Abstract

As part of our ongoing surveillance efforts for West Nile virus (WNV) in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico, 96,687 mosquitoes collected from January through December 2007 were assayed by virus isolation in mammalian cells. Three mosquito pools caused cytopathic effect. Two isolates were orthobunyaviruses (Cache Valley virus and Kairi virus) and the identity of the third infectious agent was not determined. A subset of mosquitoes was also tested by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using WNV-, flavivirus-, alphavirus-, and orthobunyavirus-specific primers. A total of 7,009 Culex quinquefasciatus in 210 pools were analyzed. Flavivirus RNA was detected in 146 (70%) pools, and all PCR products were sequenced. The nucleotide sequence of one PCR product was most closely related (71–73% identity) with homologous regions of several other flaviviruses, including WNV, St. Louis encephalitis virus, and Ilheus virus. These data suggest that a novel flavivirus (tentatively named T’Ho virus) is present in Mexico. The other 145 PCR products correspond to Culex flavivirus, an insect-specific flavivirus first isolated in Japan in 2003. Culex flavivirus was isolated in mosquito cells from approximately one in four homogenates tested. The genomic sequence of one isolate was determined. Surprisingly, heterogeneous sequences were identified at the distal end of the 5′ untranslated region.

INTRODUCTION

Arthropod-borne viruses (arboviruses) are significant causes of human and animal disease throughout the world.1 Most arboviruses of medical significance belong to three genera: Flavivirus (family Flaviviridae), Alphavirus (family Togaviridae) and Orthobunyavirus (family Bunyaviridae). The most important flaviviruses in terms of human health are the four serotypes of dengue virus (DENV 1–4).2,3 In Latin America, more than 850,000 cases of dengue fever, including 25,000 cases of dengue hemorrhagic fever, occurred in 2007. West Nile virus (WNV) has also been responsible for human illness in Latin America although the incidence of reported WNV disease in this region is remarkably low compared with the United States. 4,5 Other Latin American flaviviruses that cause human disease are yellow fever virus (YFV), St. Louis encephalitis virus (SLEV), Ilheus virus (ILHV), Rocio virus (ROCV), Bussuquara virus (BSQV), and Cacipacore virus.6

Despite the relatively low number of WNV cases that have occurred in Latin America, serologic data from equine and avian infection surveillance have provided evidence that WNV is circulating throughout much of Mexico,7–9 and parts of Central and South America. 10–13 In our surveillance studies, we have provided serologic evidence of widespread WNV activity in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico. 9,14,15 Our earliest evidence of WNV activity was the detection of antibodies to this virus in horses at study sites in Tizimin and Caucel, Yucatan State in 2002.9 Antibodies to WNV were also identified in birds in Hobonil, Yucatan State in 2002 and 2003, horses on Cozumel Island, Quintana Roo State in 2003, birds and mammals from the Merida zoo, Yucatan State in 2003 and 2004, and farmed crocodiles in Ciudad del Carmen, Campeche State in 2004. 14,15 However, there have been no confirmed reports of WNV illness in humans, horses or birds in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico. The reasons for the dramatically different disease outcomes in WNV-infected vertebrates in the Yucatan Peninsula and elsewhere in Latin America as compared with the United States are not known. One explanation is that a subset of vertebrates from the Yucatan Peninsula considered to be seropositive for WNV had been infected with an unrecognized WNV-like virus, rather than WNV. Another explanation is that pre-existing immunity to another flavivirus is providing partial protection to subsequent WNV infection. Other explanations include under-reporting, the emergence of attenuated WNV variants, and geographic differences in the species composition, relative abundance and susceptibility of vertebrates or vectors.

To increase our knowledge of the diversity of arboviruses and mosquito species in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico, and to obtain data that could explain the lack of reported WNV illness in this area, we conducted extensive mosquito surveillance for arboviruses in the states of Yucatan and Quintana Roo. Study sites were established in geographically diverse locations, but most time and effort was devoted to the capture of mosquitoes at sites where we had previously detected WNV activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Description of study sites

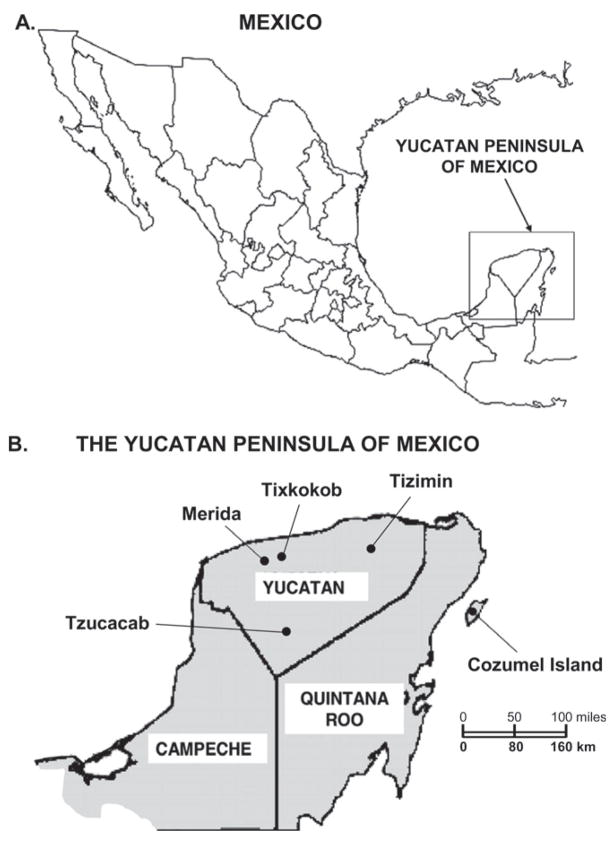

Mosquitoes were trapped in five areas: Merida, Tixkokob, Tizimin, and Tzucacab in Yucatan State, and Cozumel Island in Quintana Roo State (Figure 1). Five study sites were established in Merida, including one site in the Merida zoo. Merida is the capital city of Yucatan State and has a population of approximately 750,000. Another three study sites were located in Tixkokob, a small town 15 km (9 miles) east of Merida. Livestock (horse and cattle) production is common in this area. In Tizimin, five study sites were established. Tizimin is a small city 160 km (100 miles) east of Merida. Livestock production is also common in this area. Two more study sites were established in Tzucacab, a small town 120 km (75 miles) south of Merida. Tzucacab is located in an agricultural region that supports the production of maize and citrus. On Cozumel Island, mosquitoes were collected at six study sites. Cozumel is a 460 km2 coralline limestone island approximately 16 km (10 miles) off the east coast of the Mexican mainland. It is a popular tourist destination. The main vegetation is coastal mangrove forest, tropical deciduous forest, and tropical semi-deciduous forest. All sites used in this investigation are characterized by a tropical climate.

Figure 1.

A, Location of the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico. B, Study sites for mosquito collections.

Trapping schedules

Mosquitoes were collected in Merida and Tixkokob from January to December 2007. Mosquitoes were usually trapped at each site five days a week every other week. Cozumel Island was visited on two occasions (October 16–18, December 11–17). During this time, mosquitoes were trapped daily at each site. Tizimin was visited once (September 13–15), as was Tzucacab (November 27–29), and each site was trapped daily.

Sampling methods

Mosquitoes were sampled using mosquito magnets and backpack-mounted aspirators. Mosquito magnets Pro-Liberty (American Biophysics Corp, North Kingstown, RI) were baited with propane and octenol. CO2 is generated as a byproduct of propane combustion. These traps contain two fans operated by a rechargeable battery: one fan exhausts CO2 from the trap and the other fan sucks air into the trap. Mosquito magnets were turned on between 4:00 PM and 6:00 PM and collection nets were replaced the following morning between 6:00 AM and 9:00 AM. One or two mosquito magnets were set at each study site. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) back-pack mounted aspirators were used to collect resting mosquitoes from outdoor vegetation and concrete surfaces. 16 One research technician searched for resting mosquitoes for at least 20 minutes at each study site. Mosquitoes collected at study sites in Yucatan State were transported alive to the Universidad Autonoma de Yucatan (UADY), frozen in a −70°C freezer, and identified on chill tables according to species and sex using morphologic characteristics. Mosquitoes collected on Cozumel Island were anesthetized using triethylamine, 17 identified using morphologic characteristics, placed into screw-capped cryostorage vials, and transported in liquid nitrogen to UADY. Every three months, mosquitoes were transported on dry ice from the UADY to Iowa State University (ISU) by World Courier.

