Abstract

Treponema denticola, a spirochete associated with periodontitis, is abundant at the leading edge of subgingival plaque, where it interacts with gingival epithelia. T. denticola produces a number of virulence factors, including dentilisin, a protease which is cytopathic to host cells, and FhbB, a unique T. denticola lipoprotein that binds complement regulatory proteins. Earlier analyses suggested that FhbB specifically bound to factor H (FH)-like protein 1 (FHL-1). However, by using dentilisin-deficient mutants of T. denticola, we found that T. denticola preferentially binds FH and not FHL-1, and that FH is then cleaved by dentilisin to yield an FH subfragment of ∼50 kDa. FH bound to dentilisin-deficient mutants but was not cleaved and retained its ability to serve as a cofactor for factor I in the cleavage of C3b. To assess the molecular basis of the interaction of FhbB with FH, mutational analyses were conducted. Replacement of specific residues in widely separated domains of FhbB and disruption of a central alpha helix with coiled-coil formation probability attenuated or eliminated FH binding. The data presented here are the first to demonstrate the retention at the cell surface of a proteolytic cleavage product of FH. The precise role of this FH fragment in the host-pathogen interaction remains to be determined.

Adult periodontitis, the most common infection of middle-aged adults, affects approximately 116 million adults in the United States (3). Periodontal disease is a multifactorial process involving alterations of the overall composition of the oral flora coupled with host-determined susceptibility factors (73). The process is initiated by the formation and spread of polymicrobial biofilms that ultimately progress to plaque formation. The human oral cavity may contain up to 700 bacterial species (58), with the subgingival plaque estimated to consist of up to 415 species (57). Treponema denticola is one of the dominant spirochete species at the leading edge of plaque, and a clear correlation has been demonstrated between its abundance and the occurrence and severity of periodontal disease (reviewed in reference 15).

We previously reported that T. denticola binds at least one member of the factor H (FH) protein family (43). In humans, the FH protein family consists of FH, FH-like protein 1 (FHL-1), and five FH-related proteins designated FHR1 through FHR5 (35). FH and FHL-1 serve as cofactors in the factor I-mediated cleavage of C3b, a key opsonin, and accelerate the decay of the C3 convertase complex, leading to downregulation of C3b production (56, 66, 67, 74). Evasion of complement by oral bacteria such as T. denticola is essential as complement proteins are present in gingival fluid at levels as high as 85% of that reported for serum (68). In addition, there is evidence that complement is more active in saliva than in serum (8, 9). The binding to cell-anchored FH family proteins by some microbial pathogens has also been demonstrated to be an important adherence-and-invasion mechanism (5, 23, 55).

The interaction of FH with T. denticola has been demonstrated to be mediated by the FhbB protein, an 11.4-kDa surface-exposed lipoprotein. FhbB shows little or no homology with other FH binding proteins but harbors a centrally located coiled-coil element which has been identified in several spirochetes as an important determinant of FH binding (29, 43, 44, 47, 63). The molecular basis of the interactions between complement regulators and pathogen-produced binding proteins has been an area of intensive investigation in terms of both pathogenesis and vaccine development (69, 76). It is noteworthy that while numerous pathogens are able to bind FH and/or FHL-1 (2, 13, 14, 20, 21, 24, 26-28, 31, 48, 50-52, 55, 61, 62), none of the identified FH/FHL-1 binding proteins display discernible, contiguous stretches of sequence homology that indicate a specific primary sequence involved in this interaction (4, 12, 13, 20, 24, 26, 28, 31, 36, 43, 50, 59, 61). However, critical and conserved internal structural elements have been identified through site-directed and random mutagenesis. Specifically, coiled-coil elements, or at least alpha helices with a hydrophobic periodicity, appear to be critical in the proper formation and presentation of the FH and/or FHL-1 binding pocket (29, 30, 44, 47, 52, 63). The presence of coiled-coil domains in FH binding proteins is a shared and conserved feature of this class of proteins.

In this study, we further investigated the interaction of FH family proteins with FhbB. Data provided here suggest that full-length FH is preferentially bound to FhbB and then cleaved by the T. denticola serine protease dentilisin to yield an FH fragment that remains bound to the cell surface. This novel interaction has not been previously described for any other pathogen. Dentilisin, which is perhaps the best studied of the T. denticola proteases, is a complex multisubunit protein (6, 7, 16, 17, 33, 34, 38). Dentilisin has been demonstrated to cleave other host proteins, including fibrinogen (6), fibronectin, type IV collagen (34), and the complement protein C3 (75). In addition, it may facilitate interactions with other oral bacteria, including Porphyromonas (25). In this study, we have also assessed the molecular basis of the FH-FhbB interaction. The findings of this study advance our understanding of molecular aspects of FH binding as a virulence mechanism and provide important information that can be used in further defining the role of FH and the novel FH subfragment in T. denticola pathogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial cultures and growth conditions.

T. denticola strains 35405, CCE, and CKE were grown in NOS medium as described previously (44). CCE (19) and CKE (38) are derivatives of T. denticola 35405 in which the specific regions of the operon that code for dentilisin were inactivated by allelic exchange and insertion of an erythromycin resistance cassette. CCE and CKE were maintained without antibiotic selection. The dentilisin activity of all strains was assessed with the SAAPFNA assay as described previously (11).

DNA sequence analyses and computer-assisted analysis of FhbB structure.

The sequences of all cloned genes, constructs, and site-directed mutants analyzed in this study were determined by automated DNA sequencing. The sequences determined were translated with the TRANSLATE program. Secondary structure predictions were obtained with the GOR program. The probability of coiled-coil formation was assessed with the COILS program (39). The COILS analysis was run without and with weighting (2.5×) of the a and d positions of the coiled-coil heptad repeat with the MDIK matrix and windows of 21 and 28 amino acid (aa) residues.

Generation of recombinant proteins: LIC, expression, and purification.

Primers (Integrated DNA Technologies) for amplification of fhbB or subfragments of fhbB were generated based on previously determined sequences (Table 1). The full-length gene or portions thereof were PCR amplified under standard conditions. Some primers were designed with overhang sequences that allow ligase-independent cloning (LIC) of the amplicons into the pET32 Ek/LIC vector (Novagen) as described previously (47). This vector allows the production recombinant proteins with an N-terminal fusion of 17 kDa that contains both S and six-His tags. All of the procedures used for PCR, cloning, and expression of recombinant proteins were as previously described (52). Briefly, single-stranded tails were generated by treatment of the purified PCR product with T4 DNA polymerase and the amplicons were annealed with the linearized pET32 Ek/LIC vector. To propagate the plasmids, the annealed products were introduced into Escherichia coli NovaBlue(DE3) cells by transformation and plated on LB plates containing 50 μg ml−1 ampicillin. To screen for recombinants, E. coli colonies were picked from the plates and boiled. The presence and size of the inserts in the recombinant plasmids was determined by PCR amplification. To enhance recombinant protein expression in E. coli, recombinant FhbB (r-FhbB) proteins were generated without the leader peptide (22 aa). r-CspA (an FH binding protein used as a positive control) from Borrelia burgdorferi was generated as described previously (44).

