Abstract

Serotype-specific antibodies to pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide (PPS) are a critical component of vaccine-mediated immunity to Streptococcus pneumoniae. In this study, we investigated the in vitro opsonophagocytic activities of three PPS-specific mouse immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibodies (MAbs), 1E2, 5F6, and 7A9, and determined their in vivo efficacies against intranasal challenge with WU2, a serotype 3 pneumococcal strain, in normal and immunodeficient mice. The MAbs had different in vitro activities in a pneumococcal killing assay: 7A9 enhanced killing by mouse neutrophils and J774 cells in the presence of a complement source, whereas 5F6 promoted killing in the absence, but not the presence, of complement, and 1E2 did not promote killing under any conditions. Nonetheless, all three MAbs protected normal and complement component 3-deficient mice from a lethal intranasal challenge with WU2 in passive-immunization experiments in which 10 μg of the MAbs were administered intraperitoneally before intranasal challenge. In contrast, only 1E2 protected Fcγ receptor IIB knockout (FcγRIIB KO) mice and mice that were depleted of neutrophils with the MAb RB6, whereas 7A9 and 5F6 required neutrophils and FcγRIIB to mediate protection. Conversely, 7A9 and 5F6 protected FcγR KO mice, but 1E2 did not. Hence, the efficacy of 1E2 required an activating FcγR(s), whereas 5F6 and 7A9 required the inhibitory FcγR (FcγRIIB). Taken together, our data demonstrate that both MAbs that do and do not promote pneumococcal killing in vitro can mediate protection in vivo, although their efficacies depend on different host receptors and/or components.

Pneumococcal infections are responsible for 700,000 to 1,000,000 deaths per year in children, with the greatest mortality in children with pneumonia in developing countries (86). In the developed world, pneumococcal pneumonia remains a significant problem, as it is still the most common cause of community-acquired pneumonia and of mortality in the setting of pneumonia in the United States (59). Treatment of pneumococcal pneumonia with antimicrobial agents is complicated by antibiotic resistance, which has increased among pneumococcal isolates (22, 77), and other problems associated with antibiotic use, underscoring the importance of pneumococcal vaccination in preventing pneumococcal disease. The ability of the 23-valent pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide (PPS) vaccine, in use in the United States since 1980, to protect against pneumonia remains uncertain (34, 51, 53, 87). However, there is ample evidence that use of the heptavalent PPS conjugate vaccine in infants and young children, which began in 2000, has contributed to a reduction in pneumococcal disease in adults and children (18, 30, 43).

At present, herd immunity stemming from use of the heptavalent PPS conjugate vaccine is an important component of prevention of pneumococcal disease on a population scale. However, available data suggest that herd immunity may fail to protect immunocompromised individuals (1, 42, 45), a patient population that is at increased risk for disease. In addition, the emergence of disease caused by nonvaccine serotypes (31) suggests that significant gaps remain in our ability to control pneumococcal disease. For example, there has been an increase in the incidence of necrotizing pneumonia and empyema in children due to serotype 3 (6, 16). Serotype 3 causes disease in both adults and children and has been independently associated with an increased risk of death compared to other pneumococcal serotypes (48). The currently available heptavalent PPS conjugate vaccine that is used for children in the United States does not include serotype 3. Although conjugates that include additional pneumococcal-polysaccharide serotypes, including serotype 3, are expected to be introduced in the near future (58, 75), an investigational conjugate containing serotype 3 polysaccharide failed to induce protection against this serotype in African children (62).

PPS vaccines protect against pneumococcal disease by eliciting serotype-specific opsonophagocytic immunoglobulin G (IgG) (66). The efficacy of such antibodies against invasive pneumococcal disease stems from their ability to promote pneumococcal opsonization and killing (3, 36). Currently, measurement of the opsonophagocytic (opsonic) activities of vaccine-elicited antibodies in pneumococcal killing and/or phagocytosis assays with effector cells in vitro is considered the gold standard for estimating pneumococcal vaccine efficacy (7, 33, 67). The importance of opsonic antibodies for protection against pneumococcal disease has been validated in animal models (49, 71). However, human PPS-specific antibodies that do not promote opsonophagocytosis in vitro have also been shown to be protective against pneumococcal infection in mice (13, 25). In this study, we investigated the biological activity and the mechanism by which mouse monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) to serotype 3 protect against intranasal (i.n.) infection with serotype 3 in mice. Our results show that both opsonic and nonopsonic MAbs mediate protection against lethal i.n. challenge.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

S. pneumoniae, PPS, and immunogens.

The serotype 3 Streptococcus pneumoniae strain WU2 (kindly provided by Susan Hollingshead, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL), was used in this study. WU2 has been used extensively in studies of antibody immunity to pneumococci (44, 64, 84, 85). Two other serotype 3 strains, ATCC (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) 6303 and A66 (kindly provided by David Briles, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL), and a serotype 8 strain, ATCC 6308, were also used in some experiments. Pneumococci were grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB) (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) to mid-log phase at 37°C in 5% CO2 as described previously (69). Aliquots were frozen in TSB/10% glycerol at −80°C for use as needed. Purified PPS3 (6303) was obtained from the ATCC. PPS3-TT, the conjugate used for mouse immunization, consisting of PPS3 (6303) conjugated to tetanus toxoid (TT), was described previously (19).

Mice.

C57BL/6 mice (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD) were used for immunizations and for pneumococcal protection studies. Complement component 3 knockout (C3 KO) (88), Fc receptor gamma chain (FcγR) KO (81), and FcγRIIB KO (82) mice, each on the C57BL/6 background, were bred by the Institute for Animal Studies at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine (AECOM) in accordance with the rules and regulations of animal welfare at AECOM.

Mouse immunizations, serologic studies, and generation of MAbs.

C57BL/6 mice were vaccinated subcutaneously at the base of the tail with a 100-μl injection of 2.5 μg of PPS3-TT with alhydrogel (Brenntag Biosector, Frederikssund, Denmark) as described previously (85) and were revaccinated on days 14 and 28. Blood samples were obtained from the retro-orbital sinus; the sera were separated, and levels of antibodies to PPS3 were determined by an antigen capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (see below). The splenocytes of mice with high titers of antibody to PPS3 were isolated and fused with the mouse myeloma cell line NSO to produce hybridomas, as previously described (69). The supernatant fluids from the resulting hybridoma cells were screened by ELISA for PPS3 binding. NSO cells and hybridoma cells were maintained in medium containing Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Mediatech, Herndon, VA) supplemented with 10% NCTC-109 (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, UT), and 1% nonessential amino acids (Mediatech, Manassas, VA).

ELISA.

The binding of MAbs to PPS3 was determined by ELISA as previously described (85). Briefly, 96-well polystyrene ELISA plates (Corning Glass Works, Corning, NY) were coated with 10 μg/ml PPS3 (6303) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Cambrex, Walkersville, MD) for 3 h at room temperature, followed by blocking with 1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO)-PBS overnight at 4°C. After the plates were washed with PBS-0.05% Tween 20 (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) using a SkanWasher 400 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA), the titers of the antibodies were determined, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. After further washing, the plates were incubated for 1 h with a 1:1,000 dilution of alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse Ig (H+L) (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL). Binding was detected with p-nitrophenyl phosphate substrate (Sigma) in diethanolamine buffer (pH 9.8). Optical densities (ODs) were measured at 405 nm with a Sunrise absorbance reader (Tecan US, Durham, NC). Antibody levels were defined as the average OD of duplicate wells of the samples minus the background. The background for each plate was defined as the OD of the detection antibody alone.

Nucleic acid sequence analysis.

Mouse total mRNA was isolated from the hybridomas with TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the protocol provided and purified with an RNA purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Antibody VH (heavy-chain) and VL (light-chain) first-strand cDNAs were generated by reverse transcription of purified total mRNA using a First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Novagen, La Jolla, CA) and the 3′-constant-region primer of the mouse Ig-Primer Set from Novagen. The Ig-Primer Set is designed for amplification of immunoglobulin variable-region cDNAs from mouse sources. The MAb VH and VL regions were then amplified with a NovaTaq Hot Start Master Mix kit (Novagen) and the mouse Ig-Primer Set. After being identified with a 2% agarose gel (Cambrex) and purified with a QIAquick Gel Extraction kit from Qiagen, the oligonucleotides that were generated were sequenced at the DNA-sequencing facility of AECOM. Variable-region sequences were compared to the database of mouse immunoglobulin sequences using VBASE2 DNA-plot (http://www.vbase2.org/) (65) and a BLAST search (National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST).

Epitope specificity.

A competitive-binding ELISA (19) was used to compare the binding of the MAbs. MAb 5F6 was biotinylated as follows. A 0.1 M solution of EZ-link sulfo-NHS-LC biotin (Pierce, Rockford, IL) with N,N-dimethylformamide (Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI) was prepared. Next, 1 mg of biotin was slowly added to 2 mg antibody while the solution was simultaneously vortexed. After a 1-h reaction at room temperature, the biotinylated MAb was dialyzed overnight in PBS. The concentration of biotinylated MAb was determined by ELISA; binding studies with PPS3 in the solid phase showed that biotinylated MAb binding was similar to that of unlabeled MAb (data not shown). The ELISA binding curves of each MAb on PPS3-coated plates were used to determine the concentration of MAb resulting in 50% saturation, and this concentration was used as the fixed amount of the antibody. The fixed amount of unlabeled MAb 1E2 or 7A9 was added to serial dilutions of the biotinylated MAb 5F6 and incubated with PPS3-coated plates. In addition, the reverse assay was also performed: a fixed amount of the biotinylated MAb 5F6 was added to serial dilutions of the unlabeled MAb 1E2 or 7A9 and incubated with PPS3-coated plates. The binding of the biotinylated 5F6 was detected with horseradish peroxidase-labeled streptavidin (Zymed, San Francisco, CA) and developed with peroxidase substrate (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD). ODs were recorded at 450 nm.