Mosquito homogenization

Mosquitoes were placed in poly-propylene, round-bottom 5-mL tubes with 1.8 mL of diluent that consisted of CO2-independent cell culture medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 2.5 μg/mL fungizone. Four 4.5-mm-diameter copper-clad steel beads (BB-caliber airgun shot) were added to each tube, and mosquito pools were homogenized by vortexing for 30 seconds. Mosquito homogenates were centrifuged (2,200 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C), and supernatants were collected.

Virus isolation in Vero cells

An aliquot (100 μL) of each supernatant was added to 0.5 mL of diluent, filtered using a 0.22-μm filter and inoculated onto subconfluent monolayers of African green monkey kidney (Vero) cells in 6-well plates. Cells were incubated for at least one hour at room temperature on an orbital shaker to enable attachment of the virus. Next, 300 μL of each inocula was discarded, and 5 mL of minimum essential medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum, L-glutamine, penicillin, streptomycin, and fungizone was added to each well. Cells were incubated at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2 for 14 days and monitored regularly. If a cytopathic effect (CPE) was observed, two additional blind passages were performed and supernatants were harvested. All virus isolation experiments were conducted in the Biosafety Laboratory 3 facilities at ISU. All samples that caused CPE were tested by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) to identify the cytopathic virus.

Virus isolation in C6/36 cells

An aliquot (100 μL) of selected supernatants was added to 2 mL of Liebovitz L15 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum, L-glutamine, penicillin, streptomycin, and fungizone. Samples were filtered and inoculated onto subconfluent monolayers of Aedes albopictus C3/36 cells in 75-cm2 flasks. Cells were incubated for at least one hour at room temperature on an orbital shaker to allow attachment of the virus. Another 12 mL of L15 maintenance medium was added to each flask, and cells were incubated at 28°C for 7 days. After two additional blind passages, supernatants were harvested.

Virus identification by RT-PCR sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from cell culture supernatants and mosquito homogenates using the QIAamp viral RNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and analyzed by RT-PCR using primers specific for WNV, flaviviruses, alphaviruses, and orthobunyaviruses. The WNV-specific primers, WN233 (5′-TTG TGT TGG CTC TCT TGG CGT TCT T-3′) and WN640c (5′-CAG CCG ACA GCA CTG GAC ATT CAT A-3′), target a 408-nucleotide region of capsid-membrane genes. 18 The flavivirus-specific primers, FU2 (5′-GCT GAT GAC ACC GCC GGC TGG GAC AC-3′) and cFD3 (5′-AGC ATG TCT TCC GTG GTC ATC CA-3′), target a 845-nucleotide region of the nonstructural protein 5 (NS5) gene. 19 The alphavirus-specific primers, VIR966 (5′-TCC ATG CTA ATG CTA GAG CGT TTT CGC A-3′) and VIR966c (5′-TGG CGC ACT TCC AAT GTC CAG GAT-3′), target a 98-nucleotide region of the NSP1 gene. 20 The orthobunyavirus-specific primers, BCS82 (5′-ATG ACT GAG TTG GAG TTT CAT GAT GT-3′) and BCS332V (5′-TGT TCC TGT TGC CAG GAA AAT-3′), target a 251-nucleotide region of the small RNA segment. 21 Various primers specific for the novel flavivirus were also used, including Z97-03F (5′-ACT GGC AAG AAG TCC CCT TT-3′) and Z97-03R (5′-ACA TAT TGC GTT TGC CAT GA-3′), which target a 236-nucleotide region of the NS5 gene, and Z97-07F (5′-CAC ACC ACA CCA TTT GGC CAG CAA C-3′) and Z97-05R (5′-GTC TCT TGT GGT CAC CAT CCA TC-3′) which target a 658-nucleotide region of the NS5 gene.

Complementary DNAs were generated using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, an aliquot of total RNA (1–2 μg) was mixed with 500 μM of each dNTP and 25 ng of primer and heated at 70°C for 10 minutes. After briefly chilling on ice, samples were added to 200 units of Superscript III reverse transcriptase in 1× reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3), 75 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol and incubated at 50°C for 1 hour, followed by 70°C for 15 minutes. PCR amplifications were performed using 1 μL of cDNA template, 0.1 unit of Taq polymerase, 25 ng of each primer and each dNTP at 200 μM in 1× PCR buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.4, 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2). Reactions were performed as follows: 94°C for 3 minutes, 30 cycles at 94°C for 30 seconds, 50°C for 45 seconds, and 72°C for 2 minutes, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 8 minutes. In some instances, touchdown PCR was also performed; these reactions were conducted using annealing temperatures decreasing from 60°C to 41°C over 20 cycles, followed by 39 cycles with annealing at 54°C. An aliquot of each PCR product was examined by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel, visualized with ethidium bromide, and extracted using the Purelink gel extraction kit (Invitrogen). Purified DNAs were sequenced in both directions using a 3730x1 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) at ISU.

Genomic sequencing of Culex flavivirus

Primers for the RT-PCR amplification and sequencing of Culex flavivirus (CxFV) were designed using the genomic sequence of a Japanese CxFV isolate (strain NIID-21). 22 The resulting PCR products were sequenced and used to design additional primers. A total of 24 pairs of overlapping primers were used (primer sequences are available upon request). The extreme 5′ and 3′ ends of the CxFV genome were determine by 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) and 3′ RACE, respectively. In the 5′ RACE reactions, total RNA was reversed transcribed using a CxFV-specific primer. Complementary DNAs were purified by ethanol precipitation and oligo(dC) tails were added to the 3′ ends using 15 units of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in 1× tailing buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.4, 25 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 0.02 mM dCTP). Tailing reactions were performed at 37°C for 30 minutes and terminated by heat inactivation (65°C for 10 minutes). Oligo dC-tailed cDNAs were purified by ethanol precipitation and PCR amplified using a consensus forward primer specific to the C-tailed termini (5′-GAC ATC GAA AGG GGG GGG GGG-3′) and a reverse primer specific to the CxFV cDNA sequence. In the 3′ RACE reactions, polyadenylate [poly(A)] tails were added to the 3′ ends of the CxFV genomic RNA using 6 units of poly(A) polymerase (Ambion, Austin, TX) in 1× reaction buffer (40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM MnCl2, 250 mM NaCl, 50 μg of bovine serum albumin/mL, and 1 mM ATP). Tailing reactions were performed at 37°C for 1 hour and terminated by heat inactivation (65°C for 10 minutes). Poly(A)-tailed RNA was reverse transcribed using a poly(A) tail–specific primer (5′-GGC CAC GCG TCG ACT AGT ACT TTT TTT TTT TTT TTT T-3′). Complementary DNAs were PCR amplified using a forward primer specific to the CxFV cDNA sequence and a reverse primer that matched the 5′ half of the poly (A)-specific reverse transcription primer (5′-GGC CAC GCG TCG ACT AGT AC-3′).

The PCR products generated from the 5′ and 3′ RACE reactions were inserted into the pCR4-TOPO cloning vector (Invitrogen), and ligated plasmids were transformed into competent TOPO10 Escherichia coli cells (Invitrogen). Cells were grown on Luria-Bertani agar containing ampicillin (50 μg/mL) and kanamycin (50 μg/mL), and colonies were screened for inserts by PCR amplification. An aliquot of each PCR product was examined by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel, and several PCR products were purified using a QIAquick spin column (Qiagen) and sequenced using a 3730x1 DNA sequencer.

