Abstract

We constructed foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) mutants bearing independent deletions of the two stem-loop structures predicted in the 3′ noncoding region of viral RNA, SL1 and SL2, respectively. Deletion of SL2 was lethal for viral infectivity in cultured cells, while deletion of SL1 resulted in viruses with slower growth kinetics and downregulated replication associated with impaired negative-strand RNA synthesis. With the aim of exploring the potential of an RNA-based vaccine against foot-and-mouth disease using attenuated viral genomes, full-length chimeric O1K/C-S8 RNAs were first inoculated into pigs. Our results show that FMDV viral transcripts could generate infectious virus and induce disease in swine. In contrast, RNAs carrying the ΔSL1 mutation on an FMDV O1K genome were innocuous for pigs but elicited a specific immune response including both humoral and cellular responses. A single inoculation with 500 μg of RNA was able to induce a neutralizing antibody response. This response could be further boosted by a second RNA injection. The presence of the ΔSL1 mutation was confirmed in viruses isolated from serum samples of RNA-inoculated pigs or after transfection and five passages in cell culture. These findings suggest that deletion of SL1 might contribute to FMDV attenuation in swine and support the potential of RNA technology for the design of new FMDV vaccines.

Foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) is a member of the Picornaviridae family and the causative agent of an acute vesicular disease considered a major animal health problem worldwide, affecting pigs, ruminants, and other cloven-hoofed livestock (32, 53). The virus consists of a nonenveloped particle enclosing a single-stranded positive-sense RNA molecule of about 8.5 kb in length, with the viral protein VPg covalently linked to the 5′ end and a poly(A) tract at the 3′ end. The viral genome contains a single open reading frame flanked by two highly structured noncoding regions (NCRs) at their 5′ and 3′ termini, respectively (7). The 5′ NCR, approximately 1,300 nucleotides in length, includes sequences required for the initiation of replication and translation, comprising the S fragment, a 360-nucleotide-long region predicted to form a large hairpin structure (23, 62), a poly(C) tract, multiple pseudoknots, the cis replication element (cre) (38), and the internal ribosome entry site (IRES) (37). The 3′ NCR is a sequence of about 100 nucleotides predicted to be structured in two stem-loops, SL1 and SL2 (55). We have previously shown the strict requirement of the 3′ NCR for FMDV infectivity and replication (52) and the stimulatory effect of this region on IRES-dependent translation, even in the absence of a poly(A) tail (36). Moreover, the 3′ NCR interacts with the IRES and S regions located at the 5′ end through direct RNA-RNA interactions (55). Cellular proteins binding to the 3′ NCR have also been described (36, 48). Some of these factors are also able to interact with the S region and undergo proteolytic cleavage upon FMDV infection (48). The putative role of these interactions in circularization of the FMDV genome has been suggested (55).

Information available from picornaviruses of the genus enterovirus shows that complete deletion of the 3′ NCR (oriR) may yield viable viruses without any compensating mutations in their genomes, while partial distortions of the individual structural domains forming the oriR (45) generally result in the loss of virus viability (11, 58, 59). An intramolecular “kissing” interaction between the X and Y domains was found to be crucial for an efficient functioning of the oriR in virus replication (42, 46). Interestingly, a coxsackievirus B3 mutant with a deletion of the enterovirus B-like-specific Z domain, fully infectious in cell culture, resulted in reduced virulence for mice, suggesting that the Z domain plays a role in virus replication in vivo (43). Consistent with that, domain Z has been implicated in cellular tropism involving cis-acting interactions with the IRES (19).

With the aim of further characterizing the functional structures comprising the FMDV 3′ NCR, independent deletions of the two predicted stem-loops were performed on a full-length (FL) infectious FMDV clone. Our results show that SL2 is essential to preserve viability of the virus, while SL1 could be deleted without a loss of infectivity. Interestingly, the ΔSL1 mutation yielded viruses with a diminished replication capacity and small-plaque phenotype in IBRS-2 cells.

The involvement of the 3′ NCR in controlling the processes of replication and translation of the viral RNA highlights its relevance in the infectious cycle and makes this region a suitable candidate for antiviral and vaccination strategies. RNA vaccines seem particularly appropriate for picornaviruses, since their positive-sense single-stranded RNA genomes are infectious and can be mutated to reduce viral production. Attenuated variants can be engineered on FL infectious clones, allowing the construction of safe and efficient candidate vaccines in which specific markers can be introduced.

In this work, we also addressed the feasibility of immunization of swine using self-replicating FMDV RNA. Inoculation of pigs with fully infectious transcripts mimicked natural FMDV infection in clinical signs of disease, viremia, and induction of specific antibody response. Moreover, we were able to elicit both humoral and cellular immune responses in swine in the absence of any sign of disease by inoculation of RNA transcripts derived from an FMDV infectious clone in which SL1 had been deleted from the 3′ NCR of the genome. The replication capacity and stability of this mutant were analyzed in cell culture and swine. Our results suggest that RNA-based foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) vaccines can be successfully applied to large host animals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids and RNA synthesis.

The plasmid pO1K-ΔSL1 was generated by recombinant PCR using the pO1K plasmid (pDM construct [52]) as a template. The resultant clone has a deletion of nucleotides 4 to 33 from the viral RNA stop codon, spanning SL1 of the FMDV 3′ NCR. Conversely, the plasmid pO1K-ΔSL2 was made to carry a deletion of nucleotides 50 to 83, enclosing SL2 from the 3′ NCR. A second mutagenesis round was performed to introduce the VP3 Arg56His substitution for reversion of the attenuation phenotype in cattle reported for type O isolates carrying Arg56 (49). This second mutagenesis was applied to the pO1K, pO1K-ΔSL1, and pO1K-ΔSL2 clones, generating the corresponding VP3-H56 derivatives. The plasmid pO1K/C-S8 has been described previously (5). The presence of the corresponding mutations was verified by sequence analysis.

For RNA synthesis, plasmids were linearized with HpaI (New England Biolabs) and in vitro transcribed using SP6 RNA polymerase (Promega). After transcription, the reaction mixture was treated with RQ1 DNase (1 U/μg RNA; Promega). Then, RNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform and precipitated with ethanol. The RNA integrity and concentration were determined by electrophoresis on agarose gels.

Transfection and quantification of FMDV RNA.

In vitro-transcribed RNAs were transfected (for ∼8 h) into IBRS-2 or BHK-21 cells using the Lipofectin reagent (Invitrogen) (52). Cells were maintained at 37°C in Dulbecco's modified Eagle′s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Cytoplasmic RNA was extracted at various time points postransfection (p.t.) as described previously (52) and quantified in a NanoDrop spectrophotometer ND-1000 (Thermo Scientific). Equal amounts of cytoplasmic RNA from cells transfected with O1K-ΔSL1(VP3-R56) or O1K-FL(VP3-R56) RNAs were used for quantification of positive- and negative-sense FMDV RNA by real-time reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) using a LightCycler instrument (Roche). The primers used (A and B), reported to amplify a 290-bp conserved region in the 3D gene by conventional RT-PCR (51), were adapted to real-time RT-qPCR. Amplification of negative-strand viral RNA was achieved by attaching to the 5′ terminus of forward primer B a heterologous tag sequence corresponding to positions 3,663 to 3,681 of the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus RNA, as described previously (29). RNA was reverse transcribed with Transcriptor RT (Roche) using either primer A or tag B to amplify positive- or negative-strand RNA, respectively. Real-time quantitative PCR was performed using LightCycler FastStart DNA Master SYBR green I (Roche). PCR conditions were as follows: 95°C for 10 min (1 cycle) and then 55 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 55°C for 5 s, and 72°C for 5 s. Primers A and B were used for amplification of positive-strand RNA and primers pair A and tag for negative-strand RNA, respectively. The RNA copy number in each sample was determined by standard curves generated in parallel using either positive-sense RNA transcribed from the pO1K clone or negative-sense RNA generated from a plasmid containing the FMDV 3D region (29), kindly provided by E. Domingo. The viral load in selected serum samples from RNA inoculated pigs was determined as described above for positive-sense RNA quantification.

Viral growth curves.