Immunochemical assays.

Capsular quellung-type reactions were evaluated by differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy as described previously (40). A Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope fitted with a Nikon confocal microscope C1 system and DIC optics was used. The interactions between MAbs and PPS3 were quantified by monitoring the perturbation of tryptophan fluorescence that typically accompanies antibody binding. All titrations were performed on a Spex (Edison, NJ) 111 spectrofluorometer using photon counting. Binding was measured by adding small aliquots of PPS3 dissolved in PBS to a solution of each MAb (25 μg/ml) in PBS. The fluorescence intensity was measured using 284-nm excitation and 341-nm emission wavelengths and right-angle geometry. Five successive 10-s integration periods were averaged for each data point. The fluorescence yield was constant over this time period. The background fluorescence from a buffer blank was subtracted from all measurements. Plots of percent change in fluorescence on addition of polysaccharide versus the PPS3 concentration were constructed. The apparent Kd (dissociation constant) in molar units was determined from the plots as the PPS3 concentration at one-half the maximum change in fluorescence that was estimated by computer-aided fit to a hyperbolic binding isotherm (SigmaPlot; Systat Software Inc., Richmond, CA). The PPS molar concentration was calculated by assuming a repeat unit molecular weight of 1,000 g/mol.

Opsonophagocytic-killing assays.

The capacities of PPS3-binding MAbs produced as described above to promote effector cell opsonophagocytosis of serotype 3 pneumococcus was determined using three assays.

(i) Assay 1: killing assay with mouse neutrophils (14).

Mouse neutrophils were isolated from normal wild-type (WT) (C57BL/6) mouse whole blood by using a Ficoll-Paque gradient (90). Then, 2 × 103 CFU of serotype 3 pneumococcus (WU2) were combined with 40 μl of diluted MAbs, and the volume was adjusted to 50 μl with Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS). After incubation for 30 min at room temperature, 40 μl of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) at a concentration of 2 × 107 cells/ml, with or without 10 μl of mouse complement serum (Innovative Research, Novi, MI) used as a complement source, was added, and the mixture was allowed to incubate for 1 h at 37°C with shaking. After incubation, HBSS was added to the samples to bring the volume up to 1 ml, and immediately thereafter, 50 μl of the solution was plated onto blood agar in triplicate. The plates were incubated overnight at 37°C and 5% CO2, and the colonies were counted. To validate the results obtained with another effector cell type, the murine macrophage-like cell line J774 (ATCC; BALB/c; haplotype H-2d) was also used (4). A 500:1 effector-to-target cell (E:T) ratio of PMNs to pneumococci has previously been reported to be effective for opsonic killing of pneumococci (27). In addition to this ratio, other ratios, namely, 50:1, 5:1, and 0.5:1, were also used with J774.

(ii) Assay 2: killing assay based on the standard assay used with human sera (54, 68).

MAbs were serially diluted (1:4), and then 10-μl MAb aliquots were added to each well of a 96-well round-bottom plate as described for the standard opsonophagocytosis assay that is commonly used in the pneumococcal field (56). The MAbs were diluted with opsonophagocytosis buffer (OB) (veronal buffer with Ca2+, Mg2+, and 0.1% gelatin). Then, 20 μl of the bacterial suspension with 1,000 CFU diluted in OB was added to each well. The assay plate was then incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 15 min. Then, 10 μl of mouse complement serum (or OB as a control) and 4 × 105 (in 40 μl of OB) effector cells (PMNs or J774 cells) were added. The plate was then incubated at 37°C for 45 min with horizontal shaking (220 rpm) in room air. Aliquots from each well (20 μl) were added to 180 μl OB, and 50-μl diluted aliquots were plated onto Trypticase soy agar-5% sheep blood plates (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) as described previously (13) and incubated for 18 h at 37°C in 5% CO2, and the number of CFU was determined.

(iii) Assay 3: fluorescence-activated cell sorter phagocytosis (5).

A third method that measures phagocytosis was used to confirm our results from assays 1 and 2 with a different approach. Briefly, bacteria (WU2) were heat killed at 65°C for 1 h (89) and labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) (35). MAbs were serially diluted (1:2) eight times in OB (as described above), 40 μl of each dilution was added per well in a 96-well round-bottom plate, and 4 ×106 CFU per well of fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled bacteria (40 μl) were added. The plate was incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Then, 4 ×105 J774 cells (80 μl) were added, and the plate was incubated at 37°C for 30 min. After the reaction was stopped with ice-cold OB, the plate was spun for 10 min at 2,160 × g. The cells were resuspended and analyzed with a FACSCalibur cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). J774 cells were gated on forward and side scatter. The amount of phagocytosis was defined as the percentage of cells within the gated population demonstrating a fluorescence level of >10. All samples were run in duplicate.

Mouse i.n. challenge experiments.

Mouse challenge experiments were performed by i.n. infection of normal (WT; C57BL/6), neutrophil-depleted, Fc receptor-deficient, and complement-deficient mouse strains. FcγR KO and FcγRIIB KO mice on the C57BL/6 background were used as models of activating FcγRI, FcγRIII, and FcγRIV and inhibitory FcγRIIB deficiency (57), respectively. C3 KO mice on the C57BL/6 background were used as models of total complement pathway deficiency (80). For all experiments with KO mice, WT (C57BL/6) mice were used as the control. I.n. challenge and MAb administration were performed as follows. Ten micrograms (a dose of 0.1 μg was also used in some studies, as indicated) of purified MAb was diluted in 100 μl sterile PBS and given intraperitoneally (i.p.) (19) to mice 2 h before infection with 108 serotype 3 pneumococci (WU2). The pneumococci were thawed immediately before use, diluted to the desired concentration in TSB, and placed on ice. The mice were minimally anesthetized with isoflurane (Henry Schein, Melville, NY) using an inhalation anesthesia system (Vetequip, Pleasanton, CA) and inoculated with 108 CFU of pneumococci in 40 μl of TSB by applying 20 μl to the opening of each nare by pipette. The mice were held upright to ensure adequate involuntary inhalation into the alveolar spaces. Once aspiration was complete and the mice were regaining consciousness, they were placed back in their cages. A mouse MAb to Cryptococcus neoformans GXM (2H1; kindly provided by Arturo Casadevall, AECOM) was initially used as an isotype control MAb (as it did not bind PPS3). However, since there was no difference in the survival rates of 2H1- and PBS-treated mice, PBS was used as a control in subsequent experiments. To test the serotype specificities of the MAbs, they were used in a passive-protection experiment against serotype 8 pneumococcus (ATCC 6308). For this experiment, a serotype 8 capsular-polysaccharide-specific IgG1 MAb, 31B12, produced in our laboratory was also used as a positive control in the 6308 i.n. challenge studies. The number of live bacteria in the inoculum was confirmed by counting CFU on blood agar plates immediately before and after the mouse inoculations. The mice were monitored twice daily for survival. The number of mice used in each experiment is indicated in the figure legends.

Mouse peripheral neutrophil or complement C3 depletion.

For neutrophil depletion, 6- to 8-week-old female WT (C57BL/6) or C3 KO mice were injected with the rat MAb RB6-8C5 (RB6) i.p. as described previously (47). RB6 was purified from ascites fluid (kindly provided by Marta Feldmesser, AECOM). Rat IgG (rIgG) (Sigma) was used as an isotype control. RB6 or rIgG (25 μg) was administered in 100 μl of sterile PBS 18 h before infection. This dose of RB6 has been shown to induce neutrophil, but not macrophage, depletion (50, 78). The extent of neutrophil depletion was determined 18 h after RB6 administration by counting the total white blood cells in blood diluted 1:20 in Turk's solution, using a hemacytometer. White blood cell differential counts were obtained from blood smears stained with the Hema3 system (Fisher Scientific, Middletown, VA) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. For complement C3 depletion, 6- to 8-week-old female WT mice were treated i.p. with cobra venom factor (CVF) (Quidel, San Diego, CA) as previously described (83). Mice that received CVF were given three injections of 5 μg CVF diluted in 200 μl of sterile PBS 28, 24, and 4 h prior to infection.

Statistical analysis.

Mouse survival was evaluated statistically by Kaplan-Meier plot and the log rank test (19, 69). Comparisons of the effects of the MAbs in the opsonophagocytosis assays were performed with an unpaired t test. The numbers of blood and lung CFU were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test to compare treatment groups. All statistical analyses were performed using Prism (v.5.02 for Windows; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

MAbs and nucleic acid sequence analysis.

Three IgG1(κ) MAbs,1E2, 5F6, and 7A9, isolated from the fusion described above are reported here. The immunoglobulin gene segments used by the MAbs are shown in Table 1. 7A9 uses VH gene element VH5 (V7183) and no DH gene element, whereas 1E2 and 5F6 use the same VH1 (VJ558) gene element, but their DH and JH gene segment use differs. The CDR1 and CDR2 regions of 1E2 and 5F6 had a few amino acid differences compared with their closest germ line genes (Table 2). 5F6 had a higher-level somatic mutation (5 amino acids) than 1E2 (2 amino acids) in the CDR1 and CDR2 regions.

TABLE 1.

Mouse VH and VL gene segments used by MAbs 1E2, 5F6, and 7A9 to PPS-3

TABLE 2.

