Abstract

For a panel of 153 Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates (including 13 vancomycin-intermediate or heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate and 4 vancomycin-resistant strains), MIC50s and MIC90s of three novel dihydrophthalazine antifolates, BAL0030543, BAL0030544, and BAL0030545, were 0.03 and 0.25 μg/ml, respectively, for methicillin-susceptible strains and 0.03 and ≤0.25 μg/ml, respectively, for methicillin-resistant strains. For a panel of 160 coagulase-negative staphylococci (including 5 vancomycin-intermediate and heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate strains and 7 linezolid-nonsusceptible strains), MIC50s and MIC90s were ≤0.03 and ≤0.06 μg/ml, respectively, for methicillin-susceptible strains and 0.06 and 0.5 μg/ml, respectively, for methicillin-resistant strains. Vancomycin was active against 93.0% of 313 staphylococci examined; linezolid was active against all S. aureus strains and 95.6% of coagulase-negative staphylococcus strains, whereas elevated MICs of clindamycin, minocycline, trimethoprim, and rifampin for some strains were observed. At 4× MIC, the dihydrophthalazines were bactericidal against 11 of 12 staphylococcal strains surveyed. The prolonged serial passage of some staphylococcal strains in the presence of subinhibitory concentrations of BAL0030543, BAL0030544, and BAL0030545 produced clones for which dihydrophthalazines showed high MICs (>128 μg/ml), although rates of endogenous resistance development were much lower for the dihydrophthalazines than for trimethoprim. Single-step platings of naïve staphylococci onto media containing dihydrophthalazine antifolates indicated considerable variability among strains with respect to preexistent subpopulations nonsusceptible to dihydrophthalazine antifolates.

The prevalence of multidrug-resistant staphylococci (2, 18) and the emergence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) as a prominent cause of community-acquired skin and skin structure infections (28) are of concern to the medical community. Infections caused by coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS), once considered rare, are becoming increasingly frequent, particularly in patients with indwelling medical devices and those who are immunocompromised, and such infections are associated with significant morbidity and mortality (40). The adhesion of Staphylococcus epidermidis to endothelial cells is enhanced at temperatures encountered during a moderate fever (27), and the internalization of CoNS by host cells (1, 7, 27) probably contributes to antibiotic failure and infection persistence in some patients. Glycopeptides, especially vancomycin, are the current standard of care for the empirical treatment of suspected methicillin-resistant staphylococcal infections, but staphylococci with reduced susceptibility, tolerance, or resistance to vancomycin have appeared in clinical settings (2, 15, 19, 33), and their frequency is almost certainly underreported due to problems with identification and confusion over breakpoints (2, 39).

The spread of multidrug-resistant staphylococci mandates the development of novel therapeutic modalities. Of the antistaphylococcal drugs marketed during the past decade, only linezolid has therapeutically useful oral bioavailability; however, this oxazolidinone has been associated with serious toxicity (particularly during prolonged use), is not bactericidal toward staphylococci, and may support the emergence of endogenous resistance during long-term treatment (4, 16, 24, 26, 32, 34). Most staphylococci, particularly those isolated outside health care settings, remain susceptible to sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (38), though surely this will change as sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim is used with increasing frequency to treat MRSA infections. Thus, an urgent need remains for new orally available compounds with activity against drug-resistant staphylococci and safety profiles compatible with long-term treatment.

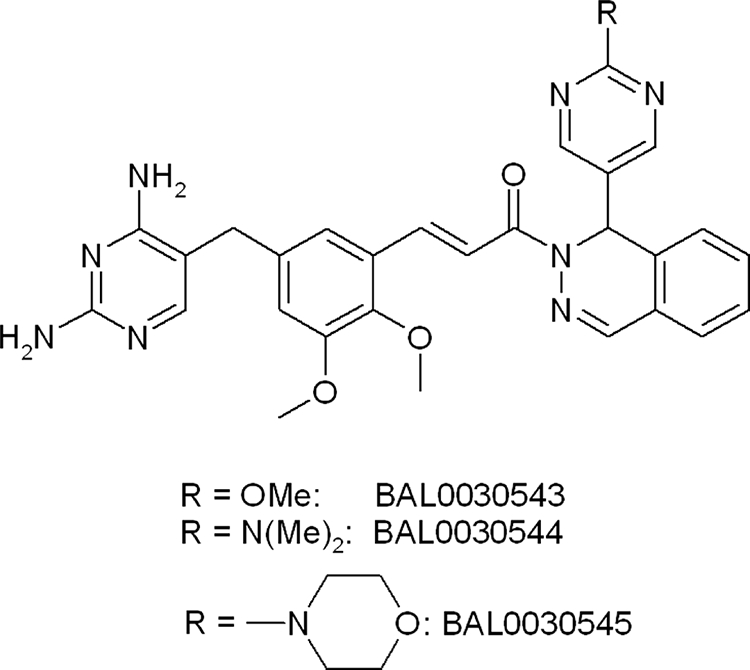

Dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) is an essential enzyme in most pathogenic bacteria, and the clinical success of trimethoprim has demonstrated that DHFR is an important chemotherapeutic target (41). BAL0030543, BAL0030544, and BAL0030545 (Fig. 1) are novel dihydrophthalazine derivatives of 2,4-diaminopyrimidine with potent activities against gram-positive pathogens, including staphylococci. The present study sought to determine (i) the MICs of BAL0030543, BAL0030544, BAL0030545, and comparators for 313 staphylococci, (ii) the bacteriostatic or bactericidal activities of the dihydrophthalazine antifolates and comparators against a dozen selected staphylococcal strains, (iii) the proclivity of the dihydrophthalazines and some comparators to select for endogenous resistance among 10 staphylococci with diverse resistotypes, and (iv) the frequency of preexistent resistance to the dihydrophthalazines in naïve populations of staphylococci.

FIG. 1.

Structures of dihydrophthalazine antifolates BAL0030543, BAL0030544, and BAL0030545. Me, methyl.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria.

The complete strain panel (313 strains) comprised 127 MRSA, 26 methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA), 135 methicillin-resistant CoNS (MRCoNS), and 25 methicillin-susceptible CoNS (MSCoNS) strains and included 2 Michigan vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA), 1 New York VRSA, 1 Pennsylvania (Hershey) VRSA, 10 vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA), 3 heterogeneous VISA (hVISA), 4 vancomycin-intermediate CoNS (VICoNS), 1 heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate CoNS (hVICoNS), and 7 linezolid-nonsusceptible (LzdNS) CoNS strains. All VRSA strains and vancomycin-intermediate staphylococci not isolated at the Hershey Medical Center were obtained from the Network on Antimicrobial Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus through the agency of Eurofins Medinet, Inc. (Chantilly, VA). Most of the strains studied were isolated from patients during the past 8 years.

VISA and VICoNS strains were identified using Etest strips (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden), whereas hVISA and hVICoNS strains were identified by the macro Etest method (9), and the results were confirmed by population analyses. Where necessary, CoNS species were identified using API Staph galleries [bioMérieux (Suisse) SA, Geneva, Switzerland].

Antimicrobial agents and MIC testing.

BAL0030543, BAL0030544, and BAL0030545, products of Basilea Pharmaceutica International AG (Basel, Switzerland), were prepared by the method of Guerry et al. (P. Guerry, S. Jolidon, R. Masciadri, H. Stalder, and R. Then, 30 May 1996, Switzerland international patent application WO 96/16046); other antimicrobial agents (clindamycin, linezolid, minocycline, rifampin, trimethoprim, and vancomycin) were obtained from commercial sources. With the exception of vancomycin, all of the comparators are used as oral monotherapies or as an oral component of combination therapy for the treatment of infections attributed to methicillin-resistant staphylococci (22, 30).

Agar dilution MICs were determined using Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA; Oxoid product no. CM0337) according to CLSI guidelines (12). S. aureus ATCC 29213 and Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 were included with each set of MIC determinations; MICs for test strains were recorded only if MICs for quality control strains were within acceptable ranges (13). Vancomycin MICs were read after a full 24 h of incubation (13).

Time-kill studies.