RESULTS

Mosquito collections

A total of 96,687 mosquitoes were collected in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico from January to December 2007 (Table 1). Of these, 79,435 (82.2%) were identified as females and 17,252 (17.8%) were identified as males. The mosquitoes represented 9 genera and at least 26 species. The most common species was Culex quinquefasciatus, which made up 48.3% of the total sample population, followed by Aedes taeniorhynchus (29.6%) and Anopheles albimanus (6%). Most (84.3%) mosquitoes were collected using mosquito magnets. The ratio of females to males was 1 to 0.4 when backpack-mounted aspirators were used and 1 to 0.2 when mosquito magnets were used.

Table 1.

Summary of mosquitoes collected in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico, January–December 2007

| No.of pools | No. of mosquitoes |

% Total sample population | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Females | Males | Total | ||

| Aedes aegypti | 217 | 837 | 548 | 1,385 | 1.4 |

| Ae. taeniorhynchus | 673 | 28,533 | 61 | 28,594 | 29.6 |

| Ae. trivittatus | 131 | 3,909 | 40 | 3,949 | 4.1 |

| Anopheles albimanus | 137 | 5,765 | 0 | 5,765 | 6.0 |

| An. crucians | 16 | 670 | 0 | 670 | 0.7 |

| An. neivai | 8 | 381 | 0 | 381 | 0.4 |

| An. pseudopuctipennis | 10 | 116 | 1 | 117 | 0.1 |

| An. vestitipennis | 40 | 1,353 | 0 | 1,353 | 1.4 |

| An. spp. | 4 | 207 | 0 | 207 | 0.2 |

| Culex coronator | 18 | 49 | 0 | 49 | 0.1 |

| Cx. interrogator | 8 | 112 | 0 | 112 | 0.1 |

| Cx. nigripalpus | 6 | 102 | 0 | 102 | 0.1 |

| Cx. quinquefasciatus | 1,236 | 30,120 | 16,602 | 46,722 | 48.3 |

| Cx. tarsalis | 1 | 20 | 0 | 20 | < 0.1 |

| Deinocerites cancer | 3 | 12 | 0 | 12 | < 0.1 |

| Haemagogus mesodentatus | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | < 0.1 |

| Mansonia dyari | 1 | 8 | 0 | 8 | < 0.1 |

| Ma. tillans | 53 | 1,657 | 0 | 1,657 | 1.7 |

| Ochlerotatus infirmatus | 1 | 8 | 0 | 8 | < 0.1 |

| Psorophora albipes | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | < 0.1 |

| Ps. ciliata | 2 | 18 | 0 | 18 | < 0.1 |

| Ps. columbiae | 24 | 844 | 0 | 844 | 0.9 |

| Ps. confinnis | 5 | 8 | 0 | 8 | < 0.1 |

| Ps. canescens | 83 | 3,224 | 0 | 3,224 | 3.3 |

| Ps. ferox | 25 | 924 | 0 | 924 | 1.0 |

| Ps. howardii | 18 | 507 | 0 | 507 | 0.5 |

| Ps. species | 4 | 35 | 0 | 35 | < 0.1 |

| Wyeomyia spp. | 3 | 13 | 0 | 13 | < 0.1 |

| Total | 2,730 | 79,435 | 17,252 | 96,687 | 99.9 |

Collections were made at multiple sites in five study areas: Merida, Tixkokob, Tizimin, and Tzucacab in Yucatan State, and Cozumel Island in Quintana Roo State (Table 2 and Figure 1). Species diversity was greatest on Cozumel Island; at least 19 different species were collected in this area. The most common species on Cozumel Island was Ae. taeniorhynchus, which represented 52% of the mosquitoes collected in this area. The species most frequently collected at the Merida zoo was Cx. quinquefasciatus, which represented 80% of the sample population. The species most frequently collected elsewhere in Merida was Ae. taeniorhynchus (54%). Culex quinquefasciatus made up most collections at Tixkokob and Tizimin (93% and 75%, respectively). No Cx. quinquefasciatus were collected at Tzucacab, where the most common species was Mansonia titillans (53%).

Table 2.

Numbers of mosquitoes collected according to study area, Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico, January–December 2007

| Study area, no. (%) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Cozumel | Merida* | Tixkokob | Tizimin | Tzucacab | Zoo | Total |

| Aedes aegypti | 10 | 306 | 541 | 42 | 0 | 486 | 1,385 |

| Ae. taeniorhynchus | 12,597 | 12,273 | 1,757 | 1 | 3 | 1,963 | 28,594 |

| Ae. trivittatus | 2,815 | 707 | 171 | 0 | 242 | 14 | 3,949 |

| An. albimanus | 462 | 5,298 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 5,765 |

| An. crucians | 662 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 670 |

| An. neivai | 381 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 381 |

| An. pseudopuctipennis | 0 | 116 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 117 |

| An. vestitipennis | 1,229 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 115 | 0 | 1,353 |

| Anopheles spp. | 207 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 207 |

| Culex coronator | 0 | 30 | 0 | 18 | 0 | 1 | 49 |

| Cx. interrogator | 20 | 72 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 112 |

| Cx. nigripalpus | 102 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 102 |

| Cx. quinquefasciatus | 1,168 | 3,511 | 31,833 | 184 | 0 | 10,026 | 46,722 |

| Cx. tarsalis | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| Deinocerites cancer | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| Haemagogus mesodentatus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Mansonia dyari | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| Ma. titillans | 134 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 1,494 | 0 | 1,656 |

| Ochlerotatus infirmatus | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 9 |

| Psorophora albipes | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Ps. ciliata | 0 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 |

| Ps. columbiae | 844 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 844 |

| Ps. confinnis | 1 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Ps. cyanescens | 2,973 | 248 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3,223 |

| Ps. ferox | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 920 | 0 | 924 |

| Ps. howardii | 505 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 507 |

| Ps. species | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 0 | 35 |

| Wyeomyia spp. | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

| Total (%) | 24,151 (25.0) | 22,658 (23.4) | 34,331 (35.5) | 246 (0.3) | 2,805 (2.9) | 12,496 (12.9) | 96,687 (100) |

Does not include mosquitoes collected in the Merida zoo.

Virus isolations in Vero cells

Three of 2,730 mosquito pools caused virus-like CPE in Vero cells. All three pools consisted of female Ae. taeniorhynchus collected in Merida in November using mosquito magnets. One isolate was identified as Cache Valley virus by RT-PCR sequencing (Genbank accession no. EU879062). Another isolate was identified as Kairi virus by RT-PCR sequencing (Genbank accession no. EU879063). The genomic RNA of the Kairi virus isolate was amplified by touch-down RT-PCR. The standard RT-PCR protocol failed to generate a product. The identity of the third infectious agent was not determined, but it was not recognized with any of the flavivirus-, alphavirus-, or orthobunyavirus-specific primers described in the Materials and Methods, or with various other flavivirus-, alphavirus-, and orthobunyavirus-specific primers that were used.

RT-PCR analysis of mosquito homogenates

A subset of mosquito homogenates was tested by RT-PCR using primers specific for WNV, flaviviruses, alphaviruses, and orthobunyaviruses. A total of 7009 (7.2%) mosquitoes from 210 pools were analyzed. All were female Cx. quinquefasciatus collected from June through August 2007. Of these, 4,615 mosquitoes (140 pools) were from Tixkokob, and 2,394 mosquitoes (70 pools) were from the Merida zoo. All pools were negative for WNV, alphavirus, and orthobunyavirus RNA. Flavivirus RNA was detected in 146 (70%) pools. Of these, 120 pools were from Tixkokob and 26 pools were from the Merida zoo. The overall flavivirus minimum infection rate (MIR), expressed as the number of positive mosquito pools per 1,000 mosquitoes tested, was 20.8. The flavivirus MIRs for Tixkokob and the Merida zoo were 26.0 and 10.9, respectively. All PCR products were sequenced; 145 sequences corresponded to CxFV and the other to a novel flavivirus as described below.