Complementarity-determining region (CDR) sequences of the variable-region heavy chains of MAbs to PPS3

| MAb | Amino acid sequencea

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| CDR1 | CDR2 | CDR3 | |

| Germ line | SYWIN | NIYPSDSYTNYNQKFKD | |

| 1E2 | ---L- | -------------T--- | EKELLWVRRW |

| 5F6 | ----- | V-D----E-H---M--- | RGDDGYTPAW |

The amino acid sequences of the MAbs 1E2 and 5F6 were compared to the closest germ line amino acid sequences. The dashes represent homology. The nucleic acid translation was performed by the BCM Search Launcher program (Human Genome Sequencing Center, Baylor College of Medicine). CDR, complementarity-determining region.

Specificities and binding patterns of MAbs.

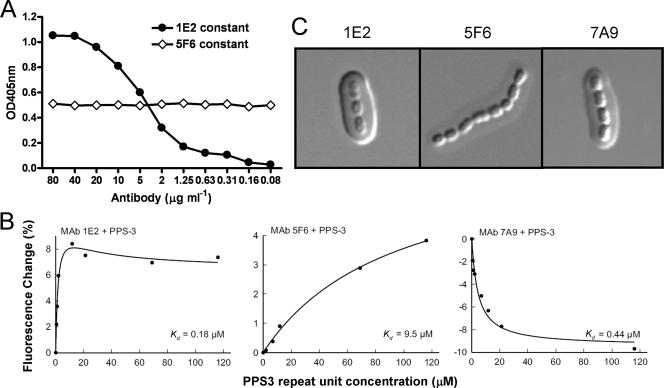

1E2, 5F6, and 7A9 each reacted with PPS3 without detectable binding to cell wall polysaccharide or other PPS serotypes by ELISA (data not shown). Competition ELISAs showed that the PPS3 binding of 5F6 was not altered by the addition of the others, suggesting that it binds a separate, nonoverlapping determinant. Figure 1A shows the result of the competition ELISA between 1E2 and 5F6 and is presented as representative of other competition ELISA results. Increasing concentrations of biotinylated 5F6 in the presence of a constant concentration of 1E2 resulted in an increase in the OD similar to that observed without 1E2 (meaning that the binding of 5F6 to PPS was not impeded by the addition of 1E2), and incubation of a constant concentration of biotinylated 5F6 with increasing concentrations of 1E2 did not result in a change in OD (meaning that the binding of 5F6 was not prevented by 1E2). This indicates that 1E2 does not compete with 5F6 for PPS3 binding. A similar result with 7A9 indicated that 7A9 also binds a different determinant than 5F6.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the PPS3 specificities of 1E2 and 5F6. (A) Competition ELISA. The circles represent the signal obtained when a fixed concentration of the unlabeled 1E2 was added to serial dilutions of 5F6-biotin. The diamonds represent the signal obtained when a fixed concentration of 5F6-biotin was added to serial dilutions of the unlabeled 1E2. The signals are represented by the optical density at 405 nm (OD405), as shown on the y axis for the concentrations of the indicated MAb on the x axis. (B) Changes in MAb fluorescence (excitation wavelength, 284 nm; emission wavelength, 341 nm) upon addition of increasing amounts of capsular polysaccharide. (C) Capsule reactions produced by binding of the MAbs to S. pneumoniae (WU2). The capsule reaction was assessed by DIC microscopy. (Left and right) 1E2 and 7A9 produce an intense puffy-type capsule reaction with whole capsule. (Middle) 5F6 produces a much weaker capsule reaction of the puffy type.

A fluorescence perturbation assay was used to test the binding of 1E2, 5F6, and 7A9 to soluble PPS3 (Fig. 1B). In this assay, a change in the MAb intrinsic fluorescence produced by ligand binding was used as a reporter for antigen-antibody interaction. 5F6 showed a hyperbolic increase in fluorescence upon addition of increasing amounts of PPS3. 7A9 showed a hyperbolic decrease in fluorescence on addition of increasing amounts of PPS3. These hyperbolic relationships between the ligand concentration and fluorescence, whether in the form of an increase or a decrease in intrinsic fluorescence, suggest simple two-state binding to independent, noninteracting binding sites. In contrast, MAb 1E2 produced a biphasic curve in which there was an initial increase in fluorescence upon the addition of small amounts of polysaccharide; however, with large amounts of PPS3, the fluorescence decreased from maximal levels. A fit of the data to a hyperbolic curve allowed an estimation of the relative affinity of each antibody, where the apparent Kd was calculated as the molar concentration of the polysaccharide that produced a half-maximal change in fluorescence. The relative Kd values of 1E2, 5F6, and 7A9 were 0.18 μM, 9.5 μM, and 0.44 μM, respectively. Each of the MAbs produced a capsular reaction pattern when observed by DIC microscopy. 1E2 and 7A9 produced a prominent puffy-type reaction. 5F6 produced a similar type of reaction, albeit less intense (Fig. 1C). The “puffy” pattern is characterized by an initial increase in the refractive index at the capsular edge, followed by a gradient of change throughout the capsule. These results indicate that the MAbs have different interactions with the capsular polysaccharide on pneumococcal cells.

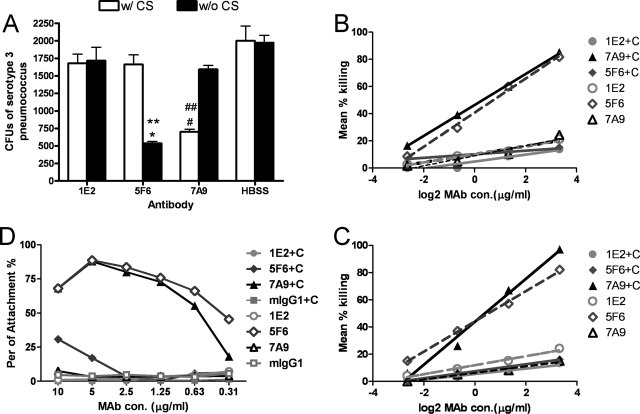

In vitro opsonophagocytic-killing assay.

The abilities of 1E2, 5F6, and 7A9 to promote killing of serotype 3 pneumococcus, WU2, was evaluated with mouse neutrophils and J774 cells using two killing assays and one phagocytosis assay. The results obtained with all three assays were the same. Assay 1 is a killing assay that has been used to establish the abilities of other MAbs to PPS to enhance effector cell killing of pneumococcus (14). Neither 1E2 nor 5F6 led to an increase in killing in the presence of complement, but 7A9 did (Fig. 2A). In contrast, 5F6 increased killing only when a complement source was omitted from the reaction mixture (Fig. 2A). 1E2 did not promote killing at other E:T ratios (data not shown). To determine whether 1E2 could promote killing with another type of effector cell, J774 cells were used. The J774.16 macrophage-like cell line has been used extensively to study the opsonic efficacies of anti-capsular MAbs (4, 12, 41, 44, 52). 1E2 did not promote killing with J774 cells (data not shown), nor did it do so with another serotype 3 strain, A66 (data not shown). Assay 2 yielded results similar to those of assay 1. For this assay, dilutions of the MAbs were used with J774 cells (Fig. 2B) or neutrophils (Fig. 2C), and the MAb concentration that led to 50% killing compared to growth in the opsonophagocytic buffer was taken as the opsonophagocytic concentration. As for assay 1, only 7A9 promoted killing. The opsonophagocytic concentration of 7A9 was 0.31 μg/ml (with J774 cells) or 0.39 μg/ml (with neutrophils). The other MAbs did not result in 50% killing at any concentration with complement; however, <1 μg/ml 5F6 did promote killing with both J774 cells (Fig. 2B) and neutrophils (Fig. 2C) when the assay was performed without a complement source. The data shown are from a representative experiment that was repeated three separate times with similar results. To make sure that the decrease in CFU that we observed was due to killing rather than clumping of the MAbs, bacteria were incubated with serial dilutions of the MAbs and cultured on the plates. The concentrations that produced clumping were as follows: 250 μg/ml for 1E2 and 5F6 and 50 μg/ml for 7A9. The highest concentration of MAb used in these experiments was 10 μg/ml. The use of serial dilutions of 1E2 with an initial concentration of 200 μg/ml did not promote 50% killing (not shown).

FIG. 2.

Opsonic activities of the PPS3-binding MAbs. (A) Results of assay 1 showing MAb-mediated killing of WU2 by mouse neutrophils at an E:T ratio of 500:1. The number of CFU after incubation of serotype 3 pneumococci with preopsonized mouse neutrophils and MAbs is plotted on the y axis for the conditions shown on the x axis. Mean values and standard deviations are shown for the indicated three independent assays. *, P < 0.005, comparing 5F6 without complement serum (w/o CS) to with CS; #, P < 0.02, comparing 7A9 with CS to without CS; **, P < 0.005, comparing 5F6 to HBSS without CS; ##, P < 0.005, comparing 7A9 to HBSS with CS (unpaired t test). (B and C) Results of assay 2 showing MAb-mediated killing of WU2 with J774 cells (B) and mouse neutrophils (C) at an E:T ratio of 400:1. The MAbs were diluted 1:4 from a beginning concentration (con.) of 10 μg/ml. +C, 10% mouse complement serum was added as a complement resource. (D) Results of assay 3 showing MAb-mediated phagocytosis of WU2 with J774 cells at an E:T ratio of 1:10. The MAbs were diluted 1:2 from a beginning concentration of 10 μg/ml. +C, 10% mouse complement serum was added as complement resource. mIgG1, mouse IgG1.