Time-kill profiles were obtained for six S. aureus strains (two MSSA and four MRSA strains) and six CoNS (two MSCoNS and four MRCoNS) (see Table 2) at drug concentrations of 1×, 2×, and 4× MIC. Glass tubes containing 5 ml of Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB; Oxoid product no. CM0405) with final inocula of 5 × 105 to 5 × 106 CFU/ml were incubated at 35°C in a water bath with shaking. Viable cells were quantified at 0, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h by spread plating 0.1-ml aliquots of 10-fold dilutions (in MHB) from each tube onto Trypticase soy agar-5% (vol/vol) defbrinated sheep blood (BBL) and incubating the plates for 24 to 48 h in ambient air at 35°C.

TABLE 2.

MICs for strains tested by time-kill studies

| Straina | MIC (μg/ml) of:

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAL0030543 | BAL0030544 | BAL0030545 | Trimethoprim | Vancomycin | Linezolid | Clindamycin | Minocycline | Rifampin | |

| S. aureus ATCC 29213* | 0.03 | 0.125 | 0.06 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.016 |

| SA505* | 0.03 | 0.125 | 0.03 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.03 |

| S. aureus ATCC 43300 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 1 | 1 | 2 | >256 | 0.125 | 0.016 |

| SA145 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | >128 | 1 | 4 | >512 | 4 | 0.008 |

| SA507 | 0.06 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 128 | 4 | 2 | 512 | 2 | 4 |

| VRS1b | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | >128 | >256 | 2 | >512 | 1 | >128 |

| CN051* | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 128 | 2 | 2 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.016 |

| CN057* | 8 | 4 | 4 | 128 | 2 | 2 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.03 |

| CN074 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.03 |

| CN197 | 0.008 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 2 | 2 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.03 |

| CN225 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.25 | >128 | 8 | 2 | >128 | 0.125 | 0.03 |

| CN345 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.125 | >128 | 2 | 64 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.016 |

Designations beginning with SA indicate S. aureus strains, and designations beginning with CN indicate (coagulase-negative) S. epidermidis strains. Methicillin-susceptible strains are marked with an asterisk; all other strains are methicillin resistant.

Michigan VRSA strain.

A given concentration of antimicrobial (expressed as a multiple of the MIC) was considered bactericidal if it reduced the inoculum size by ≥3 log10 CFU/ml within 24 h or bacteriostatic if the inoculum size was reduced by <3 log10 CFU/ml during the same period. With the sensitivity threshold and inocula employed, no problems in delineating 99.9% killing were encountered. Issues of antibiotic carryover were addressed by dilution, as described previously (31). Due to innate resistance by some strains to particular antibiotics, time-kill profiles were not obtained for seven strains with trimethoprim, five strains with clindamycin, and one strain each with linezolid, rifampin, and vancomycin.

Multipassage resistance selection studies.

Five S. aureus (three MRSA, one VISA, one VRSA, and two Tmpr) strains and five S. epidermidis (three methicillin-resistant, one vancomycin-intermediate, one LzdNS, and four Tmpr) strains were subjected to serial passage in the presence of subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotics. Initial inocula (∼1 × 106 CFU/ml) were prepared by suspending growth from an overnight MHA plate (BBL) in MHB (Oxoid). Glass tubes containing 1 ml of antibiotic-free or antibiotic-supplemented MHB were inoculated and incubated at 35°C for 24 h; antibiotic concentrations in the tubes ranged from 4 log2 steps above to 3 log2 steps below the MIC of each drug for each strain. Cultures were passaged daily for up to 50 days by using 10-μl inocula from the tubes with concentrations nearest the MIC (1 to 2 dilutions below the MIC) which had the same turbidity as antibiotic-free controls. Aliquots of inoculum were frozen at −70°C in double-strength skim milk. After 50 passages or when the MIC for a strain stabilized at >128 μg/ml during four successive passages, serial transfer in the presence of subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotic was discontinued and selected strains were subjected to 10 passages in antibiotic-free medium.

To confirm that resistant isolates obtained at the end of serial passaging derived from the parental strains, parental strains and clones obtained after the final passage were examined by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis using a CHEF-DR III apparatus (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) as described previously (25).

Chromosomal and plasmid DHFR genes from parental strains and from clones emerging during serial passage for which any of the dihydrophthalazine derivatives had elevated MICs were amplified and sequenced as described previously (10, 14). DHFR genes from clones for which the MICs of antifolates changed significantly during subsequent passage on antibiotic-free medium were also sequenced.

Single-step resistance selection studies.

Bacterial cells were scraped from overnight plates, washed once with MHB (Oxoid), and resuspended in MHB at a final concentration of 1010 to 1011 CFU/ml. An aliquot (50 μl) of the bacterial suspension was spread onto MHA (Oxoid) containing the same antibiotics used for multipassage resistance selection at two, four, and eight times the agar dilution MIC. Plates were incubated aerobically at 35°C for 48 h. Randomly selected colonies growing on antibiotic-containing media were retested by agar dilution. Resistance in single-step studies was defined by an MIC ≥4 times higher than that for the parent strain. The resistance frequency at each MIC for each strain-antibiotic pair was calculated as the number of resistant colonies per inoculum (37).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The dihydrophthalazine antifolates BAL0030543, BAL0030544, and BAL0030545 were identified at Basilea Pharmaceutica International AG as novel DHFR inhibitors with very encouraging in vitro antibacterial activities (36). The present study focused on the antistaphylococcal properties of the dihydrophthalazines toward a panel comprising predominantly recent clinical isolates, including vancomycin-intermediate and -resistant and LzdNS strains, as well as an abundance of methicillin-resistant strains.

MICs of BAL0030543, BAL0030544, BAL0030545, and comparators are summarized in Table 1. Among 153 S. aureus strains (including 10 VISA, 3 hVISA, and 4 VRSA strains), MIC90s of the dihydrophthalazine derivatives were 0.25 and 0.125 to 0.25 μg/ml for MSSA and MRSA, respectively, and 0.03 to 0.06 and 0.5 μg/ml for Tmps and Tmpr strains, respectively. Among 160 CoNS strains (including 4 VICoNS strains and 1 hVICoNS strain), MIC90s were 0.03 to 0.06 and 0.5 μg/ml for MSCoNS and MRCoNS, respectively, and 0.03 to 0.06 μg/ml and 0.5 to 1 μg/ml, respectively, for Tmps and Tmpr strains, respectively. MIC90s of trimethoprim for the S. aureus and CoNS panels were >128 μg/ml. Vancomycin was active against all 313 staphylococci surveyed except the 22 strains (7.0%) for which MICs of this glycopeptide are known to be compromised. Linezolid was active against all S. aureus strains and 153 (95.6%) of 160 CoNS strains examined. All MSCoNS strains were susceptible to clindamycin, and all methicillin-susceptible staphylococci were susceptible to minocycline and rifampin (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Summary of MICs for staphylococcal strains

| Organism | Drug | MIC (μg/ml) for strainsa with phenotype:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methicillin susceptible

|

Methicillin resistant

|

Tmps

|

Tmpr

|

||||||

| Range | 50%/90% | Range | 50%/90% | Range | 50%/90% | Range | 50%/90% | ||

| S. aureus | BAL0030543 | 0.016->32 | 0.03/0.25 | ≤0.008->32 | 0.03/0.25 | ≤0.008-0.125 | 0.03/0.03 | 0.06->32 | 0.25/0.5 |

| BAL0030544 | ≤0.008->32 | 0.03/0.25 | ≤0.008->32 | 0.03/0.125 | ≤0.008-0.06 | 0.03/0.03 | 0.03->32 | 0.25/0.5 | |

| BAL0030545 | ≤0.008->32 | 0.03/0.25 | ≤0.008->32 | 0.03/0.25 | ≤0.008-0.125 | 0.03/0.06 | 0.03->32 | 0.25/0.5 | |

| Trimethoprim | 0.25->128 | 0.5/>128 | ≤0.008->128 | 0.5/>128 | ≤0.008-2 | 0.5/0.5 | 32->128 | >128/>128 | |

