M961 [compound 1], M942 [compound 3], M963 [compound 2], and M962 [compound 9]) inhibited Cdr1p, Pdr5p, and Snq2p with similar potencies, differences were observed with the H-substituted series compounds M960 (compound 7) and M959 (compound 11). M960 (compound 7) was the most potent inhibitor of Pdr5p, whereas Snq2p showed an intermediate sensitivity and Cdr1p was the least sensitive (Fig. 9). A different order of sensitivity, Cdr1p > Pdr5p > Snq2p, was observed with trifluoperazine (compound 10), prochlorperazine (compound 8), and thiethylperazine (compound 5), containing CF3, Cl, and S-CH2-CH3 functional groups at position 2, respectively, with the last producing the largest difference (Fig. 9). Also, M959 (compound 11) was less effective against Cdr1p, whereas Snq2p and Pdr5p showed similar sensitivities. Patterns similar to that of M959 (compound 11) were observed with promazine (compound 16), prochlorperazine (compound 8), dextromepromazine (compound 17), levomepromazine (compound 16), and the structurally related dibenzazepine imipramine (compound 19) (Fig. 9), illustrating that the combination of the acyl chain and the position 2 substituent affects the preference toward a particular transporter.

FIG. 9.

Similarities and differences in responses of MDR transporters Pdr5p, Cdr1p, and Snq2p to inhibition by a series of phenothiazines and related molecules. The scatter plots show the logarithms of the IC3b values (inhibitor concentration resulting in a threefold increase in the fluorescence signal over the background) measured in the new HTS assay for Pdr5p versus those for Cdr1p and Snq2p as well as those for Pdr5p itself (following the equity line). The closer to the equity line a data point is for Snq2p and Cdr1p (vertically), the more similar is its effect to that exerted on Pdr5p. More potent inhibitors with lower log IC3b values are in the lower left corner, and the less potent inhibitors are in the upper right corner. The graph is split into two parts for better data point visibility. The scaling for the vertical axes is the same. Number designations correspond to those in Table 2, summarizing the structures of the compounds.

M961 potentiates KTC antifungal activity against the resistant Cdr1p-overproducing C. albicans isolate better than fluphenazine does.

To verify whether the newly identified and most potent Cdr1p inhibitor M961 shows activity against C. albicans, its effect against an MDR Cdr1p-overproducing isolate was verified. It was also compared in parallel with fluphenazine, which has previously been shown to potentiate the antifungal effect of fluconazole (33). The checkerboard assay comparing the effects of KTC and inhibitor alone and those of both compounds in combination allowed us to calculate the corresponding fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) and FICindex values (11, 58). The MIC of KTC alone of 0.92 μM decreased to 0.03 μM in the presence of M961 and to 0.06 μM in the presence of fluphenazine. The MIC of M961 alone of 74.6 μM decreased to 2.3 μM in the presence of KTC, whereas the MIC of fluphenazine alone of 149.3 μM decreased to 4.7 μM. The corresponding FICindex values for M961 (0.06) and fluphenazine (0.09) indicated a synergistic interaction with KTC for both compounds (40). The lower FICindex observed for M961 than that for fluphenazine was in agreement with the higher potency of Cdr1p inhibition observed in the new S. cerevisiae-based fluorescence assay.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we developed and characterized a new fluorescence-based assay allowing the fast, precise, and economical measurement of MDR efflux pump inhibition in whole cells upon overproduction in S. cerevisiae. It is based on a compound's ability to interfere with MDR transporter-mediated extrusion of FDA from the plasma membrane, leading to increased intracellular accumulation. This resulted in an increase in fluorescence intensity due to cleavage by intracellular esterases, which was measured homogeneously in whole cells in real time and quantified. The assay allowed the identification of new inhibitors of Cdr1p, the major MDR pump of the important human fungal pathogen C. albicans, and for rapid comparison of their effects on related MDR transporters.

Target-oriented screening of MDR transporter inhibitors in S. cerevisiae is an attractive alternative to screening in related pathogenic yeasts, thanks to the better knowledge of the network of pleiotropic drug resistance genes and the ease of genetic manipulation in this organism, which for many years served as a model eukaryote. This knowledge was important for reduction of the background of the most prominent interfering endogenous MDR efflux activities by deletion and for increasing the sensitivity and dynamic range of the assay by overproduction of target transporters in plasma membranes. S. cerevisiae has successfully been used in the past for HTS applications upon heterologous expression of target proteins (36). The high-level functional expression of several drug transporters from pathogenic fungi as well as those responsible for human cancer cell resistance to chemotherapy has also been achieved in this organism, with proper targeting to the plasma membrane (12, 37). Finally, this approach combined with traditional growth-based screening resulted in the identification of most of the few known efflux pump inhibitors that are active against pathogenic fungi (39, 54).

