Abstract

Objective

To examine prevalence and frequency of oral medication nonadherence using a multimethod assessment approach consisting of objective, subjective, and biological data in adolescents with IBD.

Methods

Medication adherence was assessed via pill counts, patient/parent interview, and 6-thioguanine nucleotide (6-TGN)/6-methylmercaptopurine nucleotide (6-MMPN) metabolite bioassay in 42 adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. Pediatric gastroenterologists provided disease severity assessments.

Results

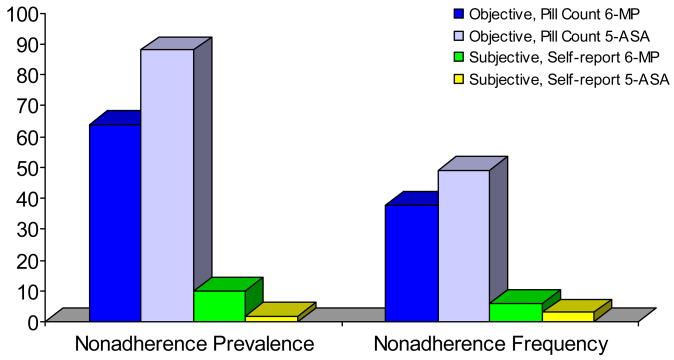

Objective nonadherence prevalence was 64% for 6-MP/azathioprine and 88% for 5-ASA medications, whereas subjective nonadherence prevalence was 10% for 6-MP/azathioprine and 2% for 5-ASA. Objective nonadherence frequency was 38% for 6-MP/azathioprine and 49% for 5-ASA medications, and subjective nonadherence frequency was 6% for 6-MP/azathioprine and 3% for 5-ASA. Bioassay data revealed that only 14% of patients had therapeutic 6-TGN levels.

Conclusions

Results indicate that objectively measured medication nonadherence prevalence is consistent with that observed in other pediatric chronic illness populations, and that objective nonadherence frequency is considerable, with 40% to 50% of doses missed by patients. Subjective assessments appeared to overestimate adherence. Bioassay adherence data, while compromised by pharmacokinetic variation, might be useful as a cursory screener for nonadherence with follow up objective assessment. Nonadherence in one medication might also indicate nonadherence in other medications. Clinical implications and future research directions are provided.

Keywords: Adherence, Compliance, Medication, Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) affects approximately 71 in 100,000 children and adolescents (43 per 100,000 with Crohn’s disease and 28 per 100,000 with ulcerative colitis) in the United States,1 with roughly one fourth of all patients diagnosed as children or adolescents (i.e., under 18 years of age). Treatment of IBD can involve several medications with varying regimens, dietary modification, and potentially surgery depending on symptoms, severity of illness, and response to treatment. Patients’ adherence to prescribed treatments has significant ramifications for each of these clinical decisions as well as patient morbidity and mortality and cost-effectiveness of care.2–6 The undesirable side effects of some medications (e.g., weight gain, cushingoid appearance, immune suppression) and the complex treatment regimens for IBD patients (e.g., varying dosing schedules and pill quantities for each medication) are likely to disrupt adherence and effective management of this condition.

Research on adherence in IBD is scant and primarily restricted to the adult population. Adult studies have revealed medication nonadherence prevalence rates ranging from 35% to 45%.7–9 However, these data are of limited utility when considering nonadherence in children and adolescents given the complex developmental challenges unique to childhood and adolescence, the maturation of cognitive and behavioral patterns (e.g., health beliefs) that affect self-management, and the sharing of treatment adherence responsibility between children/adolescents and their caregivers.10 Across pediatric chronic illness populations, the prevalence of nonadherence is approximately 50% in children5 and 65%–75% in adolescents.11 However, only a few studies have examined adherence rates in pediatric IBD, with results indicating nonadherence prevalence estimates ranging from 50% to 66%.12–14 Unfortunately, each of these studies utilized different unimodal assessment methods including an unstandardized self-report questionnaire, unstandardized patient/parent interview, and pharmacy record data. Thus, assessment methodology to date has varied with respect to objective versus subjective measurement, target behavior assessed (e.g., consumption of medication, refill of prescription), medication assessed, and method of assessment, resulting in differing nonadherence prevalence estimates and diminished generalizability and validity of data. Moreover, no study in pediatric IBD has examined nonadherence prevalence rates across various measures, and none have reported frequency of nonadherence (i.e., percent of prescribed doses not taken)