| Vancomycin | 0.5-8 | 1/2 | 0.5->32 | 1/2 | 0.5->32 | 1/2 | 0.5->32 | 1/4 | |

| Linezolid | 1-2 | 2/2 | 0.25-2 | 2/2 | 0.25-2 | 2/2 | 1-2 | 1/2 | |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.06->32 | 0.125/>32 | ≤0.06->32 | >32/>32 | ≤0.06->32 | >32/>32 | ≤0.06->32 | >32/>32 | |

| Minocycline | 0.016-2 | 0.125/0.25 | 0.03-16 | 0.125/2 | 0.03-16 | 0.125/0.25 | 0.016-8 | 0.25/8 | |

| Rifampin | ≤0.004-0.03 | 0.008/0.016 | ≤0.004->16 | 0.016/0.016 | ≤0.004->16 | 0.016/0.016 | ≤0.004->16 | 0.008/>16 | |

| CoNS | BAL0030543 | ≤0.008-2 | 0.016/0.06 | ≤0.008->32 | 0.06/0.5 | ≤0.008-0.125 | 0.016/0.03 | 0.016->32 | 0.125/0.5 |

| BAL0030544 | ≤0.008-2 | 0.016/0.03 | ≤0.008->32 | 0.06/0.5 | ≤0.008-0.125 | 0.016/0.03 | 0.016->32 | 0.125/0.5 | |

| BAL0030545 | ≤0.008-4 | 0.03/0.06 | ≤0.008->32 | 0.06/0.5 | ≤0.008-0.125 | 0.03/0.06 | 0.03->32 | 0.125/1 | |

| Trimethoprim | 0.06-128 | 0.25/64 | 0.03->128 | 128/>128 | 0.03-4 | 0.25/2 | 16->128 | >128/>128 | |

| Vancomycin | 0.5-2 | 1/2 | 0.5-8 | 2/2 | 0.5-2 | 1/2 | 1-8 | 2/2 | |

| Linezolid | 1-2 | 1/2 | 1->16 | 1/2 | 1-2 | 1/2 | 1->16 | 1/2 | |

| Clindamycin | 0.125 | 0.125/0.125 | ≤0.06->32 | 0.25/>32 | ≤0.06->32 | 0.125/>32 | 0.125->32 | 2/>32 | |

| Minocycline | 0.125-0.5 | 0.125/0.5 | 0.06-16 | 0.25/1 | 0.06-16 | 0.125/1 | 0.06-2 | 0.5/0.5 | |

| Rifampin | ≤0.004-0.016 | ≤0.004/0.016 | ≤0.004->16 | 0.008/2 | ≤0.004->16 | 0.008/0.016 | ≤0.004->16 | 0.008/>16 | |

Numbers of strains were as follows: for S. aureus, 26 methicillin susceptible, 127 methicillin resistant, 125 Tmps, and 28 Tmpr, and for CoNS, 25 methicillin susceptible, 135 methicillin resistant, 58 Tmps, and 102 Tmpr.

Broth macrodilution MICs for the 12 staphylococcal strains examined by time-kill studies are presented in Table 2, and the time-kill profiles are summarized in Table 3. The bactericidal spectra of BAL0030543, BAL0030544, and BAL0030545 at 2× to 4× MIC encompassed 9 to 11 (75.0 to 91.7%) of the surveyed strains, whereas at 1× MIC the dihydrophthalazines were bactericidal toward only 3 to 6 (25.0 to 50.0%) of the strains. At 4× MIC, the dihydrophthalazine derivatives proved to be bactericidal against 11 of 12 staphylococcal strains; at this multiple of the MIC, BAL0030543 was bacteriostatic only toward strain CN197 [Δ(log10 CFU/ml) = −2.7] and BAL0030544 and BAL0030545 were bacteriostatic only toward strain CN057 [Δ(log10 CFU/ml) = −2.0 and −1.7, respectively]. Of the marketed antibiotics tested, trimethoprim and vancomycin had time-kill profiles resembling those of the dihydrophthalazine antifolates, though due to intrinsic resistance to trimethoprim (Table 1), a time-kill profile for this drug was obtained for only two CoNS strains and three S. aureus strains. At 4× MIC, kill rates for S. aureus during the first 6 h generally corresponded to the following order: BAL0030544, BAL0030545 > trimethoprim > BAL0030543 > vancomycin (where the comma indicates that the drugs have similar kill rates). At 4× MIC, kill rates for CoNS during the first 6 h generally corresponded to the following order: vancomycin > BAL0030543, BAL030544, BAL0030545. At 4× MIC, rifampin was bactericidal toward 5 (SA145, CN051, CN057, CN074, and CN197) of 11 strains whereas clindamycin, linezolid, and minocycline were bacteriostatic toward all strains. While MIC and time-kill data for the comparators generally accord with published values (3, 8, 23), the 6-h kill rate for trimethoprim obtained in the present study was somewhat higher than that reported by Hackbarth et al. (21).

TABLE 3.

Time-kill analyses for 12 staphylococci

| Drug (no. of strains tested) and dose | No. of strains showing indicated % of killing at:

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 h

|

6 h

|

12 h

|

24 h

|

|||||||||

| 90 | 99 | 99.9 | 90 | 99 | 99.9 | 90 | 99 | 99.9 | 90 | 99 | 99.9 | |

| BAL0030543 (12 strains) | ||||||||||||

| 4× MIC | 4 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 6 | 0 | 12 | 12 | 5 | 12 | 12 | 11 |

| 2× MIC | 4 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 6 | 0 | 12 | 12 | 4 | 12 | 12 | 11 |

| 1× MIC | 3 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 4 | 0 | 12 | 8 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 6 |

| BAL0030544 (12 strains) | ||||||||||||

| 4× MIC | 6 | 1 | 0 | 12 | 8 | 2 | 12 | 12 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 11 |

| 2× MIC | 5 | 1 | 0 | 12 | 7 | 2 | 12 | 12 | 8 | 11 | 10 | 9 |

| 1× MIC | 3 | 1 | 0 | 11 | 7 | 2 | 11 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 3 |

| BAL0030545 (12 strains) | ||||||||||||

| 4× MIC | 5 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 7 | 1 | 12 | 12 | 7 | 12 | 11 | 11 |

| 2× MIC | 3 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 8 | 2 | 12 | 12 | 6 | 11 | 11 | 10 |

| 1× MIC | 3 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 4 | 1 | 10 | 8 | 4 | 9 | 6 | 5 |

| Trimethoprim (5 strains) | ||||||||||||

| 4× MIC | 3 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| 2× MIC | 3 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 3 |

| 1× MIC | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Vancomycin (11 strains) | ||||||||||||

| 4× MIC | 6 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 6 | 3 | 10 | 9 | 4 | 11 | 10 | 10 |

| 2× MIC | 5 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 5 | 2 | 10 | 7 | 3 | 10 | 8 | 7 |

| 1× MIC | 5 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 5 | 2 | 8 | 6 | 6 |

| Linezolid (11 strains) | ||||||||||||

| 4× MIC | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 2 | 0 |

| 2× MIC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 0 |

| 1× MIC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Clindamycin (7 strains) | ||||||||||||

| 4× MIC | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 0 |

| 2× MIC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 3 | 0 |

| 1× MIC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Minocycline (12 strains) | ||||||||||||

| 4× MIC | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 2 | 0 |

| 2× MIC | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 0 |

| 1× MIC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Rifampin (11 strains) | ||||||||||||

| 4× MIC | 7 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 11 | 6 | 1 | 11 | 9 | 5 |

| 2× MIC | 5 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 5 | 1 | 10 | 8 | 2 |