Subconfluent IBRS-2 cell monolayers were infected with O1K-ΔSL1 or O1K-FL viruses (both VP3-R56) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1. These viruses were recovered from transfection and one (O1K-FL) or two and five passages (O1K-ΔSL1) on IBRS-2. After 1 h of adsorption, cells were washed and incubated at 37°C with DMEM supplemented with 2% FBS. At several time points postinfection, supernatants were collected and frozen at −70°C. Titers of virus were determined by plaque assay with serial dilutions of the collected supernatants on IBRS-2 cells. After 1 h of adsorption, cells were washed and a 0.6% agar overlay in DMEM with 1% FBS was added. Cells were fixed 24 or 48 h postinfection for O1K-FL or O1K-ΔSL1, respectively, with 10% formaldehyde and stained with crystal violet.

Inoculation of pigs with FMDV RNA.

White crossbred Landrace female pigs weighing approximately 20 Kg were used for the study and housed in biosecure (BSL-3) animal facilities. Different amounts of RNA transcripts, suspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 40 μg of the Lipofectin reagent (Invitrogen) in a total volume of 200 μl, were given by intradermal inoculation in the coronary band. In a first experiment, three pigs were given 150, 300, or 500 μg of O1K/C-S8 RNA (pigs 1, 2, and 3), respectively. One uninoculated pig was housed in the same room as a contact during the study. Pig 1 was euthanized at day 22 postinoculation (p.i.), pig 2 at day 4 p.i., and pigs 3 and the contact at day 8 p.i. Blood (serum) sampling was done at different times p.i. Vesicular fluid and epithelium samples from animals developing lesions were collected. Lymph node samples were taken from pigs 2 and the contact during slaughtering. In a second experiment, aiming to address the immunogenic capacity of O1K-ΔSL1(VP3-H56) RNA, two groups of four animals were housed in separate rooms. All of these eight animals (groups 1 and 2) were given 500 μg of O1K-ΔSL1 RNA. On day 24 after the first inoculation, pigs in group 1 (animals 1 to 4) were given a booster dose of 500 μg of O1K-ΔSL1(VP3-H56) RNA by the same route as described above. After RNA inoculations, animals were examined daily for fever and clinical signs of FMD. Sampling of blood (sera) was done at different days p.i., and nasal swabs were taken at days 3, 4, 5, and 6 p.i.

Assay for virus.

The infectivity in serum, nasal swabs, or vesicular fluid samples was assayed by inoculation on IBRS-2 cells as described previously (24). Development of a cytopathic effect (CPE) was monitored for 72 h postinfection. When the CPE was not detected, three blind passages were performed after three thaw-freezing cycles. The specificity of the CPE observed was confirmed by RT-PCR (51) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with monoclonal antibody SD6 against the VP1 capsid protein (39). Samples were scored as negative when no CPE was detected after three blind passages.

Detection and sequencing of viral RNA.

Serum was separated immediately from blood aliquots, and swabs were solubilized in 500 μl of PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Vesicular epithelium and lymph node samples were homogenized in PBS. Total RNA was extracted from samples using the Tri reagent (Sigma). Each extraction required 100 to 200 μl of sample, and the RNA was finally resuspended in a volume of 20 μl of diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water. One μl of each RNA was assayed in an RT-PCR designed to amplify a 290-bp fragment in the 3Dpol gene of the FMDV viral genome. The detection limit of the assay for O1K RNA was 10−2 PFU (51).

To obtain complete genome sequences of viruses recovered from transfections and infections, RNA was extracted as described above and retrotranscribed using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Then, six overlapping fragments spanning the whole genome were amplified using the Expand High Fidelity polymerase system (Roche) and primers designed to anneal to O1K-specific sequences.

To confirm the presence of the ΔSL1 mutation in viral RNA amplified from pig samples, the sequence of the 3′ end region was determined after RT-PCR amplification as follows. An RT reaction using the primer ANCHOR (5′-TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTGG-3′) was performed, followed by two cycles of PCR amplification. The first used the primers SEQC-I (5′-CTCTTTGAGCCTTTCCAAGG-3′; 87 nucleotides upstream from the stop codon) and ANCHOR, and the second used the primers SB12 (5′-TTTTTTTTTTGGATTAAGGAAGCGGGAA-3′) and SEQUINT (5′-CCAAGGTCTCTTTGAGATTCC-3′; 73 nucleotides upstream from the stop codon). The presence of His56 in the VP3 gene was confirmed by sequencing of the amplimers obtained after reverse transcription as described above with primer SB6 (4) and two rounds of PCR using SB5 (4) and SB6 for the first and the internal primers si56 (5′-ATCACAGTGCCCTTTGTTGG-3′; O1K nucleotides 2042 to 2061) and OAR56 (5-GCGTCGCCGTCGGCCTTGCCATGTG-3′; reverse of O1K nucleotides 2793 to 2817) for the second. O1K nucleotide positions are referenced to the EMBL PIFMDV2 sequence (accession number X00871).

Antibody detection.

Specific antibodies in sera against whole virus were detected by a trapping ELISA against unpurified C-S8c1 captured by a rabbit anti-serotype C serum (provided by the IAH, Pirbright, United Kingdom) using anti-swine immunoglobulin (Ig)-horseradish peroxidase (Dako). Antibodies against the nonstructural protein precursor 3ABC were also detected by ELISA as described previously (9), adapted to swine sera, which were tested in threefold dilutions beginning from a 1:50 dilution. For each animal, serum collected at day 0 was included as the corresponding negative control. Titers in the ELISA were expressed as the log10 of the highest serum dilution with an optical density at 450 nm (OD450) greater than at least twice the OD of the negative control serum mean. For IgA isotype-specific detection, a monoclonal antibody specific for porcine IgA from Serotec was used, followed by incubation with goat antimouse-horseradish peroxidase from Bio-Rad. Sera were tested at 1:50, 1:100, and 1:200 dilutions. IgA titers were expressed as the OD450 ratio of the corresponding serum versus that of the preimmune serum (day 0). Neutralizing antibodies were determined by a plaque reduction neutralization assay (39). Sera were tested in fivefold dilutions, with 1:20 being the first dilution assayed. Neutralization titers were expressed as the reciprocal of the serum dilution (log10) that caused 50% of plaque reduction.

Lymphocyte proliferation assay.

Blood aliquots collected with 5 mM EDTA were used to obtain peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) after Ficoll-Paque purification (Pharmacia). The total number of live PBMC recovered was estimated by trypan blue staining. Purified cells were used to test the specific proliferative responses to FMDV as described previously (27, 28). Briefly, 2.5 × 105 live PBMC/well were plated in 96-well round-bottomed microtiter plates in RPMI-10% FBS. Triplicate wells of cells were stimulated with two different doses of FMDV (1.5 × 105 or 6.2 × 105 PFU) for 3 days at 37°C in 5% CO2. As controls, triplicates of cells were incubated in the absence of virus (negative control) or with concanavalin A (2.5 μg/well) (positive control). Three days after stimulation, each well was pulsed for 18 h with 0.5 μCi of [methyl-3H]thymidine (Amersham), and the radioactivity incorporated in harvested cells was measured. Results were expressed as the stimulation index (cpm in sample/cpm in medium alone). To obtain further information regarding the pathway of antigen presentation inducing the lymphoproliferative responses, stimulation was performed in the presence of saturating concentrations of monoclonal antibody 4B7 (13) or 1F12 (12) (kindly provided by J. Domínguez), which block porcine major histocompatibility complex (MHC) (SLA) class I or class II presentation, respectively.

Statistical analysis.

Data are presented as means ± standard deviations. A one-way analysis of variance and Bonferroni's correction for multiple comparisons were used to determine statistical significance (P < 0.05).

RESULTS

Deletion of stem-loop I from the FMDV 3′ NCR reduced viral growth and replication in cell culture.