T’Ho virus

A 1,358-nucleotide region of the NS5 gene of the novel flavivirus was sequenced (Genbank accession no. EU879061). ClustalW alignment showed that this nucleotide sequence is most closely related to the homologous region of SLEV (72.6% identical), followed by ILHV (72.2%), Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV; 72.1%), Usutu virus (USUV; 71.8%), ROCV (71.4%), Murray Valley encephalitis virus (MVEV; 71.3%), and WNV (71.1%) (Table 3). The deduced amino acid sequence is most closely related to the homologous region of ILHV (80.5% identical, 91.2% similar), SLEV (79.6% identical, 90.3% similar), WNV (79.2% identical, 91.6% similar), ROCV (79% identical, 88.9% similar), and JEV (77% identical, 89.9% similar). These data suggest that a novel flavivirus that is genetically equidistant from a number of other flaviviruses, including WNV, is circulating in Mexico. We have tentatively named this virus T’Ho virus (T’Ho is the Mayan word for Merida). Although we successfully amplified viral RNA, we were not able to obtain an isolate by virus isolation in Vero cells, C6/36 cells, or suckling mouse brain inoculation.

Table 3.

Genetic relatedness between T’Ho virus and selected other flaviviruses*

| Virus | % Nucleotide identity | % Amino acid identity | % Amino acid similarity |

|---|---|---|---|

| St. Louis encephalitis† | 72.6 | 79.6 | 90.3 |

| Ilheus† | 72.2 | 80.5 | 91.2 |

| Japanese encephalitis† | 72.1 | 77.0 | 89.9 |

| Usutu† | 71.8 | 76.8 | 89.8 |

| Rocio† | 71.4 | 79.0 | 88.9 |

| Murray Valley encephalitis† | 71.3 | 76.8 | 90.3 |

| West Nile† | 71.1 | 79.2 | 91.6 |

| Bagaza† | 70.1 | 77.4 | 89.4 |

| Dengue type 1 | 67.7 | 72.3 | 83.6 |

| Dengue type 2 | 67.7 | 72.1 | 84.7 |

| Dengue type 3 | 67.4 | 71.5 | 82.3 |

| Dengue type 4 | 67.4 | 68.4 | 84.5 |

| Yellow fever | 65.5 | 68.6 | 83.8 |

| Tick-borne encephalitis | 63.3 | 65.7 | 80.3 |

| Cell fusing agent | 54.8 | 47.6 | 66.8 |

Nucleotide identities are based on a 1,358-nucleotide fragment of the nonstructural protein 5 (NS5) gene of T’Ho virus. Amino acid identities and similarities are based on a 452-residue region of the NS5 protein of T’Ho virus and were calculated as described by Altschul and others. 51 The highest number in each column is denoted in bold.

The nucleotide and predicted amino acid sequences of the denoted viruses are not significantly more distant (P ≥ 0.05) from T’Ho virus than the closest virus using the two-sample test of equal proportions with continuity correction; this test assumes sites are independent.

The 1,358-nucleotide fragment of T’Ho virus was generated in several RT-PCRs and sequencing reactions. Initially, a 845-nucleotide fragment was amplified and sequenced using the flavivirus-specific primers FU2 and cFD3. The sequence data were used to generate additional forward and reverse primers. Additional primers were also developed from conserved nucleotide sequences identified after the alignment of the NS4B-NS5 genes of various flaviviruses. Using primers Z97-07F and Z97-05R, we amplified and sequenced another 513 nucleotides of upstream sequence.

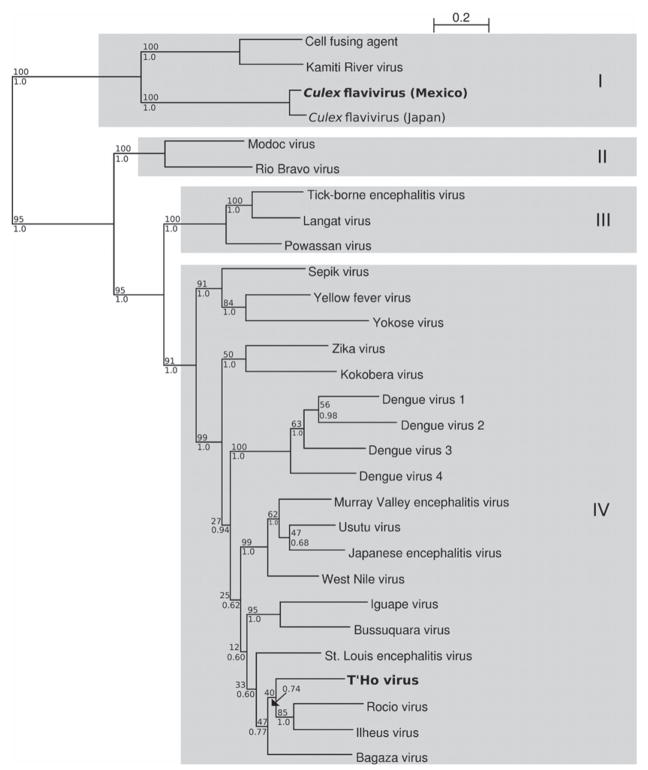

A phylogenetic tree was constructed with Bayesian methods using the 1,358-nucleotide fragment of T’Ho virus and the homologous regions of 29 other flaviviruses (Figure 2). Phylogenetic trees were also constructed by neighbor-joining (NJ), maximum parsimony (MP), and maximum likelihood (ML) analyses. In the Bayesian tree, T’Ho virus is most closely related to SLEV, ILHV, ROCV and Bagaza virus, although the posterior support (0.60) for this mono-phyletic grouping is not strong. These viruses cluster within a larger group that contains WNV, MVEV, USUV, JEV, Iguape virus, and BSQV. The posterior support (0.62) for this topologic arrangement is also low. Because the branching location of T’Ho virus is not highly supported by bootstrap analysis, we checked for possible mosaicism, which can be caused by recombination or strongly convergent evolution, by comparing this sequence to the homologous regions of WNV, SLEV, JEV, and DENV1-4 using the dual multiple change-point model described by Minin and others. 23 T’Ho virus is approximately equidistant to each of these viruses. The 5′ end of the T’Ho virus sequence is fairly confidently placed between DENV1-4 and the other three viruses, but the placement of 3′ end of the genome is ambiguous. There is no strong evidence of mosaicism, but there is continued ambiguity in its placement. The overall topology of the Bayesian tree is consistent with that observed in other phylogenetic trees constructed using flavivirus NS5 gene sequences. 24 Four distinct clades can be observed with the viruses clustering according to their vector-host relationship. Clade I is comprised of insect-specific viruses, clade II is comprised of viruses with no known vector, clade III is comprised of tick/vertebrate viruses and clade IV (which includes T’Ho virus) contains mosquito/vertebrate viruses. The ML-estimated tree was identical to the Bayesian tree. Trees generated by NJ and MP analyses show the same overall topologic features, although there are differences in the branching order within clade IV, where posterior support is low, and the NJ method placed the outgroup within clade IV. Taken together, the findings from the sequencing and phylogenetic studies demonstrate that we have isolated RNA from a new flavivirus that is genetically equidistant from a number of other flaviviruses.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of T’Ho virus. The displayed phylogeny was estimated by using the program MRBAYES, version 3.1. 45 Phylogenetic analysis is based on the 1358-nucleotide fragment encoding a portion of the nonstructural protein 5 (NS5) gene of 30 flaviviruses. The tree is rooted by using Tamana bat virus (Genbank accession no. AF285080) as the outgroup, which is not shown. The polyprotein amino acid sequences of all selected reference viruses were aligned using MUSCLE. 46 The NS5 amino acid sequence of T’Ho virus was profile aligned to the polyprotein alignment using ClustalW and the alignment was trimmed to the ends of the T’Ho virus fragment. 47 The amino acid alignment was converted to a nucleotide alignment using in-house software. jModelTest was used to select the best fitting nucleotide substitution model using AIC. 48 The GTR + G + I model was selected, and this model was used for all model-based inference, except neighbor-joining, in which GTR + G was used to compute pairwise distances. Phyml was used to infer the maximum likelihood tree using the general time reversible gamma + proportion invariant (GTR + G + I) model selected by jModelTest. 49 One hundred bootstrap trials were also carried out using phyml. MrBayes was used to infer the posterior majority rule consensus tree along with posterior support for all internal branches assuming the GTR + G + I model and all default settings. 45,50 As per the default, two parallel runs of four (three heated) Metropolis-coupled Markov chain Monte Carlo chains were run for 1,000,000 iterations, subsampling every 100 samples. The first 200,000 iterations were discarded as burn in when estimating the tree shown here. All branches are labeled with bootstrap support (of 100) above and posterior support below. Viruses identified in this study are denoted in bold. GenBank accession nos. for sequences used in the phylogenetic analysis are Bagaza (AY632545), Bussuquara (AY632536), Cell fusing agent (M9167), Culex flavivirus (Japan; AB377213), Culex flavivirus (Mexico; EU879060), Dengue type 1 (U88535), Dengue type 2 (M20558), Dengue type 3 (M93130), Dengue type 4 (M14931), Iguape (AY632538), Ilheus (AY632539), Japanese encephalitis (M18370), Kamiti River (AY149905), Kokobera (AY632541), Langat (AF253419), Modoc (AJ242984), Murray Valley encephalitis (AF161266), Powassan (L06436), Rio Bravo (AF144692), Rocio (AY632542), Sepik (DQ837642), St. Louis encephalitis (EF158060), Tick-borne encephalitis (U27495), T’Ho (EU879061), Usutu (AY453412), West Nile (AY660002), Yellow fever (AF094612), Yokose (AB114858), and Zika (AY632535) viruses. The scale is measured in expected number of mutations per site.