TABLE 1.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′)a |

|---|---|

| FhbB Up | CTCTTGACAGTACGTATAGTG |

| FhbB23FLIC | GACGACGACAAGATTACTTTCAAAATGAATACTGCAC |

| FhbB46FLIC | GACGACGACAAGATATTAAAAACTAGACATATACCTGC |

| FhbB75FLIC | GACGACGACAAGATTGTGGATAAAAAACCCGGCAC |

| FhbB78RLIC | GAGGAGAAGCCCGGTTTAGGGTTTTTTATCCACAATTTG |

| FhbB95RLIC | GAGGAGAAGCCCGGTTTAGCGTTTTCTTAATGCAGCTGC |

| FhbB102RLIC | GAGGAGAAGCCCGGTTTACTTTATCTTTTTGGGTAT |

| FhbB ccm1F | CATTATGAAAAGTTTACAAACGCGC |

| FhbB ccm1R | GCGCGTTTGTAAACTTTTCATAATG |

| FhbB ccm2F | GCGCGTGAGAATGAATCAAAAACTAG |

| FhbBccm2R | CTAGTTTTTGATTCATTCTCACGCGC |

| FhbB ccm3F | GCGGTTGAGAATGAAATAAAAACTAG |

| FhbB ccm3R | CTAGTTTTTATTTCATTCTCAACCGC |

| FhbB ccm4F | GCGCTTAAGAATAAATTAAAAACTAG |

| FhbBccm4R | CTAGTTTTTAATTTATTCTTAAGCGC |

| FhbB ccm5F | GCGCTTGTGAATGTATTAAAAACTAG |

| FhbBccm5R | CTAGTTTTTAATACATTCACAAGCGC |

Underlining indicates the tail sequences incorporated into each primer to allow for annealing with LIC vectors, as described in the text.

Purification of recombinant proteins was performed with Qiagen Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) magnetic agarose beads by the manual purification protocol detailed by the manufacturer. Briefly, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-induced E. coli expressing r-FH binding proteins was pelleted, frozen, resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 0.05% Tween 20 [pH 8.0], lysozyme [1 mg/ml]), incubated on ice (30 min), sonicated, and then centrifuged (10,000 × g, 30 min, 4°C). The supernatant was mixed with Ni-NTA magnetic beads (gentle rocking, room temperature, 1 h) and placed in a magnetic separator (1 min), and the supernatant was removed. Wash buffer (lysis buffer with 20 mM imidazole) was added, the cells were washed three times, bound protein was eluted (lysis buffer with 300 mM imidazole) and dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) in Slide-A-Lyzer mini dialysis units (7,000 molecular weight cutoff; Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL), and the protein concentration was determined with a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific).

Immunoblot analyses and affinity ligand binding immunoblot (ALBI) assays.

Immunoblot analyses were performed with recombinant proteins or cell lysates fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) in 12.5% Criterion gels (Bio-Rad). To determine if the various recombinant proteins investigated here bind FH, the FH ALBI assay was used as previously described (52). In brief, membrane-immobilized proteins were incubated with FH (10 ng ml−1; Calbiochem) and washed and bound FH was detected with anti-FH antiserum (dilution of 1:800; Calbiochem) with rabbit anti-goat immunoglobulin G as the secondary antibody (1:40,000; Calbiochem). Chemiluminescence assay was performed with the SuperSignal West Pico substrate (Thermo Scientific).

FH adsorption assay with purified recombinant proteins.

To assess the binding of FH to recombinant proteins, recombinant proteins bound to Ni-NTA magnetic beads were incubated with purified FH, human serum, or PBS (room temperature, 3 h). The samples were then washed to remove unbound protein as described above. As controls, magnetic beads without bound FhbB were also incubated with FH, serum, or PBS. Protein or protein complexes were eluted from the beads with elution buffer, boiled in SDS solubilizing solution, fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore) for immunoblot and/or ALBI assays.

C3b cleavage assays.

The ability of FH bound to T. denticola to serve as a cofactor in the factor I-mediated cleavage of C3b was assessed with a previously described cleavage assay (44). In brief, cells from actively growing cultures of T. denticola were recovered by centrifugation, washed with cold PBS, suspended in PBS (with 10 mM Mg Cl2), and then incubated with purified human FH/FHL-1 (1 h, 37°C). The cells were washed with PBS to remove unbound FH/FHL-1. Factor I (150 ng; Calbiochem) and C3b (250 ng; Calbiochem) were added, and the mixture was incubated for 2 h at 37°C. The samples were fractionated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to membranes, and screened with anti-human C3b antiserum (1:800 dilution; Calbiochem). Detection of C3b and C3b cleavage products was accomplished by immunoblotting as previously described (46). The solution phase controls for these analyses consisted of reactions containing purified human C3b, factor I, and/or FH (no bacterial cells added). The purpose of this set of controls was to demonstrate the specificity of cleavage of C3b by factor I and the dependence of the cleavage on the presence of FH.

Comparative FH binding analyses with wild-type and dentilisin mutant T. denticola.

T. denticola cultures were grown to mid-log phase, the cells were recovered by centrifugation and washed twice with PBS, and the cells were quantified by measuring the absorbance at 600 nm. The cells were then frozen in aliquots at an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5 to generate identical samples for multiple experiments. Aliquots of the cells were then resuspended in 15 μl of PBS containing 1.25 μg of FH (37°C, 1 h). SDS-PAGE solubilizing solution was added, and the samples were boiled, fractionated by SDS-PAGE, immunoblotted, and screened with anti-human FH antiserum (as described above). Time course analyses of FH binding to wild-type and dentilisin mutant strains were also performed. Aliquots of T. denticola cells at an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5 were thawed, suspended in 150 μl of PBS containing 12.5 μg of FH, and incubated at 37°C. Fifteen-microliter aliquots of the mixture were removed at different time points (up to 2 h), mixed with SDS-PAGE solubilizing buffer, boiled, electrophoresed in 12.5% SDS-PAGE gels (Bio-Rad), immunoblotted, and screened with anti-human FH antiserum as described above.

Site-directed and random mutagenesis of FhbB.

Site-directed mutagenesis of FhbB was conducted by a two-step PCR-based approach with mutagenic primers as previously described (44, 45). All PCR amplification reactions were performed with high-fidelity Pfu polymerase (Promega) with a recombinant plasmid containing fhbB as the initial template. For all constructs, the 5′ portion of the gene was PCR amplified with the FhbB Up primer and reverse mutagenic primers that target the regions to be mutated within fhbB. The forward primer used to amplify the 3′ half of the gene was the reverse complement of the mutagenic primer used to amplify the 5′ portion of the gene. The amplicons derived from each half of the gene were purified from an agarose gel with the Qiagen gel extraction kit and combined to serve as the template in another PCR. The two amplicons, which anneal via their complementary ends, were then subjected to eight cycles of PCR. In this reaction, the amplicons essentially serves as “megaprimers.” The FhbB23FLIC and FhbB102RLIC primers (which contain tails that allow cloning by the LIC approach with the pET32 Ek/LIC vector) were added to amplify the full-length mutated gene. The resulting amplicons were gel purified and LIC cloned with protein expression induced as described above. Random mutagenesis was also conducted as part of this study. All methods were as previously described (47), and all methods for protein production are detailed above.

RESULTS

Demonstration of preferential binding of FH by FhbB.