To confirm our results using another type of assay, a method that determines pneumococcal phagocytosis by effector cells using fluorescence-activated cell sorting was also used (5). The results were similar to those obtained with assays 1 and 2: 7A9 promoted phagocytosis with complement, yielding 55.4% phagocytosis at a concentration of 0.63 μg/ml, whereas 1E2 and 5F6 did not (Fig. 2D). 5F6 promoted phagocytosis without complement, yielding 66.1% phagocytosis at a concentration of 0.63 μg/ml. Interestingly, though in general the percent of attachment increased with a higher concentration of MAb (7A9 with complement and 5F6 without complement), there was less attachment at 10 μg/ml than at 5 μg/ml for 7A9 (with complement) and 5F6 (without complement) (Fig. 2D). This result is consistent with the prozone-like phenomenon, which has been described for the activity of pneumococcal antibodies (17, 26, 29).

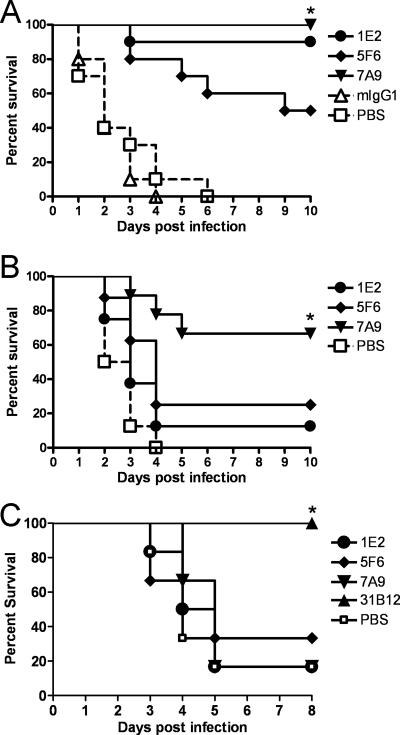

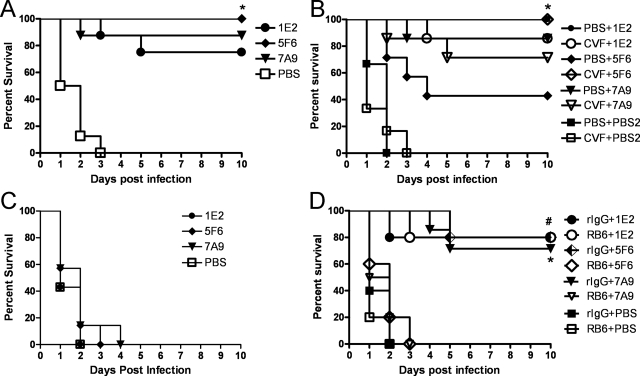

Survival studies with WT C57BL/6 mice.

I.n. challenge with 108 CFU WU2 in naïve mice resulted in 100% lethality within 6 days in all strains of mice except FcγRIIB KO mice (Fig. 3 to 5). Ten micrograms of 1E2, 5F6, or 7A9 significantly prolonged survival compared to isotype control mouse IgG1-treated (P values, <0.0001, <0.0001, and <0.0001, for 1E2, 5F6, and 7A9, respectively) and PBS-treated (P values, <0.0001, <0.001, and <0.0001, respectively) WT mice (Kaplan-Meier log rank survival test) (Fig. 3A). All three MAbs were also protective against i.n. challenge with a different serotype 3 strain, ATCC 6303 (data not shown), and in an i.p. model of infection (data not shown). The efficacies of 1E2 and 7A9 were significantly greater than that of 5F6 (P < 0.03 for 1E2 and P < 0.02 for 7A9). 7A9 (0.1 μg) significantly prolonged survival compared to PBS-treated WT mice (P < 0.001), but 0.1 μg 1E2 or 5F6 did not (Fig. 3B). None of the MAbs prolonged the survival of WT mice after lethal i.n. challenge with serotype 8 (ATCC 6308), but a PPS8-specific mouse MAb did (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

Survival of WT C57BL/6 mice challenged i.n. after i.p. administration of PPS3-binding MAbs. (A) Survival of WT mice challenged i.n. with WU2 after passive immunization with 10 μg 1E2, 5F6, or 7A9 i.p. There was a significant prolongation of survival for each MAb compared to the isotype control mouse IgG1 (mIgG1)-treated mice (*, P < 0.0001, P < 0.0001, and P < 0.0001 for 1E2, 5F6, and 7A9, respectively) or PBS-treated mice (*, P < 0.0001, P < 0.001, and P < 0.0001, respectively) (Kaplan-Meier log rank test; n = 10 mice per group). (B) Survival of WT mice challenged i.n. with WU2 after i.p. administration of 0.1 μg 1E2, 5F6, or 7A9. There was a significant prolongation of survival for 7A9- compared to PBS-treated mice (*, P < 0.001) but no difference between 1E2 or 5F6 and the PBS group (Kaplan-Meier log-rank test; n = 8 or 9 mice per group). (C) Survival of WT mice challenged i.n. with 5,000 CFU of serotype 8 pneumococci (ATCC 6308) after i.p. administration of 10 μg 1E2, 5F6, or 7A9 and a PPS8-specific mouse IgG1 MAb, 31B12. There was a significant prolongation of survival for 31B12- compared to PBS-treated mice (*, P < 0.001) but no difference between the PPS3-specific MAb 1E2, 5F6, or 7A9 and the PBS group (Kaplan-Meier log rank test; n = 6 to 8 mice per group).

FIG. 5.

Survival of FcγR-deficient mice challenged i.n. with WU2 after i.p. administration of PPS3-binding MAbs. (A) FcγR KO mice. Survival of FcγR KO mice that received 5F6 and 7A9 was significantly longer than that of PBS-treated animals (*, P < 0.001 and P < 0.001 for 5F6 and 7A9, respectively; n = 14 or 15 mice per group). There was no significant difference between 1E2-treated mice and PBS-treated mice. (B) FcγRIIB KO mice. Survival of 1E2-treated FcγRIIB KO mice was significantly longer than that of PBS -treated mice (*, P < 0.003; n = 8 mice per group). There was no significant difference between 1E2- or 7A9-treated mice and PBS-treated mice.

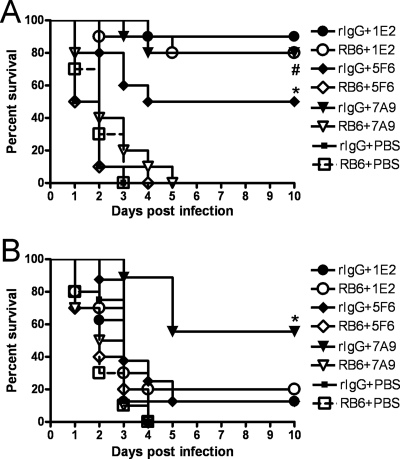

Survival studies with neutrophil-depleted mice.

Since 5F6 (without complement) and 7A9 (with complement) promoted pneumococcal killing in vitro but 1E2 did not, we investigated the effects of neutrophil depletion on the efficacies of the MAbs in mice depleted of peripheral neutrophils with the MAb RB6 (Fig. 4). The percentage of circulating neutrophils in RB6-treated mice was significantly lower (undetectable) than that in rIgG-treated (22%) mice at the time of infection (18 h after RB6 administration) and 42 h after infection (12% versus 32%, respectively). The survival of mice treated with 10 μg 1E2 that received RB6 was significantly longer than that of PBS-treated mice (P < 0.0001), but there was no difference between RB6- and control rIgG-treated mice (Fig. 4A). For mice treated with 10 μg 5F6 or 7A9, the survival of the control rIgG-treated group was significantly longer than that of the RB6-treated group (P < 0.001 and P < 0.0001 for 5F6 and 7A9, respectively). In addition, mice treated with 0.1 μg 7A9 and given RB6 were not protected (Fig. 4B). Hence, PMNs were essential for 5F6- and 7A9-mediated protection but dispensable for the efficacy of 1E2.

FIG. 4.

Survival of neutrophil-depleted WT mice challenged i.n. with WU2 after i.p. administration of PPS3-binding MAbs. (A) Survival of neutrophil-depleted WT mice challenged i.n. with WU2 after neutrophil depletion with RB6 or control treatment and i.p. administration of 10 μg of the indicated MAbs. Neutrophil depletion had no significant effect on protection by 1E2, but it completely abrogated protection by 5F6 (*, P < 0.001) and 7A9 (#, P < 0.0001) (Kaplan-Meier log rank test; n = 10 mice per group). (B) Survival of neutrophil-depleted WT mice challenged i.n. with WU2 after neutrophil depletion with RB6 or control treatment and i.p. administration of 0.1 μg of the indicated MAbs. Neutrophil depletion completely abrogated protection by 7A9 (*, P < 0.001) (Kaplan-Meier log rank test; n = 8 to 10 mice per group).

Survival studies with Fc receptor-deficient mice.

To investigate the dependence of MAb efficacy on Fc receptors, FcγR KO mice, which lack activating FcγRs (FcγRI, FcγRIII, and FcγRIV), and FcγRIIB KO mice, which lack only the inhibitory receptor, were used. 5F6 or 7A9 (10 μg) prolonged the survival of FcγR KO mice (P = 0.0002 and P < 0.0001, respectively) but not FcγRIIB KO mice (Fig. 5A and B). In contrast, 10 μg 1E2 did not prolong the survival of FcγR KO (Fig. 5A) but did prolong the survival of FcγRIIB KO mice (P < 0.003) (Fig. 5B).