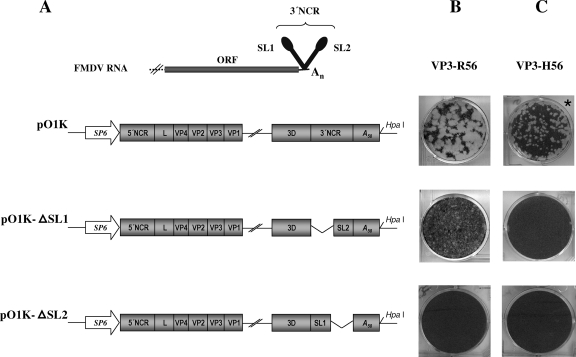

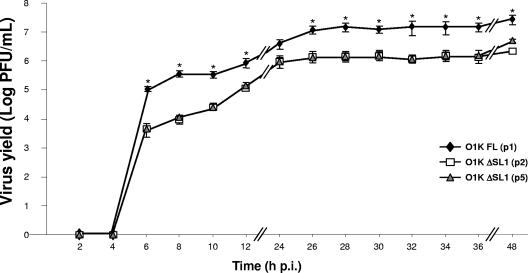

We demonstrated in previous work the essentiality of the 3′ NCR for FMDV RNA infectivity and proved its involvement in replication and translation, as well as interaction with cellular proteins, presumably playing a role in regulation of both processes (36, 48, 52, 55). RNAs bearing a deletion of the complete 3′ NCR were unable to infect cells due to their impaired replicative capacity (52). As a continuation of these studies, independent deletions of the two structural domains predicted in the 3′ NCR (55) were performed on the FMDV pO1K FL clone (Fig. 1A). The infectivities of the corresponding mutants as determined by plaque assay on IBRS-2 cells is shown in Fig. 1B. Deletion of SL2 was lethal for viral infectivity, since no viable virus was recovered from transfections and two blind passages. However, deletion of SL1 did not abrogate viral infectivity, although a delay in CPE development and different plaque morphology could be observed (Fig. 1B). IBRS-2 monolayers transfected with ΔSL1 RNA led to a detectable CPE 40 h p.t., about 24 h later than transfection with transcripts of the FL viral construct. Viruses generated from ΔSL1 RNA produced small pinpoint plaques compared to O1K-FL RNA. The small-plaque phenotype was maintained after at least five passages in IBRS-2 and BHK-21 cells (not shown). The infectivity of ΔSL1 transcripts on IBRS-2 cells was about 103 PFU/μg RNA, approximately 10-fold lower than that of FL viral transcripts (52). To examine their replication capacities, the growth kinetics of the ΔSL1 mutant was compared to that of parental FL virus (Fig. 2). Cells were infected at a MOI of 0.1 using O1K-FL or -ΔSL1 viral stocks subjected to titer determination by plaque assay. The comparative growth of the viruses indicated about 10-fold-lower levels of replication for the mutant than for the FL virus. Growth kinetics of the ΔSL1 mutant after two and five passages of the transfection supernatant on IBRS-2 cells were similar, showing that the mutant was unable to reach the growth levels of parental virus even after five passages on cell culture.

FIG. 1.

Effect of deletions of the 3′ NCR stem-loop structures on FMDV replication in cell culture. (A) Schematic representation of the viral genomes used in this study. (B and C) RNA transcripts of the FMDV O1K cDNAs were transfected into IBRS-2 cells, and the number and morphology of plaques formed by the resulting viruses were determined by plaque assay. Plaques corresponding to VP3-R56 clones at 40 h p.t. (B) or VP3-H56 clones at 48 h p.t. (C) are shown. *, cells at 48 h postinfection with the transfection supernatant.

FIG. 2.

Growth curves of FMDV O1K (VP3-R56) FL virus and the ΔSL1 mutant in IBRS-2 cells. Cells were infected at a MOI of 0.1 with viral stocks recovered after transfection and one passage of FL virus or after a second or fifth passage of ΔSL1 on IBRS-2, respectively. Numbers of PFU were determined at the indicated time points by plaque assay. The mean values of three experiments are shown. Error bars indicate standard deviations. Asterisks denote time points with statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) between ΔSL1 viruses (p2 and p5) and FL virus (p1).

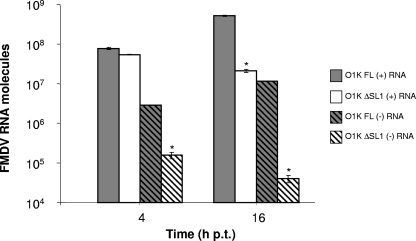

In order to further characterize the kinetics of replication of the ΔSL1 mutant bearing a deletion in cis-acting structural domains, presumably involved in RNA synthesis, intracellular viral positive- and negative-strand RNAs were quantified in transfected BHK-21 cells by means of real-time RT-qPCR (Fig. 3). A decrease of ∼1.2 log in positive-strand RNA levels was observed at 16 h p.t. in cells transfected with the ΔSL1 mutant relative to levels of FL viral RNA. When negative-strand RNA levels were compared, relevant differences in negative-strand RNA synthesis were found between FL RNA and the ΔSL1 mutant (about 20-fold) at 4 h p.t., when no CPE was yet observed in transfected cells. This difference increased over time, reaching values up to 300-fold at 16 h p.t., when cells transfected with FL RNA were entering the cytopathology phase but were still attached to the plates, while cells transfected with the ΔSL1 mutant had not developed any sign of CPE. The ratio of positive- versus negative-strand viral RNA in transfected cells was ∼10-fold higher for the ΔSL1 mutant than for FL RNA at both 4 and 16 h p.t. These results show that deletion of SL1 yielded mutant viruses with a defect in negative-strand RNA synthesis.

FIG. 3.

Quantification of intracellular positive- or negative-strand FMDV RNA molecules by real-time RT-qPCR in BHK-21 cells transfected with O1K (VP3-R56) FL or ΔSL1 transcript, respectively. Each value represents the mean ± standard deviation (error bar) of RNA copy numbers per ng of cytoplasmic RNA extracted from transfected cells from quadruplicate determinations. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) between results for ΔSL1 and FL positive- or negative-strand RNAs at each time point.

To address whether the ΔSL1 mutant genotype was genetically stable over passage on cell culture, we determined the 3′-terminal sequences of the viruses recovered from duplicate transfections and their corresponding first and fifth passages on BHK-21 and IBRS-2 cells, respectively. In all cases, the presence of the ΔSL1 mutation with no additional changes was confirmed. The complete genome sequences of viruses recovered after transfection and first and fifth passages on BHK-21 cells were determined. All viruses recovered after first and fifth passages on BHK-21 cells included the amino acid replacements Lys-90 → Thr and Thr-63 → Lys in the 2C and 3C nonstructural proteins, respectively (not shown). Thr-63 in the 3C protein, unlike the case for position 90 in the 2C protein, is a widely conserved residue among FMDV isolates (14), though an Asia1-type Indian isolate with an Ala-63 residue has been reported (Asia1 IND/182/02; GenBank accession no. DQ989320). None of these positions, as far as we know, have been reported as relevant for functionality in their corresponding viral nonstructural proteins. Viruses carrying those changes exhibited the same growth and plaque phenotype as the ΔSL1 virus, maintaining the O1K wild-type sequence. No substitutions relative to the wild-type O1K sequence could be found in the region spanning the 2A through 3C genes of ΔSL1 viruses recovered from parallel experiments performed with the porcine IBRS-2 cell line.

Taken together, all these results indicate that deletion of SL1 from the FMDV 3′ NCR yielded viable viruses with reduced growth in cell culture and impaired viral replication. Unlike SL2, SL1 was not essential for replication, likely functioning as an enhancer of the process. This strongly suggests that deletion of SL1 might lead to viral attenuation.

Inoculation of pigs with in vitro-transcribed FMDV RNA generated infectious virus and induced clinical signs of disease.

To explore the feasibility of RNA-based genetic immunization using FMDV transcripts, we first tested the generation of infectious virus in swine upon inoculation with different amounts of O1K/C-S8 RNA (Table 1), derived from a chimeric cDNA carrying the type-C structural proteins within the O1K backbone (5). O1K/C-S8 transcripts had proved to be lethal for suckling mice, unlike transcripts derived from pO1K (4). As shown in Table 1, all three animals inoculated with O1K/C-S8 viral transcripts, regardless of the RNA dose, displayed typical clinical signs of FMD within 2 to 4 days after inoculation. The number and size of lesions were undistinguishable from those developed by animals experimentally infected with live virus. Interestingly, an uninoculated contact animal housed in the same room developed FMD 7 days p.i., indicating that the virus generated upon RNA inoculation was able to be excreted and transmitted to healthy animals following standard patterns of disease, as in field and experimental infections (2, 20).