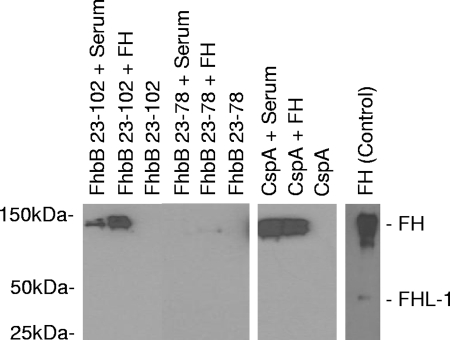

To further assess the ligand binding characteristics of FhbB, a pull-down assay was used in which purified r-FhbB was bound to Ni-coated agarose beads and then incubated with human serum (healthy normal) or purified human FH. B. burgdorferi r-CspA served as a positive control for FH binding (36), and truncated r-FhbB (spanning residues 23 to 78; described in detail below), which lacks ligand binding ability, served as a negative control. Protein complexes were eluted from the beads, separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to membranes, and then screened with a polyclonal anti-FH antiserum that detects both FH and FHL-1. The predominant protein that complexed with r-FhbB was 150 kDa in size, consistent with the molecular mass of FH. Binding of FHL-1 or other FH protein family members was not observed (Fig. 1), even with prolonged exposure of the membrane to film. The data demonstrate that r-FhbB preferentially binds FH. This contrasts with the previously reported binding of a 50-kDa FH-related protein to intact T. denticola cells (43). The important distinction between this study and the earlier study is that in this study the pull-down assay was performed with recombinant protein while in the earlier analysis it was done with whole cells. The basis for this difference in binding results is explained in detail below.

FIG. 1.

Analysis of FH binding by purified r-FhbB and r-FhbB subfragments with a pull-down assay. Pull-down assays were performed as described in the text. r-FhbB proteins and r-CspA (a positive control for FH binding) were incubated with human serum or purified FH for these analyses. After recovery of the complexes, the samples were immunoblotted and bound FH was detected by screening immunoblots with anti-human FH antiserum. The specific recombinant protein used in each reaction and the FH source (human serum, purified FH, or no FH) are indicated above each lane. As a control for detection, an immunoblot strip of purified FH-FHL-1 was also included.

Analysis of the ability of T. denticola 35405 and dentilisin knockout strains (CCE and CKE) to bind and cleave FH.

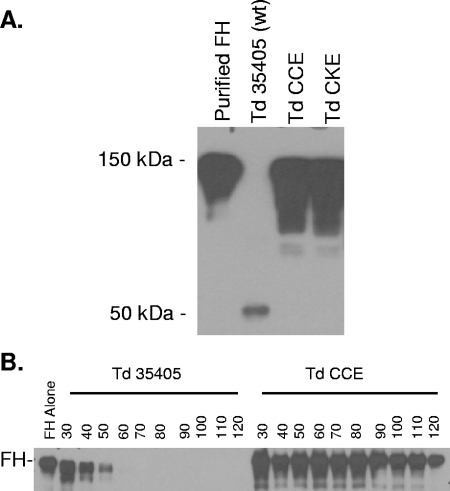

The data presented above demonstrate that r-FhbB binds the 150-kDa FH protein. However, earlier analyses demonstrated that T. denticola cells bound an ∼50-kDa protein that was concluded to be FHL-1 (43). The following experiments were designed to identify the basis for these differing results. We postulated that T. denticola may bind full-length FH to its surface via FhbB and then the bound FH protein is cleaved to yield a 50-kDa FH subfragment. This could explain why only the full-length form of FH was found to interact with r-FhbB (since this recombinant protein preparation would lack other T. denticola-derived proteins). We speculated that dentilisin, a well-characterized serine protease of T. denticola, may be responsible for the cleavage. To assess this, adsorption assays were conducted with T. denticola wild-type strain 35405 (dentilisin positive) and dentilisin-inactivation mutants CCE and CKE) (7). These strains were confirmed to carry an identical fhbB gene and produce FhbB (data not shown). Consistent with earlier analyses (43), the dominant protein that was adsorbed to the surface of strain 35405 was ∼50 kDa in size (Fig. 2A). In contrast, the strain 35405-derived dentilisin inactivation mutants (CCE and CKE) specifically adsorbed a 150-kDa protein determined to be the full-length form of FH. These data indicate that dentilisin is responsible for the cleavage of cell-bound FH to yield the ∼50-kDa FH subfragment. Hence, these adsorption assays indicate that T. denticola may participate in a unique interaction with FH.

FIG. 2.

Demonstration of the cleavage of FH by the T. denticola protease dentilisin. In panel A, whole cells of T. denticola (Td) strain 35405 (wild type [wt]) and dentilisin mutants CCE and CKE were incubated with purified human FH, immunoblotted, and screened with anti-human FH antiserum. In panel B, the potential cleavage of FH by wild-type T. denticola 35405 and the dentilisin mutant (CCE) was assessed over time (in minutes as indicated). Aliquots were recovered at different time points, immunoblotted, and screened with anti-FH antiserum.

To assess the kinetics of FH degradation by dentilisin-positive and -deficient strains, FH was incubated with strain 35405 (wild type) or the CKE and CCE dentilisin mutants. Aliquots were removed at 10-min intervals for 120 min, separated by SDS-PAGE, immunoblotted, and screened with anti-FH antiserum. Only minimal cleavage of FH occurred with the dentilisin-deficient strains. In contrast, significant degradation of FH with the wild-type 35405 strain occurred by 40 min, with complete digestion by 60 min (Fig. 2B). When FH was incubated with culture supernatant derived from the wild-type strain, some cleavage of FH was observed. In contrast, no cleavage was observed when supernatant from the dentilisin-deficient strains was used (data not shown). This observation indicates that degradation of FH occurs primarily at the cell surface and is not mediated by a secreted factor. In addition, the data further establish a correlation between FH cleavage and production of dentilisin.

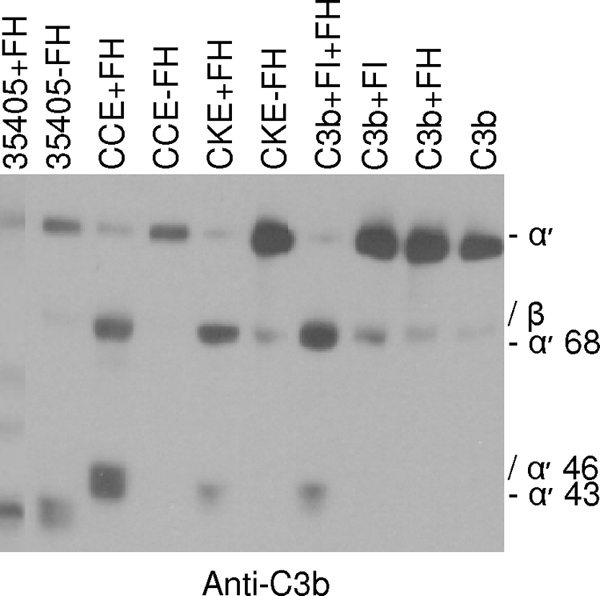

Analysis of C3b degradation by T. denticola.

To determine if degradation of C3b by T. denticola is enhanced by the binding of FH and/or influenced by dentilisin, all of the strains analyzed in this study were tested for C3b cleavage activity either with or without FH added. In an earlier report, we noted that strain 35405 cleaves C3b, albeit weakly (44). That result was confirmed here (Fig. 3). The dentilisin-deficient strains also cleaved C3b, but cleavage was strictly dependent on the presence of FH. The requirement of FH for C3b cleavage in the dentilisin-deficient strains suggests that cleavage is occurring through a factor I-mediated mechanism. Consistent with this characteristic, factor I-mediated C3b cleavage products α′43 and α′68 were readily detected when the dentilisin-deficient strains were used. These data indicate that in the dentilisin mutants, bound FH retains its factor I cofactor activity. It is important to note that the pattern of C3b cleavage products differed for the dentilisin-positive strains and the resulting pattern was not consistent with a strictly factor I-mediated mechanism. The controls for these analyses (combinations of factor I, C3b, and/or FH without cells added) all yielded the expected results (i.e., cleavage of C3b requires both FH and factor I).

FIG. 3.