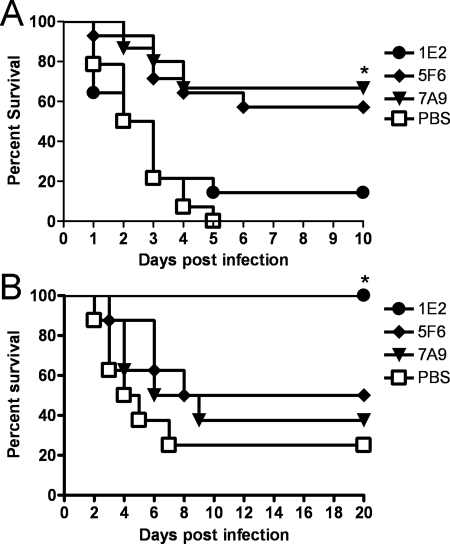

Survival studies with complement-deficient mice.

The administration of 10 μg 1E2, 5F6, or 7A9 significantly prolonged the survival of C3 KO mice compared to that of PBS-treated mice (P values, <0.001, <0.0001, and <0.001, respectively) (Fig. 6A). However, compared with WT mice (Fig. 3A), 50% of which were protected by 5F6 after 10 days, 100% of C3 KO mice were protected by 5F6 administration. For 1E2-, 7A9-, and PBS-treated mice, there was no statistical difference in the survival of C3 KO mice and WT mice. To confirm these findings, C3 was depleted from WT mice with CVF prior to MAb administration and infection. The result was similar to the results with C3 KO mice: 5F6-treated C3-depleted WT mice survived significantly longer than PBS-treated mice (P < 0.02) (Fig. 6B). Protection experiments were performed with C4 KO (88) and factor B (FB) KO mice (61) using the same protocol as for C3 KO mice. The results of these experiments showed that the survival of C4 and FB KO mice that received 5F6 was significantly longer than that of PBS-treated control mice, and there was no significant difference between 5F6-treated C4 KO or FB KO mice and WT mice. This revealed that C3, rather than another complement component, was required to diminish the efficacy of 5F6 (data not shown). For 1E2- and 7A9-treated mice, there was also no difference in survival between C3-depleted mice and PBS-treated mice (Fig. 6B). Since 0.1 μg 7A9 protected WT mice, the efficacy of this dose of MAb in WU2-infected CVF-treated mice was also investigated (Fig. 6C), and 0.1 μg MAb did not prolong the survival of CVF-treated mice. This result indicated that C3 is essential for protection mediated by 0.1 μg 7A9, even though it is not required for protection mediated by 10 μg 7A9.

FIG. 6.

Survival of C3-deficient mice challenged i.n. with WU2 after i.p. administration of PPS3-binding MAbs. (A) C3 KO mice. Survival of C3 KO mice that received 10 μg 1E2, 5F6, or 7A9 was significantly longer than that of PBS-treated animals (*, P < 0.001, P < 0.0001, and P < 0.001 for 1E2, 5F6, and 7A9, respectively; Kaplan-Meier log-rank test; n = 8 mice per group). (B) CVF-treated mice. Survival of mice treated with 10 μg 5F6 plus CVF was significantly longer than that of mice treated with 5F6 plus PBS (*, P < 0.02; n = 7 or 8 mice per group). There was no significant difference between mice treated with 10 μg 1E2 plus CVF and mice treated with 1E2 plus PBS or between mice treated with 10 μg 7A9 plus CVF and mice treated with 7A9 plus PBS. PBS2, PBS control for MAbs. (C) CVF-treated mice. There was no significant difference between mice treated with 0.1 μg MAb, mice treated with PBS, and mice treated with CVF (n = 7 mice per group). (D) RB6-treated C3 KO mice. Survival of mice treated with 10 μg 5F6 (or 7A9) plus rIgG was significantly longer than that of mice treated with 5F6 (or 7A9) plus RB6 (*, P < 0.02 for 5F6; #, P < 0.001 for 7A9; n = 5 to 10 mice per group). There was no significant difference between mice treated with 10 μg 1E2 plus rIgG and mice treated with 1E2 plus RB6.

To investigate the effects of neutrophils on 5F6 and 7A9 in the absence of C3, we depleted neutrophils in C3 KO mice and performed a survival experiment using the protocol described above. C3 KO mice treated with 10 μg 5F6 plus rIgG survived significantly longer than C3 KO mice treated with 5F6 plus RB6 (P = 0.002); however, 5F6 did not protect PMN-depleted C3 KO mice (Fig. 6D). In addition, neutrophil- and C3-depleted mice were not protected by 10 μg 7A9. These results confirmed the essential role of neutrophils in 5F6- and 7A9-mediated protection. For 1E2, there were no significant differences in the survival of RB6-treated and rIgG-treated C3 KO mice. Hence, both neutrophils and complement were dispensable for the efficacy of 1E2.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study show that a nonopsonic PPS3-specific MAb, 1E2, was as protective against a lethal i.n. challenge with serotype 3 pneumococcus in mice as were two opsonic MAbs, 5F6 and 7A9. Surprisingly, our results also show that none of the MAbs under investigation required complement to mediate protection in mice when 10 μg of MAb was used, although 7A9 did when a smaller amount (0.1 μg) was used. Our data also show that the MAbs had different requirements for neutrophils and Fc receptors to mediate protection, so that the inhibitory Fc receptor FcRγIIB was dispensable for the efficacy of the nonopsonic MAb but not the opsonic MAbs. To our knowledge, there is no precedent for the ability of a nonopsonic IgG MAb to mediate protection against an i.n. challenge with pneumococcus in mice. Hence, our findings extend the available knowledge about host requirements for antibody efficacy and pose new questions about antibody immunity to pneumococcal pneumonia.

There is abundant evidence that PPS-specific antibodies are critical mediators of protection against pneumococcal disease (10, 15, 76). However, there is less information about the PPS determinants that elicit protective antibodies. The capsular quellung-type reaction has been used to study the specificities of MAbs to the capsular polysaccharide of C. neoformans and the capsular polypeptide of Bacillus anthracis (24, 40). In our study, use of this technique revealed that there are differences in how 1E2, 5F6, and 7A9 bind to the WU2 capsule. These differences are intriguing, because they provide a link beween MAb binding and function. For example, 1E2 and 7A9, which were highly protective in WT mice, produced a capsule reaction that was very similar to the puffy-type reactions that were observed for MAbs to both C. neoformans and B. anthracis. In contrast, 5F6, which was less protective, also produced a puffy-type reaction, but the intensity of the staining was much less than that with 1E2 and 7A9. This difference paralleled the fluorescence perturbation studies, which revealed that 5F6 had a lower relative affinity than 1E2 and 7A9. The lower affinity of 5F6 might account for the different capsule reaction it produced under DIC microscopy. Alternatively, the density of the epitope it recognizes might be lower than that of the one recognized by 1E2 or 7A9, although the lower affinity of 5F6 could explain its lower degree of efficacy in WT mice. Since competition ELISAs revealed that the MAbs bind at least two distinct determinants and the capsule reaction patterns are each distinct, our findings confirm the results of a previous study which showed that protective PPS3-specific MAbs had different specificities (19). This makes the nature of the PPS determinants that elicit the most protective antibodies paramount, particularly for the PPS of serotype 3, for which a consistently opsonic vaccine-elicited response has not been documented (27, 62, 74). While we do not know the precise determinants to which our MAbs bind, the differences in their functional characteristics in vitro and in vivo provide a roadmap to the identification of antigens that elicit protective antibodies.

The survival of WT mice was prolonged by 10 μg of 1E2, 5F6, and 7A9. At this dose, none of the MAbs required complement to mediate protection. Interestingly, 5F6, which had a distinct capsular reaction pattern and recognized a different PPS3 determinant than 7A9 and 1E2, was more effective in C3 KO (and CVF-treated) mice than in WT mice. Notably, the ability of 5F6 to promote pneumococcal killing in vitro was abrogated in the presence of complement. These findings suggest that C3 had an antagonistic effect on the ability of 5F6 to enhance killing in vitro and to mediate protection in vivo. At present, we do not know why there is an inverse relationship between 5F6 efficacy and the presence of C3. However, since C3 is covalently bound to the PPS3 surface (32), we are investigating the hypothesis that the PPS3 determinant to which 5F6 binds is in or near the C3 binding site so that it competes with C3 for PPS3 binding. In contrast to 5F6, 7A9 required complement to promote killing in vitro and manifested a prozone-like effect. In vivo, 7A9 was the only MAb that was protective when a 0.1-μg dose was used, with the caveat that protection at this dose required complement. These observations suggest that the efficacy of 7A9 depends on the nature of the MAb-pneumococcus (immune) complex, which could in turn determine which host cell receptor induces phagocytosis. For example, the need for complement could be abrogated in the presence of a larger amount of 7A9 if FcγRs can be engaged, but it could be essential when a smaller amount of MAb is present. The dispensability of C3 for antibody-mediated protection in mice was demonstrated previously for protection against i.n. challenge with serotype 1 (70), but the alternative complement pathway was required for the efficacy of human PPS6A-specific IgG1 and IgG2 in mice in an i.p. model with serotype 6A (72). To our knowledge, the dependence of antibody efficacy on complement with respect to the amount of antibody has not been investigated previously. However, as our data show for 7A9, it has been shown that the amount of antibody required to promote pneumococcal phagocytosis in vitro is less in the presence of complement (63). Differences in the requirement for complement in antibody-mediated protection could stem from differences in the infection models, such as the pneumococcal strain or serotype used, the route of infection (systemic or pulmonary), and/or the type or specificity of the antibody. The mouse IgG1 subclass is less effective at activating complement than other IgG subclasses (55). Hence, the requirement for complement of MAbs of other IgG subclasses must be determined to fully understand the significance of complement for antibody protection against pneumococcal pneumonia. These studies were beyond the scope of this report.

