Abstract

The bICP0 protein encoded by bovine herpesvirus 1 stimulates productive infection and viral gene expression but inhibits interferon (IFN)-dependent transcription. bICP0 inhibits beta IFN (IFN-β) promoter activity and induces degradation of IFN regulatory factor 3 (IRF3). Although bICP0 inhibits the trans-activation activity of IRF7, IRF7 protein levels are not reduced. In this study, we demonstrate that bICP0 is associated with IRF7. Furthermore, bICP0 inhibits the ability of IRF7 to trans-activate the IFN-β promoter in the absence of IRF3 expression. The interaction between bICP0 and IRF7 correlates with reduced trans-activation of the IFN-β promoter by IRF7.

Bovine herpesvirus 1 (BHV-1) is a significant bovine pathogen, as BHV-1 infection leads to conjunctivitis, pneumonia, genital disorders, abortions, and “shipping fever,” an upper respiratory tract infection (32). Infection of bovine cells (7) or calves (34) leads to rapid cell death and an increase in apoptosis. As with other Alphaherpesvirinae subfamily members, viral gene expression is temporally regulated in three distinct phases: immediate early (IE), early (E), or late (L) (19).

BHV-1-encoded bICP0 (18), herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP0 (9-12, 21), and equine herpesvirus 1 ICP0 (5, 6) contain a C3HC4 zinc RING finger near their N termini that is necessary for activating productive infection. A single cysteine-to-glycine mutation in the zinc RING finger of bICP0 reduces the growth potential and virulence of BHV-1 in infected calves (30), suggesting that this domain is crucial for bICP0 functions. The intact zinc RING finger of bICP0 is also necessary for the trans-activation of heterologous promoters (18, 37). ICP0 (13-15, 24, 25) and bICP0 (18, 27) localize to and alter promyelocytic leukemia (PML or ND10 bodies) protein-containing nuclear domains by inducing degradation of specific proteins associated with these structures. The C3HC4 zinc RING fingers of bICP0 (8) and ICP0 (3, 4, 33) possess intrinsic E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. Consequently, bICP0 and ICP0 can induce degradation of certain proteins via the ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis pathway (13, 15, 20, 28).

Interferon (IFN) regulatory factor 7 (IRF7) was originally identified as a protein that binds and represses the Epstein-Barr virus Qp promoter (36). IRF7 stimulates alpha/beta IFN (IFN-α/β) expression (2, 23) and is an important regulator of the innate immune response (17). Like IRF3, IRF7 undergoes virus-induced activation and phosphorylation at its C terminus (2, 22, 31). Phosphorylation of IRF7 promotes retention in the nucleus, binding to sequences in promoters of IFN-responsive genes (IFN-stimulated response elements), and interactions with IRF3.