The RNA from T’Ho virus was obtained from a pool of female Cx. quinquefasciatus collected in the Merida zoo using a backpack-mounted aspirator in August 2007. As a result, all mosquitoes collected at the zoo were tested by RT-PCR using primers Z97-03F and Z97-03R, which recognize T’Ho virus, but not CxFV. A total of 12,496 mosquitoes (458 pools) were tested and all were negative. All mosquitoes from the zoo were also tested by RT-PCR using WNV-specific primers and all were negative.

Culex flavivirus

As already noted, 145 of the 146 PCR products sequenced using the flavivirus-specific primers correspond to CxFV, an insect-specific flavivirus first isolated from Culex spp. mosquitoes in Japan in 2003. 22 We also detected CxFV sequence in pools comprised of all male Cx. quinquefasciatus, which supported the findings of Hoshino and others that CxFV can be transmitted vertically in nature. 22 Alignment of these 145 sequences showed that they all match precisely with one another. Virus was isolated from 7 (27%) of 26 homogenates after three blind passages in C6/36 cells as determined by RT-PCR. A CPE was not observed in any cultures. To more conclusively demonstrate that CxFV had been isolated, and that the RT-PCRs were not detecting RNA from non-viable virus present in the original homogenates, additional experiments were performed. Briefly, two aliquots of CxFV inocula collected after the third blind passage in C6/36 cells were diluted 10-fold in phosphate-buffered saline. One aliquot was heated at 56°C for 30 minutes followed by 95°C for 10 minutes to inactivate all virus particles that were present; the other aliquot was not heated. Each sample was subjected to three additional blind passages in C6/36 cells. After the final passage, an aliquot of each supernatant was tested for CxFV RNA by RT-PCR. CxFV RNA was detected in the supernatant of cells that had been inoculated with non-heated material. In contrast, CxFV RNA was not detected when heated material had been used. Taken together, these data suggest that we had isolated CxFV. We did not detect CxFV RNA by RT-PCR in Vero or LLMCK2 cell cultures after three blind passages, a finding that is consistent with earlier observations that CxFV is insect-specific. 22

One isolate from Tixkokob (denoted as CxFV-Mex07) was completely sequenced using a combination of RT-PCR, 5′ RACE, and 3′ RACE (Genbank accession no. EU879060). The genomic RNA contains a single 10,089-nucelotide open reading frame (ORF) that is flanked by 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs). The ORF and 3′UTR (657 nucleotides) are identical in length to those of NIID-21 (a CxFV isolate from Japan). However, the 5′UTR of CxFV-Mex07 is unusual because heterogeneous sequences were identified at its distal end. Fourteen cDNA clones were analyzed by 5′ RACE and automated sequencing. The lengths of the 5′UTRs encoded by these cloned cDNAs are variable, ranging from 91 to 164 nucleotides (Table 4). The 91 nucleotides immediately upstream of the ORF are identical for each clone. We have not included the heterogeneous sequences in the corresponding GenBank entry. The three longest heterogeneous sequences were aligned with all sequences in the Genbank database, and none have significant similarity to any known sequences (all E values were ≥ 2.4). The longest heterogeneous sequences are comprised mostly of cytosines and guanines. Heterogeneous sequences are not present at the distal end of the 5′UTR of NIID-21. 22 The 5′UTR of NIID-21 is identical in length to the homogeneous 5′UTR sequence of CxFV-Mex07, and these two sequences share 95.6% identity.

Table 4.

Length and nucleotide composition of the heterogeneous sequences identified at the distal end of the 5′-untranslated regions of the Mexican strain of Culex flavivirus

| Clone | Length (nucleotides) of entire 5′-untranslated region |

Length (nucleotides) of heterogeneous sequence |

Heterogeneous sequence (5′ → 3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 91 | 0 | – |

| 2 | 91 | 0 | – |

| 3 | 91 | 0 | – |

| 4 | 92 | 1 | T |

| 5 | 92 | 1 | T |

| 6 | 92 | 1 | T |

| 7 | 92 | 1 | C |

| 8 | 92 | 1 | C |

| 9 | 93 | 2 | TC |

| 10 | 94 | 3 | GCC |

| 11 | 101 | 10 | ACCCTGGTCC |

| 12 | 108 | 17 | TCCCCGGCCCGCCGGCG |

| 13 | 126 | 35 | CTCCGCGACTCCCGGTTGTGGCCGCTCCGCGGCCG |

| 14 | 164 | 73 | ATCCGCTCGCCGCGTCTTCCGGCGCTCTCCGCCGGGGCGTCGCACCGTCTTCCGTGCGCCGGGCCTCCCGGCG |

The nucleotide sequences of the CxFV-Mex07 and NIID-21 genomes are 90.4% identical. The predicted amino acid sequences of the CxFV-Mex07 and NIID-21 polyprotein precursors are 96.8% identical and 98.5% similar. Greatest amino acid identity occurs in the membrane, NS1, and NS5 regions (97.9%, 97.8%, and 97.8%, respectively). Lowest amino acid identity occurs in the capsid, NS4B, and NS2B regions (89.2%, 94.3%, and 94.5%, respectively). Alignment of the genomic sequence of CxFV-Mex07 with all other flavivirus genomic sequences in the Genbank database showed that CxFV-Mex07 is most closely related to Kamiti River virus (KRV), an insect-specific flavivirus first isolated in Kenya in 1999, 25,26 and cell fusing agent virus (CFAV), an insect-specific flavivirus originally isolated from Ae. aegypti cell cultures and later discovered in natural mosquito populations in Puerto Rico. 27–29 The nucleotide sequence of CxFV-Mex07 is 56.1% identical to CFAV and 52.6% identical to KRV. The deduced amino acid sequence of the CxFV-Mex07 polyprotein precursor is 46.5% identical and 65.8% similar to CFAV and 39.8% identical and 61.6% similar to KRV. The nucleotide sequence of CxFV is also genetically similar to cell silent agent, a flavivirus-related DNA sequence integrated into the genomes of some Aedes spp. mosquitoes. 30