Several measures of adherence can potentially be used in pediatric IBD. Behavioral assessments provide a plethora of retrospective and prospective data regarding timing, frequency, and patterns of nonadherence. However, they are limited by potential response bias in self-report measures, mechanical malfunction in electronic monitors, and behavioral manipulation such as discarding pills to influence pill count data.5 Bioassays such as 6-thioguanine nucleotide (6-TGN) and 6-methylmercaptopurine nucleotide (6-MMPN) levels have been suggested as potentially useful adherence markers for 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP)/azathioprine.15–17 However, their utility is qualified by the fact that they have not been validated against traditional measures of adherence. Moreover, like other bioassays, they are subject to pharmacokinetic variation in absorption, metabolism, and excretion, as well as behavioral manipulation such as “white coat” adherence.5 Despite their limitations in quantifying adherence, bioassays provide key adherence data in that they can confirm ingestion. Although detectable yet non-therapeutic metabolite levels can suggest either nonadherence or pharmacokinetic influence or both, cases in which both 6-TGN and 6-MMPN levels are subtherapeutic/unquantifiable likely indicate nonadherence; however, this has yet to be demonstrated empirically. Thus, although there is no “gold standard” of adherence assessment, and limitations exist with any measure of adherence, both behavioral and biological measures offer unique data that could be used to better understand nonadherence. Determining the most advantageous approach to adherence assessment is critical to the clinical care of these patients, particularly in light of the relationship between nonadherence and increased disease severity that has been observed in adult IBD.18

Given the paucity of adherence data in pediatric IBD and lack of understanding of how different types of adherence assessments function in this population, the primary aim of this study was to examine objective versus subjective oral medication nonadherence prevalence and frequency in adolescents with IBD. This was conducted using a multimethod assessment battery consisting of objective (i.e., pill counts), subjective (i.e., semi-structured clinical interview), and biological (i.e., 6-TGN/6-MMPN assays) measures. Because immunomodulators and anti-inflammatory agents are commonly prescribed medications in pediatric IBD, 6-MP/azathioprine and 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) were targeted for adherence assessment. These medications are ideal for assessment given the considerably different dosing schedules and quantities of pills per dose. It was hypothesized that nonadherence prevalence in IBD would be comparable to other adolescent chronic illness populations (i.e., 65%–75%)11, and that subjective assessment of nonadherence would yield lower nonadherence (i.e., higher adherence) prevalence and frequency estimates than objective assessment. Due to the lack of extant data regarding the utility of 6-TGN/6-MMPN assays for adherence assessment, we also conducted exploratory analyses to examine prevalence and frequency of nonadherence in the subsample of patients who demonstrated subtherapeutic/unquantifiable 6-TGN/6-MMPN levels.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Inclusion criteria were: 1) diagnosis of Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, 2) 13–17 years of age, 3) prescribed 6-MP/azathioprine and 5-ASA, 4) 6-TGN assay during the previous month, and 5) English fluency; exclusion criteria were: 1) neurocognitive disorder (e.g., mental retardation, autism), 2) prescribed > 1 mg/kg/d corticosteroids, and 3) comorbid chronic illness. Two hundred seventy-one patients who had a 6-TGN/6-MMPN assay performed as part of their clinical care during the prior month were screened for eligibility, and 58 patients met criteria. Screened patients who did not meet criteria were ineligible primarily because they were outside the age range, did not have a confirmed diagnosis of Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, and/or were not prescribed both 6-MP/azathioprine and a 5-ASA. Of those 58 who met criteria, 11 were never reached for recruitment and 5 declined participation.