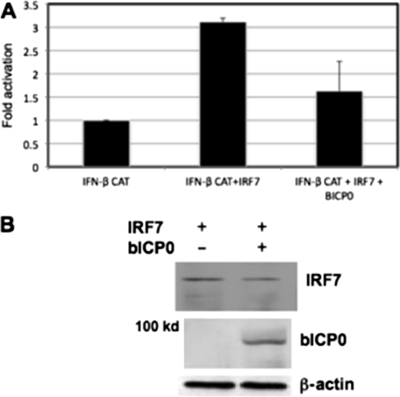

Our previous studies demonstrated that bICP0 inhibited IFN-β promoter activity and that IRF3 levels were reduced in the presence of bICP0 (16, 29). Although bICP0 inhibited the ability of IRF7 to stimulate IFN-β promoter activity (29), it was not clear whether bICP0 had a direct effect on IRF7 or if reduced IRF3 levels inhibited the trans-activation potential of IRF7. To test whether IRF7 could trans-activate the IFN-β promoter and whether bICP0 was able to inhibit IRF7's trans-activation potential in the absence of IRF3, undifferentiated embryonic teratocarcinoma (P19) cells were used. P19 cells do not express a detectable level of IRF3 or IRF7 (data not shown), which is common for many undifferentiated teratocarcinoma cell lines (35). P19 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing IRF7 (pcDNA3.1-IRF7) and bICP0 (pCMV-tag2c-bICP0), and IFN-β promoter activity was measured. Basal IFN-β promoter activity is low in P19 cells unless IRF3 or IRF7 is transfected into these cells (35). Transfection of a plasmid expressing IRF7 with the IFN-β promoter construct stimulated IFN-β chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) promoter activity in P19 cells approximately threefold compared to transfection of an empty vector with the IFN-β promoter (Fig. 1A). Although there was less trans-activation of the IFN-β promoter in P19 cells than in other cell types we examined (29), the results were consistent and may reflect the lack of detectable levels of IRF3 and IRF7 in P19 cells. As observed for other cell types (16, 29), bICP0 inhibited the ability of IRF7 to stimulate IFN-β promoter activity in P19 cells. Furthermore, bICP0 did not reduce IRF7 protein levels in P19 cells (Fig. 1B), which was consistent with results of a previous study (29). As expected, bICP0 was detected only in p19 cells transfected with a wild-type (wt) bICP0 construct (Fig. 1C). The studies in Fig. 1 suggested that IRF7 trans-activated IFN-β promoter activity in the absence of IRF3, and bICP0 inhibited the trans-activation potential of IRF7.

FIG. 1.

Analysis of IRF7 in P19 cells. (A) Inhibition of IRF7-induced IFN-β promoter activity by bICP0 in P19 cells. Mouse embryonic teratocarcinoma cells (P19; ATCC CRL-1825) were cotransfected with the IFN-β CAT reporter plasmid (2.0 μg), the IRF7 expression plasmid (2.0 μg), and the bICP0 expression plasmid (4.0 μg). An empty vector (pcDNA3.1) was used as a negative control and to maintain equivalent amounts of DNA in the each transfection. Cell extract was collected after 40 h of transfection and analyzed for CAT activity as previously described (16, 30), using 0.2 μCi (7.4 kBq) [14C]chloramphenicol (catalog no. CFA754; Amersham Biosciences) and 0.5 mM acetyl coenzyme A (catalog no. A2181; Sigma). Levels of CAT activity were expressed as the change in induction compared to the vector control. Data are the means of results of at least three experiments. Error bars show the standard errors for triplicate transfections. The IFN-β-CAT plasmid contains a minimal human IFN-β promoter (positions −110 to +20) upstream of the bacterial CAT gene and was obtained from Stavros Lomvardas (Columbia University, New York, NY). The IRF7 expression construct was obtained from Luwen Zhang (University of Nebraska). The plasmid pCMV2C-bICP0 expresses Flag-tagged wt bICP0 under the control of the human cytomegalovirus promoter (18). (B) P19 cells were transfected with the designated plasmids, and at 48 h after transfection, Western blot assays were performed as previously described (16, 30). For each lane, 50 μg protein in a whole-cell lysate was loaded. The positions of IRF7 and β-actin are indicated. For panels showing bICP0 protein expression, 100 μg protein was loaded.

