Abstract

Background: The purpose of the present study was to determine if patient age, lesion size, lesion location, presenting knee symptoms, and sex predict the healing status after six months of a standard protocol of nonoperative treatment for stable juvenile osteochondritis dissecans of the knee.

Methods: Forty-two skeletally immature patients (forty-seven knees) who presented with a stable osteochondritis dissecans lesion were included in the present study. All patients were managed with temporary immobilization followed by knee bracing and activity restriction. The primary outcome measure of progressive lesion reossification was determined from serial radiographs every six weeks, for up to six months of nonoperative treatment. A multivariable logistic regression model was used to determine potential predictors of healing status from the listed independent variables.

Results: After six months of nonoperative treatment, sixteen (34%) of forty-seven stable lesions had failed to progress toward healing. The mean surface area (and standard deviation) of the lesions that showed progression toward healing (208.7 ± 135.4 mm2) was significantly smaller than that of the lesions that failed to show progression toward healing (288.0 ± 102.6 mm2) (p = 0.05). A logistic regression model that included patient age, normalized lesion size (relative to the femoral condyle), and presenting symptoms (giving-way, swelling, locking, or clicking) was predictive of healing status. Age was not a significant contributor to the predictive model (p = 0.25).

Conclusions: In two-thirds of immature patients, six months of nonoperative treatment that includes activity modification and immobilization results in progressive healing of stable osteochondritis dissecans lesions. Lesions with an increased size and associated swelling and/or mechanical symptoms at presentation are less likely to heal.

Level of Evidence: Prognostic Level II. See Instructions to Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Juvenile osteochondritis dissecans of the knee is an acquired condition in children with open growth plates. The condition affects the subchondral bone and the articular cartilage and can lead to detachment of a bone fragment with its overlying articular cartilage. Ultimately, early-onset osteoarthritis can develop in patients with juvenile osteochondritis dissecans and adults with osteochondral lesions1-10.

Although osteochondritis dissecans in the adult usually requires operative treatment to promote healing, it has been reported that many juvenile osteochondritis dissecans lesions eventually heal after treatment with protocols that include activity restriction or immobilization8,11-22. One study that advocated only activity restriction until the patient was pain-free demonstrated total radiographic healing of thirty of thirty-one lesions9. Linden20 noted excellent results regardless of treatment type, whereas Hughston et al.18 recommended normal activity and strengthening rather than immobilization for the treatment of juvenile osteochondritis dissecans. Other reports that have focused on juvenile osteochondritis dissecans have demonstrated a successful healing rate of only 50% in association with six to eighteen months of nonoperative treatment11,23-25. Unfortunately, most previous studies have included a mixed group of lesions, with both stable and unstable articular cartilage defects. Because the chance for spontaneous healing of juvenile osteochondritis dissecans lesions that present with a disruption of the articular cartilage surface is low and the risk of further damage is high, most surgeons have recommended surgical stabilization of all unstable juvenile osteochondritis dissecans lesions at the time of presentation6. The optimal treatment for a stable juvenile osteochondritis dissecans lesion remains controversial because the condition is rare, the relative success of various treatments is unknown, the condition progresses or heals slowly, and there are no uniform criteria to determine success. In addition, clinical symptoms often resolve long before there are radiographic or magnetic resonance imaging signs of resolution, which leads to poor treatment compliance and loss to follow-up.

Because it is difficult to accurately predict which stable juvenile osteochondritis dissecans lesions will heal, the patient and family (at the advice of the treating physician) may wait to see if six months of nonoperative treatment with casting, bracing, and/or sports restriction will allow the lesions to heal. Unfortunately, failure to heal occurs in the cases of as many as 50% of patients, who then require surgery after the six-month waiting-out period11,23-25. It would be beneficial to determine an objective probability at the time of diagnosis as to which patients with juvenile osteochondritis dissecans will respond to nonoperative treatment and which patients will fail to respond to such treatment. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to assess whether, after six months of treatment, the healing response of a stable juvenile osteochondritis dissecans lesion can be predicted accurately at the time of diagnosis by means of a statistical model based on a combination of potential predictive measures, including patient age, normalized lesion size, lesion location, presenting symptoms, and sex.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

One hundred and eleven knees with a stable osteochondritis dissecans lesion of the distal femoral condyle were identified on the basis of ICD-9 (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision) diagnostic codes and a keyword (“osteochondritis dissecans”) search of radiology reports performed at a single institution between 1998 and 2005. Of these 111 knees, forty-seven were in patients who met the inclusion criteria of a stable lesion (as described below), open growth plates, no coexisting medical condition, complete medical records, and completion of treatment. From the identified sample population, sixty-four knees were excluded from the analysis because of an unstable lesion (six knees), closed growth plates (five), a coexisting medical condition (twenty-three), incomplete medical records (sixteen), or either ongoing treatment or an unfinished course of treatment (fourteen). The forty-two patients (forty-seven knees) who were included in the present study ranged in age from eight to fourteen years.