TABLE 1.

Pigs inoculated with FMDV O1K/C-S8 transcripts developed disease and generated specific antibodies

| Animal | RNA dose (μg) | Day p.i. of:

|

Neutralizing antibody titer (day p.i.)g | ELISA antibody titer (day p.i.)h

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Development of clinical signs of diseasea | Positive RT-PCR detectionb | Anti-type C | Anti-3ABC | |||

| 1 | 150 | 3 | 3c | >3.4 (22) | 2.6 (22) | 3.6 (22) |

| 2 | 300 | 2 | 3d, 4c,e | 1.7 (4) | NDi | ND |

| 3 | 500 | 4 | 4f* | 1.6 (4) | ND | 2.2 (4) |

| Contact | 0 | 7 | 8c,d,e | 2.6 (8) | ND | ND |

Day p.i. when first clinical signs of disease were manifested (vesicular lesions and fever). Euthanasia was performed at day 22 p.i. (pig 1), 4 p.i. (pig 2), or 8 p.i. (pig 3 and contact).

Numbers indicate the day p.i. when sample was collected. The asterisk indicates the sample from which infectious virus was isolated.

Vesicular epithelium.

Serum.

Lymph nodes.

Vesicular fluid.

Titers are expressed as the reciprocal of the highest serum dilution (log10) that caused 50% of plaque reduction. Serum samples were taken at the day p.i. indicated in parenthesis.

Titers are expressed as the reciprocal of the of the highest serum dilution (log10) with an OD450 greater than twice the negative control mean. Serum samples were taken at the day p.i. indicated in parenthesis.

ND, not determined.

The presence of viral RNA in different samples collected at several times p.i. was confirmed by RT-PCR detection (Table 1), and fully infectious virus could be isolated in cell culture from vesicular fluid of a foot lesion from pig 3. In this sample, viral antigen was detected by ELISA (data not shown). Moreover, sera collected from all four swine showed significant neutralization titers, and high levels of antibodies to the structural and nonstructural 3ABC proteins were also detected (Table 1). These results demonstrate the feasibility of using RNA inoculation to elicit specific antibodies against FMDV in swine.

Replication in cells and mice of O1K-FL, -ΔSL1, and -ΔSL2 viruses carrying VP3-H56.

After the encouraging results obtained from pigs inoculated with O1K/C-S8 transcripts, we aimed to study the immunogenic capacity of the ΔSL1 mutant in pigs as self-replicating RNA yielding potentially attenuated viruses.

The amino acid substitution H56R in the FMDV VP3 capsid protein, present in the pO1K clone and derivatives, is known to greatly account for viral attenuation in bovines and is associated with adaptation to cell culture and increased affinity for heparin (31, 49). Consistently, O1K-FL transcripts derived from the parental pO1K clone were previously found to be uninfectious for mice (4). With the aim to give ΔSL1 transcripts a chance to express the viral proteins at the necessary level to induce a detectable immune response upon inoculation in susceptible animals, wild-type His was restored in position 56 of all constructs. Transcripts generated from the new constructs were first tested for infectivity in cell culture. As shown in Fig. 1C, infectious viruses could be recovered from transfections with RNA derived from pO1K-FL(VP3-H56), though complete development of a CPE was observed only after one passage on IBRS-2 cells. After a second passage in cell culture, only Arg was found in position VP3-56 and no His could be detected. In contrast, VP3-H56 in the ΔSL1 mutant induced a complete loss of infectivity, since no CPE could be observed after three blind passages. As expected, the O1K-ΔSL2(VP3-H56) mutant was not able to infect cells (Fig. 1C). The virulence of all transcripts carrying VP3-H56 was then tested in suckling mice as described previously (4), and none of the mutants was lethal after inoculation of RNA amounts up to 100 μg, as was also the case for their VP3-R56 counterparts (not shown). This result indicates that the VP3 R56H substitution itself was not sufficient to revert the attenuated phenotype of the O1K RNA in mice.

O1K-ΔSL1(VP3-H56) RNA is attenuated in swine.

The lack of amplification of O1K-ΔSL1(VP3-H56) virus in cell culture and the noninfectious phenotype observed in suckling mice strongly suggested that deletion of SL1 was affecting FMDV virulence. Then, we wanted to determine whether this FMDV mutant genome was attenuated in the natural host and study the clinical and immune responses to inoculation with the corresponding mutant RNA transcripts in swine. For that purpose, experimental inoculation of two groups of animals was carried out (Table 2). All of them were given 500 μg of O1K-ΔSL1(VP3-H56) transcripts. Group 1, including animals 1 to 4, received a second dose of RNA at day 24 p.i. Clinical parameters such as rectal temperature, appetite, and fecal consistency remained normal, and none of the animals developed vesicular lesions throughout the experiment (up to 45 days after first inoculation). Once it was proved to be innocuous for pigs, we tried to detect viral mutant RNA in serum and nasal swabs, collected at different times p.i., as an evidence of viral replication. Positive RT-PCR amplification was detected in serum at day 12 p.i. for all animals and earlier for three of them (see Table 2). After a second injection, viral RNA could be detected in two pigs of group 1 (days 11 and 17 after boosting for pigs 4 and 1, respectively) (Table 2). On day 45 p.i., viral RNA was not detected in serum from any of the eight inoculated animals. The amplification products were in all cases detected as a faint band in a highly sensitive assay. These results demonstrated the high attenuation level of O1K-ΔSL1(VP3-H56) RNA in swine, since none of the inoculated animals showed any sign of disease after one or two doses of 500 μg of transcripts. The onset of viremia exhibited by the virus generated was consistent with a low level of replication extended over time, in contrast with results for experimental infection with virus (2) or with FMDV O1K/C-S8 RNA (Table 1, pig 2), both showing a peak around days 2 and 4 p.i. as an average. Our failure to detect virus in nasal swabs from inoculated animals, even at time points when serum samples were RT-PCR positive (Table 2, pigs 1 and 8), indicated the limited replication of the mutant, which was unable to reach this area, critical for virus excretion. The viral load in serum from pig 1 at day 10 p.i. was determined by RT-qPCR to be 1 × 107 viral genomes per ml of serum. This is about 102-fold lower than viremia levels reported for pigs inoculated with fully infectious type O FMDV (2). Although O1K-ΔSL1(VP3-H56) RNA was not able to grow on cell culture, we wanted to rule out the putative emergence of cytolytic variants. Our attempts to isolate virus in IBRS-2 cells from positive serum samples and the corresponding swabs from the same animal and time point failed even after three blind passages. The regions spanning the 3′ NCR, VP3, and 2C through 3C genes were amplified for sequence analysis from serum samples of pigs 1 and 2 collected at day 10 p.i. and pig 8 at day 4 p.i (data not shown). The presence of the SL1 deletion was confirmed, and no other changes or insertions were detected. In the three samples, His56 in the VP3 protein was confirmed as well. When the sequence of the region spanning the 2C through 3C genes was determined, as in porcine IBRS-2 cells, no substitution could be detected in the three samples relative to O1K wild-type sequence, unlike what was found in BHK-21 cells. These data support the in vivo stability of the O1K-ΔSL1(VP3-H56) mutant.

TABLE 2.

Detection of viral RNA by RT-PCR in serum samples from pigs inoculated with 500 μg of FMDV O1K-ΔSL1(VP3-H56) RNAa

| Animal | Detection of RNA at day (p.i.):

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 10 | 12 | 17 | 24b | 28 | 31 | 35 | 41 | 45 | |

| 1 | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| 2 | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 3 | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 4 | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | +c | ||

| 5 | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | |||||

| 6 | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | |||||

| 7 | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | |||||

| 8 | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | |||||

Viral RNA could not be detected in nasal swabs collected from all eight animals on days where results are highlighted in bold.

Animals 1 to 4 were boosted with 500 μg of O1K-ΔSL1(VP3-H56) RNA at day 24 after the first inoculation. Serum samples were taken prior to the boost, and thereafter sera were collected only from boosted animals.