The availability of previously developed methods for measurement of endogenous MDR transporter activities, in particular the rhodamine 6G transport assay for Pdr5p in the isolated plasma membrane fractions (27), and knowledge of the drug resistance profiles of Pdr5p and Snq2p (25) were additional advantages allowing for comparison of the new assay with established procedures.

The advantage of the new whole-cell assay format over measurements at the subcellular level lies in its simplicity and ease of manipulation, as it does not require preparations which are laborious, costly, and often difficult to perform on a large scale. This is of particular importance in initial screening steps and when rapid comparison of the effects of inhibitors on multiple MDR transporters or their variants is needed. It also allows the elimination of potential lead compounds which cannot be used due to low penetration or instability in cells.

The advantages of the new assay over other methods traditionally used for the characterization of MDR transporter inhibitors with whole cells, which are mainly based on the ability of tested compounds to potentiate the action of the effluxed cytotoxic drug on growth (14, 34), include reduced time and handling as well as increased precision. This was achieved thanks to a high sensitivity, dynamic range, and real-time detection without the necessity to separate cells from the reaction mixture, in contrast to methods employing radiolabeled or other fluorescent substrates, including anthracyclines and rhodamine derivatives (3, 23, 24, 27).

In the search for MDR transporter substrates allowing for more sensitive fluorescence-based detection in S. cerevisiae, we found that Pdr5p and Snq2p decrease the intracellular accumulation of FDA. This profluorochrome was previously found to diffuse through the plasma membrane into S. cerevisiae cells, where it was hydrolyzed to free fluorescein by esterases, whose activity was constant during culture growth (4). Our finding was unexpected based on the previous observation that this process did not depend on the MDR modulators reserpine and verapamil (4), but a clear increase in intracellular FDA accumulation was observed upon deletion of the endogenous MDR transporter genes PDR5 and SNQ2. This effect was complemented by corresponding plasmid-borne genes and also by CDR1 of C. albicans, which was in agreement with the observation by Yang et al. (61) that this transporter affects FDA accumulation in C. albicans. This indicated that FDA may be a universal substrate suitable for HTS measurement of inhibition of multiple MDR efflux pumps significantly differing in their resistance spectra in S. cerevisiae. The high dynamic response of the assay achieved upon overproduction of Cdr1p, Pdr5p, or Snq2p from a common promoter in a host devoid of endogenous copies of PDR5, SNQ2, and YOR1 is comparable to that observed with calcein-AM, which is used to monitor the activity of the human MDR efflux pumps P-glycoprotein (ABCB1) and MRP (ABCC1) expressed in the mammalian system (19, 49), and largely exceeds those observed with other known procedures.

The series of closely related phenothiazine derivatives was chosen to evaluate the assay's performance due to their ability to reverse MDR resistance in bacterial (20), cancer (13, 44), and yeast (26) cells. Although fluphenazine was previously shown to potentiate the effect of fluconazole on C. albicans, the activities of other phenothiazines, including several new ones against Cdr1p as well as Snq2p, were not tested so far. Snq2p was included to verify the assay performance with MDR transporters with significantly different resistance profiles, and the specificities of Pdr5p and Snq2p of S. cerevisiae are the best described, to our knowledge, among those of yeast MDR transporters (25). The analysis revealed several new inhibitors of Cdr1p, with the most potent aminoacyl derivative, M961, acting in the low micromolar range. It also showed similarities and differences in the inhibition profiles of the transporters Cdr1p, Snq2p, and Pdr5p, thanks to their similar expression levels found in plasma membranes and similar FDA extrusion activities. The most spectacular difference was in the response to phenothiazine, which specifically inhibited Snq2p with no effect on Pdr5p and Cdr1p. Similar differential responses were observed in the traditional growth assay, based on the potentiation of the antifungal effect of KTC, which was detoxified to similar extents by the three analyzed transporters. These differential effects were not related to the differential toxicity of the analyzed phenothiazines, as the analyzed strains did not differ in their susceptibility to compounds differently potentiating the response of Cdr1p-, Pdr5p-, and Snq2p-overproducing strains to KTC, such as M961, fluphenazine (Fig. 6), or phenothiazine, which did not inhibit yeast growth at all.