A sample of 42 adolescents (26 male, 16 female) age 13–17 years (M = 15.62 years, SD = 1.37 years) with a confirmed diagnosis of IBD (Crohn’s disease N = 36; ulcerative colitis N = 6) and their parents served as participants. Families were recruited from a gastroenterology clinic in a large children’s hospital in the northeastern United States. The sample consisted of 88% Caucasian, 9% African American, and 3% Hispanic individuals. Table 1 summarizes additional family demographic data.

Table 1.

Descriptive Data for Family Demographic Variables

| Variable | Mean | Mdn | SD | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal: | ||||

| Age | 45.65 | 45.50 | 5.63 | |

| Marital Status: | ||||

| Single | 2.9% | |||

| Married | 88.2% | |||

| Divorced | 5.9% | |||

| Widowed | 2.9% | |||

| Education: | ||||

| High School | 14.7% | |||

| Vocational Degree | 2.9% | |||

| Partial College | 17.6% | |||

| Associate’s Degree | 2.9% | |||

| College Graduate | 41.2% | |||

| Graduate Degree | 20.6% | |||

| Paternal: | ||||

| Age | 48.33 | 47.00 | 7.82 | |

| Marital Status: | ||||

| Married | 100% | |||

| Education: | ||||

| High School | 12.1% | |||

| Vocational Degree | 3.0% | |||

| Partial College | 27.3% | |||

| Associate’s Degree | 9.1% | |||

| College Graduate | 27.3% | |||

| Graduate Degree | 21.2% | |||

| Family Income | $126,880 | $117,500 | $65,351.29 | |

Measures

A demographic questionnaire assessing family income, parental age, marital status, parental education, and number of family members in the home was completed by parents.

Adherence Assessment

6-MP Metabolite Assay

An intravenous blood draw (approximately 5 cc) was performed on patients for a 6-MP metabolite assay in order to provide an assessment of 6-TGN/6-MMPN red blood cell (RBC) concentration. These values were determined using high-performance liquid chromatography methodology (Prometheus Laboratories, San Diego, CA). Tests to determine thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) were conducted for each patient prior to initiation of 6-MP/azathioprine therapy to determine appropriate dosing for achieving therapeutic 6-TGN levels (i.e., 230–400 pmole).

Medical Adherence Measure (MAM)

The MAM19 is a semi-structured interview that is conducted with both patients and parents and provides quantification of medication nonadherence. It assesses adherence across 4 domains: knowledge, adherence behavior, organizational system, and barriers to medication adherence. The MAM has demonstrated adequate convergent validity (r =−.40, p < .05) and test-retest reliability (r = .89, p < .05).20

Pill Counts

Pill counts of all medication prescribed to patients were conducted by study personnel. Data obtained included prescription instructions, date on which each prescription was filled, quantity filled, and current quantity. Adherence was calculated as percentage of doses consumed using this equation: doses consumed/doses prescribed X 100.

Disease Severity Assessment

Pediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (PCDAI)

The PCDAI21 is a well-validated instrument used to assess disease activity in pediatric patients with Crohn’s disease. The scale is scored 0–100 based on subjective criteria (e.g., pain), objective criteria (e.g., physical exam), laboratory findings, and growth parameters. Scores < 15 = inactive disease; 15–30 = mild to moderate disease, and > 30 = severe disease activity.22 Mean PCDAI score for this sample was 12.15 (SD = 9.60).

Lichtiger Colitis Activity Index (CAI)

The CAI23 is scored 0–21, with higher scores representing more severe disease. It is assessed across 8 ulcerative colitis related variables including number of daily stools, nocturnal diarrhea, visible blood in stool, fecal incontinence, abdominal pain or cramping, general well-being, abdominal tenderness, and need for anti-diarrheal medication. Mean CAI score for this sample was 4.00 (SD = 5.25).