Pig 4 died at day 35 p.i. during bleeding.

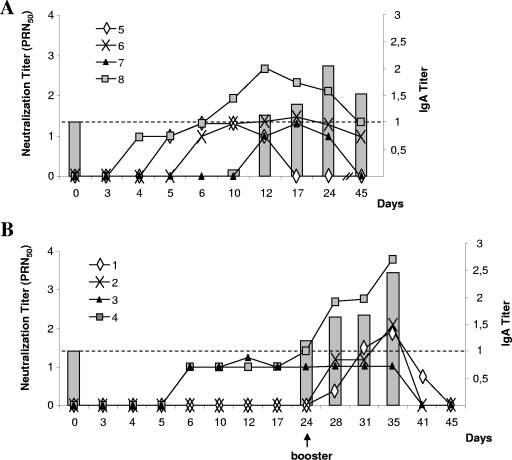

Immune responses induced after inoculation with O1K-ΔSL1(VP3-H56).

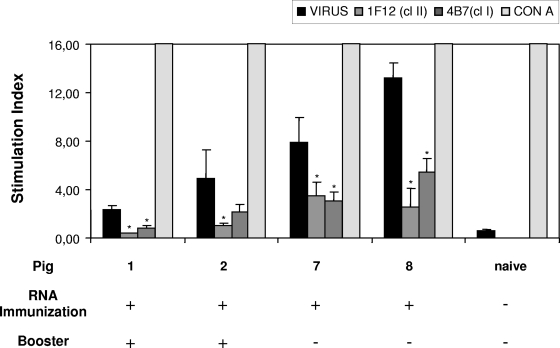

To determine whether inoculation with FMDV O1K-ΔSL1(VP3-H56) transcripts, despite the high levels of attenuation exhibited in pigs, was able to induce an immune response in the RNA-injected animals, neutralization and lymphocyte proliferation assays were performed. As shown in Fig. 4, a single immunization was sufficient to induce detectable levels of neutralizing antibodies in all four animals in group 2 (pigs 5 to 8), reaching the highest levels around day 12 p.i. Group 1 (pigs 1 to 4) showed higher interindividual variation. After a single RNA immunization, two out of four animals developed neutralizing antibodies, while a second RNA dose induced 100% seroconversion and increased significantly the neutralizing titers for pig 4. In the case of pigs 4 and 8, the levels of neutralizing response were equivalent to those induced with inactivated whole-virus vaccine (16, 41, 57). For pigs 4, 6, and 8, neutralizing antibodies were maintained for at least 35 to 45 days (Fig. 4). Systemic IgA responses were also examined for pigs 4 and 8 (Fig. 4). Induction of specific IgA in sera and upper mucosae has been correlated with protection in infected and vaccinated pigs (18, 22, 26). ELISA titers of >2 (corresponding to a 1:50 dilution of serum) were detected for both animals. In the case of pig 8, the IgA response was first detected at day 24 p.i. and decreased at day 45 p.i. For pig 4, induction of IgA was detected at day 35 p.i., 11 days after boosting. The IgA titers reached were similar to that of the ELISA-positive control serum used, collected after 15 days postinfection from a pig inoculated with type O virus (not shown). We also addressed the ability of the mutant transcripts to elicit a cellular immune response. Figure 5 shows the results of lymphocyte proliferation assays corresponding to those animals for which a specific stimulatory effect was detected 45 days after the first inoculation (and 21 days after boosting). Two of these animals had received a single RNA dose, and the other two had been given a booster dose at day 24 p.i. Interestingly, pig 8, showing the highest stimulation index, had received a single RNA dose. The high stimulation index obtained with concanavalin A in all cases (reaching values over 21) showed the unaffected capacity of lymphocytes to proliferate after 45 days of inoculation with viral RNA. Although we failed to detect significant stimulation in PBMC from the remaining animals, alternating periods of high and low T-cell responses have been previously reported for pigs and cattle (50). The significance of the results obtained was confirmed using specific antibodies directed against SLA classes I and II, respectively. Both antibodies had an inhibitory effect on stimulation of 56 to 83% (Fig. 5), revealing the involvement of both class I and class II pathways of antigen presentation in the lymphoproliferative responses detected. These results indicated that inoculation of O1K-ΔSL1(VP3-H56) RNA is able to elicit specific humoral and cellular immune responses.

FIG. 4.

Neutralizing antibody and IgA-specific responses induced in pigs upon inoculation with O1K-ΔSL1(VP3-H56) RNA. Pigs 5 to 8 (group 2) received a single RNA dose (A), and pigs 1 to 4 (group 1) were boosted with a second RNA inoculation 24 days after the first dose (B). Neutralization titers are expressed as the reciprocal of serum dilution (log10) causing 50% of plaque reduction (PRN50). IgA responses in sera from pigs 8 and 4 at the indicated days are plotted in panels A and B, respectively. IgA titers are expressed as the OD450 ratio of the corresponding serum at dilution 1:50 versus that of the serum collected at day zero.

FIG. 5.

Proliferative T-cell optimal responses to FMDV detected in pigs inoculated with O1K-ΔSL1(VP3-H56) RNA at day 45 p.i. (day 21 after boosting for pigs 1 and 2). The results of triplicate assays are shown as stimulation indexes using 1.5 × 105 PFU (pigs 1, 7, and 8) or 6.2 × 105 PFU (pig 2). Where indicated, cells were incubated in the presence of anti-swine MHC (SLA) class I (cl I) or class II (cl II) monoclonal antibody 4B7 or 1F12, respectively, or with concanavalin A (CON A). The cpm in control cultures were 6,893 (pig 1), 1,507 (pig 2), 300 (pig 7), and 1,180 (pig 8). Error bars indicate standard deviations. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) with the corresponding untreated cells.

DISCUSSION

In previous work, we have shown the relevance of the 3′ NCR in the FMDV RNA genome for the productive infectious cycle (52). Structural domains in this region have been identified to establish RNA-RNA interactions with cis-acting elements present in the 5′ end of the genome, involved in replication and translation. With the aim of further characterizing the functional structures forming the 3′ NCR, independent deletions of the two predicted stem-loops were performed on the FL infectious FMDV clone. Infectivity assays of the mutants in cell culture showed that SL2 was essential to preserve virus viability while deletion of SL1 allowed recovery of infectious viruses without a complete loss of infectivity. ΔSL1 viruses had a small-plaque phenotype and a reduced growth capacity, with titers consistently 10-fold lower than those of FL virus after serial passages on IBRS-2 cells. Quantification of the positive- or negative-strand viral RNA in cells transfected with either FL or ΔSL1 transcripts, respectively, showed that deletion of SL1 generated viruses with downregulated replication associated to a defect in negative-strand RNA synthesis, leading to differences of up to 300-fold in negative-strand RNA relative to results for FL RNA at late times p.t. Consistently, the ratio of positive- to negative-strand RNAs was 10-fold higher for the ΔSL1 mutant at the two times p.t. analyzed. It is worth noticing that an RNA probe resembling the 3′ terminus of the ΔSL1 virus, enclosing SL2 and poly(A), was shown to reproduce the interaction pattern of the entire 3′ NCR with the 5′-end S region (55). While SL2 seems to be strictly required for RNA synthesis, SL1 could be acting as a replication enhancer. It remains to be determined whether the ability of SL2 to mimic the interaction of the entire 3′ NCR with the S region could account for the preserved but diminished replication capacity of the ΔSL1 mutant. Although infectious clones bearing complete 3′ NCR deletions, enclosing both SL1 and SL2, were able to translate in vitro (52), the stimulatory effect exerted by the 3′-terminal sequences on IRES-dependent translation (36) might therefore be broken down in ΔSL1 viruses.

Previous work on enteroviruses shows that the 3′ NCR is dispensable for viral viability while the poly(A) tail, which is partly included in the stem-loop structure of domain X, is an element required for efficient replication and translation (64). This suggests that the basic mechanism for initiation of enterovirus replication is not strictly template specific (58). In the case of FMDV, some structural requirements seem to be necessary for negative-strand RNA synthesis, suggesting differences in the mechanism of recognition by the replication machinery.