| 1× MIC | 4 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 1 |

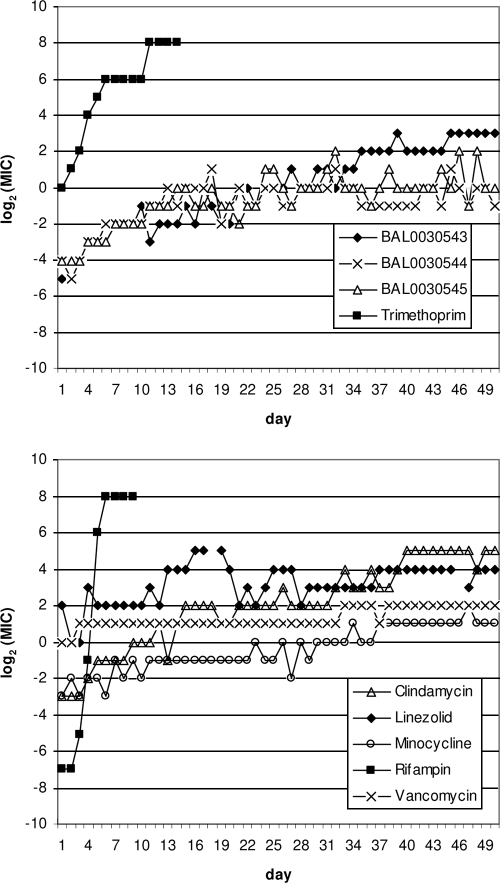

Representative resistance development profiles for dihydrophthalazine antifolates and comparators versus S. aureus ATCC 29213 are presented in Fig. 2, and the results of serial passages of selected S. aureus and S. epidermidis strains in the presence of subinhibitory antibiotic concentrations are shown in Table 4. Prolonged serial transfer in the presence of subinhibitory concentrations of BAL0030543, BAL0030544, or BAL0030545 revealed considerable strain variability in the development of endogenous resistance toward dihydrophthalazine antifolates and comparators. During ≤50 serial passages, two of five S. aureus and three of five S. epidermidis strains, including strains for which initial MICs of BAL0030543, BAL0030544, and BAL0030545 were ≤1 μg/ml, developed levels of resistance toward all three dihydrophthalazines equivalent to MICs of ≥64 μg/ml. Rates of development of endogenous resistance toward BAL0030543, BAL0030544, and BAL0030545 varied with the strain, being lowest for CN197 and highest for SA145, VRS1, and CN225. MICs of the novel antifolates tended to increase smoothly, with the notable exception of those for CN345, for which a dramatic leap (8 to >128 μg/ml) in the MIC of BAL0030544 occurred between passages 29 and 30. The results suggest that, at least for a subset of staphylococci, BAL0030545 may have less proclivity to promote endogenous resistance development than either BAL0030543 or BAL0030544.

FIG. 2.

Endogenous antibiotic resistance development during serial passage of S. aureus ATCC 29213.

TABLE 4.

Results of multipassage resistance selection by the dihydrophthalazine antifolates and comparators

| Strain (phenotype)a | Antibiotic | Initial MICb (μg/ml) | No. of passages | Final MIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus ATCC 29213 (MSSA) | BAL0030543 | 0.03 | 50 | 8 |

| BAL0030544 | 0.06 | 50 | 0.5 | |

| BAL0030545 | 0.06 | 50 | 1 | |

| Trimethoprim | 1 | 14 | >128 | |

| Linezolid | 4 | 50 | 16 | |

| Minocycline | 0.125 | 50 | 2 | |

| Clindamycin | 0.125 | 50 | 32 | |

| Vancomycin | 1 | 50 | 4 | |

| Rifampin | 0.008 | 9 | >128 | |

| SA505 (MSSA, VISA) | BAL0030543 | 0.016 | 50 | 1 |

| BAL0030544 | 0.03 | 50 | 8 | |

| BAL0030545 | 0.03 | 50 | 2 | |

| Trimethoprim | 1 | 14 | >128 | |

| Linezolid | 4 | 50 | 16 | |

| Minocycline | 0.125 | 50 | 1 | |

| Clindamycin | 0.125 | 39 | >128 | |

| Vancomycin | 4 | 50 | 8 | |

| Rifampin | 0.016 | 9 | >128 | |

| S. aureus ATCC 43300 (MRSA) | BAL0030543 | 0.03 | 50 | 4 |

| BAL0030544 | 0.03 | 50 | 1 | |

| BAL0030545 | 0.06 | 50 | 2 | |

| Trimethoprim | 1 | 20 | >128 | |

| Linezolid | 2 | 50 | 64 | |

| Minocycline | 0.125 | 50 | 1 | |

| Clindamycin | >32 | |||

| Vancomycin | 1 | 50 | 4 | |

| Rifampin | 0.004 | 9 | >128 | |

| SA145 (MRSA) | BAL0030543 | 0.5 | 37 | >128 |

| BAL0030544 | 0.25 | 47 | >128 | |

| BAL0030545 | 0.25 | 50 | 128 | |

| Trimethoprim | >128 | |||

| Linezolid | 2 | 50 | 16 | |

| Minocycline | 4 | 50 | 8 | |

| Clindamycin | >32 | |||

| Vancomycin | 1 | 50 | 2 | |

| Rifampin | 0.008 | 10 | >128 | |

| VRS1 (MRSA, VRSA-MI) | BAL0030543 | 0.5 | 15 | >128 |

| BAL0030544 | 0.25 | 20 | >128 | |

| BAL0030545 | 1 | 25 | >128 | |

| Trimethoprim | >128 | |||

| Linezolid | 2 | 50 | 32 | |

| Minocycline | 0.5 | 50 | 2 | |

| Clindamycin | >32 | |||

| Vancomycin | >32 | |||

| Rifampin | >32 | |||

| CN051 (MSSE) | BAL0030543 | 0.25 | 50 | 64 |

| BAL0030544 | 0.125 | 38 | >128 | |

| BAL0030545 | 0.5 | 50 | 64 | |

| Trimethoprim | 64 | |||

| Linezolid | 2 | 50 | 128 | |

| Minocycline | 0.125 | 50 | 4 | |

| Clindamycin | 0.125 | 50 | 4 | |

| Vancomycin | 2 | 50 | 4 | |

| Rifampin | 0.008 | 9 | >128 | |

| CN057 (MSSE) | BAL0030543 | 8 | 50 | 128 |

| BAL0030544 | 8 | 15 | >128 | |

| BAL0030545 | 8 | 23 | >128 | |

| Trimethoprim | 128 | |||

| Linezolid | 2 | 50 | 64 | |

| Minocycline | 0.5 | 50 | 2 | |

| Clindamycin | 0.125 | 10 | >128 | |

| Vancomycin | 2 | 50 | 4 | |

| Rifampin | 0.016 | 9 | >128 | |

| CN197 (MRSE) | BAL0030543 | 0.03 | 50 | 1 |

| BAL0030544 | 0.06 | 50 | 0.125 | |

| BAL0030545 | 0.06 | 50 | 1 | |

| Trimethoprim | 1 | 50 | 64 | |

| Linezolid | 2 | 50 | 32 | |

| Minocycline | 0.125 | 50 | 2 | |

| Clindamycin | 0.125 | 50 | 2 | |

| Vancomycin | 2 | 50 | 4 | |

| Rifampin | 0.008 | 12 | >128 | |

| CN225 (MRSE, VISE) | BAL0030543 | 0.25 | 50 | 128 |

| BAL0030544 | 0.25 | 38 | >128 | |

| BAL0030545 | 0.25 | 36 | >128 | |

| Trimethoprim | >128 | |||

| Linezolid | 2 | 50 | 16 | |

| Minocycline | 0.125 | 50 | 1 | |

| Clindamycin | >32 | |||

| Vancomycin | 8 | 50 | 16 | |

| Rifampin | 0.016 | 11 | >128 | |

| CN345 (MRSE, LzdNS) | BAL0030543 | 0.125 | 50 | 16 |

| BAL0030544 | 0.06 | 33 | >128 | |

| BAL0030545 | 0.06 | 50 | 4 | |

| Trimethoprim | >128 | |||

| Linezolid | 32 | 50 | 128 | |

| Minocycline | 0.5 | 50 | 1 | |

| Clindamycin | 2 | 50 | 4 | |

| Vancomycin | 2 | 50 | 4 | |

| Rifampin | 0.008 | 9 | >128 |

Designations beginning with SA indicate S. aureus strains; VRS1 is a Michigan VRSA (VRSA-MI) strain. Designations beginning with CN indicate (coagulase-negative) S. epidermidis strains. MSSE, methicillin-susceptible S. epidermidis; MRSE, methicillin-resistant S. epidermidis; VISE, vancomycin-intermediate S. epidermidis.

