Abstract

Imino sugars, such as N-butyl-deoxynojirimycin and N-nonyl-deoxynojirimycin (NNDNJ), are glucose analogues that selectively inhibit cellular α-glucosidase I and II in the endoplasmic reticulum and exhibit antiviral activities against many types of enveloped viruses. Although these molecules have broad-spectrum antiviral activity, their development has been limited by a lack of efficacy and/or selectivity. We have previously reported that a DNJ derivative with a hydroxylated cyclohexyl side chain, called OSL-95II, has an antiviral efficacy similar to that of NNDNJ but significantly less toxicity. Building upon this observation, a family of imino sugar derivatives containing an oxygenated side chain and terminally restricted ring structures were synthesized and shown to have low cytotoxicity and superior antiviral activity against members of the Flaviviridae family, including bovine viral diarrhea virus, dengue virus (DENV), and West Nile virus. Of particular interest is that several of these novel imino sugar derivatives, such as PBDNJ0801, PBDNJ0803, and PBDNJ0804, potently inhibit DENV infection in vitro, with 90% effective concentration values at submicromolar concentrations and selectivity indices greater than 800. Therefore, these compounds represent the best in their class and may offer realistic candidates for the development of antiviral therapeutics against human DENV infections.

Imino sugars are glucose mimetics with a nitrogen atom in place of a ring oxygen (11). Some imino sugar derivatives, such as deoxynojirimycin (DNJ), competitively inhibit cellular endoplasmic reticulum (ER) α-glucosidases I and II (11). ER α-glucosidases remove glucose residues from the high-mannose N-linked glycans attached to nascent glycoproteins (16), which is critical for the subsequent interaction between the glycoproteins and ER chaperones calnexin and calreticulin. It has been shown that such interaction is required for the correct folding and sorting of some but not all glycoproteins (11, 16). Thus, it has been reasoned that inhibition of α-glucosidases might disturb the maturation, secretion, and function of viral envelope glycoproteins and, as a result, inhibit viral particle assembly and/or secretion of enveloped viruses. Consistent with this notion is the observation that for many types of enveloped viruses, including hepatitis B virus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), herpes simplex virus type 1, influenza viruses, parainfluenza virus, and measles virus, as well as several members of the Flaviviridae family, such as bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV), dengue virus (DENV), West Nile virus (WNV), Japanese encephalitis virus, and hepatitis C virus (HCV), virion production can be inhibited by α-glucosidase inhibitors, such as DNJ and its derivatives (3, 5, 6, 9, 14, 17, 22, 30, 31, 34). For some viruses, virion particles produced under treatment with glucosidase inhibitors carried unprocessed (or altered) glycans on their envelope glycoproteins and were reduced in infectivity (17, 26). Moreover, it was shown that a DNJ derivative inhibited infection by DENV (28, 32) and Japanese encephalitis virus (33) in mice and by woodchuck hepatitis virus in woodchucks (4).

Despite their great potential, the development of imino sugars as broad-spectrum antiviral agents is limited by their relatively low efficacy and unfavorable toxicity profiles. The prototype imino sugars DNJ and N-butyl-DNJ (NBDNJ) have 50% effective concentration (EC50) values at the millimolar level. These concentrations are difficult to achieve in vivo and, thus, their antiviral utility is limited. DNJs with longer alkylated side chains on the nitrogen atom, such as N-nonyl-DNJ (NNDNJ), have dramatically improved antiviral efficacies, with EC50 values in the low micromolar range. However, such modification also increased the cytotoxicity of the imino sugar.

In an effort to optimize the nitrogen-linked alkylated side chain structure, we produced N-pentyl-(1-hydroxycyclohexyl)-DNJ (OSL-95II), which had a reduced cytotoxicity while retaining micromolar antiviral activity against BVDV, DENV, and WNV (14). The characteristic feature of OSL-95II is a 5-carbon alkylated side chain with a terminal cyclohexyl ring structure (Fig. 1). In the present study, we took several approaches to further modify OSL-95II by changing the length and/or composition of the nitrogen-linked side chain. We report here several novel imino sugars with not only better toxicity profiles but also superior antiviral activities against BVDV, DENV, and WNV in cell cultures. Of particular interest is that several novel imino sugar derivatives demonstrated strong antiviral effects against DENV infection, with EC90 values at 0.2 to 0.6 μM. This represents the first group of imino sugars we have tested that have antiviral activity, in vitro, in the submicromolar range and thus are potential candidates for further development as antiviral agents against DENV infection.

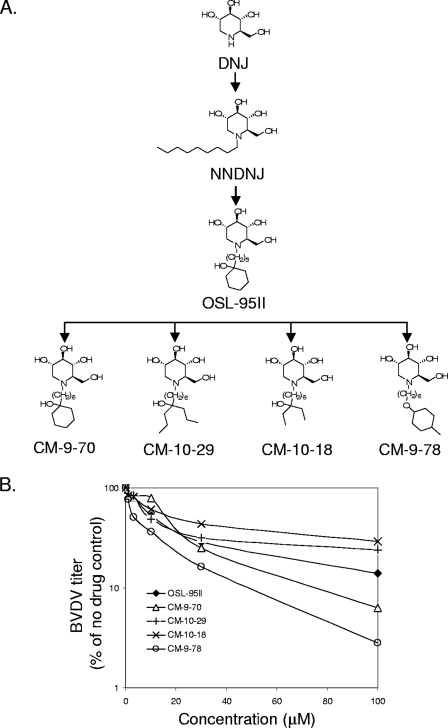

FIG. 1.