Interestingly, the overproduced transporters conferred a low level, usually two- to fourfold, of resistance to most analyzed phenothiazines (Table 2). This, together with their differential effect on tested transporters, indicated that these phenothiazines are poorly translocated substrates interacting with the transported drug-binding sites. The structural similarity of the specific Snq2p inhibitor phenothiazine to specific Snq2p substrates, such as 4-NQO, phenanthroline (50), and resazurine (25), further supports this view. Finally, these compounds inhibited Pdr5p-mediated rhodamine 6G transport in isolated plasma membrane fractions. This assay is unique in its performance, allowing for detailed characterization of Pdr5p inhibitors (5, 27), and similar procedures with subcellular fractions have not been described for other fungal MDR transporters. Although we tried to adapt this method for measuring inhibition of Cdr1p activity in the microplate format, the lower dynamic range in this setup than that with Pdr5p did not allow for a large-scale analysis. This was in agreement with the lower level of rhodamine 6G resistance conferred by Cdr1p in growth assays (data not shown). The ability to inhibit Pdr5p-mediated rhodamine 6G transport in isolated plasma membranes was previously shown to be related to direct binding to the protein for a series of prenyl flavonoids (5). The direct phenothiazine binding to the NorA MDR transporter of Staphylococcus aureus as well as to the human P-glycoprotein has been suggested to make an important contribution to inhibition of these efflux pumps (20, 30). A point mutation in P-glycoprotein has also been shown to affect the interaction with the thioxanthenes cis- and trans-flupentixol, which are structurally closely related to phenothiazines (9).

The ability of Cdr1p, Pdr5p, and Snq2p to extrude FDA directly from the plasma membrane before it reaches the cytoplasm indicates that the transported substrates are recognized while crossing the membrane. Thus, the membrane interactions of substrate-resembling inhibitors should be an important factor affecting their activity. However, analysis of the most potent inhibitors, the aminophenothiazines (M series), revealed a different order of potency from that suggested by their liposome-buffer partition coefficients. Similarly, the inhibition of P-glycoprotein did not correlate with lipophilicity and the membrane-perturbing potency of these compounds (18), pointing to the importance of their specific interactions with drug efflux pumps.

The new parameter IC3b, the inhibitor concentration causing a threefold increase in fluorescence signal over the background, was identified as a quantitative measure of the inhibition potency in the new assay, as estimation of IC50s was not possible because the plateau in the dose-response curves could not be obtained in most cases due to toxicity. Although a similar approach to quantifying P-glycoprotein inhibitor potency with the calcein-AM assay was attempted, the concentration causing a twofold increase over the background (f2) was used (57). The availability of alternative methods of inhibitor potency measurements with the S. cerevisiae expression system, such as the traditional growth-based assay with a subinhibitory KTC concentration and, in particular, the precise method of IC50 measurement of Pdr5p-mediated rhodamine 6G transport inhibitors with isolated plasma membranes (27), allowed for correlation analysis of the results obtained by the three approaches. The IC3b values not only proved more reproducible than concentrations causing a twofold increase but also showed a higher level of correlation with the results of other methods.

The CgSnq2p protein of Candida glabrata, a homologue of the S. cerevisiae protein Snq2p, was recently shown to confer resistance to 4-NQO, fluconazole, and KTC (55). Our observation that Snq2p confers a level of KTC resistance similar to that by Cdr1p upon normalization of the expression level, although its specificity for other azoles, such as clotrimazole, is more limited, is important for the treatment of C. glabrata, which generally shows low azole susceptibility. Identification of a phenothiazine as a specific Snq2p inhibitor indicates the possible use of its close structural derivatives in increasing the potency of azoles against C. glabrata.

The identification of M961 as a new Cdr1p inhibitor that is more effective than fluphenazine in potentiating the antifungal effect of KTC on C. albicans demonstrates the predictive power of the new HTS assay. This method is an important new tool which should make a significant contribution to the identification of new inhibitors of drug efflux pumps of clinical importance to fight the threat of MDR pathogens.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Antoni Polanowski and Jacek Otlewski for sharing laboratory equipment, to Scott Moye-Rowley for sharing equipment and materials, to Theodore White for the Candida albicans isolate, and to Joseph Molnar for the gift of amineptine, dextromepromazine, diethazine, levomepromazine, and thiethylperazine.