Analysis of the ability of cell-bound FH and FH subfragments to serve as a cofactor for the factor I-mediated cleavage of C3b. T. denticola strain 35405 and dentilisin mutants (CCE and CKE) were incubated with or without FH, as indicated above the lanes. After addition of C3b and factor I, the samples were immunoblotted and screened with anti-C3b antiserum. Additional controls in which various combinations of purified C3b, factor I, and/or FH were combined (without cells) were performed and analyzed as described above.

Identification of residues and structural determinants within FhbB that are required for FH binding.

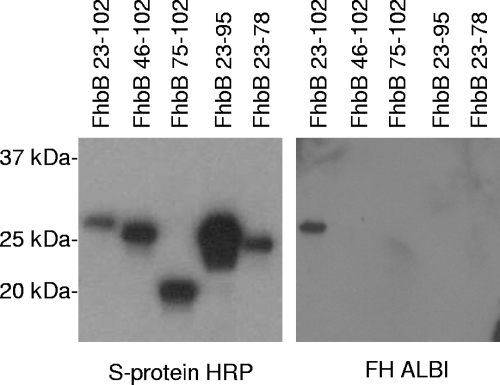

FhbB is the smallest FH binding protein identified to date, and computer-based structural modeling suggests that it is unique in terms of its predicted structure (43). To identify FhbB determinants required for FH binding, truncation and random and site-directed mutagenesis analyses were conducted. N- and C-terminal truncations of FhbB were generated by a PCR approach, and recombinant proteins were produced in E. coli as S-tagged fusion proteins. Cell lysates of induced E. coli were screened by immunoblotting with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated S protein to verify that the recombinant proteins produced were of the correct size. The cell lysates of E. coli expressing the recombinant proteins were then tested for FH binding by the ALBI approach. All FhbB truncations resulted in loss of FH binding (Fig. 4). It is noteworthy that deletion of as few as 7 aa from the C terminus of FhbB (i.e., the FhbB23-95 truncation variant) resulted in complete loss of binding. Truncation from the N terminus of the protein also resulted in loss of FH binding. As has been demonstrated for other spirochetal FH binding proteins, these analyses demonstrate that widely separable domains of FhbB are involved in and required for FH binding (1, 31, 32, 44, 47, 52, 70).

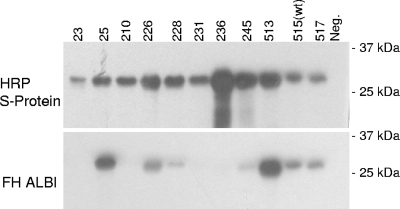

FIG. 4.

Analysis of truncated FhbB proteins for the ability to bind FH. All r-FhbB proteins were generated as N-terminally S-tagged fusions that lack the leader peptide sequence. The nomenclature assigned to each mutant is indicated and reflects the amino acid span present in the protein. Expression of r-FhbB proteins in E. coli was assessed with S protein-HRP conjugate as described in the text. FH binding by r-FhbB proteins was assessed by using the FH ALBI assay as described in the text.

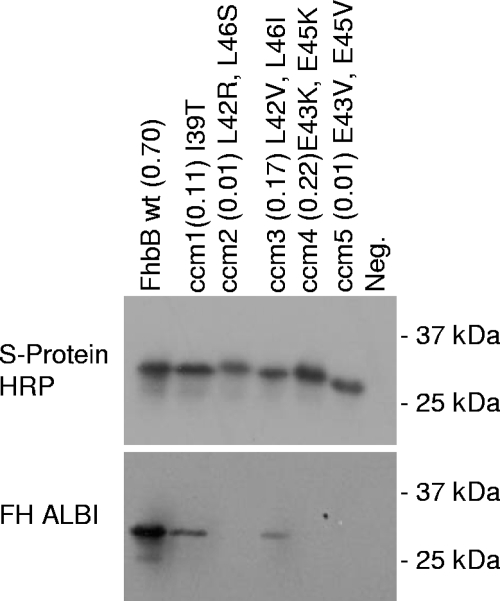

The majority of spirochetal FH binding proteins have one or more alpha helices that have a high probability of coiled-coil formation (29, 30, 32, 43, 44, 47, 52, 63). In several studies, site-directed mutagenesis analyses have demonstrated that substitutions that decrease the probability of coiled-coil formation eliminate or attenuate FH binding. Earlier analyses revealed that FhbB possesses an alpha helix spanning residues 26 through 49 that harbors the heptad repeat motif (a-g)n associated with coiled-coil formation. This alpha helix is the second extended helix of FhbB and is thus designated alpha helix 2. The coiled-coil heptad repeat element (a-g)n is defined by the presence of nonpolar residues at the a and d position of the repeat with charged residues typically present in the e and g positions. Although the predicted probability of coiled-coil formation of alpha helix 2 is high (0.7), the coiled-coil stretch is small. Hence, the role of this domain in FH binding by FhbB is not clear. To further investigate the direct or indirect influence of this alpha helix in ligand binding, specific residues were replaced through site-directed mutagenesis with amino acids with different or similar properties. Replacement of the conserved nonpolar I39 residue (residue at position a of the heptad repeat) with T coiled-coil mutant 1 (ccm1) resulted in a significant decrease in coiled-coil predicted probability (from 0.7 to 0.11) with a corresponding decrease in FH binding (Fig. 5). ccm3, which has two substitutions (L43V, L46I), also had a significant decrease in the predicted probability of coiled-coil formation and, consistent with this FH binding, was attenuated. This decrease is consistent with the drop in the predicted probability of coiled-coil formation from 0.7 to 0.17. Other site-directed mutants completely lost FH binding. Mutants ccm2 and ccm3 both have substitutions at L42 and L46 (heptad repeat positions d and a, respectively) with destabilizing residues as follows: ccm2, L42R and L46S; ccm3, L42V and L46I. The coiled-coil probability predicted by the COILS program analysis of these proteins correlates with the ALBI assay results; ccm2 has a 0.01 probability, and ccm3 has a 0.17probability. ccm4 (E43K, E45K) and ccm5 (E43V, E45V) contain mutations at the e and g positions. Both mutants lost the ability to bind FH. The sensitivity of FH binding to even minor changes in the FhbB sequence at different positions indicates that there are numerous determinants required for ligand binding.

FIG. 5.

Analysis of the binding of FH to r-FhbB proteins with site-directed mutations within the coiled-coil domain. Lysates of E. coli expressing r-FhbB with site-directed mutations (indicated above each lane) were immunoblotted and screened with S protein-HRP conjugate or used in an FH ALBI assay as described in the text. Computer-determined coiled-coil probabilities for the site-directed mutants are indicated in parentheses. These values are followed by a listing of the specific substitutions that were introduced into the proteins. The wild-type (wt) residue and position number are followed by the introduced substitution. Neg., negative control.