Neutrophils are the most important cell type in natural (innate) resistance of naïve mice to pneumococcal pneumonia (37, 79). However, to our knowledge, the importance of neutrophils for antibody-mediated protection against pneumococcal disease has not been explored previously. In this study, neutrophils were essential for the efficacy of 5F6 and 7A9 in WT and C3-deficient mice. This observation parallels our finding that 5F6 and 7A9 promoted neutrophil-mediated pneumococcal killing in vitro, albeit in the absence of complement for 5F6. The requirement for neutrophils, but not complement, when a higher dose of 7A9 was used and the requirement for complement when a lower dose was used suggest there could be a dichotomy between Fc and complement receptors in 7A9-mediated antipneumococcal activity, depending on the amount of antibody. More work is needed to determine whether 7A9- and/or 5F6-like antibodies are produced in response to PPS3 vaccination in humans, but it is worth noting that 5F6-like antibodies would not be identified by the standard opsonophagocytosis assay, because it includes a complement source (5, 68). Nonetheless, 5F6-like antibodies might be useful when complement is scarce, as it can be in the setting of pneumococcal infection and sepsis (73).

In contrast to 5F6 and 7A9, the efficacy of 1E2 did not require neutrophils or complement. Our data demonstrate that although 1E2 is protective in vivo, it does not promote pneumococcal killing by either neutrophils or macrophage-like cells (J774) in vitro. This finding is not without precedent. MAbs to a non-PPS determinant, phosphorylcholine, were protective against systemic challenge with WU2 but did not promote pneumococcal killing in vitro (8). Interestingly, the same MAbs were not protective against serotype 27 (Pn27) infection, even though they were able to promote Pn27 killing in vitro. Hence, antibody-mediated in vitro killing is an insufficient surrogate for predicting antibody efficacy in vivo. At present, the cells and/or factors that are required for 1E2-mediated protection against pneumococcal disease in mice are unknown. It is possible that this MAb could promote killing in vivo or enhance other host effector mechanisms. Along these lines, peripheral macrophages enhanced killing of serotype 1 pneumococcus (2, 23), and a mouse anti-capsular MAb to PPS3 mediated the transfer of MAb-bacterial (WU2) complexes from erythrocytes to macrophages (44). Studies to examine the dependence of MAb activity on macrophages in vitro and in vivo were beyond the scope of this study but are currently under way in our laboratory.

FcγRs were required for each MAb that was used in this study to mediate protection in mice. These experiments were performed to delve deeper into the host cell requirements for MAb-mediated protection in vivo. Mouse cells express three activating receptors, I, III, and IV, and one inhibitory receptor, IIB (57). Our finding that FcγR, but not FcγRIIB, was required for 1E2-mediated protection suggests that 1E2 mediates protection by interacting with FcγRI, FcγRIII, or FcγRIV. Since neither FcγRI nor FcγRIV binds to the IgG1 subclass (56), FcγRIII is most likely the Fc receptor to which 1E2 binds. Notably, a mouse MAb to PPS3 mediated immune adherence to macrophages in part through FcγRIII (44), and the protective effect of alveolar macrophages was a function of their ability to dampen the inflammatory response in a model of pneumococcal pneumonia (38). This is interesting in light of recent evidence that FcγRIII, which is expressed on alveolar macrophages, has inhibitory activity (60). Hence, given that we have already demonstrated that 1E2 does not promote pneumococcal killing or phagocytosis in vitro, we hypothesize that it might bind to FcγRIII, but instead of promoting opsonic killing, this interaction might modulate the host inflammatory response in the lung. More work is needed to validate the hypothesis that 1E2 could enhance macrophage function and/or macrophage-mediated immunomodulation, but this concept is supported by our data showing that 1E2 was unique among the MAbs used in this study in that it did not promote opsonophagocytosis in vitro or require neutrophils, complement, or FcγRIIB to mediate protection. The efficacy of an IgM MAb to PPS8 that did not promote opsonic killing in vitro against pneumonia was associated with immunomodulation (13).

Unlike the activating FcγRI, -III, and -IV receptors, the function of inhibitory FcγRIIB is to modulate immune responses, including FcγR-mediated phagocytosis, proinflammatory cytokine production, antigen presentation, and antibody responses (57). FcγRIIB KO mice are more resistant to Mycobacterium tuberculosis (46), Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi (21), and i.p. challenge with serotype 2 S. pneumoniae (20). In our infection model, FcγRIIB KO mice were more resistant to a lethal i.n. challenge with WU2 than WT mice. This finding confirms and extends to a pulmonary-infection model the aforementioned observation that FcγRIIB KO mice are more resistant to i.p. infection with serotype 2 (20). We also found that FcγRIIB, but not the activating FcγR, was required for 5F6 and 7A9 to mediate protection. This finding is reinforced by our data showing that these MAbs were protective in FcγR KO mice, which express FcγRIIB (81). Since both 5F6 and 7A9 promoted pneumococcal killing in vitro, their dependence on FcγRIIB to mediate protection in vivo suggests that their mechanism of efficacy could involve modulation of the inflammatory response. This concept is consistent with the finding of another group that PPS-immunized mice were more susceptible than WT mice to a lethal challenge with serotype 2 pneumococcus, dying with higher levels of proinflammatory cytokines (20). Immune complexes containing IgG1 are more likely to bind FcγRIIB (9), which could enhance its inhibitory effects. Although inflammatory responses in the lungs are crucial for host defense against pneumococcal pneumonia, unregulated inflammation can enhance host damage (39). Hence, if an opsonic antibody, such as 5F6 or 7A9, binds to an activating FcγR, a cytokine storm could ensue without the immunomodulatory effect of FcγIIB. Studies to test this hypothesis were beyond the scope of this study but are now under way in our laboratory. However, our findings suggest the intriguing possibility that pneumococcal disease/sepsis could be more severe in immunized individuals who lack the ability to induce immunomodulation.

The data presented here demonstrate that a nonopsonic mouse IgG1, 1E2, can mediate protection against i.n. challenge with serotype 3 pneumococcus. We recognize that the concept that nonopsonic antibodies can mediate protection against an encapsulated bacterium is unconventional. While it is possible that 1E2 could promote phagocytosis and/or killing in vivo, our data suggest that such activity would not depend on host factors that are classically implicated in antibody immunity to pneumococcus and other encapsulated microbes, namely, complement and neutrophils. Since each of the MAbs we studied was protective, and PPS-specific MAb-mediated protection is associated with bacterial clearance (11, 13, 25, 28), our findings suggest that each MAb has the capacity to induce bacterial clearance. How a nonopsonic MAb could mediate bacterial clearance is uncertain and is a focus of our current studies. Finally, there are a few caveats to our study. Our data were obtained from experiments performed with the WU2 strain. Although we also demonstrated that each of the MAbs we used is also protective against i.n. challenge with a different serotype 3 strain (ATCC 6363) in WT mice, pneumococcal strain differences could contribute to differences in MAb opsonic efficacy and capsular binding patterns/interactions in vitro. Hence, more studies are needed to reveal the precise determinants recognized by antibodies that mediate protection. Nonetheless, our findings reveal new information and have raised new questions that underscore the importance of host factors in antibody-mediated immunity against pneumococcal pneumonia.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01AI045459 and R01AI044374 to L.P. and AI 014209 and AI059348 to T.R.K.