Conventional knee radiographs were made at the time of diagnosis and included anteroposterior, lateral, notch, and sunrise views. Magnetic resonance imaging of the knee was performed with use of a dedicated extremity coil in a 1.5 or 3.0-T scanner with 3 to 4-mm-thick proton-density and T1-weighted sequences in the axial, sagittal, and coronal planes. A stable juvenile osteochondritis dissecans lesion was defined as one showing no breach in the articular cartilage or the subchondral bone-lesion interface. We required that the magnetic resonance imaging scan show some high T1 signal (edema) in the epiphyseal bone adjacent to the osteochondritis dissecans lesion in order to exclude children with a normal ossification variant or irregular ossification26-30.

Treatment

Treatment started with six weeks of weight-bearing immobilization in a cylinder or long-leg cast. If radiographs that were made after six weeks of immobilization showed no reossification of the lesion, the patient continued to wear the cast for four to six additional weeks after three to seven days out of the cast to regain full knee motion. After casting, the patient was managed with a weight-bearing osteoarthritis brace (CounterForce Brace; Breg, Vista, California) that was adjusted to unload the involved compartment; a valgus mold was used for medial compartment lesions, and a varus mold was used for lateral compartment lesions. Running, jumping, sports, and gym class activity were initially restricted during bracing. On subsequent visits, spaced six to eight weeks apart, the patient was slowly advanced back to full activity while wearing the brace if the lesion showed progression toward healing. After total reossification of the lesion, the patient was allowed unrestricted activity without bracing.

Data Collection

The symptoms or complaints at the time of presentation (such as swelling, giving-way, locking, or clicking) were recorded from the patient history form. The patients were divided into two categories on the basis of the broad range of symptoms. Patients in Category I were asymptomatic or had pain only in the absence of other signs or symptoms. Patients in Category II had pain in combination with signs or symptoms such as giving-way, swelling, locking, or clicking. Demographic data (age and sex) were recorded at the time of diagnosis.

The location, surface area, and volume of the lesion were determined on the basis of the initial magnetic resonance imaging scan. The location of the lesion was identified as either the medial femoral condyle or the lateral femoral condyle on the coronal view. All lesions were in the weight-bearing portion of the condyle as determined on the sagittal view. The sagittal view was divided into three separate segments according to the classification system of Cahill and Berg31: A (anterior), B (middle), and C (posterior). The size of the lesion (length, width, and depth) was measured on sagittal and coronal proton-density and/or T1-weighted magnetic resonance images with use of electronic calipers (Figs. 1 and 2). On the basis of these measurements, the surface area of the lesion was estimated as the product of the sagittal length and coronal width of the lesion. Surface area (rectangular) measurements were also normalized by calculating them as a percentage of the maximal length and width of the femoral condyles as measured with electronic calipers on the sagittal and coronal magnetic resonance imaging scans. In the present report, the lesion size relative to the femoral condyle is indicated as “normalized lesion size.”

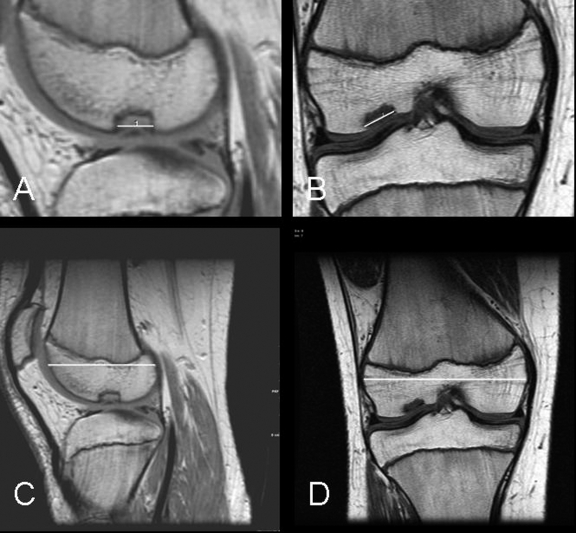

Fig. 1.

A through D: Magnetic resonance images showing a “small” juvenile osteochondritis dissecans lesion. After six months of nonoperative treatment, this lesion demonstrated progression toward healing (a “healed” outcome). A and C: Sagittal proton-density images showing the length measurement of the lesion (A) and the length measurement of the condyle (C). B and D: Coronal T1-weighted images showing the width measurement of the lesion (B) and the width measurement of the condyle (D).