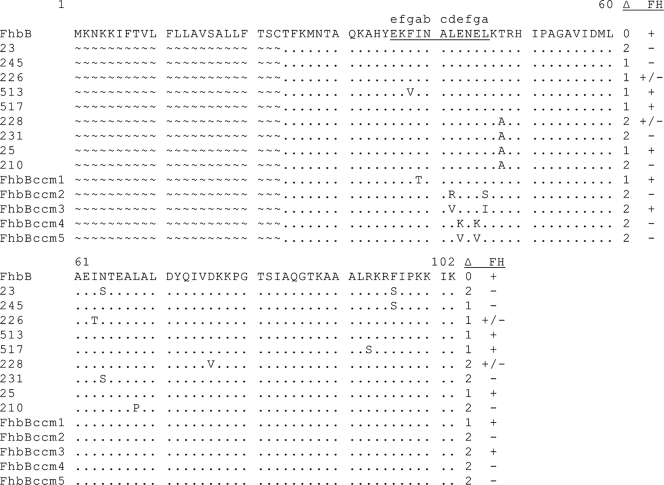

To identify other residues or domains of FhbB that may be involved in the formation and presentation of the FH binding site, random mutagenesis of FhbB was performed. Mutants were generated through PCR with a low-fidelity polymerase. All amplicons possessed tail sequences to allow cloning and expression in the pET32Ek-LIC vector. Fifty E. coli clones expressing r-FhbB (as demonstrated by immunoblot analyses with HRP-conjugated S protein) were selected for additional analyses. Of these 50, 46 produced r-FhbB that bound FH while the remaining 4 lacked FH binding ability (Fig. 6). The basis for the loss of FH binding was determined through DNA sequence analyses (Fig. 7). r-FhbB produced by clone 245 lost FH binding due to a single amino acid substitution (F96S). The r-FhbB protein of clone 231 also lost FH binding. This variant had two amino acid substitutions, T48A and N64S. Other clones that retained FH binding had the T48A substitution (clones 25 and 228), indicating that the loss of binding in clone 231 was not due to the mutation at position 48. The data suggest that position F96 is important in ligand binding. It is noteworthy that clone 517, which had an R93S substitution, did not lose ligand binding ability. While the C-terminal domains of FH binding proteins are important in ligand binding, this observation indicates that only certain residues within the C terminus are critical for FH binding. A similar finding has been reported for the OspE paralog BBL39 (47, 52). Additional residues that influence ligand binding were identified in two additional clones, 210 and 231. Both had two amino acid substitutions and had in common the replacement of residue T48 with alanine. In clone 231, the second and apparently critical substitution was N64S, while in clone 210, there was an L68P substitution. These data suggest that residues 64 and 68 influence ligand binding. In support of this, residues 64 and 68 are highly conserved among FhbB sequences (43). Only one clone, 513, was identified with a mutation in the predicted coiled-coil region (F38V substitution), and this change did not impact binding. This result is not surprising since F38 does not reside at one of the critical positions of the heptad repeat. Collectively, the truncation and mutagenesis analyses demonstrate that the interaction of FH with FhbB is complex and involves several residues and/or domains of the protein. The data presented here are consistent with the hypotheses that the determinants required for FH binding by most FH binding proteins are discontinuous and that protein structure is critical in the interaction.

FIG. 6.

Identification of r-FhbB proteins generated by random mutagenesis with altered FH binding ability. Immunoblots of cell lysates from E. coli clones expressing randomly generated r-FhbB mutant proteins were screened with HRP-conjugated S protein or utilized in FH ALBI assays (as indicated). Analyses were performed as described in the text. Neg., negative control; wt, wild type.

FIG. 7.

Sequence analysis of FhbB variants generated by random mutagenesis. The alignment presents the amino acid sequences of the random mutant forms of FhbB. The numbering is based on the FhbB sequence of the T. denticola 35405 strain. Residues that differ from those of wild-type FhbB are indicated for each mutant, while residues identical to the wild-type sequence are indicated by periods. Since the r-FhbB random mutant proteins were generated without leader peptides, sequences corresponding to the leader peptides are not shown (these positions are indicated by ∼). To the right of each protein mutant sequence, the total number of amino acid changes is indicated in the Δ column. The results of the FH binding analyses with each recombinant protein are indicated as follows: +, binding detected; +/−, weak binding; −, no binding. The computer-identified coiled-coil region is underlined, and the specific positions of the a-g coiled-coil-associated heptad repeat are shown above the wild-type sequence.

DISCUSSION

The binding of negative regulators of the complement cascade has been demonstrated to facilitate the immune evasion and/or adherence capabilities of several microbial pathogens (reviewed in reference 37). As one example, a clear correlation of FH binding, complement sensitivity, and persistence has been established for the relapsing-fever spirochetes (29, 49, 65). Regarding a role in adherence, it has been demonstrated for the pneumococci that the binding of FHL-1 is important in the interaction with epithelial and endothelial cells (23, 60). We previously demonstrated that T. denticola produces a unique 11.4-kDa protein designated FhbB that binds one or more members of the FH protein family (43, 44). It was postulated that the primary role of this interaction is to facilitate adherence to epithelial cells lining the periodontal pocket. In this study, we report new data that advance our understanding of the complexity of the interaction of complement regulatory proteins with T. denticola and which shed additional light on the role of proteases in the host-pathogen interaction.

Prior to this study, the binding of FH and/or other FH protein family members directly to r-FhbB had not been investigated. Earlier binding analyses demonstrated that T. denticola adsorbs to its surface a 50-kDa protein that is detected by anti-human FH antiserum (43). In addition, a recombinant protein consisting of the first seven short consensus repeat domains of FH (SCR1 to SCR7) also bound to T. denticola. Site-directed mutations within SCR7 eliminated binding, and the interaction was inhibited by heparin. Based on these data, it was concluded that FhbB presented in the context of viable cells bound specifically to FHL-1 (44). However, in this study we demonstrated with a pull-down assay that purified full-length r-FhbB (lacking the leader peptide) binds exclusively to FH and not to FHL-1. The specificity of the pull-down assay was demonstrated with a truncated variant of r-FhbB in which the C-terminal 24 aa residues of the protein were deleted. This variant did not interact with FH or other FH family proteins.

We speculated that the distinct results (i.e., the differing molecular weights) observed regarding the ligand bound by r-FhbB versus those seen when native FhbB is presented in the context of the whole cell are due to proteolytic degradation of FH by one or more of the T. denticola proteases. T. denticola produces numerous proteases that are important in pathogenesis as they contribute to the characteristic tissue destruction observed during periodontal disease (17, 18, 22, 40-42, 54, 64, 72). Dentilisin is the most extensively characterized of this important class of virulence factors. It is a broadly acting prolyl-phenylalanine protease (34) that has been shown to cleave several host proteins (6, 10, 16, 53, 75). To determine if dentilisin contributes to the cleavage of FH, the interaction of FH with two T. denticola dentilisin mutants and wild-type T. denticola strain 35405 was assessed. While strong binding of FH to dentilisin mutants of T. denticola was observed, consistent with our earlier study, no binding of full-length FH to the wild-type strain was observed. Instead, the wild type bound only an ∼50-kDa protein that was detected by anti-FH antiserum and thus is presumably an FH subfragment. To assess potential cleavage of FH by T. denticola over time, a time course analysis was performed. After 30 min, significant cleavage of FH was observed with wild-type strain 35405 but not with the CCE and CKE dentilisin mutants. By 50 min, FH cleavage in the presence of wild-type 35405 was nearly complete. While these results suggest that dentilisin cleaves FH, we have not definitively ruled out an indirect effect of dentilisin inactivation or possibly the participation of another T. denticola protease. Nonetheless, the data clearly indicate a correlation between the dentilisin-positive phenotype and FH cleavage. Since binding of FH is advantageous to many pathogens, as it facilitates immune evasion, it would seem counterproductive to actively degrade it. As alluded to above, tissue necrosis is a hallmark feature of periodontal disease. It is noteworthy that recent studies have shown increased binding of FH to apoptotic or necrotic cells (71). As the proteases of T. denticola begin to degrade tissue, they presumably also cleave cell-bound FH. The ability of T. denticola to bind FH cleavage products may facilitate tissue invasion and thus further the progression of periodontal disease.