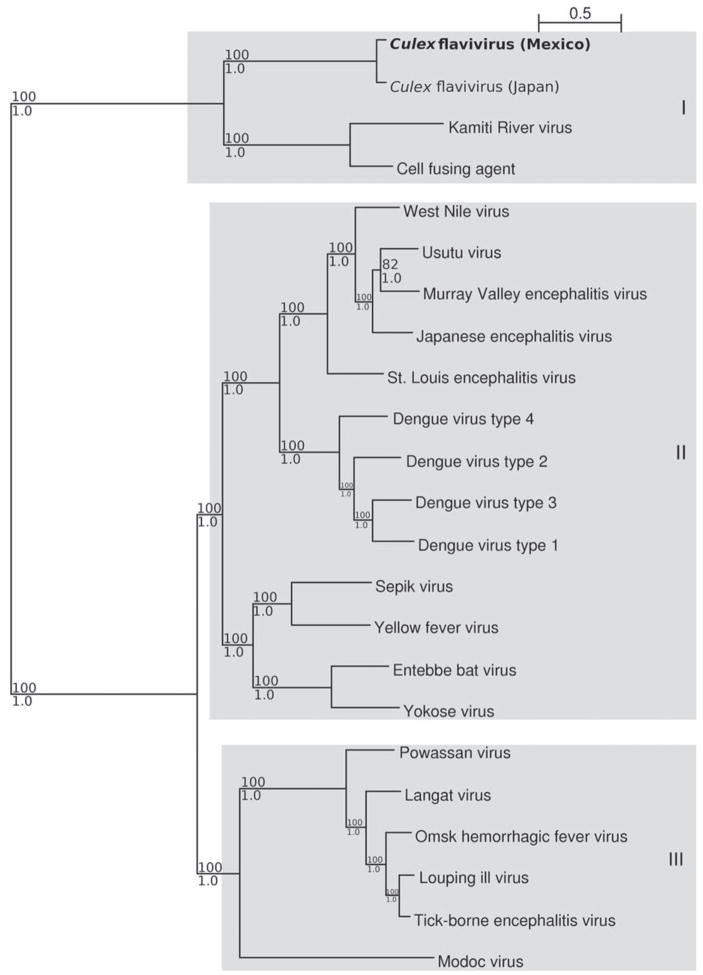

A phylogenetic tree was constructed with Bayesian methods using the complete genomic sequence of CxFV-Mex07 and the genomic sequences of 22 other flavivirus isolates (Figure 3). Phylogenetic trees were also generated using NJ, MP, and ML methods. In the Bayesian tree, CxFV-Mex07 shares a close phylogenetic relationship with NIID-21. CxFV-Mex07 is also phylogenetically similar to KRV and CFA, which is consistent with the identity/similarity estimates. These insect-specific viruses comprise a distinct clade (denoted as I), and the posterior support for this topologic arrangement is 100%. The other viruses separate into two additional clades. Clade II contains mosquito/vertebrate viruses, and clade III contains tick/vertebrate viruses. The viruses with no known vector are present in both clades II and III. This topologic arrangement is consistent to that observed in other several flavivirus phylogenetic studies.31 The ML tree was identical to the Bayesian tree, but the NJ and MP trees placed Modoc virus between the insect-specific flaviviruses and the other flaviviruses.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of the Mexican strain of Culex flavivirus. The displayed phylogeny was estimated by the program MRBAYES, version 3.1. 45 The inferred tree is unrooted, but we show it rooted on the same branch as the phylogeny of Figure 2. All phylogenetic analyses were based on the complete genomic sequence of Culex flavivirus and 22 other flaviviruses. Full genome alignments were made with multiple alignment using fast Fourier transform, using the linsi utility. 23 Phylogenetic analyses were as described in Figure 2, and the general time reversible gamma + proportion invariant model was supported by jModeltest. Bootstrap support and posterior label each branch as in Figure 2. The Culex flavivirus isolate from Mexico is denoted in bold. GenBank accession nos. for sequences used in the phylogenetic analysis are Cell fusing agent (M91671), Culex flavivirus (Japan; AB262759), Culex flavivirus (Mexico; EU879060), Dengue type 1 (U88536), Dengue type 2 (U87411), Dengue type 3 (AY099336), Dengue type 4 (AF326825), Entebbe bat (DQ837641), Japanese encephalitis (M18370), Kamiti River (AY149905), Langat (AF253419), Louping ill (Y07863), Modoc (AJ242984), Murray Valley encephalitis (AF161266), Omsk hemorrhagic fever (AY193805), Powassan (L06436), Sepik (DQ837642), St. Louis encephalitis (DQ525916), Tick-borne encephalitis (U27495), Usutu (AY453411), West Nile (DQ211652), Yellow fever (X03700), and Yokose (AB114858) viruses. The scale is measured in expected number of mutations per site.

DISCUSSION

In response to the introduction of WNV into Mexico, mosquito surveillance for arboviruses was conducted in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico. A total of 96,687 mosquitoes in 2,730 pools were processed for virus isolation in Vero cells. Three pools caused virus-like CPE. One isolate was identified as Cache Valley virus, an orthobunyavirus associated with disease and pregnancy loss in domestic ruminants.32 Another isolate was identified as Kairi virus, an orthobunyavirus that occasionally causes febrile illness in equines.33,34 The identity of the third infectious agent was not determined. The proportion of mosquitoes containing cytopathic virus was low. Assuming that the unidentified infectious agent is a virus, one virus was isolated for every 32,229 mosquitoes tested. In comparison, 164 isolations were made from 539,694 mosquitoes (1 virus per 3291 mosquitoes) collected in the Amazon Basin of Peru in 1996–2001. 35 Of these isolates, 139 isolates were from Culex (Melanoconion) spp. mosquitoes. The absence of Cx. (Mel.) spp. mosquitoes in our collections could have contributed to the lower frequency at which we isolated cytopathic viruses. The low number of isolations made in Vero cells was not because the mosquito specimens were of poor quality (i.e., inactivation of virus during international transportation) because we had no difficulties isolating CxFV from these mosquitoes.

One of our most significant findings was the detection of RNA to a novel flavivirus, tentatively named T’Ho virus, in Cx. quinquefasciatus from the Merida zoo. The virus has a close genetic and phylogenetic relationship, and therefore probably a close antigenic relationship, to WNV and various other flaviviruses including SLEV, ILHV, and ROCV. Flaviviruses are known for their serologic cross-reactivity; 36 thus, it is likely that antibodies to T’Ho virus can bind to and neutralize WNV. This finding raises the possibility that some vertebrate animals from Mexico previously considered to be seropositive for WNV by plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT) in serologic investigations have instead been infected with T’Ho virus. In this regard, we previously identified nine vertebrate animals in the Merida zoo that were considered to be seropositive for WNV because their PRNT90 titers to WNV were at least four-fold greater than to the other viruses tested (SLEV, ILHV and BSQV). 15 Of these animals, three were birds that had low WNV PRNT90 titers. The three birds all had WNV PRNT90 titers of 40, and none had antibodies to SLEV, ILHV, or BSQV at the initial serum dilution of 1:20. Thus, each bird met the CDC-established criteria for a WNV infection. Nonetheless, had T’Ho virus been included in the PRNT analysis and the T’Ho virus PRNT90 titers been ≥ 160, the outcome of the PRNT diagnosis would have changed. However, it is also important to note that several vertebrates in the zoo had high WNV PRNT90 titers, including a black vulture and a peacock that had WNV PRNT90 titers of 640 and 1,280, respectively. To reduce the likelihood of serologic misdiagnosis in WNV surveillance studies, it is important that T’Ho virus is isolated and included in future PRNTs. Experiments should also be conducted to characterize the antigenic properties and virulence of T’Ho virus, and to assess its potential to protect vertebrate animals from subsequent WNV infection. To better understand the antigenic relationship between T’Ho virus and WNV, it is important that the premembrane and envelope genes of T’Ho virus are sequenced because the nucleotide and amino acid alignments described here are based on partial NS5 sequences. Our research group is continuing its entomologic investigations in the Yucatan Peninsula and, in an attempt to isolate this virus, additional time and effort is now being devoted to the trapping of mosquitoes at the Merida zoo.