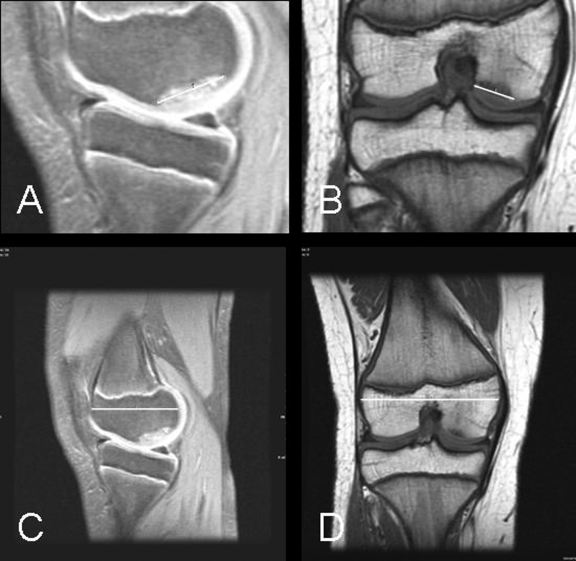

Fig. 2.

A through D: Magnetic resonance images showing a “large” juvenile osteochondritis dissecans lesion. After six months of nonoperative treatment, this lesion showed no signs of healing (a “failed” outcome). A and C: Sagittal proton-density images with fat saturation showing the length measurement of the lesion (A) and the length measurement of the condyle (C). B and D: Coronal T1-weighted images showing the width measurement of the lesion (B) and the width measurement of the condyle (D).

Outcome Measure

After six months of nonoperative treatment, patient outcomes were categorized as either Outcome 1 (progressing toward healing) or Outcome 2 (no signs of healing). Patients with Outcome 1 had radiographic evidence of reossification of the lesion after six months of nonoperative treatment, and patients with Outcome 2 had lesion destabilization or showed no evidence of reossification. One orthopaedic surgeon (E.J.W.) who was blinded to the magnetic resonance imaging and symptomatic data obtained at the time of the initial visit performed the evaluation of the lesion outcome.

Statistical Methods

For descriptions of the study sample, noncategorical continuous variables (surface area, lesion length, lesion width, lesion depth, femoral condyle length, femoral condyle width, length percentage, and width percentage) were presented as means, standard deviations, and ranges, whereas categorical variables (side, sagittal and coronal location, and symptoms) were presented as frequencies and percentages.

Multivariable logistic regression models were considered and presented to examine the predictive effects for the independent variables. To reduce the risk of having unreliable and over-fitted statistical models, the number of predictor variables for the analyses was limited to as many as four independent variables. Two models were developed. The primary model included the predictors of age, symptom category, and scaled surface area. To produce a model that would be “clinician-friendly,” a secondary model was developed and included the parameters of age, symptom category, normalized lesion length, and normalized lesion width. As normalized length and width were moderately correlated (Spearman rank correlation coefficient [r] = 0.47; p = 0.001), we tested the contribution of length and width together with a multiple-degrees-of-freedom test to avoid problems with multicollinearity.

Each model's predictive accuracy was quantified with the use of the C statistic, which is equivalent to the area under its receiver operating characteristic curve. A perfect model would have a C statistic of 1.0, and a value of ≥0.80 has utility in predicting the outcomes of individual patients. A nomogram was produced from the study sample to allow predictions to be made in individual patients32,33.

Results

After six months of nonoperative management, sixteen (34%) of the forty-seven lesions had failed to progress toward healing. Of the thirty-one lesions that were progressing toward healing, seven had completely reossified at the time of the six-month evaluation. Table I presents the description of the study sample (forty-two patients and forty-seven knees). The mean surface area (and standard deviation) of the lesions that demonstrated healing or progression toward healing was 208.7 ± 135.4 mm2, and the mean surface area of the lesions that did not demonstrate progression toward healing was 288.0 ± 102.6 mm2 (p = 0.05). Forty-one lesions involved the medial femoral condyle, and six involved the lateral femoral condyle. All six lateral condylar lesions demonstrated healing or progression toward healing. The sixteen failures occurred among the group of forty-one medial condylar lesions.

TABLE I.

Data on the Study Sample*

| Characteristics | Descriptive Statistics |

|---|---|

| Side (no. of knees) | |

| Left | 25 (53%) |

| Right | 22 (47%) |

| Location (no. of knees) | |

| Sagittal† | |

| B | 31 (66%) |

| B/C | 16 (34%) |

| Coronal | |

| Lateral femoral condyle | 6 (13%) |

| Medial femoral condyle | 41 (87%) |

| Symptoms‡(no. of knees) | |

| Category I | 32 (68%) |

| Category II | 15 (32%) |

| Surface area§ (mm2) | 236 ± 130 (20 to 575) |

| Scaled surface area§(%) | 6.7 ± 3.4 (0.9 to 14.3) |

| Length§(mm) | 18.4 ± 6.6 (4.0 to 34.4) |

| Width§(mm) | 12.2 ± 4.4 (3.9 to 28.1) |

| Length§(%) | 38.1 ± 14.0 (10.3 to 76.2) |

| Width§(%) | 16.8 ± 5.6 (5.4 to 36.4) |

| Depth§(mm) | 4.1 ± 1.6 (1.5 to 7.1) |

| Condyle length§(mm) | 48.6 ± 5.4 (39.0 to 61.3) |

| Condyle width§(mm) | 72.3 ± 7.2 (56.0 to 88.3) |

The study sample included forty-two patients (forty-seven knees).