We previously demonstrated that cleavage of C3b by wild-type T. denticola occurs at a significant level even in the absence of added FH, implicating, at least in part, a factor I-independent cleavage mechanism. In support of this, the cleavage pattern observed when FH was incubated with wild-type T. denticola strain 35405 (a producer of dentilisin) was atypical and not consistent with that seen for a strict factor I-mediated cleavage mechanism. To assess the overall contribution of dentilisin to C3b cleavage, C3b was incubated with wild-type and dentilisin mutant strains that were preloaded with FH. In the absence of dentilisin activity (i.e., in the mutants), C3b was readily cleaved and the signature FI-mediated cleavage pattern was observed. Hence, it is apparent that two mechanisms of cleavage are at play, one mediated by FI and the other mediated by dentilisin. Besides being able to cleave C3b, T. denticola-bound FH may also be able to directly disrupt the C3 convertase (C3bBb). Indirect evidence of this is shown in recent work by Yamazaki et al. (75). Those authors demonstrated that dentilisin-deficient strain K1 had significantly less surface deposition of iC3b than the did dentilisin-expressing wild-type strain. This suggests a decrease in C3b at the strain K1 cell surface, perhaps through perturbation of the C3 convertase by T. denticola-bound FH. Further studies with T. denticola dentilisin and/or FhbB mutants will address this issue.

In light of the unique FH-T. denticola interaction described here, we sought to determine the molecular basis of the interaction between FH and FhbB. Several approaches were applied, including FhbB truncation analyses and random and site-directed mutagenesis. Several residues and/or domains were identified that are either central to the formation and presentation of the FH binding site or are directly involved in interacting with FH itself. The truncation analyses demonstrated that ligand binding requires both the N- and C-terminal domains of the protein. This is similar to that which has been reported for FH binding proteins of the Lyme disease and relapsing-fever spirochetes (24, 30, 45, 52, 63). The random and site-directed mutation analyses identified widely separated (in terms of linear sequence) residues of FhbB that are required for FH binding. Hence, consistent with earlier analyses, it is clear that the determinants that influenced ligand binding are distributed throughout the protein and that the binding site is not a simple contiguous linear sequence element (1, 30, 32, 44, 47, 52, 63). The apparent importance of nonpolar residues within helix 2 of FhbB is noteworthy. In all of the strains of T. denticola analyzed to date, this helix in FhbB has a high predicted probability of coiled-coil formation (data not shown). FhbB differs from other FH binding proteins in that it possesses only one alpha helix with the potential to form a coiled coil. Hence, the formation of a coiled coil would, by necessity, involve an intermolecular interaction. This could conceivably occur between FhbB and its ligand or between monomers of FhbB to generate an oligomer that binds ligand. It is important to point out that direct evidence for the formation of coiled coils in FH binding proteins has not yet been provided. It is conceivable that, instead of a defined structural element being required, it is simply the periodicity of nonpolar residues within defined domains that is required for ligand binding. Such periodicity may generate a hydrophobic pocket that stabilizes the protein and allow the proper formation and presentation of the ligand binding site. The substitution mutations described above may perturb overall protein structure and thus negatively influence ligand binding.

In conclusion, the analyses presented here demonstrate that the overall interaction and outcome of FH binding to T. denticola are uniquely different from those seen with other FH binding pathogens. In addition, we demonstrate an additional role for dentilisin in the host-pathogen interaction. Future studies will focus on identification of the exact portions of FH which make up the 50-kDa FH subfragment and will seek to determine the precise role that the binding of this peptide plays in immune evasion, adherence, and/or tissue invasion.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by grants DE017401 to R.T.M. and DE013565 to J.C.F. from NIDCR.