Structure and antiviral effects of OSL-95II and its derivatives. (A) Structures of the prototype DNJ, NNDNJ, and of OSL-95II and its derivatives with modifications on the N-linked side chain. CM-9-70 contains an extended side chain. The terminal ring of OSL-95II is opened in compounds CM-10-29 and CM-10-18. In compound CM-9-78, the oxygen atom in the hydroxyl group of the terminal ring structure is moved to the alkylated chain. (B) Anti-BVDV activity of OSL-95II and its derivatives. MDBK cells were infected with BVDV at an MOI of 1 for 1 h. After removal of unbound virus, the desired compounds were added at the indicated concentrations. Supernatants were harvested at 24 h postinfection to determine the virus yield by plaque assay. BVDV titers in the culture media were plotted as percentage of results for untreated control. Each curve represents average values from at least three independent experiments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and viruses.

Madin-Darby bovine kidney cells (MDBK) and baby hamster kidney cells were cultured as previously described (14). The cytopathic NADL strain of BVDV, the serotype 2 New Guinea C strain of DENV, and a 2002 Texas isolate of WNV were as previously described (13, 26).

Compounds.

Alkylated DNJ derivatives were designed and synthesized by Michael Xu at Pharmabridge, Inc., and the Hepatitis B Foundation and by Robert Moriarty at the University of Illinois. The methods of synthesizing these compounds will be reported elsewhere.

Virus yield reduction assay.

For BVDV infection, 2 × 105 MDBK cells were seeded in 24-well plates. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were infected with BVDV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 in 100 μl complete medium. After adsorption for 1 h at 37°C, unbound virus was removed by washing with serum-free medium, followed by the addition of fresh medium and compounds at concentrations indicated below. To determine virus titers, culture media were harvested 24 h after infection for a standard plaque-forming assay as described previously (14, 17). Briefly, MDBK cells were infected with serial dilutions of culture medium harvested from infected cells with or without treatment. After 1 h of absorption, the cells were washed, overlaid with medium containing methylcellulose, and incubated at 37°C for 3 days. Plaques were counted under a microscope or after being stained with neutral red. The dose-dependent plaque yield reduction curves were then plotted to determine the EC50 and EC90 values.

The antiviral activity against WNV was evaluated in a yield reduction assay as previously described (14). Briefly, baby hamster kidney cell cells were plated in 96-well plates and infected with WNV at an MOI of 0.05 for 1 h. After the removal of the inoculums, the cells were treated with the test compounds at concentrations indicated below for 48 h at 37°C. The supernatants were then collected for detection of the virus titers. Monolayers of Vero cells were infected for 1 h with various dilutions of the culture media harvested from infected cells with or without treatment, followed by overlay with media containing 0.6% tragacanth (ICN, CA) and incubation at 37°C for 24 to 30 h. Viral foci were detected by immunostaining as described previously (27). For antiviral testing against DENV (serotype 2), treatment with test compounds and detection of virus titers were performed essentially as described for WNV, except that the treatment of infected cells and plaque forming were both continued for 72 h and foci were visualized by immunostaining using hybridoma culture fluid (13).

Cytotoxicity assay.

To determine cellular viability with the test compounds, a 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT)-based assay was performed (Sigma) as previously described (14). Cells were set up and incubated under conditions that were identical to those used for the antiviral assays. The dose-dependent absorbance values at 570 nm, used as the indicator of cellular viability, were plotted to determine the concentration of compounds required for 50% inhibition of cell survival (CC50).

Western blotting.

MDBK cells were infected with BVDV at an MOI of 1 and incubated with test compounds (at concentrations of 3 μM, 10 μM, 30 μM, and 100 μM) for 24 h. Cells were lysed in Laemmli buffer prior to analysis on 12% polyacrylamide gel (NuPage; Invitrogen). After electrophoresis and electrotransfer to nitrocellulose membranes, proteins were detected with mouse monoclonal antibody WB166 against BVDV E2 protein (Central Veterinary Laboratories, Surrey, United Kingdom), followed by goat anti-mouse infrared dye-labeled secondary antibodies (LI-COR). Detection and quantitation were performed with an Odyssey apparatus (LI-COR).

Detection of BVDV RNA by real-time RT-PCR assay.