The sagittal view was divided into three separate segments based on the classification of Cahill and Berg31: A (anterior), B (middle), and C (posterior).

Category I indicated either no symptoms (incidental finding on radiographs) or just pain. Category II indicated “mechanical” symptoms, including giving-way, swelling, locking, or clicking.

The values are given as the mean and the standard deviation, with the range in parentheses.

Table II provides the descriptive statistics on the study characteristics of knees with and without progression toward healing. Table III presents both multivariable logistic regression models for predicting healing at six months. The primary logistic regression model included age, symptoms, and scaled surface area. This model was predictive of healing status, with a C statistic of 0.85 and a validated C statistic of 0.81. For every 5% decrease in normalized lesion size (the calculated surface area of the lesion relative to the calculated surface area of the femoral condyle), the odds of progression toward healing increased 5.36-fold (95% confidence interval, 1.56 to 18.41; p < 0.01). Isolated pain (Category-I symptoms) increased the odds of progression toward healing 6.68-fold (95% confidence interval, 1.42 to 31.50; p = 0.016). Age (mean, 11.4 ± 1.4 years for patients who had progression toward healing compared with 11.9 ± 1.3 for those who did not) was not a significant contributor to the predictive model (p = 0.25). While age did not provide a significant contribution to the prediction of outcome in the current logistic regression analysis, it was not removed from the model because previous literature has indicated that age is clinically relevant to the healing-status outcome of juvenile osteochondritis dissecans lesions. The secondary logistic regression model, which included age, symptoms, and normalized lesion size (both length and width), was predictive of healing status, with a C statistic of 0.85 and validated C statistic of 0.78. Isolated pain (Category-I symptoms) increased the odds of progression toward healing 6.89-fold (95% confidence interval, 1.46 to 32.63; p = 0.015). The combined effect of normalized length and width was significant (p = 0.01). Age again was not a significant contributor to this model (p = 0.27). Figure 3 presents a nomogram developed from the regression analysis that can be used to predict outcome on the basis of normalized width, normalized length, and symptoms. A sensitivity analysis to assess the independence assumption on a reduced data set closely agreed with the results of the full data set (all knees).

TABLE II.

Relationship of Characteristics to Healing

| Outcome

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Failure (16 Knees) | Healing (31 Knees) | P Value* |

| Sex (no. of knees) | 0.74 | ||

| Female (n = 15) | 6 (40%) | 9 (60%) | |

| Male (n = 32) | 10 (31%) | 22 (69%) | |

| Side (no. of knees) | 1.00 | ||

| Left (n = 25) | 9 (36%) | 16 (64%) | |

| Right (n = 22) | 7 (32%) | 15 (68%) | |

| Location (no. of knees) | |||

| Sagittal view† | 0.77 | ||

| B (n = 31) | 11 (35%) | 20 (65%) | |

| B/C (n = 16) | 5 (31%) | 11 (69%) | |

| Coronal view | 0.08 | ||

| Lateral femoral condyle (n = 6) | 0 (0%) | 6 (100%) | |

| Medial femoral condyle (n = 41) | 16 (39%) | 25 (61%) | |

| Symptoms‡(no. of knees) | 0.019 | ||

| Category I (n = 32) | 7 (22%) | 25 (78%) | |

| Category II (n = 15) | 9 (60%) | 6 (40%) | |

| Surface area§(mm2) | 288 ± 103 | 208.7 ± 135 | 0.05 |

| Scaled surface area§(%) | 8.7 ± 3.1 | 5.6 ± 3.1 | 0.002 |

| Length§(mm) | 20.7 ± 5.9 | 17.2 ± 6.6 | 0.08 |

| Width§(mm) | 14.0 ± 4.1 | 11.3 ± 4.3 | 0.04 |

| Length§(%) | 44.3 ± 13.8 | 35.0 ± 13.2 | 0.03 |

| Width§(%) | 19.7 ± 5.4 | 15.3 ± 5.1 | 0.01 |

| Depth§(mm) | 3.9 ± 1.4 | 4.3 ± 1.7 | 0.46 |

| Condyle length sagittal view§(mm) | 47.3 ± 3.3 | 49.2 ± 6.2 | 0.26 |

| Condyle width coronal view§(mm) | 71.3 ± 5.0 | 72.8 ± 8.1 | 0.50 |

Fisher exact test for categorical characteristics and t test for continuous characteristics.

The sagittal view was divided into three separate segments based on the classification of Cahill and Berg31: A (anterior), B (middle), and C (posterior).

Category I indicated either no symptoms (incidental finding on radiographs) or just pain. Category II indicated “mechanical” symptoms, including giving-way, swelling, locking, or clicking.

The values are given as the mean and the standard deviation.

TABLE III.