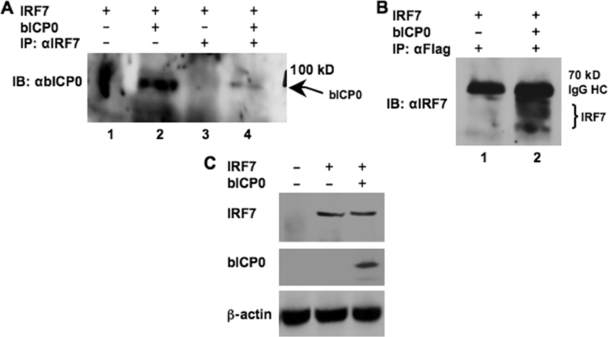

To test whether bICP0 interacted with IRF7, Flag-tagged bICP0 and IRF7 expression vectors (pCMV-tag2c-bICP0 and pcDNA3.1-IRF7, respectively) were cotransfected into P19 cells. Forty-eight hours after transfection, nuclear extracts were prepared and IRF7 immunoprecipitated (IP) using an anti-IRF7 antibody. In the IRF7 immunoprecipitate, Flag-tagged bICP0 was detected by immunoblotting using a polyclonal antibody to bICP0 (Fig. 2A, lane 4) or a mouse monoclonal anti-Flag antibody (data not shown). This band was specific because it was not detected when IRF7, but not bICP0, was expressed in P19 cells (lane 3). When nuclear extracts were IP with the anti-Flag antibody to IP bICP0, several diffuse bands, in addition to the immunoglobulin G heavy chain, were detected when the Western blot was probed with the anti-IRF7 antibody (Fig. 2B, lane 2). These bands migrated at a molecular weight similar to that for IRF7 and were absent in extracts prepared from cells that were not transfected with the IRF7 expression plasmid (Fig. 2B, lane 1). As shown in Fig. 1B, bICP0 expression had little or no effect on IRF7 protein levels in transfected P19 cells (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

bICP0 interacts with IRF7 in transiently transfected cells. P19 cells were cotransfected with pcDNA-IRF7 (5.0 μg) and empty vector pcDNA3.1 (5.0 μg) (lane 1 and 3) or pcDNA-IRF7 (5.0 μg) and Flag-tagged bICP0 (5.0 μg) (lane 2 and 4) expressing vectors by using TransIT (Mirus). Forty-eight hours posttransfection, nuclear extracts were prepared and subjected to IP with rabbit anti-IRF7 (sc-9083x; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or mouse anti-Flag antibodies (catalog no. 200471; Stratagene). For these studies, 500 μg protein was used. Denatured proteins were resolved by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by immunoblotting (IB) using an antiserum that detects bICP0 (A) or IRF7 (B). The position of the molecular weight standard (in kilodaltons) is shown on the right. (C) Total cell lysate was prepared, and Western blots were performed as previously described (16, 30). For each lane, 50 μg protein was loaded. The position of IRF7 and β-actin are denoted. For panels showing bICP0 protein expression, 100 μg protein was loaded. IgG, immunoglobulin G; HC, heavy chain.

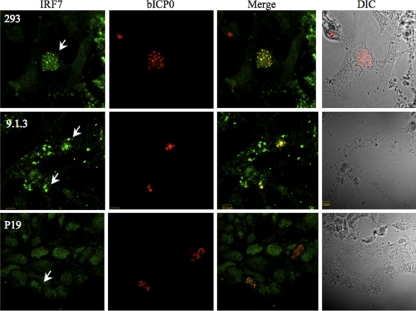

To further explore interactions between bICP0 and IRF7, confocal microscopy was performed. bICP0 localized primarily to punctate structures in the nucleus of human 293, bovine 9.1.3, or P19 cells (Fig. 3). These punctate structures may be ND10 bodies, because bICP0 and ICP0 are known to associate with ND10 bodies (18, 27, 37). Approximately 50% of bICP0-positive P19 cells contained bICP0 that appeared to colocalize with ND10 bodies, which was a lower percentage than that for other cell lines we examined. In many bICP0+ cells (293, 9.1.3, or P19), staining with the IRF7 antibody appeared to colocalize with bICP0 staining. In most cells in which bICP0 was not detected, the subcellular localization of IRF7 was generally more diffuse and was not preferentially localized with punctate nuclear structures.

FIG. 3.

Colocalization of IRF7 and bICP0 in transfected cells. Human 293 (ATCC CRL-1573), mouse P19, or bovine testicular cells (9.1.3) were cotransfected with plasmids expressing Flag-tagged bICP0 (1.0 μg) and IRF7 (1.0 μg) using TransIT (Mirus) or Lipofectamine (Invitrogen). Forty hours after transfection, cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde and stained for confocal microscopy as described previously (29, 37), using the primary antibodies described for Fig. 2. IRF7 was probed with rabbit polyclonal anti-IRF7 and anti-rabbit Cy2 antiserum antibodies (green) (catalog no. 711-225-152; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.), and bICP0 with mouse monoclonal anti-Flag and anti-mouse Cy5 antibodies (red) (catalog no. 715-176-150; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.). Confocal micrographs represent Cy2, Cy5, merged, and phase contrast (DIC) images. Each panel is representative of many cells that were observed in three independent experiments. Arrows, staining with the IRF7 antibody appeared to colocalize with bICP0 staining in most bICP0-positive cells.