Procedure

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Adolescents who met eligibility criteria and had a 6-TGN/6-MMPN assay performed as part of their clinical care in the previous month and their parents were recruited via telephone. A thorough description of the study was given to the patient and parents, and informed consent and assent was obtained. Patients and parents provided information for pill counts, and the MAM interview was conducted via telephone. Disease and medication regimen information and 6-TGN data were obtained via medical chart review. A demographic questionnaire was mailed to participants with a self-addressed stamped return envelope. Each patient’s gastroenterologist provided information for disease severity assessments. Compensation for participation was a $25 gift card.

Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics (i.e., M, SD, percentages), bivariate correlations, and independent samples t-tests were conducted to identify potential relationships among demographic variables, disease severity, and adherence assessment variables. Nonadherence prevalence was calculated as percent of sample consuming < 80% of a specific medication (i.e., either 6-MP/azathioprine or 5-ASA)/total sample. The cut point of < 80% to represent nonadherence, although arbitrary, has been used in IBD13, 18 and is a convention of adherence literature in general.5 Nonadherence frequency was calculated as mean percent of prescribed doses not taken per patient. Nonadherence prevalence and frequency were also calculated for the subsample of patients who demonstrated both subtherapeutic 6-TGN levels and unquantifiable 6-MMPN levels.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Results of independent t-tests revealed no significant differences between male and female participants on 5-ASA and 6-MP/azathioprine pill count, 5-ASA and 6-MP/azathioprine MAM scores, or 6-TGN/6-MMPN measures of adherence (all p’s > .05) or on PCDAI or CAI total scores (all p’s > .05). No statistically significant correlations were observed between measures of adherence or disease severity and age. Mean number of 5-ASA pills prescribed per day was 9.11 (SD = 2.76); mean number of 6-MP/azathioprine pills prescribed per day was 1.49 (SD = 0.74).

Nonadherence Prevalence

Objective pill count assessment revealed nonadherence prevalence rates of 64% for 6-MP/azathioprine and 88% for 5-ASA medications. In contrast, subjective self-report assessment revealed nonadherence rates of 10% for 6-MP/azathioprine and 2% for 5-ASA. Biomarker data revealed that, although the majority of the sample (93%) demonstrated quantifiable 6-TGN levels, only 14% were within the therapeutic range. Participants in both the subtherapeutic range for 6-TGN and the unquantifiable range for 6-MMPN (N=15) demonstrated nonadherence prevalence rates of 87% for 6-MP/azathioprine and 94% for 5-ASA medications using pill count data. Self-report data was not used in this analysis due to the likelihood that the data obtained represents considerable overestimation of adherence by patients in this sample.

Nonadherence Frequency

Objective assessment revealed a nonadherence frequency of 38% for 6-MP/azathioprine and 49% for 5-ASA medications. Subjective nonadherence frequency was 6% for 6-MP/azathioprine and 3% for 5-ASA. Participants who had both subtherapeutic 6-TGN levels and unquantifiable 6-MMPN levels demonstrated nonadherence frequency rates of 46% for 6-MP/azathioprine and 54% for 5-ASA medications using pill count data. Figure 1 illustrates prevalence and frequency data for each medication via objective and subjective assessments.

Figure 1.

Nonadherence Prevalence and Frequency

Discussion

This study is the first to examine both prevalence and frequency of medication nonadherence in pediatric IBD using a multimethod objective and subjective adherence assessment approach with behavioral and biological measures. Consistent with the primary hypothesis, results indicated that nonadherence prevalence was comparable to other adolescent chronic illness populations. In fact, prevalence of nonadherence was slightly higher for 5-ASA medications (i.e., 88%) using pill count data than has been observed in other adolescent populations. This suggests that this group of medications might be particularly difficult for adolescent patients to take regularly as prescribed. Factors that may make adherence to 5-ASA medications challenging include frequent dosing each day and quantity of pills per dose. Nonadherence frequency pill count data indicated that a considerable percentage of both 6-MP/azathioprine and 5-ASA doses are missed (38% and 49%, respectively). Thus, not only are a majority of IBD patients nonadherent (using < 80% as the cut point), but approximately 40% to 50% of medication doses are missed by patients.