MDBK cells were infected with BVDV at an MOI of 1 for 1 h and incubated with 100 μM of OSL-95II or 80 μM of CM-9-78. Total RNA was extracted from cells at indicated time points after infection (see Fig. 4A) by using Trizol (Invitrogen). To detect extracellular BDVD RNA, culture media were harvested 24 h after infection and centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 10 min to clarify the dead cells from the media. Cell culture media were diluted 1:5 and then heated at 96°C to denature RNA. Amounts of 5 to 50 ng of total RNA or 5 μl of diluted culture media were used for real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) assay, using the TaqMan probe (5′-AACAGTGGTGAGTTGGTTGGATGGCTT-3′) and BVDV primers (5′-TAGCCATGCCCTTAGTAGGAC-3′ and 5′-GACGACTACCCTGTACTCAGG-3′) (2). Real-time RT-PCR to detect BVDV genomic RNA was conducted by using a One-Step RT-PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

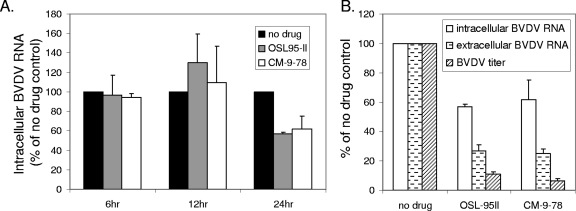

FIG. 4.

Antiviral mechanism of OSL-95II and CM-9-78 against BVDV infection. (A) MDBK cells were infected with BVDV at an MOI of 1, followed by incubation with OSL-95II (100 μM) or CM-9-78 (80 μM) for the indicated periods of time. Intracellular BVDV RNAs were analyzed by real-time RT-PCR, and results plotted as percentage of results for untreated control at each time point. (B) MDBK cells were infected and treated as described for panel A. Cells and media were harvested at 24 h postinfection. Effects of OSL-95II or CM-9-78 treatment on levels of intracellular BVDV RNA and extracellular virion RNA (by real-time RT-PCR) and virus titer (by plaque assay) were plotted as percentage of results for untreated controls. Values represent the means ± standard deviations of the results of three independent assays.

RESULTS

Introduction of oxygenated and terminal ring structures into the nitrogen-linked alkyl side chain on DNJ.

Compared with DNJ or DNJ with short alkyl side chains, such as NBDNJ, which has an EC50 of at least 100 to 500 μM in tissue culture against test viruses such as BVDV and DENV, DNJs with longer alkyl side chains, such as NNDNJ, have 100 times more potency and thus were considered to be significant improvements over DNJ and NBDNJ (23). However, NNDNJ was shown to be more cytotoxic than NBDNJ or DNJ, with a CC50 of ∼100 μM (2, 11).

In order to improve the antiviral efficacy and cytotoxicity, much of our effort has been focused on diversifying the length and/or composition of the nitrogen-linked side chain. Our earlier studies showed that although the introduction of an oxygen atom into the nitrogen-linked alkyl side chain dramatically reduced cytotoxicity, antiviral efficacy was compromised (23). We also described a novel imino sugar, OSL-95II, which has a 5-carbon alkylated side chain with a terminal hydroxylated cycloalkyl structure (Fig. 1A) and showed both a reduction in cytotoxicity and retention of antiviral activity (14). These results suggested that the terminal ring structure and/or oxygenation of the nitrogen-linked side chain may help reduce cytotoxicity.

In order to further improve the antiviral efficacy and yet maintain low cytotoxicity, we set out to make the following modifications on the side chain linked to the nitrogen: (i) the length of the alkyl side chain was varied (Fig. 1A, CM-9-70), (ii) the terminal ring structure was opened (Fig. 1A, CM-10-18 and CM-10-29), and (iii) the oxygen atom from the terminal ring was “moved” to the alkyl side chain (Fig. 1A, CM-9-78).

As shown in Fig. 1B and Table 1, while maintaining low toxicity in MDBK cells (CC50 > 500 μM), all four representative compounds (CM-9-70, CM-10-18, CM-10-29, and CM-9-78) demonstrated anti-BVDV activity in a yield reduction assay. In particular, compared with the results for OSL-95II, changing the length of the alkyl side chain from 5 carbons to 6 carbons (CM-9-70) did not affect the antiviral activity. Furthermore, to investigate the requirement for a terminal ring structure, the terminal ring was opened without or with trimming of the branches. The resulting compounds are called CM-10-29 and CM-10-18. It is worthy of note that CM-10-29 retains the 6-carbon branch structure after the opening of the ring. Both compounds showed antiviral activity similar to that of OSL-95II.

TABLE 1.

Summary of anti-BVDV activities and cytotoxicities of novel imino sugar derivatives in comparison with those of NNDNJ and OSL-95IIa

| Imino sugar | Activity against BVDVb

|

CC50 in MDBK cellsc | SI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 | EC90 | |||

| NNDNJ | 7.3 ± 0.4 | 71 ± 7.1 | 245 ± 134 | 33 |

| OSL95-II | 10.5 ± 2.7 | >100 | >500 | >48 |

| CM-9-70 | 18 ± 0 | 82.5 ± 0 | >500 | >28 |

| CM-10-29 | 9.5 ± 0.7 | >100 | >500 | >53 |

| CM-10-18 | 22 ± 8.5 | >100 | >500 | >23 |

| CM-9-78 | 7.1 ± 3.4 | 53 ± 22 | >500 | >70 |

| PBDNJ0801 | 1.6 ± 1.2 | 14.8 ± 3.9 | 235 ± 21 | 146 |

| PBDNJ0803 | 3 ± 3.4 | 24.9 ± 26 | 485 ± 21 | 162 |

| PBDNJ0804 | 3.3 ± 1.2 | 14.3 ± 5.5 | >500 | >151 |

| PBDNJ0805 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 22 ± 11.3 | >500 | >172 |

| PBDNJ0806 | 4.5 ± 2.1 | 47 ± 32.5 | >500 | >111 |

Values represent means ± standard deviations of the results from at least three independent experiments, each including six inhibitor concentrations.