Editor: J. B. Bliska

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 February 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alitalo, A., T. Meri, T. Chen, H. Lankinen, Z. Z. Cheng, T. S. Jokiranta, I. J. Seppala, P. Lahdenne, P. S. Hefty, D. R. Akins, and S. Meri. 2004. Lysine-dependent multipoint binding of the Borrelia burgdorferi virulence factor outer surface protein E to the C terminus of factor H. J. Immunol. 1726195-6201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alitalo, A., T. Meri, H. Lankinen, I. Seppala, P. Lahdenne, P. S. Hefty, D. Akins, and S. Meri. 2002. Complement inhibitor factor H binding to Lyme disease spirochetes is mediated by inducible expression of multiple plasmid-encoded outer surface protein E paralogs. J. Immunol. 1693847-3853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anonymous. 1987. Oral health of US adults: NIDR 1985 national survey. J. Public Health Dent. 47198-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Areschoug, T., M. Stalhammar-Carlemalm, I. Karlsosson, and G. Lindahl. 2002. Streptococcal beta protein has separate binding sites for human factor H and IgA-Fc. J. Biol. Chem. 27712642-12648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asakawa, R., H. Komatsuzawa, T. Kawai, S. Yamada, R. B. Goncalves, S. Izumi, T. Fujiwara, Y. Nakano, H. Shiba, M. A. Taubman, H. Kurihara, and M. Sugai. 2003. Outer membrane protein 100, a versatile virulence factor of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Mol. Microbiol. 501125-1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bamford, C. V., J. C. Fenno, H. F. Jenkinson, and D. Dymock. 2007. The chymotrypsin-like protease complex of Treponema denticola ATCC 35405 mediates fibrinogen adherence and degradation. Infect. Immun. 754364-4372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bian, X. L., H. T. Wang, Y. Ning, S. Y. Lee, and J. C. Fenno. 2005. Mutagenesis of a novel gene in the prcA-prtP protease locus affects expression of Treponema denticola membrane complexes. Infect. Immun. 731252-1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boackle, R. J. 1991. The interaction of salivary secretions with the human complement system—a model for the study of host defense systems on inflamed mucosal surfaces. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 2355-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boackle, R. J., K. M. Pruitt, M. S. Silverman, and J. L. Glymph, Jr. 1978. The effects of human saliva on the hemolytic activity of complement. J. Dent. Res. 57103-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chi, B., M. Qi, and H. K. Kuramitsu. 2003. Role of dentilisin in Treponema denticola epithelial cell layer penetration. Res. Microbiol. 154637-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Correia, F. F., A. R. Plummer, R. P. Ellen, C. Wyss, S. K. Boches, J. L. Galvin, B. J. Paster, and F. E. Dewhirst. 2003. Two paralogous families of a two-gene subtilisin operon are widely distributed in oral treponemes. J. Bacteriol. 1856860-6869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dave, S., A. Brooks-Walter, M. K. Pangburn, and L. S. McDaniel. 2001. PspC, a pneumococcal surface protein, binds human factor H. Infect. Immun. 693435-3437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dave, S., S. Carmicle, S. Hammerschmidt, M. K. Pangburn, and L. S. McDaniel. 2004. Dual roles of PspC, a surface protein of Streptococcus pneumoniae, in binding human secretory IgA and factor H. J. Immunol. 173471-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duthy, T. G., R. J. Ormsby, E. Giannakis, A. D. Ogunniyi, U. H. Stroeher, J. C. Paton, and D. L. Gordon. 2002. The human complement regulator factor H binds pneumococcal surface protein PspC via short consensus repeats 13 to 15. Infect. Immun. 705604-5611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellen, R. P., and V. B. Galimanas. 2005. Spirochetes at the forefront of periodontal infections. Periodontol. 2000 3813-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellen, R. P., K. S. Ko, C. M. Lo, D. A. Grove, and K. Ishihara. 2000. Insertional inactivation of the prtP gene of Treponema denticola confirms dentilisin's disruption of epithelial junctions. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotech. 2581-586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fenno, J. C., P. M. Hannam, W. K. Leung, M. Tamura, V. J. Uitto, and B. C. McBride. 1998. Cytopathic effects of the major surface protein and the chymotrypsinlike protease of Treponema denticola. Infect. Immun. 661869-1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fenno, J. C., S. Y. Lee, C. H. Bayer, and Y. Ning. 2001. The opdB locus encodes the trypsin-like peptidase activity of Treponema denticola. Infect. Immun. 696193-6200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fenno, J. C., G. W. Wong, P. M. Hannam, and B. C. McBride. 1998. Mutagenesis of outer membrane virulence determinants of the oral spirochete Treponema denticola. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 163209-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fischetti, V. A., R. D. Horstmann, and V. Pancholi. 1995. Location of the complement factor H binding site on streptococcal M6 protein. Infect. Immun. 63149-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giannakis, E., T. S. Jokiranta, D. A. Male, S. Ranganathan, R. J. Ormsby, V. A. Fischetti, C. Mold, and D. L. Gordon. 2003. A common site within factor H SCR7 responsible for binding heparin, C-reactive protein and streptococcal M protein. Eur. J. Immunol. 33962-969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grenier, D., V. J. Uitto, and B. C. McBride. 1990. Cellular location of a Treponema denticola chymotrypsinlike protease and importance of the protease in migration through the basement membrane. Infect. Immun. 58347-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammerschmidt, S., V. Agarwal, A. Kunert, S. Haelbich, C. Skerka, and P. Zipfel. 2007. The host immune regulator factor H interacts via two contact sites with the PspC protein of Streptococcus pneumoniae and mediates adhesion to host epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 1785848-5858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hartmann, K., C. Corvey, C. Skerka, M. Kirschfink, M. Karas, V. Brade, J. C. Miller, B. Stevenson, R. Wallich, P. F. Zipfel, and P. Kraiczy. 2006. Functional characterization of BbCRASP-2, a distinct outer membrane protein of Borrelia burgdorferi that binds host complement regulators factor H and FHL-1. Mol. Microbiol. 611220-1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hashimoto, M., S. Ogawa, Y. Asai, Y. Takai, and T. Ogawa. 2003. Binding of Porphyromonas gingivalis fimbriae to Treponema denticola dentilisin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 226267-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hellwage, J., T. Meri, T. Heikkila, A. Alitalo, J. Panelius, P. Lahdenne, I. J. T. Seppala, and S. Meri. 2001. The complement regulator factor H binds to the surface protein OspE of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Biol. Chem. 2768427-8435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herzberger, P., C. Siegel, C. Skerka, V. Fingerle, U. Schulte-Spechtel, A. van Dam, B. Wilske, V. Brade, P. F. Zipfel, R. Wallich, and P. Kraiczy. 2007. Human pathogenic Borrelia spielmanii sp. nov. resists complement-mediated killing by direct binding of immune regulators factor H and factor H-like protein 1. Infect. Immun. 754817-4825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horstmann, R. D., H. J. Sievertsen, J. Knobloch, and V. A. Fischetti. 1988. Antiphagocytic activity of streptococcal M protein: selective binding of complement control protein factor H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 851657-1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hovis, K. M., J. C. Freedman, H. Zhang, J. L. Forbes, and R. T. Marconi. 2008. Identification of an antiparallel coiled-coil/loop domain required for ligand binding by the Borrelia hermsii FhbA protein: additional evidence for the role of FhbA in the host-pathogen interaction. Infect. Immun. 762113-2122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hovis, K. M., J. P. Jones, T. Sadlon, G. Raval, D. L. Gordon, and R. T. Marconi. 2006. Molecular analyses of the interaction of Borrelia hermsii FhbA with the complement regulatory proteins factor H and factor H-like protein 1. Infect. Immun. 742007-2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hovis, K. M., J. V. McDowell, L. Griffin, and R. T. Marconi. 2004. Identification and characterization of a linear-plasmid-encoded factor H-binding protein (FhbA) of the relapsing fever spirochete Borrelia hermsii. J. Bacteriol. 1862612-2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hovis, K. M., M. E. Schriefer, S. Bahlani, and R. T. Marconi. 2006. Immunological and molecular analyses of the Borrelia hermsii factor H and factor H-like protein 1 binding protein, FhbA: demonstration of its utility as a diagnostic marker and epidemiological tool for tick-borne relapsing fever. Infect. Immun. 744519-4529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ishihara, K., H. Kuramitsu, and K. Okuda. 2004. A 43-kDa protein of Treponema denticola is essential for dentilisin activity. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 232181-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ishihara, K., T. Miura, H. K. Kuramitsu, and K. Okuda. 1996. Characterization of the Treponema denticola prtP gene encoding a prolyl-phenylalanine-specific protease (dentilisin). Infect. Immun. 645178-5186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Józsi, M., and P. F. Zipfel. 2008. Factor H family proteins and human diseases. Trends Immunol. 29380-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kraiczy, P., J. Hellwage, C. Skerka, H. Becker, M. Kirschfink, M. S. Simon, V. Brade, P. F. Zipfel, and R. Wallich. 2004. Complement resistance of Borrelia burgdorferi correlates with the expression of BbCRASP-1, a novel linear plasmid-encoded surface protein that interacts with human factor H and FHL-1 and is unrelated to Erp proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2792421-2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kraiczy, P., and R. Würzner. 2006. Complement escape of human pathogenic bacteria by acquisition of complement regulators. Mol. Immunol. 4331-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee, S. Y., X. L. Bian, G. W. Wong, P. M. Hannam, B. C. McBride, and J. C. Fenno. 2002. Cleavage of Treponema denticola PrcA polypeptide to yield protease complex-associated proteins Prca1 and Prca2 is dependent on PrtP. J. Bacteriol. 