Also consistent with our hypotheses, self-report adherence assessment data yielded considerably lower nonadherence (i.e., high adherence) estimates in this sample. While these data likely represent an overestimation of adherence, which is a common problem in adolescents, the comparison of objective and subjective data in this study highlights an important point: although adolescents demonstrate significant nonadherence to medication, they may not accurately perceive the extent of the problem. This discrepancy between subjective and objective adherence represents a salient opportunity and avenue for intervention by health care providers, and underscores the importance of multimethod adherence assessment.

Examination of bioassay data revealed a low percentage of patients with therapeutic 6-TGN levels, which was possibly a function of pharmacokinetic influence. Moreover, these assays did not accurately reflect objectively measured nonadherence. The exception to this was that patients with subtherapeutic/unquantifiable 6-TGN/6-MMPN levels exhibited extreme nonadherence prevalence and frequency. However, this finding is quite preliminary given the small subsample used. Importantly, perhaps the most significant finding of this study was that nonadherence to one medication was generalizable to the other medication. This was true for both objective and bioassay assessments in which patients that were nonadherent to 6-MP/azathioprine were also nonadherent to 5-ASA medications.

These findings have several clinical implications. Adherence should be monitored by patients, families, and practitioners and assessments should be incorporated into routine visits. Unfortunately, patients do not always bring medication to clinic visits for pill counts, leaving clinicians with restricted and less reliable options, such as self-reports or bioassays. The preliminary data from this study suggest that low metabolite values might indicate nonadherence to oral medication, and could potentially be used as a cursory screener for nonadherence. However, suspected nonadherence should always be verified by validated measures of adherence, and patient nonadherence should be normalized and discussed openly and nonjudgmentally with patients and their families. Ideally, an assessment of treatment adherence should include multiple measures to capitalize on the strengths of each and account for their inherent weaknesses. Although self-reported adherence is likely to be overestimated, it may serve as a catalyst to desensitize patients to discussing adherence issues during clinic appointments, and thus might improve the validity of future self-reporting. Finally, these data indicate that adherence to 5-ASA medications might be particularly challenging and should be considered as a target for intervention (e.g., modification of dosing schedule). Nevertheless, a thorough assessment of which treatments pose adherence difficulties and the specific barriers to completing those treatments is necessary for each patient as specific problem behaviors will vary considerably across patients.

The findings of this study should be considered within the context of several limitations. First, the modest sample size suggests that generalization of these findings should be made with caution. Second, the mean family income in this sample was higher than expected; however, the socioeconomic status of the IBD population is likely negatively skewed compared to other disease populations based on the overrepresentation of Caucasians diagnosed with IBD. Nevertheless, because nonadherence in this sample was similar to that found in other populations, it is unlikely that socioeconomic factors influenced the primary outcome variable in this study. Third, the adherence measures utilized in this study represent assessment tools that can readily be used in clinic or via follow-up telephone contact. Yet, more detailed information regarding patterns of nonadherence would likely have been available with the use of electronic monitoring of medication adherence. Finally, the extent to which metabolism of 6-MP/azathioprine was affected by liver functioning is not known as these tests were not conducted simultaneously with 6-TGN/6-MMPN assays.

Future research efforts focusing on large scale examination of nonadherence in this population is needed to establish generalizability and improve assessment methods; this is currently underway. Second, research should examine the value added contribution of adherence assessment via electronic monitors. The additional data from such an approach would inevitably result in further empirical questions regarding timing and patterns of dosing, and would be useful in developing treatment protocols and calculating optimal timing of such interventions. Additionally, longitudinal approaches to data analyses are needed to examine the predictive utility of various assessments for future adherence behavior. Moreover, statistical and pharmacokinetic modeling of adherence is warranted based on the novelty of this area of research. Finally, studies examining trajectories of adherence during patients’ transition from pediatric to adult health care are critical to understanding the changes in disease management behavior and potential points of intervention during this poorly understood developmental period for patients with IBD.