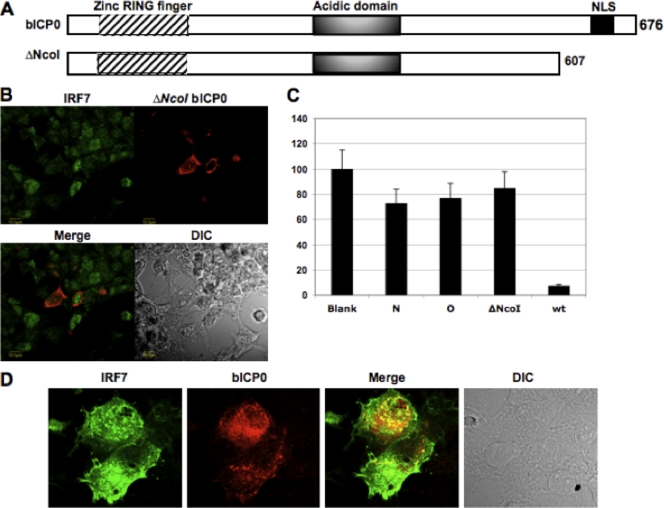

To test whether nuclear localization of bICP0 was necessary for colocalizing with IRF7, a C-terminal deletion mutant of bICP0 (ΔNcoI) (18, 37) that lacks the nuclear localization signal (NLS) (Fig. 4A) was cotransfected with a plasmid expressing IRF7. As expected, the bICP0 protein that lacked a NLS (the ΔNcoI construct) was localized to the cytoplasm in 293 cells (Fig. 4B) and other cell types (37). IRF7 was detected both in the cytoplasm and in the nuclei of cells that expressed the ΔNcoI mutant, suggesting that nuclear localization of bICP0 was important for colocalization with IRF7 (Fig. 4B). Finally, immunoprecipitation studies failed to detect a stable interaction between the ΔNcoI mutant and IRF7 in transiently transfected cells (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

bICP0 deletion mutant does not colocalize with IRF7. (A) Schematic of wt bICP0 and C-terminal deletion mutant. Previously, the ΔNcoI mutant was shown to localize to the cytoplasm because it lacks a NLS (37). (B) 293 cells were cotransfected with 1.0 μg of a plasmid expressing the Flag-ΔNcoI bICP0 mutant and IRF7 using TransIT (Mirus). After 40 h of transfection, confocal microscopy was performed as described previously (29, 37) and in the legend to Fig. 3. IRF7 was probed with rabbit polyclonal anti-IRF7 and donkey anti-rabbit Cy2 antibodies (green), and bICP0 with mouse monoclonal anti-Flag and donkey anti-mouse Cy5 antibodies (red). Confocal micrographs represent Cy2, Cy5, merged, and phase contrast (DIC) images. (C) 293 cells were cotransfected with the IFN-β CAT reporter plasmid (2.0 μg), the IRF7 expression plasmid (2.0 μg), and the designated bICP0 expression plasmid (4.0 μg). An empty vector (pcDNA3.1) was used as a negative control and to maintain equivalent amounts of DNA in the each transfection. Cell extract was collected after 40 h of transfection, and CAT activity was measured as described for Fig. 1. The lanes denoted N and O were transfected with plasmids expressing transposon insertion mutants of bICP0 that do not inhibit IRF7 induction of the human IFN-β promoter (37). The N and O mutants contain a transposon insertion near the C terminus of bICP0 but not within the NLS. (D) The wt Cooper strain of BHV-1 was used to infect MDBK cells at a multiplicity of infection of 1. After 1 h of adsorption at 37°C, cells were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline and then fed with Earle's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum. At 8 h after infection, cells were fixed, and confocal microscopy was performed as described previously (29, 37) and for Fig. 3. NLS, nuclear localization signal.