Multivariable Logistic Regression Models for Predicting Healing at Six Months*

| Primary Model

|

Secondary Model

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Unit of Comparison | Odds Ratio† | P Value‡ | Odds Ratio† | P Value‡ |

| Age§ | 2-year decrease | 1.95 (0.62 to 6.09) | 0.25 | 1.90 (0.60 to 6.04) | 0.27 |

| Symptom category | Isolated or mechanical | 6.68 (1.42 to 31.50) | 0.016 | 6.89 (1.46 to 32.63) | 0.015 |

| Length and width | — | — | 0.01 | ||

| Length# | 15% decrease | 2.00 (0.83 to 4.78) | |||

| Width** | 5% decrease | 2.21 (0.96 to 5.09) | |||

| Scaled surface area | 5% decrease | 5.36 (1.56 to 18.41) | <0.01 | — | — |

Based on forty-seven knees.

The 95% confidence interval is given in parentheses.

For each potential predictor variable, the p values indicate the significance of the association with the “healed” outcome status.

The unit of comparison is two years.

The unit of comparison is 15%.

The unit of comparison is 5%.

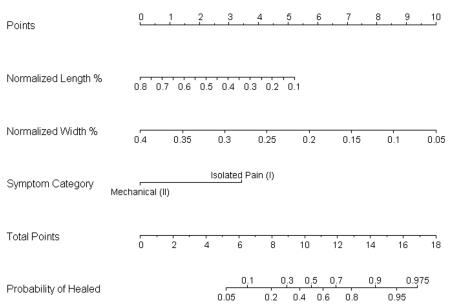

Fig. 3.

A nomogram developed from the regression analysis can be used to predict outcome on the basis of normalized width, normalized length, and symptoms. To use the nomogram, one should place a straight edge vertically so that it touches the designated variable on the axis for each predictor and then should record the value that each of the three predictors provides on the “points” axis at the top of the diagram. All of the recorded “points” are then summed, and this value is located on the “total points” line with a straight edge. A vertical line drawn down from the “total points” line to the “probability of healed” line will identify the probability that the patient will demonstrate healing or progression toward healing after six months of conservative treatment based on the utilized predictive variables.

Discussion

The principal finding of the present study was that the size of the lesion as determined on magnetic resonance images was the strongest prognostic variable, with the average size (length × width) being 209 mm2 in the group with healing as compared with 288 mm2 in the group without healing. Mesgarzadeh et al. reported that, in a combined group of juvenile and young adult patients with osteochondritis dissecans lesions who had a mean age of eighteen years, all lesions measuring ≤20 mm2 were stable and those measuring ≥80 mm2 were loose34. Cahill et al. found that a larger lesion size correlated with a higher failure rate in males but not in females11. They reported an average surface area of 309 mm2 for lesions that were treated effectively nonoperatively, compared with 436 mm2 for lesions that failed to heal. Pill et al. reported that nonoperative treatment failed most often in young patients with larger lesions (average size, 194 compared with 152 mm2), although significance was not reported23. Crawfurd et al. performed a review of twenty-eight young patients (mean age, twelve years; range, eight to twenty-two years) and determined that lesion size had no relationship with the healing rate35. We found that lesion size, particularly lesion size normalized to the size of the femoral condyle, was a strong determinant of outcome.

Despite aggressive nonoperative treatment that included an initial six to twelve weeks of weight-bearing cast immobilization followed by the use of a compartment-unloading brace and sports restriction, we found a 34% failure rate after six months of treatment. We defined failure as the absence of radiographic evidence of healing (reossification) of the lesion after six months of nonoperative treatment. To our knowledge, the present study is the first to focus exclusively on stable juvenile osteochondritis dissecans lesions in children as determined with magnetic resonance imaging. We chose six months as a cutoff for the trial of nonoperative treatment because it falls within the three to twelve-month range recommended by other authors3,36-43.

Given that we focused only on stable lesions in children, our rate of failure is high in comparison with those in several historical studies that included both stable and unstable juvenile osteochondritis dissecans lesions. Hughes et al. found that as long as the cartilage appeared to be intact on the initial magnetic resonance imaging scan, 95% of the patients with juvenile osteochondritis dissecans became asymptomatic with conservative treatment; however, that study did not assess radiographic healing44. Bellelli et al. found that all eight juvenile osteochondritis dissecans lesions in seven patients showed spontaneous healing on serial magnetic resonance imaging scans if they were initially stable and the maximum longitudinal diameter of the lesion was <20 mm45. On the other hand, Cahill et al. used strict criteria for success, requiring both scintigraphic and radiographic evidence of healing, and found a much higher failure rate (50%) in association with nonoperative treatment11.

Because we excluded all unstable lesions, nearly all of our patients would have had grade-I lesions on most magnetic resonance imaging grading scales14,22,43,46-48. The resulting floor effect, with almost all of the lesions in our study being grade-I stable lesions, did not allow us to perform a correlation of magnetic resonance imaging grade and healing similar to that reported in other studies14,23. However, we did not exclude lesions with a high-intensity-signal line between the lesion and the epiphyseal bone, which is one of the four signs of instability on magnetic resonance imaging scans as defined by De Smet et al.14. The authors of more recent studies have argued that this is not a sign of fluid or instability, but of healing granulation tissue17,22,45,49.