1843864-3870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lupas, A., M. Van Dyke, and J. Stock. 1991. Predicting coiled coils from protein sequences. Science 2521162-1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mäkinen, K. K., and P. L. Mäkinen. 1996. The peptidolytic capacity of the spirochete system. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 1851-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mäkinen, K. K., P. L. Mäkinen, and S. A. Syed. 1992. Purification and substrate specificity of an endopeptidase from the human oral spirochete Treponema denticola ATCC 35405, active on furylacryloyl-Leu-Gly-Pro-Ala and bradykinin. J. Biol. Chem. 26714285-14293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mäkinen, P. L., K. K. Mäkinen, and S. A. Syed. 1994. An endo-acting proline-specific oligopeptidase from Treponema denticola ATCC 35405: evidence of hydrolysis of human bioactive peptides. Infect. Immun. 624938-4947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McDowell, J. V., J. Frederick, L. Stamm, and R. T. Marconi. 2007. Identification of the gene encoding the FhbB protein of Treponema denticola, a highly unique factor H-like protein 1 binding protein. Infect. Immun. 751050-1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McDowell, J. V., M. E. Harlin, E. A. Rogers, and R. T. Marconi. 2005. Putative coiled-coil structural elements of the BBA68 protein of Lyme disease spirochetes are required for formation of its factor H binding site. J. Bacteriol. 1871317-1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McDowell, J. V., K. M. Hovis, H. Zhang, E. Tran, J. Lankford, and R. T. Marconi. 2006. Evidence that the BBA68 protein (BbCRASP-1) of the Lyme disease spirochetes does not contribute to factor H-mediated immune evasion in humans and other animals. Infect. Immun. 743030-3034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McDowell, J. V., E. Tran, D. Hamilton, J. Wolfgang, K. Miller, and R. T. Marconi. 2003. Analysis of the ability of spirochete species associated with relapsing fever, avian borreliosis, and epizootic bovine abortion to bind factor H and cleave c3b. J. Clin. Microbiol. 413905-3910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McDowell, J. V., J. Wolfgang, L. Senty, C. M. Sundy, M. J. Noto, and R. T. Marconi. 2004. Demonstration of the involvement of outer surface protein E coiled coil structural domains and higher order structural elements in the binding of infection-induced antibody and the complement-regulatory protein, factor H. J. Immunol. 1737471-7480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McDowell, J. V., J. Wolfgang, E. Tran, M. S. Metts, D. Hamilton, and R. T. Marconi. 2003. Comprehensive analysis of the factor H binding capabilities of Borrelia species associated with Lyme disease: delineation of two distinct classes of factor H binding proteins. Infect. Immun. 713597-3602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meri, T., S. J. Cutler, A. M. Blom, S. Meri, and T. S. Jokiranta. 2006. Relapsing fever spirochetes Borrelia recurrentis and B. duttonii acquire complement regulators C4b-binding protein and factor H. Infect. Immun. 744157-4163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meri, T., A. Hartmann, D. Lenk, R. Eck, R. Wurzner, J. Hellwage, S. Meri, and P. F. Zipfel. 2002. The yeast Candida albicans binds complement regulators factor H and FHL-1. Infect. Immun. 705185-5192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meri, T., T. S. Jokiranta, J. Hellwage, A. Bialonski, P. F. Zipfel, and S. Meri. 2002. Onchocerca volvulus microfilariae avoid complement attack by direct binding of factor H. J. Infect. Dis. 1851786-1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Metts, M. S., J. V. McDowell, M. Theisen, P. R. Hansen, and R. T. Marconi. 2003. Analysis of the OspE determinants involved in binding of factor H and OspE-targeting antibodies elicited during Borrelia burgdorferi infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 713587-3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miyamoto, M., K. Ishihara, and K. Okuda. 2006. The Treponema denticola surface protease dentilisin degrades interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor alpha. Infect. Immun. 742462-2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ohta, K., K. K. Mäkinen, and W. J. Loesche. 1986. Purification and characterization of an enzyme produced by Treponema denticola capable of hydrolyzing synthetic trypsin substrates. Infect. Immun. 53213-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pandiripally, V., L. Wei, C. Skerka, P. F. Zipfel, and D. Cue. 2003. Recruitment of complement factor H-like protein 1 promotes intracellular invasion by group A streptococci. Infect. Immun. 717119-7128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pangburn, M. K., R. D. Schreiber, and H. J. Müller-Eberhard. 1977. Human complement C3b inactivator: isolation, characterization, and demonstration of an absolute requirement for the serum protein β1H for cleavage of C3b and C4b in solution. J. Exp. Med. 146257-270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Paster, B. J., S. K. Boches, J. L. Galvin, R. E. Ericson, C. N. Lau, V. A. Levanos, A. Sahasrabudhe, and F. E. Dewhirst. 2001. Bacterial diversity in human subgingival plaque. J. Bacteriol. 1833770-3783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Paster, B. J., I. Olsen, J. A. Aas, and F. E. Dewhirst. 2006. The breadth of bacterial diversity in the human periodontal pocket and other oral sites. Periodontol. 2000 4280-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Poltermann, S., A. Kunert, M. von der Heide, R. Eck, A. Hartmann, and P. F. Zipfel. 2007. Gpm1p is a factor H, FHL-1 and plasminogen-binding surface protein of Candida albicans. J. Biol. Chem. 28237537-37544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Quin, L. R., C. Onwubiko, Q. C. Moore, M. F. Mills, L. S. McDaniel, and S. Carmicle. 2007. Factor H binding to PspC of Streptococcus pneumoniae increases adherence to human cell lines in vitro and enhances invasion of mouse lungs in vivo. Infect. Immun. 754082-4087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ram, S., D. P. McQuillen, S. Gulati, C. Elkins, M. K. Pangburn, and P. A. Rice. 1998. Binding of complement factor H to loop 5 of porin protein 1A: a molecular mechanism of serum resistance of nonsialylated Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Exp. Med. 188671-680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ram, S., A. K. Sharma, and S. D. Simpson. 1998. A novel sialic acid binding site on factor H mediates serum resistance of non-sialylated Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Exp. Med. 187743-752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rogers, E. A., and R. T. Marconi. 2007. Delineation of species-specific binding properties of the CspZ protein (BBH06) of Lyme disease spirochetes: evidence for new contributions to the pathogenesis of Borrelia spp. Infect. Immun. 755272-5281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rosen, G., R. Naor, E. Rahamim, R. Yishai, and M. N. Sela. 1995. Proteases of Treponema denticola outer sheath and extracellular vesicles. Infect. Immun. 633973-3979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rossmann, E., P. Kraiczy, P. Herzberger, C. Skerka, M. Kirschfink, M. M. Simon, P. F. Zipfel, and R. Wallich. 2007. Dual binding specificity of a Borrelia hermsii-associated complement regulator-acquiring surface protein for factor H and plasminogen discloses a putative virulence factor of relapsing fever spirochetes. J. Immunol. 1787292-7301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ruddy, S., and K. F. Austen. 1969. C3 inactivator of man. I. Hemolytic measurement by the inactivation of cell-bound C3. J. Immunol. 102533-543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ruddy, S., and K. F. Austen. 1971. C3b inactivator of man. II. Fragments produced by C3b inactivator cleavage of cell-bound or fluid phase C3b. J. Immunol. 107742-750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schenkein, H. A., and R. J. Genco. 1977. Gingival fluid and serum in periodontal diseases. I. Quantitative study of immunoglobulins, complement components, and other plasma proteins. J. Periodontol. 48772-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Seib, K. L., D. Serruto, F. Oriente, I. Delany, J. Adu-Bobie, D. Veggi, B. Arico, R. Rappuoli, and M. Pizza. 2009. Factor H-binding protein is important for meningococcal survival in human whole blood and serum, and in the presence of the antimicrobial peptide LL-37. Infect. Immun. 77292-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Siegel, C., J. Schreiber, K. Haupt, C. Skerka, V. Brade, M. M. Simon, B. Stevenson, R. Wallich, P. F. Zipfel, and P. Kraiczy. 2008. Deciphering the ligand-binding sites in the Borrelia burgdorferi complement regulator-acquiring surface protein 2 (BbCRASP-2) required for interactions with the human immune regulators factor H and factor H-Like protein 1. J. Biol. Chem. 28334855-34863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Trouw, L. A., A. A. Bengtsson, K. A. Gelderman, B. Dahlback, G. Sturfelt, and A. M. Blom. 2007. C4b-binding protein and factor H compensate for the loss of membrane-bound complement inhibitors to protect apoptotic cells against excessive complement attack. J. Biol. Chem. 28228540-28548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Uitto, V. J., D. Grenier, E. C. Chan, and B. C. McBride. 1988. Isolation of a chymotrypsinlike enzyme from Treponema denticola. Infect. Immun. 562717-2722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Van Dyke, T. E., and C. N. Serhan. 2003. Resolution of inflammation: a new paradigm for the pathogenesis of periodontal diseases. J. Dent. Res. 8282-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Whaley, K., and S. Ruddy. 1976. Modulation of the alternative complement pathways by β1H globulin. J. Exp. Med. 1441147-1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yamazaki, T., M. Miyamoto, S. Yamada, K. Okuda, and K. Ishihara. 2006. Surface protease of Treponema denticola hydrolyzes C3 and influences function of polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Microbes Infect. 81758-1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zipfel, P. F., C. Skerka, J. Hellwage, S. T. Jokiranta, S. Meri, V. Brade, P. Kraiczy, M. Noris, and G. Remuzzi. 2002. Factor H family proteins: on complement, microbes and human diseases. Biochem. Soc Trans. 30971-978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]