Determined by yield reduction assay.

Determined by MTT assay.

These results suggest that, in addition to a ring structure, other terminal structures may also contribute to the antiviral activity. Interestingly, CM-9-78, which contains an oxygen atom located within the side chain rather than as a hydroxyl group in the ring structure, demonstrated a greater antiviral efficacy. Its EC90 value was significantly improved over that of OSL-95II. Since the tertiary hydroxyl group in the ring structure is considered to be prone to dehydroxylation under acid or base conditions, perhaps this improvement is the consequence of stabilization of the active component in cells.

Changes to terminal ring structure on alkyl side chain.

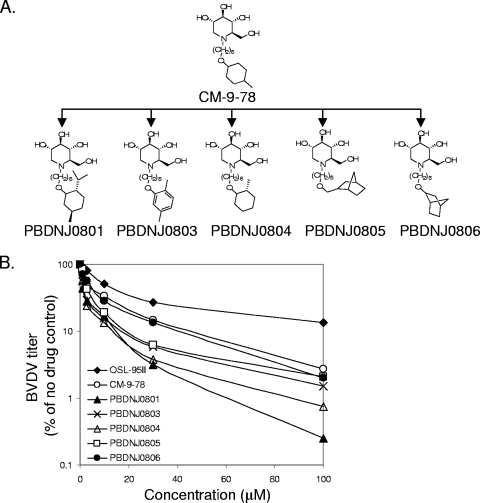

In order to further improve antiviral activity, the influence of the constituents and/or of aromatization of the terminal ring structure on antiviral efficacy and cytotoxicity were explored. PBDNJ0801 and PBDNJ0804 represent compounds with an alkyl substitution on the cyclohexyl ring. In PBDNJ0803, the cyclohexyl ring was replaced with the 2,5-dimethylphenyl aromatic group. PBDNJ0805 and PBDNJ0806 differ in the position of the oxygen atom at the alkyl side chain while employing a conformational restriction strategy with a bridged cyclohexyl group at the terminal ring. These compounds were synthesized by reductive amination of DNJ with corresponding aldehydes in the presence of H2 and Pd/C.

As shown in Fig. 2 and Table 1, all of these compounds appeared to be more potent than CM-9-78. In the BVDV yield reduction assay, their EC50 and EC90 values ranged from 1.6 to 4.5 μM and 14 to 47 μM, respectively. At a 100 μM concentration, treatment with these compounds reduced BVDV titers by at least 1 log more than treatment with OSL-95II or CM-9-78 used at the same concentration. The CC50 values of most compounds were equal to or greater than 500 μM, resulting in selectivity indices (SI, the ratio of CC50 over EC50) of at least 146. Interestingly, although PBDNJ0801 showed cytotoxicity (CC50 of 235 μM) similar to that of NNDNJ (CC50 of 245 μM), it is a more potent antiviral agent against BVDV.

FIG. 2.

Structures and antiviral effects of CM-9-78 and its derivatives. (A) Structures of CM-9-78 and its derivatives with modifications of the terminal ring. (B) Antiviral activities of CM-9-78 and its derivatives. BVDV infection was performed as described in the legend of Fig. 1. Infected cells were treated with the desired compounds at the indicated concentrations. Virus titers in the supernatant were assayed by plaque assay, and the results were plotted as percentage of results for untreated control. Each curve represents average values from at least three independent experiments.

Taken together, these data show that imino sugar derivatives containing an oxygenated side chain and a terminally restricted ring structure displayed more-potent antiviral activity against BVDV infection and reduced cytotoxicity.

The novel imino sugar derivatives are α-glucosidase inhibitors.

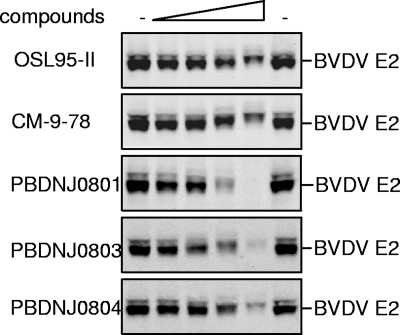

The effects of imino sugars on α-glucosidases are usually measured either by in vitro enzymatic activity assay or cell-based assay (7, 8, 25). Inside the cells, one consistent consequence of the inhibition of ER glucosidases is that nascent glycoproteins are produced that contain unprocessed glycans and thus are slightly larger (∼1,000 Da per N-glycan) than the fully processed glycoform. In cell-based assays, this characteristic property, which reduces the electrophoretic mobility rate of glycoproteins, has generally been considered an indication of glucosidase inhibition. We and others have shown, for example, that BVDV E2 glycoprotein with a reduced electrophoretic mobility is produced in cells in which glucosidase has been inhibited (17, 30, 34).