The present study showed a predominance of forty-one medial femoral condylar lesions as compared with six lateral condylar lesions, which is consistent with most previous reports on juvenile osteochondritis dissecans7,11,16,23,25. All six lateral lesions healed, whereas all sixteen failures occurred in the larger group of forty-one medial lesions (p = 0.08). We did not include location in our regression model because of the small number of lateral lesions. It is possible that this trend would become significant with a larger study. Other authors have reported an inconsistent association between location and prognosis in juvenile osteochondritis dissecans. Most authors have found that non-medial femoral condylar lesions heal best7,22,35, but Hefti et al. found a better prognosis in association with classic medial femoral condylar lesions as compared with lesions in other sites16, and two studies demonstrated no influence of coronal plane location on healing prognosis11,23.

Surprisingly, our results demonstrated no significant effect of age on prognosis for children with stable juvenile osteochondritis dissecans lesions. In our study, the mean age at the time of diagnosis was 11.4 years for the group of patients who had healing or progression toward healing and 11.9 years for those who did not. Some reports have demonstrated no significant effect of age on healing prognosis1,11,46, but most have demonstrated greater success in younger patients14,16,20,50.

Figure 3 presents a nomogram, developed from regression analysis of our data on lesion size and symptoms, that may provide an objective algorithmic tool to aid clinicians in determining the relative prognosis on the basis of lesion size and symptoms. Nomograms can be useful tools for the prediction of ordinal outcomes on the basis of clinical signs at the time of diagnosis51. Figure 4 presents an example of the nomogram-predicted outcome based on lesion size and symptoms in an actual patient.

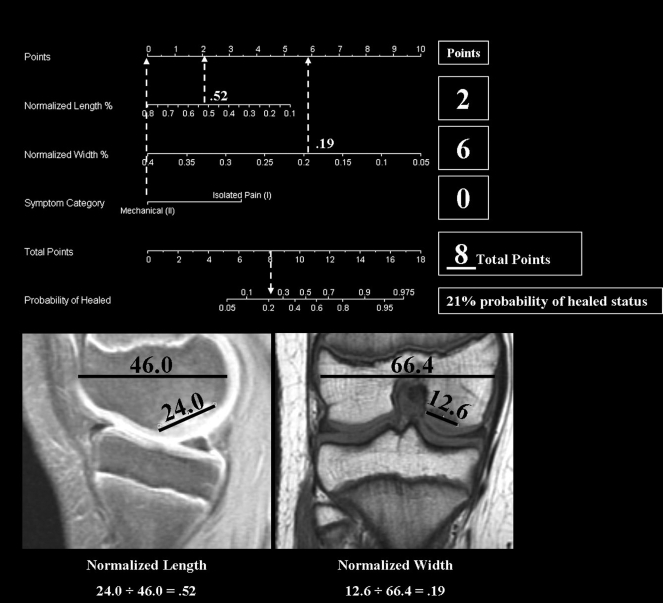

Fig. 4.

Example of a representative patient's calculated probability of achieving healed status with use of our nomogram, which is based on the normalized length of the lesion, the normalized width of the lesion, and reported symptoms. The patient did not achieve healed status after six weeks of nonoperative treatment.

A major limitation in a study of nonoperative treatment is patient compliance. We chose casting as the initial form of immobilization to enforce compliance with activity rest in this very active, athletic population. No patient removed his or her cast prematurely. Patients were monitored closely during treatment (every six to eight weeks), patients and parents were queried on brace and activity compliance at each visit, and the rationale for treatment was reinforced. Second, because we defined healing liberally as any progression toward reossification of the osteochondritis dissecans lesion, we may have overestimated the prevalence of healing. Third, we did not perform follow-up magnetic resonance imaging on all patients, and even those who showed good radiographic evidence of healing or progression toward healing still showed signal change on their follow-up magnetic resonance imaging scans. We plan to perform a long-term follow-up on this cohort of patients with magnetic resonance imaging, and it is likely that we will find a greater number of failures than is reflected by the 34% rate reported in this short-term study. With an increased number of failures, the statistical models will need to be updated (adjusted) to be valid and generalizable. Fourth, even when magnetic resonance imaging electronic calipers are used, there is some error in the measurement of lesion size because the margins of the lesion may be poorly defined. Our consistency of image quality may be superior to that in other studies because all magnetic resonance imaging scans were acquired at our institution at ≥1.5 T.

Another potential limitation of the present study is the interpretation and categorization of the “mechanical” symptom category. The subjective nature of patient complaints such as giving-way or locking may limit the accuracy of this variable's contribution to the model as indicated by the width of the 95% confidence interval (odds ratio, 6.68; 95% confidence interval, 1.42 to 31.50). Also, it should be noted that the nomogram that we have presented is a clinical predictive tool generated from our one set of data. Validation on other data sets is necessary to confirm its generalizability for other populations. Last, we acknowledge that there are also limitations and potential implications associated with the retrospective study design, including the lack of standardization of symptom descriptions as well as the reliability and accuracy of the study measures. Future prospective investigational study designs are warranted in this population to further validate these results and to confirm the usefulness of the nomogram.