Editor: A. Camilli

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 January 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albrich, W. C., W. Baughman, B. Schmotzer, and M. M. Farley. 2007. Changing characteristics of invasive pneumococcal disease in Metropolitan Atlanta, Georgia, after introduction of a 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Clin. Infect. Dis. 441569-1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ali, F., M. E. Lee, F. Iannelli, G. Pozzi, T. J. Mitchell, R. C. Read, and D. H. Dockrell. 2003. Streptococcus pneumoniae-associated human macrophage apoptosis after bacterial internalization via complement and Fcγ receptors correlates with intracellular bacterial load. J. Infect. Dis. 1881119-1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anttila, M., M. Voutilainen, V. Jantti, J. Eskola, and H. Kayhty. 1999. Contribution of serotype-specific IgG concentration, IgG subclasses and relative antibody avidity to opsonophagocytic activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 118402-407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arulanandam, B. P., J. M. Lynch, D. E. Briles, S. Hollingshead, and D. W. Metzger. 2001. Intranasal vaccination with pneumococcal surface protein A and interleukin-12 augments antibody-mediated opsonization and protective immunity against Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. Infect. Immun. 696718-6724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baxendale, H. E., and D. Goldblatt. 2006. Correlation of molecular characteristics, isotype, and in vitro functional activity of human antipneumococcal monoclonal antibodies. Infect. Immun. 741025-1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bender, J. M., K. Ampofo, K. Korgenski, J. Daly, A. T. Pavia, E. O. Mason, and C. L. Byington. 2008. Pneumococcal necrotizing pneumonia in Utah: does serotype matter? Clin. Infect. Dis. 461346-1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bogaert, D., M. Sluijter, R. de Groot, and P. W. Hermans. 2004. Multiplex opsonophagocytosis assay (MOPA): a useful tool for the monitoring of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Vaccine 224014-4020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briles, D. E., C. Forman, J. C. Horowitz, J. E. Volanakis, W. H. Benjamin, Jr., L. S. McDaniel, J. Eldridge, and J. Brooks. 1989. Antipneumococcal effects of C-reactive protein and monoclonal antibodies to pneumococcal cell wall and capsular antigens. Infect. Immun. 571457-1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brownlie, R. J., K. E. Lawlor, H. A. Niederer, A. J. Cutler, Z. Xiang, M. R. Clatworthy, R. A. Floto, D. R. Greaves, P. A. Lyons, and K. G. Smith. 2008. Distinct cell-specific control of autoimmunity and infection by FcγRIIb. J. Exp. Med. 205883-895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruyn, G. A., B. J. Zegers, and R. van Furth. 1992. Mechanisms of host defense against infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin. Infect. Dis. 14251-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buchwald, U. K., A. Lees, M. Steinitz, and L. Pirofski. 2005. A peptide mimotope of type 8 pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide induces a protective immune response in mice. Infect. Immun. 73333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buissa-Filho, R., R. Puccia, A. F. Marques, F. A. Pinto, J. E. Munoz, J. D. Nosanchuk, L. R. Travassos, and C. P. Taborda. 2008. The monoclonal antibody against the major diagnostic antigen of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis mediates immune protection in infected BALB/c mice challenged intratracheally with the fungus. Infect. Immun. 763321-3328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burns, T., M. Abadi, and L. Pirofski. 2005. Modulation of the lung inflammatory response to serotype 8 pneumococcus infection by a human monoclonal immunoglobulin M to serotype 8 capsular polysaccharide. Infect. Immun. 734530-4538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burns, T., Z. Zhong, M. Steinitz, and L. A. Pirofski. 2003. Modulation of polymorphonuclear cell interleukin-8 secretion by human monoclonal antibodies to type 8 pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide. Infect. Immun. 716775-6783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Butler, J. C., R. F. Breiman, J. F. Campbell, H. B. Lipman, C. V. Broome, and R. R. Facklam. 1993. Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine efficacy. An evaluation of current recommendations. JAMA 2701826-1831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Byington, C. L., K. Korgenski, J. Daly, K. Ampofo, A. Pavia, and E. O. Mason. 2006. Impact of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on pneumococcal parapneumonic empyema. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 25250-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casadevall, A., and M. D. Scharff. 1994. Serum therapy revisited: animal models of infection and development of passive antibody therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 381695-1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2005. Direct and indirect effects of routine vaccination of children with 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease—United States, 1998-2003. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 54893-897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang, Q., Z. Zhong, A. Lees, M. Pekna, and L. Pirofski. 2002. Structure-function relationships for human antibodies to pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide from transgenic mice with human immunoglobulin loci. Infect. Immun. 704977-4986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clatworthy, M. R., and K. G. Smith. 2004. FcγRIIb balances efficient pathogen clearance and the cytokine-mediated consequences of sepsis. J. Exp. Med. 199717-723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clatworthy, M. R., L. Willcocks, B. Urban, J. Langhorne, T. N. Williams, N. Peshu, N. A. Watkins, R. A. Floto, and K. G. Smith. 2007. Systemic lupus erythematosus-associated defects in the inhibitory receptor FcγRIIb reduce susceptibility to malaria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1047169-7174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Committee on New Directions in the Study of Antimicrobial Therapeutics: Immunomodulation. 2006. Treating infectious diseases in a microbial world: report of two workshops on novel antimicrobial therapies, p. 13-20. National Academies Press, Washington, DC. [PubMed]