The replication-defective phenotype exhibited by ΔSL1 virus in cell culture led us to explore the infectivity and potential use as an RNA-based vaccine in natural host animals of FMDV transcripts derived from infectious clones. For that purpose, the feasibility of immunization of swine with FMDV transcripts was first analyzed. Inoculation of pigs with O1K/C-S8 RNA, previously shown to be lethal for suckling mice (4), induced FMD symptoms and typical development of disease. The viruses generated upon inoculation were able to be excreted and infect a contact animal. Fully infectious virus could be detected and isolated in samples from inoculated and contact pigs, all developing high titers of specific anti-FMDV and neutralizing antibodies. These results demonstrate the capacity of FMDV RNA transcripts to induce disease in pigs, reproducing the typical patterns of FMD reported for viral infections. The RNA inoculation model of natural host species may be useful for virulence assays of viral genotypes and strongly supports the feasibility of genetically engineered RNA-based vaccine strategies for FMD control in large host animals.

With the aim of trying delivery of transcripts carrying the ΔSL1 mutation into pigs, residue 56 in the VP3 capsid protein was previously restored from Arg to wild-type His in the FMDV O1K infectious clone. The presence of Arg56 together with other positively charged amino acids in surrounding positions, all selected after passage on cell culture, has been associated with a high level of attenuation of type O isolates in bovines (49). The O1K-ΔSL1 mutant bearing a His at position 56 of VP3 lost the growth capacity of its VP3-R56 small-plaque-phenotype parental virus in cell culture. As was the case for their VP3-R56 counterparts, O1K-FL and -ΔSL2 transcripts with VP3-H56 were innocuous for suckling mice.

Inoculation of one or two doses of 500 μg of O1K-ΔSL1(VP3-H56) RNA failed to induce any clinical sign of disease in pigs, and no infectious virus could be isolated in cell culture from serum samples. However, viral RNA could be faintly amplified from sera collected from each animal at late times p.i., indicating low levels of replication extended over time. FMDV RNA can be readily detected in nasal swabs both before and after development of clinical disease and even in subclinically infected animals (2). In contrast, viral RNA could not be amplified from nasal swabs taken from RNA-inoculated pigs, suggesting that replication-defective O1K-ΔSL1(VP3-H56) virus was unable to reach these epithelia. This is a relevant issue, since airborne excretion of virus from infected animals is an important route of disease transmission.

Neutralizing antibodies appear to be the major protective component in swine and ruminants against FMDV (40). However, protection in the absence of detectable neutralizing antibodies has been documented (17, 56). Neutralization tests revealed that even a single inoculation with nonpathogenic O1K-ΔSL1(VP3-H56) RNA induced significant levels of neutralizing antibodies whose titers were increased (with the exception of pig 3) by a second RNA booster dose. Interestingly, one of the animals with the highest neutralization titers had received a single RNA inoculation (pig 8). Induction of specific IgA responses was detected in serum from the animals showing a higher neutralizing response (pigs 4 and 8). Several studies associate the induction of specific IgA with protection and suggest that vaccines that induce local IgA responses may be more effective (18, 22, 26). Moreover, mutant transcripts were able to induce a specific T-cell response in four out of the eight animals inoculated. The viral stimulatory effect was specifically inhibited with monoclonal antibodies against swine MHC (SLA) class I or class II, respectively. Taken together, our results show that inoculation with O1K-ΔSL1(VP3-H56) transcripts is able to elicit a broad immune response involving humoral and both CD4+ and CD8+ cellular responses.

To address whether the contribution of input RNA translation, independent of replication, was relevant for the immune response induced in RNA-inoculated animals, control experiments with mice were carried out. Neutralizing antibodies against FMDV were detected in serum at day 15 p.i. in 44% (n = 16) of adult Swiss mice inoculated in the tibialis anterior muscle with 10 to 50 μg of O1K/C-S8 RNA, viremic at 48 h p.i., while no specific response to the virus could be detected in mice inoculated with 100 μg of nonreplicating O1K-Δ3′NCR (VP3-H56) transcripts (n = 6) (data not shown). This suggests that viral replication is required to some extent for effective immunization.

The finding that the O1K-ΔSL1(VP3-H56) mutant is attenuated for swine while preserving immunogenicity has relevant implications for vaccine development. Although the use of attenuated viruses involves the concern for the risk of reversion to pathogenic viruses, deletion mutations are more stable than point mutations and reversion of the attenuated phenotype is unlikely. Moreover, even though infectivity of O1K-FL(VP3-H56) parental RNA has not been assayed in swine and so the specific contribution of the SL1 deletion to attenuation of this RNA cannot be directly assessed without further studies, the effect observed on replication in cell culture, including that with a porcine cell line, might be operating in swine as well. The lack of infectivity observed for the O1K-FL(VP3-H56) transcripts in mice suggest a certain level of attenuation for the O1K backbone itself. Indeed, the association of several attenuation factors in the same construct may contribute to the safety of a putative candidate vaccine. Additionally, we have shown that the ΔSL1 mutation was maintained after at least five serial passages in BHK-21 and IBRS-2 cells and at day 10 p.i. in pigs. ΔSL1 viruses grown in porcine IBRS-2 cells or viral genomes amplified from pig serum samples showed wild-type sequence in 2C and 3C nonstructural proteins, unlike some ΔSL1 viruses passaged on BHK-21 cells, which carried substitutions in those proteins.

RNA-based vaccines emerge as good potential vaccine candidates for positive-stranded RNA viruses for which infectious cDNA clones are available. In vitro-synthesized RNA can be delivered into host animals as an attenuated live vaccine, mimicking natural infection without actually inducing disease. RNA replicative forms including double-stranded RNA also stimulate various components of the innate and specific immune response (34). An RNA vaccine against coxsackievirus B3 bearing point mutations at the cleavage site between the 2A and 2B proteins conferred substantial protection against virus challenge (30). Highly efficient self-replicating noninfectious RNA vaccine candidates against flavivirus have been generated (1, 33, 47). A recombinant dengue virus type 4 containing a 30-nucleotide deletion in the 3′ NCR was immunogenic in humans and has been proposed as a live attenuated vaccine candidate (10, 21). Infectious transcripts from a FL infectious clone of bovine viral diarrhea virus delivered by use of a gene gun have been shown to induce humoral immunity in cattle and sheep against the virus (60).

Current FMD vaccines consist of purified inactivated virus preparations. These vaccines have proven useful in preventing the disease but present important constraints, such as the risk of virus escape from production plants and the difficulty in distinguishing infected animals from uninfected vaccinates. New vaccine strategies aimed at overcoming these problems have been developed, including subunit vaccines consisting of VP1 protein or chemically synthesized peptides (57, 61), different DNA constructs expressing viral immunogens (6, 8, 15), and recombinant viruses (25, 35, 44, 54, 63). Live attenuated candidate vaccines for FMD lacking the leader L protease and mutations in the receptor binding sequence RGD have also been proposed (3, 16). To our knowledge, this is the first report of FMDV RNA-based immunization. The protective efficacy of O1K-ΔSL1(VP3-H56) RNA in swine will be the aim of future work, which will contribute to further evaluating the feasibility of RNA-based FMD vaccines.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants QLK2-CT2002-01719 and RTA03-201 to M.S., BIO2005-07592-C02-01 to F.S., CSD2006-0007, Ramón y Cajal program (to M.S.), and a fellowship from INIA (to M.R.P.).