To analyze the intracellular BVDV E2 protein, proteins from MDBK cells infected with BVDV and treated with imino sugar derivatives were separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and examined by Western blotting using antibody against E2. As shown in Fig. 3, consistent with our previous report, treatment with OSL-95II, a known glucosidase inhibitor (as measured by an in vitro enzymatic assay using purified α-glucosidase [1; T. Block, unpublished data]), reduced the mobility rate of E2 protein in a dose-dependent manner. A similar change was also observed for treatment with CM-9-78, as well as its derivatives PBDNJ0801, PBDNJ0803, and PBDNJ0804.

FIG. 3.

Effects of the novel imino sugars on the mobility of BVDV E2 protein in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. MDBK cells were infected with BVDV at an MOI of 1 for 1 h and mock treated (first and sixth lanes) or treated with OSL-95II, CM-9-78, PBDNJ0801, PBDNJ0803, or PBDNJ0804 at concentrations of 3, 10, 30, and 100 μM (second to fifth lanes). Cells were harvested at 24 h postinfection, and aliquots of cell lysates were analyzed by electrophoresis followed by Western blotting to detect BVDV E2 glycoprotein.

In addition, it is proposed that sequential removal of the three glucose moieties in the glycan of a nascent glycoprotein by α-glucosidases is essential for some glycoproteins to interact with the ER chaperone calnexin, a process that is required for the proper folding of the nascent glycoproteins. Failure to interact with calnexin will lead to proteasome-dependent degradation of these glycoproteins (3, 29). Figure 3 shows that the steady-state levels of BVDV E2 proteins were significantly reduced in the presence of the imino sugar treatment. This reduction is consistent with the degradation of the glycoprotein that results from the inhibition by the compounds of the glucosidase-catalyzed glycoprotein processing and the consequent failure of the nascent E2 glycoprotein to interact with calnexin.

Taken together, the data shown in Fig. 3 suggest that, like OSL-95II, CM-9-78 and its derivatives are likely to be glucosidase inhibitors.

OSL-95II and CM-9-78 inhibit virion production of BVDV.

Glucosidase inhibitors are expected to inhibit virion particle assembly and/or secretion but not affect the early steps of virus infection and viral protein and RNA biosynthesis. To determine if this is the case for the novel glucosidase inhibitors, the steps that are inhibited by the imino sugars in the BVDV replication cycle were determined.

At first, we examined the effects of OSL-95II and CM-9-78 on intracellular BVDV RNA replication. BVDV-infected MDBK cells were treated with 100 μM of OSL-95II or 80 μM of CM-9-78 and harvested at different times after infection. The intracellular viral RNA levels were determined by real-time RT-PCR assay. As shown in Fig. 4A, the levels of viral RNA did not differ between the cells that were mock treated or treated with either of the imino sugars at 6 and 12 h after infection. However, at 24 h after infection, both compounds reduced intracellular BVDV RNA by ∼40%. This result suggests that the imino sugars did not inhibit viral RNA replication but, rather, the late reduction of viral RNA levels in the treated cells is due to inhibition of virion production by the compounds and consequent reduction of second-round infection.

To directly determine the effects of the novel imino sugars on virion production, the levels of intracellular viral RNA and extracellular virion-associated RNA and the virus titers in the supernatant were measured at 24 h after infection in the absence or presence of 100 μM of OSL-95II or 80 μM of CM-9-78. The results, as shown in Fig. 4B, demonstrated that while intracellular viral RNA was reduced by approximately 40%, OSL-95II and CM-9-78 treatment reduced extracellular virion-associated RNA by 73 to 75% and virus titers by 89 to 94%. These results thus imply that the two imino sugars not only inhibit virion production but also reduce the infectivity of the secreted BVDV virions. Taken together, our results are consistent with the notion that both OSL-95II and CM-9-78 inhibit BVDV infection by inhibition of cellular α-glucosidases.

Antiviral activities of novel imino sugar derivatives against DENV and WNV infections.

BVDV-infected MDBK cells have been used as a surrogate model for screening of antiviral agents against many members of the Flaviviridae family. To directly test the antiviral effects of the novel imino sugar derivatives against medically important human pathogenic flaviviruses, the antiviral effects of CM-9-78 and PBDNJ serial compounds (PBDNJ0801, PBDNJ0803, and PBDNJ0804) on DENV and WNV were examined. As shown in Table 2, while the antiviral activity of CM-9-78 against DENV infection was similar to that of OSL-95II, PBDNJ0801, PBDNJ0803, and PBDNJ0804 demonstrated dramatically increased anti-DENV activities. The EC90 values of the three PBDNJ compounds ranged from 0.2 to 0.6 μM, and the SI for all three compounds was greater than 800. However, the three PBDNJ compounds showed antiviral activities against WNV similar to that of OSL-95II. Moreover, the imino sugars were generally less effective against WNV infection than against DENV infection. The molecular basis for this discrepancy remains to be determined.

TABLE 2.

Summary of anti-DENV and anti-WNV activities and cytotoxicities of novel imino sugar derivatives

| Imino sugar | Activity against DENVb

|

CC50c | Activity against WNVb

|

CC50c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 | EC90 | EC50 | EC90 | |||

| NNDNJ | 1.1 | 3.3 | >40 | 4d | ND | 20-100d |

| OSL95-II | 4 | 8.7 | >40 | 4.5d | ND | >100d |

| CM-9-78 | 6.75 | 13 | >40 | ND | ND | ND |

| PBDNJ0801 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 80 | 4.75 | 19 | 70 |

| PBDNJ0803 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 85 | 1.5 | 20 | 75 |

| PBDNJ0804 | 0.075 | 0.6 | 65 | 3.5 | 33 | 70 |

a Values represent the means of the results of at least two independent experiments. ND, not determined.