A high prevalence of CxFV was detected in Cx. quinquefasciatus. This finding is significant because it could explain why only a small number of cytopathic viruses were isolated in this study. Mosquitoes infected with CxFV could be refractory or less susceptible to subsequent infection with WNV or other viruses. The process by which a host, whether vertebrate or invertebrate, infected with one virus does not support productive replication of the same or similar virus is known as superinfection exclusion (or homologous interference) and has been reported for a diverse range of viruses. 37–40 For example, mosquito cell cultures infected with one DENV serotype are less susceptible than uninfected cultures to infection with a second serotype. 38 Most Ae. triseriatus infected with La Crosse virus (LACV) were refractory to superinfection with a second strain of LACV 72 hours after the initial infection. 39 There have also been occasional reports of where replication of a heterologous virus has been suppressed; for example, DENV-2 produced significantly lowers titers when cultured in densovirus-infected C6/36 cells compared with uninfected C6/36 cells. 37 To explore the possibility that CxFV is attributing to the lack of WNV disease in the Yucatan Peninsula by reducing the number of competent vectors available, future research is needed to determine whether superinfection exclusion of WNV occurs in Cx. quinquefasciatus infected with CxFV.

The vector range and prevalence of CxFV is not well defined. The virus was first isolated in a nationwide survey performed in Japan in 2003 and 2004. 22 Eight CxFV isolates were obtained, and these were from Cx. pipiens (n = 6), Cx. tritaeniorhynchus (n = 1), and Cx. quinquefasciatus (n = 1). An additional isolate was from a pool of Cx. quinquefasciatus collected in Indonesia. The MIR for CxFV was not reported in this study; thus, the prevalence of CxFV in Japan and the Yucatan Peninsula has not been compared. Recent data have shown that the geographic distribution of CxFV is not restricted to the Eastern Hemisphere; the virus has been isolated in Mexico (this study), Guatemala (Morales-Betoulle ME, unpublished data), and Colorado (Bolling BG, unpublished data). We have also isolated CxFV from Cx. pipiens in Iowa, and genomic sequencing experiments are in progress (Blitvich BJ, unpublished data).

Heterogeneous sequences were identified at the distal end of the 5′UTR of the Mexican strain of CxFV. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report the identification of heterogeneous sequences at the distal end of the 5′UTR of a positive-sense RNA virus. Some negative-sense RNA viruses (influenza virus and certain bunyaviruses) contain heterogeneous sequences at the distal ends of their 5′UTRs, and these sequences are acquired from cellular mRNAs by a unique cap scavenging mechanism. 41,42 It is unclear whether the heterogeneous sequences identified in this study represent an artifact of our experimental approach or bona fide sequence found in CxFV in nature.

Cx. quinquefasciatus, which is a major enzootic vector of WNV in the southeastern United States, 43,44 was the most common species in this study; it made up almost half of the total sample population. Furthermore, collections of Cx. quinquefasciatus were made each month. Many other mosquito spp. that are major enzootic vectors of WNV in the United States were not sampled (Cx. pipiens, Cx. restuans, Cx. salinarius) or were infrequently collected (Cx. nigripalpus, Cx. tarsalis). Thus, the ability of Cx. quinquefasciatus populations in the Yucatan Peninsula to become infected with and to transmit WNV could be a major determinant of the epidemic and epizootic potential of WNV in this region.

In summary, we have provided sequence data that indicates a novel flavivirus is present in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico, and have demonstrated a high prevalence of an insect-specific flavivirus in Cx. quinquefasciatus in this region. Characterization of these viruses and continued arbovirus surveillance in Mexico is warranted because the data obtained from these studies will help us understand why a major outbreak of WNV disease has not been observed in Mexico.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the field workers from UADY (Carlos Baak, Mildred López, Carlos Estrella, Alex Ic, Roger Arana, Wilberth Chi, Hugo Valenzuela, Iván Villanueva, Jesús Miss, Rosa Cetina, Lourdes Talavera, and Roger López) for their assistance.