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education grant 2P05A 080 28 and by funds from the Wroclaw Medical University.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 February 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Balzi, E., M. Wang, S. Leterme, L. Van Dyck, and A. Goffeau. 1994. PDR5, a novel yeast multidrug resistance conferring transporter controlled by the transcription regulator PDR1. J. Biol. Chem. 269:2206-2214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boeke, J. D., F. LaCroute, and G. R. Fink. 1984. A positive selection for mutants lacking orotidine-5′-phosphate decarboxylase activity in yeast: 5-fluoro-orotic acid resistance. Mol. Gen. Genet. 197:345-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosch, I., C. L. Crankshaw, D. Piwnica-Worms, and J. M. Croop. 1997. Characterization of functional assays of multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein transport activity. Leukemia 11:1131-1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breeuwer, P., J. L. Drocourt, N. Bunschoten, M. H. Zwietering, F. M. Rombouts, and T. Abee. 1995. Characterization of uptake and hydrolysis of fluorescein diacetate and carboxyfluorescein diacetate by intracellular esterases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which result in accumulation of fluorescent product. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:1614-1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conseil, G., A. Decottignies, J. M. Jault, G. Comte, D. Barron, A. Goffeau, and A. Di Pietro. 2000. Prenyl-flavonoids as potent inhibitors of the Pdr5p multidrug ABC transporter from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemistry 39:6910-6917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Decottignies, A., L. Lambert, P. Catty, H. Degand, E. A. Epping, W. S. Moye-Rowley, E. Balzi, and A. Goffeau. 1995. Identification and characterization of SNQ2, a new multidrug ATP binding cassette transporter of the yeast plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 270:18150-18157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Decottignies, A., M. Kolaczkowski, E. Balzi, and A. Goffeau. 1994. Solubilization and characterization of the overexpressed PDR5 multidrug resistance nucleotide triphosphatase of yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 269:12797-12803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delaveau, T., A. Delahodde, E. Carvajal, J. Subik, and C. Jacq. 1994. PDR3, a new yeast regulatory gene, is homologous to PDR1 and controls the multidrug resistance phenomenon. Mol. Gen. Genet. 244:501-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dey, S., P. Hafkemeyer, I. Pastan, and M. M. Gottesman. 1999. A single amino acid residue contributes to distinct mechanisms of inhibition of the human multidrug transporter by stereoisomers of the dopamine receptor antagonist flupentixol. Biochemistry 38:6630-6639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dufour, J. P., A. Amory, and A. Goffeau. 1988. Plasma membrane ATPase from the yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 157:513-528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eliopoulos, G. M., and R. C. Moellering. 1991. Antimicrobial combinations, p. 432-492. In V. Lorian (ed.), Antibiotics in laboratory medicine, 3rd ed. The Williams and Wilkins Co., Baltimore, MD.