In the present study of patients with stable juvenile osteochondritis dissecans lesions, only two-thirds of the lesions demonstrated healing with aggressive nonoperative treatment including cast immobilization, unloader bracing, and activity restriction. We recommend magnetic resonance imaging for the evaluation of patients with juvenile osteochondritis dissecans at the time of the initial presentation in order to evaluate the articular surface of the lesion. If the articular cartilage is intact, a six-month course of nonoperative treatment is indicated; however, patients and their families should be counseled with regard to the prognosis for healing. Importantly, our nomogram that incorporates the size of the lesion and symptoms at the time of presentation may aid in the prediction of the healing potential of an individual who has a stable juvenile osteochondritis dissecans lesion.

Disclosure: In support of their research for or preparation of this work, one or more of the authors received, in any one year, outside funding or grants in excess of $10,000 from the National Institutes of Health (Grant R01-AR049735-03). Neither they nor a member of their immediate families received payments or other benefits or a commitment or agreement to provide such benefits from a commercial entity. No commercial entity paid or directed, or agreed to pay or direct, any benefits to any research fund, foundation, division, center, clinical practice, or other charitable or nonprofit organization with which the authors, or a member of their immediate families, are affiliated or associated.

Investigation performed at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio

References

- 1.Aglietti P, Ciardullo A, Giron F, Ponteggia F. Results of arthroscopic excision of the fragment in the treatment of osteochondritis dissecans of the knee. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:741-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson AF, Pagnani MJ. Osteochondritis dissecans of the femoral condyles. Long-term results of excision of the fragment. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:830-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradley J, Dandy DJ. Results of drilling osteochondritis dissecans before skeletal maturity. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1989;71:642-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruns J, Rosenbach B. Osteochondrosis dissecans of the talus. Comparison of results of surgical treatment in adolescents and adults. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1992;112:23-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gudas R, Kunigiskis G, Kalesinskas RJ. [Long-term follow-up of osteochondritis dissecans]. Medicina (Kaunas). 2002;38:284-8. Lithuanian. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kocher MS, Tucker R, Ganley TJ, Flynn JM. Management of osteochondritis dissecans of the knee: current concepts review. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:1181-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linden B. The incidence of osteochondritis dissecans in the condyles of the femur. Acta Orthop Scand. 1976;47:664-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindholm TS, Osterman K. Treatment of juvenile osteochondritis dissecans in the knee. Acta Orthop Belg. 1979;45:633-40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sales de Gauzy J, Mansat C, Darodes PH, Cahuzac JP. Natural course of osteochondritis dissecans in children. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1999;8:26-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Twyman RS, Desai K, Aichroth PM. Osteochondritis dissecans of the knee. A long-term study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73:461-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cahill BR, Phillips MR, Navarro R. The results of conservative management of juvenile osteochondritis dissecans using joint scintigraphy. A prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 1989;17:601-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cahill BR. Osteochondritis dissecans of the knee: treatment of juvenile and adult forms. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1995;3:237-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiroff RT, Cooke CP 3rd. Osteochondritis dissecans: a histologic and microradiographic analysis of surgically excised lesions. J Trauma. 1975;15:689-96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Smet AA, Ilahi OA, Graf BK. Untreated osteochondritis dissecans of the femoral condyles: prediction of patient outcome using radiographic and MR findings. Skeletal Radiol. 1997;26:463-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glancy GL. Juvenile osteochondritis dissecans. Am J Knee Surg. 1999;12:120-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hefti F, Beguiristain J, Krauspe R, Moller-Madsen B, Riccio V, Tschauner C, Wetzel R, Zeller R. Osteochondritis dissecans: a multicenter study of the European Pediatric Orthopedic Society. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1999;8:231-45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hinshaw MH, Tuite MJ, De Smet AA. “Dem bones”: osteochondral injuries of the knee. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2000;8:335-48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hughston JC, Hergenroeder PT, Courtenay BG. Osteochondritis dissecans of the femoral condyles. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66:1340-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jurgensen I, Bachmann G, Schleicher I, Haas H. Arthroscopic versus conservative treatment of osteochondritis dissecans of the knee: value of magnetic resonance imaging in therapy planning and follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2002;18:378-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linden B. Osteochondritis dissecans of the femoral condyles: a long-term follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59:769-76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schenck RC Jr, Goodnight JM. Osteochondritis dissecans. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:439-56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshida S, Ikata T, Takai H, Kashiwaguchi S, Katoh S, Takeda Y. Osteochondritis dissecans of the femoral condyle in the growth stage. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;346:162-70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pill SG, Ganley TJ, Milam RA, Lou JE, Meyer JS, Flynn JM. Role of magnetic resonance imaging and clinical criteria in predicting successful nonoperative treatment of osteochondritis dissecans in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23:102-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wall EJ, Von Stein D. Juvenile osteochondritis dissecans. Orthop Clin North Am. 2003;34:341-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cepero S, Ullot R, Sastre S. Osteochondritis of the femoral condyles in children and adolescents: our experience over the last 28 years. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2005;14:24-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caffey J, Madell SH, Royer C, Morales P. Ossification of the distal femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1958;40:647-54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clanton TO, DeLee JC. Osteochondritis dissecans. History, pathophysiology and current treatment concepts. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;167:50-64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nawata K, Teshima R, Morio Y, Hagino H. Anomalies of ossification in the posterolateral femoral condyle: assessment by MRI. Pediatr Radiol. 1999;29:781-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ribbing S. [Multiple hereditary epiphyseal disorders and osteochondrosis dissecans]. Acta Radiol. 1951;36:397-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sontag LW, Pyle SI. Variations in the calcification pattern in epiphyses. Their nature and significance. Am J Roentgenol. 1941;45:50-4. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cahill BR, Berg BC. 99m-Technetium phosphate compound joint scintigraphy in the management of juvenile osteochondritis dissecans of the femoral condyles. Am J Sports Med. 1983;11:329-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harrell FE Jr. Regression modeling strategies. With applications to linear models, logistic regression, and survival analysis. New York: Springer; 2001.