- 23.Dockrell, D. H., M. Lee, D. H. Lynch, and R. C. Read. 2001. Immune-mediated phagocytosis and killing of Streptococcus pneumoniae are associated with direct and bystander macrophage apoptosis. J. Infect. Dis. 184713-722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duro, R. M., D. Netski, P. Thorkildson, and T. R. Kozel. 2003. Contribution of epitope specificity to the binding of monoclonal antibodies to the capsule of Cryptococcus neoformans and the soluble form of its major polysaccharide, glucuronoxylomannan. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 10252-258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fabrizio, K., A. Groner, M. Boes, and L. A. Pirofski. 2007. A human monoclonal immunoglobulin M reduces bacteremia and inflammation in a mouse model of systemic pneumococcal infection. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 14382-390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Felton, L. D. 1928. The units of protective antibody in anti-pneumococcus serum and antibody solution. J. Infect. Dis. 43531. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fine, D. P., J. L. Kirk, G. Schiffman, J. E. Schwinle, and J. C. Guckinan. 1988. Analysis of humoral and phagocytic defenses against Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes 1 and 3. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 112487-497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glover, D. T., S. K. Hollingshead, and D. E. Briles. 2008. Streptococcus pneumoniae surface protein PcpA elicits protection against lung infection and fatal sepsis. Infect. Immun. 762767-2776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goodner, K., and F. L. Horsfall. 1935. The protective action of type I antipneumococcus serum in mice. I. Quantitative aspects of the mouse protection test. J. Exp. Med. 62359-374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grijalva, C. G., J. P. Nuorti, P. G. Arbogast, S. W. Martin, K. M. Edwards, and M. R. Griffin. 2007. Decline in pneumonia admissions after routine childhood immunisation with pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in the USA: a time-series analysis. Lancet 3691179-1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hicks, L. A., L. H. Harrison, B. Flannery, J. L. Hadler, W. Schaffner, A. S. Craig, D. Jackson, A. Thomas, B. Beall, R. Lynfield, A. Reingold, M. M. Farley, and C. G. Whitney. 2007. Incidence of pneumococcal disease due to non-pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) serotypes in the United States during the era of widespread PCV7 vaccination, 1998-2004. J. Infect. Dis. 1961346-1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hostetter, M. K. 1999. Opsonic and nonopsonic interactions of C3 with Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microb. Drug Resist. 585-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu, B. T., X. Yu, T. R. Jones, C. Kirch, S. Harris, S. W. Hildreth, D. V. Madore, and S. A. Quataert. 2005. Approach to validating an opsonophagocytic assay for Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 12287-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jackson, L. A., K. M. Neuzil, O. Yu, P. Benson, W. E. Barlow, A. L. Adams, C. A. Hanson, L. D. Mahoney, D. K. Shay, W. W. Thompson, and the Vaccine Study Datalink. 2003. Effectiveness of pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in older adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 3481755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jansen, W. T. M., J. Gootjes, M. Zelle, D. Madore, J. Verhoef, H. Snippe, and F. M. Verheul. 1998. Use of highly encapsulated Streptococcus pneumoniae strains in a flow-cytometric assay for assessment of the phagocytic capacity of serotype-specific antibodies. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 5703-710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson, S. E., L. Rubin, S. Romero-Steiner, J. K. Dykes, L. B. Pais, A. Rizvi, E. Ades, and G. M. Carlone. 1999. Correlation of opsonophagocytosis and passive protection assays using human anticapsular antibodies in an infant mouse model of bacteremia for Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Infect. Dis. 180133-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kadioglu, A., and P. W. Andrew. 2004. The innate immune response to pneumococcal lung infection: the untold story. Trends Immunol. 25143-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knapp, S., J. C. Leemans, S. Florquin, J. Branger, N. A. Maris, J. Pater, N. van Rooijen, and P. T. van der Poll. 2003. Alveolar macrophages have a protective antiinflammatory role during murine pneumococcal pneumonia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 167171-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knapp, S., C. W. Wieland, C. van 't Veer, O. Takeuchi, S. Akira, S. Florquin, and P. T. van der Poll. 2004. Toll-like receptor 2 plays a role in the early inflammatory response to murine pneumococcal pneumonia but does not contribute to antibacterial defense. J. Immunol. 1723132-3138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kozel, T. R., P. Thorkildson, S. Brandt, W. H. Welch, J. A. Lovchik, D. P. AuCoin, J. Vilai, and C. R. Lyons. 2007. Protective and immunochemical activities of monoclonal antibodies reactive with the Bacillus anthracis polypeptide capsule. Infect. Immun. 75152-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krishnamurthy, V. M., L. J. Quinton, L. A. Estroff, S. J. Metallo, J. M. Isaacs, J. P. Mizgerd, and G. M. Whitesides. 2006. Promotion of opsonization by antibodies and phagocytosis of Gram-positive bacteria by a bifunctional polyacrylamide. Biomaterials 273663-3674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kumar, D., A. Humar, A. Plevneshi, K. Green, G. V. Prasad, D. Siegal, and A. McGeer. 2007. Invasive pneumococcal disease in solid organ transplant recipients—10-year prospective population surveillance. Am. J. Transplant. 71209-1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lexau, C. A., R. Lynfield, R. Danila, T. Pilishvili, R. Facklam, M. M. Farley, L. H. Harrison, W. Schaffner, A. Reingold, N. M. Bennett, J. Hadler, P. R. Cieslak, and C. G. Whitney. 2005. Changing epidemiology of invasive pneumococcal disease among older adults in the era of pediatric pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. JAMA 2942043-2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li, J., A. J. Szalai, S. K. Hollingshead, M. H. Nahm, and D. E. Briles. 2009. Antibody to the type 3 capsule facilitates immune adherence of pneumococci to erythrocytes and augments their transfer to macrophages. Infect. Immun. 77:464-471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Madhi, S. A., P. Adrian, L. Kuwanda, C. Cutland, W. C. Albrich, and K. P. Klugman. 2007. Long-term effect of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on nasopharyngeal colonization by Streptococcus pneumoniae—and associated interactions with Staphylococcus aureus and Haemophilus influenzae colonization—in HIV-Infected and HIV-uninfected children. J. Infect. Dis. 1961662-1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maglione, P. J., J. Xu, A. Casadevall, and J. Chan. 2008. Fcγ receptors regulate immune activation and susceptibility during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Immunol. 1803329-3338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marks, M., T. Burns, M. Abadi, B. Seyoum, J. Thornton, E. Tuomanen, and L. A. Pirofski. 2007. Influence of neutropenia on the course of serotype 8 pneumococcal pneumonia in mice. Infect. Immun. 751586-1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martens, P., S. W. Worm, B. Lundgren, H. B. Konradsen, and T. Benfield. 2004. Serotype-specific mortality from invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae disease revisited. BMC Infect. Dis. 421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McNeely, T., S. Luo, W. Manger, W. Herber, T. Schofield, C. Tan, K. Newman, J. Sadoff, J. Donnelly, and A. Cross. 2006. Development of an opsonin inhibition assay for evaluation of complex polysaccharide protective epitopes. Vaccine 241941-1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mednick, A. J., M. Feldmesser, J. Rivera, and A. Casadevall. 2003. Neutropenia alters lung cytokine production in mice and reduces their susceptibility to pulmonary cryptococcosis. Eur. J. Immunol. 331744-1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Melegaro, A., and W. J. Edmunds. 2004. The 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. Part I. Efficacy of PPV in the elderly: a comparison of meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 19353-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mukherjee, J., T. R. Kozel, and A. Casadevall. 1998. Monoclonal antibodies reveal additional epitopes of serotype D Cryptococcus neoformans capsular glucuronoxylomannan that elicit protective antibodies. J. Immunol. 1613557-3567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mykietiuk, A., J. Carratala, A. Dominguez, A. Manzur, N. Fernandez-Sabe, J. Dorca, F. Tubau, F. Manresa, and F. Gudiol. 2006. Effect of prior pneumococcal vaccination on clinical outcome of hospitalized adults with community-acquired pneumococcal pneumonia. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 25457-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nahm, M. H., J. V. Olander, and M. Magyarlaki. 1997. Identification of cross-reactive antibodies with low opsonophagocytic activity for Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Infect. Dis. 176698-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Neuberger, M. S., and K. Rajewsky. 1981. Activation of mouse complement by monoclonal mouse antibodies. Eur. J. Immunol. 111012-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nimmerjahn, F., and J. V. Ravetch. 2006. Fcγ receptors: old friends and new family members. Immunity 2419-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nimmerjahn, F., and J. V. Ravetch. 2008. Fcγ receptors as regulators of immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 834-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oosterhuis-Kafeja, F., P. Beutels, and P. Van Damme. 2007. Immunogenicity, efficacy, safety and effectiveness of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (1998-2006). Vaccine 252194-2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ortqvist, A., J. Hedlund, and M. Kalin. 2005. Streptococcus pneumoniae: epidemiology, risk factors, and clinical features. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 26563-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Park-Min, K. H., N. V. Serbina, W. Yang, X. Ma, G. Krystal, B. G. Neel, S. L. Nutt, X. Hu, and L. B. Ivashkiv. 2007. FcγRIII-dependent inhibition of interferon-gamma responses mediates suppressive effects of intravenous immune globulin. Immunity 2667-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pekna, M., M. A. Hietala, A. Landin, A. K. Nilsson, C. Lagerberg, C. Betsholtz, and M. Pekny. 1998. Mice deficient for the complement factor B develop and reproduce normally. Scand. J. Immunol. 47375-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Prymula, R., P. Peeters, V. Chrobok, P. Kriz, E. Novakova, E. Kaliskova, I. Kohl, P. Lommel, J. Poolman, J. P. Prieels, and L. Schuerman. 2006. Pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides conjugated to protein D for prevention of acute otitis media caused by both Streptococcus pneumoniae and non-typable Haemophilus influenzae: a randomised double-blind efficacy study. Lancet 367740-748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reed, W. P., D. L. Stromquist, and R. C. Williams, Jr. 1983. Agglutination and phagocytosis of pneumococci by immunoglobulin G antibodies of restricted heterogeneity. J. Lab Clin. Med. 101847-856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ren, B., A. J. Szalai, S. K. Hollingshead, and D. E. Briles. 2004. Effects of PspA and antibodies to PspA on activation and deposition of complement on the pneumococcal surface. Infect. Immun. 72114-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Retter, I., H. H. Althaus, R. Munch, and W. Muller. 2005. VBASE2, an integrative V gene database. Nucleic Acids Res. 33D671-D674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Robbins, J. B., R. Schneerson, and S. C. Szu. 1995. Perspective: hypothesis: serum IgG antibody is sufficient to confer protection against infectious diseases by inactivating the inoculum. J. Infect. Dis. 1711387-1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Romero-Steiner, S., C. E. Frasch, G. Carlone, R. A. Fleck, D. Goldblatt, and M. H. Nahm. 2006. Use of opsonophagocytosis for serological evaluation of pneumococcal vaccines. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 13165-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Romero-Steiner, S., D. Libutti, L. B. Pais, et al. 1997. Standardization of an opsonophagocytic assay for the measurement of functional antibody activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae using differentiated HL-60 cells. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 4415-422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Russell, N., J. R. Corvalan, M. L. Gallo, C. G. Davis, and L. Pirofski. 2000. Production of protective human anti-pneumococcal antibodies by transgenic mice with human immunoglobulin loci. Infect. Immun. 681820-1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Saeland, E., J. H. Leusen, G. Vidarsson, W. Kuis, E. A. Sanders, I. Jonsdottir, and J. G. Van de Winkel. 2003. Role of leukocyte immunoglobuin G receptors in vaccine-induced immunity to Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Infect. Dis. 1871686-1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Saeland, E., G. Vidarsson, and I. Jonsdottir. 2000. Pneumococcal pneumonia and bacteremia model in mice for the analysis of protective antibodies. Microb. Pathog. 2981-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Saeland, E., G. Vidarsson, J. H. Leusen, E. Van Garderen, M. H. Nahm, H. Vile-Weekhout, V. Walraven, A. M. Stemerding, J. S. Verbeek, G. T. Rijkers, W. Kuis, E. A. Sanders, and J. G. Van de Winkel. 2003. Central role of complement in passive protection by human IgG1 and IgG2 anti-pneumococcal antibodies in mice. J. Immunol. 1706158-6164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schlesinger, M., U. Mashal, J. Levy, and Z. Fishelson. 1993. Hereditary properdin deficiency in three families of Tunisian Jews. Acta Paediatr. 82744-747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schuerman, L., R. Prymula, V. Chrobok, I. Dieussaert, and J. Poolman. 2007. Kinetics of the immune response following pneumococcal PD conjugate vaccination. Vaccine 251953-1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Scott, D. A., S. F. Komjathy, B. T. Hu, S. Baker, L. A. Supan, C. A. Monahan, W. Gruber, G. R. Siber, and S. P. Lockhart. 2007. Phase 1 trial of a 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in healthy adults. Vaccine 256164-6166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shapiro, E. D., A. T. Berg, R. Austrian, D. Schroeder, V. Parcells, A. Margolis, R. K. Adair, and J. D. Clemens. 1991. The protective efficacy of polyvalent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 3251425-1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Spellberg, B., J. H. Powers, E. P. Brass, L. G. Miller, and J. E. Edwards, Jr. 2004. Trends in antimicrobial drug development: implications for the future. Clin. Infect. Dis. 381279-1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stephens-Romero, S. D., A. J. Mednick, and M. Feldmesser. 2005. The pathogenesis of fatal outcome in murine pulmonary aspergillosis depends on the neutrophil depletion strategy. Infect. Immun. 73114-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sun, K., S. L. Salmon, S. A. Lotz, and D. W. Metzger. 2007. Interleukin-12 promotes gamma interferon-dependent neutrophil recruitment in the lung and improves protection against respiratory Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. Infect. Immun. 751196-1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sylvestre, D., R. Clynes, M. Ma, H. Warren, M. C. Carroll, and J. V. Ravetch. 1996. Immunoglobulin G-mediated inflammatory responses develop normally in complement-deficient mice. J. Exp. Med. 1842385-2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Takai, T., M. Li, D. Sylvestre, R. Clynes, and J. V. Ravetch. 1994. FcR gamma chain deletion results in pleiotrophic effector cell defects. Cell 76519-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Takai, T., M. Ono, M. Hikida, H. Ohmori, and J. V. Ravetch. 1996. Augmented humoral and anaphylactic responses in Fc gamma RII-deficient mice. Nature 379346-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Test, S. T., J. K. Mitsuyoshi, and Y. Hu. 2005. Depletion of complement has distinct effects on the primary and secondary antibody responses to a conjugate of pneumococcal serotype 14 capsular polysaccharide and a T-cell-dependent protein carrier. Infect. Immun. 73277-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Thornton, J., and L. S. McDaniel. 2005. THP-1 monocytes up-regulate intercellular adhesion molecule 1 in response to pneumolysin from Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 736493-6498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tian, H., A. Groner, M. Boes, and L. A. Pirofski. 2007. Pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide vaccine-mediated protection against serotype 3 Streptococcus pneumoniae in immunodeficient mice. Infect. Immun. 751643-1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.UNICEF/WHO. 2006. Pneumonia: the forgotten killer of children, p. 34-37. WHO Press, New York, NY.

- 87.Vila-Corcoles, A., O. Ochoa-Gondar, C. Llor, I. Hospital, T. Rodriguez, and A. Gomez. 2005. Protective effect of pneumococcal vaccine against death by pneumonia in elderly subjects. Eur. Respir. J. 261086-1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wessels, M. R., R. Butko, N. Ma, H. B. Warren, A. L. Lage, and M. C. Carroll. 1995. Studies of group B streptococcal infection in mice deficient in complement component C3 or C4 demonstrate an essential role for complement in both innate and acquired immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9211490-11494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhong, Z., T. Burns, Q. Chang, M. Carroll, and L. Pirofski. 1999. Molecular and functional characteristics of a protective human monoclonal antibody to serotype 8 Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharide. Infect. Immun. 674119-4127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhong, Z., and L. Pirofski. 1996. Opsonization of Cryptococcus neoformans by human anti-glucuronoxylomannan antibodies. Infect. Immun. 643446-3450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]