Acknowledgments

Research supported in part by Procter and Gamble Pharmaceuticals, Prometheus Laboratories, Inc., NIDDK K23 DK079037, and PHS Grant P30 DK 0789392.

References

- 1.Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, et al. The prevalence and geographic distribution of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in the United States. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2007;5:1424–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(WHO) WHO. Adherence to long-term therapies: Evidence for action. 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berg JS, Dischler J, Wagner DJ, Raia JJ, Palmer-Shevlin N. Medication compliance: a healthcare problem. Ann Pharmacother. 1993 Sep;27(9 Suppl):S1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemanek K. Adherence issues in the medical management of asthma. J Pediatr Psychol. 1990 Aug;15(4):437–458. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/15.4.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rapoff MA. Adherence to pediatric medical regimens. New York: Kluwer Academic; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sly RM. Mortality from asthma in children 1979–1984. Ann Allergy. 1988 May;60(5):433–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernal I, Domenech E, Garcia-Planella E, et al. Medication-taking behavior in a cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2006;51:2165–2169. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9444-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ediger JP, Walkker JR, Graff L, Lix L, Clara I, Rawsthorne P, Rogala L, Miller N, McPhail C, Deering K, Bernstein CN. Predictors of medication adherence in inflammatory bowel diease. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2007;102:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sewitch MJAM, Barkun A, Bitton A, Wild GE, Cohen A, Dobkin PL. Patient nonadherence to medication in inflammatory bowel disease. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2003;98(7):1535–1544. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hommel KA, Mackner LM, Denson LA, Crandall WV. Treatment Regimen Adherence in Pediatric Gastroenterology. Journal of Pediatric Gastroeneterology and Nutrition. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318175dda1. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Logan D, Zelikovsky N, Labay L, Spergel J. The Illness Management Survey: identifying adolescents’ perceptions of barriers to adherence. J Pediatr Psychol. 2003 Sep;28(6):383–392. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsg028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mackner LM, Crandall WV. Oral medication adherence in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005 Nov;11(11):1006–1012. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000186409.15392.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oliva-Hemker MM, Abadom V, Cuffari C, Thompson RE. Nonadherence with thiopurine immunomodulator and mesalamine medications in children with Crohn disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007 Feb;44(2):180–184. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31802b320e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riekert KA, Drotar D. The Beliefs About Medication Scale: Development, Reliability, and Validity. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2002;9(2):177–184. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belaiche J, Desager JP, Horsmans Y, Louis E. Therapeutic drug monitoring of azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine metabolites in Crohn disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001 Jan;36(1):71–76. doi: 10.1080/00365520150218084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuffari C, Seidman EG, Latour S, Theoret Y. Quantitation of 6-thioguanine in peripheral blood leukocyte DNA in Crohn’s disease patients on maintenance 6-mercaptopurine therapy. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1996 May;74(5):580–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dubinsky MC, Lamothe S, Yang HY, et al. Pharmacogenomics and Metabolite Measurement for 6-Mercaptopurine Therapy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:705–713. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kane S, Huo D, Aikens J, Hanauer S. Medication Nonadherence and the Outcomes of Patients with Quiescent Ulcerative Colitis. The American Journal of Medicine. 2003;114:39–43. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01383-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zelikovsky NSAP. Eliciting accurate reports of adherence in a clinical interview: Development of the medical adherence measure. Pediatric Nursing. in press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zelikovsky N. Medical Adherence Measure. 2007 Unpublished data. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hyams JS, Ferry GD, Mandel FS, et al. Development and validation of a pediatric Crohn’s disease activity index. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1991 May;12(4):439–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Otley A, Loonen H, Parekh N, Corey M, Sherman PM, Griffiths AM. Assessing activity of pediatric Crohn’s disease: which index to use? Gastroenterology. 1999 Mar;116(3):527–531. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lichtiger S, Present DH, Kornbluth A, et al. Cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis refractory to steroid therapy. N Engl J Med. 1994 Jun 30;330(26):1841–1845. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406303302601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]