- 12.Figler, R. A., H. Omote, R. K. Nakamoto, and M. K. Al-Shawi. 2000. Use of chemical chaperones in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae to enhance heterologous membrane protein expression: high-yield expression and purification of human P-glycoprotein. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 376:34-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ford, J. M., and W. N. Hait. 1990. Pharmacology of drugs that alter multidrug resistance in cancer. Pharmacol. Rev. 42:155-190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerberick, G. F., and P. A. Castric. 1980. In vitro susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to carbenicillin, glycine, and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid combinations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 17:732-735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gietz, R. D., R. H. Schiestl, A. R. Willems, and R. A. Woods. 1995. Studies on the transformation of intact yeast cells by the LiAc/SS-DNA/PEG procedure. Yeast 11:355-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldstein, A. L., X. Pan, and J. H. McCusker. 1999. Heterologous URA3MX cassettes for gene replacement in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 15:507-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guarente, L. 1983. Yeast promoter and lacZ fusions designed to study expression of cloned genes in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 101:181-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hendrich, A. B., O. Wesołowska, A. Poła, N. Motohashi, J. Molnár, and K. Michalak. 2003. Neither lipophilicity nor membrane-perturbing potency of phenothiazine maleates correlate with the ability to inhibit P-glycoprotein transport activity. Mol. Membr. Biol. 20:53-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Homolya, L., Z. Hollo, U. A. Germann, I. Pastan, M. M. Gottesman, and B. Sarkadi. 1993. Fluorescent cellular indicators are extruded by the multidrug resistance protein. J. Biol. Chem. 268:21493-21496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaatz, G. W., V. V. Moudgal, S. M. Seo, and J. E. Kristiansen. 2003. Phenothiazines and thioxanthenes inhibit multidrug efflux pump activity in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:719-726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katzmann, D. J., E. A. Epping, and W. S. Moye-Rowley. 1999. Mutational disruption of plasma membrane trafficking of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Yor1p, a homologue of mammalian multidrug resistance protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:2998-3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katzmann, D. J., P. E. Burnett, J. Golin, Y. Mahé, and W. S. Moye-Rowley. 1994. Transcriptional control of the yeast PDR5 gene by the PDR3 gene product. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:4653-4661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessel, D., W. T. Beck, D. Kukuruga, and V. Schulz. 1991. Characterization of multidrug resistance by fluorescent dyes. Cancer Res. 51:4665-4670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolaczkowska, A., M. Kolaczkowski, A. Goffeau, and W. S. Moye-Rowley. 2008. Compensatory activation of the multidrug transporters Pdr5p, Snq2p, and Yor1p by Pdr1p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 582:977-983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kolaczkowski, M., A. Kolaczowska, J. Luczynski, S. Witek, and A. Goffeau. 1998. In vivo characterization of the drug resistance profile of the major ABC transporters and other components of the yeast pleiotropic drug resistance network. Microb. Drug Resist. 4:143-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kolaczkowski, M., K. Michalak, and N. Motohashi. 2003. Phenothiazines as potent modulators of yeast multidrug resistance. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 22:279-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolaczkowski, M., M. van der Rest, A. Cybularz-Kolaczkowska, J. P. Soumillion, W. N. Konings, and A. Goffeau. 1996. Anticancer drugs, ionophoric peptides, and steroids as substrates of the yeast multidrug transporter Pdr5p. J. Biol. Chem. 271:31543-31548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leppert, G., R. McDevitt, S. C. Falco, T. K. Van Dyk, M. B. Ficke, and J. Golin. 1990. Cloning by gene amplification of two loci conferring multiple drug resistance in Saccharomyces. Genetics 125:13-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu, R., A. Siemiarczuk, and F. J. Sharom. 2000. Intrinsic fluorescence of the P-glycoprotein multidrug transporter: sensitivity of tryptophan residues to binding of drugs and nucleotides. Biochemistry 39:14927-14938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Longtine, M. S., A. McKenzie III, D. J. Demarini, N. G. Shah, A. Wach, A. Brachat, P. Philippsen, and J. R. Pringle. 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14:953-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahé, Y., Y. Lemoine, and K. Kuchler. 1996. The ATP binding cassette transporters Pdr5 and Snq2 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae can mediate transport of steroids in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 271:25167-25172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marchetti, O., P. Moreillon, M. P. Glauser, J. Bille, and D. Sanglard. 2000. Potent synergism of the combination of fluconazole and cyclosporine in Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2373-2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Markham, P. N., E. Westhaus, K. Klyachko, M. E. Johnson, and A. A. Neyfakh. 1999. Multiple novel inhibitors of the NorA multidrug transporter of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2404-2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Motohashi, N., M. Kawase, J. Molnár, L. Ferenczy, O. Wesolowska, A. B. Hendrich, M. Bobrowska-Hägerstrand, H. Hägerstrand, and K. Michalak. 2003. Antimicrobial activity of N-acylphenothiazines and their influence on lipid model membranes and erythrocyte membranes. Arzneimittelforschung 53:590-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Munder, T., and A. Hinnen. 1999. Yeast cells as tools for target oriented screening. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 52:311-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakamura, K., M. Niimi, K. Niimi, A. R. Holmes, J. E. Yates, A. Decottignies, B. C. Monk, A. Goffeau, and R. D. Cannon. 2001. Functional expression of Candida albicans drug efflux pump Cdr1p in a Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain deficient in membrane transporters. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3366-3374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1997. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. Approved standard M27-A. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, PA.