We thank M. Navarro and M. González for excellent technical assistance and E. Martínez-Salas and M. Gutiérrez for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 11 February 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aberle, J. H., S. W. Aberle, R. M. Kofler, and C. W. Mandl. 2005. Humoral and cellular immune response to RNA immunization with flavivirus replicons derived from tick-borne encephalitis virus. J. Virol. 7915107-15113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexandersen, S., M. Quan, C. Murphy, J. Knight, and Z. Zhang. 2003. Studies of quantitative parameters of virus excretion and transmission in pigs and cattle experimentally infected with foot-and-mouth disease virus. J. Comp. Pathol. 129268-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Almeida, M. R., E. Rieder, J. Chinsangaram, G. Ward, C. Beard, M. J. Grubman, and P. W. Mason. 1998. Construction and evaluation of an attenuated vaccine for foot-and-mouth disease: difficulty adapting the leader proteinase-deleted strategy to the serotype O1 virus. Virus Res. 5549-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baranowski, E., N. Molina, J. I. Núñez, F. Sobrino, and M. Sáiz. 2003. Recovery of infectious foot-and-mouth disease virus from suckling mice after direct inoculation with in vitro-transcribed RNA. J. Virol. 7711290-11295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baranowski, E., N. Sevilla, N. Verdaguer, C. M. Ruiz-Jarabo, E. Beck, and E. Domingo. 1998. Multiple virulence determinants of foot-and-mouth disease virus in cell culture. J. Virol. 726362-6372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beard, C., G. Ward, E. Rieder, J. Chinsangaram, M. J. Grubman, and P. W. Mason. 1999. Development of DNA vaccines for foot-and-mouth disease, evaluation of vaccines encoding replicating and non-replicating nucleic acids in swine. J. Biotechnol. 73243-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belsham, G. J., and E. Martínez-Salas. 2004. Genome organisation, translation and replication of FMDV RNA, p. 19-52. In F. Sobrino and E. Domingo (ed.), Foot-and-mouth disease: current perspectives. Horizon Bioscience, Norfolk, United Kingdom.

- 8.Benvenisti, L., A. Rogel, L. Kuznetzova, S. Bujanover, Y. Becker, and Y. Stram. 2001. Gene gun-mediate DNA vaccination against foot-and-mouth disease virus. Vaccine 193885-3895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanco, E., L. J. Romero, M. El Harrach, and J. M. Sánchez-Vizcaíno. 2002. Serological evidence of FMD subclinical infection in sheep population during the 1999 epidemic in Morocco. Vet. Microbiol. 8513-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blaney, J. E., Jr., A. P. Durbin, B. R. Murphy, and S. S. Whitehead. 2006. Development of a live attenuated dengue virus vaccine using reverse genetics. Viral Immunol. 1910-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown, D. M., C. T. Cornell, G. P. Tran, J. H. Nguyen, and B. L. Semler. 2005. An authentic 3′ noncoding region is necessary for efficient poliovirus replication. J. Virol. 7911962-11973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bullido, R., N. Doménech, B. Alvarez, F. Alonso, M. Babín, A. Ezquerra, E. Ortuño, and J. Domínguez. 1997. Characterization of five monoclonal antibodies specific for swine class II major histocompatibility antigens and crossreactivity studies with leukocytes of domestic animals. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 21311-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bullido, R., A. Ezquerra, F. Alonso, M. Gómez del Moral, and J. Domínguez. 1996. Characterization of a new monoclonal antibody (4B7) specific for porcine MHC (SLA) class I antigens. Investig. Agrar. Prod. Sanid. Anim. 1129-37. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carrillo, C., E. R. Tulman, G. Delhon, Z. Lu, A. Carreno, A. Vagnozzi, G. F. Kutish, and D. L. Rock. 2005. Comparative genomics of foot-and-mouth disease virus. J. Virol. 796487-6504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cedillo-Barron, L., M. Foster-Cuevas, G. J. Belsham, F. Lefevre, and R. M. Parkhouse. 2001. Induction of a protective response in swine vaccinated with DNA encoding foot-and-mouth disease virus empty capsid proteins and the 3D RNA polymerase. J. Gen. Virol. 821713-1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chinsangaram, J., P. W. Mason, and M. J. Grubman. 1998. Protection of swine by live and inactivated vaccines prepared from a leader proteinase-deficient serotype A12 foot-and-mouth disease virus. Vaccine 161516-1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collen, T. 1994. Foot-and-mouth disease (aphtovirus): viral T cell epitopes. In B. M. L. Goddeevis and I. Morrison (ed.), Cell mediated immunity in ruminants. CRC Press Inc., Boca Raton, FL.

- 18.Cubillos, C., B. G. de la Torre, A. Jakab, G. Clementi, E. Borras, J. Barcena, D. Andreu, F. Sobrino, and E. Blanco. 2008. Enhanced mucosal immunoglobulin A response and solid protection against foot-and-mouth disease virus challenge induced by a novel dendrimeric peptide. J. Virol. 827223-7230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dobrikova, E., P. Florez, S. Bradrick, and M. Gromeier. 2003. Activity of a type 1 picornavirus internal ribosomal entry site is determined by sequences within the 3′ nontranslated region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10015125-15130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donaldson, A. 2004. Clinical signs of foot-and-mouth disease, p. 93-102. In F. Sobrino and E. Domingo (ed.), Foot-and-mouth disease: current perspectives. Horizon Bioscience, Norfolk, United Kingdom.

- 21.Durbin, A. P., R. A. Karron, W. Sun, D. W. Vaughn, M. J. Reynolds, J. R. Perreault, B. Thumar, R. Men, C. J. Lai, W. R. Elkins, R. M. Chanock, B. R. Murphy, and S. S. Whitehead. 2001. Attenuation and immunogenicity in humans of a live dengue virus type-4 vaccine candidate with a 30 nucleotide deletion in its 3′-untranslated region. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 65405-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eblé, P. L., A. Bouma, K. Weerdmeester, J. A. Stegeman, and A. Dekker. 2007. Serological and mucosal immune responses after vaccination and infection with FMDV in pigs. Vaccine 251043-1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Escarmís, C., M. Toja, M. Medina, and E. Domingo. 1992. Modifications of the 5′ untranslated region of foot-and-mouth disease virus after prolonged persistence in cell culture. Virus Res. 26113-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferris, N. P., D. P. King, S. M. Reid, G. H. Hutchings, A. E. Shaw, D. J. Paton, N. Goris, B. Haas, B. Hoffmann, E. Brocchi, M. Bugnetti, A. Dekker, and K. De Clercq. 2006. Foot-and-mouth disease virus: a first inter-laboratory comparison trial to evaluate virus isolation and RT-PCR detection methods. Vet. Microbiol. 117130-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fowler, V. L., D. J. Paton, E. Rieder, and P. V. Barnett. 2008. Chimeric foot-and-mouth disease viruses: evaluation of their efficacy as potential marker vaccines in cattle. Vaccine 261982-1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Francis, M. J., and L. Black. 1983. Antibody response in pig nasal fluid and serum following foot-and-mouth disease infection or vaccination. J. Hyg. (London) 91329-334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ganges, L., M. Barrera, J. I. Núñez, I. Blanco, M. T. Frías, F. Rodríguez, and F. Sobrino. 2005. A DNA vaccine expressing the E2 protein of classical swine fever virus elicits T cell responses that can prime for rapid antibody production and confer total protection upon viral challenge. Vaccine 233741-3752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.García-Briones, M. M., E. Blanco, C. Chiva, D. Andreu, V. Ley, and F. Sobrino. 2004. Immunogenicity and T cell recognition in swine of foot-and-mouth disease virus polymerase 3D. Virology 322264-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herrera, M., A. Grande-Pérez, C. Perales, and E. Domingo. 2008. Persistence of foot-and-mouth disease virus in cell culture revisited: implications for contingency in evolution. J. Gen. Virol. 89232-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hunziker, I. P., S. Harkins, R. Feuer, C. T. Cornell, and J. L. Whitton. 2004. Generation and analysis of an RNA vaccine that protects against coxsackievirus B3 challenge. Virology 330196-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jensen, M. J., and D. M. Moore. 1993. Phenotypic and functional characterization of mouse attenuated and virulent variants of foot-and-mouth disease virus type O1 Campos. Virology 193604-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kitching, R. P. 2005. Global epidemiology and prospects for control of foot-and-mouth disease. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 288133-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kofler, R. M., J. H. Aberle, S. W. Aberle, S. L. Allison, F. X. Heinz, and C. W. Mandl. 2004. Mimicking live flavivirus immunization with a noninfectious RNA vaccine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1011951-1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leitner, W. W., L. N. Hwang, M. J. deVeer, A. Zhou, R. H. Silverman, B. R. Williams, T. W. Dubensky, H. Ying, and N. P. Restifo. 2003. Alphavirus-based DNA vaccine breaks immunological tolerance by activating innate antiviral pathways. Nat. Med. 933-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewis, S. A., D. O. Morgan, and M. J. Grubman. 1991. Expression, processing, and assembly of foot-and-mouth disease virus capsid structures in heterologous systems: induction of a neutralizing antibody response in guinea pigs. J. Virol. 656572-6580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.López de Quinto, S., M. Sáiz, D. de la Morena, F. Sobrino, and E. Martínez-Salas. 2002. IRES-driven translation is stimulated separately by the FMDV 3′-NCR and poly(A) sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 304398-4405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martínez-Salas, E., and O. Fernández-Miragall. 2004. Picornavirus IRES: structure function relationship. Curr. Pharm. Des. 103757-3767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mason, P. W., S. V. Bezborodova, and T. M. Henry. 2002. Identification and characterization of a cis-acting replication element (cre) adjacent to the internal ribosome entry site of foot-and-mouth disease virus. J. Virol. 769686-9694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mateu, M. G., E. Rocha, O. Vicente, F. Vayreda, C. Navalpotro, D. Andreu, E. Pedroso, E. Giralt, L. Enjuanes, and E. Domingo. 1987. Reactivity with monoclonal antibodies of viruses from an episode of foot-and-mouth disease. Virus Res. 8261-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCullough, K. C., and F. Sobrino. 2004. Immunology of foot-and-mouth disease, p. 173-222. In F. Sobrino and E. Domingo (ed.), Foot-and-mouth disease: current perspectives. Horizon Bioscience, Norfolk, United Kingdom.