Determined by yield reduction assay.

Determined by MTT assay. Each assay was performed simultaneously with an individual antiviral experiment.

Value is from reference 14. Range of values represents results from independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Some of the imino sugar derivatives, such as NNDNJ, are potent inhibitors of α-glucosidases in the ER and display broad-spectrum antiviral activity against many types of enveloped viruses, including those of significant human health concern, such as HIV, HCV, DENV, and WNV. One of the obvious advantages of glucosidase inhibitors as antiviral agents is that host cellular enzymes essential for virion assembly and/or secretion are targeted and, thus, selection of drug-resistant variants will be less likely to occur (15, 19). However, the development of imino sugar derivatives as antiviral agents has been limited by their low antiviral efficacy, as well as poor toxicity profiles. For example, NBDNJ, which is a DNJ with a 4-carbon nitrogen-linked side chain, was evaluated in a phase II clinical trial against HIV infection and was found to be unable to reach a sufficient antiviral serum concentration (12). Therefore, it is important to improve the potency of the compounds in order to achieve therapeutic concentrations in vivo.

From a structural perspective, alkylated imino sugars contain two distinct molecular elements, the imino sugar head group, DNJ, and a nitrogen-linked alkyl side chain. While the DNJ head confers competitive α-glucosidase inhibition, the side chain determines potency and cytotoxicity (2, 13, 22). In our previous efforts to optimize the nitrogen-linked alkyl side chain structure, we had obtained a lead compound, OSL-95II, which demonstrated reduced cytotoxicity but retained antiviral activity, with an EC50 at low micromolar concentrations against BVDV, DENV, and WNV (14). In the current study, we took several approaches to further modify OSL-95II by diversifying the components and terminal structure of the N-linked side chain. We found that elimination of the hydroxyl group on the terminal ring and incorporation of an oxygen atom in the side chain of OSL-95II resulted in novel group of compounds, represented by CM-9-78, which displayed better antiviral potency and reduced cytotoxicity (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Further modifications in the terminal ring structure yielded a class of PBDNJ compounds which demonstrated dramatically improved antiviral efficacy against BVDV and DENV but retained the low cytotoxicity (Fig. 2 and Table 2). Specifically, in BVDV tests, we observed that a metasubstituted analog (PBDNJ0804, EC50 = 3.3 μM) displayed better antiviral efficacy than the parasubstituted compound (CM-9-78, EC50 = 7.1 μM). However, switching the position of the oxygen atom in the alkyl side chain did not affect the antiviral activity (PBDNJ0805, EC50 = 2.9 μM, versus PBDNJ0806, EC50 = 4.5 μM). Moreover, replacing the cyclohexyl ring (CM-9-78, EC50 = 7.1 μM) with an aromatic group (PBDNJ0803, EC50 = 3.0 μM) improved the antiviral potency of the parent compound. Taken together, these structure-activity relationship studies indicate that the combination of an oxygenated alkyl side chain with a substituted terminal ring structure (cycloalkyl or aromatic) is critical for the improved antiviral activity and low cytotoxicity of the alkylated imino sugars.

Thus far, it is not clear whether the improved antiviral efficacy of the imino sugar derivatives described above is due to the increased inhibitory potency of the compounds on α-glucosidases or because the modified side chain facilitated the uptake of the compound by cells and/or accumulation in the ER. However, based on the observation that the addition of bulky groups to the cyclohexyl ring improved the potency of the compound (PBDNJ0801, PBDNJ0805, and PBDNJ0806 versus CM-9-78), it is likely that the modification improves the cellular uptake of the imino sugars.

Although it is generally believed that alkylated imino sugar derivatives inhibit virus infections by inhibition of cellular α-glucosidases, this is actually not always the case. Several recent studies indicated that DNJ derivatives with long alkylated side chains might possess distinct antiviral mechanisms other than inhibition of α-glucosidase. One example is N-nonyl-deoxygalactonojirimycin, which is not able to inhibit the ER α-glucosidases but displays an anti-BVDV activity similar to that of NNDNJ (10). In addition, it was reported recently that some DNJ derivatives not only compromise virion production but also inhibit virus entry steps during BVDV and HCV infection (28, 32). Our results presented in Fig. 3 clearly demonstrate that, like the lead compound, OSL-95II, the novel imino sugar derivatives are likely to be α-glucosidase inhibitors. In addition, the results obtained from mapping the viral replication steps targeted by the imino sugars are consistent with the hypothesis that the novel imino sugars inhibit BVDV infection by inhibition of the cellular ER α-glucosidase activity.