To test whether the ΔNcoI mutant inhibited IRF7-induced IFN-β promoter activity, transient transfection assays were performed. The ΔNcoI mutant and the empty vector inhibited IRF7-induced IFN-β promoter activity less efficiently than wt bICP0 (Fig. 4C). As another comparison, we tested two bICP0 transposon insertion mutants (N and O) that were unable to impair IRF7 induction of IFN-β promoter activity (29). The transposon insertion mutants, like the ΔNcoI mutant, did not inhibit IRF7 mediated trans-activation of the IFN-β promoter.

Although we observed limited colocalization of bICP0 and IRF7 during productive infection by confocal microscopy (Fig. 4D) and immunoprecipitation experiments (data not shown), interactions between IRF7 and bICP0 were not as clear-cut as those in transfected cells. There appear to be several possible reasons that the association between bICP0 and IRF7 was not obvious during productive infection. First, BHV-1 induces nuclear and cellular damage, which may alter subnuclear structures. Second, bICP0 may interact with additional viral or virus-induced proteins during productive infection, and these interactions may influence IRF7 subcellular localization. Third, it is possible that additional viral proteins interacted with IRF7 during productive infection and that, consequently, the majority of IRF7 does not localize to subnuclear structures. Finally, we have more difficulty extracting bICP0 from the nuclei of infected cells than from transfected cells.

The results of this study suggested that nuclear bICP0 associated with IRF7 in the absence of other viral genes and, consequently, inhibited its activity. Furthermore, it appeared that bICP0 induced IRF7 to associate with nuclear structures that may be ND10 in transfected cells. Interactions between bICP0 and IRF7 may prevent IRF7 from interacting with the IFN-β promoter or with other proteins necessary for trans-activating the IFN-β promoter. Finally, evidence was provided indicating that interactions between bICP0 and IRF7 did not require IRF3 expression, because IRF3 was not detected in P19 cells. At this point, we do not know whether bICP0 interacted directly with IRF7 or with a complex of proteins that contained IRF7. Regardless of whether bICP0 directly interacted with IRF7, bICP0 inactivated IRF7 by a different mechanism than IRF3, because bICP0 induces IRF3 degradation (29) and we were unable to detect an interaction between IRF3 and bICP0 (data not shown).