Values in bold correspond to antibiotics for which serial passages of the indicated strain were not performed.

Three S. aureus strains passaged in the presence of trimethoprim gave rise to clones for which MICs of this drug were >128 μg/ml by ≤20 transfers, due to Phe98Tyr (ATCC 29213 and SA505) or Leu40Tyr (ATCC 43300) mutations in chromosomal DHFR genes; neither of these mutations had an impact on the strains' susceptibilities to the dihydrophthalazines. The trimethoprim MIC of 64 μg/ml achieved for a clone of S. epidermidis strain CN197 by 50 serial transfers may be related to a Gly43Arg mutation in the chromosomal DHFR gene (Basilea Pharmaceutica International AG, data on file).

For nine strains passaged in the presence of rifampin, MICs of this drug rose to >128 μg/ml by ≤12 transfers, consistent with reports that rifampin supports relatively rapid rates of endogenous resistance emergence (5). Mixed results were obtained for linezolid and clindamycin: after 50 passages in the presence of linezolid, MICs of the oxazolidinone ranged from 16 μg/ml (for 4 of 10 strains) to 128 μg/ml (for 2 of 10 strains), whereas after ≤50 passages in the presence of clindamycin, MICs of the lincosamide varied from 2 to 4 μg/ml (for 3 of 6 strains) to 32 to >128 μg/ml (for 3 of 6 strains). Following 50 serial passages in the presence of the respective antibiotic, none of the strains developed resistance toward minocycline or vancomycin according to CLSI breakpoints (13).

High MICs (≥128 μg/ml) of BAL0030543, BAL0030544, and BAL0030545 for clones of strains VRS1 and CN057 persisted following 10 passages in the absence of antibiotic, MIC drops of ≥2 log2 steps for clones of CN051 and CN225 in drug-free medium occurred, and mixed results were obtained for clones of SA145 and CN345 (Tables 5 and 6). A comparison of DHFR amino acid sequences corresponding to chromosomal and plasmid DHFR structural genes and the regions within 100 nucleotides upstream (encompassing the promoter region) and 100 nucleotides downstream of the DHFR structural genes of the six strains (SA145, VRS1, CN051, CN057, CN225, and CN345) for which one or more of the dihydrophthalazine antifolates displayed a conspicuous increase in MIC during serial passage in the presence of subinhibitory concentrations of these drugs revealed, in most cases, no sequence changes. Thus, the MIC variations may be attributable to regulatory elements affecting staphylococcal DHFR expression and/or the uptake or efflux of the drugs (6, 17).

TABLE 5.

MIC changes as a consequence of serial passage

| Strain | Antifolate | Change in MIC (Δlog2)a resulting from passage:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| With antibiotic | Without antibiotic | ||

| S. aureus ATCC 29213 | BAL0030543 | +8 | ND |

| BAL0030544 | +3 | ND | |

| BAL0030545 | +4 | ND | |

| SA505 | BAL0030543 | +6 | ND |

| BAL0030544 | +8 | ND | |

| BAL0030545 | +6 | ND | |

| S. aureus ATCC 43300 | BAL0030543 | +7 | ND |

| BAL0030544 | +5 | ND | |

| BAL0030545 | +5 | ND | |

| SA145 | BAL0030543 | +9 | −4 |

| BAL0030544 | +10 | 0 | |

| BAL0030545 | +9 | 0 | |

| VRS1 | BAL0030543 | +9 | −1 |

| BAL0030544 | +10 | 0 | |

| BAL0030545 | +8 | 0 | |

| CN051 | BAL0030543 | +8 | −2 |

| BAL0030544 | +11 | −6 | |

| BAL0030545 | +7 | −6 | |

| CN057 | BAL0030543 | +4 | 0 |

| BAL0030544 | +5 | −1 | |

| BAL0030545 | +5 | −1 | |

| CN197 | BAL0030543 | +5 | ND |

| BAL0030544 | +1 | ND | |

| BAL0030545 | +4 | ND | |

| CN225 | BAL0030543 | +9 | −4 |

| BAL0030544 | +10 | −7 | |

| BAL0030545 | +10 | −7 | |

| CN345 | BAL0030543 | +7 | −3 |

| BAL0030544 | +12 | −7 | |

| BAL0030545 | +6 | −1 | |

MIC changes as a consequence of serial passage in the presence of subinhibitory concentrations of dihydrophthalazine antifolates and subsequent passage (10 times) in antibiotic-free medium are expressed as log2 dilution steps (Δlog2). ND, not determined.

TABLE 6.

MICs and DHFRs for selected strains

| Straina | Antifolate | Passageb (MIC [μg/ml]) | Identity, phenotype, and/or mutation(s)c of:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosomally encoded DHFR | Plasmid-encoded DHFR(s) | |||

| SA145 | BAL0030543 | 0 (0.5) | wt | wt S1 |

| 37 (>128) | wt | wt S1 | ||

| +10× −Abx (16) | wt | wt S1, I31M S1d | ||

| BAL0030544 | 0 (0.25) | wt | wt S1 | |

| 47 (>128) | wt | L28S S1 | ||

| +10× −Abx (>128) | ND | ND | ||

| BAL0030545 | 0 (0.25) | wt | wt S1 | |

| 50 (128) | wt | wt S1, I31M S1d | ||

| +10× −Abx (128) | ND | ND | ||

| VRS1 | BAL0030543 | 0 (0.5) | wt | wt S1 |

| 15 (>128) | wt | L28V I31M S1 | ||

| +10× −Abx (128) | ND | ND | ||

| BAL0030544 | 0 (0.25) | wt | wt S1 | |

| 20 (>128) | wt | L28V I31M S1 | ||

| +10× −Abx (>128) | ND | ND | ||

| BAL0030545 | 0 (1) | wt | wt S1 | |

| 25 (>128) | wt | L28V I31M S1 | ||

| +10× −Abx (>128) | ND | ND | ||

| CN051 | BAL0030543 | 0 (0.25) | T46N, F98Y, K160E | None |

| 50 (64) | L24I, T46N, F98Y, K160E | None | ||

| +10× −Abx (16) | ND | ND | ||

| BAL0030544 | 0 (0.125) | T46N, F98Y, K160E | None | |

| 38 (>128) | T46N, F98Y, K160E | None | ||

| +10× −Abx (4) | T46N, F98Y, K160E | None | ||

| BAL0030545 | 0 (0.5) | T46N, F98Y, K160E | None | |

| 50 (64) | T46N, F98Y, K160E | None | ||

| +10× −Abx (1) | T46N, F98Y, K160E | None | ||

| CN057 | BAL0030543 | 0 (8) | L20I, F98Y, H149R | None |

| 50 (128) | L20I, F98Y, H149R | None | ||

| +10× −Abx (128) | ND | ND | ||

| BAL0030544 | 0 (8) | L20I, F98Y, H149R | None | |

| 15 (>128) | L20I, F98Y, H149R | None | ||

| +10× −Abx (128) | ND | ND | ||

| BAL0030545 | 0 (8) | L20I, F98Y, H149R | None | |

| 23 (>128) | L20I, F98Y, H149R | None | ||

| +10× −Abx (128) | ND | ND | ||

| CN225 | BAL0030543 | 0 (0.25) | wt | wt S1 |

| 50 (128) | wt | wt S1 | ||

| +10× −Abx (8) | wt | wt S1 | ||

| BAL0030544 | 0 (0.25) | wt | wt S1 | |

| 38 (>128) | wt | wt S1 | ||

| +10× −Abx (2) | wt | wt S1 | ||

| BAL0030545 | 0 (0.25) | wt | wt S1 | |

| 36 (>128) | wt | wt S1 | ||

| +10× −Abx (2) | wt | wt S1 | ||

| CN345 | BAL0030543 | 0 (0.125) | wt | None |

| 50 (16) | wt | None | ||

| +10× −Abx (2) | wt | None | ||

| BAL0030544 | 0 (0.06) | wt | None | |

| 33 (>128) | wt | None | ||

| +10× −Abx (2) | wt | None | ||

| BAL0030545 | 0 (0.06) | wt | None | |

| 50 (4) | wt | None | ||

| +10× −Abx (2) | ND | ND | ||

Designations beginning with SA indicate S. aureus strains; designations beginning with CN indicate (coagulase-negative) S. epidermidis strains.