- 41.McKenna, T. S., J. Lubroth, E. Rieder, B. Baxt, and P. W. Mason. 1995. Receptor binding site-deleted foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) virus protects cattle from FMD. J. Virol. 695787-5790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Melchers, W. J., J. G. Hoenderop, H. J. Bruins Slot, C. W. Pleij, E. V. Pilipenko, V. I. Agol, and J. M. Galama. 1997. Kissing of the two predominant hairpin loops in the coxsackie B virus 3′ untranslated region is the essential structural feature of the origin of replication required for negative-strand RNA synthesis. J. Virol. 71686-696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Merkle, I., M. J. van Ooij, F. J. van Kuppeveld, D. H. Glaudemans, J. M. Galama, A. Henke, R. Zell, and W. J. Melchers. 2002. Biological significance of a human enterovirus B-specific RNA element in the 3′ nontranslated region. J. Virol. 769900-9909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pacheco, J. M., M. C. Brum, M. P. Moraes, W. T. Golde, and M. J. Grubman. 2005. Rapid protection of cattle from direct challenge with foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) by a single inoculation with an adenovirus-vectored FMDV subunit vaccine. Virology 337205-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pilipenko, E. V., S. V. Maslova, A. N. Sinyakov, and V. I. Agol. 1992. Towards identification of cis-acting elements involved in the replication of enterovirus and rhinovirus RNAs: a proposal for the existence of tRNA-like terminal structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 201739-1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pilipenko, E. V., K. V. Poperechny, S. V. Maslova, W. J. Melchers, H. J. Slot, and V. I. Agol. 1996. Cis-element, oriR, involved in the initiation of (−) strand poliovirus RNA: a quasi-globular multi-domain RNA structure maintained by tertiary (′kissing') interactions. EMBO J. 155428-5436. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pugachev, K. V., F. Guirakhoo, D. W. Trent, and T. P. Monath. 2003. Traditional and novel approaches to flavivirus vaccines. Int. J. Parasitol. 33567-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rodríguez Pulido, M., P. Serrano, M. Sáiz, and E. Martínez-Salas. 2007. Foot-and-mouth disease virus infection induces proteolytic cleavage of PTB, eIF3a,b, and PABP RNA-binding proteins. Virology 364466-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sa-Carvalho, D., E. Rieder, B. Baxt, R. Rodarte, A. Tanuri, and P. W. Mason. 1997. Tissue culture adaptation of foot-and-mouth disease virus selects viruses that bind to heparin and are attenuated in cattle. J. Virol. 715115-5123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sáiz, J. C., A. Rodríguez, M. González, F. Alonso, and F. Sobrino. 1992. Heterotypic lymphoproliferative response in pigs vaccinated with foot-and-mouth disease virus. Involvement of isolated capsid proteins. J. Gen. Virol. 732601-2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sáiz, M., D. B. De La Morena, E. Blanco, J. I. Núñez, R. Fernández, and J. M. Sánchez-Vizcaíno. 2003. Detection of foot-and-mouth disease virus from culture and clinical samples by reverse transcription-PCR coupled to restriction enzyme and sequence analysis. Vet. Res. 34105-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sáiz, M., S. Gómez, E. Martínez-Salas, and F. Sobrino. 2001. Deletion or substitution of the aphthovirus 3′ NCR abrogates infectivity and virus replication. J. Gen. Virol. 8293-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sáiz, M., J. I. Núñez, M. A. Jiménez-Clavero, E. Baranowski, and F. Sobrino. 2002. Foot-and-mouth disease virus: biology and prospects for disease control. Microbes Infect. 41183-1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sanz-Parra, A., M. A. Jiménez-Clavero, M. M. García-Briones, E. Blanco, F. Sobrino, and V. Ley. 1999. Recombinant viruses expressing the foot-and-mouth disease virus capsid precursor polypeptide (P1) induce cellular but not humoral antiviral immunity and partial protection in pigs. Virology 259129-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Serrano, P., M. Rodríguez Pulido, M. Sáiz, and E. Martínez-Salas. 2006. The 3′ end of the foot-and-mouth disease virus genome establishes two distinct long-range RNA-RNA interactions with the 5′ end region. J. Gen. Virol. 873013-3022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sobrino, F., M. Sáiz, M. A. Jiménez-Clavero, J. I. Núñez, M. F. Rosas, E. Baranowski, and V. Ley. 2001. Foot-and-mouth disease virus: a long known virus, but a current threat. Vet. Res. 321-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Taboga, O., C. Tami, E. Carrillo, J. I. Núñez, A. Rodríguez, J. C. Sáiz, E. Blanco, M. L. Valero, X. Roig, J. A. Camarero, D. Andreu, M. G. Mateu, E. Giralt, E. Domingo, F. Sobrino, and E. L. Palma. 1997. A large-scale evaluation of peptide vaccines against foot-and-mouth disease: lack of solid protection in cattle and isolation of escape mutants. J. Virol. 712606-2614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Todd, S., J. S. Towner, D. M. Brown, and B. L. Semler. 1997. Replication-competent picornaviruses with complete genomic RNA 3′ noncoding region deletions. J. Virol. 718868-8874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Ooij, M. J., C. Polacek, D. H. Glaudemans, J. Kuijpers, F. J. van Kuppeveld, R. Andino, V. I. Agol, and W. J. Melchers. 2006. Polyadenylation of genomic RNA and initiation of antigenomic RNA in a positive-strand RNA virus are controlled by the same cis-element. Nucleic Acids Res. 342953-2965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vassilev, V. B., L. H. Gil, and R. O. Donis. 2001. Microparticle-mediated RNA immunization against bovine viral diarrhea virus. Vaccine 192012-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang, C. Y., T. Y. Chang, A. M. Walfield, J. Ye, M. Shen, S. P. Chen, M. C. Li, Y. L. Lin, M. H. Jong, P. C. Yang, N. Chyr, E. Kramer, and F. Brown. 2002. Effective synthetic peptide vaccine for foot-and-mouth disease in swine. Vaccine 202603-2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Witwer, C., S. Rauscher, I. L. Hofacker, and P. F. Stadler. 2001. Conserved RNA secondary structures in Picornaviridae genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 295079-5089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zheng, M., N. Jin, H. Zhang, M. Jin, H. Lu, M. Ma, C. Li, G. Yin, R. Wang, and Q. Liu. 2006. Construction and immunogenicity of a recombinant fowlpox virus containing the capsid and 3C protease coding regions of foot-and-mouth disease virus. J. Virol. Methods 136230-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zoll, J., H. A. Heus, F. J. van Kuppeveld, and W. J. Melchers. 2009. The structure-function relationship of the enterovirus 3′-UTR. Virus Res. 139209-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]