- 33.Harrell FE. Design: S functions for biostatistical/epidemiologic modeling, testing, estimation, validation, graphics, and prediction. Programs available from http://lib.stat.cmu.edu/S/Harrell/help/Design/html/Overview.html. 2003.

- 34.Mesgarzadeh M, Sapega AA, Bonakdarpour A, Revesz G, Moyer RA, Maurer AH, Alburger PD. Osteochondritis dissecans: analysis of mechanical stability with radiography, scintigraphy, and MR imaging. Radiology. 1987;165:775-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crawfurd EJ, Emery RJ, Aichroth PM. Stable osteochondritis dissecans—does the lesion unite? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72:320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robertson W, Kelly BT, Green DW. Osteochondritis dissecans of the knee in children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2003;15:38-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Louisia S, Beaufils P, Katabi M, Robert H; French Society of Arthroscopy. Transchondral drilling for osteochondritis dissecans of the medial condyle of the knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2003;11:33-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kocher MS, Micheli LJ, Yaniv M, Zurakowski D, Ames A, Adrignolo AA. Functional and radiographic outcome of juvenile osteochondritis dissecans of the knee treated with transarticular arthroscopic drilling. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:562-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flynn JM, Kocher MS, Ganley TJ. Osteochondritis dissecans of the knee. J Pediatr Orthop. 2004;24:434-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aglietti P, Buzzi R, Bassi PB, Fioriti M. Arthroscopic drilling in juvenile osteochondritis dissecans of the medial femoral condyle. Arthroscopy. 1994;10:286-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garrett JC. Osteochondritis dissecans. Clin Sports Med. 1991;10:569-93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cahill B. Treatment of juvenile osteochondritis dissecans and osteochondritis dissecans of the knee. Clin Sports Med. 1985;4:367-84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bohndorf K. Osteochondritis (osteochondrosis) dissecans: a review and new MRI classification. Eur Radiol. 1998;8:103-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hughes JA, Cook JV, Churchill MA, Warren ME. Juvenile osteochondritis dissecans: a 5-year review of the natural history using clinical and MRI evaluation. Pediatr Radiol. 2003;33:410-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bellelli A, Avitto A, David V. [Spontaneous remission of osteochondritis dissecans in 8 pediatric patients undergoing conservative treatment]. Radiol Med (Torino). 2001;102:148-53. Italian. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kramer J, Stiglbauer R, Engel A, Prayer L, Imhof H. MR contrast arthrography (MRA) in osteochondrosis dissecans. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1992;16:254-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dipaola JD, Nelson DW, Colville MR. Characterizing osteochondral lesions by magnetic resonance imaging. Arthroscopy. 1991;7:101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nelson DW, DiPaola J, Colville M, Schmidgall J. Osteochondritis dissecans of the talus and knee: prospective comparison of MR and arthroscopic classifications. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1990;14:804-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O'Connor MA, Palaniappan M, Khan N, Bruce CE. Osteochondritis dissecans of the knee in children. A comparison of MRI and arthroscopic findings. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:258-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pappas AM. Osteochondrosis dissecans. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1981;158:59-69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harrell FE Jr, Margolis PA, Gove S, Mason KE, Mulholland EK, Lehmann D, Muhe L, Gatchalian S, Eichenwald HF. Development of a clinical prediction model for an ordinal outcome: the World Health Organization Multicentre Study of Clinical Signs and Etiological Agents of Pneumonia, Sepsis and Meningitis in Young Infants. WHO/ARI Young Infant Multicentre Study Group. Stat Med. 1998;17:909-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]