+10× −Abx, subsequent passage of the strain from the preceding passage 10 times in MHB without antibiotic.

wt, wild type; ND, not determined.

Due possibly to the presence of a multicopy plasmid.

After ≤50 serial passages in the presence of subinhibitory concentrations of BAL0030543, BAL0030544, or BAL0030545, amino acid substitutions Leu28Ser and/or Ile31Met in the plasmid-borne S1 isozyme [encoded by dfr(A)] were detected in clones of S. aureus strains SA145 and VRS1 for which dihydrophthalazines had elevated MICs. After ≤50 serial passages in the presence of dihydrophthalazines, amino acid substitutions Thr46Asn, Phe98Tyr, and Lys160Glu were observed consistently in the chromosomally encoded DHFRs of clones of S. epidermidis strain CN051, whereas amino acid substitutions Leu20Ile, Phe98Tyr, and His149Arg occurred consistently in dihydrophthalazine-nonsusceptible clones of S. epidermidis strain CN057. Additionally, an Leu24Ile mutation was detected in the chromosomal DHFR of a clone of S. epidermidis strain CN051 for which BAL0030543 had an MIC of 64 μg/ml (Table 6). Isoleucyl, isoleucyl, and asparaginyl residues occur at positions 20, 24, and 46, respectively, in the plasmid-encoded [dfr(G)] DHFR isozyme S3 (35), which is not inhibited by the dihydrophthalazines (11).

Single-step resistance frequencies for BAL0030543, BAL0030544, BAL0030545, and comparators were obtained for the 10 parental strains used in multipassage selection studies (Table 7). Frequency of resistance to the dihydrophthalazine antifolates, expressed as the number of resistant colonies per inoculum, ranged from 4.6 × 10−5 to 3.0 × 10−8 at 2× MIC to 3.2 × 10−6 to <3.4 × 10−11 at 8× MIC of BAL0030543, 8.0 × 10−5 to 4.5 × 10−9 at 2× MIC to 1.6 × 10−5 to <4.0 × 10−11 at 8× MIC of BAL0030544, and 1.7 × 10−4 to <4.0 × 10−11 at 2× MIC to 4.6 × 10−5 to <3.3 × 10−11 at 8× MIC of BAL0030545. These results point toward considerable variability among strains with respect to preexistent subpopulations nonsusceptible to the dihydrophthalazines. Single-step resistance frequencies of 10−10 to 10−11 for linezolid and vancomycin occurred across all strains surveyed at both 2× MIC and 8× MIC, indicating that the preexistent subpopulations nonsusceptible to these antibiotics were smaller than those nonsusceptible to the dihydrophthalazine antifolates.

TABLE 7.

Resistance frequencies of staphylococcal strains by single-step methodology

| Straina | Drug | Resistance frequency at:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2× MIC | 4× MIC | 8× MIC | ||