Financial support: This study was supported by grant 5R21AI067281-02 from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Gubler DJ. The global emergence/resurgence of arboviral diseases as public health problems. Arch Med Res. 2002;33:330–342. doi: 10.1016/s0188-4409(02)00378-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gubler DJ. Dengue/dengue haemorrhagic fever: history and current status. Novartis Found Symp. 2006;277:3–16. doi: 10.1002/0470058005.ch2. discussion 16–22, 71–73, 251–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kyle JL, Harris E. Global spread and persistence of dengue. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2008;62:71–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.163005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blitvich BJ. Transmission dynamics and changing epidemiology of West Nile virus. Anim Health Res Rev. 2008;9:71–86. doi: 10.1017/S1466252307001430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Komar N, Clark GG. West Nile virus activity in Latin America and the Caribbean. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2006;19:112–117. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892006000200006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burke D, Monath T. Flaviviruses. In: Knipe D, Howley P, editors. Fields Virology. 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2001. pp. 1043–1126. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blitvich BJ, Fernandez-Salas I, Contreras-Cordero JF, Marlenee NL, Gonzalez-Rojas JI, Komar N, Gubler DJ, Calisher CH, Beaty BJ. Serologic evidence of West Nile virus infection in horses, Coahuila State, Mexico. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:853–856. doi: 10.3201/eid0907.030166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elizondo-Quiroga D, Davis CT, Fernandez-Salas I, Escobar-Lopez R, Velasco Olmos D, Soto Gastalum LC, Aviles Acosta M, Elizondo-Quiroga A, Gonzalez-Rojas JI, Contreras Cordero JF, Guzman H, Travassos da Rosa A, Blitvich BJ, Barrett AD, Beaty BJ, Tesh RB. West Nile virus isolation in human and mosquitoes, Mexico. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1449–1452. doi: 10.3201/eid1109.050121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lorono-Pino MA, Blitvich BJ, Farfan-Ale JA, Puerto FI, Blanco JM, Marlenee NL, Rosado-Paredes EP, Garcia-Rejon JE, Gubler DJ, Calisher CH, Beaty BJ. Serologic evidence of West Nile virus infection in horses, Yucatan State, Mexico. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:857–859. doi: 10.3201/eid0907.030167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cruz L, Cardenas VM, Abarca M, Rodriguez T, Reyna RF, Serpas MV, Fontaine RE, Beasley DW, da Rosa AP, Weaver SC, Tesh RB, Powers AM, Suarez-Rangel G. Short report: serological evidence of West Nile virus activity in El Salvador. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:612–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morales-Betoulle ME, Morales H, Blitvich BJ, Powers AM, Davis EA, Klein R, Cordon-Rosales C. West Nile virus in horses, Guatemala. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1038–1039. doi: 10.3201/eid1206.051615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adrian Diaz L, Komar N, Visintin A, Dantur Juri MJ, Stein M, Lobo Allende R, Spinsanti L, Konigheim B, Aguilar J, Laurito M, Almiron W, Contigiani M. West Nile virus in birds, Argentina. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:689–691. doi: 10.3201/eid1404.071257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mattar S, Edwards E, Laguado J, Gonzalez M, Alvarez J, Komar N. West Nile virus antibodies in Colombian horses. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1497–1498. doi: 10.3201/eid1109.050426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farfan-Ale JA, Blitvich BJ, Lorono-Pino MA, Marlenee NL, Rosado-Paredes EP, Garcia-Rejon JE, Flores-Flores LF, Chulim-Perera L, Lopez-Uribe M, Perez-Mendoza G, Sanchez-Herrera I, Santamaria W, Moo-Huchim J, Gubler DJ, Cropp BC, Calisher CH, Beaty BJ. Longitudinal studies of West Nile virus infection in avians, Yucatan State, Mexico. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2004;4:3–14. doi: 10.1089/153036604773082942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farfan-Ale JA, Blitvich BJ, Marlenee NL, Lorono-Pino MA, Puerto-Manzano F, Garcia-Rejon JE, Rosado-Paredes EP, Flores-Flores LF, Ortega-Salazar A, Chavez-Medina J, Cremieux-Grimaldi JC, Correa-Morales F, Hernandez-Gaona G, Mendez-Galvan JF, Beaty BJ. Antibodies to West Nile virus in asymptomatic mammals, birds, and reptiles in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:908–914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clark GG, Seda H, Gubler DJ. Use of the “CDC backpack aspirator” for surveillance of Aedes aegypti in San Juan, Puerto Rico. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1994;10:119–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kramer LD, Presser SB, Houk EJ, Hardy JL. Effect of the anesthetizing agent triethylamine on western equine encephalomyelitis and St. Louis encephalitis viral titers in mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) J Med Entomol. 1990;27:1008–1010. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/27.6.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lanciotti RS, Kerst AJ, Nasci RS, Godsey MS, Mitchell CJ, Savage HM, Komar N, Panella NA, Allen BC, Volpe KE, Davis BS, Roehrig JT. Rapid detection of West Nile virus from human clinical specimens, field-collected mosquitoes, and avian samples by a TaqMan reverse transcriptase-PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:4066–4071. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.11.4066-4071.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuno G, Chang GJ, Tsuchiya KR, Karabatsos N, Cropp CB. Phylogeny of the genus Flavivirus. J Virol. 1998;72:73–83. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.73-83.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eshoo MW, Whitehouse CA, Zoll ST, Massire C, Pennella TT, Blyn LB, Sampath R, Hall TA, Ecker JA, Desai A, Wasieloski LP, Li F, Turell MJ, Schink A, Rudnick K, Otero G, Weaver SC, Ludwig GV, Hofstadler SA, Ecker DJ. Direct broad-range detection of alphaviruses in mosquito extracts. Virology. 2007;368:286–295. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuno G, Mitchell CJ, Chang GJ, Smith GC. Detecting bunyaviruses of the Bunyamwera and California serogroups by a PCR technique. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1184–1188. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.5.1184-1188.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoshino K, Isawa H, Tsuda Y, Yano K, Sasaki T, Yuda M, Takasaki T, Kobayashi M, Sawabe K. Genetic characterization of a new insect flavivirus isolated from Culex pipiens mosquito in Japan. Virology. 2007;359:405–414. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minin VN, Dorman KS, Fang F, Suchard MA. Dual multiple change-point model leads to more accurate recombination detection. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3034–3042. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Billoir F, de Chesse R, Tolou H, de Micco P, Gould EA, de Lamballerie X. Phylogeny of the genus flavivirus using complete coding sequences of arthropod-borne viruses and viruses with no known vector. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:781–790. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-3-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crabtree MB, Sang RC, Stollar V, Dunster LM, Miller BR. Genetic and phenotypic characterization of the newly described insect flavivirus, Kamiti River virus. Arch Virol. 2003;148:1095–1118. doi: 10.1007/s00705-003-0019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sang RC, Gichogo A, Gachoya J, Dunster MD, Ofula V, Hunt AR, Crabtree MB, Miller BR, Dunster LM. Isolation of a new flavivirus related to cell fusing agent virus (CFAV) from field-collected flood-water Aedes mosquitoes sampled from a dambo in central Kenya. Arch Virol. 2003;148:1085–1093. doi: 10.1007/s00705-003-0018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cook S, Bennett SN, Holmes EC, de Chesse R, Moureau G, de Lamballerie X. Isolation of a new strain of the flavivirus cell fusing agent virus in a natural mosquito population from Puerto Rico. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:735–748. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81475-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stollar V, Thomas VL. An agent in the Aedes aegypti cell line (Peleg) which causes fusion of Aedes albopictus cells. Virology. 1975;64:367–377. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(75)90113-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cammisa-Parks H, Cisar LA, Kane A, Stollar V. The complete nucleotide sequence of cell fusing agent (CFA): homology between the nonstructural proteins encoded by CFA and the nonstructural proteins encoded by arthropod-borne flaviviruses. Virology. 1992;189:511–524. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90575-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crochu S, Cook S, Attoui H, Charrel RN, De Chesse R, Belhouchet M, Lemasson JJ, de Micco P, de Lamballerie X. Sequences of flavivirus-related RNA viruses persist in DNA form integrated in the genome of Aedes spp. mosquitoes. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:1971–1980. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.79850-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cook S, Holmes EC. A multigene analysis of the phylogenetic relationships among the flaviviruses (Family: Flaviviridae) and the evolution of vector transmission. Arch Virol. 2006;151:309–325. doi: 10.1007/s00705-005-0626-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de la Concha-Bermejillo A. Cache Valley virus is a cause of fetal malformation and pregnancy loss in sheep. Small Rumin Res. 2003;49:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calisher CH, Oro JG, Lord RD, Sabattini MS, Karabatsos N. Kairi virus identified from a febrile horse in Argentina. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;39:519–521. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1988.39.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmaljohn CS, Nichol ST. Bunyaviridae. In: Knipe DM, editor. Fields Virology. 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007. pp. 1741–1789. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Turell MJ, O’Guinn ML, Jones JW, Sardelis MR, Dohm DJ, Watts DM, Fernandez R, Travassos da Rosa A, Guzman H, Tesh R, Rossi CA, Ludwig V, Mangiafico JA, Kondig J, Wasieloski LP, Jr, Pecor J, Zyzak M, Schoeler G, Mores CN, Calampa C, Lee JS, Klein TA. Isolation of viruses from mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) collected in the Amazon Basin region of Peru. J Med Entomol. 2005;42:891–898. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2005)042[0891:IOVFMD]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Calisher CH, Karabatsos N, Dalrymple JM, Shope RE, Porterfield JS, Westaway EG, Brandt WE. Antigenic relationships between flaviviruses as determined by cross-neutralization tests with polyclonal antisera. J Gen Virol. 1989;70:37–43. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-1-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burivong P, Pattanakitsakul SN, Thongrungkiat S, Malasit P, Flegel TW. Markedly reduced severity of Dengue virus infection in mosquito cell cultures persistently infected with Aedes albopictus densovirus (AalDNV) Virology. 2004;329:261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pepin KM, Lambeth K, Hanley KA. Asymmetric competitive suppression between strains of dengue virus. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sundin DR, Beaty BJ. Interference to oral superinfection of Aedes triseriatus infected with La Crosse virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;38:428–432. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1988.38.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tscherne DM, Evans MJ, von Hahn T, Jones CT, Stamataki Z, McKeating JA, Lindenbach BD, Rice CM. Superinfection exclusion in cells infected with hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 2007;81:3693–3703. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01748-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krug RM. Priming of influenza viral RNA transcription by capped heterologous RNAs. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1981;93:125–149. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-68123-3_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patterson JL, Holloway B, Kolakofsky D. La Crosse virions contain a primer-stimulated RNA polymerase and a methylated cap-dependent endonuclease. J Virol. 1984;52:215–222. doi: 10.1128/jvi.52.1.215-222.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sardelis MR, Turell MJ, Dohm DJ, O’Guinn ML. Vector competence of selected North American Culex and Coquillettidia mosquitoes for West Nile virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7:1018–1022. doi: 10.3201/eid0706.010617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Turell MJ, Sardelis MR, Dohm DJ, O’Guinn ML. Potential North American vectors of West Nile virus. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;951:317–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb02707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Posada D. jModelTest: phylogenetic model averaging. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25:1253–1256. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol. 2003;52:696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F, Nielsen R, Bollback JP. Bayesian inference of phylogeny and its impact on evolutionary biology. Science. 2001;294:2310–2314. doi: 10.1126/science.1065889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Altschul SF, Wootton JC, Gertz EM, Agarwala R, Morgulis A, Schaffer AA, Yu YK. Protein database searches using compositionally adjusted substitution matrices. FEBS J. 2005;272:5101–5109. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04945.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]