DENV and WNV are mosquito-borne flaviviruses that cause lethal hemorrhagic fever and invasive neurological diseases, respectively, in people (21). These viruses are of bioterror concern and are listed as select agents (18). Since 1999, WNV has spread throughout the continental United States, and it recently reached South America (20, 24). DENV has spread throughout the tropical and subtropical world, with an estimated 50 to 100 million infections and tens of millions of cases occurring annually (21). Thus far, effective antiviral therapies and vaccines are not available to treat or prevent WNV and DENV infections. Although WNV and DENV infections display distinct clinical presentations, virus replication and spreading are the key driving forces for pathogenesis. Therefore, treatment with glucosidase inhibitors to inhibit virus production and prevent the virus from spreading will be of value for infections of both viruses. In this report, we demonstrated that the novel imino sugars are active against both WNV and DENV infection in cell culture. In particular, PBDNJ0801, PBDNJ0803, and PBDNJ0804 displayed robust antiviral effects against DENV infection and thus are potential candidates for the development of antiviral drugs against human DENV infections. The pharmacokinetics and antiviral efficacies of these compounds are currently under evaluation in a DENV-infected-mouse model in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank Pamela Norton and Andrea Cuconati for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by an NIH grant (AI061441) and by the Hepatitis B Foundation through an appropriation from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 17 February 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersson, U., G. Reinkensmeier, T. D. Butters, R. A. Dwek, and F. M. Platt. 2004. Inhibition of glycogen breakdown by imino sugars in vitro and in vivo. Biochem. Pharmacol. 67:697-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhudevi, B., and D. Weinstock. 2001. Fluorogenic RT-PCR assay (TaqMan) for detection and classification of bovine viral diarrhea virus. Vet. Microbiol. 83:1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Block, T. M., and R. Jordan. 2001. Iminosugars as possible broad spectrum anti hepatitis virus agents: the glucovirs and alkovirs. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 12:317-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Block, T. M., X. Lu, A. S. Mehta, B. S. Blumberg, B. Tennant, M. Ebling, B. Korba, D. M. Lansky, G. S. Jacob, and R. A. Dwek. 1998. Treatment of chronic hepadnavirus infection in a woodchuck animal model with an inhibitor of protein folding and trafficking. Nat. Med. 4:610-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Block, T. M., X. Lu, F. M. Platt, G. R. Foster, W. H. Gerlich, B. S. Blumberg, and R. A. Dwek. 1994. Secretion of human hepatitis B virus is inhibited by the imino sugar N-butyldeoxynojirimycin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:2235-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bridges, C. G., S. P. Ahmed, M. S. Kang, R. J. Nash, E. A. Porter, and A. S. Tyms. 1995. The effect of oral treatment with 6-O-butanoyl castanospermine (MDL 28,574) in the murine zosteriform model of HSV-1 infection. Glycobiology 5:249-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butters, T. D., R. A. Dwek, and F. M. Platt. 2000. Inhibition of glycosphingolipid biosynthesis: application to lysosomal storage disorders. Chem. Rev. 100:4683-4696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chapman, T. M., I. G. Davies, B. Gu, T. M. Block, D. I. Scopes, P. A. Hay, S. M. Courtney, L. A. McNeill, C. J. Schofield, and B. G. Davis. 2005. Glyco- and peptidomimetics from three-component Joullie-Ugi coupling show selective antiviral activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127:506-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Datema, R., P. A. Romero, R. Rott, and R. T. Schwarz. 1984. On the role of oligosaccharide trimming in the maturation of Sindbis and influenza virus. Arch. Virol. 81:25-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Durantel, D., N. Branza-Nichita, S. Carrouee-Durantel, T. D. Butters, R. A. Dwek, and N. Zitzmann. 2001. Study of the mechanism of antiviral action of iminosugar derivatives against bovine viral diarrhea virus. J. Virol. 75:8987-8998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dwek, R. A., T. D. Butters, F. M. Platt, and N. Zitzmann. 2002. Targeting glycosylation as a therapeutic approach. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 1:65-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischl, M. A., L. Resnick, R. Coombs, A. B. Kremer, J. C. Pottage, Jr., R. J. Fass, K. H. Fife, W. G. Powderly, A. C. Collier, R. L. Aspinall, et al. 1994. The safety and efficacy of combination N-butyl-deoxynojirimycin (SC-48334) and zidovudine in patients with HIV-1 infection and 200-500 CD4 cells/mm3. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 7:139-147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gentry, M. K., E. A. Henchal, J. M. McCown, W. E. Brandt, and J. M. Dalrymple. 1982. Identification of distinct antigenic determinants on dengue-2 virus using monoclonal antibodies. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 31:548-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gu, B., P. Mason, L. Wang, P. Norton, N. Bourne, R. Moriarty, A. Mehta, M. Despande, R. Shah, and T. Block. 2007. Antiviral profiles of novel iminocyclitol compounds against bovine viral diarrhea virus, West Nile virus, dengue virus and hepatitis B virus. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 18:49-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hammer, S. M., J. J. Eron, Jr., P. Reiss, R. T. Schooley, M. A. Thompson, S. Walmsley, P. Cahn, M. A. Fischl, J. M. Gatell, M. S. Hirsch, D. M. Jacobsen, J. S. Montaner, D. D. Richman, P. G. Yeni, and P. A. Volberding. 