| S. aureus | BAL0030543 | 3.1 × 10−6 | 4.6 × 10−8 | 2.3 × 10−9 |

| ATCC 29213 | BAL0030544 | 4.5 × 10−9 | 3.5 × 10−9 | <5.0 × 10−11 |

| BAL0030545 | 9.0 × 10−9 | <3.3 × 10−11 | <3.3 × 10−11 | |

| Trimethoprim | 3.0 × 10−6 | 1.5 × 10−7 | 9.0 × 10−9 | |

| Vancomycin | <4.5 × 10−11 | <4.5 × 10−11 | <4.5 × 10−11 | |

| Linezolid | <7.1 × 10−11 | <7.1 × 10−11 | <7.1 × 10−11 | |

| Clindamycin | <5.0 × 10−11 | <5.0 × 10−11 | <5.0 × 10−11 | |

| Minocycline | <4.5 × 10−11 | <4.5 × 10−11 | <4.5 × 10−11 | |

| Rifampin | 5.4 × 10−8 | 4.6 × 10−8 | <4.6 × 10−8 | |

| SA505 | BAL0030543 | 3.0 × 10−8 | 6.0 × 10−9 | <5.0 × 10−11 |

| BAL0030544 | 1.7 × 10−8 | <5.0 × 10−11 | <5.0 × 10−11 | |

| BAL0030545 | 2.8 × 10−9 | <4.0 × 10−11 | <4.0 × 10−11 | |

| Trimethoprim | <5.0 × 10−11 | <5.0 × 10−11 | <5.0 × 10−11 | |

| Vancomycin | <4.5 × 10−11 | <4.5 × 10−11 | <4.5 × 10−11 | |

| Linezolid | <6.7 × 10−11 | <6.7 × 10−11 | <6.7 × 10−11 | |

| Clindamycin | <5.0 × 10−11 | <5.0 × 10−11 | <5.0 × 10−11 | |

| Minocycline | <4.0 × 10−11 | <4.0 × 10−11 | <4.0 × 10−11 | |

| Rifampin | 1.3 × 10−7 | 9.3 × 10−8 | 9.1 × 10−8 | |

| S. aureus | BAL0030543 | 5.9 × 10−8 | 1.2 × 10−8 | <5.9 × 10−11 |

| ATCC 43300 | BAL0030544 | 2.7 × 10−8 | <4.5 × 10−11 | <4.5 × 10−11 |

| BAL0030545 | 4.0 × 10−9 | <4.0 × 10−11 | <4.0 × 10−11 | |

| Trimethoprim | 3.0 × 10−7 | 5.0 × 10−9 | 3.0 × 10−9 | |

| Vancomycin | <5.3 × 10−11 | <5.3 × 10−11 | <5.3 × 10−11 | |

| Linezolid | <1.4 × 10−10 | <1.4 × 10−10 | <1.4 × 10−10 | |

| Clindamycin | Not tested | Not tested | Not tested | |

| Minocycline | <6.7 × 10−11 | <6.7 × 10−11 | <6.7 × 10−11 | |

| Rifampin | 1.7 × 10−7 | 1.2 × 10−7 | <1.2 × 10−7 | |

| SA145 | BAL0030543 | 2.1 × 10−7 | 6.9 × 10−8 | <3.4 × 10−11 |

| BAL0030544 | 2.2 × 10−6 | <4.0 × 10−11 | <4.0 × 10−11 | |

| BAL0030545 | <4.0 × 10−11 | <4.0 × 10−11 | <4.0 × 10−11 | |

| Trimethoprim | Not tested | Not tested | Not tested | |

| Vancomycin | <5.0 × 10−11 | <5.0 × 10−11 | <5.0 × 10−11 | |

| Linezolid | <5.0 × 10−11 | <5.0 × 10−11 | <5.0 × 10−11 | |

| Clindamycin | Not tested | Not tested | Not tested | |

| Minocycline | <7.7 × 10−11 | <7.7 × 10−11 | <7.7 × 10−11 | |

| Rifampin | >5.0 × 10−8 | 5.0 × 10−8 | 2.0 × 10−8 | |

| VRS1 | BAL0030543 | 2.9 × 10−6 | 4.3 × 10−9 | <4.3 × 10−9 |

| BAL0030544 | 6.8 × 10−9 | 1.6 × 10−10 | <5.3 × 10−11 | |

| BAL0030545 | 4.5 × 10−6 | 9.1 × 10−10 | <4.5 × 10−11 | |

| Trimethoprim | Not tested | Not tested | Not tested | |

| Vancomycin | Not tested | Not tested | Not tested | |

| Linezolid | <1.4 × 10−10 | <1.4 × 10−10 | <1.4 × 10−10 | |

| Clindamycin | Not tested | Not tested | Not tested | |

| Minocycline | <5.0 × 10−11 | <5.0 × 10−11 | <5.0 × 10−11 | |

| Rifampin | Not tested | Not tested | Not tested | |

| CN051 | BAL0030543 | >3.2 × 10−5 | 3.2 × 10−5 | <5.3 × 10−8 |

| BAL0030544 | 7.1 × 10−5 | 7.1 × 10−6 | 2.4 × 10−7 | |

| BAL0030545 | 2.7 × 10−5 | 1.8 × 10−7 | <9.1 × 10−8 | |

| Trimethoprim | Not tested | Not tested | Not tested | |

| Vancomycin | <8.3 × 10−11 | <8.3 × 10−11 | <8.3 × 10−11 | |

| Linezolid | <5.0 × 10−11 | <5.0 × 10−11 | <5.0 × 10−11 | |

| Clindamycin | <1.0 × 10−10 | <1.0 × 10−10 | <1.0 × 10−10 | |

| Minocycline | <6.7 × 10−11 | <6.7 × 10−11 | <6.7 × 10−11 | |

| Rifampin | 1.0 × 10−7 | 2.9 × 10−8 | 2.1 × 10−8 | |

| CN057 | BAL0030543 | 4.0 × 10−5 | 8.0 × 10−6 | 3.2 × 10−6 |

| BAL0030544 | 8.0 × 10−5 | 4.8 × 10−5 | 1.6 × 10−5 | |

| BAL0030545 | 1.7 × 10−4 | 8.6 × 10−5 | 4.6 × 10−5 | |

| Trimethoprim | Not tested | Not tested | Not tested | |

| Vancomycin | <1.0 × 10−10 | <1.0 × 10−10 | <1.0 × 10−10 | |

| Linezolid | <6.7 × 10−11 | <6.7 × 10−11 | <6.7 × 10−11 | |

| Clindamycin | 6.7 × 10−9 | 1.7 × 10−10 | <8.3 × 10−11 | |

| Minocycline | <1.3 × 10−10 | <1.3 × 10−10 | <1.3 × 10−10 | |

| Rifampin | >4.0 × 10−8 | 4.0 × 10−8 | 2.7 × 10−8 | |

| CN197 | BAL0030543 | 3.3 × 10−6 | 3.3 × 10−7 | 3.3 × 10−8 |

| BAL0030544 | 3.3 × 10−6 | 1.7 × 10−7 | 8.3 × 10−8 | |

| BAL0030545 | 3.7 × 10−7 | 3.3 × 10−7 | 2.2 × 10−9 | |

| Trimethoprim | <6.7 × 10−11 | <6.7 × 10−11 | <6.7 × 10−11 | |

| Vancomycin | <6.3 × 10−11 | <6.3 × 10−11 | <6.3 × 10−11 | |

| Linezolid | <5.6 × 10−11 | <5.6 × 10−11 | <5.6 × 10−11 | |

| Clindamycin | <6.7 × 10−11 | <6.7 × 10−11 | <6.7 × 10−11 | |

| Minocycline | 1.7 × 10−9 | <8.3 × 10−11 | <8.3 × 10−11 | |

| Rifampin | 7.1 × 10−8 | 1.4 × 10−8 | 1.3 × 10−8 | |

| CN225 | BAL0030543 | 2.7 × 10−7 | 7.8 × 10−9 | 3.9 × 10−10 |

| BAL0030544 | 4.2 × 10−6 | 3.7 × 10−8 | 3.1 × 10−9 | |

| BAL0030545 | 9.0 × 10−8 | <3.3 × 10−10 | <3.3 × 10−10 | |

| Trimethoprim | Not tested | Not tested | Not tested | |

| Vancomycin | <2.0 × 10−10 | <2.0 × 10−10 | <2.0 × 10−10 | |

| Linezolid | <1.8 × 10−10 | <1.8 × 10−10 | <1.8 × 10−10 | |

| Clindamycin | Not tested | Not tested | Not tested | |

| Minocycline | 4.0 × 10−9 | <1.0 × 10−9 | <1.0 × 10−9 | |

| Rifampin | >2.7 × 10−8 | 2.7 × 10−8 | 2.0 × 10−8 | |

| CN345 | BAL0030543 | 4.6 × 10−5 | <7.7 × 10−8 | <7.7 × 10−8 |

| BAL0030544 | 3.3 × 10−7 | 3.3 × 10−9 | 1.7 × 10−9 | |

| BAL0030545 | 2.9 × 10−5 | 5.9 × 10−7 | 2.0 × 10−8 | |

| Trimethoprim | Not tested | Not tested | Not tested | |

| Vancomycin | <1.0 × 10−10 | <1.0 × 10−10 | <1.0 × 10−10 | |

| Linezolid | <5.0 × 10−11 | <5.0 × 10−11 | <5.0 × 10−11 | |

| Clindamycin | <1.0 × 10−10 | <1.0 × 10−10 | <1.0 × 10−10 | |

| Minocycline | <3.4 × 10−10 | <3.4 × 10−10 | <3.4 × 10−10 | |

| Rifampin | 4.6 × 10−8 | 3.1 × 10−8 | 2.3 × 10−8 | |

For strain descriptions, see Table 4.

At 2× MIC, the weakest selection pressure applied in the single-step analyses, the frequencies of resistance to clindamycin, linezolid, minocycline, and vancomycin tended to be lower than those to dihydrophthalazine antifolates. The highest resistance frequencies for BAL0030543, BAL0030544, and BAL0030545 were found for VRS1, CN051, and CN057, whereas the lowest resistance frequencies were found for SA505 and ATCC 43300. Similarly, by ≤50 serial passages, very high MICs of the dihydrophthalazines for VRS1, CN051, and CN057 emerged, whereas much lower MICs for SA505 and ATCC 43300 were obtained. At 8× MIC, the strongest selection pressure applied in the single-step analyses, dihydrophthalazine antifolate resistance frequencies clustered at lower values for S. aureus (10−9 to 10−11) than for S. epidermidis (10−5 to 10−10).

The results of this study suggest a possible role for dihydrophthalazine antifolates in the treatment of staphylococcal infections, including those caused by methicillin- and vancomycin-resistant strains and LzdNS strains. The dihydrophthalazines were bactericidal at low concentrations, and the application of good antibiotic stewardship (29) ought to preserve their antistaphylococcal activities and retard the emergence and dissemination of resistance toward these compounds. The MICs of BAL0030543, BAL0030544, and BAL0030545 were ≤0.5 μg/ml for 98.7% of the S. aureus strains surveyed, whereas the MICs of the three compounds were ≤1 μg/ml for 98.1% of the CoNS strains surveyed. These novel compounds inhibited not only wild-type and mutant chromosomally encoded DHFRs in S. aureus [dfr(B)] and S. epidermidis [dfr(C)] but also the plasmid-borne DHFR isozyme S1 encoded by dfr(A), which is highly resistant to trimethoprim. Unlike trimethoprim, the dihydrophthalazines were active against staphylococci harboring a chromosomal DHFR Phe98Tyr mutation (11). With their good oral bioavailabilities and favorable pharmacological/toxicological properties (20), dihydrophthalazine antifolates BAL0030543, BAL0030544, and BAL0030545 are potentially attractive therapies for multidrug-resistant staphylococoal infections, including those for which long-term (>2-week) therapy is warranted.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from Basilea Pharmaceutica International AG to the Hershey Medical Center, Pennsylvania State University.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 February 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Almeida, R. A., and S. P. Oliver. 2001. Interaction of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species with bovine mammary epithelial cells. Microb. Pathog. 31:205-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appelbaum, P. C. 2007. Reduced glycopeptide susceptibility in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 30:398-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asbell, P. A., K. A. Colby, S. Deng, P. McDonnell, D. M. Meisler, M. B. Raizman, J. D. Sheppard, Jr., and D. F. Sahm. 2008. Ocular TRUST: nationwide antimicrobial susceptibility patterns in ocular isolates. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 145:951-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beekmann, S. E., D. N. Gilbert, P. M. Polgreen, and the IDSA Emerging Infections Network. 2008. Toxicity of extended courses of linezolid: results of an Infectious Diseases Society of America Emerging Infections Network survey. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 62:407-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Binda, G., E. Domenichini, A. Gottardi, B. Orlandi, E. Ortelli, B. Pacini, and G. Fowst. 1971. Rifampicin, a general review. Arzneimittel-Forschung 21:1907-1977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bjorland, J., T. Steinum, B. Kvitle, S. Waage, M. Sunde, and E. Heir. 2005. Widespread distribution of disinfectant resistance genes among staphylococci of bovine and caprine origin in Norway. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:4363-4368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boelens, J. J., J. Dankert, J. L. Murk, J. J. Weening, T. van der Poll, K. P. Dingemans, L. Koole, J. D. Laman, and S. A. J. Zaat. 2000. Biomaterial-associated persistence of Staphylococcus epidermidis in pericatheter macrophages. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1337-1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bogdanovich, T., L. M. Ednie, S. Shapiro, and P. C. Appelbaum. 2005. Antistaphylococcal activity of ceftobiprole, a new broad-spectrum cephalosporin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:4210-4219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bolmström, A., A. Karlsson, and P. Wong. 1999. ‘Macro’-method conditions are optimal for detection of low-level glycopeptide resistance in staphylococci. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 5(Suppl. 3):113. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burdeska, A., M. Ott, W. Bannwarth, and R. L. Then. 1990. Identical genes for trimethoprim-resistant dihydrofolate reductase from Staphylococcus aureus in Australia and central Europe. FEBS Lett. 266:159-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caspers, P., B. Gaucher, and S. Shapiro. 2007. Dihydrophthalazine antifolates, a family of novel antibacterial drugs: resistance and bactericidal properties towards staphylococci, abstr. F1-932. Abstr. 47th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.