A recent study demonstrated that a bICP0 zinc RING finger point mutant virus grows poorly compared to the rescued virus when cells are pretreated with imiquimod (30), a known activator of IFN expression (26). This result suggested that bICP0 can stimulate virus growth during an IFN response. Mice lacking type I and type II IFN receptors die within a few days following infection with BHV-1 or BHV-5 (1). In contrast, wt mice survive infection with BHV-1 (1). Thus, the ability of bICP0 to inhibit the trans-activation potential of IRF3 and IRF7 appears to play an important role in stimulating productive infection and regulating BHV-1 pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported primarily by two USDA grants (08-00891 and 06-01627). A National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant (R21AI069176) to C.J. and a Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence grant (1P20RR15635) to the Nebraska Center for Virology also supported certain aspects of the study.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 January 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abril, C., M. Engels, A. Limman, M. Hilbe, S. Albini, M. Franchini, M. Suter, and M. Ackerman. 2004. Both viral and host factors contribute to neurovirulence of bovine herpesvirus 1 and 5 in interferon receptor-deficient mice. J. Virol. 783644-3653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Au, W. C., P. A. Moore, D. W. LaFleur, B. Tombal, and P. M. Pitha. 1998. Characterization of the interferon regulatory factor-7 and its potential role in the transcription activation of interferon A genes. J. Biol. Chem. 27329210-29217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boutell, C., and R. D. Everett. 2003. The herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) regulatory protein ICP0 interacts with and ubiquitinates p53. J. Biol. Chem. 27836596-36602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boutell, C., S. Sadis, and R. D. Everett. 2002. Herpes simplex virus type 1 immediate-early protein ICP0 and its isolated RING finger domain act as ubiquitin E3 ligases in vitro. J. Virol. 76841-850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowles, D. E., V. R. Holden, Y. Zhao, and D. J. O'Callaghan. 1997. The ICP0 protein of equine herpesvirus 1 is an early protein that independently transactivates expression of all classes of viral promoters. J. Virol. 714904-4914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowles, D. E., S. K. Kim, and D. J. O'Callaghan. 2000. Characterization of the trans-activation properties of equine herpesvirus 1 EICP0 protein. J. Virol. 741200-1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devireddy, L. R., and C. Jones. 1999. Activation of caspases and p53 by bovine herpesvirus 1 infection results in programmed cell death and efficient virus release. J. Virol. 733778-3788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diao, L., B. Zhang, J. Fan, X. Gao, S. Sun, K. Yang, D. Xin, N. Jin, Y. Geng, and C. Wang. 2005. Herpes virus proteins ICP0 and BICP0 can activate NF-κB by catalyzing IκBα ubiquitination. Cell. Signal. 17217-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Everett, R., P. O'Hare, D. O'Rourke, P. Barlow, and A. Orr. 1995. Point mutations in the herpes simplex virus type 1 Vmw110 RING finger helix affect activation of gene expression, viral growth, and interaction with PML-containing nuclear structures. J. Virol. 697339-7344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Everett, R. D. 1988. Analysis of the functional domains of herpes simplex virus type 1 immediate-early polypeptide Vmw110. J. Mol. Biol. 20287-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Everett, R. D. 2000. ICP0, a regulator of herpes simplex virus during lytic and latent infection. Bioessays 22761-770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Everett, R. D., P. Barlow, A. Milner, B. Luisi, A. Orr, G. Hope, and D. Lyon. 1993. A novel arrangement of zinc-binding residues and secondary structure in the C3HC4 motif of an alpha herpes virus protein family. J. Mol. Biol. 2341038-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Everett, R. D., W. C. Earnshaw, J. Findlay, and P. Lomonte. 1999. Specific destruction of kinetochore protein CENP-C and disruption of cell division by herpes simplex virus immediate-early protein Vmw110. EMBO J. 181526-1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Everett, R. D., P. Lomonte, T. Sternsdorf, R. van Driel, and A. Orr. 1999. Cell cycle regulation of PML modification and ND10 composition. J. Cell Sci. 1124581-4588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Everett, R. D., M. Meredith, A. Orr, A. Cross, M. Kathoria, and J. Parkinson. 1997. A novel ubiquitin-specific protease is dynamically associated with the PML nuclear domain and binds to a herpesvirus regulatory protein. EMBO J. 161519-1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henderson, G., Y. Zhang, and C. Jones. 2005. The bovine herpesvirus 1 gene encoding infected cell protein 0 (bICP0) can inhibit interferon-dependent transcription in the absence of other viral genes. J. Gen. Virol. 862697-2702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Honda, K., H. Yanai, H. Negishi, M. Asagiri, M. Saton, T. Mizutani, N. Shimada, Y. Ohba, A. Takaoka, N. Yoshida, and T. Taniguchi. 