2008. Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection: 2008 recommendations of the International AIDS Society—USA panel. JAMA 300:555-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helenius, A., and M. Aebi. 2004. Roles of N-linked glycans in the endoplasmic reticulum. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73:1019-1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jordan, R., O. V. Nikolaeva, L. Wang, B. Conyers, A. Mehta, R. A. Dwek, and T. M. Block. 2002. Inhibition of host ER glucosidase activity prevents Golgi processing of virion-associated bovine viral diarrhea virus E2 glycoproteins and reduces infectivity of secreted virions. Virology 295:10-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.King, N. J., D. R. Getts, M. T. Getts, S. Rana, B. Shrestha, and A. M. Kesson. 2007. Immunopathology of flavivirus infections. Immunol. Cell Biol. 85:33-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koev, G., and W. Kati. 2008. The emerging field of HCV drug resistance. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 17:303-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lanciotti, R. S., J. T. Roehrig, V. Deubel, J. Smith, M. Parker, K. Steele, B. Crise, K. E. Volpe, M. B. Crabtree, J. H. Scherret, R. A. Hall, J. S. MacKenzie, C. B. Cropp, B. Panigrahy, E. Ostlund, B. Schmitt, M. Malkinson, C. Banet, J. Weissman, N. Komar, H. M. Savage, W. Stone, T. McNamara, and D. J. Gubler. 1999. Origin of the West Nile virus responsible for an outbreak of encephalitis in the northeastern United States. Science 286:2333-2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mackenzie, J. S., D. J. Gubler, and L. R. Petersen. 2004. Emerging flaviviruses: the spread and resurgence of Japanese encephalitis, West Nile and dengue viruses. Nat. Med. 10:S98-S109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malvoisin, E., and F. Wild. 1994. The role of N-glycosylation in cell fusion induced by a vaccinia recombinant virus expressing both measles virus glycoproteins. Virology 200:11-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mehta, A., S. Ouzounov, R. Jordan, E. Simsek, X. Lu, R. M. Moriarty, G. Jacob, R. A. Dwek, and T. M. Block. 2002. Imino sugars that are less toxic but more potent as antivirals, in vitro, compared with N-n-nonyl DNJ. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 13:299-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morales, M. A., M. Barrandeguy, C. Fabbri, J. B. Garcia, A. Vissani, K. Trono, G. Gutierrez, S. Pigretti, H. Menchaca, N. Garrido, N. Taylor, F. Fernandez, S. Levis, and D. Enria. 2006. West Nile virus isolation from equines in Argentina, 2006. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12:1559-1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Norton, P. A., B. Conyers, Q. Gong, L. F. Steel, T. M. Block, and A. S. Mehta. 2005. Assays for glucosidase inhibitors with potential antiviral activities: secreted alkaline phosphatase as a surrogate marker. J. Virol. Methods 124:167-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Repp, R., T. Tamura, C. B. Boschek, H. Wege, R. T. Schwarz, and H. Niemann. 1985. The effects of processing inhibitors of N-linked oligosaccharides on the intracellular migration of glycoprotein E2 of mouse hepatitis virus and the maturation of coronavirus particles. J. Biol. Chem. 260:15873-15879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rossi, S. L., Q. Zhao, V. K. O'Donnell, and P. W. Mason. 2005. Adaptation of West Nile virus replicons to cells in culture and use of replicon-bearing cells to probe antiviral action. Virology 331:457-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schul, W., W. Liu, H. Y. Xu, M. Flamand, and S. G. Vasudevan. 2007. A dengue fever viremia model in mice shows reduction in viral replication and suppression of the inflammatory response after treatment with antiviral drugs. J. Infect. Dis. 195:665-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simsek, E., G. Sinnathamby, T. M. Block, Y. Liu, R. Philip, A. S. Mehta, and P. A. Norton. 2009. Inhibition of cellular alpha-glucosidases results in increased presentation of hepatitis B virus glycoprotein-derived peptides by MHC class I. Virology 384:12-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steinmann, E., T. Whitfield, S. Kallis, R. A. Dwek, N. Zitzmann, T. Pietschmann, and R. Bartenschlager. 2007. Antiviral effects of amantadine and iminosugar derivatives against hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 46:330-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor, D. L., P. S. Sunkara, P. S. Liu, M. S. Kang, T. L. Bowlin, and A. S. Tyms. 1991. 6-0-butanoylcastanospermine (MDL 28,574) inhibits glycoprotein processing and the growth of HIVs. AIDS 5:693-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whitby, K., T. C. Pierson, B. Geiss, K. Lane, M. Engle, Y. Zhou, R. W. Doms, and M. S. Diamond. 2005. Castanospermine, a potent inhibitor of dengue virus infection in vitro and in vivo. J. Virol. 79:8698-8706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu, S. F., C. J. Lee, C. L. Liao, R. A. Dwek, N. Zitzmann, and Y. L. Lin. 2002. Antiviral effects of an iminosugar derivative on flavivirus infections. J. Virol. 76:3596-3604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zitzmann, N., A. S. Mehta, S. Carrouee, T. D. Butters, F. M. Platt, J. McCauley, B. S. Blumberg, R. A. Dwek, and T. M. Block. 1999. Imino sugars inhibit the formation and secretion of bovine viral diarrhea virus, a pestivirus model of hepatitis C virus: implications for the development of broad spectrum anti-hepatitis virus agents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:11878-11882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]