- 12.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2006. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 7th ed.; approved standard. CLSI publication no. M7-A7. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 13.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2008. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 18th informational supplement. CLSI publication no. M100-S18. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 14.Dale, G. E., R. L. Then, and D. Stüber. 1993. Characterization of the gene for chromosomal trimethoprim-sensitive dihydrofolate reductase of Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:1400-1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Del'Alamo, L., R. F. Cereda, I. Tosin, E. A. Miranda, and H. S. Sader. 1999. Antimicrobial susceptibility of coagulase-negative staphylococci and characterization of isolates with reduced susceptibility to glycopeptides. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 34:185-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de la Torre, M., M. Sanchez, G. Morales, E. Baos, A. Arribi, N. García, R. Andrade, B. Pelaez, M. P. Pacheco, S. Domingo, J. Conesa, M. Nieto, F. J. Candel, and J. Picazo. 2008. Outbreak of linezolid-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in intensive care, abstr. C2-1835a. Program/Abstr. Addendum 48th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother./46th Annu. Meet. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am.

- 17.Ding, Y., Y. Onodera, J. C. Lee, and D. C. Hooper. 2008. NorB, an efflux pump in Staphylococcus aureus strain MW2, contributes to bacterial fitness in abscesses. J. Bacteriol. 190:7123-7129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fritsche, T. R., H. S. Sader, and R. N. Jones. 2007. Potency and spectrum of garenoxacin tested against an international collection of skin and soft tissue infection pathogens: report from the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program (1999-2004). Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 58:19-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garrett, D. O., E. Jochimsen, K. Murfitt, B. Hill, S. McAllister, P. Nelson, R. V. Spera, R. K. Sall, F. C. Tenover, J. Johnston, B. Zimmer, and W. R. Jarvis. 1999. The emergence of decreased susceptibility to vancomycin in Staphylococcus epidermidis. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 20:167-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaucher, B., A. Schmitt-Hoffmann, P. Caspers, K. Gebhardt, C. Nuoffer, H. Urwyler, and J. Heim. 2007. Dihydrophthalazine antifolates, a family of novel antibacterial drugs: in vitro and in vivo pharmacological profiles, abstr. F1-935. Abstr. 47th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.

- 21.Hackbarth, C. J., H. F. Chambers, and M. A. Sande. 1986. Serum bactericidal activity of rifampin in combination with other antimicrobial agents against Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 29:611-613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson, M. D., and C. F. Decker. 2008. Antimicrobial agents in treatment of MRSA infections. Dis. Mon. 54:793-800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones, R. N., J. E. Ross, M. Castanheira, and R. E. Mendes. 2008. United States resistance surveillance results for linezolid (LEADER Program for 2007). Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 62:416-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kosowska-Shick, K., K. Julian, J. Kishel, P. McGhee, P. C. Appelbaum, and C. Whitener. 2008. Molecular and epidemiological characteristics of linezolid-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci at a tertiary-care hospital, abstr. C2-1081. Abstr. 48th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.

- 25.McDougal, L. K., C. D. Steward, G. E. Killgore, J. M. Chaitram, S. K. McAllister, and F. C. Tenover. 2003. Pulsed-field electrophoresis typing of oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from the United States: establishing a national database. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5113-5120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mendes, R. E., L. M. Deshpande, M. Castanheira, J. DiPersio, M. A. Saubolle, and R. N. Jones. 2008. First report of cfr-mediated resistance to linezolid in human staphylococcal clinical isolates recovered in the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:2244-2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merkel, G. J., and B. A. Scofield. 2001. Interaction of Staphylococcus epidermidis with endothelial cells in vitro. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 189:217-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller, L. G., F. Perdreau-Remington, G. Rieg, S. Mehdi, J. Perlroth, A. S. Bayer, A. W. Tang, T. O. Phung, and B. Spellberg. 2005. Necrotizing fasciitis caused by community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Los Angeles. N. Engl. J. Med. 352:1445-1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Owens, R. C., Jr. 2008. Antimicrobial stewardship: concepts and strategies in the 21st century. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 61:110-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pan, A., S. Lorenzotti, and A. Zoncada. 2008. Registered and investigational drugs for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. Recent Pat. Anti-Infect. Drug Discov. 3:10-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pankuch, G. A., M. R. Jacobs, and P. C. Appelbaum. 1994. Study of comparative antipneumococcal activities of penicillin G, RP 59500, erythromycin, sparfloxacin, ciprofloxacin, and vancomycin by using time-kill methodology. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:2065-2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Potoski, B. A., J. Adams, L. Clarke, K. Shutt, P. K. Linden, C. Baxter, A. W. Pasculle, B. Capitano, A. Y. Peleg, D. Szabo, and D. L. Paterson. 2006. Epidemiological profile of linezolid-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci. Clin. Infect. Dis. 43:165-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruef, C. 2004. Epidemiology and clinical impact of glycopeptide resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Infection 32:315-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rybak, M. J., D. M. Cappelletty, T. Moldovan, J. R. Aeschlimann, and G. W. Kaatz. 1998. Comparative in vitro activities and postantibiotic effects of the oxazolidinone compounds eperezolid (PNU-100592) and linezolid (PNU-100766) versus vancomycin against Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative staphylococci, Enterococcus faecalis, and Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:721-724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sekiguchi, J.-I., P. Tharavichitkul, T. Miyoshi-Akiyama, V. Chupia, T. Fujino, M. Araake, A. Irie, K. Morita, T. Kuratsuji, and T. Kirikae. 2005. Cloning and characterization of a novel trimethoprim-resistant dihydrofolate reductase from a nosocomial isolate of Staphylococcus aureus CM.S2 (IMCJ1454). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:3948-3951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shapiro, S., L. Thenoz, S. Heller, and P. Caspers. 2007. Dihydrophthalazine antifolates, a family of novel antibacterial drugs: in vitro activities against diverse bacterial pathogens, abstr. F1-933. Abstr. 47th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.

- 37.Sutherland, B., and G. N. Rolinson. 1964. Characteristics of methicillin-resistant staphylococci. J. Bacteriol. 87:887-899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szumowski, J. D., D. E. Cohen, F. Kanaya, and K. H. Mayer. 2007. Treatment and outcomes of infections by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus at an ambulatory clinic. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:423-428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tenover, F. C., and R. C. Moellering, Jr. 2007. The rationale for revising the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute vancomycin minimal inhibitory concentration interpretive criteria for Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44:1208-1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Venkatesh, M. P., F. Placencia, and L. E. Weisman. 2006. Coagulase-negative staphylococcal infections in the neonate and child: an update. Semin. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. 17:120-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Veyssier, P., and A. Bryskier. 2005. Dihydrofolate reductase inhibitors, nitroheterocycles (furans), and 8-hydroxyquinolines, p. 941-963. In A. Bryskier (ed.), Antimicrobial agents: antibacterials and antifungals. ASM Press, Washington, DC.