2005. IRF-7 is the master regulator of type-I interferon-dependent immune responses. Nature 434772-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inman, M., Y. Zhang, V. Geiser, and C. Jones. 2001. The zinc ring finger in the bICP0 protein encoded by bovine herpes virus-1 mediates toxicity and activates productive infection. J. Gen. Virol. 82483-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones, C. 2003. Herpes simplex virus type 1 and bovine herpesvirus 1 latency. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1679-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lees-Miller, S. P., M. C. Long, M. A. Kilvert, V. Lam, S. A. Rice, and C. A. Spencer. 1996. Attenuation of DNA-dependent protein kinase activity and its catalytic subunit by the herpes simplex virus type 1 transactivator ICP0. J. Virol. 707471-7477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lium, E. K., and S. Silverstein. 1997. Mutational analysis of the herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP0 C3HC4 zinc ring finger reveals a requirement for ICP0 in the expression of the essential α27 gene. J. Virol. 718602-8614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marié, I., E. Smith, A. Prakash, and D. E. Levy. 2000. Phosphorylation-induced dimerization of interferon regulatory factor 7 unmasks DNA binding and a bipartite transactivation domain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 208803-8814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marié, I., J. E. Durbin, and D. E. Levy. 1998. Differential viral induction of distinct interferon-alpha genes by positive feedback through interferon regulatory factor-7. EMBO J. 176660-6669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maul, G. G., and R. D. Everett. 1994. The nuclear location of PML, a cellular member of the C3HC4 zinc-binding domain protein family, is rearranged during herpes simplex virus infection by the C3HC4 viral protein ICP0. J. Gen. Virol. 751223-1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maul, G. G., H. H. Guldner, and J. G. Spivack. 1993. Modification of discrete nuclear domains induced by herpes simplex virus type 1 immediate early gene 1 product (ICP0). J. Gen. Virol. 742679-2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Megyeri, K., W.-C. Au, I. Rosztoczy, N. Babu, K. Raj, R. L. Miller, M. A. Tomai, and P. M. Pitha. 1995. Stimulation of interferon and cytokine gene expression by imiquimod and stimulation by Sendai virus utilize similar signal transduction pathways. Mol. Cell. Biol. 152207-2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parkinson, J., and R. D. Everett. 2000. Alphaherpesvirus proteins related to herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP0 affect cellular structures and proteins. J. Virol. 7410006-10017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parkinson, J., S. P. Lees-Miller, and R. D. Everett. 1999. Herpes simplex virus type 1 immediate-early protein vmw110 induces the proteasome-dependent degradation of the catalytic subunit of DNA-dependent protein kinase. J. Virol. 73650-657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saira, K., Y. Zhou, and C. Jones. 2007. The infected cell protein 0 encoded by bovine herpesvirus 1 (bICP0) induces degradation of interferon response factor 3 (IRF3), and consequently inhibits beta interferon promoter activity. J. Virol. 813077-3086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saira, K., S. Chowdhury, N. Gaudreault, L. da Silva, G. Henderson, A. Doster, and C. Jones. 2008. The zinc RING finger of the bovine herpesvirus 1-encoded bICP0 protein is crucial for viral replication and virulence. J. Virol. 8212060-12068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sato, M., N. Tanaka, N. Hata, E. Oda, and T. Taniguchi. 1998. Involvement of the IRF family transcription factor IRF-3 in virus-induced activation of the IFN-beta gene. FEBS Lett. 425112-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tikoo, S. K., M. Campos, and L. A. Babiuk. 1995. Bovine herpesvirus 1 (BHV-1): biology, pathogenesis, and control. Adv. Virus Res. 45191-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Sant, C., R. Hagglund, P. Lopez, and B. Roizman. 2001. The infected cell protein 0 of herpes simplex virus 1 dynamically interacts with proteasomes, binds and activates the cdc34 E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, and possesses in vitro E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 988815-8820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winkler, M. T., A. Doster, and C. Jones. 1999. Bovine herpesvirus 1 can infect CD4+ T lymphocytes and induce programmed cell death during acute infection of cattle. J. Virol. 738657-8668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang, H., G. Ma, C. H. Lin, M. Orr, and M. G. Wathelet. 2004. Mechanism for transcriptional synergy between interferon regulatory factor (IRF)-3 and IRF-7 in activation of the interferon-beta gene promoter. Eur. J. Biochem. 2713693-3703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang, L., and J. S. Pagano. 2000. Interferon regulatory factor 7 is induced by Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1. J. Virol. 741061-1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang, Y., and C. Jones. 2005. Identification of functional domains within the bICP0 protein encoded by BHV-1. J. Gen. Virol. 86879-886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]