- 39.Niimi, K., D. R. Harding, R. Parshot, A. King, D. J. Lun, A. Decottignies, M. Niimi, S. Lin, R. D. Cannon, A. Goffeau, and B. C. Monk. 2004. Chemosensitization of fluconazole resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and pathogenic fungi by a d-octapeptide derivative. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1256-1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Odds, F. C. 2003. Synergy, antagonism, and what the chequerboard puts between them. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pfaller, M. A., and D. J. Diekema. 2002. Role of sentinel surveillance of candidemia: trends in species distribution and antifungal susceptibility. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3551-3557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prasad, R., N. A. Gaur, M. Gaur, and S. S. Komath. 2006. Efflux pumps in drug resistance of Candida. Infect. Disord. Drug Targets 6:69-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prasad, R., P. De Wergifosse, A. Goffeau, and E. Balzi. 1995. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel gene of Candida albicans, CDR1, conferring multiple resistance to drugs and antifungals. Curr. Genet. 4:320-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramu, A., and N. Ramu. 1992. Reversal of multidrug resistance by phenothiazines and structurally related compounds. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 30:165-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reid, R. J. D., M. Lisby, and R. Rothstein. 2002. Cloning-free genome alterations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using adaptamer-mediated PCR. Methods Enzymol. 350:258-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanglard, D., and J. Bille. 2002. Current understanding of the modes of action and resistance mechanisms to conventional and emerging antifungal agents for treatment of Candida infections, p. 349-387. In R. A. Calderone (ed.), Candida and candidiasis. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 47.Sanglard, D., F. Ischer, M. Monod, and J. Bille. 1996. Susceptibilities of Candida albicans multidrug transporter mutants to various antifungal agents and other metabolic inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2300-2305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanglard, D., F. Ischer, M. Monod, and J. Bille. 1997. Cloning of Candida albicans genes conferring resistance to azole antifungal agents: characterization of CDR2, a new multidrug ABC transporter gene. Microbiology 143:405-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sarkadi, B., L. Homolya, and Z. Hollo. August 2001. Assay and reagent kit for evaluation of multi-drug resistance in cells. U.S. patent 6,277,655.

- 50.Servos, J., E. Haase, and M. Brendel. 1993. Gene SNQ2 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which confers resistance to 4-nitroquinoline-N-oxide and other chemicals, encodes a 169 kDa protein homologous to ATP-dependent permeases. Mol. Gen. Genet. 236:214-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shukla, S., P. Saini, Smriti, S. Jha, S. V. Ambudkar, and R. Prasad. 2003. Functional characterization of Candida albicans ABC transporter Cdr1p. Eukaryot. Cell 2:1361-1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sikorski, R. S., and P. Hieter. 1989. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122:19-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Souid, A. K., C. Gao, L. Wang, E. Milgrom, and W. C. Shen. 2006. ELM1 is required for multidrug resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 173:1919-1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tanabe, K., E. Lamping, K. Adachi, Y. Takano, K. Kawabata, Y. Shizuri, M. Niimi, and Y. Uehara. 2007. Inhibition of fungal ABC transporters by unnarmicin A and unnarmicin C, novel cyclic peptides from marine bacterium. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 364:990-995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Torelli, R., B. Posteraro, S. Ferrari, M. La Sorda, G. Fadda, D. Sanglard, and M. Sanguinetti. 2008. The ATP-binding cassette transporter-encoding gene CgSNQ2 is contributing to the CgPDR1-dependent azole resistance of Candida glabrata. Mol. Microbiol. 68:186-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Towbin, H., T. Staehelin, and J. Gordon. 1979. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:4350-4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weiss, J., S. M. Dormann, M. Martin-Facklam, C. J. Kerpen, N. Ketabi-Kiyanvash, and W. E. Haefeli. 2003. Inhibition of P-glycoprotein by newer antidepressants. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 305:197-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.White, R. L., D. S. Burgess, M. Manduru, and J. A. Bosso. 1996. Comparison of three different in vitro methods of detecting synergy: time-kill, checkerboard, and E test. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:1914-1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.White, T. C., S. Holleman, F. Dy, L. F. Mirels, and D. A. Stevens. 2002. Resistance mechanisms in clinical isolates of Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 6:1704-1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wilson, R. B., D. Davis, B. M. Enloe, and A. P. Mitchell. 2000. A recyclable Candida albicans URA3 cassette for PCR product-directed gene disruptions. Yeast 16:65-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang, H. C., Y. Mikami, T. Imai, H. Taguchi, K. Nishimura, M. Miyaji, and M. L. Branchini. 2001. Extrusion of fluorescein diacetate by multidrug-resistant Candida. Mycoses 44:368-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang, J. H., T. D. Y. Chung, and K. R. Oldenburg. 1999. A simple statistical parameter for use in evaluation and validation of high throughput screening assays. J. Biomol. Screen. 4:67-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]